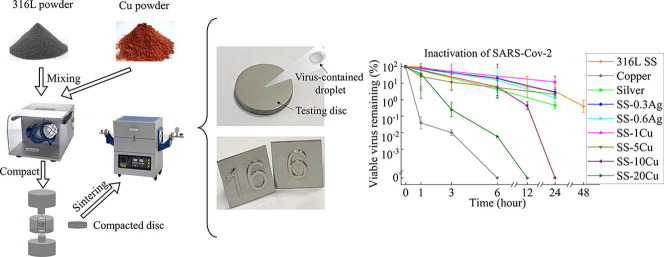

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Anti-pathogen, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, H1N1, Stainless steel

Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) exhibits strong stability on conventional stainless steel (SS) surface, with infectious virus detected even after two days, posing a high risk of virus transmission via surface touching in public areas. In order to mitigate the surface toughing transmission, the present study develops the first SS with excellent anti-pathogen properties against SARS-COV-2. The stabilities of SARS-CoV-2, H1N1 influenza A virus (H1N1), and Escherichia coli (E.coli) on the surfaces of Cu-contained SS, pure Cu, Ag-contained SS, and pure Ag were investigated. It is discovered that pure Ag and Ag-contained SS surfaces do not display apparent inhibitory effects on SARS-CoV-2 and H1N1. In comparison, both pure Cu and Cu-contained SS with a high Cu content exhibit significant antiviral properties. Significantly, the developed anti-pathogen SS with 20 wt% Cu can distinctly reduce 99.75% and 99.99% of viable SARS-CoV-2 on its surface within 3 and 6 h, respectively. In addition, the present anti-pathogen SS also exhibits an excellent inactivation ability for H1N1 influenza A virus (H1N1), and Escherichia coli (E.coli). Interestingly, the Cu ion concentration released from the anti-pathogen SS with 10 wt% and 20 wt% Cu was notably higher than the Ag ion concentration released from Ag and the Ag-contained SS. Lift buttons made of the present anti-pathogen SS are produced using mature powder metallurgy technique, demonstrating its potential applications in public areas and fighting the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens via surface touching.

1. Introduction

The transmission of pathogenic bacteria and viruses in public areas has been a long-standing issue for public health. Infectious diseases induced by these bacteria or viruses are not only afflicting millions of people annually but also causing an immeasurable economic cost [1], [2], [3]. In particular, the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is causing a global pandemic [1], [4]. Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) has suggested that large virus-laden droplets and direct or indirect contact with touching surfaces contaminated by respiratory secretions are critical paths for the COVID-19 to be transmitted from person to person [5], [6], [7]. Stainless steel (SS) products are used extensively in public areas such as hospitals, schools, and public transportations because of their excellent mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and workability [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Thus, SS is deemed as one of the most frequently touched materials for the public. Unfortunately, researchers have confirmed that conventional SS does not have antibacterial or antiviral properties [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. Notably, it has been reported that the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) exhibits strong stability on the surface of conventional SS, with viable virus detected even after three days [15], [18]. Undoubtedly, this has created a high possibility of virus transmission among humans in public areas.

As the two most popular inorganic antimicrobial elements, Ag and Cu have attracted significant research interests because of their low toxicity to animal cells and well-known ability to inactivate a broad spectrum of bacteria and viruses [15], [19], [20], [21], [22]. Studies have reported that Ag nanoparticles, some Ag-contained composites, copper, brass, and Cu-contained high-entropy alloy have antimicrobial properties [15], [23], [24], [25], [26]. In particular, it has been reported that pure Cu exhibits an excellent antiviral efficiency towards SARS-CoV-2 and H1N1 influenza A virus (H1N1) [15], [18], [27]. However, replacing SS products with pure Cu in public areas is impractical due to its high cost, low strength, and less corrosion-resistant capability. Some studies have introduced antimicrobial properties into conventional SS by surface coating or ion implantation [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]. Nevertheless, it is necessary to note that the thickness of coatings is limited (e.g., physical vapor deposition (PVD), cold-spray, and ion implantation, thickness < 1 mm) [33], [34], [35], [36]. The damage of coatings on the surface can significantly affect the antimicrobial properties of SS, resulting in a limited service duration. Therefore, low-cost SS with long-term antimicrobial properties is required for replacing conventional SS products used in public areas [37].

It has been reported that SS containing Cu contents of 1 ∼ 5 wt% (weight percent) possess an antibacterial rate of higher than 99% because intensive Cu-rich precipitates are permanently present in the SS matrix [38], [39]. Comparing to Cu, Ag has an even stronger antibacterial ability. Only 0.3 wt% addition of Ag in the SS matrix can produce a strong antibacterial capability [40]. However, these studies have only focused on the antibacterial properties. The antiviral properties of SS containing Cu or Ag remain poorly investigated. It is still not known whether SS containing Ag or Cu can display good antiviral properties. To investigate if traditional SS can be modified to inactivate pathogen microbes, especially the SARS-CoV-2, powder metallurgy (PM) technology has been introduced. Because of the extremely low solid solubility of Ag inside the SS matrix and the well-known problem of “copper brittleness” to fabricate SS with high Cu content by traditional steel casting [40], [41], PM methods were applied for the preparation of various SS in this research. Then, systematic experiments were carried out to study the stability of SARS-CoV-2, H1N1, and Escherichia coli (E.coli) on the surface of these metals.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and sample preparation

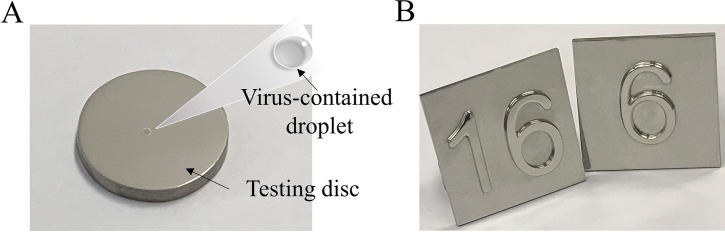

The stabilities of SARS-CoV-2, H1N1, and E.coli on the surface of the as-prepared discs (Fig. 1 A) were evaluated. Among them, conventional 316L SS, pure Ag (purity: >99.5 wt%), and pure Cu (purity: >99.5 wt%) were used as the reference materials. SS containing 0.3 wt% Ag (SS-0.3Ag), 0.6 wt% Ag (SS-0.6Ag) and SS containing 1 wt% Cu (SS-1Cu), 5 wt% Cu (SS-5Cu), 10 wt% Cu (SS-10Cu), 20 wt% Cu (SS-20Cu) were prepared by the PM technology, with the sample codes summarized in Table 1 . The details are described below.

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematics of the surface test simulating virus droplet at ambient conditions; (B) Lift buttons made from the SS-20Cu by PM technology.

Table 1.

