Abstract

To assess the antimicrobial resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated from 1993 through 1998 in Japan, susceptibility testing was conducted on 502 isolates. Selected isolates were characterized by auxotype and analysis for mutations within the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) in the gyrA and parC genes, which confer fluoroquinolone resistance on the organism. Plasmid-mediated penicillin resistance (penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae) decreased significantly from 1993–1994 (7.9%) to 1997–1998 (2.0%). Chromosomally mediated penicillin resistance decreased from 1993–1994 (12.6%) to 1995–1996 (1.9%) and then increased in 1997–1998 (10.7%). Chromosomally mediated tetracycline resistance decreased from 1993–1994 (3.3%) to 1997–1998 (2.0%), and no plasmid-mediated high-level tetracycline resistance was found. Isolates with ciprofloxacin resistance (MIC ≥ 1 μg/ml) increased significantly from 1993–1994 (6.6%) to 1997–1998 (24.4%). The proline-requiring isolates were less susceptible to ciprofloxacin than the prototrophic or arginine-requiring isolates. Ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates contained three or four amino acid substitutions within the QRDR in the GyrA and ParC proteins.

Gonococcal resistance to antimicrobial agents is an increasing problem in the treatment of gonorrhea. A high prevalence of plasmid-mediated high-level or chromosomally mediated low-level resistance to penicillin or tetracycline has been recognized in southeast Asia and in African countries (5, 13, 19, 20, 21). Fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin or ofloxacin, are highly effective as oral single-dose treatments for uncomplicated gonococcal infections caused by most gonococcal strains, including those with previously documented types of resistance (2, 7). Recently, fluoroquinolone regimens have been recommended for the treatment of gonorrhea (4, 12). However, the emergence of gonococcal isolates with reduced susceptibility or resistance to fluoroquinolones is a significant concern in several countries, including Japan (12, 14, 17, 25, 29). The failure of treatment of gonococcal infections with fluoroquinolones has also been reported sporadically (6, 30, 32, 33, 35). The treatment of gonorrhea has now become more complicated due to resistance to a variety of antimicrobial agents.

This study was performed to characterize the current antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and in particular, to examine the possibility of an increasing prevalence of high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Japan. In addition, we examined the correlation between auxotype and fluoroquinolone susceptibility and also the relationship between alteration patterns in DNA gyrase subunit A (GyrA) and topoisomerase IV parC-encoded subunit (ParC) proteins, which confer quinolone resistance on the organisms, and the ciprofloxacin resistance level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

