Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the novel coronavirus causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has affected human lives across the globe. On 11 December 2020, the US FDA granted an emergency use authorization for the first COVID-19 vaccine, and vaccines are now widely available. Undoubtedly, the emergence of these vaccines has led to substantial relief, helping alleviate the fear and anxiety around the COVID-19 illness for both the general public and clinicians. However, recent cases of vaccine complications, including myopericarditis, have been reported after administration of COVID-19 vaccines. This article discusses the cases, possible pathogenesis of myopericarditis, and treatment of the condition. Most cases were mild and should not yet change vaccine policies, although prospective studies are needed to better assess the risk–benefit ratios in different groups.

Key Points

| Cases of myopericarditis after receiving coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines have been reported, although most cases have been mild. |

| Similar to myocardial and pericardial involvement in the setting of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, COVID-19 vaccine-related myopericarditis can be associated with inappropriate inflammatory response, and anti-inflammatory drugs are noted as useful for treatment. |

| Prospective studies are necessary to determine whether the vaccine-related myopericarditis is casual or causal. |

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the novel coronavirus causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has affected human lives across the globe, with devastating consequences [1, 2]. A total of 182,319,261 confirmed cases and 3,954,324 deaths due to COVID-19 had been reported worldwide as of 28 June 2021, despite the implementation of control measures such as isolation of affected individuals, social distancing, frequent hand washing, and wearing of face masks [3, 4]. On the other hand, the development of effective vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 within 1 year of identifying its genomic sequence has been one of the most crucial scientific breakthroughs of the twenty-first century [5, 6]. The US FDA granted emergency use authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines in December 2020 and to the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine in February 2021 [7–9]. At the time of writing, 54.7% of the total population of the USA had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, and 47.1% of the population was fully vaccinated [10]. Safety data from the phase II/III trial of BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine) highlighted that injection site pain, fatigue, and headache accounted for a significant proportion of adverse reactions reported [11]. Reviews of surveillance data yielded similar observations, with local pain, fatigue, headache, myalgia, chills, and arthralgia being typical reactions [12]. Rare cases of anaphylaxis have also been identified following the administration of messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines [13, 14]. Lately, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the FDA have recognized 742 cases of myocarditis or pericarditis that developed after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination, especially in male adolescents and young adults [15]. Isolated cases of death following vaccine administration have been reported very recently and are currently under review [16]. Additionally, some potential severe complications of some of the COVID-19 vaccines have also been emphasized [17]. Although evidence of myopericarditis resulting from vaccination (e.g., smallpox) exists in the literature, only a few case reports of myocarditis occurring after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination have been published, with the data regarding causality and susceptibility remaining elusive [18]. Herein, we review the pathophysiology, diagnosis, characteristics, and management of myopericarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination.

COVID-19 Vaccines

The receptor-binding domain of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, which enables it to bind to the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 receptor on the host cell, was considered a potential target for vaccines [19, 20]. As of 29 June 2021, 105 vaccine candidates were undergoing clinical development and 184 vaccine candidates were in the preclinical phase of development globally [21]. They can be classified according to type of vaccine as follows: [22, 23]

genetic (Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech)

viral vector type (Janssen)

inactivated (Bharat Biotech)

attenuated (Codagenix—under clinical trial)

protein vaccine (Sanofi/GSK—under clinical trial)

The mRNA vaccine platform provides flexibility with the ability to translate any desired protein. Its minimal interaction with the genome enhances safety [24]. Lipid nanoparticles overcome the challenges of intracellular delivery with reduced extracellular hydrolysis of mRNA by ribonucleases [25]. The Pfizer/BioNTech (BNT162b2) and Moderna (mRNA-1273) vaccines are both lipid-nanoparticle-coated mRNA vaccines encoding for the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 [10, 26]. Immunization with mRNA vaccines has been found to induce both humoral and cellular immune responses in recipients [27]. Table 1 summarizes the COVID-19 vaccines that were available in the USA at the time of writing [28, 29].

Table 1.

| Vaccine manufacturer | Recommended age | Schedule | General efficacy | Efficacy against the variants | Side effects | Contraindicationsa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local | Systemic | ||||||

| Pfizer-BioNTech | ≥ 12 years | Two shots, 21 days apart | 95% efficacy in preventing COVID-19 in those without prior infection. 100% effective at preventing severe disease | More than 95% effective against severe disease or death from the alpha variant and the beta variant. For the delta variant, 88% effective against symptomatic disease and 96% effective against hospitalization (studies not yet peer reviewed) | Pain, swelling, redness | Tiredness, headache, muscle pain, chills, fever, nausea | Severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) or an immediate allergic reaction |

| Moderna | ≥ 18 years | Two shots, 28 days apart | 94.1% effective at preventing symptomatic infection | May provide protection against the alpha and beta variants; awaiting confirmation from studies | Pain, redness, swelling | Tiredness, headache, muscle pain, chills, fever, nausea | Severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) or an immediate allergic reaction |

| Janssen/Johnson & Johnson | ≥ 18 years | Single shot | 72% overall efficacy and 86% efficacy against severe disease | Has been shown to offer protection against the alpha variant. 64% overall efficacy and 82% efficacy against severe disease in South Africa, where the beta variant was first detected. Also effective against the delta variant | Pain, redness, swelling | Tiredness, headache, muscle pain, chills, fever, nausea | Severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) or an immediate allergic reaction |

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, mRNA messenger RNA

aIndividual with severe or immediate allergic reaction (within 4 h) that needs to be treated with epinephrine or EpiPen or with medical care after getting the first dose of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine should not get a second dose of either of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines

Side Effects of COVID-19 Vaccines

COVID-19 vaccines provided a ray of optimism during this global crisis. As highlighted, SARS-CoV-2 has caused the death of significant populations throughout the world. Vaccination has been shown to be effective in preventing a severe or lethal form of COVID-19. The FDA granted the emergency use of the mRNA-based Pfizer and Moderna vaccines to combat this challenging pandemic in December 2020. These vaccines were also associated with various local and systemic reactogenicity. Local side effects such as redness, rashes, tenderness, itch, warmth, and swollen axillary lymph nodes were observed during the clinical trials [30]. In general, local reactions were mild-to-moderate in severity and resolved within 1–2 days [11]. These vaccines were also involved in systemic side effects, including headache, fatigue, fever, diarrhea, myalgia, chills, anaphylaxis, and nausea [11].

