Abstract

Background

Indwelling urethral catheters are often used for bladder drainage in hospital. Urinary tract infection is the most common hospital‐acquired infection, and a common complication of urinary catheterisation. Pain, ease of use and quality of life are important to consider, as well as formal economic analysis. Suprapubic catheterisation can also result in bowel perforation and death.

Objectives

To determine the advantages and disadvantages of alternative routes of short‐term bladder catheterisation in adults in terms of infection, adverse events, replacement, duration of use, participant satisfaction and cost effectiveness. For the purpose of this review, we define 'short‐term' as intended duration of catheterisation for 14 days or less.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register, which contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE in process, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings (searched 26 February 2015), CINAHL (searched 27 January 2015) and the reference lists of relevant articles.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised and quasi‐randomised trials comparing different routes of catheterisation for short‐term use in hospitalised adults.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors extracted data and performed 'Risk of bias' assessment of the included trials. We sought clarification from the trialists if further information was required.

Main results

In this systematic review, we included 42 trials.

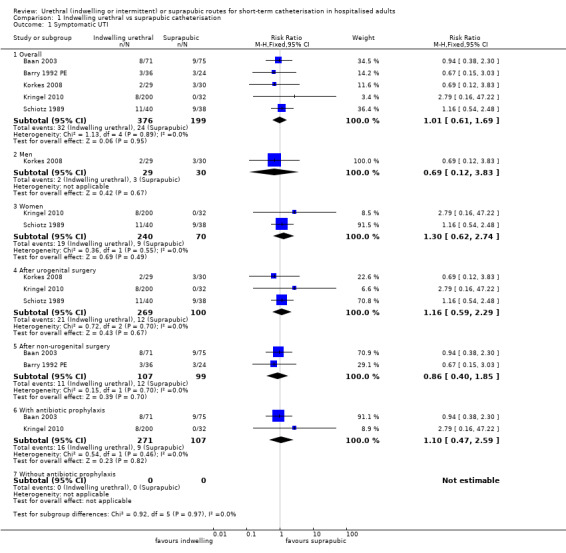

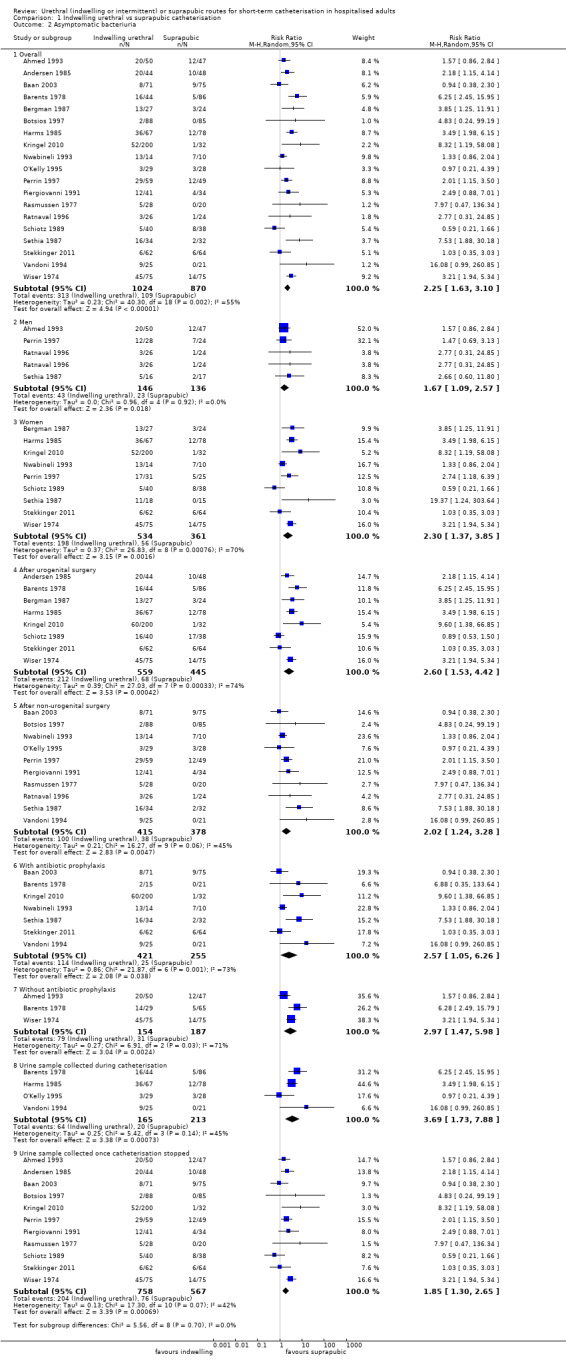

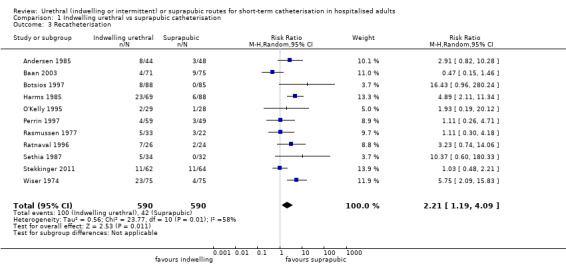

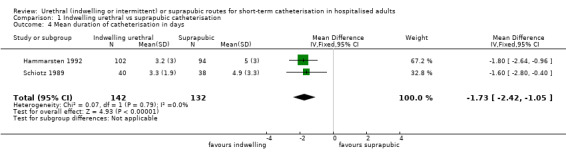

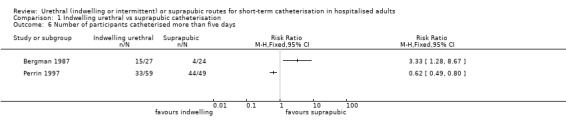

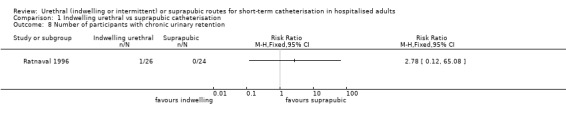

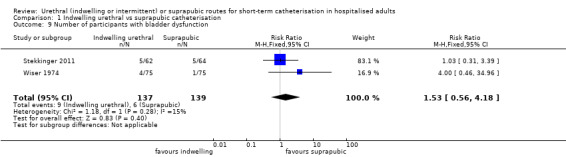

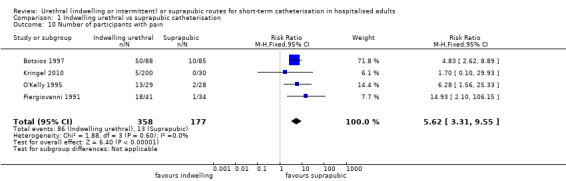

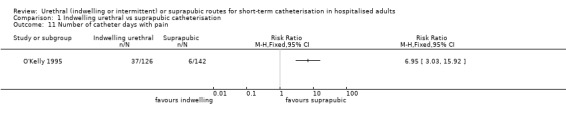

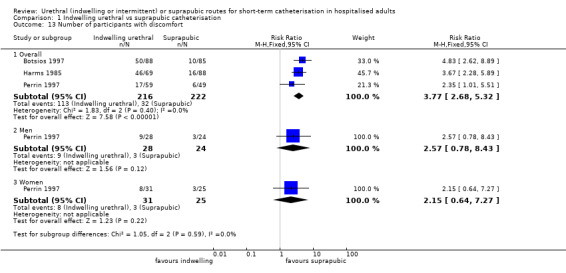

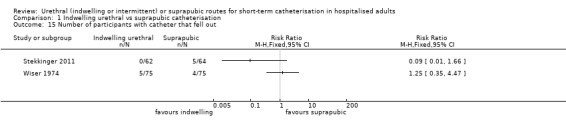

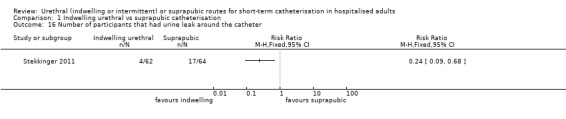

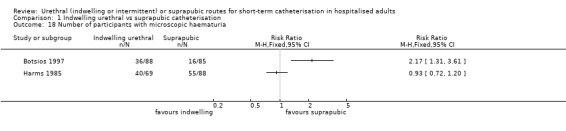

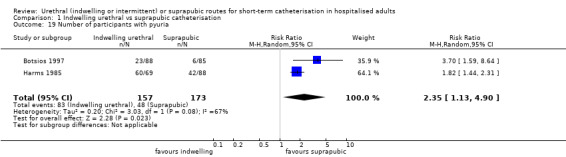

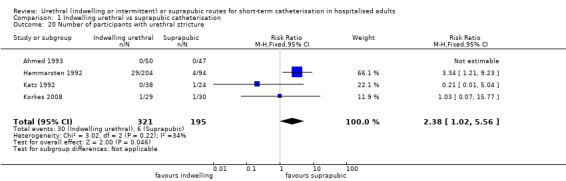

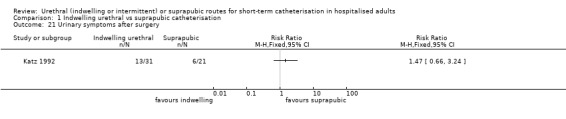

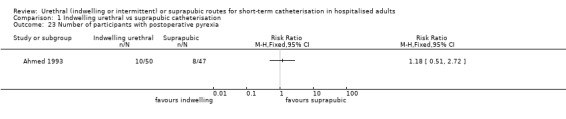

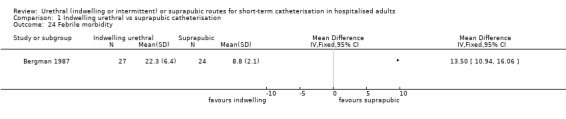

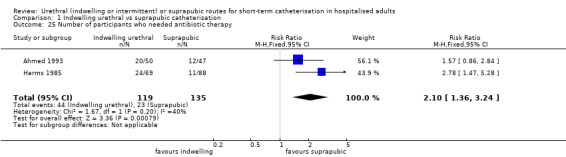

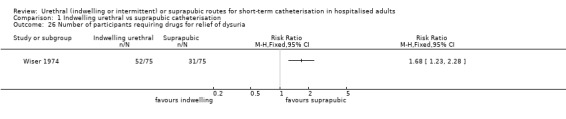

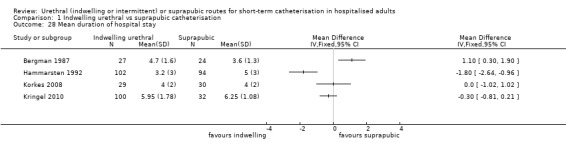

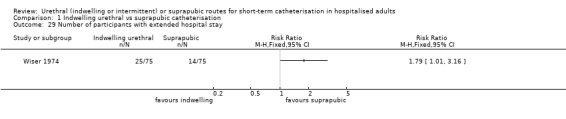

Twenty‐five trials compared indwelling urethral and suprapubic catheterisation. There was insufficient evidence for symptomatic urinary tract infection (risk ratio (RR) 1.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.61 to 1.69; 5 trials, 575 participants; very low‐quality evidence). Participants with indwelling catheters had more cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria (RR 2.25, 95% CI 1.63 to 3.10; 19 trials, 1894 participants; very low quality evidence) and more participants reported pain (RR 5.62, 95% CI 3.31 to 9.55; 4 trials, 535 participants; low‐quality evidence). Duration of catheterisation was shorter in the indwelling urethral catheter group (MD ‐1.73, 95% CI ‐2.42 to ‐1.05; 2 trials, 274 participants).

