Abstract

Seven sequential isolates of echovirus type 30 (EV30) were recovered over 22 months from a child with severe combined immune deficiency syndrome. The nucleotide sequences of the 5′ halves of the genomes (4,400 nucleotides) of the first (S1) and last (S7) isolates were determined and compared with that of the EV30 Bastianni reference strain, also determined in this study. In genome regions P1 and P2, 101 variations were identified between the two isolates. Synonymous differences far outnumbered nonsynonymous differences. Amino acid changes affected both capsid and nonstructural polypeptides (particularly 2B). The VP1 nucleotide sequences of the seven isolates were determined to analyze genome evolution during the chronic infection. In the phylogenetic tree, the seven isolates were directly related to the prototype strain in an individual monophyletic group, strongly suggesting that the chronic infection in the child arose from a single persistent EV30 isolate. Four lineages were observed in the persistent isolates. Isolates S2, S4, S5, and S6 were close relatives of one another, whereas isolates S1 and S3 formed individual lineages. Isolate S7, distantly related to all other isolates, formed the fourth lineage. These findings suggest the quasispecies nature of the genomes of the seven sequential EV30 isolates. Grouping of persistent isolates on the basis of replicative capacities was consistent with phylogenetic relationships. Overall, the results indicate that genetically related EV30 variants with different replicative capacities coexisted in a carrier state, probably in the gastrointestinal tract, during the infection of the child.

Enteroviruses are common human pathogens responsible for asymptomatic infections and several clinical manifestations including aseptic meningitis (7, 33), encephalitis (5, 33), and severe diseases in the newborn (6, 9, 29) and immunocompromised hosts (18, 27).

Enterovirus infections in humans are normally self-limited by humoral immunity. In persons with immune deficiencies (for instance, agammaglobulinemia), enteroviruses have been responsible for chronic (persistent), sometimes fatal, infections (16, 18, 27). Prolonged excretion of an enterovirus over a period of several months has been described in immunodeficient patients. Echovirus type 11 was the most common cause of chronic infection, but other enteroviruses, like echovirus type 30 (EV30), were also involved (10). EV30 is one of the most prevalent enteroviruses (13, 28) and is usually associated with acute aseptic meningitis (1), a common illness that occurs both as sporadic cases of infection and as seasonal outbreaks (2, 12, 15, 24, 26), which contribute to the active circulation of the serotype in the general population.

In this study, we report on the genetic analysis of seven EV30 isolates collected over a period of 22 months from stool specimens of a young girl with combined immune deficiency syndrome associated with cartilage-hair hypoplasia (34). The patient had congenital short-limbed dwarfism, and her immune deficiency was unusually severe, affecting both cell-mediated immunity and antibody-mediated immunity. She developed autoimmune manifestations and chronic EV30 infection. The first isolate was recovered in September 1989 when the child, then age 6, presented with gastrointestinal manifestations. Six further, consecutive isolates were collected in the period up to July 1991.

These isolates were studied retrospectively to determine whether the patient had been reinfected or whether the infection was persistent. To analyze the genetic characteristics of the seven consecutive isolates, the study was performed in two stages. First, the nucleotide sequences of the 5′ halves of the genomes (about 4,400 nucleotides) of the first and seventh isolates, which were recovered 22 months apart, were determined. In addition, because only partial sequences were known for the EV30/1958/USA/Bastianni prototype strain (12, 14), the nucleotide sequence of the 5′ half of the genome of this strain was also determined and was compared with those of sequential isolates. In the second part of the study, we used the molecular data for the amplification and sequencing of the complete VP1-coding sequences of the other five isolates. Phylogenetic relationships, inferred from the nucleotide sequences, showed four lineages in the seven isolates. Finally, we analyzed the replicative capacities of the consecutive isolates and showed phenotypic variations that were consistent with the phylogenetic differences observed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus strains and identification.

Seven enterovirus isolates (Table 1) were sequentially recovered from a child with severe combined immune deficiency (34). Each isolate was recovered from one stool specimen after inoculation of the specimen onto standard cultures of MRC5 cells (human lung embryonic fibroblasts) at the Laboratory of Virology of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Rangueil (Toulouse, France). Virus identification by neutralization tests with the antiserum pools of Lim and Benyesh-Melnick (25) was performed and showed that all isolates were EV30. Propagation of the isolates was performed in MRC5 cells by previously described methods (3) and was limited to a maximum of two passages. The EV30 prototype strain, EV30/1958/USA/Bastianni (32), and two recent isolates (91CF670 and 98CF746) collected from patients with aseptic meningitis were included in this study as controls for the phylogenetic analyses.

