Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a complication of childhood obesity and an oxidative stress-related multisystem disease. A mitochondria-targeting hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donor AP39 has antioxidant property, while the mechanism underlying the function of AP39 on pediatric NAFLD remains undefined. Here, 3-week-old SD rats were received a high-fat diet (HFD) feeding and injected with AP39 (0.05 or 0.1 mg/kg/day) via the tail vein for up to 7 weeks. AP39 reduced weight gain of HFD rats and improved HFD-caused liver injury, as evidenced by reduced liver index, improved liver pathological damage, decreased NAFLD activity score, as well as low alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) activities. AP39 also reduced serum total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations but increased high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C). Moreover, AP39 prevented reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, reduced MDA content and increased glutathione (GSH) level and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. Furthermore, AP39 increased H2S level, protected mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), reduced mitochondrial swelling, and restored mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) alteration. Notably, AP39 diminished HIF-1α mRNA and protein level, possibly indicating the alleviation in mitochondrial damage. In short, AP39 protects against HFD-induced liver injury in young rats probably through attenuating lipid accumulation, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Keywords: AP39, high-fat diet (HFD), liver injury, mitochondrial function, oxidative stress

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a complication of obesity and a main cause of chronic liver disease in children [1]. Its occurrence is associated with insulin resistance, fat accumulation or steatosis, hypertension, dyslipidemia, inflammation, oxidative stress and subsequent hepatotoxicity [2,3,4]. In recent years, with changes in dietary structure, especially the intake ratio of fats and carbohydrates, the occurrence of NAFLD has increased dramatically, which has been regarded as one of the most prevalent public health problems [5]. There are some therapeutic drugs for NAFLD currently, but considerable side effects and poor long-term safety have been discovered [6]. Therefore, it is very necessary to explore the alternatives available for the effective treatment and prevention of pediatric NAFLD.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a gaseous signaling molecule, has a variety of biological effects in cellular signaling, including regulating inflammatory response, excessive oxidative stress and apoptosis [7,8,9]. It has been reported that H2S at a non-cytotoxic level can serve as an electron donor to mitochondria for maintaining the activities of antioxidant enzymes [10]. High-fat diet (HFD) is a leading cause of NAFLD, and H2S alleviates HFD-induced NAFLD in rats [11, 12]. Besides, H2S donor sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) treatment can also prevent liver injury in rats [13]. These findings indicate that H2S and its relative compounds may have the potential to prevent liver injury.

AP39 (10oxo-10-(4-(3-thioxo-3H-1,2-dithiol-5yl)phenoxy)decyl) is a mitochondria-targeting donor of H2S that can trigger an elevation in H2S production in the mitochondria [14]. AP39 has shown antioxidant and other cytoprotective effects under oxidative conditions [15]. Studies have shown that AP39 reduces the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α [16]. Also, AP39 has a protective role in damage of multiple organs such as the heart, lung and neuron [17,18,19,20]. However, to date, there is no research to clarify whether AP39 can prevent liver injury.

The aim of this study was to investigate the role of AP39 in liver injury in HFD-fed young rats and its underlying mechanisms. Our results demonstrated the protective effect of AP39 on obesity-related liver injury in vivo, providing a theoretical and scientific basis for the use of AP39 in preventing pediatric NAFLD.

Materials and Methods

Animal experiments

All of our animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Anhui Medical University. Healthy male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were purchased from Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Benxi, China). After feeding under controlled laboratory conditions for a week to acclimate to their surroundings, the three-week-old rats were randomly divided into the control group, HFD group, HFD+AP39 low-dose (HFD+L-AP39) and HFD+AP39 high-dose (HFD+H-AP39) groups (n=6 per group).

