Abstract

Purpose

Disaster management agencies are mandated to reduce risk for the populations that they serve. Yet, inequities in how they function may result in their activities creating disaster risk, particularly for already vulnerable and marginalized populations. In this article, how disaster management agencies create disaster risk for vulnerable and marginalized groups is examined, seeking to show the ways existing policies affect communities, and provide recommendations on policy and future research.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors undertook a systematic review of the US disaster management agency, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), examining its programs through a lens of equity to understand how they shape disaster risk.

Findings

Despite a growing commitment to equity within FEMA, procedural, distributive, and contextual inequities result in interventions that perpetuate and amplify disaster risk for vulnerable and marginalized populations. Some of these inequities could be remediated by shifting toward a more bottom-up approach to disaster management, such as community-based disaster risk reduction approaches.

Practical implications

Disaster management agencies and other organizations can use the results of this study to better understand how to devise interventions in ways that limit risk creation for vulnerable populations, including through community-based approaches.

Originality/value

This study is the first to examine disaster risk creation from an organizational perspective, and the first to focus explicitly on how disaster management agencies can shape risk creation. This helps understand the linkages between disaster risk creation, equity and organizations.

Keywords: Disaster risk creation, Disasters and organizations, Federal emergency management agency, Equity, Community-based disaster risk reduction, Disaster management agencies, Cascading hazards

1. Introduction

The US response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic provides a disturbing illustration of how marginalized populations bear the brunt of disaster. At the time of this writing, the pandemic has killed more than 620,000 people across the country. Many more have lost their jobs, are facing housing and food insecurity, or do not know how they will pay the bills. And the pandemic is not the “great equalizer”. Mortality rates for American Indian and Alaska Natives are 2.6x higher than for White non-Hispanics; mortality rates for both Blacks and Hispanics are 2.8x as high (CDC, 2020). Women are more likely than men to face COVID-related unemployment, with Hispanic and Black women more likely than White women (Gezici and Ozay, 2020). These impacts can in turn exacerbate other problems, such as intimate partner violence (Buttell et al., 2021) and childhood wellbeing, including things related to academic progress, peer relations and behavioral functioning (Prime et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic appears to be a case study of how organizational failures contribute to disaster. Organizational decisions such as those to put the federal government in a “back up” role (Altman, 2020), failures to communicate using population-specific channels (Clark-Ginsberg and Petrun Sayers, 2020), and uncoordinated crisis plans and management (Mirvis, 2020) have all been identified as contributing to the rapid spread of the virus and its devastating impact. Underlying these issues are long-term decisions that constrain organizational effectiveness, such as systematic underinvestment in the emergency response architecture of public health agencies (Maani and Galea, 2020), especially in minority health (Xu and Basu, 2020), and implicit bias in health-care organizations (Tai et al., 2020).

These organizational failings are examples of disaster risk creation (DRC). DRC refers to actions that “increase, or fail to decrease vulnerability” or that “actively or inertially stymie or constrain [disaster risk reduction] efforts” (Lewis and Kelman, 2012). Exacerbating hazards, increasing exposure, deepening vulnerability and reducing coping capacity are all ways that disaster risk is created (Peters, 2021), but the specific pathways for those acts of creation are varied and complex. Lewis and Kelman (2012), for instance, highlight seven mechanisms: environmental degradation; discrimination; displacement; self-seeking public expenditure; denial of access to resources; corruption and siphoning of public money. Others focus on cases. Peters (2021) focuses on the links between disasters and conflict and Wisner and Lavell (2017) on large-scale megaprojects. What unifies this work is an understanding of risk as socially constructed. As opposed to being acts of God, nature or technology outside of human control, disasters are outcomes of ongoing social and political processes that favor some at the expense of others, structuring vulnerability and disaster exposure as an outcome (Wisner et al., 2004; Oliver-Smith et al., 2017).

In this article, we look to the organizational roots of DRC, focusing on how one specific type of organization that typically has great power to shape risk, disaster management agencies, creates risk. Our rationale for this focus is two-fold. First, how organizations create disaster risk is an undercurrent of DRC research, but not an explicit area of focus. By focusing on disaster management agencies, we aim to make the connections between DRC and organizations explicit. Second, as the official government agencies with mandates focused on mitigating and responding to disaster, disaster management agencies play a crucial role in hazard prevention and vulnerability reduction, and response and recovery are therefore central to DRC. Examining these organizations is therefore designed to provide practical value to reducing disaster risk by preventing or mitigating DRC.

To do so, we conduct a systematic review of how the United States’ federal agency is responsible for disaster management, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), engages in disaster management. We use a lens of equity to help understand how FEMA activities shape DRC. Equity underlies DRC, as inequities leave those with less access more at risk: many, including Rumbach and N,emeth (2018) and others (Wisner and Lavell, 2017; Lewis and Kelman, 2012) frame DRC from an equity perspective to argue that the creation of risk is a product of inequity. FEMA has ongoing commitment to improving equity, as evidenced by its Office of Equal Rights, which focuses on a discrimination-free workplace and equal access to services (FEMA, 2021a), and its Resilient Nation Partnership Network, which recognizes that all communities have a stake in a “more equitable and resilient nation” (FEMA, 2021b). Yet it faces implementation challenges in achieving equity (Jerolleman, 2019). We therefore focus on FEMA and DRC not to criticize FEMA’s actions or argue that its work does not reduce risk, but instead support the organization achieve its goals and to better understand the organizational dimensions of DRC.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: First, we continue with this literature review to describe equity and the ways in which it intersects with disasters and DRC, outlining both the dimensions of equity and how failure within organizations can create risk. We next present the results of our review and the evidence for how FEMA’s existing programs shape equity before describing our methods. We conclude with policy recommendations for FEMA and areas of future research.