Younger recipients were more susceptible to local and systemic adverse events, with systemic reactions being more common after the second dose. However, severe adverse reactions were noted to be infrequent in the clinical trials, with similar incidences in vaccine and placebo groups [11, 26]. The CDC and the FDA have been monitoring the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines post-rollout through different vaccine safety monitoring systems, including the Vaccine Adverse Effect Reporting System, Vaccine Safety Datalink, V-safe, and the National Healthcare Safety Network [31]. Such vigorous monitoring eventually identified rare cases of post-vaccination anaphylaxis, thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome, and cardiac involvement [15, 18]. The most frequent systemic reactogenicities were headache and fatigue [11]. The frequency of adverse effects is lower with the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine than with the Moderna vaccine; however, the Moderna vaccine is easier to transport and store because it is less temperature sensitive [12]. In addition, serious complications such myocarditis have been associated with administration of COVID-19 vaccines.

Myopericarditis Following COVID-19 Messenger RNA Vaccination

In June 2021, isolated case reports highlighting possible causal associations between both the BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and the mRNA-1273 (Moderna) mRNA-based vaccines and myocarditis and/or pericarditis began to surface [32–36]. In the short period since the first published report, more extensive case series have been reported with similar concerns about myocarditis and/or pericarditis following vaccine administration.

In a case series from Israel, Abu Mouch et al. [37] described six patients who developed myocarditis after the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. At the time of reporting, 4 million people in Israel had received two doses [37]. Larson et al. [38] also reported the cases of eight male adults, ranging in age from 21 to 56 years (median 22), who developed symptoms suggestive of myocarditis, later confirmed on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) within 2–4 days of the second dose of the mRNA vaccine. Three of these cases received the mRNA-1273 vaccine, and the remaining five patients received the BNT162b2 vaccine [38]. Kim et al. [39] reported four cases of adult males who developed myocarditis within 5 days of administration of the second vaccine dose (50% BNT162b2 vaccine, 50% mRNA-1273 vaccine). Montgomery et al. [40] also reported 23 cases of adult males (median age 25 years) within the US Military Health System who developed symptoms of myocarditis within 4 days of receiving the second dose of mRNA vaccine (30% BNT162b2 vaccine, 70% mRNA-1273 vaccine). Rosner et al. [41] also reported seven cases of adult males developing myocarditis following the second dose of a vaccine, with most patients receiving the BNT162b2 vaccine. Similar cases have also been reported in the pediatric age group, with each case noted to have received the only approved vaccine in this age group: the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine [42, 43]. Although most of the myopericarditis cases were reported after administration of mRNA vaccines, a few cases were reported after administration of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson). Interestingly, pericarditis without myocarditis was reported after this vaccine [44]. In a case series, seven male adolescents ranging in age from 14 to 18 years developed myocarditis 2–4 days after the second dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine [45]. Recently, a retrospective review by Schauer et al. [46] described the cases of 13 patients with myopericarditis after the second dose of the Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Interestingly, one case of a 17-year-old male with a recurrence of acute myocarditis has been reported [47]. The patient presented with myocarditis 4 months after an initial episode of acute myocarditis. He tested negative for COVID-19 during the first episode. The second episode was noted 48 h after receiving the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine [47]. Table 2 presents the clinical and diagnostic characteristics of the patients with myopericarditis. By 28 June 2021, the CDC had received 518 confirmed cases of myocarditis or pericarditis after vaccine administration [15]. All the reported cases presented to the hospital with complaints of retrosternal chest pain that often worsened with inspiration and was relieved by leaning forward. In addition to the classic pericardial pain, some patients also reported dyspnea. Initial vitals at presentation were notably stable for all patients. Admission workup included clinically significant elevations in troponin levels (elevated to more than three times the upper normal limit) and C-reactive protein levels, highly suggestive of myocardial inflammation. The electrocardiogram was significant for ST-segment elevation (diffusely present in most patients), with normal sinus rhythm. Active SARS-CoV-2 infection was ruled out by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasopharyngeal swab obtained at admission in each of the cases. A complete respiratory panel comprising Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus, influenza, enterovirus, adenovirus, herpesvirus 6, and hepatitis B and C were negative in all cases. Other etiologies, including autoimmune, were also ruled out. Transthoracic echocardiogram was notable for a mildly reduced to normal left ventricular ejection fraction and global hypokinesis, if present at all [33]. The final diagnosis was made based on findings of the cardiac MRI, with the pattern of late gadolinium enhancement consistent with the diagnosis of myopericarditis in all the reported cases according to the 2018 Lake Louise criteria [48]. The CDC recommends use of the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for diagnosis and management of myocarditis in children for this young adult population [49, 50].

Table 2.

| Pt | Study | Age, sex, race, country | Vaccine; number of doses | Day of presentation: symptoms | Peak/BL TRO; highest CRP | ECG, echoa, WMAb, MRI | Clinical course | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Larson et al. [38] | 22; M; W; USA | mRNA-1273; two | 3: fever, chill, myalgia, CP |

TRO: 285 CRP: 4.8 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: 50%. WMA: gen. MRI: patchy subpericardial LGE | HD stable | NSAIDs, CCS |

| 2 | 31; M; W; USA | mRNA-1273; two | 3: fever, chill, CP, SOB |

TRO: 46 CRP: 14 |

ECG: normal. Echo: 34%. WMA: gen. MRI: patchy subpericardial and midmyocardial LGE | HD stable, TTE normal on d 11 | None | |

| 3 | 40; M; W; USA | BNT162b2; one | 2: CP |

TRO: 520 CRP: 9.5 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: 47%. WMA: gen. MRI: LGE and edema, pericardial effusion | HD stable | Colchicine, CCS | |

| 4 | 56; M; W; Italy | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP |

TRO: 37 CRP: 5.81 |

ECG: diffuse peaked T waves. Echo: 60%. WMA: inferolateral. MRI: LGE and edema | HD stable | None | |

| 5 | 26; M; W; Italy | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP |

TRO: 100 CRP: 1 |

ECG: inferolateral STE. Echo: 60%. WMA: inferior. MRI: LGE and edema, pericardial effusion | ICU 2 d, no inotropes, SD | Colchicine | |

| 6 | 35; M; W; Italy | BNT162b2; two | 2: CP |

TRO: 29 CRP: 9 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: 50%. WMA: inferolateral. MRI: LGE and edema | ICU 4 d, no inotropes, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 7 | 21; M; W; Italy | BNT162b2; two | 4: CP |