N. gonorrhoeae strains.

From January 1993 through December 1998, a total of 502 isolates of N. gonorrhoeae were collected from consecutive male patients with urethritis attending a sexually transmitted diseases clinic in Fukuoka City. However, posttreatment isolates or repeat isolates from the same patients were excluded in this study. Specimens from each patient were inoculated directly onto Thayer-Martin selective agar (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.), transported to the Mitsubishi Kagaku Laboratory by a commercially available transport system (Bio-Bag environmental chamber type C; Becton Dickinson), and incubated for 24 to 48 h at 35°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. N. gonorrhoeae was identified as a gram-negative diplococcus and by oxidase reaction and sugar utilization patterns. The isolates were suspended in cryoprotective medium as described by Obara et al. (24) and stored at −80°C until they were tested.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MICs for all isolates were determined by an agar dilution technique with a GC agar base (Becton Dickinson) containing 1% IsoVitaleX (Becton Dickinson) and twofold dilutions of antibiotic (22). Plates were inoculated with 5 μl of 106 CFU of each isolate/ml with a multipoint inoculator (Microplanter; Sakuma Seisakusho, Tokyo, Japan). Five World Health Organization N. gonorrhoeae reference strains (A, B, C, D, and E) were included as quality control strains. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 35°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. MICs were defined as the lowest antibiotic concentrations that inhibited bacterial growth. β-Lactamase production was assayed by the chromogenic cephalosporin test. The antimicrobial agents tested were penicillin G (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), tetracycline (Lederle Japan, Tokyo, Japan), ceftriaxone (Nippon Roche, Tokyo, Japan), cefixime (Fujisawa Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan), ciprofloxacin (Bayer Yakuhin, Osaka, Japan), azithromycin (Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan), and spectinomycin (Sigma Chemical). All of the antibiotics were obtained as powders of stated potency from their manufacturers. The ranges of concentrations of the antibiotics tested were as follows: penicillin G, 0.004 to 64 μg/ml; tetracycline, 0.004 to 64 μg/ml; ceftriaxone, 0.001 to 4 μg/ml; cefixime, 0.001 to 4 μg/ml; ciprofloxacin, 0.001 to 64 μg/ml; and spectinomycin, 1 to 128 μg/ml. The isolates were sequentially grouped into mutually exclusive categories according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guidelines as follows (22): penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae (PPNG) (β-lactamase positive; tetracycline MIC, <16 μg/ml); plasmid-mediated tetracycline-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (TRNG) (β-lactamase negative; tetracycline MIC, ≥16 μg/ml); PPNG-TRNG (β-lactamase positive; tetracycline MIC, ≥16 μg/ml); chromosomally mediated penicillin-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (non-PPNG and non-TRNG; penicillin MIC, ≥2 μg/ml; tetracycline MIC, <2 μg/ml); chromosomally mediated tetracycline-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (non-PPNG and non-TRNG; penicillin MIC, <2 μg/ml; tetracycline MIC, ≥2 μg/ml); chromosomally mediated penicillin- and tetracycline-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (CMRNG) (non-PPNG and non-TRNG; penicillin MIC, ≥2 μg/ml; tetracycline MIC, ≥2 μg/ml). Proposed criteria were used to interpret the ciprofloxacin MIC (18); isolates for which the MICs were ≥1 μg/ml were classified as resistant to ciprofloxacin, and isolates for which the MICs were 0.125 to 0.5 μg/ml were interpreted as exhibiting reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. Furthermore, isolates for which the ceftriaxone or cefixime MICs were ≥0.5 μg/ml were categorized as having decreased susceptibility to the respective agent (22).

Auxotyping.

Auxotyping of the selected gonococcal isolates was undertaken as described by Catlin (3). Isolates were tested on chemically defined media for their nutritional requirements for proline, arginine, hypoxanthine, uracil, methionine, and histidine. Strains with no requirements for the substances used were designated prototrophic (Proto).

Molecular study.

PCR and direct DNA sequencing were performed to identify mutations in the gyrA and parC genes of the gonococcal isolates. Chromosomal DNA was extracted by standard methods and was subjected to PCR. The oligonucleotide primers for the PCR amplification were as follows: for the gyrA gene, forward primer, 5′-160CGGCGCGTACTGTACGCGATGCA182-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-438AATGTCTGCCAGCATTTCATGTGAGA413-3′; for the parC gene, forward primer, 5′-166ATGCGCGATATGGGTTTGAC185-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-420GGACAACAGCAATTCCGCAA401-3′. These primers were produced with a DNA synthesizer, according to sequences previously reported by Belland et al. (1). The gyrA gene sequence was determined from nucleotides 160 to 438, which correspond to amino acids 54 to 146 of the GyrA protein. This includes the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) (amino acids 55 to 110 of the gonococcal GyrA protein) (1). The parC gene sequence was also determined from nucleotides 166 to 420, which correspond to amino acids 56 to 140 of the gonococcal ParC protein. This includes the QRDR of the ParC protein (amino acids 66 to 119 of the gonococcal ParC protein) (1).

The PCR amplification was performed in 25 μl of a reaction mixture which contained 2.5 μl of 10× Taq polymerase buffer (500 mM KCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 15 mM MgCl2, 0.1% gelatin), 0.25 μl of each of the two primers (25 pmol/μl), 0.5 μl of each of the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (10 mM), 0.2 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μl) (Takara Biomedicals, Tokyo, Japan), 2.5 μl of Triton X-100 (2 mg/ml), and 1.0 μl of template DNA (100 ng/μl). Thirty-five cycles were performed for each reaction. Each cycle consisted of 30 s at 93°C, 1 min at 52°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The PCR amplification products were directly sequenced with a Taq DyeDeoxy terminator cycle-sequencing kit and a Model 373A autosequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Statistical analysis.

