Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Receiving a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias (ADRD) can be pivotal and stressful period. We examined the risk of suicide in the first year following ADRD diagnosis relative to the general geriatric population.

METHODS:

We identified a national cohort of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries aged ≥ 65 years with newly diagnosed ADRD (n=2,667,987) linked to the National Death Index.

RESULTS:

The suicide rate for the ADRD cohort was 26.42 per 100,000 person-years. The overall standardized mortality ratio (SMR) for suicide was 1.53 (95%CI=1.42, 1.65) with the highest risk among adults aged 65-74 years (SMR=3.40, 95%CI=2.94, 3.86) and the first 90 days following ADRD diagnosis. Rural residence and recent mental health, substance use, or chronic pain conditions were associated with increased suicide risk.

DISCUSSION:

Results highlight the importance of suicide risk screening and support at the time of newly diagnosed dementia, particularly for patients aged < 75 years.

1) INTRODUCTION

As people age, many fear developing Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias (ADRD).1,2 After being diagnosed with ADRD, feelings of loss, anger, and uncertainty are common and for some adults the experience is particularly traumatic.3,4 Suicide risk increases with age and is highest among older adults in the U.S. and many regions of the world.5,6 In 2018, the most recent year for which U.S. national data are available, the suicide rate for adults aged 65+ years was 17.36 per 100,000, compared to 14.21 in the general population.5 At a time when the U.S. suicide rate among older adults has acclerated7 and the number of older adults with ADRD is increasing,8 research is needed to quantify suicide risk in older adults with newly diagnosed dementia and to identify patient characteristics that place geriatric patients at increased short-term risk for suicide.

Prior reviews9,10 concluded that the risk of suicide in patients with dementia appears to be equal to that of the age-matched general population, but noted that most studies had significant methodological limitations. Findings from large, cohort studies are mixed. A Danish cohort study11 observed a 3- to 10-fold increased risk of suicide in adults aged ≥50 years with dementia, however the cohort was limited to persons diagnosed with dementia during hospitalization, thus representing a subsample of all dementia cases. A more recent Danish cohort study12 of persons aged ≥15 years found suicide rates were lower overall for ADRD, but did not include persons diagnosed in primary care where most cases are diagnosed.13 A Korean cohort study of memory clinic patients found no significant association with suicide risk compared to the age- and sex-matched population.14 Conversely, a separate Korean study of adults aged ≥60 years with newly diagnosed ADRD had an increased risk of suicide death in the first year following dementia diagnosis compared to propensity-scored matches without dementia.15

One cohort study with U.S. Veterans aged ≥60 years with dementia found predictors of death by suicide included depression, anxiolytic use, and prior psychiatric hospitalization.16 However, depression was not a predictor of suicide death in a retrospective, cohort study of adults with dementia in the U.S. state of Georgia.17 More research is needed given the paucity of nationally representative U.S. data to examine variations in risk of suicide after dementia diagnosis and to identify which subgroups of patients are most at risk.

Suicide risk may be higher during the early stages of ADRD and then decreases during more advanced stages of the disease as individuals become less cognitively and functionally capable of acting on suicidal impulses.18 Suicide risk may also vary by dementia subtype with evidence that non-fatal suicidal behaviors and depression are more prevalent in frontotemporal and vascular dementia,19 whereas suicidal ideation may be highest for adults with Lewy body and vascular dementia.20

To our knowledge, we present the first U.S. national study of suicide risk among adults aged ≥65 years during the first 12 months following a new dementia diagnosis. We followed a cohort of Medicare fee-for-services beneficiaries with a new diagnosis to examine risk of suicide within the first 12 months following the first observed clinical diagnosis of ADRD. Because suicidal ideation and deliberate self-harm are among the strongest predictors of suicide death,21 we also examined 12-month risk of non-fatal suicidal events. We analyzed risks by dementia subtype, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and recent healthcare use. Standardized mortality ratios were calculated to quantify the excess risk of suicide death during the first year following dementia diagnosis.

2) METHODS

2.1) Sources of Data

The incident dementia cohort was extracted from the 2012-2015 national Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) files and fee-for-service outpatient and carrier claims. Dates and cause of death information were derived from linkage to the National Death Index (NDI), which provides a complete accounting of recorded deaths in the U.S.22 Medicare and NDI files were obtained from the Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC) and included a unique identification beneficiary number for every beneficiary that links all files. The total resident population and death information were obtained from the U.S. Compressed Mortality File for January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2016 .23 Ascertainment of suicide death for the dementia cohort and resident population were both derived from death certificates submitted to the National Vital Statistics System. The data, which are deidentified, were deemed to be exempt from human participants review by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. This study was prepared in accordance with the standards set forth by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