TABLE 1.

Echovirus type 30 isolates used in this studya

| Virus isolate | Isolation (yr, month, city, country) | Characteristic | Designation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 89T2090 | 1989, September, Toulouse, FR | First sequential isolate | S1 |

| 90T248 | 1990, January, Toulouse, FR | Second sequential isolate | S2 |

| 90T423 | 1990, February, Toulouse, FR | Third sequential isolate | S3 |

| 90T2328 | 1990, August, Toulouse, FR | Fourth sequential isolate | S4 |

| 90T2657 | 1990, September, Toulouse, FR | Fifth sequential isolate | S5 |

| 90T2917 | 1990, October, Toulouse, FR | Sixth sequential isolate | S6 |

| 91TLC | 1991, July, Toulouse, FR | Seventh sequential isolate | S7 |

| 91CF670 | 1991, July, Clermont-Ferrand, FR | Control isolate | 91CF670 |

| 98CF746 | 1998, May, Clermont-Ferrand, FR | Control isolate | 98CF746 |

| Bastiannib | 1958, NK, New-York, USA | Reference isolate | EV30 |

Abbreviations: FR, France; USA, United States; NK, not known.

The reference strain was obtained from the World Health Collaborating Center, National Reference Center for Enteroviruses and Hepatitis A.

Single-cycle infection and virus titration assays.

Confluent MRC5 cell monolayers in 35-mm tissue culture dishes were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and were infected with one of the viruses examined at a multiplicity of infection of one to five cytopathic units (most probable number of cytopathic units [MPNCU]) per cell (3). After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, the inoculum was discarded, and the cells were washed twice with PBS and fed Eagle's minimum essential medium containing 2% fetal calf serum. At the postinfection times indicated below, the infected cells were recovered in the medium and the virus was released by three cycles of freezing and thawing. Each virus was studied in duplicate (two independent single-cycle infections). Virus production was determined in each sample, by end-point dilution in microtitration assays with MRC5 cells, as described elsewhere (3).

Preparation of cytoplasmic RNAs from infected MRC5 cells and reverse transcription.

Cytoplasmic RNAs were isolated from infected MRC5 cells grown in 60-mm tissue culture dishes at 5 to 7 h postinfection (4). Infected MRC5 cell monolayers were washed once with cold PBS and were lysed in 200 μl of cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40). Cytoplasmic RNAs were separated from cellular proteins by three consecutive extractions, one with acid phenol (pH 4.3), one with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25/24/1), and one with chloroform. The synthesis of cDNA was performed in a volume of 50 μl from 5 μg of cytoplasmic RNA and with oligo(dT)18 as a primer. First-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) was used according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Oligonucleotides used in the study.

Oligonucleotides 5NCNOT, VP4b, 5NC622, and 2C were designed from the available sequences of prototype strains, and oligonucleotides EV30P1 and EV30P2 were constructed from sequences determined in this study for strain Bastianni and isolates S1 and S7. Oligonucleotides 5NCNOT (5′-TCA GCG GCC GCT TAA AAC AGC CTG TGG-3′) and VP4b (5′-GTT GAC ACT TGA GCT CCC-3′) were constructed from the first 16 nucleotides of the enterovirus genome and from 18 nucleotides at the 5′ end of the coding region (sites 744 to 761 in the genome of coxsackie B virus type 3 [CBV3]), respectively. Oligonucleotides 5NC622 (5′-TAT TGG ATT GGC CAT CCG G-3′) and 2C (5′-CGG CAT TTG GAC TTG AAC TGT AT-3′) were constructed from two motifs conserved in the 5′ noncoding region (5′NCR; sites 624 to 642 in CBV3) and in the 2C-coding sequence (sites 4376 to 4398). EV30P1 (5′-TCC GCG TGC AAC GAT TTC TC-3′) and EV30P2 (5′-CTC CCA CAC GCA GTT CTG CC-3′) were designed from conserved motifs in sequences encoding VP3 and 2A, respectively.

