Abstract

Background

Several available therapies for neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) have demonstrated efficacy in randomised controlled trials. However, translation of these results into improved care faces several challenges, as a direct comparison of the most pertinent therapies is incomplete.

Objectives

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of therapies for NETs, to guide clinical decision‐making, and to provide estimates of relative efficiency of the different treatment options (including placebo) and rank the treatments according to their efficiency based on a network meta‐analysis.

Search methods

We identified studies through systematic searches of the following bibliographic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE (Ovid); and Embase from January 1947 to December 2020. In addition, we checked trial registries for ongoing or unpublished eligible trials and manually searched for abstracts from scientific and clinical meetings.

Selection criteria

We evaluated randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing two or more therapies in people with NETs (primarily gastrointestinal and pancreatic).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies and extracted data to a pre‐designed data extraction form. Multi‐arm studies were included in the network meta‐analysis using the R‐package netmeta. We separately analysed two different outcomes (disease control and progression‐free survival) and two types of NET (gastrointestinal and pancreatic NET) in four network meta‐analyses. A frequentist approach was used to compare the efficacy of therapies.

Main results

We identified 55 studies in 90 records in the qualitative analysis, reporting 39 primary RCTs and 16 subgroup analyses. We included 22 RCTs, with 4299 participants, that reported disease control and/or progression‐free survival in the network meta‐analysis. Precision‐of‐treatment estimates and estimated heterogeneity were limited, although the risk of bias was predominantly low.

The network meta‐analysis of progression‐free survival found nine therapies for pancreatic NETs: everolimus (hazard ratio [HR], 0.36 [95% CI, 0.28 to 0.46]), interferon plus somatostatin analogue (HR, 0.34 [95% CI, 0.14 to 0.80]), everolimus plus somatostatin analogue (HR, 0.38 [95% CI, 0.26 to 0.57]), bevacizumab plus somatostatin analogue (HR, 0.36 [95% CI, 0.15 to 0.89]), interferon (HR, 0.41 [95% CI, 0.18 to 0.94]), sunitinib (HR, 0.42 [95% CI, 0.26 to 0.67]), everolimus plus bevacizumab plus somatostatin analogue (HR, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.28 to 0.83]), surufatinib (HR, 0.49 [95% CI, 0.32 to 0.76]), and somatostatin analogue (HR, 0.51 [95% CI, 0.34 to 0.77]); and six therapies for gastrointestinal NETs: 177‐Lu‐DOTATATE plus somatostatin analogue (HR, 0.07 [95% CI, 0.02 to 0.26]), everolimus plus somatostatin analogue (HR, 0.12 [95%CI, 0.03 to 0.54]), bevacizumab plus somatostatin analogue (HR, 0.18 [95% CI, 0.04 to 0.94]), interferon plus somatostatin analogue (HR, 0.23 [95% CI, 0.06 to 0.93]), surufatinib (HR, 0.33 [95%CI, 0.12 to 0.88]), and somatostatin analogue (HR, 0.34 [95% CI, 0.16 to 0.76]), with higher efficacy than placebo. Besides everolimus for pancreatic NETs, the results suggested an overall superiority of combination therapies, including somatostatin analogues.

The results indicate that NET therapies have a broad range of risk for adverse events and effects on quality of life, but these were reported inconsistently.

Evidence from this network meta‐analysis (and underlying RCTs) does not support any particular therapy (or combinations of therapies) with respect to patient‐centred outcomes (e.g. overall survival and quality of life).

Authors' conclusions

The findings from this study suggest that a range of efficient therapies with different safety profiles is available for people with NETs.

Plain language summary

Treatment options for neuroendocrine tumours

Review question

We reviewed the evidence on safety and efficacy of therapies for neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) in the gastrointestinal tract and the pancreas to provide a ranking of these treatment options.

Background

NETs are a varied group of rare cancers, which can occur anywhere in the body. However, most neuroendocrine tumours derive from the gastrointestinal tract or the pancreas. There are many types of NETs with different growth rates and symptoms. While some NETs produce excess hormones, others do not release hormones, or not enough to cause symptoms. The treatment options, as well as their combinations and sequencing, depend on the type of tumour, its location, aggressiveness, and whether it produces excess hormones.

Until now, no clear recommendations could be given about which NET therapies were the most effective and caused the fewest adverse events. We used statistical methods to compare all therapies with each other based on the available information.

Study characteristics

We included 22 randomised controlled trials (studies in which participants are randomly assigned to treatment groups), published before 11 December 2020, with a total of 4299 people. There were differences in tumour location (gastrointestinal and pancreatic), tumour type, sample size, treatments, and quality of the research between the studies.

Key results

This analysis suggests, in general, a superiority of combination therapies, including somatostatin‐like medications, in both gastrointestinal and pancreatic NETs. However, in pancreatic NETs, everolimus was the most effective therapy with the highest certainty of evidence compared to the other treatments. Furthermore, the results indicate that NET therapies have a broad range of risk for adverse events and effects on quality of life. Because disease is often advanced at presentation and treatment is often given with the intent to control and shrink disease, rather than be ultimately curative, treatment adverse events and quality of life are key considerations.

Quality of evidence

We rated the certainty of the evidence as high to low for the different therapies. An overall ranking of the treatments (and combinations) was not possible. In order to make an informed decision, advantages and disadvantages of each therapy, including its risks for adverse events and effects on quality of life, have to be balanced against each other. Evidence from this network meta‐analysis (and underlying RCTs) does not support any particular therapy (or combinations of therapies) with respect to patient‐centred outcomes (e.g. overall survival and quality of life).

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Neuroendocrine tumours (NETs), sometimes referred to as carcinoid tumours, are a heterogenous group of malignancies (cancers) that arise from cells of the endocrine (hormonal) and neurological systems. They have an estimated overall 20‐year limited‐duration prevalence (number of people alive on a certain day who were diagnosed with a NET within the previous 20‐year period) of 171,321 and a yearly age‐adjusted incidence of 6.98 cases per 100,000 according to the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18 registry (Dasari 2017). A population‐based study found a 6.4‐fold increase in incidence between 1973 and 2012 (Dasari 2017). NETs are more common at higher age, with an incidence among people 65 years or older of 25 per 100,000. About 61.0% of NETs derive from the gastrointestinal tract or the pancreas (Lawrence 2011), and accordingly these tumours are called gastroenteropancreatic NET (GEP‐NET). Other sites for primary NET include lungs, thyroid, ovaries, cervix, pituitary, and adrenal glands (Hallet 2015).

The relative frequency and annual incidence rate per 100,000 of GEP‐NETs differ site by site and, in some cases, change over time and are different between countries and continents (Fraenkel 2014). NETs of the rectum are the most common in east Asia and the USA, while small intestinal NETs are the most common in males, and appendiceal NETs the most common in females in the UK (Fraenkel 2012; Fraenkel 2014). Racial discrepancies have been found in the US SEER registry, with small intestinal NETs being found more often in African‐Americans than in the white population (DePalo 2019).

Most GEP‐NETs are sporadic, but approximately 5% arise in the context of cancer predisposition syndromes (Clift 2020). Neuroendocrine tumours, especially those of the pancreas (pNET), may be associated with familial syndromes. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1) is the most common familial syndrome associated with NET, while Von Hippel‐Lindau syndrome, neurofibromatosis type‐1 and tuberous sclerosis are rarer.

Depending on localisation and stage of the disease, they present with a broad clinical spectrum, from asymptomatic people with an incidental discovery on imaging to florid endocrinopathy. Up to 30% to 40% of GEP‐NETs may be secretory (i.e. 'functional'), releasing a variety of hormones and hormone‐like substances (Clift 2020). Serotonin‐secreting small bowel NETs may lead to cardiac valve fibrosis (carcinoid heart disease) as a consequence of hormone hyper‐secretion.

The diagnosis of GEP‐NETs is usually based on a histopathology that demonstrates neuroendocrine features, such as positive immunohistochemical staining for synaptophysin and chromogranin A. The grading of GEP‐NETs, on the other hand, is based on the mitotic index using Ki‐67 immunohistochemistry (which estimates how many cells are dividing within a tumour and how quickly it might grow). The World Health Organization (WHO) classification divides NETs according to their proliferative activity into grade 1 (Ki‐67 index ≤ 2%) and grade 2 (Ki‐67 index 3% to 20%). Based on their morphological characteristics, grade 3 tumours are subdivided into well differentiated NET and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas, both with Ki‐67 index > 20% (Klimstra 2019). The grading aids in the prognostication of survival: the five‐year survival rates of grade 1, 2 and 3 NETs are 96%, 73% and 28%, respectively (Ramage 2012).

Description of the intervention

Tumour growth, treatment and outcome vary considerably with the location of the primary lesions, as well as with their grade, extension, and stage (Lawrence 2011; Modlin 2008; Yao 2008 (2)). A broad spectrum of therapeutic options permits staged disease management with various treatment combinations and sequencing. This approach, however, requires a highly interdisciplinary and dynamic approach, which typically involves physicians of various specialties who work in concert to manage these often‐complex cases and select a treatment strategy from an array of available options.

Management strategies depend on primary tumour, locoregional and distant metastases, differentiation, tumour‐related symptoms, syndromes and presence of carcinoid heart disease. Depending on primary tumour size and site, NETs are treated surgically whenever feasible, as this is the only potentially curative treatment (Yao 2008 (2)). In metastatic, well differentiated NETs, somatostatin analogues (SSA), and interferon alpha (IFN) as a possible second‐line therapy, are a cornerstone in the palliative setting, as effective means of improving quality of life (QoL) and delaying disease progression (Cives 2014; Clift 2020). More recently, molecularly targeted drugs like the mTOR‐inhibitor everolimus, the multi‐targeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib, and the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibody bevacizumab have been introduced into the clinical setting following trials demonstrating efficacy in people with progressive NET (Kunz 2013; Pavel 2016; Yao 2017). The radiolabelled somatostatin receptor ligand lutetium‐177‐DOTATATE also recently demonstrated a benefit over treatment with somatostatin analogues alone in people with progressive NET (Strosberg 2017). Liver‐directed therapies further broaden the therapeutic landscape (Pavel 2016). In advanced grade 3 pNET and advanced symptomatic or progressive grade 1 or 2 pNET, systemic chemotherapy with streptozocin‐ or temozolomide‐based regimens is the first choice of treatment. In grade 3 NEC, platinum‐based chemotherapy is recommended as a first‐line therapy (Pavel 2016).

Why it is important to do this review

Several available therapies have demonstrated efficacy in terms of disease control and/or progression‐free survival in randomised controlled trials (RCTs). However, translation of these results into improved care faces several challenges, as several therapies were compared with placebo only and a direct comparison of the most pertinent therapies is incomplete (Kaderli 2019). In a previous systematic review and network meta‐analysis on pNETs and neuroendocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract (GI‐NETs), we found several monotherapies that were superior to placebo, including everolimus, interferon, and sunitinib in pNETs and somatostatin analogues in pNETs and GI‐NETs (Kaderli 2019). Furthermore, the results suggested a superiority of combination therapies, especially those including somatostatin analogues. On the other hand, NET therapies have a broad range of risk for adverse events and effects on QoL, which need to be considered while choosing the appropriate treatment. A systematic comparison of benefits and harms of all currently available therapeutic modalities will allow informed clinical decision‐making for clinicians, patients and policy makers.

