Abstract

Background

Patients discharged to the ward from an intensive care unit (ICU) commonly experience a reduction in mobility but few mobility interventions. Barriers and facilitators for mobilisation on acute wards after discharge from an ICU were explored.

Design and methods

A human factors analysis was undertaken using the Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM) as part of the Recovery Following Intensive Care Treatment (REFLECT) study. A FRAM focus group was formed from members of the ICU and ward multidisciplinary teams from two hospitals, with experience of working in six hospitals. They identified factors influencing mobilisation and the interdependency of these factors.

Results

Patients requiring discharge assessments or on Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathways compete for priority with post-ICU patients with more urgent rehabilitation needs. Patients unable to stand and step to a chair or requiring mobilisation equipment were deemed particularly susceptible to missing mobilisation interventions. The ability to mobilise was perceived to be highly influenced by multidisciplinary staffing levels and skill mix. These factors are interdependent in facilitating or inhibiting mobilisation.

Conclusions

This human factors analysis of post-ICU mobilisation highlighted several influencing factors and demonstrated their interdependency. Future interventions should focus on mitigating competing priorities to ensure regular mobilisation, target patients unable to stand and step to a chair on discharge from ICU and create robust processes to ensure suitable equipment availability.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN14658054

Keywords: Mobilisation, Human factors, Intensive care, Critical care, Physiotherapy

Introduction

The physical consequences of critical illness and immobility are well documented and can be severe and long lasting [1]. These problems commonly translate into a long term loss of function and independence [2], with subsequent negative consequences for the individual, families, wider society [3], [4] and economy [5]. Recommendations for individualised rehabilitation and regular assessment following critical illness have been in place in the UK for 10 years. The recommendations encompass intensive care unit (ICU) admission to three months after hospital discharge [6].

Studies investigating physical rehabilitation following critical illness have, so far, primarily focused on rehabilitation within the ICU [7], [8]. However, following discharge from ICU to the ward environment, patients commonly experience a decrease in their mobility level compared to that achieved on the ICU, even with an improvement in their clinical condition [9]. Despite this, there have been very few studies investigating inpatient ward physical rehabilitation interventions following discharge from ICU [10]. However low mobility levels in hospital post-ICU have previously been observed [10], [11].

To the authors knowledge, there has been no investigation to date exploring why mobilising patients after discharge from ICU is problematic. A Human Factors approach was chosen (Functional Resonance Analysis Method – FRAM) to allow us to look in depth at complex non-linear work processes, applying a systems philosophy and approach [12].

This work is part of the wider REFLECT research programme, examining post-ICU ward care [13]. Within this study failure to mobilise patients following discharge from ICU was identified as a problem in post-ICU care delivery. The aim of this study was to explore the processes involved in post-ICU mobilisation through a human factors analysis, to inform future service improvement.

Methods

Human factors methodology

Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM) is a technique used to model complex socio-technical systems [12]. It focuses on the documentation of work as done rather than work as imagined [14]. A FRAM describes the functions that together make up the performance of a system, as well at their dependencies [15].

The preliminary focus in applying the FRAM methodology is to identify what happens when the right outcome is achieved rather than what is missing when the wrong outcome occurs, prior to describing the functions that define the activity and how they are linked. These links can be described as either up or down-stream to describe their relationship. Each function is then described in terms of its aspect:

-

1.

Input (I) is what the function acts on or changes (an input is also used to start the function).

-

2.

Output (O) is what emerges from the function (this can be an outcome or a state change).

-

3.

Precondition (P) is a condition that must be satisfied before the function can be commenced.

-

4.

Resources (R) are materials or people needed to carry out the function or material consumed during the function.

-

5.

Control (C) is how the function is monitored or controlled.

-

6.

Time (T) refers to any time constraints that might affect completing the function.

The discussion caused by generating the FRAM is often the greatest instigator of the eventual conclusions.

