Abstract

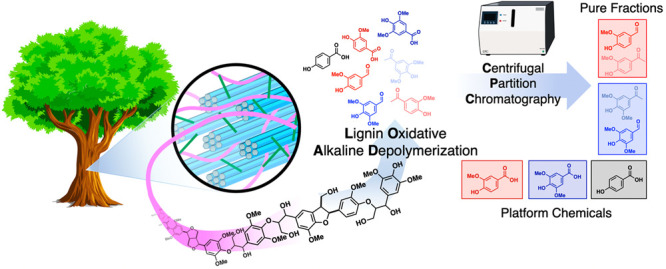

Lignin has long been recognized as a potential feedstock for aromatic molecules; however, most lignin depolymerization methods create a complex mixture of products. The present study describes an alkaline aerobic oxidation method that converts lignin extracted from poplar into a collection of oxygenated aromatics, including valuable commercial compounds such as vanillin and p-hydroxybenzoic acid. Centrifugal partition chromatography (CPC) is shown to be an effective method to isolate the individual compounds from the complex product mixture. The liquid–liquid extraction method proceeds in two stages. The crude depolymerization mixture is first subjected to ascending-mode extraction with the Arizona solvent system L (pentane/ethyl acetate/methanol/water 2:3:2:3), enabling isolation of vanillin, syringic acid, and oligomers. The remaining components, syringaldehyde, vanillic acid, and p-hydroxybenzoic acid (pHBA), were resolved by using ascending-mode extraction with solvent mixture comprising dichloromethane/methanol/water (10:6:4) separation. These results showcase CPC as an effective technology that could provide scalable access to valuable chemicals from lignin and other biomass-derived feedstocks.

Short abstract

Centrifugal partition chromatography enables efficient isolation of individual aromatic chemicals generated as a mixture from oxidative alkaline depolymerization of hardwood lignin.

Introduction

Lignocellulosic biomass represents a valuable resource that is capable of supplementing or substituting petroleum-based chemical feedstocks and raw materials.1,2 Many biomass valorization efforts prioritize the recovery and conversion of (hemi)cellulose sugar streams,3 while extracting little value from lignin.4,5 The economic viability of biorefineries, however, will greatly benefit from utilization of all three major components: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (Figure 1a). Lignin is a biopolymer derived from radical polymerization of monolignols and offers significant promise as a source of aromatic chemical feedstocks and products.6−12 Conventional methods for biomass processing lead to modification or degradation of the lignin, making it notoriously recalcitrant.3,13 Extensive efforts in recent years have led to new biomass fractionation methods that improve separation and recovery of the different components, and processes that retain native sugar and lignin structures typically lead to improved conversion yields.10,14−18

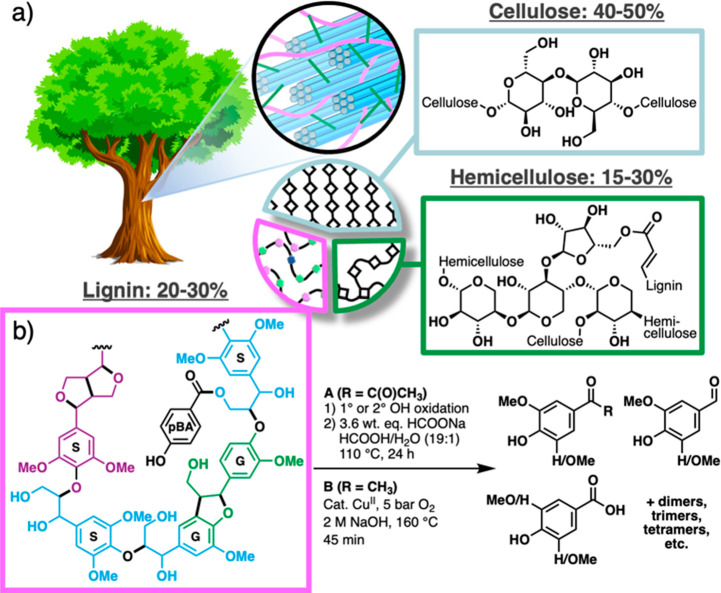

Figure 1.

Lignin is a substantial component of lignocellulosic biomass and potentially an abundant renewable resource of aromatics pending the development of economical valorization methods. (a) Typical ranges of lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose composition in trees. Representative chemical structures of each biopolymer are shown. (b) Oxidative depolymerizations of lignin yield oligomers and bifunctional monoaromatics, some of which are commercially relevant such as vanillin and pHBA.

