Abstract

The genus Abiotrophia represents a heterogeneous group of fastidious cocci that show a dependence on pyridoxal hydrochloride analogs for growth. The genetic heterogeneity in the genus Abiotrophia was examined by DNA-DNA hybridization, PCR assay of genomic DNA sequences, and restriction fragment length polymorphism and sequence homology analyses of the PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene. Nine type or reference strains of Abiotrophia defectiva, Abiotrophia adiacens, and Abiotrophia elegans and 36 oral Abiotrophia isolates including the ones presumptively identified as Gemella morbillorum by the rapid ID32 STREP system were divided into four groups: A. defectiva (genotype 1), A. adiacens (genotype 2), A. elegans (genotype 4), and a fourth species (genotype 3) which we propose be named Abiotrophia para-adiacens sp. nov. A PCR assay specific for detection and identification of the novel Abiotrophia species was developed. A. para-adiacens generally produced β-glucosidase but did not produce α- or β-galactosidase or arginine dihydrolase, did not ferment, trehalose, pullulan, or tagatose, and was serotype IV, V, or VI. Thus, it was distinguished phenotypically from A. adiacens, A. elegans, and A. defectiva as well as, apparently, from the recently described species Abiotrophia balaenopterae sp. nov., which produces arginine dihydrolase and which ferments pullulan but not sucrose (P. A. Lawson et al., Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:503–506, 1999). Strain ATCC 27527, currently listed as G. morbillorum, was a member of the species A. para-adiacens.

Streptococci that showed satellite growth around colonies of other microorganisms were first described by Frenkel and Hirsch in 1961 (6). They are the normal flora of the human mouth, pharynx, and intestinal and urogenital tracts and are often isolated from patients with so-called culture-negative bacterial endocardititis, bacteremia, and foci of various infectious diseases (2, 13, 16).

These organisms had formerly been known as nutritionally variant streptococci (NVS) and were supposed to be auxotrophic variants of viridans group streptococci (13). NVS require pyridoxal hydrochloride (vitamin B6) analogs for growth and produce chromophore, pyrrolidonyl arylamidase, and bacteriolytic enzyme in common with some viridans group streptococci (2, 4, 7, 12, 16). However, NVS show considerable variations in their glycosidase and peptidase production profiles (1, 7) and the electrophoresis patterns of their penicillin-binding proteins (4). The species of clinical NVS isolates are often indicated as Gemella morbillorum (Gemella-like NVS) by the rapid identification systems (5, 7, 21). Four broad biotypes have been demonstrated so far in this unique group of cocci (4, 7).

The earlier DNA-DNA hybridization study divided fastidious NVS into two species, Streptococcus defectivus and Streptococcus adjacens (2). They were then transferred to the species Abiotrophia defectiva and Abiotrophia adiacens, respectively, on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequence homology (8). A third, more fastidious species, Abiotrophia elegans, has recently been added to the genus Abiotrophia (14, 15). We have found that A. defectiva, A. adiacens, and A. elegans comprise 8, 84, and 8% of the NVS isolates from the human mouth, respectively (17). However, wider genetic heterogeneity among Abiotrophia spp. (18) and intraspecies variations in A. adiacens (3) have also been suggested.

The molecular genetic approaches such as restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes and PCR assay of genomic DNA sequences have become applied to the specific identification and differentiation of Abiotrophia spp. (3, 11, 15). In the present study, we examined the genetic variations among 45 Abiotrophia strains including the type strains of A. defectiva, A. adiacens, and A. elegans and the oral isolates in our laboratory (7) and propose the presence of a fourth Abiotrophia species, Abiotrophia para-adiacens sp. nov. During the preparation of this article, a novel species, Abiotrophia balaenopterae sp. nov., isolated from a minke whale has been described (10); however, A. balaenopterae sp. nov. appears to be distinct from A. para-adiacens sp. nov. on the basis of some phenotypic properties that have been reported.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Forty-five Abiotrophia strains were used (see Table 1). They included nine type or reference strains of A. defectiva (strains ATCC 49176T, PE7, and NVS-47), A. adiacens (strains ATCC 49175T, C50, L61, G40, and ATCC 27527), and A. elegans (strain DSM 11693T), with all except one known to be isolates from patients with endocarditis or bacteremia (2, 4, 14, 20). Strain ATCC 27527 is a sputum isolate and is listed as Gemella morbillorum in the current American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) catalog but was confirmed to be an A. adiacens strain by the Rapid ID32 STREP system (Bio Mérieux SA, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) and other bacteriological and biochemical tests described previously (7) (see Results). The other 36 strains were from our laboratory and were isolates from the human mouth (7). The species of most of these strains have been determined and their phenotypes have been characterized, and some were phenotypically characterized and their species were provisionally determined to be A. defectiva, A. adiacens, or G. morbillorum (Gemella-like NVS) with the rapid identification system as described previously (7). The strains were biotyped with the emended typing system (17) and were serotyped (K. Kitada, T. Kanamoto, Y. Okada, and M. Inoue, submitted for publication). Strains of the other six genera and 23 species listed in Table 3 were used for comparisons; of these six species of the genera Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Dolosigranurum, and Aerococcus were bacteriolytic and 17 species of the genera Gemella, Streptococcus, Aerococcus, and Staphylococcus were nonbacteriolytic. Their Micrococcus luteus cell lysis activities were examined as described previously (7).

