Abstract

Sapporo-like viruses (SLVs) are associated with acute gastroenteritis in humans. Due to a limited supply of available reagents for diagnosis, little is known about the incidence and pathogenicity of these viruses. We have developed a first-generation generic reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR assay based on a single primer pair targeting the RNA polymerase gene. With this assay, 55 (93%) of the 59 stool specimens collected in a 10-year period of time (1988 to 1998) and containing typical caliciviruses by electron microscopy tested positive and could be confirmed by Southern hybridization. By phylogenetic analysis, most SLV strains could be classified into one of the three recently described genotypes. However, three samples clustered separately, forming a potential new genotype. We sequenced the complete capsid gene of one of the strains in this cluster: Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE. Alignment of the capsid sequences showed 40 to 74% amino acid identity among strains of the different clusters. Phylogenetic analysis of the aligned sequences confirmed the placing of Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE into a new distinct genetic cluster. This is the first report on the development of a broadly reactive RT-PCR assay for the detection of SLVs.

Human caliciviruses are a major cause of acute gastroenteritis in persons of all ages worldwide (11, 21). These viruses can phylogenetically be divided into three genetic groups, with genogroup I and II viruses representing the Norwalk-like viruses (NLVs) (also known as small round-structured viruses) and genogroup III or Sapporo-like viruses (SLVs) representing the group of typical human caliciviruses (24). Apart from their characteristic surface morphology, SLVs also differ epidemiologically from NLVs by causing symptomatic infections predominantly in infants and young children (5, 19, 20), although outbreaks of gastroenteritis in older people have been described (22). As both an in vitro culture system and an animal model are lacking for these viruses, studies of the molecular epidemiology of SLVs have been difficult due to limited supplies of diagnostic reagents; as a result, little is known about the real incidence and pathogenicity of these viruses.

Recently, one complete and several partial sequences have been determined for eight different strains of SLVs (2, 14, 17, 18, 22, 23, 30). Phylogenetically, these strains can be divided into at least three different genetic clusters or genotypes represented by Sapporo virus, London virus, and Parkville virus. These genetic differences are partly associated with antigenic differences (14). Moreover, it was shown clearly that SLV capsid sequences are less conserved than polymerase sequences, with at least up to 56% difference at the amino acid level, compared with 28% in a conserved region of the polymerase encompassing the GLPSG and YGDD motifs (14). For comparison, for NLV, differences of up to 62 and 42% have been found for the capsid protein and a comparable region of the RNA polymerase, respectively (9). Despite these differences, several groups have succeeded in developing generic primers for the detection of NLVs by reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR (1, 8, 12, 15, 27, 31). Hence, given the current knowledge of the genome sequence of SLVs, we chose the RNA polymerase gene as a target region for the development of a generic RT-PCR assay for diagnostic use.

In this paper, we report the development and evaluation of a first-generation generic RT-PCR assay that detects all known genotypes of SLVs. In addition, we describe the cloning and sequencing of the complete capsid gene of a new distinct genotype within the SLV genus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Stool samples.

A panel of 59 stool samples containing typical caliciviruses, as determined by electron microscopy (EM) (Fig. 1), and nine specimens containing other enteric viruses (four different genotypes of NLVs, adenoviruses [type 40 and 41], group A rotaviruses [serotypes 1 and 2], and human astrovirus serotype 1) were used in this study. From this panel, 31 SLV-positive stool samples were used to evaluate different primer pairs (Table 1). The typical calicivirus-positive specimens were collected over a 10-year period of time (1988 to 1998); 38 specimens were from hospitalized people, 6 specimens were from people with community-acquired gastroenteritis, and 15 specimens were from outbreaks. All but seven samples for which the age of the patient had been indicated originated from children less than 5 years old and were submitted for diagnostic purposes to the Public Health Laboratory Services (Leeds, United Kingdom), the Karolinska Institute (Solna, Sweden), or the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (Bilthoven, The Netherlands) (other enteric viruses). The strain used to clone the viral capsid gene was identified in a diarrheal specimen from a 59-year-old man involved in an outbreak of acute gastroenteritis and was designated Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE.

FIG. 1.

Electron micrograph of typical calicivirus particles in a stool specimen. Bar, 50 nm.

TABLE 1.

