Abstract

Membrane contact sites emerged in the last decade as key players in the integration, regulation and transmission of many signals within cells, with critical impact in multiple pathophysiological contexts. Numerous studies accordingly point to a role for mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum contacts (MERCs) in modulating aging. Nonetheless, the driving cellular mechanisms behind this role remain unclear. Recent evidence unravelled that MERCs regulate cellular senescence, a state of permanent proliferation arrest associated with a pro-inflammatory secretome, which could mediate MERC impact on aging. Here we discuss this idea in light of recent advances supporting an interplay between MERCs, cellular senescence and aging.

Subject terms: Senescence, Pathogenesis

This perspective by Ziegler et al. explores the impact of mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum contacts (MERCs) biology on cellular senescence. The authors also explore the potential impacts of MERCs perturbation and how this relates to the increase in cellular senescence observed in common age-related diseases.

Introduction

From the second half of twentieth century, the growing use of subcellular imaging through electron microscopy has allowed the identification of local physical contacts between multiple organelles and/or plasma membrane (PM), called membrane contact sites (MCSs), to the point that the field of “contactology” has emerged in the last decade1–4. Indeed, the first structural observations were extended to point out the multiple functional roles of these MCSs in regulating cellular responses in various pathophysiological conditions4. Firstly, MCSs constitute physical bridges to exchange metabolites (e.g. ions or lipids) between organelles, thus regulating intracellular metabolic fluxes. Secondly and as dynamic molecular microdomains, MSCs create subcellular signalling platforms, allowing local protein modifications and interactions4.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria constitute two key organelles involved in macromolecules synthesis and bioenergetics, but also in stress sensing and integration of cell fate signalling. As they form two independent networks occupying up to 45% of cell volume in eukaryotic cells5,6, ER and mitochondria are involved in multiple MCSs, including contacts between ER and PM, Golgi or peroxysomes, and between mitochondria and PM, lysosomes or lipid droplets4. ER and mitochondria are also able to interact with each other through mitochondria–ER contacts (MERCs)7.

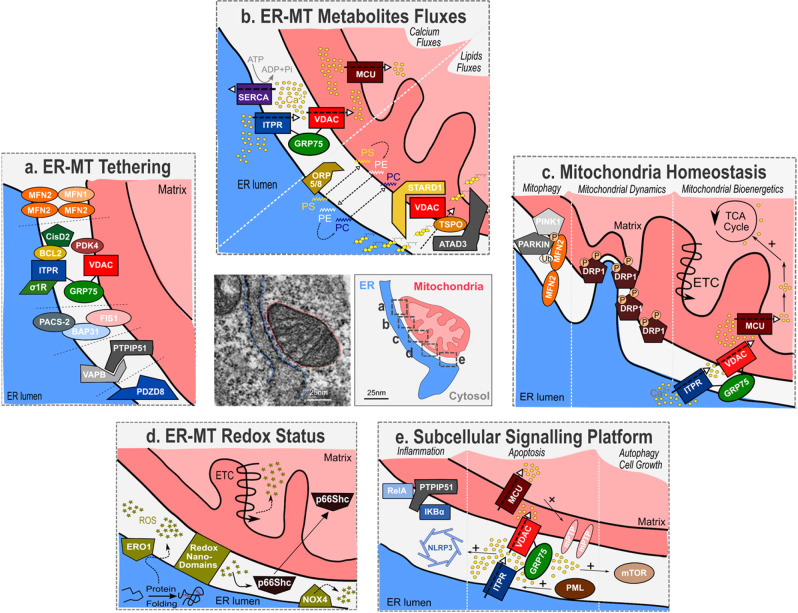

MERCs define tight contacts with a distance shorter than 50 nm specifically between ER and outer mitochondrial membranes7. MERC structures are dynamic structures known to be present in every eukaryotic cells, along approximately 10–15% of all mitochondrial membranes2. Highly heterogeneous among tissues and species, MERCs contain up to hundreds of proteins including tethering/structuring proteins, ion channels, transport binding proteins, enzymes and other signalling proteins2 (Fig. 1). Firstly described in the context of lipid biosynthesis/transfer, MERCs role has been largely extended to other metabolites fluxes, such as calcium8–10. MERCs are involved in lipid metabolism, calcium and redox signalling but also modulate mitochondrial dynamics11, autophagy12, inflammation13 and apoptosis9 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Key components and associated functions of mitochondria–ER contacts.

Electron micrographs of MERCs, ER in blue and mitochondrion in red. a Multiple tethers allow the establishment of MERCs and include MFN1/MFN2 homodimers and heterodimers, ITPR-GRP75-VDAC complex, FIS1/BAP31, VAPB/PTPIP51 and PDZD8. Some MERC-associated proteins, including CisD2, PACS-2, PDK4 and SIGMAR1, interact with tethers to modulate MERCs. b MERCs are at the crossroad of calcium and lipids exchanges between ER and mitochondria. Dynamics of calcium fluxes within MERCs where ITPR, VDAC and MCU calcium channels insure transfer from ER to mitochondria and SERCA pump from cytosol to ER. Phospholipids (PS phosphatidylserine, PE phosphatidylethanolamine, PC phosphatidylcholine) are transferred trough MERCs, notably by ORP5/8 proteins, and cholesterol binds to STARD1/VDAC1/TSPO complex before being imported into the mitochondria. c MERCs regulate mitochondrial homeostasis notably through mitophagy, mitochondrial fission and mitochondrial bioenergetics. PINK1 phosphorylates MFN2, which recruits PARKIN at MERCs. PARKIN ubiquitinates MFN2 to initiate mitophagy. ER wraps mitochondria in initiation sites of fission and recruits DRP1. Calcium cation transfers from ER to mitochondria fuel some calcium-activated TCA cycle dehydrogenases and transporters to promote oxidative phosphorylation. d MERCs control redox status of ER and mitochondria. ERO1 is coupled to protein folding oxidation and generates ROS (H2O2). Redox nanodomains are formed within MERCs interface. NAPDH oxidase NOX4 produces ROS, while p66Shc senses ROS before relocalizing to mitochondria. e MERCs act as subcellular signalling platforms. Members of the NF-κB pathway, RelA and IKκBα, interact with PTPIP51. ITPR-mediated calcium release allows high local concentration of calcium and could participate in the recruitment and activation of mTOR and NLRP3. Promyelocytic Leukemia protein (PML) is found in MERCs fraction.

The use of genetic mouse models targeting MERC components has highlighted MERCs importance in controlling various pathophysiological situations, ranging from vascular remodelling to inflammation and metabolic disorders13–17. More recently, a role of MERCs in aging was suggested by evidences showing a modulation of their quantity and quality with specific age-related diseases or aging18–20. While autophagy and apoptosis are proposed to mediate some of MERCs age-associated effects18,19, whether other critical mechanisms are also involved remains unclear.

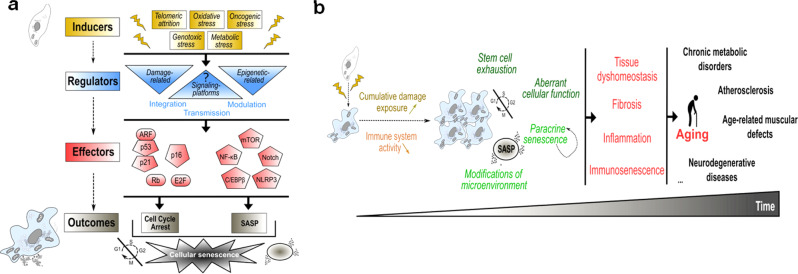

Senescent cells accumulate during aging in various animal models21,22. Cellular senescence can be induced by a myriad of stresses and defines a state of permanent cell proliferation arrest and the concomitant acquisition of a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), including pro-inflammatory factors, pro-fibrotic factors and metalloproteases23 (Fig. 2a). Mechanistically, proliferation arrest is mediated by the activation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, mainly p21 and p16 (Fig. 2a). Besides, the SASP is mostly driven by NF-κB and C/EBPβ, and can be also positively regulated either by Notch, mTOR or NLRP3 pathways24–27 (Fig. 2a). Although these factors regulate cell cycle or SASP, the upstream molecular and subcellular mechanisms regulating them are largely unknown. Notably, signalling platforms mediating the link between stresses sensing and molecular activation of senescence effectors are largely unknown (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. Cellular senescence: from regulation to involvement in aging.

a Multiple stress signals arising from inducers (yellow) are sensed by regulators (blue) that include damage-related and epigenetic-related regulators. Signalling platforms may also act as main regulators. These interconnected regulators integrate, modulate and transmit senescent signals to the downstream effectors that include p53, p21, p16, Rb, E2F, NF-κB, C/EBPβ, mTOR, Notch and NLRP3 (red). These effectors ultimately trigger the main outcomes of cellular senescence (cell cycle arrest and SASP) (grey). SASP Senescence-associated secretory phenotype. b Over time, senescent cells accumulate in tissues due to increased cumulative damage exposure and reduced clearance (through decreased immune system activity). This accumulation leads to stem cell exhaustion, aberrant cellular responses, paracrine senescence (amplifying senescent cells accumulation) and modification of surrounding microenvironment. These cellular alterations lead to tissue dyshomeostasis, fibrosis, systemic inflammation and immunosenescence, finally contributing to aging and age-related pathologies.

