Significance

Estrogen receptor α (ER-α) mediates estrogen-dependent cancer progression and is expressed in most breast cancer cells. We now show that calcineurin, a Ca2+-dependent protein phosphatase, plays a previously unrecognized role in the regulation of ER-α stability and activity. Calcineurin stabilizes ER-α by mediating its dephosphorylation at Ser294 and thereby preventing its degradation by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Calcineurin mediates ER-α activation by promoting its phosphorylation at Ser118 by mTOR. A high level of calcineurin gene expression was also found to be associated with a poor prognosis of ER-α–positive breast cancer patients treated with endocrine therapeutic agents. We therefore propose that the selective inhibition of calcineurin might be an effective approach to the treatment of ER-α–positive breast cancer.

Keywords: calcineurin, estrogen receptorα, breast cancer, ubiquitination

Abstract

Estrogen receptor α (ER-α) mediates estrogen-dependent cancer progression and is expressed in most breast cancer cells. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of the cellular abundance and activity of ER-α remain unclear. We here show that the protein phosphatase calcineurin regulates both ER-α stability and activity in human breast cancer cells. Calcineurin depletion or inhibition down-regulated the abundance of ER-α by promoting its polyubiquitination and degradation. Calcineurin inhibition also promoted the binding of ER-α to the E3 ubiquitin ligase E6AP, and calcineurin mediated the dephosphorylation of ER-α at Ser294 in vitro. Moreover, the ER-α (S294A) mutant was more stable and activated the expression of ER-α target genes to a greater extent compared with the wild-type protein, whereas the extents of its interaction with E6AP and polyubiquitination were attenuated. These results suggest that the phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser294 promotes its binding to E6AP and consequent degradation. Calcineurin was also found to be required for the phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser118 by mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 and the consequent activation of ER-α in response to β-estradiol treatment. Our study thus indicates that calcineurin controls both the stability and activity of ER-α by regulating its phosphorylation at Ser294 and Ser118. Finally, the expression of the calcineurin A–α gene (PPP3CA) was associated with poor prognosis in ER-α–positive breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen or other endocrine therapeutic agents. Calcineurin is thus a promising target for the development of therapies for ER-α–positive breast cancer.

Estrogen receptor α (ER-α) plays a central role in the proliferation of breast cancer cells by increasing the expression of oncogenes, such as those encoding cyclin D1 and c-Myc (1). The expression and activity of ER-α are increased in >70% of breast cancer cases, and the receptor is targeted by drugs such as tamoxifen (2, 3). A substantial proportion of ER-α–positive breast cancer cells become resistant to anti‐estrogens, however, resulting in the progression of the disease. The mechanisms by which the cancer cells acquire resistance to these agents include the generation of splice variants of ER-α, the mutation of the ER-α gene (ESR1), and changes in stability of the ER-α protein (4).

Increased protein stability appears to be a key contributor to the up-regulation of ER-α in breast cancer. The ubiquitination of ER-α is one mechanism responsible for ER-α degradation. Several E3 ligases that mediate the degradation of ER-α have been identified and include E6-associated protein (E6AP) (5), carboxyl terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP) (6), breast cancer type 1 (BRCA1) (7), BRCA1-associated RING domain 1 (8), S phase kinase–associated protein 2 (SKP2) (9), and mouse double minute 2 homolog (10). On the other hand, other E3 ligases—such as RING finger protein (RNF) 31, shank-associated RH domain–interacting protein, and RNF8 (11–13)—have been shown to promote ER-α signaling by stabilizing ER-α protein.

The residues Lys302 and Lys303 of ER-α are targeted for ubiquitination (14). The ubiquitination of ER-α is associated with its phosphorylation, with several kinases such as cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 11 (15), Src (5), protein kinase C (16), p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (9), and extracellular signal–regulated kinase 7 (17) having been shown to phosphorylate the protein. The phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser294 has thus been related to its ubiquitination by SKP2 (9), with the Ser294-phosphorylated form of ER-α being a preferred substrate for ubiquitination by SKP2 in vitro. However, the expression level of ER-α was found to be unaltered in cells depleted of SKP2, suggesting that other E3 ligases may contribute to the degradation of ER-α subsequent to its phosphorylation at Ser294.

Calcium is an important regulator of signaling pathways that control oncogenesis and cancer progression, and Ca2+ signaling has been linked to signaling by ER-α. β-estradiol (E2) has been shown to induce rapid Ca2+ influx in cells, and the Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin interacts with ER-α, increases its stability, and modulates E2-regulated gene expression (18). Calcineurin is a Ca2+/calmodulin-activated serine–threonine phosphatase that plays a major role in the regulation of immediate cellular responses and gene expression by Ca2+ signaling (19). It is also a target of immunosuppressive drugs administered in clinical practice, such as cyclosporine A and FK506. Calcineurin is composed of two subunits: a catalytic subunit, designated calcineurin A, that is encoded by three genes (PPP3CA, PPP3CB, and PPP3CC), and a regulatory subunit, designated calcineurin B, that is encoded by two genes (PPP3R1 and PPP3R2).

In the present study, we found that calcineurin plays a previously unrecognized role as a positive regulator of the stability and activity of ER-α in breast cancer cells by mediating its dephosphorylation at Ser294, as well as the activation of mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and the consequent phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser118, respectively. Furthermore, a high-expression level of PPP3CA was associated with poor prognosis in a subset of breast cancer patients, suggesting that the selective inhibition of calcineurin might be an effective approach to the treatment of ER-α–positive breast cancer.

Results

Calcineurin Regulates the Stability of ER-α.