TABLE 1.

DNA homologies of Abiotrophia strains

| Strain | Species determined by Rapid ID32 STREP systema | Emended NVS biotypeab | % Homology with the probe DNA from:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. defectiva ATCC 49176T | A. adiacens ATCC 49175T | A. adiacens TKT1 | Gemella-like NVS HHC5 | G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T | |||

| Abiotrophia spp. | |||||||

| Homology group 1 | |||||||

| ATCC 49176T | Ad | 1 | 100.0 | 6.2 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 0.9 |

| NVS-47 | Ad | 1 | 98.0 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 4.9 | —c |

| YK-3 | Ad | 1 | 90.2 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 5.4 | — |

| TK-1 | Ad | 1 | 71.7 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 4.9 | — |

| PE7 | Ad | 1 | 63.7 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 3.6 | — |

| C8-3 | Ad | 1 | 62.8 | 18.7 | 30.1 | 7.5 | — |

| TK-4 | Ad | 1 | 57.6 | 5.0 | 2.8 | 4.5 | — |

| S1057-1 | Ad | 1 | 57.6 | 5.2 | 4.0 | 3.7 | — |

| YTS2 | Ad | 1 | 55.2 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 3.1 | — |

| Homology group 2 | |||||||

| ATCC 49175T | Aa | 2 | 6.1 | 100.0 | 30.7 | 11.1 | 3.2 |

| C50 | Aa | 2 | 3.2 | 116.2 | 60.5 | 29.1 | — |

| C6-2 | Aa | 3 | 2.4 | 84.6 | 55.4 | 22.8 | — |

| HHC3 | Aa | 2 | 5.5 | 82.7 | 32.1 | 10.6 | — |

| L61 | Aa | 3 | 8.6 | 81.8 | 44.5 | 14.5 | — |

| YTC1 | Aa | 2 | 4.7 | 81.3 | 31.2 | 11.1 | — |

| C1-3 | Aa | 3 | 1.8 | 80.9 | 41.7 | 20.1 | — |

| S961-2 | Aa | 2 | 7.8 | 80.2 | 36.8 | 14.9 | — |

| C2-1 | Aa | 3 | 1.6 | 79.5 | 34.5 | 18.5 | — |

| C1-1 | Aa | 2 | 2.8 | 65.9 | 61.8 | 20.9 | — |

| P6-1 | Aa | 3 | 4.5 | 64.4 | 27.0 | 9.7 | — |

| G40 | Aa | 3 | 4.9 | 60.3 | 20.8 | 8.7 | 6.2 |

| HHP1 | Aa | 2 | 3.1 | 55.6 | 19.0 | 7.3 | — |

| S1058-2 | Aa | 3 | 4.8 | 55.6 | 22.5 | 7.7 | — |

| C2-2 | Aa | 2 | 3.7 | 46.1 | 23.0 | 6.2 | — |

| Homology group 3 | |||||||

| TKT1 | Aa | 2 | 9.5 | 58.7 | 100.0 | 14.9 | 14.9 |

| S49-2 | Aa | 2 | 8.8 | 74.4 | 84.8 | 17.4 | — |

| TKT2 | Gm | 3 | 5.9 | 43.2 | 83.2 | 10.6 | 10.3 |

| NMP2 | Aa | 3 | 9.4 | 75.7 | 81.0 | 19.4 | — |

| C4-1 | Aa | 3 | 2.6 | 49.0 | 77.9 | 21.0 | — |

| HKT1-4 | Aa | 3 | 8.3 | 62.0 | 71.5 | 16.6 | — |

| C5-1 | Aa | 2 | 2.7 | 51.4 | 70.7 | 19.1 | — |

| HKT1-1 | Gm | 3 | 9.2 | 60.1 | 69.0 | 17.8 | 9.5 |

| C4-3 | Aa | 2 | 6.0 | 43.7 | 57.7 | 10.5 | 6.9 |

| P7-4 | Aa | 2 | 7.0 | 53.3 | 53.3 | 14.7 | — |

| ATCC 27527 | Aa | 3 | 4.8 | 33.4 | 40.3 | 8.3 | 3.3 |

| HKT2-2 | Aa | 3 | 4.0 | 25.9 | 32.2 | 7.9 | — |

| YTT3 | Aa | 2 | 3.1 | 20.5 | 22.2 | 4.8 | — |

| Homology group 4 | |||||||

| HHC5 | Gm | 4 | 5.9 | 14.4 | 12.4 | 100.0 | 1.7 |

| S43-1 | Gm | 4 | 2.7 | 30.0 | 24.0 | 85.2 | — |

| YTM1 | Gm | 4 | 5.5 | 16.1 | 10.8 | 83.5 | 2.4 |

| C9-2 | Gm | 4 | 4.9 | 11.7 | 8.8 | 80.7 | 2.9 |

| NMP3 | Aa | 4 | 4.0 | 11.7 | 8.1 | 55.4 | — |

| S943-2 | Aa | 4 | 3.7 | 9.4 | 6.4 | 41.6 | — |

| S1052-1 | Aa | 4 | 4.2 | 8.0 | 5.3 | 38.8 | — |

| DSM 11693T | Aa | 4 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 23.3 | |

| G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T | Gm | — | 5.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 100.0 |

| D. pigrum NCFB 2975T | — | — | 4.9 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 1.1 |

| A. urinae NCFB 2893T | — | — | 2.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 4.0 |

TABLE 3.

PCR products obtained with primers specific for Abiotrophia genotypes

| Strain | No. of strains tested | No. of strains positive for products by PCR with the following primers:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| PR1072 | PR257 | ||

| Abiotrophia spp. | |||

| Homology group 1 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Homology group 2 | 15 | 0 | 15 |

| Homology group 3 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Homology group 4 | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Other spp. | |||

