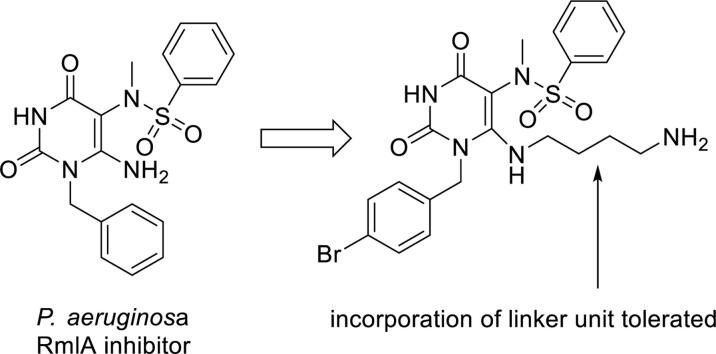

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Antibacterial drug discovery, Bacterial cell wall synthesis, RmlA, Structure-based optimization

Abstract

The monosaccharide l-Rhamnose is an important component of bacterial cell walls. The first step in the l-rhamnose biosynthetic pathway is catalysed by glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RmlA), which condenses glucose-1-phosphate (Glu-1-P) with deoxythymidine triphosphate (dTTP) to yield dTDP-d-glucose. In addition to the active site where catalysis of this reaction occurs, RmlA has an allosteric site that is important for its function. Building on previous reports, SAR studies have explored further the allosteric site, leading to the identification of very potent P. aeruginosa RmlA inhibitors. Modification at the C6-NH2 of the inhibitor’s pyrimidinedione core structure was tolerated. X-ray crystallographic analysis of the complexes of P. aeruginosa RmlA with the novel analogues revealed that C6-aminoalkyl substituents can be used to position a modifiable amine just outside the allosteric pocket. This opens up the possibility of linking a siderophore to this class of inhibitor with the goal of enhancing bacterial cell wall permeability.

1. Introduction

The continued global emergence of multi-drug resistant bacteria is a major health concern. The time taken for resistance to new drugs to arise is often rapid and the pace of antibiotic discovery has slowed since the golden era of the 1940–60s.1 The development of novel antimicrobials that avoid the existing mechanisms of resistance and target new pathways is recognised as a high priority for research.

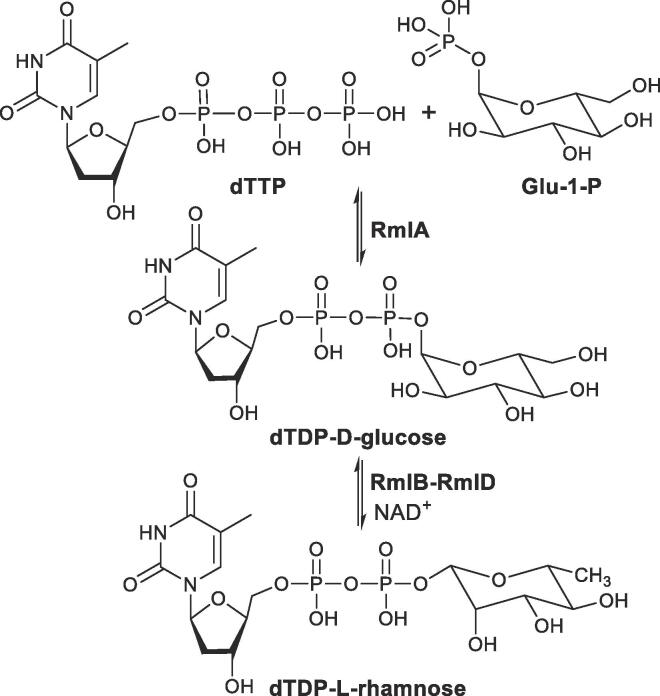

The outer membrane (OM) protects gram-negative bacteria from antibiotic attack and is essential for survival.2 The OM is composed of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) that in many, but not all, bacteria contain l-rhamnose, a C6 sugar unit. For example, in P. aeruginosa l-rhamnose is a component of the LPS and deletion of one of the genes responsible for its biosynthesis results in a bacterium that has much lower virulence in a mouse model.3 In M. tuberculosis the arabinogalactan unit in the cell wall is linked to the peptidoglycan by a disaccharide phosphodiester linker that has a l-rhamnose component (a decaprenyl-diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine rhamnosyl molecule4). The enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of l-rhamnose are therefore potential anti-tuberculosis drug targets.[5], [6] The l-rhamnose biosynthetic pathway involves four enzymes, RmlA-RmlD, which catalyse the conversion of glucose-1-phosphate (Glu-1-P) to the l-rhamnose precursor deoxythymidine diphosphate-l-rhamnose (dTDP-l-rhamnose3, Scheme 1). Since this biosynthetic pathway is not found in eukaryotes, these enzymes are attractive targets for the development of novel selective antibiotics. Small molecule inhibitors of RmlA[7], [8], [9] and RmlC[10], [11] have already been reported.

Scheme 1.

l-Rhamnose biosynthetic pathway involving 4 enzymes which catalyse the conversion of Glu-1-P to dTDP-l-rhamnose.

RmlA, a glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase, is the first enzyme in the pathway and catalyses the condensation of Glu-1-P with deoxythymidine triphosphate (dTTP) to give dTDP-d-glucose (Scheme 1).[3], [12] The inhibition of RmlA by dTDP-l-rhamnose (the final product of the four step reaction sequence) has been reported[3], [13] and it would therefore appear that, in bacteria, RmlA is the point of control for flux through the biosynthetic pathway. RmlA exists as a dimer of dimers and is functional as a tetramer. As a consequence of its structure, the active sites cluster at the dimer-dimer interface and the allosteric (or regulatory) sites cluster at the monomer–monomer interface within each dimer.[3], [14]

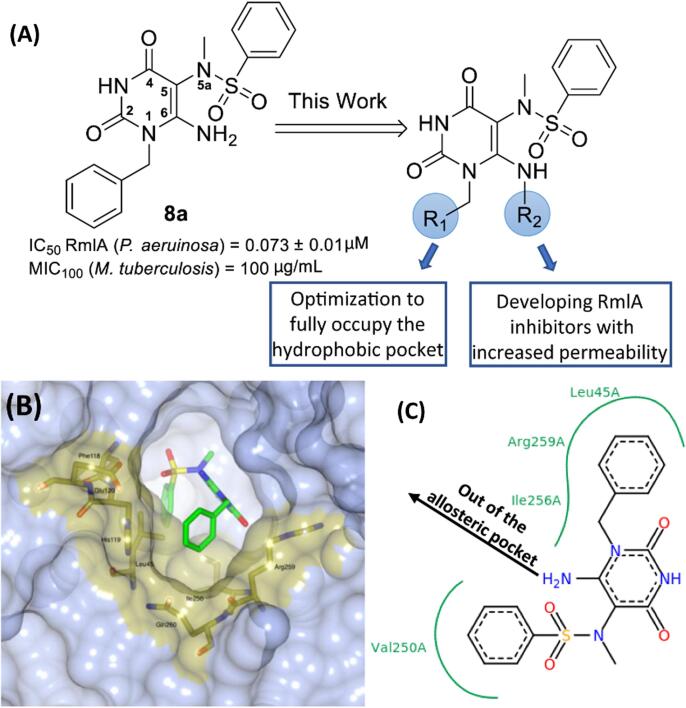

We have previously reported a series of potent novel small molecule allosteric inhibitors of P. aeruginosa RmlA7 (for example Compound 8a in Figure 1A, compound numbering taken from the original report7). In the previous work7, examples of our in vitro RmlA inhibitors were tested for their ability to inhibit the growth of M.tuberculosis (H37Rv) in which RmlA has been shown to be essential.15 Even though sequence alignment of RmlA from P.aeruginosa and M.tuberculosis showed the two proteins are highly conserved, the selected compounds demonstrated only weak activity against M. tuberculosis bacteria (MIC100 values>25 μg/mL). For example, the potent in vitro P.aeruginosa RmlA inhibitor 8a (IC50 = 0.073 ± 0.001 μM7) was shown to have only a weak effect on M. tuberculosis (MIC100 = 100 μg/mL). Apart from off-target effects and minor sequence differences in the RmlA homologues from the two bacteria, another possible reason for the poor effect on live bacteria is the inability of the tested analogues to penetrate the bacterial cells. The cell envelope of mycobacteria, comprised of polysaccharides and lipids, functions as a natural shield that is effective at blocking the entry of small molecules into the protoplasm.[16], [17]

Figure 1.