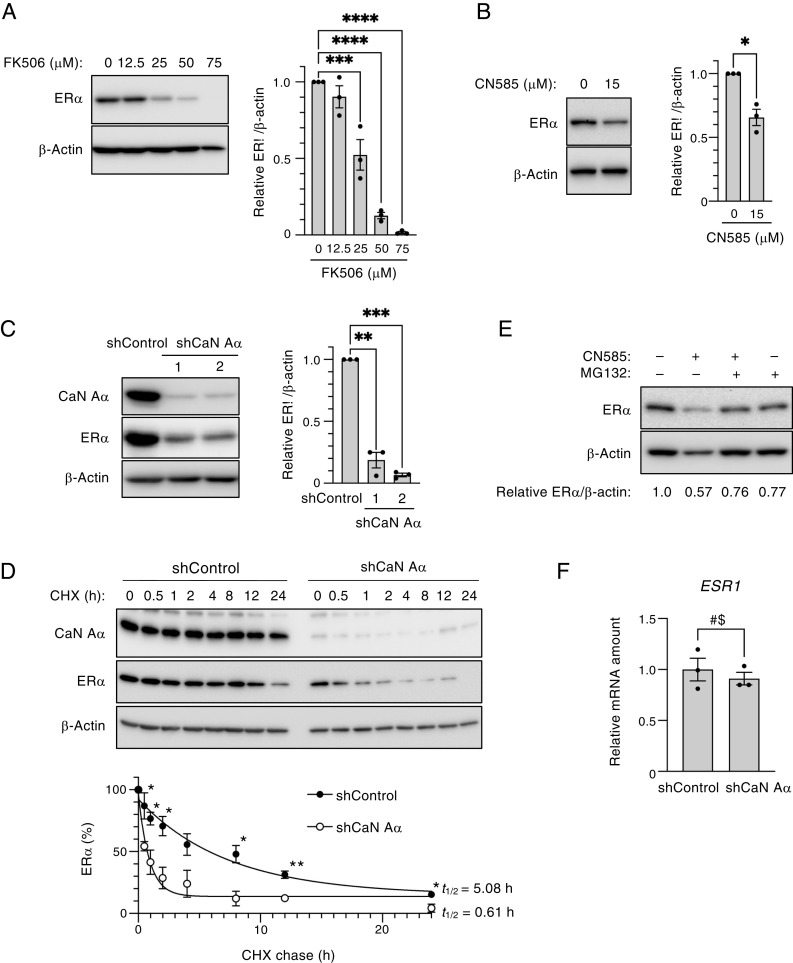

We first investigated the effect of the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 on ER-α expression, given that the calcineurin–NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cells) pathway is activated in invasive breast cancer cells (20). Immunoblot analysis revealed that FK506 treatment attenuated the expression of ER-α in MCF7 human breast cancer cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Given that FK506 inhibits not only calcineurin but FK506-binding proteins, we also examined the effect of CN585, which specifically inhibits calcineurin phosphatase activity. Treatment with CN585 also resulted in a loss of ER-α in MCF7 cells (Fig. 1B). Moreover, we found that FK506 or CN585 induced the down-regulation of ER-α in the human breast cancer cell lines T47D and BT-474 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A–C). To examine further whether calcineurin is required for ER-α expression, we depleted calcineurin A–α with two independent lentivirus-delivered short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs). The depletion of calcineurin A–α resulted in a significant decrease in ER-α abundance in MCF7 cells (Fig. 1C), as well as in T47D (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D) and BT-474 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E) cells. With the use of a cycloheximide chase assay, we also found that ER-α protein stability was decreased in calcineurin-depleted MCF7 cells compared with control cells (Fig. 1D). To investigate whether the down-regulation of ER-α induced by CN585 was attributable to the degradation of the protein by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, we examined the effect of the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Indeed, the treatment of MCF7 cells (Fig. 1E) or T47D cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F) with MG132 attenuated the loss of ER-α induced by CN585. RT-qPCR analysis showed that the amount of ESR1 messenger RNA (mRNA) did not differ significantly between control and calcineurin-depleted MCF7 cells (Fig. 1F), suggesting that the decrease in ER-α expression induced by calcineurin depletion was attributable to regulation at the protein (not mRNA) level. Collectively, these findings indicated that calcineurin inhibits ER-α degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway.

Fig. 1.

Calcineurin stabilizes ER-α in MCF7 cells. (A) MCF7 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of FK506 for 24 h, after which total cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ER-α and to β-actin (loading control). A representative immunoblot as well as the relative ER-α/β-actin band intensity ratio determined as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments are shown. ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001 (Dunnett’s test). (B) MCF7 cells were treated with CN585 (0 or 15 μM) for 5 h, after which cell lysates were prepared and analyzed as in A. The quantitative data are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (paired t test). (C) Lentivirus-infected MCF7 cells were cultured in the presence of Dox for 3 d to induce the expression of calcineurin A–α (shCaN A–α) or luciferase (shControl) shRNAs. Two different calcineurin A–α shRNAs (1, 2) were used. Cell lysates were then prepared and analyzed as in A, with the addition that the immunoblot analysis was also performed with antibodies to calcineurin A–α (CaN A–α). The quantitative data are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (Dunnett’s test). (D) Cycloheximide (CHX) chase analysis of ER-α in MCF7 cells depleted of calcineurin A–α by exposure to Dox for 2 d, as in C. The Dox-treated cells were thus incubated with CHX (50 μg/mL) for the indicated times, after which cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. The percentage of ER-α remaining after the various chase times was quantitated as mean ± SEM values from three independent experiments, and the half-life (t1/2) of ER-α was determined. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus the corresponding value for calcineurin-depleted cells (unpaired t test). (E) MCF7 cells were treated with CN585 (30 μM) or MG132 (10 μM) for 6 h, after which cell lysates were analyzed as in A. Data are from a representative experiment. (F) Lentivirus-infected MCF7 cells were cultured in the presence of Dox for 3 d to induce the expression of control or calcineurin A–α shRNAs, after which total RNA was isolated from the cells and subjected to RT-qPCR analysis of ESR1 mRNA. Data are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. NS, not significant (unpaired t test).

Calcineurin Inhibits the Ubiquitination of ER-α Mediated by E6AP.

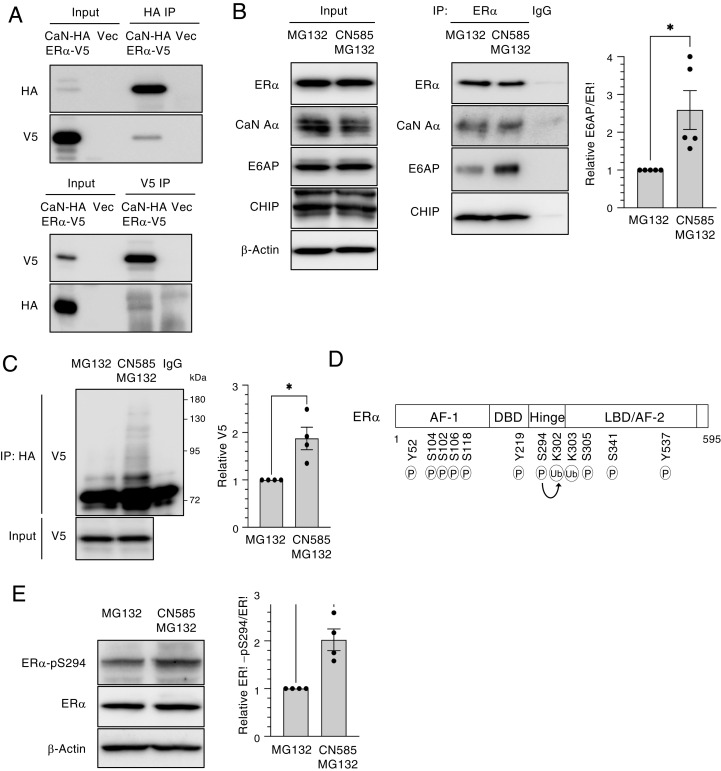

To examine the potential association of ER-α and calcineurin, we transiently transfected human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells with expression vectors for V5-tagged ER-α and hemagglutinin epitope (HA)–tagged calcineurin A–α. The reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation analysis of the cell lysates with antibodies to the V5- or HA-tags revealed that ER-α indeed interacts with calcineurin A–α (Fig. 2A). We next investigated whether calcineurin inhibition affects the interaction of ER-α with its known E3 ligases, and we found that the extent of the association of ER-α with E6AP was greater in MCF7 cells treated with CN585 and MG132 than in those treated with MG132 alone (Fig. 2B). The association of ER-α with the E3 ligase CHIP appeared unaffected by CN585 treatment, suggesting that the promotion of the binding of ER-α to E6AP might be responsible, at least in part, for the degradation of ER-α induced by calcineurin inhibition. To investigate further the mechanism by which calcineurin modulates the level of ER-α, we analyzed the ubiquitination state of ER-α in CN585- and MG132-treated HEK293T cells. CN585 treatment increased the ubiquitination level of ER-α in MG132-treated cells (Fig. 2C). Given that the degradation of ER-α dependent on ubiquitination was previously shown to be associated with its phosphorylation state, and that Lys302 and Lys303 residues of ER-α have been found to be ubiquitinated, we focused on Ser294 phosphorylation, which is known to enhance the ubiquitination of ER-α (9) (Fig. 2D). We therefore examined whether CN585 treatment induced the degradation of ER-α as a result of the increased phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser294. We found that Ser294 phosphorylation was increased twofold in MCF7 cells treated with CN585 and MG132 compared with that in cells treated with MG132 alone (Fig. 2E), suggesting that CN585 inhibits the dephosphorylation of ER-α. Together, these results thus indicated that the inhibition of calcineurin increases the phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser294 and thereby promotes its binding to E6AP and consequent degradation.

Fig. 2.