2.2) Dementia Cohort Assembly and Follow-up

We first identified a national retrospective longitudinal cohort of beneficiaries with dementia based on ADRD diagnosis on ≥1 outpatient or ≥1 inpatient claim (ICD-9 code 290.0, 290.1×, 290.2×, 290.3, 290.4×, 294.1×, 294.2×, 331.0, 331.1×, 331.82; ICD-10 code F01.50, F01.51, F02.80, F02.81, F03.90, F03.91, G30.0, G30.1, G30.8, G30.9, G31.01, G31.09, G31.83). We then identified the first recorded ADRD diagnosis in a face-to-face encounter (Revenue Center codes 0510-0529, BETOS M-codes for evaluation and management) to reduce false positives in case ascertainment (e.g., dementia diagnosis associated with labs ordered as part of a differential diagnosis). We further limited the cohort to beneficiaries without any claim for an ADRD diagnosis in the previous 12 months (i.e., a 365-day pre-washout period without ADRD diagnosis) during the 2012-2015 ascertainment period. The final cohort was restricted to beneficiaries who were ≥65 years of age on the index diagnosis date and had continuous Medicare enrollment for at least 180 days before the index ADRD diagnosis date. The cohort was followed until date of death or 12 months after the index diagnosis date, whichever came first.

2.3) Outcomes

Suicide mortality was defined as an underlying cause of death coded as intentional self-injury/suicide (ICD-10 codes X60-X84, Y87.0, U03), consistent with the US federal definition of suicide death used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.24 Non-fatal suicidal events included emergency department or inpatient encounters for intentional self-injury (ICD-9 codes E950-958; ICD-10: X71–X83, T36–T50 with a 6th character of 2, T51–T65 with a 6th character of 2, T71 with a 6th character of 2), attempted suicide (ICD-10 code T14.91), or suicidal ideation (ICD-9 code V62.84; ICD-10 code R45.851).25

2.4) Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Based on Medicare eligibility data, cohort members were classified by sex, age (65-74, 75-84, and 85+ years), and race/ethnicity (Hispanic, white non-Hispanic [white], black non-Hispanic [black], and other), and low-income subsidy eligibility for Medicare Part D. Cohort members were also classified as residing in either urban or rural counties derived from 2013 rural-urban continuum codes.26

Dementia subtype was categorized as either Alzheimer’s disease/senile dementia ([AD], ICD-9 290.0, 290.2×, 290.3, 331.0; ICD-10 G30.0, G30.1, G30.8, G30.9), frontotemporal dementia ([FTD], ICD-9 311.11, 331.19; ICD-10 G31.0, G31.01, G31.09), dementia with Lewy bodies ([DLB], ICD-9 331.82; ICD-10 G31.83), vascular dementia ([VaD], ICD-9 290.4×; ICD-10 F01×), or unspecified dementia (ICD-9 294.1×, 294.2×; ICD-10 F02.8×, F03.9×). Most patients (90.15%) received a single ADRD diagnosis at the index encounter. Patients who received diagnoses for ≥2 dementia subtypes at index (9.85% of the cohort) were assigned a single dementia subtype based on estimated prevalence.27

Variables representing mental health treatment ≤180 days before the index dementia diagnosis date were used to characterize depressive, bipolar, anxiety, psychotic, personality, developmental, disruptive, adjustment, and other mental disorders (see Table S1). At least one claim defined each mental disorder group. Similar steps were used to identify substance use disorders and co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Separate variables defined any inpatient, outpatient, or emergency department treatment for a mental health or substance use disorder during the ≤180 days preceding the index ADRD diagnosis date. Severity of medical comorbidity was evaluated with the Elixhauser Comorbidity Scale, excluding mental health, substance use, and neurological disorders.28 Chronic pain was classified using a previously developed research algorithm for administrative data29 (Table S2).

2.5) Statistical Analysis

For the study population, we determined person-years of follow-up, number of suicide deaths and non-fatal suicidal events, and rates per 100,000 person-years overall and stratified by sociodemographic characteristics, dementia subtypes, and clinical characteristics. For each characteristic, separate Fine-Gray competing risk regression models30 were used to determine the incidence, predictive factors, and associated subhazard ratios (HRs) for suicide death and the first non-fatal suicidal event using the SAS PHREG procedure with the log-link function. All models controlled for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity to produce adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the entire dementia cohort and stratified by age, sex, and race/ethnicity groups. SMRs were defined as the cause-specific ratio of the observed number of suicide deaths in the dementia cohort to the number of suicide deaths expected in the same cohort based on data from the general US population (January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2016, US Compressed Mortality File).23 The SAS PROC STDRATE procedure used indirect standardization to derive SMRs separately by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Cumulative incidence functions were plotted for suicide deaths within the first year following dementia diagnosis. Tests were 2-sided with a P < .05 set as the level of statistical significance. Data were analyzed from March 10 to November 18, 2020.

3) RESULTS

3.1) Characteristics of Study Cohort

A total of 2,667,987 older adults with newly diagnosed dementia were identified (62.2% women, 82.5% non-Hispanic White, 46.5% aged 85+ years) (Table 1). Most individuals (67.1%) were diagnosed with unspecified dementia. Half (48.2%) of the patients also had a recent mental diagnosis and 13.9% were hospitalized for mental health care within the 180 days prior to index ADRD diagnosis. Nearly half of the dementia cohort had chronic pain (42.9%) and 4 or more comorbid medical conditions (43.9%).