| Bacteriolytic | |||

| Streptococcus intermedius ATCC 27335T | 0 | 1 | |

| Enterococcus durans ATCC 19432T | 0 | 1 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis SS499 | 0 | 1 | |

| Enterococcus hirae ATCC 9790 | 0 | 1 | |

| D. pigrum NCFB 2975 | 0 | 0 | |

| A. urinae NCFB 2893 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nonbacteriolytic | |||

| G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T | 0 | 0 | |

| Gemella haemolysans ATCC 10378T | 0 | 0 | |

| Aerococcus viridans DSM 20340 | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus mitis ATCC 6249 | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus oralis ATCC 9811 | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus sanguinis ATCC 10556T | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus gordonii ATCC 10558T | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus parasanguinis ATCC 15909 | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus anginosus ATCC 33397T | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus constellatus NCTC 10708 | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus cricetus ATCC 19642T | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus ratti ATCC 19645T | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus mutans ATCC 33535T | 0 | 1 | |

| Streptococcus sobrinus OMZ176 | 0 | 0 | |

| Streptococcus salivarius ATCC 13419T | 0 | 0 | |

| Streptococcus bovis ATCC 33317T | 0 | 0 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 21027 | 0 | 1 | |

All the Abiotrophia ATCC strains were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, Va.), the DSM strain was obtained from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (Braunschweig, Germany), and the NCFB strains were obtained from the National Collections of Industrial and Marine Bacteria (Aberdeen, United Kingdom). Strains PE7, C50, L61, and G40 were kindly provided by A. Bouvet (Service de Microbiologie, Hôpital Université, Hôtel-Dieu, Paris, France), and strain NVS-47 was provided by I. van de Rijn (Wake Forest University Medical Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.). The Enterococcus strains were gifts from T. Takada (Tohoku University, School of Dentistry, Sendai, Miyagi, Japan), and Streptococcus bovis strain was from H. Mukasa (Department of Chemistry, National Defence Medical College, Tokorozawa, Saitama, Japan). The other non-Abiotrophia strains were from the collections in our laboratory.

Preparation of genomic DNA.

Abiotrophia strains were normally grown anaerobically at 37°C for 18 h in Todd-Hewitt (TH) broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 0.001% pyridoxal hydrochloride. A. elegans DSM 11693T was cultured in TH broth containing 5% horse serum (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Md.) in place of pyridoxal. The other strains were grown in TH broth. The DNA was extracted from cells and was purified as described previously (19). Briefly, bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 15 min), washed three times in saline, and lysed at 37°C for 1 h with egg white lysozyme (30 U/ml; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and mutanolysin (60 U/ml; Sigma) in 0.1× standard saline citrate (SSC; 1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M trisodium citrate). The sample was then incubated at 60°C for 30 min with 0.8% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Tokyo, Japan) in 1× SSC. The extracted DNA was deproteinized with phenol and with a chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1 [vol/vol]) mixture, digested with RNase (0.1 mg/ml), and precipitated with 70% ethanol.

DNA-DNA hybridization.

A DNA hybridization probe was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (111 TBq/mmol; New England Nuclear Research Co., Boston, Mass.) with an oligolabeling kit (Ready-To-Go DNA Labeling Beads; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden).