Calcineurin inhibits the ubiquitination (Ub) of ER-α by E6AP. (A) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors for HA-tagged calcineurin A–α (CaN-HA) and V5 epitope–tagged ER-α (ER-α–V5) or with the corresponding empty vector (Vec) for 2 d, after which total cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with antibodies to HA or to V5. The resulting immunoprecipitants as well as a portion of the original cell lysates (Input) were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the same antibodies. (B) MCF7 cells were treated with MG132 (10 μM) in the absence or presence of CN585 (30 μM) for 5 h, after which cell lysates were subjected to IP with antibodies to ER-α or with control immunoglobulin G (IgG). The resulting immunoprecipitants as well as a portion of the Input were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ER-α, to calcineurin A–α, to E6AP, and to CHIP. The relative E6AP/ER-α band intensity ratio for the ER-α immunoprecipitants was determined as the mean ± SEM from five independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (paired t test). (C) HEK293T cells transiently transfected with expression vectors for HA-tagged ubiquitin (obtained from T. Ohta) and ER-α–V5 for 2 d were treated with MG132 in the absence or presence of CN585 for 6 h. Cell lysates were then prepared and subjected to IP with antibodies to HA or control IgG. The resulting immunoprecipitants as well as a portion of the Input were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to V5. The V5 band intensity was determined as the mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (paired t test). (D) Functional domains of human ER-α. The transactivation domains (AF-1 and AF-2), DNA-binding domain (DBD), ligand-binding domain (LBD), and the hinge domain that links LBD and DBD are shown together with residues that are modified by phosphorylation (P) or Ub. The P of Ser294 has been associated with Ub. (E) MCF7 cells were treated with MG132 in the absence or presence of CN585 for 18 h, after which cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to total or Ser294-phosphorylated (pS294) forms of ER-α. The relative phosphorylated/total ER-α band intensity ratio was determined as the mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (paired t test).

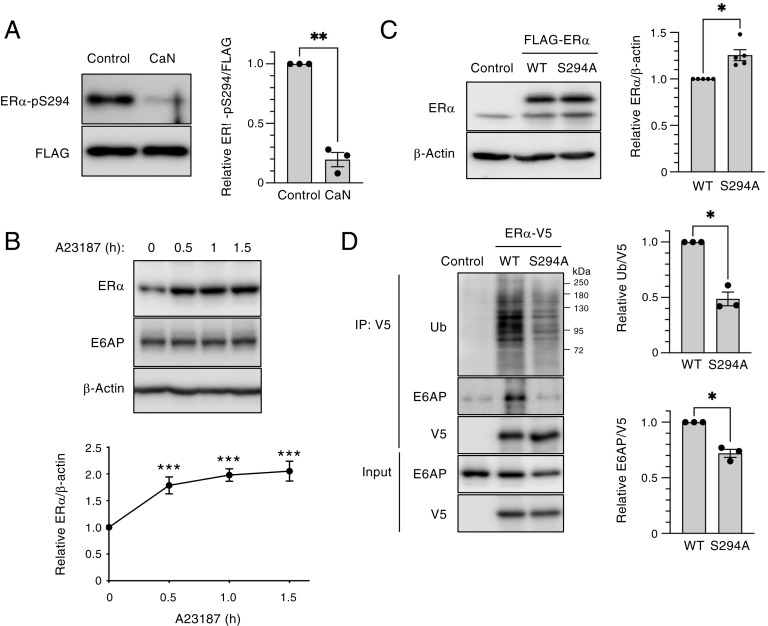

We next performed a phosphatase assay to investigate whether calcineurin might dephosphorylate ER-α in vitro. Purified recombinant calcineurin combined with calmodulin indeed mediated the dephosphorylation of ER-α at Ser294 (Fig. 3A). We also examined whether the activation of calcineurin increases the abundance of endogenous ER-α. The treatment of MCF7 cells with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187, which activates calcineurin by mediating the influx of extracellular Ca2+, indeed increased the expression of ER-α (Fig. 3B). Given that the phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser294 enhances the ubiquitination of ER-α in vitro (9), we generated a nonphosphorylatable mutant of ER-α by replacing Ser with Ala at position 294 (S294A). The S294A mutant was more stable than wild-type (WT) ER-α in MCF7 cells (Fig. 3C). The interaction of the S294A mutant with E6AP and its ubiquitination in HEK293T cells were both attenuated compared with those of the WT protein (Fig. 3D). These results suggested that the destabilization of ER-α through Ser294 phosphorylation is a key determinant of ER-α abundance. Calcineurin thus dephosphorylates ER-α at Ser294, which abrogates its binding to E6AP and consequent ubiquitination and degradation.

Fig. 3.

Calcineurin (CaN) stabilizes ER-α through dephosphorylation at Ser294. (A) Phosphatase assay performed with immunoprecipitated, FLAG-tagged ER-α with or without recombinant CaN and calmodulin. The reaction mixtures were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to Ser294-phosphorylated ER-α and to FLAG. The relative phosphorylated ER-α/FLAG band intensity ratio was determined as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. **P < 0.01 (paired t test). (B) MCF7 cells were treated with 4 μM A23187 for the indicated times, after which total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. The relative ER-α/β-actin band intensity ratio was determined as mean ± SEM values from four independent experiments. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus the corresponding value for time 0 (Dunnett’s test). (C) MCF7 cells were transiently transfected with empty vector or expression vectors for FLAG-tagged S294A mutant or WT forms of ER-α for 2 d, after which cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ER-α. The relative ER-α/β-actin band intensity ratio was determined as mean ± SEM values from five independent experiments. P < 0.05 (paired t test). (D) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors for V5-tagged WT or S294A mutant forms of ER-α for 2 d, after which cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with antibodies to V5. The resulting immunoprecipitants as well as a portion of the original cell lysates (Input) were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ubiquitin (Ub), to E6AP, and to V5. The relative Ub/V5 and E6AP/V5 band intensity ratios were determined as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. P < 0.05 (paired t test).

Calcineurin Depletion Attenuates ER-α Signaling.

