Abstract

Simple Summary

TCP transcription factors (TF) are indispensable for the normal functioning of plant growth and development. This study identified and performed phylogenetic analysis on 218 TCP genes in four cotton species. We also observed conserved exon-intron structures and protein motif distribution patterns in GhTCP genes. GhTCP62 was enriched in the axillary bud, indicating that it plays a role in branching. GhTCP62 is a nuclear-localized TF, the overexpression of which decreases the number of cauline-leaf branches and rosette-leaf branches in Arabidopsis. Additionally, the expression levels of HB21 and HB40 genes increased in plants with GhTCP62 overexpression, demonstrating that GhTCP62 could regulate branching by regulating HB21 and HB40. Collectively, the GhTCP62 TF located in the nucleus was highly enriched in the axillary buds, and GhTCP62 overexpression lines demonstrated fewer rosette-leaf branches and cauline-leaf branches, indicating that GhTCP62 regulates branching in Arabidopsis.

Abstract

TEOSINTE-BRANCHED1/CYCLOIDEA/PCF (TCP) transcription factors play an essential role in regulating various physiological and biochemical functions during plant growth. However, the function of TCP transcription factors in G. hirsutum has not yet been studied. In this study, we performed genome-wide identification and correlation analysis of the TCP transcription factor family in G. hirsutum. We identified 72 non-redundant GhTCP genes and divided them into seven subfamilies, based on phylogenetic analysis. Most GhTCP genes in the same subfamily displayed similar exon and intron structures and featured highly conserved motif structures in their subfamily. Additionally, the pattern of chromosomal distribution demonstrated that GhTCP genes were unevenly distributed on 24 out of 26 chromosomes, and that fragment replication was the main replication event of GhTCP genes. In TB1 sub-family genes, GhTCP62 was highly expressed in the axillary buds, suggesting that GhTCP62 significantly affected cotton branching. Additionally, subcellular localization results indicated that GhTCP62 is located in the nucleus and possesses typical transcription factor characteristics. The overexpression of GhTCP62 in Arabidopsis resulted in fewer rosette-leaf branches and cauline-leaf branches. Furthermore, the increased expression of HB21 and HB40 genes in Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GhTCP62 suggests that GhTCP62 may regulate branching by positively regulating HB21 and HB40.

Keywords: TCP, plant architecture, GhTCP62, shoot branching, cotton, Arabidopsis thaliana

1. Introduction

The structure of the aerial parts of plants plays a decisive role in crop development and yield as well as in photosynthesis [1,2]. For instance, wheat varieties with short and sturdy stems produce higher yields and harvest efficiency and are more resistant to lodging [3]. The yield of soybean varieties differs due to differences in branching plasticity [4,5]. In the case of maize (Zea mays), plants with an upright structure are better suited for intensive planting [6]. Plant architecture is determined by the position and differentiation of the meristem, which is reflected in plant organs such as stems and branches. The shoot apical meristem (SAM) affects plant elongation and axillary meristems (AMs) determine lateral branching, which ultimately alters the shoots’ architecture [7,8]. So far, studies have shown that the biological effects of plant structure can be regulated by changing gene expression, in which transcription factors (TFs) play a surprising role [9,10]. The overexpression of GmMYB14 in soybeans leads to a decrease in endogenous Brassinosteroid (BR) content and a semi-dwarf and compact plant structure, which improves yield [11]. Similarly, the overexpression of AtDREB1B caused a significant decrease in the quantitative and morphological traits in Arabidopsis, particularly plant height [12]. The expression of the tomato WRKY gene SlWRKY23 in transgenic Arabidopsis displayed a host of branching in inflorescences [13]. The gain-of-function mutant exb1-D enhances WRKY71 gene expression and produces a dense and stunted phenotype [14].