Cellular senescence has been early linked to aging, but the functional demonstration of its involvement in it was recent. The accumulation of senescent cells during aging is the concomitant result of both increased intracellular damage and declined senescence immune surveillance28–30 (Fig. 2b). While cell autonomous effects lead to stem cell exhaustion31,32 and aberrant cellular function33, non-cell autonomous effects through SASP can mediate paracrine senescence and modify the surrounding microenvironment. Subsequently, the chronic and systemic accumulation of senescent cells favours tissue dyshomeostasis, fibrosis, inflammation or immunosenescence, ultimately leading to aging and age-associated pathologies, including chronic metabolic disorders, atherosclerosis, age-related muscular defects and neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 2b)34–36. Finding strategies to target and specifically eliminate senescent cells or attenuate their pro-inflammatory SASP, namely with senolytics or senomorphics, has thus become a major challenge in aging research field.

In this perspective, we will present and discuss recent advances suggesting a potential interplay of MERCs and cellular senescence in regulating aging. Based on the fact that MERCs and cellular senescence are both involved in aging and age-related pathologies, we compiled evidence that either modulation of MERC components or increased MERCs formation are pro-senescent signals. Lastly, we propose future directions to elucidate molecular mechanisms behind this emerging role of MERCs in regulating cellular senescence.

MERCs and cellular senescence both control age-associated diseases and aging

While senescent cells accumulate during aging and participate in multiple age-related pathologies21,37,38, numerous clues indicate that MERCs could also play a role in age-associated diseases.

Chronic metabolic disorders

Chronic metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) account for two main contemporary diseases linked to overnutrition and aging39. High-fat diet (HFD) and obese pathological contexts promote senescence in several cell types and tissues including adipose tissue, liver, pancreas or brain promoting insulin-resistance and T2D40–43. Of note, a chronic increase of MERCs was observed in HFD-fed and ob/ob mice, two models exhibiting altered glucose homeostasis, insulin resistance and steatosis44. More strikingly, the use of an artificial MERCs linker45 is able to induce this insulin resistance44. Conversely, reduced MERCs in mice depleted for inositol-triphosphate receptor 2 (ITPR2) are able to improve glucose homeostasis, alleviating age-dependent steatosis and fibrosis46. Accordingly, decreased MERCs through Pdk4 deletion ameliorates glucose homeostasis and insulin response47. Of note, decreased number of hepatic MERCs correlates with reduced mRNA and protein levels of p16 senescence marker46, known to be upregulated during aging37,46. Remarkably and as apparent contradictory result, decreased MERCs using genetic and pharmacological approaches targeting Cyclophilin D (CypD) also perturb insulin response in liver and muscle48,49. Taken together, these data demonstrate that an accurate balanced MERC number is necessary to maintain glucose homeostasis15.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by hepatic fat deposits, evolving from steatosis to fibrosis, cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma50. As T2D, obesity and aging are three main factors of NAFLD, a detrimental role of cellular senescence has been proposed51. Nonetheless, recent functional studies highlighted the detrimental effects of some senolytics, namely Dasatinib and Quercetin, in the context of fully recapitulated NAFLD52, suggesting a complex role of cellular senescence in NAFLD. Furthermore, the elimination of p16High senescent cells induces liver fibrosis if these senescent cells are not replaced53. In addition, senescence of hepatic stellar cells can inhibit their pro-fibrotic roles28, together showing different roles of senescent cells in liver diseases probably depending on the type of senescent cells and on their dynamic54. The importance of MERCs in NAFLD remains unclear16. For instance, Mfn2 knockout was suggested to modulate MERCs quantity, though its precise role is still under debate55, and induces non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, one of the advanced stages of NAFLD, in mouse model. The importance of MERCs in the progression of NAFLD still needs to be further tested using specific MERC tools.

Altogether, all these data strongly indicate that MERCs disruption and modulation of cellular senescence are at the crossroads of age and obesity-related alterations of glucose metabolism and chronic liver dysfunction (Table 1).

Table 1.

MERCs roles in senescence-associated age-related pathologies.

| Roles | Cellular senescence | Mitochondria-ER contacts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | Functional studies | Functional and descriptive studies | |||

| Age-related diseases | Beneficial | Detrimental | Beneficial | Detrimental | |

| Chronic metabolic disorders |

Mice → Functional (p16 TG)33 |

Mice |

Mice →Functional (Mfn2 −/−)16 |

Mice →Functional (MERCs linker)44 →Functional (Pdk4 −/−)47 →Functional (Itpr2 −/−)46 |

|

| Atherosclerosis | — |

Mice |

N/D |

In vitro |

|

| Age-related muscular defects | — |

Mice →Functional (SnCs clearance)37 →Functional (p16 silencing)63 |

Mice →Functional (CisD2 −/−)68 |

N/D | |

| Neuro-degenerative diseases | |||||

| AD | — |

Mice |

Rat →Descriptive80 Fly →Functional (MERCs linker)81 |

In vitro → Descriptive74 In vitro/Mice →Descriptive75 Fly →Functional (Pdzd8 silencing)77 |

|

| PD |

Mice →Functional (SnCs clearance)71 |

In vitro →Descriptive82 Fly →Functional (MERCs linker)83 |

In vitro →Descriptive79 Fly →Descriptive and functional (Itprs silencing/inhibition)78 |

||

| FA | In vitro→Functional (Frataxin silencing)84 | In vitro →Functional (FxnFrataxin silencing)85 | N/D | ||

| Beneficial | Detrimental | Beneficial | Detrimental | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifespan | — |

Mice |

Fly →Functional (MERCs linker)82 Worm →Functional (Grp75 knock-in)97 |

Fly →Functional (MERCs linker)77 Mice →Functional (CypD +/−)94 Mice →Functional (Itpr2 −/−)46 |

|

Summary of the studies reporting a (beneficial or detrimental) role for MERCs and cellular senescence in age-related diseases and lifespan. For each study, the model is indicated in bold and experimental approaches, either descriptive (displaying correlations) or functional (modifying MERCs structure), are indicated underneath. N/D not determined, AD Alzheimer disease, PD Parkinson disease, FA Friedreich’s ataxia, SnCs senescent cells, TG transgenic.

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is also promoted by overnutrition and aging, constituting the major cause of complications of cardiovascular diseases, including stroke and ischaemic heart failure56. Chronic atheromatous plaques are formed by endothelium dysfunction, the accumulation of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) in blood vessels and the subsequent aggregation of macrophages foamy cells and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Endothelial cells, foamy cells and VSMCs in atheromatous plaques display senescence features38,57. The secretome of these senescent cells inhibits promigratory phenotype switching of medial VSMCs and their lesion entry for fibrous cap assembly58. Senolytics treatment rescues this promigratory phenotype-limiting atherosclerosis38,58. Interestingly, recent evidences pointed out that oxLDL treatment of VSMCs or endothelial cells impacts MERCs, notably thanks to PACS-259,60, and mitochondrial calcium accumulation through increased MERCs is proposed to accentuate apoptosis of endothelial cells60. Nonetheless, sub-lethal elevation of mitochondrial calcium can also promote cellular senescence61,62. Taken together, and as correlations, these data suggest that early steps of atheromatous plaques formation involve MERCs modulation and cellular senescence (Table 1).