Description, epidemiological findings, and RT-PCR diagnosis of a panel of 59 stool samples found positive for typical caliciviruses by EMa

| Strain | Settingb | Type of casec | Patient age | RT-PCR result with the following primer pair:

|

SLV genotyped | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NV35-NV36 | JV2-JV3 | SR33-SR80 | JV33-SR80 | |||||

| 1 | H | SP | 17 mo | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 2 | H | SP | 12 mo | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 3 | Com | SP | Unknown | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 4 | H | SP | 6 yr | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 5 | H | SP | 2 yr | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 6 | H | SP | 3 mo | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 7 | Com | SP | 2 yr | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | LON |

| 8 | Com | SP | 4 yr | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 9 | Com | SP | 2 yr | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | LON |

| 10 | H | SP | 2 yr | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | PAR |

| 11 | H | SP | 3 mo | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 12 | DCC | OB | 10 mo | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 13 | DCC | OB | 9 mo | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 14 | DCC | OB | 1 yr | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 15 | DCC | OB | 7 mo | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 16 | H | SP | 1 yr | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 17 | Com | SP | 10 mo | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos | LON |

| 18 | H | SP | 2 mo | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 19 | H | SP | 7 mo | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 20 | H | SP | Unknown | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | PAR |

| 21 | H | SP | 7 mo | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | PAR |

| 22 | H | SP | 1 yr | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | SAP |

| 23 | H | SP | 2 yr | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | LON |

| 24 | H | SP | 9 mo | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 25 | H | SP | 9 mo | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | SAP |

| 26 | H | SP | 3 yr | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | SAP |

| 27 | H | SP | 1 yr | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 28 | H | SP | 3 mo | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 29 | DCC | OB | 10 mo | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 30 | Com | SP | 8 mo | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 31 | H | SP | 6 mo | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | LON |

| 32 | Nursery | OB | <5 yr | Pos | LON | |||

| 33 | Nursery | OB | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 34 | Nursery | OB | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 35 | Nursery | OB | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 36 | Nursery | OB | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 37 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 38 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 39 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | LON | |||

| 40 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 41 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 42 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 43 | Adult ward | OB | Unknown | Pos | SAP | |||

| 44 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | LON | |||

| 45 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 46 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 47 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 48 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 49 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | STO | |||

| 50 | H | SP | <5 yr | Neg | ||||

| 51 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | SAP | |||

| 52 | H | SP | <5 yr | Pos | LON | |||

| 53 | Reception | OB | 63 yr | Neg | ||||

| 54 | Reception | OB | 66 yr | Neg | ||||

| 55 | Reception | OB | 66 yr | Neg | ||||

| 56 | H | SP | 1 yr | Pos | LON | |||

| 57 | Food borne | OB | 59 yr | Pos | STO | |||

| 58 | H | H | 30 yr | Pos | STO | |||

| 59 | H | H | 77 yr | Pos | LON | |||

Strains 1 to 31 were used for evaluating different primer pairs, and all strains (strains 1 to 59) were used for evaluating primer pair JV33-SR80. Of the first 31 strains, 4 (13%), 19 (61%), 25 (81%), and 31 (100%) were positive with NV35-NV36, JV2-JV3, SR33-SR80, and JV33-SR80, respectively.

H, hospital inpatients; Com, community; DCC, day-care center.

SP, sporadic cases; OB, outbreak.

Based on phylogenetic analysis; see also Fig. 2B. LON, London, SAP, Sapporo; PAR, Parkville; STO, Stockholm.

RNA extraction.

Viral RNA was extracted by binding to size-fractionated silica particles (Sigma, Roosendaal, The Netherlands) in the presence of guanidinium (iso)thiocyanate (3, 27). After centrifugation (1 min at 13,000 rpm), the pellet was washed twice with a guanidinium (iso)thiocyanate-containing washing buffer, twice with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol, and once with acetone. After removal of acetone by evaporation, the RNA was eluted with 20 μl of distilled water containing 0.1 mM dithiothreitol and RNAguard (250 U/ml) (Pharmacia, Roosendaal, The Netherlands) and was either used directly in RT-PCR or stored at −70°C.

Generation of a sequence database for selection of generic primers.

Three primer combinations (NV35-NV36, JV2-JV3, and SR80-SR33) (Table 2) were used in RT-PCR to amplify fragments of the polymerase gene of SLVs. They were selected from a nucleotide sequence alignment of published SLV RNA polymerase sequences (JV2 and JV3) or chosen from recent publications (NV35, NV36, SR33, and SR80) (1, 22). The RT-PCR assays were optimized for concentrations of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and MgCl2. Specific RT-PCR products were cloned using a TA Cloning Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands). After isolation of recombinant plasmids, the nucleotide sequence of the inserts was determined by cycle sequencing (PE Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk aan de Yssel, The Netherlands). The obtained sequences were edited using SeqEd and aligned using CLUSTAL software with manual correction for alignment of the conserved motifs GLPSG and YGDD.

TABLE 2.

