Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

Key Words: crew resource management, teams, training, teamwork, intervention, systematic review, patient safety

Abstract

Objective

The aim of this article was to present an overview of the crew resource management (CRM) literature in healthcare. The first aim was to conduct an umbrella review on CRM literature reviews. The second aim was to conduct a new literature review that aims to address the gaps that were identified through the umbrella review.

Methods

First, we conducted an umbrella review to identify all reviews that have focused on CRM within the healthcare context. This step resulted in 16 literature reviews. Second, we conducted a comprehensive literature review that resulted in 106 articles.

Results

The 16 literature reviews showed a high level of heterogeneity, which resulted in discussing 3 ambiguities: definition, outcome, and information ambiguity. As a result of these ambiguities, a new comprehensive review of the CRM literature was conducted. This review showed that CRM seems to have a positive effect on outcomes at Kirkpatrick’s level 1, 2, and 3. In contrast, whether CRM has a positive effect on level 4 outcomes and how level 4 should be measured remains undetermined. Recommendations on how to implement and embed CRM training into an organization to achieve the desired effects have not been adequately considered.

Conclusions

The extensive nature of this review demonstrates the popularity of CRM in healthcare, but at the same time, it highlights that research tends to be situated within certain settings, focuses on particular outcomes, and has failed to address the full scope of CRM as a team intervention and a management concept.

Healthcare organizations located around the globe are increasingly facing the challenge of providing higher levels of care with the same or even less means.1 The demand for care is growing rapidly because of the increasing life expectancy, number of aging people, comorbidity, and treatment possibilities. At the same time, the supply of care cannot be increased because of government-initiated cost-saving programs that aim to keep healthcare systems affordable and sustainable. As a result, teamwork is seen as a key ingredient in helping healthcare organizations face this environmental dynamism. Several studies support the notion that teamwork is one of the most critical components of a high functioning healthcare system (e.g., the study by Rosen et al2). Similarly, the importance of teamwork was loudly acknowledged within the Institute of Medicine hallmark report “To Err Is Human, Crossing the Quality Chasm,” which evidenced a link between the lack of teamwork and preventable medical errors. In addition, they cited that training in team behavior is essential given its role in reducing medical errors and increasing patient safety.3,4

Consequently, healthcare organizations are using interventions that aim to improve team functioning. In particular, Hughes et al5 (2016) showed in their meta-analysis the high potential that team training programs in healthcare had on a variety of outcomes including patient health. Although there are various teamwork training programs being used within the healthcare industry, crew resource management (CRM) is likely the most well-known and widely applied intervention within healthcare organizations aimed to enhance team functioning and improve patient safety.

Crew resource management is often referred to as a training intervention that covers nontechnical skills such as situational awareness, decision making, teamwork, leadership, coping with stress, and managing fatigue.6 A typical CRM training program comprises a combination of information-based methods (e.g., lectures), demonstration-based methods (e.g., videos), and practice-based methods (e.g., simulation, role playing).7 However, at its core, CRM is a management concept that aims to maximize the use of all available resources (i.e., equipment, time, procedures, and people).8 In addition, CRM is an intervention that addresses all aspects of organizational operations rather than being limited to the introduction of a specific training to achieve a specific outcome. As such, the general aim of CRM interventions is “to provide members with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to respond to highly demanding situations in a competent manner that proactively seeks to minimize the risk of errors.”9 Crew resource management is thus a system-wide approach that seeks to avoid errors, detect errors before they occur, and mitigate the consequences of errors that are not detected in a timely fashion.10

As a result of the theorized promise surrounding CRM initiatives, there is a large and rapidly increasing amount of literature that has evaluated CRM in different (especially high-risk) healthcare settings.11 Most of these studies report a positive effect of CRM at 1 or more levels of Kirkpatrick’s framework for evaluation of interventions: reactions, learning/knowledge, behavior, and organizational outcomes (see Appendix 1, http://links.lww.com/JPS/A376). As a result of the growing body of evidence focused on CRM and its potential, multiple literature reviews have been conducted with the aim to provide an overview of what CRM entails and its impact. For example, in 2014, 2 reviews were published on CRM: a meta-analysis by O’dea et al7 (2014) and a systematic review by Verbeek-van Noord et al12 (2014). O’dea et al7 (2014) found 20 studies that evaluated CRM in the acute healthcare domain. Based on their work, they concluded that CRM has a large effect on knowledge and behavior and a small effect on attitudes.7 However, the evidence for an effect on clinical care outcomes was unsupported in their meta-analysis, as was the long-term impact of the training. In comparison, Verbeek-van Noord et al12 (2014) found 22 studies that evaluated classroom-based CRM training on safety culture in a broad range of healthcare domains. They concluded that results regarding the effect of CRM on safety culture were mostly mixed.12 In addition to this unclear picture of the impact of CRM on safety culture, these 2 studies also provide a vivid example of the reviews that have been conducted in this area—they include studies with a variety in levels of quality, and the impact that CRM has depends on how effectiveness is defined. In addition, it should be emphasized that the conclusions derived from such reviews are not based on the same studies given that the target group and CRM content are often different from one review to another. Of the 42 studies included in these 2 reviews, only 2 were included in both reviews.13,14

This lack of overlap speaks to the high level of heterogeneity of studies that exist within the overall CRM literature. In part, this heterogeneity is caused by differences in the CRM curricula, the healthcare setting, the target group within a healthcare setting, and the methods used to evaluate a given CRM intervention. We are not the first to point out these “issues” within the CRM literature. In a recent literature review, Gross et al11 (2019) pointed out these diversities and concluded that CRM seemed to be an umbrella concept of human factors and safety training.

As such, we echo prior sentiments speaking to the need for a comprehensive and structured overview of the CRM literature to ascertain what is really known about CRM in healthcare, given that this has yet to be addressed. Here, we seek to address this gap as this study aims to synthesize the scientific knowledge on CRM by analyzing the results of all literature reviews conducted on CRM to date. This will hopefully provide us insights regarding the current state of the literature based on prior literature reviews. However, given the discrepancies and gaps in the literature reviews conducted thus far, within the current study, we will also conduct a more comprehensive review of the literature with the intent to provide a more complete picture of research conducted on CRM within healthcare to date and highlight where future research is needed.

This literature review consists of 2 phases. The goal of the first phase is to synthesize the findings from all literature reviews (not only systematic reviews) addressing CRM within healthcare settings. During this phase of our work, we will conduct an umbrella review (e.g., the study by Aromataris et al15) of the CRM literature. The second phase of our work aims to review the CRM literature from 2006 to August 2019 addressing the gaps that were identified through the umbrella review process.