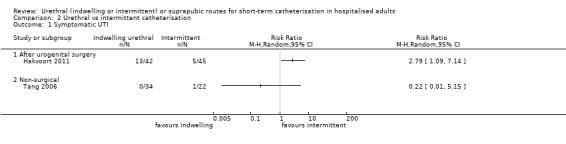

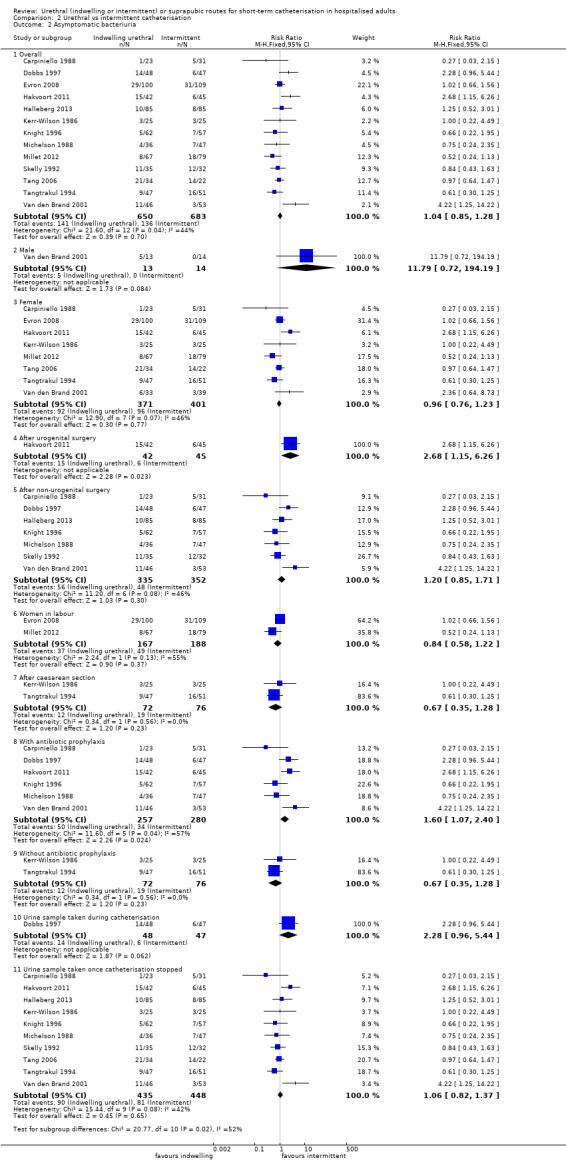

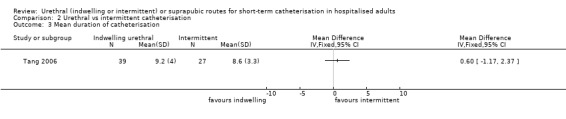

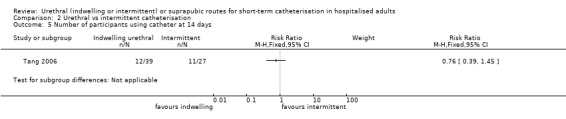

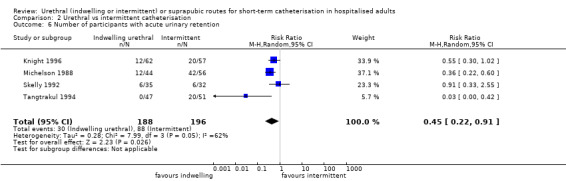

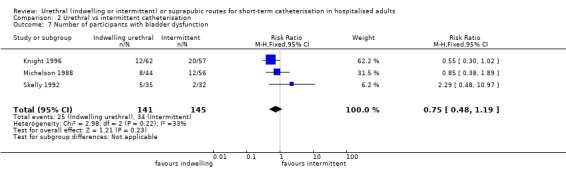

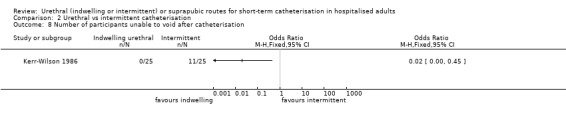

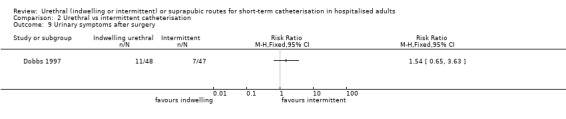

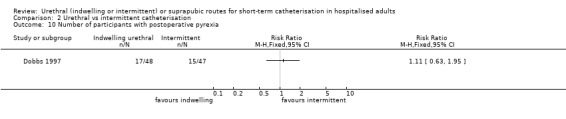

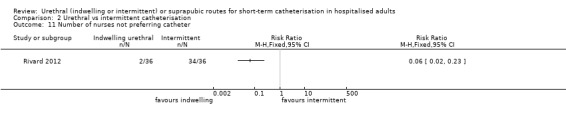

Fourteen trials compared indwelling urethral catheterisation with intermittent catheterisation. Two trials had data for symptomatic UTI which were suitable for meta‐analysis. Due to evidence of significant clinical and statistical heterogeneity, we did not pool the results, which were inconclusive and the quality of evidence was very low. The main source of heterogeneity was the reason for hospitalisation as Hakvoort and colleagues recruited participants undergoing urogenital surgery; whereas in the trial conducted by Tang and colleagues elderly women in geriatric rehabilitation ward were recruited. The evidence was also inconclusive for asymptomatic bacteriuria (RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.28; 13 trials, 1333 participants; very low quality evidence). Almost three times as many people developed acute urinary retention with the intermittent catheter (16% with urethral versus 45% with intermittent); RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.91; 4 trials, 384 participants.

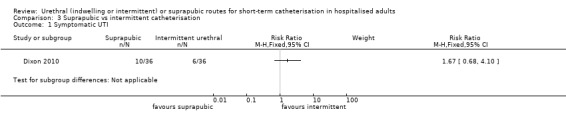

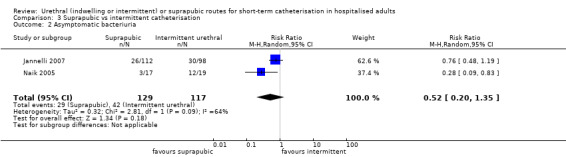

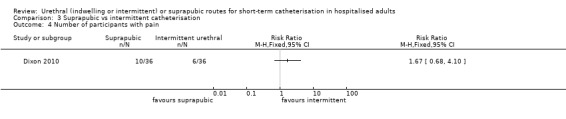

Three trials compared intermittent catheterisation with suprapubic catheterisation, with only female participants. The evidence was inconclusive for symptomatic urinary tract infection, asymptomatic bacteriuria, pain or cost.

None of the trials reported the following critical outcomes: quality of life; ease of use, and cost utility analysis.

Authors' conclusions

Suprapubic catheters reduced the number of participants with asymptomatic bacteriuria, recatheterisation and pain compared with indwelling urethral. The evidence for symptomatic urinary tract infection was inconclusive.

For indwelling versus intermittent urethral catheterisation, the evidence was inconclusive for symptomatic urinary tract infection and asymptomatic bacteriuria. No trials reported pain.

The evidence was inconclusive for suprapubic versus intermittent urethral catheterisation. Trials should use a standardised definition for symptomatic urinary tract infection. Further adequately‐powered trials comparing all catheters are required, particularly suprapubic and intermittent urethral catheterisation.

Plain language summary

Which route of short‐term bladder drainage is best for adults in hospital?

The evidence for this question is up‐to‐date as of 26 February 2015

Number of trials: 42

Number of participants: 4577

Key messages:

This Cochrane review found that there was not enough evidence to determine whether one route of bladder drainage was more likely to reduce urinary tract infection than another. The evidence suggests that participants with suprapubic catheters were less likely to have catheter‐associated pain compared with those with indwelling urethral catheters. The quality of evidence in this review was low, and many of the trials did not report important outcomes such as catheter‐associated quality of life and ease of use. The included trials reported few adverse effects, but it is not clear if this is because the adverse effects did not occur or were simply not reported. Because of the limited evidence, we need more high‐quality trials. It is important that these trials report symptomatic urinary tract infection, pain from using catheters, quality of life, adverse effects and ease of use.

Background: what routes of short‐term bladder drainage are there?

Urinary catheters are tubes that drain urine from the bladder. They are often used in people who are unable to go to the toilet easily during their hospital stay. About one in four hospital patients requires short‐term bladder drainage using a urinary catheter. Catheters can be used in different ways. The main routes of urinary catheterisation are:

1. Urethral : a drainage tube is inserted into the bladder via the urethra, and is either left in place (indwelling catheter), or removed after the bladder is emptied (intermittent catheter).

2. Suprapubic catheterisation: a drainage tube is inserted into the bladder through a small cut in the abdominal wall.

A common complication of short‐term bladder drainage is urinary tract infection. Infections have many serious implications for patients and healthcare providers. Insertion of a suprapubic catheter may also be associated with more risks than urethral routes, such as bleeding or damage to the bowel.

Key results

The Cochrane review looked at studies which made one of three comparisons:

1. Indwelling versus suprapubic catheterisation 2. Indwelling versus intermittent catheterisation 3. Suprapubic versus intermittent catheterisation

1. Twenty‐five trials (2622 participants) compared indwelling urethral and suprapubic catheterisation. There was not enough evidence from five trials to determine whether people had a lower risk of symptomatic urinary tract infection with indwelling urethral or suprapubic catheterisation. There was low quality evidence from four trials that people with indwelling urethral catheters were at greater risk of catheter‐associated pain compared with participants with suprapubic catheters. None of the twenty‐five trials reported ease of use, quality of life or economic outcomes.

2. Fourteen trials (1596 participants) compared indwelling and intermittent urethral catheterisation. There was very low quality evidence from two trials reporting on urinary tract infection, and the review could not determine which route of bladder drainage had a lower risk. None of the fourteen trials reported pain, ease of use, quality of life or economic outcomes.

3. Three trials (359 participants) compared suprapubic and intermittent urethral catheterisation. Only one trial reported on urinary tract infection. The evidence was inconclusive and of low quality. Only one trial had evidence on pain. Again, the evidence was inconclusive and the quality of the evidence was very low. None of the three trials reported ease of use, quality of life or economic outcomes.

Concluding messages

Although many trials have been conducted not enough have looked at important outcomes. Many questions are still unanswered about short‐term bladder drainage. Which route is the least likely to cause urinary tract infection? Is one route associated with more pain than the others? Is there a significant difference in cost or convenience for patients and hospitals between the three routes? Until these questions are answered with higher‐quality evidence, we need more and better trials.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Indwelling urinary catheters are commonly used for bladder drainage during hospital care. The most common complication is infection. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) account for about 20% of hospital‐acquired (nosocomial) infections (Smyth 2008), and about 80% of these are associated with urinary catheters. Such infections not only prolong hospital stay and are expensive to treat (Elvy 2009; Nasr 2010), but also cause unpleasant symptoms such as fever and chills in up to 30% of the patients. Patients with infection of the urinary tract can go on to develop bacteraemia (presence of bacteria within circulation). About 17% of hospital bacteraemia is due to catheter‐associated UTI (Gould 2009) . When used in patients who are acutely ill, the risk of a catheter‐associated infection may be higher and hence pose a greater threat to life.

