Abstract

It remains unclear if previously reported structural abnormalities in children with ADHD are present in adulthood regardless of clinical outcome. In this study, we examined the extent to which focal—rather than diffuse—abnormalities in fiber collinearity of 18 major white matter tracts could distinguish 126 adults with rigorously diagnosed childhood ADHD (ADHD; mean age [SD] = 34.3 [3.6] years; F/M = 12/114) from 58 adults without ADHD histories (non-ADHD; mean age [SD] = 33.9 [4.1] years; F/M = 5/53) and if any of these abnormalities were greater for those with persisting ADHD symptomatology. To this end, a tract profile approach was used. After accounting for age, sex, handedness, and comorbidities, a MANCOVA revealed a main effect of group (ADHD < non-ADHD; F[18,155] = 2.1; p = 0.007) on fractional anisotropy (FA, a measure of fiber collinearity and/or integrity), in focal portions of white matter tracts involved in visuospatial processing and memory (i.e., anterior portion of the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus, and middle portion of the left and right cingulum angular bundle). Only abnormalities in the anterior portion of the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus distinguished probands with persisting versus desisting ADHD symptomatology, suggesting that abnormalities in the cingulum angular bundle might reflect “scarring” effects of childhood ADHD. To our knowledge, this is the first study using a tract profile approach to identify focal or widespread structural abnormalities in adults with ADHD rigorously diagnosed in childhood.

Introduction

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder of childhood with an estimated prevalence of 6.5% worldwide [1]. ADHD is defined by inattention and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity that is inappropriate to the developmental stage and interferes with the individual’s functioning [2]. The hyperactive/impulsive symptoms tend to decline over time while inattentive symptoms often persist, even in those who in adulthood remit from full ADHD diagnosis [3]. Persistence of ADHD symptoms and impairment into adulthood is common with prior research reporting a range of 30–75% [4–6]. Variations in these ADHD persistence estimates are partly due to how and by whom the symptoms were assessed. Research has shown the importance of including informant report to describe ADHD symptom persistence in adults followed since childhood given underreporting by individuals with ADHD [5, 7].

The neurobiological mechanisms underpinning ADHD and the neurobiological signature of the illness in adults with persisting ADHD symptomatology, and in those whose symptoms decline over time, have been a focus of research over the past 20 years. From this research has emerged a theory of neurodevelopmental (frontoparietal cortical) delay in ADHD [8–16]. Although children with persisting ADHD symptomatology into their early 20s exhibited thinner frontoparietal cortices than typically developing individuals, children whose symptoms remitted had less cortical thinning over time and converged with the typically developing group. Another study found [11] that improvements in hyperactive/impulsive symptoms were associated with increased functional connectivity within the executive control network in adolescence [16].

Yet, the role of structural (white matter) connectivity in ADHD remains controversial [17–20]. Only four studies have been conducted in adults with ADHD [21–24]. Three showed similar abnormalities in the sagittal stratum [21, 24] and in the posterior portion of the corpus callosum [22]. Only one of these studies was prospective from childhood diagnosis and white matter abnormalities were independent of ADHD symptom persistence [25], suggesting that these abnormalities might persist in adulthood, regardless of ADHD symptom persistence. However, some of these studies included relatively small samples (n = 51, 37, 29, respectively), and most of them used sequences with low angular resolution, out-of-date correcting procedures [17], and/or voxel-based or tract-based spatial statistics approaches, which have been criticized for having limited anatomical relevance for structural connectivity [26, 27]. Tractographic algorithms are a promising alternative as they provide fiber reconstruction and accurate estimates of diffusion imaging properties in tracts of interest. To our knowledge, only one study including 32 adults with persisting and 43 adults with desisting ADHD symptoms (and 74 unaffected adults) used tractography to examine if abnormal collinearity in major white matter tracts could help explain ADHD outcome in adulthood. In this study, Shaw et al. showed that lower collinearity of the fibers in white matter tracts implicated in visuospatial attention and emotion regulation processing was associated with persisting ADHD symptoms in adulthood [25]. More recently, several diffusion imaging toolboxes [28–31] have been including tract-profiling methods to characterize microstructural properties along the entire tract rather than simply averaging these measures across the tract. Tract profiles have the advantage of more precisely quantifying the degree of abnormality (focal vs. widespread) in a particular tract.

In the present study, we employed state-of-the-art diffusion imaging protocols in a large sample of adults with a well-documented childhood diagnosis of ADHD to (1) identify neural correlates of a childhood ADHD diagnosis in adulthood using tractographic algorithms, and (2) examine to what extent tract abnormalities are associated with ADHD symptom outcomes (desistence vs. persistence) in adulthood. Specifically, using a high angular multishell diffusion imaging sequence, global probabilistic tractography and tract profiles, we hypothesized that adults with childhood ADHD would show low collinearity of the fibers in white matter tracts previously reported to be abnormal in ADHD (white matter tracts implicated in visuospatial attention, cognitive control, and emotion regulation). Based on previous tractographic evidence [25], we also hypothesized that adults with persisting, in comparison to those with desisting, ADHD symptomatology would show greater abnormalities in major white matter tracts implicated in visuospatial attention. To test these hypotheses, we leveraged the Pittsburgh ADHD Longitudinal Study (PALS), which consists of a large sample of children rigorously diagnosed with ADHD and followed clinically into early adulthood, alongside a demographically similar comparison group of individuals without ADHD histories [32]. The sample provided an important opportunity to test our hypotheses in adults with research quality diagnoses in childhood and in adulthood, including assessment of comorbidities and multi-informant report of ADHD symptom persistence in adulthood.