Stakeholder focus group

Purposive sampling was used to select members of staff from two hospitals but with experience of other hospitals to participate in the FRAM focus group to ensure a breadth of experience and characteristics. All participants were invited via e mail.

The FRAM focus group was facilitated by a Human Factors expert (LM), and had previously been piloted with members of the research team. The facilitator introduced the methodology using a simple non-clinical scenario (parking a car at a hospital site) before commencing the full analysis. Primary data from the REFLECT study informed the FRAM alongside discussion with participants. This included interviews with 55 patients, family members and multidisciplinary staff about their experiences of post-ICU ward care, and analysis of the medical records of 300 patients who died following discharge from ICU. Further details of this approach are described in the published protocol [13] and primary data is intended for publication elsewhere. Participants were provided with summary information on mobilisation and rehabilitation from the REFLECT study. The FRAM focus group took two hours, during which sticky notes were used to map out functions and aspects. These were then transcribed and refined into the FRAM Visualiser software (Version 0.4.1, May 2016: http://functionalresonance.com/FMV/index.html) by the research team following the focus groups.

Results

Participants

Four members of staff from two different hospitals participated: a ward physiotherapist; an ICU physiotherapist; an ICU follow up nurse; and a nurse researcher with ICU and ward experience. All invited staff took part, with no drop outs. None had prior experience of using FRAM. The participants had experience of working in six different hospitals and multiple ward environments.

Functions

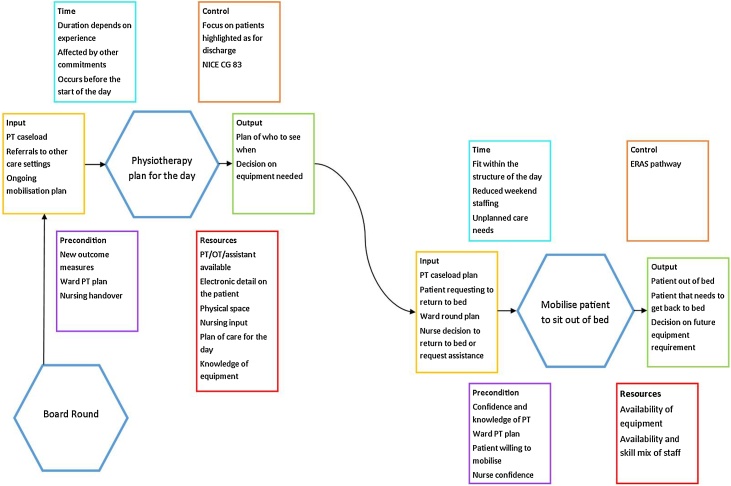

The FRAM approach identified multiple mobilisation functions, as presented in Supplementary Material, figure 1. As the aim of this work was to inform future practice change to improve mobilisation of post-ICU patients, the two key post-ICU mobilisation functions identified as influencing provision of mobilisation were focused on: creating a physiotherapy day plan and mobilising the patient from bed to chair (Fig. 1). There was little variability in the experience of undertaking mobilisation activities either between the current two sites where participants worked or in the four other employment sites. This may have been due to the small number of participants, but limited variability was also identified in primary data from the three sites included in the REFLECT study.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the key functions identified during the FRAM.

PT = Physiotherapy, OT = Occupational Therapist, NICE CG83 = The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Clinical Guideline 83, ERAS = Early Recovery After Surgery.

Function 1: creating a physiotherapy day plan

Inputs

The FRAM techniques revealed that the physiotherapy day plan is driven by organisational focus on expediting patient discharge from hospital. The day plan is required by the need to prioritise the physiotherapy case load (both clinical and non-clinical). The plan is influenced by the “board round” [16], or similar multidisciplinary meetings. These meetings highlight ward priorities for discharge for the therapy team. At this point access to therapy can appear to block the discharge process. An organisation-wide expectation is communicated through policy and practice that patients requiring physiotherapy input prior to discharge will be prioritised. These pressures direct therapy resource towards patients requiring intervention to facilitate immediate hospital discharge and away from mobilising post-ICU patients.