Furthermore, there is ongoing research in the treatment of NETs. Surufatinib has demonstrated a higher progression‐free survival in GI‐NETs in the SANET‐ep trial (Xu 2020 (ep)) and in pNET in the SANET‐p trial (Xu 2020 (p)). New results for axitinib and somatostatin analogue are expected in GI‐NET (AXINET trial, NCT01744249), for everolimus and streptozocin plus fluorouracil in pNET (SEQTOR trial, NCT02246127), and for lutetium‐177 (177Lu)‐DOTATATE and everolimus both in GI‐NET and pNET (COMPETE trial, NCT03049189). It is, therefore, vital to provide a regularly updated systematic review and network meta‐analysis for clinical decision‐making based on the best available and most recent evidence.

Objectives

To evaluate the safety and efficiency of therapies for NETs, to guide clinical decision‐making, and to provide estimates of relative efficiency of the different treatment options (including placebo) and rank the treatments according to their efficiency based on a network meta‐analysis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including randomised controlled cross‐over trials.

If a post hoc subgroup analysis was available and reported disease control after 12 months and/or progression‐free survival for either pNET or GEP‐NET only, the subgroup analysis was used for the network meta‐analysis instead of the main study including more than one type of NETs.

Types of participants

People of any age with any type and any stage of GEP‐NETs.

Types of interventions

We included RCTs comparing at least two treatments of any kind (including usual care or placebo) in NETs, administered in any way.

Examples of treatments include the mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus (Yao 2016), the multi‐targeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib (Raymond 2011), the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibody bevacizumab (Yao 2017), the radiolabelled somatostatin analogue lutetium‐177 (177Lu)‐dotatate (Strosberg 2017), and new combinations of previously established therapies (Pavel 2011). Several therapies were compared only with placebo, while others were directly compared.

Every individual drug or drug combination, as well as placebo, represent individual nodes in the network meta‐analysis. Due to the low number of included studies, we grouped together all different somatostatin analogues, as well as all different intervention doses, modalities, and administration frequencies.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Disease control after 12 months

Progression‐free survival

Secondary outcomes

Overall survival

Occurrence of adverse events according to the treatment applied (grades 3 to 4, any grade)

Quality of life (QoL)

Disease control is defined as the sum of complete response, partial response and stable disease, or as the total minus the number disease progressions. Progression‐free survival is the length of time during and after the treatment, that a patient lives with the disease, but it does not grow. We used unblinded, investigator‐assessed progression‐free survival outcomes. Adverse events were classified according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI 2010): Grade 1 corresponds to mild, grade 2 to moderate, grade 3 to severe or medically significant, and grade 4 to life‐threatening adverse events. Effects on QoL were quantified based on the QoL Questionnaire C30 of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ‐30) (Aaronson 1993).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials through systematic searches of the following bibliographic databases on 11 December 2020:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 12) in the Cochrane Library;

MEDLINE via Ovid (January 1947 to 11 December 2020);

Embase.com (January 1947 to 11 December 2020).

In addition, we checked trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal [apps.who.int/trialsearch/]) for ongoing or unpublished eligible trials and manually searched for abstracts from scientific and clinical meetings related to NETs in 2019 and 2020 (annual ENETS conference and neuroendocrine tumour symposium of the NANETS).

We searched all databases from 1 January 1947, until present, and imposed no restriction on language of publication (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3).

Searching other resources

We scanned the reference lists of the included RCT reports and relevant review articles for additional references.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

With two review authors working in duplicate, we independently screened all abstracts and obtained the full‐text report of potentially relevant studies. Subsequently, we screened all potentially relevant studies in the same way. Any discordance was resolved by a third review author.

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data which has been piloted in our previous systematic review and network meta‐analysis on therapeutic options for neuroendocrine tumours (Kaderli 2019). One of the review authors extracted study characteristics from included studies, and a second review author verified the extractions. We extracted the following study characteristics.

Characteristics of included trials: first author, year of publication, study origin, type of treatments, median duration and median follow‐up of each treatment, percentage of people with complete follow‐up, availability of a sample size calculation, and number of participants randomised for each treatment.

Participant data: separately for each treatment: primary tumour site, tumour grading, presence of metastases and functional tumours, percentage of female participants and the participants' median/mean age; main primary tumour (pNET and/or GI‐NET) for all treatments.

Clinical outcomes: complete response, partial response, stable disease, disease control, disease progression, investigator‐assessed progression‐free survival, median overall survival, occurrence of adverse events (grade 3 to 4, any grade), and QoL.

Any discordance was resolved by a third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked by a second review author for accuracy.

Due to the well‐defined patient characteristics, we did not expect significant effect modifiers and, due to the low number of included studies, we could not systematically analyse effect modifiers.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each RCT, using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011), which utilises the following domains.

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Completeness of outcome data

Selectivity of reporting

Other bias (including baseline imbalance, protocol deviations, inappropriate influence of funders)

We provided a summary risk of bias assessment for each study using the method outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Each domain was rated as low (bias is unlikely to seriously alter the results), high (bias is likely to seriously weaken confidence in results), or unclear risk of bias. All discordance was resolved by a third review author.

Measures of treatment effect

We used odds ratios as effect measures for disease control after 12 months and hazard ratios as effect measures for progression‐free survival, both accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). We applied a continuity correction for studies with a zero cell count by adding 0.5 to all cell frequencies. We summarised all results using forest plots with combined effect estimates and size of squares proportional to the inverse of the standard errors. Due to the low number of included studies and the heterogeneity of secondary outcomes, we presented these outcomes for each intervention (if available) using descriptive statistics — i.e. number and percentage of adverse events, and mean and standard deviation of the change of QoL.

We ranked treatments based on P scores, measuring the extent of certainty that a treatment is better than another one, averaged over all competing treatments (Rücker 2015).

Unit of analysis issues

The analysis was made at the individual allocation level.

Multi‐arm trials were included in the network meta‐analysis. The correlation of treatment effects on different comparisons was accounted for by re‐weighting all comparisons of each multi‐arm study (Rücker 2012; Rücker 2014).

We included cross‐over trials in the qualitative analysis. However, they were excluded from the network meta‐analysis due to the inappropriateness of the study design: including only the first intervention period of a cross‐over trial discards more than half of the information in the study.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors of included RCT reports for information on unreported outcomes and missing outcome data in their studies.

If a RCT report did not report hazard ratios and further data could not be obtained by contacting authors, we estimated the hazard ratios from reconstructed Kaplan‐Meier curves (if available) by using a Cox proportional hazard model.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using all pairwise comparisons available from more than one trial. We calculated the between‐study variance Ƭ2, the within‐design component of Cochran's Q (i.e. the weighted sum of squared differences between pairwise comparisons from multiple trials) and the associated I2 (percentage of variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance). If quantification of heterogeneity was not possible (i.e. if there was no comparison done in more than one trial), we fitted fixed‐effect models; otherwise, we used random‐effects models.

We assessed homogeneity and transitivity based on the distribution of neuroendocrine tumour types, and the differences in doses and application route, especially for somatostatin analogues.

We assessed inconsistency using closed loops within the network (if any) and calculated the between‐design component of Cochran's Q and the associated I2. In addition, we performed a netsplit analysis and compared direct and indirect estimates via a ratio of odds or hazard ratios.

We calculated the total Cochran's Q as the sum of between‐ and within‐designs component and the associated I2.

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess the risk for reporting bias, we first searched for a protocol for each of the included studies. For this, we went through the reference lists of corresponding published articles. If there was no reference to a protocol, we searched PubMed, Embase, and the internet for a protocol. If a protocol was available, we compared the mentioned outcomes and planned statistical analyses in the protocol with those in the published report. If no protocol was available, we used information from a corresponding registry entry of the included study to compare planned outcomes and analyses with those in the published report. If neither a protocol, nor a registry entry was available, we compared the outcomes and described analyses in the methods section of the published report with those reported in the results section. Any unexplained differences between the protocol, registry entry, or methods section and the reported results provided evidence for an increased risk of reporting bias of an included study.

If there were 10 or more included studies for individual pairwise meta‐analyses, we created funnel plots for visual inspection to detect potential asymmetry.

Data synthesis

We separately analysed two different outcomes (disease control and progression‐free survival) and two types of NET (pNET and GI‐NET) in four network meta‐analyses. The NET types were distinguished to ensure that the selected studies were similar except for the interventions being compared. If a study included several NET types, we included the respective subgroup analyses (if available): for pNET, one subgroup analysis was included for the analysis of progression‐free survival (Phan 2015 (2) instead of Caplin 2014) and, for GI‐NET, one subgroup analysis was included for the analysis of disease control and progression‐free survival (Castellano 2013 instead of Pavel 2011) and two subgroup analyses were included for the analysis of progression‐free survival (Dasari 2015 instead of Caplin 2014 and Singh 2018 (1) instead of Yao 2016). Otherwise, we relied on expert opinion whether or not to include the study and used sensitivity analyses to assess the effect of the decision.

Before including an intervention in the network meta‐analysis, we assessed the respective study populations critically in terms of the transitivity assumption. Interventions only given to a subset of participants (i.e. those critically ill) were not included in a sensitivity analysis. However, since the network is currently very sparse, the benefit of additional studies might outweigh a certain risk of violation of the transitivity assumption. The comparison among all interventions (including placebo) were of interest and we would not define a decision and a supplementary set. However, if more data become available, we might focus on a specific set of interventions.

Because the network is sparse, we merged similar interventions, i.e. different doses, administration intervals and routes of application of the same compound. When more data become available, we will consider splitting nodes if the effects are suspected to be different.

We performed the network meta‐analyses with a frequentist approach using R‐package (R Core 2019) netmeta (Rücker 2021). If quantification of heterogeneity was possible, i.e. if there were pairwise comparisons included in more than one trial, we used random‐effects models. Otherwise, we used fixed‐effect models. Validity of the network in terms of consistency was assessed quantitatively by comparing direct and indirect estimates for each loop of the network and qualitatively using GRADE (as described in section Assessment of heterogeneity).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In view of the small number of RCTs included in this review, we refrained from any subgroup analysis, including subgroup analysis based on tumour grading, since the separate analysis for each treatment included in a RCT was frequently missing.

If there was evidence for heterogeneity, we assessed participant and trial characteristics for a potential source of the heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

Currently, the network is very sparse and we were not able to undertake sensitivity analyses. If sufficient trials would have been identified, we would have considered several sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes. We would, for example, only use low risk of bias trials (trials without a high risk for selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting or other biases), exclude trials with a mixture of different types of NETs and use alternative or no merging of nodes. We would have also considered different analytical approaches, such as fixed‐effect only, or a Bayesian instead of the specified frequentist approach (e.g. using R package BUGSnet (Béliveau 2019)).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach to assess confidence in estimates of effect (certainty of evidence) associated with specific comparisons, including estimates from direct, indirect, and final network meta‐analysis (Brignardello‐Petersen 2018; Puhan 2014; Salanti 2014). Our confidence assessment addressed risk of bias (limitations in study design and execution), inconsistency (heterogeneity of estimates of effects across trials), indirectness (differences in population, interventions, or outcomes to the target of the network meta‐analysis) and imprecision (e.g. wide 95% confidence intervals including or close to the null effect). Limitations in any of these domains resulted in a decrease of the certainty of evidence from high to moderate, low, or very low‐certainty by ‐1 (serious concern) or ‐2 (very serious concern). We based indirect evidence on the most dominant loops (i.e. the shortest path between two treatments) and potentially rated it down for intransitivity (differences in study characteristics that may modify treatment effect in the direct comparisons along the path). We obtained the final network meta‐analysis confidence rating from the higher of the direct and indirect rating excluding imprecision and we rated it down for imprecision and incoherence (difference between direct and indirect estimates).