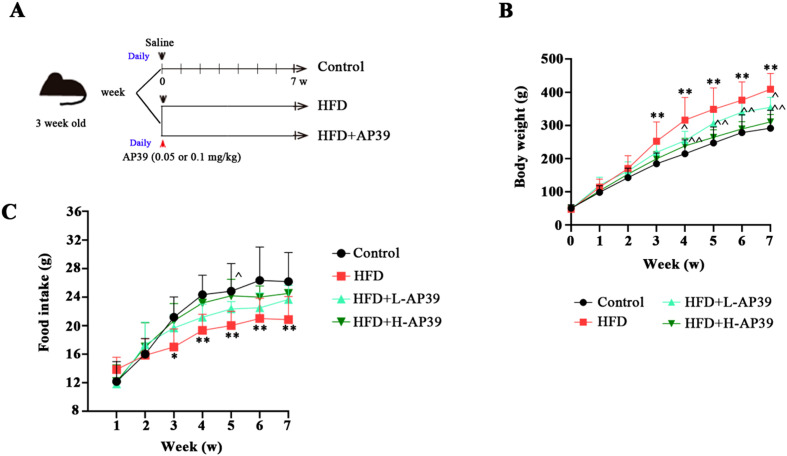

As shown in Fig. 1A, the animals (3 week old) in the control group were fed with a normal fodder (purchased from Beijing Huanyu Zhongke Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 7 weeks, while the other groups were fed a HFD (69% of basic feed, 10% of lard oil, 2% of cholesterol, 5% of sugar, 0.5% of cholate, 10% of yolk powder, 3% of yeast powder and 0.5% of decavitamin; BetterBiotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) [21]. To investigate the impact of AP39 on HFD rats, the rats in HFD+L-AP39 and HFD+H-AP39 groups were injected daily by tail vein with AP39 (APExBIO, Houston, TX, USA) at the dose of 0.05 mg/kg or 0.1 mg/kg, respectively [19]. The rats in control and HFD groups were received the same volume of saline. The food intake and body weight of all the rats was recorded per week for up to 7 weeks. At the end of the experiment, all of the tested rats were sacrificed by intraperitoneal injection of overdose (200 mg/kg) of pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal; Shandong XiYa Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Linyi, China). Thereafter, the blood was harvested from the inferior vena cava of rats, and the livers were removed, photographed and weighed. Liver weight index was calculated based on the formula liver wet weight / body weight × 100%. Tissue samples were either fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution or frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until use.

Fig. 1.

Effect of AP39 on obesity. High-fat-diet (HFD)-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) rats were intravenously injected with 0.05 or 0.1 mg/kg AP39 once a day for 7 weeks. (A) Schematic abstract of the experimental process. (B, C) Body weight and food intake of young rats was recorded once a week for 7 weeks. **P<0.01 vs. Control; ^P<0.05, ^^P<0.01 vs. HFD.

Histological analysis of liver

For assessment of lipid staining, the fixed tissues were dehydrated in 20% and 30% sucrose solution successively, and embedded with OCT embedding agent, and then sectioned into 10 µm. The slices were stained with oil red O solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and counterstained with hematoxylin (Solarbio, Beijing, China). For hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, the fixed and paraffin-embedded liver samples were cut into 5 µm slices and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Sangon, Shanghai, China). All pathological images were observed under an optical microscope at 200× magnification. After that, based on H&E staining analysis, the NAFLD activity score, a histological scoring system for NAFLD, was calculated as the unweighted sum of the scores for steatosis (0–3), lobular inflammation (0–3), and ballooning (0–2) [22].

Biochemical parameters

Serum alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) activities were determined using the commercial ALT and AST assay kits. Total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) contents in serum were measured by the TC, TG, LDL-C and HDL-C assay kits, respectively. The levels of oxidative stress parameters malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione (GSH) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in liver tissues were examined by the corresponding MDA, GSH and SOD assay kits. The above kits were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). In addition, hepatic H2S level was measured using a H2S assay kit (Solarbio). All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

DHE staining

The embedded liver tissues were sectioned into 10 µm, and incubated with the fluorescent dye dihydroethidium (DHE; Beyotime, Shanghai, China; 1:100 dilution) at room temperature for 30 min. The sections were examined using a 400× fluorescence microscope.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

For quantification of HIF-1α, total RNA was extracted using a high-purity total RNA rapid extraction kit (BioTeke, Beijing, China) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the M-MLV reverse transcriptase. RT-qPCR was then performed on the ExicyclerTM 96 fluorescence quantifier using SYBR Green Master Mix. The relative mRNA expression of HIF-1α was calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method and normalized to β-actin. For mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content determination, DNA extraction was performed using a tissue genomic DNA extraction kit (BioTeke). The copy number of mtDNA was evaluated by RT-qPCR, as described in a previous study [23]. The primers used, synthesized by GenScript (Nanjing, China), were listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Sequence of primers used in RT-qPCR.

| Gene | Primers | Sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|

| mtDNA | Forward | TGAGCCATCCCTTCACTAGG |

| Reverse | TGAGCCGCAAATTTCAGAG | |

| nuclear DNA (β-actin) | Forward | CTGCTCTTTCCCAGATGAGG |

| Reverse | CCACAGCACTGTAGGGGTTT | |

| HIF-1α | Forward | CTACTATGTCGCTTTCTTGG |

| Reverse | GTTTCTGCTGCCTTGTATGG | |

| β-actin | Forward | GGAGATTACTGCCCTGGCTCCTAGC |

| Reverse | GGCCGGACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTT | |

Immunoblot analysis

Western blot was performed according to Jia et al.’s description [24]. The target protein HIF-1α was separated, quantified and blotted with anti-HIF-1α (Affinit, China; 1:500 dilution). β-actin (Proteintech, Wuhan, China; 1:2,000 dilution) was used for normalization.