Summaries of the sample matrix.

| Sample | Material description | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 316L | Typical 316L stainless steel | Reference material |

| Ag | Pure Ag (purity: >99.5 wt%) | Reference material |

| Cu | Pure Cu (purity: >99.5 wt%) | Reference material |

| SS-0.3Ag | 316L SS powder mixed withnano Ag2O (0.3 wt% Ag) | Ag-contained SS |

| SS-0.6Ag | 316L SS powder mixed withnano Ag2O (0.6 wt% Ag) | Ag-contained SS |

| SS-1Cu | 316L SS powder mixed withCu powder (1 wt% Cu) | Cu-contained SS |

| SS-5Cu | 316L SS powder mixed withCu powder (5 wt% Cu) | Cu-contained SS |

| SS-10Cu | 316L SS powder mixed withCu powder (10 wt% Cu) | Cu-contained SS |

| SS-20Cu | 316L SS powder mixed withCu powder (20 wt% Cu) | Cu-contained SS |

Fine 316L SS powders (D50 = 2.5 μm, D90 = 5 μm) and nano Ag2O powder (D50 = 35 nm, D90 = 80 nm, purity: 99.5 wt%) were used as the raw materials to produce SS-0.3Ag and SS-0.6Ag samples. Firstly, the nano Ag2O powder was added into a beaker filled with ethanol, then stirred and dispersed under an ultrasonic vibrator before adding the 316L SS powder. Then, the ethanol was evaporated in a vacuum drying oven to obtain the composite powder of the 316L SS and Ag2O. Finally, the composite powder was packed into a graphite die with an inner diameter of 15 mm and sintered under a pressure of 50 MPa at 900 °C for 10 min by spark plasma sintering (SPS, SPS-211Lx, Fujieda Kogyo Co. Ltd. Japan). The fabrications of SS-1Cu, SS-5Cu, SS-10Cu, and SS-20Cu samples were carried out by mixing commercial 316L SS powder (Sandvik, D50 = 14 μm, D90 = 26 μm) with 1 wt%, 5 wt%, 10 wt%, and 20 wt% Cu powder (D50 = 5.8 μm, D90 = 12 μm), respectively via a 3D mixer (WAB, Turbula T2F) for 2 h. Then, the mixed powder was cold compacted into a mold with an inner diameter of 15 mm under 600 Mpa. After that, the compacted discs were sintered in a tube furnace. Then, all these Cu-contained SS samples were solution heat-treated at 1300 °C for 120 min followed by water quench. Finally, an aging treatment was applied at 700 °C for 8 h for all these Cu-contained SS samples. All metals are mechanically polished to discs with a diameter of about 14.7 mm and polished with 1 μm polishing liquid for further experiments. Besides, lift buttons (Fig. 1B) made from the SS-20Cu via PM technology were prepared to present possible applications in public areas.

2.2. Virus and cells

SARS-CoV-2 (BetaCoV/Hong Kong/VM20001061/2020) and H1N1 virus (A/Puberto Rico/8/1934, a laboratory strain) were prepared and titrated with Vero E6 and Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells, respectively. The cells were purchased from ATCC. Vero E6 and cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 U·mL−1 penicillin/streptomycin, while MDCK cells were maintained in Minimum Essential Media (MEM) with 10% FBS and 100 U·mL−1 penicillin/streptomycin. Experimental works with SARS-CoV-2 and H1N1 influenza A virus were performed in the BSL-3 and BSL-2 laboratories, respectively.

E.coli (ATCC 8739) was used as the experimental bacteria in this study. One loop of the monoclonal bacterial strain was cultivated in the nutrition broth (NB) medium on the shaking table at 37 °C, 200 rpm for 24 h. Then, the inoculum was diluted with NB solution to a concentration of about 2 × 106 colony forming unit (CFU)·mL−1 for further experiment.

2.3. Virus inactivation kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 on various metal surfaces

Metal discs of different materials were ground with wet SiC paper up to 2000 grit and polished by 1 μm polishing liquid for further experiments. All discs are sterilized by autoclave before the test. A 5 μL droplet of SARS-CoV-2 (6.2 × 107 TCID50·mL−1) was applied on each metal surface. The virus was allowed to dry and incubate for different time durations at the ambient condition (at 22 ∼ 23 °C, 60 ∼ 70% relative humidity). After incubation, the metal discs were immersed in a 300 μL viral transport medium (VTM, containing 0.5 w/v% bovine serum albumin and 0.1 w/v% glucose in Earles’s balanced salt solution, pH 7 – 7.5) for 30 min at the ambient temperature to elute the virus. The eluted virus was titrated with Vero E6 cells by TCID50 assay as described [32]. Three independent tests were performed for each incubation time of each material and virus. The time duration was measured immediately after the virus-contained droplet was applied to the surface. The zero-hour incubation indicates an immediate virus elution after applying the virus droplet to each surface.

2.4. Anti-pathogen property against H1N1 and E.coli

The performance of antiviral properties for various materials was further examined using H1N1. The H1N1 virus was prepared at an initial concentration of 1.4 × 108 plaque forming unit (PFU)·mL−1. Each metal disc was applied with a virus-contained droplet of 5 μL on the surface. After that, the virus was allowed to dry and incubated at the ambient temperature and humidity (at 22 ∼ 23 °C, 60 ∼ 70% relative humidity) for different durations. Finally, the residual H1N1 virus at each time point was collected by immersing the metal discs in 300 μL VTM (containing 0.5 w/v% bovine serum albumin and 0.1 w/v% glucose in Earles’s balanced salt solution, pH 7–7.5) for 30 min at the ambient temperature for virus elution. The eluted virus was titrated with MDCK cells by the TCID50 assay. Three independent experiments were performed for each material at each time point. The measurement was started immediately after the virus-contained droplet was applied. The zero-hour incubation indicates an immediate virus elution after applying the virus droplet to each surface.

In addition, metals with noticeable antiviral properties compared with 316L SS within 24 h were further employed for the antibacterial test (plate counting method, JIS Z2801-2000) to assess the antibacterial properties. A 6 µL droplet of the as-prepared fresh E.coli (ATCC 8739) bacteria suspension (2 × 106 CFU·mL−1) was dripped on the surface of the selected metals. Then, the samples were covered with coverslips to ensure that the bacteria suspension was in close contact with the sample surface. After the co-culture of the bacterial suspension and samples at 37 °C for 24 h under a humidity of 90%, the remaining bacterial strain on the sample surface was harvested by 100 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution by repeating washing. Next, the harvest solution was spread on the NB plate and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under a humidity of 90%. Finally, the bacterial colonies were counted to assess the number of active bacteria on the sample surface. Convention 316L SS was used as the control group without antibacterial properties, while the selected materials were used as the experiment group. Fewer bacterial colonies can be observed on the NB plate if materials have exhibited antibacterial properties compared with 316L. The antibacterial rate was calculated by:

Where R stands for the antibacterial rate, N control is the value of bacterial colonies that remained on the 316L SS, N sample accounts for bacterial colonies for the experiment group samples. Each test was repeated three times for calculating the antibacterial rate.

2.5. Microstructures characterization and the Ag/Cu ion release behavior

Microstructure observation was conducted for the developed anti-pathogen SS. Specimens were ground by abrasive papers up to 2000 grits and polished by 1 μm polishing liquid. The ZEISS Sigma 300 scanning electronic microscope (SEM) equipped with a backscattering electron (BSE) detector and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was used. Focus ion beam (FIB, FEI Helios 600i) was used to prepare transmission electron microscope (TEM) samples. Talos TEM equipped with a high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) detector and high-resolution EDX was used to identify the nano-sized precipitates.