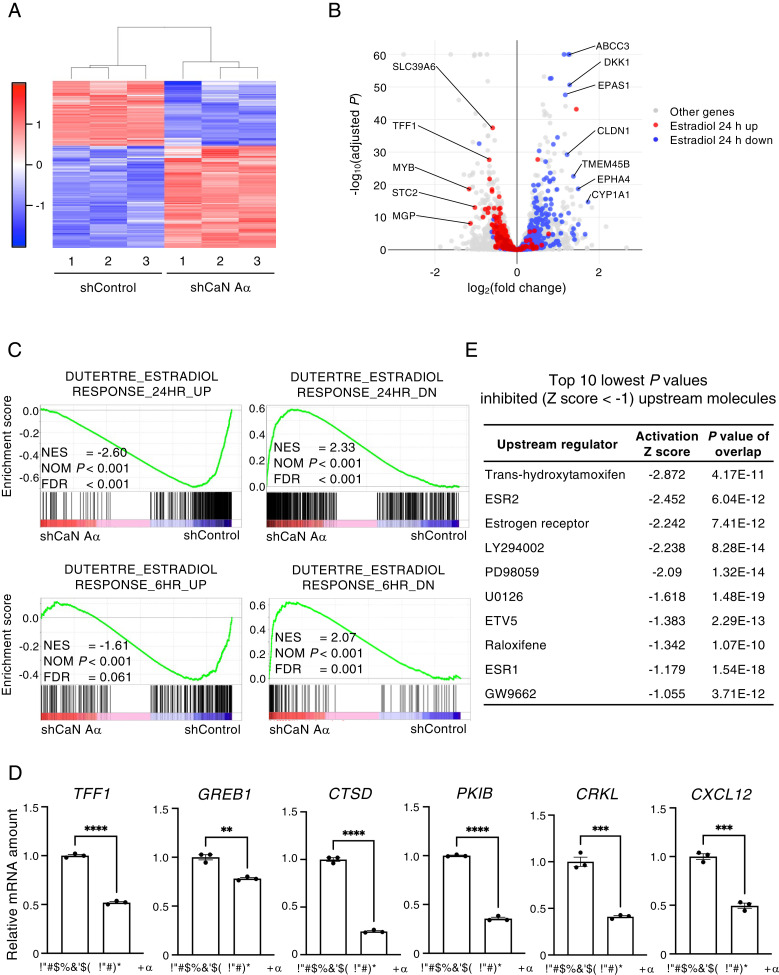

To investigate further the role of calcineurin in the regulation of ER-α signaling, we performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis for calcineurin A–α-depleted and control MCF7 cells, and we thereby identified 643 differentially expressed genes (DEGs)—394 up-regulated genes and 249 down-regulated genes in the former cells compared with the latter (Fig. 4A). Volcano plot analysis showed that genes up-regulated or down-regulated by calcineurin depletion were enriched in those whose expression is decreased or increased by E2 treatment, respectively (Fig. 4B). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) also revealed that the expression of genes up-regulated early (6 h) or late (24 h) in response to estradiol was decreased by calcineurin depletion, whereas that of those down-regulated early (6 h) or late (24 h) in response to estradiol was increased by calcineurin depletion (Fig. 4C). We also validated these results with RT-qPCR analysis by showing that the expression of genes up-regulated by estradiol was decreased by calcineurin depletion (Fig. 4D). Consistent with these findings, ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) for the identified DEGs implicated the estrogen receptor as a down-regulated upstream molecule in cells depleted of calcineurin A–α (Fig. 4E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). We also analyzed the global gene expression profile of cyclosporine A–treated HBL-1 human diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells (GSE140882) (21) and found that calcineurin inhibition down-regulated the expression of ER-α target genes in these cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Collectively, these findings suggested that calcineurin promotes ER-α signaling.

Fig. 4.

Calcineurin depletion inhibits ER-α signaling. (A) Heat map showing the expression of 643 DEGs in three replicate samples of MCF7 cells expressing luciferase (shControl) or calcineurin A–α (shCaN A–α) shRNAs, as determined by RNA-seq analysis. The amount of change in gene expression (z-score) for each sample is displayed as red (high) or blue (low) shading. (B) Volcano plot analysis for all genes detected by the RNA-seq analysis. Red and blue dots indicate genes belonging to the gene sets DUTERTRE_ESTRADIOL_RESPONSE_24HR_UP and DUTERTRE_ESTRADIOL_RESPONSE_24HR_DN, respectively. Fold change refers to expression in calcineurin-depleted cells relative to that in control cells. (C) GSEA for the indicated gene sets in the calcineurin-depleted and control cells. NES, normalized enrichment score; NOM, nominal; and FDR, false discovery rate. (D) RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of ER-α target genes in the calcineurin A–α-depleted and control MCF7 cells. Data are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 (unpaired t test). (E) Inhibited (z-score of <–1) upstream molecules with the top 10 lowest P values identified by the IPA upstream regulator analysis of the DEGs revealed by RNA-seq analysis of the calcineurin-depleted and control MCF7 cells.

Calcineurin Promotes E2-Induced ER-α Activation and ER-α–Mediated Gene Expression.

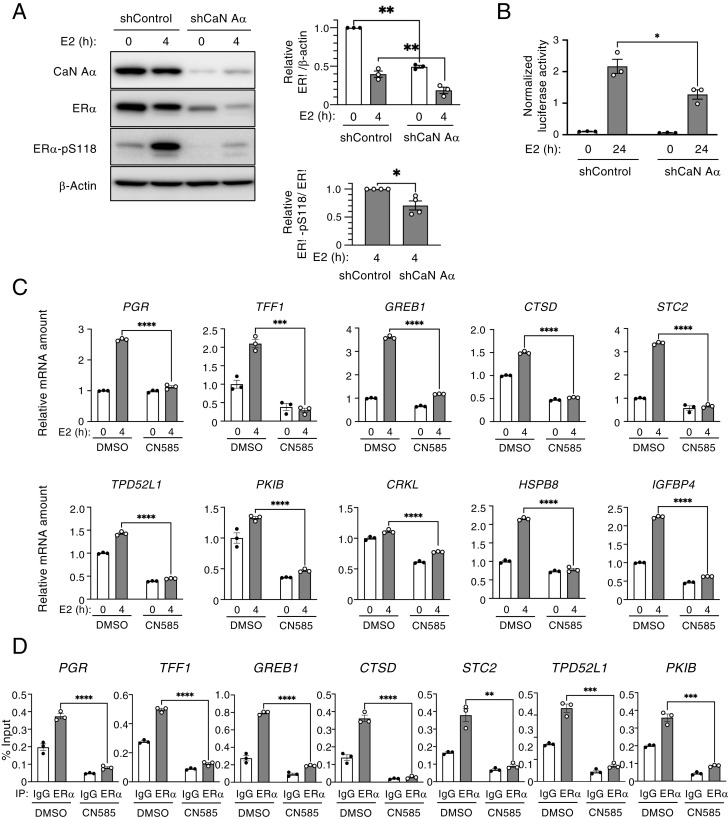

We next investigated whether calcineurin might affect the activation of ER-α in addition to stabilizing the protein. We therefore examined the effect of E2 treatment on the phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser118, which increases the transactivation activity of the protein (22) in calcineurin A–α-depleted and control MCF7 cells. In control cells, E2 treatment for 4 h increased the phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser118, whereas this effect was substantially attenuated in cells depleted of calcineurin A–α, indicating that calcineurin is required for ER-α activation (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained with T47D cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A) and BT-474 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Given that the amount of ER-α was decreased in calcineurin-depleted cells, we confirmed that ER-α activation was also decreased in T47D cells treated with CN585 alone or with both CN585 and MG132 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). We also examined the effect of calcineurin depletion on ER-α–mediated gene transactivation with the use of a luciferase reporter assay. The depletion of calcineurin attenuated E2-induced reporter gene expression in MCF7 cells (Fig. 5B). To examine the effect of calcineurin inhibition on the E2-induced expression of endogenous ER-α target genes, we performed RT-qPCR analysis for T47D cells treated with CN585. The E2-induced expression of representative ER-α target genes was significantly inhibited by CN585 treatment (Fig. 5C). Similar results were obtained for calcineurin-depleted MCF7 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Furthermore, chromatin immunoprecipitation–qPCR analysis revealed that the E2-induced recruitment of ER-α to target gene promoters in T47D cells was greatly attenuated by treatment with CN585 (Fig. 5D). These results thus suggested that calcineurin promotes the association of ER-α with its target genes.

Fig. 5.

Calcineurin regulates ER-α activation. (A) Lentivirus-infected MCF7 cells were exposed to Dox in a medium containing charcoal-stripped serum for 3 d to induce the expression of control or calcineurin A–α (CaN A–α) shRNAs. The cells were then treated (or not) with 10 nM E2 for 4 h, after which total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to CaN A–αand to total or Ser118-phosphorylated (pS118) forms of ER-α. The relative ER-α/β-actin and ER-α–pS118/ER-α band intensity ratios were determined as mean ± SEM values from three or four independent experiments, respectively. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (paired t test). (B) MCF7 cells expressing the Dox-inducible luciferase (shControl) or shCaN A–α shRNAs were transiently transfected with an estrogen response element–luciferase reporter plasmid and then treated (or not) with E2 in a medium containing charcoal-stripped serum for 24 h, after which luciferase activity was measured in cell lysates. Data are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (unpaired t test). (C) T47D cells that had been cultured in a medium containing charcoal-stripped serum for 2 d were incubated first with CN585 (30 μM) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle for 2 h and then in the additional absence or presence of E2 for 4 h. Total RNA was then isolated from the cells and subjected to the RT-qPCR analysis of expression of the indicated ER-α target genes. Data are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001 (unpaired t test). (D) chromatin immunoprecipitation–qPCR (ChIP-qPCR) analysis of T47D cells treated as in C. After stimulation with E2 for 4 h, the cells were subjected to the ChIP-qPCR analysis of the binding of ER-α to promoter regions of its indicated target genes. Data are expressed as a percentage of the input chromatin and are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 (unpaired t test).