Other inputs included receiving a handover from the ICU therapy team that included an ongoing mobilisation plan. Despite being perceived as a core decision making function of the ward, the medical ward round was not perceived to be connected to creating a physiotherapy plan and rarely instigated mobilisation.

Outputs

The output of the physiotherapy day plan is that the physiotherapy team prioritise which patients to see, when to see them and what mobilisation equipment is required.

Preconditions

Knowledge of the patients’ plan of care for the day was the key precondition and could include patients’ suitability to participate in mobilisation and knowledge of the ICU physiotherapy assessment and/or outcome of previous mobilisation interventions. The local and national requirement for patients to have rehabilitation outcome measures updated was another precondition.

Resources

Resources identified included knowledge of the mobilisation equipment available and its location, as well as a physical space to create a plan. Knowledge of the availability of ward resources such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists and rehabilitation assistants along with bedside nursing input was seen as important for plan creation.

Controls

Within the FRAM model, NICE CG83 [6] was identified as a theoretical control. The national requirement for the post-ICU patient to have a ward rehabilitation plan encourages the creation of a physiotherapy plan but does not instigate rehabilitation activity. The analysis showed that in practice, the organisation's focus on prioritising patients for discharge from hospital overrides NICECG83 and those with ongoing, greater rehabilitation requirements. This results in mobilisation of post-ICU patients being down-prioritised to later in the day, and potentially not occurring every day.

In contrast, participants identified the presence of an Enhanced Recover After Surgery (ERAS) pathway [17] as a key control that prioritised patients who had not been to ICU but were on an ERAS pathway above the post-ICU patient with a more compelling need.

Time

The creation of a physiotherapy day plan usually occurs at the start of the day. Creating the plan takes between 10 and 30 minutes, depending on therapist experience, and is often affected by other commitments.

Function 2: mobilising the patient from bed to chair

Inputs

Mobilising a post-ICU patient from bed to chair may be instigated by patient, organisation and staff inputs (Supplementary Material, figure 1). Mobilisation may be instigated by the physiotherapy day plan or (rarely) a plan for mobilisation raised by the medical ward round. The patient may request help to get out of bed, or nurses or clinical support workers may decide to sit the patient out themselves or request physiotherapy assistance to do so if this was accessible. This was deemed less likely to occur if the patient had more complex needs which were perceived to require physiotherapy input to support, particularly if they were unable to stand and step to a chair.

Output

There are two outputs from mobilising a patient from bed to chair: the patient mobilised to a chair (that at some point needs to return to bed) and knowledge of the staff and equipment required for future mobilisation.

Preconditions

Multiple preconditions facilitating patient mobilisation were discovered. These included the requirement for the patient to be designated medically well enough, willingness to sit out of bed, requirements to have falls or tissue viability assessments prior to mobilising and ward staff needing both the confidence and knowledge to safely mobilise the patients.

Resources

Patient mobilisation was perceived to be affected by both the joint availability and skill mix of ward therapy and nursing staff. Ward therapy staff who had limited experience or knowledge of mobilisation in critical care were identified as often being intimidated by post-ICU patients and subsequently conservative in their mobility interventions. The continuity provided by the ICU follow-up/outreach service in other aspects of care was not perceived to aid continuity of mobilisation. The availability and location of mobilisation equipment was also described as having a significant impact on patient mobilisation. Problems identified with equipment included lack of storage, access, availability and familiarity. A lack of staff and/or equipment was perceived to result in a step down of the mobilisation intervention e.g. sitting a patient on the edge of the bed and returning them to bed instead of sitting out.

Controls

The controls for mobilising a patient from bed to chair did not differ from those identified for creating a physiotherapy day plan.

Time

The mobilisation activity needs to fit within the structure of the ward day, including the availability of staff to assist the patient to return to bed if required. Reductions in staffing numbers (particularly at a weekend) makes mobilisation more difficult. Mobilisation is also often interrupted by unplanned care needs.

