Summary

Background

We examined school reopening policies amidst ongoing transmission of the highly transmissible Delta variant, accounting for vaccination among individuals ≥12 years.

Methods

We collected data on social contacts among school-aged children in the California Bay Area and developed an individual-based transmission model to simulate transmission of the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 in schools. We evaluated the additional infections in students and teachers/staff resulting over a 128-day semester from in-school instruction compared to remote instruction when various NPIs (mask use, cohorts, and weekly testing of students/teachers) were implemented, across various community-wide vaccination coverages (50%, 60%, 70%), and student (≥12 years) and teacher/staff vaccination coverages (50% - 95%).

Findings

At 70% vaccination coverage, universal masking reduced infections by >57% among students. Masking plus 70% vaccination coverage enabled achievement of <50 excess cases per 1,000 students/teachers, but stricter risk tolerances, such as <25 excess infections per 1,000 students/teachers, required a cohort approach in elementary and middle school populations. In the absence of NPIs, increasing the vaccination coverage of community members from 50% to 70% or elementary teachers from 70% to 95% reduced the excess rate of infection among elementary school students attributable to school transmission by 24% and 37%, respectively.

Interpretations

Amidst Delta variant circulation, we found that schools are not inherently low risk, yet can be made so with high community vaccination coverages and masking. Vaccination of adults protects unvaccinated children.

Funding

National Science Foundation grant no. 2032210; National Institutes of Health grant nos. R01AI125842 and R01AI148336; MIDAS Coordination Center (MIDASSUP2020-4).

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, schools, vaccination, masks, transmission model, Delta, Alpha

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

A major epidemiological question occupying researchers throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic was whether reopening K-12 schools would seed community outbreaks or result in high burden of disease for teachers, students, and family members. Since then, studies have suggested that in-school transmission was generally low when schools took basic precautions, and that remote instruction poses severe consequences for child mental, social, and educational health. The expansion of the use of mRNA vaccines in individuals aged 12 years and older led to national prioritization for a return to full-time in-person schooling, even as the rise of the highly transmissible Delta variant across the United States, including among schoolchildren, renewed concerns that a return to school could seed outbreaks among students and teachers, particularly in areas with no mask requirements and low vaccination coverages. In the absence of epidemiological evidence of the spread of the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 in schools, transmission models can provide information on various within-school intervention policies and vaccination coverage goals. We searched for studies published in English up to August 21, 2021, with the terms "coronavirus AND model AND school AND vaccination AND Delta AND (mask OR test OR non-pharmaceutical intervention)" in PubMed and medRxiv and identified 0 and 91 results, respectively. However, there remains a need to examine the effect of a spectrum of non-pharmaceutical interventions on within-school transmission, differentiating results across elementary, middle, and high schools and between students and teachers, and accounting for location-specific contexts, such as various vaccination coverages and community contact patterns.

Added value of this study

Using primary data collected on children's social contacts in the California Bay Area, we developed an agent-based SEIR model to simulate SARS-CoV-2 transmission within Bay Area schools and communities. We estimated the additional infections in students and teachers/staff resulting from in-person instruction when various non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) are in place, and under various vaccination coverages and SARS-CoV-2 variants, including the Delta variant. We examined the minimum set of interventions required to maintain total excess infections among students and teachers attributable to school transmission below risk tolerances that may be relevant to decision-makers. We estimated that, under the Bay Area reopening plan (universal mask use, community and school vaccination coverage of 70%), there would be excess infection attributable to school reopening among 3·4-9·5% of elementary students, depending on susceptibility of young children, 4·3% of middle school students, and 1·8% of high school students. At 70% vaccination coverage, universal masking reduced infections by 63% in elementary students, 57% in middle school students, and 78% in high school students, supporting use of universal masking in schools. We found that universal masking in all school levels is necessary to maintain in-school transmission below a risk tolerance of <50 additional cases per 1,000 population, except in high schools where vaccination coverage exceeds 80% or middle schools where vaccination coverage of teachers and students 12 and older exceeds 95%. Achieving lower risk tolerances (e.g., <10 cases per 1,000 population) in schools also required weekly testing or cohorting of students. We found that increasing vaccination coverage of elementary teachers from 70% to 95% can reduce infection among elementary students by 37%.

Implications of all available evidence

Under circulation of the highly transmissible Delta variant, our findings suggest that schools are not inherently low risk, yet can be made so with implementation of basic precautions, including universal masking. Our findings support recommendations made by CDC and CDPH to fully reopen K-12 schools for the fall 2021 semester; encourage high levels of vaccine uptake among eligible students and staff; and maintain mask usage. Schools may consider layering testing or cohorting as additional safety measures, particularly if younger children are equally as susceptible as adults to the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Assessments of the impacts of school closures and risks of reopening continue to be of high priority as more transmissible variants dominate the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.1 While school closures are intended to curb the spread of COVID-19, major risks for children's mental health and educational and social development have been documented2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and studies report low in-school transmission with basic precautions.7, 8, 9, 10 Introduction of vaccines with high effectiveness against infection11, 12, 13, 14 with SARS-CoV-2 reduce the risk of transmission within school environments in two ways. First, community transmission rates—which strongly impact the probability of within-school transmission15—are suppressed in areas with high vaccination coverage, although vaccination coverage remains heterogeneous across school districts.16 Second, teachers and certain students are eligible for vaccination, conferring direct protection against within-school transmission. Prior epidemiological study and model-based risk assessments found that middle and high school populations have higher risk of school-based transmission as compared to elementary students.15,17, 18, 19

Nevertheless, rising rates of the more transmissible Delta variant across the U.S. in early fall 2021,20 particularly in settings with low vaccination rates, raised concerns that a return to schooling would be accompanied by increased risks of transmission,21 particularly among elementary school populations who were not yet eligible for vaccination. While our understanding of the natural history parameters for children is limited to the parent strain and thus evolving with continued Delta circulation, elementary-aged students (aged 5-10) may be less susceptible to infection than older children and adults.22, 23, 24, 25 Further, children under 18 have milder outcomes than adults,26 and exhibit extremely low fatality rates from SARS-CoV-2 (2 deaths per million by one estimate27) even among children with comorbidities.27 However, there is evidence that Delta's enhanced infectivity is increasing rates of infection among U.S. children, concurrent with the launch of the fall 2021 semester, especially in areas with low vaccination coverage and no mask mandates,28 and outbreaks among school and child care populations have been documented.19,29, 30, 31 While most cases in children are mild, there are rare but serious cases of long-term sequelae that persist after COVID-19 infection in children, including Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome (MIS),32 which often requires intensive care and may result in heart failure, respiratory disease, or other neurological or renal abnormalities.33 Large studies report that as many as 14-36% of children who test positive for COVID have symptoms—commonly headaches, fatigue, and insomnia—nine to 15 weeks after testing positive.32,34

Guidance issued late summer 2021 from the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) as well as the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) urged K-12 schools to fully reopen for instruction during the fall 2021 semester with masks required indoors for all students and staff.35,36 Spacing of at least three feet between students is also recommended, but if this cannot be achieved, it is recommended to apply layers of additional prevention measures, such as additional asymptomatic testing, symptom screening, or hand washing.

