Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the skeletal, dentoalveolar, and soft tissue effects of the Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device (FRD) appliance with miniplate anchorage for the treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion.

Material and Methods:

The prospective clinical study group included 17 patients (11 girls and 6 boys; mean age 12.96 ± 1.23 years) with Class II malocclusion due to mandibular retrusion and treated with skeletal anchoraged Forsus FRD. After 0.019 × 0.025-inch stainless steel archwire was inserted and cinched back in the maxillary arch, two miniplates were placed bilaterally on the mandibular symphysis. Then, the Forsus FRD EZ2 appliance was adjusted to the miniplates without leveling the mandibular arch. The changes in the leveling and skeletal anchoraged Forsus FRD phases were evaluated by means of the Paired and Student's t-tests using the cephalometric lateral films.

Results:

The success rate of the miniplates was found to be 91.5% (38 of 42 miniplates). The mandible significantly moved forward (P < .001) and caused a significant restraint in the sagittal position of the maxilla (P < .001). The overjet correction (−5.11 mm) was found to be mainly by skeletal changes (A-VRL, −1.16 mm and Pog-VRL, 2.62 mm; approximately 74%); the remaining changes were due to the dentoalveolar contributions. The maxillary and mandibular incisors were significantly retruded (P < .001).

Conclusion:

This new approach was an effective method for treating skeletal Class II malocclusion due to the mandibular retrusion via a combination of skeletal and dentoalveolar changes.

Keywords: Class II malocclusion, Forsus FRD, Skeletal anchorage

INTRODUCTION

Class II malocclusion, one of the most commonly observed problem in orthodontics, affects approximately one-third of the patients seeking orthodontic treatment.1–3 Patients with Class II malocclusions can exhibit maxillary protrusion, mandibular retrusion, or both, together with abnormal dental relationships and profile discrepancy.4 According to McNamara,5 mandibular retrusion is the most common characteristic of this malocclusion.

In patients with Class II malocclusions due to mandibular retrusion, removable and fixed functional appliances are used to stimulate the mandibular growth by forward positioning of the mandible.6–10 Various fixed functional appliances4,6,8–13 have usually been used for the treatment of those patients to eliminate the disadvantages of removable appliances; removable appliances are bulky and loose in the mouth, so they are not easy for patients to use; thus, insufficient patient cooperation occurs.10 Of the various fixed functional appliances, Forsus Fatigue Resistance Device (FRD) EZ (3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif) is one of the newest popular appliances that do not need patient cooperation and is reported to be more comfortable for patients.14

Although previously published studies6–9,13,14 proved the efficiency of fixed functional appliances, they also reported that protrusion of the mandibular incisors was a common finding. This unfavorable effect limits the skeletal effects of the fixed appliance. To overcome this problem, Aslan et al.15 used a Forsus FRD appliance combined with a miniscrew. The authors reported that the mandibular incisors protruded insignificantly (approximately 3.5°), and the overjet and molar corrections were totally dentoalveolar, confirming that the appliance was not successful for the skeletal improvements. Recently, Celikoglu et al.16 published a case report showing the treatment of a skeletal Class II malocclusion due to mandibular retrusion using a Forsus FRD appliance with miniplate anchorage inserted on the mandibular symphysis. The authors reported that this new approach was effective for correcting Class II malocclusion without mandibular incisor protrusion and with the skeletal contributions.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the skeletal, dentoalveolar, and soft tissue effects of the Forsus FRD appliance with miniplate anchorage when used for the treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion due to mandibular retrusion.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Ethical approval of this prospective clinical study was obtained from the Karadeniz Technical University, and parents of the patients signed an informed consent before inclusion in the study. The sample size was calculated based on a significance level of .05 and a power of 80% to detect a clinically meaningful difference of 2.0 (± 2.0 mm) for the effective mandibular length. The power analysis showed that 16 patients were required. To compensate for possible dropouts during the study period, more patients were included in the study.

To obtain patients that matched the criteria, two clinicians simultaneously examined the initial data of 23 patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) skeletal and dental Class II malocclusion due to mandibular retrusion (ANB >4°), (2) overjet >5.0 mm, (3) normal or low-angle growth pattern (SN-MP <38°),17 (4) permanent dentition with no extraction or hypodontia except third molars, (5) minimum crowding in the mandibular arch, (6) maturation stage just before or exactly at the peak or just after the peak stage of pubertal growth determined according to the method of Hagg and Taranger,18 (7) no clinical signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders, and (8) no previous orthodontic treatment. The 21 patients who met the aforementioned criteria were orthodontically treated in two phases.