Mitochondrial swelling assessment

Hepatic mitochondria were analyzed using the tissue mitochondrial isolation kit (Beyotime). On the basis of the previous description [25], the degree of liver mitochondrial swelling was represented by the relative absorbance value (ΔA) of mitochondrial suspension at 520 nm for 20 min. The Larger ΔA indicates the more complete mitochondrial structure. A large ΔA represents a stronger buffering ability of calcium ions and better structural integrity in mitochondria of liver.

Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was detected using the MMP assay kit (Beyotime). The prepared mitochondria were incubated with the fluorescent cationic dye JC-1, followed by analyzing with a fluorescence microplate reader. The red/green fluorescence ratio indicated the activity of hepatic mitochondria.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were reported as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric analysis of variance followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used for comparative analysis of multiple groups of independent samples. A P-value under 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effect of AP39 on body weight

As illustrated in Fig. 1A, the tested young rats with a similar average weight were received a HFD feeding and treated with AP39 for 7 weeks. We found that HFD resulted in a significant increase in the body weight of rats compared with normal diet rats. Administration of AP39 reduced HFD-induced weight gain in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.05, Fig. 1B). In addition, from the 3rd week to the 7th week of feeding, HFD obviously reduced the food intake of rats, while the food intake of rats with AP39 treatment showed an increasing trend, but it was not significant except for the 5th week (Fig. 1C), which was consistent with Jia et al. and Ren et al.’ studies [12, 24]. These findings indicate the potential of AP39 in childhood obesity.

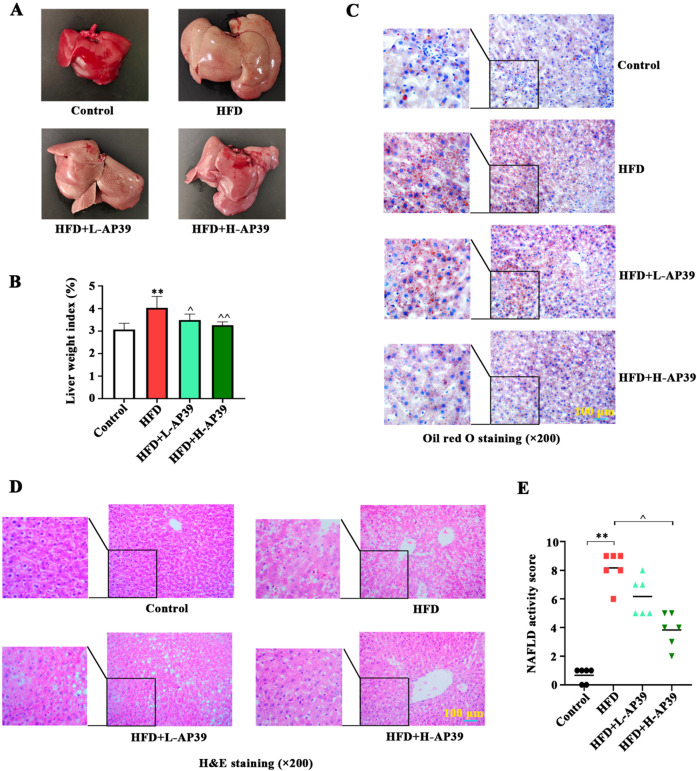

AP39 counteracts HFD-induced liver injury

Childhood obesity is strongly associated with the occurrence of NAFLD [26]. Here, we focused on the function of AP39 in HFD-caused liver injury in young rats. At the end of the experiment, the livers of the experimental rats were photographed, as shown in Fig. 2A. We observed a significant increase in liver size after HFD, with the color changing from dark red to brown yellow, which were improved by AP39 treatment. Moreover, the liver weight index of HFD rats was higher, while AP39 injection partially abolished it (P<0.05, Fig. 2B). Histological analysis of the liver using oil red O (Fig. 2C) and H&E staining (Fig. 2D) revealed the changes in hepatic steatosis in rats. We observed that there was increased lipid infiltration area and fatty vacuole area in the liver of HFD rats. However, these liver pathological damages caused by HFD were abrogated and returned to almost normal level after AP39 treatment. NAFLD activity score further confirmed that AP39 attenuated HFD-induced liver injury (P<0.05, Fig. 2E). These findings suggest a beneficial effect of AP39 on HFD-caused liver injury in vivo.

Fig. 2.