Heat-denatured DNAs (10 μg each) of the test strains were blotted onto a membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) with Immunodot (ATTO Co., Tokyo, Japan) and were fixed by UV cross-linking. The membrane was preincubated in a polyethylene bag at 42°C for 1 h in hybridization solution (30% formamide, 0.45 M NaCl, 45 mM trisodium citrate, 25 mM phosphate buffer [pH 6.5], 5× Denhardt's solution [Wako], 0.2 mg of heat-denatured salmon sperm DNA per ml) and was then incubated with heat-denatured probe DNA for 24 h in the hybridization solution. The membrane was washed in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at 52°C for 15 min and in 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS at room temperature for 10 min.

The radioactivity of each blot on the membrane was measured with the BAS1000 bioimaging analyzer system (Fuji Photo Film Co., Tokyo, Japan) according to the unit of radiation dose, photo-stimulated luminescence (PSL), which is proportional to counts per minute. The percent DNA homology for a test strain was calculated by the following equation: 100 × [(test DNA blot PSL − background PSL)/(probe DNA blot PSL − background PSL)].

PCR of genomic DNA sequences.

Nucleotide sequences of the 3.3- and 5.7-kb KpnI fragments of strain TKT1 (homology group 3) DNA were determined, and primers specific for the identification of strains of A. adiacens DNA homology group 3 (PR1072, 5′-GCGTGAATGCCATCTATCAG-3′ and 5′-ATCCACCAGTCTAAGAACTG-3′) and sequences common to strains of the genus Abiotrophia (PR257, 5′-TTATGGTCAGGTGGTAGGAG-3′ and 5′-ACTTGTTGGTCTCGCAGTCA-3′) were synthesized (Amersham Pharmacia Biothch, Tokyo, Japan). Premix Taq (Takara Shuzo Co., Shiga, Japan) containing Taq DNA polymerase and PCR buffer (25 μl), template DNA (0.5 μl), and 0.2 μM primers were added to 50 μl of the PCR mixture. PCR was performed for 30 cycles with a profile of 94°C for 1 min and 64°C for 1 min and for an additional extension at 64°C for 10 min with a thermal cycler (Zymoreactor II; ATTO). The PCR products were stained with 2.5% ethidium bromide in an agarose gel. The correct sizes of the amplicons are 1,072 bp for the A. adiacens homology group 3-specific PCR and 257 bp for the genus Abiotrophia-common PCR.

RFLP analysis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene.

Primers (5′-AGAGTTTGATCATGGCTCAG-3′ and 5′-ACGGGCGGTGTGTAC-3′) which correspond to the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene (positions 8 to 17 and 1405 to 1391, respectively; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were used to amplify the 16S rRNA genes of the test strains (9). PCR was carried out as described above, and the amplicon obtained was digested at 37°C for 40 min with 5 U each of the restriction enzymes, EcoRI, XbaI, and HindIII (Nippon Gene, Osaka, Japan). Profiles of the digests were analyzed in a 2.5% agarose gel after staining with ethidium bromide.

16S rRNA gene sequence.

The PCR product was cloned into a pCR2.1 vector (TA cloning kit; Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, Calif.) and was cut into two EcoRI fragments. Their single-stranded DNAs were obtained by subcloning into M13mp18 and were sequenced by using a Thermo Sequenase premixed cycle sequence kit (Amersham) with an automatic sequencer (SQ5500; Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The sequence of strain TKT1 was compared with those of the other related strains obtained from the data deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ; Mishima, Shizuoka, Japan) and was analyzed to construct a phylogenetic tree by using DDBJ Super Computer (VPP500; Fujitsu, Tokyo, Japan) and the program ClustalW (supplied by DDBJ).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

DNA sequence data for the 16S rRNA genes obtained from DDBJ had the indicated accession numbers: A. defectiva ATCC 49176T, D50541; A. adiacens ATCC 49175T, D50540; A. elegans DSM 11693T, AF016390; G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T, L14327; and E. coli, A14565. The sequence of strain TKT1 has been deposited in DDBJ under accession no. AB022027.

RESULTS

DNA homology.

By using the probe DNAs prepared from two strains each of NVS biotypes 1 to 4 (emended) (7, 17), the 45 strains tested were divided into four homology groups, although DNAs from a few homology group 3 and 4 strains gave low percent homologies (less than 50%) with all eight probe DNA preparations used (Tables 1 and 2). Homology group 1 strains were clearly distinguished from strains of the other groups. Homology group 2 and 3 strains were also separated, although their DNA homology levels were not so distantly related to each other; e.g., the mean ± standard deviation homologies were 75.7% ± 18.2% and 50.1% ± 16.9%, respectively, when the strains were probed with ATCC 49175 DNA. Homology group 4 strains constituted an independent group. In this group, DNA of A. elegans DSM 11693T showed a low degree of homology (23.3%) when its DNA was hybridized with the HHC5 probe DNA, but the HHC5 DNA had a degree of high homology (70.7%) with the DSM 11693 probe DNA. Mean homology values for these two probe DNAs for the homology group 4 strains were very similar (63.6 versus 61.3%; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Mean homology with various probe DNAs