PCR amplification of cDNAs.

The 5′NCR of the EV30 RNA was amplified by a previously described method (4) with primers 5NCNOT and VP4b. In addition, a large fragment of the viral RNA (approximately 3,800 bases long) was amplified with the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Meylan, France) and primers 5NC622 and 2C. The amplification reactions were performed from 2 to 5 μl of the cDNA in a mixture containing each of the primers at a concentration of 300 nM, each of the four deoxynucleotides at a concentration of 350 μM, and 1.75 U of the enzyme mix (thermostable Taq and Pwo DNA polymerases) in 35 cycles. The first cycle consisted of denaturation for 2 min at 94°C, hybridization for 30 s at 52°C, and elongation for 2 min and 10 s at 68°C and was followed by 34 cycles each of 20 s at 94°C, 30 s at 52°C, and 2 min and 10 s at 68°C, Samples were run on the Omnigene thermocycler (Hybaid, Paris, France). The VP1-coding sequences of the EV30 isolates were specifically amplified with the two primers EV30P1 and EV30P2 by using the conditions described above but with a shorter elongation time (1 min). For each isolate, six to eight PCRs were performed, and the amplification products were brought together and were purified from low-melting-point agarose by standard phenol-chloroform extractions.

Nucleotide sequencing of PCR products.

The nucleotide sequences of the purified PCR products were determined at Euro Séquences Gènes Service (Montigny-Le-Bretonneux, France). The nucleotide sequences were determined with the ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Perkin-Elmer Corporation), resolved with the 373 DNA sequencer, and analyzed with the ABI PRISM 373 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Phylogenetic analysis.

The phylogenetic relationships of reference strain Bastianni with previously characterized prototype enteroviruses and with the sequential EV30 isolates characterized in this study were estimated from comparisons of their nucleotide and amino acid sequences. The nucleotide and amino acid sequences used in this study were aligned with the computer programs ESEE3 (8) and CLUSTALW (39). For optimal alignment, a core alignment was produced with VP1 amino acid sequences of poliovirus type 1 Mahoney (PV1M) and CBV3 to provide information about the three-dimensional structure of the viruses (17, 30). A master alignment was then produced by aligning the amino acid sequences of 30 other enteroviruses with the core alignment. The nucleotide sequences were aligned by using amino acid alignment as a guide to obtain the final data set. Pairwise sequence comparisons from the VP1 data set were performed with the MEGA program (23). A phylogenetic tree was constructed from the alignment by the neighbor-joining method (35) as implemented in CLUSTALW. Sites at which there was a gap in any of the aligned sequences were excluded from all comparisons, and distances were corrected by using Kimura's two-parameter method (20). The reliability of the branching orders was estimated by bootstrapping (1,000 samples). A phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 sequences was also performed with the Puzzle computer program (37). The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed by the quartet puzzling method from molecular distances estimated by maximum likelihood. Distances were calculated with the model of nucleotide substitutions of Tamura and Nei (38). The transition/transversion parameter, nucleotide frequencies, and the parameter α for a gamma distribution of substitution rates were estimated directly from the data set.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of EV30/1958/USA/Bastianni and of the seven isolates studied have been deposited with the EMBL data Library under the accession numbers AJ131523 and AJ133656 to AJ133662, respectively.

RESULTS

Sequencing of the 5′ half of the genome for the EV30 Bastianni prototype strain and for the first (S1) and seventh (S7) EV30 sequential isolates.

Two independent PCR products spanning 4,400 nucleotides were produced from the genome of the EV30/1958/USA/Bastianni prototype strain and of sequential isolates S1 and S7. The nucleotide sequences of the overlapping cDNAs were determined. The genome organization of the three viruses was determined by comparison of the genomes with those of other reference enteroviruses. As for all other previously characterized enteroviruses, the 3′ end of the 5′NCR was defined by the first AUG triplet that was not closely followed by a stop codon. Translation of the viral RNA probably started at the 7th AUG triplet (nucleotides 757 to 759) in strain Bastianni and at the 10th AUG triplet in the sequential isolates. Alignment of the amino acid sequence derived from the open reading frame in EV30 allowed confident prediction of the boundaries for each functional polypeptide.