Methods

Participants

The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Boards and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. One hundred and ninety-six adults (age range = 27–44 years) including 136 adults with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD (ADHD) and 60 adults without ADHD histories (non-ADHD) were recruited from the PALS sample (n = 601; 374 ADHD, 227 non-ADHD) between June 2015 and January 2019 (characteristics of the PALS sample are described in the Supplemental Materials). Current substance dependence was exclusionary for both groups. Recruited participants completed a neuroimaging assessment and various questionnaires; an additional informant (usually mothers) also provided symptom severity ratings for 80.4% of participants. Characteristics of the final sample are reported in Table 1 and exclusion criteria are detailed in the consort diagram (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Between-group differences in demographic and clinical variables.

| Variables | Group | N | Mean [SD] | df | P (two-tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ADHD | 126 | 34.3 [3.6] | 183 | 0.389 |

| non-ADHD | 58 | 33.9 [4.1] | |||

| Sex (F/M) | ADHD | 13/113 | – | 1 | 0.719 |

| non-ADHD | 5/53 | – | |||

| Hand dominance (R/L) | ADHD | 105/21 | – | 1 | 0. 420 |

| non-ADHD | 51/7 | – | |||

| Scanner (Trio/prisma)a | ADHD | 99/27 | – | 1 | 0.002 |

| non-ADHD | 33/25 | – | |||

| Education (lower/higherb) | ADHD | 89/37 | – | 1 | <0.001 |

| non-ADHD | 18/40 | – | |||

| IQ estimate (WASI-II) | ADHD | 126 | 100.1 [14.9] | 182 | <0.001 |

| non-ADHD | 58 | 110.2 [13.2] | |||

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | ADHD | 124 | 0.6 [0.5] | 177 | 0.016 |

| non-ADHD | 55 | 0.4 [0.4] | |||

| Anxiety symptoms (STAI-STATE) | ADHD | 125 | 33.1 [9.3] | 181 | 0.025 |

| non-ADHD | 58 | 29.9 [8.2] | |||

| Anxiety symptoms (STAI-TRAIT) | ADHD | 126 | 39.7 [11.2] | 182 | 0.001 |

| non-ADHD | 58 | 34.0 [9.9] | |||

| Lifetime mood/anxiety disorders (No/yes) | ADHD | 67/59 | – | 1 | 0.177 |

| non-ADHD | 37/21 | – | |||

| Lifetime marijuana use disorders (No/mild/moderate/severe) | ADHD | 65/10/20/27 | – | 3 | 0.641 |

| non-ADHD | 31/7/11/9 | – | |||

| Lifetime alcohol use disorders (No/mild/moderate/severe) | ADHD | 48/23/16/39 | – | 3 | 0.146 |

| non-ADHD | 15/16/12/15 | – | |||

| Stimulants at scan (No/yes) | ADHD | 4/122 | – | – | |

| non-ADHD | – | – | – |

Bold values indicate statistical significance p < 0.05.

WASI-II Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence, BAARS-IV Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV, CES-D Center for epidemiologic studies—depression, STAI state-trait anxiety inventory, UPPS-P PPS impulsive behavior scale.

A ComBat approach was used to make the scanner effect negligible in all analyses.

Education levels are higher education (i.e., college diploma/Bachelor’s degree, graduate or professional degree) and lower education (i.e., partial high school, high school diploma or general equivalency degree, unfinished college, technical school or associates degree).

Clinical assessment

ADHD symptom persistence was assessed with the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV (18-item; item responses 0–3) [33]. Following published procedures [34], symptoms were counted as present if endorsed as 2 or 3 by self- or informant-report. Consistent with DSM-5 [2], if five or more symptoms of inattention or impulsivity-hyperactivity were present, symptom persistence was coded as present (26% of the participating ADHD group). Continuous symptom severity scores for inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity were also calculated as the mean of symptom ratings for each dimension, taking for each item the higher response endorsed across self- and informant-report.

Other lifetime Axis-I diagnoses were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR, Nonpatient Edition. To assess association with current depression and anxiety symptoms, scores were used from the self-reported Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression (CES-D; 20-item) [35–37] and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; 20-item) [38], respectively.

Estimates of subjects’ general cognitive ability were generated from the Vocabulary and Matrix reasoning subtests of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence [39, 40].

Data analysis

Neuroimaging

Images were acquired on a 3T Siemens Magnetom Prisma (27 ADHD and 25 non-ADHD) and a 3T Siemens Magnetom Trio (99 ADHD and 33 non-ADHD) at the Magnetic Resonance Research Center, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System, USA. Neuroimaging acquisition, preprocessing and harmonization of the neuroimaging data across the scanners are described in the Supplementary Materials and Supplementary Table 1.

Mean translation and rotation estimates for each subject were estimated to test if there was a main effect of movement on neuroimaging measures of interest. Eighteen major white matter tracts (left/right corticospinal spinal tract, anterior thalamic radiation, cingulum bundle, cingulum angular bundle, superior longitudinal fasciculus, arcuate fasciculus, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, and the two major interhemispheric bundles of the corpus callosum: forceps minor and forceps major) were reconstructed using a triple-tensor model of global probabilistic tractography [41] in TRActs Constrained by UnderLying Anatomy [31]. After quality control (see Supplementary Materials), fractional anisotropy (FA, a measure of fiber collinearity and/or integrity) maps were derived from the b = 1000 shell using dtifit. Finally, overall mean FA and nodal FA values were extracted to depict the collinearity of the fibers across (mean) and along (tract profile) the entire tract, for each tract. As noted above, tract profiles (100 nodes) were used to quantify whether abnormalities in tracts of interest were focal (e.g., in proximity of the cortex or more central to the core of the tract) or widespread.

Statistical approach

Demographic, clinical, and diffusion imaging measures were imported into SPSS(v25). Given the known effect of age [42–44], sex [45], and handedness [46] on white matter, these variables were covariates in all main analyses. Lifetime mood and/or anxiety, marijuana use, and alcohol use disorders comorbidity, prevalent comorbidities in this sample, were included as covariates in all main analyses.

To test our main hypotheses, the following analytic approach was adopted. A false discovery rate (FDR; R package) [47, 48] of p < 0.05 was used to account for multiple comparisons in each analysis.

Level-1 analyses

Using multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVA), we examined whether there was a main effect of group (ADHD/non-ADHD) for the mean FA of all 18 white matter tracts. Follow-up analyses included 18 univariate ANCOVAs to identify which tract differed between the groups and nodal FA analyses (tract profile; n = 100 nodes) to identify which portion of the tract accounted for those differences. Here, the cluster-forming threshold was set to ten contiguous nodes and FDR p < 0.05. Mean FA in node clusters was derived and used in subsequent analyses.