Primers and probes used in this study

| Primer or probe | Orientation | Sequence (5′-3′) | Positions (nucleotides) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NV35 | − | CTT GTT GGT TTG AGG CCA TAT | 4936–4956a | 29 |

| NV36 | + | ATA AAA GTT GGC ATG AAC A | 4487–4505a | 29 |

| JV2 | − | GTC ATC ACC ATA YGT GTG AA | 4655–4674b | This study |

| JV3 | + | GGN CTM CCW TCN GGR ATG CC | 4519–4538b | This study |

| SR33 | − | TGT CAC GAT CTC ATC ATC ACC | 4868–4888a | 1 |

| SR80 | + | TGG GAT TCT ACA CAA AAC CC | 4366–4385b | 22 |

| JV33 | − | GTG TAN ATG CAR TCA TCA CC | 4666–4685b | This study |

| biot-SAP | + | GGC ATA YGA AAG YCA CAA TGT | 4599–4619b | This study |

| biot-LON | + | GCA TGC CAT TCA CYA GTG | 4532–4549b | This study |

| biot-PAR | + | GTC TCC CAT CAG GAA TGC | 4520–4537b | This study |

| biot-STO | + | GAA GAR CAC CAT GCA CCT TA | 4606–4625b | This study |

| Linker-primer | − | TAG TAC ATA GTG GAT CCA GC | 17 | |

| ST01POL | + | CAG TRC TAC AGG CAT ATG AAG | 4589–4609b | This study |

| ST02C | − | CCA CCC GAA CGC GTG TG | 7380–7396b | This study |

| ST03C | + | GCT TGG TTY ATA GGT GGT ACA | 5098–5118b | This study |

Generic SLV RT-PCR.

Based on published sequences and SLV sequences generated in this study, a set of generic primers was developed (SR80-JV33) (Table 2) and used in the RT-PCR format that was recently described for detecting NLVs (28). For reverse transcription, 5 μl of the extracted viral RNA was mixed with 4 μl of 50 pmol of JV33 (Table 2), and the mixture was heated for 2 min at 90°C. After the mixture was quenched on ice for 2 min, 6 μl of RT buffer was added. Reverse transcription was performed with a 15-μl reaction mixture consisting of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dNTPs, and 5 U of avian myeloblastosis virus RT (Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands). The reaction mixture was incubated for 60 min at 42°C. After heat denaturation at 99°C for 5 min, 5 μl of the RT mixture was added to 45 μl of a PCR mixture containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.2), 75 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 2.5 U of AmpliTaq polymerase (PE Biosystems), and a 0.3 μM concentration of each primer (SR80 and JV33) (Table 1). Samples were denatured for 3 min at 94°C and subjected to 40 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 37°C for 1.5 min, and 74°C for 1 min.

Gel electrophoresis and Southern blotting of PCR products.

The PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel (MP agarose; Boehringer, Almere, The Netherlands), stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized with UV light. DNA molecular weight marker V (Roche) was used as a DNA size standard. The PCR products in the agarose gel were denatured in 0.5 M NaOH for 30 min and transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane with a vacuum blotting system (Millipore, Etten-Leur, The Netherlands) (28).

Hybridization of PCR products.

After two washes with 30 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.0)–0.3 M NaCl, the DNA was cross-linked by baking in a magnetron oven for 12 min. Hybridization was performed with a set of three different 5′-biotinylated probes (Table 2) (biot-SAP, biot-LON, and biot-PAR; Isogen, Maarssenbroek, The Netherlands) as described previously (28). The nylon membranes were prehybridized for 15 min at 50°C in a solution of 2× SSPE (300 mM NaCl, 20 mM NaH2PO4 · H2O, 2 mM EDTA [pH 7.4]) and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Ten picomoles of each of the biotin-labeled oligonucleotides was added, and hybridization was performed for 45 min at 50°C, followed by two 10-min washes at 50°C with 2× SSPE–0.1% SDS. The membranes were incubated with 1:4,000-diluted streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals) in 2× SSPE–0.5% SDS for 45 min at 42°C and then washed three times (10 min each) with decreasing concentrations of SDS (0.5, 0.1, and 0%) in 20 ml of 2× SSPE. After the membranes were incubated with ECL detection reagent (Amersham, 's Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's instructions, they were exposed to Amersham ECL hyperfilm for 30 min to visualize bound probe.

Sequence analysis.

RT-PCR products were sequenced using an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Reaction Kit (PE Biosystems). DNA sequences were edited using Seq Ed (version 1.03; Applied Biosystems) (27).

Phylogenetic analysis.

Nucleotide sequences were analyzed using Geneworks (version 2.5; Intelligenetics, Mountain View, Calif.) and imported into the TREECON software package (26) for distance calculation using the Jukes and Cantor correction for evolutionary rate. Evolutionary trees for both nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences were drawn using the UPGMA clustering method. The confidence values of the internal lineages were calculated by performing 100 bootstrap analyses (7).