METHODS: PHASE 1: UMBRELLA REVIEW OF CRM LITERATURE REVIEWS

Search Strategy

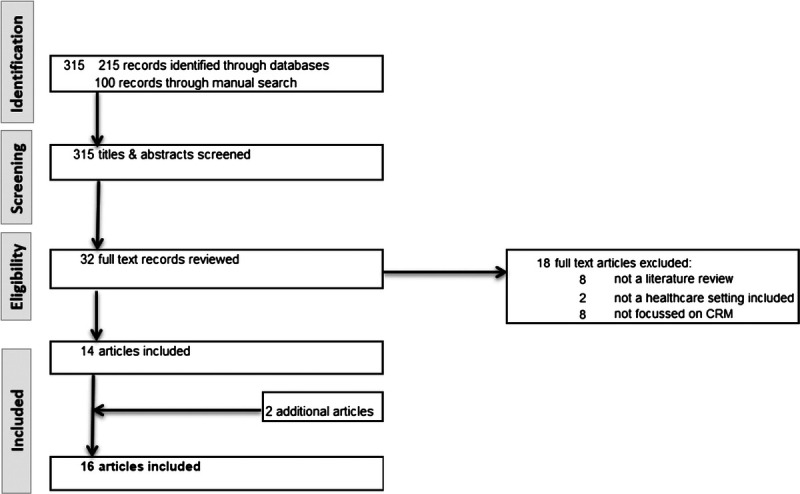

We searched the following databases to locate literature reviews conducted to date on the topic of CRM: EMBASE, Medline, and Web of Science. The search involved a combination of the key words “CRM” OR “crew resource management” OR “crisis resource management,” in combination with (i.e., AND) “review (see Appendix 2,http://links.lww.com/JPS/A377).” This search strategy resulted in 215 hits. This search was expanded by a manual search in Google Scholar. These hits were subject to a stepwise evaluation process as shown in Figure 1. First, the title and abstract were evaluated by adhering to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see hereinafter), which narrowed our population down to 32 articles. Two of the authors followed these steps, and in the case of disagreement or doubt, it was proceeded to the next step. Second, this subset of articles was evaluated by looking at the entire texts while using the same criteria. This narrowed the list of reviews down to 14 articles. Two of the authors followed this step, and in the case of disagreement, a third author was included in the discussion to make the final decision. In addition, the author team closely analyzed and summarized the reference list of each article to identify any additional articles that may not have surfaced through the literature search process. This step resulted in 2 additional articles. As a result, in total, our umbrella review consisted of the 16 literature reviews that were selected.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart phase 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The criteria for inclusion in our study were as follows: the article needed to (1) present a literature review (e.g., systematic, narrative), (2) that was written (or translated) in English, (3) published in a peer-reviewed journal, (4) with a focus on how CRM can improve performance, and (5) focused (at least partly) on CRM in healthcare. We did not weigh the quality of the literature reviews into the inclusion criteria to capture all potentially relevant studies. Likewise, we did not include (nor exclude) articles based on the actual content of the CRM intervention. As such, if the authors of the underlying literature reviews referred to CRM, an inclusion criterion 4 was met. We also included reviews that presented several team interventions that also included CRM, as long as it was clear which articles focused on a CRM intervention and could therefore be extracted. In addition, we did not consider publication year in our decision as to whether to include or to exclude a particular article. Each of these decisions was made in an attempt to ensure that we were able to identify all reviews of the CRM literature within healthcare.

That said, we did apply certain exclusion criteria. Specifically, literature reviews were excluded when (1) no overview of articles was presented as a result of the literature search, (2) the presented articles were not focused on CRM but, for example, on education, and (3) reviews in which articles on CRM in healthcare were not present or represented in an overview of results. Literature reviews that focused on a variety of settings that also included healthcare were included in our umbrella review, but these reviews were selectively summarized and analyzed so as to emphasize the findings relevant to the healthcare context.

Analysis

The 16 literature reviews that were included in our umbrella review are summarized in Table 1. Within this table, we highlight the author, year, title, aim/research question, methods (inclusion and exclusion criteria), setting, number of articles included within the underlying literature review, main result/conclusion, and the quality of the methods using the AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) tool.29 The AMSTAR consists of 11 items and results in a score ranging from 0 to 11. Based on the 16 literature reviews, 3 categories were constructed, reviews that focused on (1) CRM training in general, (2) simulation training, which is seen as crucial element of CRM, and (3) team training in which CRM is seen as 1 type of team training.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Selected Literature Reviews: Phase 1

| Authors (Year) | Aim/Research Question(s) | Methods: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Setting | Number of Articles | Main Findings | AMSTAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Reviews that focus on CRM | ||||||

| Boet et al16 (2014) | “To gain a better understanding of the impact of simulation-based CRM teaching on transfer of learning to the workplace and subsequent changes in patient outcomes.” | Inclusion criteria: “studies that used simulation-based CRM teaching with outcomes measured at Kirkpatrick level 3 (transfer of learning to the workplace) or 4 (patient outcome).” Exclusion criteria: “studies measuring only learners’ reactions or simple learning (Kirkpatrick level 1 or 2, respectively)”; “papers reporting solely self-assessment data and considered a level 1 (reaction) outcome”; and articles where it’s was not possible to “separate out teaching and/or assessment of technical skills from nontechnical skills in an acute care context.” |

Acute care settings | 9 | “CRM skills learned at the simulation center are transferred to clinical settings, and the acquired CRM skills may translate to improved patient outcomes, including a decrease in mortality.” | 9 |

| Fung et al17 (2015) | “To assess: (i) the effectiveness of simulation-based CRM team training compared to any other educational intervention among interprofessional or interdisciplinary teams and (ii) to determine whether simulation-based CRM team training leads to the modification of attitudes, skill/knowledge acquisition, changes in behaviors, and improved patient outcomes.” | Inclusion criteria: articles with following study characteristics (i.e., randomized controlled trials, quasi-randomized controlled trials, controlled before-after studies, or interrupted time series); patient characteristics (i.e., all healthcare providers and all levels of training); and learning intervention (i.e., interprofessional or Interdisciplinary education, CRM, and simulation-based) | Healthcare | 15 | “CRM simulation-based training for interprofessional and interdisciplinary teams shows promise as a superior training method over traditional nonsimulation clinical teaching of CRM principals.” “All but one of the included interprofessional and interdisciplinary studies found significant improvements in at least one of the learning outcomes when using simulation-based CRM team training compared to alternate forms of training, such as didactic teaching or case-based learning.” “No studies reported outcomes that were worse in the simulation-based CRM training group compared to any comparator group.” |

7 |

| Gross et al11 (2019) | “To identify what is subsumed under the label of CRM in a healthcare context and to determine how such training is delivered and evaluated.” | Inclusion criteria: healthcare staff, individually constructed training formats addressing CRM principles or aviation-derived human factors, studies reporting both the intervention and its effect, published in an academic journal, either in English or German. | Healthcare | 64 | Almost half of the studies “did not explain any key word of their CRM intervention to a reproducible detail. Operating room teams and surgery, emergency medicine, intensive care unit staff and anesthesiology came in contact most with a majority of the CRM interventions delivered in a 1-day or half-day format. Trainer qualification is reported seldomly. Evaluation methods and levels display strong variation.” | 10 |

| Maynard et al18 (2012) | To provide clarity by providing a review of the literature, to highlight the current state of the literature and to identify areas to be addressed by researchers in this field going forward. | A number of search techniques were used. Detailed information on the methods is lacking. | Healthcare | 7 (presented) | CRM and teamwork training programs generally seem beneficial to individual employees, the groups and teams within such settings, and overall healthcare organizations. | 3 |

| O’dea et al7 (2014) | “To determine the aggregate size of the effect of CRM training in acute care settings at four different levels of evaluation: reactions, learning, behavior and clinical care outcomes. Additionally, to identify biases in the research evidence in order to improve the quality of future CRM training interventions in healthcare and also the quality of evaluations of those interventions.” | Inclusion criteria: “studies must report CRM-type training interventions that are focused on improving teamwork within healthcare teams in acute care environments; and training effectiveness must be assessed at least one level of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation hierarchy.” Exclusion criteria: “training that focuses on specific technical skills or procedures rather than on teamwork; and studies that relate to patient or relative centered communication or collaboration, and studies aimed at administrators, leaders or managers.” |

Acute care settings | 20 | “The meta-analysis of CRM-type team training in healthcare found that participants like this type of training.” “There was a large effect of training on knowledge, a small effect of training on attitudes and a large effect of training on behavior.” “The evidence for an effect on clinical care outcomes, or the long-term impact of the training, was unsupported in this meta-analysis.” |

8 |

| O’Connor et al19 (2008) | “To use meta-analyses techniques to evaluate the effectiveness of CRM training.” | Inclusion criteria: “an evaluation had to be reported from at least one of the first three levels of Kirkpatrick’s (1976) evaluation hierarchy: reactions, learning (attitudes and knowledge), or behaviors.” | All settings | 16 (4 HC) |

CRM had a large effect on attitudes and behaviors and a medium effect on their knowledge. | 10 |

| Salas et al20 (2006) | To provide “the state of CRM training evaluations since the Salas et al (2001) review and extends it to areas beyond aviation cockpits.” | Inclusion criteria: articles that present “the findings of a study evaluating the impact of CRM training on trainees’ reactions, learning, or behaviors and/or its impact on the organization.” | All settings | 28 (12 HC) | Although no study was covered “that suggests CRM training does not work, approximately half of the studies indicated mixed results, leading us to question its effectiveness.” | 8 |

| Verbeek-van Noord et al12 (2014) | “To evaluate the evidence of the effectiveness of classroom-based crew resource management training on safety culture (…).” | Inclusion criteria: articles on “training focussed on health-care teams in hospitals and covered at least two CRM topics (e.g., communication and leadership).” Exclusion criteria: “studies evaluating CRM in preclinical medical education, outside healthcare, in primary care, and dental care”; “CRM training courses based (partly) on high-tech simulation techniques”; and “manuscripts based on qualitative research.” |