Level-2 analyses: ADHD persistence

Using a MANCOVA, we examined whether there was a main effect of group (ADHD-persisters, ADHD-desisters, non-ADHD) for the mean FA of node cluster(s) identified in the level-1 analyses. Follow-up analyses included univariate ANCOVA(s) to identify which cluster differed between the three groups.

In ADHD-persisters and ADHD-desisters only, parallel analyses examined the relations between mean FA in node clusters and continuous dimensions of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms.

Exploratory analyses

To explore whether the severity of mood and anxiety symptoms at the time of scan related to FA, we computed Pearson correlations between current symptom severity of depression (CES-D) and anxiety (STAI) and mean FA of node clusters.

To aid interpretation of main FA findings, mean axial and radial diffusivity were extracted in node clusters identified in level-2 analyses.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

There were no differences in age, sex, race, ethnicity, and left-right handedness ratio between the ADHD and non-ADHD groups. As expected, adults in the ADHD group had fewer years of education and lower IQ estimates. They also had higher depression symptom scores and state and trait anxiety scores (Table 1). For demographic and clinical characteristics in ADHD-persisters and ADHD-desisters, see Supplementary Table 2.

Neuroimaging

There was no effect of movement in our neuroimaging measures of interest (Supplementary Table 3A).

Given the existing difference in education and IQ estimates between ADHD and non-ADHD, before testing our main hypotheses, we determined if there was an overall effect of these variables on FA (i.e., mean FA of 18 white matter tract). Findings were not significant (see Supplemental Table 3B–C) and therefore these variables were not used as covariates in the analyses.

Level-1 analyses

After accounting for the effects of age, sex, left-right handedness ratio, lifetime comorbidity (mood/anxiety and substance use disorders) there was a significant main effect of group (Two levels: ADHD, non-ADHD) (Wilks’ lambda = 0.802; F[18,155] = 2.1; p = 0.007) on FA across all 18 tracts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of level-1 analyses comparing ADHD and non-ADHD groups on FA in 18 white matter tracts.

| Multivariate tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect | Wilks’ lambda | F [18,155] | P |

| Group (ADHD, non-ADHD)a | 2.1 | 0.007 | 2.1 |

| Age (YY)b | 3.0 | <0.001 | 3.0 |

| Sex (F/M) | 1.0 | 0.448 | 1.0 |

| Handedness (L/R) | 1.1 | 0.337 | 1.1 |

| Lifetime mood/anxiety disorders (YES/NO) | 1.2 | 0.288 | 1.2 |

| Lifetime marijuana use disorder (No/mild/moderate/severe) | 0.7 | 0.926 | 0.7 |

| Lifetime alcohol use disorder (No/mild/moderate/severe) | 0.8 | 0.773 | 0.8 |

| Tests of between-subjects effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect | Tract | F [1.183] | Sig. | FDR q |

| Group (ADHD, non-ADHD)a | Forceps MINOR | 5.4 | 0.022 | 0.079 |

| Forceps major | 1.0 | 0.320 | 0.592 | |

| Right anterior thalamic radiation | 0.0 | 0.829 | 0.933 | |

| Left anterior thalamic radiation | 0.0 | 0.975 | 0.975 | |

| Right corticospinal tract | 1.2 | 0.273 | 0.592 | |

| Left corticospinal tract | 0.8 | 0.372 | 0.597 | |

| Right CAB | 7.6 | 0.007 | 0.041 | |

| Left CAB | 7.8 | 0.006 | 0.041 | |

| Right cingulum bundle | 1.0 | 0.329 | 0.592 | |

| Left cingulum bundle | 1.2 | 0.275 | 0.592 | |

| Right ILF | 8.4 | 0.004 | 0.041 | |

| Left ILF | 7.0 | 0.009 | 0.041 | |

| Right superior longitudinal fasciculus | 0.7 | 0.398 | 0.597 | |

| Left superior longitudinal fasciculus | 0.4 | 0.527 | 0.678 | |

| Right uncinate fasciculus | 0.5 | 0.468 | 0.648 | |

| Left uncinate fasciculus | 0.1 | 0.814 | 0.933 | |

Levene’s test of equality of error variance was p > 0.05 for mean FA of all 18 major white matter tracts included in the MANCOVA.

Age, sex, handedness, and lifetime comorbidities were covariates in all analyses.

P and q < 0.05 in bold; trend-level significance in italics.

126 adults in the ADHD group and 58 adults with the non-ADHD group were included in level-1 analyses.

There was a main effect of age (inverse relationship) on FA in these clusters.

Follow-up analyses revealed that group differences were in the inferior longitudinal fasciculus (left: F[1,183] = 7.0; p = 0.009; right: F[1,183] = 8.4; p = 0.004) and cingulum angular bundle (left: F[1,183] = 7.8; p = 0.006; right: F[1,183] = 7.6; p = 0.007) (Table 2).

Tract profile analyses in these four tracts showed that, compared to adults in the non-ADHD group, the adults in the ADHD group had lower FA in the anterior portion of the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ADHD < non-ADHD: k = 16 consecutive nodes; F[1,184] = 9.1; p = 0.003; FDR-corrected p = 0.038), in the middle portion of the left cingulum angular bundle (ADHD < non-ADHD: k = 19 consecutive nodes; F[1,184] = 7.2; p = 0.003; FDR-corrected p = 0.022), and in the middle portion of the right cingulum angular bundle (ADHD < non-ADHD: k = 24 consecutive nodes; F[1,184] = 8.5; p = 0.005; FDR-corrected p = 0.038). There was also a significant group difference in a node cluster in the posterior portion of the right inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ADHD < non-ADHD: k = 12 consecutive nodes; F[1,184] = 3.9; p = 0.022), but this finding did not survive correction for multiple comparisons.