2. Organizations, disaster risk creation and equity

Research on DRC is relatively limited, with much of it focused on hazard or geographies as unit of analysis, not organizations. For instance, Rumbach and N,emeth (2018) describe risk creation in the Darjeeling Himalayas; Covarrubias and Raju (2020) in extractive regimes in Latin America; Sandoval and Sarmiento (2020) in urban settlements throughout the Western Hemisphere; and Alc,antara-Ayala et al. (2021) in the context of COVID-19. Underlying these cases, however, are organizations and organizational decisions at work. For instance, Rumbach and N,emeth (2018) identify the local government as structuring practices in ways that contribute to risk in the Himalayas. Wisner and Lavell (2017) describe how government and private-sector organizational activities lead to risk creation during megaprojects. And Peters (2021) documents how a “dysfunctional government” can create disaster risk in conflict settings.

A stream of work on how organizational choices contribute to risk has been performed by organizational sociologists, who have documented how specific hazards emerge from organizational decisions. Diane Vaughn’s work on organizational deviance and the dark side of organizations (Vaughan, 1996, 1999); Eden (2004) and Sagan (1995) writing on nuclear related risk and work by other sociologists on how organizations can function reliably under extreme conditions (Weick et al., 1999; La Porte, 1996; Roberts, 1990), or not (Perrow, 1984), are all examples. This work shows that dysfunctions within organizations can result in hazards being created, ignored and magnified which, when realized, can affect organizations and the broader public. It also shows that these organizations do not exist in an institutional vacuum, but are instead structured by broader social processes that can encourage certain forms of risk-taking behavior with potential societal-level consequences (Perrow, 2015).

Within this context, we see in this DRC an example of what Freudenburg (1993) described as recreancy: “an effectively neutral reference to behaviors of persons and/or institutions that hold positions of trust, agency, responsibility, or fiduciary or other forms of broadly expected obligations to the collectivity, but that behave in a manner that fails to fulfill the obligations or merit the trust.” As further study and application of Freudenberg’s concept of recreancy shows, organizational behavior, far more than just leading to the perception of risk, represents the creation of risk and even harm. The inequity of that risk creation, as Tierney (2012) shows, can be seen in the examination of the “White male effect,” in which White men perceive certain risks as less serious than others because of their trust in institutional actors stemming from their beneficial relationships with those institutions.

Work by organizational sociologists tends to be focused on technological hazard creation within complex organizational structures; the construction of social vulnerability and natural hazards, including ties to equity and inequity, are not areas of focus. Equity has many meanings, but in this article, we define it as fair and equal treatment, and freedom from bias or favoritism, for all individuals and groups (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2014). It is multifaceted, often conceptualized as containing three dimensions: (1) distributive equity, or equity in outcomes – how benefits and costs are distributed across or between different groups; (2) procedural equity, or representation in decision-making processes; and (3) contextual equity, or the enabling conditions that determine people’s ability to both participate in decision-making processes and gain benefits (McDermott et al., 2013).

Distributive, procedural and contextual inequities shape how organizations create and manage risk, including vulnerability and hazards. Procedural inequities can be seen in decision-making processes obfuscated by byzantine “expert”-driven forms of technocratic risk assessment and planning, undertaken behind closed doors and away from the public (Hewitt, 1983a), or more open processes where certain community voices are marginalized in favor of dominant groups (Kelman et al., 2012; Hewitt, 1983b). Likewise, emergency management agencies can reflect dominant cultures, resulting in cultural “blind spots” or biases that lead to activities that favor some over others (Hewitt, 2012).

A variety examples of organizational activities provide illustrations of how distributive inequities manifest risk for vulnerable populations. Large infrastructure projects – like constructing dams or highway systems – frequently displace vulnerable populations and disrupt the community structures that they rely on (Wisner and Lavell, 2017). Historic redlining of Black populations by city governments in what are often disaster-prone locations increases disaster exposure (Rivera and Miller, 2007). Vulnerability is constructed as large corporations pursue economic development, such as in the Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, where Grand Caillou/Dulac, and Pointe-au-Chien Indian tribes are leaving their homes as their land disappears, due, in part, to rising sea levels but mainly because of extractive practices of the Gulf’s petrochemical industry (Maldonado, 2017).

Underlying this are deep-seated political and social inequities that allow one group to create risk and allocate it to others (Lewis and Kelman, 2012; Wisner et al., 2004). In the Philippines, for instance, poorer slum dwellers are relocated, abandoned and otherwise incur more risk because of a strategy aimed at reducing risk for the city’s elite (Alvarez and Cardenas, 2019). Marginalized and vulnerable populations tend to have less access to disaster management resources and thus are more vulnerable and less able to cope when disaster strikes (Collins and Jimenez, 2016; Collins, 2009; Gaillard, 2009).

3. Research methods

We conducted a systematic review to understand the relationship between these three dimensions of equity and the creation of disaster risk within FEMA. We chose FEMA as a case study given its centrality in the disaster management architecture within the States. Established in 1979, FEMA’s current mission is “[t]o help people before, during, and after disasters”. Like the disaster management agencies of other countries, FEMA is key to disaster management in the USA, offering assistance (often to, or through, states) to reduce risk and respond to crisis, including what is often crucial support in response to disasters that are beyond the ability of state, territorial and local governments to handle on their own.