The plant-specific transcription factor family TEOSINTE-BRANCHED1/CYCLOIDEA/PCF (TCP) has been known to regulate the development of plant branches in many species [15,16]. These transcription factors share a conserved domain consisting of 59 amino acids at the N-terminus, which is known as the TCP domain. This domain was initially identified in four proteins encoded by apparently unrelated genes, which were subsequently named "TCP": TEOSINTE BRANCHED1 (TB1) in maize (Zea mays), CYCLOIDEA (CYC) in snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus), and PROLIFERATING CELL NUCLEAR ANTIGEN FACTOR1 (PCF1) and PROLIFERATING CELL NUCLEAR ANTIGEN FACTOR2 (PCF2) in rice (Oryza sativa). TB1 is involved in regulating the growth inhibition of the formation of axillary buds on the lateral branches [17,18], CYC is expressed in early lateral flowering regions and regulates the symmetrical development of flowers [19], and PCF1 and PCF2 bind to the promoter of the rice PCNA gene and help regulate the cell cycle [20]. TCP proteins are grouped into two subfamilies: class I can bind GGNCCCAC elements and mainly induces cell division; class II can bind GTGGNCCC elements and inhibits growth and development [21,22]. Additionally, class Ⅱ is further divided into the CINCINNATA (CIN) and CYC/TB1 subfamilies, based on differences in TCP domain sequences [23,24]. As genome technologies have advanced, more and more plant species with TCP family genes have been identified, including 24 members of the TCP transcription factor family in Arabidopsis [25]; 22 TCPs in rice (Oryza sativa) [26]; 36 TCPs in the tomato genome [27]; 46 ZmTCP genes in maize (Zea mays L.) [28]; 17 TCPs in the leaf transcriptome of tea tree (C. sinensis) [29]; 22 and 20 TCPs in wild (Hordeum vulgare subsp. spontaneum, Hs) and cultivated barley (Hordeum vulgare subsp. vulgare, Hv), respectively [30]; 42 TCPs in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) [31]; and 66 TCPs in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) [32]. Recent studies have analyzed TCP functionality and found the following: decreases in AtTCP2 and AtTCP4 transcripts regulate large and crinkly leaves (called the JAW phenotype); the overexpression of AtTCP4 leads to early maturity and smaller leaves in Arabidopsis [33]; when the expression levels of the triple T-DNA insertion mutant tcp5/13/17 are significantly knocked down, there is a delay in the flowering phenotype [34].

Cotton is an important global crop and produces valuable natural fibers. Gossypium hirsutum is an allotetraploid, which consists of A gene subgroup (At) and D gene subgroup (Dt). The A gene subgroup originates from Gossypium arboreum, and the D gene subgroup originates from Gossypium raimondii [35]. Recently, TCP genes have been identified and analyzed in several cotton varieties: 38 and 36 TCPs were identified in the genome of the diploid cotton species Gossypium raimondii and Gossypium arboreum, respectively, while 75 TCP genes were identified in sea-island cotton (Gossypium barbadense) and 73 in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) TM-1 genome [36,37]. In cotton, GbTCP promotes fiber elongation by regulating the content of endogenous JA [38]. GhCUC2 and GhTIE1 activate the transcriptional activity of GhBRC1 and inhibit branch development through ABA signaling [39]. GhTCP21 and GhTCP54 both responded to salt and drought stress [37]. GhTCP14 regulates auxin response, while the expression of transporter genes affects fiber differentiation and elongation [40]. While there has been significant research on how TCP transcription factors affect plant development, few studies have assessed the mechanism affecting the architecture of cotton plants.

In our study, 72 GhTCP family genes were systematically identified and analyzed, the first such genome-wide characterization in the upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) ZM24 genome. We also performed phylogenetic analysis, genomic structures, and conserved motifs analysis, sequences logo analysis for conserved amino acid residues, chromosomal location analysis, and synteny analysis. Next, we analyzed the TB1 clade, which can significantly affect the development of plant branches. We initially studied the tissue-specific expression profile of TB1clade members and then determined the subcellular localization of GhTCP62 in the leaf epidermal cells of Nicotiana benthamiana. We then overexpressed GhTCP62 to explore how it relates to branching in Arabidopsis. Our study provides insight into how TCP regulates branch development in Arabidopsis and lays the foundation for subsequently creating an ideal plant architecture suitable for intensive planting and mechanized harvesting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sequence Retrieval and Information Statistics of TCP Proteins