Table 1:

Characteristics for Suicide Mortality or Non-fatal Suicidal Event in Older Adult Medicare Beneficiaries During the First Year Following Dementia Diagnosis

| Characteristic | Total Population (N=2,667,987) (%) |

1-year Suicide Mortality (N=705) (%) |

1-year Non-Fatal Suicidal Event (N= 19,382) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 100.00 | 0.03 | 0.73 |

| Sex | |||

| Male (n=1,009,337) | 37.83 | 80.28 | 43.58 |

| Female (n=1,658,650) | 62.17 | 19.72 | 56.42 |

| Age, years | |||

| 65-74 (n=425,824) | 15.96 | 29.36 | 35.35 |

| 75-84 (n=1,002,473) | 37.57 | 45.25 | 38.95 |

| 85+ (n=1,239,690) | 46.47 | 25.39 | 25.70 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic (n=2,201,039) | 82.50 | 91.49 | 86.40 |

| Black, non-Hispanic (n=240,90) | 9.03 | 2.98 | 6.04 |

| Hispanic (n=139,055) | 5.21 | 3.26 | 4.92 |

| Other (n=86,973) * | 3.26 | 2.27 | 2.64 |

| County Type | |||

| Urban (n=2,261,106) | 84.39 | 78.58 | 86.52 |

| Rural (n=406,881) | 15.61 | 21.42 | 13.48 |

| Low Income Subsidy | |||

| No (n=1,962,639) | 73.56 | 85.67 | 68.98 |

| Yes (n=705,348) | 26.44 | 14.33 | 31.02 |

| Dementia Type at Index Visit | |||

| Dementia Unspecified (n=1,510,774) | 56.63 | 57.45 | 58.54 |

| Alzheimer’s (n=918,092) | 34.41 | 30.92 | 30.11 |

| Vascular (n=179,564) | 6.73 | 7.52 | 8.54 |

| Lewy body (n= 49,126) | 1.84 | 2.27 | 2.12 |

| Frontotemporal (n=10,431) | 0.39 | 1.84 | 0.70 |

| Any mental disorder diagnosis (n=1,286,644) ** | 48.23 | 59.15 | 73.89 |

| Depressive disorder (n= 564,294) | 21.15 | 38.01 | 49.79 |

| Bipolar disorder (n=46,353) | 1.74 | 4.54 | 11.10 |

| Anxiety disorder (n= 376,906) | 14.13 | 27.80 | 35.00 |

| Schizophrenia disorder (n=35,612) | 1.33 | 1.28 | 6.25 |

| Personality disorder (n=9,992) | 0.37 | 1.56 | 2.96 |

| Developmental disorders (n=236,014) | 8.85 | 5.53 | 10.01 |

| Disruptive behavior disorders (n=16,370) | 0.61 | 1.42 | 2.81 |

| Adjustment-related disorders (n=87,232) | 3.27 | 6.67 | 8.67 |

| Substance use disorders (n=189,960)** | 7.12 | 14.33 | 19.70 |

| Alcohol use disorder (n=163,772) | 6.14 | 12.06 | 16.93 |

| Drug use disorder (n=36,137) | 1.35 | 4.11 | 5.35 |

| Other mental disorder (n=376,937) | 14.13 | 14.18 | 19.23 |

| Co-occurring substance and mental disorder diagnosis (n=189,960)** | 7.12 | 14.33 | 19.70 |

| Any inpatient mental health care (n=370,808)** | 13.90 | 23.83 | 33.02 |

| Any outpatient mental health care (n=1,105,339)** | 41.43 | 53.48 | 67.21 |

| Any emergency mental health care (n=314,199)** | 11.78 | 24.68 | 33.83 |

| Medical | |||

| Pain (n=1,145,526)** | 42.94 | 48.51 | 51.95 |

| # of comorbid conditions** | |||

| 0 (n=310,775) | 11.65 | 12.20 | 9.04 |

| 1 (n=362,780) | 13.60 | 14.47 | 11.55 |

| 2-3 (n=823,64) | 30.87 | 35.18 | 30.18 |

| 4-5 (n=571,394) | 21.42 | 20.28 | 23.13 |

| 6+ (n=599,410) | 22.47 | 17.87 | 26.10 |

Includes American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and more than one race.

During 180 days prior to index date.

A total of 705 suicide deaths (566 men and 139 women) were recorded within the first 12 months following dementia diagnosis. This number represented 0.03% of all deaths. The leading methods of suicide were by firearm (63.3%), self-poisoning (15.6%), and hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (12.8%). A total of 19,382 patients were treated in a hospital setting for a non-fatal suicidal event (8,198 men and 10,590 women), which represented 0.73% of the cohort.

3.2) Variation in Suicide Risk by Dementia Type

The crude 12-month suicide rate of the overall cohort was 26.42 per 100,000 person-years (Table 2). Suicide rates ranged from 124.63 per 100,000 person-years for frontotemporal dementia to 23.74 per 100,000 person-years for Alzheimer’s disease. Compared to unspecified dementia, frontotemporal dementia was associated with significantly greater risk of suicide death (AHR=2.91, 95% CI=1.67-5.05) after adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease were less likely to have a non-fatal suicidal event (AHR=0.83, 95% CI=0.81-0.86), whereas patients with vascular dementia were more likely (AHR=1.08, 95% CI=1.02-1.13), relative to patients with unspecified dementia.