The present study builds on the “Cu-AHP” method for fractionation of poplar-derived biomass.19,20 This method employs a homogeneous Cu catalyst in combination with alkaline hydrogen peroxide to separate lignin from sugars. The cellulose derived in this manner affords high yields of glucose following enzymatic hydrolysis,21 and the various studies indicate that the lignin stream is also of high quality.22−24

Depolymerization of lignin into aromatic monomers is a prominent target among lignin valorization efforts, and numerous chemical and catalytic methods have been developed to achieve this goal. The product compositions and yields depend on the depolymerization method employed, in addition to the biomass plant source and fractionation method.6−12 Oxidative methods are particularly appealing, as they yield valuable bifunctional aromatic products25 (Figure 1b) and offer advantages for biological funneling.26 Lignin oxidative alkaline depolymerization (LOAD) methods have been the focus of extensive study and application,27 including commercial use for the production of vanillin.28,29 Whereas softwoods generate vanillin as the major product under these conditions, hardwood lignins (e.g., from poplar) generate multiple aromatic chemicals in significant quantities, including para-hydroxybenzoic acid (pHBA), vanillin, vanillic acid, syringaldehyde, and syringic acid.30

Isolation of the individual aromatic products from complex mixtures following lignin depolymerizations is a major, largely unaddressed challenge. The separation and purification of multiple monomers from complex product streams is challenging,31 and most previous efforts have prioritized isolation of a single valuable product, such as vanillin.32−34 Methods targeting isolation of multiple products will inevitably require numerous unit operations.35 An ideal isolation method would feature few unit operations, require no chemical additives, and be compatible with large-scale application. Liquid–liquid chromatographic methods have the potential to meet these criteria36 and offer advantages over the use of membranes or solid stationary phases, which are costly and susceptible to fouling.37−39

Liquid–liquid chromatography of lignin depolymerization mixtures has been used as an analytical tool to gain insight into depolymerization methods (e.g., following pyrolysis),40,41 demonstrated on model sample mixtures,42 and analyzed computationally.43 Here, we present the first preparative scale application of liquid–liquid chromatography to separate aromatic monomers following lignin depolymerization. A two-stage centrifugal partition chromatography (CPC) strategy is employed to isolate monomers from alkaline oxidative depolymerization of Cu-AHP lignin. The methodology and results outlined herein establish an important foundation for future efforts to isolate valuable aromatic products derived from lignin.

Results and Discussion

Oxidative Alkaline Depolymerization of Cu-AHP Lignin

Lignin used to conduct depolymerization experiments was obtained from debarked NE-19 poplar wood chips subjected to previously reported Cu-AHP conditions.19 Solid Cu-AHP lignin samples were dissolved in aqueous NaOH solutions and subjected to LOAD conditions to promote depolymerization into aromatic products.30 Optimization efforts were conducted as parallel batch experiments, using a 1 L Parr pressure reactor equipped with eight PTFE reaction vessels containing 10 mL of solution with 50 mg lignin, variable quantities of a CuSO4 as a catalyst, and a stir bar. The Parr vessel was pressurized with 25 bar of air and heated to 160 °C over 45 min. Upon reaching the set temperature, the heating mantle was removed and the vessel was cooled with an ice bath to quench the reaction. Each reaction mixture was then acidified with HCl (conc.), the aqueous mixture was extracted with EtOAc, and the mixture of organic products was analyzed by HPLC. Products of the reaction include pHBA, vanillin, vanillic acid, acetovanillone, syringaldehyde, syringic acid, and acetosyringone (Figure 2a).