In March of 2020, the California Bay Area was among the first in the nation to close schools, moving the 2020 spring semester to remote instruction.37 As of June 2021, California remained the state with the lowest percentage of students engaged in in-person instruction,38 and large Bay Area school districts, including San Francisco and Oakland, launched very limited in-person activities from April to June of 2021. Previous work has estimated the effect of initial closure for the 2020 spring semester on COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths in students, teachers, family members, and community members, and has examined the effect of reopening under various strategies on COVID-19 outcomes across a new four-month semester.15 Here, we examine questions surrounding school reopening in the context of an increasingly vaccinated population of individuals 12 years and older. We expand a previously published model15 to include vaccination of adults in the community, teachers/staff, and students aged 12 years and older in order (the population eligible at the start of the fall 2021 semester) to examine which additional prevention measures beyond vaccination are required to limit excess cases to fewer than two student cases per school (<50% probability of a case per month).39 We also estimate whether achieving high levels of within-school vaccination coverages for teachers and students over 12 years would allow schools to safely drop additional prevention measures while maintaining low transmission. Finally, we quantify the additional benefit of universal masking compared to masking only among the unvaccinated, as a function of varied vaccine effectiveness. We examine scenarios assuming circulation of the highly transmissible Delta variant, and compare to outcomes estimated for the Alpha variant.

Methods

We adapted a previously described agent-based model15 to estimate the effect of fall 2021 reopening strategies under various vaccination coverages and SARS-CoV-2 variants, including the highly transmissible Delta variant. The model was informed by longitudinal data collected on children's social contacts, including data on post-vaccination contact rates of children and their adult family members during spring 2021 school closures.

Survey methodology and analysis

To parameterize community contact rates among the school-aged population and their adult family members within the model, we implemented a social contact survey of school-aged children in nine Bay Area counties (Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano, Sonoma), as described elsewhere.15 Survey respondents (one adult per household) reported the number and location of non-household contacts they and all of their children made within six age categories (0–4, 5–12, 13–17, 18–39, 40–64 and 65+ years) throughout the day prior. A contact was defined as an interaction within six feet lasting over five seconds.40 Eligible households contained at least one school-aged child (pre-kindergarten to grade 12). We recruited participants using an online panel provider (Qualtrics) to be representative of Bay Area on the basis of race/ethnicity and income. The survey was implemented between February, 8 – April 1, 2021, when most (92%) of children were in remote schooling, and during a period where Bay Area healthcare workers, educators, and emergency personnel were eligible for COVID-19 vaccination.

Transmission model

We generated 1,000 synthetic populations representative of the demographic composition of major Bay Area cities,41 in which we assigned each individual an age, household, and occupation status (student, teacher, school staff, other employment, not employed), as well as membership in a school or workplace. We separated schools into elementary (grades K–5; ages 5-10 years), middle (grades 6-8; ages 11-13) and high (grades 9-12; ages 14-17) schools, and assigned individuals grades and classrooms within each school, based on age. All individuals interacted with all other individuals in one of six ways, according to a hierarchy of highest shared membership: household > classroom or workplace > grade > school > community.42 Age-specific community contact rates used in the simulation were obtained from surveys of households where at least one adult was vaccinated, as these individuals from these households had higher contact rates than individuals from unvaccinated households.

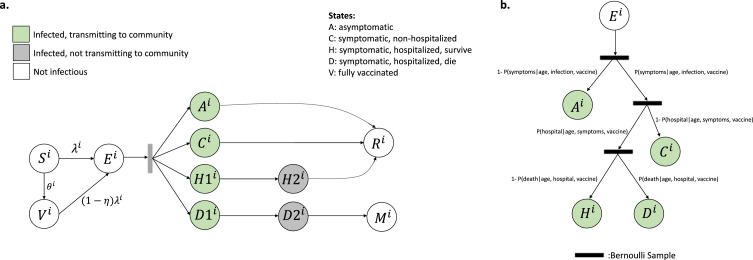

A discrete-time, age-structured, individual-based stochastic model was used to simulate SARS-CoV-2 transmission dynamics in the synthetic population (Fig. 1A). At each time increment (one day), each individual was associated with an epidemiological state: fully vaccinated (V), susceptible/unvaccinated (S), exposed (E), asymptomatic (A), symptomatic with non-severe illness (C), symptomatic with severe illness (H1, D1) resulting in eventual hospitalization before recovery (H2) or hospitalization before death (D2), recovery (R) or death (M). Transmission was implemented probabilistically for contacts between susceptible (S) or vaccinated (V) and infectious individuals in the asymptomatic (A) or symptomatic and non-hospitalized states (C, H1, D1). Movement of a susceptible, unvaccinated individual i on day t to the exposed class was determined by a Bernoulli random draw with probability of success given by the force of infection, :

| (1) |

where N is the number of individuals in the synthetic population (N=16,000) and is the ratio of the transmissibility of asymptomatic individuals to symptomatic individuals. Once in the exposed state, the durations of time spent in each disease stage were sampled from Weibull distributions (Table S1). Vaccines were modelled by adjusting agents’ susceptibility to infection, probability of developing symptoms after being infected, and probability of developing severe disease after being infected (Supporting Information). The disease progression track followed by each individual after infection (e.g., asymptomatic, symptomatic, hospitalized-survived, hospitalized-died) was determined by Bernoulli random draws at the start of each simulation based on probabilities conditional on age and vaccination status (Fig. 1B; Table S1). Using estimates from studies evaluating risk of symptoms by age,24 we assumed 21% of infected individuals <20 years and 69% of infected individuals 20 years and older experienced symptoms.24 Following previous meta-analysis,43 we assumed to 0.5, as asymptomatic individuals may be less likely to transmit infectious droplets by sneezing or coughing.44

Figure 1.

Model schematic (a) Schematic of the agent-based susceptible–exposed–infected–recovered (SEIR) model. Individuals, i, move through states S, susceptible; E, exposed; A, asymptomatic; C, symptomatic, will recover; H1, symptomatic and will recover, not yet hospitalized; H2, hospitalized and will recover; D1, symptomatic, not yet hospitalized; D2, hospitalized and will die; R, recovered; M, dead; and V, vaccinated. The force of infection, λ, defines movement from S to E; η represents vaccine effectiveness; and θ, vaccination coverage among subgroup to which individual i belongs. After an agent enters the exposed class, they enter along their predetermined disease progression track, with waiting times between stage progression drawn from a Weibull distribution. V. (b) Schematic of the conditional probabilities by which agents are assigned a predetermined track. Figure is adapted, with permission, from [15].

Based on an average of R0 for the Alpha (R0 = 2·5) and Delta (R0 = 5) variant weighted by the proportion of circulating variants in summer 2021,45,46 we calculated R0 as 4·6 and solved for the mean transmission rate of the pathogen, , as the ratio between R0 and the product of the infection duration and the weighted mean number of daily contacts per individual during the pre-intervention period (Supporting Information, equation 3).47 To understand the influence of the Delta variant, we also ran simulations assuming full coverage of the Alpha variant. To represent age-varying susceptibility,24 we then calculated an age-stratified , that incorporated varying relative susceptibility by age while permitting the population mean to be (Supporting Information, equations 4-5). We assumed that children under 10 years of age are half as susceptible to infection as older children and adults, in accordance with prior meta-analysis and modelling work reporting lower household secondary attack rates in children as compared to adults,22, 23, 24, 25 with the lowest secondary attack rates in children less than 10 years of age.22,25 Nevertheless, given that some studies report equal susceptibility across all ages,48, 49, 50 and our current understanding of susceptibility is based largely on the Alpha variant, we also modeled scenarios without age-dependent susceptibility.

The daily contact rate between individuals i and j on day t, , was estimated for pairs of individuals following previous study42 based on their type of interaction (e.g., household, class, community). Contact rates were scaled by a time-dependent factor between 0 (complete closure) and 1 (no intervention) representing a social distancing intervention to reduce contact between individual pairs. Pairs with a school or workplace interaction were reassigned as community interactions under closures. Because symptomatic individuals mix less with the community,51 we incorporated isolation of symptomatic individuals and quarantine of their household members. Following prior work, we simulated a 100% reduction in daily school or work contacts and a 75% reduction in community contacts for a proportion of symptomatic individuals, and an additional proportion of their household members.52,53 This means that a proportion of students and staff would stay home from school if they themselves were symptomatic, while a smaller percentage would stay home from school if one of their household members was symptomatic. We assumed that individuals were in the infectious class for up to three days prior to observing symptoms,54, 55, 56 during which time they did not reduce their daily contacts.