All studies and study arms used for the network meta‐analyses had included adult people with advanced GEP‐NET that were in need of and eligible for systematic therapies, supporting the transitivity assumption of the network meta‐analyses.

In the summary of findings tables, we included estimates of effects, ranking and certainty of evidence for different treatment options compared with placebo for disease control and progression‐free survival in pNET and GI‐NET.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

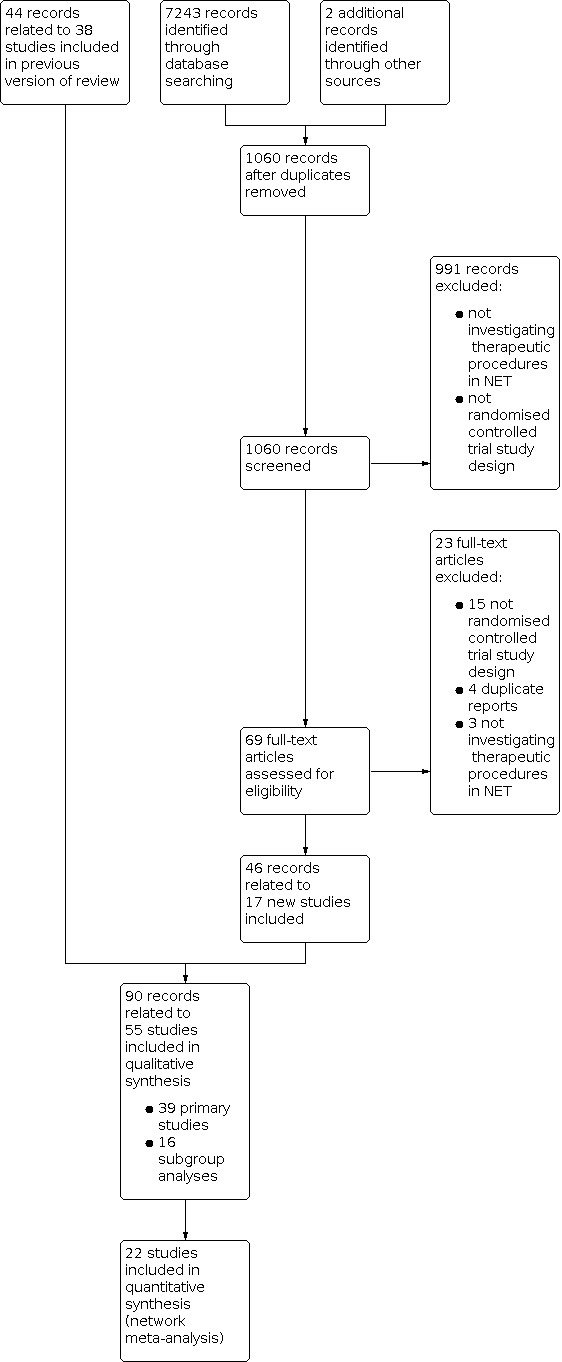

In our previous systematic review and network meta‐analysis on pNETs and GI‐NETs with the same search methods, we included 38 studies in the qualitative synthesis (30 primary studies and 8 subgroup analyses) (Kaderli 2019). The previously published searches on 27 November 2015 and 2 March 2018 led to the identification of 7243 records (Kaderli 2019). Following de‐duplication across the databases, the combined total yield of the updated search on 11 December 2020 was 1058 records:

CENTRAL: 255 records

MEDLINE (Ovid): 546 records

Embase: 257 records

Two additional records were added through scanning the reference lists of included RCT reports. After reading the abstracts, we excluded 991 records because they did not match the inclusion criteria. After assessing the full text, we excluded 23 records. In all, we included 55 studies in the qualitative analysis (39 primary RCTs and 16 subgroup analyses). A total of 22 studies reported disease control and/or progression‐free survival and were included in the network meta‐analyses (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 55 studies in 90 records in the qualitative analysis, reporting 39 primary RCTs (Arnold 2005; Bergsland 2020; Caplin 2014; Elf 2018; Faiss 2003; Jacobsen 1995; Kölby 2003; Kulke 2016; Kulke 2017 (1); Kulke 2017 (2); Lange 1992; Lepage 2020; Liu 2020; Maire 2012; Meyer 2014; Moertel 1980; Moertel 1992; O'Toole 2000; Öberg 1989; Pavel 2011; Pavel 2018 (1); Pavlakis 2020; Raymond 2011 (1); Rinke 2009; Sakata 2006; Salazar 2018; Saslow 1998; Soulen 2020; Strosberg 2017; Van Der Zwan 2018; Vinik 2016; Wolin 2015; Xu 2020 (ep); Xu 2020 (p); Yao 2008 (1); Yao 2011; Yao 2016; Yao 2017; Zhang 2020) and 16 subgroup analyses (Anthony 2012; Castellano 2013; Dasari 2015; Di Gialleonardo 2020; Fisher 2016; Ito 2012; Lombard‐Bohas 2015; Phan 2015 (1); Phan 2015 (2); Pusceddu 2018; Raymond 2011 (2); Singh 2018 (1); Strosberg 2011; Strosberg 2020; Wolin 2016; Yao 2019) (see Characteristics of included studies for details. Overall, 4654 patients were recruited and 26 different therapies were evaluated, including biotherapies, chemotherapies, targeted drugs, locoregional therapies, surgical treatment, and targeted radiopeptide therapy.

A total of 22 RCTs, which included 4299 patients, reported disease control and/or progression‐free survival and were included in the network meta‐analysis (Arnold 2005; Caplin 2014; Castellano 2013; Dasari 2015; Faiss 2003; Kölby 2003; Kulke 2016; Kulke 2017 (1); Öberg 1989; Pavel 2011; Phan 2015 (2); Raymond 2011 (1); Rinke 2009; Salazar 2018; Singh 2018 (1); Strosberg 2017; Xu 2020 (ep); Xu 2020 (p); Yao 2008 (1); Yao 2011; Yao 2016; Yao 2017).

Eighteen of 22 RCTs included in the network meta‐analysis were industry‐sponsored (Arnold 2005; Caplin 2014; Castellano 2013; Dasari 2015; Faiss 2003; Kulke 2017 (1); Pavel 2011; Phan 2015 (2); Raymond 2011 (1); Rinke 2009; Salazar 2018; Singh 2018 (1); Strosberg 2017; Xu 2020 (ep); Xu 2020 (p); Yao 2008 (1); Yao 2011; Yao 2016).

Excluded studies

During the first phase of record selection, we screened and excluded 991 records, which were not investigating therapeutic procedures in NET or did not fulfil the criteria of an RCT. Twenty‐three of the remaining 69 records were excluded after assessing the full‐text articles. They did not fulfil the criteria of an RCT, were duplicate reports or were not investigating therapeutic procedures in NET (see Characteristics of excluded studies for details).

Risk of bias in included studies

Summaries of the risk of bias for each domain and as percentages across all studies are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

3.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Twenty‐nine studies described a random component in the sequence generation process and were at low risk of selection bias. The other 26 studies had a randomised controlled trial study design; but in 25 studies there was no further report on the sequence generation process and in one study the randomisation was performed by the study drug supplier (Jacobsen 1995). For these studies, we judged the risk of selection bias as unclear.

Allocation concealment

Twenty‐five studies reported on the method to conceal allocation and were at low risk of selection bias. Twenty‐eight studies provided no further information addressing allocation concealment and were considered to be at unclear risk of selection bias. Two studies without information on allocation concealment and identical numbers of people in all treatment groups were considered to be at unclear risk of selection bias (Kulke 2017 (2); Yao 2008 (1)).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Twenty‐nine studies were double‐blinded and were at low risk of performance bias. Six studies (Kulke 2017 (1); Pavlakis 2020; Strosberg 2017; Strosberg 2020; Yao 2017; Zhang 2020) were designed as open‐label studies and in 14 studies participants and/or personnel were not blinded. They were considered to be at high risk of performance bias. Six studies provided no information and were at unclear risk of performance bias.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

Eighteen studies reported blinding of outcome assessors and were at low risk of detection bias. Of the remaining studies, 29 studies were at unclear risk of detection bias due to missing information on the blinding of outcome assessment and eight studies were at high risk of detection bias due to a lack of evidence for a blinding of the outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data

Thirty‐five studies were at low risk and 16 studies were at unclear risk of attrition bias due to missing information. In three studies, a significant number of people were excluded after randomisation (Moertel 1992; O'Toole 2000; Zhang 2020) and in one study (Öberg 1989) a group cross‐over was performed without additional information, whether intention‐to‐treat or analysis per‐protocol was performed. These four studies were considered to be at high risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

Thirty‐two studies published a study protocol or reported all results of the endpoints stated in the methods section and were at low risk of reporting bias. Sixteen studies provided little information on primary or secondary endpoints and their definition and were judged to be at low or unclear risk for reporting bias, depending on a study‐level judgement. In seven studies, not all stated endpoints were reported (Meyer 2014; Moertel 1980; Singh 2018 (1); Strosberg 2017; Strosberg 2020; Yao 2016; Yao 2019). Hence, we judged the risk of reporting bias for these studies as high.

Other potential sources of bias

Two studies were at high risk for other potential sources of bias due to the use of investigator‐dependent measurement methods (Moertel 1980; Moertel 1992).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings 1. Estimates of effects, ranking, and certainty of evidence for different treatment options compared with placebo for disease control in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNET).

|

Total studies: 9 Total participants: 1757 |

Included trials | Median follow‐up (months)1 | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects2 | Certainty of evidence3 | P‐score4 | |

| Disease control with intervention | Disease control without intervention | ||||||

|

Everolimus (3 RCTs; 632 participants) |

Kulke 2017 (1); Salazar 2018; Yao 2011 | 17 |

OR 3.29 (2.21 to 4.90) |

80% | 55% | Moderate* | 0.83 |

|

Everolimus + SSA (2 RCTs; 589 participants) |

Kulke 2017 (1); Pavel 2011 | not reported |

OR 2.89 (1.61 to 5.19) |

84% | 65% | Moderate‡ | 0.73 |

|

Interferon + SSA (2 RCTs; 171 participants) |

Arnold 2005; Faiss 2003 | not reported |

OR 2.88 (1.16 to 7.13) |

27% | 11% | Very low*,‡,¶ | 0.71 |

|

Interferon (1 RCT; 66 participants) |

Faiss 2003 | not reported |

OR 2.58 (0.75 to 8.81) |

35% | 17% | Very low**,‡,§§ | 0.63 |

|

SSA (4 RCTs, 804 participants) |

Arnold 2005; Caplin 2014; Faiss 2003; Pavel 2011 | not reported |

OR 2.36 (1.43 to 3.88) |

67% | 47% | Moderate‡ | 0.56 |

|

Surufatinib (1 RCT; 172 participants) |

Xu 2020 (p) | 19 |

OR 1.99 (1.02 to 3.88) |

74% | 59% | High | 0.48 |

|

Sunitinib (1 RCT; 171 participants) |

Raymond 2011 (1) | 60 |

OR 1.72 (0.91 to 3.27) |

72% | 60% | Low*,§ | 0.39 |

|

Placebo (4 RCTs; 957 participants) |

Caplin 2014; Raymond 2011 (1); Xu 2020 (p); Yao 2011 | 27 | Reference comparator | 53% | ‐ | Reference | 0.12 |

|

Dactolisib (1 RCT; 62 participants) |

Salazar 2018 | not reported |

OR 0.56 (0.13 to 2.37) |

61% | 74% | Very low*,§§ | 0.06 |

Population: Patients with pNET

Interventions: Everolimus, everolimus + SSA, interferon + SSA, interferon, SSA, surufatinib, sunitinib, dactolisib

Comparator (reference): Placebo

Outcome: Disease control after 12 months

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SSA, somatostatin analogues

1Weighted average of trials reporting the median follow‐up time

2Absolute effects with the intervention were calculated as weighted average over all treatment arms with the intervention. Absolute effects without the intervention were derived using the odds ratio from the network meta‐analysis.