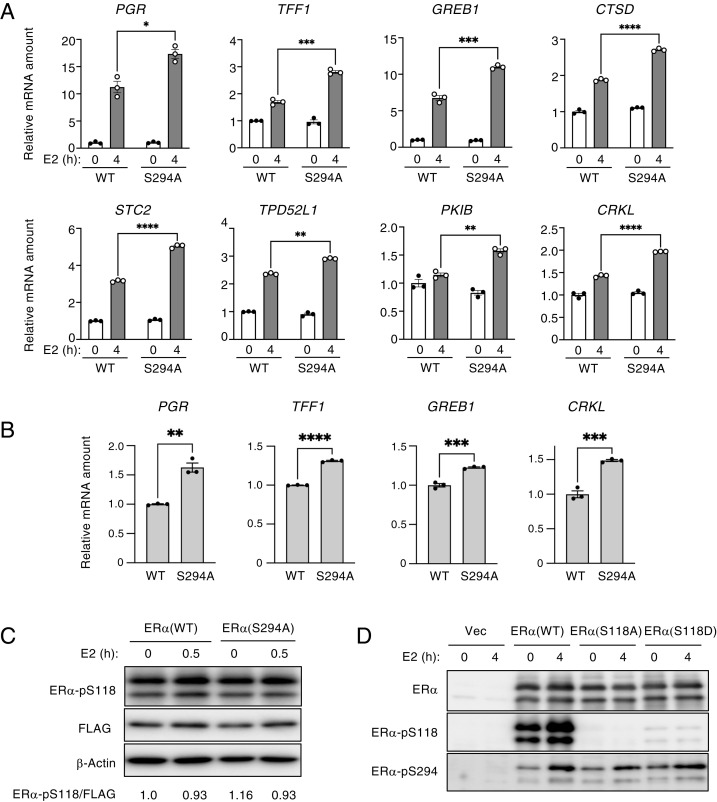

We examined the potential role of Ser294 dephosphorylation in E2-induced gene expression by RT-qPCR analysis. The expression of shRNA-resistant forms of FLAG-tagged ER-α (WT or S294A) in ER-α–depleted MCF7 cells revealed that ER-α (S294A) enhanced the expression of ER-α target genes compared with that apparent in cells expressing ER-α (WT) (Fig. 6 A and B). To investigate the relation between Ser294 and Ser118 phosphorylation, we expressed FLAG-tagged forms of ER-α (S294A), the nonphosphorylatable mutant ER-α (S118A), or the phosphomimetic mutant ER-α (S118D) in MCF7 cells and examined the phosphorylation status of ER-α. The expression of ER-α (S294A) had no effect on the Ser118 phosphorylation of ER-α (Fig. 6C), and the expression of ER-α (S118A) or ER-α (S118D) did not affect the Ser294 phosphorylation of ER-α (Fig. 6D), suggesting that the phosphorylation of these two residues is each independent of that or the other. Collectively, our results indicated that calcineurin promotes ER-α activation, ER-α recruitment to its target genes, and ER-α–mediated gene expression through Ser294 dephosphorylation.

Fig. 6.

The ER-α (S294A) mutant promotes the transcription of ER-α target genes. (A) Lentivirus-infected MCF7 cells were exposed to Dox in a medium containing charcoal-stripped serum to induce the expression of an ER-α shRNA as well as transiently transfected with a vector for shRNA-resistant FLAG–ER-α (WT or S294A) for 2 d and were then treated (or not) with 10 nM E2 for 4 h. Total RNA isolated from the cells was subjected to the RT-qPCR analysis of the indicated ER-α target gene mRNAs. The RT-qPCR data are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 (unpaired t test). (B) Lentivirus-infected MCF7 cells were exposed to Dox to induce the expression of an ER-α shRNA as well as transiently transfected with a vector for shRNA-resistant FLAG–ER-α (WT or S294A) for 2 d, after which expression of ER-α target genes was determined as in A. Data are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 (unpaired t test). (C) MCF7 cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors for FLAG-tagged WT or S294A mutant forms of ER-α in a medium containing charcoal-stripped serum for 2 d and were then stimulated (or not) with E2 for 30 min, after which cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. The relative ER-α–pS118/FLAG band intensity ratio was determined. Data are from a representative experiment. (D) MCF7 cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors for FLAG-tagged WT, S118A, or S118D forms of ER-α (or with the corresponding empty vector, Vec) in a medium containing charcoal-stripped serum for 2 d and were then stimulated (or not) with E2 for 4 h, after which cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies.

Calcineurin Regulates mTORC1 Activation.

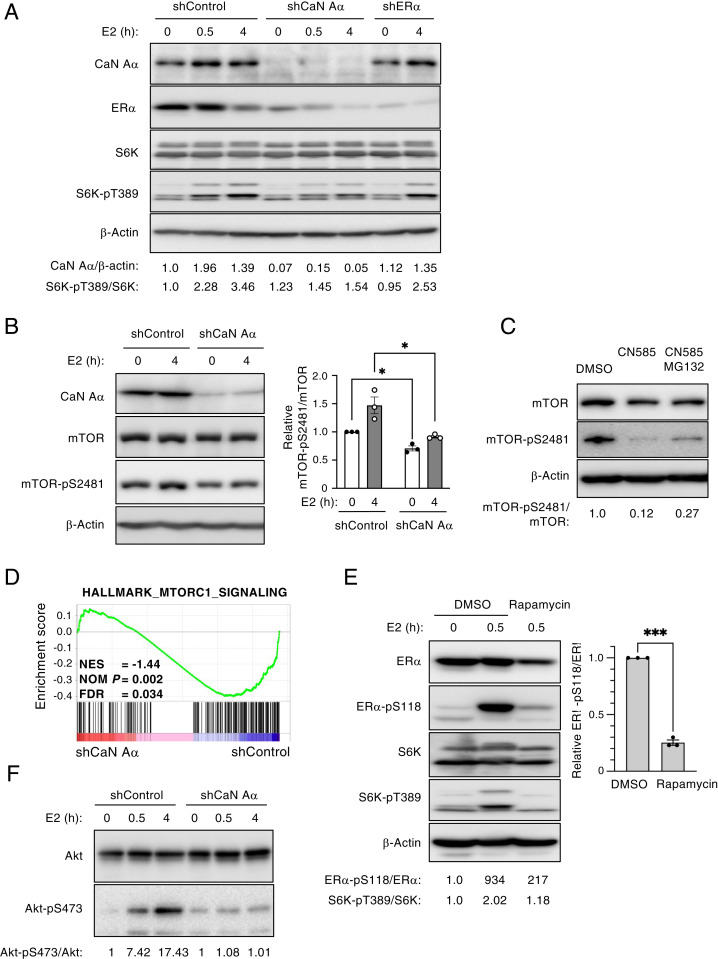

The expression of calcineurin A–α was found to be increased by the E2 treatment in MCF7 cells, and this up-regulation was independent of ER-α status (Fig. 7A). Given that mTORC1 was previously shown to directly phosphorylate and activate ER-α in response to estrogen stimulation—in particular, through the phosphorylation of Ser104 and Ser106 (23)—we examined whether the inhibition of calcineurin might affect mTOR activity. We focused on S6 kinase (S6K), a downstream substrate of mTORC1, and confirmed that S6K was activated in response to E2 stimulation in MCF7 cells (Fig. 7A), as shown previously (24). In contrast, the phosphorylation of both S6K and mTOR was attenuated in calcineurin-depleted MCF7 cells compared with control cells, suggesting that mTORC1 signaling was inhibited by calcineurin depletion (Fig. 7 A and B). In addition, the inhibition of the phosphatase activity of calcineurin with CN585 attenuated the activation of mTOR, as reflected by its phosphorylation at Ser2481 in E2-treated T47D cells (Fig. 7C). Indeed, the GSEA of our RNA-seq data revealed that calcineurin depletion markedly inhibited mTORC1 signaling in MCF7 cells (Fig. 7D). Given that mTORC1 phosphorylates ER-α at Ser104 and Ser106 (23), it seemed possible that it might also be required for the phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser118. To provide further insight into the mechanism of mTORC1-mediated ER-α activation, we examined the effects of the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin on ER-α phosphorylation at Ser118. We confirmed that rapamycin inhibited the phosphorylation of S6K in E2-treated MCF7 cells. In addition, rapamycin treatment reduced the levels of both ER-α phosphorylation at Ser118 and ER-α protein (Fig. 7E), suggesting that mTORC1 is required for ER-α activation dependent on Ser118 phosphorylation. We also found that Akt, an upstream kinase of mTOR, was activated by E2 treatment in MCF7 cells and that this activation was markedly attenuated by calcineurin depletion (Fig. 7F). Collectively, these results indicated that calcineurin contributes to mTORC1 activation, which is required for ER-α activation.