TRO: 1164 CRP: 4.6 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: 54%. WMA: inferior posterolateral. MRI: LGE and edema, pericardial effusion | ICU 2 d, no inotropes, NSVT, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 8 | 22; M; A; USA | mRNA-1273; two | 2: CP |

TRO: 1433 CRP: 4 |

ECG: inferior and anterolateral STE. Echo: 53%. WMA: inferior. MRI: LGE and edema | NSVT | None | |

| 9 | Marshall et al. [45] | 16; M; W | BNT162b2; two | 2: CP, nausea, vomiting |

TRO: 15.5 CRP: 1.23 |

ECG: diffuse STE, AV dissociation with junctional escape. Echo: normal. WMA: none. MRI: subpericardial LGE in lateral LV apex | NR | NSAIDs, CCS, IVIg |

| 10 | 19; M; W | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP |

TRO: 27.7 CRP: 6.7 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: normal. WMA: none. MRI: midmyocardial LGE in basal inferolateral wall | NR | Colchicine | |

| 11 | 17; M; W | BNT162b2; two | 2: CP |

TRO: 271.1 CRP: 2.53 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: normal, basal lateral, basal posterior. WMA: NR. MRI: subpericardial LGE in basal anterolateral and inferolateral wall | NR | NSAIDs | |

| 12 | 18; M; W | BNT162b2; two | 2: CP |

TRO: 109 CRP: 12.7 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: normal. WMA: none. MRI: fibrosis and edema | NR | NSAIDs, CCS, IVIg | |

| 13 | 17; M; W | BNT162b2; two | 4: CP, nausea, vomiting, SOB |

TRO: 333 CRP: 18.1 |

ECG: T-wave abnormality. Echo: normal. WMA: none. MRI: epicardial LGE in anterior and lateral LV | NR | NSAIDs, CCS, IVIg | |

| 14 | 16; M; W | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP, SOB |

TRO: 82 CRP: 1.8 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: normal. WMA: none. MRI: LGE and edema | NR | CCS, IVIg | |

| 15 | 14; M; W | BNT162b2; two | 2: CP, SOB |

TRO: 491.1 CRP: 12.7 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: 47%. WMA: RV, LV. MRI: subpericardial LGE in mid and apical free wall | NR | NSAIDs | |

| 16 | Abu Mouch et al. [37] | 24; M; Israel | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP/discomfort |

TRO: 45 CRP: 12 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: normal. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial and midmyocardial LGE in basal septum and inferior wall | NR | NR |

| 17 | 20; M; Israel | BNT162b2; two | 1 |

TRO: 81.69 CRP: 20 |

ECG: STE V2–V6. Echo: 50%. WMA: NR. MRI: mild myocardial edema with LGE in the subepicardial, basal, middle anterolateral, and inferolateral walls | NR | NR | |

| 18 | 29; M; Israel | BNT162b2; two | 2 |

TRO: 67.38 CRP: 17.2 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: normal. WMA: NR. MRI: mild diffuse myocardial edema and LGE of the basal, inferolateral, anterolateral, anteroseptal walls | NR | NR | |

| 19 | 45; M; Israel | BNT162b2; one | 16 |

TRO: 30.15 CRP: 11.2 |

ECG: STE: I, aVL, V3-5 Inverted T, STD: III, aVF. Echo: 50%. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial edema of the middle anterolateral, inferolateral, and apical anterior walls with LGE of the same walls |

NR | NR | |

| 20 | 16; M; Israel | BNT162b2; two | 1 | CRP: normal | ECG: lateral STE. Echo: normal. WMA: NR. MRI: midmyocardial and subepicardial edema of the basal inferolateral and middle anterolateral segment. LGE present in the same area | NR | NR | |

| 21 | 17; M; Israel | BNT162b2; two | 3 |

TRO: 87 CRP: 11 |

ECG: STE I II aVL, V2–6, SI QIII TIII. Echo: normal. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial edema of the basal inferolateral, middle inferolateral, and inferoseptal and apical lateral, anterior, and inferior walls. LGE present in the same area, and mid-myocardial enhancement of middle inferolateral and anterolateral and apical anterior and lateral walls | NR | NR | |

| 22 | Albert et al. [32] | 24; M; USA | mRNA-1273; two | 4: fever, chills, myalgia, cough on d 1, CP |

TRO: 473.5 CRP: 2.64 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: normal. WMA: NR. MRI: patchy midmyocardial and epicardial LGE | NR | NSAIDs, CCS |

| 23 | D’Angelo et al. [33] | 30; M; Italy | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP, SOB, diaphoresis, nausea |

TRO: 367.36 CRP: 7.92 |

ECG: STE in V2–V4. Echo: NR. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial LGE | NR | NSAIDs, CCS |

| 24 | Rosner et al. [41] | 28; M; W | J&J; one | 5: CP |

TRO: 427 CRP: 1.3 |

ECG: STE in II, V5, V6. Echo: 51%. WMA: gen. MRI: subepicardial LGE in mid to apical wall | NR | NSAIDs |

| 25 | 39; M; W | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP, SOB |

TRO: 275.25 CRP: 5.1 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: 40%. WMA: gen. MRI: subepicardial LGE in anterior and lateral wall | NR | None | |

| 26 | 39; M; W | mRNA-1273; two | 4: CP |

TRO: 325 CRP: 11.7 |

ECG: no changes. Echo: 61%. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial and midmyocardial LGE in anterior wall | NR | CCS | |

| 27 | 24; M; W | BNT162b2; one | 7: CP |

TRO: 9.25 CRP: 0.1 |

ECG: no changes. Echo: 53%. WMA: NR. MRI: midmyocardial LGE in septal and inferior wall | NR | NSAIDs, colchicine | |

| 28 | 19; M; H | BNT162b2; two | 2: CP |

TRO: 1120 CRP: 3.1 |

ECG: no changes. Echo: 55%. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial and midmyocardial LGE in inferolateral wall | NR | NSAIDs, colchicine | |

| 29 | 20; M; W | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP |

TRO: 209 CRP: 8.2 |

ECG: STE in V2–V5. Echo: 55%. WMA: distal anteroseptal and apical. MRI: subepicardial LGE in lateral, inferolateral, and anterolateral wall, including apex | NR | NSAIDs | |