3Using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach

Downgraded for *risk of bias, †inconsistency, ‡indirectness, §imprecision, ¶intransitivity or #incoherence. Severe limitations are indicated by two symbols.

4The P‐score measures the probability that a treatment is better than another treatment, averaged over all competing treatments.

Summary of findings 2. Estimates of effects, ranking, and certainty of evidence for different treatment options compared with placebo for progression‐free survival in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNET).

|

Total studies: 10 Total participants: 2113 |

Included trials | Median follow‐up (months)1 | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effect2 | Certainty of evidence3 | P‐score4 | |

| Median PFS with intervention (months) | Median PFS without intervention (months) | ||||||

|

Everolimus (3 RCT; 632 participants) |

Kulke 2017 (1); Salazar 2018; Yao 2011 | 17 |

HR 0.36 (0.28 to 0.46) |

12 | 4 | Moderate* | 0.75 |

|

Interferon + SSA (2 RCTs; 468 participants) |

Faiss 2003; Yao 2017 | not reported |

HR 0.34 (0.14 to 0.80) |

15 | 5 | Very low**,‡ | 0.74 |

|

Everolimus + SSA (3 RCTs; 739 participants) |

Kulke 2016; Kulke 2017 (1); Pavel 2011 | not reported |

HR 0.38 (0.26 to 0.57) |

16 | 6 | Low‡ | 0.68 |

|

Bevacizumab + SSA (1 RCT; 402 participants) |

Yao 2017 | not reported |

HR 0.36 (0.15 to 0.89) |

17 | 6 | Very low**,‡,¶ | 0.65 |

|

Interferon (1 RCT; 66 participants) |

Faiss 2003 | not reported |

HR 0.41 (0.18 to 0.94) |

not reported | ‐ | Very low**,‡ | 0.58 |

|

Sunitinib (1 RCT; 171 participants) |

Raymond 2011 (1) | 60 |

HR 0.42 (0.26 to 0.67) |

11 | 5 | Moderate* | 0.56 |

|

Everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA (1 RCT; 150 participants) |

Kulke 2016 | not reported |

HR 0.48 (0.28 to 0.83) |

17 | 8 | Very low**,¶ | 0.42 |

|

Surufatinib (1 RCT; 172 participants) |

Xu 2020 (p) | 19 |

HR 0.49 (0.32 to 0.76) |

11 | 5 | High | 0.41 |

|

Dactolisib (1 RCT; 62 participants) |

Salazar 2018 | not reported |

HR 0.55 (0.25 to 1.21) |

8 | 4 | Low*,§ | 0.35 |

|

SSA (3 RCTs; 586 participants) |

Faiss 2003; Pavel 2011; Phan 2015 (2) | not reported |

HR 0.51 (0.34 to 0.77) |

11 | 6 | Moderate | 0.33 |

|

Placebo (4 RCTs; 844 participants) |

Phan 2015 (2); Raymond 2011 (1); Xu 2020 (p); Yao 2011 | 27 | Reference comparator | 6 | ‐ | Reference | 0.01 |

Population: Patients with pNET

Interventions: Bevacizumab + SSA, dactolisib, everolimus, everolimus + SSA, everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA, interferon, interferon + SSA, sunitinib, surufatinib, SSA

Comparator (reference): Placebo

Outcome: Progression‐free survival

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio; PFS, progression‐free survival; CI, confidence interval; SSA, somatostatin analogues.

1Weighted average of trials reporting the median follow‐up time

2Absolute effects with the intervention were calculated as weighted average over all treatment arms with the intervention. Absolute effects without the intervention were derived using the hazard ratio from the network meta‐analysis assuming an exponential distribution.

3Using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach

Downgraded for *risk of bias, †inconsistency, ‡indirectness, §imprecision, ¶intransitivity or #incoherence. Severe limitations are indicated by two symbols.

4The P‐score measures the probability that a treatment is better than another treatment, averaged over all competing treatments.

Summary of findings 3. Estimates of effects, ranking, and certainty of evidence for different treatment options compared with placebo for disease control in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours (GI‐NET).

|

Total studies: 11 Total participants: 1338 |

Included trials | Median follow‐up (months)1 | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects2 | Certainty of evidence3 | P‐score4 | |

| Disease control with intervention | Disease control without intervention | ||||||

|

Bevacizumab + SSA (1 RCT; 44 participants) |

Yao 2008 (1) | not reported |

OR 45.0 (3.32 to 609) |

95% | 32% | Very low*,††,‡,¶¶,§ | 0.91 |

|

177‐Lu‐DOTATATE + SSA (1 RCT; 229 participants) |

Strosberg 2017 | 14 |

OR 30.4 (8.19 to 113) |

80% | 12% | Very low**,¶,§ | 0.90 |

|

Everolimus + SSA (1 RCT; 39 participants) |

Castellano 2013 | not reported |

OR 15.1 (2.55 to 88.9) |

63% | 10% | Very low‡,¶,§ | 0.78 |

|

Interferon + SSA (4 RCTs; 283 participants) |

Arnold 2005; Faiss 2003; Kölby 2003; Yao 2008 (1) | 76 |

OR 5.71 (1.90 to 17.2) |

48% | 14% | Very low*,††,‡,¶ | 0.60 |

|

Interferon (2 RCTs; 86 participants) |

Faiss 2003; Öberg 1989 | 7 |

OR 4.03 (0.86 to 18.8) |

55% | 23% | Very low**,‡,¶,§§ | 0.48 |

|

Surufatinib (1 RCT; 198 participants) |

Xu 2020 (ep) | 14 |

OR 3.50 (1.21 to 10.1) |

84% | 61% | Moderate‡ | 0.45 |

|

SSA (7 RCTs; 796 participants) |

Arnold 2005; Caplin 2014; Castellano 2013; Faiss 2003; Kölby 2003; Rinke 2009; Strosberg 2017 | 87 |

OR 2.93 (1.36 to 6.32) |

43% | 21% | Moderate‡ | 0.37 |

|

Everolimus (1 RCT; 302 participants) |

Yao 2016 | 21 |

OR 2.53 (0.95 to 6.79) |

82% | 65% | Very low*,‡,§ | 0.35 |

|

Placebo (4 RCT; 789 participants) |

Caplin 2014; Rinke 2009; Xu 2020 (ep); Yao 2016 | 35 | Reference comparator | 53% | ‐ | Reference | 0.11 |

|

Streptozocin + 5‐FU (1 RCT; 20 participants) |

Öberg 1989 | 12 |

OR 0.13 (0.00 to 4.58) |

40% | 83% | Very low**,‡,¶,§§ | 0.04 |

Population: Patients with GI‐NET

Interventions: 177‐Lu‐DOTATATE + SSA, bevacizumab + SSA, everolimus, everolimus + SSA, interferon, interferon + SSA, SSA, streptozocin + 5‐FU, surufatinib

Comparator (reference): Placebo

Outcome: Disease control after 12 months

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SSA, somatostatin analogues

1Weighted average of trials reporting the median follow‐up time

2Absolute effects with the intervention were calculated as weighted average over all treatment arms with the intervention. Absolute effects without the intervention were derived using the odds ratio from the network meta‐analysis.

3Using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach

Downgraded for *risk of bias, †inconsistency, ‡indirectness, §imprecision, ¶intransitivity or #incoherence. Severe limitations are indicated by two symbols.

4The P‐score measures the probability that a treatment is better than another treatment, averaged over all competing treatments.

Summary of findings 4. Estimates of effects, ranking, and certainty of evidence for different treatment options compared with placebo for progression‐free survival in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours (GI‐NET).

|

Total studies: 9 Total participants: 1311 |

Included trials | Median follow‐up (months)1 | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effect2 | Certainty of evidence3 | P‐score4 | |

| Median PFS with intervention (months) | Median PFS without intervention (months) | ||||||

|

177‐Lu‐DOTATATE + SSA (1 RCT; 229 participants) |

Strosberg 2017 | 14 |

HR 0.07 (0.02 to 0.26) |

not reported | ‐ | Very low**,¶,§ | 0.93 |

|

Everolimus + SSA (1 RCT; 39 participants) |

Castellano 2013 | not reported |

HR 0.12 (0.03 to 0.54) |

30 | 3 | Very low‡,¶,§ | 0.79 |

|

Bevacizumab + SSA (2 RCTs; 446 participants) |

Yao 2008 (1); Yao 2017 | not reported |

HR 0.18 (0.04 to 0.94) |

16 | 3 | Very low**,‡,¶¶,§ | 0.66 |

|

Interferon + SSA (3 RCTs; 512 participants) |

Faiss 2003; Yao 2008 (1); Yao 2017 | not reported |

HR 0.23 (0.06 to 0.93) |

15 | 3 | Very low**,‡,¶,§ | 0.56 |

|

Interferon (1 RCT; 66 participants) |

Faiss 2003 | not reported |

HR 0.27 (0.07 to 1.10) |

not reported | ‐ | Very low**,‡,¶,§§ | 0.49 |

|

Surufatinib (1 RCT; 198 participants) |

Xu 2020 (ep) | 14 |

HR 0.33 (0.12 to 0.88) |

9 | 3 | Moderate‡ | 0.43 |

|

SSA (5 RCTs; 492 participants) |

Castellano 2013; Dasari 2015; Faiss 2003; Rinke 2009; Strosberg 2017 | 96 |

HR 0.34 (0.16 to 0.76) |

10 | 3 | High | 0.39 |

|

Everolimus (1 RCT; 175 participants) |

Singh 2018 (1) | 21 |

HR 0.56 (0.21 to 1.49) |

13 | 7 | Low*,§ | 0.23 |

|

Placebo (4 RCTs; 531 participants) |

Dasari 2015; Rinke 2009; Singh 2018 (1); Xu 2020 (ep) | 38 | Reference comparator | 8 | ‐ | Reference | 0.03 |

Population: Patients with GI‐NET

Interventions: 177‐Lu‐DOTATATE + SSA, bevacizumab + SSA, everolimus, everolimus + SSA, interferon, interferon + SSA, SSA, surufatinib

Comparator (reference): Placebo

Outcome: Progression‐free survival

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; SSA, somatostatin analogues

1Weighted average of trials reporting the median follow‐up time

2Absolute effects with the intervention were calculated as weighted average over all treatment arms with the intervention. Absolute effects without the intervention were derived using the hazard ratio from the network meta‐analysis assuming an exponential distribution.

3Using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach

Downgraded for *risk of bias, †inconsistency, ‡indirectness, §imprecision, ¶intransitivity or #incoherence. Severe limitations are indicated by two symbols.

4The P‐score measures the probability that a treatment is better than another treatment, averaged over all competing treatments.

