Abstract

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome caused by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) poses a severe challenge to healthcare and is a significant public health issue worldwide. This study intends to examine the change in the awareness level of HIV among adolescents. Furthermore, this study examined the factors associated with the change in awareness level on HIV-related information among adolescents over the period. Data used for this study were drawn from Understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults, a longitudinal survey on adolescents aged 10–19 in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The present study utilized a sample of 4421 and 7587 unmarried adolescent boys and girls, respectively aged 10–19 years in wave-1 and wave-2. Descriptive analysis and t-test and proportion test were done to observe changes in certain selected variables from wave-1 (2015–2016) to wave-2 (2018–2019). Moreover, random effect regression analysis was used to estimate the association of change in HIV awareness among unmarried adolescents with household and individual factors. The percentage of adolescent boys who had awareness regarding HIV increased from 38.6% in wave-1 to 59.9% in wave-2. Among adolescent girls, the percentage increased from 30.2 to 39.1% between wave-1 & wave-2. With the increase in age and years of schooling, the HIV awareness increased among adolescent boys ([Coef: 0.05; p < 0.01] and [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01]) and girls ([Coef: 0.03; p < 0.01] and [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01]), respectively. The adolescent boys [Coef: 0.06; p < 0.05] and girls [Coef: 0.03; p < 0.05] who had any mass media exposure were more likely to have an awareness of HIV. Adolescent boys' paid work status was inversely associated with HIV awareness [Coef: − 0.01; p < 0.10]. Use of internet among adolescent boys [Coef: 0.18; p < 0.01] and girls [Coef: 0.14; p < 0.01] was positively associated with HIV awareness with reference to their counterparts. There is a need to intensify efforts in ensuring that information regarding HIV should reach vulnerable sub-groups, as outlined in this study. It is important to mobilize the available resources to target the less educated and poor adolescents, focusing on rural adolescents.

Subject terms: Health care, Health services, Public health

Introduction

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) caused by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) poses a severe challenge to healthcare and is a significant public health issue worldwide. So far, HIV has claimed almost 33 million lives; however, off lately, increasing access to HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and care has enabled people living with HIV to lead a long and healthy life1. By the end of 2019, an estimated 38 million people were living with HIV1. More so, new infections fell by 39 percent, and HIV-related deaths fell by almost 51 percent between 2000 and 20191. Despite all the positive news related to HIV, the success story is not the same everywhere; HIV varies between region, country, and population, where not everyone is able to access HIV testing and treatment and care1. HIV/AIDS holds back economic growth by destroying human capital by predominantly affecting adolescents and young adults2.

There are nearly 1.2 billion adolescents (10–19 years) worldwide, which constitute 18 percent of the world’s population, and in some countries, adolescents make up as much as one-fourth of the population3. In India, adolescents comprise more than one-fifth (21.8%) of the total population4. Despite a decline projection for the adolescent population in India5, there is a critical need to hold adolescents as adolescence is characterized as a period when peer victimization/pressure on psychosocial development is noteworthy6. Peer victimization/pressure is further linked to risky sexual behaviours among adolescents7,8. A higher proportion of low literacy in the Indian population leads to a low level of awareness of HIV/AIDS9. Furthermore, the awareness of HIV among adolescents is quite alarming10–12.

Unfortunately, there is a shortage of evidence on what predicts awareness of HIV among adolescents. Almost all the research in India is based on beliefs, attitudes, and awareness of HIV among adolescents2,12. However, few other studies worldwide have examined mass media as a strong predictor of HIV awareness among adolescents13. Mass media is an effective channel to increase an individuals’ knowledge about sexual health and improve understanding of facilities related to HIV prevention14,15. Various studies have outlined other factors associated with the increasing awareness of HIV among adolescents, including; age16–18, occupation18, education16–19, sex16, place of residence16, marital status16, and household wealth index16.