Fig. 7.

Calcineurin regulates mTOR activation. (A) Lentivirus-infected MCF7 cells were exposed to Dox in a medium containing charcoal-stripped serum to induce the expression of calcineurin A–α (CaN A–α), ER-α, or control shRNAs for 2 d and were then stimulated with 10 nM E2 for the indicated times. Total cell lysates were then subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to CaN A–α, to ER-α, and to total or Thr389-phosphorylated forms of S6K. The relative CaN A–α/β-actin and S6K-pT389/S6K band intensity ratios were determined. Data are from a representative experiment. (B) MCF7 cells depleted of CaN A–α and stimulated with E2 for 4 h were lysed and subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies as in A. The relative mTOR-pS2481/mTOR band intensity ratio was determined as mean ± SEM values from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (paired t test). (C) T47D cells were cultured in a medium containing charcoal-stripped serum and treated with CN585 (30 μM) or DMSO vehicle in the absence or presence MG132 (10 μM) for 2 h. They were then stimulated with E2 for 5 h, after which cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies, and the relative mTOR-pS2481/mTOR band intensity ratio was determined. Data are from a representative experiment. (D) GSEA with the HALLMARK_MTORC1_SIGNALING gene set for RNA-seq data obtained from CaN A–α-depleted and control MCF7 cells as in Fig. 4C. NES, normalized enrichment score; NOM, nominal; and FDR, false discovery rate. (E) MCF7 cells were cultured in a medium containing charcoal-stripped serum and treated with rapamycin (10 μM) or DMSO vehicle for 12 h before stimulation with E2 for 0 or 0.5 h. Total cell lysates were then subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. The relative ER-α–pS118/ER-α and S6K-pT389/S6K band intensity ratios for the representative blot are shown and that for ER-α–pS118/ER-α was also determined as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 (paired t test). (F) MCF7 cells depleted of CaN A–α and stimulated with E2 for the indicated times were lysed and subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies as in A. The relative Akt-pS473/Akt band intensity ratio was determined. Data are from a representative experiment.

Expression of PPP3CA Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Endocrine Therapy.

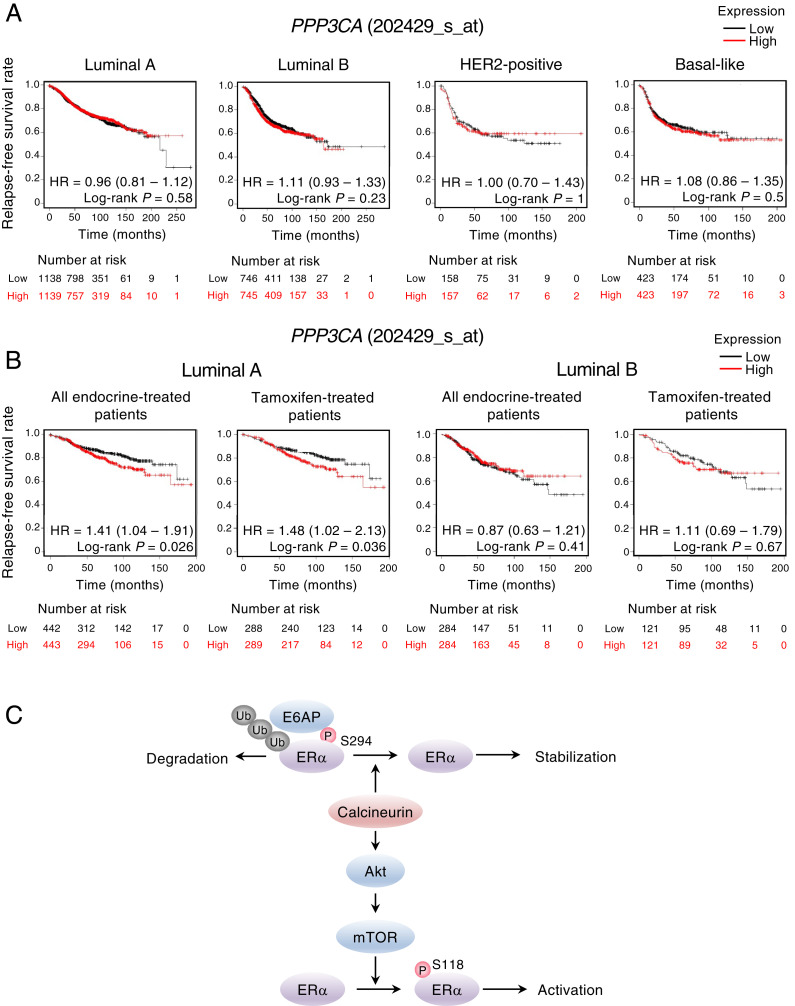

Finally, we examined whether the expression of the calcineurin A–α gene (PPP3CA) might be associated with the survival of breast cancer patients by the univariate analysis of relapse-free survival with the use of publicly available datasets and the Kaplan–Meier plotter platform (42). We found that PPP3CA expression was not significantly related to prognosis for individuals with different types of breast cancer (Fig. 8A). On the other hand, the high expression of PPP3CA was significantly associated with a poor prognosis in patients with luminal A–type breast cancer who received endocrine therapy or were treated specifically with tamoxifen (Fig. 8B). No such association was apparent between PPP3CB (calcineurin A–β gene) expression and the outcome of patients with the various types of breast cancer or of those with ER-α–positive breast cancer who underwent endocrine therapy or treatment with tamoxifen (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Fig. 8.

A high level of PPP3CA expression is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with luminal A–type breast cancer treated with endocrine therapy or tamoxifen. (A and B) Relapse-free survival according to the expression of PPP3CA (202429_s_at) was determined for patients with different breast cancer types in clinical cohorts acquired from the Kaplan–Meier plotter database. The analysis was performed for patients regardless of the treatment received (A) or for those with luminal A– or luminal B–type breast cancer who received endocrine therapy or treatment with tamoxifen (B). High- and low-PPP3CA expression were divided at the median. The hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% CI are shown together with the two-tailed log-rank P value. (C) Model for the regulation of ER-α expression and activity by calcineurin. Calcineurin dephosphorylates ER-α at Ser294, which inhibits ER-α degradation mediated by E6AP. Calcineurin also contributes to ER-α activation by estrogen through mTOR activation. Ub, ubiquitination: P, phosphorylation.

Discussion

ER-α controls the expression of genes related to cell proliferation and is thus a therapeutic target in breast cancer. We have now shown that calcineurin promotes ER-α signaling through the regulation of both the expression and activation of ER-α.

The degradation of ER-α by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway is dependent on its phosphorylation state. E2 induces ER-α phosphorylation at several residues including Ser118 (25), Ser294 (9), Ser341 (25), and Tyr537 (9), and such phosphorylation promotes the recruitment of E3 ligases or coactivators to promote the ER-α degradation or activation of its target genes, respectively. For example, E2 induces the phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser118 by multiple kinases and CDK7 as well as that at Tyr537 by Src, with the phosphorylation of each of these residues leading to the polyubiquitination of ER-α by E6AP and its consequent degradation (26).