Age-related muscular defects

Muscular aging is characterized by reduced muscle fibre size and number, associated with loss of motoneurons, and terminally results in muscle dyshomeostasis. Muscular aging is driven at least partly by activation of senescence pathways in muscle stem cells through autophagy defects63,64 and mitochondrial dysfunction65. More importantly, the removal of senescent cells delays this age-associated muscular loss-of-function37. Noteworthy, aged muscle was reported to display a reduction of ER–mitochondria calcium fluxes coupling to higher mitochondrial oxidative stress66. Functionally, potential MERCs modulation through Mfn2 knockout55 has detrimental effects in muscle and leads to age-related sarcopenia67. Furthermore, CisD2 knockout mice also display premature muscle degeneration68. As age-related muscular defects may also come from neuromuscular synaptic loss, it is interesting to note that neuronal Mfn2 is also reduced during aging and its specific deletion is sufficient to trigger skeletal muscle atrophy69. Overall, MERCs integrity or MERC components appear to participate in proper neuromuscular function, as MERCs uncoupling drives premature muscular aging (Table 1).

Neurodegenerative diseases

Aging is considered as the main risk factor driving neurodegenerative diseases, which include among others Alzheimer disease (AD), Parkinson disease (PD), primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). While both neuronal and glial senescent cells accumulate during aging and lead to neural stem cells exhaustion, their elimination significantly ameliorates symptoms of AD, PD and PPMS70–73. MERCs were also studied in the context of neurodegenerative disorders. In AD patients, MERCs are enhanced and three enzymes involved in amyloid β generation (presenilin-1, presenilin-2 and γ-secretase) colocalize at MERCs74,75. Moreover, increased amyloid β induces expression of multiple MERC components including ITPR3 and voltage-dependent channel 1 (VDAC1)75, and presenilin-2 mutants display increased MERCs76. Importantly, pdzd8 deletion decreases MERCs and rescues AD-associated locomotor decline in fly77. In PD, MERCs structure is altered78 and most of PD-associated proteins, such as α-synuclein, Parkin or PINK1, are found in MERCs fraction79. Furthermore, α-synuclein enhances MERCs and mitochondrial calcium uptake80. Taken together, these later studies suggest a detrimental role of MERCs in AD and PD. Noteworthy, multiple studies point out also decreased MERCs in PD- and AD-associated conditions, underlying also a beneficial role of these MERCs. For example, recent live FRET imaging of rat neurons displays decreased average length of tight MERCs in an AD model81. The use of an artificial linker in vivo also rescues locomotor defects in AD model in fly82. In a PD context, α-synuclein displays opposite role in MERCs formation as it can also decrease VAPB–PTPIP51 interaction83. Moreover, loss of parkin-induced ubiquitination of MFN2 is responsible for an inefficient coupling of MERCs and restoration of MERCs rescues motricity defects in a PD model in fly84. While no consensus, all these results support that MERCs dyshomeostasis could contribute to AD and PD. Finally, reduced MERCs are found in a model of Friedreich’s ataxia (FA), accompanied by decreased mitochondrial calcium and cellular senescence85,86, according to the importance of physiological basal mitochondrial calcium in sustaining mitochondrial bioenergetics87. Collectively, these data indicate that MERCs dysregulation and cellular senescence could be linked to neurodegenerative disorders. Nonetheless, while cellular senescence displays detrimental roles, MERCs roles are still under debate because of a low number of functional studies (Table 1).

Systemic aging and lifespan

Senescent cells accumulate during aging in spite of multifactorial heterogeneity in the speed and level of their accumulation88. Removal of these senescent cells or reduction of their SASP result in a decrease of some age-related alterations as described above. Most importantly, this can also result in delayed aging and improve in both lifespan and healthspan37,38,89–93 (Table 1). Altogether, cellular senescence thus appears to be a key cellular phenotype driving tissue dysfunction and aging (Fig. 2b). Recent reviews have depicted how MERCs dyshomeostasis may be involved in some age-related pathologies and aging18,19. Among genetic mouse models studied in the context of MERCs dyshomeostasis, CypD knockout and Mfn2 knockout67,94–96 have been largely studied, while their specific role in MERCs is still under debate. Interestingly, lifespan of CypD haploinsufficient but not CypD knockout mice is increased compared to their control WT littermates94. Lifespan of Mfn2 knockout mice, although displaying premature muscular aging67, was not monitored. Noteworthy, C. elegans lifespan is extended by knock-in of Hsp9a, encoding the GRP75 (Glucose-Related Protein 75) scaffold protein binding to ER and mitochondria through ITPR and VDAC channels97. Though not clearly demonstrated, GRP75 may enhance MERCs in this model, and its muscle constitutive expression could counteract deleterious effects caused by MERCs disruption in muscle, as previously discussed97. More recently, the contribution of ER-mitochondrial calcium flux to aging in mice and worms was assessed. On one side, deletion of the murine ER-calcium release channel ITPR2 reduces MERCs and age-related alterations in males and females and it extends lifespan only in females46. On the other side, atf6 loss-of-function in worms results in sustained ITPR-mediated ER-mitochondria fluxes enhancing lifespan98. Altogether, these studies demonstrate that dyshomeostasis in both MERCs and ER-mitochondrial calcium fluxes may promote aging-associated phenotypes. Studies using genetic models targeting MERC components face major limits. For instance, whether Mfn2 knockout reduces or increases MERCs number is still controversial55,99–101 even if it does not question the ability of MFN2 to contribute to MERCs. Furthermore, phenotypes driven by deletion of MERC components might be in some cases MERC-independent. As two major examples, MFN2 is associated to mitochondrial fusion55 and GRP75 (mtHsp70/Mortalin/GRP75) acts as a mitochondrial chaperone determinant for the quality control of intra-mitochondria folding of matrix-directed precursor proteins, these functions being independent of their roles in MERCs102. For these reasons, future works led on MERC components would need to clarify MERC-dependent and MERC-independent roles. In order to avoid MERC-independent roles, an alternative consists in using artificial linker/uncoupler of MERCs2. Whether forcing or uncoupling MERCs in vivo through artificial linkers/uncouplers may promote/delay aging and previously established age-related pathologies remains so far unclear. Two recent studies led on Drosophila melanogaster reported contradictory results on the same MERC-associated age-related pathology, namely AD. Using a synthetic linker, the two studies suggest either an extension82 or a reduction77 of lifespan. According to these results, while one reports that increasing MERCs ameliorates cognitive functions82, the other demonstrates that reducing MERCs has a similar effect, heightening mitophagy77. Clarifying the functional role of MERCs in physiological or pathological premature aging using specific linker/uncoupler in vivo is thus one avenue that would need to be explored in the future (Table 1).

Overall, these studies indicate that MERCs and cellular senescence can control similar age-related pathologies and establish multiple correlations between MERCs and cellular senescence in regulating aging (Table 1). That is the reason why the hypothesis of a role of MERCs in contributing to cellular senescence, which could at least partially mediate the impact of MERCs on aging, has recently emerged. Interestingly, numerous studies have reported that key MERC components are able to regulate features of cellular senescence.

MERC components modulate key senescence features

MERCs are heterogeneous in terms of number and activity. MERCs composition is also highly variable according to recent proteomic data in different cell types2,103–105, challenging its specific study. Nonetheless, MERCs are regulated by abundance of scaffold proteins, defining MERCs quantity, and by other interface proteins, interacting with each other and including calcium channels, receptors and kinases, underlying MERCs activity and function. Noteworthy, quantity and activity/function of MERCs are interrelated as some enzymes and calcium channels, for example Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 4 (PDK4) and ITPRs, are able to regulate MERCs integrity46,47,106. Finally, numerous MERC components are regulated by protein interactions such as ITPR3-TOM70107, VDAC2-CDKAP4108, ITPR2-FUNDC1109, but also by post-translational modifications such as DRP1 SUMOylation by MAPL/MUL1110, which further adds a layer of complexity in the organisation and function of MERCs.

