Abstract

Objectives

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) represents the primary receptor for SARS-CoV-2 to enter endothelial cells. Here we investigated circulating ACE2 activity to predict the severity and mortality of COVID-19.

Methods

Serum ACE2 activity was measured in COVID-19 (110 critically ill and 66 severely ill subjects at hospital admission and 106 follow-up samples) and in 32 non-COVID-19 severe sepsis patients. Associations between ACE2, inflammation-dependent biomarkers, pre-existing comorbidities, and clinical outcomes were studied.

Results

Initial ACE2 activity was significantly higher in critically ill COVID-19 patients (54.4 [36.7-90.8] mU/L) than in severe COVID-19 (34.5 [25.2-48.7] mU/L; P<0.0001) and non-COVID-19 sepsis patients (40.9 [21.4-65.7] mU/L; P=0.0260) regardless of comorbidities. Circulating ACE2 activity correlated with inflammatory biomarkers and was further elevated during the hospital stay in critically ill patients. Based on ROC-curve analysis and logistic regression test, baseline ACE2 independently indicated the severity of COVID-19 with an AUC value of 0.701 (95% CI [0.621-0.781], P<0.0001). Furthermore, non-survivors showed higher serum ACE2 activity vs. survivors at hospital admission (P<0.0001). Finally, high ACE2 activity (≥45.4 mU/L) predicted a higher risk (65 vs. 37%) for 30-day mortality (Log-Rank P<0.0001).

Conclusions

Serum ACE2 activity correlates with COVID-19 severity and predicts mortality.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, ACE2, inflammation, COVID-19 disease, biomarker, outcome, sepsis

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been associated with significant morbidity and mortality worldwide in the last 1.5 years. This disease is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and represents a mild course in the majority of cases; however, about one-fifth of the patients develop severe clinical complications, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), systemic hyperinflammatory response and death (Huang et al. 2020, Martincic et al. 2020). There are several risk factors for fatal infection, e.g., increasing age, male sex, smoking, history of hypertension, heart, lung, and kidney disorders (Zhou et al. 2020; Kaur et al. 2021).

Endothelial cells express angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on their surface, which also is the primary receptor for SARS-CoV-2 (Hoffmann et al. 2020). ACE2 mediates the infection of endothelial cells, which induces endothelial activation and damage resulting in substantial release of von Willebrand factor (Escher et al. 2020) and enhanced levels of soluble E-selectin (Nagy et al. 2021). In parallel, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples from COVID-19 subjects showed a critical imbalance in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) with upregulated expression of ACE2, renin and kallikrein enzymes (Garvin et al. 2020). Due to the cleavage of angiotensin II (Ang II) into Ang-1-7 by the zinc-metalloprotease ACE2 (Paz Ocaranza et al. 2020), decreased Ang II level and enhanced Ang-1-7 formation were determined in the presence of increased ACE2 function in severe COVID-19 compared to healthy controls (van Lier et al. 2021). Nonetheless, their impact on clinical outcomes is not clearly understood. However, ACE2 has been implicated in the pathomechanism of various cardiovascular diseases, which represent a risk for COVID-19 mortality. In particular, elevated circulating ACE2 levels were reported in heart failure (Úri et al. 2014; Úri et al. 2016; Fagyas et al. 2021) and hypertension (Úri et al. 2016). It was hypothesized that secretion of ACE2 from cardiovascular tissues contributes to the elevation of circulating ACE2 and results in a dysregulation of ACE/ACE2 balance in the tissues of cardiovascular patients (Úri et al. 2016), similarly being implicated in severe COVID-19 (Garvin et al. 2020; van Lier et al. 2021).

Recently, controversial data have been reported on soluble ACE2 levels in COVID-19 patients. In contrast to healthy individuals having low circulating ACE2 activity (Patel et al. 2021), upregulated ACE2 protein level (van Lier et al. 2021; Kragstrup et al. 2021; Kaur et al. 2021) and activity (Nagy et al. 2021; Patel et al. 2021; Kaur et al. 2021; Reindl-Schwaighofer et al. 2021) were identified. In contrast, others found no change (Rieder et al., 2021; Kintscher et al. 2020) or lower ACE2 in severe COVID-19 patients than pre-pandemic controls (Rojas et al. 2021). Furthermore, it is still not evident how the circulating ACE2 level is affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection and recovery. Increasing levels of ACE2 were found in the first two weeks of the acute phase of COVID-19 (Lundström et al. 2021; Reindl-Schwaighofer et al. 2021). However, soluble ACE2 levels remained increased for 1-3 months following infection (Rojas et al. 2021; Patel et al. 2021) and showed a reduction by four months of the disease course (Lundström et al. 2021).

In this study, our aims were i) to compare circulating ACE2 activity in critically ill and severe COVID-19 patients; ii) contrast these values to non-COVID-19 severe septic subjects, iii) to correlate serum ACE2 activity with routinely measured laboratory biomarkers and clinical parameters, such as Horowitz index, and iv) to evaluate whether ACE2 activity at the hospital admission predicts the severity and outcome of the severe COVID-19.