Level-2 analyses. ADHD persistence

After accounting for the effects of age, sex, left-right handedness ratio, and lifetime comorbidities, there was a significant main effect of group (Three levels: ADHD-persisters, ADHD-desisters, non-ADHD) (Wilks’ lambda = 0.8; F[6,348] = 7.6; p < 0.001) on the three node clusters identified in the level-1 analyses (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of level-2 analyses comparing adults in the ADHD-persisters, ADHD-desisters and non-ADHD groups on FA in three node clusters identified in level-1 analyses.

| Multivariate tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect | Wilks’ lambda | F [6,348] | p |

| Group (ADHD-persisters, ADHD-desisters, non-ADHD) | 0.853 | 4.7 | <0.001 |

| Age (YY)a | 0.911 | 5.5 | 0.001 |

| Sex (F/M) | 0.962 | 2.3 | 0.084 |

| Handedness (L/R) | 0.983 | 0.9 | 0.418 |

| Lifetime mood/anxiety disorders | 0.978 | 1.3 | 0.282 |

| Lifetime marijuana use disorder | 0.973 | 0.5 | 0.861 |

| Lifetime alcohol use disorder | 0.953 | 0.9 | 0.516 |

| Tests of between-subjects effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect | Node cluster | F [2,184] | p | FDR q |

| Group (ADHD-persisters, ADHD-desisters, non-ADHD) | Mean FA—[Left inferior longitudinal fasciculus] | 8.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Mean FA—[Left cingulum angular bundle] | 5.3 | 0.006 | 0.008 | |

| Mean FA—[Right cingulum angular bundle] | 5.0 | 0.008 | 0.008 | |

| Pairwise comparisons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node cluster | Contrast | Mean difference | p | FDR q |

| Mean FA—[Left inferior longitudinal fasciculus] | ADHD-persisters vs. ADHD-desisters | −0.017 | 0.013 | 0.020 |

| ADHD-persisters vs. non-ADHD | −0.030 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| ADHD-desisters vs. non-ADHD | −0.013 | 0.021 | 0.027 | |

| Mean FA—[Left cingulum angular bundle] | ADHD-persisters ADHD-desisters | −0.002 | 0.844 | 0.844 |

| ADHD-persisters vs. non-ADHD | −0.034 | 0.012 | 0.020 | |

| ADHD-desisters vs. non-ADHD | −0.032 | 0.003 | 0.014 | |

| Mean FA—[Right cingulum angular bundle] | ADHD-persisters vs. ADHD-desisters | −0.004 | 0.727 | 0.818 |

| ADHD-persisters vs. non-ADHD | −0.031 | 0.011 | 0.020 | |

| ADHD-desisters vs. non-ADHD | −0.027 | 0.005 | 0.015 | |

Age, sex, handedness, and lifetime comorbidities were covariates in all analyses.

p and q < 0.05 in bold; trend-level significance in italics.

There was a main effect of age (inverse relationship) on FA in these clusters.