To establish the initial conditions for a new school semester, we simulated transmission continuously throughout three phases: 1) initiation of pandemic (schools open); 2) start of NPI enactment (schools closed for in-person instruction); 3) continuation of pandemic and NPIs across a long-term school closure period. This yielded a distribution of initial conditions, one for each instance of the synthetic population. The simulated infection rates at the start of the semester ranged from 6-120 cases per 100,000, in accordance with infection rates among Bay Area counties in early August, 2021.57 The simulated infection seroprevalence at the start of the semester ranged from 1·5 to 10%, in line with seroprevalence data from San Francisco in late summer, 2020.58 Prior to simulating transmission over the school semester, a proportion of susceptible individuals aged 12 and older (the population eligible for vaccination at the start of the fall 2021 semeter) were moved to the vaccinated compartment, according to a Bernoulli random draw with probability of success equal to the proportion vaccination coverage among the eligible population, and the disease progression tracks that the vaccinated individuals would follow post infection were updated (Supplemental information, equations 6-7). For most simulations, vaccine effectiveness was 77% against any infection,59 85% against symptomatic infection,60 and 93% against severe infection.61 To account for lower effectiveness due to waning immunity or new variants, we also explored scenarios with lower effectiveness.

Interventions

Effect of within-school non-pharmaceutical interventions under various community vaccination coverages

We examined the effect of three non-pharmaceutical interventions across three levels of community vaccination coverage (50%, 60%, 70%), assuming that vaccination coverage within school children 12 years and older and teachers matches that in the community. First, we examined universal masking, assuming that the effectiveness of masks for reducing both inward and outward transmission62 is 15% for elementary school students, 25% for middle school students, 35% for high school students, and 50% for teachers and staff.63, 64, 65 Second, we examined a scenario of masking plus weekly testing of all students and teachers, in which we assumed a test with 85% sensitivity was administered every 7 days with 1 day to get results back.66 We then assumed that the classroom and the household members of a positive test stayed home from school/work for 14 days and reduced community contacts by 75%. Third, we examined a masking plus cohort scenario in which classroom groups of 20 students were assumed to contact each other freely, with individuals within the cohort reducing their contacts with individuals outside their cohorts by 75%. While all of the nine Bay Area counties have achieved vaccination coverages of at least 60% as of summer, 2021, and some over 80%,67 we include the lower 50% to make the findings more generalizable to areas outside the Bay Area who may otherwise have similar demographics. Results with vaccination coverages above 70% are included in the supplement.

Effect of increasing vaccination among the school population in the absence of other interventions

Next, we considered within-school vaccination coverage in the absence of within-school NPIs (masking, testing, cohorting). We assumed a community vaccination coverage among the eligible population of 70%, which represented a conservative level of vaccination coverage among a Bay Area county.67 We then examined COVID-19 outcomes if students 12 and older and teachers/staff had higher vaccination coverages (ranging from 70% to 95% coverage).

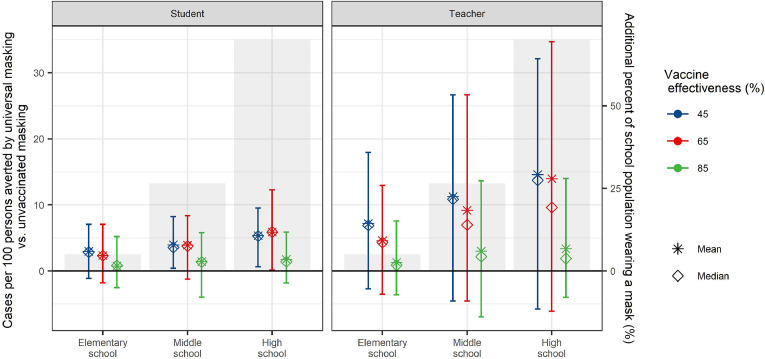

Effect of masking all individuals in a school compared to masking only unvaccinated individuals

Finally, we estimated the additional cases averted in each population by masking the entire student and teacher population, compared to masking only the unvaccinated student and teacher population, in the absence of additional interventions. We held community and within-school vaccination coverage of the 12+ population at 70%, and varied vaccine effectiveness from low (41% any infection, 45% symptomatic infection, 49% severe infection) to medium (59% any infection, 65% symptomatic infection, 71% severe infection) to high.

Outcomes

We evaluated two primary outcomes. Our first primary outcome was the increase in the total number of symptomatic infections among students and teachers/staff between in-school and remote instruction over a 128-day semester. We refer to this outcome as the excess symptomatic infections attributable to school transmission. We also examined the increase in the total number of all infections and hospitalization among students and teachers over the 128-day period between in-school and remote instruction.

Our second primary outcome was the minimum set of interventions required to maintain total excess infections among students and teachers attributable to school transmission below risk tolerances that may be relevant to decision-makers. We considered three school population-based risk tolerances, that varied in leniency from <10 to <50 additional cases per 1,000 school population. Following prior study, we examined a school-based risk tolerance of a monthly probability of an in-school transmission below 50% (<2 excess cases per school).39

We examined outcomes among population subgroups, focusing on students and teachers/staff, stratified by schooling level. We summarized all outcomes using the mean, median, and the 89th percentile highest probability density interval (HPDI) across the 1,000 model realizations. 89% intervals are deemed to be more stable than the 95% intervals.68,69

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Office for Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California, Berkeley (Protocol Number: 2020-04-13180). Prior to taking the anonymous survey, parents were provided details of the study and asked to provide written informed consent.

Role of the funding source

The funding source played no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Effect of within-school precautions under various community vaccination coverages (children under 10 years half as susceptible to infection)

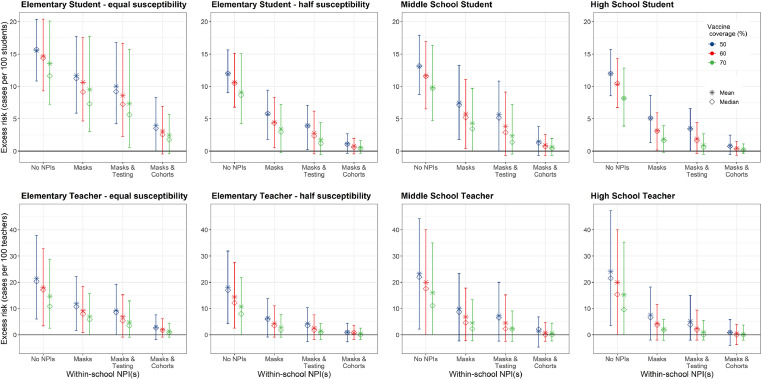

We estimated higher rates of excess illness among elementary and middle school students as compared to high school students across all combinations of NPIs tested (Table 1; Table S6; Fig. 2). Excess illness was also higher among elementary and middle school teachers, as compared to high school teachers, but differences between schooling levels were smaller among teachers as compared to students (Table S6; Fig. 2). Increasing community and school vaccination coverage reduced excess illness attributable to school transmission among all populations, but particularly among the fall 2021 vaccine-eligible population (i.e., teachers and high school students) (Fig. 2), both in the absence and presence of additional NPIs.

Table 1.