The ISO standard 10993–12:2002 was used as the reference for the Ag/Cu ion release test. All testing samples were ground up to 2000 grit with an exposed surface area of about 1.96 cm2 and placed in a 24-well culture plate. Then, 1.5 mL of the as-prepared DMEM solution, which was used to prepare the SARS-CoV-2 virus-contained droplet, was dropped into each well containing samples. After that, the plate was also incubated at ambient conditions (at 22 ∼ 23 °C, 60 ∼ 70% relative humidity) for different time intervals. Finally, the released Cu and Ag ion concentration was measured by an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, iCAP RQ Quadrupole, ThermoFisher, USA). Three duplicate experiments were conducted for each material at the same time intervals.

2.6. Electrochemical corrosion test

Potentiodynamic polarization tests were conducted to evaluate the corrosion resistance of the anti-pathogen SS using the 3000A-DX PARSTAT electrochemical workstation. The heat-treated samples were cut into corrosion specimens of 10 mm × 10 mm × 1 mm. All specimens were polished by SiC papers to 1200 grits. A typical three-electrode cell setup containing 0.9 wt% NaCl solution was adopted. Platinum (Pt) and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) were used as the counter electrode and reference electrode. Before the test, an open circuit potential (OCP) process for 3600 s was conducted to form a fresh surface. Next, a potential scan rate of 1 mV·s−1 was used to measure the potentiodynamic polarization curve of each specimen. Pitting potential (Ep) was defined as the potential at which current density exceeded 10−5 A·cm−2 . Three independent tests were conducted for each material.

2.7. Mechanical properties

Mechanical properties of the developed anti-pathogen SS were investigated using uniaxial tensile tests. Tensile samples (with a cross section of 3.25 mm × 2.5 mm and a gauge length of 18 mm) were prepared and sintered following the disc samples. All samples were heat treated and mechanical polished before tests. Room temperature tensile tests were conducted using a MTS 810 machine at a strain rate of 1 × 10-4 s−1. An extensometer with a 10 mm gauge length was used for strain measurement. The yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS), and elongation to failure (EL) were determined from the engineering stress–strain curves.

2.8. Data analysis

The kinetics of virus inactivation was measured by the percentage of measured remaining viable viruses at different periods versus the measured viable virus at zero hour. The mean value and standard deviation (SD) of the aforementioned percentage at each time point were then calculated. A faster decrease of the mean value over time indicates a higher inactivation efficiency. In other words, a smaller mean value at a specific time point indicates a better antiviral ability. The 0% of the remaining viable virus implies that the remaining viable virus has been reduced to the detecting limit of the TCID50 assay.

3. Results

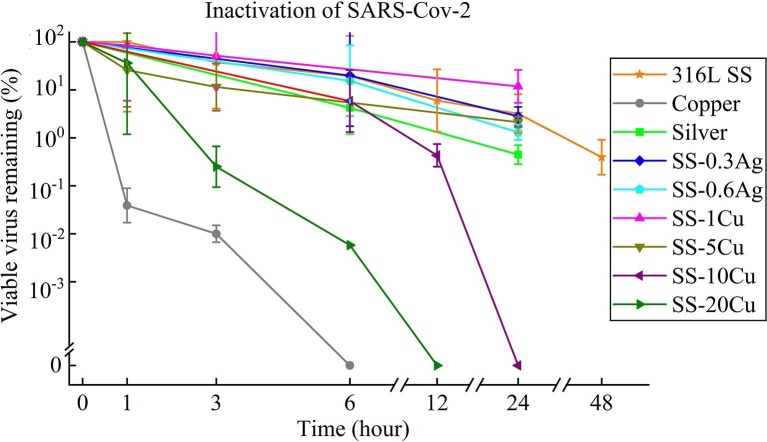

3.1. Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 on Ag and Ag-contained SS with incubation time

As shown in Fig. 2 , the viability of SARS-CoV-2 has exhibited an exponential decrease on the surface of all metals. Nevertheless, a sufficient amount of infectious viruses were detected on the surface of conventional 316L SS even after 48 h, which is consistent with the literature result that infectious SARS-CoV-2 can be detected on the surface of conventional SS for up to three days [15], [18]. Unexpectedly, the inactivation curves of the SARS-CoV-2 on pure silver, SS-0.3Ag, and SS-0.6Ag are similar to conventional 316L SS. In other words, no antiviral property is observed for pure silver, SS-0.3Ag, and SS-0.6Ag.

Fig. 2.

Viability of the SARS-Cov-2 on the surfaces of various metals (each point is the average value of three measurements).

3.2. Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 on Cu and Cu-contained SS with incubation time

As exhibited by Fig. 2, similar to the literature result [15], pure Cu exhibits a strong inhibitory effect against SARS-CoV-2, with 99.99% virus inactivated after only 3 h and no viable virus can be detected after 6 h. Nevertheless, it is interesting to compare the inactivation curves of two Cu-contained SS (SS-1Cu and SS-5Cu) with 316L SS. Though they are similar to the previously developed Cu-contained SS with excellent antibacterial properties [39], the SS-1Cu and SS-5Cu do not display antiviral properties against SARS-CoV-2 even after 24 h. On the contrary, noticeable differences in the inactivation curves between the Cu-contained SS of high Cu content and 316L SS were observed after 24 h. No viable SARS-CoV-2 can be detected on the surface of SS-10Cu after 24 h. Significantly, the SS-20Cu can reduce 99.75% and 99.99% of viable SARS-CoV-2 on its surface within 3 and 6 h, respectively. Furthermore, in order to demonstrate their potential applications in public areas, press buttons of lifts were fabricated using SS-20Cu (Fig. 1B). As exhibited, since no hot forging or rolling process is required for PM technology, such anti-pathogen SS products of high Cu content are suitable for mass production.

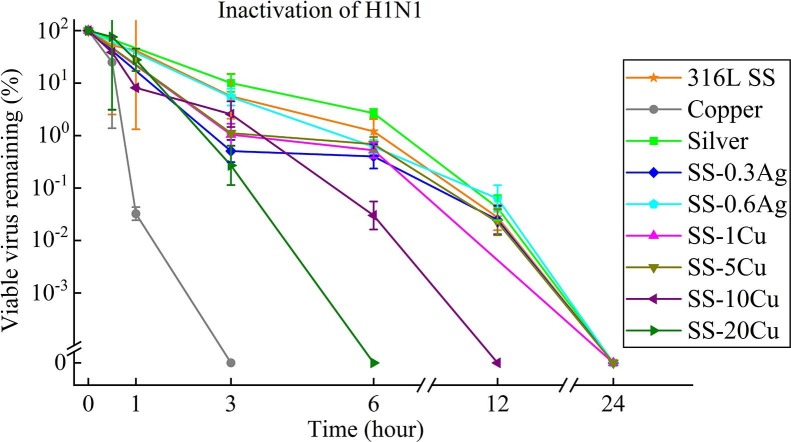

3.3. Anti-pathogen property against H1N1 and E.coli

Fig. 3 shows the inactivation curves of various metal surfaces against H1N1. As can be seen, pure Cu exhibits the best inhibitory effect on H1N1 with no viable virus detected only after 3 h. Yet, similar to the testing result of SARS-CoV-2, no obvious difference can be found for the inactivation curves of H1N1 among conventional 316L SS, pure Ag, SS-0.3Ag, SS-0.6Ag, SS-1Cu, and SS-5Cu, indicating that these metals do not have antiviral properties against H1N1. On the contrary, an apparent antiviral property towards H1N1was also observed for the SS-10Cu and SS-20Cu. In particular, no infectious H1N1 virus is detected only after 6 h for the SS-20Cu.