Table 2:

Rates and Adjusted Hazard Ratios (AHRs) of Suicide Mortality or Non-fatal Suicidal Event in Older Adult Medicare Beneficiaries During the First Year Following Dementia Diagnosis

| Characteristic | Suicide Mortality Per 100,000 person-years |

Non-Fatal Suicidal Event Per 100,000 person-years |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | AHR (95% CI) | Rate | AHR (95% CI) | |

| Total | 26.42 | 0.73 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male (n=1,009,337) | 56.08 | -ref- | 0.84 | -ref- |

| Female (n=1,658,650) | 8.38 | 0.16(0.14, 0.20) | 0.66 | 0.88(0.86, 0.91) |

| Age, years | ||||

| 65-74 (n=425,824) | 48.61 | -ref- | 0.26 | -ref- |

| 75-84 (n=1,002,473) | 31.82 | 0.67(0.56, 0.79) | 0.75 | 0.46(0.44, 0.47) |

| 85+ (n=1,239,690) | 14.44 | 0.34(0.28, 0.42) | 0.40 | 0.24(0.23, 0.25) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic (n=2,201,039) | 29.30 | -ref- | 0.76 | -ref- |

| Black, non-Hispanic (n=240,90) | 8.72 | 0.26(0.17, 0.40) | 0.49 | 0.53(0.50, 0.57) |

| Hispanic (n=139,055) | 16.54 | 0.51(0.33, 0.77) | 0.69 | 0.78(0.73, 0.84) |

| Other* (n=86,973) | 18.40 | 0.58(0.35, 0.94) | 0.59 | 0.70(0.64, 0.76) |

| County Type | ||||

| Urban (n=2,261,106) | 24.50 | -ref- | 0.74 | -ref- |

| Rural (n=406,881) | 37.11 | 1.38(1.15,1.65) | 0.64 | 0.82(0.78,0.85) |

| Low Income Subsidy | ||||

| No (n=1,962,639) | 30.77 | -ref- | 0.68 | -ref- |

| Yes (n=705,348) | 14.32 | 0.59(0.47,0.73) | 0.85 | 1.25(1.21,1.29) |

| Dementia Type | ||||

| Dementia Unspecified (n=1,510,774) | 26.81 | -ref- | 0.78 | -ref- |

| Alzheimer’s (n=918,092) | 23.74 | 0.91(0.77,1.07) | 0.65 | 0.83(0.81,0.86) |

| Vascular (n=179,564) | 29.52 | 0.95(0.71,1.26) | 0.92 | 1.08(1.02,1.13) |

| Lewy body (n= 49,126) | 32.57 | 0.78(0.47,1.28) | 0.84 | 0.91(0.82,1.00) |

| Frontotemporal (n=10,431) | 124.63 | 2.91(1.67,5.05) | 1.36 | 1.13(0.95,1.34) |

| Any mental disorder diagnosis (n=1,286,644) ** | 32.41 | 1.50(1.29,1.74) | 1.11 | 2.69(2.61,2.78) |

| Depressive disorder (n= 564,294) | 47.49 | 2.34(2.01,2.72) | 1.71 | 3.27(3.17,3.36) |

| Bipolar disorder (n=46,353) | 69.04 | 2.17(1.52,3.09) | 4.64 | 4.86(4.64,5.09) |

| Anxiety disorder (n= 376,906) | 52.00 | 2.63(2.22,3.11) | 1.80 | 2.92(2.84,3.01) |

| Psychotic disorders (n=35,612) | 25.27 | 0.78(0.40,1.51) | 1.62 | 3.34(3.15,3.54) |

| Personality disorder (n=9,992) | 110.09 | 3.20(1.76,5.81) | 5.73 | 5.74(5.28,6.24) |

| Developmental disorders (n=236,014) | 16.52 | 0.61(0.44,0.84) | 0.82 | 1.15(1.10,1.20) |

| Disruptive behavior disorders (n=16,370) | 61.09 | 1.59(0.85,2.97) | 3.33 | 3.42(3.14,3.73) |

| Adjustment-related disorders (n=87,232) | 53.88 | 1.94(1.45,2.61) | 1.93 | 2.49(2.37,2.62) |

| Substance use disorders (n=189,960)** | 53.17 | 1.44(1.16,1.79) | 2.01 | 2.32(2.24,2.41) |

| Alcohol use disorder (n=163,772) | 51.90 | 1.33(1.05,1.68) | 2.00 | 2.21(2.12,2.30) |

| Drug use disorder (n=36,137) | 80.25 | 2.53(1.74,3.66) | 2.87 | 3.10(2.91,3.31) |

| Other mental disorder (n=376,937) | 26.53 | 0.96(0.78,1.18) | 0.99 | 1.40(1.35,1.45) |

| Co-occurring substance and mental disorder diagnosis (n=189,960)** | 53.17 | 1.44(1.16,1.79) | 2.01 | 2.32(2.24,2.41) |

| Any inpatient mental health care (n=370,808)** | 45.31 | 1.69(1.42,2.02) | 1.73 | 2.60(2.52,2.68) |

