Significance

In the current digital age, people are constantly connected to online information. The present research provides evidence that on-demand access to external information, enabled by the internet and search engines like Google, blurs the boundaries between internal and external knowledge, causing people to believe they could—or did—remember what they actually just found. Using Google to answer general knowledge questions artificially inflates peoples’ confidence in their own ability to remember and process information and leads to erroneously optimistic predictions regarding how much they will know without the internet. When information is at our fingertips, we may mistakenly believe that it originated from inside our heads.

Keywords: knowledge, memory, cognition, attribution

Abstract

People frequently search the internet for information. Eight experiments (n = 1,917) provide evidence that when people “Google” for online information, they fail to accurately distinguish between knowledge stored internally—in their own memories—and knowledge stored externally—on the internet. Relative to those using only their own knowledge, people who use Google to answer general knowledge questions are not only more confident in their ability to access external information; they are also more confident in their own ability to think and remember. Moreover, those who use Google predict that they will know more in the future without the help of the internet, an erroneous belief that both indicates misattribution of prior knowledge and highlights a practically important consequence of this misattribution: overconfidence when the internet is no longer available. Although humans have long relied on external knowledge, the misattribution of online knowledge to the self may be facilitated by the swift and seamless interface between internal thought and external information that characterizes online search. Online search is often faster than internal memory search, preventing people from fully recognizing the limitations of their own knowledge. The internet delivers information seamlessly, dovetailing with internal cognitive processes and offering minimal physical cues that might draw attention to its contributions. As a result, people may lose sight of where their own knowledge ends and where the internet’s knowledge begins. Thinking with Google may cause people to mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own.

No one can know everything. Throughout history, people have overcome this fundamental limitation of the individual brain by relying on the knowledge of others. Friends, lovers, and colleagues intuitively form “transactive memory systems” that divide the mental labor of attending to, processing, and remembering information between the members of the group (1). These shared cognitive systems allow people to navigate the informational demands of the world in ways that no individual could do alone. No one person needs to know everything—they simply need to know who knows it. More broadly, people frequently build their own understanding on the presumed understanding of others (2, 3). Breakthroughs in cancer treatment and rocket science are possible not because individual experts know everything there is to know on the subject but because people are capable of drawing on and using knowledge that does not reside in their own heads. These forms of knowledge sharing may help explain the remarkable success of the human species (4); they enable people to conquer complex problems, make new scientific discoveries, and manage the minutiae of everyday life. The frequency and facility with which people incorporate others’ knowledge into their own cognitive processes also reveals that individual human cognition is not really individual at all. Thinking, remembering, and knowing are often collaborative, a product of the interplay between internal and external cognitive resources (1–6).

Over the past quarter century, human cognition has become increasingly intertwined with a new cognitive collaborator: the internet. The knowledge-sharing systems that long forged connections between individual brains now link to a vast compendium of collective knowledge that can be accessed any time, from anywhere. Like the memory partners that have shaped and supported individual cognition throughout human history, the internet allows for the expansion of the mind by serving as a form of external memory that can be consulted on an as-needed basis (7). However, the internet is also different from traditional memory partners. It knows practically everything and is almost always available. Through search engines like Google, it delivers information in fractions of a second; and it delivers this information seamlessly, dovetailing with internal cognitive processes and providing minimal cues to its contributions. Together, these distinctive features of the internet and online search may blur the boundaries between internal knowledge—stored in personal memory—and external knowledge—found online. They may cause people to mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own. The present research investigates this possibility.

In a world in which the answer to virtually any question can be called up at a moment’s notice, people may frequently fail to recognize the limits of their own knowledge. Of course, people are often aware of what they do and do not know; for example, most Americans know that they know the name of the current US president and that they do not know where to find Ulaanbaatar on a map. However, for the wide swath of topics in between—everything that is not immediately known but not immediately known to be unknown—people frequently experience a “feeling of knowing” (8); they believe that they do or could know information, even if they cannot immediately bring it to mind. These feelings of knowing may be falsely confirmed by on-demand access to online information. People often search the internet for information before searching their own memories (9), even when they believe they could probably answer these questions on their own (10). Search engines like Google return answers in fractions of a second (11), often faster than knowledge can be found in—or found to be missing from—long-term memory (12, 13). When the desired information appears on screen before people can finish searching their own memory, they may erroneously believe that they knew it all along. Thinking with Google may cause people to believe that they always knew what they never could have known alone.

At times, people may not only believe that knowledge found online could have been found in personal memory; they may believe that they actually did retrieve this knowledge from their own minds. Research on authorship processing (14, 15) and source monitoring (16, 17) reveals that people do not have direct insight into the source of their mental contents; rather, they distinguish between internally and externally generated knowledge based on differences between the typical experiences of recalling information from personal memory versus encountering information in the world. People attribute knowledge to the self when it follows the logical and temporal flow of the stream of consciousness (14, 15)—that is, when it is associated with the cognitive operations involved in thinking alone (16, 17). In contrast, people recognize that information originated outside their heads when it is accompanied by additional sensory and contextual information that does not exist in the environs of the mind (14–17). These implicit rules for differentiating between internal and external knowledge may work well when external knowledge is housed in traditional memory partners. The lengthy, laborious, and embodied process of phoning a friend or consulting a reference volume not only differs from the cognitive operations involved in searching one’s own memory but also provides experiential cues indicating where the information was ultimately found. However, the cognitive operations involved in searching Google are similar to those involved in retrieving facts from one’s own memory: A question is posed and, a short time later, an answer appears (18). Moreover, this information is delivered as unobtrusively as possible. As stated by cofounder Sergey Brin, Google is intentionally designed to be less like an external tool and more like “the third half of your brain” (19)—a knowledge interface so seamless that searching feels like thinking. This interface between internal cognitive processes and online information may further fade from view as users habitually search the internet for information throughout their day-to-day lives (20, 21). As a result, one’s own memory may be the most salient explanation for information that appears on screen—and in mind—and people may misattribute online search results to their own memory. Thinking with Google may cause people to believe they remembered what they actually just found.