Fig. 3.

Viability of H1N1 on the surfaces of various metals (each point is the average value of three measurements).

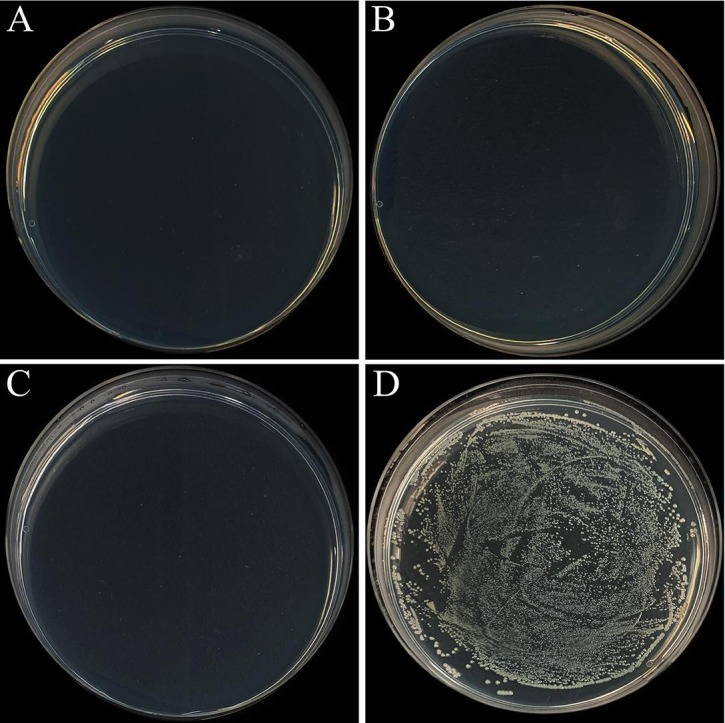

Fig. 4 displays the typical bacterial colonies for SS-10 Cu, SS-20Cu, pure Cu, and conventional 316L SS. As exhibited, a large number of bacterial colonies were observed on the NB plate for 316L SS, consistent with the literature result that conventional SS does not have antibacterial properties [13], [14]. By contrast, few bacterial colonies can be found on the NB plate for the SS-10Cu, SS-20Cu, and pure Cu, indicating an antibacterial rate of above 99.99%.

Fig. 4.

Photos of typical bacterial colonies for the testing metals. A) SS-10Cu, B) SS-20Cu, C) pure Cu, D) 316L.

3.4. Microstructure observation and the Ag/Cu ion release behavior

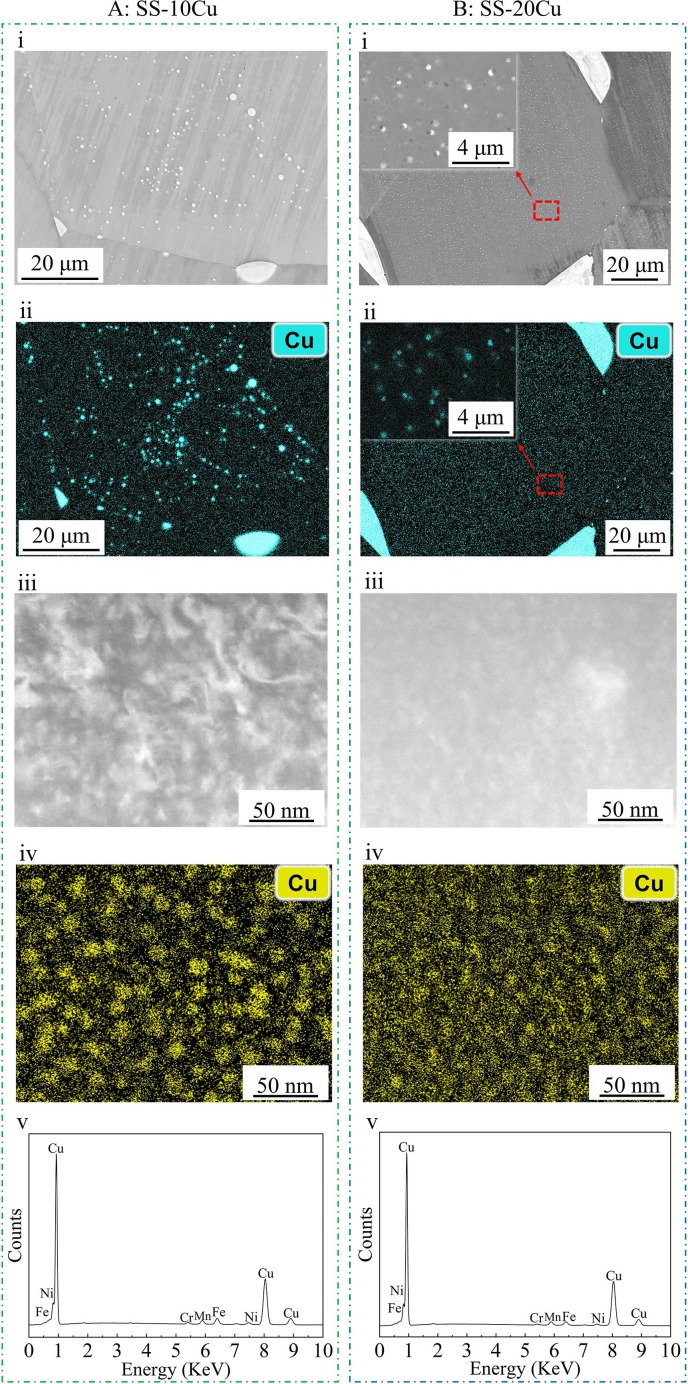

As shown in the SEM BSE images of Fig. 5 A(i) and B(i) and the corresponding EDX mapping results in Fig. 5A (ii) and B (ii), massive Cu-rich precipitates with sizes ranging from sub-micron to tens of microns are present in the matrix. In addition, HAADF images (Fig. 5A (iii) and B (iii)) and the corresponding EDX images (Fig. 5, A(iv) and B(iv)) show that intensive nano-sized Cu-rich precipitates are also present in the matrix of both SS-10Cu and SS-20Cu. The EDX spectrums of the precipitates in the SS-10Cu and SS-20Cu (Fig. 5A (v) and B (v)) also indicate that these precipitates are rich in Cu. In addition, the TEM-EDX results indicate that solid solution Cu atoms could also be present in the matrix.

Fig. 5.