Nucleotide sequences of 5′NCRs of EV30 sequential isolates.

In the 5′NCR, isolates S1 and S7 shared 84% nucleotide similarity with the Bastianni strain and 98% nucleotide similarity with each other. Half of the 18 nucleotide differences observed between the two isolates were clustered in the last 90 nucleotides located before the initiation codon. Four differences were observed in spacers connecting the secondary-structure domains of the 5′NCR, and five were scattered in three domains. The nucleotide sequence of the 5′NCR was also determined for isolates S3 and S5. Interstrain variations observed in sequential isolates ranged from 1.2 to 4.2% and were consistent with the intratypic variations observed in EV25 and CBV5 isolates collected independently from different individuals (4, 22). The proportion of observed differences in sequential isolates was also consistent with that determined in poliovirus type 3 (PV3) isolates collected during an outbreak in Finland in 1984 (21). There were more differences between isolates S1 and S7 than between the most distant PV3 isolates. Hence, the 5′NCR was not suitable for determination of whether the EV30 sequential isolates were derived from a persistent virus or whether they were acquired independently.

Nucleotide sequences of the 5′ halves of the coding regions in EV30 sequential isolates S1 and S7.

In the 5′ half of the open reading frame that was sequenced (3,650 nucleotides), isolates S1 and S7 shared 83.7% nucleotide sequence similarity with strain Bastianni and 97.7% similarity with each other. Of the 83 nucleotide differences observed between the two isolates, 21 were missense differences, and 16 of these resulted in amino acid variations in capsid polypeptides. Nucleotide differences were also observed in genome region P2. In the sequence encoding polypeptide 2Apro, of 11 differences only 1 led to an amino acid change. In polypeptide 2B, three amino acid changes were observed. Finally, eight nucleotide differences were observed in the 320 nucleotides examined for polypeptide 2C, and only one resulted in an amino acid difference between isolates S1 and S7.

Phylogenetic clustering of the EV30 sequential isolates on the basis of the complete VP1 nucleotide sequence.

The phylogenetic relationships of the seven EV30 sequential isolates were constructed from the entire VP1-coding sequence (876 nucleotides). The VP1-coding sequence was chosen for general and specific reasons. First, VP1 is the largest capsid polypeptide in enteroviruses and comprises both stable and variable domains that correspond approximately, in the complete virion structure, to internal β-sheets and exposed loops, respectively. Accordingly, the sequences encoding these domains would be expected to give different phylogenetic information. More specifically, the VP1-coding sequence was the most divergent sequence of the genome in the closely related isolates S1 and S7 and thus was the best suited for analysis of genetic evolution from closely related sequences.