Role of MERCs scaffold/tethering proteins in cellular senescence

MERCs establishment is regulated by multiple scaffold and tethering factors that include among others MFN2, GRP75-ITPRs-VDACs, FIS1-BAP31, VAPB-PTPIP51, PDZD8, CYPD and SIGMAR12,111 (Fig. 1). MFN1 and MFN2 have been linked functionally to senescence112. MFN1 is a target of ubiquitin ligase MARCH5 and accumulates in MARCH5-deficient cells, which display hyperfused mitochondria and senescence features113. On the contrary, downregulation of Mfn1 extends replicative lifespan114. Concerning Mfn2, its depletion boosts cellular proliferation of both B cell lymphoma cell line and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs)115. MFN2 mediates hyperfused mitochondria and promotes senescence of mesenchymal stem cells116. Concerning haematopoietic stem cells, opposite results highlight that Mfn2 deletion induces defect in long-term lymphoid repopulation117, though no senescence markers were investigated. Overall, these data indicate that alterations of MFN1 and MFN2, key regulators of MERCs number, are able to regulate senescence-associated phenotypes. However, MFN1 and MFN2 are, independently of MERCs, also involved in mitochondrial fusion, and whether their effects on senescence depends on their function inside the MERCs is still unknown.

Concerning ITPR–GRP75–VDAC complex, GRP75 overexpression leads to increased replicative lifespan through downregulation of RAS and reduced phosphorylation of ERK2118,119 and ITPRs promote cellular senescence46,61,62, as it will be further discussed below.

BAP31 is an ER-resident chaperone transmembrane protein, found in MERCs fraction, forming a bridge with FIS1120 and known mainly to regulate apoptosis121. Although the functional implication of BAP31 has never been investigated in the context of cellular senescence, its deletion reduces cell proliferation of colon cancer cells122 and it is found to be upregulated in both replicative and X-ray induced senescence of fibroblasts123.

Overall, alterations of key MERC tethers are able to drive features of cellular senescence. Aside from these reports, further studies on additional tethers such as VAPB, PTPIP51 or PDZD8, or proteins participating in MERCs structure such as SIGMAR1 and CYPD, need to be conducted to determine whether they could also regulate cellular senescence.

Role of MERC components involved in ER–mitochondria exchanges in cellular senescence

MERCs constitute a privileged site for exchanges of metabolites, including calcium and lipids, which have been recently involved in the regulation of cellular senescence.

Calcium exchanges at MERCs interface are regulated by multiple calcium channels, namely ITPRs (ITPR1, 2 and 3) in ER, VDACs (1, 2 and 3) at the OMM and MCU at the IMM for the mitochondrial influx and SERCA (1, 2) for ER influx (Fig. 1). At the ER interface, a few studies evaluated the impact of ITPRs in functionally regulating cellular senescence. ITPR2 knockdown results in the escape from oncogene-induced senescence (OiS) in human mammary epithelial cells (hMECs) but also delays replicative senescence in normal human fibroblasts61. Itpr2 knockout MEFs display also a reduction of senescence markers associated with a reduced mitochondrial calcium accumulation over passages46. More strikingly, ITPR2 abrogation, which reduces some age-related alterations and increases mouse lifespan as described above, also lowers cellular senescence46. Concerning ITPR1 and ITPR3, their knockdown is also able to delay senescence61. Altogether these data point out a key role of ITPRs in the regulation of cellular senescence. Regarding VDAC1/2/3 or SERCA ATPases pumps, no studies reported their role in cellular senescence, in contrary to MCU, the IMM mitochondrial import calcium channel, which participates in OiS, probably through ITPR2-released calcium61. Importantly, decreased MERCs and deficient mitochondrial calcium uptake through depletion of frataxin lead to cellular senescence in neuroblastoma cells, highlighting also the importance of MERCs to ensure minimum ER–mitochondrial calcium fluxes85,86.

Besides calcium, MERCs constitute exchange sites for numerous other molecules such as phospholipid and cholesterol2 (Fig. 1). Oxysterol-Binding Protein-Related Protein 5 (ORP5) and 8 (ORP8) are ER-anchored proteins involved in phospholipids exchanges at MERCs. Strikingly, ORP5 administers phospholipid and calcium transfers, while ORP8 function is exclusively limited to phospholipid transfers. The constitutive expression of ORP5 boosts cell proliferation124, while its knockdown promotes senescence, through an increase of mitochondrial calcium uptake125. Of note, the sole downregulation of the exclusive phospholipid-exchanger ORP8 does not affect senescence125.

Taken together, the results suggest that MERCs calcium transfers could be predominant on phospholipid transfers in the regulation of senescence. Still, other functional studies on key MERCs proteins involved in the transfer of lipids between ER and mitochondria need to be performed in order to describe their potential contribution through MERCs in the regulation of cellular senescence.

Aside from tethers and transport proteins, multiple other MERCs proteins have been functionally involved in the regulation of cellular senescence, and especially of the SASP. Among SASP regulators, mTOR complex and inflammasome are respectively necessary for IL1-α translation and processing25,26. Interestingly, mTOR complex and NLRP3 are both found in MERCs126,127. Noteworthy, MERCs constitute hotspots for cytosolic calcium signalling and both mTOR and NLRP3 can be activated by calcium128,129. The hypothesis of a role for MERCs in calcium-mediated activation of mTOR and NLRP3, and subsequent SASP promotion, still needs to be tested. In addition to mTOR and NLRP3, two classical MERC resident proteins, namely PTIPT51 and PACS-2, are involved in the regulation of the NF-κB pathway which drives the pro-inflammatory SASP. While the MERCs tether PTPIP51 interacts with RelA and IKBα130, the induction of NF-κB programme upon irradiation in Pacs-2 −/− thymocytes is abrogated, through blunted phosphorylation of IκBα, IκBβ and RelA131. Taken together, these data suggest that the mTOR, NLRP3 and NF-κB pathway could regulate SASP through MERC-dependent activation, even if more precise investigations should be conducted in the future to decipher this potential role.

p66Shc was largely studied in the context of senescence and also in relation with aging. Decreased p66Shc delays replicative senescence of human diploid fibroblasts132, and its increase promotes hepatocyte senescence and subsequent senescence-driven steatosis133. In the context of aging, p66Shc is phosphorylated at Serine 36 in an age-dependent manner in old animals, and strongly correlates with enhanced ROS production134. Though p66Shc intracellular localization is still under debate, frequently found in mitochondria, MERCs or PM-associated membranes, it has been suggested that p66Shc accumulates in MERCs with age before re-localizing to the mitochondria134. Exogenous oxidative stress is able to relocate p66Shc to the nucleus, where the oxidative stress response is integrated to establish a senescence response135–137. Collectively, these studies highlight the role of p66Shc as a sensor and regulator of cellular senescence and lifespan135–137.

Promyelocytic Leukemia protein (PML), an essential component of the PML nuclear bodies (PML-NBs), critically regulates cellular senescence138. Not only present in PML-NBs, PML is also located in cytoplasm, in ER and in MERCs139. PML limits phosphorylation of ITPR3, leading to dampened ER-mitochondria calcium flux and subsequent failed apoptosis139. A possible role of PML localization at MERCs in its pro-senescence function could be considered as well.

Two other MERCs proteins, CisD2 and PACS-2, were found to also regulate cell proliferation arrest, one of the key features of cellular senescence. CisD2, an ER protein located at the MERCs interface through Bcl2–IP3R interactions140, is necessary for proliferation of induced-pluripotent stem cells141. The knockdown of PACS-2, mentioned above for its ability to regulate NF-κB activation, also delays cell proliferation arrest induced by DNA damage–p53–p21 axis in thymocytes142. Additional cell types and complementary senescence markers should be monitored to better evaluate the contribution of CisD2 and PACS-2 in the modulation of the senescence fate.

Altogether these data indicate that several MERCs components, including tethers, calcium channels and others, regulate key features of cellular senescence (Table 2), although it still has to be proven that this action is MERC-dependent. Of note, it seems particularly interesting that some key SASP regulators are found associated and activated at MERCs interface. Overall, these data strongly suggest that MERCs regulate the senescence fate, which is an idea that has been recently evaluated.

Table 2.

