Abstract

Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Apart from respiratory manifestations, COVID-19 can affect the nervous system due to its neurotropic features. Neurological manifestations and complications include headache, polyneuropathies, cerebrovascular accidents, seizures, encephalopathy, and demyelinating disease. We describe a case of multiple sclerosis, a demyelinating disease following COVID-19 infection, rarely reported in the literature.

A 47-year-old female presented with fatigue, blurry vision, numbness, and signs of upper motor neuron lesions that had occurred three weeks after COVID-19 infection. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed demyelinating lesions in the periventricular area of both hemispheres, suggesting a demyelinating disease. A provisional diagnosis of multiple sclerosis was made. Her condition improved after the commencement of methylprednisolone.

Keywords: demyelinating diseases, post-covid complications, multiple sclerosis, sars-cov-2, covid-19

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which typically manifests with fever, myalgia, and signs and symptoms of the respiratory system and causes substantial morbidity and mortality in severe cases such as multiorgan failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome [1-4]. The novel coronavirus is also a neurotropic virus causing complications in both the central and peripheral nervous systems, particularly during the post-recovery phase with a prevalence of 36% after a viral infection, and those complications include polyneuropathies, headache, seizures, ataxia, cerebrovascular diseases, and demyelinating diseases [5-6]. Demyelinating disorder, such as multiple sclerosis following a COVID-19 infection, has also been reported in the literature [7]. Herein, we describe a rare case of multiple sclerosis in a female following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Case presentation

A 47-year-old female with a past medical history of diabetes mellitus came to an outpatient clinic for post-COVID follow-up. She complained of severe fatigue throughout the day for the last six days, associated with intermittent tingling and numbness on the left side of the leg and arm. She had blurry vision in her left eye for the last 18 hours associated with intermittent mild pain behind the left eye exacerbated by eye movement. She had not experienced these symptoms before. She denied any history of migraines and any family history of neurological disease. She was compliant with her diabetic medication.

She was admitted to the hospital three weeks back due to a COVID-19 infection with typical signs and symptoms, including fever, dyspnea, cough, and myalgia. She was treated with remdesivir, dexamethasone, and supplemental oxygen due to fluctuation in oxygen levels. Her symptoms gradually improved, and she was discharged four days later on dexamethasone and antipyretics with isolation instructions.

On examination, the patient looked anxious, anicteric, and well-oriented in time, place, and person. She was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 110/80 mmHg, respiratory rate of 21/minute, heart rate of 92/minute, and oxygen saturation of 97%. On neurological exam, her visual acuity was 60/200 in her left eye, with no visual problem in her right eye. A relative afferent pupillary defect was noted in the left eye, and fundoscopic examination showed mild inflammation of the optic disc. Other cranial nerves were intact, with no signs of meningeal irritation. Hyperreflexia was noted in the lower limbs, predominantly on the left side, along with ipsilateral clonus. Numbness was noted in the upper limb with mild sensory loss in a glove and stocking pattern. She also had reduced incitement and a delayed thought process. Respiratory and cardiovascular examinations were non-significant.