Hospitals | 22 | “Training settings, study designs, and evaluation methods varied widely.” “Most studies reporting only a selection of culture dimensions found mainly positive results, whereas studies reporting all safety culture dimensions of the particular survey found mixed results.” |

8 |

| Zeltser and Nash21 (2010) | “To report on the body of empirical data about CRM training in clinical settings and to provide a conceptual framework for evaluating its effectiveness in medicine.” | Inclusion criteria: “published in peer-reviewed journals, printed in the English language, published in the past 20 years, and presented original data.” | Clinical settings | 19 | “The purpose of each of the selected studies was to evaluate the effectiveness of a CRM training program for clinical providers.” The authors present “a conceptual framework for evaluating such programs and generating evidence for organizational impact. The framework identified a classification for outcomes measures, which were classified as either learner measures, process measures, or organizational measures.” |

7 |

| II. Reviews that focus on simulation | ||||||

| Doumouras et al22 (2012) | “To appraise and summarize the design, implementation, and efficacy of peer-reviewed, simulation-based CRM training programs for postgraduate trainees (residents).” | Inclusion criteria: “articles that were written in English; were published in peer-reviewed journals; included residents; contained a simulation component; and included a team-based component.” Exclusion criteria: “articles that included staff/fellow physician or medical student training; bore no evaluative component for residents; did not include crisis scenarios; and did not train and evaluate residents in a team environment.” |

Surgery | 15 | “Residents find utility in simulation training and that it can change team-based team behaviors in crisis scenarios.” There is a high degree of satisfaction and perceived value that reflects robust resident engagement. “However, the evidence for translating and measuring the extent of performance from the simulator to the clinical domain remains elusive.” |

7 |

| Murphy et al23 (2015) | “To determine the current state of knowledge about the key components and impacts of multidisciplinary simulation-based resuscitation team training.” | Inclusion criteria: articles that include evaluation of in-hospital resuscitation teams; articles on medical practitioners and allied health staff. Exclusion criteria: articles focused on teams in nonacute settings such as primary care (palliative care, community) or rehabilitation; articles on team performance of end-of-life care; communication tools and clinical handover techniques. |

Emergency department | 11 | The relationship between team training and team performance is supported. “Simulation is an effective method to train resuscitation teams in the management of crisis scenarios and has the potential to improve team performance in the areas of communication, teamwork and leadership.” |

9 |

| Tan et al24 (2014) | To “describe and explore the actual state of multidisciplinary team simulation in surgery.” | Inclusion criteria: “articles that were written or translated to English; published in peer-review journals; contained a simulation component, included surgical trainees/surgeons within a multidisciplinary OT team; and were published during 1990–2012.” Exclusion criteria: articles that “did not train or evaluate multidisciplinary groups in a simulated OT environment (…); assessed only a single professional group (…); included nonsurgeon groups as scripted confederates (…); and assessed only technical skills.” |

Surgery | 26 | “Surgical team simulations are feasible and have received largely positive reactions from participants and some have reported changes to their behavior and interaction within a team environment from this form of learning.” | 6 |

| III. Reviews that focus on team training in general | ||||||

| Buljac-Samardzic et al25 (2010) | “Which types of interventions to improve team effectiveness in healthcare have been researched empirically, for which target groups and for which outcomes? To what extent are these findings evidence based?” | Inclusion criteria: “peer-reviewed English-language publication; a focus on healthcare; a focus on how to improve (and not only measure) team effectiveness; and empirically researched results.” | Healthcare | 48 (15 CRM) | “Three categories of interventions were identified: training, tools, and organizational interventions.” “Studies show that team training can improve the effectiveness of multidisciplinary teams in acute (hospital) care.” Studies that presented high quality evidence were mostly simulation and CRM training. |

7 |

| Low et al26 (2018) | “To describe and evaluate the effects of team-training within intensive care medicine” and “to assess the quality of research and further describe the different team typologies, educational modalities, utilized curricula and the specific skills taught” | Exclusion criteria: “studies focusing on staff from outside the ICU (e.g., staff from emergency departments or medical students), education for individuals (not teams) and studies from non-English journals.” | Intensive care medicine | 27 (12 CRM) | “Team-training has been studied in multiple ICU team types, with CRM and TeamSTEPPS curricula commonly used to support teaching via simulation.” “Team-training in ICU is well received by staff, facilitates clinical learning, and can positively alter staff behaviors.” “Few clinical outcomes have been demonstrated and the duration of the behavioral effects is unclear.” |

8 |

| McCulloch et al27 (2011) | “To identify and evaluate evidence that training of healthcare workers in communication and teamwork improves job performance or patient outcomes.” | Inclusion criteria: randomized and nonrandomized studies; interventions with healthcare workers and healthcare teams. Exclusion criteria: in case “no training intervention was specified; no posttraining evaluation was performed beyond staff attitude and opinion surveys; if it was impossible to define the study population; and in case of lack of numerical data on outcomes.” |

Healthcare | 14 (14 CRM) | “The evidence for technical or clinical benefit from teamwork training in medicine is weak. There is some evidence of benefit from studies with more intensive training programmes (...).” “Most reported improved staff attitudes, and significantly better teamwork after training.” |

10 |

| Weaver et al28 (2014) | “To provide an updated narrative synthesis of the body of evidence evaluating team-training in acute care settings (...).” | Inclusion criteria: articles between January 2000 and December 2012. Exclusion criteria: articles that were “only descriptive in nature; conducted in non-English–speaking populations or if primarily targeting students or trainees.” |

Acute care setting | 26 (9 CRM) |

The “synthesis suggests that there is moderate to high-quality evidence that team-training can positively impact healthcare team processes and, in turn, clinical processes and patient outcomes.” “A key finding is that the studies demonstrating the most robust evidence for effectiveness have implemented team-training as a bundled intervention (...).” |

8 |

RESULTS: PHASE 1: UMBRELLA REVIEW OF CRM LITERATURE REVIEWS

Quality of the Literature Review

Upon pulling together the literature reviews conducted on CRM in healthcare to date and conducting our umbrella review of such work, it became apparent that there is a strong variation between how the 16 literature reviews were conducted and documented. Only 9 of the 16 reviews presented a flowchart that shows the process from initial search until the final set of articles in detail.7,11,12,16,17,22–24,26,27 Others gave a short description of this process.25 Likewise, 2 reviews did not present the full summary table of the selected articles and instead only provided a selection of information.18,19 These and other factors are reflected in the AMSTAR rating, which varies between 3 and 10 with Gross et al11 (2019), McCulloch et al27 (2011) and O’Connor et al19 (2008) receiving the highest AMSTAR scores.

Overall Findings

Table 1 provides a summary of the 16 CRM literature reviews included within our umbrella review. This table highlights some of the key areas of consensus across all the reviews. For instance, all of the reviews provide evidence of the positive effects of CRM on participant reaction, knowledge, attitude, skills, behavior, learning, transfer of knowledge to workplace, safety culture, and teamwork (e.g., communication, coordination) within the healthcare setting. However, although, at a high level, the positive effects of CRM exist, the picture is far from universal across all 16 literature reviews. For instance, the review by Salas et al20 (2006) suggests that the impact of teamwork training is mixed. Even those who found evidence of benefits of CRM were of varying strengths. For instance, O’dea et al7 (2014) suggest that CRM had large effects on knowledge and behavior and a small effect on attitudes. In comparison, O’Connor et al19 (2008) found that the strength of the relationship with attitudes and behaviors was large while the effect with knowledge was only medium.19

Building upon these mixed results, Table 1 also provides insights into other areas of heterogeneity among the reviews. To start, there is substantial variability in the number of studies included in each review (range from 7 to 64 underlying articles). In part, this variability may be the result of the target group examined within each review—from no limitation or all healthcare settings to a specific healthcare setting (e.g., acute care, hospitals), department (e.g., emergency department), or team (e.g., interprofessional teams). Likewise, what CRM entails varies across these various reviews to include techniques such as CRM training, simulation training, simulation crisis resource management training, and classroom-based CRM training.

Synthesis of Themes

Based on our review of the 16 CRM reviews conducted to date, we have identified a variety of issues that raise questions concerning whether any of these reviews provides a complete picture of the CRM literature. Looking closer, we found 3 clusters of ambiguity: in definition of CRM, in outcomes, and in information.