Effect of AP39 on high-fat-diet (HFD)-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). (A) At the end of the experiment, the liver tissues were harvested. Gross morphology of liver tissue was observed. (B) Liver weight index was calculated according to the formula liver wet weight / body weight × 100%. (C, D) The histological alternations of liver tissues were visualized with Oil red O staining (×200) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (×200), and the representative photomicrographs were shown. (E) NAFLD activity score, a histological scoring system for NAFLD, was counted. **P<0.01 vs. Control; ^P<0.05, ^^P<0.01 vs. HFD.

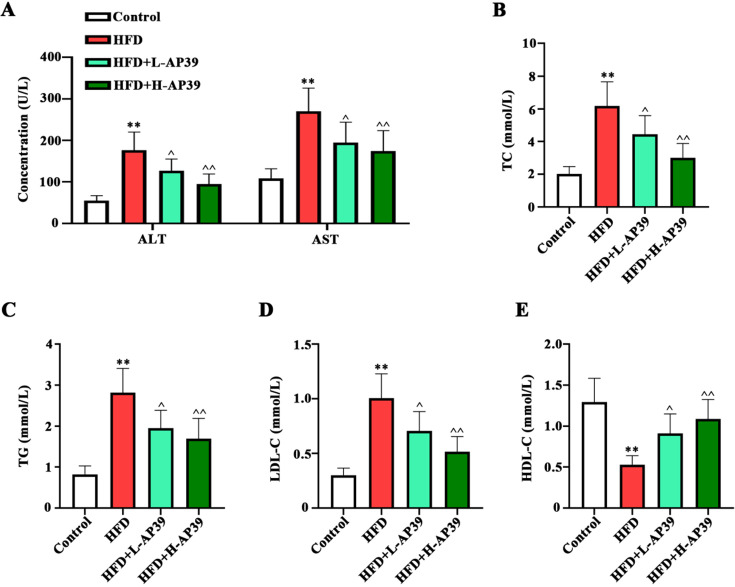

AP39 prevents serum lipid accumulation

We further verified the lipid-lowing role of AP39, as shown in Fig. 3. Serum ALT and AST activities were significantly increased in HFD-induced rats, while AP39 treatment eliminated these changes (P<0.05, Fig. 3A). Meanwhile, the changes of serum lipid profiles TC, TG, LDL-C and HDL-C were examined. AP39 treatment could induce a reduction in TC, TG, LDL-C levels and an increase in HDL-C in HFD rats (P<0.05, Figs. 3B–E). Overall, these data suggest that AP39 effectively alleviates lipid accumulation in HFD-fed young rats.

Fig. 3.

Effect of AP39 on lipid profiles in serum of rats. (A–E) Relative levels of serum ALT, AST, TC, TG, LDL-C and HDL-C were determined using the corresponding kits. ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; TC, total cholesterol; TG, total triglycerides; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. **P<0.01 vs. Control; ^P<0.05, ^^P<0.01 vs. HFD.

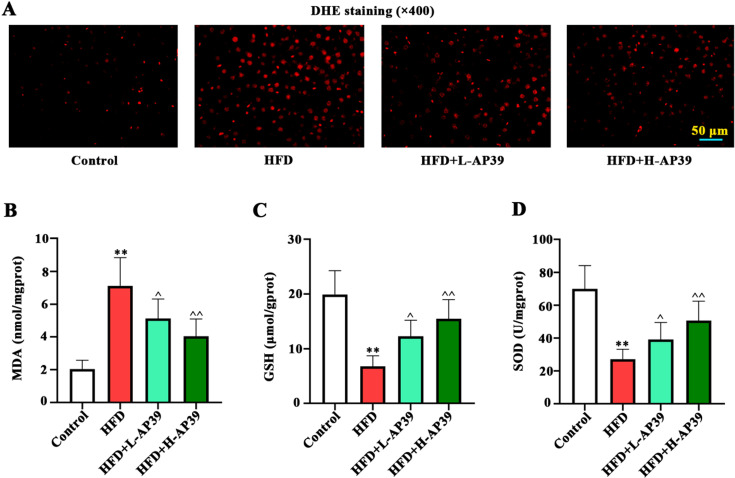

Antioxidant effect of AP39 in NAFLD

To illuminate the effect of AP39 on oxidative stress, hepatic ROS and oxidative stress-related MDA, GSH, SOD were measured. As visualized by DHE staining, HFD resulted in increased ROS production, which was eliminated by AP39 administration (Fig. 4A). In addition, AP39 remarkably decreased MDA content, and increased GSH level and SOD activity in HFD-fed young rats (P<0.05, Figs. 4B–D), indicating the antioxidant effect of AP39.

Fig. 4.