In the first phase, preadjusted fixed appliances (Avex MX, Opal Orthodontics, South Jordan, UT) with 0.022-inch slots were attached to the maxillary teeth, and the bands were placed with a transpalatal arch to minimize the side effects on the maxillary posterior segments. After leveling and alignment, 0.019 × 0.025-inch stainless steel archwire was inserted and cinched back in the maxillary arch; the maxillary teeth were then ligatured in a figure-8 pattern to avoid lateral forces and molar tipping. In the second phase, two miniplates (Stryker, Leibinger, GmbH&Co.KG, Freiburg, Germany) were placed bilaterally at the symphysis of the mandible under local anesthesia by an experienced surgeon. The miniplates were adjusted and fixed by three miniscrews (diameter, 2 mm; length, 7 mm) made of titanium (Figure 1). Three or four weeks after the surgery, the Forsus FRD EZ2 appliance selected according to the manufacturer's instructions was adjusted to the miniplates without leveling the mandibular arch (Figure 2). The patients were observed at 4-week intervals, and if needed, the appliance was activated by crimping the stoppers onto the pushrod. The appliance was removed when Class I canine and molar relationship was achieved and the increased overjet was eliminated. Mean durations of the first phase (leveling of the maxillary arch) and the second phase (miniplate anchoraged Forsus FRD use) were both 0.60 years. The mandibular arch was not bonded during phases 1 and 2. Then, the miniplates were removed by the same surgeon under local anesthesia; the preadjusted fixed appliances were attached to the mandibular teeth by the same orthodontist, and orthodontic treatment went on.

Figure 1.

The miniplates inserted on the mandibular symphysis.

Figure 2.

Application of the skeletal anchoraged Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device appliance.