Several community-based studies have examined awareness of HIV among Indian adolescents2,10,12,20–22. However, studies investigating awareness of HIV among adolescents in a larger sample size remained elusive to date, courtesy of the unavailability of relevant data. Furthermore, no study in India had ever examined awareness of HIV among adolescents utilizing information on longitudinal data. To the author’s best knowledge, this is the first study in the Indian context with a large sample size that examines awareness of HIV among adolescents and combines information from a longitudinal survey. Therefore, this study intends to examine the change in the awareness level of HIV among adolescents. Furthermore, this study examined the factors associated with a change in awareness level on HIV-related information among adolescents over the period.

Data and methods

Data

Data used for this study were drawn from Understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults (UDAYA), a longitudinal survey on adolescents aged 10–19 in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh23. The first wave was conducted in 2015–2016, and the follow-up survey was conducted after three years in 2018–201923. The survey provides the estimates for state and the sample of unmarried boys and girls aged 10–19 and married girls aged 15–19. The study adopted a systematic, multi-stage stratified sampling design to draw sample areas independently for rural and urban areas. 150 primary sampling units (PSUs)—villages in rural areas and census wards in urban areas—were selected in each state, using the 2011 census list of villages and wards as the sampling frame. In each primary sampling unit (PSU), households to be interviewed were selected by systematic sampling. More details about the study design and sampling procedure have been published elsewhere23. Written consent was obtained from the respondents in both waves. In wave 1 (2015–2016), 20,594 adolescents were interviewed using the structured questionnaire with a response rate of 92%.

Moreover, in wave 2 (2018–2019), the study interviewed the participants who were successfully interviewed in 2015–2016 and who consented to be re-interviewed23. Of the 20,594 eligible for the re-interview, the survey re-interviewed 4567 boys and 12,251 girls (married and unmarried). After excluding the respondents who gave an inconsistent response to age and education at the follow-up survey (3%), the final follow-up sample covered 4428 boys and 11,864 girls with the follow-up rate of 74% for boys and 81% for girls. The effective sample size for the present study was 4421 unmarried adolescent boys aged 10–19 years in wave-1 and wave-2. Additionally, 7587 unmarried adolescent girls aged 10–19 years were interviewed in wave-1 and wave-223. The cases whose follow-up was lost were excluded from the sample to strongly balance the dataset and set it for longitudinal analysis using xtset command in STATA 15. The survey questionnaire is available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=4163718&version=2.0 & https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=4163720&version=2.0.

Outcome variable

HIV awareness was the outcome variable for this study, which is dichotomous. The question was asked to the adolescents ‘Have you heard of HIV/AIDS?’ The response was recorded as yes and no.

Exposure variables

The predictors for this study were selected based on previous literature. These were age (10–19 years at wave 1, continuous variable), schooling (continuous), any mass media exposure (no and yes), paid work in the last 12 months (no and yes), internet use (no and yes), wealth index (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest), religion (Hindu and Non-Hindu), caste (Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe, Other Backward Class, and others), place of residence (urban and rural), and states (Uttar Pradesh and Bihar).

Exposure to mass media (how often they read newspapers, listened to the radio, and watched television; responses on the frequencies were: almost every day, at least once a week, at least once a month, rarely or not at all; adolescents were considered to have any exposure to mass media if they had exposure to any of these sources and as having no exposure if they responded with ‘not at all’ for all three sources of media)24. Household wealth index based on ownership of selected durable goods and amenities with possible scores ranging from 0 to 57; households were then divided into quintiles, with the first quintile representing households of the poorest wealth status and the fifth quintile representing households with the wealthiest status25.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was done to observe the characteristics of unmarried adolescent boys and girls at wave-1 (2015–2016). In addition, the changes in certain selected variables were observed from wave-1 (2015–2016) to wave-2 (2018–2019), and the significance was tested using t-test and proportion test26,27. Moreover, random effect regression analysis28,29 was used to estimate the association of change in HIV awareness among unmarried adolescents with household factors and individual factors. The random effect model has a specific benefit for the present paper's analysis: its ability to estimate the effect of any variable that does not vary within clusters, which holds for household variables, e.g., wealth status, which is assumed to be constant for wave-1 and wave-230.

