Abstract

Inclusion and subsequent reporting of minority participants in clinical trials are critical for ensuring external validity or detecting differences among subgroups, however reports suggest that ongoing gaps persist. ClinicalTrials.gov began requiring the reporting of race/ethnicity information (if collected) during results submission for trials in April 2017. For this study, we downloaded trial race/ethnicity information from ClinicalTrials.gov before (N=3540) and after (N=3542) the requirement date for comparison. Additionally, we examined and compared a 10% random sample of post-requirement trials with corresponding results publications available in PubMed. We found that 42.0% of pre-requirement trials compared to 91.4% of post-requirement trials reported race/ethnicity information in ClinicalTrials.gov; 8.6% of post-requirement trials indicated race/ethnicity information was not collected. Use of NIH/U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) classification categories was similar across pre- and post-requirement samples (68.4% and 70.0%, respectively). In the random sample, 33.1% had a corresponding results publication, of which 62.4% reported race/ethnicity information in the publication. Among trials without published race/ethnicity information, 90.0% reported race/ethnicity information on ClinicalTrials.gov. This analysis demonstrates that the requirement has advanced public availability of information on the inclusion of minorities in research, but that further work remains.

Keywords: Race and Ethnicity, Clinical Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, Results Reporting

Introduction

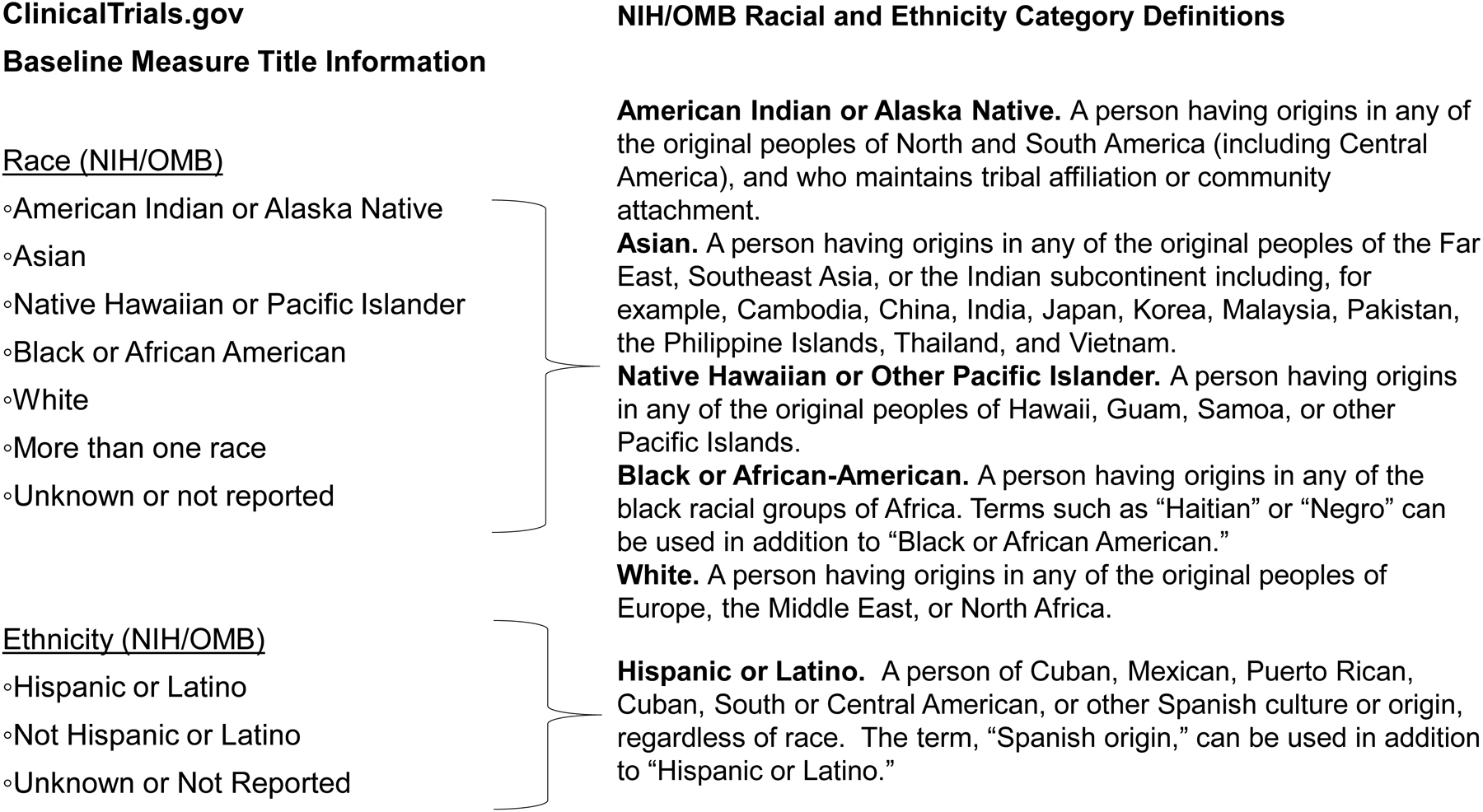

Inclusion and reporting of minority participants in clinical trials are critical for understanding how knowledge gained applies to diverse populations. Recent reports suggest ongoing gaps persist in minority representation and reporting despite efforts to increase both. [1,2] Federal regulations (42 CFR Part 11) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Policy on the Dissemination of NIH-Funded Clinical Trial Information, effective January 18, 2017, require sponsors and investigators to report trial participants’ race/ethnicity (if collected) with results information submitted to ClinicalTrials.gov. [3–5] On the regulations’ compliance date, April 18, 