| Homology group | % Homology (mean ± SD) with the probe DNA from:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. defectiva ATCC 49176T (1)a | A. defectiva NVS-47 (1) | A. adiacens ATCC 49175T (2) | A. adiacens TKT1 (2) | A. adiacens ATCC 27527 (3) | A. adiacens NMP3 (3b) | Gemella-like NVS HHC5 (4b) | A. elegans DSM 11693T (4b) | G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T | |

| Abiotrophia spp. | |||||||||

| Homology group 1 | 73.0 ± 18.1c (9)d | *62.1 ± 19.2c (8) | 6.6 ± 4.7 (9) | 7.1 ± 8.8 (9) | 5.0 ± 1.2 (8) | 5.8 ± 1.2 (8) | 4.7 ± 1.3 (9) | 6.6 ± 1.6 (8) | 0.9 (1) |

| Homology group 2 | 4.4 ± 2.0 (15) | 4.8 ± 1.4 (10) | 75.7 ± 18.2c (15) | 36.1 ± 14.1 (15) | 32.5 ± 10.6 (10) | 14.7 ± 4.7 (10) | 14.2 ± 6.7 (15) | 18.4 ± 5.9 (10) | 4.7 ± 2.1 (2) |

| Homology group 3 | 6.3 ± 2.6 (13) | 6.8 ± 2.6 (11) | 50.1 ± 16.9 (13) | 64.9 ± 22.7c (13) | 73.7 ± 26.9c (11) | 18.0 ± 6.3 (11) | 14.1 ± 5.1 (13) | 23.1 ± 7.6 (11) | 9.0 ± 4.3 (5) |

| Homology group 4 | 4.6 ± 1.1 (8) | 3.6 ± 0.8 (7) | 13.6 ± 7.3 (8) | 10.4 ± 6.0 (8) | 8.6 ± 2.6 (7) | 70.1 ± 28.7c (7) | 63.6 ± 27.4c (8) | 61.3 ± 22.3c (7) | 1.9 ± 0.6 (4) |

| G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T | 5.2 (1) | 4.2 (1) | 4.1 (1) | 4.1 (1) | 4.5 (1) | 5.7 (1) | 3.8 (1) | 7.2 (1) | 100.0 (1) |

Biotypes are given in parentheses in the subheads (7).

Biotype 4 in the emended typing system (17).

The mean percent homology values differed significantly from those for the other corresponding homology groups (P < 0.001 by analysis of variance).

Values in parentheses in the table body are the number of strains tested.

Strain ATCC 27527 (homology group 3), which is listed as G. morbillorum in the current ATCC catalog, was revealed to be dependent on pyridoxal for growth and to produce chromophore and bacteriolytic enzyme, and its species was determined to be A. adiacens, although at a rather low confidence level, by the Rapid ID32 STREP system. The strain was not genetically related to the pyridoxal-independent, nonlytic, bona fide strain G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T (Table 1). DNAs from the bacteriolytic but pyridoxal-independent strains Dolosigranurum pigrum NCFB 2975T and Aerococcus urinae NCFB 2893T did not react with any one of the eight Abiotrophia DNA probes.

PCR of genomic DNA sequences.

The genetic variations among the Abiotrophia strains described above, particularly the differentiation of homology group 3 strains from the other strains, were confirmed by PCR-based assays.

The 5.7-kb fragment of KpnI-digested genomic DNA of strain TKT1 (homology group 3) hybridized with DNAs of all Abiotrophia strains, and the 3.3-kb KpnI fragment hybridized only with DNA of homology group 3 strains (data not shown). The base sequences of these fragments were determined, and two sets of PCR primers specific for differentiation of Abiotrophia species, primers PR257 and PR1072, were designed. The product of PCR with primer PR1072 was detected only with the homology group 3 strains, and the product of PCR with primer PR257 was detected with all homology group 1 to 4 strains (Table 3). Thus, in the profile for the product of PCR with primer PR1072, A. adiacens homology group 2 and 3 strains were clearly distinguished from each other and were separated from A. elegans homology group 4 and A. defectiva homology group 1 strains.

Furthermore, the PCR assay with PR1072 was negative for strains of the other six genera and 23 species examined, irrespective of whether they were bacteriolytic or nonbacteriolytic (Table 3). In contrast, the PCR assay with PR257 was positive for non-Abiotrophia strains (four genera and 16 species). These PCR assays were negative for four genera and seven species, including bona fide strain G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T.

16S rRNA gene PCR-RFLP analysis.