A. Chemical structure and biological activity of the previously optimized inhibitor 8a. [7] IC50 against the Pseudomonas aeruginosa RmlA protein, MIC100 against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The aims of this work were to modify the N1- and C6-NH2 positions. B. A representation of 8a bound in the allosteric site of RmlA based on our previous X-ray crystallographic analysis of the RmlA-8a complex [PDB 4ASJ]. Residues that make up the N1-substituent sub-pocket are highlighted. C. Schematic representation of pocket interactions between 8a and the enzyme showing that the C6-NH2 in 8a has the tendency to point out of the allosteric pocket into solution.

Re-examination of the RmlA-8a complex [PDB 4ASJ] revealed a hydrophobic pocket that was only partly occupied by the N1-substituent (Figures 1B and 1C). In an initial attempt to explore further the impact of structural changes on the binding of compound 8a, we chose to vary the R1 substituent (Figure 1A). However, the main focus of this report builds on the observation that the C6-NH2 group of 8a points out of the allosteric binding pocket based on our analysis of the RmlA-8a complex (Figure 1C). It was decided to assess whether substitution of one of the NH bonds in the C6-NH2 group with an extended alkyl chain (represented by R2 in Figure 1A) could be tolerated by P. aeruginosa RmlA as this could provide a vector out of the allosteric pocket to an open space whilst retaining the in vitro inhibitory activity of the current series of analogues. If successful this could provide the foundation for the development of a new series of RmlA inhibitors. For example, the attachment of a bacterial cell wall permeabilizer could be achieved via the newly incorporated linker unit at the C6-NH2 position.

2. Results and discussion

Our previous studies focused on structure activity relationship (SAR) analyses involving the sulfonamide and N5a-alkyl substituents in 8a (Figure 1A).18 However, no attempts to optimize the substituent at the N1-position were made. This current study started with examination of the reported structure of the RmlA-8a complex [PDB 4ASJ] and revealed that the N1-substituent pocket was formed from both main- and side-chain atoms of residues Leu45, His119, Glu120, Ile256, Arg259 and Gln260 (Figure 1B). Visual inspection showed that this binding pocket was not ideally filled by the unsubstituted N1- benzyl group in 8a and therefore it was proposed that alternative N1-substituents could improve target binding. A pilot SAR study was performed to explore this hypothesis (see linked Data in Brief report for a detailed discussion). In summary, it was concluded that the key driver in increasing the potency was the presence of a substituent at the 4-position of the N1-benzyl group. It was found that a para-bromobenzyl substituent (compound 1a in Table 1) was optimal (see linked Data in Brief report and PDB codes 5FUH, 5FYE, 5FU0, 5FTS, 5FTV, 5FU8). Consequently, all R2-modified analogues were prepared in the N1-p-bromobenzyl series with one exception (compound 1f, Scheme 2 and Table 1).

Table 1.

Inhibition data against P. aeruginosa RmlA for analogues 1a – 1f.

| Entry | Compd.[a] | R1 | R2 | % Inhibition at 10 μM | IC50 (μM)[b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a | 4-BrC6H4 | H | 100 | 0.034 ± 0.002 |

| 2 | 1b | 4-BrC6H4 | (CH2)3NHCH3 | 100 | 0.860 ± 0.096 |

| 3 | 1c | 4-BrC6H4 | (CH2)2NHCH3 | 0 | – |

| 4 | 1d | 4-BrC6H4 | (CH2)4NH2 | 100 | 0.303 ± 0.026 |

| 5 | 1e | 4-BrC6H4 | (CH2)5NH2 | 100 | 0.316 ± 0.023 |

| 6 | 1f | Ph |  |

100 | 2.470 ± 0.020 |

[a] The following PDB codes are assigned to structures of the complexes of RmlA bound to 1b (6TQG), 1d (6T38), 1f (6T37); [b] SD, standard deviation (n = 3).

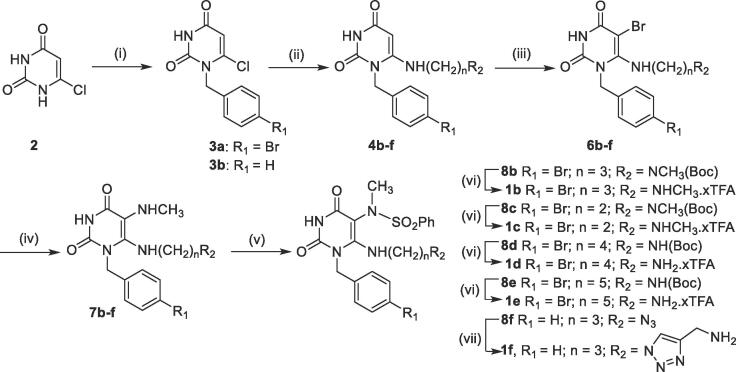

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of C6-NH2 analogues. Reagents and conditions: (i) benzyl chloride or 4-bromo-benzyl chloride, K2CO3, DMSO, 65 °C, 30 min, 3a = 38%, 3b = 45%; (ii) for 4b-4f: required amine (5b: NH2(CH2)3NCH3(Boc); 5c: NH2(CH2)2NCH3(Boc), 5d: NH2(CH2)4NHBoc, 5e: NH2(CH2)5NHBoc, 5f: NH2(CH2)3N3), EtOH, 100 °C, sealed tube, 3 hrs, 4b = 45%, 4c = 45%, 4d = 50%, 4e = 65%, 4f = 78%; (iii) N-Bromosuccinimide, MeOH, 25 °C, 10 min; 6b = 85%; 6c = 85%; 6d = 85%; 6e = 87%; 6f = 61%; (iv) 40% w.w. aq. MeNH2, 70 °C, 1 h; 7b = 56%; 7c = 42%; 7d = 67%; 7e = 80%; 7f = 94%; (v) benzenesulfonyl chloride, pyridine, DCM, 25 °C, 18 hrs; (vi) trifluoroacetic acid, DCM, 25 °C, overnight; 1b = 50%; 1c = 46%; 1d = 48%; 1e = 38%; yields are after two steps (v and vi); (vii) ascorbic acid, CuSO4·5H2O, propargylamine, tBuOH/H2O, 25 °C, 3 hrs, 1f = 10%; the yield is after two steps (v and vii).