Eight experiments (n = 1,917) examine the possibility that when people use Google to search for and access information, they fail to accurately distinguish between internal knowledge—retrieved from their own memories—and external knowledge—found on the internet. In a typical experiment, participants answer a series of general knowledge questions either with or without Google. Those who use Google invariably answer more questions correctly. The critical question is not one of performance but of attribution: Do Google users appropriately acknowledge the internet as the source of their knowledge, or do they erroneously misattribute this knowledge to themselves? Experiments 1 through 4 provide evidence that people mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own. After using Google to answer questions, people are more confident in their personal cognitive ability; they are more likely to endorse statements such as “I am smart” and “I have a better memory than most people.” They also erroneously predict that they will perform better on subsequent knowledge tests taken without access to the internet. Beyond providing converging evidence of knowledge misattribution using validated measures (22, 23), these results are also meaningful in their own right. Self-evaluations speak to how interfacing with online information may shape the self-concept, and performance predictions represent a practically important consequence of misattributing online search results to personal memory: overconfidence when the internet’s knowledge is no longer available. Experiments 5 through 8 examine how the speed and seamlessness of internet search may explain these effects.

Results

Experiment 1.

Participants in Experiment 1 answered 10 general knowledge questions either on their own or using online search, then completed the Cognitive Self-Esteem (CSE) scale (24): a self-report measure of one’s perceived ability to remember (e.g., “I have a better memory than most people”), process (e.g., “I am smart”), and access (e.g., “When I don’t know the answer to a question, I know where to find it”) information. Responses to the thinking and memory subscales were averaged to form a measure of attributions to internal knowledge (CSE internal; α = 0.911). Responses to the access subscale measured attributions to external knowledge (CSE external; α = 0.828). If people properly attribute information found online to the internet, they may feel more confident in their ability to access external knowledge after using Google. They should not, however, feel more confident in their own knowledge—if anything, recognition of the internet’s contributions may reduce confidence in personal knowledge due to the sensation of comparative ignorance (25, 26). If, on the other hand, people mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own, using Google may cause people to become more confident in their own ability to remember information.

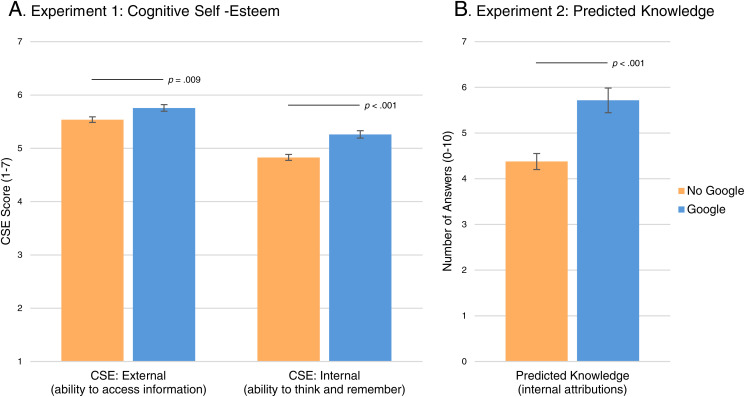

Participants who used Google answered significantly more questions correctly (M = 8.87 and SD = 1.09) than those who did not (M = 2.68 and SD = 1.84): F(1,541) = 1838.36, P < 0.001, and η2p = 0.77; BF+0 = 1.40 × 10172. As shown in Fig. 1A, these participants were indeed more confident in their ability to access external knowledge [F(1,541) = 6.90, P = 0.009, and η2p = 0.01; BF+0 = 5.55]. However, they were also significantly more confident in their own memory [F(1,541) = 22.27, P < 0.001, and η2p = 0.04; BF+0 = 8329.80]—a result that would only be expected if people believed that knowledge found online already resided within their own heads.

Fig. 1.

Effects of online search on the perceived ability to both access external knowledge and retrieve internal knowledge from personal memory (A) and on predicted personal knowledge without access to the internet (B). Error bars are ± 1 SE.

Participants also completed one of nine measures assessing other facets of self-esteem, such as Rosenberg global self-esteem (27) and measures of perceived physical, social, and mathematical ability (28). If thinking with Google simply induces positive affect or makes people feel more capable at a general level, it may have diffuse effects on self-perception. However, failure to appropriately recognize the contributions of this cognitive collaborator should produce a localized effect on self-perceptions related to knowledge. Consistent with this hypothesis, using Google did not affect any non-CSE measures (ps > 0.07). People do not feel more confident in their ability to navigate social interactions or solve math problems after using Google, but they do feel more confident in their ability to remember information.

Experiment 2.

Experiment 2 tested for conceptual replication of Experiment 1 using a different measure of knowledge attribution: predicted performance on a general knowledge test to be taken without access to external resources (23). After answering 10 general knowledge questions either with or without Google, half of the participants in Experiment 2 were randomly assigned to complete the same CSE measure used in Experiment 1. All participants were then informed that they would take a second knowledge test, “similar in difficulty to the quiz you just took,” and would be “unable to use any outside sources for help” on this test. Participants were asked to predict how many questions (out of 10) they would answer correctly when relying only on their own internal knowledge. If people who use Google to answer an initial set of questions truly believe that their high performance is due to their own knowledge, they should predict continued high performance when their own knowledge is all they have.

As shown in Fig. 1B, participants who completed the first knowledge test with the aid of Google predicted that they would know significantly more when forced to rely only on their own memory in the future: F(1, 285) = 18.42, P < 0.001, and η2p = 0.061; BF+0 = 1,396.06. Replicating Experiment 1, participants in the Google condition were significantly more confident than those in the no Google condition in their abilities to both access external information [MGoogle = 6.01 and SD = 0.84; MNoGoogle = 5.64 and SD = 0.96; F(1,140) = 4.81, P = 0.030, and η2p = 0.033; and BF+0 = 3.26] and remember information on their own [MGoogle = 5.43 and SD = 0.97; MNoGoogle = 4.96 and SD = 1.23; F(1,140) = 4.94, P = 0.028, and η2p = 0.024; and BF+0 = 3.46]. Notably, there was no effect of reporting CSE on predicted knowledge (Fs < 2.29 and ps > 0.131), indicating that these misattributions occur—and influence expectations regarding future performance—even when people are not explicitly asked to reflect on their own knowledge.

Experiment 3.

Experiment 3 examined an alternate explanation and potential consequence of the results of Experiment 2. It may be that elevated performance predictions after using Google in Experiment 2 do not reflect increased confidence in one’s own knowledge but, rather, increased motivation to access this knowledge. If so, people who perform well with the assistance of the internet on an initial knowledge test may actually perform better on subsequent tests taken alone (29, 30); their confidence, though elevated, may be justified. However, if these performance predictions reflect erroneous beliefs regarding one’s own knowledge, on-demand access to online information may carry an important consequence: overconfidence when the internet is no longer available.