Microstructures of SS-10Cu and SS-20Cu. (A) SS-10Cu and (B) SS-20Cu. (i) BSE image for Cu-rich precipitates of micron and submicron sizes within the SS matrix; (ii) the corresponding EDX mapping of Cu element in (i); (iii) TEM HAADF images of nano-sized Cu-rich precipitates within the SS matrix; (iv) the corresponding EDX mapping of Cu element in (iii); (v) the EDX spectrum for the Cu-rich phase.

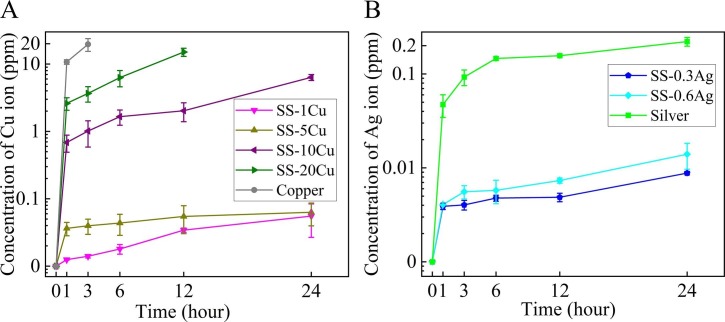

Fig. 6A shows the released Cu ion concentration (both Cu+ and Cu2+) for pure Cu and various Cu-contained SS in the DMEM solution. Interestingly, a low concentration of Cu ion (<0.1 ppm) released from the SS-1Cu and SS-5Cu was detected. However, there is a significant increase of the released Cu ion concentration (>1 ppm) after 24 h when the Cu content increases to 10 wt%. Also, an even higher released Cu ion concentration was detected for the SS-20Cu and pure Cu, respectively. Fig. 6B indicates the released Ag ion concentration for pure Ag and the Ag-contained SS in the DMEM solution. As can be seen, a low Ag ion concentration released from the two Ag-contained SS (about 0.01 ppm) was detected even after 24 h. Though there is a significant increase of Ag ion concentration released from pure Ag after 24 h, the concentration is still very low (about 0.2 ppm). Overall, the Ag ion concentration released from Ag and Ag-contained SS is much lower than the Cu ion concentration released from Cu, SS-10Cu, and SS-20Cu.

Fig. 6.

(A) Cu ion concentration released from pure Cu and the Cu-contained SS in the DMEM solution; (B) Ag ion concentrations released from pure Ag and the Ag-contained SS in the DMEM solution.

3.5. Corrosion behaviors and mechanical properties

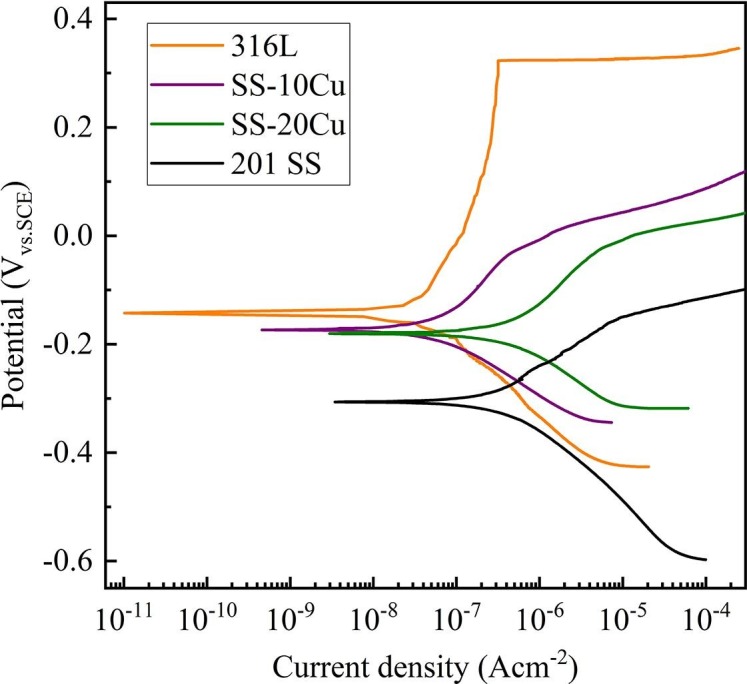

Fig. 7 shows the corrosion performance of the SS-10Cu, SS-20Cu, and the commonly used 316L SS and 201 SS in this study. There is an apparent reduction of Ep for SS-10Cu (Ep: 0.043 V) and SS-20Cu (Ep: −0.076 V), compared with 316L SS (Ep: 0.335 V). This is consistent with the literature result that the presence of Cu-rich precipitates within the SS matrix can reduce the resistance against pitting corrosion in chloride environments [42]. Nevertheless, the SS-10Cu and SS-20Cu still have a higher Ep than the 201 SS (Ep: −0.147 V). 316L is widely used in the food and medical industries due to its superior mechanical properties and corrosion resistance [43], [44], [45], [46]. Admittedly, the 201 SS is not a food-grade class. However, as another frequently used SS, the 201 SS has a broad application in common healthcare settings, such as railings, handrails, and lift buttons in public areas. Overall, the corrosion resistance of the SS-10Cu, SS-20Cu has significantly decreased compared with 316L. They still have a better corrosion resistance than 201 SS.

Fig. 7.

Electrochemical polarization curves of the experimental stainless steels soaked in 0.9 wt% NaCl solution.

The strength and ductility of the SS are also the concerning property for applications. Table 2 shows the mechanical properties of the 316L SS fabricated by PM technologies from literature and the anti-pathogen Cu-contained SS (SS-10Cu and SS-20Cu) in this study [47]. As can be seen, the developed anti-pathogen SS still possess reasonably good mechanical properties.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of the experimental stainless steels and typical PM 316L in literature.

4. Discussion

Humans can produce respiratory droplets ranging from 0.1 to 1000 μm during breathing, speaking, coughing, and sneezing [7]. The travel routes of these virus-laden droplets exhaled from infected individuals are determined by droplet size, inertia, gravity, and evaporation. The larger respiratory droplets tend to undergo gravitational settling faster than evaporation, contaminating contact surfaces and leading to contact transmission [7], [48]. As shown in Fig. 2, infectious SARS-CoV-2 can still be detected on the surface of conventional 316L SS even after two days. It indicates that respiratory droplets containing SARS-CoV-2 on conventional SS products used in public areas will pose a high risk of virus transmission via surface touching. Indeed, researchers have found that infectious pathogen virus or bacteria on the surface of SS can still be detected after typical cleaning procedures (e.g., wiping with water, liquid soap) [17]. Therefore, it is vital to develop low-cost SS that can inactivate SARS-CoV-2 and reduce the risk of virus transmission as possible. Then, they can be used to replace the conventional SS products used in public areas, combating the current COVID-19 and future pandemic, which is the primary motivation of the present study.