RT-PCR amplification and cloning of Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE.

RNA was extracted from a 200-μl stool sample from the Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97 outbreak (no. 57 in the panel) using the extraction method of Boom et al. (3). For cDNA synthesis, a T20VN-linker primer (17) and Superscript II RNase H-RT (Life Technologies, Breda, The Netherlands) were used. A 2.2-kb cDNA clone of the 3′ end of the Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97 genome was generated by nested PCR using the Expand Long Template System (Roche) and ST01POL and linker primer (see Table 2) (17) in the first round and ST02C and ST03C in the second round. The primer sequences were selected based on an alignment of known SLV sequences and are given in Table 2. The cDNA was amplified by 35 cycles at 94°C for 10 s, 40°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 3 min with a Perkin-Elmer 9700 Thermocycler. PCR products with the expected size, as determined by agarose gel electrophoresis, were cloned into the TA vector according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). End sequences of the inserted DNA were determined using M13 forward and reverse primers. The remaining sequences were obtained by genomic walking with primers based on newly obtained sequences. All sequences were confirmed by sequencing both strands at least twice.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97 capsid sequence data reported in this study have been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession number AF194182.

RESULTS

Generation of a sequence database and selection of generic primers.

Our first goal was to develop a PCR assay that detects all known SLV types. Therefore, different primer pairs were evaluated for use in a diagnostic RT-PCR assay with RNA extracts from a panel of 31 stool specimens containing typical caliciviruses, as determined by EM (Table 1). The samples were tested in parallel with a generic NLV RT-PCR (28). With the NLV primer pair, no visible products were obtained in the RT-PCR. With the NV35-NV36 primer pair, 4 of the 31 specimens (13%) tested positive for SLV. With JV2-JV3 and SR33-SR80, 19 of the 31 (61%) and 25 of the 31 (81%) tested positive, respectively. In total, 27 RT-PCR products giving a distinct band when analyzed on gels were cloned and sequenced, i.e., 5 products from RT-PCR with primer pair JV2-JV3 and 22 with primer pair SR33-SR80. All sequences contained the conserved motifs GLPSG and YGDD, characteristic of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (4, 25). Based on these novel sequences and published sequences, a generic primer pair (JV33-SR80) and a set of three biotin-labeled probes (biot-SAP, biot-LON, and biot-PAR) (Table 2) were designed.

The SLV RT-PCR with primer pair JV33-SR80 was optimized regarding the MgCl2 and dNTP concentrations. In its present format, 2 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM dNTPs are used in the RT step, and 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.2 mM dNTPs are used in the PCR step.

Evaluation of generic SLV RT-PCR.

A panel of stool specimens containing typical caliciviruses, as determined by EM (n = 59) (Table 1), or other enteric viruses (n = 9) was used for validation of the PCR assay. No Southern hybridization-positive products were obtained when RNA from nine different enteric viruses was used as a template. A total of 55 (93%) of the 59 panel strains gave RT-PCR products of the expected size (320 bp). Except for RT-PCR products from three strains, all products could be confirmed by Southern hybridization with a panel of three probes, each specific for an SLV or genotype: Sapporo/82, Parkville/94, and London/92. Four stool samples, three of which belonged to the same outbreak, tested negative with the JV33-SR80 primer pair.

Genetic diversity of SLV strains.