Materials and methods

Patient cohorts

In this retrospective clinical study, in total 176 consecutive COVID-19 patients older than 18 years of age were recruited in parallel at two medical centers (Clinical Center and Gyula Kenézy Campus, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary and National Institute of Hematology and Infectiology, South-Pest Central Hospital, Budapest, Hungary). These subjects suffered from different degrees of acute respiratory distress at admission and were confirmed to be positive for COVID-19 disease by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) test of a nasopharyngeal swab. Critically ill patients were then transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at either center, while those with moderate symptoms were treated at the Department of Infectious Diseases, Gyula Kenézy Campus, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary. Patients were divided into two severity subgroups: 110 individuals were considered as ‘critically ill’ patients; another 66 patients presenting with moderate symptoms were enrolled into the ‘severe’ cohort based on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores determined by the clinicians and the requirement for respiratory support during hospitalization. Critically ill patients had SOFA scores, median (IQR) of twelve (10-13), while severe patients had SOFA scores of four (3-8). In parallel, 32 critically ill septic patients treated in ICU with SOFA scores of ten (5-11) and negative COVID-19 RT-qPCR tests were included; they were age- and sex-matched to severe COVID-19 subjects. Sepsis was diagnosed based on the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus criteria. Two-thirds of these patients had a positive hemoculture (e.g., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, etc.), while the rest of the individuals were culture-negative.

Blood sampling and laboratory analyses

All subjects had peripheral blood samples drawn at admission, and follow-up samples were also available before discharge or death in the case of 106 subjects. Specimens were obtained from non-COVID-19 septic patients within the first 24 hours upon admission. Patient age, pre-existing comorbidities, COVID-19 specific treatment, administration of invasive ventilation, and the outcome were recorded by clinicians. Routinely available laboratory serum tests were performed at the Department of Laboratory Medicine, University of Debrecen. Sera were stored at -70°C; the analysis of serum ACE2 activity was performed by a specific quenched fluorescent substrate (obtained from http://peptide2.com) as reported earlier (Nagy et al. 2021; Fagyas et al. 2021 Oct 21). For more details, see Supplementary materials.

To evaluate overall lung function and oxygenation in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 sepsis patients suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the PaO2/FiO2 (P/F) ratio, also known as the Horowitz index, was determined in 106 study participants. This index was calculated by the clinicians as follows: PaO2/FiO2 ratio (P/F, mmHg) = Partial pressure of oxygen PaO2 (mmHg) / Fraction of inspired oxygen FiO2 (%) (Ranieri et al. 2012). An index below 100 mmHg was defined severe, 100-200 mmHg moderate, and 200-300 mmHg mild ARDS.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 6.01, La Jolla, CA, USA). For more details, see Supplementary materials.

Results

Initial characteristics of critically ill and severe COVID-19 patients

This study recruited 176 COVID-19 positive subjects to analyze serum ACE2 activity upon hospital admission and during hospital treatment. Patients were divided into two subgroups, critically ill and severe, based on disease severity: 110 individuals were critically ill patients, and 66 suffered from moderate COVID-19 symptoms (Table 1 ). Critically ill patients were older than those with severe disease (median [IQR] 67 [59-76] vs. 61 [52-65] years; P < 0.0001), while there was no difference in sex between the two cohorts. No difference was observed in the length of hospital stay between the critically ill and severe groups (median [IQR] ten [5-19] vs. eight [6-12] days; P = 0.1517). Mechanical ventilation was applied more frequently in critically ill than severe COVID-19 subjects (96 vs. six patients, respectively). Out of 110 critically ill patients, 86 (78.2%) died of COVID-19 disease in contrast to the severe cohort with three non-survivors (4.5%) out of 66 patients (P < 0.0001). According to the routine laboratory investigation, significantly higher levels of inflammation-specific parameters, i.e., CRP, IL-6, and ferritin, as well as WBC count, were found among the critically ill than severe COVID-19 conditions. On the other hand, platelet count did not differ between the two cohorts, as no severe thrombocytopenia developed in these subjects. Age- and sex-matched non-COVID-19 severe septic patients showed similar SOFA scores compared to severe COVID-19 subjects; however, the mortality rate was lower in these non-COVID-19 ICU patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographical, clinical and routine laboratory characteristics of 176 COVID-19 patients divided into two subgroups based on severity of the disease and 32 non-COVID-19 severe septic subjects. Data are expressed as medians with IQR. Horowitz index (P/F) was determined by the clinicians, and medians with IQR values of P/F ratio were calculated based on the data of a limited number of critically ill (n = 80) and severe (n = 26) COVID-19 subjects as well as non-COVID-19 severe septic patients (n = 21). For statistical analyses, chi square test or Mann-Whitney U test were used, as appropriate. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were found in comparisons indicated with variable symbols as follows: significantly different value from: * = critically ill COVID-19 subgroup; # = severe COVID-19 subgroup; § = non-COVID-19 sepsis subgroup. Abbreviations: CRP: C-reactive protein, PCT: procalcitonin, IL-6: interleukin-6, AST: aspartate transaminase, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, cTnT: cardiac troponin T, WBC: white blood cell, PLT: platelet, MPV: mean platelet volume, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LMWH: low molecular weight heparin, y/n: yes or no, n.m.: not measured.

| Variables | Critically ill COVID-19 (n=110) | Severe COVID-19 (n=66) | Non-COVID-19 severe sepsis (n=32) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (median, IQR) | 67 (59-76) * | 61 (52-65) § | 68 (52-75) |

| Sex (M/F) | 68/42 | 39/27 | 21/11 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 10 (5-19) | 8 (6-12) | 9 (5-14) |

| Mechanical ventilation (y/n, %) | 96/14 (87.3) *,# | 6/60 (9.1) § | 20/12 (62.5) |

| SOFA-score | 12 (10-13) * | 4 (3-8) § | 10 (5-11) |

| Horowitz index (P/F) | 103 (71-160) *,# | 147 (89-222) § | 243 (182-384) |

| Mortality (n, %) | 86 (78.2) *,# | 3 (4.5) § | 21 (65.6) |

| CRP (mg/L) (median, IQR) | 173.2 (116.7-256.3) * | 101.9 (34.2-221.6) § | 162.1 (102.0-205.3) |