Effect of AP39 on high-fat diet (HFD)-induced oxidative stress. (A) DHE staining (×400) was used for ROS detection in liver. (B–D) Levels of markers of oxidative stress, MDA, GSH and SOD, were measured with commercial kits. ROS, reactive oxygen species; MDA, malondialdehyde; GSH, glutathione; SOD, superoxide dismutase. **P<0.01 vs. Control; ^P<0.05, ^^P<0.01 vs. HFD.

AP39 diminishes HFD-caused mitochondrial dysfunction

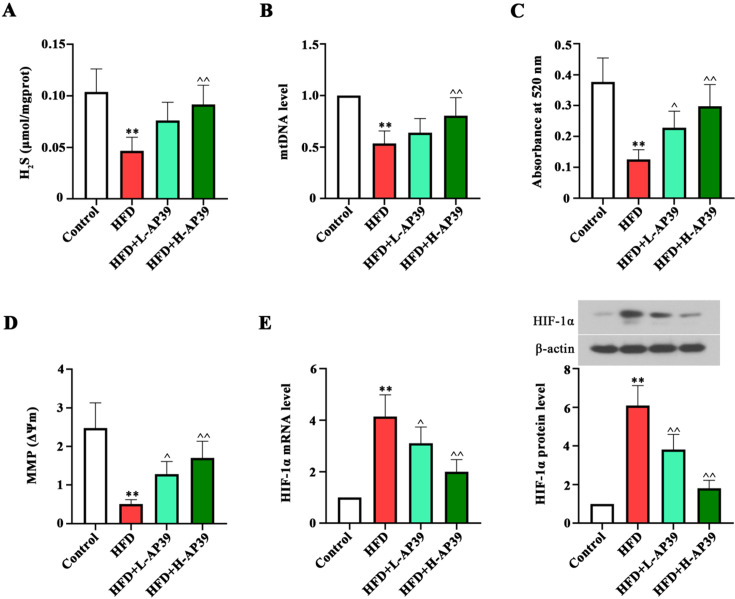

As expected, the H2S level in the liver of HFD-fed young rats was lower than that of control rats, while AP39 enhanced it (P<0.01, Fig. 5A). We then explored the role of AP39 in HFD-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. The mtDNA integrity, mitochondrial swelling and MMP alteration were measured to evaluate mitochondrial function. The copy number of mtDNA was increased after AP39 treatment (P<0.01, Fig. 5B). In addition, AP39 increased the absorbance at 520 nm, suggesting the amelioration of HFD-induced mitochondrial swelling (P<0.05, Fig. 5C). The loss of MMP was decreased in AP39-treated HFD rats as compared to HFD-fed rats (P<0.05, Fig. 5D). Noteworthy, AP39 significantly downregulated hepatic HIF-1α expression at mRNA and protein levels (P<0.05, Fig. 5E). These results indicated that the adverse effects of HFD on hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction are partially reversed with AP39 treatment.

Fig. 5.

Effect of AP39 on H2S level and mitochondrial function. (A) Hepatic H2S level was detected using the H2S determination kit. (B) mtDNA copy number in the liver was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). (C) The degree of mitochondrial swelling was analyzed at 520 nm wavelength on a spectrophotometer. (D) Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) changes were detected using JC-1 probe. (E) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) expression at mRNA and protein levels was determined by RT-qPCR and western blot, respectively. **P<0.01 vs. Control; ^P<0.05, ^^P<0.01 vs. high-fat diet (HFD).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate the effectiveness of AP39 in preventing HFD-induced liver injury in vivo. Treatment with AP39 alleviates obesity, hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in HFD-fed young rats. These findings indicate that AP39 may be a promising therapeutic treatment for the prevention of pediatric NAFLD. Our finding is the first report to reveal the impact of AP39 on obesity-related liver injury.

Herein, three-week-old rats were fed with HFD for 7 weeks to mimic the symptoms of pediatric NAFLD. HFD-feeding significantly increased body weight and liver weight index, reduced food intake, elevated NAFLD activity score, ALT and AST activities and hepatic steatosis in young rats, which are known to aggravate liver injury and may accelerate the progression of NAFLD [27, 28]. A growing body of evidence supports that H2S can protect against tissue damage, such as heart, liver, lung and retina [29]. AP39, a mitochondrial-targeted H2S donor exhibits beneficial effects on tissue injury including heart, lung and neuron [17,18,19,20]. In our study, AP39 decreased body weight gain, liver weight index and liver color almost reaching normal level, as well as decreased ALT and AST activities in HFD-fed young rats. These results clearly validate that AP39 could improve HFD-induced liver injury.