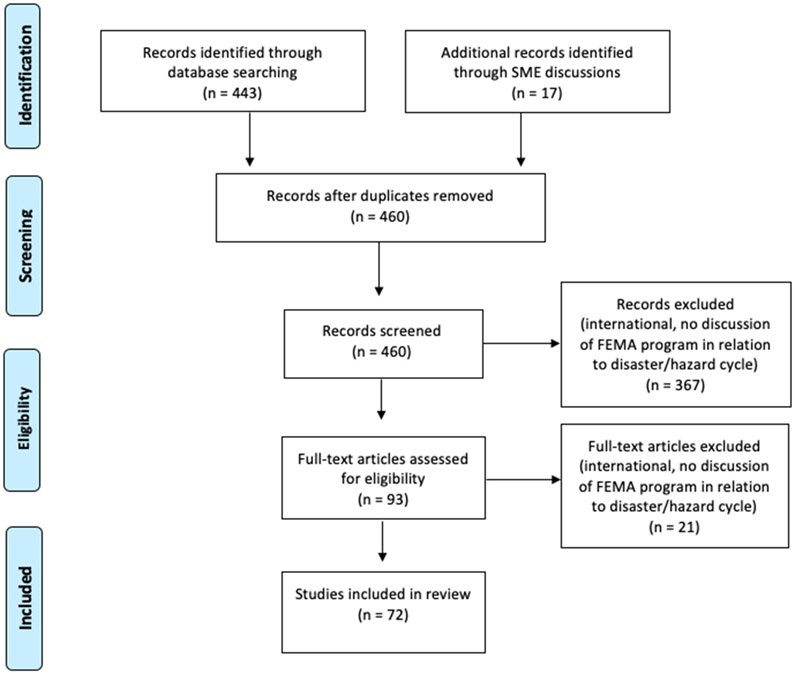

Systematic reviews are useful for synthesizing knowledge from past scientific publications. We followed the widely used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for a systematic review, which is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting a scientific review of past studies (PRISMA, 2020). PRISMA outlines a systematic protocol which describes the rationale, hypothesis and planned methods of the review carried out by the authors, which prevents arbitrary decision-making or selection bias when reviewing the literature (Shamseer et al., 2015). Using these methods, we carried out keyword searches in the Web of Science databases, using the following search term combinations: “FEMA AND mitigation”; “FEMA AND preparedness”; “FEMA AND emergency response”; “FEMA AND recovery”; “FEMA AND risk assessment”; “FEMA AND hazard cycle”; “FEMA AND community resilience”; “FEMA AND community-based disaster risk reduction”; “FEMA AND community-based disaster risk management”; and “FEMA AND disaster response”. We had a 1980 start date and a publication cut-off date of July 2020. Papers were included if they were written in English, were on the topic of FEMA program or activity, had a discussion of findings, and had a disaster or hazard focus (e.g. the occurrence or potential occurrence of a natural catastrophe, technological accident, or human-caused event that resulted in severe property damage, deaths, and/or multiple injuries). We screened publications by reading the title, abstract or summary to remove duplicates, non-English reports, reports based outside of the USA, or papers that did not discuss FEMA programs or activity in relation to disaster or hazard topics.

Potentially relevant publications were read in full, with findings synthesized by their relevance to equity. To operationalize the concept of equity, we broke equity into its procedural, contextual and distributive dimensions, synthesizing articles based on those dimensions. For procedural equity, we included papers whose results described decision- making processes or other forms of engagement with FEMA; distributive equity included papers touching on variation in access to FEMA services and supports within its programs, while contextual equity included issues of how FEMA interventions interacted with the broader environment and vice versa.

4. Results: FEMA and disaster risk creation

Figure 1 shows the results of our review process. The figure shows we found 72 publications focused on FEMA and equity accepted in this review. Only a limited number of these studies focus directly on equity, but many touched on equity indirectly, focusing on how FEMA programs were accessed by different populations and the resulting outcome. These studies covered a spectrum of hazards (most on hurricanes, 30 of 72, 42%; or floods, 24 of 72, 33%), and programs implemented across the hazard cycle (30 of 72, 42%, on mitigation; the rest on response or recovery).

Figure 1.

Results of PRISMA Analysis

4.1. Procedural equity

Studies described procedural inequities in FEMA decision-making processes within its programs, including when assessing and prioritizing risks to mitigate or identifying response and recovery priorities. Many emphasized that if steps are not taken to engage different populations at the design stage to understand their needs and capacities, community voices can be marginalized. For example, disaster information is often broadcasted only, or first, in English, creating risk for non-English speakers who consistently have difficulty accessing FEMA resources (M,endez et al., 2020). Laska et al. (2018) similarly note how FEMA, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, let stand a contractor’s decision to limit outreach to African American residents who had left New Orleans after the Hurricane and were not yet able to return, a decision marginalizing voices of dislocated survivors. They state, “The exacerbation of trauma through the engagement process leads to further disengagement and a reduction of agency” (Laska et al., 2018).

Other studies document extreme difficulties in engaging with FEMA systems due to bureaucratic infrastructure and processes. Examining the recovery from 2018 Hurricane Florence, Reinke and Eldridge (2020) describe “[insular] decision making, the absence of effective regulation and emergency planning, the lack of transparency, and bureaucratic rituals, routines, and accounting that inadequately address pain and suffering,” a process that isolated FEMA from those on the ground it aimed to help. Similar findings were documented during Superstorm Sandy, where bureaucratic processes made receiving relief difficult for thousands of homeowners (Pareja, 2019; Columbia Broadcasting System, 2015), as well as following Hurricane Katrina, where the agency’s “‘unclear and slow-moving’ rental assistance review process specifically left those in low economic standing and in extended or shared households waiting in precarious living situations, leading to socio-temporal marginalization” (Reid, 2013). The psychological impact of making someone wait indeterminately for resources necessary for recovery included “stress, worry, instability and loss of ability to make long-term plans” (Reid, 2013).