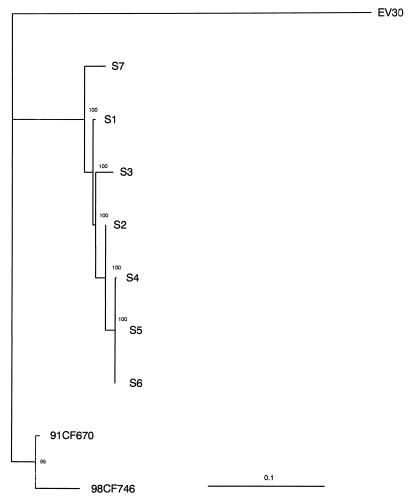

The phylogenetic tree obtained by the neighbor-joining method showed that the seven consecutive isolates were directly related to the Bastianni prototype strain. The branching order of the viral sequences showed that all isolates diverged from a common ancestor and constituted a monophyletic group distinct from the control viruses 91CF670 and 98CF746 isolated from patients with aseptic meningitis. In addition, a major lineage comprising sequences of isolates S4, S5, S6, and S2 was observed. The phylogenetic tree was also reconstructed from the VP1 sequences by the quartet puzzling method with the Puzzle computer program, which estimates pairwise distances by maximum likelihood (37). The Tamura-Nei model (38) of sequence evolution was used with four categories of substitution rates to approximate the gamma distribution. The parameters for the model were estimated directly from the data set: transition/transversion parameter (10.21 ± 2.15), pyrimidine/purine transition parameter (1.13 ± 0.25), and nucleotide frequencies. The parameter α, which is inversely related to the extent of rate variation at sites, had a low value (0.18 ± 0.04), indicating the existence of a high degree of variation of the substitution rate across nucleotide sites in VP1 sequences. The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1) reconstructed from maximum likelihood distances was similar to the tree obtained by the neighbor-joining method. The phylogenetic relationships observed in Fig. 1 confirmed the existence of a major lineage and showed three additional lineages, one each for isolates S1, S3, and S7. All the internal branches had a very high degree of reliability (>95%) and were therefore strongly supported.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships of EV30 persistent isolates to one another. Pairwise maximum likelihood distances were estimated by the Tamura-Nei model (38) from the VP1 sequences by using all informative nucleotide sites (199 in 876). The tree was reconstructed by the quartet puzzling method (37), and the reliability value of each internal branch indicates (in percent) how often the corresponding cluster was found among the 1,000 intermediate trees. In 210 quartets analyzed, only 7 (3.3%) were unresolved. Branch length was drawn to the indicated scale. EV30 was used as the outgroup to root the trees.

Evolutionary rate of VP1-coding sequences in sequential isolates.

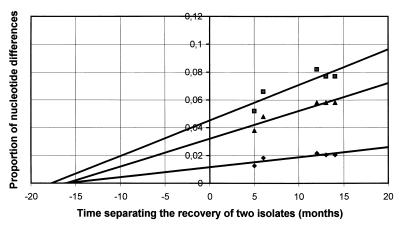

The relationships between the number of nucleotide substitutions and time was examined for the VP1-coding sequences except for that of the most divergent isolate (the last isolate). The substitution rate was estimated from the nucleotide differences observed between isolates S2 to S6 and isolate S1 (Fig. 2). The proportion of the nucleotide differences in each pairwise comparison (differences at all sites, differences at synonymous sites, and differences at the third codon position) were plotted against the divergence time of the two isolates compared. All isolates were distributed along a straight line, suggesting that they evolved at a constant substitution rate from a common ancestor. The substitution rate for the overall observed nucleotide divergence, estimated as the regression coefficient of the linear relationships, was 8.4 × 10−3 (0.8%) substitution per year per site. This rate was due to an extremely high rate of synonymous substitutions, 31.2 × 10−3 (3.12%) per year per synonymous site (Fig. 2). On the assumption that the virus had evolved at a constant rate since the initial infection of the child, the time of the primary infection was estimated to be 15 to 20 months before isolation of the first isolate.

FIG. 2.

Duration of chronic EV30 infection estimated from nucleotide substitution rates in VP1-coding sequence. The proportion of nucleotide differences at all sites (diamonds), at synonymous sites (squares), and at the third codon positions (triangles) were calculated for each pairwise comparison with the MEGA computer program (23). Nucleotide substitutions were extrapolated back to zero substitution.

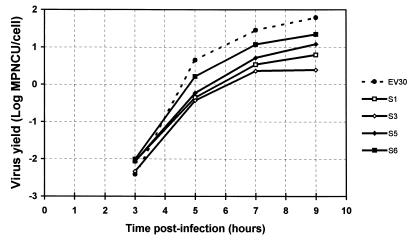

Phenotypic differences between the EV30 sequential isolates.

The production of infectious virions in MRC5 cells infected with the Bastianni strain or with one of the four sequential isolates studied (isolates S1, S3, S5, and S6) was measured at 37°C and at various postinfection times (Fig. 3). The kinetics of the five strains studied were almost identical in shape; however, major differences in the final virus yields were observed. The virus yield for the four sequential isolates studied was lower than that for the reference strain: when compared with this strain, isolates S3, S1, S5, and S6 produced 25-, 10-, 5-, and 3-fold fewer viruses, respectively. When the virus yields were compared with that of the first isolate, individual differences were noted: isolate S3 produced 2.5-fold fewer viruses, whereas isolates S5 and S6 produced 1.9- and 3.9-fold more viruses, respectively. The third isolate was particularly interesting because the maximum virus yield was less than 5 infectious units per cell. In a second experiment, performed in duplicate, all sequential isolates were compared to the reference strain. Virus yield was determined 18 h postinfection under the conditions described above for single-cycle infections. As expected, virus yield was the highest for strain Bastianni (1.2 log MPNCU per cell). Isolates grouped in two clusters. The first included isolates S4, S5, and S6 (0.43, 0.69, and 0.96 log MPNCU per cell, respectively), and the second included isolates S7, S3, S2, and S1, which had the lowest virus yield (−0.34, 0.05, 0.11, and 0.20 log MPNCU per cell, respectively). These results were consistent with the phylogenetic relationships that showed that isolates S4, S5, and S6 were close relatives which evolved significantly from the first isolate and which acquired the highest degree of replicative efficiency in vitro. Isolate S2, which was genetically related but not similar to isolates S4, S5, and S6, had a lower level of replicative efficiency, and isolates S1, S3, and S7 had significant genetic variations and low levels of replicative efficiency.