Participants in Experiment 3 completed two knowledge tests. For purposes of generalizability, tests were randomly generated for each participant by stimulus sampling from a larger pool of general knowledge questions. Participants were randomly assigned to complete the first test either with or without Google. Immediately after completing this test, all participants received the correct answers to all questions. They then predicted how well they would perform on the second test, to be taken without access to any external knowledge. Finally, they took the second test.

Replicating Experiment 2, those who used Google to complete the first test expected to perform significantly better on the second test, even without access to the internet (MGoogle = 5.95 and SD = 2.40; MNoGoogle = 4.58 and SD = 2.24): F(1, 157) = 13.73, P < 0.001, and η2p = 0.080; and BF+0 = 161.59. However, these participants did not actually perform better on the second test (MGoogle = 3.73 and SD = 2.34; MNoGoogle = 3.17 and SD = 2.39): F(1, 157) = 2.25, P = 0.136, and η2p = 0.014; and BF+0 = 0.89. These results both provide further evidence that people take personal credit for the knowledge contained in online search results and highlight how failure to appreciate the internet’s contributions may lead to overconfidence: Because of this divergence between perceived and actual personal knowledge, participants in the Google condition were significantly more miscalibrated in their predictions of future performance (MGoogle = 2.21 and SD = 2.81; MNoGoogle = 1.35 and SD = 2.25): F(1, 156) = 4.59, P = 0.034, and η2p = 0.029; and BF10 = 2.80 × 1040.

Experiment 4.

Experiment 4 used a false feedback paradigm to compare the performance predictions and CSE scores of people who used Google to perform well on a general knowledge test to those of people who believed they performed similarly well using only their own internal knowledge. Participants were randomly assigned to a Google, no Google, or no Google + false feedback condition. All participants first completed a 10-item general knowledge test and were required to provide an answer for every question. After answering all 10 questions, those in the no Google + false feedback condition—who completed the test using only their own internal knowledge—were told that they answered 8 of 10 questions correctly. Under the guise of providing feedback on the technical performance of an automated grading algorithm, participants in this condition were asked to report “if you feel like the service made an error in your score.” This technical feedback was used to split participants in the false feedback condition into two subgroups: those who believed the feedback (i.e., those who believed that they answered eight out of ten questions correctly using only their own internal knowledge) and those who did not. All participants then completed the same CSE and performance prediction measures used in prior experiments.

Pairwise comparisons revealed that participants in the Google condition were equally confident in their own memory (M = 5.50 and SD = 1.00) as those who believed the false feedback manipulation (M = 5.27 and SD = 0.80; P = 0.363; and BF10 = 0.40). Similarly, participants in these two groups predicted equal levels of knowledge when relying only on their own memory (MGoogle = 5.80 and SD = 2.58; MFFBelief = 6.60 and SD = 1.99; P = 0.126; and BF10 = 0.64). On the other end of the spectrum, participants in the no Google condition did not differ from those who did not believe the false feedback on either CSE internal scores (MNoGoogle = 4.88 and SD = 1.32; MFFDisbelief = 4.60 and SD = 1.04; P = 0.336; and BF10 = 0.36) or predicted knowledge (MNoGoogle = 4.19 and SD = 2.28; MFFDisbelief = 4.58 and SD = 1.89; P = 0.505; and BF10 = 0.33).

Replicating Experiments 1 through 3, participants in the Google condition had significantly higher CSE internal scores than those in the no Google condition (P = 0.019; BF+0 = 3.06) and those who did not believe the false feedback (P = 0.002; BF+0 = 30.61). Participants who used Google also predicted that they would know significantly more without the internet than those in the no Google condition (P = 0.005; BF+0 = 8.42) and those who did not believe the false feedback (P = 0.045; BF+0 = 2.42). Participants who believed the false feedback displayed a similar pattern of results as those who used Google; full analyses are provided in the SI Appendix.

The striking similarity between participants in the Google condition and participants who believed the false feedback provides additional evidence that people misattribute online knowledge to the self; those who knew a lot because they had access to Google made equal evaluations of their own knowledge as those who believed they knew a lot entirely on their own.

Experiment 5.

Experiment 5 introduced a new condition in which people were required to write down their own answers before consulting Google. This design holds access to external information constant, while manipulating the potential for ambiguity regarding the limitations of personal knowledge. If Google’s effects on evaluations of internal knowledge are simply due to positive spillover from perceived access to external knowledge, one would expect similar effects whenever people have access to the internet. However, if these effects occur in part because Google blurs the boundaries between internal and external knowledge, they should not replicate when people are required to exhaust internal search prior to accessing external information.

Pairwise comparisons indicated that participants who wrote down their own answers before consulting Google were equally confident in their ability to access external knowledge as those who used Google with no special instructions (MGoogle = 5.95 and SD = 0.97; MGoogle+WriteAnswers = 5.82 and SD = 0.91; P = 0.536; and BF+0 = 0.40). However, they scored significantly lower on both measures of misattribution: Compared to those who used Google as usual, those who used Google only after writing their own answers had significantly lower CSE internal scores (MGoogle = 5.61 and SD = 0.77; MGoogle+WriteAnswers = 4.99 and SD = 1.00; P = 0.003; and BF+0 = 45.04) and predicted that they would know significantly less on a future knowledge test taken without access to external resources (MGoogle = 5.80 and SD = 2.20; MGoogle+WriteAnswers = 4.47 and SD = 1.94; P = 0.005; and BF+0 = 21.15). These results suggest that the typical process of online search obscures the relative contributions of internal versus external knowledge; when the limitations of personal knowledge are made salient, people no longer believe they know what the internet knows.

Experiment 6.

Experiment 6 examined the possibility that people misattribute online search results to personal memory in part because Google completes external search faster than the human brain completes internal search (11–13). If Google answers questions before users can finish searching their own memories, people may never realize that internal search would have turned up empty; they may mistakenly believe that they could—or did—remember information that they in fact would not have known without the internet. Artificially slowing the process of an online search may reduce misattribution by giving people time to recognize the limitations of their own knowledge—similar to the effect of explicitly requiring participants to exhaust the internal search before accessing external knowledge in Experiment 5.

Participants in Experiment 6 answered 10 general knowledge questions either on their own, with Google, or with a modified version of Google that delayed search results by 25 s. Participants who used slow Google to answer questions were no more confident in their own internal knowledge (M = 5.18 and SD = 0.83) than those who did not use Google (M = 5.03 and SD = 1.04; pairwise comparison P = 0.438; and BF10 = 0.27), and were directionally but not significantly less confident than those who used unmodified Google (M = 5.54 and SD = 0.96; P = 0.063; and BF+0 = 2.32). Similarly, those who used slow Google did not predict higher performance on a future knowledge test (M = 4.13 and SD = 1.94) than those who did not use Google (M = 3.81 and SD = 1.91; P = 0.415; and BF10 = 0.28), and predicted directionally but not significantly lower performance than those who used unmodified Google (M = 4.80 and SD = 2.07; P = 0.089; and BF+0 = 1.39). These data suggest that search speed is at least partially responsible for knowledge misattributions following online search. When external information was delayed by a mere 25 s, Google did not increase CSE internal scores or predictions of future knowledge.