| PCT (µg/L) | 0.6 (0.26-3.41) *,# | 0.06 (0.05-0.30) § | 9.1 (3.8-26.5) |

| IL-6 (ng/L) | 96.8 (37.8-242) *,# | 35.2 (4.1-63.7) § | 351.9 (47.2-3832.0) |

| Ferritin (µg/L) | 1038 (577.3-1753) * | 648.9 (350.2-950.3) | n.m. |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 112 (80-164) *,# | 88 (73-101) § | 208 (95-335) |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 9.5 (6.5-15.6) * | 5.9 (4.5-7.5) § | 11.5 (7.5-25.6) |

| AST (U/L) | 49 (34-67) * | 37.5 (27.2-49.5) | 44 (23-151) |

| ALT (U/L) | 37 (22-69) | 36 (23-50) § | 30 (15-117) |

| LDH (U/L) | 812 (574-1095) *,# | 545 (385-747) § | 337 (239-486) |

| cTnT (ng/L) | 26.4 (10-105) * | 10 (10-11) | n.m. |

| WBC count (G/L) | 10.2 (6.9-13.9) *,# | 6.9 (5.4-9.6) § | 12.9 (8.1-20.7) |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 129.5 (114-144) *,# | 137.5 (127-149) § | 112 (88-131) |

| PLT count (G/L) | 238 (163-320) # | 224 (155-282) § | 174 (66-225) |

| MPV (fL) | 8.3 (7.6-9.5) *,# | 7.8 (6.9-8.6) § | 11.6 (10.1-12.1) |

| Hypertension (y/n, %) | 98/12 (80.9) *,# | 44/22 (66.7) | 20/12 (62.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 41/69 (37.3) | 19/47 (28.8) | 10/22 (31.2) |

| Cardiac decompensation | 40/70 (36.4) * | 10/56 (15.2) § | 12/20 (37.5) |

| COPD | 21/89 (19.1) | 8/58 (12.1) | 4/28 (12.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 43/67 (39.1) *,# | 8/58 (12.1) § | 9/23 (28.1) |

| Renal insufficiency | 34/76 (30.9) * | 9/57 (13.6) § | 11/21 (34.4) |

| Anti-viral therapy (y/n, %) | 104/6 (94.5) # | 63/3 (95.4) § | 0/32 (0) |

| Azithromycin | 97/13 (88.2) *,# | 22/44 (33.3) § | 0/32 (0) |

| Other antibiotics | 98/12 (89.1) * | 44/22 (66.7) § | 32/0 (100) |

| Corticosteroids | 37/73 (33.6) *,# | 13/53 (19.7) | 5/27 (15.6) |

| Dexamethasone | 97/13 (88.2) *,# | 22/44 (33.3) § | 0/32 (0) |

| LMWH | 79/31 (71.8) *,# | 24/42 (36.4) § | 17/15 (53.1) |

The Horowitz index - as an assessment of overall lung function and oxygenation in patients suffering from life-threatening pulmonary disorders - was calculated in 106 COVID-19 subjects in whom a greater degree of respiratory distress was indicated. Consequently, critically ill COVID-19 patients (with severe ARDS) showed significantly lower values of Horowitz index (103 [71-160] mmHg) compared to severe cases (147 [89-222] mmHg, P < 0.0001), while non-COVID-19 septic subjects had mild/moderate pulmonary disorders based on this index (243 [182-384] mmHg) (Table 1).

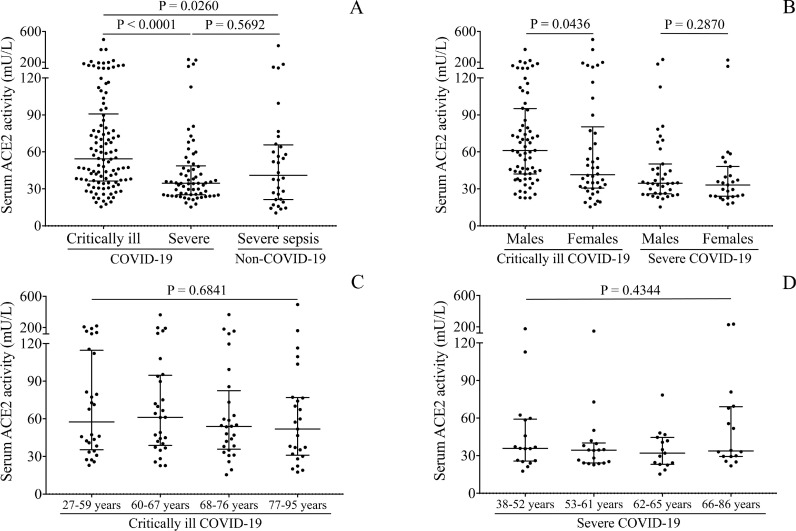

Correlation between baseline ACE2 activity and the severity of COVID-19

First, we determined serum ACE2 activity of COVID-19 patients upon hospitalization. ACE2 activity was significantly higher in critically ill (54.4 [36.7-90.8] mU/L) than in severe COVID-19 subjects (34.5 [25.2-48.7] mU/L, P < 0.0001) and in non-COVID-19 severe sepsis (40.9 [21.4-65.7] mU/L; P = 0.0260) regardless of comorbidities (Figure 1 A). The direct effect of sex and age on soluble ACE2 levels was investigated in the COVID-19 cohort. ACE2 was significantly higher in males than females among critically ill patients (P = 0.0436), while this difference could not be seen among severe subjects (P = 0.2870) (Figure 1B). There was a tendency for higher ACE2 activity with increasing age (P = 0.0134) regardless of disease severity (Suppl. Figure 1B). However, when this association was separately analyzed within the two severity groups, this trend was not found in either cohort (P = 0.6841 and P = 0.4344, respectively), suggesting that disease severity but not age modulated serum ACE2 levels (Figures 1C and D). Also, when Spearman's test was used to analyze the correlation between baseline ACE2 and age, no relationship was found (r = 0.074, P = 0.3279) (data not shown). We then studied the correlation between circulating ACE2 activity and the levels of routinely available laboratory tests suggesting a link between the elevated expression of ACE2 and systemic inflammation causing cardiac, liver, and kidney disorders in COVID-19 (Suppl. Table 1). Based on these results, serum ACE2 activity is strongly associated with the severity of COVID-19, although it is not specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Figure 1.