We here show that the dephosphorylation of ER-α at Ser294 by calcineurin is a key determinant of its stability and activity. The ubiquitin ligase SKP2 was previously shown to mediate the ubiquitination of ER-α phosphorylated at Ser294 (9). However, cells depleted of SKP2 did not show the altered expression of ER-α, suggesting that other E3 ligases might contribute to the degradation of ER-α phosphorylated at Ser294. We found that the ER-α (S294A) mutant showed reduced levels of interaction with E6AP and ubiquitination, as well as activated the expression of ER-α target genes to a greater extent compared with the WT protein. We therefore conclude that Ser294 phosphorylation promotes the binding of ER-α to E6AP and its consequent degradation. Binding to calmodulin in the presence of Ca2+ is required for calcineurin activation. Calmodulin was also previously shown to control the stability and activity of ER-α through an unknown mechanism (18). Our results now suggest that calmodulin likely regulates ER-α through its calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation.

We also found that calcineurin contributes to mTORC1 activation by E2. The activation of mTORC1 by E2 results in the phosphorylation of ER-α on Ser104 and Ser106 (23). We now show that the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin inhibited ER-α phosphorylation at Ser118, which is required for ER-α activation. Our results therefore suggest that mTORC1 activates ER-α, at least in part, through phosphorylation at Ser118 and that calcineurin contributes to this regulation. Calcineurin inhibitors were previously shown to attenuate the phosphorylation of Akt and its substrates by reducing the expression of insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2), an upstream regulator of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–Akt pathway (27). We also found that calcineurin depletion inhibited E2-induced Akt activation. Although the mechanism by which calcineurin controls mTORC1 activity is unknown, calcineurin may regulate IRS2 expression and thereby activate Akt and mTORC1 in breast cancer cells.

On the basis of our present results, we propose a model according to which calcineurin regulates ER-α signaling by two distinct pathways (Fig. 8C). Calcineurin dephosphorylates ER-α at Ser294, which induces its dissociation from E6AP and consequent stabilization. In addition, calcineurin contributes to the activation of mTORC1 by E2, which promotes the phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser118 and thereby increases its transcriptional activity.

Endocrine therapy with selective estrogen receptor modulators, such as tamoxifen, is effective for ER-α–positive breast cancer (2, 3). However, the development of resistance to such therapy is a major problem, with increased stability of ER-α being one mechanism of such resistance. Estrogen signaling and its physiological effects thus play a central role in breast cancer (14). Our study now indicates that calcineurin prevents the degradation of ER-α by mediating its dephosphorylation at Ser294 and dissociation from E6AP, with the consequent stabilization of ER-α possibly contributing to endocrine therapy resistance. Consistent with this notion, we found that the expression of PPP3CA (which encodes calcineurin A–α) was associated with the poor prognosis of ER-α–positive breast cancer patients on endocrine therapy or treated with tamoxifen.

Phosphorylation is a key mechanism for the regulation of protein function. Emerging evidence suggests that protein dephosphorylation by calcineurin may play an important role in tumor formation and progression (28). Indeed, the increased expression of calcineurin has been associated with the development and progression of several cancer types including breast cancer (20), with the depletion or inhibition of calcineurin having been found to attenuate the growth of breast cancer cells (29). Our present study now identifies calcineurin as a central modulator of ER-α signaling in human breast cancer cells, implicating calcineurin as a promising target to overcome endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Lentivirus Generation and Infection.

Lentivirus generation and infection were performed as described previously (30). In brief, lentiviruses encoding shRNAs were generated by the transfection of HEK293T cells with pCMV-VSV-G-RSV-RevB and pCAG-HIVgp (from Hiroyuki Miyoshi, RIKEN BioResource Center, Tsukuba, Japan and with the corresponding CS-RfA-ETBsd vector with the use of polyethylenimine Max Polyscience). Cells infected with the lentiviruses were treated with blasticidin (A1113903, Gibco) at 10 μg/mL for 2 d. Doxycycline (Dox) (D9891, Sigma-Aldrich) was added to culture medium at 1 μg/mL to induce shRNA expression. The target sequences for the shRNAs were 5'-GCGTATATGATGCCTGTATGG-3'', 5'-GCCAAGGGCTTAGACCGAATT-3'', 5'-CGCTCTAAGAAGAACAGCC-3'', and 5'-CGTGCGTGGAATGCTTCGA-3'' for calcineurin A–α 1 and 2, ER-α, and luciferase, respectively.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis.

Immunoblot analysis was performed essentially as described previously (31). Cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, suspended in sample buffer (2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 100 μM dithiothreitol, 0.1% bromophenol blue, and 50 mM Tris·HCl at pH 6.8), and boiled for 5 min. For immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation kinase buffer (50 mM Hepes-NaOH at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% Tween-20, and 10% glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitors (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, leupeptin, pepstatin A, and aprotinin), and the lysates were incubated with FLAG-M2 agarose (A2220, Sigma-Aldrich) or immunoprecipitation performed with carious antibodies for 1 h at 4 °C with rotation. Raw digital images of immunoblots were captured with the ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad), and band intensities were quantified with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad). The half-life of ER-α was calculated according to the exponential one-phase decay equation in nonlinear regression with the use of GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software) and taking into account the band intensity of β-actin. All primary antibodies are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1.

E2 Treatment.

Cells were cultured in minimum essential medium α (41061-029, Gibco) supplemented with 5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (A3382101, Gibco) for the indicated times before exposure to E2 (E8875, Sigma) at 10 nM.

RT-qPCR Analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from cells, as described previously (32), with the use of ISOGEN II (311-07361, Nippon Gene) and was subjected to RT with random primers and the use of a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (4368814, ABI). The resulting complementary DNA was subjected to qPCR analysis with FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (11226200, Roche) and a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The abundance of target mRNAs was normalized by that of 18S ribosomal RNA. Primer sequences are provided in SI Appendix, Table S2.

Phosphatase Assay.

A phosphatase assay was performed as previously described (33). FLAG–ER-α was immunoprecipitated from transfected MCF7 cells with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (A2220, Sigma-Aldrich) and then eluted with FLAG peptide (F4799, Sigma-Aldrich) in the assay buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl at pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, and bovine serum albumin at 1 μg/mL). It was then incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with or without recombinant human calcineurin (3160-CA, R&D Systems) and calmodulin (208670, Merck) in an assay buffer before immunoblot analysis.

RNA-seq Analysis.

MCF7 cells expressing control or calcineurin A–α shRNAs after culture with Dox for 2 d were subjected to total RNA extraction with the use of an RNeasy Mini Kit (74106, Qiagen). The RNA integrity number was measured with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer for evaluation of RNA quality. Poly(A)+ RNA was then isolated with the use of a NEBNext Poly (A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (E7490, New England BioLabs [NEB]), and a cDNA library was prepared with a NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (E7770, NEB). The cDNA was ligated with NEBNext Adaptor (E7335, NEB), amplified by PCR, and sequenced with the NextSEq. 500 system (SY-415–1001, Illumina). Raw reads were processed by fastp version 0.20.1 (34) for trimming and quality control. Reads were aligned to human reference cDNAs (GRCh38.p13) and counted with Salmon version 1.4.0 (35). Tximport version 1.16.1 (36) was applied to provide transcript-level estimates for gene-level analyses. Raw counts were used to perform quality control (Fig. 4 A and B) with DEBrowser version 1.16.2 (37). GSEA was conducted with Signal2Noise values for all detected genes and for the indicated comparisons as the ranking metric and with the use of GSEA software version 4.1.0 (38) and C2 version 7.2 in the Molecular Signatures Database (39). DEGs were determined as those with an absolute value of log2 (fold change) of >0.5 and adjusted P value of <0.05 by application of the Wald test in DESeq2 version 1.28.1 (40), and they were subjected to IPA (41) (Qiagen).

Statistical Analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed with the data obtained from at least three biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 9. Quantitative data are represented as the mean ± SEM and were analyzed with the paired or unpaired t test for the comparison of two groups or by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test for comparisons among three or more groups. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Kaplan–Meier plots of relapse-free survival, based on the expression of PPP3CA (202429_ s_at) or PPP3CB (202432_at), were generated with the Kaplan–Meier plotter (42). The following conditions were modified from the default: Intrinsic subtype (basal/luminal A/luminal B/HER2+); patients with following systemic treatment: endocrine therapy (include/tamoxifen only). All datasets available in May 2021 were used for the analysis.