| 30 | 23; M; W | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP | CRP 7.3 | ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: 58%. WMA: NR. MRI: basal anteroseptal LGE | NR | Colchicine | |

| 31 | Habib et al. [36] | 37; M; Asian; Qatar | BNT162b2; two | 3: fever, cough, CP | TRO: 75.86 | ECG: STE anterior leads. Echo: 57%. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial LGE in basal lateral wall | NR | |

| 32 | Mclean and Johnson [42] | 16; M | BNT162b2; two | 3: fever, cough, CP | CRP 7.6 | ECG: STE V2–V6, aVL. Echo: 61%. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial LGE in lateral wall | NR | IVIg |

| 33 | Mansour et al. [35] | 25; M | mRNA-1273; two | 1: fever, cough, CP |

TRO: 466.66 CRP: 510 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: 55%. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial LGE in the anterolateral wall in the mid-ventricle to apex | NR | NR |

| 34 | 21; F | mRNA-1273; two | 2: fever, cough, CP |

TRO: 7.6 CRP: 14.6 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: 50%. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial LGE in the inferolateral wall | NR | NR | |

| 35 | Muthukumar et al. [54] | 52; M | mRNA-1273; two | 3: fever, cough, CP, headache | ECG: normal. Echo: NR. WMA: NR. MRI: LGE in the inferoseptal, inferolateral, anterolateral, and apical walls | NR | NR | |

| 36 | Minocha et al. [47] | 17; M | BNT162b2; two | 2 |

TRO: 126.5 CRP: 1284 |

ECG: diffuse STE. Echo: 53%. WMA: NR. MRI: subepicardial LGE | NR | NR |

| 37 | Kim et al. [39] | 36; M | mRNA-1273; two | 3: fever, CP, SOB |

TRO: 230 CRP: 6.32 |

ECG: diffuse STE, PR depression. Echo: 53%. WMA: NR. MRI: epicardial LGE apical lateral wall | NR | NSAIDs, colchicine |

| 38 | 23; M | BNT162b2; two | 5: fever, CP, SOB |

TRO: 7452 CRP: 2.2 |

ECG: lateral STE. Echo: 58%. WMA: NR. MRI: epicardial LGE in multiple walls | NR | Colchicine, CCS | |

| 39 | 70; F | mRNA-1273; two | 1: CP, SOB | TRO: 2.34 | ECG: anterolateral STE. Echo: 40%. WMA: NR. MRI: patchy diffuse LGE in multiple walls | NR | NR | |

| 40 | 24; M | BNT162b2; two | 2: fever, CP, palpitation |

TRO: 698 CRP: 6.08 |

ECG: diffuse STE, PR depression. Echo: 59%. WMA: NR. MRI: epicardial patchy LGE in lateral wall | NR | Colchicine, NSAIDs | |

| 41 | Schauer et al. [46] | 16; M; W; USA | BNT162b2; two | 2: CP, fever, chills, myalgia, headache, SOB |

TRO: 8 CRP: 4.3 |

ECG: normal. Echo: 66%. WMA: none. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 1 d, SD | NSAIDs |

| 42 | 16; M; A; USA | BNT162b2; two | 2: CP, fever, myalgia |

TRO: 11.1 CRP: 3.5 |

ECG: STE. Echo: 59%. WMA: none. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 1 d, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 43 | 16; M; W; USA | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP, myalgia, headache |

TRO: 10.9 CRP: 3.6 |

ECG: STE. Echo: 69%. WMA: none. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 3 d, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 44 | 17; M; American Indian/Alaska Native; USA | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP, fever, malaise |

TRO: 9.18 CRP: NR |

ECG: STE. Echo: 58%. WMA: none. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 1 d, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 45 | 15; M; W; USA | BNT162b2; two | 2: CP, myalgia, SOB |

TRO: 4.95 CRP: 5.5 |

ECG: normal. Echo: 58%. WMA: None. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 2 d, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 46 | 15; F; W; USA | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP, vomiting |

TRO: 0.65 CRP: 1.4 |

ECG: nonspecific T-wave changes. Echo: 58%. WMA: none. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 1 d, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 47 | 15; M; W; USA | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP, fever, SOB |

TRO: 9.12 CRP: 3 |

ECG: T-wave inversion. Echo: 61%. WMA: none. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 3 d, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 48 | 15; M; W; USA | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP, chills |

TRO: 13.2 CRP: 6.2 |

ECG: STE. Echo: 45%. WMA: LV regional. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 3 d, SD | NSAIDs, IVIG, CCS | |

| 49 | 12; M; W; USA | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP |

TRO: 13 CRP: NR |

ECG: normal. Echo: 64%. WMA: none. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 2 d, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 50 | 14; M; W; USA | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP, fever, headache |

TRO: 18.5 CRP: NR |

ECG: STE. Echo: 62%. WMA: none. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 3 d, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 51 | 14; M; A; USA | BNT162b2; two | 4: CP, malaise, SOB |

TRO: 6.08 CRP: 3.7 |

ECG: STE. Echo: 60%. WMA: none. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 2 d, SD | NSAIDs | |

| 52 | 16; M; W; USA | BNT162b2; two | 2: CP, SOB |

TRO: 16.4 CRP: 6.5 |

ECG: STE. Echo: 53%. WMA: LV regional WMA. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 2 d, SD | NSAIDs, IVIG, CCS | |

| 53 | 15; M; W; USA | BNT162b2; two | 3: CP |

TRO: 7.89 CRP: 3.4 |

ECG: normal. Echo: 61%. WMA: none. MRI: patchy subepicardial to transmural edema and LGE in inferior LV free wall | HD stable, no ICU, LOS 2 d, SD | NSAIDs |