Liver is a key lipid metabolic organ and abnormal lipid metabolism is tightly related to the damage of liver function. A HFD is responsible for the imbalance between lipid acquisition and disposal in the liver, which subsequently accelerates the progression of NAFLD [30]. Our results demonstrated that AP39 decreased lipid accumulation, as manifested by reduced TC, TG, LDL-C and elevated HDL-C in serum of HFD-fed rats. Previous studies have confirmed that fat accumulation in liver can block lipid metabolic homeostasis and cause severe hepatotoxicity [31]. It seems that our findings indicate the protection of AP39 on HFD-induced liver injury by maintaining the balance of lipid metabolism, although the potential mechanism by which AP39 regulates NAFLD-related lipid metabolism is still elusive until now.

A HFD results in elevated ROS production and excessive oxidative stress in liver [32], which is in line with our finding showing that ROS level was elevated in the liver of HFD-fed rats. Interestingly, in our study, AP39 suppressed HFD-induced ROS generation. Moreover, lower oxidant MDA and more antioxidants GSH and SOD are required to attenuate and repair obesity-induced liver injury [33]. Several lines of evidence have shown that AP39 has an antioxidant effect [16,17,18, 34]. Similarly, here, we found that AP39 inhibited MDA content and increased GSH level and SOD activity in HFD-fed young rats, suggesting that AP39 may ameliorate HFD-induced liver injury by inhibiting excessive oxidative stress.

Mitochondria modulate lipid metabolism and oxidative stress, and their dysfunction can lead to the disruption of lipid homeostasis, resulting in the occurrence of liver diseases including NAFLD [32, 35]. mtDNA is a major target of ROS, and HFD-feeding may damage mtDNA and aggravate liver injury [36,37,38]. Here, we observed a significant reduction in mtDNA quantity in the liver of HFD-fed rats, which was reversed by AP39. Besides, HFD-feeding increased the degree of mitochondrial swelling and the loss of MMP, which are similar to previous studies [25, 39]. Notably, AP39 restored hepatic mitochondrial function. Our findings were consistent with the research that AP39 protects against the loss of mtDNA and preserves mitochondrial activity [14, 18]. The above results manifest that AP39 protects mitochondrial function in HFD-induced liver injury. More importantly, mtDNA copy number is correlated with the expression of HIF-1α in liver [40]. HIF-1α, a key transcription factor, has been described as an important regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, which can affect the development and progression of NAFLD [41, 42]. Covarrubias et al.’s study revealed that AP39 treatment reduces HIF-1α level and improves mitochondrial function [16]. In the present study, we found that HFD-feeding upregulated HIF-1α expression in the liver, while AP39 abolished it, which further confirmed the beneficial effect of AP39 on HFD-induced liver injury.

The pathogenesis of NAFLD is complicated and involves glucose and lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and inflammation. HFD can increase hepatic lipid influx and de novo lipogenesis and impair insulin signaling, thus promoting triglyceride accumulation in liver and ultimately NAFLD [43]. Lensu et al.’s study found that HFD-feeding reduces food intake and enhances body weight gain and body fat content of rats [44], which is consistent with our findings. Lipid accumulation in the liver in NAFLD may be due to an imbalance in lipid metabolism as characterized by decreased oxidative capacity or increased lipogenic activity. In addition, metabolic imbalance leads to mitochondrial functional overload, which ultimately causes liver injury. Moreover, in fat-engorged hepatocytes, several vicious cycles involving ROS, lipid peroxidation products alter respiratory chain polypeptides and mtDNA, thus partially blocking the flow of electrons in the respiratory chain. Overreduction of upstream respiratory chain complexes increases mitochondrial ROS. Oxidative stress increases the release of lipid peroxidation products and inflammatory cytokines, which together trigger the liver lesions of NAFLD [45]. Therefore, in our study, HFD-feeding increased weight gain, reduced food intake of young rats, possibly due to the enhancement of oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction in NAFLD. Of note, AP39 partially ameliorates the liver damage caused by HFD, indicating the protection of AP39 on HFD-induced liver injury in young rats.

In conclusion, AP39 exerts a beneficial effect on HFD-induced liver injury in young rats possibly by modulating lipid metabolism, oxidative stress and mitochondrial function. Current and future investigation on the effects of AP39 may provide a novel insight into the treatment of pediatric NAFLD.

Author’s Contributions

L.Y. designed the research study. Y.Y. and S.Y. performed the experiments. Y.Y. and D.L. analyzed the data. Y.Y. drafted the article. L.Y. revised the article. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

The authors all claim no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Clinical Research Cultivation Program of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical university (No.2020LCYB07) and the Quality Engineering Project of Universities in Anhui Province (No. 2019jyxm1012).