Interdependencies

The FRAM model demonstrated multiple interdependencies mitigating against successful mobilisation. These interdependencies include: competing patients; the availability of the patient; equipment and experienced personnel; the need for documentation prior to mobilisation and the complexity of the intervention required to achieve mobilisation. The interdependencies in both functions are presented (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Mobilising patients after a period of critical illness is often challenging, with patients receiving a low number of mobility interventions and commonly experiencing a reduction in their level of mobility following discharge from ICU to the ward [9]. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to use a human factors framework to enable an in-depth exploration of the mobilisation of ICU patients after discharge to the ward. Studies aimed at increasing post-ICU mobilisation provision have not improved patient outcome as they may not have addressed the complexity of the patient cohort [11]. This study offers a detailed insight into the realities of mobilising post-ICU patients in the ward environment, identifying areas which could be changed to improve patient outcome. This analysis highlights a number of patient, individual staff and organisational factors that influence the success or failure in mobilising post-ICU patients on the ward. These include prioritisation of mobilisation within the ward workload; expertise and availability of staff; and access to appropriate equipment.

There were limitations to this study. The evaluation was limited by a lack of analysis of further sub-optimal scenarios (e.g. the care on a weekend and its impact), which and may have yielded further challenges to mobilisation of post-ICU ward patients. The stakeholder group was small, potentially limiting the experiences of the group. However, the stakeholder input was augmented by the primary data collected for the REFLECT study, which included the perspectives of a broad range of experiences from patients, family members and staff from three NHS trusts. Participants experience of undertaking post-ICU mobilisation did not vary between the sites where they currently worked, or their experience at other sites. The experiences of post-ICU mobilisation are likely to be similar across the UK. Finally, the FRAM does not explore the wider implications of instigating change based on its results, therefore further interpretation is required when using the output to instigate change. Future work will need to consider the wider impact of result in change in clinical practice.

The physiotherapy day plan is key in facilitating post-ICU mobilisation, and is influenced primarily by discharge planning, directed by the “board round” [16]. Patients who are not approaching readiness for discharge from hospital and those with significant ongoing or complex rehabilitation requirements are therefore likely to be down prioritised, and commonly planned to be seen after those patients awaiting discharge. Down prioritisation results in both a reduction in the number of mobilisation and rehabilitation interventions, and quality of the interventions. This may create a vicious cycle of patients not receiving rehabilitation, not achieving mobility milestones required for discharge, having a prolonged length of stay and subsequently putting increased pressure on expediting the discharge of patients with less complex rehabilitation requirements.

Even when post-ICU patients reach sufficient priority to be seen, complex resource requirements mitigate against mobility, especially at a weekend. This was described as particularly apparent in patients unable to stand and step to a chair, as additional staff and equipment were needed to facilitate mobilisation. As post-ICU patients are commonly complex, preconditions for mobilisation may not be met. Appropriate staff confidence and skills across the multidisciplinary team are essential in facilitating mobilisation of complex patients. Without these, the short-term safety of non-mobilisation may over-ride the benefits of mobilisation. This may mean that despite prioritisation and sufficient staff, the patient may not be designated fit to mobilise and there is insufficient expertise present to make that designation. This may be replicated by the ward nursing staff, if they perceive post-ICU patients as more unwell [18] and are therefore more likely to wait for physiotherapy staff to instigate mobility interventions. Scheduling a mobilisation intervention for post-ICU patients was identified as a challenge due to their complexity. They often require numerous multidisciplinary interventions which are difficult to plan for and may be subject to change at short notice.

A lack of staff has previously been identified as a barrier to mobilisation of post-ICU patients on the ward [19], and equipment as a barrier within ICU [20]. However, the negative impact of equipment location and availability on post-ICU mobilisation has not previously been highlighted. Patients with more complex rehabilitation requirements have the greatest need for mobilisation equipment and are therefore more likely to miss mobilisation interventions as a result of equipment unavailability. Addressing the burden of sourcing and retrieving mobilisation equipment on the ward should form part of any future intervention aimed at facilitating post-ICU mobilisation.