Regulation of senescence-associated features by MERC-associated proteins.

| Function | Name | Effect of experiment on protein levels/activity (−/+) | Effect on MERCs number | Effects on ER and/or MT | Effects on senescence-associated phenotype | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER-MT TETHERING | MFN1 | + (Stabilization) | N/D | Increased MT mass | Induction of senescence | 113 |

| MFN2 | − (KO) | N/D | N/D | Delayed RS | 115 | |

| GRP75 | + (OE) | N/D | N/D | Delayed RS | 118 | |

| FIS1 | − (shRNA) | N/D | Hyperfused MT | Induction of senescence | 157 | |

| + (OE) | N/D | Rescue hyperfused MT | Rescue of DFO-induced senescence | 156 | ||

| ER-MT METABOLITES TRANSFERS | ITPR1 | − (shRNA) | N/D | N/D | Limited OiS | 61 |

| ITPR2 | − (shRNA) | N/D | Limited ER-MT calcium fluxes/ROS/MMD | Limited OiS and delayed RS | 61 | |

| − (siRNA) | N/D | Limited ER-MT calcium fluxes/MT ROS | Reduction of senescence | 62 | ||

| − (KO) | Decreased | Limited ER-MT calcium fluxes/MT ROS/MMD | Reduction of senescence | 46 | ||

| ITPR3 | − (shRNA) | N/D | N/D | Reduction of OiS | 61 | |

| MCU | − (shRNA) | N/D | Limited ER-MT calcium fluxes | Reduction of OiS | 61 | |

| ORP5 | − (siRNA) | N/D | Alteration of MT morphology and reduced OXPHOS | Induction of senescence | 125 | |

| SIGNALLING PROTEINS | PACS-2 | − (KO) | N/D | N/D | Resistance to p53-dependent CCA and NF-κB programme | 131,142 |

| p66Shc | − (KO) | N/D | N/D | Delayed RS | 135 | |

| CISD2 | − (KO) | N/D | Enhanced MMD | Reduction of cell proliferation | 141 | |

| RelA | − (shRNA) | N/D | N/D | Inhibition of SASP | 24 | |

| NLRP3 | − (KO) | N/D | N/D | Reduction of age-dependent increase of p53 and p21 | 27 | |

| mTOR | − (Rapa) | N/D | N/D | Inhibition of NF-κB-dependent SASP | 26 | |

| PML | − (KO) | N/D | N/D | Resistance to OiS | 138 | |

| − (KO) | N/D |

Limited ITPR3 phosphorylation Reduced ER-MT calcium fluxes |

N/D | 139 |

Summary of the studies reporting a potential role for MERC-associated proteins involved in tethering, ER-MT metabolites transfers and signalling in the regulation of features of cellular senescence. For each study, the effect of MERCs protein dysregulation (upregulation + or downregulation−) on MERCs number and also ER and mitochondria are indicated. If investigated, the effects on features of cellular senescence are reported. N/D not determined, KO knockout, OE overexpression, Rapa Rapamycin, ER endoplasmic reticulum, MT mitochondria, OXPHOS oxidative phosphorylation, MMD mitochondrial membrane depolarization, OiS ocogene-induced senescence, RS replicative senescence, CCA cell cycle arrest.

MERCs regulate cellular senescence

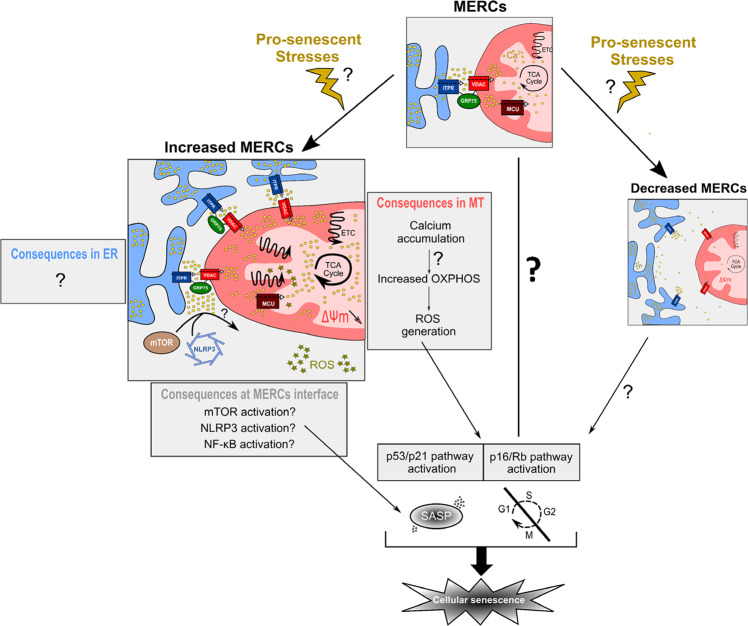

A pro-senescent role for MERCs: potential mechanistic

Increased evidence of the role of MERCs proteins during aging and in cellular senescence raised the question of the importance of MERCs in regulating cellular senescence. Expression of an artificial linker tightening ER and mitochondrial membranes45 led to premature cellular senescence in normal human fibroblasts, with a NF-κB-dependent SASP46. This cellular senescence was accompanied by increased mitochondrial calcium and functionally involved ROS production, as antioxidant treatment rescued the onset of this premature senescence46. Downstream, p53 was necessary to induce senescence46. The importance of MERCs in established senescence models (replicative senescence, OiS, oxidative stress-induced senescence) should be critically tested in further investigations.

Noteworthy, deletion of MERC-associated proteins (such as MFN2, Frataxin or ORP5) and potential MERCs uncoupling were also proposed to mediate a senescence phenotype85,86,113,125, whether these effects are dependent of MERCs is unknown. To properly assess whether MERCs decrease may also impact senescence, it will be necessary to evaluate the impact of a specific MERCs spacer, such as FATE1143, in senescence models. While forcing MERCs induces a ROS- and p53-dependent senescence through an increased mitochondrial calcium uptake, an opposite role of MERCs uncoupling is nonetheless still unknown (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Mechanistic working model of MERC-induced senescence.

Under physiological stimuli, MERCs allow proper calcium transfer from ER (in blue) to mitochondria (MT, in red). Upon pro-senescent stresses or other stimulations, MERCs number could be modified. Increased MERCs number (left panel) leads to mitochondrial calcium accumulation, a potential increased oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and an increased production of ROS activating p53/p21 and p16/Rb pathways to mediate cell cycle arrest and Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP), driven partly by NF-κB. In the meantime, whether increased MERCs would participate in ER-associated phenotypes, such as ER stress, is so far not known. In the cytosol-associated part, enhanced MERCs interface may activate three main SASP regulators, including mTOR, NLRP3 or NF-κB subunits. Finally, whether decreased MERCs number (right panel) may regulate cellular senescence and what could be the associated mechanisms remain to be critically addressed.

How MERCs dyshomeostasis mechanistically drives cellular senescence remains an open question, but involves necessarily at least one of the three MERCs sub-compartments, i.e., mitochondrion, ER and apposed cytosol.

Mitochondrion side—An important number of studies report that senescent cells display mitochondrial abnormalities and various mitochondrial dysfunctions promote cellular senescence112. These mitochondrial dysfunctions are largely driven by non-exclusive mechanisms which include among others defective ETC, excessive ROS production, abnormal dynamics and altered mitophagy112. Nonetheless, the upstream mechanisms driving these mitochondrial dysfunctions during cellular senescence remain so far elusive.

In line with increased evidence of the role of calcium fluxes within the cell and specifically between ER and mitochondria46,61,62,144,145, calcium signalling appears to be an interesting candidate to mediate the senescence phenotype. In human endothelial cells and MEFs, replicative senescence is characterized by an increased MERCs number and a subsequent accumulation of mitochondrial calcium46,146. Accordingly, replicative senescent neurons display also an increased transfer of calcium from the ER to mitochondria accompanied by an upregulation of MCU expression147. Reduction of this mitochondrial calcium accumulation by knocking down ITPR261,62 or MCU61 inhibits the establishment of cellular senescence in several cell models, including hMEC and fibroblasts61,62. When excessively accumulated, mitochondrial calcium leads to mitochondrial membrane depolarization, ROS generation and subsequent cellular senescence46,61,62,144 or apoptosis148. Of note, accumulation of mitochondrial calcium through the suppression of mitochondria calcium efflux by knocking down the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger triggers superoxide generation and neuronal apoptosis, driving AD-associated pathology149.