4.2. Distributive equity

Variations in access to FEMA services were documented by socioeconomic status, age, race, ethnicity and culture. Many studies identified household-level disparities by race in securing post-disaster resources, with Black households much less likely to receive assistance than Whites. Examples include Hurricane Katrina (Allen, 2007) and more recently following Hurricane Harvey (Dupuy, 2017). For instance, after Hurricane Harvey, White applicants had their applications for disaster assistance from FEMA approved at a rate more than double that of Black applicants (34% versus 13%, respectively) (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017). Language and citizenship status were also identified as shaping access (M,endez et al., 2020). Focusing on wildfires in California, M,endez et al. (2020) describes undocumented Hispanic farmworkers as “invisible victims of disaster”, noting “One of the largest gaps in safeguarding communities from disasters is the federal exclusion of undocumented people from receiving aid … despite being on the front lines of disaster, explicit exclusion from recovery and relief efforts leaves undocumented immigrants without a safety net in California’s nearly year-round wildfire season” (M,endez et al., 2020).

Class issues were also apparent, as evidenced by programs designed to support property owners. Laska et al. (2018) explains that FEMA’s recovery framework centers on (typically wealthier) homeowners while routinely leaving out (typically lower-income) renters. Yet, in the case of Hurricane Maria, Ma and Smith (2020) find renters, many of whom were lower-income, suffered substantially more damage than homeowners: “Even though renters constituted less than 8% of the primary residents experiencing structural damage, nearly two-thirds (66%) of the 8,802 homes suffering major damage were renter-occupied” (Ma and Smith, 2020). Logan (2006) similarly found that neighborhoods in New Orleans with higher percentages of renters tended to suffer higher rates of home damage following Hurricane Katrina (Logan, 2006).

Variation in access to FEMA services by geography was also documented. Isolated rural communities had a more difficult time accessing resources (Oppizzi and Speraw, 2016). Geography and race/ethnicity could overlap – Rodrıguez-Dıaz (2018) and Garcia-Lopez (2018) argue that both colonialism and geographic isolation contributed to problems with the Puerto Rico response. Similarly, Native American and tribal groups were also found to have a harder time accessing resources partly because of cultural and regulatory/jurisdictional difficulties in navigating their tribal status (Lawrence et al., 2016). Individuals having recently migrated to a site at the time of disaster, or migrated from that site following a crisis, also had a much harder time accessing support (Mendez et al., 2020).

Such differences in access to FEMA resources appear consistent over time. For instance, in their article on response to Hurricane Andrew, which occurred in 1995, Cherry and Cherry (1997) described a disregard for certain marginalized populations and for lower-socioeconomic categories such as renters; over 30 years later, a series of studies on more recent disasters has arrived at similar conclusions (Koch et al., 2017; Ma and Smith, 2020; Domingue and Emrich, 2019).

4.3. Contextual equity

Studies on contextual equity focused less on how FEMA programs shape contextual equity itself as an organization and more on how issues of contextual equity shape disaster writ large. For instance, while FEMA was criticized for problems in its response to Hurricane Katrina, the significant impacts on New Orleans’ Black residents were partly outcomes of long-term historical practices like redlining that left the city’s Black communities in precarious positions, exposed them to hazards, and shaped feelings of mistrust (Horowitz, 2020). Likewise, the impacts of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico were amplified by factors such as systematic underinvestment in critical infrastructure, partly predicated on neocolonial governance attitudes and structures (Moulton and Machado, 2019).

Contextual equity also concerns the resources, affluence and wealth a community possesses or lacks prior to a disaster, which can affect a community’s access to post-disaster assistance and its broader ability to manage risk. For example, marginalized communities are more likely to face delays in accessing the right FEMA disaster assistance resources, which can delay recovery. Also prevalent is the right type of resources: FEMA trailers provided to Katrina survivors were not designed for large communal family gatherings common to the New Orleanian Black families (Brown, 2015).

4.4. How these inequitable conditions create disaster risk

Distributive, contextual and procedural inequity results in FEMA programs failing to reduce – and sometimes creating – disaster risk. Hurricane Katrina provides an example here, where Hurricane survivors faced risk from living in trailers that FEMA provided: both cancer from trailers that contained formaldehyde and other toxic chemicals (Verderber, 2008), and intra- family stress and poor mental health from their inappropriate design (Browne, 2015; Verderber, 2008). A similar story can be told for Puerto Ricans who left for the US mainland after Hurricane Maria – those that FEMA housed in hotels and other temporary locations reported experiencing poor mental health and feelings of stress because of their housing precarity (Scaramutti et al., 2019; Jerolleman, 2019) – and for families attempting to navigate FEMA systems, who describe experiencing challenges and stress (Lucus, 2006; Sakauye et al., 2009).

In turn, these impacts can have a cascade of knock-on effects. One is breakdowns in family and community institutions, as families, friends and neighbors turn on each other, grow distant, or in other ways turn inwards in attempts to survive (Chandra et al., 2018). Another is impoverishment for households and communities unable to access resources or exposed to risk-creating processes. Rates of insolvency were higher and homeownership lower among the disproportionately Black residents of New Orleans inundated by Hurricane Katrina and the levee failures (Bleemer and van der Klaauw, 2019). Ten years after the Hurricane, the city’s racial demographics had shifted toward White families as many Black families still continue to recover and return to the city (Adamantidis et al., 2015). Finally are the secondary and tertiary cascading health impacts. Delayed delivery of resources to Puerto Rico following 2017 Hurricane Maria, which resulted in a secondary disaster many orders of magnitude greater than the initial disaster – estimated thousands of deaths compared to 56 initial deaths (Kishore et al., 2018).