Experiment 7.

Experiments 5 and 6 suggest that misattribution of online knowledge to the self is facilitated by ambiguity regarding the contents of personal knowledge. The extraordinary ability of the internet to swiftly and seamlessly produce information may corroborate feelings of knowing for information that people cannot immediately bring to mind—even if this information does not actually reside within the recesses of personal memory.

Experiment 7 examined the role of knowledge ambiguity in online search by randomly assigning participants to answer easy, medium, or hard questions either with or without Google. When questions are easy, people should know the answers almost immediately, leaving no room for misattribution. When questions are particularly hard, people should know that they don’t know the answers, leaving similarly little room for misattribution. However, when questions are of moderate difficulty, people may be predisposed to believe they remembered what they actually just found.

Replicating Experiments 1 through 6, participants who answered moderately difficult questions were significantly more confident in their own internal knowledge after using Google than after answering questions on their own. Those who used Google believed that they were smarter and better at remembering than those who did not (MGoogle = 5.35 and SD = 0.93; MNoGoogle = 4.98 and SD = 0.93; pairwise comparison P = 0.028 and η2p = 0.014; and BF+0 = 3.11) and also predicted that they would know more in the future without access to external resources (MGoogle = 5.29 and SD = 2.14; MNoGoogle = 4.41 and SD = 2.12; P = 0.020 and η2p = 0.015; and BF+0 = 3.85). Consistent with expectations, Google had no effect on either measure for those answering easy questions (ps > 0.317; BFs+0 < 0.22). For those answering hard questions, Google did not affect CSE internal scores (P = 0.229; BF+0 = 0.10); however, those who used Google did expect to know significantly more when asked similarly difficult questions in the future (MGoogle = 4.44 and SD = 2.22; MNoGoogle = 2.47 and SD = 2.39; P < 0.001 and η2p = 0.068; and BF+0 = 2,197.02).

Together with Experiments 5 and 6, these results suggest that on-demand access to online information may distort estimates of personal knowledge by falsely confirming the feeling of knowing. Though unexpected, elevated predictions of future performance among those who used Google to answer hard questions suggest that online search may not just capitalize on, but also create, knowledge ambiguity. Post hoc analyses of this result indicated that, for participants who answered questions on their own, predicted knowledge was most closely associated with past performance (Fisher’s z = 2.78 and P = 0.005); for those who used Google, predicted knowledge was most closely associated with CSE internal scores (Fisher’s z = −2.46 and P = 0.007). When people perform well because they have access to all the answers, performance is not directly a diagnostic of what one actually knows. People may thus base their predictions of personal knowledge not on how well they did but on how knowledgeable they feel.

Summary Analyses of Experiments 1 through 7.

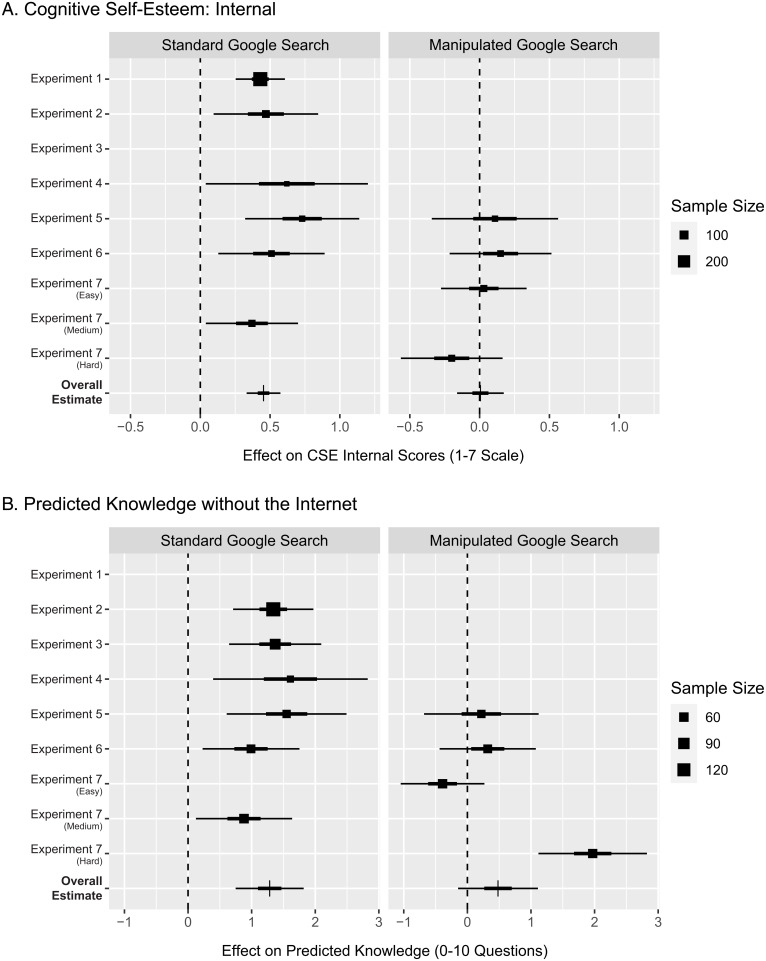

Experiments 1 through 7 provide consistent evidence that thinking with Google blurs the boundaries between internal and external knowledge, causing elevated confidence in personal memory and erroneously optimistic predictions of how much one will know when external knowledge is no longer available. A series of single-paper meta-analyses (31), shown in Fig. 2, summarize these results. Fig. 2A shows the effect of using Google to answer questions on confidence in personal memory. Under normal circumstances, the effect of online search on evaluations of internal knowledge is estimated at 0.48 on a 1 to 7 scale (95% CI: 0.36 to 0.61); however, when the contents of personal memory are clarified by requiring people to exhaust internal search, artificially slowing the speed of online search results, or asking people to search for answers to very easy or very hard questions, Google no longer influences CSE internal scores (estimate = 0.01 and 95% CI: −0.17 to 0.20). Fig. 2B displays a similar pattern of results for predicted knowledge without access to external resources; the effect of unadulterated Google search on predicted future knowledge is estimated at 1.24 questions out of 10 (95% CI: 0.92 to 1.56), but this effect is eliminated by clarifying the boundaries of one’s own knowledge (estimate = 0.51 and 95% CI: −0.48 to 1.50). As detailed in the SI Appendix, seamless access to online information also increases confidence in access to external information (CSE external estimate = 0.29 and 95% CI: 0.18 to 0.40).