Bacteria get into the catheterised bladder by direct inoculation at the time of catheter insertion and via the following routes: extraluminally by ascending from the urethral meatus along the catheter‐urethral interface, and intraluminally by reflux of the organisms into the catheter lumen (Tambyah 1999; Warren 2001). The normal mechanical wash‐out effect of the urinary stream is interrupted when there is a urinary catheter. The presence of a urinary catheter, plus other factors such as the formation of biofilm, allows bacteria to multiply quickly (Elvy 2009; Newman 2010; Trautner 2004).

There are various micro‐organisms that can cause catheter‐associated urinary tract infection. The most common of these is Escherichia coli, a gram‐negative coliform. Other common infective organisms include Candida spp, Enterococcus spp, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumonia and Enterobacter spp. This list, however, is not exhaustive, with other less common micro‐organisms also causing catheter‐associated urinary tract infection (Elvy 2009).

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines catheter‐associated UTI as a UTI in the presence of an indwelling catheter which has been in place for more than two calendar days on the day of UTI; or the catheter was in place on the day of the UTI or the previous day and then removed. The UTI criteria must be met on the day of catheter removal or the following day. The UTI CDC criteria must also be met, which include at least one of the following symptoms: fever, suprapubic tenderness, frequency, dysuria, costovertebral pain or tenderness. As well as signs and symptoms, a positive urine culture of 10⁵ colony‐forming units (CFU)/ml with no more than two species of micro‐organisms must be identified. CDC includes intermittent catheters but not suprapubic in its definition (CDC 2015).

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) published guidelines for diagnosing catheter‐associated UTIs, which include all three types of catheter: indwelling, intermittent and suprapubic catheters. It recommended that a diagnosis be made when symptoms and signs compatible with UTI were present, plus at least 10³ cfu/ml of one or more bacterial species in a single catheter urine specimen or in a midstream voided urine specimen from a patient whose catheter was removed in the previous 48 hours.

Signs and symptoms that are compatible with UTI include:

new onset or worsening fever

rigors

altered mental status

malaise, or lethargy with no other identified cause

flank pain

costovertebral angle tenderness

acute haematuria

pelvic discomfort

dysuria

urgent or frequent urination

suprapubic pain or tenderness (Hooton 2010).

In this review, we use the IDSA definition of catheter‐associated UTI as it includes indwelling urethral, intermittent urethral and suprapubic catheters in its definition. The CDC definition includes urethral catheters, but does not include suprapubic and we therefore did not use this definition.

The IDSA defines asymptomatic bacteriuria as the presence of at least 10⁵ cfu/ml of one or more bacterial species in a sample of urine in a patient with no symptoms of urinary tract infection (Hooton 2010).

Management of symptomatic UTI varies greatly. Some clinicians will treat patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria, some will use prophylactic antibiotics and others will only treat patients with symptomatic UTI. The European and Asian guidelines on Management and Prevention of Catheter‐Associated Urinary Tract Infections recommend that asymptomatic bacteriuria should not be treated with antibiotics, as the infection will not be eradicated or, if it is, it will return rapidly. They recommend that symptomatic infections in catheterised patients be treated with broad‐spectrum systemic antibiotics, as well as removal and replacement of the catheter (Tenke 2008).

Description of the intervention

In this review, we consider only short‐term urinary catheterisation in hospitalised adults. We define 'short‐term' as 14 days or less.

Indwelling urethral catheterisation

Indwelling urethral catheterisation is most commonly used, in both the short term and the long term. It involves the insertion of a catheter through the urethra into the bladder, although it is associated with various complications. The most common of these is UTI, which can have a heavy cost for both patient and healthcare provider. The first step in reducing UTIs and other complications is to avoid unnecessary catheterisation; the second is to remove the catheter as soon as possible. Indications for indwelling urethral catheterisation include acute urinary retention or bladder outlet obstruction, the need for precise urinary output monitoring, and in patients undergoing urological or gynaecological surgery who might be expected to be unable to micturate immediately after surgery (Gould 2009).

While the most common method of bladder drainage is indwelling urethral catheterisation, intermittent catheterisation and suprapubic catheterisation are alternative approaches. From a theoretical point of view, it is possible that either of these methods may be associated with a lower risk of UTI.

Suprapubic catheterisation

Suprapubic catheterisation involves insertion of a catheter into the bladder through an incision in the abdominal wall. Bacterial colonisation of the urethral tract is less likely because of the lower density of (gram‐negative) micro‐organisms on the abdominal skin than in the periurethral area. However, suprapubic catheterisation involves puncturing the bladder after inserting the catheter through the abdominal wall; the concern is unintended visceral or vascular injury. Contraindications for suprapubic catheterisation include bladder cancer, anticoagulation and antiplatelet treatment, abdominal wall sepsis and presence of subcutaneous vascular graft in the suprapubic region (Harrison 2011).

Intermittent catheterisation

Intermittent catheterisation involves inserting and removing a sterile urethral catheter using an aseptic technique. Micro‐organisms are less likely to gain entry into the bladder by tracking along the catheter wall because the catheter is no longer constantly present.

As with other catheters, intermittent catheterisation can be used diagnostically and therapeutically. Diagnostically, it can be used to obtain a sample of urine, or to assess urodynamics or urinary output. Therapeutically, it is indicated in patients who have problems with bladder voiding due to various reasons, such as spinal cord injury, non‐neurogenic bladder dysfunction or incomplete emptying due to intravesical obstruction. Intermittent catheterisation is contraindicated in patients with priapism, and urethral catheterisation generally is contraindicated in patients with suspected or confirmed urethral damage, or urethral cancer (Geng 2006).

How the intervention might work

Once a catheter is in place, the aim is to minimise the risk of infection. There are two accepted basic principles: keeping the catheter system closed, and removing the catheter when it is no longer needed. Antibiotic prophylaxis is controversial and is addressed in another Cochrane review (Lusardi 2013). Another possible strategy for reducing the risk of infection due to indwelling (i.e. urethral or suprapubic) catheters is to use different materials, such as catheters coated with an antibacterial substance. The effects of using different types of indwelling urethral catheters have been evaluated in another Cochrane review (Lam 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

The aim of this review is to assess the effectiveness of different routes of catheterisation (urethral (indwelling or intermittent) or suprapubic) for short‐term use in hospitalised adults, primarily focused on symptomatic urinary tract infection. Other important outcomes included adverse effects, the need for replacement, duration of use, patient satisfaction and cost effectiveness. For the purposes of this review, we define short term as intended duration of catheterisation for up to 14 days.

Objectives

To determine the advantages and disadvantages of alternative routes of short‐term bladder catheterisation in adults in terms of infection, adverse events, replacement, duration of use, participant satisfaction and cost effectiveness. For the purpose of this review, we define 'short‐term' as intended duration of catheterisation for 14 days or less.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised trials (quasi‐RCTs) comparing alternative routes of short‐term catheterisation in hospitalised adults. We define 'short‐term' as intended duration of catheterisation for 14 days or less. Where the intended duration of catheterisation was not stated, we used the reason for hospitalisation as an indicator of the approximate length of catheterisation.

Types of participants

We included studies of adults requiring short‐term urethral catheterisation in hospital for any reason such as urine monitoring, investigations, acute retention problems, and after surgery. These included those suffering from acute illness, urinary retention, perioperative, postoperative, during labour, and during or following surgery.

Types of interventions

The interventions considered were urethral (indwelling or intermittent) or suprapubic catheterisation.

We used the following definition for this review:

Indwelling catheterisation: The European Association of Urology (EAU) definition for indwelling catheterisation: indwelling catheterisation was defined by the passage of a catheter into the urinary bladder via the urethra using an inflatable balloon or other means to retain it in position (EAU 2014).

Intermittent catheterisation: The EAU definition for intermittent catheterisation: intermittent catheterisation, also known as in‐out catheterisation, was defined as emptying of the bladder via the urethra by a catheter that is removed after the procedure, mostly at regular intervals (EAU 2014).

Suprapubic catheterisation: The European Association of Urology Nurses (EAUN) definition of suprapubic catheterisation: suprapubic catheterisation was defined as the insertion of a catheter into the bladder via the anterior abdominal wall, using sutures or other means to retain it in position (Geng 2012).

We have not considered the following interventions for inclusion in this review:

catheterisation insertion techniques (e.g. clean, sterile, with or without antiseptic or antibiotic cream);

meatal care management techniques (e.g. routine hygiene, antiseptic or antibiotic cream);

types of drainage (e.g. continuous, clamp‐and‐release, pressure valves);

types of drainage container (e.g. flexible, rigid, disposable);

treatment of drainage bag (e.g. washouts, use of antiseptic or clean washing techniques, use of antiseptic solutions in the bag);

antibiotic prophylaxis;

type of catheter material (e.g. latex rubber, silicone latex, silicone);

type of catheter coating (e.g. silver alloy, antibiotic coated, electrified).

We made three specific comparisons: 1. indwelling urethral catheterisation versus suprapubic catheterisation; 2. indwelling urethral catheterisation versus intermittent catheterisation; 3. suprapubic catheterisation versus intermittent catheterisation.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Number of participants with symptomatic urinary tract infection (UTI)

We used the IDSA definition. If UTI was reported but symptoms were not described, then we reclassified the outcomes as asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Secondary outcomes

Participant‐reported:

number of participants with pain;

ease of use for participant;

participant discomfort;

participant satisfaction;

need to change catheters;

number of catheters used.

Clinician‐reported:

ease of use for practitioner;

length of time catheters used.

Complications/adverse effects:

asymptomatic bacteriuria, using IDSA definition (Hooton 2010) or as defined by trialists;

urethral stricture;

wound infection (for suprapubic catheters);

urgency/bladder spasms/detrusor overactivity;

other adverse effects of intervention (other than UTI).

Co‐interventions:

use of rescue antibiotics.

Health status/Quality of life:

quality of life (using SF‐36, Ware 1992) or other standard tool;

psychological outcome measures (e.g. HADS, Zigmond 1983).

Economic outcomes:

cost utility analysis (using EQ‐5D) or other standard tool of cost effectiveness or cost utility;

costs of intervention(s);

resource implications of differences in outcomes;

formal economic analysis (cost effectiveness, cost utility).

Other outcomes:

any other non‐prespecified outcomes judged to be important when performing the review.

Quality of evidence:

We assessed the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach. We organised a group discussion through the Urological Cancer Charity (UCAN) with participants who underwent urethral or suprapubic catheterisation, in order to identify outcomes which were important from their perspective. We identified five individuals (four men and one woman) who had undergone urethral catheterisation or suprapubic catheterisation. Most of the participants had both types of catheterisation during different stages of their treatment. The participants suggested that infections, pain and discomfort were certainly the most important outcomes from their point of view. They described the pain sensation of suprapubic catheterisation in a number of different ways, such as " very painful", "extremely painful" and "quite painful". They also stressed the impact of catheterisation on their quality of life and identified it as an important outcome. These results were similar to the focus group conducted by Omar 2013 for another Cochrane review of the types of indwelling urethral catheters for short‐term catheterisation in hospitalised adults (Lam 2014). We finally selected the following outcomes for 'Summary of findings' tables:

Number of participants with symptomatic UTI;

Asymptomatic bacteruria;

Number of participants with pain;

Ease of use for participant;

Quality of life (using SF‐36);

Cost utility analysis (using EQ‐5D).