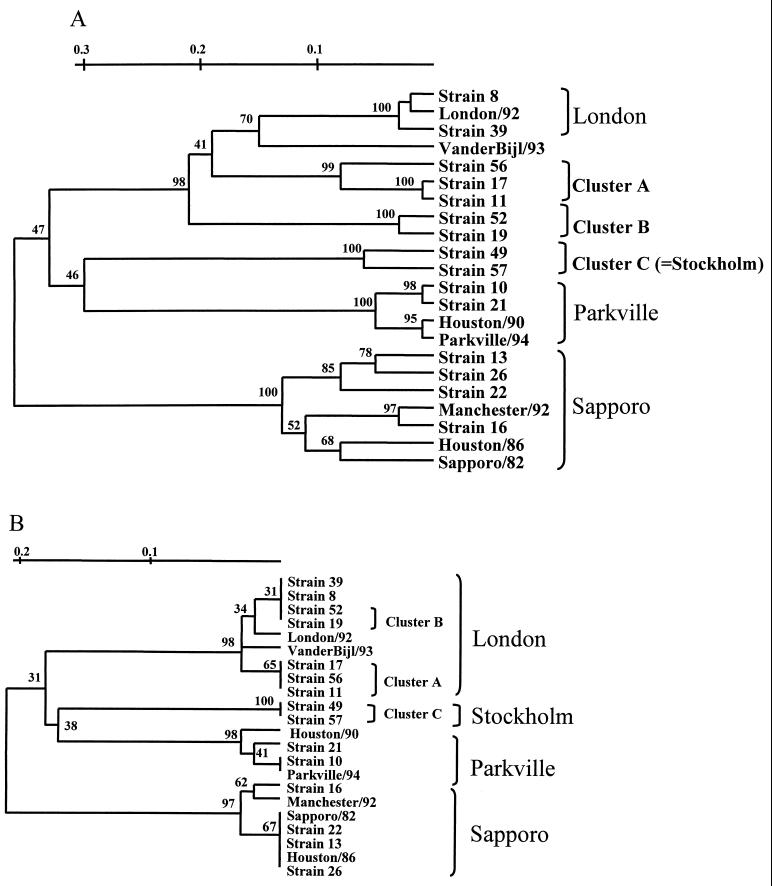

To investigate the genetic variability of SLV strains, we determined the nucleotide sequence of the RNA polymerase region of the 55 positive RT-PCR products either directly or after cloning. For comparison with available sequences from GenBank, we used a 147-nucleotide stretch from 15 strains representative of the observed genetic variability to create a multiple sequence alignment from which a phylogenetic tree was constructed. Most of the strains fell into the three described SLV subgenogroups Sapporo/82, Parkville/94, and London/92 (Fig. 2A) (14). However, the nucleotide sequences of seven strains (cluster A, strains 11, 17, and 56; cluster B, strains 19 and 52; and cluster C, strains 49 and 57) showed sequence diversity of up to 28% with the Sapporo/82, Parkville/94, and London/92 strains. Therefore, we aligned the deduced amino acid sequences of these strains and found that cluster A and B strains (no. 11, 17, 56, 19, and 52) had a high similarity (97%) with the prototype London/92 strain (Fig. 2B). The genetic sequence of strains from cluster C (strains 49 and 57), however, remained quite distinct from that of strains of either the Sapporo/82, the Parkville/94, or the London/92 cluster (Table 3) and potentially formed a new subgenogroup or genotype within the SLVs (Fig. 2B) (Stockholm genotype). In total, 21 strains (38%) clustered in the London genotype, 28 (51%) clustered in the Sapporo genotype, 3 (5.5%) clustered in the Parkville genotype, and 3 (5.5%) clustered in the Stockholm genotype (Table 1). Of note, all community-acquired cases belonged to the London genotype, and 9 of the 12 outbreak strains for which a partial genomic sequence was known were of the Sapporo genotype. In 1996, strains belonging to three different SLV genotypes (Sapporo, London, and Parkville) were found in hospitalized children in the same geographical region.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of published SLV sequences and sequences from a selection of strains detected in the United Kingdom and Sweden (strain numbers correspond to those in Table 1) and analyzed in this study. Multiple alignments were created based on a 147-nucleotide region of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene (A) and deduced amino acid sequences (B). Distance matrixes were calculated using the Jukes and Cantor correction for evolutionary rate (26). One hundred bootstrapped data sets were analyzed, and evolutionary trees were drawn using the UPGMA clustering method. GenBank accession numbers for the prototype SLVs are as follows: X86560 (Manchester), S77903 (Sapporo), U73124 (Parkville), U43287 (VanderBijlpark), U67858 (London), U67856 (Houston/86), and U67859 (Houston/90).

TABLE 3.

Amino acid sequence identity among Sapporo-like human caliciviruses in a region of the RNA polymerase (Pol) and the complete capsid protein (Cap)

| Strain | % Amino acid sequence identity with:

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sapporo/82

|

Manchester/92

|

Houston/86

|

Parkville/94

|

Houston/90

|

London/92

|

Sweden/97

|

||||||||

| Pol | Cap | Pol | Cap | Pol | Cap | Pol | Cap | Pol | Cap | Pol | Cap | Pol | Cap | |

| Sapporo/82 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 80 | 78 | 82 | 72 | 74 | 42 | 83 | 74 | ||

| Manchester/92 | 98 | 98 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 79 | 72 | 45 | 84 | 74 | ||||

| Houston/86 | 80 | 77 | 82 | 78 | 72 | 44 | 83 | 72 | ||||||

| Parkville/94 | 99 | 97 | 73 | 41 | 79 | 73 | ||||||||

| Houston/90 | 70 | 45 | 78 | 72 | ||||||||||

| London/92 | 68 | 40 | ||||||||||||

| Sweden/97 | ||||||||||||||

Optimization of the generic SLV RT-PCR assay.