The data were analyzed with StatView J-4.5 software (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, Calif.). Median MIC values were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test or by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Proportions were compared by the chi-square test. Statistical significance for all P values was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Ciprofloxacin resistance.

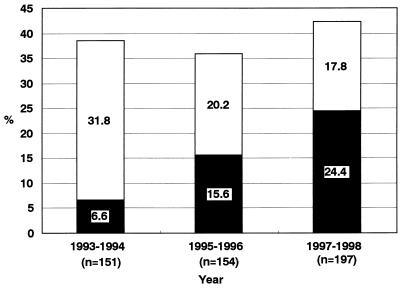

The proportion of isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin (MIC ≥ 1 μg/ml) increased remarkably from 6.6% in 1993–1994 to 24.4% in 1997–1998 (Fig. 1). This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). However, the proportions of isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin plus isolates with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (MIC, 0.125 to 0.5 μg/ml) were similar for all three study periods (Fig. 1). The ciprofloxacin MICs at which 90% of the isolates tested were inhibited (MIC90s) for the isolates in 1995–1996 (1 μg/ml) and in 1997–1998 (8 μg/ml) were 2- and 16-fold, respectively, higher than that for the isolates in 1993–1994 (0.5 μg/ml) (Table 1). The median MICs of penicillin G and tetracycline were significantly higher for the isolates with resistance or reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin than for ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates (median MIC of penicillin G, 1 versus 0.125 μg/ml; median MIC of tetracycline, 0.5 versus 0.125 μg/ml; P < 0.0001 for both comparisons). The median MICs of ceftriaxone and cefixime were also significantly higher for the isolates with resistance or reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin than for ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates (median MIC of ceftriaxone, 0.063 versus 0.004 μg/ml; median MIC of cefixime, 0.063 versus 0.008 μg/ml; P < 0.0001 for both comparisons). However, there were no significant differences in susceptibility to spectinomycin and azithromycin between isolates with resistance or reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates (median MIC of spectinomycin, 8 versus 8 μg/ml [P = 0.7141]; median MIC value of azithromycin, 0.125 versus 0.125 μg/ml [P = 0.2474]).

FIG. 1.

Increase in ciprofloxacin-resistant N. gonorrhoeae. ■, resistance (MIC, ≥1 μg/ml); □, reduced susceptibility (MIC, 0.125 to 0.5 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of N. gonorrhoeae

| Antibiotic | Susceptibility (μg/ml)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993–1994 (n = 151)

|

1995–1996 (n = 154)

|

1997–1998 (n = 197)

|

|||||||

| MIC50 | MIC90 | Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | Range | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.063 | 0.5 | ≤0.001–8 | 0.031 | 1 | 0.004–16 | 0.031 | 8 | 0.002–16 |

| Penicillin Ga | 0.25 | 2 | 0.008–2 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.016–2 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.031–4 |

| Tetracycline | 0.5 | 1 | 0.063–8 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.063–4 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.063–2 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.016 | 0.063 | ≤0.001–0.25 | 0.016 | 0.125 | ≤0.001–0.125 | 0.008 | 0.125 | ≤0.001–0.25 |

| Cefexime | 0.016 | 0.125 | ≤0.001–0.25 | 0.008 | 0.063 | ≤0.001–0.125 | 0.016 | 0.125 | 0.002–0.5 |

| Azithromycin | 0.063 | 0.25 | 0.008–1 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.016–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.016–1 |

| Spectinomycin | 8 | 8 | 2–16 | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | 8 | 16 | 4–16 |

Only non-PPNG strains were compared.