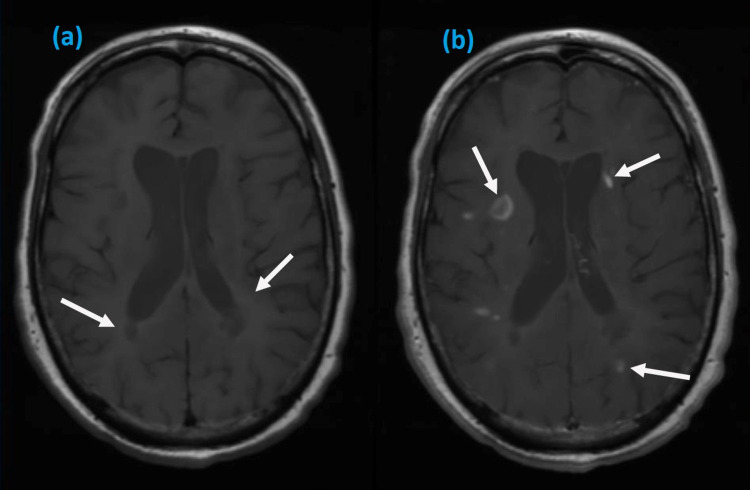

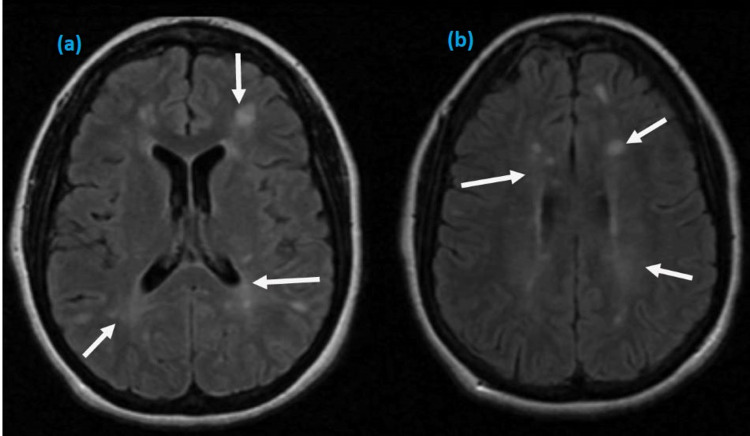

Initial serum investigations were within normal range except for mild elevation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Her repeat SARS-CoV-2 test was negative; however, serology was positive for COVID-19 immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed and revealed multiple scattered periventricular lesions with contrast enhancement in T1-weighted axial images (Figure 1) and hyperintense lesions involving periventricular areas of both hemispheres on T2-weighted images (Figure 2). MRI spine was normal. On further investigations, viral serologies for syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and human immune deficiency virus were negative. Autoimmune screening, including antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and other cytoplasmic antibodies, was non-reactive. She did not give consent for a lumbar puncture.

Figure 1. Axial T1 MRI images showing periventricular lesions of various intensities in posterior (a, b) and parietal lobe (b).

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

Figure 2. Axial T2 MRI images showing hyperintense signals in both hemispheres (a, b).

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging

Based on history, physical examination, and detailed investigations, a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis triggered by COVID-19 was made, as no other etiology was identified. She was managed with 1 g of prednisolone daily and symptomatic treatment. Her vision improved gradually, and she also reported improvement in her fatigue and other neurological symptoms. She was discharged on tapering oral dexamethasone with follow-up.

Discussion

COVID-19 mainly affects the respiratory system, and common respiratory manifestations include fever, dyspnea, cough, and sore throat. Gastrointestinal and cardiovascular complications include diarrhea, nausea, acute pancreatitis, myocardial infarction, and acute coronary syndrome [1]. Neurological complications have also been reported, and common manifestations include headache, anosmia, cerebrovascular disease, and seizures [5]. The proposed pathophysiology of multisystem involvement in COVID-19 is due to the presence of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors in multiple organ systems and having a high affinity for the SARS-CoV-2 virus [7]. Apart from other neurological manifestations, demyelinating disease, such as multiple sclerosis has not been reported widely due to COVID-19 infection. We have reported cases of multiple sclerosis after COVID-19 in Table 1.

Table 1. Multiple sclerosis due to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

MS: multiple sclerosis, ADEM: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, N/R: not reported

| Author | Age (year) | Sex | First symptom after COVID-19 infection (weeks) | Demyelinating disease | Major manifestation | Type of Demyelinating disease | Management |

| Palao et al. [8] | 29 | Female | 3 | Yes | Optic neuritis, anosmia | MS | Methylprednisolone |

| Yavari et al. [9] | 24 | Female | 4 | Yes | Diplopia, paresthesia | MS | Interferon-beta |

| Ismail et al. [10] | 36 | Male | 8 | Yes | Ataxia, vertigo | MS | Methylprednisolone |

| Moore et al. [11] | 28 | Male | 2 | Yes | Vertigo, blurry vision | MS | Methylprednisolone |

| Zanin et al. [12] | 54 | Female | N/R | Yes | Unconsciousness | MS | Dexamethasone |

| Karsidag et al. [13] | 18 | Female | 2 | Yes | Dizziness, Vertigo | MS | Methylprednisolone |

| Karsidag et al. [13] | 42 | Female | 4 | Yes | Jaw and facial pain | MS/ADEM | Methylprednisolone |

| Karsidag et al. [13] | 32 | Male | 16 | Yes | Numbness, weakness in the right leg | MS/ADEM | Methylprednisolone |

The neurotropic properties of COVID-19 are due to the direct invasion of SARS-CoV-2 through the nasopharyngeal area into the brain, the presence of ACE2 receptors in the nervous system, including glial cells, and basal ganglia and their affinity to SARS-CoV-2 resulting in the development of symptoms [14]. A severe inflammatory response against SARS-CoV-2 results in the production of inflammatory and pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines. These inflammatory mediators disrupt the blood-brain barrier and induce glial cells activation and demyelination of nerve fibers [15]. Molecular mimicry, such as the production of autoantibodies induced by cytokine storm, can also result in immune-mediated injury to nervous tissues. Microinfarction and cerebral ischemia may also result from microangiopathy induced by complement activation and cytokine response [14-15]. Several studies have also linked autoimmune diseases with many viruses, such as parainfluenza virus and coronavirus, after six to seven weeks of exposure [16].