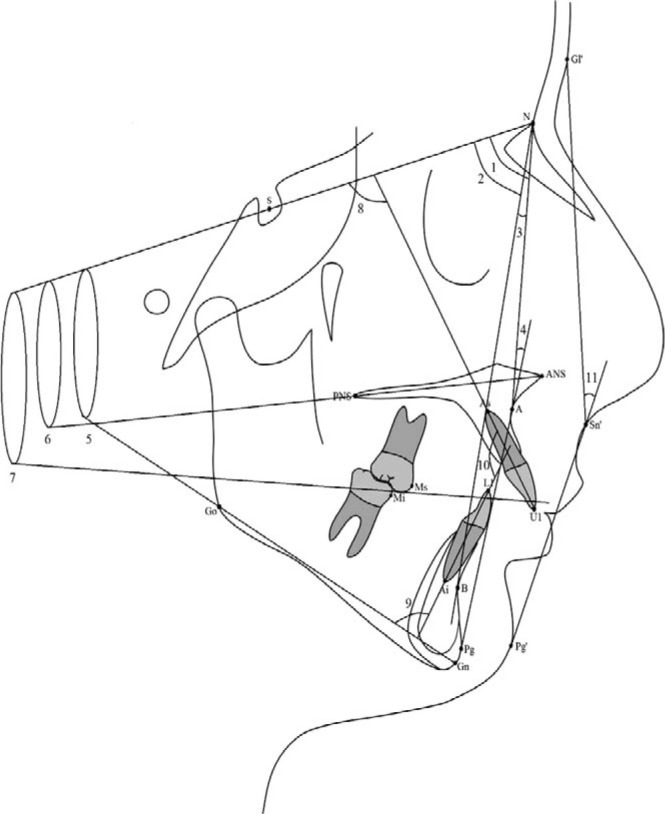

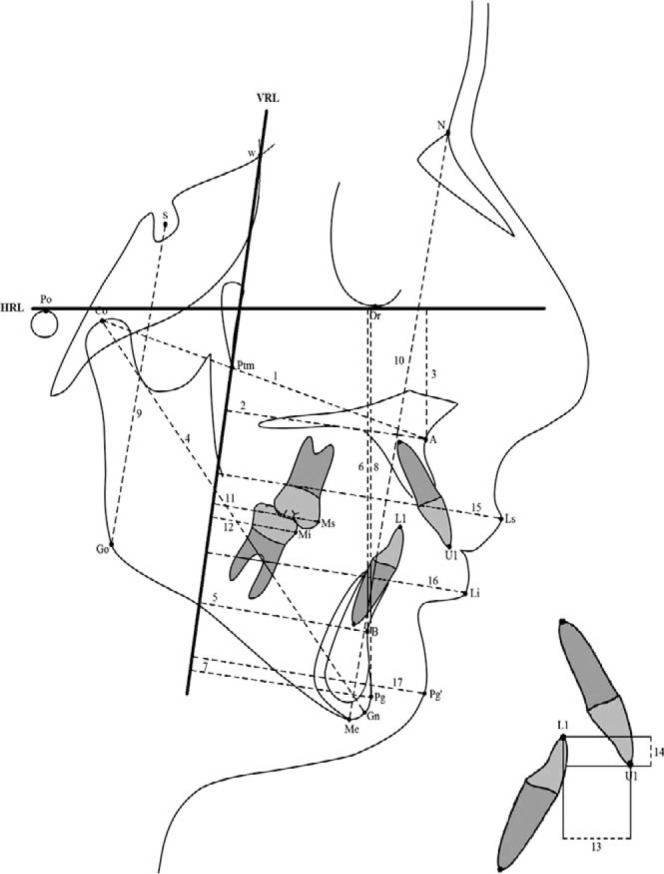

Standardized lateral cephalograms were taken by an experienced technician TU at the beginning of treatment, after the first phase of treatment, and after the second phase of the treatment using the same cephalostat (Siemens Nanodor 2, Siemens AG, Munich, Germany). The Frankfort horizontal plane was used as the horizontal reference line (HRL), and a perpendicular line passing through the ethmoid registration point and pterygomaxillary fissure inferior was used as the vertical reference line (VRL).19 After the calibration was done, all radiographs were blindly traced by one researcher with a random queue of the cephalometric films, and 17 linear and 11 angular measurements were performed to evaluate skeletal, dental and soft tissue changes in both phases of the treatment (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Angular measurements used in the study (in degrees): (1) SNA, (2) SNB, (3) ANB, (4) convexity, (5) SN-MP, (6) SN-PP, (7) SN-OP, (8) U1-SN, (9) IMPA, (10) U1-L1, and (11) soft tissue convexity.

Figure 4.

Linear measurements used in the study (in millimeters): (1) Co-A, (2) A-VRL, (3) A-HRL, (4) Co-Gn, (5) B-VRL, (6) B-HRL, (7) Pog-VRL, (8) Pog-HRL, (9) S-Go, (10) N-Me, (11) Ms-VRL, (12) Mi-VRL, (13) overjet, (14) overbite, (15) Ls-VL, (16) Li-VRL, and (17) Pog(s)-VRL.

Statistical Analyses

The Shapiro-Wilks test showed that the data were normally distributed (P > .05), and thus, the parametric tests were used. The changes observed in each phase of the treatment were evaluated using a paired t-test. Interphase comparisons were analyzed by means of the Student's t-test. Comparison of the genders in each phase was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test because of the few samples, and the data were pooled as no gender difference was present in each phase (P > .05).

Ten radiographs were selected randomly 2 weeks after the first evaluation, and all measurements were performed again by the same researcher (TU). The method error was determined using the coefficient of reliability as described by Houston,20 and the results confirmed the reliability of the measurements (the coefficients were above .80).

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package program (SPSS for Windows 98, version 10.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). The significance level was set at P < .05 for all tests.

RESULTS

Of the 21 patients, four were excluded because of the mobility of the unilateral miniplate. The success rate of the miniplates was found to be 91.5% (38 of 42 miniplates). Finally, the analyses were performed using the data of 17 patients who completed the second phase (miniplate anchoraged Forsus FRD phase) successfully. In addition, one patient had a breakage of the Forsus FRD EZ2 appliance, and the appliance was replaced on the same day.