Genetic heterogeneities were examined further by use of the 16S rRNA gene PCR-RFLP profiles of the DNA homology groups. All strains of A. adiacens homology group 2 (strains ATCC 49175T, L61, C1-3, and C2-2) and group 3 (strains TKT1, TKT2, C4-1, HKT1-1, and ATCC 27527) tested gave four fragments of 0.21, 0.34, 0.40, and 0.46 kb. In contrast, strains of A. elegans homology group 4 (strains HHC5, YTM1, and DSM 11693T) as well as strains of A. defectiva homology group 1 (strains ATCC 49176T, PE7, and C8-3) had three fragments of 0.34, 0.40, and 0.68 kb. Thus, the four homology groups were not satisfactorily discriminated from each other by the PCR-RFLP analysis in this study, but the 16S rRNA gene of G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T gave a unique profile with three fragments of 0.26, 0.48, and 0.68 kb.

16S rRNA gene sequence homology.

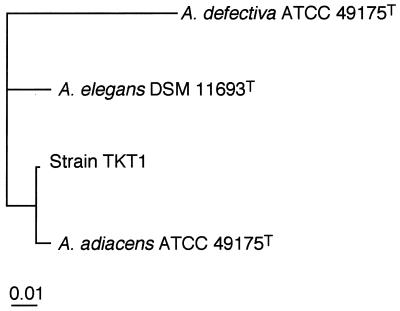

The TKT1 16S rRNA gene sequence was 1,407 bp in length and included the forward and reverse primers in the 5′ and 3′ directions, respectively. A multiple alignment analysis showed that the sequence homologies between TKT1 and the type strains of A. adiacens, A. elegans, A. defectiva, and G. morbillorum were 99, 97, 92, and 85%, respectively. As depicted in an unrooted phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1), DNA homology group 3 strain TKT1 was most closely related to A. adiacens ATCC 49175T (homology group 2) and was considerably more distantly related to the other Abiotrophia species (homology groups 4 and 1), and all the Abiotrophia type strains were remote in terms of their phylogenetic distance from G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T.

FIG. 1.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence-based phylogenetic distance between strain TKT1 (DNA homology group 3) and A. defectiva (homology group 1), A. adiacens (homology group 2), and A. elegans (homology group 4).

Phenotypic characteristics of Abiotrophia genotypes.

As described above, the genus Abiotrophia was differentiated into four genetic categories (designated genotypes 1 to 4). The physiological and serological properties of strains of these genotypes are summarized from the data reported previously (7, 17; Kitada et al.; submitted) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Phenotypic characteristics of strains of Abiotrophia genotypes

| Characteristic | No. of strains

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype 1, A. defectiva(n = 9)a | Genotype 2, A. adiacens(n = 15) | Genotype 3, A. para-adiacens(n = 13) | Genotype 4, A. elegans (n = 8) | |

| Biotypeb | ||||

| Biotype 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Biotype 2 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 0 |

| Biotype 3 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| Biotype 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Pyridoxal dependency for growth | 9 | 15 | 13 | 8 |

| Chromophore production | 9 | 15 | 13 | 8 |

| Bacteriolytic enzyme production | 9 | 15 | 13 | 8 |

| Production of: | ||||

| α-Galactosidase | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| β-Galactosidase | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| β-Glucosidase | 0 | 13 | 10 | 3 |

| N-Acetyl-β-glucosaminidase | 2 | 12 | 6 | 3 |

| β-Glucuronidase | 0 | 8 | 6 | 0 |

| Fermentation of: | ||||

| Trehalose | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pullulan | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tagatose | 4 | 11 | 2 | 0 |

| Sucrose | 9 | 15 | 13 | 8 |

| Arginine dihydrolase | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Serotypec | ||||

| I | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| II, III | 0 | 14 | 2 | 0 |

| IV, V, VI | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| VII, VIII | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| untypeable | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

n is number of strains tested.

By the emended definition (17), biotype 1 is α- and β-galactosidase production but β-glucuronidase nonproduction; biotype 2 is α- and β-galactosidase nonproduction but β-glucuronidase production; biotype 3 is β-glucuronidase nonproduction but generally N-acetylglucosamine production; biotype 4 is α- and β-galactosidase and β-glucuronidase nonproduction but arginine dihydrolase production, irrespective of the identification as G. morbillorum by the Rapid ID32 STREP system (7).

Determined with autoclaved extracts of whole cells with the eight serotyping antisera by immunodiffusion in an agar gel (Kitada et al., submitted).

The genotype 1 strains were restricted to A. defectiva biotype 1 (7): they were distinctly differentiated from the other strains by production of α- and β-galactosidases but a lack of production of either β-glucosidase or β-glucuronidase, fermentation of trehalose and pullulan, and being of serotype I. In contrast, the genotype 4 strains belonged to A. adiacens or Gemella-like biotype 4 (emended) (17). They all produced arginine dihydrolase specifically and usually produced β-glucosidase and/or N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase. All except one of the genotype 4 strains were serotype VII or VIII. Genotypes 2 and 3 were also mixtures of A. adiacens biotype 2 and 3 (emended) strains. The genotype 2 strains generally produced β-glucosidase and N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase and fermented tagatose. Generally, the genotype 3 strains also produced β-glucosidase but did not ferment tagatose. The genotype 2 strains were serotype II or III, whereas the genotype 3 strains were serotype IV, V, or VI or untypeable. Thus, these two genotypes were also phenotypically distinguishable.