Fig. 2.

Single-paper meta-analyses of the effect of online search on confidence in personal memory (A) and predicted knowledge without the internet (B). The thick and thin lines represent 50 and 95% CIs, respectively. The average sample size per condition is indicated by the size of the squares.

Although on-demand access to online information increases confidence in both internal and external knowledge, a multilevel mediation analysis incorporating the data from Experiments 1 through 7 provides evidence that the effect on evaluations of internal knowledge does not merely reflect spillover from evaluations of access to external knowledge; after accounting for indirect effects through CSE external scores (0.20 and 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.28), the effect of Google on CSE internal scores remained significant (0.27 and 95% CI: 0.17 to 0.37).

Consistent with the conceptual argument that predicted future knowledge reflects attributions of prior knowledge to internal memory rather than external sources, a second mediation analysis indicated that the effect of online search on predicted knowledge was mediated by CSE internal scores (0.36 and 95% CI: 0.23 to 0.52) but not by CSE external scores (0.05 and 95% CI: −0.02 to 0.13).

Experiment 8.

Experiments 1 through 7 provide evidence that using Google to access online information causes people to mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own. However, these experiments cannot speak to whether people truly believe this knowledge was produced from their own memories or if they accurately recognize that the information was found online but inaccurately believe that they could have produced this information themselves if Google had not beaten them to the punch. Nor can these experiments speak to the role that seamlessness—that is, concordance with the cognitive operations involved in internal memory search—may play in the misattribution of online knowledge to the self.

Experiment 8 used a source confusion paradigm to shed light on both questions. Participants (n = 156) answered a series of 50 general knowledge questions and were instructed to answer each question using either their own knowledge or an online repository (Google or Wikipedia, randomly assigned between conditions). Participants in the Wikipedia condition were provided with a direct link to the relevant Wikipedia page. Both online information sources are equally accessible, and results indicated that participants in both conditions were able to retrieve the desired information equally quickly (P = 0.868; BF10 = 0.18). However, the two sources differ in the extent to which they align with the experience of recalling information from personal memory. Retrieving answers from Google may often feel like “just knowing” (18); in contrast, encountering and sifting through additional contextual information when searching for answers on Wikipedia may serve as a salient reminder that this knowledge originated in an external source.

After a 5-min delay, participants were shown 70 questions (all 50 from part one, plus 20 new questions) and asked to indicate whether each question had been answered using internal knowledge, had been answered using the internet, or was new. If people misattribute online search results to personal memory, they should erroneously report that questions answered using Google were answered using internal knowledge. If searching Google is more seamless than reading Wikipedia, this source confusion should be more common for participants randomly assigned to use Google.

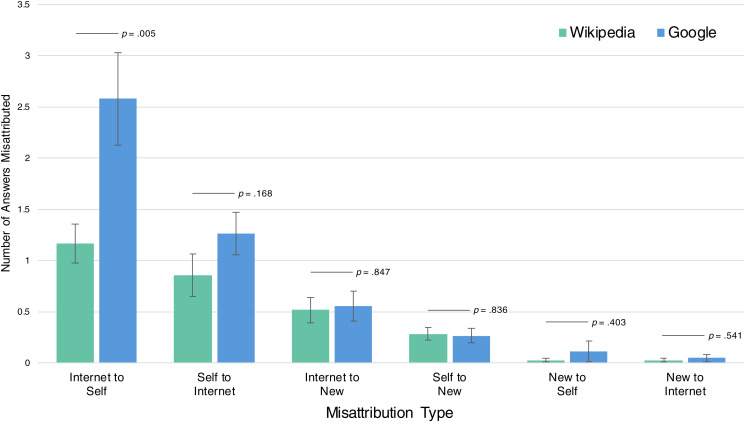

When asked to identify the source of information, participants who used Google were significantly less accurate than those who used Wikipedia [MGoogle = 4.84 and SD = 6.30; MWiki = 2.88 and SD = 3.77; F(1, 154) = 5.48, P = 0.02, and η2p = 0.034; and BF+0 = 4.15]. Critically, this inaccuracy was explained by errors in the attribution of external knowledge [MGoogle = 21.86 and SD = 4.53; MWiki = 23.31 and SD = 2.14; F(1, 154) = 6.48, P = 0.012, and η2p = 0.04; and BF−0 = 6.55]. Specifically, participants in the Google condition were significantly more likely to attribute online information to the self than were those in the Wikipedia condition [MGoogle = 2.58 and SD = 0.35; MWiki = 1.17 and SD = 0.35; F(1, 154) = 8.17, P = 0.005, and η2p = 0.05; and BF+0 = 13.98]. As shown in Fig. 3, there were no differences between conditions in any other form of source confusion (ps > 0.17; BFs < 0.42).

Fig. 3.

Misattribution of knowledge source after using Google versus Wikipedia to find answers to general knowledge questions. Answers from Google were significantly more likely to be misattributed to personal memory. Error bars are ± 1 SE.

These results suggest that seamless connection to online information does not just blur the boundaries between internal and external knowledge—at times, it may erase these boundaries entirely, leading people to believe that information found online was in fact found within their own skulls. The finding that misattribution is more common for Google than for Wikipedia, despite the fact that both offer easy access to information on virtually any topic, is consistent with the principles of authorship processing and source monitoring: Thinking with Google, which delivers information as unobtrusively as possible, may simply feel more like thinking alone. Experiment 8B, reported in the SI Appendix, finds similar results in a comparison of Google (which was regularly used by over 90% of the sample) and Lycos (which was not regularly used by anyone)—suggesting that seamless connections between internal and external knowledge may be facilitated by both design features of technology and the automaticity that comes from repeated use (19–21). As the process of “Googling” for information becomes increasingly habitual, it may also become increasingly invisible. The internet may become less like a library and more like a neural prosthetic, connected not by wires but by incessant and instantly accessible streams of data.