| Any outpatient mental health care (n=1,105,339)** | 34.11 | 1.58(1.36,1.83) | 1.18 | 2.56(2.48,2.64) |

| Any emergency mental health care (n=314,199)** | 55.38 | 2.32(1.95,2.76) | 2.09 | 3.45(3.34,3.55) |

| Medical | ||||

| Pain (n=1,145,526)** | 29.86 | 1.24(1.07,1.44) | 0.88 | 1.36(1.33,1.40) |

| # of comorbid conditions** | ||||

| 0 (n=310,775) | 27.67 | -ref- | 0.56 | -ref- |

| 1 (n=362,780) | 28.12 | 1.04(0.78,1.38) | 0.62 | 1.11(1.04,1.18) |

| 2-3 (n=823,64) | 30.11 | 1.17(0.92,1.50) | 0.71 | 1.31(1.25,1.39) |

| 4-5 (n=571,394) | 25.03 | 1.01(0.77,1.32) | 0.78 | 1.46(1.38,1.54) |

| 6+ (n=599,410) | 21.02 | 0.90(0.69,1.19) | 0.84 | 1.48(1.40,1.56) |

Adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) models controlled for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Values in bold indicate significant risks ratios at p < .05.

Includes American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and more than one race.

During 180 days prior to index diagnosis date.

3.3) Characteristics Associated with Risk of Suicide and Non-Fatal Suicidal Events

After adjusting for sex, age, race/ethnicity, rural residence was associated with greater likelihood of suicide, but lower likelihood of a non-fatal suicidal event (Table 2). Conversely, persons qualifying for the low-income subsidy were at lower risk for suicide, but at greater risk for a non-fatal suicidal event. Most mental disorders and substance use diagnoses were associated with significantly greater risk of suicide and non-fatal suicidal outcomes, particularly personality disorder. Suicide rates were elevated for individuals who had recent mental health related outpatient visits (34.11 per 100,000 person-years), inpatient stays (45.31 per 100,000 person-years), and emergency departments encounters (55.38 per 100,000 person-years). Recent clinical diagnoses of chronic pain conditions were associated with greater risk of suicide and non-fatal suicidal event. Severity of medical comorbidity was unrelated to suicide death, but monotonically associated with increased risk of non-fatal suicidal event.

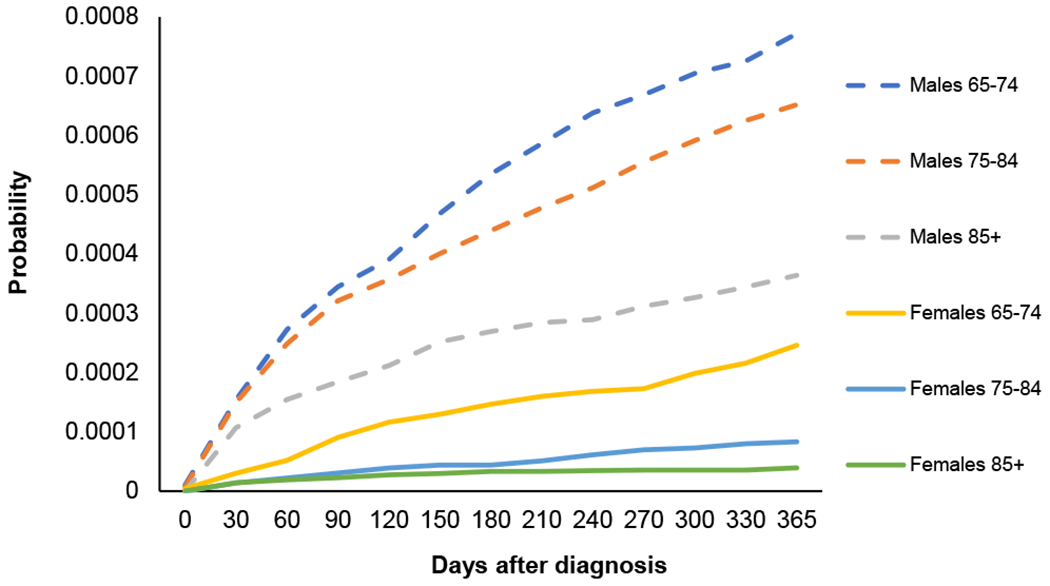

3.4) Suicide Risk Compared to the General Population

In relation to the general population, the overall suicide SMR for the dementia cohort was 1.53 (95% CI=1.42, 1.65) (Table 3). All stratified SMRs were significant. The SMR for women was 2.04 (95% CI=1.70, 2.38) and for men it was 1.44 (95% CI=1.32,1.56). Excess risk of suicide was observed across race/ethnicity, including non-white adults (SMRs > 2.0) and white, non-Hispanic adults (SMR=1.50). The suicide SMR tended to decline with increasing age from 65-74 years (SMR=3.40), 75-84 years (SMR=1.87), to 85+ years (SMR=0.78). Cumulative incidence functions (Figure 1) stratified by sex and age group revealed that roughly half of all suicide deaths (41.7% among females, 48.4% among males) occurred within the first 90 days following index dementia diagnosis.

Table 3.

Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMR) for Suicide Mortality During the First Year Following Dementia Diagnosis, Stratified by Sex, Age, and Race/Ethnicity

| Total (per 100,000) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Suicide Mortality Crude Rate (95% CI) |

Observed events | Expected events | SMR (95% CI) |

| Total | 26.42 (24.50, 28.40) | 705 | 460.1 | 1.53(1.42, 1.65) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 56.08 (51.50,60.70) | 566 | 392.1 | 1.44(1.32, 1.56) |

| Female | 8.38 (7.00, 9.00) | 139 | 68.0 | 2.04(1.70, 2.38) |

| Age, years | ||||

| 65-74 | 48.61 (42.00, 55.20) | 207 | 60.9 | 3.40(2.94, 3.86) |

| 75-84 | 31.82 (28.30, 35.30) | 319 | 170.8 | 1.87(1.66, 2.07) |

| 85+ | 14.44 (12.30, 16.60) | 179 | 228.4 | 0.78(0.67, 0.90) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 29.30 (27.00, 31.60) | 645 | 431.3 | 1.50(1.38, 1.61) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 8.72 (5.00, 12.40) | 21 | 10.1 | 2.08(1.19, 2.97) |

| Hispanic | 16.54 (9.80, 23.30) | 23 | 10.8 | 2.12(1.26, 2.99) |

| Other* | 18.40 (9.40, 27.40) | 16 | 7.8 | 2.04(1.04, 3.04) |

Includes American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and more than one race.

Mortality data for the dementia cohort are from the National Death Index. General population mortality data are from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER data.23

Figure 1:

Cumulative Incidence of Suicide Mortality During First Year Following Dementia Diagnosis Considering Competing Risk by Sex and Age Group

4) DISCUSSION

In this national study of over two million U.S. older adults, we found that the number of observed suicide deaths within the first year of newly diagnosed dementia was approximately 53% higher than expected when compared to the general population of older adults. The risk of suicide was particularly elevated among adults aged 65-74 years (SMR=3.40) with roughly half of all suicide deaths occurring within the first 90 days of dementia diagnosis. In absolute terms, we found frontotemporal dementia was associated with the highest suicide rate (124.6 per 100,000 person-years vs. 26.42 for the overall dementia cohort). Our study identified a number of specific factors associated with higher risk of suicide and non-fatal suicidal events, which may assist health care providers in decisions regarding appropriate, potentially life-saving care during the critical period following initial clinical dementia diagnosis.

To our knowledge, this is the first U.S. cohort study to compare suicide risk by dementia subtype. Frontotemporal dementia has been associated with higher risk of non-fatal suicidal acts, but samples were small and did not examine suicide deaths.31–33 Data are scarce on suicide risk in dementia with Lewy bodies, which we found to have the second highest rate of suicide (32.57 per 100,000 person-years). The current study also addresses other limitations in prior cohort studies that were limited to more narrowly selected samples, such as patients diagnosed with dementia during hospitalization,11 in settings other than primary care,12 or in memory clinics.14 By identifying patients regardless of health care setting and stratifying suicide risk by dementia subtype, the current findings have important implications for the clinical care of patients with newly diagnosed dementia.

The results should be interpreted with caveats. Frontotemporal dementia is commonly misdiagnosed in non-specialist settings34 and incident cases occurring after age 65 years are rare.35 Similarly, personality changes and neuropsychiatric symptoms are common precursors to dementia36,37, which create some uncertainty about the diagnostic accuracy of personality disorder and other mental disorders during the pre-index dementia diagnosis. Also, the data used to estimate SMRs were based on mortality patterns from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2016, which was a period marked by increasing U.S. suicide rates for males and females aged 65-74 years,7 and may not generalize to other epochs. Similarly, SMRs may be biased due to residual confounding as they were unadjusted for potential covariates.

Consistent with prior research, recent mental health and substance use disorders were robustly associated with suicide and non-fatal suicidal outcomes.38 Also, rural residence was associated greater risk of suicide death and lower likelihood of non-fatal outcomes resulting in hospital-based care.39 Contrary to prior research, we found that beneficiaries who qualified for low-income subsidies were at reduced risk of suicide death, but at higher risk of non-fatal suicidal outcomes. In the general population, low household income is associated with increased risk of suicide attempts and death.40 We were surprised to observe that severity of medical comorbidity was largely unrelated to suicide death, but monotonically associated with risk of non-fatal suicidal outcomes. Prior research in the general population suggests physical morbidity and multi-morbidity confer risk for fatal and non-fatal suicidal events, even after controlling for sociodemographic and mental health variables.41,42 Further research is needed to explore the relationships of income and physical morbidity to suicide risk among older adults with newly diagnosed dementia.