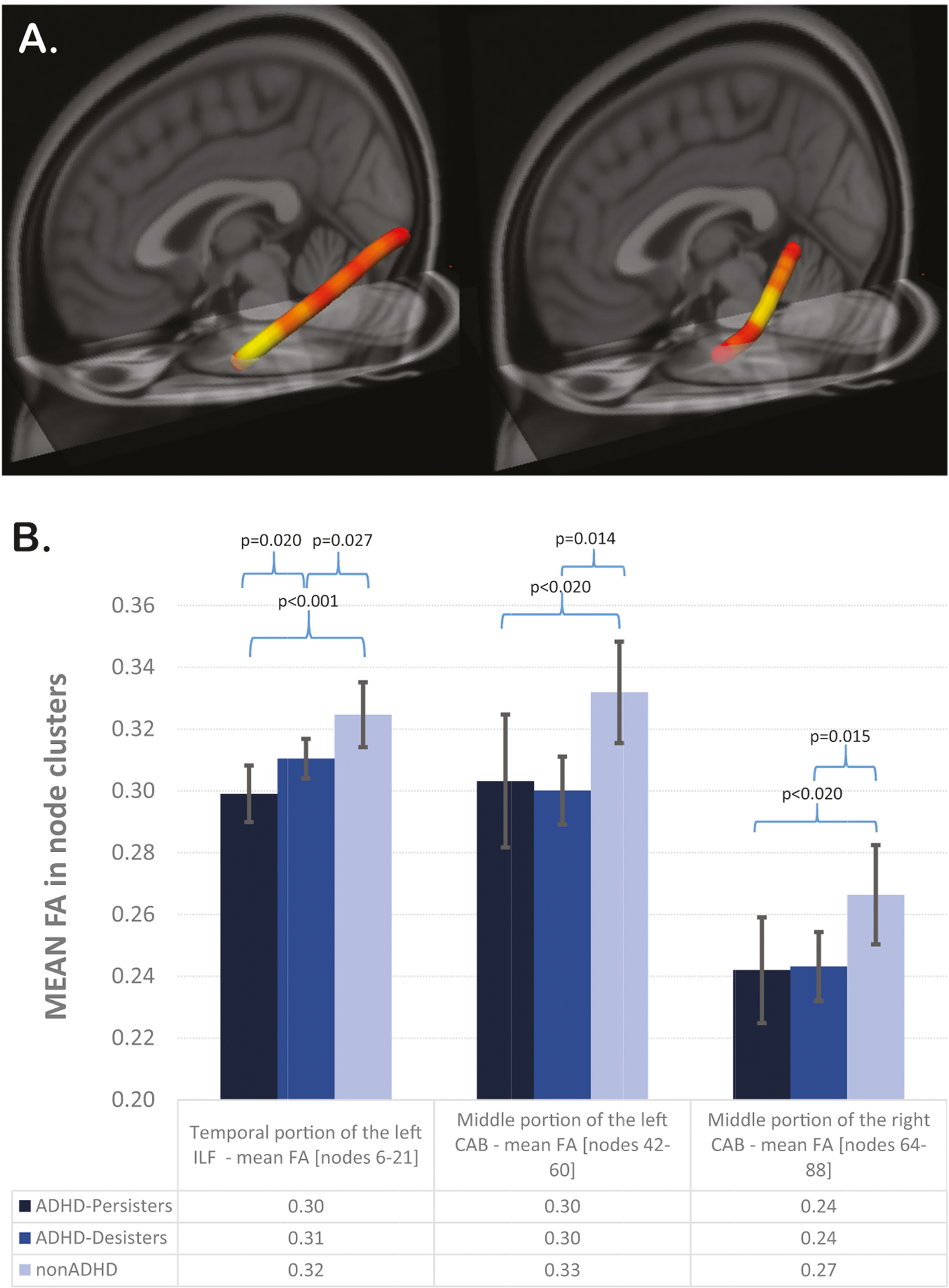

Three (one for each node cluster) follow-up univariate analyses revealed that in the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus cluster, both ADHD-persisters and ADHD-desisters showed lower FA than adults in the non-ADHD group (ADHD-persisters < non-ADHD: p < 0.001; ADHD-desisters < non-ADHD: p = 0.021; all FDR corrected). Notably, in the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus cluster, ADHD-persisters also showed lower FA than ADHD-desisters (p = 0.013; FDR corrected). In the left and right cingulum angular bundle cluster, both ADHD-persisters and ADHD-desisters showed lower FA than adults in the non-ADHD group (left: ADHD-persisters < non-ADHD: p = 0.012; ADHD-desisters < non-ADHD: p = 0.003; right: ADHD-persisters < non-ADHD: p = 0.011; ADHD-desisters < non-ADHD: p = 0.005; all FDR corrected). However, ADHD-persisters and ADHD-desisters did not differ significantly in these clusters (p > 0.05), (Table 3; Fig. 1A, B).

Fig. 1.

A–B Legend. A 3D visualization of the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus and in left cingulum angular bundle showing lower FA in ADHD versus non-ADHD. Tractographic analyses were performed in native space. One hundred segments for each tract were used to define the tract profiles. To represent between-group differences (red-yellow color bar depicts significance levels of p < 0.05), main findings are displayed in MNI space. B Error-bar plots represent the mean FA in the three clusters identified in level-1 analyses in adults in the ADHD-persisters, ADHD-desisters and non-ADHD groups. Confidence interval of 95% is shown. ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, MNI Montreal Neurological Institute, FA fractional anisotropy, FMINOR forceps minor, ILF inferior longitudinal fasciculus, CAB cingulum angular bundle.

We explored the possibility of missed persistence group differences in major white matter tracts that were not significantly different in the level-1 analyses. Using a three-way (ADHD-persisters, ADHD-desisters, non-ADHD) MANCOVA, we examined if there was a main effect of ADHD persistence across all 18 major white matter tracts. This analysis yielded similar results (Supplementary Table 4).

Analyses examining the relationship between mean FA in node clusters and continuous dimensions of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms across the ADHD-persisters and ADHD-desisters revealed that higher levels of inattention symptoms at scan were associated with lower FA in the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus cluster (Wilks’ lambda = 0.9; F[6,348] = 3,1; p = 0.029; Supplementary Table 5A, B).

Exploratory analyses

There were no significant associations between the CES-D, STAI-State, or STAI-Trait scores and mean FA in the three node clusters identified in the level-1 analyses (Supplementary Table 6).

FA in the left and right cingulum angular clusters was associated with a significant decreased axial diffusivity (p = 0.006; p = 0.002, respectively); FA in the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus cluster was associated with increased radial diffusivity (p = 0.006) (Supplementary Table 7A, B).

Discussion

In the present study, we used for the first time a combination of global probabilistic tractography and tract profiles to (1) assess structural abnormalities in major white matter tracks in a sample of adults rigorously diagnosed with ADHD in childhood in comparison to demographically similar adults without ADHD and (2) further determine the role of ADHD symptom outcomes (desistence vs. persistence) on these tract abnormalities.

In line with our main hypothesis and confirming previous evidence [21–24], adults with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD, when compared with adults without ADHD histories, showed structural abnormalities in white matter tracts primarily involved in visuospatial attention (i.e., lower collinearity/integrity of the fibers in the inferior longitudinal fasciculus, with lower FA in the left relative to the right hemisphere). They also showed lower collinearity/integrity of the fibers in the cingulum angular bundle, bilaterally.

Partially in line with our secondary hypothesis, ADHD-persisters showed greater abnormalities in the anterior portion of the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus, suggesting that abnormalities in this portion of the tract might reflect persistent inattention symptomatology in adulthood. However, we also found that both ADHD-desisters and ADHD-persisters showed abnormalities in the inferior longitudinal fasciculus and cingulum angular bundle when compared to adults without ADHD histories.

Thus, our findings suggest cumulative effects of ADHD onset in childhood and persistent inattention symptoms on white matter collinearity/integrity of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus. The inferior longitudinal fasciculus is part of the external sagittal stratum, connecting the temporal-occipital areas of the brain [49, 50] with the anterior temporal pole [51]. Involved in the processing and modulation of visual cues, the inferior longitudinal fasciculus promotes visually guided behaviors (e.g., reading fluency and comprehension) and visuospatial attention (e.g., object/face recognition and set-shifting attention), which are often impaired in ADHD [52]. Using tract-based spatial statistics, Cortese et al. reported abnormalities in the sagittal stratum (including the inferior longitudinal fasciculus) in 51 adults with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD who had been followed to a mean age of 41 years [24], but ADHD symptom persistence was not associated with these abnormalities. The discrepancy in findings related to symptom persistence could be explained in part by sample size and/or methodological differences (i.e., smaller sample, single-shell diffusion imaging sequence with lower angular resolution and use of a voxel-based MRI approach in the study by Cortese et al., and use of informant report in the present study). Our findings in ADHD symptom persisters vs. desisters suggest that lower collinearity of the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus may reflect active pathophysiologic mechanisms in ADHD, and more specifically of inattention-type symptoms. This finding is partially confirmed by a recent study that used a similar approach in 654 7–29 years olds with and without ADHD [53]. Here, lower FA in the inferior longitudinal fasciculus was associated with higher levels of inattention symptoms; however, this finding did not survive multiple comparison correction. It is possible that differences in age ranges (narrower in our sample), study designs (e.g., harmonization of scanner effect, different use of covariates, different approaches to multiple testing), and diffusion imaging sequences (i.e., high vs. low angular resolution, multi- vs. single-shell and use of isotropic vs. anisotropic voxels) might have increased our ability to detect ADHD-related effects on white matter, despite the relatively smaller sample size.