We then analyzed the relationship between auxotype and ciprofloxacin susceptibility in 116 N. gonorrhoeae isolates collected consecutively during the first three quarters of 1995–1996 (Table 2). Three predominant auxotypes were Proto (39.7%), proline requiring (Pro) (29.3%), and arginine requiring (Arg) (25.9%). The MIC at which 50% of the isolates tested were inhibited (MIC50) and MIC90 of ciprofloxacin for the Pro isolates were higher than those for the Proto or Arg isolates.

TABLE 2.

Relationship between auxotype and ciprofloxacin susceptibility in N. gonorrhoeae

| Auxotypea | No. of isolates (%) | Ciprofloxacin MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50 | MIC90 | Range | ||

| Proto | 46 (39.7) | 0.031 | 0.25 | 0.004–8 |

| Pro | 34 (29.3) | 0.25 | 2 | 0.008–16 |

| Arg | 30 (25.9) | 0.008 | 0.063 | 0.004–0.063 |

| Pro-Hypo | 2 (1.7) | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.063–0.125 |

| Arg-Hypo | 1 (0.9) | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| AHU | 3 (2.6) | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

Pro-Hypo, proline and hypoxanthine requiring; Arg-Hypo, arginine and hypoxanthine requiring; AHU, arginine, hypoxanthine, and uracil requiring.

We also investigated the genetic alterations within the QRDR in the gyrA and parC genes in the isolates susceptible or resistant to ciprofloxacin (Table 3). Interestingly, all the isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin contained three or four amino acid substitutions in the GyrA and ParC proteins, while the isolates with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin contained one to three amino acid substitutions in GyrA alone or in GyrA and ParC. Moreover, of the ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates tested (MIC, 0.004 to 0.063 μg/ml), 41.3% (26 of 63) had a single alteration in GyrA alone. The frequently identified substitutions were a serine-to-phenylalanine substitution at position 91 (serine-91 in N. gonorrhoeae GyrA corresponds to Ser-83 in Escherichia coli [1]) and an aspartic acid-to-asparagine substitution at position 95 in GyrA, while they were a serine-to-proline substitution at position 88, an aspartic acid-to-asparagine substitution at position 86, and a glutamic acid-to-glycine or -lysine substitution at position 91 in ParC.

TABLE 3.

Amino acid substitutions within GyrA and ParC in 128 isolates of N. gonorrhoeae

| Ciprofloxacin MIC (μg/ml) (no. of isolates tested) | Substitutiona

|

No. of isolates | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GyrA

|

ParC

|

|||||||||||

| Ala-67 | Ala-75 | Ala-84 | Ser-91 | Asp-95 | Asp-86 | Ser-87 | Ser-88 | Glu-91 | Ala-92 | Arg-116 | ||

| 0.004–0.063 (n = 63) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 37 |

| Ser | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| – | Ser | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | |

| – | – | Pro | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| – | – | – | Cys | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | – | Gly | – | – | – | – | – | – | 11 | |

| – | – | – | – | Asn | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | |

| 0.125–0.5 (n = 36) | – | – | – | Phe | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 23 |

| – | – | – | Phe | Gly | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | Asn | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | Tyr | – | – | – | – | – | – | His | 1 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | – | Asn | – | – | – | – | – | 7 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | – | – | – | – | – | Gly | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | – | – | – | Pro | Gly | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | Asn | – | – | Pro | – | – | – | 1 | |

| 1–16 (n = 29) | – | – | – | Phe | Asn | – | – | Pro | – | – | – | 17 |

| – | – | – | Phe | Gly | – | – | – | Gly | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | Asn | – | Arg | Pro | – | – | – | 5 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | Asn | – | Ile | Pro | – | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | Asn | – | – | Pro | Gly | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | Asn | – | – | Pro | Gln | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | Phe | Asn | – | – | Pro | Lys | – | – | 3 | |

The numbering of amino acids is from reference 1. A dash indicates sequence homology.

Susceptibilities to penicillin and tetracycline.