5. Discussion

Our case study of FEMA shows the significant role that disaster management agencies may have in shaping DRC. Far from being pure provisors of disaster management support and resources, inequitable programs can result in the exacerbation of hazard and vulnerability, marginalization and reduced capacity, and ultimately creation of disaster risk.

The DRC that we document around FEMA actions and policy appears similar to the creation of risk found in other organizations, the product of social norms, bureaucratic processes and other “organizational deviances” (Vaughan, 1996) that let hazards manifest and propagate within organizations seemingly unchecked. For instance, in her examination of the 1986 Challenger launch disaster the sociologist Vaughan (1996) found an organization that had pushed safety to the side, valuing expediency and deadlines, a narrative similar to Hurricane Katrina, where politics and organizational biases shaped how the emergency and its aftermath were managed (Cooper and Block, 2007). And similar to the organizational deviances documented elsewhere, broader systemic factors appear to contribute to the prevalence of such challenges within FEMA – in this case a seeming acceptance of what is typically described as hazard paradigm, a top-down approach to decision-making led by bureaucrats and experts that does not take into account capacity, knowledge and desires of local populations (Hewitt, 1983a).

What we document in FEMA, however, also differs from the broader research on how organizations shape risk found in the sociology of organizations. What we see is that, rather than simply a hazard being realized, magnified and spread as a disaster, actions within FEMA are deeply entangled with issues of vulnerability and capacity. FEMA’s actions apprear to be in part the result of the powerlessness of certain populations to influence how FEMA is structured and the programs it implements. Inequitable impacts contribute to both the formation of new hazards and the exacerbation of underlying vulnerability. In other words, like the growing body of cascading research that places vulnerability at the heart of disaster (Pescaroli and Alexander, 2015; Clark-Ginsberg et al., 2018), we find here that vulnerability is central to risk creation within organizations.

Given these issues are partly a product of an organization rooted in a top-down hazard perspective that limits voices of vulnerable populations, community-based approaches might be fruitfully employed to reduce disaster risk creation within FEMA and other disaster management agencies. “Community-based approaches” refer to a broad family of techniques– including community resilience (Patel et al., 2017; Norris et al., 2008; Chandra et al., 2011) and community-based disaster risk reduction (Maskrey, 2011; Shaw, 2012) – that involve communities as a key stakeholder in the management of disaster risk. Table 1 shows how community-based approaches could be employed to address the different dimensions of equity and prevent DRC.

Table I.

Ways that community-based approaches could enhance equity

| Equity dimension |

Potential Impact of Community-Based Approaches |

|---|---|

| Distributive | Resolves distribution and access issues through community stakeholder engagement Adapts complex systems of organizational and cultural context and knowledge into actionable, relevant solutions |

| Procedural | Shifts power in learning, and decision making Equalizes the ownership of actions in community, including through culturally supported leaders and organizations |

| Contextual | Creates space to include cultural and hybrid knowledge Formalizes and sustains long-term agreements to equalize relationships and partnerships to promote mutual benefit for community |

By positioning knowledge and decision-making authority as a combination of localized and federal actions, community approaches can fruitfully bring together multiple scales, allowing for a flexible and rapid response to hazard that is both centralized and decentralized. Along with a culture that values reliability and rewards risk reduction, organizational theorists that look at how organizations function reliably over time ascribe to this structure as critical (Weick et al., 1999, 2008; La Porte, 1996; Roberts, 1990).

Such structures also stand to help bridge the distance inherent in DRC through recreant organizational behavior. Broken trust in responsible institutions requires vulnerable observers to stand apart from those organizations themselves. Trust can be repaired, maintained, and built by closer engagement and collaboration between the community at risk and the organization, such as through community-based approaches.

However, care must be taken to employ the right kind of community-based approaches. Not all community-based interventions effectively address equity, and in some cases might contribute to inequity, particularly if community members are operationalized to reduce risk created at macro levels (Bankoff and Hilhorst, 2009; Clark-Ginsberg, 2021). Intra-community differences in power and resources that shape disaster risk and its management must also be navigated to avoid exacerbating intra-community inequity (Titz et al., 2018; Kapoor, 2002; Mosurska and Ford, 2020). Ultimately what is needed is what might be labeled a “high reliability approach” (Weick et al., 1999) to community-based disaster risk management, one where acute attention is paid to preventing disaster risk in an equitable and community- driven manner.

5.1. Limitations and future work

This study examined how organizational decisions can shape inequity and create disaster risk. It did not examine the structures shaping FEMA or other disaster management agencies, or how those structures could be successfully modified to reduce disaster risk creation. Future work should continue to engage in these organizational dimensions of disasters and disaster risk management by examining how organizational structures and processes can be reformed and improved to address risk and function reliably in ways that facilitate equity. Where are the lever points? What influences organizational behavior? Greater engagement on the previously mentioned organizational research on the sociology of risk could help advance the understanding of risk creation, equity, and community-based approaches for researchers and shed new light into organizational systems while also helping organizations move toward practical steps that can contribute to, or facilitate, equity.

Second is a need to improve understanding of how these organizational forces of inequity cascade and reiterate across vulnerable and marginalized communities and the organizations that serve them. What are the long-term implications of disaster management systems that foster neglect and inequity? How do individuals and households cope with, survive or even in some cases thrive in the face of such adversity? What processes of resistance do they engage in, and how can these processes be elevated? Given the repeated challenges for local actors to affect changes at the macro-level where risk is often being created, work related to transnational and global social movements might be helpful, as these modes of collaboration could potentially be used for organizing to prevent DRC. As part of this stream of work, efforts to disentangle the complex processes shaping how organizations affect DRC should also continue.