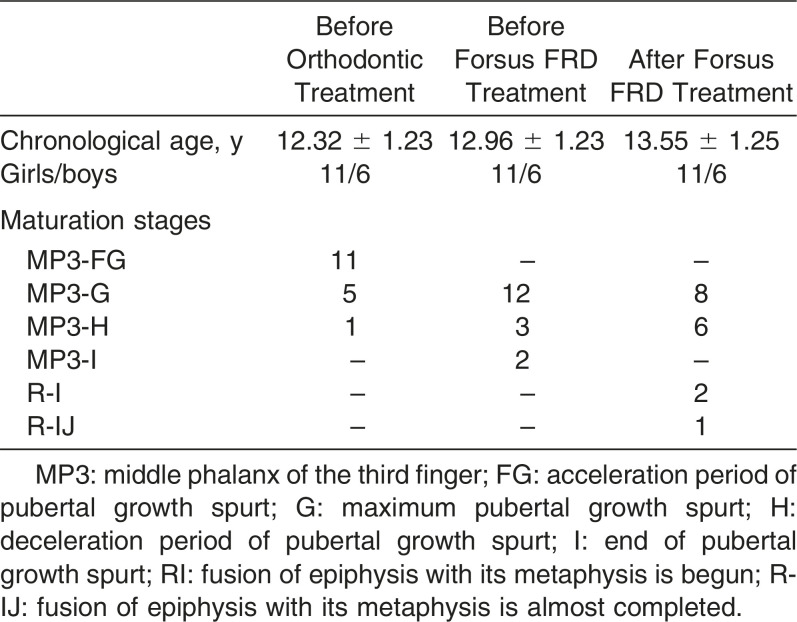

The descriptive data, including chronological age, gender distribution, and maturation stages of the patients who completed the study, is shown in Table 1. Before the skeletal anchoraged Forsus FRD application, most of the patients were at maturation stage MP3-G, showing the peak of the pubertal growth, and the mean chronological age was 12.96 ± 1.23 years.

Table 1. .