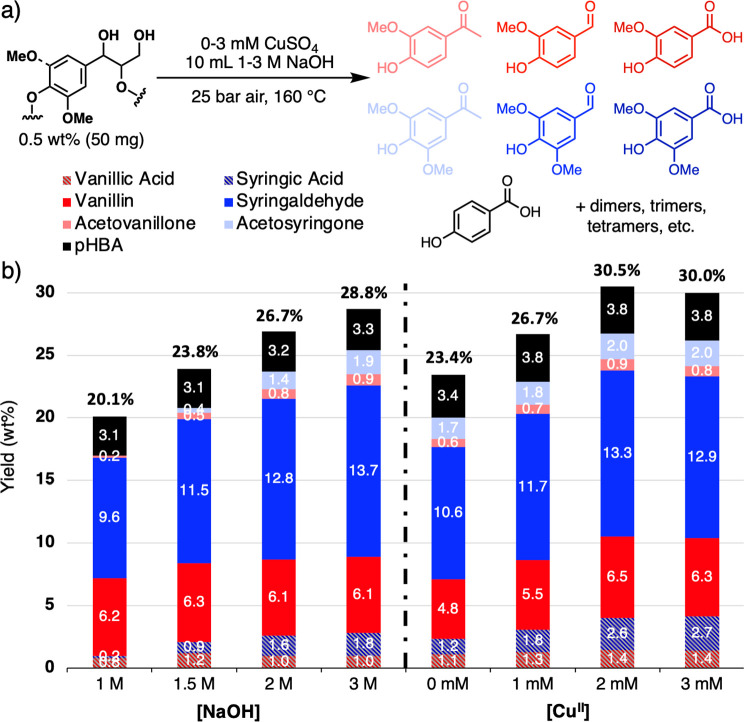

Figure 2.

Aromatic monomers obtained from oxidative alkaline depolymerization of Cu-AHP lignin (a) and the effects of catalyst concentration and reaction alkalinity on the yield (b). Standard conditions: 50 mg lignin, 10 mL 2 M NaOH, 1.5 mM CuSO4, and 25 bar air. Reaction was heated from r.t. to 160 °C over 45 min, and then cooled in an ice bath.

Representative screening data, depicted in Figure 2b, highlight the effects of [NaOH] and [CuSO4] and demonstrate that the seven major aromatic products could generated up to ∼30% total yield. The syringyl (S):guaiacyl (G) product ratios closely resemble the composition of the S:G monomer ratios in the original biomass lignin.44

Determination of Partition Coefficients in CPC Solvents

Measurement of partition coefficients (KP) for each solute in biphasic solvent systems provides a means to guide solvent selection for CPC separations. Efforts were initiated with the widely used “Arizona” (AZ) solvent system,45 which features a series of 23 biphasic mixtures composed of alkane (e.g., pentane), ethyl acetate, methanol, and/or water. The mixtures exhibit systematic variations in polarity, ranging from 1:1 ethyl acetate/water (system A, most polar) to 1:1 alkane/methanol (system Z, least polar), and the middle point consists of equal volumes of all four solvents (system N). Ideal solvents for CPC will show values of log(KP) between −0.4 and +0.4 for each of the solutes, in addition to maximizing differences in the individual log(KP) values.46 When these criteria are met, the solutes will equilibrate between the mobile and stationary solvent phases and display effective separation with practical retention times.