6. Conclusion

Through a systematic review of FEMA’s programs and equity, this paper sought to examine how disaster management agencies shape disaster risk creation. We found many documented issues related to contextual, procedural and distributive equity, suggesting that as much as their activities reduce risk, FEMA and other disaster management agencies can also play a role in DRC. Many of these issues relate to the top-down nature of FEMA’s approach to disaster management, suggesting community-based approaches might be fruitfully applied to reduce risk creation. An organizational focus also opens a new area for research and practice on preventing disaster risk creation, organizational theories of risk. Additional work should examine these organizational dimensions of risk, including identifying the “levers” that can be used to facilitate a more equitable approach to disaster management that provides for populations in need.

Funding Disclosure:

This study was supported by Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center, a federally funded research and development center operated by the RAND Corporation. Aaron Clark-Ginsberg was also funded by the National Science Foundation/National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, under the project entitled “Belmont Forum Collaborative Research: Community Collective Action to Respond to Climate Change Influencing the Environment-health Nexus” (Award number 2028065) and by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Gulf Research Program, under the project entitled “Capacity and Change in Climate Migrant-Receiving Communities Along the U.S. Gulf: A Three-Case Comparison” (Award number 200010900). Lena Easton-Calabria was funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences under the project entitled “NOLA HEAT-MAP: New Orleans Home, Environment, and Ambient Temperature: Measurements and Analysis for Preparedness” (Award number R01ES031955). Sonny S. Patel was supported by the Fogarty International Center and National Institute of Mental Health, of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43 TW010543 at Harvard University.

7. References

- Adamantidis A, Arber S, Bains JS, Bamberg E, Bonci A, Buzsaki G, Cardin JA, Costa RM, Dan Y, Goda Y, Graybiel AM, Hausser M, Hegemann P, Huguenard JR, Insel TR, Janak PH, Johnston D, Josselyn SA, Koch C, Kreitzer AC, Luscher C, Malenka RC, Miesenbock G, Nagel G, Roska B, Schnitzer MJ, Shenoy KV, Soltesz I, Sternson SM, Tsien RW, Tsien RY, Turrigiano GG, Tye KM and Wilson RI (2015), “Optogenetics: 10 years after ChR2 in neurons–views from the community”, Nature Neuroscience, Vol. 18 No. 9, pp. 1202–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara-Ayala I, Burton I, Lavell A, Mansilla E, Maskrey A, Oliver-Smith A and Ram,ırez- G,omez F (2021), “Root causes and policy dilemmas of the COVID-19 pandemic global disaster”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol. 52, p. 101892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen BL (2007), “Environmental justice and expert knowledge in the wake of a disaster”, Social Studies of Science, Vol. 37 No. 1, pp. 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Altman D (2020), “Understanding the US failure on coronavirus—an essay by Drew Altman”, British Medical Journal, Vol. 370 No. 3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez MK and Cardenas K (2019), “Evicting slums, ‘building back better’: resiliency revanchism and disaster risk management in Manila”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 43 No. 2, pp. 227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bankoff G and Hilhorst D (2009), “The politics of risk in the Philippines: comparing state and NGO perceptions of disaster management”, Disasters, Vol. 33 No. 4, pp. 686–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleemer Z and van der Klaauw W (2019), “Long-run net distributionary effects of federal disaster insurance: the case of Hurricane Katrina”, Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 110, pp. 70–88. [Google Scholar]

- Browne KE (2015), Standing in the Need: Culture, Comfort and Coming Home after Katrina, University of Texas Press, Austin, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Buttell F, Cannon CE, Rose K and Ferreira RJ (2021), “COVID-19 and intimate partner violence: prevalence of resilience and perceived stress during a pandemic”, Traumatology, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2020), COVID-19 Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity, CDC, available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html.

- Chandra A, Cahill M, Yeung D and Ross R (2018), Toward an Initial Conceptual Framework to Assess Community Allostatic Load: Early Themes from Literature Review and Community Analyses on the Role of Cumulative Community Stress, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Acosta J, Howard S, Uscher-Pines L, Williams M, Yeung D, Garnett J and Meredith LS (2011), “Building community resilience to disasters: a way forward to enhance national health security”, Rand Health Quarterly, Vol.1 No. 1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry AL and Cherry ME (1997), “A middle class response to disaster: FEMA’s policies and problems”, Journal of Social Service Research, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Ginsberg A (2021), “Risk technopolitics in freetown slums: why community based disaster management is no silver bullet”, in Remes JAC and Horowitz A (Eds), Critical Disaster Studies, University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Ginsberg A, Abolhassani L and Rahmati EA (2018), “Comparing networked and linear risk assessments: from theory to evidence”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol. 30, pp. 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Ginsberg A and Petrun Sayers EL (2020), “Communication missteps during COVID-19 hurt those already most at risk”, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, Vol. 28 No. 4, pp. 482–484. [Google Scholar]

- Collins TW (2009), “The production of unequal risk in hazardscapes: an explanatory frame applied to disaster at the US–Mexico border”, Geoforum, Vol. 40 No. 4, pp. 589–601. [Google Scholar]

- Collins TW and Jimenez AM (2016), “The neoliberal production of vulnerability and unequal risk”, in Dooling S (Ed.), Cities, Nature and Development, Routledge, pp. 62–81. [Google Scholar]

- Columbia Broadcasting System (2015), FEMA: Evidence of Fraud in Hurricane Sandy Reports, CBS News, available at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/fema-evidence-of-fraud-in-hurricane-sandy-reports/. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C and Block R (2007), Disaster: Hurricane Katrina and the Failure of Homeland Security, Macmillan, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias AP and Raju E (2020), “The politics of disaster risk governance and neo-extractivism in Latin America”, Politics and Governance, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 220–231. [Google Scholar]

- Domingue SJ and Emrich CT (2019), “Social vulnerability and procedural equity: exploring the distribution of disaster aid across counties in the United States”, The American Review of Public Administration, Vol. 49 No. 8, pp. 897–913. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy B (2017), “Hurricane Harvey hit Black people the hardest but they are still waiting for aid”, Newsweek. [Google Scholar]

- Eden L (2004), Whole World on Fire: Organizations, Knowledge, and Nuclear Weapons Devastation, Cornell University Press, Ithica and London. [Google Scholar]

- FEMA (2021a), Office of Equal Rights, available at: https://www.fema.gov/about/offices/equal-rights.