Treatment efficacy in pNETs

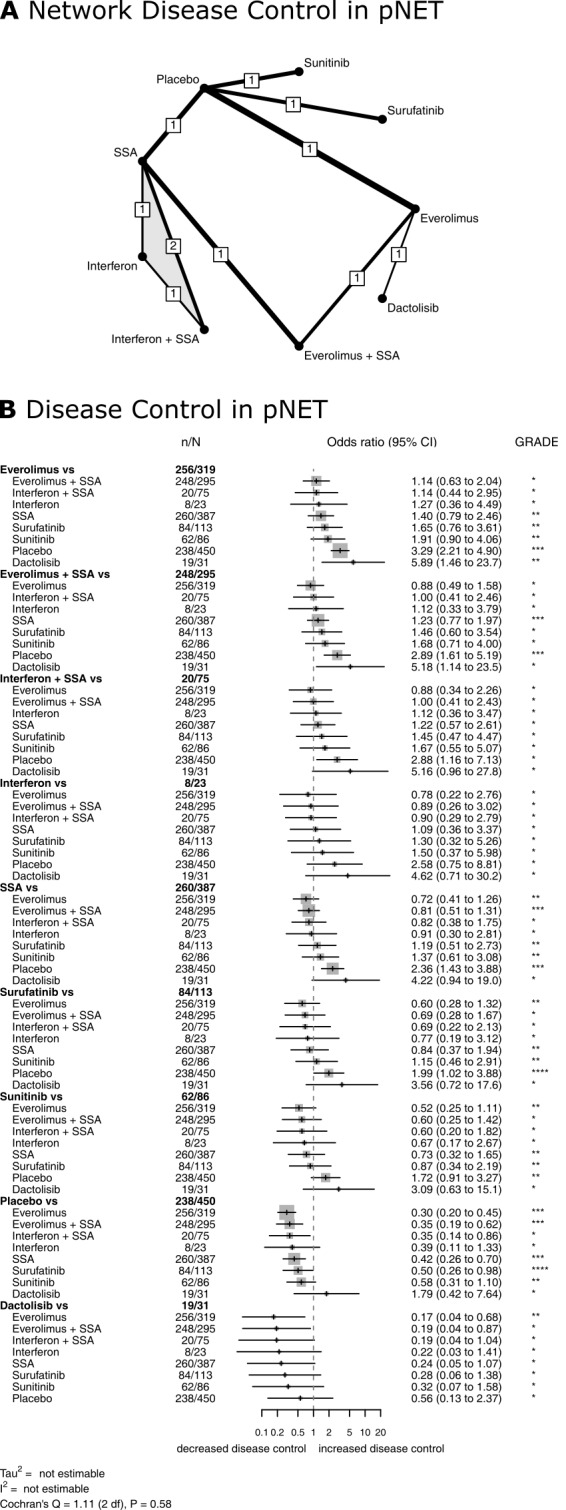

Nine RCTs (Arnold 2005; Caplin 2014; Faiss 2003; Kulke 2017 (1); Pavel 2011; Raymond 2011 (1); Salazar 2018; Xu 2020 (p); Yao 2011) compared disease control rates for nine different therapies in pNETs (Figure 4). The network meta‐analysis found that single therapy with everolimus and combination therapies with a somatostatin analogue were highly effective. Specifically, everolimus (P score, 0.83), everolimus plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.73), and interferon plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.71) achieved the highest disease control rates, followed by single treatment with interferon (P score, 0.63), somatostatin analogues (P score, 0.56), surufatinib (P score, 0.48), sunitinib (P score, 0.39), placebo (P score, 0.12), and dactolisib (P score, 0.06). All therapies except interferon, sunitinib, and dactolisib showed significantly higher disease control rates than placebo (Figure 4, Table 5).

4.

Treatment efficacy in pNET. Network plot (A) and Forest plot (B) for disease control in pNET. The thickness of the edges in the network plots is proportional to the inverse standard errors of the pairwise comparisons, and the numbers indicate the number of studies. One three‐arm study is marked by shading. Each section in the Forest plots refers to one treatment (in bold) compared to all others. An odds ratio larger than one indicates increased disease control of the bold treatment. A hazard ratio smaller than one indicates a reduced risk for progression for the bold treatment. All therapies are listed in order of their P‐scores, with the most effective therapy on top. Heterogeneity was assessed by the between‐study variance tau2, Cochran's Q with a P value, and I2. N refers to the total number of patients, and n to the number of patients with disease control. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to rate the quality of evidence of estimates from pairwise and network meta‐analysis. The final network meta‐analysis GRADE evidence quality corresponds to *very low, **low, ***moderate, and ****high. SSA refers to somatostatin analogues.

1. Comparison of all treatment options from the network meta‐analysis of disease control in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNET).

| Dactolisib | 0.17 (0.04 to 0.68) | 0.19 (0.04 to 0.87) | 0.22 (0.03 to 1.41) | 0.19 (0.04 to 1.04) | 0.56 (0.13 to 2.37) | 0.24 (0.05 to 1.07) | 0.32 (0.07 to 1.58) | 0.28 (0.06 to 1.38) |

| 5.89 (1.46 to 23.7) | Everolimus | 1.14 (0.63 to 2.04) | 1.27 (0.36 to 4.49) | 1.14 (0.44 to 2.95) | 3.29 (2.21 to 4.90) | 1.40 (0.79 to 2.46) | 1.91 (0.90 to 4.06) | 1.65 (0.76 to 3.61) |

| 5.18 (1.14 to 23.5) | 0.88 (0.49 to 1.58) | Everolimus + SSA | 1.12 (0.33 to 3.79) | 1.00 (0.41 to 2.46) | 2.89 (1.61 to 5.19) | 1.23 (0.77 to 1.97) | 1.68 (0.71 to 4.00) | 1.46 (0.60 to 3.54) |

| 4.62 (0.71 to 30.2) | 0.78 (0.22 to 2.76) | 0.89 (0.26 to 3.02) | Interferon | 0.90 (0.29 to 2.79) | 2.58 (0.75 to 8.81) | 1.09 (0.36 to 3.37) | 1.50 (0.37 to 5.98) | 1.30 (0.32 to 5.26) |

| 5.16 (0.96 to 27.8) | 0.88 (0.34 to 2.26) | 1.00 (0.41 to 2.43) | 1.12 (0.36 to 3.47) | Interferon + SSA | 2.88 (1.16 to 7.13) | 1.22 (0.57 to 2.61) | 1.67 (0.55 to 5.07) | 1.45 (0.47 to 4.47) |

| 1.79 (0.42 to 7.64) | 0.30 (0.20 to 0.45) | 0.35 (0.19 to 0.62) | 0.39 (0.11 to 1.33) | 0.35 (0.14 to 0.86) | Placebo | 0.42 (0.26 to 0.70) | 0.58 (0.31 to 1.10) | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.98) |

| 4.22 (0.94 to 19.0) | 0.72 (0.41 to 1.26) | 0.81 (0.51 to 1.31) | 0.91 (0.30 to 2.81) | 0.82 (0.38 to 1.75) | 2.36 (1.43 to 3.88) | SSA | 1.37 (0.61 to 3.08) | 1.19 (0.51 to 2.73) |

| 3.09 (0.63 to 15.1) | 0.52 (0.25 to 1.11) | 0.60 (0.25 to 1.42) | 0.67 (0.17 to 2.67) | 0.60 (0.20 to 1.82) | 1.72 (0.91 to 3.27) | 0.73 (0.32 to 1.65) | Sunitinib | 0.87 (0.34 to 2.19) |

| 3.56 (0.72 to 17.6) | 0.60 (0.28 to 1.32) | 0.69 (0.28 to 1.67) | 0.77 (0.19 to 3.12) | 0.69 (0.22 to 2.13) | 1.99 (1.02 to 3.88) | 0.84 (0.37 to 1.94) | 1.15 (0.46 to 2.91) | Surufatinib |

Effects are odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

SSA: somatostatin analogues

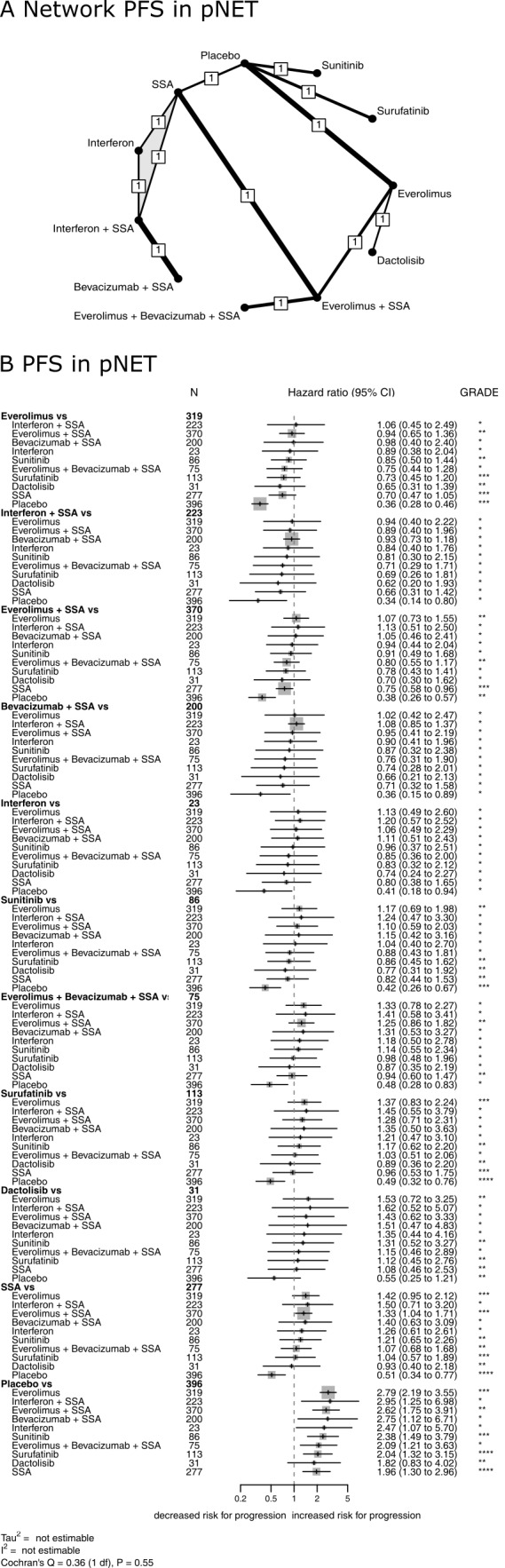

Ten RCTs with one 3‐arm trial (Faiss 2003; Kulke 2016; Kulke 2017 (1); Pavel 2011; Phan 2015 (2); Raymond 2011 (1); Salazar 2018; Xu 2020 (p); Yao 2011; Yao 2017) assessed progression‐free survival for 11 different therapies in pNETs (Figure 5). Again, the network meta‐analysis found that single therapy with everolimus and combination therapies with a somatostatin analogue were highly effective, with HRs between 0.34 and 0.38 versus placebo. The lowest hazard for progression was found after treatment with everolimus (P score, 0.75), followed by interferon plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.74), everolimus plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.68), bevacizumab plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.65), interferon (P score, 0.58), sunitinib (P score, 0.56), everolimus plus bevacizumab plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.42), surufatinib (P score, 0.41), dactolisib (P score, 0.35), somatostatin analogues (P score, 0.33), and placebo (P score, 0.01). All therapies but dactolisib significantly reduced the hazard for progression compared with placebo (Figure 5, Table 6).

5.