Demographic Data for Study Subjects

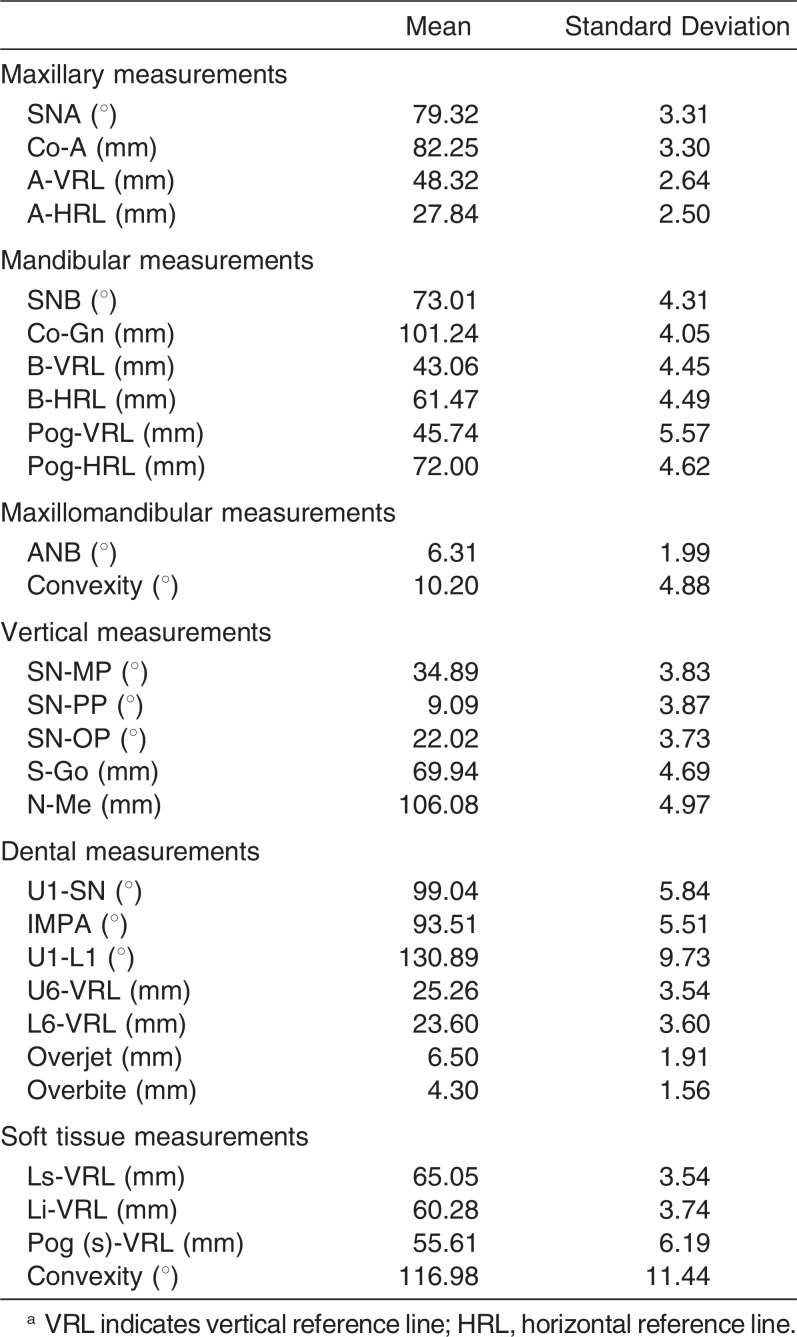

Initial cephalometric values of the patients are shown in Table 2. The patients had skeletal Class II malocclusion due to the mandibular retrusion, normal vertical growth pattern, and normal maxillary and mandibular incisor inclinations.

Table 2. .