Multiple sclerosis is a nervous system autoimmune disease with a prevalence of 0.91 million in the USA [17]. Multiple sclerosis is a demyelinating disorder affecting the brain and spinal cord with a wide range of clinical manifestations, which differ significantly from person to person and over the course of the illness depending upon the lesion location. Manifestations include visual problems, upper or lower motor neuron signs, fatigue, numbness, ataxia, body aches, and bowel, bladder, or sexual dysfunction [18]. Multiple sclerosis is diagnosed using McDonald's criteria in patients between 20 to 50 years old [19]. Other than infectious etiology, genetic and geographical etiologies may also play a role in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis [20]. Therefore, the treatment of multiple sclerosis is tailored to symptomatic management and the use of immunomodulatory disease-modifying agents [18].

Since our patient met the criteria for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis based on signs and symptoms separated in space and MRI findings. It can be assumed that the pathogenic process of multiple sclerosis had already begun before SARS-CoV-2 infection due to geographical, environmental, and genetic factors. Thus, in our case, COVID-19 might have appeared as a precipitating or triggering factor rather than being a direct consequence of infection itself. However, triggering and exacerbating autoimmune diseases in a patient with COVID-19 is increasing in the literature, and the causal association between multiple sclerosis and COVID-19 infection is warranted from future studies.

Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2, with its neurotropic characteristics, could trigger neurological auto-immunity and might appear in the place of neurological disorders. Our case highlights a possible role of SARS-CoV-2 in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis; however, our study is limited to a single case. Further evidence from future studies is warranted to establish the causality, and more cases of demyelinating diseases are required to affirm themselves after SARS-CoV-2.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Clinical Characteristics of Covid-19 in China. Zavascki AP, Falci DR. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1859. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.COVID-19 induced acute pancreatitis: a case report and literature review. Kataria S, Sharif A, Ur Rehman A, Ahmed Z, Hanan A. Cureus. 2020;12:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The association of acute kidney injury with disease severity and mortality in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Menon T, Sharma R, Kataria S, et al. Cureus. 2021;13:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawasaki disease-like features in 10 pediatric COVID-19 cases: a retrospective study. Falah NU, Hashmi S, Ahmed Z, et al. Cureus. 2020;12:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.A case of acute encephalitis in COVID-19 patient: a rare complication. Sarmast ST, Mohamed AS, Amar Z, Sarwar S, Ahmed Z. Cureus. 2021;13:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spectrum of neurological manifestations in Covid-19: a review. Garg RK. Neurol India. 2020;68:560–572. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.289000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Multiple sclerosis following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Palao M, Fernández-Díaz E, Gracia-Gil J, Romero-Sánchez CM, Díaz-Maroto I, Segura T. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;45:102377. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demyelinating changes alike to multiple sclerosis: a case report of rare manifestations of COVID-19. Yavari F, Raji S, Moradi F, Saeidi M. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2020;2020:6682251. doi: 10.1155/2020/6682251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A case report of multiple sclerosis after COVID-19 infection: causality or coincidence? Ismail II, Al-Hashel J, Alroughani R, Ahmed SF. Neuroimmunology Reports. 2021;1:100008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.A first presentation of multiple sclerosis with concurrent COVID-19 infection. Moore L, Ghannam M, Manousakis G. eNeurologicalSci. 2021;22:100299. doi: 10.1016/j.ensci.2020.100299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.SARS-CoV-2 can induce brain and spine demyelinating lesions. Zanin L, Saraceno G, Panciani PP, Renisi G, Signorini L, Migliorati K, Fontanella MM. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020;162:1491–1494. doi: 10.1007/s00701-020-04374-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demyelinating disease of the central nervous system concurrent with COVID-19. Karsidag S, Sahin S, Ates MF, Cinar N, Kendirli S. Cureus. 2021;13:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neuropathology of COVID-19 (neuro-COVID): clinicopathological update. Lou JJ, Movassaghi M, Gordy D, et al. Free Neuropathol. 2021;2:2. doi: 10.17879/freeneuropathology-2021-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathophysiological mechanisms and neurological manifestations in COVID-19. Zirpe KG, Dixit S, Kulkarni AP, et al. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24:975–980. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Respiratory viral infections and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Joo YB, Lim YH, Kim KJ, Park KS, Park YJ. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:199. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1977-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The prevalence of MS in the United States. A population-based estimate using health claims data. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. Neurology. 2019;92:0–40. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.A review of the natural history and epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: implications for resource allocation and health economic models. Richards RG, Sampson FC, Beard SM, Tappenden P. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:1–73. doi: 10.3310/hta6100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:162–173. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Dendrou CA, Fugger L, Friese MA. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:545–558. doi: 10.1038/nri3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]