Comparison of baseline serum ACE2 activity in COVID-19 patients based on disease severity in contrast to non-COVID-19 severe septic subjects. Significantly higher baseline level of ACE2 was measured in critically ill (n=110) vs severe COVID-19 subjects (n=66), while significantly lower values were found in subjects with non-COVID-19 sepsis (n = 32) than critically ill COVID-19 (A). There were higher ACE2 levels in severe male than female subjects, however, sex did not influence ACE2 in the non-severe cohort (B). Age affected ACE2 activity in neither critically ill (C) nor severe COVID-19 (D). Dots represent single results, while bars indicate medians with IQR. To compare the data of two groups, Mann-Whitney U test was applied, while more than two subcohorts were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test.

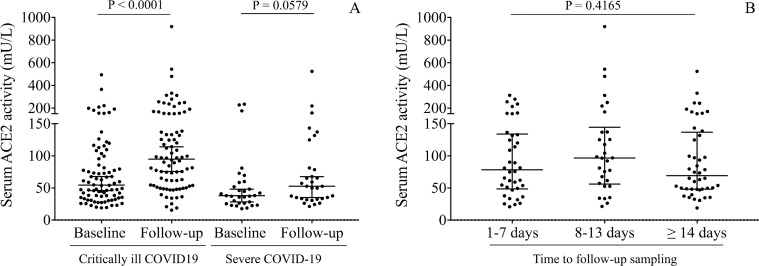

Changes in ACE2 activity among critically ill vs. severe COVID-19 clinical conditions

Serum ACE2 activities were determined not only in baseline samples but were followed in a subgroup of recruited critically ill and severe patients to study the kinetics of ACE2 activity depending on COVID-19 severity. We found that, when compared to baseline levels, ACE2 activities were further elevated during the hospital treatment of critically ill patients (P < 0.0001), in contrast to severely ill study participants in whom alterations did not reach statistical significance during hospital stay (P = 0.0579) (Figure 2 A). Moreover, similarly abnormal ACE2 activity values (P = 0.4165) were found at the admission and subsequent time intervals (Figure 2B). Overall, these data imply that ACE2 expression is sustainedly induced under severe COVID-19 conditions, particularly in critically ill patients.

Figure 2.

Kinetics in serum ACE2 activity between baseline and follow-up sample in critically ill and severe COVID-19 patients. Compared to baseline levels, ACE2 activity was further elevated in the follow-up samples (n = 106), especially in critically ill patients compared to non-severe study participants (A). Based on the time point of the follow-up sampling, similarly abnormal ACE2 activity values were analyzed in the early (1-7 days) and subsequent time intervals (8-13 days and ≥ 14 days, respectively) (B). Dots represent single results, while bars indicate median with IQR. To compare the data of two groups, Mann-Whitney U test was applied, while ACE2 values in baseline and follow-up samples were analyzed with each other by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test.

Association between serum ACE2 and the outcome of COVID-19

Serum ACE2 was analyzed as to whether this biomarker showed any association with disease outcome. Accordingly, non-survivors demonstrated significantly higher ACE2 activities (54.6 [37.3-94.7] mU/L) at hospital admission than survivors (35.6 [25.3-58.5] mU/L (P < 0.0001, Figure 3 A). Next hypothetical differences in patients’ ACE2 activities were further contrasted between initial and follow-up serum samples, depending on individual outcomes. In this context, most (both critically ill and severe) patients who finally died of COVID-19 showed significant ACE2 elevations (P < 0.0001) before death, while no significant change (P = 0.0623) in ACE2 activities were observed in survivors before discharge from the hospital (Figures 3B and C). According to these results, there is a strong association between the level of ACE2 and the clinical consequences of COVID-19 disease.

Figure 3.

The association between baseline ACE2 and the outcome of COVID-19. There was a significant difference in ACE2 activity between the groups of survivors (n = 87) and non-survivors (n = 89) (A). When alteration in ACE2 was selectively studied during the follow-up regarding the outcome of these cases (n = 106), a significant increment in ACE2 between the baseline and follow-up sample was detected in those who died of COVID-19 (n = 68) (B) compared to those with only a modest ACE2 change who recovered after treatment (n = 38) (C). Dots represent single results, while bars indicate median with IQR. In parts B and C, lines connect ACE2 values measured in baseline and follow-up samples. To compare the data of two groups, Mann-Whitney U test was applied.