A Asian, AV Atrioventricular, BL baseline, CCS corticosteroids, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CP chest pain, CRP C-reactive protein, d day(s), ECG electrocardiogram, Echo echocardiogram, F female, gen generalized, HD hemodynamically, ICU intensive care unit, IVIg intravenous immunoglobulin, LGE late gadolinium enhancement, LOS length of hospital stay, LV left ventricle, M male, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, mRNA messenger RNA, NR not reported, NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSVT non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, PT prothrombin time, RV right ventricle, SD stable discharge, SOB shortness of breath, STD ST-segment depression, STE ST-segment elevation, TRO troponin, TTE trans-thoracic echocardiogram, W white, WMA wall motion abnormality

aLowest ejection fraction

bHypokinesis

Recently, some other interesting studies have resulted in additional findings. A study using the database of Clalit Health Services, the largest healthcare organization in Israel, for diagnoses of myocarditis in patients who had received at least one dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine was published. The estimated incidence of myocarditis was 2.13 cases per 100,000 people. The highest incidence was among male patients between the ages of 16 and 29 years (10.69 cases per 100,000). Most cases of myocarditis were mild or moderate in severity [51]. Another retrospective review of data from Israel obtained from 20 December 2020 to 31 May 2021 and using the Brighton Collaboration definition showed a standardized incidence ratio of post-vaccine myocarditis of 5.34 (95% confidence interval [CI] 4.48–6.40), which was highest after the second dose in male recipients between the ages of 16 and 19 years (13.60; 95% CI 9.30–19.20). In males of all ages, myocarditis occurred at an incidence of 0.64 cases per 100,000 people after the first dose and 3.83 cases per 100,000 after the second dose. The incidence increased to 1.34 and 15.07 per 100,000 after the first and second doses, respectively, for teenage boys aged 16–19 years [52]. Both these studies showed an increased incidence of post-vaccine myocarditis compared with already available data from the CDC. A difference in the number of incidences was noted in these two studies, maybe because of the different data collection methods and differences in criteria for diagnosing myocarditis. Also, both studies could not exclude confounders that also contribute to the incidence of myocarditis. Still, these data highlight a need for further investigation and follow-up.

Another cross-sectional study showed data from 25 children aged 12–18 years diagnosed with probable myopericarditis after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination as per the CDC criteria for diagnosis at eight US centers between 10 May 2021 and 20 June 2021. Most (88%) cases occurred after the second dose of vaccine, and chest pain (100%) was the most common presenting symptom. Patients sought medical attention a median of 2 days after administration of the Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccination [53]. Interestingly, most of these cases were mild and transient.

Given the remarkably similar clinical presentation and the lack of an alternative explanation for a confirmed diagnosis of myocarditis or myopericarditis, only the temporal association with the mRNA vaccine was consistent. None of the reported cases developed a severe form of the disease (as measured by the requirement for inotropes, mechanical support, or heart transplant). All patients were discharged in a stable condition within 1 week of hospitalization. Interestingly, all patients were male, most were Caucasian, all were young (age 16–25 years), and all had no significant cardiovascular comorbidities. The majority of patients had received two doses of the vaccine. The number of vaccine doses administered in the general population was difficult to estimate for each case report, making it challenging to extrapolate an overall incidence of myocarditis in patients receiving mRNA vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 from the available data. However, the incidence of myocarditis demands population-based studies in the future to highlight the complete adverse effect profile of the vaccine. The CDC continues to endorse two doses of vaccine for all individuals, including the population noted to have reported cases of myocarditis or pericarditis [50].

Pathogenesis

Although several case reports and case series on myopericarditis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination exist in the literature, they only establish a temporal relationship between vaccine receipt and development of myopericarditis and fail to demonstrate a conclusive causality. Interestingly, the majority of the cases share some common attributes. Most of the patients developed symptoms of myocarditis within 1–4 days of receiving the second dose of the vaccine. In addition, relatively healthy adolescent or young adult males were commonly affected with a benign clinical course and rapid resolution of symptoms (Table 2). Some cases were also investigated for other possible etiologies of myocarditis, with no alternative cause found [40, 54–56]. Therefore, clustering of similar cases of myopericarditis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination supports a causal association between them, which must be further investigated with larger prospective studies [57]. In most cases, endomyocardial biopsy was not performed because of rapid clinical improvement precluding an etiological diagnosis [33, 35, 40, 45]. However, Larson et al. [38] performed a cardiac biopsy in one patient before initiating steroids, and this did not demonstrate myocardial infiltrates. Therefore, the pathogenesis of myopericarditis post administration of mRNA COVID-19 vaccination is largely speculative.

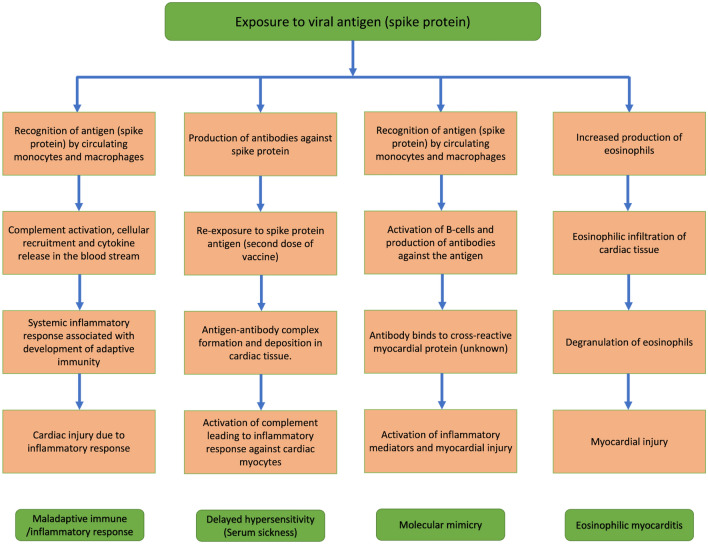

Children developed a more robust immune response than adults during SARS-CoV-2 infection, as demonstrated by multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. In addition, mRNA vaccines produced more potent immunogenicity and reactogenicity in younger recipients and after the second dose. Similarly, the propensity of young adults to develop myocarditis following the second dose of vaccine supports the hypothesis of the vaccine-associated maladaptive immune response causing cardiac injury [35, 38, 45–47, 56, 58]. Recognition of vaccine antigen by circulating monocytes and macrophages activates complements and recruits inflammatory cells, causing cytokine release, resulting in adaptive immunity. This systemic immune response, when exaggerated in predisposed individuals, might cause organ damage [59]. Schauer et al. [46] described two cases of post-vaccine myocarditis in patients with a history of myocarditis in first-degree relatives. In a case report by Minocha et al. [47], an adolescent patient with a history of myocarditis 4 months before vaccination developed recurrent myocarditis with gadolinium enhancement in similar distribution following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Muthukumar et al. [54] demonstrated an increase in a specific natural killer cell subset and multiple autoantibodies in a 52-year-old male with COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis. In contrast, the interleukin-17 level was not raised, unlike other causes of myocarditis. The authors hypothesized that such unique immune changes might be contributing to a specific subtype of vaccine-associated myocarditis with rapid recovery.