DISCUSSION

The Abiotrophia spp. are known to be pyridoxal dependent and to produce chromophore, pyrrolidonyl arylamidase, and bacteriolytic enzyme (2, 4, 7, 12, 16), but it has been known that the genus Abiotrophia represents a heterogeneous group of bacteria (1, 4, 15, 18) and three species and four biotypes of this unique genus have long been known (4, 7, 17). Very recently, during the preparation of this article, a new species has been added to the genus Abiotrophia (10).

The present studies demonstrated that the genus Abiotrophia is divided into four genetic groups. DNA-DNA hybridization analysis (Table 1) and analysis of the PCR product profiles of the genomic DNA and 16S rRNA gene sequences (Fig. 1; Table 3) differentiated the genotype 3 strains from the other strains and separated most strains of A. adiacens identified phenotypically (7) into genotypes 2 and 3, although the two genotypes appear to be rather closely related to each other. These results collectively indicate that along with A. defectiva (genotype 1), A. adiacens (genotype 2), and A. elegans (genotype 4), an additional Abiotrophia species (genotype 3) exists, and that it is most closely related to but distinct from A. adiacens (genotype 2). We propose here that Abiotrophia genotype 3 be called Abiotrophia para-adiacens sp. nov.

A. balaenopterae sp. nov., which was very recently described, was recovered from the lung of a minke whale and has also been shown to be closely related to but distinct from A. adiacens and A. elegans (10). The novel Abiotrophia species ferments pullulan but not sucrose and produces arginine dihydrolase and thus appears to be distinguished from A. para-adiacens which was segregated from A. adiacens (Table 4). The genetic relation between these two new species should be determined in further studies.

The A. para-adiacens (genotype 3) strains constituted a large cluster almost equal in size to the A. adiacens (genotype 2) cluster (Table 1). Both of these species, however, were mixture of biotype 2 and 3 (emended) strains (Tables 1 and 4) and were rather difficult to differentiate by the tests in the rapid identification system. However, the confidence level in the identification of the strain as A. adiacens by the Rapid ID32 STREP system was “excellent” to “good” for most of the genotype 2 strains (80.0%), whereas it was “low” to “id not valid” for most genotype 3 strains (76.9%) (7). In addition, so far tagatose fermentation appears to be a putative key property for the differentiation of these two species: generally, the A. adiacens strains produced β-glucosidase and/or fermented tagatose, while the A. para-adiacens strains produced β-glucosidase and/or did not ferment tagatose. Moreover, most strains of the former species were serotype II or III, but those of the latter species were serotype IV, V, or VI (Table 4). In fact, all except a few serotype II or III strains maintained in our laboratory (39 strains) ferment tagatose (89.7%), whereas only a few tagatose-positive but serotype IV, V, or VI strains (9.4%) are found in A. para-adiacens (Kitada et al., submitted).

In contrast, the remaining two Abiotrophia species were phenotypically distinct. A. elegans, which consisted of emended biotype 4 strains (17) of A. adiacens or Gemella-like NVS (7), was clearly separated from the other Abiotrophia species in that it produced arginine dihydrolase. A. defectiva corresponded strictly to NVS biotype 1 (7) and was also distinct from the others by the production of α- and β-galactosidases and the fermentation of trehalose (4, 7) (Table 4).

Not many A. elegans strains have so far been isolated (14, 15). They occupy ca. 10% or less of the clinical Abiotrophia isolates in our laboratory (17). A. elegans is reported to be more fastidious than the other Abiotrophia spp. and to show unique nutritional requirements: it does not use pyridoxal hydrochloride but uses l-cysteine in TH broth as a growth factor (14). In fact, unlike the other genotype 4 strains, the DSM 11693T substrain that we maintain cannot grow in TH broth and other complex media supplemented with vitamin B6 instead of horse serum (preliminary results). However, the substrain and the genotype 4 oral isolates resembled each other genetically, biochemically, and serologically (Tables 1, 3, and 4), thus forming a homologous cluster, A. elegans. Strains of the other Abiotrophia spp. did not hydrolyze arginine but A. elegans strains did hydrolyze arginine (17) (Table 4). The existence of an atypical A. adiacens strain which produces arginine dihydrolase has been reported (18), and A. elegans has been known to be genetically most closely related to A. adiacens (14, 17).

Strain ATCC 27527, known as G. morbillorum, was identified as A. adiacens by the rapid identification system (Table 1), showed phenotypic characteristics typical of those of Abiotrophia spp. (Table 4), and, together with some Gemella-like NVS and A. adiacens strains (7), belonged to genotype 3 and was not related to G. morbillorum ATCC 27824T (Tables 1 and 3). Thus, strain ATCC 27527 is certainly a member of A. para-adiacens genotype 3. The genera Abiotrophia and Gemella are shown to be located far apart in genetic distance, as estimated by comparison of the 16S rRNA gene sequences (8, 17), but Abiotrophia strains are occasionally identified as G. morbillorum by the rapid identification tests (7) (Table 1) and are misidentified, as in the case of strain ATCC 27527 in the present study.