Adults with ADHD symptom levels below the DSM-5 symptom threshold (ADHD-desisters) also showed lower collinearity of this tract in comparison to the non-ADHD group. If abnormalities in this tract reflect active pathophysiologic mechanisms, why would children with ADHD, who desist later in life, continue to show some level of white matter abnormalities in adulthood? The growing literature documenting impairment experienced by individuals with subthreshold symptomatology, reflecting the dimensional nature of ADHD symptoms, may be partly responsible and explain our findings [4, 12]. However, it is also possible that abnormalities in this tract might reflect some shared variance across desisters and persisters. In our sample, having a childhood diagnosis of ADHD was strongly associated with longstanding academic underachievement (lower education), even in those whose ADHD symptoms desisted in adulthood [54]. Notably, the inferior longitudinal fasciculus is one tract implicated in reading fluency and comprehension [30]. It is important to note that neurodevelopmentally the inferior longitudinal fasciculus matures earlier (and faster) than other associative tracts [43, 55–57] and its rate of maturation (FA in this tract reaches its maximum peak by the age of 11) [56] likely reflects the rapid acquisition of reading fluency/comprehension [30]. The inferior longitudinal fasciculus is plastic [58–60], and intervention strategies targeting language disabilities might not be as effective in ‘reshaping’ this tract if they occur too late (e.g., after age 11). Thus, ADHD symptoms could decline and, depending on when intervention strategies occur, abnormalities in this tract may persist, along with a longstanding academic underachievement in adulthood. The decreased FA was associated with increased radial diffusivity in this tract, which suggests that this finding might reflect a poor organization of the fibers’ architecture—rather than a lower density of the axons—in those with histories of ADHD and/or those with persisting ADHD symptomatology. This further supports the idea that ad hoc intervention strategies might promote a better plasticity (‘reorganization of the wiring’) of this tract. Whether the timing of these interventions plays a role is unknown and warrant continued study in developmental samples.

Our findings also showed that adults with a childhood ADHD onset, when compared to adults without ADHD histories, have lower collinearity in the left and right cingulum angular bundle. The angular bundle of the cingulum connects the posterior hippocampus and the cingulate cortex and represents the retrosplenial cortical pathway that, along with the subcortical diencephalic pathway (fornix and mammillo thalamic tract), constitute the Papez’ circuit [61]. Abnormalities in the cingulum angular bundle have been associated with a decline in episodic [62] and spatial working memory [63–68], especially in the elderly. Relevant to ADHD, animal studies have shown how cingulum angular bundle lesions are associated with delayed acquisition of avoidance responses and increased locomotor activity/exploratory behavior, suggesting that abnormalities in this tract might be associated with symptoms of impulsivity/hyperactivity in ADHD [69]. Relatedly, a recent study found that reduced FA in this tract was associated with higher levels of hyperactivity/impulsivity in a large study of youth and young adults with ADHD (age range of 7–29) [53]. Our findings, however, did not show any association between levels of impulsivity/hyperactivity (or inattention) and degree of cingulum angular bundle collinearity (or with presence/absence of ADHD persistence, Supplementary Table 4). We interpret these findings as suggesting that abnormalities in this tract in adulthood could also reflect the scarring effects of having had a childhood ADHD diagnosis. In fact, these findings raise a fundamental question of whether for a developing brain missing the opportunity of maturing at the proper time translates into brain scarring that persists in adulthood, regardless of desisting symptomatology. The decreased axial diffusivity associated with decreased FA in the left and right side of this tract provides further support; however, longitudinal studies in youth with ADHD are needed to clarify the nature of this finding.

This study has many strengths including a large sample of adults with childhood-onset ADHD who were rigorously diagnosed and followed since childhood, age- and sex-matched adults without ADHD histories, and use of advanced tractographic protocols to quantify alterations in relevant white matter tracts. Another important strength was our effort to minimize the potential effect of other psychiatric disorders in our findings. To this end, in the non-ADHD group we recruited adults with similar rates of lifetime comorbidities (i.e., mood and anxiety disorders, marijuana and alcohol use disorders) to those of adults in the ADHD group. However, certain limitations need to be considered. As is typical in studies of ADHD, the estimated IQ and education levels were significantly lower for the adults in the ADHD vs. non-ADHD group. We chose not to control for these differences, even if a main effect of IQ on MRI measures has been reported [70–72]. Future studies could examine whether intellectual capacity moderates the associations identified in this study. Alcohol and marijuana use disorders are also highly prevalent in ADHD [73], more than in the general population and therefore these were covariates of no-interest in all main analyses; however, we did not find a main effect of these variables on any FA measures of interest. Just a few adults in the ADHD-persisters group were taking stimulant medications at the time of the scan and therefore we could not explore the effect of stimulants on our main findings. Future studies are needed to examine if stimulant medications have a main effect on FA in the inferior longitudinal fasciculus and cingulum angular bundle. Another limitation was that no dummy scan was collected at the beginning of the diffusion imaging sequence for steady-state magnetization.