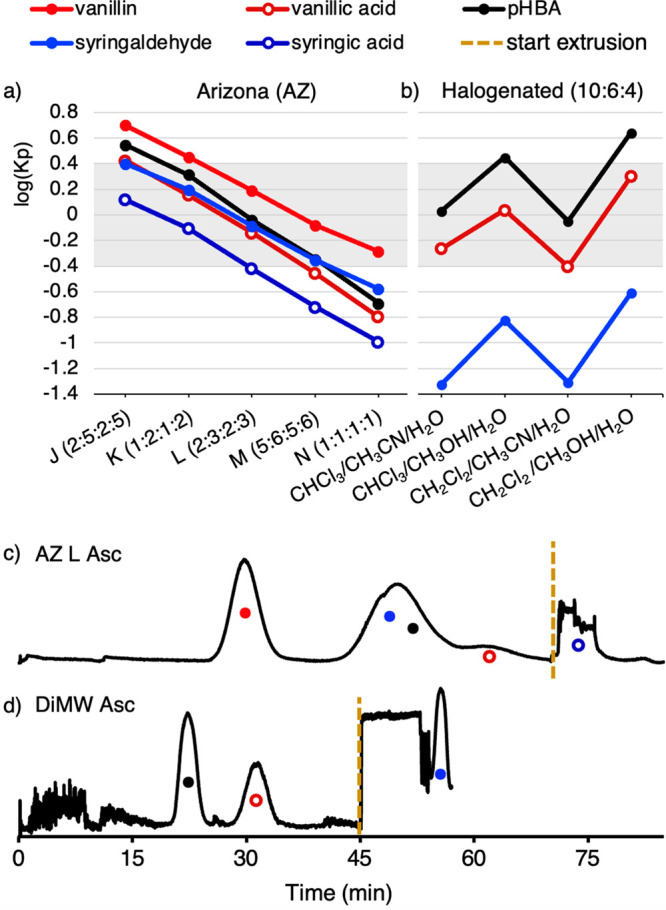

KP values were measured for pHBA, vanillin, vanillic acid, syringaldehyde, and syringic acid with AZ solvent mixtures J–N using shake-flask experiments and HPLC quantitation (Figure 3a; see Figure S3 in the Supporting Information for details). Acetovanillone and acetosyringone were also tested; however, they show similar KP values to vanillin and syringaldehyde, respectively (see Figure S4 in the Supporting Information for details), and we did not attempt resolution of the vanillin/acetovanillone, syringaldehyde/acetosyringone pairs. Each of the five compounds displayed a log(KP) value between −0.4 and +0.4 with solvent system L, consisting of 2:3:2:3 pentane/ethyl acetate/methanol/water. Vanillin and syringic acid show log(KP) values that are sufficiently different from the others (Δlog(KP) > 0.2) to facilitate their separation. The other compounds, pHBA, vanillic acid, and syringaldehyde, have similar log(KP) values that complicate their separation using AZ L as the solvent system.47 Literature precedent suggested that aqueous/halogenated solvent mixtures could be used to separate these three compounds.48

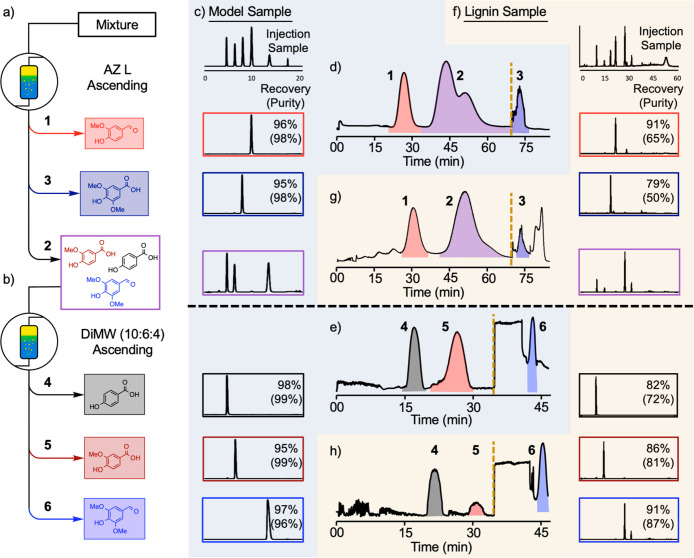

Figure 3.

Partition coefficient data and CPC traces for separation of aromatic monomers obtained from oxidative alkaline depolymerization of Cu-AHP lignin. Log(KP) values for all five aromatic compounds in AZ solvents J–N (pentane:ethyl acetate:methanol:water) (a) and for pHBA, vanillic acid, and syringaldehyde in halogenated solvent systems (b). Stage one CPC separation of a model sample mixture of five aromatics using AZ L Asc mode operation at 1400 rpm and 30 mL·min–1 flow rate (c), and stage two CPC separation of pHBA, vanillic acid, and syringaldehyde using DCM/MeOH/H2O (10:6:4) Asc operation at 1100 rpm and 25 mL·min–1 flow rate (d). CPC traces were generated by monitoring CPC elutions at λ = 200–600 nm.

Measurement of KP values in four solvent mixtures inspired by this precedent showed a Δlog(KP) > 0.2 among all the three components in each case (Figure 3b). A 10:6:4 mixture of dichloromethane (DCM)/methanol/water (DiMW) was selected for this separation, owing to the reduced solvent toxicity and lower density of DCM versus CHCl3, the lower cost of MeOH versus MeCN, and the proximity of the log(KP) values to the desired range of −0.4 to +0.4.

CPC Separation of a Model Product Mixture

The KP data provide the basis for a two-stage separation scheme, initiated with AZ L to isolate vanillin and syringic acid, followed by DCM/MeOH/H2O to obtain pHBA, vanillic acid, and syringaldehyde. Initial CPC testing was conducted with a model mixture containing small quantities (50 mg) of each of the five compounds. The CPC rotor was equilibrated with AZ L solvents in ascending (Asc) mode,49 and the five compounds dissolved in the AZ L lower-layer solvent (predominantly MeOH/H2O) was injected into the CPC. The mobile phase was then eluted at 30 mL·min–1 for 70 min, followed by column extrusion for 15 min (Figure 3c). The AZ L separation showed a resolved peak for vanillin, and pure fractions of syringic acid were obtained during column extrusion. (Note: the complex peak shape for syringic acid reflects emulsions in the effluent that scatter light from the detector during extrusion.)