Results

Table 1 represents the socio-economic profile of adolescent boys and girls. The estimates are from the baseline dataset, and it was assumed that none of the household characteristics changed over time among adolescent boys and girls.

Table 1.

Socio-economic characteristics of study population, 2015–2016.

| Background characteristics | Adolescent boys | Adolescent girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Percentage | Sample | Percentage | |

| Wealth Index | ||||

| Poorest | 414 | 11.4 | 756 | 12.3 |

| Poorer | 699 | 19.9 | 1065 | 17.2 |

| Middle | 908 | 22.3 | 1476 | 21.1 |

| Richer | 1195 | 23.8 | 2118 | 24.9 |

| Richest | 1212 | 22.7 | 2192 | 24.4 |

| Religion | ||||

| Hindu | 3729 | 84.9 | 5674 | 76.7 |

| Non-Hindu | 699 | 15.1 | 1933 | 23.3 |

| Caste | ||||

| SC/ST | 1080 | 27.5 | 1561 | 23.3 |

| OBC | 2518 | 54.8 | 4403 | 55.1 |

| Others | 830 | 17.8 | 1643 | 21.6 |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 1989 | 16.8 | 3424 | 17.0 |

| Rural | 2439 | 83.2 | 4183 | 83.0 |

| States | ||||

| Uttar Pradesh | 2300 | 63.9 | 4135 | 72.2 |

| Bihar | 2128 | 32.1 | 3472 | 27.8 |

| Total | 4428 | 100.0 | 7607 | 100.0 |

SC/ST: Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe; OBC: Other Backward Class.

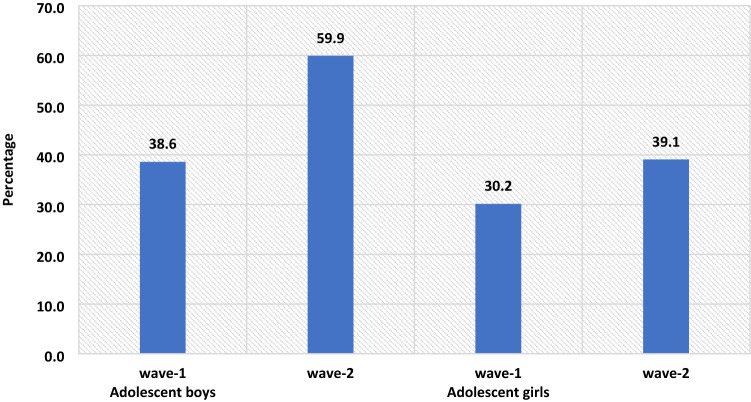

Figure 1 represents the change in HIV awareness among adolescent boys and girls. The percentage of adolescent boys who had awareness regarding HIV increased from 38.6% in wave-1 to 59.9% in wave-2. Among adolescent girls, the percentage increased from 30.2% in wave-1 to 39.1% in wave-2.

Figure 1.

The percenate of HIV awareness among adolescent boys and girls, wave-1 (2015–2016) and wave-2 (2018–2019).

Table 2 represents the summary statistics for explanatory variables used in the analysis of UDAYA wave-1 and wave-2. The exposure to mass media is almost universal for adolescent boys, while for adolescent girls, it increases to 93% in wave-2 from 89.8% in wave-1. About 35.3% of adolescent boys were engaged in paid work during wave-1, whereas in wave-II, the share dropped to 33.5%, while in the case of adolescent girls, the estimates are almost unchanged. In wave-1, about 27.8% of adolescent boys were using the internet, while in wave-2, there is a steep increase of nearly 46.2%. Similarly, in adolescent girls, the use of the internet increased from 7.6% in wave-1 to 39.3% in wave-2.

Table 2.