This study has several potential limitations. First, we are unable to validate the accuracy of diagnoses, including mental health diagnoses and dementia subtypes, in Medicare claims data which may not include all new cases of dementia.43 Second, our analyses did not include Medicare Advantage enrollees, who tend to be healthier with lower rates of ADRD44–47 and more likely to initiate mental health care than fee-for-service Medicare enrollees even after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and mental and physical health.48 Third, information was not available concerning clinical suicide risk factors such as lifetime history of self-harm,21 proximal stressful life events,49 social disconnection (e.g., marital status, loneliness),50 and access to lethal means. Fourth, data for non-fatal suicide events are limited to episodes that resulted in hospital-based care and concerns exist over the validity and completeness of ICD codes for receipt of care for non-fatal suicide in claims data.51,52 Fifth, various factors may contribute to under-reporting and misclassification of suicide as cause of death in the National Vital Statistics System.53,54 Finally, although our analyses accounted for competing risks, other causes of death may complicate detection of and contribute to underestimated counts of suicide deaths in older adults, particularly in the ≥75 years of age group.

The clinical and policy implications of these results highlight the importance of suicide risk screening and support at the time of diagnosing incident dementia, particularly for patients who are younger (i.e., aged 65-74 years), where the diagnosis is of frontotemporal dementia, and for patients with a recent history of chronic pain or mental health or substance use disorders. Additionally, lethal means restriction and safety counseling may be appropriate with patients and caregivers, including safe storage or removal of firearms.55 It is estimated that half of U.S. older adults have a firearm in the home,56 one-fourth of whom report unlocked and loaded gun storage.57 Presence of a firearm in the home has been associated with increased risk for suicide in later life, even after controlling for psychiatric illness.58

5) CONCLUSIONS

Older adults recently diagnosed with dementia are at elevated risk of suicide during the first 12 months following diagnosis, particularly during the first 90 days. Patients aged 65-74 years or diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia have the highest risk. Recent mental health, substance use, and chronic pain conditions are associated with higher likelihoods of fatal and non-fatal suicidal outcomes within 12 months of newly diagnosed dementia. Many older adults feel loss, anger, and uncertainty after being diagnosed with dementia. During this critical, transitional period, these findings support active management of pre-existing mental disorders, thorough assessment of patient and caregiver needs, initiating referrals for services and supports, and restricting access to lethal means.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01MH107452 and R01AG056407]. The supporters had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or publication of this study.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr. Marcus has served as a consultant to Allergan outside the submitted work. The other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

References

- 1.Maust DT, Solway E, Langa KM, et al. Perception of dementia risk and preventive actions among US adults aged 50 to 64 years. JAMA Neurology. 2020;77(2):259–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.YouGov America poll. (2020). Available at: https://today.yougov.com/topics/health/articles-reports/2020/01/08/alzheimers-dementia-poll-survey. Last accessed Oct. 30, 2020.

- 3.Bunn F, Goodman C, Sworn K, et al. Psychosocial Factors That Shape Patient and Carer Experiences of Dementia Diagnosis and Treatment: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. PLoS Med. 2012;9(10):e1001331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Kutzleben M, Schmid W, Halek M, Holle B, Bartholomeyczik S. Community-dwelling persons with dementia: What do they need? What do they demand? What do they do? A systematic review on the subjective experiences of persons with dementia. Aging & mental health. 2012;16(3):378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NCfIPaC. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). 2021; https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

- 6.World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: A global imperative. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Increase in suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 362. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged ≥65 years. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2019;15(1):17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serafini G, Calcagno P, Lester D, Girardi P, Amore M, Pompili M. Suicide risk in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Current Alzheimer research. 2016;13(10):1083–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haw C, Harwood D, Hawton K. Dementia and suicidal behavior: a review of the literature. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(3):440–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erlangsen A, Zarit SH, Conwell Y. Hospital-diagnosed dementia and suicide: a longitudinal study using prospective, nationwide register data. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(3):220–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erlangsen A, Stenager E, Conwell Y, et al. Association Between Neurological Disorders and Death by Suicide in Denmark. JAMA. 2020;323(5):444–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drabo EF, Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, Chang Chui H, Zissimopoulos J. Longitudinal analysis of dementia diagnosis and specialty care among racially diverse Medicare beneficiaries. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(11):1402–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.An JH, Lee KE, Jeon HJ, Son SJ, Kim SY, Hong JP. Risk of suicide and accidental deaths among elderly patients with cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2019;11(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi JWP, Lee KSMDP, Han EP. Suicide risk within 1 year of dementia diagnosis in older adults: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience : JPN. 2021;46(1):E119–E127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seyfried LS, Kales HC, Ignacio RV, Conwell Y, Valenstein M. Predictors of suicide in patients with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(6):567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annor FB, Bayakly RA, Morrison RA, et al. Suicide Among Persons With Dementia, Georgia, 2013 to 2016. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2019;32(1):31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Draper B, Peisah C, Snowdon J, Brodaty H. Early dementia diagnosis and the risk of suicide and euthanasia. Elsevier; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai AX, Kaup AR, Yaffe K, Byers AL. High Occurrence of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior Across Dementia Subtypes. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2018;26(12):1191–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmstrand C, Rahm Hallberg I, Saks K, et al. Associated factors of suicidal ideation among older persons with dementia living at home in eight European countries. Aging & Mental Health. 2020:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2016;143(2):187–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wojcik NC, Huebner WW, Jorgensen G. Strategies for using the National Death Index and the Social Security Administration for death ascertainment in large occupational cohort mortality studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010;172(4):469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CDC WONDER. Compressed Mortality File: underlying cause-of-death. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mortsql.html. Accessed October 17, 2020.