Syringaldehyde, pHBA, and vanillic acid eluted in the order expected from their KP values (cf. Figure 3a) but were not resolved using the AZ L solvent system. These compounds were therefore transferred to the second stage process. The CPC was prepared for 10:6:4 DiMW Asc mode elution. The mixture of pHBA, vanillic acid, and syringaldehyde was dissolved in the DiMW upper-layer solvent (again, predominantly MeOH/H2O), injected, and the mobile phase was eluted for 45 min at 25 mL·min–1 followed by extrusion for 13 min (Figure 3d). Good separation of the mixture of three compounds using the DiMW solvent system (Figure 3d) completed the two-stage protocol the leads to effective separation of all five solutes.50

This successful demonstration was then applied to larger-scale separation, using a 2 g sample of the five compounds (400 mg each; Figure 4a–e). HPLC was used for quantitative analysis of the compounds following CPC separation. Nearly quantitative recovery and purity (>95%) was obtained for each compound (Figure 4c), consistent with the good resolution of the peaks in the two traces (Figure 4d and e).

Figure 4.

Two-stage separation sequence enabling isolation of aromatic compounds in a model sample and authentic lignin oxidative alkaline depolymerization mixture. (a) The first-stage AZ L Asc separation isolates vanillin (collected peak 1) and syringic acid (collected peak 3) and a mixture of pHBA, vanillic acid, and syringaldehyde (collected peak 2). (b) The second-stage DiMW Asc separation resolves the mixture of pHBA (collected peak 4), vanillic acid (collected peak 5), and syringaldehyde (collected peak 6). (c) Recoveries and purities attained from CPC separation of the model sample mixture. (d) AZ L Asc CPC trace from a model sample mixture. (e) DiMW (10:6:4) Asc CPC trace from a model sample mixture of the compounds present in peak 2 in trace d. (f) Recoveries and purities attained from CPC separation of the authentic lignin depolymerization mixture. (g) AZ L Asc CPC trace from the authentic lignin depolymerization mixture. Peak #1 includes both vanillin and acetovanillone. (h) DiMW (10:6:4) Asc CPC trace from the authentic lignin depolymerization mixture of the compounds present in peak 2 in trace g. Peak #6 includes both syringaldehyde and acetosyringone. Note: The large absorption features in traces e and h after initiating the extrusion phase (indicated by the gold dashed line) correspond to the dichloromethane-rich stationary phase being displaced from the column.

CPC Separation of Lignin Depolymerization Products

The above results provided the basis for CPC separation of products obtained from Cu-AHP lignin depolymerization. A crude 1.6 g mixture, obtained by pooling products of multiple depolymerization reactions, was analyzed by HPLC and shown to consist of 25.5 wt % aromatic monomers, including 4.0 wt % pHBA, 5.0 wt % vanillin, 1.2 wt % vanillic acid, 0.6 wt % acetovanillone, 11.2 wt % syringaldehyde, 2.1 wt % syringic acid, and 1.4 wt % acetosyringone. The HPLC trace of the crude mixture (Figure 4f) shows the presence of numerous small peaks corresponding to unidentified low-molecular-weight products, in addition to a larger peak at long retention times corresponding to oligomers.

This crude depolymerization mixture was subjected to the same CPC workflow used with the model mixture described above (Figures 4a,b,g,h). Use of AZ L Asc conditions in the first stage separated vanillin/acetovanillone51 and syringic acid in 91% and 79% recoveries, respectively, based on HPLC analysis of the collected fractions. Oligomers were also recovered from this stage (see Figure S11 in the Supporting Information for details) but were not analyzed further. The large quantity of impurities in the crude sample (nearly 3/4 of the material consists of undesired products) limits the purity of the obtained compounds to 65 and 50 wt %, respectively. Nonetheless, this outcome reflects major enrichment of vanillin/acetovanillone and syringic acid relative to their composition in the original sample (5.6 and 2.1 wt %, respectively).

The mixture of pHBA, vanillic acid, and syringaldehyde/acetosyringone, which coelute during the first stage, were then subjected to DiMW Asc CPC conditions in the second stage. The fractions obtained from this run enabled isolation of the three compounds in recoveries of 82%, 86%, and 91%, and purities of 72%, 81%, and 87%, respectively. Higher purities of compounds were obtained from this stage due to the removal of most of the impurities during the first-stage separation. In both stages, recovery values could be increased; however, dilute fractions before and after each of the main peaks were rejected to enhance compound purities.

Conclusion

The results described herein demonstrate the use of a two-stage CPC strategy for isolation of enriched or purified aromatic monomers from complex product mixtures obtained following oxidative alkaline depolymerization of lignin. Access to isolated oligomers from the same process presents opportunities to use these materials in other applications, such as biological funneling or the preparation of polyurethanes. The similarity between the product mixtures here to those of other lignin depolymerization methods (e.g., using different plant sources, biomass fractionation methods, and/or depolymerization conditions) suggest that these results have broad implications. Moreover, precedents for large-scale application of liquid–liquid chromatography52−54 suggest this approach warrants serious attention among contemporary lignin valorization efforts.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (DOE Office of Science BER DE-SC0018409) for funding, the NSF (grant CHE-1048642) for use of a Bruker AVANCE 400 NMR spectrometer, and the Bender Fund for use of a Bruker AVANCE III 500 NMR spectrometer.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.1c00729.