The proportion of isolates with any type of resistance to penicillin or tetracycline decreased from 23.2% in 1993–1994 to 6.5% in 1994–1995 and then increased to 12.7% in 1997–1998 (Table 4). The prevalence of PPNG strains significantly decreased from 7.9% in 1993–1994 to 2.0% in 1997–1998 (P = 0.0326). However, the percentage of chromosomally mediated resistance to penicillin alone decreased from 11.9% in 1993–1994 to 1.9% in 1994–1995 and then increased to 9.6% in 1997–1998. The MIC50 and MIC90 of penicillin for the non-PPNG strains in 1997–1998 were equal to those for the non-PPNG strains in 1993–1994 (Table 1). No TRNG or PPNG-TRNG isolates were detected during the study period. The percentage of chromosomally mediated resistance to tetracycline alone decreased from 2.6% in 1993–1994 to 0% in 1994–1995 and 1997–1998. Only three strains of CMRNG were identified during the study period. The tetracycline MIC50 and MIC90 for the isolates in 1997–1998 were only twofold lower and twofold higher, respectively, than those for the isolates in 1993–1994.

TABLE 4.

Penicillin and tetracycline resistance in N. gonorrhoeae

| Categorya | No. (%) resistant

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993–1994 (n = 151) | 1995–1996 (n = 154) | 1997–1998 (n = 197) | |

| PPNG | 12 (7.9) | 7 (4.5) | 4 (2.0) |

| TRNG | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PPNG-TRNG | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CMPR | 18 (11.9) | 3 (1.9) | 19 (9.6) |

| CMTR | 4 (2.6) | 0 | 0 |

| CMRNG | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 2 (1.0) |

| Total | 35 (23.2) | 10 (6.5) | 25 (12.7) |

CMPR, chromosomally mediated penicillin-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (non-PPNG and non-TRNG; penicillin MIC, ≥2 μg/ml; tetracycline MIC, <2 μg/ml. CMTR, chromosomally mediated tetracycline-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (non-PPNG and non-TRNG; penicillin MIC, <2 μg/ml; tetracycline MIC, ≥2 μg/ml).

Susceptibilities to ceftriaxone, cefixime, azithromycin, and spectinomycin.

There were no significant changes in the gonococcal susceptibilities to ceftriaxone, cefixime, azithromycin, or spectinomycin during this period. In general, the MIC50s and MIC90s of these agents for the 1997–1998 isolates were equal, only twofold higher or twofold lower than those for 1993–1994 (Table 1). Only three isolates in 1997–1998 showed reduced susceptibility to cefixime (MIC, 0.5 μg/ml).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that the incidence of PPNG strains significantly decreased from 1993–1994 (7.9%) to 1997–1998 (2.0%) and the incidence of chromosomally or plasmid-mediated tetracycline resistance was very low during the study period. However, the percentage of ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates increased significantly from 1993–1994 (6.6%) to 1997–1998 (24.4%). Frequent usage of fluoroquinolones against gonorrhea may lead to the rapid development of resistance to these agents. We have recently undertaken a survey of the usage of antimicrobial agents against gonococcal infections by mailing a questionnaire to sexually transmitted disease clinics in Fukuoka city. Fluoroquinolones were most frequently used (46%) as first-line treatment for gonorrhea, followed by penicillins with or without a β-lactamase inhibitor (28%), cephems (16%), and others (10%). Of various fluoroquinolones available in Japan, a 7-day course of levofloxacin (200 mg twice a day or 100 mg three times a day) was most frequently used in the treatment of gonococcal infections (M. Tanaka, unpublished data), because this regimen is effective against urethritis caused not only by N. gonorrhoeae alone but also by both N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis (15). The increase in fluoroquinolone resistance has also been substantial in some countries: in Hong Kong; it rose from 7.7% in 1995 to 24% in 1996; in Singapore, it rose from 0.3% in 1993 to 3.5% in 1996; and in Australia, it rose from 0.1% in 1992 to 2.6% in 1996 (12). However, in the United States, where fluoroquinolone regimens are recommended as first-line therapy for gonorrhea, quinolone resistance is still uncommon, except for certain areas. It has been reported that in 1994 quinolone resistance in N. gonorrhoeae isolates was only 0.04% (2 of 4,996) in the United States (10). Standard usage of fluoroquinolones in Japan has preceded the use of many of these agents in the United States by many years. Thus, findings in Japan may well indicate that the increase in fluoroquinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae isolates will also become a significant problem in the United States in the future.