To our knowledge, this is the first study using a tract profile approach to examine whether focal or widespread structural abnormalities previously reported in children with ADHD persist in adulthood. Our findings indicate that lower collinearity (e.g., a poor organization of the fiber architecture) of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus may underlie persistence of ADHD symptomatology into adulthood; abnormalities (e.g., lower axonal density/diameter) in the parahippocampal section of the cingulum may represent a scarring effect of ADHD, or other precipitants of the disorder in childhood. In sum, findings from this uniquely well-powered study of adults, who were rigorously diagnosed with ADHD in childhood and followed clinically into early adulthood, provide a comprehensive characterization of the white matter structural integrity of childhood-onset ADHD. They also provide critical evidence from which to formulate hypotheses about the neurodevelopmental markers of ADHD pathophysiology that can be tested in future longitudinal studies of children with ADHD as well as those in offspring of parents with ADHD histories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant MH101096 (MPIs: Molina and Ladouceur), by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant AA011873 (PI: Molina), and by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant DA012414 (PI: Pelham). These funding agencies were not involved in the design or conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. We acknowledge Drs. A. Yendiki (TRACULA’s developer) and E. Caruyer (optimization of the gradient schema) for their scientific contributions to this work. We also acknowledge our research participants for their participation into this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01153-7.