Other detailed information is described in SI Appendix.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Kawasaki for technical assistance; M. Iizuka (Teikyo University) for providing an ER-α expression vector; M. Okada (Tokyo University of Technology) for providing firefly and Renilla luciferase constructs; T. Ohta (St. Marianna University School of Medicine) for providing an HA–ubiquitin expression vector; H. Miyoshi (Riken) for providing lentivirus expression vector; and K. Nakayama (Kyusyu University), T. Ohama, and S. Shibutani of the Yamaguchi University Project for Formation of the Core Research Center for discussion. This study was supported by Research Fellowships of the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant Nos. 18H02681 and 20K21503 to M.S.) and Fusion Oriented REsearch for disruptive Science and Technology to M.S.), Yamaguchi University Project for Formation of the Core Research Center (M.S.), and Grants from MSD (Merck Sharp and Dohme) Life Science Foundation, Public Interest Incorporated Foundation, and NOVARTIS Foundation (Japan) for the Promotion of Science (M.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2114258118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

RNA-seq raw reads have been submitted to the DNA Data Bank of Japan Sequence Read Archive (DRA)/The National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (SRA)/European Bioinformatics Institute Sequence Read Archive (ERA) databases under accession number DRA011729 (43). All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Change History

November 3, 2021: The figures has been updated.

References

- 1.Mawson A., et al., Estrogen and insulin/IGF-1 cooperatively stimulate cell cycle progression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells through differential regulation of c-Myc and cyclin D1. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 229, 161–173 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahlman-Wright K., et al., International union of pharmacology. LXIV. Estrogen receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 58, 773–781 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan V. C., O’Malley B. W., Selective estrogen-receptor modulators and antihormonal resistance in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 5815–5824 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeselsohn R., Buchwalter G., De Angelis C., Brown M., Schiff R., ESR1 mutations—A mechanism for acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 12, 573–583 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun J., Zhou W., Kaliappan K., Nawaz Z., Slingerland J. M., ERα phosphorylation at Y537 by Src triggers E6-AP-ERα binding, ERα ubiquitylation, promoter occupancy, and target gene expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 26, 1567–1577 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan M., Park A., Nephew K. P., CHIP (carboxyl terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein) promotes basal and geldanamycin-induced degradation of estrogen receptor-alpha. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 2901–2914 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eakin C. M., Maccoss M. J., Finney G. L., Klevit R. E., Estrogen receptor alpha is a putative substrate for the BRCA1 ubiquitin ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 5794–5799 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashizume R., et al., The RING heterodimer BRCA1-BARD1 is a ubiquitin ligase inactivated by a breast cancer-derived mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 14537–14540 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt S., Xiao Z., Meng Z., Katzenellenbogen B. S., Phosphorylation by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase promotes estrogen receptor α turnover and functional activity via the SCF(Skp2) proteasomal complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 1928–1943 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saji S., et al., MDM2 enhances the function of estrogen receptor alpha in human breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 281, 259–265 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhuang T., et al., SHARPIN stabilizes estrogen receptor α and promotes breast cancer cell proliferation. Oncotarget 8, 77137–77151 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu J., et al., The atypical ubiquitin ligase RNF31 stabilizes estrogen receptor α and modulates estrogen-stimulated breast cancer cell proliferation. Oncogene 33, 4340–4351 (2014). Correction in: Oncogene 38, 299–300 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang S., et al., RNF8 identified as a co-activator of estrogen receptor α promotes cell growth in breast cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1863, 1615–1628 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tecalco-Cruz A. C., Ramírez-Jarquín J. O., Polyubiquitination inhibition of estrogen receptor alpha and its implications in breast cancer. World J. Clin. Oncol. 9, 60–70 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y., et al., Repression of estrogen receptor alpha by CDK11p58 through promoting its ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. J. Biochem. 145, 331–343 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsaud V., Gougelet A., Maillard S., Renoir J.-M., Various phosphorylation pathways, depending on agonist and antagonist binding to endogenous estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha), differentially affect ERalpha extractability, proteasome-mediated stability, and transcriptional activity in human breast cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 2013–2027 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henrich L. M., et al., Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 7, a regulator of hormone-dependent estrogen receptor destruction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 5979–5988 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z., Joyal J. L., Sacks D. B., Calmodulin enhances the stability of the estrogen receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 17354–17360 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H., Rao A., Hogan P. G., Interaction of calcineurin with substrates and targeting proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 91–103 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quang C. T., et al., The calcineurin/NFAT pathway is activated in diagnostic breast cancer cases and is essential to survival and metastasis of mammary cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1658 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bucher P., et al., Targeting chronic NFAT activation with calcineurin inhibitors in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 135, 121–132 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Goff P., Montano M. M., Schodin D. J., Katzenellenbogen B. S., Phosphorylation of the human estrogen receptor. Identification of hormone-regulated sites and examination of their influence on transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 4458–4466 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alayev A., et al., mTORC1 directly phosphorylates and activates ERα upon estrogen stimulation. Oncogene 35, 3535–3543 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maruani D. M., et al., Estrogenic regulation of S6K1 expression creates a positive regulatory loop in control of breast cancer cell proliferation. Oncogene 31, 5073–5080 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajbhandari P., et al., Pin1 modulates ERα levels in breast cancer through inhibition of phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination and degradation. Oncogene 33, 1438–1447 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou W., Slingerland J. M., Links between oestrogen receptor activation and proteolysis: Relevance to hormone-regulated cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 26–38 (2014). Correction in: Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 146 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soleimanpour S. A., et al., Calcineurin signaling regulates human islet beta-cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 40050–40059 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peuker K., et al., Epithelial calcineurin controls microbiota-dependent intestinal tumor development. Nat. Med. 22, 506–515 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goshima T., et al., Calcineurin regulates cyclin D1 stability through dephosphorylation at T286. Sci. Rep. 9, 12779 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimada M., et al., Essential role of autoactivation circuitry on Aurora B-mediated H2AX-pS121 in mitosis. Nat. Commun. 7, 12059 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwata T., et al., The G2 checkpoint inhibitor CBP-93872 increases the sensitivity of colorectal and pancreatic cancer cells to chemotherapy. PLoS One 12, e0178221 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goshima T., et al., Mammal-specific H2A variant, H2ABbd, is involved in apoptotic induction via activation of NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 11656–11666 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimada M., Haruta M., Niida H., Sawamoto K., Nakanishi M., Protein phosphatase 1γ is responsible for dephosphorylation of histone H3 at Thr 11 after DNA damage. EMBO Rep. 11, 883–889 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., Gu J., fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patro R., Duggal G., Love M. I., Irizarry R. A., Kingsford C., Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soneson C., Love M. I., Robinson M. D., Differential analyses for RNA-seq: Transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000 Res. 4, 1521 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kucukural A., Yukselen O., Ozata D. M., Moore M. J., Garber M., DEBrowser: Interactive differential expression analysis and visualization tool for count data. BMC Genomics 20, 6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subramanian A., et al., Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liberzon A., et al., The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 1, 417–425 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S., Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krämer A., Green J., Pollard J. Jr, Tugendreich S., Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 30, 523–530 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Györffy B., et al., An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 123, 725–731 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.M. Habara, M. Shimada, Transcriptome data of MCF7 cells expressing doxycycline-inducible PPP3CA and control shRNAs. DNA Data Bank of Japan. https://ddbj.nig.ac.jp/public/ddbj_database/dra/fastq/DRA011/DRA011729/ Deposited 15 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq raw reads have been submitted to the DNA Data Bank of Japan Sequence Read Archive (DRA)/The National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (SRA)/European Bioinformatics Institute Sequence Read Archive (ERA) databases under accession number DRA011729 (43). All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.