First, we downloaded genes containing the TCP domain in Arabidopsis from TAIR 10 (http://www.Arabidopsis.org, accessed on 30 March 2021). We then retrieved the Arabidopsis TCP genes using a query to identify TCP genes in Gossypium hirsutum, Gossypium raimondii, Gossypium arboreum, and Gossypium barbadense. The G. hirsutum and G. raimondii genome sequences were downloaded from the cotton functional genomics database (http://grand.cricaas.com.cn/home, accessed on 30 March 2021), and the G. arboreum and G. barbadense database genome sequences were downloaded from COTTONGEN (https://www.cottongen.org/, accessed on 30 March 2021). Next, the conserved domains of the proteins encoded by the homologous genes of G. hirsutum, G. raimondii, G. arboreum, and G. barbadense were analyzed using the NCBI Batch CD-Search (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi, accessed on 30 March 2021), batch SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/smart/batch.pl, accessed on 30 March 2021), and Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/search#tabview=tab1, accessed on 30 March 2021). We then renamed the TCP gene identified in four cotton species according to the position of the genes on the chromosomes. Furthermore, we located the chromosome of the TCP gene in G. hirsutum using the annotation file of its genome.

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis, Gene Structure and Conserved Motif

We performed multiple sequence alignments (MSA) of TCP proteins in Arabidopsis, G. hirsutum, G. raimondii, G. arboreum, and G. barbadense genomes using Muscle, with default settings [41]. Next, we constructed a rooted evolutionary tree using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method [42]. Finally, we constructed a separate phylogenetic tree containing all the GhTCP protein sequences for subsequent analysis.

The exons-introns coordinates of the genes were extracted from the genome gene annotation results, and the conserved motifs were predicted using the online MEME program (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme, accessed on 30 March 2021) [43], with default parameters. TBtools was used to display the gene structure and conserved motifs along with the phylogenetic tree [44].

2.3. Analyses of Chromosomal Distribution and Collinearity

The G. hirsutum genome annotation file (https://cottonfgd.org/about/download.html, accessed on 30 March 2021) was used to determine the chromosomal location of the GhTCP genes, after which a gff3-file was extracted. To map the physical location of the GhTCP genes, we used TBtools software to visualize the distribution of the TCP genes on the relevant chromosomes. For collinearity analysis, a collinearity module was generated for the TCP gene in G. hirsutum and Arabidopsis. We used these results to construct a collinearity map of the genes using CIRCOS software [45].

2.4. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

In this study, the Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia-0 (Col-0) was used as the wild-type (WT) and for the ectopic transformation of the GhTCP62 gene. The Arabidopsis seeds were disinfected with 75% alcohol and rinsed five times with sterile water. We placed the Arabidopsis seeds in a refrigerator at 4 °C for 72 h, in the dark, to vernalize the seeds. Next, we spread the seeds evenly on the Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium. The seedlings were grown at a constant temperature of 18–22 °C and under a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod, as previously described [46]. After seven days, the seedlings were transferred into pots containing a mixture of vegetative soil and vermiculite (v/v = 2/1) and grown at 18–22 °C under long-day conditions (16 h light and 8 h dark, 70% relative humidity). The Arabidopsis plants were grown in the growth chamber for a month and then used for transformation, as previously described [47,48,49].

The cotton material used in this study was ZM24, which is a variety of G. hirsutum. The cotton seeds were soaked in sterile water for 24 h before they were planted in a mixture of vegetative soil and vermiculite (v/v = 2/1). Subsequently, the cotton was grown with regular watering at 27/20 °C, 14/10 h of regulated conditions, and 75% humidity.

We also used tobacco for the subcellular localization experiments. First, we soaked the tobacco seeds in sterile water for 24 h. The seeds were then planted in pots containing a mixture of vegetative soil and vermiculite (v/v = 2/1). The tobacco was planted and regularly watered for two weeks at 27/20 °C, 14/10 h, and 75% humidity.