Auxotyping involves characterization of nutritional requirements for the growth of N. gonorrhoeae isolates. A variety of gonococcal auxotypes with different geographic distributions have been reported (26). In our study, the three predominant auxotypes were Proto (39.7%), Pro (29.3%), and Arg (25.9%) in 1995–1996. Our results showed an association between the auxotype and ciprofloxacin susceptibility. The median MIC of ciprofloxacin for the Pro isolates was significantly higher than that for the Proto or Arg isolates. Moreover, there was a correlation between the increase in the proportion of Pro isolates and the increase in the percentage of ciprofloxacin resistance. The incidence of the Pro isolates increased from 4.4% in 1992 (M. Tanaka, unpublished data) to 29.3% in 1995–1996, while ciprofloxacin resistance also increased from 0% in 1992 (28) to 15.6% in 1995–1996. To investigate whether these correlations are due to dissemination of the same clone requiring proline in Japan, we will examine gonococcal serovar or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns, which are also useful epidemiological markers for monitoring gonococcal epidemics. Interestingly, in the United States, all isolates with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin were non-PPNG and Pro isolates (16). Some of the isolates with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in the United States may have been imported from Japan. Pro isolates of non-PPNG strains are generally less susceptible to antibiotics than non-Pro isolates (23, 36). Therefore, Pro gonococcal isolates may more easily acquire chromosomally mediated resistance not only to β-lactams but also to structurally unrelated fluoroquinolones than non-Pro isolates.

Alterations in serine-91 and aspartic acid-95 in GyrA, corresponding to serine-83 and aspartic acid-87 in the E. coli GyrA (1), respectively, were most frequently found among the clinical isolates with resistance or reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. Changes in ParC were clustered within the region between aspartic acid-86 and alanine-92, which corresponds to the region from aspartic acid-79 to alanine-85 in the E. coli ParC (1). These amino acid substitutions were also identified in our preliminary results (31) and other investigations (1, 8). Surprisingly, 41.3% of the ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates had various single alterations in GyrA alone. There was a unique isolate containing a serine-to-tyrosine substitution at position 91 in GyrA and an arginine-to-histidine substitution at position 116 in ParC. Recently, gonococcal isolates with a substitution at position 116 in ParC were also detected in the United States (34).

The MICs of structurally unrelated penicillin, tetracycline, and cephems for the isolates with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin were higher than those for isolates susceptible to ciprofloxacin. The median MICs of penicillin G, tetracycline, ceftriaxone, and cefixime for the isolates with resistance or reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin were 4 to 16 times higher than those for the isolates susceptible to ciprofloxacin. In this investigation, all the isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin contained three or four amino acid substitutions within the QRDR in the GyrA and ParC proteins, and the isolates with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin contained one to three amino acid substitutions in GyrA alone or in GyrA and ParC. These results suggest that the isolates showing resistance or decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, which have chromosomal mutations in gyrA with or without parC genes, may be combined with well-known chromosomal mutations at other loci, such as penA, penB, and mtr (9). Isolates containing the gyrA and parC mutations, combined with chromosomal mutations at other loci, are likely to acquire resistance not only to fluoroquinolones but also to penicillins, cephalosporins, and tetracycline. A recent study showed that mutations in the mtrR coding region or a single-base-pair deletion in a 13-bp inverted repeat in its promoter enhances mtrCDE gene expression, leading to elevated levels of multidrug resistance in gonococci (multidrug efflux pump) (27). Other studies indicated that a mutation in penB confers resistance to structurally unrelated β-lactams and tetracycline and reduced susceptibility to quinolones on N. gonorrhoeae (reduced porin permeability) (11).