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not impose language or other restrictions on any of the searches described below.

Electronic searches

This review drew on the search strategy developed for the Cochrane Incontinence Group. We identified relevant trials from the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register of trials. For more details of the search methods used to build the Specialised Register please see the Group's module in the Cochrane Library. The Register contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, and MEDLINE in process, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings. Most of the trials in the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register are also contained in CENTRAL. The date of the last search was: 26 February 2015.

We searched the Incontinence Group Specialised Register using the Group's own keyword system. The search terms used are given in Appendix 1.

For this update we also searched CINAHL (on EBSCO) covering 1 January 1981 to 27 January 2015 (searched on 27 January 2015). The search strategy used is given in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We also searched the reference lists of all relevant articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed all titles and abstracts of potentially eligible studies identified by the search. Where there was any possibility that the study might be included, we obtained the full‐text paper. We resolved any disagreements that could not be resolved by discussion by consultation with an independent third person.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted data independently and compared them. If the data in trials had not been fully reported, we sought clarification directly from the trialists. We entered extracted data into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 5.3). We processed the included trial data as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

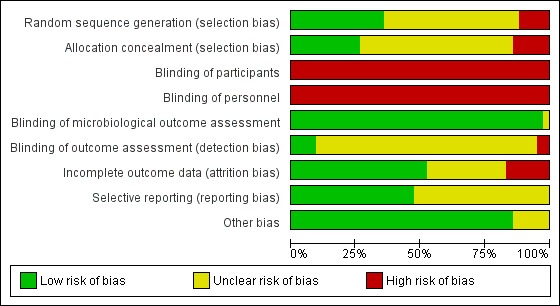

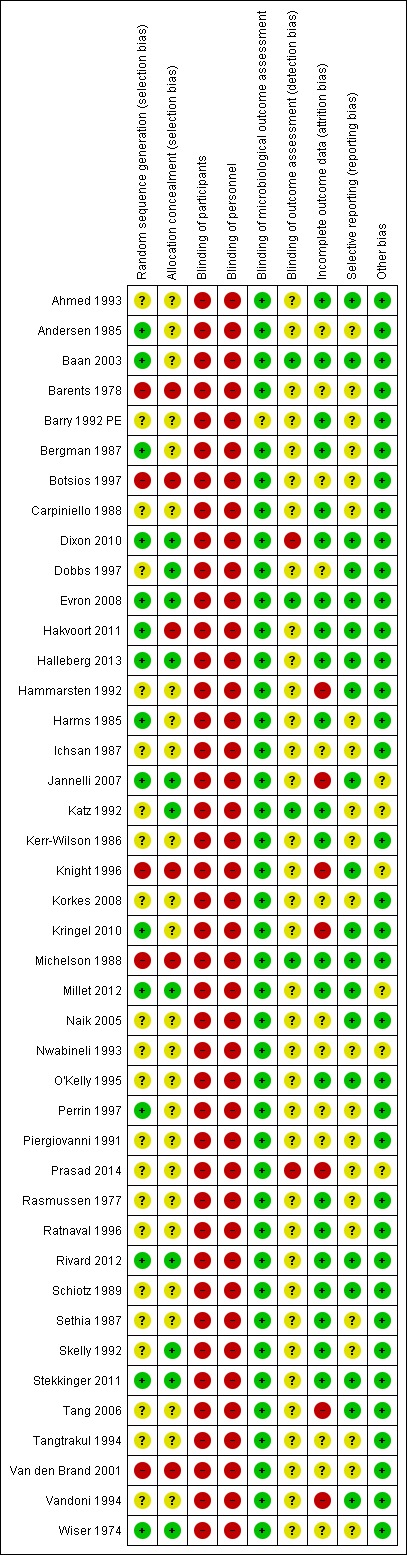

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool for judging the risk of bias of the included studies (Higgins 2011). We assessed the following areas for each of the studies:

random sequence generation (selection bias)

allocation concealment (selection bias)

blinding of participants (performance bias)

blinding of personnel (performance bias)

blinding of microbiological outcome assessment

blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

selective reporting (reporting bias)

other bias

Two of the review authors independently assessed the studies, and rated each as 'low risk', 'unclear risk' or 'high risk'.

Measures of treatment effect

For categorical outcomes, the numbers reporting an outcome were related to the numbers at risk in each group to derive a risk ratio (RR), and the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNT). For continuous variables, we used means and standard deviations to derive a mean difference (MD). As a general rule, we combined the outcome data using a fixed‐effect model to calculate pooled estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). However, we considered the use of a random‐effects model where there were concerns that heterogeneity might have been complicating an analysis. When appropriate, we undertook meta‐analysis.

Unit of analysis issues

In single parallel‐group designed trials, the primary analysis was by participant in the trial. In trials with a non‐standard design, such as multiple observations taken, cluster‐randomised trials and cross‐over trials, we conducted the analysis as directed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We used an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis where possible, meaning that participants were analysed based on the intervention group to which they were randomised, regardless of whether they actually received the intervention they were originally assigned. We tried to contact trialists from eight of the trials for which we required further information (Barry 1992 PE; Dixon 2010; Hakvoort 2011; Ichsan 1987; Korkes 2008; Kringel 2010; Naik 2005; Ratnaval 1996).

If we had noted a difference in dropout rates between the randomised groups, we would have performed sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered the likelihood of important clinical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis. We assessed heterogeneity visually using forest plots to assess overlap of 95% confidence intervals, the Chi² test for statistical heterogeneity and the I² statistical test (Higgins 2011). If the P value for the Chi² test was low (P < 0.10) or if the I² test was higher than 50%, we considered it statistically significant. Values of the I² test and the corresponding level of heterogeneity are detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. If there was significant heterogeneity, we used a random‐effects model.

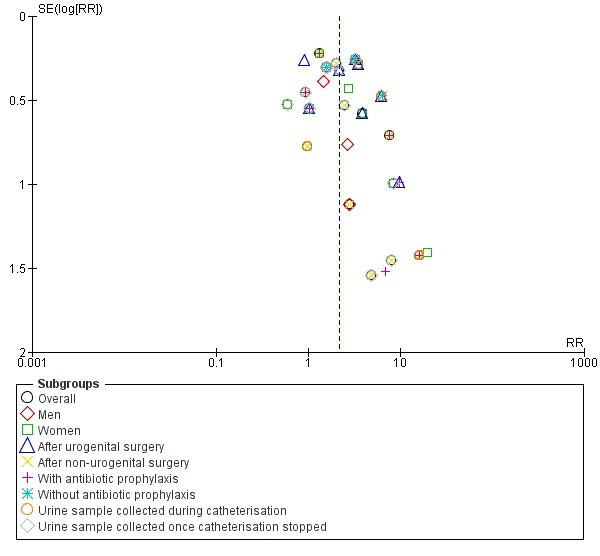

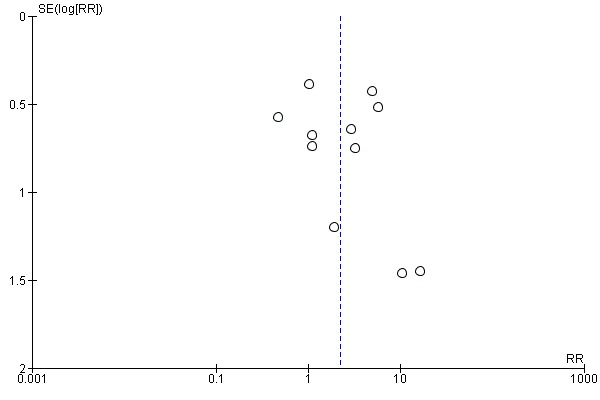

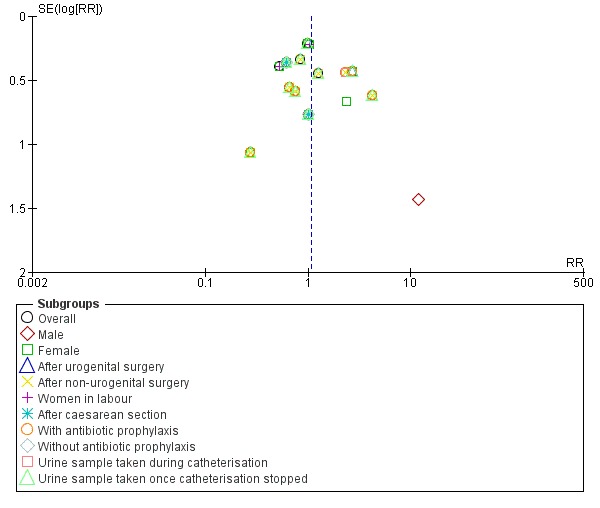

Assessment of reporting biases

In order to reduce the risk of reporting and publication bias, we searched multiple databases and other sources comprehensively. If the meta‐analysis included more than 10 trials, we used a funnel plot to assess reporting biases (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

We combined trials if we considered the interventions to be sufficiently similar, and used a fixed‐effect model to carry out meta‐analysis. If there was significant heterogeneity, we used a random‐effects analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses for:

different types of surgery (urogenital versus non‐urogenital surgery or other reason for catheterisation)

women in labour versus caesarean section

gender: men versus women

antibiotic prophylaxis used or not

timing of taking of urine sample

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses where there was significant heterogeneity, comparing different types of surgical intervention. We also performed sensitivity analysis on any trials that did not report their definition for symptomatic UTI and asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

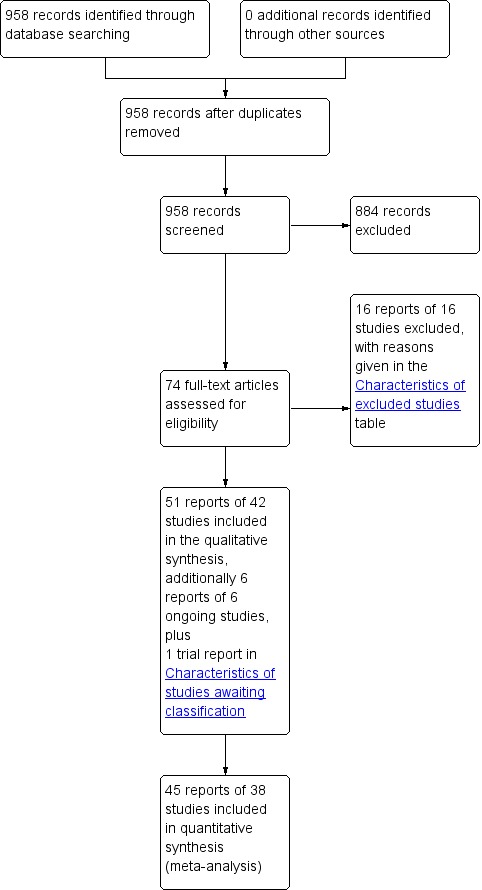

We screened 958 records found by the literature search for this review: we further assessed the full text of 74 of these articles for eligibility for inclusion. Fifty‐one reports of 42 studies were included in the review, and 16 reports of 16 studies were excluded from the review. There were six reports of six ongoing studies, details of which can be found in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table. We are still seeking one conference abstract (Kringel 2007) that appears to be a further report of the included study Kringel 2010, and has been detailed in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table pending its arrival. The flow of literature through the assessment process is shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram

New included trials

In this update, we re‐assessed 18 reports of trials that were excluded in the previous version of the review. Of these, we found 13 reports of 11 trials to be eligible for inclusion. Two were reports of an already‐included trial (Hakvoort 2011), and another two were reports of the same trial (Naik 2005). Overall, we included 11 additional reports of 10 new trials (Barry 1992 PE; Ichsan 1987; Katz 1992; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Michelson 1988; Naik 2005; Rasmussen 1977; Ratnaval 1996; Skelly 1992; Tangtrakul 1994).