Studies have demonstrated that Ag nanoparticles can inactivate H1N1 and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) [49], [50]. Furthermore, some Ag-contained composite materials have also been reported to have antiviral properties [51], [52]. Therefore, the stability of SARS-CoV-2 on the surfaces of pure silver and Ag-contained SS was tested firstly in this research (Fig. 2). However, the remaining viable SARS-CoV-2 on pure Ag and Ag-contained SS is similar to that of the 316L SS even after 24 h. Furthermore, as shown by Fig. 3, the experimental results for H1N1 also verify that pure Ag and Ag-contained SS do not display antiviral properties compared with the 316L SS. This is in stark contrast to the excellent antibacterial property of pure silver, SS-0.3Ag and SS-0.6Ag [28], [53], [54], [55]. Even though the exact mechanism is still under debate, it is believed that multiple factors have contributed to the antibacterial effect of Ag, like the inhibition of respiratory enzymes by released Ag ions and electron transfer interaction from microbial membrane to Ag [56], [57]. However, researchers have found that factors affecting the killing efficiency of viruses and bacteria might be different [58], [59], [60], [61]. Most of the reported antiviral properties of Ag are related to Ag nanoparticles (Ag NPs), where the antiviral mechanism of Ag NPs is likely the physical inhibition of binding between the virus and host cell [58], [61]. Furthermore, the detected concentration of released Ag ion from the bulk Ag surface is<1 ppm (Fig. 6B) even after 24 h. The low Ag ion concentration might also account for the poor antiviral properties, which still need further study. Collectively, it might be possible that Ag is probably not a suitable alloying element to develop anti-pathogen SS.

Interestingly, for pure Cu, SS-20Cu, and SS-10Cu, no viable SARS-CoV-2 can be detected after 6, 12, 24 h (Fig. 2), and no viable H1N1 can be detected after 3, 6, 12 h (Fig. 3), respectively. This agrees with the previous findings that SARS-CoV-2 is more stable than influenza in different environmental conditions [62]. In addition, Fig. 2 also illustrates that the inactivation efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 increases with Cu content in SS. Though the inactivation curves of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2) for SS-1Cu, SS-5Cu, and 316LSS are similar, no viable SARS-CoV-2 can be detected on the surface of SS-10Cu after 24 h. In particular, SS-20Cu can inactivate 99.75% and 99.99% of viable SARS-CoV-2 after 3 and 6 h, respectively. However, pure Cu exhibits an even better antiviral property, inactivating 99.99% of viable SARS-CoV-2 after 3 h. A similar trend is also observed for H1N1, i.e., the anti-H1N1 capability of SS increases with Cu content, as shown in Fig. 3. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 4, few bacterial colonies can be observed for the SS-10Cu and SS-20Cu, indicating excellent antibacterial properties against E.coli. To summarize, it is interesting to note that metals (e.g., pure Cu, SS-20Cu, SS-10Cu) with antiviral properties show simultaneously antibacterial properties. Nevertheless, metals (e.g., pure Ag, SS-0.3Ag, SS-0.6Ag, SS-1Cu, SS-5Cu) with antibacterial properties do not necessarily possess antiviral properties.

Even though the exact virus inactivation mechanism of Cu is still under debate in the literature, researchers have indicated that a high concentration of Cu ions would help sterilize both viruses and bacteria [63]. It is reported that the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by free Cu ions (Cu+ and Cu2+) can participate in redox reactions. These ROS, Cu ion, and H2O2 in the reactions play an essential role in viral inactivation [64]. Besides, some studies have exhibited that Cu ion may also disturb the genetic replication process of viruses [64], [65]. These mechanisms may contribute to the antiviral properties of the present anti-pathogen SS. Interestingly, a correlation between the inactivation efficiency and the concentration of Cu ions was also found in this research. For instance, the released Cu ion concentration from the SS-1Cu and SS-5Cu is smaller than 0.1 ppm after 24 h. However, the released Cu ion concentration from the SS-20Cu reaches about 4 ppm after 3 h, while it approaches about 10 ppm after 1 h for pure Cu.

Though pure Cu exhibits an excellent antiviral efficiency towards SARS-CoV-2[15], [32], pure Cu is not suitable for massive engineering applications in public areas due to its high cost, low strength, and less corrosion resistance. Moreover, some studies tried to introduce antimicrobial properties into conventional SS by surface coating or ion implantation[28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]. However, it is necessary to note that Cu coating is soft, and the thickness of coatings is limited [33], [34], [35], [36]. The depletion of coatings on the SS surface can lead to the loss of anti-pathogen properties. On the contrary, it is worth noting that Cu-rich precipitates are homogeneously distributed in the entire bulk sample for the anti-pathogen SS (SS-10Cu and SS-20Cu), not only on their surfaces. There will always be Cu-rich precipitates exposed on the surfaces of the anti-pathogen SS, even if the samples are continuously damaged during service, leading to a long-term antimicrobial property. In addition, the present anti-pathogen SS can be directly employed for industrial production by the current PM technology to replace part of the conventional stainless steel products in public areas. As the first trial production, SS-20Cu lift buttons have been successfully produced for demonstration (Fig. 1B). Besides, it is reasonable to assume that present anti-pathogen SS will not have significant harmful effects on users in the public areas as the duration of surface touching is very short, which still needs further study.

It is widely accepted that Cu has a broad-spectrum antibacterial property, which can inactivate broad kinds of bacteria on its surface [19], [38], [66]. Also, researchers have revealed that Cu has exhibited noticeable antiviral properties towards many species of viruses [18], [20], [51], [67]. Since massive Cu-rich precipitates are present in the whole SS matrix, it might be reasonable to assume that the developed anti-pathogen SS can also inactivate other pathogen microbes in addition to SARS-CoV-2, H1N1, and E.coli. Nevertheless, the antimicrobial tests of other viruses and bacteria still need further studies. Additionally, as shown by Fig. 7 and Table 2, the developed anti-pathogen SS also possess reasonable corrosion resistance and mechanical properties for application purposes. In conclusion, it is the first anti-pathogen SS inactivating SARS-CoV-2. This anti-pathogen SS has a great potential to replace some SS products used in public areas, which can provide meaningful efforts to combat the current COVID-19 or future pandemic.

5. Conclusion

In summary, a low-cost, anti-pathogen Cu-contained stainless steel with long-term anti-SARS-COV-2 properties has been developed successfully. The following main conclusions can be drawn.

-

1.

Pure silver and Ag-contained SS do not display effective inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 and H1N1.

-

2.

Infectious SARS-CoV-2 can be detected on the surface of conventional SS even after 48 h.

-

3.

SS with 20 wt% Cu can reduce 99.75% and 99.99% of viable SARS-CoV-2 on its surface within 3 and 6 h, respectively.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

M.X. Huang acknowledges the financial support from Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (No. C7025-16G). L.L.M Poon acknowledges financial support from the Health and Medical Research Fund (COVID190116), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (contract HHSN272201400006C). P. Yu acknowledges the financial support from Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee (grant number KQJSCX20180322152424539).