On the other hand, the development of symptoms within 1–4 days of the second dose of vaccine could be explained by a delayed hypersensitivity or serum sickness-like reaction. Additionally, patients who developed myocarditis following the first dose had a history of COVID-19 infection. In both cases, initial exposure caused sensitization to viral antigen with subsequent exposure forming antigen–antibody complexes and eventual damage to cardiac myocytes [33, 40, 55, 60].

The high prevalence of myocardial damage in COVID-19, combined with a tiny proportion of myocarditis in mRNA COVID-19 vaccine recipients, indicates the possibility of molecular mimicry between SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and an unknown myocardial protein [33, 38, 58, 61].

Smallpox vaccine and tetanus toxoid vaccine have been found to cause myocardial damage following immunization. Endomyocardial biopsy has demonstrated evidence of eosinophilic myocarditis in such cases [62, 63]. Increased circulating eosinophils produced following immunization infiltrate cardiac tissue. Degranulation of eosinophils causes direct myocardial injury [64]. A similar mechanism might exist in the case of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis. However, the lack of peripheral eosinophilia in a few instances renders this mechanism unlikely [45, 58].

Management

We do not have enough data about COVID-19 vaccine-related myocarditis. Published case reports indicate that the pathogenesis of the COVID-19 vaccine-related myocarditis shares similar mechanisms with COVID-19 infection-related myocarditis [38, 65]. We highlight the management of COVID-19 infection-related myocarditis because treatment options will also be effective in patients with COVID-19 vaccine-related myocarditis. Recently, a systematic review by Sawalha et al. [66] described the treatments available for COVID-19-related myocarditis. In this study, around 50% of the patients required vasopressor support, and 25% required inotropic support. Medical management of myocarditis/myopericarditis included glucocorticoids (being the most used), immunoglobulin therapy, and colchicine [66]. Other studies have also supported the use of corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin in pediatric myocarditis. Studies have shown that intravenous immunoglobulin may improve ventricular systolic function. Temporary cardiac pacing and antiarrhythmic drugs (e.g., lidocaine and mexiletine) have been used to manage arrhythmias in the setting of COVID-19-related myocarditis. Caution must be taken while using antiarrhythmic drugs given the risk for QTc prolongation [65, 67]. The case reports included mainly treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, and colchicine [32, 37]. We also noted the use of β-blockers (bisoprolol) and acetylsalicylic acid in patients with myocarditis after COVID-19 vaccines [33]. In some case reports, the patients required intensive care-level treatment without requiring inotropic agent therapy and were eventually discharged in a hemodynamically stable situation. However, we need more data to assess the clinical course of patients with myocarditis after administration of COVID-19 vaccine [38].

Discussion

The global COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in global lockdowns, the economic collapse of countries, and rising mortality and morbidity. The creation of these vaccines has increased our ability to fight against this disease. With rising vaccination rates, fatal outcomes have decreased significantly. However, recent studies have shown that the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA-based vaccines have been associated with myocarditis and/or myopericarditis as an adverse effect. Figure 1 summarizes the possible pathogenesis of COVID-19 vaccine-related myocarditis [31, 33, 36, 38, 40, 43–46, 49, 50, 54, 56, 57, 59–65]. We note that the pathogenesis of myocardial and pericardial involvement is mainly related to inflammation. This finding is supported by the effective use of anti-inflammatory medication, including steroids, in patients with myopericarditis [38]. Interestingly, the case reports and case series provided evidence of myocardial inflammation and edema on cardiac MRI. Similar findings have been noted in both pediatric and adult cases of myocarditis post administration of COVID-19 vaccines. Although symptoms in all patients resolved rapidly, the potential for myocardial fibrosis and its unknown long-term effects on the heart must be followed-up. The AHA and American College of Cardiology recommendations for acute myocarditis include long-term cardiac surveillance [46]. Follow-up clinical visits and follow-up cardiac imaging for all patients should be considered.

Fig. 1.

Proposed pathogenesis of myopericarditis related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine [31, 33, 36, 38, 40, 43–46, 49, 50, 54, 56, 57, 59–65]

Although incidences of vaccine-related myocarditis are being reported, the established benefits of these vaccines outweigh the rare risk of myocarditis or pericarditis. The extent of myocarditis and pericarditis has been particularly noticeable in young and adolescent males, occurring most often within several days after the second dose of the vaccine. Undoubtedly, this may lead to concern about administering mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines to younger populations. Larson et al. [38] also found very few cases of myocarditis following COVID-19 vaccination, confirmed by cardiac MRI. Most of these cases of vaccine-related myocarditis resolved in a few days with treatment. The potential benefits of these vaccines are well-established, and the potential for systemic organ involvement such as myocarditis or pericarditis should not change vaccine policies [68]. Sweden and Denmark have recently paused the use of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine for younger age groups after reports of possible rare cardiovascular side effects [69]. Certainly, this is the time to think carefully about this potential risk. We believe a more extensive prospective trial is required to establish the causation or to improve estimates of the incidence of myocarditis following COVID-19 vaccination.

Conclusions

COVID-19 infection has been associated with myocarditis. Cases of myopericarditis are also being reported in the setting of COVID-19 vaccines. Although most cases are mild, we must be extremely cautious about the follow-up of these patients. Undoubtedly, COVID-19 vaccines have provided optimism in the fight against this pandemic. At the time of writing, a causal relationship between vaccine receipt and myopericarditis development should not be concluded. Identification of myopericarditis as an adverse event should be investigated and followed-up with high priority. These events should not be a reason to change vaccine policy, but further studies are necessary to alleviate anxiety about and resistance to routine COVID-19 vaccinations.

Declarations

Funding

No external funding was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Adrija Hajra, Manasvi Gupta, Binita Ghosh, Kumar Ashish, Gaurav Manek, Neelkumar Patel, Devesh Rai, Carl J Lavie, and Dhrubajyoti Bandyopadhyay have no potential conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

Availability of data and material

Availability of data and material-available from authors on request.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

AH contributed to the conceptualization, article search, writing, reviewing, and editing. MG contributed to the article search, writing, and editing. BG and KA contributed to the writing and editing. GM, NP, DR, and CJL contributed to the reviewing and editing. DB contributed to the conceptualization, article search, reviewing, and editing.