- 24.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian B, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2016. 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedegaard H, Schoenbaum M, Claassen C, Crosby A, Holland K, Proescholdbell S. Issues in developing a surveillance case definition for nonfatal suicide attempt and intentional self-harm using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coded data. National Health Statistics Reports. 2018;108:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Rural-urban continuum codes (2013). https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/. Accessed July 23, 2020. .

- 27.Goodman RA, Lochner KA, Thambisetty M, Wingo TS, Posner SF, Ling SM. Prevalence of dementia subtypes in United States Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, 2011-2013. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(1):28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med. Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Fortin M, et al. Methods for identifying 30 chronic conditions: application to administrative data. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2015;15(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American statistical association. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zucca M, Rubino E, Vacca A, et al. High risk of suicide in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®. 2019;34(4):265–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fonseca L, Duarte J, Machado Á, Sotiropoulos I, Lima C, Sousa N. Suicidal behaviour in frontotemporal dementia patients-a retrospective study. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fremont R, Grafman J, Huey ED. Frontotemporal Dementia and Suicide; Could Genetics be a Key Factor? American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®. 2020;35:1533317520925982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shinagawa S, Catindig JA, Block NR, Miller BL, Rankin KP. When a Little Knowledge Can Be Dangerous: False-Positive Diagnosis of Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia among Community Clinicians. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2016;41(1–2):99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogan DB, Jetté N, Fiest KM, et al. The Prevalence and Incidence of Frontotemporal Dementia: a Systematic Review. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques. 2016;43(S1):S96–S109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caselli RJ, Langlais BT, Dueck AC, et al. Personality Changes During the Transition from Cognitive Health to Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018;66(4):671–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan Y, Shea Y-F, Li S, et al. Prevalence of mild behavioural impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychogeriatrics. 2021;21(1):100–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Too LS, Spittal MJ, Bugeja L, Reifels L, Butterworth P, Pirkis J. The association between mental disorders and suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of record linkage studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;259:302–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conner A, Azrael D, Miller M. Suicide Case-Fatality Rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019;171(12):885–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Näher A-F, Rummel-Kluge C, Hegerl U. Associations of Suicide Rates With Socioeconomic Status and Social Isolation: Findings From Longitudinal Register and Census Data. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;10(898). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei MY, Mukamal KJ. Multimorbidity and Mental Health-Related Quality of Life and Risk of Completed Suicide. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019;67(3):511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stickley A, Koyanagi A, Ueda M, Inoue Y, Waldman K, Oh H. Physical multimorbidity and suicidal behavior in the general population in the United States. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;260:604–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y, Tysinger B, Crimmins E, Zissimopoulos JM. Analysis of dementia in the US population using Medicare claims: Insights from linked survey and administrative claims data. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2019;5:197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ndumele CD, Elliott MN, Haviland AM, et al. Differences in Hospitalizations Between Fee-for-Service and Medicare Advantage Beneficiaries. Med. Care. 2019;57(1):8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meyers DJ, Belanger E, Joyce N, McHugh J, Rahman M, Mor V. Analysis of drivers of disenrollment and plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. JAMA internal medicine. 2019;179(4):524–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byhoff E, Harris JA, Ayanian JZ. Characteristics of decedents in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. JAMA internal medicine. 2016;176(7):1020–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jutkowitz E, Bynum JPW, Mitchell SL, et al. Diagnosed prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in Medicare Advantage plans. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 2020;12(1):e12048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jimenez D, Cook BL. How Medicare Advantage Has Impacted Mental Health Service Utilization. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;24(3):S168–S169. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmutte TJ, Wilkinson ST. Suicide in Older Adults With and Without Known Mental Illness: Results From the National Violent Death Reporting System, 2003-2016. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fässberg MM, Orden KAv, Duberstein P, et al. A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2012;9(3):722–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walkup JT, Townsend L, Crystal S, Olfson M. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying suicide or suicidal ideation using administrative or claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2012;21(S1):174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Randall JR, Roos LL, Lix LM, Katz LY, Bolton JM. Emergency department and inpatient coding for self-harm and suicide attempts: Validation using clinician assessment data. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2017;26(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tøllefsen IM, Hem E, Ekeberg Ø. The reliability of suicide statistics: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gray D, Coon H, McGlade E, et al. Comparative Analysis of Suicide, Accidental, and Undetermined Cause of Death Classification. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2014;44(3):304–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Betz ME, McCourt AD, Vernick JS, Ranney ML, Maust DT, Wintemute GJ. Firearms and Dementia: Clinical Considerations. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;169(1):47–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parker K, Horowitz J, Igielnik R, Oliphant B, Brown A. America’s complex relationship with guns: an in-depth look at the attitudes and experiences of US adults. Pew Research Center; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morgan ER, Gomez A, Rivara FP, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Household firearm ownership and storage, suicide risk factors, and memory loss among older adults: results from a statewide survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019;171(3):220–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Connor K, Eberly S, Cox C, Caine ED. Access to firearms and risk for suicide in middle-aged and older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2002;10(4):407–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.