2017, ClinicalTrials.gov began requiring race/ethnicity information with submitted results for trials with a primary completion date (PCD) on or after January 18, 2017, defined as the date the final participant was examined or received an intervention for the purposes of final data collection for the primary outcome. Race/ethnicity information can be reported using standard NIH/OMB classifications or customized categories. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

ClinicalTrials.gov Baseline Measure Title Information for Race and Ethnicity Information (NIH/OMB) and Corresponding Definitions. Definitions of Race and Ethnicity described in NIH NOT-OD-15-089 (April 8, 2015) “Racial and Ethnic Categories and Definitions for NIH Diversity Programs and for Other Reporting Purposes.” (available at https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not-od-15-089.html).

Materials and Methods

On December 2, 2019, we downloaded records for trials with posted results and at least one location in the United States. We restricted the sample in this way because relevant race/ethnicity categories were potentially different for studies conducted in other countries. The “post-requirement” sample included 3542 records listing a PCD on or after January 18, 2017 and results first submitted on or after April 18, 2017. The “pre-requirement” convenience sample included 3540 records with a PCD before January 18, 2017 and results first submitted between June 1, 2016, and April 17, 2017. We assessed and compared race/ethnicity reporting in both samples using the “Baseline Measure Title” field. From a 10% random sample of post-requirement records indicating customized race/ethnicity reporting (n=74; “customized-reporting” sample), we assessed category descriptions. In another 10% random sample of post-requirement records (n=354; “publication” sample), we identified trials with corresponding results publications in PubMed using previously reported methods and assessed how participant race/ethnicity were reported. [6]

Results

Among pre-requirement trials, 42.0% (1488/3540) reported race/ethnicity information in ClinicalTrials.gov compared to 91.4% (3239/3542) among post-requirement trials (8.6% indicated not collected). (Table 1) Use of NIH/OMB categories was similar among pre- and post-requirement samples (68.4% and 70.0%, respectively).

Table 1.