References

- 1.Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999; 116: 1413–1419. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70506-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiniakos DG, Vos MB, Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: pathology and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010; 5: 145–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cobbina E, Akhlaghi F. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) - pathogenesis, classification, and effect on drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters. Drug Metab Rev. 2017; 49: 197–211. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2017.1293683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu L, Nagata N, Ota T. Impact of Glucoraphanin-Mediated Activation of Nrf2 on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with a Focus on Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20: 5920. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S, Kaufman T. Childhood obesity. Panminerva Med. 2018; 60: 200–212. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.18.03557-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi Y, Sugimoto K, Inui H, Fukusato T. Current pharmacological therapies for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21: 3777–3785. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i13.3777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olas B. Hydrogen sulfide in signaling pathways. Clin Chim Acta. 2015; 439: 212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge X, Sun J, Fei A, Gao C, Pan S, Wu Z. Hydrogen sulfide treatment alleviated ventilator-induced lung injury through regulation of autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Int J Biol Sci. 2019; 15: 2872–2884. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.38315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol Rev. 2012; 92: 791–896. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wen YD, Wang H, Kho SH, Rinkiko S, Sheng X, Shen HM, et al. Hydrogen sulfide protects HUVECs against hydrogen peroxide induced mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e53147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mani S, Cao W, Wu L, Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide and the liver. Nitric Oxide. 2014; 41: 62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren R, Yang Z, Zhao A, Huang Y, Lin S, Gong J, et al. Sulfated polysaccharide from Enteromorpha prolifera increases hydrogen sulfide production and attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat diet rats. Food Funct. 2018; 9: 4376–4383. doi: 10.1039/C8FO00518D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan G, Pan S, Li J, Dong X, Kang K, Zhao M, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity, liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension in rats. PLoS One. 2011; 6: e25943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szczesny B, Módis K, Yanagi K, Coletta C, Le Trionnaire S, Perry A, et al. AP39, a novel mitochondria-targeted hydrogen sulfide donor, stimulates cellular bioenergetics, exerts cytoprotective effects and protects against the loss of mitochondrial DNA integrity in oxidatively stressed endothelial cells in vitro. Nitric Oxide. 2014; 41: 120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad A, Olah G, Szczesny B, Wood ME, Whiteman M, Szabo C. AP39, A Mitochondrially Targeted Hydrogen Sulfide Donor, Exerts Protective Effects in Renal Epithelial Cells Subjected to Oxidative Stress in Vitro and in Acute Renal Injury in Vivo. Shock. 2016; 45: 88–97. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covarrubias AE, Lecarpentier E, Lo A, Salahuddin S, Gray KJ, Karumanchi SA, et al. AP39, a Modulator of Mitochondrial Bioenergetics, Reduces Antiangiogenic Response and Oxidative Stress in Hypoxia-Exposed Trophoblasts: Relevance for Preeclampsia Pathogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2019; 189: 104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karwi QG, Bornbaum J, Boengler K, Torregrossa R, Whiteman M, Wood ME, et al. AP39, a mitochondria-targeting hydrogen sulfide (H2 S) donor, protects against myocardial reperfusion injury independently of salvage kinase signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2017; 174: 287–301. doi: 10.1111/bph.13688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao FL, Fang F, Qiao PF, Yan N, Gao D, Yan Y. AP39, a Mitochondria-Targeted Hydrogen Sulfide Donor, Supports Cellular Bioenergetics and Protects against Alzheimer’s Disease by Preserving Mitochondrial Function in APP/PS1 Mice and Neurons. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016; 2016: 8360738. doi: 10.1155/2016/8360738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wepler M, Merz T, Wachter U, Vogt J, Calzia E, Scheuerle A, et al. The Mitochondria-Targeted H2S-Donor AP39 in a Murine Model of Combined Hemorrhagic Shock and Blunt Chest Trauma. Shock. 2019; 52: 230–239. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmad A, Szabo C. Both the H2S biosynthesis inhibitor aminooxyacetic acid and the mitochondrially targeted H2S donor AP39 exert protective effects in a mouse model of burn injury. Pharmacol Res. 2016; 113:(Pt A): 348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi T, Yang X, Zhou H, Xi J, Sun J, Ke Y, et al. Activated carbon N-acetylcysteine microcapsule protects against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in young rats via activating telomerase and inhibiting apoptosis. PLoS One. 2018; 13: e0189856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin Z, Murphy MC, Li J, Glaser KJ, Mauer AS, Mounajjed T, et al. Prediction of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score (NAS) with multiparametric hepatic magnetic resonance imaging and elastography. Eur Radiol. 2019; 29: 5823–5831. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06076-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W, Wang M, Ruan Y, Tan J, Wang H, Yang T, et al. Ginkgolic Acids Impair Mitochondrial Function by Decreasing Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Promoting FUNDC1-Dependent Mitophagy. J Agric Food Chem. 2019; 67: 10097–10106. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b04178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia N, Lin X, Ma S, Ge S, Mu S, Yang C, et al. Amelioration of hepatic steatosis is associated with modulation of gut microbiota and suppression of hepatic miR-34a in Gynostemma pentaphylla (Thunb.) Makino treated mice. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2018; 15: 86. doi: 10.1186/s12986-018-0323-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren T, Zhu L, Shen Y, Mou Q, Lin T, Feng H. Protection of hepatocyte mitochondrial function by blueberry juice and probiotics via SIRT1 regulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Food Funct. 2019; 10: 1540–1551. doi: 10.1039/C8FO02298D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann JP, Valenti L, Scorletti E, Byrne CD, Nobili V. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children. Semin Liver Dis. 2018; 38: 1–13. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1627456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia HM, Wang J, Xie XJ, Xu LJ, Tang SQ. Green tea polyphenols attenuate hepatic steatosis, and reduce insulin resistance and inflammation in high-fat diet-induced rats. Int J Mol Med. 2019; 44: 1523–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitade H, Chen G, Ni Y, Ota T. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Insulin Resistance: New Insights and Potential New Treatments. Nutrients. 2017; 9: 387. doi: 10.3390/nu9040387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu D, Wang J, Li H, Xue M, Ji A, Li Y. Role of Hydrogen Sulfide in Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015; 2015: 186908. doi: 10.1155/2015/186908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ipsen DH, Lykkesfeldt J, Tveden-Nyborg P. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic lipid accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018; 75: 3313–3327. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2860-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller CN, Yang JY, Avra T, Ambati S, Della-Fera MA, Rayalam S, et al. A dietary phytochemical blend prevents liver damage associated with adipose tissue mobilization in ovariectomized rats. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015; 23: 112–119. doi: 10.1002/oby.20907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sumida Y, Niki E, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T. Involvement of free radicals and oxidative stress in NAFLD/NASH. Free Radic Res. 2013; 47: 869–880. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2013.837577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Li HX, Pan WS, Ullah Khan F, Qian C, Qi-Li FR, et al. Administration of methyl palmitate prevents non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) by induction of PPAR-α. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019; 111: 99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerő D, Torregrossa R, Perry A, Waters A, Le-Trionnaire S, Whatmore JL, et al. The novel mitochondria-targeted hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donors AP123 and AP39 protect against hyperglycemic injury in microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. Pharmacol Res. 2016; 113:(Pt A): 186–198. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paradies G, Paradies V, Ruggiero FM, Petrosillo G. Oxidative stress, cardiolipin and mitochondrial dysfunction in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20: 14205–14218. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jha SK, Jha NK, Kumar D, Ambasta RK, Kumar P. Linking mitochondrial dysfunction, metabolic syndrome and stress signaling in Neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017; 1863: 1132–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malik AN, Czajka A. Is mitochondrial DNA content a potential biomarker of mitochondrial dysfunction? Mitochondrion. 2013; 13: 481–492. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malik AN, Simões ICM, Rosa HS, Khan S, Karkucinska-Wieckowska A, Wieckowski MR. A Diet Induced Maladaptive Increase in Hepatic Mitochondrial DNA Precedes OXPHOS Defects and May Contribute to Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cells. 2019; 8: 1222. doi: 10.3390/cells8101222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simões ICM, Fontes A, Pinton P, Zischka H, Wieckowski MR. Mitochondria in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2018; 95: 93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chowdhury A, Aich A, Jain G, Wozny K, Lüchtenborg C, Hartmann M, et al. Defective Mitochondrial Cardiolipin Remodeling Dampens HIF-1α Expression in Hypoxia. Cell Rep. 2018; 25: 561–570.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonzalez FJ, Xie C, Jiang C. The role of hypoxia-inducible factors in metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018; 15: 21–32. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0096-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carabelli J, Burgueño AL, Rosselli MS, Gianotti TF, Lago NR, Pirola CJ, et al. High fat diet-induced liver steatosis promotes an increase in liver mitochondrial biogenesis in response to hypoxia. J Cell Mol Med. 2011; 15: 1329–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01128.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Antonucci L, Porcu C, Iannucci G, Balsano C, Barbaro B. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nutritional Implications: Special Focus on Copper. Nutrients. 2017; 9: 1137. doi: 10.3390/nu9101137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lensu S, Pariyani R, Mäkinen E, Yang B, Saleem W, Munukka E, et al. Prebiotic Xylo-Oligosaccharides Ameliorate High-Fat-Diet-Induced Hepatic Steatosis in Rats. Nutrients. 2020; 12: 3225. doi: 10.3390/nu12113225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pessayre D. Role of mitochondria in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 22:(Suppl 1): S20–S27. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04640.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the manuscript.