Suitability of initial ACE2 to predict the severity and outcome of COVID-19

To further investigate initial ACE2 in predicting the severity and outcome of COVID-19 disease, ROC-curve analyses were performed. The best discriminative threshold of ACE2 at admission, estimated by the Youden-index, was 45.4 mU/L with a sensitivity of 60% and specificity of 71.2% to estimate disease severity at an AUC value of 0.701 (95% CI [0.621-0.781], P < 0.0001) (Figure 4 A). Using the same cut-off value, ACE2 could predict the mortality with a sensitivity of 61.8% and specificity of 65.5% at a similar AUC value of 0.679 (95% CI [0.600-0.759], P < 0.0001) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

ROC-curve analysis for serum ACE2 levels (A, B) and Horowitz index (C, D) for the prediction of the severity and outcome of COVID-19 disease. The best discriminative cut-off value of ACE2 at admission was 45.4 mU/L with a sensitivity of 60% and specificity of 71.2% to estimate disease severity (A). Using the same cut-off value, ACE2 could predict the outcome of the disease with a sensitivity of 61.8% and specificity of 65.5% (B). In parallel, the F/P ratio was analyzed for these aspects, and 129 mmHg was the cut-off value of Horowitz index that could be used for the assessment of disease severity (C) and to predict the outcome of the disease with a sensitivity of 65.8% and specificity of 61.5% (D). ROC-AUC values with P-values were determined during all calculations.

A logistic regression analysis was performed to test whether ACE2 can independently predict the severity of the disease. Higher initial ACE2 activity had a significantly higher odds ratio for a more severe outcome (OD: 1.032, 95% CI [1.005-1.061], P = 0.019). Also, ferritin, creatinine, WBC count, lymphocyte count, hemoglobin, and MPV showed statistically significant OD in predicting COVID-19 severity (Table 2 ). Taken together, these data indicate that serum ACE2 activity has the capacity to predict the development of adverse clinical events in COVID-19.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis for testing ACE2 levels to individually predict the severity of COVID-19. All confounds, such as demographical, anamnestic and laboratory parameters were considered for this calculation. Baseline ACE2 had a significant odds ratio (OD) in this regard. Also, ferritin, creatinine, WBC count, lymphocyte (LY) count, hemoglobin, and MPV showed a statistically significant OD in the prediction of COVID-19 severity based on the data from these patients. Abbreviations: CRP: C-reactive protein, PCT: procalcitonin, IL-6: interleukin-6, AST: aspartate transaminase, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, cTnT: cardiac troponin T, WBC: white blood cell, Hgb: hemoglobin, PLT: platelet, MPV: mean platelet volume,

| Variables | Odds ratio | CI (95%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.079 | 0.995-1.169 | 0.064 |

| Sex | 1.889 | 0.325-10.958 | 0.478 |

| ACE2 | 1.032 | 1.005-1.061 | 0.019 |

| CRP | 0.997 | 0.998-1.005 | 0.462 |

| PCT | 1.214 | 0.859-1.717 | 0.272 |

| IL-6 | 1.007 | 0.995-1.020 | 0.233 |

| Ferritin | 0.998 | 0.997-0.999 | 0.005 |

| Creatinine | 1.012 | 1.002-1.023 | 0.018 |

| Urea | 0.966 | 0.900-1.037 | 0.345 |

| AST | 1.033 | 0.987-1.081 | 0.160 |

| LDH | 1.003 | 0.999-1.007 | 0.072 |

| cTnT | 0.999 | 0.998-1.001 | 0.526 |

| WBC count | 1.759 | 1.254-2.467 | 0.001 |

| LY count | 0.013 | 0.009-0.178 | 0.001 |

| Hgb | 1.075 | 1.011-1.144 | 0.021 |

| PLT count | 1.004 | 0.993-1.015 | 0.460 |

| MPV | 4.741 | 1.781-12.622 | 0.002 |

Horowitz index in COVID-19 and its relationship with ACE2 levels

As we described above, the values of the P/F ratio in patients with critically ill clinical conditions were significantly lower (P = 0.0306) compared to moderate COVID-19 cases (see Table 1). This index was also analyzed regarding the outcome of the disease; non-survivors had a significantly decreased P/F ratio vs. survivors (100.5 [66.3-160] vs. 142 [90.7-200.3] mmHg, P = 0.0180). The diagnostic characteristics of the P/F ratio were further studied by using ROC-curve analysis. Its best discriminative threshold was 129 mmHg with a sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 64.8% for the assessment of disease severity at an AUC value of 0.662 (95% CI [0.522-0.802], P = 0.0312) (Figure 4C). Using the same cut-off value, ACE2 predicted the outcome of the disease with a sensitivity of 65.8% and specificity of 61.5% at an AUC value of 0.653 (95% CI [0.539-0.767], P = 0.0196) (Figure 4D). Surprisingly, when ACE2 levels were correlated with the values of Horowitz index, no relationship was observed between the two parameters (in the entire group: r = 0.045, P = 0.6417; within the critically ill subgroup: r = 0.0342, P = 0.7517). According to these preliminary results, the Horowitz index is suitable to monitor COVID-19 with lung function disorders, although lacking a direct association with the expression of ACE2.

Prediction of 30-day mortality by high initial ACE2 level in patients with COVID-19

Out of the 176 COVID-19 patients, 89 (50.6%) died during the 30-day follow-up. In Figure 3A, there was a significant difference in baseline ACE2 activity between survivors and non-survivors, and this biomarker predicted the outcome based on ROC analysis (Figure 4B). Using the derived cut-off value in Kaplan-Meier analysis, COVID-19 patients with highly elevated ACE2 levels (≥ 45.4 mU/L) had a greater risk for 30-day mortality when compared to those with lower ACE2 activity (37.2% vs. 64.7%, Log-Rank P < 0.0001) (Figure 5 ). Overall, the measurement of ACE2 at admission can be considered a useful novel biomarker to predict COVID-19 progression and mortality.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier analysis indicates that highly elevated ACE2 levels were related to a higher rate of short-term mortality. Cut-off value (≥ 45.4 mU/L) was determined by the ROC-curve analysis. There is a lower risk of death for those COVID-19 subjects who had less than 45.4 mU/L of ACE2 level before any treatment. Number of patients at risk are displayed at given days. Log Rank P value was determined.