The X-ray crystallographic analysis of the RmlA-1a complex (Figure 2, PDB 5FTV) confirmed that in the p-bromobenzyl series, as well as for 8a, substitution at the C6-NH2 position should enable positioning of a modifiable functional group in proximity to the mouth of the allosteric site (Figure S1A). If this could be achieved, not only would the only remaining position available for modification in this inhibitor series have been explored, but future efforts to prepare analogues with enhanced bacterial cell wall permeability would also be facilitated (Figures S1B and S1C). Preliminary molecular modelling studies predicted that the C6-NH2 modified analogue 1b (Table 1 and Scheme 2 for structure) binds in the allosteric site of the enzyme in a similar confirmation to the parent analogue 1a (Figure S2). In addition, the extended C6-aminoalkyl chain was predicted to reach out towards the mouth of the allosteric pocket, as designed. Analogues 1b and 1c with n-propyl and ethyl-containing linkers were therefore synthesised (Scheme 2).

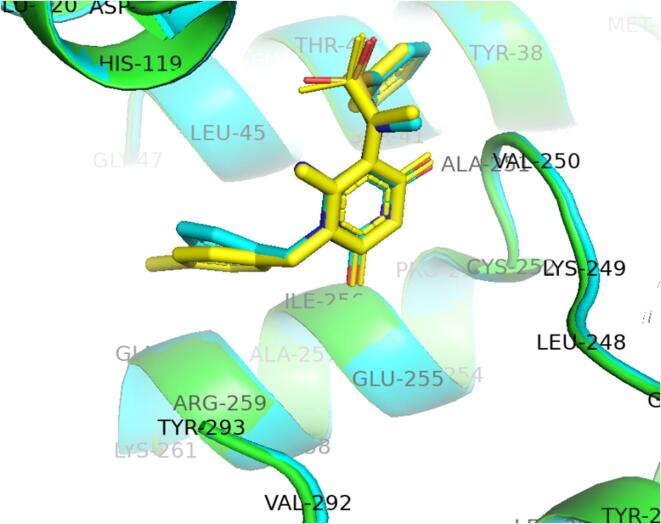

Figure 2.

A representation of the X-ray crystallographic analysis of the RmlA-8a complex (blue, [PDB 4ASJ]) overlaid with the analysis of the RmlA-1a complex (yellow, [PDB 5FTV]). A subtle change in the positioning of the N1-benzyl group resulted from the bromine atom being present in the 4-position of inhibitor 1a.

It was decided to incorporate the extended C6-aminoalkyl chains of 1b and 1c early in the reaction sequence (Scheme 2). Selective N1-alkylation of the starting material 6-chlorouracil (2) with 4-bromo-benzyl chloride under basic conditions enabled isolation of the N1-benzylated product to give 3a.[19], [20] 6-Aminouracils 4b and 4c were then synthesized by reaction of 3a with the corresponding amines 5b (2 × CH2) and 5c (3 × CH2) in moderate yield. The remaining steps – bromination (to give 6b and 6c), addition of methylamine (to give 7b and 7c) and sulfonamide formation were based on our previous report7 (see linked Data in Brief report for additional examples of this reaction sequence) and enabled the successful conversion of 4b and 4c to the N-Boc protected versions (8b and 8c) of the final compounds. Subsequent Boc deprotection of 8b and 8c using TFA gave 1b and 1c respectively as the TFA salts (Scheme 2).

The introduction of the ethyl C6 aminoalkyl chain in 1c led to a complete loss of activity21 against P. aeruginosa RmlA, whereas incorporation of the n-propyl linker in 1b retained activity (IC50 of 0.86 µM, Table 1, entries 2 and 3, see Figures S3 and S4 legends for a discussion on the lack of activity of 1c). X-ray crystallographic analysis of the complex of RmlA with 1b [PDB 6TQG] showed that 1b was bound in the allosteric site of RmlA as expected. Compared with the C6-NH2 unsubstituted analogue 1a (Table 1, entry 1), most of the ligand–protein interactions were retained in the RmlA-1b complex (Figure S5), however, some differences were observed. For example, whereas the C6-NH2 group in 1a showed hydrogen bonding to the protein backbone (Gly115 and His119) through the interaction with two different molecules of water, 1b retained the interaction with Gly115 but lost the water-mediated hydrogen bond to His119 (as expected, Figure S3). Consistent with the docking studies, the extended aminoalkyl chain in 1b pointed out of the allosteric pocket and the distance between the nitrogen of the newly introduced terminal methylamine in 1b to the C-terminal Tyr293 residue was 3.8 Å. The terminal NH in 1b interacted with a network of water molecules ultimately linking to the C-terminal Tyr293 (Figure S3).

Based on the initial success with 1b being a sub-micromolar inhibitor of P. aeruginosa RmlA, it was decided to extend the length of the linker unit from n-propyl in 1b to n-butyl in 1d and n-pentyl in 1e (Scheme 2) in an attempt to position the terminus of the C6-aminoalkyl chain outside the allosteric pocket. In the case of 1d and 1e, a primary amine was incorporated at the end of the chain (see Figure S5 legend for more discussions). There was a risk that the more extended and flexible alkyl chains in 1d and 1e may undergo hydrophobic collapse. Therefore a heteroaromatic ring was incorporated into the linker unit in an attempt to minimse the chances of this occurring. The triazole-containing compound 1f was therefore synthesized (Scheme 2). In the case of 1f, the para-Br in the N1-benzyl moiety was also removed to provide additional room for the triazole group in 1f to adjust its position in the allosteric site. The synthesis of the additional analogues 1d and 1e was achieved in an analogous manner to the synthesis of 1b and 1c (Scheme 2). The synthesis of 1f required incorporation of an azide functional group at the terminus of the C6-linker unit through formation of 4f (n = 3, R2 = N3, Scheme 2). The azide group was compatible with the subsequent steps enabling 4f to be successfully converted to 8f. The copper-catalysed azide-alkyne click (CuAAC) reaction of 8f with propargylamine gave 1f although the unoptimized yields over the final two steps in the sequence were low (Scheme 2). If analogue 1f was found to retain activity against P.aeruginosa RmlA, future work should enable the relatively easy incorporation of a bacterial cell wall permeabilizer using this CuAAC approach.

The increased length of the linker chain in analogues 1d and 1e compared to 1b led to around a 2.5-fold increase in potency with 1d and 1e having IC50 values of 0.303 ± 0.026 μM and 0.316 ± 0.023 μM respectively (Table 1, entries 4 and 5 vs. entry 2). The structure of the RmlA-1d complex [PDB 6 T38] confirmed that instead of interacting with any protein residues, the terminal amine of the C6-aminoalkyl chain in 1d was positioned out of the pocket, approximately equidistant between His119 and Tyr293 (Figures 3A and 3B).

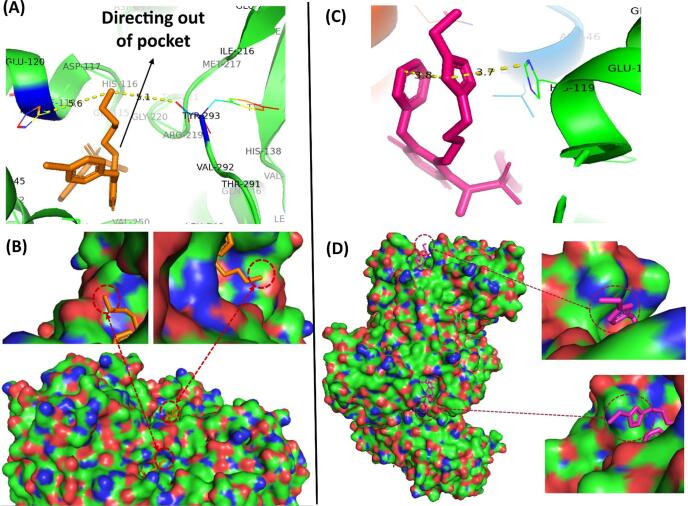

Figure 3.