In Japan, where a high prevalence of isolates with resistance or reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin has been shown, ceftriaxone, cefixime, or spectinomycin is recommended as the first-line treatment for gonococcal infections. Fluoroquinolones should be avoided, and the surveillance of antimicrobial resistance of N. gonorrhoeae, and in particular, the evolution of high-level fluoroquinolone resistance, should be continued in Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belland R J, Morrison S G, Ison C A, Huang W M. Neisseria gonorrhoeae acquires mutations in analogous regions of gyrA and parC in fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:371–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryan J P, Hira S K, Brady W, Luo N, Mwale C, Mpoko G, Krieg R, Siwiwaliondo E, Reichart C, Waters C, Perine P. Oral ciprofloxacin versus ceftriaxone for the treatment of urethritis from resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Zambia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:819–822. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.5.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catlin B W. Nutritional profiles of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Neisseria lactamica in chemically defined media and use of growth requirements for gonococcal typing. J Infect Dis. 1973;128:178–194. doi: 10.1093/infdis/128.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1993;42(RR-14):57–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalkley L J, Janse van Rensburg M N, Matthee P C, Ison C A, Botha P L. Plasmid analysis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates and dissemination of tetM genes in southern Africa 1993–1995. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:817–822. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.6.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corkill J E, Percival A, Lind M. Reduced uptake of ciprofloxacin in a resistant strain of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and transformation of resistance to other strains. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;28:601–604. doi: 10.1093/jac/28.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Covino J M, Cummings M, Smith B, Benes S, Draft K, McCormack W M. Comparison of ofloxacin and ceftriaxone in the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea caused by penicillin producing and non-penicillin-producing strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:148–149. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.1.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deguchi T, Yasuda M, Nakano M, Ozeki S, Ezaki T, Saito I, Kawada Y. Quinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae: correlation of alterations in the GyrA subunit of DNA gyrase and the ParC subunit of topoisomerase IV with antimicrobial susceptibility profiles. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1020–1023. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dillon J A R, Yeung K H. β-Lactamase plasmids and chromosomally mediated antibiotic resistance in pathogenic Neisseria species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2(Suppl.):125–133. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.suppl.s125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox K K, Knapp J S, Holmes K K, Hook III E W, Judson F N, Thompson S E, Washington J A, Whittington W L. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United States, 1988–1994: the emergence of decreased susceptibility to the fluoroquinolones. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1396–1403. doi: 10.1086/516472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill M J, Simjee S, Al-Hattawi K, Robertson B D, Easmon C S, Ison C A. Gonococcal resistance to beta-lactams and tetracycline involves mutation in loop 3 of the porin encoded at the penB locus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2799–2803. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ison C A, Dillon J A R, Tapsall J W. The epidemiology of global antibiotic resistance among Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Haemophilus ducreyi. Lancet. 1998;351(Suppl. III):8–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joesoef M R, Knapp J S, Idajadi A, Linnan M, Barakbah Y, Kamboji A A, O'Hanley P, Moran J S. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains isolated in Surabaya, Indonesia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2530–2533. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.11.2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kam K M, Wong P W, Cheung M M, Ho N K Y, Lo K K. Quinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Hong Kong. Sex Transm Dis. 1996;23:103–108. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawada Y, Murakami S, Aso Y, Machida T, Saito I, Ishibashi A, Kawamura N, Okoshi M, Suzuki K, Kawamura K, Hisazumi H, Okada K, Osato K, Kamidono S, Omori H, Usui T, Kagawa S, Fujita Y, Kumazawa J, Eto K, Ohi Y, Deguchi K. Studies on the clinical value of levofloxacin in the treatment of genitourinary tract infections. Chemotherapy (Tokyo) 1992;40:249–269. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilmarx P H, Knapp J S, Xia M, St. Louis M E, Neal S W, Sayers D, Doyle L J, Roberts M C, Whittington W L. Intercity spread of gonococci with decreased susceptibility to fluoroquinolones: a unique focus in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:677–682. doi: 10.1086/514234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knapp J S, Fox K K, Trees D L, Whittington W L. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:33–39. doi: 10.3201/eid0301.970104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knapp J S, Hale J A, Neal S W, Wintersheid K, Rice R J, Whittington W L. Proposed criteria for interpretation of susceptibilities of strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, enoxacin, lomefloxacin, and norfloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2442–2445. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knapp J S, Mesola V P, Neal S W, Wi T E, Tuazon C, Manalastas R, Perine P L, Whittington W L. Molecular epidemiology, in 1994, of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Manila and Cebu City, Republic of the Philippines. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:2–7. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199701000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knapp J S, Wongba C, Limpakarnjanarat K, Young N L, Parekh M C, Neal S W, Buatiang A, Chitwarakorn A, Mastro T D. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Bangkok, Thailand: 1994–1995. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:142–148. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199703000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason P R, Gwanzura L, Latif A S, Marowa E, Ray S, Katzenstein D A. Antimicrobial resistance in gonococci isolated from patients and from commercial sex workers in Harare, Zimbabwe. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1997;9:175–179. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(97)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A3. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noble R C, Parekh M C. Association of auxotypes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and susceptibility to penicillin G, spectinomycin, tetracycline, cefaclor, cefoxitin, and moxalactam. Sex Transm Dis. 1983;10:18–23. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obara Y, Yamai S, Nikkawa T, Shimoda Y, Miyamoto Y. Preservation and transportation of bacteria by a simple gelatin disk method. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;14:61–66. doi: 10.1128/jcm.14.1.61-66.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross J D. Fluoroquinolone resistance in gonorrhea: how, where and so what. Int J STD AIDS. 1998;9:318–322. doi: 10.1258/0956462981922322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarafian S K, Knapp J S. Molecular epidemiology of gonorrhea. Clin Microb Rev. 1989;2(Suppl.):49–55. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.suppl.s49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shafer W M, Balthazar J T, Hagman K E, Morse S A. Missense mutations that alter the DNA-binding domain of the MtrR protein occur frequently in rectal isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae that are resistant to faecal lipids. Microbiology. 1995;141:907–911. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-4-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka M, Kumazawa J, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi I. High prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains with reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones in Japan. Genitourin Med. 1994;70:90–93. doi: 10.1136/sti.70.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka M, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi I, Uchino U, Kumazawa J. Emergence of in vitro resistance to fluoroquinolones in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2367–2370. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka M, Matsumoto T, Sakumoto M, Takahashi K, Saika T, Kobayashi I, Kumazawa J. Reduced clinical efficacy of pazufloxacin against gonorrhea due to high prevalence of quinolone-resistant isolates with the GyrA mutation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:579–582. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka M, Takahashi K, Saika T, Kobayashi I, Ueno T, Kumazawa J. Development of fluoroquinolone resistance and mutations involving GyrA and ParC proteins among Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Japan. J Urol. 1998;159:2215–2219. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tapsall J W, Limnios E A, Thacker C, Donovan B, Lynch S D, Kirby L J, Wise K A, Carmody C J. High-level quinolone resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a report of two cases. Sex Transm Dis. 1995;22:310–311. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson C, Young H, Moyes A. Ciprofloxacin resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Genitourin Med. 1995;71:412–413. doi: 10.1136/sti.71.6.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trees D L, Sandul A L, Whittington W L, Knapp J S. Identification of novel mutation patterns in the parC gene of ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2103–2105. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Willigen A H, van der Hoek J C, Wagenvoort J H, van Vliet H J, van Klingeren B, Schalla W O, Knapp J S, van Joost T, Michel M F, Stolz E. Comparative double-blind study of 200- and 400-mg enoxacin given orally in the treatment of acute uncomplicated urethral gonorrhea in males. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:535–538. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.4.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Klingeren B, Ansink-Schipper M C, Doornbos L, Lampe A S, Wagenvoort J H, Dessens-Kroon M, Verheuvel M. Surveillance of the antibiotic susceptibility of non-penicillinase producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae in The Netherlands from 1983 to 1986. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;21:737–744. doi: 10.1093/jac/21.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]