Summary statistics for explanatory variables used in the analysis of UDAYA wave-1 and wave-2.

| Variables | Adolescent boys | p value | Adolescent girls | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave-1 | Wave-2 | Wave-1 | Wave-2 | |||

| Mean age (years) | 14.8 | 17.8 | <0.001 | 15.8 | 18.8 | <0.001 |

| Mean schooling (years) | 7.4 | 9.3 | <0.001 | 8.0 | 9.5 | <0.001 |

| Any mass media | 97.5 | 98.0 | 0.028 | 89.8 | 93.0 | <0.001 |

| Paid work in last 12 months | 35.3 | 33.5 | 0.648 | 22.5 | 22.9 | 0.613 |

| Internet use | 27.8 | 74.0 | <0.001 | 7.6 | 39.3 | <0.001 |

| Sample (N) | 4428 | 4428 | 7607 | 7607 | ||

Table 3 represents the estimates from random effects for awareness of HIV among adolescent boys and girls. It was found that with the increases in age and years of schooling the HIV awareness increased among adolescent boys ([Coef: 0.05; p < 0.01] and [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01]) and girls ([Coef: 0.03; p < 0.01] and [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01]), respectively. The adolescent boys [Coef: 0.06; p < 0.05] and girls [Coef: 0.03; p < 0.05] who had any mass media exposure were more likely to have an awareness of HIV in comparison to those who had no exposure to mass media. Adolescent boys' paid work status was inversely associated with HIV awareness about adolescent boys who did not do paid work [Coef: − 0.01; p < 0.10]. Use of the internet among adolescent boys [Coef: 0.18; p < 0.01] and girls [Coef: 0.14; p < 0.01] was positively associated with HIV awareness in reference to their counterparts.

Table 3.

Estimated effects of explanatory variables on the awareness of HIV from random effect models.

| Variables | Adolescent boys (10–19) at wave-1 | Adolescent girls (10–19) at wave-1 |

|---|---|---|

| Random effect Coefficient (CI) |

Random effect Coefficient (CI) |

|

| Individual characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | 0.05*** (0.05, 0.06) | 0.03*** (0.02, 0.03) |

| Schooling (years) | 0.04*** (0.04, 0.05) | 0.04*** (0.04, 0.05) |

| Any mass media exposure | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 0.06** (0.01, 0.13) | 0.03** (0.01, 0.06) |

| Paid work | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | − 0.01* (− 0.03, 0.01) | 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.02) |

| Internet use | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 0.18*** (0.16, 0.20) | 0.14*** (0.12, 0.16) |

| Household characteristics | ||

| Wealth Index | ||

| Poorest | Ref | Ref |

| Poorer | 0.04** (0.00, 0.07) | 0.00 (− 0.03, 0.03) |

| Middle | 0.05*** (0.02, 0.09) | 0.03** (0.00, 0.06) |

| Richer | 0.08*** (0.04, 0.11) | 0.10*** (0.07, 0.13) |

| Richest | 0.12*** (0.09, 0.16) | 0.19*** (0.16, 0.22) |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | Ref | Ref |

| Non-Hindu | − 0.01 (− 0.03, 0.02) | − 0.09*** (− 0.11, − 0.08) |

| Caste | ||

| Others | Ref | Ref |

| SC/ST | − 0.01 (− 0.04, 0.02) | 0.00 (− 0.02, 0.02) |

| OBC | − 0.01 (− 0.03, 0.02) | 0.04*** (0.02, 0.07) |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | Ref | Ref |

| Rural | − 0.03*** (− 0.05, − 0.02) | − 0.09*** (− 0.11, − 0.08) |

| States | ||

| Uttar Pradesh | Ref | Ref |

| Bihar | 0.04*** (0.03, 0.06) | 0.02*** (0.01, 0.04) |

| Year | ||

| 2015–2016 | Ref | Ref |

| 2018–2019 | − 0.10*** (− 0.12, − 0.08) | − 0.10*** (− 0.12, − 0.09) |

| sigma_u | 0.145 | 0.231 |

| sigma_e | 0.345 | 0.325 |

| rho | 0.150 | 0.335 |

**if p < 0.05 ***if p < 0.001; Ref Reference; CI confidence interval; SC/ST Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe; OBC: Other Backward Class.