A. Representation of X-ray crystallographic analysis of the RmlA-1d complex [PDB 6T38] showing that the terminal amine of the C6-aminoalkyl chain in 1d has moved out of the pocket and C6-aminoalkyl chain in 1d was situated halfway between His119 and Tyr293. B. The surface representation of the complex of RmlA with 1d revealed that the terminal amine in the aminoalkyl chain at the C6-NH position of 1d had moved out into open space. C. Representation of X-ray crystallographic analysis of the RmlA-1f complex [PDB 6T37] showing that the triazole moiety of 1f stacks between the imidazole ring of His119 in RmlA and the N1-benzyl group and the terminal amine in the aminoalkyl chain at the C6-NH position of 1f was positioned in open space outside the allosteric pocket. D. The surface representation of the complex of RmlA with 1f revealed that the terminal NH2 of 1f is out in the open.

Whilst there was a notable decrease in the potency of the triazole-containing analogue 1f in the RmlA inhibition assay compared to 1c, 1d and 1e (Table 1, entry 6 vs. entries 2, 4 and 5), 1f was still able to inhibit P.aeruginosa RmlA. The structure of the RmlA-1f complex [PDB 6 T37] revealed that the triazole moiety of 1f stacks between the imidazole ring of His119 and its own benzyl group in the N1 position forming an unusual sandwich structure in which the extended C6 chain in 1f is stabilized (Figure 3C). The terminal NH2 in 1f does not appear to interact with any protein residues and extends out of the pocket (Figure 3D and Figure S6). Superposition of the structures of the RmlA-8a with RmlA-1f complexes (Figure S7) revealed that the introduction of the triazole moiety in 1f forces the repositioning of its N1- benzyl group. Compared to the situation with 8a, the N1- benzyl group in 1f is positioned much closer to Arg 259 and Glu 255 which form the backbone of the hydrophobic pocket. This may be one factor in explaining the observed drop in potency associated with 1f.

The physicochemical properties (Table S1) of this series of new compounds in terms of Ligand Efficiency (LE, ranging from 0.21 to 0.37) and Lipophilic Ligand Efficiency (LLE, ranging from 3.9 to 5.2) showed high drug-likeness22, while the CLogP values (ranging from 1.14 − 2.77) are relatively higher than those of therapeutic antibacterial agents, which mostly cluster near 0.23 To address the possible low permeability of these compounds (due to their relative high lipophilicity), a “trojan horse strategy”24 could be considered. Due to the poor solubility of Fe3+ salts, most microorganisms cannot use them directly. A siderophore is an iron chelator secreted by bacteria. Having chelated Fe3+, the siderophore is recognised by a specific outer membrane receptor and then transported to the bacterial cytoplasm. In this way the bacteria can take in iron as an essential nutrient required to survive.25 Similarly, synthesised siderophore-antibiotic conjugates[26], [27], [28] can be recognised by bacteria and transported into the cell. As soon as the conjugates are transported into the cell, the antibiotic, if the siderophore-antibiotic linkage is designed correctly, can be released to kill the bacteria. Many studies have shown that synthetic siderophore-drug conjugates can act as novel antimicrobial agents and can help treat disease caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria. The terminal amine of 1d and 1f could provide a possible site to attach a siderophore, laying the foundation to prepare bacterial cell wall penetrating RmlA inhibitors. In addition, the presence of the more basic amine functionalities in these novel compounds may impact on activity against both gram positive and gram negative bacteria (the eNTRy rules[29], [30]).

3. Conclusions

A significant extension of our previous studies7 on the inhibition of P. aeruginosa RmlA, the first enzyme in the l-rhamnose biosynthetic pathway, by pyrimidinedione-based compounds is reported. A pilot SAR study involving modifications at the N1 position of the heterocyclic core led to the identification of a number of potent inhibitors of P. aeruginosa RmlA including the p-bromo-benzyl substituted analogue 1a. Subsequent modification at the C6-NH2 position showed that different linker lengths at this position were tolerated. Throughout these studies detailed analysis of the binding modes of the compounds has been possible by X-ray crystallographic analysis of a large number of RmlA-inhibitor complexes. One highlight from this structural study is the demonstration that for inhibitors 1d and 1f the terminus of the newly incorporated linker unit sits outside the allosteric binding pocket. This provides a real opportunity, in future work, to attach a siderophore to the end of the linker unit with the goal of potentially increasing the bacterial cell wall permeability of this class of inhibitors through the ability of the siderophore to be sequestered by the bacterium.31

4. Experimental section

4.1. Synthesis of analogues

All intermediates and final compounds were prepared according to the protocols supplied in the Supporting Information and Data in Brief. Examples of the synthesis of 1d (intermediates and final compound) and the synthesis of 1b, 1c, 1e and 1f (final compounds) are shown below.

4.2. 1-Benzyl-6-chloropyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione (3a)

A mixture of 6-chlorouracil 2 (5.0 g, 34.2 mmol, 1.0 eq.), 4-bromobenzyl chloride (10.5 g, 51.3 mmol, 1.5 eq.), and K2CO3 (2.3 g, 17.1 mmol, 0.5 eq.) in DMSO (100.0 mL, 3.0 mL/mmol) was stirred at 65 °C for 30 min. 10 % aqueous solution of NaOH (100.0 mL, 3.0 mL/mmol) was added to the hot reaction mixture with stirring. The reaction mixture was washed with ethyl acetate (100.0 mL, 3.0 mL/mmol), and the aqueous phase was acidified with conc. aqueous HCl to pH = 2. The resulting aqueous mixture was kept in a refrigerator, and the resulting precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with water (60.0 mL, 2.0 mL/mmol), and dried. 3a was obtained as a white solid (4.4 g, 13.9 mmol, 38 %). Mp. 183–187 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 11.77 (1H, s, NH), 7.57 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H3′, H5′), 7.25 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H2′, H6′), 6.02 (1H, s, H5), 5.12 (2H, s, CH2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 161.5 (C4), 151.0 (C2), 147.1 (C6), 136.2 (C1′), 132.0 (C3′ and C5′), 129.3 (C2′ and C6′), 121.0 (C4′), 103.0 (C5), 48.1 (NCH2). HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C11H979BrClN2O2. [M + H]+: 314.9536; found: 314.9537.

4.3. Tert-butyl (4-((3-(4-bromobenzyl)-2,6-dioxo-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrimidin-4-yl) amino)butyl)carbamate (4d)

To a stirred solution of 1-benzyl-6-chloruracil 3a (4.0 g, 12.7 mmol, 1.0 eq.) in ethanol (38.0 mL, 3.0 mL/mmol), tert-butyl (4-aminobutyl) carbamate 5d (4.8 g, 25.4 mmol, 2.0 eq.) was added. The resulting yellow solution was stirred at 100 °C in a sealed tube for 3 h. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo, and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (50% EtOAc in petroleum ether). 4d was obtained as a yellow solid (3.0 g, 6.3 mmol, 50 %). Mp. 286–288 °C. νmax cm−1 3342 (N—H), 2983 (C—H), 2871 (C—H), 1705 (C O), 1665 (C O), 1605 (N—H), 1530 (N—H), 1447 (C C), 1387 (N—C), 1163 (C—C(=O)-O), 777 (Ar C—H), 669 (C-Br). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.05 (1H, s, H3), 7.44 (2H, d, J = 7.9 Hz, H3′ and H5′), 7.13 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2′ and H6′), 5.59 (1H, s, H1′’), 5.17 (2H, s, NCH2), 4.86 (1H, s, H6′’), 4.76 (1H, s, H5), 3.02 (2H, t, J = 6.0 Hz, H2′’), 2.95 (2H, t, J = 6.0 Hz, H5′’), 1.57 – 1.46 (m, 2H, H4′’), 1.43 (s, 9H, 3 × CH3), 1.34 – 1.28 (m, 2H, H3′’). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.1 (C4), 156.5 (O-C O), 154.7 (C2), 151.6 (C6), 134.4 (C1′), 132.1 (C3′ and C5′), 128.2 (C2′ and C6′), 121.8 (C4′), 79.5 (O—C), 75.5 (C5), 43.9 (NCH2), 43.3 (C2′’), 39.6 (C5′’), 28.4 (3 × CH3), 27.8 (C3′’), 24.4 (C4′’). HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C20H2879BrN4O4. [M + H]+:467.1288; found: 467.1285.