Treatment efficacy in pNET. Network plot (A) and Forest plot (B) for progression‐free survival in pNET. The thickness of the edges in the network plots is proportional to the inverse standard errors of the pairwise comparisons, and the numbers indicate the number of studies. One three‐arm study is marked by shading. Each section in the Forest plots refers to one treatment (in bold) compared to all others. An odds ratio larger than one indicates increased disease control of the bold treatment. A hazard ratio smaller than one indicates a reduced risk for progression for the bold treatment. All therapies are listed in order of their P‐scores, with the most effective therapy on top. Heterogeneity was assessed by the between study variance tau2, Cochran's Q with a P value, and I2. N refers to the total number of patients, and n to the number of patients with disease control. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to rate the quality of evidence of estimates from pairwise and network meta‐analysis. The final network meta‐analysis GRADE evidence quality corresponds to *very low, **low, ***moderate, and ****high. SSA refers to somatostatin analogues.

2. Comparison of all treatment options from the network meta‐analysis of progression‐free survival in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNET).

| Bevacizumab + SSA | 0.66 (0.21 to 2.13) | 1.02 (0.42 to 2.47) | 0.76 (0.31 to 1.90) | 0.95 (0.41 to 2.19) | 0.90 (0.41 to 1.96) | 1.08 (0.85 to 1.37) | 0.36 (0.15 to 0.89) | 0.71 (0.32 to 1.58) | 0.87 (0.32 to 2.38) | 0.74 (0.28 to 2.01) |

| 1.51 (0.47 to 4.83) | Dactolisib | 1.53 (0.72 to 3.25) | 1.15 (0.46 to 2.89) | 1.43 (0.62 to 3.33) | 1.35 (0.44 to 4.16) | 1.62 (0.52 to 5.07) | 0.55 (0.25 to 1.21) | 1.08 (0.46 to 2.53) | 1.31 (0.52 to 3.27) | 1.12 (0.45 to 2.76) |

| 0.98 (0.40 to 2.40) | 0.65 (0.31 to 1.39) | Everolimus | 0.75 (0.44 to 1.28) | 0.94 (0.65 to 1.36) | 0.89 (0.38 to 2.04) | 1.06 (0.45 to 2.49) | 0.36 (0.28 to 0.46) | 0.70 (0.47 to 1.05) | 0.85 (0.50 to 1.44) | 0.73 (0.45 to 1.20) |

| 1.31 (0.53 to 3.27) | 0.87 (0.35 to 2.19) | 1.33 (0.78 to 2.27) | Everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA | 1.25 (0.86 to 1.82) | 1.18 (0.50 to 2.78) | 1.41 (0.58 to 3.41) | 0.48 (0.28 to 0.83) | 0.94 (0.60 to 1.47) | 1.14 (0.55 to 2.34) | 0.98 (0.48 to 1.96) |

| 1.05 (0.46 to 2.41) | 0.70 (0.30 to 1.62) | 1.07 (0.73 to 1.55) | 0.80 (0.55 to 1.17) | Everolimus + SSA | 0.94 (0.44 to 2.04) | 1.13 (0.51 to 2.50) | 0.38 (0.26 to 0.57) | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.96) | 0.91 (0.49 to 1.68) | 0.78 (0.43 to 1.41) |

| 1.11 (0.51 to 2.43) | 0.74 (0.24 to 2.27) | 1.13 (0.49 to 2.60) | 0.85 (0.36 to 2.00) | 1.06 (0.49 to 2.29) | Interferon | 1.20 (0.57 to 2.52) | 0.41 (0.18 to 0.94) | 0.80 (0.38 to 1.65) | 0.96 (0.37 to 2.51) | 0.83 (0.32 to 2.12) |

| 0.93 (0.73 to 1.18) | 0.62 (0.20 to 1.93) | 0.94 (0.40 to 2.22) | 0.71 (0.29 to 1.71) | 0.89 (0.40 to 1.96) | 0.84 (0.40 to 1.76) | Interferon + SSA | 0.34 (0.14 to 0.80) | 0.66 (0.31 to 1.42) | 0.81 (0.30 to 2.15) | 0.69 (0.26 to 1.81) |

| 2.75 (1.12 to 6.71) | 1.82 (0.83 to 4.02) | 2.79 (2.19 to 3.55) | 2.09 (1.21 to 3.63) | 2.62 (1.75 to 3.91) | 2.47 (1.07 to 5.70) | 2.95 (1.25 to 6.98) | Placebo | 1.96 (1.30 to 2.96) | 2.38 (1.49 to 3.79) | 2.04 (1.32 to 3.15) |

| 1.40 (0.63 to 3.09) | 0.93 (0.40 to 2.18) | 1.42 (0.95 to 2.12) | 1.07 (0.68 to 1.68) | 1.33 (1.04 to 1.71) | 1.26 (0.61 to 2.61) | 1.50 (0.71 to 3.20) | 0.51 (0.34 to 0.77) | SSA | 1.21 (0.65 to 2.26) | 1.04 (0.57 to 1.89) |

| 1.15 (0.42 to 3.16) | 0.77 (0.31 to 1.92) | 1.17 (0.69 to 1.98) | 0.88 (0.43 to 1.81) | 1.10 (0.59 to 2.03) | 1.04 (0.40 to 2.70) | 1.24 (0.47 to 3.30) | 0.42 (0.26 to 0.67) | 0.82 (0.44 to 1.53) | Sunitinib | 0.86 (0.45 to 1.62) |

| 1.35 (0.50 to 3.63) | 0.89 (0.36 to 2.20) | 1.37 (0.83 to 2.24) | 1.03 (0.51 to 2.06) | 1.28 (0.71 to 2.31) | 1.21 (0.47 to 3.10) | 1.45 (0.55 to 3.79) | 0.49 (0.32 to 0.76) | 0.96 (0.53 to 1.75) | 1.17 (0.62 to 2.20) | Surufatinib |

Effects are hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

SSA: somatostatin analogues

The quality of evidence in pNETs was generally the highest for everolimus and surufatinib. The detailed results of the quality assessment are displayed in Table 7 and Table 8.

3. Estimates of effects and quality ratings for disease control in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNET).

| Direct evidence | Indirect evidence | Network meta‐analysis | ||||

| Comparison | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Quality of evidence | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Quality of evidence | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Quality of evidence |

| Dactolisib vs everolimus | 0.17 (0.04 to 0.68) | Low*,§ | 0.17 (0.04 to 0.68) | Low§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs everolimus + SSA | 0.19 (0.04 to 0.87) | Very low||,§ | 0.19 (0.04 to 0.87) | Very low§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs interferon | 0.22 (0.03 to 1.41) | Very low|||,§§ | 0.22 (0.03 to 1.41) | Very low§§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs interferon + SSA | 0.19 (0.04 to 1.04) | Very low||,¶,§§ | 0.19 (0.04 to 1.04) | Very low§§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs placebo | 0.56 (0.13 to 2.37) | Very low|,§§ | 0.56 (0.13 to 2.37) | Very low§§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs SSA | 0.24 (0.05 to 1.07) | Very low|,§§ | 0.24 (0.05 to 1.07) | Very low§§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs sunitinib | 0.32 (0.07 to 1.58) | Very low|,§§ | 0.32 (0.07 to 1.58) | Very low§§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs surufatinib | 0.28 (0.06 to 1.38) | Very low|,§§ | 0.28 (0.06 to 1.38) | Very low§§ | ||

| Everolimus vs everolimus + SSA | 1.41 (0.65 to 3.08) | Very low**,§ | 0.86 (0.35 to 2.08) | Very low|,¶,§ | 1.14 (0.63 to 2.04) | Very low§ |

| Everolimus vs interferon | 1.27 (0.36 to 4.49) | Very low|||,§§ | 1.27 (0.36 to 4.49) | Very low§§ | ||

| Everolimus vs interferon + SSA | 1.14 (0.44 to 2.95) | Very low||,¶,§ | 1.14 (0.44 to 2.95) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus vs placebo | 3.08 (2.01 to 4.72) | High | 5.06 (1.68 to 15.2) | Very low||,¶¶ | 3.29 (2.21 to 4.90) | High |

| Everolimus vs SSA | 1.40 (0.79 to 2.46) | Low|,§ | 1.40 (0.79 to 2.46) | Low§ | ||

| Everolimus vs sunitinib | 1.91 (0.90 to 4.06) | Moderate§ | 1.91 (0.90 to 4.06) | Moderate§ | ||

| Everolimus vs surufatinib | 1.65 (0.76 to 3.61) | Moderate§ | 1.65 (0.76 to 3.61) | Moderate§ | ||

| Everolimus + SSA vs interferon | 1.12 (0.33 to 3.79) | Very low|||,¶,§§ | 1.12 (0.33 to 3.79) | Very low§§ | ||

| Everolimus + SSA vs interferon + SSA | 1.00 (0.41 to 2.46) | Very low||,¶,§ | 1.00 (0.41 to 2.46) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus + SSA vs placebo | 2.89 (1.61 to 5.19) | Moderate| | 2.89 (1.61 to 5.19) | Moderate | ||

| Everolimus + SSA vs SSA | 1.36 (0.80 to 2.30) | Low‡,§ | 0.83 (0.29 to 2.37) | Very low||,§§ | 1.23 (0.77 to 1.97) | Moderate |

| Everolimus + SSA vs sunitinib | 1.68 (0.71 to 4.00) | Very low|,§ | 1.68 (0.71 to 4.00) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus + SSA vs surufatinib | 1.46 (0.60 to 3.54) | Very low|,§ | 1.46 (0.60 to 3.54) | Very low§ | ||

| Interferon vs interferon + SSA | 1.07 (0.31 to 3.72) | Very low**,‡,§§ | 0.39 (0.03 to 5.94) | Very low|||,¶,§§ | 0.90 (0.29 to 2.79) | Very low#,§§ |

| Interferon vs placebo | 2.58 (0.75 to 8.81) | Very low|||,§§ | 2.58 (0.75 to 8.81) | Very low§§ | ||

| Interferon vs SSA | 0.93 (0.28 to 3.16) | Very low**,‡,§§ | 2.64 (0.15 to 46.3) | Very low|||,¶,§§ | 1.09 (0.36 to 3.37) | Very low#,§§ |

| Interferon vs sunitinib | 1.50 (0.37 to 5.98) | Very low|||,§§ | 1.50 (0.37 to 5.98) | Very low§§ | ||

| Interferon vs surufatinib | 1.30 (0.32 to 5.26) | Very low|||,§§ | 1.30 (0.32 to 5.26) | Very low§§ | ||

| Interferon + SSA vs placebo | 2.88 (1.16 to 7.13) | Very low||,¶ | 2.88 (1.16 to 7.13) | Very low | ||

| Interferon + SSA vs SSA | 1.22 (0.57 to 2.61) | Very low*,‡,§ | 1.22 (0.57 to 2.61) | Very low§ | ||

| Interferon + SSA vs sunitinib | 1.67 (0.55 to 5.07) | Very low||,¶,§§ | 1.67 (0.55 to 5.07) | Very low§§ | ||

| Interferon + SSA vs surufatinib | 1.45 (0.47 to 4.47) | Very low||,¶,§§ | 1.45 (0.47 to 4.47) | Very low§§ | ||

| Placebo vs SSA | 0.38 (0.21 to 0.67) | Moderate‡ | 0.62 (0.22 to 1.75) | Very low||,¶,§§ | 0.42 (0.26 to 0.70) | Moderate |

| Placebo vs sunitinib | 0.58 (0.31 to 1.10) | Moderate§ | 0.58 (0.31 to 1.10) | Moderate§ | ||

| Placebo vs surufatinib | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.98) | High | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.98) | High | ||

| SSA vs sunitinib | 1.37 (0.61 to 3.08) | Low|,§ | 1.37 (0.61 to 3.08) | Low§ | ||

| SSA vs surufatinib | 1.19 (0.51 to 2.73) | Low|,§ | 1.19 (0.51 to 2.73) | Low§ | ||

| Sunitinib vs surufatinib | 0.87 (0.34 to 2.19) | Moderate§ | 0.87 (0.34 to 2.19) | Moderate§ |

The confidence assessment addressed *risk of bias, †inconsistency, ‡indirectness, §imprecision, and #incoherence. Indirect estimates were potentially rated down for intransitivity.