2.5. Gene Expression Assays

The cotton seedlings grew at 28 °C, with 16 h of light and 8 h of darkness, and were watered once every three days; after two months of growth, roots, stems, leaves, flowers, ovules, fibers, axillary bud and phyllophore were taken; and after flowering, fibers and ovules with 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25DPA are taken and immediately put into liquid nitrogen for preservation. For Arabidopsis, we obtained a rosette disc with a part of the stem to analyze the expression pattern. We then extracted the RNA using an RNAkey™ Reagent (SM129-02, Sevenbio, Beijing, China). An All-in-one First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit Ⅲ for qPCR (with dsDNase) (SM135-01, Sevenbio, Beijing, China) was used to extract the cDNAs, as previously described [50,51,52].

For the RT-qPCR, the following parameters were used: 94 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles at 94 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 10 s on a LightCycler 480 II qRT-PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Diluted cDNA was used for the RT-qPCR with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Tli RNaseH Plus, Takara, Dalian, China), while GhUBQ7 (accession No. DQ116441) was used as an internal control. We checked the dissociation curves of each reaction and used the cycle threshold (CT) 2−∆∆Ct method to calculate the expression level of each target gene [53], as previously described [54,55]. For the relative expression level, we take the root as the standard, and set its expression level as 1. The expression of genes in other tissues refers to the expression in the root. A minimum of three biological replicates was performed for each reaction. All the primers used in the real-time quantitative RT-PCR are listed in Table S3.

2.6. Construction of Overexpression Vector and Subcellular Localization Vector

All the vectors used in this study were constructed by one-step cloning. This method entails using primers with homologous arms and double restriction sites to amplify gene fragments, after which vectors with the same homologous arms and restriction sites are linked to the amplified gene fragments. We then attached these vectors with the Agrobacterium strain GV3101 using the freeze-thaw method.

For the GhTCP62 overexpression lines (OE), the GhTCP62 encoding region was amplified from full-length cDNA using GhTCP62-specific primers. Using the 35 s promoter of the Cauliflower mosaic virus, the full-length coding region of GhTCP62 was cloned into the EcoRI and KpnI enzyme sites of the pCAMBIA2300-GFP vector to produce the 35S::GhTCP62 construct, which was then attached to the Agrobacterium strain GV3101. The Arabidopsis transformation was performed via the floral dip method [56]. Transgenic plants were selected on an MS medium containing 50 µg·L−1 kanamycin. The primers used for the vector construction method are listed in Table S3.

For the subcellular localization of GhTCP62, we cloned the GhTCP62 encoding region into the pCAMBIA2300-YFP vector and fused it with the Agrobacterium strain GV3101. The Agrobacterium strain GV3101 was introduced into tobacco leaves via infiltration to detect transient expression. The tobacco plants were grown in the dark for 16 h and in light for 24–36 h. Finally, the YFP signal was detected using a confocal microscope.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of TCP Gene Family in G. hirsutum

For the Arabidopsis TCP family genes (Table S1), we identified the TCP family genes in G. hirsutum using NCBI Batch CD-Search, Batch SMART, and Pfam. We identified a total of 72 GhTCP genes in G. hirsutum. The GhTCP genes in G. hirsutum were named according to their position on the chromosomes, ranging from GhTCP1 to GhTCP72 (Table S2). We analyzed basic information about the TCP genes in G. hirsutum and Arabidopsis and found that the length of the amino acids of the 72 GhTCP transcription factors ranged from 196 (GhTCP72) to 550 (GhTCP2) amino acids, with an average of 357 amino acids. We also analyzed the basic information of the TCP family genes in Arabidopsis, and the results showed that the identified GhTCP genes had a similar coding length to that of Arabidopsis. We also observed the chromosomal positions of the GhTCP genes (Table S2).