4.4. Tert-butyl (4-((5-bromo-3-(4-bromobenzyl)-2,6-dioxo-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrimidin-4-ylamino)butyl)carbamate (6d)

N-Bromosuccinimide (500.0 mg, 2.7 mmol, 1.1 eq.) was added portion-wise to a suspension of 1-benzyl-6-aminouracil 4d (1.2 g, 2.6 mmol, 1.0 eq.) in anhydrous MeOH (13.0 mL, 5.0 mL/mmol) at 0 °C. The resulting yellow solution was stirred at ambient temperature for 10 mins under nitrogen. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (20% EtOAc in petroleum ether). 6d was obtained as a yellow solid (1.2 g, 2.2 mmol, 85%). Mp. 283–286 °C. 3227 (N—H), 2980 (C—H), 1746 (C O), 1665 (C C), 1674 (C O), 1643 (N—H), 1379 (C—N), 1365 (C—H), 1302 (C—N), 1165 (C—O), 754 (Ar C—H), 636 (C-Br). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.65 (1H, s, H3), 7.55 – 7.47 (2H, m, H3′ and H5′), 7.17 – 7.12 (2H, m, H2′ and H6′), 5.13 (2H, s, NCH2), 4.64 (1H, brs, H1′’), 4.44 (1H, s, H6′’), 3.24 (2H ,t, J = 6.7 Hz, H5′’), 3.10 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, H2′’), 1.63 – 1.51 (2H, m, H4′’), 1.46–1.43 (11H, m, H3′’ and 3 × CH3). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ159.1 (C4), 156.1 (O-C O), 154.6 (C2), 150.7 (C6), 134.5 (C1′), 132.2 (C3′ and C5′), 128.3 (C2′ and C6′), 122.1 (C4′), 81.5 (O—C), 79.6 (C5), 48.4 (NCH2), 47.7 (C5′’), 39.7 (C2′’), 28.4 (3 × CH3), 27.8 (C4′’), 27.3 (C3′’). HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C20H2779Br2N4O4. [M + H]+: 545.0394; found: 545.0389.

4.5. Tert-butyl (4-((3-(4-bromobenzyl)-5-(methylamino)-2,6-dioxo-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrimidin-4-yl)amino)butyl)carbamate (7d)

The brominated intermediate 6d (500.0 mg, 0.9 mmol) was suspended in a 40% aqueous solution of methylamine (0.5 mL, 0.5 mL/mmol). The suspension was heated to 70 °C and stirred for 1 h. The reaction was then cooled to rt. and the mixture was diluted and extracted with DCM three times (5.0 mL × 3, 5.0 mL/mmol × 3). The combined organic phases were washed with saturated aqueous NaCl (5.0 mL, 5.0 mL/mmol), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (50% acetone in petroleum ether with 1% Et3N). 7d was obtained as a yellow solid (300.0 mg, 0.6 mmol, 67%). Mp. 203–205 °C. νmax cm−1 3333 (N—H), 2928 (C—H), 1678 (C O), 1661 (C O), 1526 (N—H), 1487 (C C), 1400 (C—N), 1161 (C—C(=O)-O), 712 (Ar C—H), 575 (C-Br). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.69 (1H, s, H3), 7.53 – 7.47 (2H, m, H3′ and H5′), 7.14 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H2′ and H6′), 5.07 (2H, s, NCH2), 4.93 (1H, t, J = 6.2 Hz, H1′’), 4.62 (1H, s, H6′’), 3.17 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, H5′’), 3.08 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, H2′’), 2.51 (3H, s, N5aCH3), 1.60 – 1.49 (2H, m, H4′’), 1.46 (9H ,s, 3 × CH3), 1.20 – 1.09 (2H, m, H3′’). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.7 (C4), 156.0 (O-C O), 150.6 (C2 and C6), 135.0 (C1′), 132.1 (C3′ and C5′), 128.1 (C2′ and C6′), 121.8 (C4′), 106.7 (C5), 79.4 (O—C), 47.4 (NCH2), 46.2 (C5′’), 39.9 (C2′’), 36.5 (N5aCH3), 29.7 (C3′’), 28.4 (3 × CH3), 27.7 (C4′’). HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C21H3179BrN5O4 [M + H]+: 496.1550; found: 496.1554.

4.6. N-(6-((4-aminobutyl)amino)-1-(4-bromobenzyl)-2,4-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidin-5-yl)-N-methylbenzenesulfonamide (1d)

To a stirred solution of the amine 7d (150.0 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.0 eq.) in dry DCM (2.0 mL, 7.0 mL/mmol) was added pyridine (0.1 mL, 1.5 mmol, 5.0 eq.) followed by sulfonyl chloride (80.0 mg, 0.5 mmol, 1.5 eq.). The resulting yellow solution was stirred at rt for 18 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo and water (2.0 mL, 7.0 mL/mmol) was added to the residue followed by 1 M HCl to reach acidic pH to get the crude of 8d. To a solution of 8d in DCM (1.5 mL, 5.0 mL/mmol) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.3 mL, 1.0 mL/mmol). The solution was allowed to stir at room temperature overnight. The mixture was basified with ammonia solution (1.0 mL, 3.0 mL/mmol) and was extracted with DCM three times (5.0 mL × 3, 15.0 mL/mmol). The combined organic phases were washed with saturated aqueous NaCl (5.0 mL,15.0 mL/mmol), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (50% acetone in petroleum ether with 1% Et3N). 1d was obtained as a yellow solid (77.6 mg, 0.1 mmol, 48 %). Mp. 311–313 °C. νmax cm−1 3382 (N—H), 2961 (C—H), 2922 (C—H), 1651 (C O), 1570 (N—H), 1541 (N—H), 1447 (C C), 1328 (C—N), 1259 (S O), 796 (Ar C—H), 597 (C-Br). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.86 – 7.80 (2H, m, H3′ and H5′), 7.60 – 7.53 (1H, m, H4′’’), 7.55 – 7.45 (4H, m, H2′’’, H3′’’, H5′’’ and H6′’’), 7.18 – 7.13 (2H, m, H2′ and H6′), 5.23 (1H, d, J = 16.9 Hz, NCH2), 5.04 (1H, d, J = 16.9 Hz,NCH2), 3.75 – 3.61 (1H, m, H2′’), 3.24 – 3.17 (1H, m, H2′’), 3.18 (3H, s, NCH3), 2.74 – 2.62 (2H, m, H5′’), 1.69 – 1.59 (1H, m, H3′’), 1.58–1.50 (1H, m, H3′’), 1.47 – 1.39 (2H, m, H4′’). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.1 (C4), 156.1 (C2), 150.5 (C6), 138.4 (C1′’’), 134.5 (C1′), 132.9 (C4′’’), 132.2 (C3′ and C5′), 128.6 (C2′, C6′), 128.0 (C3′’’, C5′’’), 127.9 (C2′’’ and C6′’’), 121.9 (C4′), 95.4 (C5), 46.5 (NCH2), 46.4 (C2′’), 40.7 (C5′’), 38.1 (NCH3), 29.8 (C4′’), 27.2 (C3′’). HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C22H2779BrN5O4S. [M + H]+: 536.0962; found: 550.0958.