Initial Cephalometric Values for Study Subjectsa

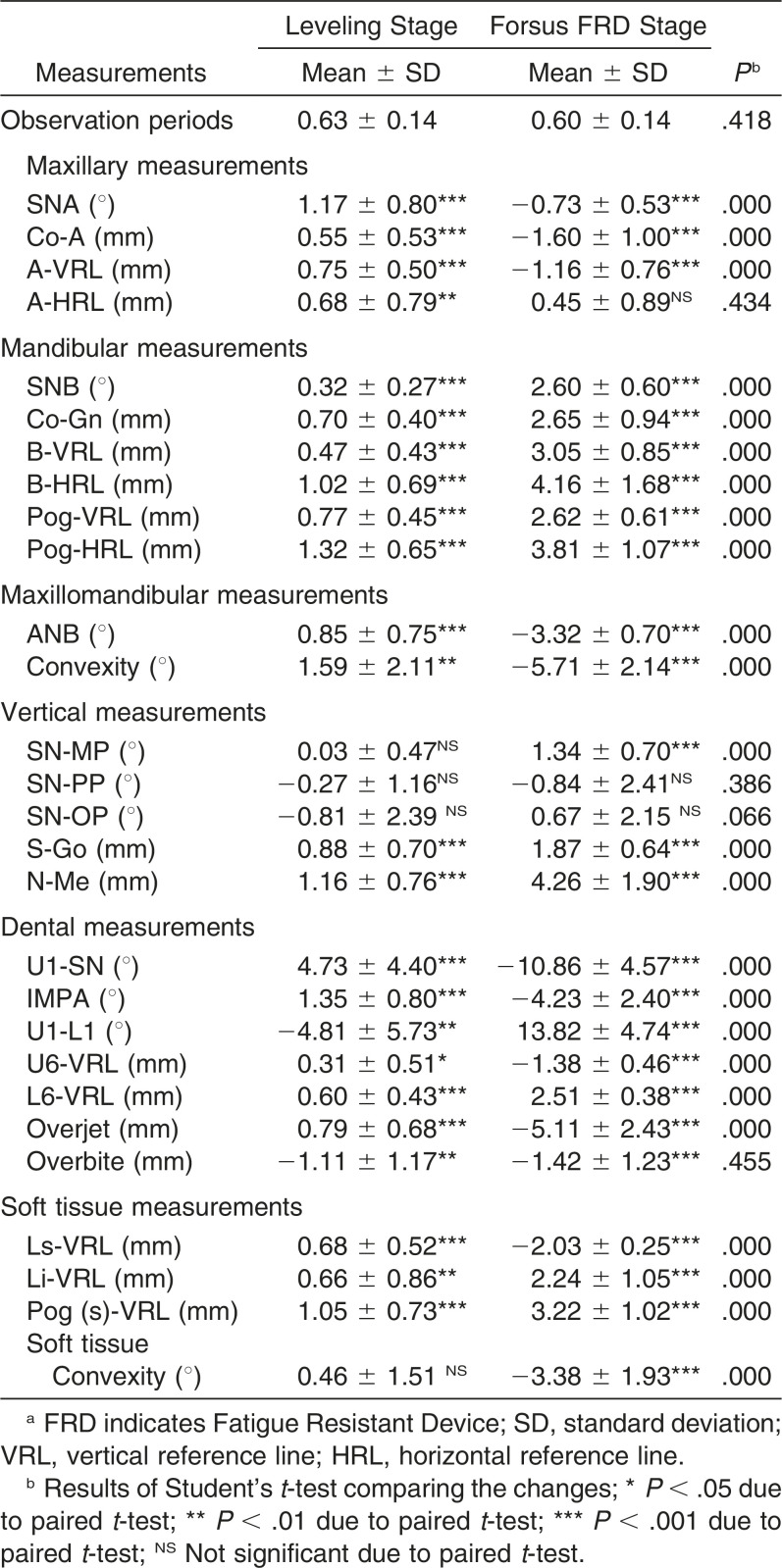

Changes occurred during the leveling and the skeletal anchoraged Forsus FRD EZ2 appliance phases; the statistical comparison of these changes are shown in Table 3. In the leveling phase, clinically slight changes were observed for all parameters except for U1-SN (4.73°) due to the growth and leveling of the maxillary arch. In the skeletal anchoraged Forsus FRD phase, maxillary measurements (SNA, −0.73 ± 0.53°; Co-A, −1.60 ± 1.00 mm; A-VRL, −1.16 ± 0.76 mm; P < .001) exhibited a statistically significant decrease except for A-HRL (0.45 ± 0.89 mm; P > .05). On the other hand, the mandible significantly moved forward (SNB, 2.60 ± 0.60°; Co-Gn, 2.65 ± 0.94 mm; B-VRL, 3.05 ± 0.85 mm; Pog-VRL, 2.62 ± 0.61 mm; P < .001). The changes in the maxilla and mandible caused a significant improvement in intermaxillary sagittal relationship (ANB, 3.32 ± 0.70°; convexity, 5.71 ± 2.14°; P < .001). In addition, significant increases were observed for SN-MP (1.34 ± 0.70°; P < .001) and anterior and posterior face height (4.26 ± 1.90 mm; 1.87 ± 0.64 mm; P < .001). The maxillary and mandibular incisors showed significant retroclination (−10.86 ± 4.57° and −4.23 ± 2.40°, respectively; P < .001). The changes in skeletal and dental parameters caused a significant decrease in overjet (−5.11 ± 2.43 mm; P < .001) and overbite (−1.42 ± 1.23 mm; P < .001) measurements. The upper lip moved backward (−2.03 ± 0.25 mm), and the lower lip (2.24 ± 1.05 mm) and soft tissue pogonion (3.22 ± 1.93 mm) moved forward (P < .001), resulting in a decrease in soft tissue convexity (−3.38 ± 1.93; P < .001). Comparisons of the changes that occurred in both phases showed statistically significant differences for almost all parameters (P < .001) except for A-HRL, SN-PP, SN-OP, and overbite measurements (P > .05).

Table 3. .

Statistical Evaluations of Changes Obtained in Leveling and Forsus FRD Stagesa

DISCUSSION

In the present study, miniplates were inserted on the mandibular symphysis for the application of Forsus FRD in order to eliminate mandibular incisor protrusion and to increase the skeletal contributions to the treatment findings. Previously, Celikoglu et al.16 showed this to be a successful option for the treatment of Class II malocclusion with mandibular retrusion. However, its effects were not extensively investigated. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the skeletal, dentoalveolar and soft tissue effects of this new treatment approach.

The patients included in the present study had skeletal Class II malocclusion due to the mandibular retrusion with normal vertical growth pattern. The maturation stages of the patients were almost MP3-FG (epiphysis as wide as metaphysis) (11 of 17 patients) before treatment and MP3-G (12 of 17 patients) before the Forsus phase. Both the leveling and Forsus phases lasted for the same duration, confirming the matching of the observation periods (P > .05).