Categories of race and/or ethnicity reporting in the “Baseline Measure Title” of the ClinicalTrials.gov record for two samples of registered clinical trials with at least one United States location.

| Categories of Reporting | Pre-Requirement Sample* | Post-Requirement Sample† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Records (No. records (% total)) | Records (No. records (% total)) | Publication Subset (No. publications (%total)) | |

| Race and/or Ethnicity Information Reported | 1488 (42.0) | 3239 (91.4) | 73 (62.4) |

| NIH/OMB | 1018 (68.4) | 2267 (70.0) | ‡ |

| Customized | 405 (27.2) | 741 (22.9) | ‡ |

| NIH/OMB and Customized | 65 (4.4) | 231 (7.1) | ‡ |

| Race and Ethnicity Not Collected | 46 (1.3) | 303 (8.6) | Unknown |

| Race and Ethnicity Information Not Reported | 2006 (56.7) | 0 (0) | 44 (37.6) |

| Total | 3540 | 3542 | 117 |

Includes clinical trial records with a primary completion date before January 18, 2017 and results first submitted between June 1, 2016 and April 17, 2017 and posted by December 2, 2019.

Includes clinical trial records with a primary completion date on or after January 18, 2017 and results first submitted on or after April 18, 2017 and posted by December 2, 2019. The publication subset was derived from a 10% random sample of the post-requirement sample (n = 354), of which 117 of the 354 clinical trial records had a corresponding publication used in this analysis.

Publications did not specify.

Within the customized-reporting sample, 95.9% (71/74) reported race and 52.7% reported ethnicity information. Although most records (61/74) used category names that differed from (e.g., “Other”) or were more specific than (e.g., “East Asian”) NIH/OMB classifications, many (55/61) also included category names matching NIH/OMB classifications (e.g., “White”). The remaining records (13/74) only used category names matching selected NIH/OMB classifications.

Within the publication sample, 33.1% (117/354) had a corresponding results publication and 62.4% (73/117) of those trials reported race/ethnicity information in the publication (Table 1). Among trials in this sample without race/ethnicity information in a publication, 90.0% (253/281) also reported race/ethnicity information in the corresponding ClinicalTrials.gov record. Although many publications (64/73) used NIH/OMB classification terms (e.g., “Hispanic or Latino”), no publication explicitly referenced the NIH/OMB standard.

Conclusions

The new requirements for reporting race/ethnicity to ClinicalTrials.gov reinforce the importance of collecting and reporting this information. This analysis shows that public disclosure of race/ethnicity information has increased beyond what was previously available in ClinicalTrials.gov and what is available in publications, allowing for further insights into the inclusion of minorities in research and considerations of racial and ethnic disparities in health. Less than 10% of post-requirement trials indicated race/ethnicity information was not collected, suggesting the lack of reporting among 57% of pre-requirement trials was due largely to non-reporting rather than absence of collection. Frequent use of standard NIH/OMB categories across both samples facilitates common understanding and comparisons of such information across trials and with other resources. Use of only customized categories makes such comparisons challenging. Furthermore, race/ethnicity information labeled with an NIH/OMB classification might not have been collected using the NIH/OMB standard. While our analysis did not assess representation of racial and ethnic groups in clinical trials, it demonstrates how the growing corpus of structured trial information in ClinicalTrials.gov provides opportunities to further optimize and reinforce reporting of race/ethnicity and social determinants of health and to support further research in this area.

Acknowledgement:

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda MD.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Fain worked on this research and article while employed with the National Library of Medicine, NIH. He is currently employed with the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This article reflects the views of the author and should not be construed to represent FDA’s views or policies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

References

- [1].Hooper MW, Nápoles AM, & Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities. JAMA. May 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [2].National Institutes of Health. NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. 2017. Available at https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities/guidelines.htm (accessed on November 15, 2019)

- [3].NIH Policy on the Dissemination of NIH-Funded Clinical Trial Information. 2017. Available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/21/2016-22379/nih-policy-on-the-dissemination-of-nih-funded-clinical-trial-information (accessed on November 15, 2019)

- [4].National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical trials registration and results information submission: final rule. Fed Regist 2016; 81: 64981–5157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, Carr S. Trial reporting in ClinicalTrials.gov - the final rule. N Engl J Med. 2016. November 17;375(20):1998–2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ross et al. Publication of NIH funded trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional analysis. BMJ. 2012; 344:d7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]