The number of excess student cases attributable to school transmission expected across a four-month (128-day) semester, for 70% community vaccination coverage, which is seen in most Bay Area counties.67 The mask row is highlighted to demonstrate the current minimum required scenario for schools within the Bay Area.

| Excess student cases attributable to within-school transmission within: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 380-person elementary schools | 380-person elementary schools | 420-person middle schools | 620-person high schools | |

| (half susceptibility) | (equal susceptibility) | |||

| No precautions | 35 cases per school | 51 cases per school | 41 cases per school | 56 cases per school |

| Universal masking | 13 cases per school | 36 cases per school | 18 cases per school | 12 cases per school |

| Masks + testing | 7 cases per school | 28 cases per school | 10 cases per school | 6 cases per school |

| Masks + cohorts | 2 cases per school | 9 cases per school | 3 cases per school | 2 cases per school |

Figure 2.

Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions. We examined the effect of three non-pharmaceutical interventions across three levels of community vaccination coverage (50%, 60%, 70%), assuming that vaccination coverage within school children 12+ and teachers matches that in the community and the vaccine effectiveness is 77% against infection, 85% against symptomatic infection, and 93% against severe infection. Masks indicate universal masks regardless of vaccination status. We calculated the mean (stars) and median (diamonds) of excess cases per 100 persons attributable to school transmission among population subgroups across 1,000 model realizations. Vertical lines reflect the 89thpercentile high probability density interval (HPDI).

Upon achieving a 70% community vaccination coverage or higher (the coverage observed in May 2021 in most Bay Area counties)67 and without additional NPIs, we estimated the average excess incidence rate as between 8-10 symptomatic cases per 100 students across all age groups (Fig. 2). Expressed as excess cases per school attributable to school transmission, this amounts to an estimated 55 excess cases per high school, 41 excess cases per middle school, and 37 excess symptomatic cases per elementary school across a 128-day semester (Table 1). Tables S2-3 display results for 50% and 60% vaccine coverage. Full results for symptomatic and asymptomatic infection are included in Tables S6-7, and Fig. S1 displays results for vaccine coverages of 80% and 100%.

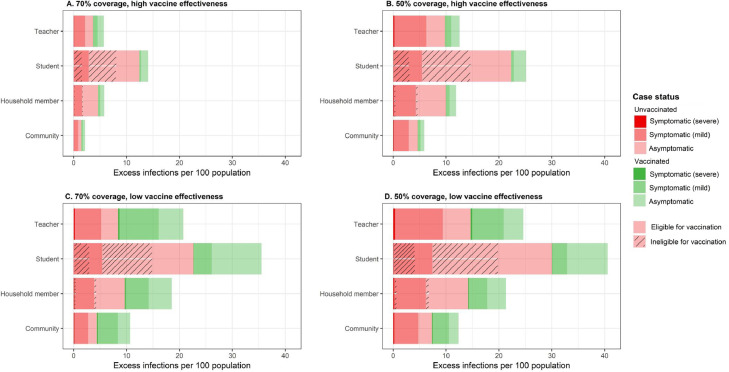

Under the most likely reopening scenario for Bay Area schools – dominant circulation of the Delta variant, vaccination coverages of at least 70% and universal masks (Table 1) – we estimated an excess of 13 symptomatic cases per elementary school, 18 cases per middle school, and 12 cases per high school attributable to school transmission over a 128-day semester. This equates to school-attributable illness in an additional 3·4% of elementary school students, 4·3% of middle school students, and 1·8% of high school students owing to school transmission. We estimated that an additional 2·8% of elementary school teachers, 4·5% of middle school teachers, and 2·1% of high school teachers would experience symptomatic infection attributable to school transmission across a semester. Of these symptomatic infections among teachers, 71% were estimated to occur among unvaccinated teachers (Fig. 3A), while 84% of severe infections among teachers were estimated to occur among unvaccinated teachers. Nearly 90% of all infections among children were estimated to occur among unvaccinated children (Fig. 3A). The fraction of cases occurring among the unvaccinated population increased with lower vaccination coverages (Fig. 3B) and decreased with lower vaccine effectiveness (Fig. 3C-D).

Figure 3.

Share of the excess risk by vaccination status and disease outcome, across various vaccine coverages and effectiveness and populations. Red colors reflect the share of excess infections among unvaccinated persons, while green represents excess infection among vaccinated persons. Dark hues represent severe disease (i.e., needing hospitalization), medium hues represent symptomatic but not severe infection, and light hues represent asymptomatic infection. Hashes on the student and the household members represent infections among unvaccinated individuals who are ineligible for vaccination at the start of the fall 2021 semester (<12 years). The high vaccine effectiveness scenario (panels A, B) models vaccines that are 77% effective against any infection, 85% effective against symptomatic infection, and 93% effective against severe infection. The low vaccine effectiveness scenario (panels C, D) models vaccines that are 41% effective against any infection, 45% effective against symptomatic infection, and 49% effective against severe infection.

While children <12 years were ineligible for vaccination at the start of the fall 2021 semester, increasing vaccination among the community and teachers lowered risk of asymptomatic and symptomatic illness among young children. As simulated community vaccination coverage of the eligible population increased from 50% to 60% to 70%, we estimated that the expected percent of elementary school children with a school-attributable symptomatic illness fell from 11·9% to 10·6% to 9·1%, representing a 23·5% decline in school-attributable transmission. This suggests that adult-to-child transmission represents an important source of school-attributable illnesses (Fig. 2). Under the current reopening plan, the excess rate of symptomatic infection and severe infection among household members of students was estimated to be 1·76 and 1·14 times that of other community members, respectively, suggesting that having a school child in the home would increase the risk of symptomatic infection to household members by 76% and the risk of severe infection by 14% (Fig. 3A; Table S9).

Within-school NPIs were most effective at reducing excess symptomatic cases within elementary and middle schools regardless of levels of community vaccination coverage, and within high schools with lower community vaccination coverages (Fig. 2). For instance, where community vaccine coverage was 50% and no additional NPIs were taken, we estimated an excess incidence of 11·9 cases (89% HPDI: 9·0, 15·6) per 100 students in elementary schools, 13·1 (89% HPDI: 8·8, 17·9) per 100 students in middle schools and 12·0 per 100 students in high schools (89% HPDI: 8·6, 15·7). Adding masks but holding vaccine coverage constant, we estimated an excess incidence of 5·7 cases (89% HPDI: 1·8, 5·9) per 100 elementary students, 7·5 cases (89% HPDI: 1·8, 13·3) per 100 middle school students, and 5·1 (89% HPDI: 1·3, 8·4) cases per 100 high school students.

While estimated hospitalizations and deaths were rare among students across all model interventions scenarios and school levels (median of zero for all but two scenarios, Table S8), we estimated a non-zero mean hospitalization rate for all scenarios. We simulated the highest estimated hospitalization rates among students of all grade levels when no NPIs were modelled. The maximum hospitalization rate simulated was 12·6 hospitalizations per 100,000 middle school students over the 128-day semester, under 50% vaccination coverage and no additional precautions. and 12·9 hospitalizations per 100,000 elementary school students, under the same conditions, assuming elementary children are equally susceptible to infection as older children and adults. Simulated interventions combining masks and cohorts yielded hospitalization rates for the four-month semester under 1 per million students, regardless of assumptions about susceptibility.

We estimated higher hospitalization rates among teachers and other school staff as compared to students. Under a 70% vaccine coverage scenario, excess hospitalizations among teachers was 42·2 per 100,000 teachers over the 128-day semester (daily rate: 0·33 per 100,000) without NPIs (Table 2). With the current universal mask recommendation, the excess hospitalization rate was 9·0 per 100,000 teachers per semester, or 0·07 per 100,000 per day. Adding a cohort approach to masking reduced the estimated excess hospitalization rate to 2·3 per 100,000 teachers per semester.

Table 2.