Discussion

In the digital age, the internet is a constant collaborator in everyday cognition. Through search engines like Google, the most comprehensive body of collective knowledge the world has ever seen is never more than a tap, click, or voice command away. Sophisticated search algorithms seem to finish one’s thoughts, providing answers even before questions can be fully formed. The present research provides evidence that this seamless interface between internal cognitive processes and external information may cause people to mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own. Compared to people using only their own internal knowledge, those who used online search to answer general knowledge questions were more confident in their own memory and predicted that they would know more in the future when the internet was no longer available. At times, people even forgot that they had “Googled” at all; they claimed that answers found online had been produced entirely from their own memory.

These findings contribute to an emerging understanding of how on-demand access to external information may shape human cognition. Prior research on the “Google Effect” has shown that people fail to encode information in personal memory when they know it is being stored online (32–34). The present research identifies another Google Effect—not on what people actually know but on what they believe they know. Taken together, these Google Effects on real and perceived knowledge suggest that in a world in which searching the internet is often faster and easier than searching one’s own memory, people may ironically know less but believe they know more.

The present research examines how the process of retrieving information from the internet may cause people to take personal credit for online knowledge. However, these results may also speak to more general metacognitive distortions caused by unfailing access to external knowledge. For much of human history, keeping track of who knows what—and what one knows—has been critical for making sure that important information does not fall through the cracks (1, 35, 36). When access to external knowledge is inefficient and unreliable, distinguishing between the knowledge that resides in one’s head and knowledge that must be retrieved from external sources helps ensure that people will know what they need to know when they are alone. But in a world in which external knowledge is always accessible, keeping track of exactly where knowledge is stored may impose substantial cognitive costs while offering few cognitive benefits (2, 3, 37). The distinction between internal and external knowledge may not just be difficult to discern—it may be increasingly irrelevant.

This vision of humankind as a race of subtle cyborgs, connected to the cloud mind of the internet by the omnipresent flow of online information, calls for research into the future of education, decision-making, and belief. Accessing online information not only causes people to take personal credit for facts found on the internet, but also to feel more confident in their ability to explain how things work (38). This artificially elevated confidence in one’s own knowledge and understanding may distort judgments of learning (39) and the motivation to learn (40), two key determinants of effective education. Why would people devote time and effort to acquiring knowledge when they believe they already know it all? Educators and policymakers may also reconsider what it means to be educated. When external information is always at hand, are people’s limited cognitive resources best spent encoding information into internal memory or in combining and conducting the knowledge at their disposal? What do people need to know in order to harness the awesome cognitive power of the internet? Elevated confidence in personal knowledge may also shape decision-making—for example, by encouraging people to take financial risks (41), rely on their own intuitions when making medical decisions (42), and become more firmly entrenched in their views of science and politics (43, 44). In each of these domains, confidence in one’s knowledge is not necessarily a problem—but miscalibrated confidence very well could be. Finally, the tendency to accept the internet’s knowledge as one’s own adds yet another layer to the critical role that online information plays in the formation of personal beliefs. People are less likely to scrutinize information if they believe they knew it before or remembered it themselves (45, 46). In a world in which algorithmic search engines deliver different “truths” to different people (47), blurred boundaries between internal and external knowledge may prevent the detection of misinformation and exacerbate polarization.

Philosophers and cognitive scientists alike have long argued that human thought is collaborative, a product of the interplay between internal cognitive processes and external cognitive resources (1–6, 21, 32, 35–37, 48). The failure to accurately differentiate between personal knowledge and online search results, documented in the present research, may thus represent the breakdown of a boundary that was always more artificial than it seemed. At first blush, the consequences of merging human brains with the cloud mind of the internet may seem alarming, a recipe for both cognitive atrophy and intellectual hubris. But perhaps this union will give rise to an “Intermind”—a cognitive entity that is more and greater than the sum of its parts, one that is capable of thinking its way out of some of the messes we humans have created for ourselves. The path forward is uncertain, and the stakes are high. There is much work left to be done.

Materials and Methods

Experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Harvard University, the University of Colorado Boulder, and/or the University of Texas at Austin. All participants gave informed consent. Materials, data, syntax, and preregistration details are available at https://osf.io/qnfxc/. Additional methodological and sampling details and full analyses are provided in SI Appendix.

Experiment 1.

Participants (n = 543, Mage = 34.16 y, and 59.20% women) were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk and received a small monetary sum as compensation. Participants were randomly assigned to a Google condition (in which they were explicitly instructed to use Google) or one of two no Google conditions: an explicit no Google condition (in which they were explicitly instructed to refrain from using Google or other outside sources) or an implied no Google condition (in which they were given no explicit instructions). The two no Google conditions did not differ on any dependent measure (ps > 0.57; BFs < 0.13) and were collapsed for all analyses. Participants were then asked to answer 10 general knowledge questions (e.g., “What is a baby shark called?”). All questions in Experiments 1 through 6 were pretested to ensure that they were of moderate difficulty—for the average person, they were neither immediately known nor immediately known to be unknown. Participants were free to leave questions unanswered for any reason.

After completing the knowledge test, participants responded to the CSE scale: a self-report measure of one’s perceived ability to remember (e.g., “I have a better memory than most people”), process (e.g., “I am smart”), and access (e.g., “When I don’t know the answer to a question, I know where to find it”) information. Responses to the thinking and memory subscales were averaged to form a measure of attributions to internal knowledge (α = 0.911). Responses to the access subscale measured attributions to external knowledge (α = 0.828).

Participants were then randomly assigned to complete one or more measures of noncognitive self-esteem (e.g., Rosenberg global self-esteem; please see SI Appendix for all measures and analyses).

Experiment 2.

Participants (n = 287, Mage = 33.36 y, and 46.70% women) were recruited through Amazon mTurk and received a small monetary sum as compensation. As in Experiment 1, participants were randomly assigned to answer 10 general knowledge questions (e.g., “In what state was pop star Madonna born?”) either with Google or in one of two no Google conditions (explicit or implied). The two no Google conditions did not differ on any dependent measure (ps > 0.46; BFs < 0.27) and were collapsed for all analyses. Experiment 2 used a new set of knowledge questions in order to assess generalizability. Participants were required to answer every question.

After answering all 10 questions, half of the sample was randomly assigned to complete the same CSE measure used in Experiment 1. This feature of the experimental design allows testing for the replication of Experiment 1, while also ensuring that any effects on the focal dependent measure in Experiment 2—predicted knowledge performance when relying solely on internal memory—are not merely artifacts produced by asking participants to explicitly reflect and report on their own knowledge.

Finally, participants provided predictions of future performance. All participants were informed that they would take a second knowledge test, “similar in difficulty to the quiz you just took,” and would be “unable to use any outside sources for help” on this test. Participants were asked to indicate “how many questions (out of 10 total) you think you will answer correctly.”