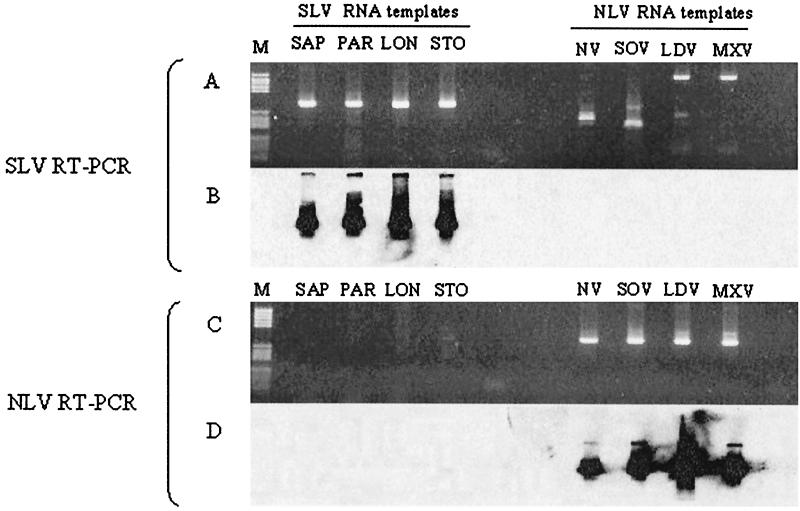

Based on the new Stockholm polymerase nucleotide sequences, a fourth biotin-labeled probe (biot-STO) (Table 2) was developed and included in the panel of probes for confirmation of the generic SLV RT-PCR assay. RNA templates representing the four different SLV genotypes and representative NLV genotypes were tested in parallel with the SLV RT-PCR and the NLV RT-PCR (28), and the specificities of both assays were shown by hybridization (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Results of ethidium bromide staining (A and C) and corresponding Southern hybridization (B and D) of products of generic SLV RT-PCR (320-bp product) (A and B) and NLV RT-PCR (326-bp product) (C and D). The templates were RNA from strains representing the four different SLV genotypes (Sapporo [SAP], Parkville [PAR], London [LON], and Stockholm [STO]) and RNA representing strains from NLV genogroup I (Norwalk [NV] and Southampton [SOV]) and genogroup II (Lordsdale [LDV] and Mexico [MXV]). M, DNA molecular weight marker V.

Determination of the capsid sequences of a potentially new SLV genotype.

The nucleotide sequence of the capsid gene of Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE was determined after nested PCR amplification with primers ST02C and ST03C. After cloning in a TA vector, both strands of the cDNA clone were sequenced. A large open reading frame (ORF) of 1,695 nucleotides was identified. The predicted size of the Stockholm/97 capsid protein is 565 amino acids (60.5K protein), which is in the same range as published SLV capsid protein sequences (14, 17, 23). The highly conserved PPG motif was identified at the expected location (amino acids 136 to 138) in the predicted Stockholm/97 capsid protein. Additionally, a small ORF overlapping the 5′ terminus of the capsid gene (encoding 162 amino acids) was identified.

Location of Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE in a distinct genetic cluster.

Amino acid sequence comparison of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase region and the viral capsid confirmed that Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE belongs to a fourth distinct genetic cluster within the SLVs (Table 3). The Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE strain shares 83% amino acid identity in the polymerase region with Hu/SLV/Sapporo/82/JP, 78% with Hu/SLV/Houston/90/US (Parkville genotype), and 68% with Hu/SLV/London/92/UK. In the capsid region, Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE shares 74% amino acid identity with Hu/SLV/Sapporo/82/JP and 72 and 40% amino acid identities with Hu/SLV/Houston/90/US and Hu/SLV/London/92/UK, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the development of a first-generation RT-PCR assay for the detection of SLVs. Laboratory diagnosis of SLVs has always relied on EM to detect virus particles with the typical calicivirus morphology. Recently, several full-length and partial sequences have been described (2, 17, 22, 23). Based on these findings, Jiang and coworkers showed clearly that SLV capsid sequences are less conserved than RNA polymerase sequences (14). Therefore, we designed primers targeting the RNA polymerase gene and based on published SLV sequences and sequences generated in this study. Using the same assay format as for the detection of NLVs (28), we were able to detect 93% of the strains in a panel with high specificity (100%). In our laboratory, we now use this first-generation RT-PCR assay based on the JV33-SR80 primer pair for diagnostic use and confirm specific RT-PCR products by Southern hybridization.

An interesting finding was that only four of the seven stool samples (57%) from patients more than 5 years old were found positive by RT-PCR, compared with 51 of the 52 stool samples (98%) from young children. All three stool samples from adults that were found negative by RT-PCR were from the same outbreak, and although the numbers were small, this result indicates that additional SLV genotypes circulate in adults. Therefore, in the near future RT-PCR assays based on multiple primers will be necessary for the successful amplification of new, as-yet-undiscovered, SLV genotypes, as has been done for the detection of NLVs (1, 10).