We identified six reports after performing a new search. Of these, a further three new trials were eligible for inclusion (Dixon 2010; Halleberg 2013; Rivard 2012).

Included studies

The trials are described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies table.

We required more information for eight of the included trials. Of these, we were able to contact six: five by email (Dixon 2010; Hakvoort 2011; Korkes 2008; Kringel 2010; Naik 2005) and one by ResearchGate (Ratnaval 1996). We could not find contact details for two trials (Barry 1992 PE; Ichsan 1987). Only three of the six trialists we contacted responded (Dixon 2010; Korkes 2008; Ratnaval 1996).

Design

The review includes 40 randomised trials and two quasi‐randomised trials, as listed below:

RCTs (Ahmed 1993; Andersen 1985; Baan 2003; Barry 1992 PE; Bergman 1987; Botsios 1997; Carpiniello 1988; Dixon 2010; Dobbs 1997; Evron 2008; Hakvoort 2011; Halleberg 2013; Hammarsten 1992; Harms 1985; Ichsan 1987; Jannelli 2007; Katz 1992; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Knight 1996; Korkes 2008; Kringel 2010; Millet 2012; Naik 2005; Nwabineli 1993; O'Kelly 1995; Perrin 1997; Piergiovanni 1991; Prasad 2014; Rasmussen 1977; Ratnaval 1996; Rivard 2012; Schiotz 1989; Sethia 1987; Skelly 1992; Stekkinger 2011; Tang 2006; Tangtrakul 1994; Van den Brand 2001; Vandoni 1994; Wiser 1974)

quasi‐RCTs (Barents 1978; Michelson 1988)

Sample sizes

The number randomised in the included trials ranged from 24 participants (Nwabineli 1993) to 344 participants (Hammarsten 1992). In total, 4577 participants were randomised in the 42 trials.

25 trials including 2622 participants compared indwelling urethral and suprapubic catheterisation

14 trials including 1596 participants compared indwelling urethral and intermittent urethral catheterisation

3 trials including 359 participants compared suprapubic and intermittent urethral catheterisation

Participants

We included 42 trials with 4577 participants, who received one route of catheterisation.

Reason for hospitalisation

Thirty‐seven trials had participants hospitalised for a surgical procedure. They were as follows:

Urogenital surgery (Ahmed 1993; Andersen 1985; Barents 1978; Bergman 1987; Dixon 2010; Hakvoort 2011; Hammarsten 1992; Harms 1985; Jannelli 2007; Korkes 2008; Kringel 2010; Prasad 2014; Schiotz 1989; Stekkinger 2011; Wiser 1974)

Abdominal surgery (Baan 2003; Barry 1992 PE; Botsios 1997; Dobbs 1997; Naik 2005; Nwabineli 1993; O'Kelly 1995; Perrin 1997; Rasmussen 1977; Ratnaval 1996; Sethia 1987)

Orthopaedic surgery (Carpiniello 1988; Halleberg 2013; Knight 1996; Michelson 1988; Skelly 1992; Van den Brand 2001)

Caesarean section (Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Tangtrakul 1994)

General surgery (Piergiovanni 1991; Vandoni 1994)

Cardiac surgery (Katz 1992)

The remaining five trials included participants hospitalised for non‐surgical reasons.

Women in labour: three trials (Evron 2008; Millet 2012; Rivard 2012)

Acute urinary retention: one trial (Ichsan 1987)

Elderly women admitted to a geriatric rehabilitation ward for persistent abnormal post‐void residual volumes: one trial (Tang 2006)

We describe reasons for hospitalisation, reason for catheterisation and type of surgery in more detail in Table 4.

1. Types of participants.

| Study ID | Reason for Hospitalisation | Reason for catheterisation | Type of surgery | Gender |

| Ahmed 1993 | Urogenital surgery | Acute urinary retention | TURP for men who present with AUR | Men only |

| Andersen 1985 | Urogenital surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | Colposuspension or vaginal repair for SUI and/or genital descensus | Women only |

| Baan 2003 | Abdominal surgery | Surgery‐indicated catheterisation | Elective laparotomy | Men and women |

| Barents 1978 | Urogenital surgery | Unclear | Vaginal surgery | Women only |

| Barry 1992 PE | Abdominal surgery | Major abdominal surgery | Elective abdominal surgery | Men and women |

| Bergman 1987 | Urogenital surgery | Surgery‐indicated catheterisation | Vaginal urethropexy (+ hysterectomy) in women with SUI | Women only |

| Botsios 1997 | Abdominal surgery | Surgery‐indicated catheterisation | Elective abdominal surgery of long length | Men and women |

| Carpiniello 1988 | Orthopaedic surgery | Prevent postoperative urinary complications | Total joint replacement | Women only |

| Dixon 2010 | Urogenital surgery | Prevent postoperative urinary retention | Surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and/or SUI | Women only |

| Dobbs 1997 | Abdominal surgery | Prevent postoperative urinary retention | Total hysterectomy for non‐malignant reasons under general anaesthetic | Women only |

| Evron 2008 | Labour | Prevent intrapartum urinary retention | Labour with epidural | Women only |

| Hakvoort 2011 | Urogenital surgery | Abnormal PVR following vaginal prolapse surgery | Vaginal prolapse surgery | Women only |

| Halleberg 2013 | Orthopaedic surgery | Prevent postoperative urinary retention | Hip fracture or hip replacement surgery | Men and women |

| Hammarsten 1992 | Urogenital surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | TURP | Men only |

| Harms 1985 | Urogenital surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | Vaginal hysterectomy with front plastic | Women only |

| Ichsan 1987 | AUR | AUR | None | Men and women |

| Jannelli 2007 | Urogenital surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | Surgery for SUI or anterior vaginal wall prolapse | Women only |

| Katz 1992 | Cardiac surgery | Major cardiac surgery | Coronary artery bypass graft | Men only |

| Kerr‐Wilson 1986 | Caesarean section | Avoid trauma to the bladder during surgery and to ensure unobstructed access to the lower uterine segment | Elective caesarean under epidural anaesthesia | Women only |

| Knight 1996 | Orthopaedic surgery | Prevent postoperative urinary retention | Primary total hip or knee arthroplasty | Men and Women |

| Korkes 2008 | Urogenital surgery | Prevent postoperative urinary retention | Open prostatectomy for BPH | Men only |

| Kringel 2010 | Urogenital surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | Anterior colporrhaphy plus optional additional procedure (i.e. hysterectomy) | Women only |

| Michelson 1988 | Orthopaedic surgery | Prevent postoperative urinary complications | Total joint replacement | Men and women |

| Millet 2012 | Labour | Prevent intra‐ and postpartum urinary retention | Labour with epidural | Women only |

| Naik 2005 | Abdominal surgery | Postoperative bladder dysfunction | Radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer | Women only |

| Nwabineli 1993 | Abdominal surgery | Prevent postoperative urinary complications (retention and inability to void) | Stage IB or IIA cervical cancer with view for radical hysterectomy | Women only |

| O'Kelly 1995 | Abdominal surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | Abdominal surgery with full‐length abdominal incision | Men and Women |

| Perrin 1997 | Abdominal surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | Rectal surgery | Men and women |

| Piergiovanni 1991 | General surgery | Bladder drainage for non‐urological reasons (perioperative, urinary retention, prostatic hypertrophy, incontinence, nursing) | Information not given | Men and women |

| Prasad 2014 | Urogenital surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | Robot‐assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy for newly diagnosed prostate cancer | Men only |

| Rasmussen 1977 | Abdominal surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | Abdomino‐perineal resection or low anterior resection for rectal cancer | Men and women |

| Ratnaval 1996 | Abdominal surgery | Monitoring of urine during surgery | Pelvic colorectal surgery | Men only |

| Rivard 2012 | Labour | Indicated during birth | Labour with epidural | Women only |

| Schiotz 1989 | Urogenital surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | Vaginal plastic surgery | Women only |

| Sethia 1987 | General surgery | Monitor urine output postoperatively | Extensive pelvic dissection with or without an anastomosis. | Men and Women |

| Skelly 1992 | Orthopaedic surgery | Postoperative urinary retention | Surgical repair of hip fracture | Men and women |

| Stekkinger 2011 | Urogenital surgery | Prevent postoperative urinary retention | Anterior colporrhaphy ± hysterectomy ± PRS for pelvic prolapse | Women only |

| Tang 2006 | Persistently abnormal PVR | Persistently abnormal PVR in elderly patients | None | Women only |

| Tangtrakul 1994 | Caesarean section | Avoid bladder injury during surgery | Caesarean section | Women only |

| Van den Brand 2001 | Orthopaedic surgery | Prevent postoperative urinary retention | Primary total hip or knee arthroplasty | Men and Women |

| Vandoni 1994 | General surgery | Monitoring or nursing reasons in surgical patients | Information not given | Men and women |

| Wiser 1974 | Urogenital surgery | Postoperative bladder drainage | Vaginal hysterectomy and anterior‐posterior repair | Women only |

AUR: acute urinary retention BPH: benign prostatic hyperplasia PVR: post‐void residual SUI: stress urinary incontinence TURP: trans‐urethral resection of prostate

Gender (Men/Women)

Six trials enrolled only men (Ahmed 1993; Hammarsten 1992; Katz 1992; Korkes 2008; Prasad 2014; Ratnaval 1996).

21 trials enrolled only women (Andersen 1985; Barents 1978; Bergman 1987; Carpiniello 1988; Dixon 2010; Dobbs 1997; Evron 2008; Hakvoort 2011; Harms 1985; Jannelli 2007; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Kringel 2010; Millet 2012; Naik 2005; Nwabineli 1993; Rivard 2012; Schiotz 1989; Stekkinger 2011; Tang 2006; Tangtrakul 1994; Wiser 1974).

Fifteen trials enrolled both men and women (Baan 2003; Barry 1992 PE; Botsios 1997; Halleberg 2013; Ichsan 1987; Knight 1996; Michelson 1988; O'Kelly 1995; Perrin 1997; Piergiovanni 1991; Rasmussen 1977; Sethia 1987; Skelly 1992; Van den Brand 2001; Vandoni 1994).

Age

There was a wide range of ages in the included studies. Five trials did not report the age of participants (Barents 1978; Barry 1992 PE; Harms 1985; Ichsan 1987; Wiser 1974). In trials that did report the age of participants it was reported for each study arm, overall, or both:

< 30 years old: five trials. These trials were all in pregnant women. (Evron 2008; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Millet 2012; Rivard 2012; Tangtrakul 1994);

40 to 60 years old: seven trials (Bergman 1987; Dobbs 1997; Jannelli 2007; Katz 1992; Naik 2005; Nwabineli 1993; Prasad 2014);

60 to 75 years old: 22 trials (Ahmed 1993; Andersen 1985; Baan 2003; Botsios 1997; Carpiniello 1988; Dixon 2010; Hakvoort 2011; Halleberg 2013; Hammarsten 1992; Knight 1996; Korkes 2008; Kringel 2010; Michelson 1988; O'Kelly 1995; Perrin 1997; Piergiovanni 1991; Ratnaval 1996; Schiotz 1989; Sethia 1987; Stekkinger 2011; Van den Brand 2001; Vandoni 1994);

≥ 75 years old: two trials (Skelly 1992; Tang 2006).