- FEMA (2021b), Resilient Nation Partnership Network, available at: https://www.fema.gov/business-industry/resilient-nation-partnership-network.

- Freudenburg WR (1993), “Risk and recreancy: Weber, the division of labor, and the rationality of risk perceptions”, Social Forces, Vol. 71 No. 4, pp. 909–932. [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard J-C (2009), “From marginality to further marginalization: experiences from the victims of the July 2000 Payatas trashslide in the Philippines”, J'amb,a: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lopez GA (2018), “The multiple layers of environmental injustice in contexts of (un) natural disasters: the case of Puerto Rico post-hurricane Maria”, Environmental Justice, Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gezici A and Ozay O (2020), “An intersectional analysis of COVID-19 unemployment”, Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 270–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation (2017), An Early Assessment of Hurricane Harvey’s Impact on Vulnerable Texans in the Gulf Coast Region: Their Voices and Priorities to Inform Rebuilding Efforts, Report, available at: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-An-Early-Assessment-of-Hurricane-Harveys-Impact-on-Vulnerable-Texans-in-the-Gulf.

- Hewitt K (1983a), “The idea of calamity in a technocratic age”, in Hewitt K (Ed.), Interpretation of Calamity: from the Viewpoint of Human Ecology, Allen & Unwin, Boston/Winchester, MA, pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt K (1983b), Interpretations of Calamity from the Viewpoint of Human Ecology, Allen & Unwin, Winchester and Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt K (2012), “Culture, hazard and disaster”, The Routledge Handbook of Hazards and Disaster Risk Reduction, Routledge, London, pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A (2020), Katrina: A History, 1915-2015, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Jerolleman A (2019), Disaster Recovery through the Lens of Justice, Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor I (2002), “The devil’s in the theory: a critical assessment of Robert chambers’ work on participatory development”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman I, Mercer J and Gaillard JC (2012), “Indigenous knowledge and disaster risk reduction”, Geography, Vol. 97, pp. 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kishore N, Marques D, Mahmud A, Kiang MV, Rodriguez I, Fuller A, Ebner P, Sorensen C, Racy F and Lemery J (2018), “Mortality in Puerto Rico after hurricane Maria”, New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 379 No. 2, pp. 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch H, Franco ZE, O’Sullivan T, DeFino MC and Ahmed S (2017), “Community views of the federal emergency management agency’s ‘whole community’ strategy in a complex US City: re-envisioning societal resilience”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 121, pp. 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- La Porte TR (1996), “High reliability organizations: unlikely, demanding and at risk”, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Laska S, Howell S and Jerolleman A (2018), “Chapter 5 - ‘Built-in’ structural violence and vulnerability: a common threat to resilient disaster recovery”, in Zakour MJ, Mock NB and Kadetz P (Eds), Creating Katrina, Rebuilding Resilience, Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 99–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RI, Adam A, Mann SK, Bliss W, Bliss JC and Randhawa M (2016), “Disaster preparedness resource allocation and technical support for native American tribes in California”, Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 351–365. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J and Kelman I (2012), “The good, the bad and the ugly: disaster risk reduction (DRR) versus disaster risk creation (DRC)”, PLoS Currents, Vol. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J (2006), The Impact of Katrina: Race and Class in Storm-Damaged Neighborhoods, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. [Google Scholar]

- Lucus V (2006), “Analysis of the baseline assessments conducted in 35 US state/territory emergency management programs: emergency management accreditation program (EMAP) 2003–2004”, Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, Vol. 3 No. 2, p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Ma C and Smith T (2020), “Vulnerability of renters and low-income households to storm damage: evidence from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico”, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 110 No. 2, pp. 196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maani N and Galea S (2020), “COVID-19 and underinvestment in the public health infrastructure of the United States”, The Milbank Quarterly, Vol. 98 No. 2, pp. 250–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado JK (2017), “Corexit to forget it: transforming Coastal Louisiana into an energy sacrifice zone”, Extraction: Impacts, Engagements, and Alternative Futures, pp. 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Maskrey A (2011), “Revisiting community-based disaster risk management”, Environmental Hazards-Human and Policy Dimensions, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott M, Mahanty S and Schreckenberg K (2013), “Examining equity: a multidimensional framework for assessing equity in payments for ecosystem services”, Environmental Science and Policy, Vol. 33, pp. 416–427. [Google Scholar]

- M,endez M, Flores-Haro G and Zucker L (2020), “The (in)visible victims of disaster: understanding the vulnerability of undocumented Latino/a and indigenous immigrants”, Geoforum, Vol. 116, pp. 50–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirvis PH (2020), “Reflections: US coronavirus crisis management–learning from failure January– April, 2020”, Journal of Change Management, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 283–311. [Google Scholar]