Footnotes

The original Online version of this article was revised: The co-author’s name was missed in the article and published.

Change history

12/21/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s40256-021-00518-1

Contributor Information

Adrija Hajra, Email: adrija847@gmail.com.

Manasvi Gupta, Email: manasvi.gupta.93@gmail.com.

Binita Ghosh, Email: binita.bmc@gmail.com.

Kumar Ashish, Email: drkumarashish89@gmail.com.

Neelkumar Patel, Email: neelpatel.ny@gmail.com.

Gaurav Manek, Email: Gaurav.manek10@gmail.com.

Devesh Rai, Email: deveshraimd@gmail.com.

Jayakumar Sreenivasan, Email: jayakumars101@gmail.com.

Akshay Goel, Email: dr.akshay.goel@gmail.com.

Carl J. Lavie, Email: clavie@ochsner.org

Dhrubajyoti Bandyopadhyay, Email: drdhrubajyoti87@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surg. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hajra A, Mathai SV, Ball S, Bandyopadhyay D, Veyseh M, Chakraborty S, et al. Management of thrombotic complications in COVID-19: an update. Drugs. 2020;80:1553–1562. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01377-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. https://covid19.who.int

- 4.Lotfi M, Hamblin MR, Rezaei N. COVID-19: transmission, prevention, and potential therapeutic opportunities. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;508:254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao J, Zhao S, Ou J, Zhang J, Lan W, Guan W, et al. COVID-19: coronavirus vaccine development updates. Front Immunol. 2020;11:602256. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.602256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine [Internet]. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine

- 8.Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine [Internet]. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/moderna-covid-19-vaccine

- 9.Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine [Internet]. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/janssen-covid-19-vaccine

- 10.COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States [Internet]. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations

- 11.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meo SA, Bukhari IA, Akram J, Meo AS, Klonoff DC. COVID-19 vaccines: comparison of biological, pharmacological characteristics and adverse effects of Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna Vaccines. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:1663–1669. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202102_24877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CDC COVID-19 Response Team, Food and Drug Administration. Allergic Reactions Including Anaphylaxis After Receipt of the First Dose of Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 21, 2020-January 10, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:125–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.CDC COVID-19 Response Team, Food and Drug Administration. Allergic Reactions Including Anaphylaxis After Receipt of the First Dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 14-23, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Selected Adverse Events Reported after COVID-19 Vaccination [Internet]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/adverse-events.html

- 16.Clinicians reminded to be aware of myocarditis and pericarditis symptoms [Internet]. https://www.health.govt.nz/news-media/media-releases/clinicians-reminded-be-aware-myocarditis-and-pericarditis-symptoms

- 17.Rizk JG, Gupta A, Sardar P, Henry BM, Lewin JC, Lippi G, et al. Clinical characteristics and pharmacological management of COVID-19 vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2021; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Su JR, McNeil MM, Welsh KJ, Marquez PL, Ng C, Yan M, et al. Myopericarditis after vaccination, Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 1990–2018. Vaccine. 2021;39:839–845. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zost SJ, Gilchuk P, Chen RE, Case JB, Reidy JX, Trivette A, et al. Rapid isolation and profiling of a diverse panel of human monoclonal antibodies targeting the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Nat Med. 2020;26:1422–1427. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0998-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He Y, Zhou Y, Liu S, Kou Z, Li W, Farzan M, et al. Receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV spike protein induces highly potent neutralizing antibodies: implication for developing subunit vaccine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:773–781. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The COVID-19 vaccine tracker and landscape compiles detailed information of each COVID-19 vaccine candidate in development by closely monitoring their progress through the pipeline [Internet]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines

- 22.Types of vaccines for COVID-19 [Internet]. https://www.immunology.org/coronavirus/connect-coronavirus-public-engagement-resources/types-vaccines-for-covid-19

- 23.Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) [Internet]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html

- 24.Schlake T, Thess A, Fotin-Mleczek M, Kallen K-J. Developing mRNA-vaccine technologies. RNA Biol. 2012;9:1319–1330. doi: 10.4161/rna.22269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reichmuth AM, Oberli MA, Jaklenec A, Langer R, Blankschtein D. mRNA vaccine delivery using lipid nanoparticles. Ther Deliv. 2016;7:319–334. doi: 10.4155/tde-2016-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahin U, Muik A, Derhovanessian E, Vogler I, Kranz LM, Vormehr M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T cell responses. Nature. 2020;586:594–599. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2814-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comparing the COVID-19 Vaccines: How Are They Different? [Internet]. https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/covid-19-vaccine-comparison

- 29.Different COVID-19 Vaccines [Internet]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines.html?s_cid=11304:best%20vaccine%20for%20covid:sem.ga:p:RG:GM:gen:PTN:FY21

- 30.Menni C, Klaser K, May A, Polidori L, Capdevila J, Louca P, et al. Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:939–949. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00224-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.COVID-19 Vaccine Reporting Systems [Internet]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/reporting-systems.html

- 32.Albert E, Aurigemma G, Saucedo J, Gerson DS. Myocarditis following COVID-19 vaccination. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16:2142–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2021.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Angelo T, Cattafi A, Carerj ML, Booz C, Ascenti G, Cicero G, et al. Myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a vaccine-induced reaction? Can J Cardiol. 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.García JB, Ortega PP, Antonio Bonilla Fernández J, León AC, Burgos LR, Dorta EC Acute myocarditis after administration of the BNT162b2 vaccine against COVID-19. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Mansour J, Short RG, Bhalla S, Woodard PK, Verma A, Robinson X, et al. Acute myocarditis after a second dose of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: a report of two cases. Clin Imaging. 2021;78:247–249. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Habib MB, Hamamyh T, Elyas A, Altermanini M, Elhassan M. Acute myocarditis following administration of BNT162b2 vaccine. IDCases. 2021;25:e01197. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abu Mouch S, Roguin A, Hellou E, Ishai A, Shoshan U, Mahamid L, et al. Myocarditis following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Vaccine. 2021;39:3790–3793. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larson KF, Ammirati E, Adler ED, Cooper LT, Hong KN, Saponara G, et al. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 Vaccination. Circulation. 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Kim HW, Jenista ER, Wendell DC, Azevedo CF, Campbell MJ, Darty SN, et al. Patients With Acute Myocarditis Following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Montgomery J, Ryan M, Engler R, Hoffman D, McClenathan B, Collins L, et al. Myocarditis Following Immunization With mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines in Members of the US Military. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Rosner CM, Genovese L, Tehrani BN, Atkins M, Bakhshi H, Chaudhri S, et al. Myocarditis Temporally Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination. Circulation. 2021;CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.McLean K, Johnson TJ. Myopericarditis in a Previously Healthy Adolescent Male Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case Report. Acad Emerg Med. 2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and Teens [Internet]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/adolescents.html