Definition Ambiguity

As each literature review focuses mainly or partly on CRM, it could be expected that a clear description of what CRM entails was presented. Table 2 provides an overview on how the 16 literature reviews described CRM. This table indicates that CRM typically covers competences like knowledge, skills and attitude, and topics such as teamwork, leadership, situation awareness, decision making, and communication. At the same time, Table 2 demonstrates that there is no clear standard set of competencies or topics that CRM should address. Gross et al11 (2019) show a list of key words that are used to describe CRM (e.g., communication, situational awareness, leadership, teamwork, decision making, briefing). However, there is a lack in operationalization of terminology, and therefore, it seems that a universal definition of CRM does not exist. This causes a considerable gap in knowledge about what CRM includes and which elements are the ones that precisely alter behavioral processes and subsequently improve patient safety. Most of the selected literature reviews do not address this issue and circumvent this by pretending that there is consensus about what CRM training interventions actually entail. Interestingly, only 7 of the 16 literature reviews included a description of the CRM training in their summary of the results.7,11,18,20,26–28 These descriptions show us that CRM curricula vary significantly. McCulloch et al27 (2011) suggest that the instructional methods of CRM training could consist of classroom-based methods only, or leverage simulation-based methods only, or a combination of both. O’dea et al7 (2014) provide insights from the standpoint of variation in training time between different methods. Information-based methods, such as lectures, vary between 1 hour and 1 day. Practice-based methods, such as a simulation, vary between 2 hours and 1 day. Although most CRM training interventions had a 1/2- or 1-day format,11 they can last up to 2 or 3 days.31–33 Recently, Gross et al11 (2019) explicitly addressed the issue of a lacked shared definition by showing that less than half of the studies in their systematic review provided information that would allow the CRM intervention to be replicated. In addition, they suggested minimum requirements for describing the intervention design (i.e., aims, methods, contents) in future CRM articles.

TABLE 2.

Descriptions of the CRM Concept

| Authors (Year) | Description of CRM Within Review |

|---|---|

| I. Reviews that focus on CRM | |

| Boet et al16 (2014) | “The ultimate goal of all CRM simulation training is to increase patient safety and result in better patient outcomes.” |

| Fung et al17 (2015) | “CRM includes clinical as well as communication and team-working abilities. CRM refer to principles such as leadership and followership, communication, teamwork, resource use, and situational awareness.” |

| Gross et al11 (2019) | Salas et al30 (1999) defined CRM training as a “a family of instructional strategies designed to improve teamwork in the cockpit by applying well-tested training tools (e.g., performance measures, exercises, feedback mechanisms) and appropriate training methods (e.g., simulators, lectures, videos) targeted at specific content (i.e., teamwork knowledge, skills, and attitudes). The purpose of CRM in high-risk organizations can be summarized as error countermeasures with three lines of defense: (1) avoidance of error, (2) trapping incipient errors before they are committed and (3) mitigating the consequences of those errors which occur and are not mitigated.” |

| Maynard et al18 (2012) | Possible CRM training components: patient safety overview within healthcare, role of CRM in other industries and within healthcare to address safety, communication, normalization of deviance, ingredients for effective teamwork, conflict, team briefings, team debriefings, assertiveness, situational awareness, shared mental models, red flags, and decision making. |

| O’dea et al7 (2014) | “The purpose of CRM training is to promote safety and enhance efficiency through optimum use of all available resources: equipment, procedures and people. The focus of CRM training is not on technical skills but rather cognitive and interpersonal skills, such as communication, situational awareness, problem solving, decision making, leadership, assertiveness and teamwork. Training is usually designed to develop generalizable, transportable teamwork competencies that learners can apply across different settings and teams. Instructional methods include: information-based methods (e.g., didactic lecture); demonstration-based methods (e.g., behavioral modeling, videos); and practice-based methods (e.g., simulation, role playing).” |

| O’Connor et al19 (2008) | CRM training can be defined as “a set of instructional strategies designed to improve teamwork in the cockpit by applying well-tested tools (e.g., performance measures, exercises, feedback mechanisms) and appropriate training methods (e.g., simulators, lectures, videos) targeted at specific content (i.e., teamwork knowledge, skills, and attitudes) (Salas et al, 1999, p.163).30” “An introductory CRM course is generally conducted in a classroom for 2 or 3 days. Teaching methods include lectures, practical exercises, role playing, case studies, and video of accident re-enactments. CRM courses typically cover core topics such as teamwork, leadership, situation awareness, decision making, communication, and personal limitations.” |

| Salas et al20 (2006) | “CRM is an instructional strategy that trains crews to effectively use all of their available resources (i.e., people, equipment, and information). CRM training has been defined as a set of “instructional strategies designed to improve teamwork in the cockpit by applying well tested training tools (e.g., performance measures, exercises, feedback mechanisms) and appropriate training methods (e.g., simulators, lectures, videos) targeted at specific content (i.e., teamwork knowledge, skills, and attitudes)” (Salas et al, 1999, p.163).30” “… it can be conceptualized as a team training strategy focused on improving crew coordination and performance.” |

| Verbeek-van Noord et al12 (2014) | “CRM typically includes educating teams about the limitations of human performance. Operational concepts include inquiry, seeking relevant operational information, assessing personal and peer behavior, communicating proposed actions, conflict resolution, and decision making.” |

| Zeltser and Nash21 (2010) | Not clear. |

| II. Reviews that focus on simulation | |

| Doumouras et al22 (2012) | “Simulation-based crisis resource management (CRM) training using a realistic computer-controlled mannequin is believed to be a useful strategy for teaching team-based skills. This methodology allows for repeated instruction and deliberate practice while posing no threat to patients.” |

| Murphy et al23 (2015) | “It (referring to simulation) is based on the experiential learning theory which provides devices, staff, virtual environments and contrived situations that replicate the clinical environment and events that arise in professional situations.” |

| Tan et al24 (2014) | Not clear. |

| III. Reviews that focus on team training in general | |

| Buljac-Samardzic et al25 (2010) | “CRM encompasses a wide range of knowledge, skills, and attitudes including communication, situational awareness, problem solving, decision making, and teamwork.” |

| Low et al26 (2018) | “Crew resource management (CRM) is an educational curriculum that was initially developed for the aviation industry to improve safety, communication and decision making. CRM was adapted to healthcare when patient simulators were used in anesthesia training programs and highlights five essential core concepts: team structure, leadership, situational awareness, mutual support and communication.” |

| McCulloch et al27 (2011) | Not clear. |

| Weaver et al28 (2014) | “A specific team-training strategy focused on developing a subset of teamwork competencies including hazard identification, assertive communication and collective management of available resources.” |

Outcomes Ambiguity

In addition to the lack of consistency regarding the conceptualization of a CRM training, there also seems to be a lack of agreement regarding the impact of CRM interventions in terms of the relationship between CRM programs and the impact of such an intervention on a variety of outcomes.7 As suggested previously, the 16 literature reviews included in our umbrella review seem to present a clear picture that CRM has a positive effect on outcomes. However, when we look across different outcomes, there are different results. Namely, the impact of a CRM training is especially clear at Kirkpatrick’s hierarchy evaluation level 1 (i.e., reaction) but lacks consistency when looking at level 2 (i.e., learning) and level 3 (i.e., behavior).7,19 Likewise, it is widely debated whether CRM training has an effect on the bottom line: performance outcome such as improvement in specific patient safety outcomes (Kirkpatrick’s level 4). The review by Salas et al20 (2006) states that the evidence included in their review is mixed.20 As a result, some suggest that the relationship between CRM and patient safety is not yet proven. Others, however, point out that there are a couple of studies that have shown CRM to have a beneficial effect for patients but also recognize the limitations regarding the conceptualization and the quality of evidence.11,16,17

An underlying issue is that the variety of outcome measures that have been examined within CRM research is challenging to fit precisely into Kirkpatrick’s categories, which resulted in alterations such as splitting level 2 into attitude (2a) and knowledge/skills (2b) or including marks (e.g., *) that represents deviations such as using qualitative evaluation methods (instead of quantitative), as well as varying the time at which outcomes are measured (i.e., right after the training intervention or after a delay). Nevertheless, only 5 of the 16 literature reviews clearly present the measures used in their findings.7,11,12,17,18,27 Such a sentiment was shared by Gross et al11 (2019) who suggested minimum requirements for describing the evaluation (i.e., method of evaluation, sample group size, statistical data, outcomes) for future CRM articles.11