Discussion

ACE2 is a functional receptor for the fusion and endocytosis of SARS-CoV-2 into the pulmonary endothelium via the interaction of the virus spike-protein to the membrane-bound ACE2 (Hoffmann et al. 2020; Wenzel et al. 2021). On the surface of endothelial cells, the protease ADAM17 sheds ACE2 into its soluble form (Gheblawi et al. 2020). Typically, the circulating level of ACE2 is low (< 17 mU/L) (Úri et al. 2016; Fagyas et al. 2021 Oct 21) but becomes elevated in various cardiovascular disorders, such as hypertension (Úri et al. 2016), aortic stenosis (Fagyas et al. 2021), heart failure (Fagyas et al. 2021 Oct 21) and atrial fibrillation (Wallentin et al. 2020). These data suggest that elevated baseline ACE2 in the circulation may predispose to severe COVID-19, and SARS-CoV-2 infection can further increase ACE2 activity (Montanari et al., 2021). Despite these facts, controversial results on ACE2 level and activity have recently been published in different cohorts of COVID-19 patients ranging from (highly) elevated (Nagy et al. 2021; van Lier et al. 2021; Kragstrup et al. 2021; Kaur et al. 2021; Patel et al. 2021; Reindl-Schwaighofer et al. 2021) to unchanged (Rieder et al. 2021; Kintscher et al. 2020) or even lowered circulating ACE2 levels (Rojas et al. 2021) vs. controls. Since the early diagnosis and effective clinical monitoring of COVID-19 disease are essential to prevent severe consequences or death (Borges do Nascimento et al. 2020), that is why the discovery and validation of novel blood-based biomarkers in COVID-19 are deemed necessary. For instance, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) were tested as new predictors of COVID-19 severity (Henry et al., 2021).

Here we conducted a retrospective, dual-center clinical study to compare baseline serum ACE2 activity in a large group of critically ill and severe COVID-19 patients (Table 1). There was an age difference, as critically ill patients were older than those with moderate symptoms, which may be related to the fact that increasing age can predispose a more severe progression of COVID-19 with higher ACE2 levels (Zhou et al. 2020). Routinely available laboratory tests detected a higher level of systemic inflammation in critically ill compared to severe COVID-19 conditions, in agreement with the findings of large clinical studies (Zhou et al. 2020; Huang et al. 2020). However, no severe thrombocytopenia developed in this study cohort in contrast to recently reported COVID-19 cases (Lippi et al. 2020; Martincic et al. 2020).

To evaluate overall lung function and oxygenation, the Horowitz index was determined in 106 patients by the clinicians. The P/F ratio drew attention to a greater degree of respiratory distress via significantly lower values of participants in the severe group compared to moderate clinical cases (Table 1). To the best of our knowledge, there is only one publication where the P/F ratio has been analyzed in combination with other variables in COVID-19 patients, to develop a rapid clinical indicator of adverse outcomes in making decisions (Lagolio et al. 2021). In our study, the Horowitz index was associated with the outcome of COVID-19 as significantly lower values were found in non-survivors than survivors (Table 1). Surprisingly, pulmonary performance did not correlate with circulating ACE2 activity.

Serum ACE2 activity in COVID-19 patients was measured upon hospitalization. There were significantly larger initial ACE2 activities in critically ill patients compared to severe COVID-19 subjects. These values were highly elevated compared to serum ACE2 levels formerly measured in healthy individuals (16.2 ± 0.8 mU/L) (Úri et al. 2016). Recently, similar results were reported on COVID-19 severity and the degree of ACE2 alteration (Patel et al. 2021; Reindl-Schwaighofer et al. 2021). To further investigate the suitability of initial ACE2 in predicting the severity of COVID-19 disease, ROC-curve analyses were performed. The best discriminative threshold of ACE2 at admission was 45.4 mU/L to estimate disease severity at a substantial AUC value of 0.701 (95% CI [0.621-0.781]). As controls, non-COVID-19 severe septic patients were recruited. They had similarly elevated serum ACE2 activities as patients with severe COVID-19. Likewise, patients having influenza with similar disease severity to severe COVID-19 subjects demonstrated upregulated ACE2 protein levels (Reindl-Schwaighofer et al., 2021). Accordingly, enhanced ACE2 activity cannot be considered as a disease-specific marker for COVID-19. However, its level strongly correlates with COVID-19 severity and predicts disease prognosis and mortality.

The impact of age and sex was investigated on circulating ACE2, and there was a tendency for increasing ACE2 activity with increasing age. However, when this association was separately analyzed within the two severity groups, this trend was not found in either cohort. Hence, disease severity but not age directly modulated serum ACE2 levels. In contrast, others found a strong relationship between ACE2 and age (Kragstrup et al., 2021). Male patients demonstrated higher baseline ACE2 levels than females in the entire study cohort, predominately in the critically ill group in this study. This agrees with recent findings with lower ACE2 activity in females than males (Kaur et al. 2021; Reindl-Schwaighofer et al. 2021). The relationship between initial ACE2 and pre-existing cardiovascular or other comorbidities was then studied, and surprisingly, no significant association was shown in COVID-19 patients with hypertension, atrial fibrillation, cardiac decompensation, renal disorder, diabetes mellitus, and COPD.