The excess risk of hospitalization among all teachers (regardless of grade level) across a four-month school semester attributable to school transmission, depending on community vaccine coverage and modelling assumptions. Yellow row indicates the most likely scenario for the Bay Area fall 2021 reopening.

| NPIs | 50% coverage | 60% coverage | 70% coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization rate (per 100,000) | |||

| None | 75·5 per 100,000 | 61·5 per 100,000 | 42·2 per 100,000 |

| Universal masking | 25·4 per 100,000 | 16·9 per 100,000 | 9·0 per 100,000 |

| Masks + testing | 19·7 per 100,000 | 11·9 per 100,000 | 5·2 per 100,000 |

| Masks + cohorts | 5·0 per 100,000 | 2·8 per 100,000 | 2·3 per 100,000 |

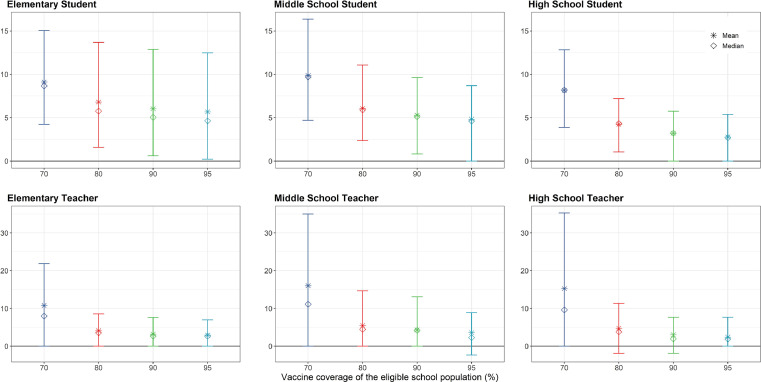

Effect of increasing vaccination among the school population in the absence of other interventions

We examined under what vaccination coverages, if any, it might be possible to have a return to schooling without any additional NPIs (Fig. 4). Increasing vaccination coverage of the eligible school population from 70% to 95% reduced mean estimates of excess cases among elementary students, suggesting that increasing vaccination coverage among elementary school teachers can reduce the force of infection among their students. For instance, increasing the vaccination coverage of the eligible school population (here, teachers) from 70% to 95% reduced the estimated excess rate of infection from 9·1 (89% HPDI: 4·3, 15·0) to 5·7 (89% HPDI: 0·2, 12·5) symptomatic cases per 100 elementary students across the four-month semester, representing a reduction of 37%. At the same time, increasing vaccination of teachers/staff from 70% to 95% reduced the estimated excess rate of infection among elementary teachers from 10·8 (89% HPDI: 0, 21·8) to 2·9 (89% HPDI: 0, 7·0) symptomatic cases per 100 teachers across the four-month semester, representing a reduction of 73%.

Figure 4.

Effect of increasing within-school vaccination coverage. We examined the effect of increasing vaccination coverage among school populations, in the absence of additional non-pharmaceutical interventions, and holding community and within-school vaccination coverage of the 12+ population at 70%. We calculated the mean (stars) and median (diamonds) of excess risk per 100 persons attributable to school transmission among population subgroups across 1,000 model realizations. Vertical lines reflect the 89thpercentile high probability density interval (HPDI).

While increasing within-school vaccine coverage indirectly reduced infections among elementary and middle school students, the effect of increasing within-school vaccination coverage was most pronounced among high school students and teachers of all grade levels. Compared to other schooling levels, high school teachers and students achieved the lowest rates of infection attributable to school transmission using vaccination only without NPIs (Table 3). At 70% coverage of the eligible school population, we estimated an excess of 8·2 (89% HPDI: 3·9, 12·8) symptomatic cases per 100 high school students and 15·2 (89% HPDI: 0, 35·3) per 100 teachers across the 128-day semester, and at 95% coverage an excess of 2·7 (89% HPDI: 0, 5·4) cases per 100 students and 2·4 (89% HPDI: 0, 7·7) per 100 teachers across the 128-day semester (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

The minimum non-pharmaceutical intervention(s), or minimum within-school vaccination coverage of the eligible population, needed to reduce the risk of symptomatic infection to beneath a given risk level (e.g., 50 cases per 1,000 population), assuming that 70% of the fall 2021 vaccine-eligible (12+) community has received a vaccine at 85% effectiveness. ‘Not observed’ indicates that no combination of interventions examined in this study reduced excess risk beneath the indicated threshold. Masks refers to universal masking regardless of vaccination status.

| Population-wide risk tolerance — symptomatic cases per 1,000 population |

School-based risk tolerance — < 2 cases per school* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 | <25 | <10 | |||

| Students | Elementary school – half susceptibility | Masks | Masks + testing | Masks + cohorts | Masks + cohorts |

| Elementary school – equal susceptibility | Masks + cohorts | Masks + cohorts | Not observed⁎⁎ | Not observed⁎⁎ | |

| Middle school | Masks or 95% coverage | Masks + testing | Masks + cohorts | Not observed⁎⁎ | |

| High school | Masks or 80% coverage | Masks | Masks + testing | Masks + cohorts | |

| Teachers/staff | Elementary school – half susceptibility | Masks or 80% coverage | Masks + testing | Masks + cohorts | |

| Elementary school – equal susceptibility | Masks + testing | Masks + cohorts | Not observed⁎⁎ | ||

| Middle school | Masks or 90% coverage | Masks + testing | Masks + cohorts | ||

| High school | Masks or 80% coverage | Masks or 95% coverage | Masks + testing | ||

Assuming a 380-person elementary school, 420-person middle school, and 680-person high school.

Not observed under the interventions examined here.

Interventions required to reduce incidence attributable within schools below certain risk tolerances

We examined whether layering NPIs or increasing within-school vaccination could reduce incidence attributable to school transmission below specific risk tolerances (Table 3). We estimated that universal masking and 70% community and within-school vaccination coverage or higher could reduce the number of excess cases attributable to school transmission to <50 per 1,000 students and teachers across all grade levels. In high school students, increasing the vaccine coverage among the vaccine-eligible school population above 80% could also reduce excess transmission to <50 per 1,000 students and teachers in the absence of NPIs. However, achieving lower risk levels among elementary school students—e.g., <10 cases per 1,000 students or teachers—required additional NPIs, such as testing or cohorts, and was not achievable through the NPIs investigated here if children under 10 years are equally as susceptible as adults. On a per school basis, reducing the excess cases attributable to school transmission to fewer than two cases per school across the full semester (i.e., <50% probability of a case per school per month) required both masks and cohorts. Tables S4-5 display the minimum NPIs required to achieve the various risk tolerances assuming 50% and 60% vaccine coverage in the eligible community, respectively.

Effect of masking all individuals in a school compared to masking only unvaccinated individuals

We compared the differences in school-attributable transmission under scenarios where only unvaccinated individuals wore masks compared to if all individuals masked, across different levels of vaccine effectiveness (VE), assuming 70% of the eligible population is fully vaccinated (Fig. 5). Since all elementary students are unvaccinated, such a rule would change behaviors only among the vaccinated teachers, about 5% of the overall school population. In contrast, such a rule would affect the entirety of the vaccinated high school population, both students and teachers, about 70% of the overall school population. The difference between masking the entire student and teacher population as compared to only the unvaccinated school population is thus most apparent in middle and high school populations, and at lower VEs. For instance, given 45% VE, masking all middle and high school students and teachers would avert symptomatic infection for 4·0% of middle school students, 5·4% of high school students, 1·2% of middle school teachers, and 14·6% of high school teachers compared to masking only unvaccinated students and teachers. At 85% VE, masking all students and teachers would avert symptomatic infection for 1·4% of middle school students, 1·7% of high school students, 3·0% of middle school teachers, and 3·4% of high school teachers compared to masking only unvaccinated students and teachers.