Mitochondrial calcium regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics mainly through its transfer through MERCs87,150,151. Indeed, mitochondrial dehydrogenases present EF-hand calcium binding necessary for enzymatic activity152. As mitochondrial calcium homeostasis is necessary in order to maintain mitochondrial bioenergetics85,87,151,153, massive MERCs uncoupling may also trigger mitochondrial dysfunction. For instance, reduced MERCs through CypD knockout48,154 leads to dysregulation of TCA cycle and fatty acid β-oxidation95, while no senescence markers were monitored in these studies. Interestingly, this dual role of the importance of a balanced ER-mitochondrial calcium influx has been recapitulated in the context of neural stem cell development in fly. Indeed, depletion of Miro, an OMM GTPase, reduces mitochondrial calcium and leads to mitochondrial metabolic impairment, whereas its constitutive expression triggers mitochondrial calcium overload and apoptosis155. Both conditions impaired neural stem cells lineage progression, though no senescence markers were investigated155.

To summarize the role of MERC-mediated mitochondrial calcium influx in cellular senescence, it appears that an altered calcium transfer from ER to mitochondria triggers mitochondrial dysfunction, eventually leading to cellular senescence. At this stage, most of the data support the hypothesis of an enhanced calcium influx into the mitochondria during cellular senescence, which could be mediated notably by increased MERCs, without excluding the hypothesis that reduced MERCs could also elicit pro-senescent signals (Fig. 3). Apart from calcium, whether lipid fluxes at MERCs interface are involved in mitochondrial alterations promoting cellular senescence remains an open question.

Beyond metabolites transfers, MERCs also promote early steps of mitochondrial fission through ER wrapping of mitochondria at future fission sites11. Reducing mitochondrial fission is able to induce senescence in normal cells112,156,157. Though no evidences were clearly established, MERC uncoupling could lead to accumulation of hyperfused damaged mitochondria by fission and subsequent mitophagy defects, eventually mediating a senescence phenotype. Nonetheless, whether the sole MERC uncoupling induces senescence features should be critically addressed (Fig. 3).

ER side—ER stress is a potent candidate to also mediate senescence phenotype158. This role is suggested by the fact that ER stress is observed in several models of senescence in vitro, such as OiS159–162 and UV- or X-ray-induced senescence159,163, but also in several senescence-associated pathological contexts, including therapy-induced senescence (TIS) in lymphomas164, diabetic nephropathy165, age-related sarcopenia166 and osteoarthritis167. ER stress may result from a persistent unfolded protein response (UPR) or from a luminal calcium depletion168 and includes three main sensors: PERK, ATF6 and IRE1168. Interestingly, MFN2 depletion in MEFs heightens the activity of the three ER stress branches169. Furthermore, PERK interacts with MFN2 and is found in MERCs fraction to transduce apoptosis triggered by ROS-mediated ER stress170. MFN2 is able to interact with PERK in normal conditions to restrain its activity. Remarkably, another ER-anchored MERCs tether, namely VAPB, interacts with ATF6, repressing transcription of its target genes171. Finally, IRE1 regulates lipid composition at MERCs and thus subsequent calcium fluxes151. Taken together, these data indicate cross-talks between MERC components and ER stress169,170. Concerning calcium fluxes, MERCs may decrease ER calcium content. ER calcium is determinant for chaperones involved in protein folding, such as Calreticulin or BiP/GRP78, and variations of ER calcium content subsequently lead to UPR and ER stress172. How ER stress is regulated upon modulation of MERCs and how it participates in cellular senescence should be addressed in the future.

Altogether, these data strongly suggest the importance of mitochondria in participating in the regulation of senescence phenotype, while ER contribution is still barely understood. Finally, some non-ER and non-mitochondria resident proteins modulating senescence features can be located in MERCs, as for example NLRP3, mTOR or PML. Therefore, MERCs could regulate cellular senescence by impacting signalling pathways in the cytosol through these proteins.

MERCs: a dynamic platform for integrating pro-senescence signals?

MERCs are constantly modified and some pro-senescence signals were shown to affect MERCs protein levels. For example, persistent DNA damage response at telomeres during replicative senescence and X-ray-induced DNA damage upregulate the MERC tether BAP31 at mRNA levels123. Noteworthy, expression of ITPR2, the most efficient channel for ER-to-mitochondria calcium transfer106, is upregulated by other pro-senescence stresses, including oncogenic stress61, oxidative stress173 or high-fat diet44. Aside from transcriptional and translational regulations, some MERCs proteins were found relocated, as previously mentioned for p66Shc, or activated upon stresses inducing cellular senescence. Taken together, these data indicate that pro-senescence signals may modify MERCs composition and function. Proteomic analysis of MERCs during cellular senescence induced by different stresses will be needed to appreciate MERCs rearrangement in composition in response to pro-senescence signals.

MERCs quantity is also regulated upon senescence-inducing stresses. Increased MERCs were found during replicative senescence of endothelial cells and MEFs46,146. MERCs quantity may be regulated by redox stress, as, for example, antioxidant treatment rescues MERCs deficiency in FA model85,86. Importantly, DNA damage promotes the formation of MERCs to promote intrinsic cell death through enhanced mitochondrial calcium uptake174. At sublethal doses, oxidative stress and DNA damage also mediate cellular senescence23.

Altogether, it seems that MERCs are highly modulated in response to pro-senescence signals. Further studies need to be performed in order to evaluate how MERCs evolve during senescence in quantity, composition and function. Upon senescence-inducing stresses, MERCs could behave as platforms integrating these signals and modulating signalling to other subcellular compartments such as mitochondria, cytosol and nucleus where senescence features are regulated.

Perspectives and conclusion

In conclusion, the observation that MERCs and cellular senescence play a crucial role in aging and age-associated diseases led to the hypothesis that MERCs may regulate aging at least partly through cellular senescence, and indeed, experimental data support that MERCs are key platforms controlling cellular senescence. This idea was first supported by studies showing a role for MERC components in cellular senescence and was strengthened by the observation that forcing MERCs with an artificial linker induces senescence in vitro. MERCs trigger this phenotype through ROS production and p53 activation. However how MERC-mediated mitochondrial calcium accumulation impacts mitochondrial functions and ROS generation and whether other calcium-independent processes are involved remains unknown.

Artificial linkers are powerful tools to investigate MERC functions but face some limitations. Some improvements have been obtained by the generation of inducible linker175,176 when compared to the constitutive artificial linker45,46. However, these linkers do not reflect many aspects of MERC complexity. Indeed, they do not allow to control the distance between ER and mitochondria (<50 nm but heterogeneous)177. This thickness is defined as the width of the cleft separating OMM from ER, and subdivides MERCs in tight (~10 nm) and loose (~25–40 nm) structures178. For instance, while loose MERCs were reported to promote ER–mitochondrial calcium transfers, tight MERCs were shown to limit them177. Beyond the distance between ER and mitochondria, the complexity of MERC composition and their plasticity critically orientate the effects of MERCs. There is then an urgent need to develop new tools to better manipulate MERCs to better understand the role of MERCs in controlling cellular senescence.

Whether MERC dysregulation is at the origin of cellular senescence which in turn results in pathological outcomes needs further investigations. For instance, the effects of linkers and spacers allowing to modulate MERCs need to be monitored in vivo, on cellular senescence and aging. Further studies will have to assess in these models and in in vivo models harbouring a knockout of MERC components (Mfn2 −/−, CisD2 −/−, CypD −/−, Pdk4 −/−, Pacs-2 −/−...) if the impact of these linkers, spacers and knockout on aging-associated alterations depends on cellular senescence. Crossing these models with models less prone to senescence or treating them with chemical compounds able to suppress features of senescent cells (senomorphics) or eliminate them (senolytics) would precise the importance of cellular senescence in the phenotypes induced by MERCs alterations.

We are then proposing that modulating MERCs could be a new avenue to modulate senescence, associated-pathological alterations and healthspan. Either the death of senescent cells could be promoted by increasing ER to mitochondria calcium flux or their accumulation could be reduced by lowering this flux. Chemical compounds targeting MERCs already exist179 and could be tested for these capacities.

In summary, we presented and discussed new insights into the potential role of MERCs in regulating cellular senescence which could participate in MERCs impact on aging. As it has been proposed for cellular senescence, we propose that the principle of antagonistic pleiotropy could be also applied to MERCs, which have a beneficial role for the cells when tightly regulated and which could be detrimental when dysregulated, leading to cellular senescence and associated consequences such as aging and age-related diseases. More broadly, this new field of research on the role of MERCs in cellular senescence and aging has highlighted the importance of communication between different compartments, sometimes mediated through contacts sites such as MERCs. This will pave the way to investigate the role of other MCSs, such as PM-ER, PM-MT or Lysosome-MT, in the context of cellular senescence and aging.