Skeletal anchoraged Forsus caused a significant restraint in the sagittal position of the maxilla (SNA, −0.73 ± 0.53°; Co-A, −1.60 ± 1.00 mm; A-VRL, 1.16 ± 0.76 mm). This high pull headgear effect was also reported in some studies7,10,14,21 for the Forsus appliances. In contrast, some authors6,8,15,22 showed that the Forsus had no significant skeletal effects on the maxilla. The FRD protocol also induced significant increases in the mandibular parameters (SNB, 2.60 ± 0.60°; Co-Gn, 2.65 ± 0.94 mm; B-VRL, 3.05 ± 0.85 mm; Pog-VRL, 2.62 ± 0.61 mm). These changes improved the maxillomandibular relationships (ANB, −3.32 ± 0.70°; convexity, −5.71 ± 2.14°). These findings supported the previous studies showing the efficiency of fixed functional appliances, including the Herbst23 and Forsus10,21 appliances. According to Bilgic et al.,10 the mean differences between Forsus and untreated control groups were −1.7° for SNA, 0.4° for SNB, −2.1° for ANB, and 2.6 mm for Co-Gn. In the study of Cacciatore et al.,21 these differences were −1.7°, −0.2°, −1.5°, and 1.9 mm, respectively. The leveling and Forsus phases, the differences for SNA, SNB, ANB, and CoGn were −1.9°, 2.3°, −4.2°, and 2.0 mm, respectively. This shows the efficiency of the miniplate anchoraged Forsus application compared with conventional methods. On the other hand, Aslan et al.15 found that the overjet and molar corrections were totally dentoalveolar, and no skeletal effects were reported using the miniscrew anchorages Forsus FRD. The authors15 reported the insufficient resistance of the miniscrews to the forward force direction of the appliance.

Dentoalveolar changes from the present approach were distalization of maxillary molars and retrusion of the maxillary and mandibular incisors. These dentoalveolar changes, combined with skeletal contributions, caused a significant correction in the overjet (−5.11 ± 2.43 mm). Compared with previous studies,6,7,9,10,15,22 the decrease in the maxillary incisor inclination was found to be greater in the present study (−10.86 ± 4.57°). This might be due to the use of skeletal anchorage in the mandible that transmitted the force to the maxillary arch. In addition, Aslan et al.15 reported similar changes for inclination of the maxillary incisors (−8.9 ± 5.7°) with the use of miniscrew anchoraged Forsus. The overjet correction (−5.1 1 mm) was found to be mainly by skeletal changes (A-VRL, −1.16 mm; Pog-VRL, 2.62 mm; approximately 74%), while the remaining changes were due to the dentoalveolar contributions. This shows the efficiency of the present approach compared with the lower skeletal contributions reported in previous studies.6,8–10,15 The methods previously described to prevent mandibular incisor protrusion, such as using negative-torqued mandibular incisor brackets, sectional arches, and mini screws, were found to be unsuccessful, although the use of miniscrews decreased the mandibular incisor protrusion.15 In the present study, the mandibular incisors were surprisingly retruded and this finding was also noted by Celikoglu et al.16 This change might be useful in the treatment of Class II malocclusion with protruded mandibular incisors and with diastema. It is possible that the pressure of the maxillary incisors and lower lip caused this change.

The lower lip and soft tissue pogonion significantly protruded and the upper lip significantly retruded as results of skeletal and dental changes. These changes improved the facial soft tissue convexity. These finding were similar to the soft tissue findings of the previous studies.6,10

Despite the favorable findings of the present study, this new approach has some limitations, including the need for a surgical procedure to insert the miniplates on mandibular symphysis, the need for a second operation in case of mobility, and the increased cost of orthodontic treatment because of the use of miniplates and miniscrews. In the present study, the success rate of the miniplates was 91.5% (38 of 42 miniplates). In agreement with our finding, the success rates for miniplates were previously found to be quite high.24

Another limitation of the present study might be not using an untreated Class II group as a control group. However, it is not ethical to postpone the treatment of those patients as it was shown that the amount of supplementary mandibular growth appeared to be significantly larger if functional treatment was performed at the pubertal peak.22,25 Future studies with larger samples might be very useful to evaluate the stability of these favorable results and to compare the findings with a well-matched conventional Forsus FRD group to prove the efficiency of this new approach.

CONCLUSIONS

Within the limitations of the present study

Skeletal anchoraged Forsus FRD EZ2 using miniplates inserted on mandibular symphysis was found to be an effective method for the treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion due to mandibular retrusion via a combination of skeletal and dentoalveolar changes.

The overjet correction (−5.11 mm) was found to be mainly by skeletal changes (A-VRL, −1.16 mm; Pog-VRL, 2.62 mm; approximately 74%), the remaining changes were due to the dentoalveolar contributions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was part of work that was supported by a research grant from Karadeniz Technical University, Scientific Research Projects Unit, and Project number 9705.