One trial (Rasmussen 1977) reported the number of participants who were under 70 years old and those aged 70 years or older in each arm. In the indwelling group, eight participants were less than 70 years old and seven were 70 years or older. In the suprapubic group, 25 participants were less than 70 years old and 15 were 70 years or older .

We describe the age of participants in detail in Table 5.

2. Age of participants.

| Study ID | Intervention A | Intervention B | Age (A), years | Age (B), years | Age (overall), years |

| Ahmed 1993 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 71.6 (mean) | 71.9 (mean) | Not reported |

| Andersen 1985 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | Not reported | Not reported | 61 (34 ‐ 86) (median, range) |

| Baan 2003 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 59.8 (26 ‐ 81) (mean, range) | 60.4 (37 ‐ 87) (mean, range) | Not reported |

| Barents 1978 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Barry 1992 PE | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Bergman 1987 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | Not reported | Not reported | 53 (35 ‐ 68) (mean, range) |

| Botsios 1997 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 64.3 (1.2) (mean, SD) | 63.8 (1.4) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Carpiniello 1988 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 70 (8.6) (mean, SD) | 73 (6.6) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Dixon 2010 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 66 (median) | 57 (median) | Not reported |

| Dobbs 1997 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 45 (mean) | 42.6 (mean) | Not reported |

| Evron 2008 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 26 (4) (mean, SD) | 25 (4) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Hakvoort 2011 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 61 (10) (mean, SD) | 60 (12) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Halleberg 2013 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 72.1 (12.7) (mean, SD) | 71.9 (12.1) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Hammarsten 1992 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 73 (7) (mean, SE) | 71 (7) (mean, SE) | Not reported |

| Harms 1985 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ichsan 1987 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Jannelli 2007 | Suprapubic | Intermittent urethral | 54.6 (13.7) (mean, SD) | 55.0 (10.5) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Katz 1992 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 60 (9) (mean, SD) | 55 (8) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Kerr‐Wilson 1986 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 29.5 (0.97) (mean, SD) | 27.0 (1.03) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Knight 1996 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | Not reported | Not reported | 66 (35‐86) (mean, SD) |

| Korkes 2008 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 71.4 (8.0) (52‐84) (mean, SD, range) | 74.1 (6.8) (61 ‐ 91) (mean, SD, range) | Not reported |

| Kringel 2010 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 63.5 (11.3) (mean, SD) | 61.1 (9.92) (mean, SD) | 64.2 (10.6) (mean, SD) |

| Michelson 1988 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 65.7 (mean) | 61.7 (mean) | 63.5 (mean) |

| Millet 2012 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 27.1 (5.6) (mean, SD) | 28.2 (5.8) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Naik 2005 | Suprapubic | Intermittent urethral | Not reported | Not reported | 45 (20‐78) (median, range) |

| Nwabineli 1993 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 45 (mean) | 42 (mean) | Not reported |

| O'Kelly 1995 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 65 (42‐81) (median, range) | 68 (35‐79) (median, range) | Not reported |

| Perrin 1997 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 62 (mean) | 64 (mean) | Not reported |

| Piergiovanni 1991 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 63 (mean) | 64 (mean) | Not reported |

| Prasad 2014 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 57.6 (8.6) (mean, SD) | 60.0 (6.4) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Rasmussen 1977 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | < 70 years old: 8 participants ≥ 70 years old: 7 participants | < 70 years old: 25 participants ≥ 70 years old: 15 participants | Not reported |

| Ratnaval 1996 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 63 (42‐80) (median, range) | 64 (32‐81) (median, range) | 66 (32 ‐ 81) (median, range) |

| Rivard 2012 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 27.6 (mean) | 28.7 (mean) | Not reported |

| Schiotz 1989 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 63.8 (9.1) (mean, SD) | 63.6 (8.5) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Sethia 1987 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 62.3 (mean) | 63.7 (years) | Not reported |

| Skelly 1992 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 78 (8.2) (mean, SD) | 78 (8.6) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Stekkinger 2011 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 61.7 (11.2) (mean, SD) | 62.2 (11.5) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Tang 2006 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 81.4 (8.9) (mean, SD) | 80.0 (6.8) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Tangtrakul 1994 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 30.4 (4.6) (mean, SD) | 29.1 (4.5) (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Van den Brand 2001 | Indwelling urethral | Intermittent urethral | 68.6 (8.8) (42 ‐ 85) (mean, SD, range) | 68.2 (9.0) (36 ‐ 84) (mean, SD, range) | Not reported |

| Vandoni 1994 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | 66.4 (mean) | 66 (mean) | Not reported |

| Wiser 1974 | Indwelling urethral | Suprapubic | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

SD: standard deviation

Participants who received antibiotics during hospitalisation

There was variation between trials in participants receiving antibiotic therapy, which is likely to be linked to the reason for hospitalisation. Fifteen trials did not report whether antibiotic prophylaxis was used or not (Andersen 1985; Barry 1992 PE; Botsios 1997; Dixon 2010; Evron 2008; Harms 1985; Katz 1992; Korkes 2008; O'Kelly 1995; Prasad 2014; Ratnaval 1996; Rivard 2012; Schiotz 1989; Skelly 1992;Tang 2006). Antibiotic prophylaxis use was as follows in the remaining trials:

Participants received antibiotic therapy: 18 trials (Baan 2003; Bergman 1987; Carpiniello 1988; Dobbs 1997; Hakvoort 2011; Hammarsten 1992; Jannelli 2007; Knight 1996; Kringel 2010; Michelson 1988; Naik 2005; Nwabineli 1993; Perrin 1997; Rasmussen 1977; Sethia 1987; Stekkinger 2011; Van den Brand 2001; Vandoni 1994);

Participants did not receive antibiotics during hospitalisation: five trials (Ahmed 1993; Ichsan 1987; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Tangtrakul 1994; Wiser 1974);

Some participants received antibiotic therapy and others did not: three trials. It was not reported which participants received antibiotic (Halleberg 2013; Millet 2012; Piergiovanni 1991);

Participants stratified according to antibiotic use: one trial (Barents 1978).

We give more information about antibiotic therapy during the trials in Table 6.

3. Use of antibiotic prophylaxis.

| Study ID | Comparison | With or without antibiotic prophylaxis | Details |

| Ahmed 1993 | 1 | Without | Routine prophylactic antibiotics were not used in either group |

| Andersen 1985 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Baan 2003 | 1 | With | Prophylactic antibiotics were used in all participants perioperatively for 24 hours |

| Barents 1978 | 1 | Both | Results were stratified according to antibiotic prophylaxis or not. It was not reported whether the prophylactic protocol was the same for all participants |

| Barry 1992 PE | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Bergman 1987 | 1 | With | All participants received the same antibiotic prophylaxis (cefoxitin 2 g intramuscularly 1 hour before and 6 and 12 hours after surgery) |

| Botsios 1997 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Carpiniello 1988 | 2 | With | Prophylactic cefazolin sodium (Ancef) or clindamycin (Cleocin) until 3rd postoperative day |

| Dixon 2010 | 3 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Dobbs 1997 | 2 | With | Participants received Augmentin® at the induction of general anaesthetic and again 6 hours after surgery (1.2 g); it was not explicitly stated whether other antibiotics except prophylaxis were administered pre‐ or postoperatively |

| Evron 2008 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported if antibiotic prophylaxis used in study but women on antibiotics were excluded |

| Hakvoort 2011 | 2 | With | All participants received prophylactic antibiotics during surgery |

| Halleberg 2013 | 2 | Both | During surgery: cefuroxime, clindamycine, cloxacillin, No antibiotic prophylaxis |

| Hammarsten 1992 | 1 | With | Participants received pivmecillinam and pivampicillin if had no bacteriuria at time of operation as prophylaxis, or if had bacteriuria at time of operation was used as treatment. First dose was given 1 hour preoperatively, and last dose on the day the catheter was removed |

| Harms 1985 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ichsan 1987 | 1 | Without | None of the participants who completed the trial received antibiotics |

| Jannelli 2007 | 3 | With | All participants received appropriate preoperative antibiotics |

| Katz 1992 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Kerr‐Wilson 1986 | 2 | Without | Antibiotic prophylaxis was not used |

| Knight 1996 | 2 | With | All participants received routine antibiotic prophylaxis (cefazolin) every 8 hours for 48 hours; it was not explicitly stated whether other antibiotics except prophylaxis were administered pre‐ or postoperatively |

| Korkes 2008 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Kringel 2010 | 1 | With | All participants received 2 g cefotiam i.v. before starting surgery as antibiotics prophylaxis |

| Michelson 1988 | 2 | With | Perioperative prophylactic antibiotic therapy (cephalosporin with or without gentamicin) was given to all participants. Participants requiring secondary Foley catheter received antibiotics while device was in place |

| Millet 2012 | 2 | Both | Some women received antibiotics during labour, some received antibiotics in postpartum period and some received no antibiotics |

| Naik 2005 | 3 | With | All women received a single dose of intraoperative antibiotics. Prophylactic antibiotics were not given at any other time in the study. Antibiotics were prescribed when clinically indicated, i.e. positive urine sample or positive SPC site swab |

| Nwabineli 1993 | 1 | With | All participants received the same antibiotic prophylaxis (a single dose of 5 g of methyl penicillin). Antibiotics were not administered routinely in the postoperative period |

| O'Kelly 1995 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Perrin 1997 | 1 | With | All participants received a single dose of tinidazole and/or ticarcillin |

| Piergiovanni 1991 | 1 | Both | Some participants received antibiotics (65% in each group) |

| Prasad 2014 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Rasmussen 1977 | 1 | With | Neomycin sulphate + bacitracin were given, 1.5 g every 6 hours 3 days before operation |

| Ratnaval 1996 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Rivard 2012 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Schiotz 1989 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Sethia 1987 | 1 | With | All participants received the same antibiotic prophylaxis (single dose of metronidazole 500 mg and cephadrine 1 g intravenously on induction of anaesthesia). These antibiotics were continued for 48 hours in high‐risk participants and 5 days when sepsis was already present |

| Skelly 1992 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Stekkinger 2011 | 1 | With | All women received a single dose of prophylactic antibiotics (cefazolin 1 g and metronidazole 500 mg) during surgery |

| Tang 2006 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Tangtrakul 1994 | 2 | Without | No participants received prophylactic antimicrobial drug |

| Van den Brand 2001 | 2 | With | 1 dose of cefazolin, 1 g, intravenously immediately before surgery; no postoperative antibiotics were used |

| Vandoni 1994 | 1 | With | Identical single‐dose pre‐operative antibiotic prophylaxis was routinely applied (2 g of cefacetrile and 500 mg of metronidazole) |

| Wiser 1974 | 1 | Without | Did not use antibiotic prophylaxis |

SPC: suprapubic catheter

Interventions

The trials compared a number of different routes of catheterisation:

Indwelling: 39 trials (Ahmed 1993; Andersen 1985; Baan 2003; Barents 1978; Barry 1992 PE; Bergman 1987; Botsios 1997; Carpiniello 1988; Dobbs 1997; Evron 2008; Hakvoort 2011; Halleberg 2013; Hammarsten 1992; Harms 1985; Ichsan 1987; Katz 1992; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Knight 1996; Korkes 2008; Kringel 2010; Michelson 1988; Millet 2012; Nwabineli 1993; O'Kelly 1995; Perrin 1997; Piergiovanni 1991; Prasad 2014; Rasmussen 1977; Ratnaval 1996; Rivard 2012; Schiotz 1989; Sethia 1987; Skelly 1992; Stekkinger 2011; Tang 2006; Tangtrakul 1994; Van den Brand 2001; Vandoni 1994; Wiser 1974);

Suprapubic: 28 trials (Ahmed 1993; Andersen 1985; Baan 2003; Barents 1978; Barry 1992 PE; Bergman 1987; Botsios 1997; Dixon 2010; Hammarsten 1992; Harms 1985; Ichsan 1987; Jannelli 2007; Katz 1992; Korkes 2008; Kringel 2010; Naik 2005; Nwabineli 1993; O'Kelly 1995; Perrin 1997; Piergiovanni 1991; Prasad 2014; Rasmussen 1977; Ratnaval 1996; Schiotz 1989; Sethia 1987; Stekkinger 2011; Vandoni 1994; Wiser 1974);

Intermittent: 17 trials (Carpiniello 1988; Dixon 2010; Dobbs 1997; Evron 2008; Hakvoort 2011; Halleberg 2013; Jannelli 2007; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Knight 1996; Michelson 1988; Millet 2012; Naik 2005; Rivard 2012; Skelly 1992; Tang 2006; Tangtrakul 1994; Van den Brand 2001).

We describe the interventions in detail in Table 7.

4. Interventions.

| Study ID | Gender of Participants | Intervention A | Intervention B |

| Ahmed 1993 | Men only | Indwelling urethral catheterisation placed preoperatively using 1& Xylocaine gel under aseptic technique | Suprapubic catheter (Stamey‐type, 12 French or 14 French), placed preoperatively under local anaesthetic |

| Andersen 1985 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (Charriere16, Foley) inserted preoperatively | Suprapubic catheter (Charriere 12, Ingram) introduced after termination of the operation |

| Baan 2003 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheter (Foley) placed before surgery after surgical scrub | Suprapubic catheter (Braun) placed at the time of surgery |

| Barents 1978 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheter (Silicath Foley) introduced after termination of the operation | Suprapubic catheter (12 Charriere, Silastic Cystocath) introduced perioperatively or after termination of the operation |

| Barry 1992 PE | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheterisation. Inserted at induction | Suprapubic catheterisation. Inserted at laparotomy |

| Bergman 1987 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (14 F Foley) introduced before surgery | Suprapubic catheterisation (5F Bonnano) introduced after termination of the operation |

| Botsios 1997 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (14‐ or 16‐french Foley) introduced after induction of anaesthesia | Suprapubic catheterisation (Cystofix B) introduced intraoperatively |

| Carpiniello 1988 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheter (Foley) placed preoperatively and maintained for 24 hours | Intermittent catheter performed in recovery room |

| Dixon 2010 | Women only | Indwelling suprapubic catheter inserted in theatre, left on free drainage for 48 hours postoperatively | Intermittent catheterisation postoperatively if unable to pass urine within 6 hours of return from theatre or earlier if uncomfortable or if passing frequent (< 2‐hourly), small volumes of urine (< 200 ml). Continued until can void > 200 ml with post‐void residual volumes < 100 ml |

| Dobbs 1997 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheter (14 F, Foley) inserted under anaesthetic and removed the night after surgery (about 36 hours after operation). In case of urinary retention thereafter, a urethral catheter was inserted for a further 24 hours | Intermittent catheterisation: 'In‐out' catheterisation with a disposable female catheter. Participants who felt the need to pass urine but were unable to do so, or had not passed urine by 12 hours after surgery, had a further IC. When, thereafter, participants required IC again, a urethral catheter was inserted for 24 hours |

| Evron 2008 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (multi‐orifice Foley catheter) placed 90 minutes after epidural induction (average 3 cm cervical dilation) and removed after delivery | Intermittent catheterisation (multi‐orifice Foley catheter) placed 90 minutes after epidural induction (average 6 cm cervical dilation) and removed. Process repeated when clinical indication of urinary retention |

| Hakvoort 2011 | Women only | Indwelling urethral (14 french silicone) catheter was inserted by nursing staff for 3 days on first postoperative day if PVR ≥ 150 ml | Intermittent A SpeediCath® (Coloplast, Humlebaek, Denmark) catheter was inserted with maximum interval 6 hours over 3 days on first postoperative day if PVR ≥ 150 ml |

| Halleberg 2013 | Men and women | Indwelling Foley catheter inserted by registered nurses (RNs) or assistant nurses (ANs). Participants with hip fracture had catheter inserted upon arrival on orthopaedic ward. Participants with osteoarthritis were given the catheter in the morning on the day of the surgery | Intermittent catheterisation introduced if participant was unable to urinate and bladder scan indicated ≥ 400 ml urine in the bladder |

| Hammarsten 1992 | Men only | Indwelling urethral catheter (either teflon‐ or PVC‐coated) | Suprapubic catheter (PVC) |

| Harms 1985 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (14 Charriere Foley) introduced after termination of the operation | Suprapubic catheterisation (Cystofix) |

| Ichsan 1987 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheter inserted by members of nursing staff. Urine sample obtained every 2 days until catheter removed for bacteriological culture, organism count + repeat specimens | Suprapubic catheter inserted by resident medical officers. Urine sample obtained every 2 days until catheter removed for bacteriological culture, organism count + repeat specimens |

| Jannelli 2007 | Women only | Bonanno suprapubic catheter placed intraoperatively | CISC (14French disposable vinyl catheter) started on 1st postoperative day. (16 FRench silicone Foley catheter placed intraoperatively to monitor urine output in the immediate postoperative period) |

| Katz 1992 | Men only | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (12F silicone‐coated or Teflon‐coated Foley catheter lubricated with paraffin oil) in the operating room after anaesthetic or after surgery completion | Suprapubic catheterisation (8F Cystocath manufactured by Dow Corning Corporation) in the operating room after completion of surgery |

| Kerr‐Wilson 1986 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (Foley catheter) inserted immediately before surgery after epidural had been inserted. Removed once the participant was ambulant. | Intermittent catheterisation ‘in‐out’ (Nelaton catheter) inserted immediately before surgery after epidural had been inserted. Removed at the end of operation |

| Knight 1996 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheter (Foley) placed just prior to surgery. Remained in place for 48 hours. Thereafter, urinary retention was treated with intermittent catheterisation | Intermittent catheterisation every 6 hours if participants were unable to void or were voiding in volumes of 50 ml or less |

| Korkes 2008 | Men only | Discharged with indwelling urethral catheter following surgery | Discharged with suprapubic catheter following surgery |

| Kringel 2010 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheter (silicone Foley) placed intraoperatively left indwelling for 24 or 96 hours | Suprapubic catheter (silicone Foley) placed intraoperatively left for 96 hours |

| Michelson 1988 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheter inserted just before surgery. Removed the morning after surgery. Urinary retention was treated with intermittent catheterisation following this. If retention continued > 48 hours, indwelling catheter was inserted again | Intermittent catheterisation performed postoperatively by nursing staff only if urinary retention occurred. Performed at least every 6 hours. If retention continued > 48 hours, indwelling catheter was inserted |

| Millet 2012 | Women only | Indwelling Foley catheter (14 French Bard Foley tray, with Bardex Lubricath, anti‐reflux chamber drainage bag, and EZ lock sampling port) inserted after epidural placement. Removed in the 2nd stage of labour at the start of pushing | Intermittent catheter (Bard™ urethral catheterisation tray and 15Fr red, rubber catheter) every 4 hours and as needed after epidural placement. Stopped at delivery |

| Naik 2005 | Women only | Suprapubic catheterisation. Insertion of Bonanno suprapubic catheter (Becton Dickenson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) at the time of surgery. On free drainage for 5 days. Woman asked to pass urine normally every 4 hrs, then measure residual volume using catheter. Catheter was removed when residual volume < 100 ml | Intermittent catheterisation. Transurethral indwelling catheter was inserted at the time of surgery. Removed on day 5, women would pass urine every 4 hours then measure residual volume using intermittent catheter. Intermittent catheterisation ceased when residual volume < 100 ml. (hydrophilic coated LoFric – Astra Tech Ltd, Stroudwater Business Park, Stonehouse) |

| Nwabineli 1993 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheterisation placed before operation | Suprapubic catheterisation introduced after termination of the operation |

| O'Kelly 1995 | Men and Women | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (14‐Fr; Foley) before operation | Suprapubic catheterisation (14‐Fr; Foley) after the abdomen was opened |

| Perrin 1997 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (16‐French; Foley) inserted following induction of anaesthesia | Suprapubic catheterisation (16‐French; Foley) inserted after the opening of the abdomen |

| Piergiovanni 1991 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (Charriere 12 to 20; Foley ) | Suprapubic catheterisation (Charriere 10; Cystofix) |

| Prasad 2014 | Men only | Indwelling urethral catheter placed intraoperatively, removed on postoperative day 7 | Suprapubic catheter placed 24 hours after surgery, removed on postoperative day 7. Had indwelling urethral catheter prior to this |

| Rasmussen 1977 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheter (Foley, No. 16 French) was inserted before surgery and kept on during first 24 hours. After this was closed and opened every 6 hours. Removed on 5th day. | Suprapubic catheter (No. 5 French polyethylene tube) was inserted before surgery and drained continuously for 24 hours. After this, was opened and closed for 10 minutes every 6 hours. Removed when post‐voidal volume < 100 ml during each of 2 subsequent measurements |

| Ratnaval 1996 | Men only | Indwelling urethral catheter placed during surgery. Removed based on participant well‐being | Suprapubic Bonanno catheter placed at end of surgery. When suprapubic catheter was going to be removed, it was clamped and the residual volume measured. If it was < 50 ml, the catheter was removed |

| Rivard 2012 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheter. Removed during 2nd stage of labour when woman started pushing | Intermittent catheter inserted every 2 to 4 hours |

| Schiotz 1989 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheter (No.14, Foley) introduced at the end of surgery | Suprapubic catheter (No.10, Cystofix) introduced at the end of surgery |

| Sethia 1987 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (14 F Foley) inserted immediately before operation | Suprapubic catheterisation (14 F Foley) placed perioperatively |

| Skelly 1992 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheter inserted preoperatively and left in place until 48 hours after surgery. If could not void in following 24 hours, intermittent catheterisation performed every 8 hrs for 24 hrs. If still not able to void indwelling catheter inserted again for 48 hours | Intermittent catheter inserted every 6 ‐ 8 hrs, with 400 ‐ 600 ml of urine removed each time. Catheterisation stopped when residual volume of urine < 150 ml on 2 consecutive occasions |

| Stekkinger 2011 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheterisation using 14 French (brand not specified) placed intraoperatively, removed postoperative day 3; measurements begun in morning of postoperative day 4 | Suprapubic catheterisation using 15Fr Cystofix™ SPT catheter, sutured to participant's skin (B. Braun Medical, Oss, Netherlands) placed intraoperatively, clamped on the 3rd night after surgery |

| Tang 2006 | Women only | Indwelling Foley catheter, placed after randomisation. Removed at least once weekly, replaced if PVR > 300 ml. | CISC, monitored by bladder scan 3 times a day. CISC performed when PVR > 500 ml or > 300 ml and symptomatic. |

| Tangtrakul 1994 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheter placed just before operation. Removed following day after operation | Intermittent catheterisation. Catheterised just before operation. Removed immediately after operation |

| Van den Brand 2001 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheter (Foley) introduced in the operating room just before the start of surgery. Catheter remained in place for 48 hours | In‐out catheterisation every 6 hours or earlier when clinically needed by a trained staffed nurse until spontaneous voiding occurred |

| Vandoni 1994 | Men and women | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (Charriere 12 latex Foley catheter) | Suprapubic catheterisation (Cystofix(R), Braun‐SSC, Switserland) |

| Wiser 1974 | Women only | Indwelling urethral catheterisation (16 Foley) inserted postoperatively | Suprapubic catheterisation (16 Foley) |

CISC: clean intermittent self catheterisation PVR: post‐void residual

Indication for catheter removal

Only some of the included trials reported an indication or day that the urinary catheter should be removed.