Information Ambiguity

As detailed in Table 1, many of the reviews conducted to date have focused on the relationship that CRM training interventions have on various outcome metrics. However, there is a lack of information provided in the literature reviews conducted thus far regarding the first and last step in this process: implementation of CRM and sustaining the effects. The review conducted by Verbeek-van Noord et al12 (2014) is the only review that presented information on the implementation strategy. In addition, Gross et al11 (2019) discussed studies with an implementation strategy.11 Similarly, only Tan et al24 (2014), Verbeek-van Noord et al12 (2014), and O’dea et al7 (2014) explicitly address the sustainability of results as they highlight the period over which the effect of CRM was measured. This is unfortunate given that multiple reviews acknowledge the need for more evidence regarding the sustainability of CRM initiatives (e.g., the study by Maynard et al18). In addition, Gross et al11 (2019) emphasize the importance of considering training conditions to include factors such as the trainer qualification and the number of participants.11

Measures to grade the level of evidence or the methodological quality could help make a judgment regarding an article. The level of evidence of the selected CRM articles by the reviews is often not quantified. Tan et al24 (2013) and McCulloch et al27 (2011) are the only ones to address the quality of evidence per study. Tan et al24 (2014) even conclude that all the selected articles (on multidisciplinary simulation training) in their review present a low quality of evidence.

Conclusion Phase 1

Most of the 16 selected reviews base their conclusion on different domains in healthcare. This contributes in part to the interesting finding that within these reviews, there is a lack in overlap between the 16 literature reviews regarding the presented studies. When looking across the 16 reviews, if one were to merge the studies reviewed, it would result in 274 articles in total with 190 of these articles being unique. By digging into the reviews that have been conducted to date, only 17 of the articles were included within 3 or more of the reviews, only 49 of these 190 articles were actually presented by 2 or more reviews, and the remaining 141 articles were presented in only 1 review. Recently, the systematic literature review conducted by Gross et al11 (2019) seems to present the most comprehensive overview of the CRM literature. However, although more comprehensive than others, within their review, only a third of the articles included overlap with the other 15 reviews. Because of the high level of heterogeneity of the present literature reviews, the need to present one overall review is still present. As a result, within phase 2, we conducted our own literature review of the healthcare CRM literature with the aim of being more comprehensive than any single review conducted to date.

METHODS: PHASE 2: COMPREHENSIVE CRM LITERATURE REVIEW

As a result of the conclusion of phase 1, we conducted a new literature review on CRM in healthcare with the aim of providing the most comprehensive review of this literature stream to date and thereby filling several of the identified gaps noted during our umbrella review (i.e., phase 1).

Search Strategy

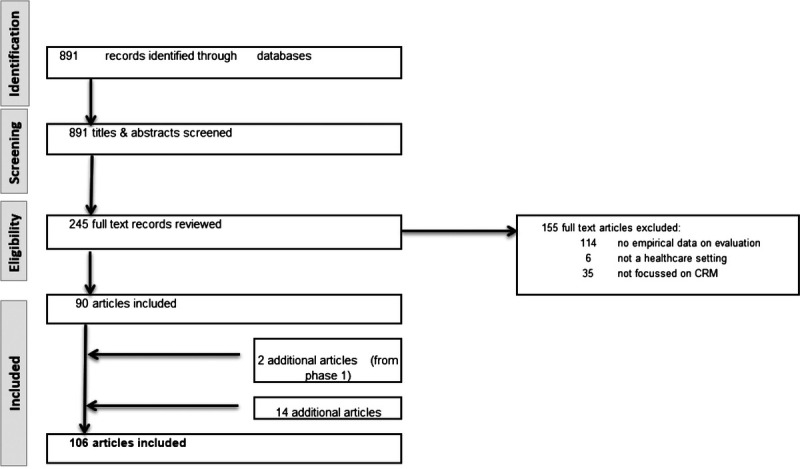

First, we searched the following databases for CRM articles: PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search involved a combination of the key words “CRM” OR “crew resource management” OR “crisis resource management” and was restricted to articles from 2006 (see Appendix 2, http://links.lww.com/JPS/A377). This search strategy resulted in 891 hits. First, similar to the process used in phase 1, 2 of the authors evaluated the title and abstract by adhering to the inclusion and exclusion criteria highlighted hereinafter and then following this with the full-text evaluation by way of the same criteria (Fig. 2). This resulted in 90 articles. Second, the presented articles within the 16 literature reviews (phase 1) were extracted and also evaluated according the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This second step resulted in 2 additional articles. Third, snowball research was applied by analyzing the included articles and their reference lists, which added 14 articles. In total, 106 articles were included.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart phase 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles were included if they examined CRM interventions within healthcare and did so by leveraging empirical analysis. In contrast, articles were excluded if they (1) did not cover a CRM intervention, but for example, a related intervention such as TeamSTEPPS or in case results could not be tracked backed to the CRM intervention because it was only 1 element of a bigger intervention; (2) did not present empirical data on the evaluation of CRM, but for example, only described the development of a CRM intervention or only focused on the educational improvement of CRM training; or (3) did not focus on healthcare organizations but on the profit sector or on educational institutions. However, the actual content of the CRM intervention was not considered as an inclusion or exclusion criterion. If the authors themselves referred to CRM, it was included. In addition, we did not consider methodology (e.g., quantitative, experimental, qualitative) as an exclusion criterion.

Analysis

The 106 articles were summarized in Table 3 by author, year, aim of the study, setting, study design, main results as well as the Kirkpatrick’s level of outcome, implementation strategy (yes or no), and sustainability strategy (yes or no). In addition, the quality of the evidence was evaluated by MMAT (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool). MMAT allows an assessment of methodological quality (quality of reporting) of all articles, regardless of their methodology. Although the criteria differ for each type of research, each domain for quantitative and qualitative research includes 4 criteria. The final score for each article depends on the number of criteria met and can vary from 25%, 50%, 75%, to 100% if all criteria are met. For mixed method research studies, the calculation of the final score is a little different and depends on the quality of the weakest component (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method).136

TABLE 3.

Summary Included Articles Phase 2

| Authors (Year) | Main Aim of Study | Setting | Study Design | Main Results | Impl. Strategy | Sust. Strategy | Kirkpatrick Level | MMAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allan et al34 (2010) | To evaluate the implementation of a multidisciplinary in situ pCICU–CRM training program on comfort and confidence levels among participants involved in resuscitation events | pCICU | Pre-post survey | > Participants found course useful and realistic, found themselves better prepared to participate in and to lead resuscitation events, felt more confident, had a lower anxiety level to participate in events, and reported to be more likely to raise concerns about inappropriate management to team leader | No | No | 1, 2 | 100% |

| Atamanyuk et al35 (2013) | To evaluate the face validity of an affordable and realistic tool for interprofessional CRM training, and the impact on communication skills | Pediatric ICUs | Pilot study | > High face validity of the scenario, the model, and the content > High impact on practice, teamwork, and communication |

No | No | 1, 2, 3* | 25% |

| Ballangrud et al36 (2014a) | To describe intensive care nurses’ perceptions of simulation-based team training based on CRM for building patient safety in the ICU | ICUs | Qualitative design based on individual interviews | > Participants experienced that the training created awareness about clinical practices and acknowledged the importance of structured teamwork for patient safety > Realistic training makes nurses more prepared to provide care |

No | No | 1, 2 | 100% |

| Ballangrud et al37 (2014b) | To investigate intensive care nurses’ evaluations of simulation-based team training based on CRM | ICUs | Post survey | > Participants were highly satisfied with current learning in the training and scored also high on self-confidence in learning | No | No | 1, 2 | 100% |

| Bank et al38 (2014) | To evaluate the effects of a short, needs-based pediatric CRM simulation workshop with postactivity follow-up on recognizing common errors in teamwork and improving perceived abilities to manage pediatric patients | Pediatric emergency medicine department | Pre-post survey and pre-post video assessment | > Participants improved the abilities to manage the medical and team functioning—related issues in pediatric resuscitation > Improvement in identification of CRM errors |