Experiment 3.

Participants (n = 159, Mage = 37.56 y, and 62.89% women) were recruited through Amazon mTurk and received a small monetary sum as compensation. Based on the similarity between the two no Google conditions in Experiments 1 and 2, Experiment 3 and all subsequent experiments used a single no Google condition that mirrored the explicit no Google condition from previous experiments. Participants were first asked to answer 10 general knowledge questions either with or without Google (randomly assigned between participants); participants could leave questions unanswered for any reason. In Experiment 3, these questions were randomly sampled from a larger pool of general knowledge questions. All candidate questions were pretested to ensure that the search terms would yield a definitive result in Google’s “answer box.” Immediately after completing the test, all participants were provided with verbatim copies of the Google answers for every question they were asked. Participants then predicted how many questions they would answer correctly (out of 10) on a subsequent test of similar difficulty to be taken without access to any external resources. Finally, participants completed a second test of general knowledge; questions for this test were randomly sampled from the same pool of general knowledge questions, and no participant was asked the same question twice.

Experiment 4.

Participants (n = 129, Mage = 35.44 y, and 45.00% women) were recruited through Amazon mTurk and received a small monetary sum as compensation. Participants were randomly assigned to a no Google, no Google + false feedback, or Google condition. All participants first answered 10 general knowledge questions either with or without Google. Participants were required to provide an answer for every question. After answering these questions, participants in the no Google and Google conditions were provided with the correct answers and asked to report how many questions they had answered correctly; thus, these participants were fully aware that they either did not know much (MNoGoogle = 3.81 and SD = 2.58) or knew almost everything (albeit with the assistance of Google; MGoogle = 9.80 and SD = 0.48).

Participants in the no Google + false feedback condition were told that their answers were scored by an automated grading algorithm and that they had answered 8 out of 10 questions correctly. Under the guise of providing feedback on the technical performance of an automated grading algorithm, participants in this condition were asked to report “if you feel like the service made an error in your score.” This technical feedback was used to split participants in the false feedback condition into two subgroups for all further analyses: those that believed the feedback and those that did not. Participants who believed the false feedback did, on average, know more (M = 4.33 and SD = 2.12) than those who did not (M = 2.54 and SD = 1.74): t(65) = 3.51 and P = 0.001; BF10 = 35.80. This self-selection effect casts participants who believed the false feedback as a particularly rigorous comparison group for those in the Google condition; they not only believed they were knowledgeable, but in fact were more knowledgeable than average. All participants then completed the same CSE and performance prediction measures used in prior experiments.

Experiment 5.

Participants (n = 134, Mage = 31.94 y, and 50.00% women) were recruited through Amazon mTurk and received a small monetary sum as compensation. Participants were randomly assigned to a no Google, Google, or Google + write answers condition. All participants completed a 10-item general knowledge test and were required to provide an answer for every question. For participants in the Google and no Google conditions, the procedure was identical to these conditions in prior experiments. Participants in the Google + write answers condition were permitted to use Google during the knowledge test but were asked to first write down their own answers. After answering all 10 general knowledge questions, participants completed the same CSE and performance prediction measures used in prior experiments.

Experiment 6.

Participants (n = 157, Mage = 26.65 y, and 58.00% women) were recruited from the general population of the Boston and Cambridge area and received a fair wage monetary sum as compensation. The experiment was conducted by a team of trained research assistants in a psychology research laboratory at Harvard University. Each participant was assigned a private room and university computer to use for the duration of the experiment; research assistants welcomed and debriefed the participants but were not present in the testing room during the experimental session. Participants were randomly assigned to answer 10 general knowledge questions either on their own, with Google, or with a modified version of Google that delayed search results by 25 s. The length of the delay was determined by the amount of time taken to answer each question in a 130-item trivia pilot, M = 20.83 s. Participants were required to answer every question. After answering all 10 general knowledge questions, participants completed the same CSE and performance prediction measures used in prior experiments.

Experiment 7.

Participants (n = 352, Mage = 32.48 y, and 56.60% women) were recruited through Amazon mTurk and received a small monetary sum as compensation. Participants were randomly assigned to answer 10 general knowledge questions of either easy, moderate, or hard difficulty either with or without Google. Questions were pretested to ensure that most people immediately knew the answers to the easy questions (e.g., “Who is the current president of the United States?”) immediately knew that they did not know the answers to the hard questions (e.g., “What is the national flower of Australia?”), and believed that they might know the answers to the moderate questions (e.g., “What is the most abundant element in the universe?”). Participants were required to answer every question. After answering all 10 questions, participants completed the same CSE and performance prediction measures used in prior experiments.

Summary Analyses of Experiments 1 through 7.

Summary analyses were conducted on the combined data from all experiments. The estimated effects of Google search on CSE and performance predictions were derived from single-paper meta-analyses using the summary statistics from each experiment (31, 49). The conceptual relationships between self-reported internal attributions, self-reported external attributions, and performance predictions were computed using multilevel mediation analyses of the combined raw data that accounted for clustering by experiment.

Experiment 8.

Experiment 8 was preregistered on https://AsPredicted.org. Participants (n = 156, Mage = 36.22 y, and 57.70% women) were recruited through Prolific and received a fair wage monetary sum as compensation. Participants answered 50 general knowledge questions: 25 on their own and 25 using either Google or Wikipedia (randomly assigned between conditions). Trivia questions were presented in a random order, and each question was accompanied by explicit instructions regarding whether the question should be answered using only one’s own knowledge or by consulting the specified external knowledge source. Participants in the Wikipedia condition were provided a link to the relevant Wikipedia page for each external knowledge question, and participants in the Google condition were provided with links to Google. Participants were required to answer every question.

After an unrelated 5-min filler task, participants were asked to identify the source of the answers provided in the initial question-answering task. Participants were shown 70 general knowledge questions—all 50 from the first part of the study, plus 20 new questions—and asked to indicate whether the question had previously been answered using one’s own knowledge, had previously been answered using the internet, or was entirely new. Questions were presented one at a time in random order. Misattribution of online information to personal memory was operationalized as the count of questions that people answered using the internet, but subsequently reported answering using only their own knowledge.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this research were conducted as part of A.F.W.’s doctoral dissertation under the supervision of Daniel M. Wegner.

Footnotes

The author declares no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2105061118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Anonymized results for all experiments, with participant IDs removed, have been deposited in Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/qnfxc/) (50). All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Change History

November 23, 2021: Figure 2 and its caption have been updated. The text has been updated to correct metanalyses to meta-analyses.