The awareness regarding HIV increases with the increase in household wealth index among both adolescent boys and girls. The adolescent girls from the non-Hindu household had a lower likelihood to be aware of HIV in reference to adolescent girls from Hindu households [Coef: − 0.09; p < 0.01]. Adolescent girls from non-SC/ST households had a higher likelihood of being aware of HIV in reference to adolescent girls from other caste households [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01]. Adolescent boys [Coef: − 0.03; p < 0.01] and girls [Coef: − 0.09; p < 0.01] from a rural place of residence had a lower likelihood to be aware about HIV in reference to those from the urban place of residence. Adolescent boys [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01] and girls [Coef: 0.02; p < 0.01] from Bihar had a higher likelihood to be aware about HIV in reference to those from Uttar Pradesh.

Discussion

This is the first study of its kind to address awareness of HIV among adolescents utilizing longitudinal data in two indian states. Our study demonstrated that the awareness of HIV has increased over the period; however, it was more prominent among adolescent boys than in adolescent girls. Overall, the knowledge on HIV was relatively low, even during wave-II. Almost three-fifths (59.9%) of the boys and two-fifths (39.1%) of the girls were aware of HIV. The prevalence of awareness on HIV among adolescents in this study was lower than almost all of the community-based studies conducted in India10,11,22. A study conducted in slums in Delhi has found almost similar prevalence (40% compared to 39.1% during wave-II in this study) of awareness of HIV among adolescent girls31. The difference in prevalence could be attributed to the difference in methodology, study population, and study area.

The study found that the awareness of HIV among adolescent boys has increased from 38.6 percent in wave-I to 59.9 percent in wave-II; similarly, only 30.2 percent of the girls had an awareness of HIV during wave-I, which had increased to 39.1 percent. Several previous studies corroborated the finding and noticed a higher prevalence of awareness on HIV among adolescent boys than in adolescent girls16,32–34. However, a study conducted in a different setting noticed a higher awareness among girls than in boys35. Also, a study in the Indian context failed to notice any statistical differences in HIV knowledge between boys and girls18. Gender seems to be one of the significant determinants of comprehensive knowledge of HIV among adolescents. There is a wide gap in educational attainment among male and female adolescents, which could be attributed to lower awareness of HIV among girls in this study. Higher peer victimization among adolescent boys could be another reason for higher awareness of HIV among them36. Also, cultural double standards placed on males and females that encourage males to discuss HIV/AIDS and related sexual matters more openly and discourage or even restrict females from discussing sexual-related issues could be another pertinent factor of higher awareness among male adolescents33. Behavioural interventions among girls could be an effective way to improving knowledge HIV related information, as seen in previous study37. Furthermore, strengthening school-community accountability for girls' education would augment school retention among girls and deliver HIV awareness to girls38.

Similar to other studies2,10,17,18,39–41, age was another significant determinant observed in this study. Increasing age could be attributed to higher education which could explain better awareness with increasing age. As in other studies18,39,41–46, education was noted as a significant driver of awareness of HIV among adolescents in this study. Higher education might be associated with increased probability of mass media and internet exposure leading to higher awareness of HIV among adolescents. A study noted that school is one of the important factors in raising the awareness of HIV among adolescents, which could be linked to higher awareness among those with higher education47,48. Also, schooling provides adolescents an opportunity to improve their social capital, leading to increased awareness of HIV.

Following previous studies18,40,46, the current study also outlines a higher awareness among urban adolescents than their rural counterparts. One plausible reason for lower awareness among adolescents in rural areas could be limited access to HIV prevention information16. Moreover, rural–urban differences in awareness of HIV could also be due to differences in schooling, exposure to mass media, and wealth44,45. The household's wealth status was also noted as a significant predictor of awareness of HIV among adolescents. Corroborating with previous findings16,33,42,49, this study reported a higher awareness among adolescents from richer households than their counterparts from poor households. This could be because wealthier families can afford mass-media items like televisions and radios for their children, which, in turn, improves awareness of HIV among adolescents33.