No | Yes | 1, 2, 3 | 100% |

| Batchelder et al39 (2009) | To examine a specific element of the training and to measure and quantify changes in performance | Prehospital emergency medicine | Beginning and end of the course video evaluation and pre-post survey | > Increase in time from arrival to inflation of tracheal tube cuff > Decreased number of safety critical events > Higher CRM behavior scores > Increased confidence in prehospital anesthesia competencies |

No | No | 2 | 100% |

| Blackwood et al40 (2014) | To examine the effect of a brief CRM teaching session on pediatric advanced life support, CRM skills, resuscitation, and teamwork behavior | Pediatric hospital | Prospective randomized control pilot study | > Intervention group placed monitor leads earlier, placed an IV sooner, called for help faster, and checked for a pulse after noticing a rhythm change quicker > Intervention group had higher crisis resource management performance scores |

No | No | 3* | 100% |

| Budin et al41 (2014) | To describe changes in perinatal nurse and physician caregiver perceptions of teamwork and safety climate after a 6-mo CRM training program | Perinatal units | Pre-post survey | > Improvement in nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions of teamwork and safety climate > Both groups improved |

Yes | Yes | 2 | 100% |

| Burden et al42 (2014) | To compare simulation versus lecture teaching CRM skills and its effect on performance | Internal medicine | Randomized control pre-post study | > Simulation intervention improved team communication and cardiopulmonary arrest management | No | No | 2, 3* | 100% |

| Carbo et al43 (2011) | To evaluate residents’ patient safety attitudes and knowledge after an adapted CRM curriculum from other settings to internal medicine | General medicine units | Pre-post survey | > Improvement in knowledge about key skills of team training > Improvement in assertiveness > Increased likeliness to fill out an incident report for a near miss |

No | No | 1, 2, 3* | 75% |

| Carpenter et al44 (2017) | To research the effect of CRM-based medical team training on creating open, yet structured, communication | OR | Pre-post survey and checklist documentation | > Improvement in job satisfaction, safety climate, and working conditions > Improvement to adherence to checklist |

Yes | Yes | 2, 3 | 50% |

| Castelao et al45 (2011) | To evaluate the effect of video-based CRM training on no-flow time and proportions of team member verbalizations | Students | Randomized control trial | > CRM training reduced no-flow time, improved team leader verbalization, and improved follower verbalization in the category unsolicited information | No | No | 3 | 100% |

| Castelao et al46 (2015) | To assess the impact of CRM team leader training (compared with ALS training) on CPR performance and team leader verbalization | Students | Prospective randomized controlled study | > CRM team leader training had higher ADH scores, team leader verbalizations, but not significantly shorter no-flow time | No | No | 3 | 100% |

| Catchpole et al47 (2010) | To examine the effect of aviation-style team training on surgical teams and to examine the organizational and social context in which the observable changes take place | OR | Pre-post observations, pre survey, and ethnographic observation | > Increased number of stop-checks, briefings, and debriefings > Intraoperative teamwork was not unequivocally improved |

Yes | No | 2, 3 | 100% |

| Chan et al48 (2016a) | To evaluate how healthcare professionals perceive a simulation team-based CRM program | High-risk hospital departments | Post survey | > High scores on overall satisfaction with program, the applicability of the program, and the high standard and expertise of the trainers > Most participants would recommend the program to colleagues |

No | No | 1 | 100% |

| Chan et al49 (2016b) | To evaluate participant reactions and attitudes to CRM teamwork classroom-based training and exploring potential differences in attitudes across the different healthcare professionals | Multiple hospital departments | Pre-post survey and a second post survey | > Positive effect on human factors attitude of frontline professionals > Nurses showed a greater positive shift in attitudes toward patient safety than doctors > Participants found the CRM classroom-based training program useful, relevant, and interesting |

No | No | 1, 2 | 75% |

| Ciporen et al50 (2018) | To evaluate participants on performance metrics and teamwork dynamics and to evaluate CRM-based simulation at the end of the experience | Neurosurgery and anesthesiology | Pre-post survey and observations | > Participants overall agreed that the simulation was realistic, clinically applicable, and useful. No differences were found between disciplines > The simulation was found useful in facilitating improved understanding of relevant anatomy |

No | No | 1, 2 | 75% |

| Clarke et al51 (2014) | To measure the development of NTSs over time | Emergency medicine | Observational longitudinal cohort study | > Improvements over time on Ottawa GRS between year 1 and 2, but no significant improvement between year 2 and 3 | No | No | 3* | 100% |

| Clay-Williams et al52 (2013) | To test the effectiveness of classroom- and simulation-based CRM training alone or in combination, in improving the teamwork attitudes and behaviors of healthcare professionals | Acute hospital settings | Randomized controlled trial, pre-post survey, another post survey, and post hoc observations | > Reaction to classroom training was universally positive (to simulation training was not measured) > Improvements in knowledge and teamwork behavior after classroom training > No impact of additional simulation training next to classroom training > No improvement in teamwork attitude after classroom, simulation, or combination training |

No | No | 1, 2 | 50% |

| Clay-Williams et al53 (2014) | To explore the potential for modularized CRM training to interprofessional healthcare workers | Hospital | Pre-post surveys | > Workshops met the needs of participants and provided interprofessional learning experience and practical skills > Barriers were identified for implementing learned tools/strategies |

No | No | 1, 2, 3* | 100% |

| Clay-Williams and Braithwaite54 (2015) | To test the effectiveness of classroom- and simulation-based CRM courses (alone and in combination), and identify organizational barriers and facilitators to implementation of team training programs in healthcare (process evaluation of Clay-Williams et al,52 2013) | Acute hospital settings | Randomized controlled trial, pre-post interviews, and post implementation interviews | > Improvement in knowledge and teamwork behavior after classroom training > Facilitators and barriers (i.e., hospital time and resource constraints and poor organizational communication) for implementation were identified |

Yes | No | 1, 2, 3 | 100% |

| Cooper et al55 (2008) | To compare the safety climates between departments and to assess the impact of the simulation-based CRM training on safety climate | Anesthesia departments | Pre-post survey | > Different climate scores among hospitals, no difference between the trained and untrained | No | No | 2 | 75% |

| Coppens et al56 (2018) | To investigate (i) whether integrating a course on CRM principles and team debriefings in simulation training, increases self-efficacy, team efficacy, and technical skills of nursing students in resuscitation settings and (ii) which phases contribute the most to these outcomes | Nursing students | Randomized controlled trial, pre-post survey, and observations | > Improvement in self-efficacy and team efficacy in the intervention group, while the control group only showed improvement on team efficacy > The debriefing phase contributes most to these effects |

No | No | 2, 3 | 100% |

| De Korne et al57 (2014) | To evaluate the implementation of a broad-scale TRM program on safety culture | Eye hospital | Pre-post interviews and observations | > Increasing safety awareness and social team interaction > Increased number of reported near incidents > Stabilization of number of wrong-side surgery to a minimum (after reduction) |

Yes | No | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 100% |

| Duclos et al58 (2016) | To assess the impact on major surgical complications of adding a CRM-based team training program after checklist implementation | OR | Cluster randomized trial, case reports on adverse events and compliance of checklist use | > Improvement in surgical outcomes (i.e., major adverse events), with no difference between trial arms across intervention and control hospitals | No | No | 4 | 100% |

| Emani et al59 (2018) | To research the effect of low-fidelity simulation-based crisis resource management CRM training on team performance (in low-resource setting) | pCICU | Pre-post questionnaire and observations | > Improvement in team dynamics and performance > Decrease in time to intervention > Increase in frequency of closed loop communication > No difference in performance |

No | No | 3 | 100% |

| Falcone et al60 (2008) | To evaluate the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary trauma training program (that emphasizes CRM training techniques) on team performance | Pediatric trauma care | Beginning to end of the study observations | > Improvement in overall performance (appropriate and timely care) and performance of specific resuscitation domains | Yes | No | 2 | 100% |

| Fore et al61 (2013) | To assess the impact of sterile cockpit principle on interruptions and distractions (during high-volume medication administration) and number of medication errors | Medical oncology unit at VA Health System | Pre-post design for medical error rates and post design for distractions | > Decrease in interruptions or distractions > Reduction in medication error rate |