REFERENCES

- 1.Proffit WR, Fields HW, Jr, Moray LJ. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: estimates from the NHANES III survey. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998;13:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelgor IE, Karaman AI, Ercan E. Prevalence of malocclusion among adolescents in central Anatolia. Eur J Dent. 2007;1:125–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celikoglu M, Akpinar S, Yavuz I. The pattern of malocclusion in a sample of orthodontic patients from Turkey. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:e791–e796. doi: 10.4317/medoral.15.e791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arici S, Akan H, Yakubov K, Arici N. Effects of fixed functional appliance treatment on the temporomandibular joint. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:809–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNamara JA., Jr Components of Class II malocclusion in children 8–10 years of age. Angle Orthod. 1981;51:177–202. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1981)051<0177:COCIMI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karacay S, Akin E, Olmez H, Gurton AU, Sagdic D. Forsus Nitinol Flat Spring and Jasper Jumper corrections of Class II division 1 malocclusions. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:666–672. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0666:FNFSAJ]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones G, Buschang PH, Kim KB, Oliver DR. Class II non-extraction patients treated with the Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device versus intermaxillary elastics. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:332–338. doi: 10.2319/030607-115.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunay EA, Arun T, Nalbantgil D. Evaluation of the immediate dentofacial changes in late adolescent patients treated with the Forsus FRD. Eur J Dent. 2011;5:423–432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oztoprak MO, Nalbantgil D, Uyanlar A, Arun T. A cephalometric comparative study of Class II correction with Sabbagh Universal Spring (SUS(2)) and Forsus FRD appliances. Eur J Dent. 2012;6:302–310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilgic F, Basaran G, Hamamci O. Comparison of Forsus FRD EZ and Andresen activator in the treatment of Class II, Division 1 malocclusions. Clin Oral Investig. 2014 In Press doi: 10.1007/s00784-014-1237-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pancherz H. The mechanism of Class II correction in Herbst appliance treatment. A cephalometric investigation. Am J Orthod. 1982;82:104–113. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90489-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siara-Olds NJ, Pangrazio-Kulbersh V, Berger J, Bayirli B. Long-term dentoskeletal changes with the Bionator, Herbst, Twin Block, and MARA functional appliances. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:18–29. doi: 10.2319/020109-11.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kucukkeles N, Ilhan I, Orgun IA. Treatment efficiency in skeletal Class II patients treated with the Jasper Jumper. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:449–456. doi: 10.2319/0003-3219(2007)077[0449:TEISCI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franchi L, Alvetro L, Giuntini V, et al. Effectiveness of comprehensive fixed appliance treatment used with the Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device in Class II patients. Angle Orthod. 2011;81:678–683. doi: 10.2319/102710-629.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aslan BI, Kucukkaraca E, Turkoz C, Dincer M. Treatment effects of the Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device used with miniscrew anchorage. Angle Orthod. 2014;84:76–87. doi: 10.2319/032613-240.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Celikoglu M, Unal T, Bayram M, Candirli C. Treatment of a skeletal Class II malocclusion using fixed functional appliance with miniplate anchorage. Eur J Dent. 2014;8:276–280. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.130637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamak H, Celikoglu M. Facial soft tissue thickness among skeletal malocclusions: is there a difference? Korean J Orthod. 2012;42:23–31. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2012.42.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagg U, Taranger J. Pubertal growth and maturity pattern in early and late maturers—a prospective longitudinal-study of Swedish urban children. Swedish Dent J. 1992;16:199–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celikoglu M, Oktay H. Effects of maxillary protraction for early correction of Class III malocclusion. Eur J Orthod. 2014;36:86–92. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjt006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houston WJB. The analysis of errors in orthodontic measurements. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1983;83:382–390. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(83)90322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cacciatore G, Ghislanzoni LT, Alvetro L, Giuntini V, Franchi L. Treatment and posttreatment effects induced by the Forsus appliance: a controlled clinical study. Angle Orthod. 2014 doi: 10.2319/112613-867.1. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aras A, Ada E, Saracoglu H, Gezer NS, Aras I. Comparison of treatments with the Forsus fatigue resistant device in relation to skeletal maturity: a cephalometric and magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:616–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pancherz H, Anehus-Pancherz M. The headgear effect of the Herbst appliance: a cephalometric long-term study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993;103:510–520. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(93)70090-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornelis MA, Scheffler NR, Mahy P, et al. Modified miniplates for temporary skeletal anchorage in orthodontics: placement and removal surgeries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1439–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, De Toffol L, McNamara JAJ. Mandibular changes produced by functional appliances in Class II malocclusion: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(5):e1–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]