In contrast, Kragstup et al. found an elevation in ACE2 levels in those who previously suffered from hypertension, heart, and renal disorders (Kragstrup et al. 2021), and diabetes was also associated with higher ACE2 concentrations (Reindl-Schwaighofer et al. 2021). Others reported higher ACE2 activity in smokers than non-smokers (Kaur et al., 2021). Initially, ACE2 moderately correlated with inflammation-dependent parameters in this study, such as CRP, IL-6, ferritin, and WBC count. Similarly, IL-6 concentrations were correlated with ACE2 levels (Reindl-Schwaighofer et al. 2021), while PAI-1 and tPA were associated with inflammatory markers with identical AUC values to ours in COVID-19 (Henry et al. 2021). On the other hand, ACE2 did not correlate with IL-6 and TNF-α in another study (Lundström et al., 2021).

Next, serum ACE2 activity in follow-up blood samples was determined in order to study the kinetics of ACE2 activity dependent on COVID-19 severity. Initial serum ACE2 activity was further elevated in the follow-up samples, especially in critically ill patients. Based on the timing of the follow-up sampling, no marked difference was observed in ACE2 activity at early and subsequent time points. Our data are in accordance with a recent study showing persistent ACE2 activity following SARS-CoV-2 infection (Patel et al., 2021). In contrast, acute phase soluble ACE2 levels increased with symptom duration but were reduced after four months of the clinical course (Lundström et al., 2021).

Finally, initial ACE2 was analyzed if it showed any association with the disease outcome. Non-survivors demonstrated significantly higher ACE2 activity before any treatment vs. survivors based on the data of all patients. Also, ACE2 could predict the outcome of the disease at an AUC value of 0.679 (95% CI [0.600-0.759]). A comparable AUC value was seen for initial ACE2 to indicate clinical outcomes (Kragstrup et al., 2021). Furthermore, most patients who finally died of COVID-19 still showed significant ACE2 elevation before death, while no significant increase in ACE2 was observed before discharge in survivors. Notably, COVID-19 patients with ≥ 45.4 mU/L ACE2 level had a greater risk for 30-day mortality when compared to those with lower ACE2 activity. Likewise, elevated plasma ACE2 was associated with the maximal severity in COVID-19 positive individuals during 28 days follow up (Kragstrup et al., 2021). Increased complement activation was also associated with advanced COVID-19 disease severity. Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection were more likely to die when the disease was accompanied by overactivation and consumption of C3 (Sinkovits et al., 2021).

In conclusion, serum ACE2 activity at hospital admission correlates with COVID-19 severity and predicts mortality, independently of pulmonary function (Horowitz index). It appears that serum ACE2 is a non-specific biomarker in systemic inflammation, since it is also elevated in severe sepsis. Further clinical studies are required to monitor serum ACE2 levels in post-COVID-19 survivors for a longer period.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00043 and GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00050 (these projects are co-financed by the European Union and the European Regional Development Fund) and EFOP-3.6.2-16-2017-00006 (this project is co-financed by the European Union and the European Social Fund) projects, grants from the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (FK 128809 to MF, FK 135327 to BN and K 132623 to AT). The research was financed by the Thematic Excellence Program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology in Hungary (TKP2020-IKA-04 and TKP2020-NKA-04), within the framework of the thematic program of the University of Debrecen. MP and MF were supported by the ÚNKP-21-3-I-DE-255 and ÚNKP-21-5-DE-458 New National Excellence Program of The Ministry for Innovation and Technology, respectively. This paper was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (BO/00069/21/5). No funding source had any role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit.