Figure 5.

Effect of universal masking compared to masking only of unvaccinated individuals. We estimated the additional cases averted in each population by masking the entire student and teacher population, compared to masking only the unvaccinated student and teacher population, in the absence of additional interventions. We held community and within-school vaccination coverage of the 12+ population at 70%, and varied vaccine efficacy (VE). We calculated the mean (stars) and median (diamonds) of excess risk per 100 persons attributable to school transmission among population subgroups across 1,000 model realizations. Vertical lines reflect the 89thpercentile high probability density interval (HPDI). Shaded bars and right axis reflect the vaccinated percent of the school population, for whom a universal masking rule as compared to a masking rule among the unvaccinated would apply.

Key uncertainties

Relative susceptibility of children to infection and infectiousness of asymptomatic individuals

We found that the excess risk in elementary schools is substantially altered if children under 10 years of age are considered equally as susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 as older children and adults when compared with half as susceptible (Fig. 2; Tables 1 and 3). Under the current Bay Area reopening scenario (70% coverage + masks), the estimated number of within-school infections due to school transmission jumps from 13 to 36 cases per 380-person elementary school over the four-month semester under equal susceptibility assumptions. This corresponds to excess illness attributable to schools among 9·5% (89% HPDI: 3·0, 17·8%) of elementary students and among 6·9% (89% HPDI: 0, 15·7%) of elementary teachers. The strictest combination of interventions tested (masks + cohorts, 70% vaccine coverage), would result in excess infection among 2·4% (89% HPDI: -0·4, 5·7) of elementary students, and 1·2% (89% HPDI: -0·9, 4·4) of elementary teachers.

Estimated excess risk was also sensitive to the relative infectivity of asymptomatic individuals to symptomatic individuals (denoted as in Equation 1), although to a lesser degree than to assumptions about susceptibility. We examined the effect of various interventions when was equal to 30% rather than 50% (Tables S10-13, Fig. S2). Under this assumption and the current Bay Area reopening scenario, the estimated number of symptomatic cases attributable to school transmission fell from 13 to five cases per elementary school, 18 to eight cases per middle school, and 12 to four cases per high school, representing an excess rate of symptomatic infection of 0·7-2·0 per 100 students.

The relative susceptibility of younger children to infection as well as the relative infectiousness of asymptomatic individuals remains under debate, and the natural history parameters for emerging variants is evolving. Should younger children be as susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 as older children and adults, masking alone may not be sufficient to achieve low rates of transmission among elementary school populations. At the same time, should asymptomatic individuals be less efficient at transmitting infection, achievement of low risk tolerances may be more easily achievable.

Circulating variants of concern

Our results were highly sensitive to the proportion of variants of concern circulating. We examined outcomes if the Alpha variant had remained the dominant variant (R0 = 2·5), finding school attributable excess transmission to be nearly ten times lower than under circulation of the Delta variant when examining the most likely reopening scenario for this fall (70% vaccine coverage and universal masks) (Fig. S3; Table S14). Under this scenario, we estimated fewer than one additional infection per school (<25% probability of an in-school transmission per month). At the level of community vaccination coverage observed in the Bay Area (70% coverage or higher), the most lenient risk tolerance of <50 additional cases per 1,000 students, was achievable without additional NPIs (Table S14; Fig. S3). Under this no-NPI scenario, risk to the student population was estimated at 1 excess case per high school, 4 excess cases per middle school, and 1-5 excess cases (depending on susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2) per elementary school. We estimated that high schools could achieve very strict risk tolerances (<1 excess cases in 1,000 students) without any additional NPIs as long as vaccination coverage among the eligible school population exceeded 75% (Table S15).

We also projected fewer hospitalizations and deaths if the Alpha variant had remained the dominant variant. Under full circulation of the Alpha variant, we did not observe hospitalizations among students and observed very few hospitalizations among teachers within our model realizations. Under a 70% vaccine coverage scenario, excess hospitalizations among teachers was 23 per 100,000 (daily rate: 0·19 per 100,000) without any NPIs. When any school interventions were present (e.g., masking) under a 70% vaccine coverage scenario, our model realizations observed fewer than 1 excess teacher hospitalization per 100,000 teachers attributable to school transmission over the semester.

Discussion

We simulated transmission of the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 in schools with variable vaccine coverages within the school and community populations to approximate conditions that may be observed in the fall of 2021. Aligning with CDPH and CDC reopening guidelines,35 which urged a full return to in-person schools with vaccination and universal mask usage, we estimated that an additional 1·8 to 4·3% of students, depending on schooling level, would experience symptomatic illness attributable to schools across a four month semester, with similar rates estimated for teachers. Under these scenarios, we estimated a daily school-attributable hospitalization rate as 0·07 per 100,000 teachers per day (Table 2). Vaccination is recognized by the CDC and CDPH as the leading public health strategy for reducing within-school transmission,35,36 and our results highlight that increased vaccination coverage—both among the general community and among the eligible school population—plays an essential role in limiting symptomatic illness attributable to school transmission.

Our findings support the use of universal masks as precaution within schools, particularly elementary and middle schools, but also high schools that have within-school vaccine coverage <90%. Masks are supported as one of the simplest, yet effective, mitigation strategies.35,36,70 Masking was of particular importance for elementary and many middle school students who were ineligible for vaccination; we estimated that a typical 380-person elementary school and 420-person middle school could see 35 and 41 symptomatic cases, respectively, of COVID-19 over the four-month semester under a reopening plan that did not involve masking (or other NPIs) and where community vaccination coverage is 70%. Using masks, even those that are only 15-25% effective, reduced excess risk in our simulations to 13 cases per elementary school and 18 per middle school per semester. Inadequate mask use has been implicated in school-based transmission in the United States and elsewhere.29,30,70,71

Nevertheless, achieving lower risk tolerances, such as fewer than ten additional school-attributable infections per 1,000 school population, required adding additional layers of protection, e.g., reduced contact between students via cohorting. This suggests that schools may want to consider additional precautions above and beyond the minimum requirement of masks. For instance, schools that can implement a cohort approach, or provide regular testing, should consider doing so. We estimated that high school students were at lower risk of infection, assuming vaccination rates among students matched those of the surrounding community, but nevertheless may require both masking and weekly testing to achieve a transmission probability of <50% per school per month.

Uncertainty, represented here as the 89% HPDI across the 1,000 simulations, highlights that the potential for rare outbreaks may remain, even where average risk is low. In this respect, our findings are consistent with early reports from the fall 2021 semester in the Bay Area, where one school district experienced an outbreak affecting 50% of students in one classroom,29 even as neighboring San Francisco Unified school district reported zero outbreaks.72 Uncertainty was greatest among middle school and high school teachers and students, in part because pockets of low vaccine coverage within these environments can be sufficient to support occasional outbreaks. In our model, vaccine coverage was distributed randomly throughout the full population, such that some school realizations had vaccination coverage of teachers or students well below 50%, where transmission was possible. This represents reality, where certain school populations may have lower vaccination coverages than others.