Acknowledgements

We thank Fondation ARC and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM) for their support.

Author contributions

D.V.Z., N.M. and D.B. conceived the concepts described in this perspective. D.V.Z. drew the figures and wrote the introduction section and the main topic sections with the assistance of N.M. and D.B., and N.M. and D.B. wrote the Perspectives/conclusion section with the assistance of D.V.Z.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review Information Communications Biology thanks J. Cesar Cardenas and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Eve Rogers.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dorian V. Ziegler, Email: dorian.ziegler@unil.ch

Nadine Martin, Email: nadine.martin@lyon.unicancer.fr.

David Bernard, Email: david.bernard@lyon.unicancer.fr.

References

- 1.Helle SCJ, et al. Organization and function of membrane contact sites. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1833:2526–2541. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Csordás G, Weaver D, Hajnóczky G. Endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondrial contactology: structure and signaling functions. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:523–540. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scorrano L, et al. Coming together to define membrane contact sites. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1287. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09253-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prinz WA, Toulmay A, Balla T. The functional universe of membrane contact sites. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21:7–24. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0180-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarz DS, Blower MD. The endoplasmic reticulum: structure, function and response to cellular signaling. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2016;73:79–94. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2052-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaasik A, Safiulina D, Zharkovsky A, Veksler V. Regulation of mitochondrial matrix volume. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C157–C163. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00272.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowland AA, Voeltz GK. Endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria contacts: function of the junction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:607–615. doi: 10.1038/nrm3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell RM, Ballas LM, Coleman RA. Lipid topogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 1981;22:391–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchi S, et al. Mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum calcium homeostasis and cell death. Cell Calcium. 2018;69:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elustondo P, Martin LA, Karten B. Mitochondrial cholesterol import. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2017;1862:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman, J. R. et al. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science334, 358–362 (2011). This study in yeast demonstrated the importance of MERCs in early steps of mitochondrial fission processing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Yang, M. et al. Mitochondria-associated ER membranes—the origin site of autophagy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.8, 595 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Missiroli S, et al. Mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs) and inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0027-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Annunziata I, Sano R, d’Azzo A. Mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) and lysosomal storage diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:328. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rieusset J. The role of endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contact sites in the control of glucose homeostasis: an update. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:388. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0416-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernández-Alvarez MI, et al. Deficient endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial phosphatidylserine transfer causes liver disease. Cell. 2019;177:881–895.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gӧbel, J. et al. Mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum contacts in reactive astrocytes promote vascular remodeling. Cell Metab. 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.03.005 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Janikiewicz J, et al. Mitochondria-associated membranes in aging and senescence: structure, function, and dynamics. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:332. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0105-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moltedo O, Remondelli P, Amodio G. The mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum contacts and their critical role in aging and age-associated diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019;7:172. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petkovic M, O’Brien CE, Jan YN. Interorganelle communication, aging, and neurodegeneration. Genes Dev. 2021;35:449–469. doi: 10.1101/gad.346759.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herbig U, Ferreira M, Condel L, Carey D, Sedivy JM. Cellular senescence in aging primates. Science. 2006;311:1257–1257. doi: 10.1126/science.1122446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C, et al. DNA damage response and cellular senescence in tissues of aging mice. Aging Cell. 2009;8:311–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorgoulis V, et al. Cellular senescence: defining a path forward. Cell. 2019;179:813–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chien, Y. et al. Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-κB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev.25, 2125–2136 (2011). This paper was the first to demonstrate the role of NF-κB pathway in the regulation of pro-inflammatory SASP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Acosta JC, et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:978–990. doi: 10.1038/ncb2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laberge R-M, et al. MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:1049–1061. doi: 10.1038/ncb3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marín-Aguilar F, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome suppression improves longevity and prevents cardiac aging in male mice. Aging Cell. 2020;19:e13050. doi: 10.1111/acel.13050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krizhanovsky V, et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell. 2008;134:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang, T.-W. et al. Senescence surveillance of pre-malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. Nature479, 547–551 (2011). This original study was among the first in vivo clues demonstrating the role of cellular senescence as a tumour suppressing mechanism. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Lujambio A, et al. Non-cell-autonomous tumor suppression by p53. Cell. 2013;153:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H, et al. Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science. 2007;317:803–806. doi: 10.1126/science.1143578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castilho RM, Squarize CH, Chodosh LA, Williams BO, Gutkind JS. mTOR mediates Wnt-induced epidermal stem cell exhaustion and aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helman A, et al. p16(Ink4a)-induced senescence of pancreatic beta cells enhances insulin secretion. Nat. Med. 2016;22:412–420. doi: 10.1038/nm.4054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz-Espín D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:482–496. doi: 10.1038/nrm3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schafer MJ, et al. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14532. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miao J, et al. Wnt/β-catenin/RAS signaling mediates age-related renal fibrosis and is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Aging Cell. 2019;18:e13004. doi: 10.1111/acel.13004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baker DJ, et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Childs BG, et al. Senescent intimal foam cells are deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science. 2016;354:472–477. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spinelli R, et al. Molecular basis of ageing in chronic metabolic diseases. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2020;43:1373–1389. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogrodnik M, et al. Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15691. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogrodnik, M. et al. Obesity-induced cellular senescence drives anxiety and impairs neurogenesis. Cell Metab.10.1016/j.cmet.2018.12.008 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Aguayo-Mazzucato C, et al. Acceleration of β cell aging determines diabetes and senolysis improves disease outcomes. Cell Metab. 2019;30:129–142.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer AK, et al. Targeting senescent cells alleviates obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction. Aging Cell. 2019;0:e12950. doi: 10.1111/acel.12950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arruda AP, et al. Chronic enrichment of hepatic ER-mitochondria contact sites leads to calcium dependent mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity. Nat. Med. 2014;20:1427–1435. doi: 10.1038/nm.3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Csordás G, et al. Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174:915–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ziegler DV, et al. Calcium channel ITPR2 and mitochondria–ER contacts promote cellular senescence and aging. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:720. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20993-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thoudam T, et al. PDK4 augments ER–Mitochondria contact to dampen skeletal muscle insulin signaling during obesity. Diabetes. 2019;68:571–586. doi: 10.2337/db18-0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tubbs E, et al. Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM) integrity is required for insulin signaling and is implicated in hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2014;63:3279–3294. doi: 10.2337/db13-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tubbs E, et al. Disruption of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM) integrity contributes to muscle insulin resistance in mice and humans. Diabetes. 2018;67:636–650. doi: 10.2337/db17-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M. Recent insights into hepatic lipid metabolism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Prog. Lipid Res. 2009;48:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papatheodoridi A-M, Chrysavgis L, Koutsilieris M, Chatzigeorgiou A. The role of senescence in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and progression to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2020;71:363–374. doi: 10.1002/hep.30834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raffaele M, et al. Mild exacerbation of obesity- and age-dependent liver disease progression by senolytic cocktail dasatinib + quercetin. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021;19:44. doi: 10.1186/s12964-021-00731-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grosse L, et al. Defined p16High senescent cell types are indispensable for mouse healthspan. Cell Metab. 2020;32:87–99.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huda N, et al. Hepatic senescence, the good and the bad. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019;25:5069–5081. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i34.5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Filadi R, Pendin D, Pizzo P. Mitofusin 2: from functions to disease. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:330. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang JC, Bennett M. Aging and atherosclerosis: mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence. Circ. Res. 2012;111:245–259. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gorenne I, Kavurma M, Scott S, Bennett M. Vascular smooth muscle cell senescence in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;72:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Childs BG, et al. Senescent cells suppress innate smooth muscle cell repair functions in atherosclerosis. Nat. Aging. 2021;1:698–714. doi: 10.1038/s43587-021-00089-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moulis, M. et al. The multifunctional sorting protein PACS-2 controls mitophagosome formation in human vascular smooth muscle cells through mitochondria-ER contact sites. Cells8, 638 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Yu S, et al. PACS2 is required for ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell apoptosis by regulating mitochondria-associated ER membrane formation and mitochondrial Ca2+ elevation. Exp. Cell Res. 2019;379:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wiel C, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium release through ITPR2 channels leads to mitochondrial calcium accumulation and senescence. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3792. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma, X. et al. The nuclear receptor RXRA controls cellular senescence by regulating calcium signaling. Aging Cell17, e12831 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Sousa-Victor P, et al. Geriatric muscle stem cells switch reversible quiescence into senescence. Nature. 2014;506:316–321. doi: 10.1038/nature13013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.García-Prat L, et al. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature. 2016;529:37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature16187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Habiballa L, Salmonowicz H, Passos JF. Mitochondria and cellular senescence: Implications for musculoskeletal ageing. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019;132:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.10.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fernandez-Sanz C, et al. Defective sarcoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria calcium exchange in aged mouse myocardium. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1573. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sebastián D, et al. Mfn2 deficiency links age-related sarcopenia and impaired autophagy to activation of an adaptive mitophagy pathway. EMBO J. 2016;35:1677–1693. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen Y-F, et al. Cisd2 deficiency drives premature aging and causes mitochondria-mediated defects in mice. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1183–1194. doi: 10.1101/gad.1779509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang L, et al. Mitofusin 2 regulates axonal transport of calpastatin to prevent neuromuscular synaptic elimination in skeletal muscles. Cell Metab. 2018;28:400–414.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bussian TJ, et al. Clearance of senescent glial cells prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline. Nature. 2018;562:578. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0543-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chinta SJ, et al. Cellular senescence is induced by the environmental neurotoxin Paraquat and contributes to neuropathology linked to Parkinson’s disease. Cell Rep. 2018;22:930–940. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nicaise AM, et al. Cellular senescence in progenitor cells contributes to diminished remyelination potential in progressive multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:9030–9039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818348116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang P, et al. Senolytic therapy alleviates Aβ-associated oligodendrocyte progenitor cell senescence and cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:719. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0372-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Area-Gomez E, et al. Upregulated function of mitochondria-associated ER membranes in Alzheimer disease. EMBO J. 2012;31:4106–4123. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hedskog L, et al. Modulation of the endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria interface in Alzheimer’s disease and related models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:7916–7921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300677110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Filadi R, et al. Presenilin 2 modulates endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling by tuning the antagonistic effect of Mitofusin 2. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2226–2238. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hewitt, V. L. et al. Decreasing pdzd8-mediated mitochondrial-ER contacts in neurons improves fitness by increasing mitophagy. Preprint at bioRxiv10.1101/2020.11.14.382861 (2020).