Exposure to mass media and internet access were also significant predictors of higher awareness of HIV among adolescents. This finding agrees with several previous research, and almost all the research found a positive relationship between mass-media exposure and awareness of HIV among adolescents10. Mass media addresses such topics more openly and in a way that could attract adolescents’ attention is the plausible reason for higher awareness of HIV among those having access to mass media and the internet33. Improving mass media and internet usage, specifically among rural and uneducated masses, would bring required changes. Integrating sexual education into school curricula would be an important means of imparting awareness on HIV among adolescents; however, this is debatable as to which standard to include the required sexual education in the Indian schooling system. Glick (2009) thinks that the syllabus on sexual education might be included during secondary schooling44. Another study in the Indian context confirms the need for sex education for adolescents50,51.

Limitations and strengths of the study

The study has several limitations. At first, the awareness of HIV was measured with one question only. Given that no study has examined awareness of HIV among adolescents using longitudinal data, this limitation is not a concern. Second, the study findings cannot be generalized to the whole Indian population as the study was conducted in only two states of India. However, the two states selected in this study (Uttar Pradesh and Bihar) constitute almost one-fourth of India’s total population. Thirdly, the estimates were provided separately for boys and girls and could not be presented combined. However, the data is designed to provide estimates separately for girls and boys. The data had information on unmarried boys and girls and married girls; however, data did not collect information on married boys. Fourthly, the study estimates might have been affected by the recall bias. Since HIV is a sensitive topic, the possibility of respondents modifying their responses could not be ruled out. Hawthorne effect, respondents, modifying aspect of their behaviour in response, has a role to play in HIV related study52. Despite several limitations, the study has specific strengths too. This is the first study examining awareness of HIV among adolescent boys and girls utilizing longitudinal data. The study was conducted with a large sample size as several previous studies were conducted in a community setting with a minimal sample size10,12,18,20,53.

Conclusion

The study noted a higher awareness among adolescent boys than in adolescent girls. Specific predictors of high awareness were also noted in the study, including; higher age, higher education, exposure to mass media, internet use, household wealth, and urban residence. Based on the study findings, this study has specific suggestions to improve awareness of HIV among adolescents. There is a need to intensify efforts in ensuring that information regarding HIV should reach vulnerable sub-groups as outlined in this study. It is important to mobilize the available resources to target the less educated and poor adolescents, focusing on rural adolescents. Investment in education will help, but it would be a long-term solution; therefore, public information campaigns could be more useful in the short term.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the study: S.S. and P.K.; analysis and/or interpretation of data: P.K. and S.S.; drafting the manuscript: S.C., and R.P.; reading and approving the manuscript: S.S., P.K., S.C. and R.P.

Funding

This paper was written using data collected as part of Population Council’s UDAYA study, which is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. No additional funds were received for the preparation of the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO. HIV/AIDS. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids (2020).

- 2.Singh A, Jain S. Awareness of HIV/AIDS among school adolescents in Banaskantha district of Gujarat. Health Popul.: Perspect. Issues. 2009;32:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO & UNICEF. adolescents Health: The Missing Population in Universal Health Coverage. 1–31 https://www.google.com/search?q=adolescents+population+WHO+report&rlz=1C1CHBF_enIN904IN904&oq=adolescents+population+WHO+report&aqs=chrome..69i57.7888j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 (2018).