The PCR-based molecular approaches such as RFLP analysis of universal 16S rRNA PCR products have been attempted for the identification and differentiation of Abiotrophia spp. (8, 11, 15). Primer PR1072 was specific for the separation of A. para-adiacens from A. adiacens as well as A. defectiva and A. elegans. The PCR assay with primer PR1072 was negative for the nonbacteriolytic and bacteriolytic strains of the other six genera and 23 species tested, including 13 species of oral viridans group streptococci and 10 species including a bona fide G. morbillorum strain (Table 3). Thus, the PCR assay with PR1072 would facilitate the specific and sensitive identification of A. para-adiacens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beigton D, Homer K A, Bouvet A, Storey A R. Analysis of enzymatic activities for differentiation of two species of nutritionally variant streptococci, Streptococcus defectivus and Streptococcus adjacens. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1584–1587. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1584-1587.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouvet A, Grimont F, Grimont P A. Streptococcus defectivus sp. nov., and Streptococcus adjacens sp. nov., nutritionally variant streptococci from human clinical specimens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:290–294. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-4-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvet A, Grimont F, Grimont P A. Intraspecies variations in nutritionally variant streptococci: rRNA gene restriction patterns of Streptococcus defectivus and Streptococcus adjacens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:483–486. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-4-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouvet A, Villeroy F, Cheng F, Lamesch C, Williamson R, Gutmann L. Characterization of nutritionally variant streptococci by biochemical tests and penicillin-binding proteins. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:1030–1034. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.6.1030-1034.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coto H, Berk S L. Endocarditis caused by Streptococcus morbillorum. Am J Med Sci. 1984;287:54–58. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198405000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frenkel A, Hirsch W. Spontaneous development of L forms of streptococci requiring secretions of other bacteria or sulphydryl compounds for normal growth. Nature. 1961;191:728–730. doi: 10.1038/191728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanamoto T, Eifuku-Koreeda H, Inoue M. Isolation and properties of bacteriolytic enzyme-producing cocci from the human mouth. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:135–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawamura Y, Hou X G, Sultana F, Liu S, Yamamoto H, Ezaki T. Transfer of Streptococcus adjacens and Streptococcus defectivus to Abiotrophia gen. nov. as Abiotrophia adiacens comb. nov. and Abiotrophia defectiva comb. nov., respectively. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:798–803. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane D J, Pace B, Olsen G J, Stahl D A, Sogin M L, Pace N R. Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6955–6959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.20.6955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawson P A, Foster G, Falsen E, Sjoden B, Collins M D. Abiotrophia balaenopterae sp. nov., isolated from the minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:503–506. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohara N Y, Tajika S, Sasaki M, Kaneko M. Identification of Abiotrophia adiacens and Abiotrophia defectiva by 16S rRNA gene PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2458–2463. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2458-2463.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pompei R, Caredda E, Piras V, Serra C, Pintus L. Production of bacteriolytic activity in the oral cavity by nutritionally variant streptococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1623–1627. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.7.1623-1627.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robert R B, Krieger A G, Schiller N L, Gross K C. Viridans streptococcal endocarditis: role of various species, including pyridoxal-dependent streptococci. Rev Infect Dis. 1979;1:955–966. doi: 10.1093/clinids/1.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roggenkamp A, Abele H M, Trebesius K H, Tretter U, Autenrieth I B, Heesemann J. Abiotrophia elegans sp. nov., a possible pathogen in patients with culture-negative endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:100–104. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.100-104.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roggenkamp A, Leitritz L, Baus K, Falsen E, Heesemann J. PCR for detection and identification of Abiotrophia spp. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2844–2846. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2844-2846.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruoff K L. Nutritionally variant streptococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:184–190. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato S, Kanamoto T, Inoue M. Abiotrophia elegans strains comprise 8% of the nutritionally variant streptococci isolated from the human mouth. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2553–2556. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2553-2556.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein D S, Libertin C R. Genetic heterogeneity among nutritionally deficient streptococci. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;15:281–285. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(92)90011-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taketoshi T, Yakushiji T, Inoue M. Deoxyribonucleic acid relatedness and phenotypic characteristics of oral Streptococcus milleri strains. Microbios. 1993;73:269–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van de Rijn I, George M. Immunochemical study of nutritionally variant streptococci. J Immunol. 1984;133:2220–2225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zierdt C H. Light-microscopic morphology, ultrastructure, culture, and relationship to disease of the nutritional and cell-wall-deficient alpha-hemolytic streptococci. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;15:185–194. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(92)90112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]