Severe limitations are indicated by two symbols. Contributing direct evidence was of |moderate, ||low or |||very low quality.

Abbreviations: SSA: somatostatin analogues; CI: confidence interval

4. Estimates of effects and quality ratings for progression‐free survival in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNET).

| Direct evidence | Indirect evidence | Network meta‐analysis | ||||

| Comparison | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Quality of evidence | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Quality of evidence | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Quality of evidence |

| Bevacizumab + SSA vs dactolisib | 0.66 (0.21 to 2.13) | Very low|||,¶,§§ | 0.66 (0.21 to 2.13) | Very low§§ | ||

| Bevacizumab + SSA vs everolimus | 1.02 (0.42 to 2.47) | Very low|||,¶,§ | 1.02 (0.42 to 2.47) | Very low§ | ||

| Bevacizumab + SSA vs everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA | 0.76 (0.31 to 1.90) | Very low|||,¶¶,§ | 0.76 (0.31 to 1.90) | Very low§ | ||

| Bevacizumab + SSA vs everolimus + SSA | 0.95 (0.41 to 2.19) | Very low|||,¶¶,§ | 0.95 (0.41 to 2.19) | Very low§ | ||

| Bevacizumab + SSA vs interferon | 0.90 (0.41 to 1.96) | Very low|||,¶,§ | 0.90 (0.41 to 1.96) | Very low§ | ||

| Bevacizumab + SSA vs interferon + SSA | 1.08 (0.85 to 1.37) | Low*,‡ | 1.08 (0.85 to 1.37) | Low | ||

| Bevacizumab + SSA vs placebo | 0.36 (0.15 to 0.89) | Very low|||,¶ | 0.36 (0.15 to 0.89) | Very low | ||

| Bevacizumab + SSA vs SSA | 0.71 (0.32 to 1.58) | Very low|||,¶,§ | 0.71 (0.32 to 1.58) | Very low§ | ||

| Bevacizumab + SSA vs sunitinib | 0.87 (0.32 to 2.38) | Very low|||,¶,§§ | 0.87 (0.32 to 2.38) | Very low§§ | ||

| Bevacizumab + SSA vs surufatinib | 0.74 (0.28 to 2.01) | Very low|||,¶,§ | 0.74 (0.28 to 2.01) | Very low§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs everolimus | 1.53 (0.72 to 3.25) | Low*,§ | 1.53 (0.72 to 3.25) | Low§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA | 1.15 (0.46 to 2.89) | Very low||,¶,§ | 1.15 (0.46 to 2.89) | Very low§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs everolimus + SSA | 1.43 (0.62 to 3.33) | Very low||,§ | 1.43 (0.62 to 3.33) | Very low§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs interferon | 1.35 (0.44 to 4.16) | Very low||,§§ | 1.35 (0.44 to 4.16) | Very low§§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs interferon + SSA | 1.62 (0.52 to 5.07) | Very low||,§§ | 1.62 (0.52 to 5.07) | Very low§§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs placebo | 0.55 (0.25 to 1.21) | Low|,§ | 0.55 (0.25 to 1.21) | Low§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs SSA | 1.08 (0.46 to 2.53) | Low|,§ | 1.08 (0.46 to 2.53) | Low§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs sunitinib | 1.31 (0.52 to 3.27) | Low|,§ | 1.31 (0.52 to 3.27) | Low§ | ||

| Dactolisib vs surufatinib | 1.12 (0.45 to 2.76) | Low|,§ | 1.12 (0.45 to 2.76) | Low§ | ||

| Everolimus vs everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA | 0.75 (0.44 to 1.28) | Very low||,¶,§ | 0.75 (0.44 to 1.28) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus vs everolimus + SSA | 1.01 (0.65 to 1.57) | Low** | 0.78 (0.39 to 1.57) | Very low|,¶,§ | 0.94 (0.65 to 1.36) | Low |

| Everolimus vs interferon | 0.89 (0.38 to 2.04) | Very low||,§ | 0.89 (0.38 to 2.04) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus vs interferon + SSA | 1.06 (0.45 to 2.49) | Very low||,§ | 1.06 (0.45 to 2.49) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus vs placebo | 0.35 (0.27 to 0.45) | High | 0.45 (0.21 to 0.99) | Very low||,¶¶ | 0.36 (0.28 to 0.46) | High |

| Everolimus vs SSA | 0.70 (0.47 to 1.05) | High | 0.70 (0.47 to 1.05) | High | ||

| Everolimus vs sunitinib | 0.85 (0.50 to 1.44) | Moderate§ | 0.85 (0.50 to 1.44) | Moderate§ | ||

| Everolimus vs surufatinib | 0.73 (0.45 to 1.20) | High | 0.73 (0.45 to 1.20) | High | ||

| Everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA vs everolimus + SSA | 1.25 (0.86 to 1.82) | Moderate* | 1.25 (0.86 to 1.82) | Moderate | ||

| Everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA vs interferon | 1.18 (0.50 to 2.78) | Very low||,¶,§ | 1.18 (0.50 to 2.78) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA vs interferon + SSA | 1.41 (0.58 to 3.41) | Very low||,¶¶,§ | 1.41 (0.58 to 3.41) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA vs placebo | 0.48 (0.28 to 0.83) | Low|,¶ | 0.48 (0.28 to 0.83) | Low | ||

| Everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA vs SSA | 0.94 (0.60 to 1.47) | Moderate| | 0.94 (0.60 to 1.47) | Moderate | ||

| Everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA vs sunitinib | 1.14 (0.55 to 2.34) | Very low|,¶,§ | 1.14 (0.55 to 2.34) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus + bevacizumab + SSA vs surufatinib | 0.98 (0.48 to 1.96) | Very low|,¶,§ | 0.98 (0.48 to 1.96) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus + SSA vs interferon | 0.94 (0.44 to 2.04) | Very low||,¶,§ | 0.94 (0.44 to 2.04) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus + SSA vs interferon + SSA | 1.13 (0.51 to 2.50) | Very low||,¶,§ | 1.13 (0.51 to 2.50) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus + SSA vs placebo | 0.38 (0.26 to 0.57) | Low| | 0.38 (0.26 to 0.57) | Low | ||

| Everolimus + SSA vs SSA | 0.77 (0.59 to 1.00) | Moderate‡ | 0.60 (0.27 to 1.30) | Very low||,§ | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.96) | Moderate |

| Everolimus + SSA vs sunitinib | 0.91 (0.49 to 1.68) | Very low|,§ | 0.91 (0.49 to 1.68) | Very low§ | ||

| Everolimus + SSA vs surufatinib | 0.78 (0.43 to 1.41) | Very low|,§ | 0.78 (0.43 to 1.41) | Very low§ | ||

| Interferon vs interferon + SSA | 1.20 (0.57 to 2.52) | Very low**,‡,§ | 1.20 (0.57 to 2.52) | Very low§ | ||

| Interferon vs placebo | 0.41 (0.18 to 0.94) | Very low||| | 0.41 (0.18 to 0.94) | Very low | ||

| Interferon vs SSA | 0.80 (0.38 to 1.65) | Very low**,‡,§ | 0.80 (0.38 to 1.65) | Very low§ | ||

| Interferon vs sunitinib | 0.96 (0.37 to 2.51) | Very low|||,§ | 0.96 (0.37 to 2.51) | Very low§ | ||

| Interferon vs surufatinib | 0.83 (0.32 to 2.12) | Very low|||,§ | 0.83 (0.32 to 2.12) | Very low§ | ||

| Interferon + SSA vs placebo | 0.34 (0.14 to 0.80) | Very low||| | 0.34 (0.14 to 0.80) | Very low | ||

| Interferon + SSA vs SSA | 0.66 (0.31 to 1.42) | Very low**,‡,§ | 0.66 (0.31 to 1.42) | Very low§ | ||

| Interferon + SSA vs sunitinib | 0.81 (0.30 to 2.15) | Very low|||,§ | 0.81 (0.30 to 2.15) | Very low§ | ||

| Interferon + SSA vs surufatinib | 0.69 (0.26 to 1.81) | Very low|||,§ | 0.69 (0.26 to 1.81) | Very low§ | ||

| Placebo vs SSA | 1.72 (0.96 to 3.11) | Moderate§ | 2.22 (1.25 to 3.95) | Very low||,¶ | 1.96 (1.30 to 2.96) | High |

| Placebo vs sunitinib | 2.38 (1.49 to 3.79) | High | 2.38 (1.49 to 3.79) | High | ||

| Placebo vs surufatinib | 2.04 (1.32 to 3.15) | High | 2.04 (1.32 to 3.15) | High | ||

| SSA vs sunitinib | 1.21 (0.65 to 2.26) | Moderate§ | 1.21 (0.65 to 2.26) | Moderate§ | ||

| SSA vs surufatinib | 1.04 (0.57 to 1.89) | Moderate§ | 1.04 (0.57 to 1.89) | Moderate§ | ||

| Sunitinib vs surufatinib | 0.86 (0.45 to 1.62) | Moderate§ | 0.86 (0.45 to 1.62) | Moderate§ |

The confidence assessment addressed *risk of bias, †inconsistency, ‡indirectness, §imprecision, and #incoherence. Indirect estimates were potentially rated down for intransitivity.

Severe limitations are indicated by two symbols. Contributing direct evidence was of |moderate, ||low or |||very low quality.