Increased vaccine coverage of community members and teachers helped reduce illness among children who were not yet age-eligible for vaccination. We estimated that increasing vaccination coverage of the general population reduced the excess risk of transmission by 24% among elementary students. Similarly, we estimated that increasing vaccination coverage among teachers from 70% to 95% reduced the excess risk of school transmission by 37% among elementary students This suggests that teacher-to-student transmission is an important route of transmission that can be eliminated by increased vaccination. This finding agrees with conclusions from recent epidemiological investigations of school-associated outbreaks. In Georgia, investigation of 31 cases across six elementary school populations found that two outbreaks were initiated by teacher-to-teacher transmission, followed by teacher-to-student transmission, accounting for nearly 50% of the cases.30 Similarly, outbreaks at three child care facilities in Utah were linked to adult index cases,31 and a large, prospective study in England found that staff-to-staff transmission and staff-to-student transmission were responsible for initiating 50% and 23%, respectively, of 30 confirmed school outbreaks.19 At the same time, child-to-adult transmission is documented as well.30,31,73 While reduced frequency and severity of symptoms in children may correspond to lower infectivity, viral load in children has been found to be equal to that in adults after controlling for symptoms.74

This study has limitations. First, community contact rates measured in the survey may reflect underestimates of actual community contact rates, as vaccination prevalence has increased since February – April of 2021 and community contacts increased with vaccination prevalence (survey data). Thus, our estimates of excess cases attributable to school transmission may be slight underestimates. Nevertheless, our previous work has shown that the effect of community transmission is minimized when within-school precautions are implemented.15 Second, our transmission model does not capture all the precautions outlined in CDC guidance, including the effect of spacing desks three feet apart, or handwashing. We additionally do not consider the beneficial effects conferred via ventilation improvements, which is particularly salient in California, where, in a sample of classrooms with HVACs, 85% of were under-ventilated (<7.1 liters per person per second).75 Such precautions are difficult to model using a contact-based transmission model, and thus our estimates may overestimate risk if schools continue to emphasize such measures. Moreover, testing is an important component of the CDPH plan for return to in-person schooling. While we including testing as a potential NPI, we do not thoroughly investigate various testing routines that yield the optimal benefit, as does other work.76 We focus on modifiable conditions within the school environment, and thus do not consider interventions to reduce contact between schoolchildren outside the classroom, even as study suggests that the majority of transmission between children occurs outside the classroom.7 Our use of primary data collected from contact surveys improves upon other estimates of outside classroom contacts. Third, most of our model simulations assume a high vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic COVID-19. Vaccine effectiveness may change as novel variants emerge and circulate; however, early studies indicate that vaccine effectiveness against variants of concern—including Delta—generally remain high.77 Our model accounts for variation in differential vaccine effectiveness by disease endpoint, while not imposing assumptions on waning effectiveness over time or increases in effectiveness via booster shots. While this effect may be small over a single semester, it remains an important consideration for longer-term transmission dynamics. Fourth, our initial conditions for seroprevalence in the synthetic population encompassed published 2020 seroprevelance estimates for the Bay Area, so may represent an underestimate of the true seroprevalence in the community as of 2021. If so, our modelled estimates of excess cases may represent a slight overestimate. Finally, our modelling results are sensitive to assumptions about the values for certain parameters, such as relative susceptibility of children to SARS-CoV-2, for which there remains high uncertainty. As the Delta variant poses unseen challenges to school communities, we have limited empirical data to support our model results. However, our estimates of the school-attributable risk are consistent with that reported by other modelling studies,39,78 and qualitatively align with reports of increasing rates of infection and occasional outbreaks among children – particularly in parts of the country with low vaccination coverage, no mask mandates in schools, or lapses in mask use28,29,70—and reports of low transmission in districts with high levels of precautionary measures.72

Conclusion

Our findings support recommendations made by CDC and CDPH to fully reopen K-12 schools; encourage high levels of vaccine uptake among eligible students and staff; and maintain mask usage, particularly among unvaccinated (here, elementary) school populations or school populations with vaccine coverage <80%. Vaccination remains the most effective and sustainable means of risk reduction and efforts should focus on increasing vaccination coverage among the eligible community members and school population. Among populations not yet eligible for vaccination and communities with lower vaccination coverage, prevention measures, such as masking, may be needed to reduce the risk of school outbreaks. Schools may consider layering testing or cohorting as additional safety measures, particularly as the Delta variant takes hold.

Contributors

All authors conceptualized the study and its methodology. KLA collected and analyzed the survey data. JRH performed the modelling analysis and wrote the manuscript. KLA and JVR edited the manuscript. JVR supervised the research.

Data sharing statement

Data and code for this analysis can be found at https://github.com/jrhead/COVIDandVaccinatedSchools