Human caliciviruses can be divided phylogenetically into at least three genogroups, with genogroups I and II representing the NLVs (29) and genogroup III representing the SLVs (18). Recently, based on the genetic distances between genogroup I and II NLVs, the definition of a fourth genogroup within the SLVs, represented by Hu/SLV/London/92/UK, has been suggested (14). Each genogroup can be subdivided into subgenogroups or genotypes (14). In this study, we showed that by phylogenetic analysis of a region of the RNA polymerase gene, most SLV strains could be classified into the three recently described genotypes (14). However, strains in three stool samples from both the United Kingdom (1989) and Sweden (1997) formed a separate genotype within the SLVs. To confirm this potential new genotype, we sequenced the complete viral capsid gene of one of the strains in this cluster, Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE. In the absence of comprehensive antigenic and genomic comparisons, we suggest that, like NLVs (13), SLVs with less than 80% amino acid identity in the complete capsid protein represent antigenically distinct capsid types. On the basis of this assumption, phylogenetic analysis of the complete capsid sequence of Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE in comparison with that of other published complete SLV capsid sequences confirmed the placing in a separate genotype. The strain grouped significantly closer to the Sapporo/82 and Parkville/94 strains than to the London/92 strain. The size of the small ORF overlapping the 5′ terminus (encoding 163 amino acids) is in the same range as that observed for the Sapporo/82 and Houston/90 (Parkville/94-like) strains but not for the London/92 strain (14). Final classification of Hu/SLV/Stockholm/97/SE awaits antigenic characterization by testing with, ideally, enzyme immunoassays specific for the different SLV genotypes (14).

This study enabled us to investigate the genetic variability of SLVs detected by EM in patients with gastroenteritis in Sweden and the United Kingdom over a period of 10 years. Our data indicate that the majority of SLV strains (89%) cluster with either the Sapporo or the London genotype. Moreover, we found Sapporo/82, Parkville/94, and London/92 strains in the Leeds region in the course of 1 year (1996). The cocirculation of different strains in the same time frame is analogous to the epidemiology of NLVs, where a variety of genotypes circulate in outbreaks and in the population in some years. However, for NLVs, in other years (e.g., 1995 and 1996 in The Netherlands) a predominant or common strain causes the majority of the outbreaks (6, 16, 28). In our study, we found no indication for the circulation of a predominant SLV genotype. In contrast to data for NLVs, it is intriguing that all community-acquired strains in the panel belonged to the London genotype and the majority of the outbreak strains were of the Sapporo genotype. This result suggests that there may be differences in the severity of illness caused by different genotypes and possibly in transmissibility. However, the number of strains available for analysis was limited, and the majority of the strains were derived from sporadic cases.