The requirement to adhere to ERAS [17] care pathways also exerts influence over prioritisation, however NICE CG83 [6] does not. This may be due to: the positive influence of ERAS programmes on hospital length of stay [21]; the instructional nature of the programme; and that rehabilitation requirements of patients on the programmes are significantly less complex. In addition, ERAS programmes are internationally recognised, and are in place for several different patient populations [22], [23], which may increase familiarity amongst staff. In contrast, several barriers to implementation of NICE CG83 have been identified, which include a lack of resources and prioritisation at a managerial level [19]. The failure to attract additional resource and managerial support may be in part due to the lack of demonstrable benefit on hospital length of stay. The guideline also poses a difficulty in delivery compared to an ERAS programme, as it encompasses a wide variety of patients with varying clinical presentations and rehabilitation complexity.

Conclusion

This novel human factors analysis of mobilisation of the ICU patient after discharge to the ward identified several influencing factors and demonstrated their interdependency. Organisational prioritisation of patients for discharge can result in a delay to and reduction in mobilisation of the post-ICU patient with greater needs. Patients discharged from ICU unable to stand and step to a chair are particularly susceptible to delays in mobilisation and are affected by staffing and equipment constraints. Prioritisation and co-ordination, along with improved education, skill mix, and access to equipment may facilitate mobilisation of dependent post-ICU patients with significant rehabilitation needs.

Contribution of the paper

-

•

Prioritisation of patients requiring discharge assessment over post-ICU patients with more urgent clinical rehabilitation needs compromises mobilisation.

-

•

Patients discharged from ICU who are unable to stand and step to a chair are particularly susceptible to missing mobilisation interventions.

-

•

Patients requiring equipment to mobilise are at particular risk of missing mobilisation interventions.

-

•

The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery pathway is a successful facilitator of mobilisation

Acknowledgements

The authors would like the thanks the participants of the FRAM focus group for their insightful input.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval has been obtained through the Wales Research and Ethics Committee (17/WA/0107).

Funding: This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-0215-36149) and supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Conflict of interest: Peter Watkinson co-developed the System for Electronic Notification and Documentation (SEND), for which Drayson Health has purchased a sole licence. The company has a research agreement with the University of Oxford and royalty agreements with Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust and the University of Oxford. Drayson Health may in the future pay Peter Watkinson personal fees.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2021.03.013.

Contributor Information

O.D. Gustafson, Email: owen.gustafson@ouh.nhs.uk.