Declaration of Competing Interest

None to declare.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Science Foundation grant no. 2032210, by National Institutes of Health grant nos. R01AI125842 and R01AI148336, and by the MIDAS Coordination Center (MIDASSUP2020-4) by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Science (3U24GM132013-02S2). The funding source played no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lana.2021.100133.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Levinson M, Cevik M, Lipsitch M. Reopening Primary Schools during the Pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2024920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshikawa H, Wuermli AJ, Britto PR, et al. Effects of the Global Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic on Early Childhood Development: Short- and Long-Term Risks and Mitigating Program and Policy Actions. The Journal of pediatrics. 2020;223:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armitage R, Nellums LB. Considering inequalities in the school closure response to COVID-19. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(5):e644. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30116-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Lancker W, Parolin Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: a social crisis in the making. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e243–e2e4. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaabane S, Doraiswamy S, Chaabna K, Mamtani R, Cheema S. The Impact of COVID-19 School Closure on Child and Adolescent Health: A Rapid Systematic Review. Children. 2021;8(5):415. doi: 10.3390/children8050415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):421. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naimark D, Mishra S, Barrett K, et al. Simulation-Based Estimation of SARS-CoV-2 Infections Associated With School Closures and Community-Based Nonpharmaceutical Interventions in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmerman KO, Akinboyo IC, Brookhart MA, et al. Incidence and secondary transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infections in schools. Pediatrics. 2021 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-048090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falk A, Benda A, Falk P, Steffen S, Wallace Z, Høeg TB. COVID-19 Cases and Transmission in 17 K–12 Schools—Wood County, Wisconsin, August 31–November 29, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021;70(4):136. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7004e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honein MA, Barrios LC, Brooks JT. Data and Policy to Guide Opening Schools Safely to Limit the Spread of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Jama. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrejko KL, Pry J, Myers JF, et al. Prevention of COVID-19 by mRNA-based vaccines within the general population of California. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab640. 2021.04.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haas EJ, Angulo FJ, McLaughlin JM, et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. The Lancet. 2021;397(10287):1819–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, et al. Interim estimates of vaccine effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among health care personnel, first responders, and other essential and frontline workers—eight US locations, December 2020–March 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021;70(13):495. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Head JR, Andrejko KL, Cheng Q, et al. School closures reduced social mixing of children during COVID-19 with implications for transmission risk and school reopening policies. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2021;18(177) doi: 10.1098/rsif.2020.0970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.USAFACTS Coronavirus Locations: COVID-19 Map by County and State. 2021 https://usafacts.org/visualizations/coronavirus-covid-19-spread-map (accessed July 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forbes H, Morton CE, Bacon S, et al. Association between living with children and outcomes from COVID-19: an OpenSAFELY cohort study of 12 million adults in England. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n628. 2020.11.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Domenico L, Pullano G, Sabbatini CE, Boëlle P-Y, Colizza V. Modelling safe protocols for reopening schools during the COVID-19 pandemic in France. Nature Communications. 2021;12(1):1073. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ismail SA, Saliba V, Lopez Bernal J, Ramsay ME, Ladhani SN. SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission in educational settings: a prospective, cross-sectional analysis of infection clusters and outbreaks in England. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30882-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COID Data Tracker: Variant Proportions. 2021 https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions (accessed July 12 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis D. What new COVID variants mean for schools is not yet clear. Nature. 2021 doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viner RM, Mytton OT, Bonell C, et al. Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Children and Adolescents Compared With Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson HA, Mousa A, Dighe A, et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Setting-specific Transmission Rates: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2021;73(3):e754–ee64. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies NG, Klepac P, Liu Y, et al. Age-dependent Effects in the Transmission and Control of COVID-19 Epidemics. Nature medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu Y, Bloxham CJ, Hulme KD, et al. A Meta-analysis on the Role of Children in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in Household Transmission Clusters. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(12):e1146–e1e53. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(6):1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clare S, David O, Rachel H, et al. Deaths in Children and Young People in England following SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first pandemic year: a national study using linked mandatory child death reporting data. Research Square. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cull B, Harris M. Children and COVID-10: State data report: American Academy of Pediatrics & Children's Hospital Association. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam-Hine T, McCurdy SA, Santora L, et al. Outbreak Associated with SARS-CoV-2 B. 1.617. 2 (Delta) Variant in an Elementary School—Marin County, California, May–June 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021;70(35):1214. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7035e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gold JA, Gettings JR, Kimball A, et al. Clusters of SARS-CoV-2 infection among elementary school educators and students in one school district—Georgia, December 2020–January 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021;70(8):289. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7008e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez AS, Hill M, Antezano J, et al. Transmission dynamics of COVID-19 outbreaks associated with child care facilities—Salt Lake City, Utah, April–July 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(37):1319. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buonsenso D, Munblit D, De Rose C, et al. Preliminary evidence on long COVID in children. Acta Paediatrica. 2021;110(7):2208–2211. doi: 10.1111/apa.15870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pouletty M, Borocco C, Ouldali N, et al. Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 mimicking Kawasaki disease (Kawa-COVID-19): a multicentre cohort. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2020;79(8):999–1006. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wise J. Long covid: One in seven children may still have symptoms 15 weeks after infection, data show. BMJ. 2021;374:n2157. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidance for COVID-19 Prevention in Kindergarten (K)-12 Schools. 2021 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/k-12-guidance.html (accessed July 9 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 36.California Department of Public Health COVID-19 Public Health Guidance for K-12 Schools in California, 2021-22 School Year. 2021 https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-19/K-12-Guidance-2021-22-School-Year.aspx (accessed July 13 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 37.San Francisco Chronicle Staff Timeline: How the Bay Area has combated the coronavirus. 2020. 2020 https://projects.sfchronicle.com/2020/coronavirus-timeline (accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burbio K-12 School Opening Tracker. 2021 https://cai.burbio.com/school-opening-tracker (accessed June 29 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giardina J, Bilinski A, Fitzpatrick MC, et al. When do elementary students need masks in school? Model-estimated risk of in-school SARS-CoV-2 transmission and related infections among household members before and after student vaccination. medRxiv. 2021 2021.08.04. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu CY, Berlin J, Kiti MC, et al. Rapid review of social contact patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001412. 2021.03.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Litvinova M, Liu Q-H, Kulikov ES, Ajelli M. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 116. 2019. Reactive school closure weakens the network of social interactions and reduces the spread of influenza; pp. 13174–13181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cauchemez S, Bhattarai A, Marchbanks TL, et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 108. 2011. Role of social networks in shaping disease transmission during a community outbreak of 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza; pp. 2825–2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Byambasuren O, Cardona M, Bell K, Clark J, McLaws M-L, Glasziou P. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: systematic review and meta-analysis. Official Journal of the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada. 2020;5(4):223–234. doi: 10.3138/jammi-2020-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vermund SH, Pitzer VE. Asymptomatic transmission and the infection fatality risk for COVID-19: Implications for school reopening. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.California Department of Public Health Tracking variants. 2021 https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-19/COVID-Variants.aspx (accessed August 1 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Deta variant: What we know about the science. 2021 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/delta-variant.html (accessed August 1 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diekmann O, Heesterbeek JA, Roberts MG. The construction of next-generation matrices for compartmental epidemic models. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7(47):873–885. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laxminarayan R, Wahl B, Dudala SR, et al. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in two Indian states. Science. 2020;370(6517):691–697. doi: 10.1126/science.abd7672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 Among Children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perkins TA, Paz-Soldan VA, Stoddard ST, et al. Proceedings Biological sciences. Vol. 283. 2016. Calling in sick: impacts of fever on intra-urban human mobility. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferguson NM, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilan G, et al. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11538-020-00726-x. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-NPI-modelling-16-03-2020.pdf (accessed March 25, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sah P, Vilches TN, Moghadas SM, et al. Accelerated vaccine rollout is imperative to mitigate highly transmissible COVID-19 variants. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He X, Lau EH, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nature medicine. 2020;26(5):672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li R, Pei S, Chen B, et al. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) Science. 2020:eabb3221. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moghadas SM, Fitzpatrick MC, Sah P, et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 117. 2020. The implications of silent transmission for the control of COVID-19 outbreaks; pp. 17513–17515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Integrated County View. 2021 https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#county-view (accessed August 1 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Routledge I, Epstein A, Takahashi S, et al. Citywide serosurveillance of the initial SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in San Francisco using electronic health records. Nature Communications. 2021;12(1):3566. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23651-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Higdon MM, Wahl B, Jones CB, et al. A systematic review of COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease. medRxiv. 2021 2021.09.17. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 Vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Self WH. Comparative effectiveness of Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, and Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) vaccines in preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations among adults without immunocompromising conditions—United States, March–August 2021. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2021;70 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7038e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eikenberry SE, Mancuso M, Iboi E, et al. To mask or not to mask: Modeling the potential for face mask use by the general public to curtail the COVID-19 pandemic. Infectious Disease Modelling. 2020;5:293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liang M, Gao L, Cheng C, et al. Efficacy of face mask in preventing respiratory virus transmission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel medicine and infectious disease. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van der Sande M, Teunis P, Sabel R. Professional and home-made face masks reduce exposure to respiratory infections among the general population. PloS one. 2008;3(7):e2618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uchida M, Kaneko M, Hidaka Y, et al. Effectiveness of vaccination and wearing masks on seasonal influenza in Matsumoto City, Japan, in the 2014/2015 season: An observational study among all elementary schoolchildren. Preventive medicine reports. 2017;5:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watson J, Whiting PF, Brush JE. Interpreting a covid-19 test result. Bmj. 2020;369:m1808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID Data Tracker: Vaccinations by County. 2021 https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations-county-view (accessed July 12 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 68.McElreath R. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2018. Statistical rethinking: A Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kruschke J. Doing Bayesian data analysis: A tutorial with R, JAGS, and Stan. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chernozhukov V, Kasahara H, Schrimpf P. The association of opening K–12 schools with the spread of COVID-19 in the United States: County-level panel data analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118(42) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2103420118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stein-Zamir C, Abramson N, Shoob H, et al. A large COVID-19 outbreak in a high school 10 days after schools’ reopening, Israel, May 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(29) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.29.2001352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith C. NBC Bay Area; 2021. San Francisco Unified Reports Zero COVID-19 Outbreaks, Case Transmissions. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meuris C, Kremer C, Geerinck A, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 After COVID-19 Screening and Mitigation Measures for Primary School Children Attending School in Liège, Belgium. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chung E, Chow EJ, Wilcox NC, et al. Comparison of Symptoms and RNA Levels in Children and Adults With SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Community Setting. JAMA Pediatrics. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pistochini T, Mande C, Modera M, et al. California Energy Commission; Sacramento, CA: 2020. Improving Ventilation and Indoor Environmental Quality in California K-12 Schools (CEC-500-2020-049) [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bilinski A, Ciaranello A, Fitzpatrick MC, et al. Asymptomatic COVID-19 screening tests to facilitate full-time school attendance: model-based analysis of cost and impact. medRxiv. 2021 2021.05.12. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sheikh A, McMenamin J, Taylor B, Robertson C. SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Scotland: demographics, risk of hospital admission, and vaccine effectiveness. The Lancet. 2021;397(10293):2461–2462. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01358-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]