- 78.Lee K-S, et al. Altered ER–mitochondria contact impacts mitochondria calcium homeostasis and contributes to neurodegeneration in vivo in disease models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E8844–E8853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721136115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gómez-Suaga P, Pedro JMB-S, González-Polo RA, Fuentes JM, Niso-Santano M. ER–mitochondria signaling in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0079-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Calì T, Ottolini D, Negro A, Brini M. α-Synuclein controls mitochondrial calcium homeostasis by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:17914–17929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.302794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Martino Adami, P. V. et al. Perturbed mitochondria–ER contacts in live neurons that model the amyloid pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell Sci.132 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Garrido-Maraver, J., Loh, S. H. Y. & Martins, L. M. Forcing contacts between mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum extends lifespan in a Drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Open9, bio047530 (2020). This in vivo work using synthetic linker in fly constituted the first evidence of the beneficial role of MERCs in lifespan in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Paillusson S, et al. Synuclein binds to the ER–mitochondria tethering protein VAPB to disrupt Ca2+ homeostasis and mitochondrial ATP production. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134:129–149. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1704-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Basso V, et al. Regulation of ER-mitochondria contacts by Parkin via Mfn2. Pharmacol. Res. 2018;138:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bolinches-Amorós, A., Mollá, B., Pla-Martín, D., Palau, F. & González-Cabo, P. Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by frataxin deficiency is associated with cellular senescence and abnormal calcium metabolism. Front Cell Neurosci8, 124 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Rodríguez LR, et al. Oxidative stress modulates rearrangement of endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contacts and calcium dysregulation in a Friedreich’s ataxia model. Redox Biol. 2020;37:101762. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cárdenas C, et al. Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell. 2010;142:270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tuttle CSL, et al. Cellular senescence and chronological age in various human tissues: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Cell. 2020;19:e13083. doi: 10.1111/acel.13083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Farr JN, et al. Targeting cellular senescence prevents age-related bone loss in mice. Nat. Med. 2017;23:1072–1079. doi: 10.1038/nm.4385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Deursen JM. van. Senolytic therapies for healthy longevity. Science. 2019;364:636–637. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Griveau A, Wiel C, Ziegler DV, Bergo MO, Bernard D. The JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib delays premature aging phenotypes. Aging Cell. 2020;19:e13122. doi: 10.1111/acel.13122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Beaulieu, D. et al. Phospholipase A2-Receptor 1 promotes lung-cell senescence and emphysema in obstructive lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2000752 10.1183/13993003.00752-2020 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 93.Zhang Y, Zhang J, Wang S. The role of Rapamycin in healthspan extension via the delay of organ aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021;70:101376. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vereczki V, et al. Cyclophilin D regulates lifespan and protein expression of aging markers in the brain of mice. Mitochondrion. 2017;34:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tavecchio, M., Lisanti, S., Bennett, M. J., Languino, L. R. & Altieri, D. C. Deletion of Cyclophilin D impairs β-oxidation and promotes glucose metabolism. Sci. Rep. 5, 15981 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Shum LC, et al. Cyclophilin D knock-out mice show enhanced resistance to osteoporosis and to metabolic changes observed in aging bone. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0155709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yokoyama K, et al. Extended longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans by knocking in extra copies of hsp70F, a homolog of mot-2 (mortalin)/mthsp70/Grp75. FEBS Lett. 2002;516:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02470-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Burkewitz K, et al. Atf-6 regulates lifespan through ER-mitochondrial calcium homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108125. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.de Brito OM, Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 2008;456:605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature07534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Filadi R, et al. Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria coupling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E2174–E2181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504880112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Leal NS, et al. Mitofusin-2 knockdown increases ER-mitochondria contact and decreases amyloid β-peptide production. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016;20:1686–1695. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Srivastava S, Vishwanathan V, Birje A, Sinha D, D’Silva P. Evolving paradigms on the interplay of mitochondrial Hsp70 chaperone system in cell survival and senescence. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019;54:517–536. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2020.1718062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cho I-T, et al. Ascorbate peroxidase proximity labeling coupled with biochemical fractionation identifies promoters of endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondrial contacts. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:16382–16392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.795286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cho KF, et al. Split-TurboID enables contact-dependent proximity labeling in cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:12143–12154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919528117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kwak C, et al. Contact-ID, a tool for profiling organelle contact sites, reveals regulatory proteins of mitochondrial-associated membrane formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:12109–12120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916584117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bartok A, et al. IP 3 receptor isoforms differently regulate ER-mitochondrial contacts and local calcium transfer. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11646-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Filadi R, et al. TOM70 sustains cell bioenergetics by promoting IP3R3-mediated ER to mitochondria Ca2+ transfer. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:369–382.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Harada T, et al. Palmitoylated CKAP4 regulates mitochondrial functions through an interaction with VDAC2 at ER-mitochondria contact sites. J. Cell Sci. 2020;133:jcs249045. doi: 10.1242/jcs.249045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wu S, et al. Binding of FUN14 domain containing 1 with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes maintains mitochondrial dynamics and function in hearts in vivo. Circulation. 2017;136:2248–2266. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Prudent J, et al. MAPL SUMOylation of Drp1 stabilizes an ER/mitochondrial platform required for cell death. Mol. Cell. 2015;59:941–955. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hirabayashi Y, et al. ER-mitochondria tethering by PDZD8 regulates Ca2+ dynamics in mammalian neurons. Science. 2017;358:623–630. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ziegler DV, Wiley CD, Velarde MC. Mitochondrial effectors of cellular senescence: beyond the free radical theory of aging. Aging Cell. 2015;14:1–7. doi: 10.1111/acel.12287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Park Y-Y, et al. Loss of MARCH5 mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligase induces cellular senescence through dynamin-related protein 1 and mitofusin 1. J. Cell. Sci. 2010;123:619–626. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Son JM, et al. Mitofusin 1 and optic atrophy 1 shift metabolism to mitochondrial respiration during aging. Aging Cell. 2017;16:1136–1145. doi: 10.1111/acel.12649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]