Experimental procedures, optimization conditions, NMR spectra, CPC and HPLC traces for separations (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Tuck C. O.; Pérez E.; Horváth I. T.; Sheldon R. A.; Poliakoff M. Valorization of Biomass: Deriving More Value from Waste. Science 2012, 337, 695–699. 10.1126/science.1218930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon R. A. Green and Sustainable Manufacture of Chemicals from Biomass: State of the Art. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 950–963. 10.1039/C3GC41935E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takkellapati S.; Li T.; Gonzalez M. A. An Overview of Biorefinery-Derived Platform Chemicals from A Cellulose and Hemicellulose Biorefinery. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2018, 20, 1615–1630. 10.1007/s10098-018-1568-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak H. R. Biorefineries from the Perspective of Sustainability: Feedstocks, Products, and Processes. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4042–4052. 10.1016/j.rser.2011.07.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ragauskas A. J.; Beckham G. T.; Biddy M. J.; Chandra R.; Chen F.; Davis M. F.; Davison B. H.; Dixon R. A.; Gilna P.; Keller M.; et al. Lignin Valorization: Improving Lignin Processing in the Biorefinery. Science 2014, 344, 1246843. 10.1126/science.1246843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton B. M.; Kasko A. M. Strategies for the Conversion of Lignin to High-Value Polymeric Materials: Review and Perspective. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2275–2306. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi R.; Jastrzebski R.; Clough M. T.; Ralph J.; Kennema M.; Bruijnincx P. C. A.; Weckhuysen B. M. Paving the Way for Lignin Valorisation: Recent Advances in Bioengineering, Biorefining and Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 8164–8215. 10.1002/anie.201510351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarabanko V. E.; Tarabanko N. Catalytic Oxidation of Lignins into the Aromatic Aldehydes: General Process Trends and Development Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2421. 10.3390/ijms18112421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.; Fridrich B.; de Santi A.; Elangoven S.; Barta K. Bright Side of Lignin Depolymerization: Toward New Platform Chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 614–678. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutyser W.; Renders T.; Van den Bosch S.; Koelewijn S.-F.; Beckham G. T.; Sels B. F. Chemicals from Lignin: An Interplay of Lignocellulose Fractionation, Depolymerisation, and Upgrading. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 852–908. 10.1039/C7CS00566K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Abu-Omar M. M. Lignin Extraction and Valorization Using Heterogeneous Transition Metal Catalysts. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 77, 137–174. 10.1016/bs.adioch.2021.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y.; Goes S. L.; Stahl S. S. Sequential Oxidation-Depolymerization Strategies for Lignin Conversion to Low Molecular Weight Aromatic Chemicals. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 77, 99–136. 10.1016/bs.adioch.2021.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bungay H. R. Confessions of a Bioenergy Advocate. Trends Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 67–71. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Li C.; Dai L.; Xu C.; Zhong Y.; Yu F.; Si C. Biomass Fractionation and Lignin Fractionation Towards Lignin Valorization. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4284–4295. 10.1002/cssc.202001491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Questell-Santiago Y. M.; Galkin M. V.; Barta K.; Luterbacher J. S. Stabilization Strategies in Biomass Depolymerization Using Chemical Functionalization. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020, 4, 311–330. 10.1038/s41570-020-0187-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Complementary methods have led to focus on ″lignin-first″ catalytic fractionation that direct access aromatic monomers from lignin in the separation process. See leading refs (17, 18).