In conclusion, we developed a sensitive, broadly reactive RT-PCR that detects all known SLV genotypes, including the new cluster described in this study. In combination with rapid molecular typing methods, this assay will be used for the screening of large numbers of stool samples from epidemiological studies addressing the incidence of SLVs and their etiologic significance. Future research should focus on the typing of large numbers of strains from different settings to elucidate transmission patterns, as is being done for NLVs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando T, Monroe S S, Gentsch J R, Jin Q, Lewis D C, Glass R I. Detection and differentiation of antigenically distinct small round-structured viruses (Norwalk-like viruses) by reverse transcription-PCR and Southern hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:64–71. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.64-71.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berke T, Golding B, Jiang X, Cubitt W D, Wolfaardt M, Smith A W, Matson D O. Phylogenetic analysis of the caliciviruses. J Med Virol. 1997;52:419–424. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199708)52:4<419::aid-jmv13>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boom R, Sol C J, Salimans M M, Jansen C L, Wertheim-van Dillen P M, van der Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruenn J A. Relationships among the positive strand and double-strand RNA viruses as viewed through their RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;25:217–226. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.2.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cubitt W D. Diagnosis, occurrence and clinical significance of the human 'candidate' caliciviruses. Prog Med Virol. 1989;36:103–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fankhauser R L, Noel J S, Monroe S S, Ando T, Glass R I. Molecular epidemiology of “Norwalk-like viruses” in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1571–1578. doi: 10.1086/314525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green J, Gallimore C I, Norcott J P, Lewis D, Brown D W G. Broadly reactive reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of SRSV-associated gastroenteritis. J Med Virol. 1995;47:392–398. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green J, Vinjé J, Lewis D C, Gallimore C I, Koopmans M P G, Brown D W G. Genomic diversity among human caliciviruses. In: Chasey D, Gaskell R M, Clarke I N, editors. Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Caliciviruses. Addlestone, United Kingdom: European Society for Veterinary Virology; 1996. pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green J, Henshilwood K, Gallimore C I, Brown D W G, Lees D N. A nested reverse transcriptase PCR assay for detection of small round-structured viruses in environmentally contaminated molluscan shellfish. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:858–863. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.858-863.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green K Y. The role of human caliciviruses in epidemic gastroenteritis. Arch Virol. 1997;13:153–165. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6534-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green S M, Lambden P R, Deng Y, Lowes J A, Lineham S, Bushell J, Rogers J, Caul E O, Ashley C R, Clarke I N. Polymerase chain reaction detection of small round-structured viruses from two related hospital outbreaks of gastroenteritis using inosine-containing primers. J Med Virol. 1995;45:197–202. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890450215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy M E, Kramer S F, Treanor J J, Estes M K. Human calicivirus genogroup II capsid sequence diversity revealed by analyses of the prototype Snow Mountain agent. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1469–1479. doi: 10.1007/s007050050173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang X, Cubitt W D, Berke T, Zhong W, Dai X, Nakata S, Pickering L K, Matson D O. Sapporo-like human caliciviruses are genetically and antigenically diverse. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1813–1827. doi: 10.1007/s007050050199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Guyader F, Estes M K, Hardy M E, Neill F H, Green J, Brown D W G, Atmar R L. Evaluation of a degenerate primer for the PCR detection of human caliciviruses. Arch Virol. 1996;141:2225–2235. doi: 10.1007/BF01718228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis D C, Hale A, Jiang X, Eglin R, Brown D W G. Epidemiology of Mexico virus, a small round-structured virus in Yorkshire, United Kingdom, between January 1992 and March 1995. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:951–954. doi: 10.1086/513998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu B L, Clarke I N, Caul E O, Lambden P R. Human enteric caliciviruses have a unique genome structure and are distinct from the Norwalk-like viruses. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1345–1356. doi: 10.1007/BF01322662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matson D O, Zhong W M, Nakata S, Numata K, Jiang X, Pickering L K, Chiba S, Estes M K. Molecular characterization of a human calicivirus with sequence relationships closer to animal caliciviruses. J Med Virol. 1995;45:215–222. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890450218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakata S, Chiba S, Terashima H, Yokoyama T, Nakao T. Humoral immunity in infants with gastroenteritis caused by human calicivirus. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:274–279. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakata S, Estes M K, Chiba S. Detection of human calicivirus antigen and antibody by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2001–2005. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.10.2001-2005.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakata S, Kogawa K, Numata K, Ukae S, Adachi N, Matson D O, Estes M K, Chiba S. The epidemiology of human calicivirus/Sapporo/82/Japan. Arch Virol Suppl. 1996;12:263–270. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noel J S, Liu B L, Humphrey C D, Rodriguez E M, Lambden P R, Clarke I N, Dwyer D M, Ando T, Glass R I, Monroe S S. Parkville virus: a novel genetic variant of human calicivirus in the Sapporo virus clade, associated with an outbreak of gastroenteritis in adults. J Med Virol. 1997;52:173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Numata K, Hardy M E, Nakata S, Chiba S, Estes M K. Molecular characterization of morphologically typical human calicivirus Sapporo. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1537–1552. doi: 10.1007/s007050050178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pringle C R. Virus taxonomy—San Diego 1998. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1449–1459. doi: 10.1007/s007050050389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straus J H, Straus E G. Evolution of RNA viruses. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:657–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van der Peer Y, De Wachter R. TREECON for Windows: a software package for the construction and drawing of evolutionary trees for the Microsoft Windows environment. Comput Applic Biosci. 1994;10:569–570. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinjé J, Koopmans M P G. Molecular detection and epidemiology of small round-structured viruses in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in The Netherlands. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:610–615. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vinjé J, Altena S A, Koopmans M P G. The incidence and genetic variability of small round-structured viruses in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in The Netherlands. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1374–1378. doi: 10.1086/517325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Jiang X, Madore H P, Gray J, Desselberger U, Ando T, Seto Y, Oishi I, Lew J F, Green K Y, Estes M K. Sequence diversity of small, round-structured viruses in the Norwalk virus group. J Virol. 1994;68:5982–5990. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5982-5990.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolfaardt M, Taylor M B, Booysen H F, Engelbrecht L, Grabow W O, Jiang X. Incidence of human calicivirus and rotavirus infection in patients with gastroenteritis in South Africa. J Med Virol. 1997;51:290–296. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199704)51:4<290::aid-jmv6>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamazaki K, Oseto M, Seto Y, Utagawa E, Kimoto T, Minekawa Y, Inouye S, Yamazaki S, Okuno Y, Oishi I. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction detection and sequence analysis of small round-structured viruses in Japan. Arch Virol Suppl. 1996;12:271–276. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]