4.7. N-(1-(4-bromobenzyl)-6-((3-(methylamino) propyl) amino)-2,4-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidin-5 -yl)-N-methylbenzenesulfonamide (1b)

To a stirred solution of the amine 7b (150.0 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.0 eq.) in dry DCM (2.0 mL, 7.0 mL/mmol) was added pyridine (0.1 mL, 1.5 mmol, 5.0 eq.) followed by sulfonyl chloride (80.0 mg, 0.5 mmol, 1.5 eq.). The resulting yellow solution was stirred at rt for 18 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo and water (2.0 mL, 7.0 mL/mmol) was added to the residue followed by 1 M HCl to reach acidic pH to get the crude of 8d. To a solution of 8d in DCM (1.5 mL, 5.0 mL/mmol) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.3 mL, 1.0 mL/mmol). The solution was allowed to stir at room temperature overnight. The mixture was basified with ammonia solution (1.0 mL, 3.0 mL/mmol) and was extracted with DCM three times (5.0 mL × 3, 15.0 mL/mmol). The combined organic phases were washed with saturated aqueous NaCl (5.0 mL,15.0 mL/mmol), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (50% acetone in petroleum ether with 1% Et3N). 1b was obtained as a yellow solid (81.0 mg, 0.2 mmol, 50 %). Mp. 294–297 °C. νmax cm−1 3362 (N—H), 3292 (N—H), 3120 (C—H), 1709 (C O), 1603 (C O), 1550 (N—H), 1502 (C C), 1173 (C—N), 750 (Ar C—H), 672 (C-Br). 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.85 – 7.79 (m, 2H, H3′ and H5′), 7.68 – 7.60 (m, 1H, H4′’), 7.63 – 7.51 (m, 4H, H2′’’, H6′’’, H5′’’and H3′’’), 7.23 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H, H2′ and H6′), 5.34–5.22 (m, 2H, NCH2), 3.78 (dt, J = 13.5, 6.8 Hz, 1H, H2′’), 3.48 (dt, J = 13.4, 6.8 Hz, 1H, H2′’), 3.21 (s, 3H, N4′’aCH3), 2.65 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, H4′’), 2.49 (s, 3H, N5aCH3), 1.87 – 1.77 (m, 2H, H3′’). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 161.6 (C4), 154.9 (C2), 150.6 (C6), 138.7 (C1′’’), 135.0 (C1′), 132.6 (C4′’’), 131.7 (C3′ and C5′), 128.4 (C2′, C6′), 127.8 (C3′’’, C5′’’), 127.7 (C2′’’, C6′’’), 120.8 (C4′), 94.5 (C5), 47.9 (C4′’), 44.5 (NCH2), 42.8 (C2′’), 37.3 (N4′’aCH3), 33.3 (N5aCH3), 26.5 (C3′’). HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C22H2779BrN5O4S. [M + H]+: 536.0962; found: 536.0958.

4.8. N-(1-(4-bromobenzyl)-6-((2-(methylamino)ethyl)amino)-2,4-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidin-5-yl)-N-methylbenzenesulfonamide (1c)

To a stirred solution of the amine 7c (100.0 mg, 0.2 mmol, 1.0 eq.) in dry DCM (2.0 mL, 7.0 mL/mmol) was added pyridine (0.1 mL, 1.0 mmol, 5.0 eq.) followed by sulfonyl chloride (53.0 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.5 eq.). The resulting yellow solution was stirred at rt for 18 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo and water (1.5 mL, 7.0 mL/mmol) was added to the residue followed by 1 M HCl to reach acidic pH to get the crude of 8c. To a solution of 8c in DCM (1.0 mL, 5.0 mL/mmol) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.2 mL, 1.0 mL/mmol). The solution was allowed to stir at room temperature overnight. The mixture was basified with ammonia solution (0.6 mL, 3.0 mL/mmol) and was extracted with DCM three times (5.0 mL × 3). The combined organic phases were washed with saturated aqueous NaCl (3.0 mL,15.0 mL/mmol), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (50% acetone in petroleum ether with 1% Et3N). 1c was obtained as a yellow solid (51.0 mg, 0.1 mmol, 46%) via 8c. Mp. 283–286 °C. νmax cm−1 3501 (N—H), 2962 (C—H), 2926 (C—H), 1645 (C O), 1573 (N—H), 1533(N—H), 1471 (C C), 1444 (C—H), 1411 (C—N), 1257 (S O), 1230 (C—N), 867 (Ar C—H), 684 (C-Br). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.96 (s, 1H, H3), 7.81 – 7.70 (m, 2H, H3′), 7.71–7.64 (m, 1H, H4′’’), 7.67 – 7.46 (m, 4H, H2′’’, H3′’’, H5′’’ and H6′’’), 7.19 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H, H2′), 6.50 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, H6a), 5.22–5.14 (m, 2H, NCH2), 3.56 (m, 2H, H2′’), 3.10 (s, 3H, N3′’aCH3), 3.05 (dt, J = 13.9, 7.0 Hz, 1H, H2′’), 2.85 (dt, J = 13.5, 6.9 Hz, 1H, H2′’), 2.59 (s, 3H, N5aCH3). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 160.7 (C4), 154.4 (C2), 150.5 (C6), 139.1 (C1′’’), 136.8 (C1′), 133.6 (C4′’’), 131.8 (C3′ and C5′), 130.0 (C2′, C6′), 129.2 (C3′’’ and C5′’’), 128.8 (C2′’’ and C6′’’), 127.4 (C4′), 94.3 (C5), 49.2 (C2′’), 44.6 (NCH2), 42.8 (C3′’), 37.9 (N3′’aCH3), 35.6 (N5aCH3). HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C21H2579BrN5O4S. [M + H]+: 522.0611; found: 522.0622.

4.9. N-(6-((5-aminopentyl)amino)-1-(4-bromobenzyl)-2,4-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidin-5-yl)-N-methylbenzenesulfonamide (1e)