- 4.Chauhan S, Arokiasamy P. India’s demographic dividend: state-wise perspective. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 2018;20:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiwari AK, Singh BP, Patel V. Population projection of India: an application of dynamic demographic projection model. JCR. 2020;7:547–555. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troop-Gordon W. Peer victimization in adolescence: the nature, progression, and consequences of being bullied within a developmental context. J. Adolesc. 2017;55:116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dermody SS, Friedman M, Chisolm DJ, Burton CM, Marshal MP. Elevated risky sexual behaviors among sexual minority girls: indirect risk pathways through peer victimization and heavy drinking. J. Interpers. Violence. 2020;35:2236–2253. doi: 10.1177/0886260517701450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee RLT, Loke AY, Hung TTM, Sobel H. A systematic review on identifying risk factors associated with early sexual debut and coerced sex among adolescents and young people in communities. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018;27:478–501. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurram, S. & Bollampalli, B. A study on awareness of human immunodeficiency virus among adolescent girls in urban and rural field practice areas of Osmania Medical College, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. (2020).

- 10.Jain R, Anand P, Dhyani A, Bansal D. Knowledge and awareness regarding menstruation and HIV/AIDS among schoolgoing adolescent girls. J. Fam. Med. Prim Care. 2017;6:47–51. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.214970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawale S, Sharma V, Thaware P, Mohankar A. A study to assess awareness about HIV/AIDS among rural population of central India. Int. J. Commun. Med. Public Health. 2017;5:373–376. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lal P, Nath A, Badhan S, Ingle GK. A study of awareness about HIV/AIDS among senior secondary school Children of Delhi. Indian J. Commun. Med. 2008;33:190–192. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.42063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bago J-L, Lompo ML. Exploring the linkage between exposure to mass media and HIV awareness among adolescents in Uganda. Sex. Reprod. Healthcare. 2019;21:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCombie, S., Hornik, R. C. & Anarfi, J. K. Effects of a mass media campaign to prevent AIDS among young people in Ghana. Public Health Commun. 163–178 (Routledge, 2002). 10.4324/9781410603029-17.

- 15.Sano Y, et al. Exploring the linkage between exposure to mass media and HIV testing among married women and men in Ghana. AIDS Care. 2016;28:684–688. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1131970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oginni AB, Adebajo SB, Ahonsi BA. Trends and determinants of comprehensive knowledge of HIV among adolescents and young adults in Nigeria: 2003–2013. Afr. J. Reprod. Health. 2017;21:26–34. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman MM, Kabir M, Shahidullah M. Adolescent knowledge and awareness about AIDS/HIV and factors affecting them in Bangladesh. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2009;21:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yadav SB, Makwana NR, Vadera BN, Dhaduk KM, Gandha KM. Awareness of HIV/AIDS among rural youth in India: a community based cross-sectional study. J. Infect. Dev. Countries. 2011;5:711–716. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alhasawi A, et al. Assessing HIV/AIDS knowledge, awareness, and attitudes among senior high school students in Kuwait. MPP. 2019;28:470–476. doi: 10.1159/000500307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakrovarty A, et al. A study of awareness on HIV/AIDS among higher secondary school students in Central Kolkata. Indian J. Commun. Med. 2007;32:228. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katoch DKS, Kumar A. HIV/AIDS awareness among students of tribal and non-tribal area of Himachal Pradesh. J. Educ. 2017;5:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shinde M, Trivedi A, Shinde A, Mishra S. A study of awareness regarding HIV/AIDS among secondary school students. Int. J. Commun. Med. Public Health. 2016 doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20161611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Council, P. UDAYA, adolescent survey, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, 2015–16. Harvard Dataverse 10.7910/DVN/RRXQNT (2018).