Declaration of Competing Interest

There are no competing interests to declare among the authors of this work.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of the University of Debrecen and the Ministry of Human Capacities under the registration number 32568-3/2020/EÜIG.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.11.028.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Borges do Nascimento IJ, von Groote TC, O'Mathúna DP, Abdulazeem HM, Henderson C, Jayarajah U, Weerasekara I, Poklepovic Pericic T, Klapproth HEG, Puljak L, Cacic N, Zakarija-Grkovic I, Guimarães SMM, Atallah AN, Bragazzi NL, Marcolino MS, Marusic A, Jeroncic A, International Task Force Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19) Clinical, laboratory and radiological characteristics and outcomes of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection in humans: A systematic review and series of meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escher R, Breakey N, Lämmle B. Severe COVID-19 infection associated with endothelial activation. Thromb Res. 2020;190:62. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagyas M, Kertész A, Siket IM, Bánhegyi V, Kracskó B, Szegedi A, Szokol M, Vajda G, Rácz I, Gulyás H, Szkibák N, Rácz V, Csanádi Z, Papp Z, Tóth A, Sipka S. Level of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 activity is highly elevated in old-aged patients with aortic stenosis: implications for ACE2 as a biomarker for the severity of COVID-19. Geroscience. 2021;43:19–29. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00300-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagyas M, Bánhegyi V, Úri K, Enyedi A, Lizanecz E, Mányiné IS, Mártha L, Fülöp GÁ, Radovits T, Pólos M, Merkely B, Kovács Á, Szilvássy Z, Ungvári Z, Édes I, Csanádi Z, Boczán J, Takács I, Szabó G, Balla J, Balla G, Seferovic P, Papp Z, Tóth A. Changes in the SARS-CoV-2 cellular receptor ACE2 levels in cardiovascular patients: a potential biomarker for the stratification of COVID-19 patients. Geroscience. 2021 Oct 21:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00467-2. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvin MR, Alvarez C, Miller JI, Prates ET, Walker AM, Amos BK, Mast AE, Justice A, Aronow B, Jacobson D. A mechanistic model and therapeutic interventions for COVID-19 involving a RAS-mediated bradykinin storm. Elife. 2020;9:e59177. doi: 10.7554/eLife.59177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheblawi M, Wang K, Viveiros A, Nguyen Q, Zhong JC, Turner AJ, Raizada MK, Grant MB, Oudit GY. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 Receptor and Regulator of the Renin-Angiotensin System: Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Discovery of ACE2. Circ Res. 2020;126:1456–1474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry BM, Cheruiyot I, Benoit JL, Lippi G, Prohászka Z, Favaloro EJ, Benoit SW. Circulating Levels of Tissue Plasminogen Activator and Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Are Independent Predictors of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Severity: A Prospective, Observational Study. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2021;47(4):451–455. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1722308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. 271-80.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G, Yogeswaran S, Muthumalage T, Rahman I. Persistently Increased Systemic ACE2 Activity Is Associated With an Increased Inflammatory Response in Smokers With COVID-19. Front Physiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.653045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintscher U, Slagman A, Domenig O, Röhle R, Konietschke F, Poglitsch M, Möckel M. Plasma Angiotensin Peptide Profiling and ACE (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme)-2 Activity in COVID-19 Patients Treated With Pharmacological Blockers of the Renin-Angiotensin System. Hypertension. 2020;76:e34–e36. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragstrup TW, Singh HS, Grundberg I, Nielsen AL, Rivellese F, Mehta A, Goldberg MB, Filbin MR, Qvist P, Bibby BM. Plasma ACE2 predicts outcome of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagolio E, Demurtas J, Buzzetti R, Cortassa G, Bottone S, Spadafora L, Cocino C, Smith L, Benzing T, Polidori MC. A rapid and feasible tool for clinical decision making in community-dwelling patients with COVID-19 and those admitted to emergency departments: the Braden-LDH-HorowITZ Assessment-BLITZ. Intern Emerg Med. 2021:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11739-021-02805-w. Jul 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundström A, Ziegler L, Havervall S, Rudberg AS, von Meijenfeldt F, Lisman T, Mackman N, Sandén P, Thålin C. Soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is transiently elevated in COVID-19 and correlates with specific inflammatory and endothelial markers. J Med Virol. 2021;93:5908–5916. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martincic Z, Skopec B, Rener K, Mavric M, Vovko T, Jereb M, Lukic M. Severe immune thrombocytopenia in a critically ill COVID-19 patient. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;99:269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanari M, Canonico B, Nordi E, Vandini D, Barocci S, Benedetti S, Carlotti E, Zamai L. Which ones, when, and why should renin-angiotensin system inhibitors work against COVID-19? Adv Biol Regul. 2021;81 doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2021.100820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy B, Jr, Fejes Z, Szentkereszty Z, Sütő R, Várkonyi I, Ajzner É, Kappelmayer J, Papp Z, Tóth A, Fagyas M. A dramatic rise in serum ACE2 activity in a critically ill COVID-19 patient. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:412–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SK, Juno JA, Lee WS, Wragg KM, Hogarth PM, Kent SJ, Burrell LM. Plasma ACE2 activity is persistently elevated following SARS-CoV-2 infection: implications for COVID-19 pathogenesis and consequences. Eur Respir J. 2021;57 doi: 10.1183/13993003.03730-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz Ocaranza M, Riquelme JA, García L, Jalil JE, Chiong M, Santos RA, Lavandero S. Counter-regulatory renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:116–129. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranieri VM, Gordon D, Rubenfeld GD, B Taylor Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder M, Wirth L, Pollmeier L, Jeserich M, Goller I, Baldus N, Schmid B, Busch HJ, Hofmann M, Kern W, Bode C, Duerschmied D, Lother A. Serum ACE2, Angiotensin II, and Aldosterone Levels Are Unchanged in Patients With COVID-19. Am J Hypertens. 2021;34:278–281. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpaa169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reindl-Schwaighofer R, Hödlmoser S, Eskandary F, Poglitsch M, Bonderman D, Strassl R, Aberle JH, Oberbauer R, Zoufaly A, Hecking M. ACE2 Elevation in Severe COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:1191–1196. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202101-0142LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas M, Acosta-Ampudia Y, Monsalve DM, Ramírez-Santana C, Anaya JM. How Important Is the Assessment of Soluble ACE-2 in COVID-19? Am J Hypertens. 2021;34:296–297. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpaa178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkovits G, Mező B, Réti M, Müller V, Iványi Z, Gál J, Gopcsa L, Reményi P, Szathmáry B, Lakatos B, Szlávik J, Bobek I, Prohászka ZZ, Förhécz Z, Csuka D, Hurler L, Kajdácsi E, Cervenak L, Kiszel P, Masszi T, Vályi-Nagy I, Prohászka Z. Complement Overactivation and Consumption Predicts In-Hospital Mortality in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.663187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Úri K, Fagyas M, Siket IM, Kertész A, Csanádi Z, Sándorfi G, Clemens M, Fedor R, Papp Z, Édes I, Tóth A, Lizanecz E. New Perspectives in the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) IV: Circulating ACE2 as a Biomarker of Systolic Dysfunction in Human Hypertension and Heart Failure. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Úri K, Fagyas M, Kertész A, Borbély A, Jenei C, Bene O, Csanádi Z, Paulus WJ, Édes I, Papp Z, Tóth A, Lizanecz E. Circulating ACE2 activity correlates with cardiovascular disease development. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2016;17 doi: 10.1177/1470320316668435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lier D, Kox M, Santos K, van der Hoeven H, Pillay J, Pickkers P. Increased blood angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity in critically ill COVID-19 patients. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7:00848–02020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00848-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallentin L, Lindbäck J, Eriksson N, Hijazi Z, Eikelboom JW, Ezekowitz MD, Granger CB, Lopes RD, Yusuf S, Oldgren J, Siegbahn A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) levels in relation to risk factors for COVID-19 in two large cohorts of patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:4037–4046. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel UO, Kintscher U. ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2: Tissue or Plasma, Good or Bad? Am J Hypertens. 2021;34:274–277. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpaa175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.