To a stirred solution of the amine 7e (150.0 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.0 eq.) in dry DCM (2.0 mL, 7.0 mL/mmol) was added pyridine (0.1 mL, 1.5 mmol, 5.0 eq.) followed by sulfonyl chloride (80.0 mg, 0.5 mmol, 1.5 eq.). The resulting yellow solution was stirred at rt for 18 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo and water (2.0 mL, 7.0 mL/mmol) was added to the residue followed by 1 M HCl to reach acidic pH to get the crude of 8e. To a solution of 8e in DCM (1.5 mL, 5.0 mL/mmol) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.3 mL, 1.0 mL/mmol). The solution was allowed to stir at room temperature overnight. The mixture was basified with ammonia solution (0.9 mL, 3.0 mL/mmol) and was extracted with DCM three times (5.0 mL × 3). The combined organic phases were washed with saturated aqueous NaCl (4.5 mL,15.0 mL/mmol), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (50% acetone in petroleum ether with 1% Et3N). 1e was obtained as a yellow solid (58.2 mg, 0.1 mmol, 36%) via 8e. Mp. 317–319 °C. νmax cm−1 3382 (N—H), 2941 (C—H), 1657 (C O), 1565 (N—H), 1535 (N—H), 1455 (C C), 1320 (C—N), 1265 (S O), 790 (Ar C—H), 603 (C-Br). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.86 – 7.80 (2H, m, H3′ and H5′), 7.62 – 7.55 (1H, m, H4′’’), 7.58 – 7.52 (2H, m, H2′’’ and H6′’’), 7.55 – 7.46 (2H, m, H3′’’ and H5′’’), 7.21 – 7.15 (2H, m, H2′ and H6′), 5.25 (1H, d, J = 16.6 Hz, NCH2), 5.00 (1H, d, J = 16.6 Hz, NCH2), 4.80 (1H, s, H1′’’), 3.54 (1H, dt, J = 13.2 Hz, 7.1 Hz, H2′’’), 3.43 (2H, s, H7′’), 3.25 – 3.18 (1H, m, H2′’’), 3.17 (3H, s, NCH3), 2.67 (2H, dt, J = 13.7 Hz, 7.1 Hz, H6′’), 1.54–1.44 (2H, m, H3′’), 1.43 – 1.36 (2H, m, H5′’), 1.28–1.23 (2H, m, H4′’). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 159.6 (C4), 156.5 (C2), 150.5 (C6), 138.1 (C1′’’), 134.2 (C1′), 133.0 (C4′’’), 132.4 (C3′ and C5′), 128.7 (C2′ and C6′), 128.1 (C3′’’ and C5′’’), 128.0 (C2′’’ and C6′’’), 122.3 (C4′), 96.5 (C5), 47.2 (NCH2), 46.4 (C2′’), 41.6 (C6′’), 37.9 (NCH3), 32.5 (C5′’), 30.0 (C3′’), 23.7 (C4′’). HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C23H2979BrN5O4S. [M + H]+: 550.1118; found: 550.1114.

4.10. N-(6-((3-azidopropyl)amino)-1-benzyl-2,4-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidin-5-yl)-N-methyl

Benzenesulfonamide (1f)

To a stirred solution of the amine 7f (150.0 mg, 0.4 mmol, 1.0 eq.) in dry DCM (1.0 mL) was added pyridine (0.1 mL, 2.0 mmol, 5.0 eq.) followed by sulfonyl chloride (104.0 mg, 0.6 mmol, 1.5 eq.). The resulting yellow solution was stirred at rt for 18 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo. To a solution of the crude in tBuOH / H2O (1:1, 2.0 mL) was added ascorbic acid (14.0 mg, 0.1 mmol, 0.2 eq.), CuSO4·5H2O (12.0 mg, 0.1 mmol, 0.2 eq.) and propargylamine (24.0 mg, 0.4 mmol, 1.1 eq.). The reaction mixture was stirred at rt. for 1 h, then quenched by addition of NH4Cl and extracted with EtOAc (5 mL × 3). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried with MgSO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatograpy (5% methanol in DCM). 1f was obtained as a yellow solid (21.0 mg, 0.04 mmol, 10%). Mp. 295–297 °C. νmax: 3296 (N—H), 3159 (N—H), 2963 (C—H), 1699 (C O), 1645 (C O), 1574 (N—H), 1445 (C C), 1259 (S O), 1087 (C—N), 746 (Ar C—H) cm−1. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.83 – 7.75 (3H, m, H2′’’, H6′’’ and H5′’’’), 7.66 – 7.59 (1H, m, H4′’’), 7.53 (2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, H3′’’ and H5′’’), 7.40 (2H, t, J = 7.7 Hz, H2′ and H6′), 7.33 – 7.27 (3H, m, H3′, H4′ and H5′), 5.49 (1H, d, J = 17.2 Hz, NCH2), 5.16 (1H, d, J = 17.3 Hz, NCH2), 4.11 (1H, dt, J = 13.3, 6.5 Hz, H4′’), 4.03 (1H, dt, J = 13.8, 6.8 Hz, H4′’), 3.99 (2H, s, H1′’’’’), 3.65 – 3.59 (1H, m, H2′’), 3.35 – 3.30 (1H, m, H2′’), 3.09 (3H, s, NCH3), 2.06 (1H, dt, J = 13.8, 6.9 Hz, H3′’), 1.99 (1H, dt, J = 14.1, 7.0 Hz, H3′’). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CD3OD) 13C NMR (126 MHz, CD3OD) δ 161.3 (C4), 155.0 (C2), 150.8 (C6), 145.8 (C4′’’’), 138.8 (C1′’’), 135.6 (C1′), 132.6 (C2′’’ and C6′’’), 128.8 (C4′’’), 128.4 (C2′ and C6′), 127.8 (C3′’’ and C5′’’), 127.5 (C4′), 125.7 (C3′ and C5′), 122.9 (C5′’’’), 94.3 (C5), 46.9 (C4′’), 46.27, 44.9 (NCH2), 42.1 (C2′’), 37.1 (NCH3), 29.60 (C3′’). HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C24H29N8O4S. [M + H]+: 525.2027; found: 525.2022.

4.11. Cloning, expression and purification

P. aeruginosa RmlA was cloned, expressed and purified based on protocols previously reported.32

4.12. In vitro biological assays

Each assay was performed in a 101 μL reaction volume containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.1 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), 0.05% NP-40, 15 nM recombinant RmlA, 0.8 μg/ml pyrophosphatase, 5 μM dTTP and 5 μM G-1-P. The inhibitor was added to the plate (20 μL) followed by RmlA (30 μL). The reaction was initiated with the addition of dTTP (25 μL), G-1-P (25 μL) and pyrophosphatase (1 μL) as a mixture in one charge (51 μL total) and the assay was allowed to run for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was quenched by addition of BIOMOL™ Green reagent (100 μL) and was allowed to develop before the absorbance of each well was measured at 620 nm.

4.13. Protein Crystallization, co-Crystallization and soaking

Crystals were grown by the sitting drop vapour diffusion method as previously described.7 Drops contained 1 μL of protein (10 mg mL- 1 mixed with 1 μL precipitant (4–12% PEG 6000, 0.1–0.15 M MES pH 6.0, 0.05–0.1 M MgCl2, 0.1–0.15 M NaBr, 1% β-mercaptoethanol). Crystals grew overnight to dimensions of 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.1 mm. Complexes of RmlA with inhibitor were prepared by soaking or co-crystallization. For soaking, solid compound was added to drops containing crystals and allowed to incubate for between 2 and 24 h prior to data collection. For co-crystallization, solid compound was incubated with protein in solution for 1 h prior to setting up sitting drops.

4.14. Data collection

Data were collected at the Diamond Light Source synchrotron or in-house using a Rigaku MicroMax 007HFM x-ray generator. Data were processed with iMOSFLM33 or XIA234 incorporating XDS35. Each structure was solved using MOLREP36 with 4ASJ7 as the search model with the inhibitor removed. REFMAC37 was used to refine the models with model building in COOT38 and ligands built with PRODRG39. Structural figures were prepared using Pymol40 and CCP4MG41.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from The Scottish Universities Life Science Alliance (L.P., Ph.D. studentship), a China Scholarship Council-University of St Andrews PhD Fellowship (GX). JHN is funded by the Wellcome Trust (100209/Z/12/Z). We would like that thank Dr Christopher Lancefield for helpful discussions.