References

- 1.Lu R.J., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P.H., Yang B., Wu H.L., Wang W.L., Song H., Huang B.Y., Zhu N., Bi Y.H., Ma X.J., Zhan F.X., Wang L., Hu T., Zhou H., Hu Z.H., Zhou W.M., Zhao L., Chen J., Meng Y., Wang J., Lin Y., Yuan J.Y., Xie Z.H., Ma J.M., Liu W.J., Wang D.Y., Xu W.B., Holmes E.C., Gao G.F., Wu G.Z., Chen W.J., Shi W.F., Tan W.J. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taubenberger J.K., Morens D.M. 1918 influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12(1):15–22. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.050979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Springston J.P., Yocavitch L. Existence and control of Legionella bacteria in building water systems: A review. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 2017;14(2):124–134. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2016.1229481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu D.K.W., Pan Y., Cheng S.M.S., Hui K.P.Y., Krishnan P., Liu Y.Z., Ng D.Y.M., Wan C.K.C., Yang P., Wang Q.Y., Peiris M., Poon L.L.M. Molecular Diagnosis of a Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Causing an Outbreak of Pneumonia. Clinical Chemistry. 2020;66(4):549–555. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prather K.A., Wang C.C., Schooley R.T. Reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;368(6498):1422–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michie S., West R., Rogers M.B., Bonell C., Rubin G.J., Amlôt R. Reducing SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the UK: A behavioural science approach to identifying options for increasing adherence to social distancing and shielding vulnerable people. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25(4):945–956. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittal R., Ni R., Seo J.H. The flow physics of COVID-19. Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 2020;894 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L., Ding Q., Zhong Y., Zou J.i., Wu J., Chiu Y.-L., Li J., Zhang Z.e., Yu Q., Shen Z. Dislocation network in additive manufactured steel breaks strength-ductility trade-off. Materials Today. 2018;21(4):354–361. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang H.W., Wang Z.B., Lu J., Lu K. Fatigue behaviors of AISI 316L stainless steel with a gradient nanostructured surface layer. Acta Materialia. 2015;87:150–160. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrera C., Ponge D., Raabe D. Design of a novel Mn-based 1 GPa duplex stainless TRIP steel with 60% ductility by a reduction of austenite stability. Acta Materialia. 2011;59(11):4653–4664. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan F.K., Liu G.Z., Tao N.R., Lu K. Strength and ductility of 316L austenitic stainless steel strengthened by nano-scale twin bundles. Acta Materialia. 2012;60(3):1059–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez N., Cid M., Puiggali M. Influence of sigma-phase on mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steels. Corros Sci. 1999;41(8):1615–1631. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilks S.A., Michels H., Keevil C.W. The survival of Escherichia coli O157 on a range of metal surfaces. Int J Food Microbiol. 2005;105(3):445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kusumaningrum H.D., Riboldi G., Hazeleger W.C., Beumer R.R. Survival of foodborne pathogens on stainless steel surfaces and cross-contamination to foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003;85(3):227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(02)00540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt J.L., Thornburg N.J., Gerber S.I., Lloyd-Smith J.O., de Wit E., Munster V.J. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. New Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharps C.P., Kotwal G., Cannon J.L. Human Norovirus Transfer to Stainless Steel and Small Fruits during Handling. Journal of Food Protection. 2012;75(8):1437–1446. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuladhar E., Hazeleger W.C., Koopmans M., Zwietering M.H., Beumer R.R., Duizer E. Residual Viral and Bacterial Contamination of Surfaces after Cleaning and Disinfection. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78(21):7769–7775. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02144-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chin A.W.H., Chu J.T.S., Perera M.R.A., Hui K.P.Y., Yen H.L., Chan M.C.W., Peiris M., Poon L.L.M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1(1):E10. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian W.-X., Yu S., Ibrahim M., Almonaofy A.W., He L., Hui Q., Bo Z., Li B., Xie G.-L. Copper as an antimicrobial agent against opportunistic pathogenic and multidrug resistant Enterobacter bacteria. J Microbiol. 2012;50(4):586–593. doi: 10.1007/s12275-012-2067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noyce J.O., Michels H., Keevil C.W. Inactivation of influenza A virus on copper versus stainless steel surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(8):2748–2750. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01139-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panáček A., Kolář M., Večeřová R., Prucek R., Soukupová J., Kryštof V., Hamal P., Zbořil R., Kvítek L. Antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles against Candida spp. Biomaterials. 2009;30(31):6333–6340. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klasen H.J. Historical review of the use of silver in the treatment of burns. I. Early uses. Burns. 2000;26(2):117–130. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rai M., Yadav A., Gade A. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27(1):76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warnes S.L., Little Z.R., Keevil C.W., Colwell R. Human Coronavirus 229E Remains Infectious on Common Touch Surface Materials. Mbio. 2015;6(6) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01697-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lara H.H., Garza-Treviño E.N., Ixtepan-Turrent L., Singh D.K. Silver nanoparticles are broad-spectrum bactericidal and virucidal compounds. Journal of Nanobiotechnology. 2011;9(1) doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-9-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z., Qiao D., Xu Y., Zhou E., Yang C., Yuan X., Lu Y., Gu J.-D., Wolfgang S., Xu D., Wang F. Cu-bearing high-entropy alloys with excellent antiviral properties. Journal of Materials Science & Technology. 2021;84:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jmst.2020.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirose R., Ikegaya H., Naito Y., Watanabe N., Yoshida T., Bandou R., Daidoji T., Itoh Y., Nakaya T. Survival of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and Influenza Virus on Human Skin: Importance of Hand Hygiene in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong Y., Li X., Tian L., Bell T., Sammons R.L., Dong H. Towards long-lasting antibacterial stainless steel surfaces by combining double glow plasma silvering with active screen plasma nitriding. Acta Biomater. 2011;7(1):447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosetti M., Masse A., Tobin E., Cannas M. Silver coated materials for external fixation devices: in vitro biocompatibility and genotoxicity. Biomaterials. 2002;23(3):887–892. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dan Z.G., Ni H.W., Xu B.F., Xiong J., Xiong P.Y. Microstructure and antibacterial properties of AISI 420 stainless steel implanted by copper ions. Thin Solid Films. 2005;492(1-2):93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowan M.M., Abshire K.Z., Houk S.L., Evans S.M. Antimicrobial efficacy of a silver-zeolite matrix coating on stainless steel. J Ind Microbiol Biot. 2003;30(2):102–106. doi: 10.1007/s10295-002-0022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Behzadinasab S., Chin A., Hosseini M., Poon L., Ducker W.A. A Surface Coating that Rapidly Inactivates SARS-CoV-2. Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2020;12(31):34723–34727. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c11425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hutasoit N., Kennedy B., Hamilton S., Luttick A., Rahman Rashid R.A., Palanisamy S. Sars-CoV-2 (COVID-19) inactivation capability of copper-coated touch surface fabricated by cold-spray technology. Manufacturing Letters. 2020;25:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mfglet.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wan Y.Z., Raman S., He F., Huang Y. Surface modification of medical metals by ion implantation of silver and copper. Vacuum. 2007;81(9):1114–1118. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ni H.-W., Zhang H.-S., Chen R.-S., Zhan W.-T., Huo K.-f., Zuo Z.-y. Antibacterial properties and corrosion resistance of AISI 420 stainless steels implanted by silver and copper ions. International Journal of Minerals Metallurgy and Materials. 2012;19(4):322–327. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W., Zhang Y., Ji J., Yan Q., Huang A., Chu P.K. Antimicrobial polyethylene with controlled copper release, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for. Biomaterials. 2007;83(3):838–844. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.M. Huang, L. Liu, An antimicrobial stainless steel containing Cu and its fabricaiton method. Patent Application number: 202010730748.2 China 2020.