Conflict of interest The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:942–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franke B, Michelini G, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Bilbow A, Buitelaar JK, et al. Live fast, die young? A review on the developmental trajectories of ADHD across the lifespan. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28:1059–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hechtman L, Swanson JM, Sibley MH, Stehli A, Owens EB, Mitchell JT, et al. Functional adult outcomes 16 years after childhood diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: MTA results. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:945–e942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Gnagy EM, Waxmonsky JG, Waschbusch DA, et al. When diagnosing ADHD in young adults emphasize informant reports, DSM items, and impairment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:1052–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Zalecki C, Huggins SP, Montenegro-Nevado AJ, Schrodek E, et al. Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into early adulthood: continuing impairment includes elevated risk for suicide attempts and self-injury. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:1041–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:279–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw P, Lerch J, Greenstein D, Sharp W, Clasen L, Evans A, et al. Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and clinical outcome in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:540–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, Blumenthal J, Lerch JP, Greenstein D, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:19649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X-R, Carrey N, Bernier D, MacMaster FP. Cortical thickness in young treatment-naive children with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2012;19:925–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw P, Malek M, Watson B, Greenstein D, de Rossi P, Sharp W. Trajectories of cerebral cortical development in childhood and adolescence and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biederman J, Petty CR, Ball SW, Fried R, Doyle AE, Cohen D, et al. Are cognitive deficits in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder related to the course of the disorder? A prospective controlled follow-up study of grown up boys with persistent and remitting course. Psychiatry Res. 2009;170:177–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung CH, Rijsdijk F, McLoughlin G, Brandeis D, Banaschewski T, Asherson P, et al. Cognitive and neurophysiological markers of ADHD persistence and remission. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208:548–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAuley T, Crosbie J, Charach A, Schachar R. The persistence of cognitive deficits in remitted and unremitted ADHD: a case for the state-independence of response inhibition. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:292–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michelini G, Kitsune GL, Cheung CH, Brandeis D, Banaschewski T, Asherson P, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder remission is linked to better neurophysiological error detection and attention-vigilance processes. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:923–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francx W, Oldehinkel M, Oosterlaan J, Heslenfeld D, Hartman CA, Hoekstra PJ, et al. The executive control network and symptomatic improvement in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Cortex. 2015;73:62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoki Y, Cortese S, Castellanos FX. Research review: diffusion tensor imaging studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: meta-analyses and reflections on head motion. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59:193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Ewijk H, Heslenfeld DJ, Zwiers MP, Buitelaar JK, Oosterlaan J. Diffusion tensor imaging in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1093–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greven CU, Bralten J, Mennes M, O’Dwyer L, van Hulzen KJ, Rommelse N, et al. Developmentally stable whole-brain volume reductions and developmentally sensitive caudate and putamen volume alterations in those with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and their unaffected siblings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:490–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castellanos FX, Lee PP, Sharp W, Jeffries NO, Greenstein DK, Clasen LS, et al. Developmental trajectories of brain volume abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA. 2002;288:1740–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konrad A, Dielentheis TF, Masri DE, Dellani PR, Stoeter P, Vucurevic G, et al. White matter abnormalities and their impact on attentional performance in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262:351–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dramsdahl M, Westerhausen R, Haavik J, Hugdahl K, Plessen KJ. Adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - a diffusion-tensor imaging study of the corpus callosum. Psychiatry Res. 2012;201:168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makris N, Buka SL, Biederman J, Papadimitriou GM, Hodge SM, Valera EM, et al. Attention and executive systems abnormalities in adults with childhood ADHD: A DT-MRI study of connections. Cereb Cortex. 2007;18:1210–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortese S, Imperati D, Zhou J, Proal E, Klein RG, Mannuzza S, et al. White matter alterations at 33-year follow-up in adults with childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:591–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw P, Sudre G, Wharton A, Weingart D, Sharp W, Sarlls J. White matter microstructure and the variable adult outcome of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:746–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarz CG, Reid RI, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Przybelski SA, Zuk SM, et al. Improved DTI registration allows voxel-based analysis that outperforms tract-based spatial statistics. Neuroimage. 2014;94:65–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waugh JL, Kuster JK, Makhlouf ML, Levenstein JM, Multhaupt-Buell TJ, Warfield SK, et al. A registration method for improving quantitative assessment in probabilistic diffusion tractography. Neuroimage. 2019;189:288–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leemans A Visualization of Diffusion MRI Data. In Diffusion MRI: Theory, Methods, and Applications. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010–11. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasserthal J, Neher P, Maier-Hein KH. TractSeg - fast and accurate white matter tract segmentation. Neuroimage. 2018;183:239–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeatman JD, Dougherty RF, Myall NJ, Wandell BA, Feldman HM. Tract profiles of white matter properties: automating fiber-tract quantification. PloS One. 2012;7:e49790–e49790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yendiki A, Panneck P, Srinivasan P, Stevens A, Zollei L, Augustinack J, et al. Automated probabilistic reconstruction of white-matter pathways in health and disease using an atlas of the underlying anatomy. Front Neuroinform. 2011;5:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molina B, Sibley MH, Pedersen SS, Pelham WE. The Pittsburgh ADHD Longitudinal Study. In: Hechtman L, editor. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: adult outcomes and its predictors. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 105–55. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barkley RA. Barkley adult ADHD rating scale-IV (BAARS-IV). New York. NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sibley MH, Rohde LA, Swanson JM, Hechtman LT, Molina BSG, Mitchell JT, et al. Late-onset ADHD reconsidered with comprehensive repeated assessments between ages 10 and 25. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:140–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knight RG, Williams S, McGee R, Olaman S. Psychometric properties of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:373–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts RE, Vernon SW, Rhoades HM. Effects of language and ethnic status on reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale with psychiatric patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177:581–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory. (Form Y). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wechsler D Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wechsler D Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. Second Edition. San Antonio, TX: NCS Pearson; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Behrens TE, Berg HJ, Jbabdi S, Rushworth MF, Woolrich MW. Probabilistic diffusion tractography with multiple fibre orientations: What can we gain? Neuroimage. 2007;34:144–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kochunov P, Williamson DE, Lancaster J, Fox P, Cornell J, Blangero J, et al. Fractional anisotropy of water diffusion in cerebral white matter across the lifespan. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lebel C, Gee M, Camicioli R, Wieler M, Martin W, Beaulieu C. Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tract evolution over the lifespan. Neuroimage. 2012;60:340–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westlye LT, Walhovd KB, Dale AM, Bjornerud A, Due-Tonnessen P, Engvig A, et al. Life-span changes of the human brain white matter: diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and volumetry. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:2055–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simmonds DJ, Hallquist MN, Asato M, Luna B. Developmental stages and sex differences of white matter and behavioral development through adolescence: a longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) study. Neuroimage. 2014;92:356–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKay NS, Iwabuchi SJ, Haberling IS, Corballis MC, Kirk IJ. Atypical white matter microstructure in left-handed individuals. Laterality. 2017;22:257–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann Statist. 2001;29:1165–88. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Latini F, Mårtensson J, Larsson E-M, Fredrikson M, Åhs F, Hjortberg M, et al. Segmentation of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus in the human brain: a white matter dissection and diffusion tensor tractography study. Brain Res. 2017;1675:102–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panesar SS, Yeh FC, Jacquesson T, Hula W, Fernandez-Miranda JC. A quantitative tractography study into the connectivity, segmentation and laterality of the human inferior longitudinal fasciculus. Front Neuroanat. 2018;12:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Catani M, Jones DK, Donato R, ffytche DH. Occipito-temporal connections in the human brain. Brain. 2003;126:2093–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Helenius P, Laasonen M, Hokkanen L, Paetau R, Niemivirta M. Impaired engagement of the ventral attentional pathway in ADHD. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:1889–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Damatac CG, Zwiers M, Chauvin R, van Rooij D, Akkermans SEA, Naaijen J et al. Hyperactivity-impulsivity in ADHD is associated with white matter microstructure in the cingulum’s angular bundle. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/787713v1. 2019:787713. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pelham Iii WE, Page TF, Altszuler AR, Gnagy EM, Molina BSG, Pelham WE Jr. The long-term financial outcome of children diagnosed with ADHD. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2020;88:160–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dubois J, Dehaene-Lambertz G, Perrin M, Mangin JF, Cointepas Y, Duchesnay E, et al. Asynchrony of the early maturation of white matter bundles in healthy infants: quantitative landmarks revealed noninvasively by diffusion tensor imaging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2008;29:14–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lebel C, Walker L, Leemans A, Phillips L, Beaulieu C. Microstructural maturation of the human brain from childhood to adulthood. Neuroimage. 2008;40:1044–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herbet G, Zemmoura I, Duffau H. Functional anatomy of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus: from historical reports to current hypotheses. Front Neuroanatomy. 2018;12:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lambon Ralph MA, Cipolotti L, Manes F, Patterson K. Taking both sides: do unilateral anterior temporal lobe lesions disrupt semantic memory? Brain. 2010;133:3243–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rice GE, Hoffman P, Lambon Ralph MA. Graded specialization within and between the anterior temporal lobes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1359:84–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McKinnon E, Fridriksson J, Glenn R, Jensen J, Helpern J, Basilakos A, et al. Structural plasticity of the ventral stream and aphasia recovery. Ann Neurol. 2017;82:147–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Papez JW. A proposed mechanism of emotion. 1937. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ezzati A, Katz MJ, Lipton ML, Zimmerman ME, Lipton RB. Hippocampal volume and cingulum bundle fractional anisotropy are independently associated with verbal memory in older adults. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016;10:652–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin YC, Shih YC, Tseng WY, Chu YH, Wu MT, Chen TF, et al. Cingulum correlates of cognitive functions in patients with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease: a diffusion spectrum imaging study. Brain Topogr. 2014;27:393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ranganath C, Ritchey M. Two cortical systems for memory-guided behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:713–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Catani M, Dell’acqua F, Thiebaut, de Schotten M. A revised limbic system model for memory, emotion and behaviour. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:1724–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bubb EJ, Kinnavane L, Aggleton JP. Hippocampal - diencephalic - cingulate networks for memory and emotion: an anatomical guide. Brain Neurosci Adv. 2017;1:2398212817723443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rolls ET. The cingulate cortex and limbic systems for action, emotion, and memory. Handbook Clin Neurol. 2019;166:23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Neave N, Nagle S, Sahgal A, Aggleton JP. The effects of discrete cingulum bundle lesions in the rat on the acquisition and performance of two tests of spatial working memory. Behav Brain Res. 1996;80:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eriksson H-e, Kohler C, Sundberg H. Exploratory behavior after angular bundle lesions in the albino rat. Behav Biol. 1976;17:123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Genc E, Fraenz C, Schluter C, Friedrich P, Hossiep R, Voelkle MC, et al. Diffusion markers of dendritic density and arborization in gray matter predict differences in intelligence. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Basten U, Hilger K, Fiebach CJ. Where smart brains are different: a quantitative meta-analysis of functional and structural brain imaging studies on intelligence. Intelligence. 2015;51:10–27. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Deary IJ, Penke L, Johnson W. The neuroscience of human intelligence differences. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:201–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee SS, Humphreys KL, Flory K, Liu R, Glass K. Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:328–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.