S. Vollam, Email: sarah.vollam@ndcn.ox.ac.uk.

L. Morgan, Email: lauren.morgan@nds.ox.ac.uk.

P. Watkinson, Email: peter.watkinson@ndcn.ox.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Fan E., Dowdy D.W., Colantuoni E., Mendez-Tellez P.A., Sevransky J.E., Shanholtz C., et al. Physical complications in acute lung injury survivors: a 2-year longitudinal prospective study. Crit Care Med [Internet] 2014;42(4):849–859. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000040. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3959239/pdf/nihms-541689.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herridge M.S., Tansey C.M., Matté A., Tomlinson G., Diaz-Granados N., Cooper A., et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2011;364(14):1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herridge M.S., Moss M., Hough C.L., Hopkins R.O., Rice T.W., Bienvenu O.J., et al. Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med [Internet] 2016;42(5):725–738. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamdar B.B., Sepulveda K., Chong A., Lord robert K., Dinglas V.D., Mendez-tellez P., et al. Return to work and lost earnings after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study of long-term survivors. Thorax [Internet] 2018;73:125–133. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffiths J., Hatch R.A., Bishop J., Morgan K., Jenkinson C., Cuthbertson B.H., et al. An exploration of social and economic outcome and associated health-related quality of life after critical illness in general intensive care unit survivors: a 12-month follow-up study. Crit Care [Internet] 2013;17(3):R100. doi: 10.1186/cc12745. [cited 2019 Nov 18] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institue for Health and Clinical Excellence . 2009. Rehabilitation after critical illness. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/CG83 [cited 2019 Jan 14] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tipping C.J., Harrold M., Holland A., Romero L., Nisbet T., Hodgson C.L. The effects of active mobilisation and rehabilitation in ICU on mortality and function: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med [Internet] 2017;43(2):171–183. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4612-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid J.C., Unger J., Mccaskell D., Childerhose L., Zorko D.J., Kho M.E. Physical rehabilitation interventions in the intensive care unit: a scoping review of 117 studies. J Intensive Care [Internet] 2018;6(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s40560-018-0349-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins R.O., Miller R.R., Rodriguez L., Spuhler V., Thomsen G.E. Physical therapy on the wards after early physical activity and mobility in the intensive care unit. Phys Ther [Internet] 2012;92(12):1518–1523. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12146. [cited 2019 Nov 22] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connolly B., Salisbury L., O’Neill B., Geneen L.J., Douiri A., Grocott M.P.W., et al. Exercise rehabilitation following intensive care unit discharge for recovery from critical illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008632.pub2. Art. No.: CD008632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh T.S., Salisbury L.G., Merriweather J.L., Boyd J.A., Griffith D.M., Huby G., et al. Increased hospital-based physical rehabilitation and information provision after intensive care unit discharge: the RECOVER randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med [Internet] 2015;175(6):901–910. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollnagel E., FRAM: CRC Press; London: 2012. The functional resonance analysis method. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vollam S., Gustafson O., Hinton L., Morgan L., Pattison N., Thomas H., et al. Protocol for a mixed-methods exploratory investigation of care following intensive care discharge: the REFLECT study. BMJ Open [Internet] 2019;9(1):e027838. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027838. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/1/e027838 [cited 2019 Feb 5] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shorrock S. The archetypes of human work: 1. The messy reality [internet] Human Systems Blog. 2017 Available from: https://humanisticsystems.com/2017/01/13/the-archetypes-of-human-work/ [cited 2019 Jan 14] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clay-Williams R., Hounsgaard J., Hollnagel E. Where the rubber meets the road: Using FRAM to align work-as-imagined with work-as-done when implementing clinical guidelines. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1) doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0317-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Improvement N.H.S. 2017. SAFER patient flow bundle: board rounds [Internet] Available from: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/safer-patient-flow-bundle-board-rounds/ [cited 2019 May 28] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gustafsson U.O., Scott M.J., Schwenk W., Demartines N., Roulin D., Francis N., et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations. World J Surg [Internet] 2013;37(2):259–284. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox H., James J., Hunt J. The experiences of trained nurses caring for critically ill patients within a general ward setting. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2006;22(5):283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connolly B., Douiri A., Steier J., Moxham J., Denehy L., Hart N. A UK survey of rehabilitation following critical illness: implementation of NICE Clinical Guidance 83 (CG83) following hospital discharge. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parry S.M., Knight L.D., Connolly B., Baldwin C., Puthucheary Z., Morris P., et al. Factors influencing physical activity and rehabilitation in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:531–542. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4685-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vlug M.S., Bartels S.A.L., Wind J., Ubbink D.T., Hollmann M.W., Bemelman W.A. Which fast track elements predict early recovery after colon cancer surgery? Color Dis. 2012;14(8):1001–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batchelor T.J.P., Rasburn N.J., Abdelnour-Berchtold E., Brunelli A., Cerfolio R.J., Gonzalez M., et al. Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery: recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS) Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg [Internet] 2019;55(1):91–115. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezy301. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ejcts/article/55/1/91/5124324 [cited 2019 Jan 14] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Low D.E., Allum W., De Manzoni G., Ferri L., Immanuel A., Kuppusamy M., et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in esophagectomy: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations. World J Surg [Internet] 2019;43(2):299–330. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4786-4. [cited 2019 Jan 14] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.