Abbreviations: SSA: somatostatin analogues; CI: confidence interval

Treatment efficacy in GI‐NETs

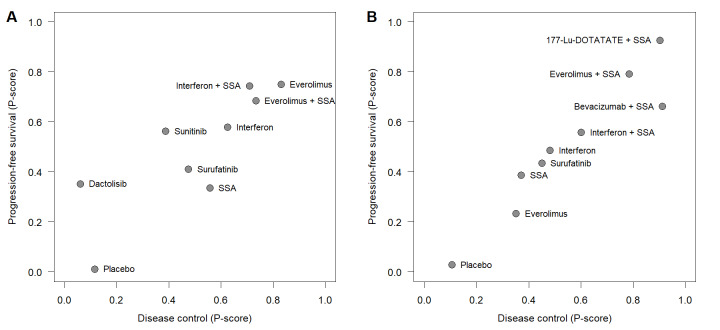

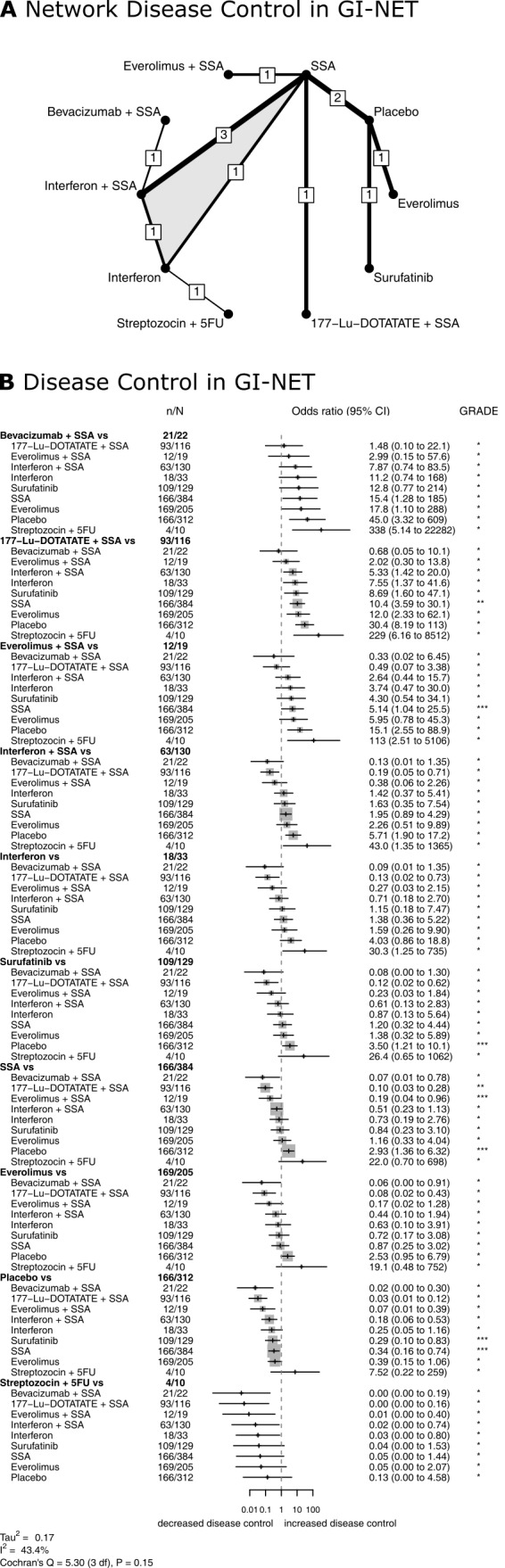

Eleven RCTs (Arnold 2005; Caplin 2014; Castellano 2013; Faiss 2003; Kölby 2003; Öberg 1989; Rinke 2009; Strosberg 2017; Xu 2020 (ep); Yao 2008 (1); Yao 2016) compared disease control rates for 10 different therapies in GI‐NETs (Figure 6). The network meta‐analysis found that combination therapies with a somatostatin analogue were highly effective. Bevacizumab plus a somatostatin analogue resulted in the highest disease control rate (P score, 0.91), followed by 177‐Lu‐DOTATATE plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.90), everolimus plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.78), interferon plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.60), interferon (P score, 0.48), surufatinib (P score, 0.45), somatostatin analogues (P score, 0.37), everolimus (P score, 0.35), placebo (P score, 0.11), and streptozocin plus fluorouracil (P score, 0.04). All therapies but interferon, everolimus, and streptozocin plus fluorouracil showed significantly higher disease control rates than placebo (Figure 6, Table 9).

6.

Treatment efficacy in GI‐NET. Network plot (A) and Forest plot (B) for disease control in GI‐NET. The thickness of the edges in the network plots is proportional to the inverse standard errors of the pairwise comparisons, and the numbers indicate the number of studies. One three‐arm study is marked by shading. Each section in the Forest plots refers to one treatment (in bold) compared to all others. An odds ratio larger than one indicates increased disease control of the bold treatment. A hazard ratio smaller than one indicates a reduced risk for progression for the bold treatment. All therapies are listed in order of their P‐scores, with the most effective therapy on top. Heterogeneity was assessed by the between study variance tau2, Cochran's Q with a P value, and I2. N refers to the total number of patients, and n to the number of patients with disease control. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to rate the quality of evidence of estimates from pairwise and network meta‐analysis. The final network meta‐analysis GRADE evidence quality corresponds to *very low, **low, ***moderate, and ****high. SSA refers to somatostatin analogues.

5. Comparison of all treatment options from the network meta‐analysis of disease control in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours (GI‐NET).

| 177‐Lu‐DOTATATE + SSA | 0.68 (0.05 to 10.1) | 12.0 (2.33 to 62.1) | 2.02 (0.30 to 13.8) | 7.55 (1.37 to 41.6) | 5.33 (1.42 to 20.0) | 30.4 (8.19 to 113) | 10.4 (3.59 to 30.1) | 229 (6.16 to 8512) | 8.69 (1.60 to 47.1) |

| 1.48 (0.10 to 22.1) | Bevacizumab + SSA | 17.8 (1.10 to 288) | 2.99 (0.15 to 57.6) | 11.2 (0.74 to 168) | 7.87 (0.74 to 83.5) | 45.0 (3.32 to 609) | 15.4 (1.28 to 185) | 338 (5.14 to 22282) | 12.8 (0.77 to 214) |

| 0.08 (0.02 to 0.43) | 0.06 (0.00 to 0.91) | Everolimus | 0.17 (0.02 to 1.28) | 0.63 (0.10 to 3.91) | 0.44 (0.10 to 1.94) | 2.53 (0.95 to 6.79) | 0.87 (0.25 to 3.02) | 19.1 (0.48 to 752) | 0.72 (0.17 to 3.08) |

| 0.49 (0.07 to 3.38) | 0.33 (0.02 to 6.45) | 5.95 (0.78 to 45.3) | Everolimus + SSA | 3.74 (0.47 to 30.0) | 2.64 (0.44 to 15.7) | 15.1 (2.55 to 88.9) | 5.14 (1.04 to 25.5) | 113 (2.51 to 5106) | 4.30 (0.54 to 34.1) |

| 0.13 (0.02 to 0.73) | 0.09 (0.01 to 1.35) | 1.59 (0.26 to 9.90) | 0.27 (0.03 to 2.15) | Interferon | 0.71 (0.18 to 2.70) | 4.03 (0.86 to 18.8) | 1.38 (0.36 to 5.22) | 30.3 (1.25 to 735) | 1.15 (0.18 to 7.47) |

| 0.19 (0.05 to 0.71) | 0.13 (0.01 to 1.35) | 2.26 (0.51 to 9.89) | 0.38 (0.06 to 2.26) | 1.42 (0.37 to 5.41) | Interferon + SSA | 5.71 (1.90 to 17.2) | 1.95 (0.89 to 4.29) | 43.0 (1.35 to 1365) | 1.63 (0.35 to 7.54) |

| 0.03 (0.01 to 0.12) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.30) | 0.39 (0.15 to 1.06) | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.39) | 0.25 (0.05 to 1.16) | 0.18 (0.06 to 0.53) | Placebo | 0.34 (0.16 to 0.74) | 7.52 (0.22 to 259) | 0.29 (0.10 to 0.83) |

| 0.10 (0.03 to 0.28) | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.78) | 1.16 (0.33 to 4.04) | 0.19 (0.04 to 0.96) | 0.73 (0.19 to 2.76) | 0.51 (0.23 to 1.13) | 2.93 (1.36 to 6.32) | SSA | 22.0 (0.70 to 698) | 0.84 (0.23 to 3.10) |

| 0.00 (0.00 to 0.16) | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.19) | 0.05 (0.00 to 2.07) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.40) | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.80) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.74) | 0.13 (0.00 to 4.58) | 0.05 (0.00 to 1.44) | Streptozocin + 5FU | 0.04 (0.00 to 1.53) |

| 0.12 (0.02 to 0.62) | 0.08 (0.00 to 1.30) | 1.38 (0.32 to 5.89) | 0.23 (0.03 to 1.84) | 0.87 (0.13 to 5.64) | 0.61 (0.13 to 2.83) | 3.50 (1.21 to 10.1) | 1.20 (0.32 to 4.44) | 26.4 (0.65 ‐ 1062) | Surufatinib |

Effects are odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

SSA: somatostatin analogues

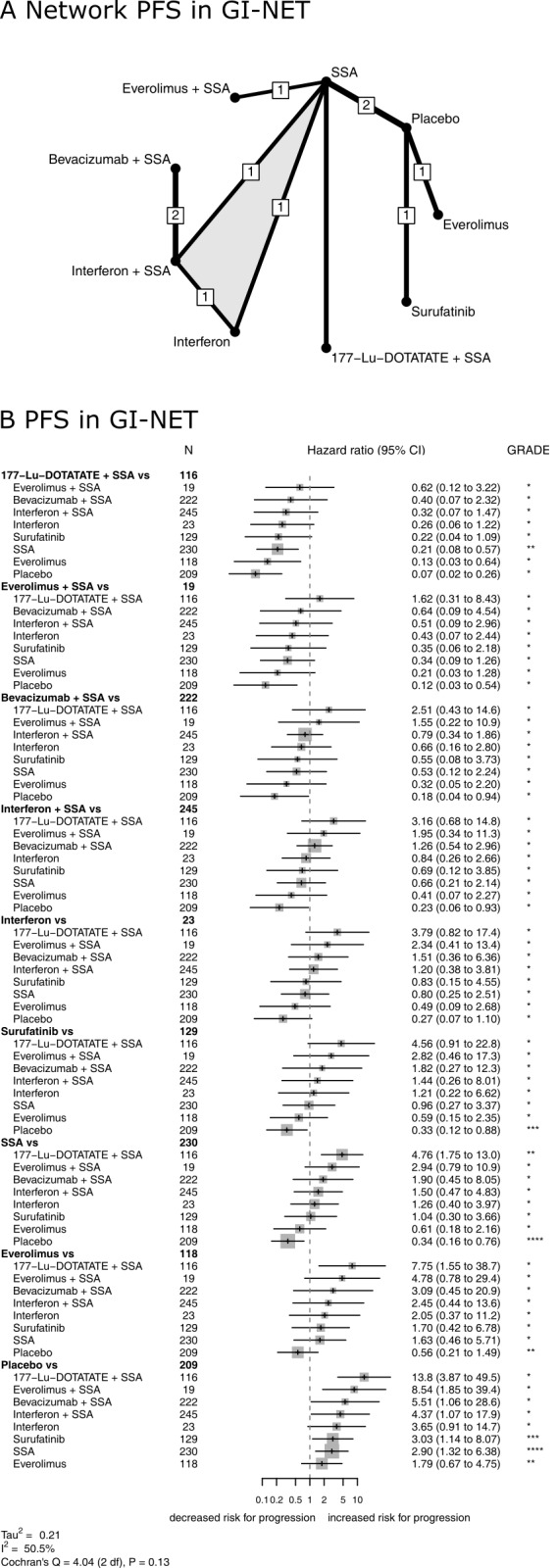

Nine RCTs (Castellano 2013; Dasari 2015; Faiss 2003; Rinke 2009; Singh 2018 (1); Strosberg 2017; Xu 2020 (ep); Yao 2008 (1); Yao 2017) assessed progression‐free survival for nine different therapies in GI‐NETS (Figure 7). Again, the network meta‐analysis found that combination therapies with a somatostatin analogue were highly effective with HRs between 0.07 and 0.23 versus placebo. The lowest hazard for progression was found after treatment with 177‐Lu‐DOTATATE plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.93), followed by everolimus plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.79), bevacizumab plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.66), interferon plus a somatostatin analogue (P score, 0.56), interferon (P score, 0.49), surufatinib (P score, 0.43), somatostatin analogues (P score, 0.39), everolimus (P score, 0.23), and placebo (P score, 0.03). All therapies but interferon and everolimus significantly reduced the hazard for progression compared with placebo (Figure 7, Table 10).

7.