Fourteen trials did not indicate when the catheter should be removed (Ahmed 1993; Baan 2003; Barents 1978; Barry 1992 PE; Evron 2008; Harms 1985; Ichsan 1987; Jannelli 2007; Katz 1992; Ratnaval 1996; Rivard 2012; Sethia 1987; Tang 2006; Vandoni 1994). Among the trials that did report an indication for catheter removal, they were either based on clinical indication, on timing, or on a mixture of the two.

Fourteen trials removed the catheter at a specific time point (Bergman 1987; Botsios 1997; Carpiniello 1988; Dobbs 1997; Hakvoort 2011; Knight 1996; Korkes 2008; Kringel 2010; Perrin 1997; Piergiovanni 1991; Prasad 2014; Schiotz 1989; Tangtrakul 1994; Wiser 1974), ranging from immediately after surgery (Carpiniello 1988; Dobbs 1997; Tangtrakul 1994) to seventh postoperative day (Korkes 2008; Prasad 2014).

Seven trials removed catheters based on clinical indication (Dixon 2010; Halleberg 2013; Hammarsten 1992; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Millet 2012; O'Kelly 1995; Stekkinger 2011). The clinical indications included post‐void residual volume < 150 ml (Halleberg 2013; Stekkinger 2011), or during the second stage of labour (Millet 2012).

The remaining seven trials combined a specific time point for clamping or trialing removal of the catheter and clinical indication.

Outcomes

The trials used a number of different ways to define microbiological outcomes. Eight trials were classified as reporting symptomatic UTI (Baan 2003; Barry 1992 PE; Dixon 2010; Hakvoort 2011; Korkes 2008; Kringel 2010; Schiotz 1989; Tang 2006). We used the following definitions:

≥ 10⁵ cfu/ml and at least one symptom of UTI (e.g. fever, suprapubic tenderness, dysuria) (Baan 2003; Dixon 2010; Hakvoort 2011; Kringel 2010; Schiotz 1989);

> 10⁴ cfu/ml and leucocituria with at least one sign or symptom (e.g. fever, malaise, haematuria, pain, etc.) (Korkes 2008)

Fever in the absence of other sites of infection (Tang 2006);

No definition (Barry 1992 PE). The only report of this trial that we could find was an abstract. It is unsurprising, therefore, that no definition of symptomatic UTI was supplied. We assumed that the trial used an appropriate definition.

The time that the urine sample was taken for diagnosis of symptomatic UTI also varied between trials. The urine samples were taken at the following times:

Preoperatively (Dixon 2010; Schiotz 1989);

At catheter removal (Hakvoort 2011; Schiotz 1989);

Sample taken based on clinical symptoms (Dixon 2010);

-

Postoperatively:

daily (Barry 1992 PE);

4th postoperative day (Kringel 2010);

1st and 14th day of hospitalisation (Tang 2006)

48 hours after catheter removal (Baan 2003)

Follow‐up: 6 to 8 weeks postoperatively (Schiotz 1989)

We describe the methods of measuring symptomatic UTI in the trials in Table 8.

5. Measurement of symptomatic urinary tract infection.

| Study ID | Outcome as defined by trialists | Definition | When urine sample was taken | Outcome as defined by IDSA criteria |

| Baan 2003 | UTI | ≥ 1 clinical symptoms (fever, increased micturition frequency, burning pain during voidance, pain in lower abdomen); positive sediment (> 10 leukocytes); positive urine culture of > 10⁵ bacterial colonies + < 3 bacterial species | 48 hours after catheter removal | Symptomatic UTI |

| Barry 1992 PE | UTI | No definition | Daily until catheter removal | Unknown, so collect data assuming symptomatic UTI |

| Dixon 2010 | UTI | Catheter specimen of urine or a midstream urine specimen showing a single bacterium growing at a colony count of > 105 cfu/ml. Specimen only taken if UTI suspected on the basis of: pyrexia > 37.5° C, frequent voiding + discomfort when passing urine and positive urinalysis for leukocytes + nitrites | Preoperatively, and postoperatively if UTI suspected | Symptomatic UTI |

| Hakvoort 2011 | UTI | > 10⁵ cfu/ml + ≥ 1 of the following: fever, urinary frequency (> 7 voids/day), dysuria, lower abdominal pain | After PVR had normalised and catheterisation had stopped | Symptomatic UTI |

| Korkes 2008 | UTI | No definition | No information | Unknown, so collect data assuming symptomatic UTI |

| Kringel 2010 | Symptomatic UTI | CDC definition: Indwelling urinary catheter was in place for > 2 calendar days on the date of event, with day of device placement being Day 1, AND an indwelling urinary catheter was in place on the date of event or the day before. If an indwelling urinary catheter was in place for > 2 calendar days and then removed, the UTI criteria must be fully met on the day of discontinuation or the next day. Patient has at least one of the following signs or symptoms: fever (> 38.0° C), suprapubic tenderness, costovertebral angle pain or tenderness, urinary urgency, urinary frequency, dysuria. Patient has a urine culture with no more than 2 species of organisms, at least one of which is a bacteria of ≥ 10⁵ cfu/ml. | 4th postoperative day | Symptomatic UTI |

| Ratnaval 1996 | UTI | No definition | Prior to removal of catheter and if participants developed urinary symptoms after catheter removal | Unknown, so collect data assuming symptomatic UTI |

| Schiotz 1989 | UTI | Bacteriuria > 105 organisms/ml AND ≥ 1 of following: dysuria, pain, fever (rectal temp > 38.5° C measured twice), rigors, sepsis | Preoperatively, at catheter removal and at follow‐up 6 ‐ 8 weeks postoperatively | Symptomatic UTI |

| Tang 2006 | symptomatic UTI | Fever in the absence of other sites of infection with or without symptoms of dysuria or suprapubic discomfort on day 14 | 1st and 14th days | Symptomatic UTI |

PVR: post‐void residual

Twenty trials reported asymptomatic bacteriuria. However, an additional 13 trials that said they were reporting UTI were actually reporting asymptomatic bacteriuria (without clinical symptoms), and we reclassified them. Thirty‐three trials reported asymptomatic bacteriuria, using the following definitions:

≥ 10³ cfu/ml (Bergman 1987; Vandoni 1994);

≥ 10⁴ cfu/ml (Perrin 1997; Piergiovanni 1991; Sethia 1987; Stekkinger 2011; Wiser 1974). One of these trials used a count of > 10⁴ but < 10⁵ cfu/ml as not being diagnostic of bacteriuria (Wiser 1974). Another trial used > 10⁴ cfu/ml to define bacteriuria in participants who still had a catheter present, on the basis that a smaller density of bacteria may be significant (Sethia 1987);

≥ 10⁵ cfu/ml (Ahmed 1993; Andersen 1985; Baan 2003; Barents 1978; Botsios 1997; Carpiniello 1988; Dobbs 1997; Evron 2008; Hakvoort 2011; Halleberg 2013; Harms 1985; Jannelli 2007; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Knight 1996; Kringel 2010; Michelson 1988; Millet 2012; Nwabineli 1993; O'Kelly 1995; Rasmussen 1977; Sethia 1987; Skelly 1992; Tang 2006; Tangtrakul 1994; Van den Brand 2001; Wiser 1974);

No definition (Naik 2005; Ratnaval 1996). No definition for bacteriuria was provided. The outcome was named "positive CSU (catheter specimen of urine)/MSU (midstream of urine)" by Naik 2005. Whereas Ratnaval 1996 reported using culture positive urine samples for diagnosing bacteriuria. We assumed the trialists used an appropriate bacterial culture level.

The time that the urine sample was taken also varied greatly between trials:

At time of catheter insertion (Ahmed 1993; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Millet 2012; Perrin 1997; Piergiovanni 1991; Rasmussen 1977; Sethia 1987);

At time of catheter removal (Ahmed 1993; Barents 1978; Hakvoort 2011; Kerr‐Wilson 1986; Perrin 1997; Piergiovanni 1991; Stekkinger 2011);

Day of discharge (Halleberg 2013; Millet 2012);

-

Postoperatively:

daily (Nwabineli 1993; O'Kelly 1995; Sethia 1987; Vandoni 1994);

every 2 days (Bergman 1987);

2nd postoperative day (Dobbs 1997; Jannelli 2007; Knight 1996; Michelson 1988; Van den Brand 2001);

3rd postoperative day (Carpiniello 1988; Naik 2005; Tangtrakul 1994);

4th postoperative day (Kringel 2010; Wiser 1974);

5th postoperative day (Andersen 1985; Barents 1978; Knight 1996; Naik 2005; Rasmussen 1977; Skelly 1992);

6th postoperative day (Harms 1985);

7th postoperative day (Barents 1978; Carpiniello 1988; Jannelli 2007; Michelson 1988; Naik 2005);

14th postoperative day (Naik 2005);

21st postoperative day (Naik 2005);

two days after catheter removal (Baan 2003; Botsios 1997; O'Kelly 1995; Sethia 1987)

-

At follow‐up:

four weeks (Halleberg 2013);

six weeks (Ahmed 1993);

three months (Rasmussen 1977).

We describe the methods of measuring asymptomatic bacteriuria in the trials in Table 9.

6. Measurement of asymptomatic bacteriuria.

| Study ID | Outcome as defined by trialists | Definition | When urine sample was taken | Outcome as defined by IDSA criteria |

| Ahmed 1993 | bacteriuria | urine culture with bacterial count > 10⁸ colonies/millilitre | At time of catheterisation and repeated if delay in the operation; at the time of catheter removal, and at 6 weeks follow‐up if symptomatic of UTI. | bacteriuria |

| Andersen 1985 | postoperative urinary infection | “Postoperative urinary infection was defined as significant bacteriuria (>100000 colony‐forming units per ml urine)” | 5th postoperative day (catheter removed by POD 5) | bacteriuria |

| Baan 2003 | postoperative culture | positive urine culture (> 10⁵ bacterial colonies + < 3 bacterial species) within 6 weeks of surgery) | 48 hours after catheter removal | bacteriuria |

| Barents 1978 | significant bacteriuria | ≥ 10⁵ micro‐organism/ml | 5th and 7th postoperative day, and on day of catheter removal | bacteriuria |