- Renders T.; Van den Bosch S.; Koelewijn S.-F.; Schutyser W.; Sels B. F. Lignin-First Biomass Fractionation: The Advent of Active Stabilisation Strategies. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1551–1557. 10.1039/C7EE01298E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Omar M. M.; Barta K.; Beckham G. T.; Luterbacher J. S.; Ralph J.; Rinaldi R.; Román-Leshkov Y.; Samec J. S. M.; Sels B. F.; Wang F. Guidelines for Performing Lignin-First Biorefining. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 262–292. 10.1039/D0EE02870C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Chen C. H.; Liu T.; Mathrubootham V.; Hegg E. L.; Hodge D. B. Catalysis with CuII(bpy) Improves Alkaline Hydrogen Peroxide Pretreatment. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013, 110, 1078–1086. 10.1002/bit.24793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla A.; Bansal N.; Stoklosa R. J.; Fountain M.; Ralph J.; Hodge D. B.; Hegg E. L. Effective Alkaline Metal-Catalyzed Oxidative Delignification of Hybrid Poplar. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 34–43. 10.1186/s13068-016-0442-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z.; Klinger G. E.; Nikafshar S.; Cui Y.; Fang Z.; Alherech M.; Goes S.; Anson C.; Singh S. K.; Bals B.; et al. Effective Biomass Fractionation through Oxygen-Enhanced Alkaline–Oxidative Pretreatment. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 1118–1127. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c06170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das A.; Rahimi A.; Ulbrich A.; Alherech M.; Motagamwala A. H.; Bhalla A.; da Costa Sousa L.; Balan V.; Dumesic J. A.; Hegg E. L.; et al. Lignin Conversion to Low-Molecular-Weight Aromatics via an Aerobic Oxidation-Hydrolysis Sequence: Comparison of Different Lignin Sources. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3367–3374. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiee M.; Alherech M.; Karlen S. D.; Stahl S. S. Electrochemical Aminoxyl-Mediated Oxidation of Primary Alcohols in Lignin to Carboxylic Acids: Polymer Modification and Depolymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 15266–15276. 10.1021/jacs.9b07243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Demir B.; Vázquez Ramos L. M.; Chen M.; Dumesic J. A.; Ralph J. Kinetic and Mechanistic Insights into Hydrogenolysis of Lignin To Monomers in a Continuous Flow Reactor. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3561–3572. 10.1039/C9GC00986H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi A.; Ulbrich A.; Coon J. J.; Stahl S. S. Formic-Acid-Induced Depolymerization Of Oxidized Lignin To Aromatics. Nature 2014, 515, 249–252. 10.1038/nature13867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham G. T.; Johnson C. W.; Karp E. M.; Salvachúa D.; Vardon D. R. Opportunities and Challenges in Biological Lignin Valorization. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 42, 40–53. 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarabanko V. E.; Kaygorodov K. L.; Skiba E. A.; Tarabanko N.; Chelbina Y. V.; Baybakova O. V.; Kuznetsov B. N.; Djakovitch L. Processing Pine Wood into Vanillin and Glucose by Sequential Catalytic Oxidation and Enzymatic Hydrolysis. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2017, 37, 43–51. 10.1080/02773813.2016.1235583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evju H.Process for the Preparation of 3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde. U.S. Patent 4,151,207, April 24, 1979.

- Hocking M. B. Vanillin: Synthetic Flavoring from Spent Sulfite Liquor. J. Chem. Educ. 1997, 74, 1055–1059. 10.1021/ed074p1055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schutyser W.; Kruger J. S.; Robinson A. M.; Katahira R.; Brandner D. G.; Cleveland N. S.; Mittal A.; Peterson D. J.; Meilan R.; Román-Leshkov Y.; et al. Revisiting Alkaline Aerobic Lignin Oxidation. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 3828–3844. 10.1039/C8GC00502H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mota M. I. F.; Rodrigues Pinto P. C.; Loureiro J. M.; Rodrigues A. E. Recovery of Vanillin and Syringaldehyde from Lignin Oxidation: A Review of Separation and Purification Processes. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2016, 45, 227–259. 10.1080/15422119.2015.1070178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S.; Tan E.; Dunn J. B.; Valentino L.; Barry E.; Edano L.; Leon P. I.; Laible P.; Lin Y.; Coons J., et al. Bioprocessing Separations Consortium Three-Year Overview: Technical Advances, Process Economics Influence, and State of the Science, ANL-20/24, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, 2020.

- Major F. W.; Nicolle F. M. A.. Vanillin Recovery Process. U.S. Patent 4,021,493, May 3, 1977.

- Tarabanko V. E.; Chelbina Y. V.; Kudryashev A. V.; Tarabanko N. V. Separation of Vanillin and Syringaldehyde Produced from Lignins. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 127–132. 10.1080/01496395.2012.673671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneault A.; Johnson D. K.; Chornet E. Base-Catalyzed Depolymerization of Lignin: Separation of Monomers. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2007, 85, 906–916. 10.1002/cjce.5450850612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter W.; Müller M.; Englert M.; Hammann S.. Countercurrent Chromatography-When Liquid-Liquid Extraction Meets Chromatography. In Liquid Phase Extraction, Poole C. F., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2020; Chapter 10, pp 289–325. [Google Scholar]