Yes | No | 3, 4 | 100% |

| France et al62 (2008) | To evaluate the impact of CRM training on team compliance with perioperative safety practices | Surgical departments | Observational study | > Compliance with 60% of integrated safety and CRM practices > Compliance scores showed a downward trend over time |

Yes | No | 3 | 100% |

| Fransen et al63 (2017) | To investigate whether simulation-based obstetric team training focusing on CRM in a simulation center improves patient outcome | Obstetric units | Cluster randomized controlled trail | > The composite outcome of obstetric complications did not differ between intervention and control groups > In the intervention group damage due to shoulder dystocia was reduced and invasive treatment for severe postpartum hemorrhage was increased |

No | No | 4 | 100% |

| Gallagher64 (2016) | To evaluate a CRM follow-up program on long-term goals | Mother-baby and labor and delivery | Pre-post survey | > Improvement in most safety culture measurements > Improvement in hand hygiene (for labor and delivery) > Mixed results on improvement patient satisfaction |

Yes | Yes | 3*,4 | 100% |

| Gillespie et al65 (2017) | To evaluate the effect of a brief team training intervention on teams’ observed NOTSS | OR | Pre-posttest interrupted time series design (pre-post observation) | > Improvements in mean NOTECHS scores across the pre-posttest phases | No | No | 3 | 100% |

| Gillespie et al66 (2017b) | To evaluate a brief team training program in relation to teams’ observed NTSs in surgery, teams’ perceptions of safety culture, and the training implementation | OR | Mixed-methods design, including structured observations, a survey, and semistructured interviews | > Improvements in NTSs and in the use of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist > No improvement in teamwork > Nonsignificant increase in safety climate and decrease in teamwork climate > Most participants agreed that the program highlighted the important role of individual and shared SA in identifying and managing risk |

No | No | 1, 2, 3 | 100% |

| Gillman et al67 (2015) | Describe the trauma multidisciplinary crisis resource course titled S.T.A.R.T.T. (Simulated Trauma and Resuscitative Team Training) | Trauma teams | Post study and observations | > High satisfaction of participants > Improvement in Ottawa GRS > No significant improvements in Advanced Trauma Life Support checklist |

Yes | No | 1, 3* | 100% |

| Gore et al68 (2010) | To evaluate the perceived efficacy of CRM initiatives | OR | Pre-post survey | > Improvement in reporting errors (only 2 questions) and patient safety climate (only 2 questions) > No improvement in teamwork |

Yes | No | 2 | 75% |

| Gross et al69 (2019b) | To establish the feasibility of chunking CRM training into microsize interventions and to compare different training approaches in the context of microlearning | Medical students | Pre-post survey and observations | > Both groups (i.e., example and lecture) showed most of the behaviors included in the instructional videos during the simulations and were able to recollect them > The didactic concept of the instruction caused a difference between the learning success of the groups |

No | No | 1, 2 | 100% |

| Guerlain et al70 (2008) | To measure the effect of CRM strategies on the resultant use and perceived utility | OR | Pre-post survey | > Increasing frequency of preoperative briefing elements > Using briefings practices correlates highly with respondents’ perceptions of communication, teamwork, and potential for reducing errors |

No | No | 2, 3* | 75% |

| Haerkens et al31 (2015) | To assess the effects of CRM implementation on outcome in critically ill patients | ICU | Preimplementation-post design for outcome measures, preimplementation survey design, and observations in implementation period | > Reduction of incidence of predefined complications > Reduced standardized mortality rate > Improvement in safety climate |

Yes | Yes | 2, 3, 4 | 75% |

| Haerkens et al71 (2018) | To assess the effects of CRM implementation on safety climate and time spent in the trauma room, and on hospital length of stay and 48-h crude mortality of trauma patients. | Emergency department | Pre-post implementation design for outcome measures (with control group) and surveys | > Improvement in safety climate (i.e., teamwork climate, safety climate, and stress recognition) and decrease perceptions of management > Job satisfaction and working conditions did not change > Length of stay increased > Mortality rate was unchanged |

Yes | Yes | 2, 4 | 100% |

| Haffner et al72 (2016) | To assess a CRM training program on the correction rate of improperly executed chest compressions and communication quality in a simulated cardiac arrest scenario | Medical students | Randomized study, pre-post survey, and pre-post observations | > Team leaders corrected improper chest compressions more often compared with the control group > Improvement in communication quality compared with the control group |

No | No | 2, 3 | 100% |

| Haller et al73 (2008) | To assess the effect of a CRM intervention on teamwork and communication skills in a multidisciplinary obstetrical setting | Labor and delivery unit | Pre-post survey | > Better understanding of teamwork and shared decision making in emergency situations > Improvement in team and safety climate and stress recognition |

No | No | 1, 2 | 75% |

| Hänsel et al74 (2012) | To evaluate the influence of a CRM course on situational awareness and medical performance in crisis scenarios and to compare the results with the effects of a purely clinical simulator training | Medical students | Randomized controlled trial, pre-post design with assessment tool | > The simulator training nor the CRM course influenced clinical performance > Situational awareness improved only after simulator training, not after CRM training |

No | No | 1, 2 | 75% |

| Hansen et al75 (2007) | To assess the educational benefit of a CRM training and whether the damage control techniques are used in daily practice | OR | Pre survey and another post survey | > Increase of number of team members who felt comfortable performing damage control surgery with own role (particularly surgeons) > Roughly 50% of surgeons and OR nurses used damage control techniques in practice > Improvement in the ability to handle severely injured patients improved |

No | No | 1, 2, 3* | 75% |

| Hansen et al76 (2008) | To evaluate a team-oriented and CRM-based approach and its impact on trauma care | OR | Post survey | > Improvement in proficiency with damage control techniques > Team approach was perceived as crucial > Most hospitals reported modifying trauma protocols |

No | No | 1, 2, 3* | 75% |

| Hay et al77 (2016) | To evaluate implementation of a “sterile cockpit” methodology to reduce the number of distractions during procedures | Nursing staff of gastrointestinal endoscopy procedure | Pre survey and another pre-post survey and observations | > Improved awareness of distraction and its impact on patient safety > Reduction of interruptions to zero > While reducing distractions, perception of nursing quality of care improved |

No | No | 2, 3 | 75% |

| Hefner et al78 (2017) | To examine the impact of a systematic multihospital implementation of CRM on staff perceptions of patient safety culture | Hospitals | Pre-post survey | > Significant improvement in dimensions of patient safety culture perception; teamwork and communication dimensions may be more likely influenced by CRM training than supervisor and management dimensions | Yes | No | 2 | 75% |

| Hicks et al79 (2012) | To describe the development, piloting, and multilevel evaluation of CREW training for emergency medicine residents | Emergency department | Pre-post survey and pre-post observational | > The training is perceived to be useful, effective, and highly relevant > Unable to detect a difference in attitude and NTSs |

No | No | 1, 2 | 75% |

| Hughes et al80 (2014) | To describe the development, implementation, and effectiveness of a trauma resuscitation-focused CRM program | Trauma resuscitation | Pre-post survey and pre-post observational design | > Improvement in accuracy of field to medical command information, accuracy of emergency department medical command information to the resuscitation area, team leader identity, communication of plan, and role assignment > More likely to speak up in case of safety concerns |

No | No | 1, 2, 3 | 75% |

| Jankouskas et al81 (2007) | To evaluate improvement in the NTSs of a multidisciplinary team of pediatric residents, anesthesiology residents, and pediatric nurses after participation in the CRM educational program | Pediatrics | Pre-post survey and observations | > Improvement in perceived collaboration, satisfaction with care, and teamwork skills > No significant improvement in situation awareness, decision making, and task management |

No | No | 2, 3 | 75% |

| Jankouskas et al82 (2011) | To evaluate CRM training (in combination with basis life support) during a simulated patient crisis | Nursing and medical students | Experimental pre-post study | > Experimental teams compared with control teams: improvement in team process > Both experimental and control teams showed improvements in team effectiveness |

No | No | 3, 4 | 75% |

| Kemper et al83 (2014) | To examine the impact of pretraining readiness factors and posttraining barriers and facilitators on follow-up on plans of action | ICUs | Pre-post survey | > Perceived barriers and facilitators after CRM training is related with taking action > Readiness factors were positive related to taking action, only when assessed together and not separately > Support of the management for patient safety before the training is a positive determinant of the number of perceived facilitators |