References

- 1.Wegner D. M., “Transactive memory: A contemporary analysis of the group mind” in Theories of Group Behavior, Mullen B., Goethals G. R., Eds. (Springer, 1987), pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wegner D. M., Erber R., Raymond P., Transactive memory in close relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61, 923–929 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabb N., Fernbach P. M., Sloman S. A., Individual representation in a community of knowledge. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 891–902 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sloman S., Fernbach P., The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone (Penguin, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomasello M., Carpenter M., Shared intentionality. Dev. Sci. 10, 121–125 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark A., Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again (MIT Press, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacioppo J. T., Decety J., “An introduction to social neuroscience” in Oxford Handbook of Social Neuroscience, Cacioppo J. T., Decety J., Eds. (Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsh E. J., Rajaram S., The digital expansion of the mind: Implications of internet usage for memory and cognition. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 8, 1–14 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson T. O., Narens L., “Metamemory: A theoretical framework and new findings” in Psychology of Learning and Motivation, Bower G. H., Ed. (Academic Press, 1990), vol. 26, pp. 125–173. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaspersky Lab, “The rise and impact of digital amnesia: Why we need to protect what we no longer remember.” https://media.kasperskycontenthub.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/100/2017/03/10084613/Digital-Amnesia-Report.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2021.

- 11.Storm B. C., Stone S. M., Benjamin A. S., Using the internet to access information inflates future use of the internet to access other information. Memory 25, 717–723 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoelzle U., The Google gospel of speed. https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/_qs/documents/77/the-google-gospel-of-speed-urs-hoelzle_articles.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2021.

- 13.Anderson J. R., Retrieval of information from long-term memory. Science 220, 25–30 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis C. H., Anderson J. R., Interference with real world knowledge. Cognit. Psychol. 8, 311–335 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegner D. M., Sparrow B., “Authorship processing” in The Cognitive Neurosciences, Gazzaniga M. S., Ed. (Boston Review, 2004), pp. 1201–1209. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wegner D. M., Wheatley T., Apparent mental causation. Sources of the experience of will. Am. Psychol. 54, 480–492 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson M. K., Hashtroudi S., Lindsay D. S., Source monitoring. Psychol. Bull. 114, 3–28 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson M. K., Raye C. L., Reality monitoring. Psychol. Rev. 88, 67–85 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barber S. J., Rajaram S., Marsh E. J., Fact learning: How information accuracy, delay, and repeated testing change retention and retrieval experience. Memory 16, 934–946 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Google, “Google instant launch event” (video recording, 2010) https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=3867&v=i0eMHRxlJ2c&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 15 March 2021.

- 21.Aarts H., Dijksterhuis A., Habits as knowledge structures: Automaticity in goal-directed behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78, 53–63 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollan J., Hutchins E., Kirsh D., Distributed cognition: Toward a new foundation for human-computer interaction research. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 7, 174–196 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelley H. H., The processes of causal attribution. Am. Psychol. 28, 107–128 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chance Z., Norton M. I., Gino F., Ariely D., Temporal view of the costs and benefits of self-deception. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (suppl. 3), 15655–15659 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward A. F., “One with the cloud: Why people mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own,” Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (2013).

- 26.Fox C. R., Tversky A., Ambiguity aversion and comparative ignorance. Q. J. Econ. 110, 585–603 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox C. R., Weber M., Ambiguity aversion, comparative ignorance, and decision context. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 88, 476–498 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg M., Society and the Adolescent Self-Image (Princeton University Press, 1965). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleming J. S., Courtney B. E., The dimensionality of self-esteem: II. Hierarchical facet model for revised measurement scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46, 404–421 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dougherty M. R., Harbison J. I., Motivated to retrieve: How often are you willing to go back to the well when the well is dry? J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 33, 1108–1117 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loftus G. R., Wickens T. D., Effect of incentive on storage and retrieval processes. J. Exp. Psychol. 85, 141–147 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- 32.McShane B. B., Böckenholt U., Single-paper meta-analysis: Benefits for study summary, theory testing, and replicability. J. Consum. Res. 43, 1048–1063 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sparrow B., Liu J., Wegner D. M., Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science 333, 776–778 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu X., Luo L., Fleming S. M., A role for metamemory in cognitive offloading. Cognition 193, 104012 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishikawa T., Fujiwara H., Imai O., Okabe A., Wayfinding with a GPS-based mobile navigation system: A comparison with maps and direct experience. J. Environ. Psychol. 28, 74–82 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Austin J. R., Transactive memory in organizational groups: The effects of content, consensus, specialization, and accuracy on group performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 866–878 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keil F. C., Stein C., Webb L., Billings V. D., Rozenblit L., Discerning the division of cognitive labor: An emerging understanding of how knowledge is clustered in other minds. Cogn. Sci. 32, 259–300 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sloman S. A., Rabb N., Your understanding is my understanding: Evidence for a community of knowledge. Psychol. Sci. 27, 1451–1460 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher M., Goddu M. K., Keil F. C., Searching for explanations: How the internet inflates estimates of internal knowledge. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 144, 674–687 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koriat A., Monitoring one’s own knowledge during study: A cue-utilization approach to judgments of learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 126, 349–370 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wood S. L., Lynch J. G. Jr., Prior knowledge and complacency in new product learning. J. Consum. Res. 29, 416–426 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hadar L., Sood S., Fox C. R., Subjective knowledge in consumer financial decisions. J. Mark. Res. 50, 303–316 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall A. K., Bernhardt J. M., Dodd V., Older adults’ use of online and offline sources of health information and constructs of reliance and self-efficacy for medical decision making. J. Health Commun. 20, 751–758 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernbach P. M., Light N., Scott S. E., Inbar Y., Rozin P., Extreme opponents of genetically modified foods know the least but think they know the most. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 251–256 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernbach P. M., Rogers T., Fox C. R., Sloman S. A., Political extremism is supported by an illusion of understanding. Psychol. Sci. 24, 939–946 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia-Marques T., Mackie D. M., The feeling of familiarity as a regulator of persuasive processing. Soc. Cogn. 19, 9–34 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koriat A., Goldsmith M., Pansky A., Toward a psychology of memory accuracy. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 51, 481–537 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pariser E., The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think (Penguin, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clark A., Natural-Born Cyborgs: Minds, Technologies, and the Future of Human Intelligence (Oxford University Press, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ward A. F.,. Knowledge Misattributions from Online Search. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/qnfxc/. Deposited 5 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized results for all experiments, with participant IDs removed, have been deposited in Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/qnfxc/) (50). All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.