- 24.Kumar P, Dhillon P. Household- and community-level determinants of low-risk Caesarean deliveries among women in India. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2021;53:55–70. doi: 10.1017/S0021932020000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel SK, Santhya KG, Haberland N. What shapes gender attitudes among adolescent girls and boys? Evidence from the UDAYA Longitudinal Study in India. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0248766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan C, Wang L, Wei L. Comparing two tests for two rates. Am. Stat. 2017;71:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim TK. T test as a parametric statistic. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2015;68:540–546. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2015.68.6.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell A, Fairbrother M, Jones K. Fixed and random effects models: making an informed choice. Qual. Quant. 2019;53:1051–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarrett R, Farewell V, Herzberg A. Random effects models for complex designs. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2020;29:3695–3706. doi: 10.1177/0962280220938418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neuhaus JM, Kalbfleisch JD. Between- and within-cluster covariate effects in the analysis of clustered data. Biometrics. 1998;54:638–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaur G. Factors influencing HIV awareness amongst adolescent women: a study of slums in Delhi. Demogr. India. 2018;47:100–111. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alene GD, Wheeler JG, Grosskurth H. Adolescent reproductive health and awareness of HIV among rural high school students, North Western Ethiopia. AIDS Care. 2004;16:57–68. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001633976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oljira L, Berhane Y, Worku A. Assessment of comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge level among in-school adolescents in eastern Ethiopia. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013;16:17349. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.17349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samkange-Zeeb FN, Spallek L, Zeeb H. Awareness and knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among school-going adolescents in Europe: a systematic review of published literature. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:727. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laguna, E. P. Knowledge of HIV/AIDS and unsafe sex practices among Filipino youth. in 15 (PAA, 2004).

- 36.Teitelman AM, et al. Partner violence, power, and gender differences in South African adolescents’ HIV/sexually transmitted infections risk behaviors. Health Psychol. 2016;35:751–760. doi: 10.1037/hea0000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oberth G, et al. Effectiveness of the Sista2Sista programme in improving HIV and other sexual and reproductive health outcomes among vulnerable adolescent girls and young women in Zimbabwe. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2021;20:158–164. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2021.1918733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeSoto, J. et al. Using school-based early warning systems as a social and behavioral approach for HIV prevention among adolescent girls. Preventing HIV Among Young People in Southern and Eastern Africa 280 (2020).

- 39.Ochako R, Ulwodi D, Njagi P, Kimetu S, Onyango A. Trends and determinants of Comprehensive HIV and AIDS knowledge among urban young women in Kenya. AIDS Res. Ther. 2011;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peltzer K, Supa P. HIV/AIDS knowledge and sexual behavior among junior secondary school students in South Africa. J. Soc. Sci. 2005;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shweta C, Mundkur S, Chaitanya V. Knowledge and beliefs about HIV/AIDS among adolescents. WebMed Cent. 2011;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anwar M, Sulaiman SAS, Ahmadi K, Khan TM. Awareness of school students on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and their sexual behavior: a cross-sectional study conducted in Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cicciò L, Sera D. Assessing the knowledge and behavior towards HIV/AIDS among youth in Northern Uganda: a cross-sectional survey. Giornale Italiano di Medicina Tropicale. 2010;15:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glick P, Randriamamonjy J, Sahn DE. Determinants of HIV knowledge and condom use among women in madagascar: an analysis using matched household and community data. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2009;21:147–179. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahman M. Determinants of knowledge and awareness about AIDS: Urban-rural differentials in Bangladesh. JPHE. 2009;1:014–021. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siziya S, Muula AS, Rudatsikira E. HIV and AIDS-related knowledge among women in Iraq. BMC. Res. Notes. 2008;1:123. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-1-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao X, et al. Effectiveness of school-based education on HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitude, and behavior among secondary school students in Wuhan, China. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kotecha PV, et al. Reproductive health awareness among urban school going adolescents in Vadodara city. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2012;54:344–348. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.104821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dimbuene TZ, Defo KB. Fostering accurate HIV/AIDS knowledge among unmarried youths in Cameroon: do family environment and peers matter? BMC Public Health. 2011;11:348. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar R, et al. Knowledge attitude and perception of sex education among school going adolescents in Ambala District, Haryana, India: a cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017;11:LC01–LC04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/19290.9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tripathi N, Sekher TV. Youth in India ready for sex education? Emerging evidence from national surveys. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenberg M, et al. Evidence for sample selection effect and Hawthorne effect in behavioural HIV prevention trial among young women in a rural South African community. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019167. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta P, Anjum F, Bhardwaj P, Srivastav J, Zaidi ZH. Knowledge about HIV/AIDS among secondary school students. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2013;5:119–123. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.107531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]