- Humpert D.; Ebrahimi M.; Czermak P. Membrane Technology for the Recovery of Lignin: A Review. Membranes 2016, 6, 42–52. 10.3390/membranes6030042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota M. I. F.; Pinto P. R.; Ribeiro A. M.; Loureiro J. M.; Rodrigues A. E. Downstream Processing of an Oxidized Industrial Kraft Liquor by Membrane Fractionation for Vanillin and Syringaldehyde Recovery. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 197, 360–371. 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenherr S.; Ebrahimi M.; Czermak P.. Lignin Degradation Processes and the Purification of Valuable Products in Lignin – Trends and Applications, Poletto M., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Le Masle A.; Santin S.; Marlot L.; Chahen L.; Charon N. Centrifugal Partition Chromatography a First Dimension for Biomass Fast Pyrolysis Oil Analysis. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1029, 116–124. 10.1016/j.aca.2018.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubuis A.; Le Masle A.; Chahen L.; Destandau E.; Charon N. Centrifugal Partition Chromatography as A Fractionation Tool for the Analysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass Products by Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1597, 159–166. 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos J. H. P. M.; Almeida M. R.; Martins C. I. R.; Dias A. C. R. V.; Freire M. G.; Coutinho J. A. P.; Ventura S. P. M. Separation of Phenolic Compounds by Centrifugal Partition Chromatography. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1906–1916. 10.1039/C8GC00179K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z.; Van Lehn R. C. Solvent Selection for the Separation of Lignin-Derived Monomers Using the Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 7755–7764. 10.1021/acs.iecr.9b06086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. K.; Savoy A. W.; Yuan Z.; Luo H.; Stahl S. S.; Hegg E. L.; Hodge D. B. Integrated Two-Stage Alkaline-Oxidative Pretreatment of Hybrid Poplar. Part 1: Impact of Alkaline Pre-Extraction Conditions on Process Performance and Lignin Properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 15989–15999. 10.1021/acs.iecr.9b01124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault A. P.; Chevolot L. Counter-Current Chromatography: Instrumentation, Solvent Selection and Some Recent Applications to Natural Product Purification. J. Chromatogr. A 1998, 808, 3–22. 10.1016/S0021-9673(98)00121-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen J. B.; Pauli G. F. G.U.E.S.S.—A Generally Useful Estimate of Solvent Systems for CCC. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2005, 28, 2777–2806. 10.1080/10826070500225234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attempts to resolve the mixed fraction with other AZ systems were unsuccessful. See Figures S3 and S4 in the Supporting Information for details.

- Gong C.; Chen T.; Chen H.; Zhang S.; Wang X.; Wang W.; Sun J.; Li Y.; Liao Z. First Separation of Four Aromatic Acids and Two Analogues with Similar Structures and Polarities from Clematis Akebioides by High-Speed Counter-Current Chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2016, 39 (23), 4660–4666. 10.1002/jssc.201600805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascending and descending modes refer to the choice of mobile and stationary phases, as either layer of a biphasic system may serve the purpose of mobile or stationary phase. In the ascending mode, the upper layer mobile phase is pumped into the CPC rotor such that it bubbles up through the denser lower layer stationary phase. In descending mode, the denser lower layer mobile phase is pumped such that it bubbles down through the upper layer stationary phase.

- To avoid potential variations arising from the manual mixing of the DiMW system, the ratios of each solvent in the upper and lower layers of the equilibrated biphasic system were quantified by NMR and coded into the CPC system. See Figure S5 in the Supporting Information for details.

- The vanillin/acetovanillone and syringaldehyde/acetosyringone pairs were not independently separated due to their similar partition coefficients. See Figure S4 in the Supporting Information for details.

- Sutherland I. A.; Booth A. J.; Brown L.; Kemp B.; Kidwell H.; Games D.; Graham A. S.; Guillon G. G.; Hawes D.; Hayes M.; et al. Industrial Scale-Up of Countercurrent Chromatography. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2001, 24 (11–22), 1533. 10.1081/JLC-100104362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorantfy L.; Németh L. F.; Kobács Z.; Rutterschmidt D.; Misek Z.; Rajsch G. Development of Industrial Scale Centrifugal Partition Chromatography. Planta Med. 2015, 81, PW_146. 10.1055/s-0035-1565770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorántfy L.; Rutterschmid D.; Örkényi R.; Bakonyi D.; Faragó J.; Dargó G.; Könczöl Á. Continuous Industrial-Scale Centrifugal Partition Chromatography with Automatic Solvent System Handling: Concept and Instrumentation. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020, 24 (11), 2676–2688. 10.1021/acs.oprd.0c00338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.