- 44.Diaz GA, Parsons GT, Gering SK, Meier AR, Hutchinson IV, Robicsek A. Myocarditis and pericarditis after vaccination for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021 Aug 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Marshall M, Ferguson ID, Lewis P, Jaggi P, Gagliardo C, Collins JS, et al. Symptomatic Acute Myocarditis in Seven Adolescents Following Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccination. Pediatrics. 2021 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Schauer J, Buddhe S, Colyer J, Sagiv E, Law Y, Chikkabyrappa SM, et al. Myopericarditis after the Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine in Adolescents. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2021;S002234762100665X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Minocha PK, Better D, Singh RK, Hoque T. Recurrence of Acute Myocarditis Temporally Associated with Receipt of the mRNA Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccine in a Male Adolescent. J Pediatr. 2021;S002234762100617X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Luetkens JA, Faron A, Isaak A, Dabir D, Kuetting D, Feisst A, et al. Comparison of original and 2018 lake louise criteria for diagnosis of acute myocarditis: results of a validation cohort. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2019;1:e190010. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2019190010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Law YM, Lal AK, Chen S, Čiháková D, Cooper LT, Deshpande S, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Myocarditis in Children: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 16];144. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Clinical Considerations: Myocarditis and Pericarditis after Receipt of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines Among Adolescents and Young Adults [Internet]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/myocarditis.html

- 51.Witberg G, Barda N, Hoss S, Richter I, Wiessman M, Aviv Y, Grinberg T, Auster O, Dagan N, Balicer RD, Kornowski R. Myocarditis after Covid-19 Vaccination in a Large Health Care Organization. N Engl J Med. 10.1056/NEJMoa2110737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Mevorach D, Anis E, Cedar N, Bromberg M, Haas EJ, Nadir E, Olsha-Castell S, Arad D, Hasin T, Levi N, Asleh R. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Das BB, Kohli U, Ramachandran P, Nguyen HH, Greil G, Hussain T, Tandon A, Kane C, Avula S, Duru C, Hede S, Sharma K, Chowdhury D, Patel S, Mercer C, Chaudhuri NR, Patel B, Khan D, Ang JY, Asmar B, Sanchez J, Bobosky KA, Cochran CD, Gebara BM, Gonzalez Rangel IE, Krasan G, Siddiqui O, Waqas M, El-Wiher N, Freij BJ. Myopericarditis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in adolescents 12 through 18 years of age. J Pediatr. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muthukumar A, Narasimhan M, Li Q-Z, Mahimainathan L, Hitto I, Fuda F, et al. In-depth evaluation of a case of presumed myocarditis after the second dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Circulation. 2021;144:487–498. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shay DK, Shimabukuro TT, DeStefano F. Myocarditis Occurring After Immunization With mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccines. JAMA Cardiol [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 16]; https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamacardiology/fullarticle/2781600 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Vidula MK, Ambrose M, Glassberg H, Chokshi N, Chen T, Ferrari VA, et al. Myocarditis and Other Cardiovascular Complications of the mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccines. Cureus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 16]; https://www.cureus.com/articles/61030-myocarditis-and-other-cardiovascular-complications-of-the-mrna-based-covid-19-vaccines [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Klein NP, Lewis N, Goddard K, Fireman B, Zerbo O, Hanson KE, et al. Surveillance for Adverse Events After COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination. JAMA [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 16]; https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2784015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Ammirati E, Cavalotti C, Milazzo A, Pedrotti P, Soriano F, Schroeder JW, et al. Temporal relation between second dose BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine and cardiac involvement in a patient with previous SARS-COV-2 infection. IJC Heart Vasc. 2021;34:100774. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2021.100774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hervé C, Laupèze B, Del Giudice G, Didierlaurent AM, Tavares Da Silva F. The how’s and what’s of vaccine reactogenicity. npj Vaccines. 2019;4:39. doi: 10.1038/s41541-019-0132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lawley TJ, Bielory L, Gascon P, Yancey KB, Young NS, Frank MM. A study of human serum sickness. J Investig Dermatol. 1985;85:S129–S132. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12275641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rojas M, Restrepo-Jiménez P, Monsalve DM, Pacheco Y, Acosta-Ampudia Y, Ramírez-Santana C, et al. Molecular mimicry and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2018;95:100–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy JG, Wright RS, Bruce GK, Baddour LM, Farrell MA, Edwards WD, et al. Eosinophilic-lymphocytic myocarditis after smallpox vaccination. The Lancet. 2003;362:1378–1380. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14635-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamamoto H, Hashimoto T, Ohta-Ogo K, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Hiroe M, et al. A case of biopsy-proven eosinophilic myocarditis related to tetanus toxoid immunization. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2018;37:54–57. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuchynka P, Palecek T, Masek M, Cerny V, Lambert L, Vitkova I, et al. Current diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of eosinophilic myocarditis. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2016/2829583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Siripanthong B, Nazarian S, Muser D, Deo R, Santangeli P, Khanji MY, Cooper LT, Jr, Chahal CAA. Recognizing COVID-19-related myocarditis: The possible pathophysiology and proposed guideline for diagnosis and management. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(9):1463–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sawalha K, Abozenah M, Kadado AJ, Battisha A, Al-Akchar M, Salerno C, et al. Systematic review of COVID-19 related myocarditis: insights on management and outcome. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;23:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bandyopadhyay D, Akhtar T, Hajra A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: cardiovascular complications and future implications. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020;20:311–324. doi: 10.1007/s40256-020-00420-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.No serious health effects linked to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines [Internet]. https://www.worldpharmanews.com/research/5790-no-serious-health-effects-linked-to-mrna-covid-19-vaccines

- 69.https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/sweden-pauses-use-moderna-covid-vaccine-cites-rare-side-effects-2021-10-06/. Accessed 10 Nov 2021