- 38.Hong I.T., Koo C.H. Antibacterial properties, corrosion resistance and mechanical properties of Cu-modified SUS 304 stainless steel. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing. 2005;393(1-2):213–222. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun D.a., Xu D., Yang C., Shahzad M.B., Sun Z., Xia J., Zhao J., Gu T., Yang K.e., Wang G. An investigation of the antibacterial ability and cytotoxicity of a novel cu-bearing 317L stainless steel. Sci Rep-Uk. 2016;6(1) doi: 10.1038/srep29244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu L.T., Li Y.Z., Yu K.P., Zhu M.Y., Jiang H., Yu P., Huang M.X. A novel stainless steel with intensive silver nanoparticles showing superior antibacterial property. Materials Research Letters. 2021;9(6):270–277. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeşiltepe S., Şeşen M.K. High-temperature oxidation kinetics of Cu bearing carbon steel. Sn Applied Sciences. 2020;2(4) doi: 10.1007/s42452-020-2473-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xi T., Shahzad M.B., Xu D.K., Sun Z.Q., Zhao J.L., Yang C.G., Qi M., Yang K. Effect of copper addition on mechanical properties, and antibacterial property of 316L stainless steel corrosion resistance. Materials Science & Engineering C-Materials for Biological Applications. 2017;71:1079–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurgan N., Sun Y., Cicek B., Ahlatci H. Production of 316L stainless steel implant materials by powder metallurgy and investigation of their wear properties. Chinese Science Bulletin. 2012;57(15):1873–1878. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beddoes J., Bucci K. The influence of surface condition on the localized corrosion of 316L stainless steel orthopaedic implants. Journal of materials science: Materials in medicine. 1999;10(7):389–394. doi: 10.1023/a:1008918929036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chew K.-K., Zein S.H.S., Ahmad A.L. The corrosion scenario in human body: Stainless steel 316L orthopaedic implants. NS. 2012;04(03):184–188. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walczak J., Shahgaldi F., Heatley F. In vivo corrosion of 316L stainless-steel hip implants: morphology and elemental compositions of corrosion products. Biomaterials. 1998;19(1–3):229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y., Feng E., Mo W., Lv Y., Ma R., Ye S., Wang X., Yu P. On the microstructures and fatigue behaviors of 316L stainless steel metal injection molded with gas-and water-atomized powders. Metals. 2018;8(11):893. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tellier R., Li Y., Cowling B.J., Tang J.W. Recognition of aerosol transmission of infectious agents: a commentary. Bmc Infectious Diseases. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3707-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu R.L., Li S.R., Kong F.J., Hou R.J., Guan X.L., Guo F. Inhibition effect of silver nanoparticles on herpes simplex virus 2. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2014;13(3):7022–7028. doi: 10.4238/2014.March.19.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang E., Liu C. A new antibacterial Co-Cr-Mo-Cu alloy: Preparation, biocorrosion, mechanical and antibacterial property. Materials Science & Engineering C-Materials for Biological Applications. 2016;69:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bright K.R., Sicairos-Ruelas E.E., Gundy P.M., Gerba C.P. Assessment of the Antiviral Properties of Zeolites Containing Metal Ions. Food and Environmental Virology. 2009;1(1):37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang L., Ning X., Xiao Q., Chen K., Zhou H. Development and characterization of porous silver-incorporated hydroxyapatite ceramic for separation and elimination of microorganisms. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B-Applied Biomaterials. 2007;81B(1):50–56. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schierholz J.M., Lucas L.J., Rump A., Pulverer G. Efficacy of silver-coated medical devices. J Hosp Infect. 1998;40(4):257–262. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90301-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Russell A.D., Hugo W.B. Antimicrobial activity and action of silver. Prog Med Chem. 1994;31:351–370. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6468(08)70024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mukha I.P., Eremenko A.M., Smirnova N.P., Mikhienkova A.I., Korchak G.I., Gorchev V.F., Chunikhin A.Y. Antimicrobial Activity of Stable Silver Nanoparticles of a Certain Size. Appl Biochem Micro+ 2013;49(2):199–206. doi: 10.7868/s0555109913020128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li J., Wang G., Zhu H., Zhang M., Zheng X., Di Z., Liu X., Wang X.i. Antibacterial activity of large-area monolayer graphene film manipulated by charge transfer. Sci Rep-Uk. 2015;4(1) doi: 10.1038/srep04359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liau S.Y., Read D.C., Pugh W.J., Furr J.R., Russell A.D. Interaction of silver nitrate with readily identifiable groups: relationship to the antibacterial action of silver ions. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1997;25(4):279–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mori Y., Ono T., Miyahira Y., Nguyen V.Q., Matsui T., Ishihara M. Antiviral activity of silver nanoparticle/chitosan composites against H1N1 influenza A virus. Nanoscale Research Letters. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-8-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pal S., Tak Y.K., Song J.M. Does the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles depend on the shape of the nanoparticle? A study of the gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli, Applied and environmental microbiology. 2007;73(6):1712–1720. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02218-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liau S., Read D., Pugh W., Furr J., Russell A. Interaction of silver nitrate with readily identifiable groups: relationship to the antibacterialaction of silver ions. Letters in applied microbiology. 1997;25(4):279–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Elechiguerra J.L., Burt J.L., Morones J.R., Camacho-Bragado A., Gao X., Lara H.H., Yacaman M.J. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with HIV-1. Journal of nanobiotechnology. 2005;3(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.I.H. Hirose R, Naito Y, Watanabe N, Yoshida T, Bandou R, Daidoji T, Itoh Y, Nakaya T., Survival of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus on the human skin: Importance of hand hygiene in COVID-19., Clin Infect Dis (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Horie M., Ogawa H., Yoshida Y., Yamada K., Hara A., Ozawa K., Matsuda S., Mizota C., Tani M., Yamamoto Y., Yamada M., Nakamura K., Imai K. Inactivation and morphological changes of avian influenza virus by copper ions. Archives of Virology. 2008;153(8):1467–1472. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ishida T. ROS-Mediated Virus; Copper Chelation: 2018. Antiviral Activities of Cu2+ Ions in Viral Prevention, Replication, RNA Degradation, and for Antiviral Efficacies of Lytic Virus. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Warnes S.L., Green S.M., Michels H.T., Keevil C.W. Biocidal Efficacy of Copper Alloys against Pathogenic Enterococci Involves Degradation of Genomic and Plasmid DNAs. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(16):5390–5401. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03050-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nan L.i., Ren G., Wang D., Yang K.e. Antibacterial Performance of Cu-Bearing Stainless Steel against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Whole Milk. Journal of Materials Science & Technology. 2016;32(5):445–451. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Warnes S.L., Keevil C.W., Samal S.K. Inactivation of Norovirus on Dry Copper Alloy Surfaces. Plos One. 2013;8(9):e75017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]