FIG. 3.

Time course of virus production in MRC5 cells. MRC5 cells were seeded at 2 × 105 per 35-mm culture dish and were cultured for 4 days before inoculation. Data are the means of two independent experiments, and virus titers were determined in duplicate for each experiment.

DISCUSSION

This is the first report to describe molecular differences and to analyze genetic and phenotypic evolution in isolates of EV30 recovered from a patient with severe combined immune deficiency associated with cartilage-hair hypoplasia, a distinctive form of short-limbed dwarfism. Patients with this syndrome are unusually susceptible to severe infections with varicella-zoster virus (40) and are also at risk of enterovirus infection (36). Because enteroviruses are known to cause chronic infection in immunocompromised hosts (27), the main aim of the retrospective study of the EV30 isolates was to determine if the seven isolates were derived from a single persistent virus chronically excreted over at least 22 months.

The phylogenetic analysis of the entire VP1-coding sequence showed that genetically all isolates were closely related to one another and are directly related to the EV30 Bastianni prototype strain, thereby confirming the serotypes of the viruses determined by the neutralization tests. The sequential isolates grouped in a monophyletic cluster, which shows that the child was persistently infected with one virus strain that diverged into several variants during the 22-month period. Genetic relationships, inferred from the analysis of VP1-coding sequences, showed four lineages for the seven persistent isolates collected from September 1989 to July 1991. In the major lineage, isolates S4, S5, and S6 were identical or differed at only a few nucleotide sites and were closely related to isolate S2. The other lineages comprised isolates S1, S3, and S7, respectively. These results show that persistent isolates form a genetically heterogeneous viral population and, thereby, strongly suggest the quasispecies structures of the genomes in the virus population (11).

The evolution rates, measured from nucleotide differences in the first six isolates (with isolate S7 being excluded because of its high degree of divergence), showed a constant accumulation of changes in VP1 over 13 months. The estimated rate of evolution (3.1% synonymous substitutions per synonymous site per year) is consistent with the rate found for a persistent PV1 strain isolated from an immune-deficient patient with vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (19) and for a persistent coxsackie A virus type 15 (CAV15) in an agammaglobulinemic patient (31). The initial infection of the child with EV30 was estimated from the rate of evolution of the VP1-coding sequences to be 15 to 20 months before the isolation of the first isolate in September 1989. This suggests that infection began long before the isolation of the first EV30 isolate and was not associated with critical clinical symptoms. The interval between the initial infection and the first isolation of an EV30 isolate, which was associated with gastrointestinal manifestations, is in good agreement with clinical data because virus isolation ended a 2-year period during which prophylaxis and administration of immunoglobulins successfully prevented infectious complications in the child (34).

Despite the divergence, isolate S7 is definitely related to the other persistent isolates by multiple genetic characteristics not only in the VP1-coding sequence but also in other genome sequences. We found 98 nucleotide differences between isolates S1 and S7 in the 5′ halves of their genomes. These differences correspond to a genetic divergence of 2.3%, equivalent to that observed in the VP1 sequence. In genome region P1, we found rates of nucleotide substitutions ranging from 5.3 × 10−3 (VP4 sequence) to 14.6 × 10−3 (VP1 sequence) substitutions per nucleotide site per year. These high rates are not consistent with a separate evolution of isolate S7 in competition with strains with higher replicative capacities since its replicative efficiency in vitro was lower than those of the other isolates. The isolation of three other virus isolates with low yields indicates instead the coexistence in a carrier state, probably in the gastrointestinal tract, of genetically related viruses with different replicative capacities during the infection of the child. Differences in replication efficiency observed between sequential isolates are consistent with the results of the phylogenetic analysis. Isolates S4, S5, and S6, which belong to the same genetic lineage and which have identical VP1-coding sequences, have similar replicative capacities. In contrast, isolates S1, S3, and S7 are major genetic variants from the former isolates and replicate less efficiently. It is not yet possible to identify exactly the molecular determinants that are responsible for the phenotypic differences observed. However, multiple genetic variations occurred in the 5′ halves of the genomes of isolates S1 and S7 in regions P1 and P2 and suggest strongly that multiple factors, both in the capsid and in nonstructural polypeptides, are involved in the phenotypic differences observed.