Yes | No | 2, 3* | 100% |

| Kemper et al32 (2016) | To assess the effectiveness of a classroom-based CRM training in ICU | ICUs | Controlled trail, pre-post survey with mixed method data | > Improvement in behavior aimed at optimizing situational awareness (based on survey, not observation) > Improvement in error management culture, job satisfaction, and patient safety culture (also in control group) > Patient outcome and situational awareness attitude were unaffected |

Yes | No | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 100% |

| Kuy and Romero et al84 (2017a) | To determine whether rates of CITN patient safety adverse events change after CRM training | Surgery (VA) | Pre-post outcome measures | > Complete compliance to performance of briefings and debriefings after CRM training > Decrease of CITN events to zero after CRM training |

Yes | No | 3, 4 | 100% |

| Kuy and Romero et al85 (2017b) | To describe implementation of CRM in a VA Surgical Service and to assess whether staff CRM training is related to improvement in staff perception of a safety climate | Surgery (VA) | Pre-post survey | > Improvement in safety climate | Yes | Yes | 2 | 75% |

| LaPointe86 (2012) | To observe the impact of aviation-based CRM training on the safety attitudes of perioperative (surgical) personnel | OR | Quasi-experimental pre-post survey | > Improvements in most of the safety attitudes > No reduction of error rate and safety culture |

No | No | 2, 4 | 100% |

| Lehner et al87 (2017) | To establish interdisciplinary simulation-based team training as a tool to improve the care of trauma patients in the pediatric surgery trauma room | Pediatric emergency department | Pre-post survey and another post survey | > The course was evaluated as very realistic and relevant to the daily routine, detailed debriefings were evaluated as positive > Participants reported improvement in technical and/or medical skills (i.e., cardiopulmonary resuscitation) and NTSs (i.e., setting priorities) |

No | No | 1, 2 | 50% |

| Mah et al88 (2009) | To evaluate mannequin-based simulations (using multidisciplinary teams of clinicians) | ICU | Pre-post (real time) observation and pre-test | > Positive relation of knowledge of sepsis guidelines and proportion of task completion, but correlations between specific tasks and related questions showed no relationship to knowledge | No | No | 2, 3 | 75% |

| Mahramus et al89 (2016) | To assess the effectiveness of a 2-h teamwork training program | Cardiopulmonary arrest (code) team | Quasi-experimental design, pre-post survey, pre-post observations | > Improvement in perception and observation of teamwork > Program was evaluated positively |

No | No | 1, 2, 3 | 75% |

| Man et al90 (2019) | To investigate the impact of locally adopted simulation-based CRM training on participants’ perceptions and knowledge | OR and general | Pre-post survey | > Most participants reported the training to be useful and relevant in daily practice > Improvement in perception and knowledge after 1-mo postcourse but declined after 1-y postcourse |

No | No | 1, 2 | 75% |

| Mancuso et al91 (2016) | To assess the effectiveness of CRM training and interventions on communication | Labor and delivery | Pre-post observation | > Improvement in quantity and quality of communication | Yes | No | 3 | 100% |

| Marshall and Manus92 (2007) | To examine the cultural impact of a CRM-based Human Factors in Healthcare Demonstration Project | Surgery | Pre-post survey | > Overall improvements in patient safety awareness and the quality of team-based behaviors and performance | Yes | Yes | 2, 3 | 100% |

| McCulloch et al13 (2009) | To assess the effect of aviation-style NTS training on the number of potentially significant errors and mishaps with potential for harm to patients and clinical outcome measures | OR | Pre-post observation, pre-post survey with clinical outcome measures | > Improvement in safety climate and nontechnical performance > Decreased operative technical error and nonoperative procedural errors > Operating time was unaffected and length of hospital stay not reduced significantly |

No | No | 2, 3, 4 | 100% |

| Mitchell and Dale93 (2015) | To assess the effect of a 1-d human factors (CRM) training program | Neurosurgical theater staff | Pre-post observation with side error rates | > Prelist briefing meetings were adopted and quickly became widely used > Postlist debriefing meetings were introduced but were not widely adopted > Mean time between side errors increased from 2 to 18 mo > After the training, no errors occurred in 82 mo |

Yes | Yes | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 75% |

| Moffatt-Bruce et al94 (2017) | To evaluate the costs and ROI of implementing a CRM program and to improve understanding about its financial impact | Hospitals | Retrospective analysis | > A 25.7% reduction in observed relative to expected events (725 fewer AEs) > Increased hospital savings from estimated reduction in avoidable events > Significant ROI from reduced adverse events over a 3-y period >The overall ROI for CRM training was in the range of $9.1–$24.4 million |

Yes | No | 4 | 100% |

| Morgan et al95 (2009) | To determine whether simulation-based debriefing and feedback improved performance of practicing anesthetists managing high-fidelity simulation scenarios | Anesthesiology | Prospective, randomized, controlled study | > Improvement of skills > Participants from the debrief group did not overall perform better than those in the control group > The effect of the educational intervention was still evident 6–9 mo later |

No | No | 3* | 100% |

| Morgan et al96 (2011) | To determine whether a high-fidelity simulation educational debriefing session improved the NTSs in the management of simulated anesthetic scenarios | Anesthesia departments | Pre-post observations | > No improvement in task management and team working > Improvement in situation awareness (only in the debrief group) and in decision making (for both groups) |

No | No | 3 | 100% |

| Morgan et al97 (2015) | To test the effectiveness of a combined SOP (standard operating procedures) and CRM-based teamwork training intervention to improve the quality, safety, and reliability of surgical team performance | Orthopedic surgery | Controlled interrupted time series with pre-post observations and clinical outcomes | > Improvement in NTS and WHO compliance > Glitch rates decreased in the intervention as control group > No significant effect on clinical outcomes |

No | No | 3, 4 | 100% |

| Müller et al98 (2007) | To establish and evaluate a CRM course combining psychological teaching with simulator training | Emergency department | Post survey | > All participants rated the course as good or very good > The psychological exercises were highly valued |

No | No | 1 | 75% |

| Müller et al99 (2009) | To evaluate the effect of 2 different simulator-based training approaches, CRM, and MED (classic simulator training), on performance and stress reduction of intensivists | ICUs | Randomized design, pre-post observation design, and pre-post saliva specimen | > Improvement in NTS and clinical performances in both CRM and MED group > Increased stress during the simulation, after the training stress (that is measured by salivary α-amylase) reduced |

No | No | 3 | 100% |

| Neily et al100 (2010a) | To evaluate to what degree skills taught through the CRM-based medical team training program are implemented and the impact on patient safety, processes of care, team functioning, and staff satisfaction | Surgery departments | Structured interviews | > Improvements in teamwork, safety, and efficiency > Most facilities implemented briefings and debriefings and an additional project > Sites with lower volume were more likely to conduct briefings/debriefings |

Yes | No | 1, 2, 3* | 100% |

| Neily et al101 (2010b) | To determine whether an association existed between the CRM-based medical team training program and surgical outcomes | OR | Retrospective mixed methods design with control group: structured interviews and mortality rates | >18% reduction of annual mortality rate compared with 7% in the control group > Decline in the risk-adjusted surgical mortality rate was approximately 50% greater in the intervention group compared with control group |

Yes | Yes | 3*, 4 | 100% |

| Nielsen et al33 (2007) | To evaluate the effect of CRM based teamwork training on the occurrence of adverse outcomes and process of care in labor and delivery | Hospital labor and delivery units | A cluster-randomized controlled trial, pre-post design for outcome measures | > No statistically significant differences between intervention and control group for outcome measures > Mean time elapsed between the decision to perform an emergency cesarean delivery and the time of the incision was shorter in the intervention group |

Yes | Yes | 4 | 75% |

| Nishisaki et al102 (2009) | To evaluate effectiveness on technical and behavioral skills and feasibility (logistics and finance) of a simulation-based orientation training | Pediatric critical care fellows | Post surveys | > Improvements in clinical performance and self-confidence | No | No | 1, 2, 3* | 50% |

| O’Connor et al103 (2013) | To develop and evaluate a CRM training program | Trainees | Pre-post survey, another post survey, and pre-post observations | > Improvement in knowledge > No improvement in speaking up about stress and behavior > Improvement in speaking up to seniors for in-between subject assessment |

No | No | 1, 2, 3 | 100% |