- Mosurska A and Ford JD (2020), “Unpacking community participation in research: a systematic literature review of community-based and participatory research in Alaska”, Arctic, Vol. 73 No. 3, pp. 347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Moulton AAM and Machado MR (2019), “Bouncing forward after Irma and Maria: acknowledging colonialism, problematizing resilience and thinking climate justice”, Journal of Extreme Events, Vol. 6, p. 1940003. [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Stevens SP, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche KF and Pfefferbaum RL (2008), “Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness”, American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 41 Nos 1-2, pp. 127–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Smith A, Alcantara-Ayala I, Burton I and Lavell A (2017), “The social construction of disaster risk: seeking root causes”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol. 22, pp. 469–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppizzi LM and Speraw S (2016), “Federal emergency management agency response in rural appalachia: A tale of miscommunication, unrealistic expectations, and ‘hurt, hurt, hurt’”, Nursing Clinics of North America, Vol. 51 No. 4, pp. 599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pareja V (2019), “Weathering the second storm: how bureaucracy and fraud curtailed homeowners’ efforts to rebuild after Superstorm Sandy”, Hofstra Law Review, Vol. 47 No. 3, pp. 925–963. [Google Scholar]

- Patel SS, Rogers MB, Aml^ot R and Rubin GJ (2017), “What do we mean by ‘community resilience’? A systematic literature review of how it is defined in the literature”, PLoS Currents, Vol. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrow C (1984), Normal Accidents: Living with High Risk Technologies, Basic Books, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Perrow C (2015), “Cracks in the ‘regulatory state”, Social Currents, Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Pescaroli G and Alexander D (2015), “A definition of cascading disasters and cascading effects: going beyond the ‘toppling dominos’ metaphor”, Planet@ Risk, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Peters LE (2021), “Beyond disaster vulnerabilities: an empirical investigation of the causal pathways linking conflict to disaster risks”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, p. 102092. [Google Scholar]

- Prime H, Wade M and Browne DT (2020), “Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic”, American Psychologist, Vol. 75 No. 5, p. 631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA (2020), PRISMA Checklist, available at: statement.org/documents/PRISMA_2020_checklist.pdf.

- Reid M (2013), “Social policy, ‘deservingness,’ and sociotemporal marginalization: Katrina survivors and FEMA”, Sociological Forum, Vol. 28, pp. 742–763. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke AJ and Eldridge ER (2020), “Navigating the ‘bureaucratic beast’ in North Carolina Hurricane recovery”, Human Organization, Vol. 79 No. 2, pp. 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera JD and Miller DS (2007), “Continually neglected - situating natural disasters in the African American experience”, Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 37 No. 4, pp. 502–522. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts KH (1990), “Some characteristics of one type of high reliability organization”, Organization Science, Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 160–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrıguez-Dıaz CE (2018), “Maria in Puerto Rico: natural disaster in a colonial archipelago”, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 108 No. 1, pp. 30–32, doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbach A and Nemeth J (2018), “Disaster risk creation in the darjeeling Himalayas: moving toward justice”, Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, Vol. 1 No. 3, pp. 340–362. [Google Scholar]

- Sagan SD (1995), The Limits of Safety: Organizations, Accidents, and Nuclear Weapons, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Sakauye KM, Streim JE, Kennedy GJ, Kirwin PD, Llorente MD, Schultz SK and Srinivasan S (2009), “AAGP position statement: disaster preparedness for older Americans: critical issues for the preservation of mental health”, American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, Vol. 17 No. 11, pp. 916–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval V and Sarmiento JP (2020), “A neglected issue: informal settlements, urban development, and disaster risk reduction in Latin America and the Caribbean”, Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, Vol. 29 No. 5, pp. 731–745. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramutti C, Salas-Wright CP, Vos SR and Schwartz SJ (2019), “The mental health impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico and Florida”, Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 24–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P and Stewart LA (2015), “Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation”, British Medical Journal, Vol. 349, available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g7647. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw R (2012), “Community-based disaster risk reduction”, in Shaw R (Ed.), Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction (Community, Environment and Disaster Risk Management, Vol. 10), Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, p. i, doi: 10.1108/S2040-7262(2012)0000010027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, Sia IG and Wieland ML (2020), “The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States”, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 72 No. 4, pp. 703–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Annie E Casey Foundation (2014), Embracing Equity: 7 Steps to Advance and Embed Race Equity and Inclusion within Your Organization, available at: https://www.aecf.org/resources/race-equity-and-inclusion-action-guide/. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney K (2012), “A bridge to somewhere: William Freudenburg, environmental sociology, and disaster research”, Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Titz A, Cannon T and Kru€ger F (2018), “Uncovering ‘community’: challenging an elusive concept in development and disaster related work”, Societies, Vol. 8 No. 3, p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan D (1996), The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan D (1999), “The dark side of organizations: mistake, misconduct, and disaster”, Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 271–305. [Google Scholar]

- Verderber S (2008), “Emergency housing in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: an assessment of the FEMA travel trailer program”, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, Vol. 23 No. 4, pp. 367–381. [Google Scholar]

- Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM and Obstfeld D (1999), “Organizing for high reliability: processes of collective mindfulness”, Research in Organizational Behavior, Elsevier Science/JAI Press, Vol. 21, pp. 81–123. [Google Scholar]

- Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM and Obstfeld D (2008), “Organizing for high reliability: processes of collective mindfulness”, Crisis Management, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 31–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner B and Lavell A (2017), “The next paradigm shift: from ‘disaster risk reduction’ to ‘resisting disaster risk creation’ (DRR > RDRC)”, Dealing with Disasters Conference, University of Durham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner B, Blaikie P, Cannon T and Davis I (2004), At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters, Routledge, London and New York. [Google Scholar]

- Xu HD and Basu R (2020), “How the United States Flunked the COVID-19 test: some observations and several lessons”, The American Review of Public Administration, Vol. 50 Nos 6-7, pp. 568–576. [Google Scholar]