In conclusion, our study provides further evidence of the susceptibility of immunodeficient patients to enteroviruses circulating in the general population. The genetic characteristics and replicative capacities of EV30 sequential isolates obtained in cell cultures show that viruses with genetic variations in different genome regions and with different biological properties can be isolated from the same individual during the course of a chronic infection. The selection of isolates with different replicative capacities in vitro suggests that new biological features (cell specificity, tissue tropism, virulence) may be selected in EV30 replicating during a persistent infection in immunodeficient patients. These isolates are useful tools for understanding the relationships between nucleotide sequences, protein structure, and biological properties in echoviruses, and the study of such isolates may also enable us to identify virulent and attenuated determinants in virus strains that emerge in different susceptible human populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Danielle Thouvenot of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center, National Reference Center for Enteroviruses (Lyon, France), for providing us with the reference strain of EV30. We thank Jeffrey Watts for revision of the English manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a grant from Ministère de l'Education Nationale de la Recherche et de la Technologie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkinson P J, Sharland M, Maguire H. Predominant enteroviral serotypes causing meningitis. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:373–374. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.4.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aymard M, Chomel J-J, Lina B, Thouvenot D. Annual report 1997. Lyon, France: National Reference Center for Enteroviruses and Hepatitis A; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailly J-L, Chambon M, Peigue-Lafeuille H, Charbonné F. Replication of echovirus type 25 JV4 reference strain and wild type strains in MRC5 cells compared with that of poliovirus type 1. Arch Virol. 1994;137:327–340. doi: 10.1007/BF01309479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailly J-L, Borman A M, Peigue-Lafeuille H, Kean K M. Natural isolates of echovirus type 25 with extensive variations in IRES sequences and different translational efficiencies. Virology. 1996;215:83–96. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bello M. Viral meningoencephalitis caused by enterovirus in Cuba from 1990–1995. Rev Argent Microbiol. 1997;29:176–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergman I, Painter M J, Wald E R, Chiponis D, Holland A L, Taylor H G. Outcome in children with enteroviral meningitis during the first year of life. J Pediatr. 1987;110:705–709. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berlin L E, Rorabaugh M L, Heldrich F, Roberts K, Doran T, Modlin J F. Aseptic meningitis in infants <2 years of age: diagnosis and etiology. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:888–892. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.4.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabot E L, Beckenbach A T. Simultaneous editing of multiple nucleic acid and protein sequences with ESEE. Comput Appl Biosci. 1989;5:233–234. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambon M, Delage C, Bailly J-L, Gaulme J, Dechelotte P, Henquell C, Jallat C, Peigue-Lafeuille H. Fatal hepatic necrosis in a neonate with echovirus 20 infection: use of the polymerase chain reaction to detect enterovirus in liver tissue. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:523–524. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherry J D. Enteroviruses: polioviruses (poliomyelitis), coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and enteroviruses. In: Feigin R D, Cherry J D, editors. Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: The W.B. Saunders Co.; 1992. pp. 1705–1753. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domingo E, Holland J J. RNA virus mutations and fitness for survival. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:151–178. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drebot M A, Nguyan C Y, Campbell J J, Lee S H S, Forward K R. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus outbreaks in Canada during 1991–1992: identification of echovirus 30 and coxsakievirus B1 strains by amplicon sequencing. J Med Virol. 1994;44:340–347. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890440406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Druyts-Voets E. Epidemiological features of entero non-poliovirus isolations in Belgium 1980–94. Epidemiol Infect. 1997;119:71–77. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gjoen K, Bruu A L, Orstavik I. Intratypic variability of echovirus type 30 in part of the VP4/VP2 coding region. Arch Virol. 1996;141:901–908. doi: 10.1007/BF01718164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorgievski-Hrisoho M, Schumacher J-D, Vilimonovic N, Germann D, Matter L. Detection by PCR of enteroviruses in cerebrospinal fluid during a summer outbreak of aseptic meningitis in Switzerland. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2408–2412. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2408-2412.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertel N T, Pedersen F K, Heilmann C. Coxsackie B3 virus encephalitis in a patient with agammaglobulinemia. Eur J Pediatr. 1989;148:642–643. doi: 10.1007/BF00441520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogle J M, Chow M, Filman D J. Three-dimensional structure of poliovirus at 2.9 Å resolution. Science. 1985;229:1358–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.2994218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson J P, Yolken R H, Goodman D, Winkelstein J A, Nagel J E. Prolonged excretion of group A coxsackievirus in an infant with agammaglobulinemia. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:712. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.5.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kew O M, Sutter R W, Nottay B K, McDonough M J, Prevots D R, Quick L, Pallansch M A. Prolonged replication of a type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus in an immunodeficient patient. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2893–2899. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2893-2899.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinnunen L, Pöyry T, Hovi T. Generation of genetic lineages during an outbreak of poliomyelitis. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2483–2489. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-10-2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kopecka H, Brown B, Pallansch M A. Genotypic variation in coxsackievirus B5 isolates from three different outbreaks in the United States. Virus Res. 1995;38:125–136. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00055-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 1.01. University Park, Pa: The Pennsylvania State University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonardi G P, Greenberg A J, Costello P, Szabo K. Echovirus type 30 infection associated with aseptic meningitis in Nassau County, New York, USA. Intervirology. 1993;36:53–56. doi: 10.1159/000150321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim K A, Benyesh-Melnick M. Typing of viruses by combination of antiserum pools. Application to typing of enteroviruses (coxsackie and ECHO) J Immunol. 1960;84:309–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez-Alcala M I, Rodriguez Priego M, de la Cruz Morgado D, Barcia Ruiz J M. Outbreak of meningitis caused by type 30. An Esp Pediatr. 1997;46:237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKinney R E, Jr, Katz S L, Wilfert C M. Chronic enteroviral meningoencephalitis in agammaglobulinemic patients. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:334–356. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melnick J L. Enteroviruses: polioviruses, coxsackieviruses, echoviruses and newer enteroviruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, editors. Virology. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 549–605. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modlin J F. Update on enterovirus infections in infants and children. Adv Pediatr Infect Dis. 1997;12:155–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muckelbauer J K, Kremer M, Minor I, Diana G, Dutko F, Groarke J, Pevear D C, Rossmann M G. The structure of coxsakievirus B3 at 3.5 Å resolution. Structure. 1995;3:653–667. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Neil K M, Pallansch M A, Winkelstein J A, Lock T M, Modlin J F. Chronic group A coxsackievirus infection in agammaglobulinemia: demonstration of genomic variation of serotypically identical isolates persistently excreted by the same patient. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:183–186. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plager H, Decher W. A newly-recognized enterovirus isolated from cases of aseptic meningitis. Am J Hyg. 1963;77:26–28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rotbart H A. Meningitis and encephalitis. In: Rotbart H A, editor. Human enterovirus infections. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 271–289. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubie H, Graber D, Fischer A, Tauber M T, Maroteaux P, Robert A, Le Deist F, Rochiccioli P, Griscelli C, Reignier C. Hypoplasie du cartilage et des cheveux avec déficit immunitaire combiné. Ann Pediatr. 1989;36:390–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saulsburry F T, Winkelstein J A, Davis L E, Hsu L H, D'Souza B J, Gutcher G R, Butler I J. Combined immunodeficiency and vaccine-related poliomyelitis in a child with cartilage-hair hypoplasia. J Pediatr. 1975;86:868–872. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strimmer K, von Haeseler A. Quartet puzzling: a quartet maximum likelihood method for reconstructing tree topologies. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:964–969. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Virolainen M, Savilahti E, Kaitila I, Perheentupa J. Cellular and humoral immunity in cartilage-hair hypoplasia. Pediatr Res. 1978;12:961–966. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197810000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]