The coordinates of the RmlA complexes have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (pdb codes 5FUH, 5FYE, 5FU0, 5FTS, 5FTV, 5FU8, 6TQG, 6T38, 6T37).

Raw data files can be found at DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.16657876.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116477.

Contributor Information

James H. Naismith, Email: james.naismith@strubi.ox.ac.uk.

Nicholas J. Westwood, Email: njw3@st-andrews.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lewis K. Platforms for antibiotic discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:371–387. doi: 10.1038/nrd3975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwechheimer C., Kuehn M.J. Outer-membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria: biogenesis and functions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:605–619. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blankenfeldt W., Asuncion M., Lam J.S., Naismith J.H. The structural basis of the catalytic mechanism and regulation of glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RmlA) EMBO J. 2000;19:6652–6663. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vilchèze C. Mycobacterial Cell Wall: A Source of Successful Targets for Old and New Drugs. Appl Sci. 2020;10:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNeil M., Brennan P. Structure function and biogenesis of the cell envelope of mycobacteria in relation to bacterial physiology, pathogenesis and drug resistance; some thoughts and possibilities arising from recent structural information. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:451–463. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90120-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucas R, Balbuena P. Errey JC, Squire MA, Gurcha SS, McNeil M, Besra GS, Davis BG. Glycomimetic inhibitors of mycobacterial glycosyltransferases: targeting the TB cell wall. ChemBioChem 2008; 9; 2197-2199. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Alphey M.S., Pirrie L., Torrie L.S., et al. Allosteric competitive inhibitors of the glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RmlA) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;8:387–396. doi: 10.1021/cb300426u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loranger M.W., Forget S.M., McCormick N.E., Syvitski R.T., Jakeman D.L. Synthesis and evaluation of L-rhamnose 1C-phosphonates as nucleotidylyltransferase inhibitors. J Org Chem. 2013;78:9822–9833. doi: 10.1021/jo401542s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loranger M.W. Dalhousie University; 2013. The Design and Synthesis of Phosphonate-based Inhibitors of Nucleotidylyltransferases. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivendran S., Jones V., Sun D., et al. Identification of triazinoindol-benzimidazolones as nanomolar inhibitors of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis enzyme TDP-6-deoxy-D-xylo-4-hexopyranosid-4-ulose 3, 5-epimerase (RmlC) Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:896–908. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harathi N., Pulaganti M., Anuradha C.M., Kumar C.S. Inhibition of mycobacterium-RmlA by molecular modeling, dynamics simulation, and docking. Adv Bioinform. 2016:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2016/9841250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sivaraman J., Sauvé V., Matte A., Cygler M. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RffH) complexed with dTTP and Mg2+ J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44214–44219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuccotti S., Zanardi D., Rosano C., Sturla L., Tonetti M., Bolognesi M. Kinetic and crystallographic analyses support a sequential-ordered bi bi catalytic mechanism for Escherichia coli glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:831–843. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton W.A., Lesniak J., Biggins J.B., et al. Structure, mechanism and engineering of a nucleotidylyltransferase as a first step toward glycorandomization. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2001;8:545. doi: 10.1038/88618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qu H., Xin Y., Dong X., Ma Y. An rmlA gene encoding d-glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase is essential for mycobacterial growth. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;275:237–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan P.J. Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2003;83:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camacho L.R., Constant P., Raynaud C., et al. Analysis of the phthiocerol dimycocerosate locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19845–19854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panovic I., Montgomery J.R., Lancefield C.S., Puri D., Lebl T., Westwood N.J. Grafting of technical lignins through regioselective triazole formation on β-O-4 linkages. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2017;5:10640–10648. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa I., Itoh T., Melik-ohanjanian R., et al. Synthesis and X-ray analysis of 1-benzyl-6-chlorouracil. ChemInform. 1991;22:1641–1646. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasparyan S., Alexanyan M., Arutyunyan G., et al. Synthesis of new derivatives of 5-(3, 4-dihydro-2 H-pyrrol-5-yl)-pyrimidine. Russ J Org Chem. 2016;52:1646–1653. [Google Scholar]

- 21.In response to the question raised during the review of this manuscript, the following additional insights were gained in order to explain the possible reasons why 1c lost the inhibitory activity: (1) Based on X-ray crystallographic analysis of 1b (3 CH2) bound in the allosteric site of P. aeruginosa RmlA (FigureS4 in ESI), there was a water network to stabilise the terminus NH group in 1b (3 CH2), while the same water mediated interactions might be not so tight in 1c (2 CH2) leaving the aminoalkyl chain in 1c free to move around; (2) Based on the molecular docking result (Figure S5 in ESI), the pyrimidinedione core in 1c was predicted to be shifted compared to that in 8a (a C6-NH2 compound in the original series). One possibility of the activity loss of 1c might be that the key interactions between pyrimidinedione core in 1c and P. aeruginosa RmlA might be weakened or lost.

- 22.Leeson P.D., Springthorpe B. The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:881–890. doi: 10.1038/nrd2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macielag M.J. Antibiotic Discovery and Development. Springer; 2012. Chemical properties of antimicrobials and their uniqueness; pp. 793–820. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Möllmann U., Heinisch L., Bauernfeind A., Köhler T., Ankel-Fuchs D. Siderophores as drug delivery agents: application of the “Trojan Horse” strategy. Biometals. 2009;22:615–624. doi: 10.1007/s10534-009-9219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mislin G.L., Schalk I.J. Siderophore-dependent iron uptake systems as gates for antibiotic Trojan horse strategies against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Metallomics. 2014;6:408–420. doi: 10.1039/c3mt00359k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller M.J., Malouin F. Microbial iron chelators as drug delivery agents: the rational design and synthesis of siderophore-drug conjugates. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993;26:241–249. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh A., Ghosh M., Niu C., Malouin F., Moellmann U., Miller M.J. Iron transport-mediated drug delivery using mixed-ligand siderophore-β-lactam conjugates. Chem. Biol. 1996;3:1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Möllmann U., Ghosh A., Dolence E.K., et al. Selective growth promotion and growth inhibition of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria by synthetic siderophore-β-lactam conjugates. Biometals. 1998;11:1–12. doi: 10.1023/a:1009266705308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richter M.F., Drown B.S., Riley A.P., et al. Predictive compound accumulation rules yield a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Nature. 2017;545:299–304. doi: 10.1038/nature22308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richter M.F., Hergenrother P.J. The challenge of converting Gram-positive-only compounds into broad-spectrum antibiotics. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019;1435:18–38. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Górska A., Sloderbach A., Marszałł M.P. Siderophore–drug complexes: potential medicinal applications of the ‘Trojan horse’strategy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014;35:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giraud M.F., Leonard G., Rahim R., Creuzenet C., Lam J., Naismith J. The purification, crystallization and preliminary structural characterization of glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RmlA), the first enzyme of the dTDP-L-rhamnose synthesis pathway from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:1501–1504. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900010040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leslie A. The integration of macromolecular diffraction data. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:48–57. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905039107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winter G. xia2: an expert system for macromolecular crystallography data reduction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2010;43:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabsch W.X.D.S. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vagin A., Teplyakov A. Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:22–25. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murshudov G.N., Vagin A.A., Dodson E.J. Refinement of Macromolecular Structures by the Maximum-Likelihood Method. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schuttelkopf A.W., Van Aalten D.M.F. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:1355–1363. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schrödinger L., DeLano W. Version; The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System: 2020. Pymol; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNicholas S., Potterton E., Wilson K.S., Noble M.E.M. Presenting your structures: the CCP4mg molecular-graphics software. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:386–394. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911007281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.