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of TCP Gene Family

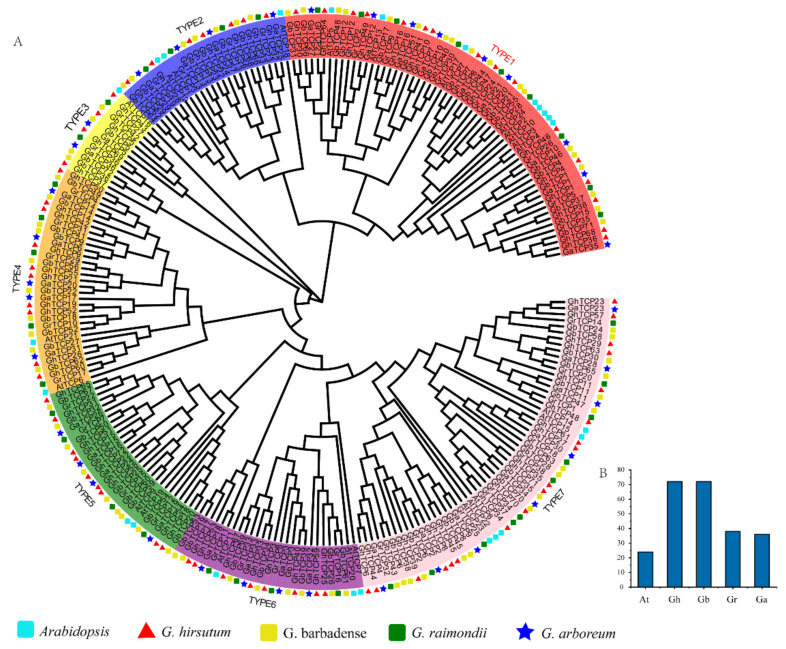

To explore the evolutionary history and phylogenetic relationship of the GhTCP genes, we identified 38 GrTCPs in G. raimondii, 36 GaTCPs in G. arboreum, and 72 GbTCPs in G. barbadense. Coupled with 23 AtTCPs and 72 GhTCPs, using the Neighbor-Joining method, a phylogenetic tree was constructed (Figure 1). According to the phylogenetic tree, the TCP gene family can be grouped into seven subfamilies, from TYPE1 to TYPE7. According to the sequence characteristics of the conserved domain of the TCP genes, the identified TCP genes can be further divided into two types: TYPE 1 and TYPE 2 belong to the second subfamily and the rest belong to the first subfamily [57]. Among them, TYPE1 (CIN) is the largest evolutionary branch, with 60 members, accounting for 24.8% of the total TCP proteins. TYPE3 is the smallest evolutionary branch, with only 13 members, accounting for 5.4% of total TCP proteins. Overall, the TCP protein family was sparsely distributed in different branches, indicating that the TCP protein family expanded before the lineage differentiation. In addition, the TCP proteins were unevenly distributed in some branches of the phylogenetic tree. Many TCP proteins in Arabidopsis had two or more counterparts in four cotton species, indicating that replication events occurred in the TCP proteins after differentiation in four cotton species and Arabidopsis.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of TCP gene family members from Arabidopsis, G. hirsutum, G. barbadense, G. raimondii, and G. arboreum. (A) An unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 6.0 and the Neighbor-Joining method, while the bootstrap test was performed with 1000 iterations. The seven subclades are indicated using different colors; TYPE1 belongs to the CIN protein, TYPE2 belongs to the TB1 protein, and TYPE3–7 belongs to the PCF protein. (B) Statistics of the number of TCP family genes in different species.

Many TCP proteins with similar functions in Arabidopsis are clustered on the same branch, indicating that the TCP proteins of cotton on the same branch could also have similar functions. For instance, in the subfamily of TYPE1, several studies have demonstrated the redundant role of eight CIN proteins in lateral organ organogenesis, which interfere with several cellular pathways that control leaf development [58,59,60]. The TYPE1 subfamily contains eight AtTCP proteins, 16 GhTCP proteins, 18 GbTCP proteins, nine GaTCP proteins, and nine GrTCP proteins. In TYPE 2, AtTCP1, AtTCP12 (BRANCHED2), and AtTCP18 (BRANCHED1) all belong to the TB1 protein, which plays a role in the formation of collateral and determines bud structure [61]. Bioinformatics analysis indicated that seven GhTCP proteins, seven GbTCP proteins, four GaTCP proteins, and four GrTCP proteins in a subfamily belong to the TB1 protein, indicating that these genes also play a role in the development of collateral branches. Additionally, in the TYPE7 group, there are 5 AtTCP proteins, 18 GhTCP proteins, 16 GbTCP proteins, 8 GaTCP proteins, and 10 GrTCP proteins clustered together, indicating that they may perform similar functions.

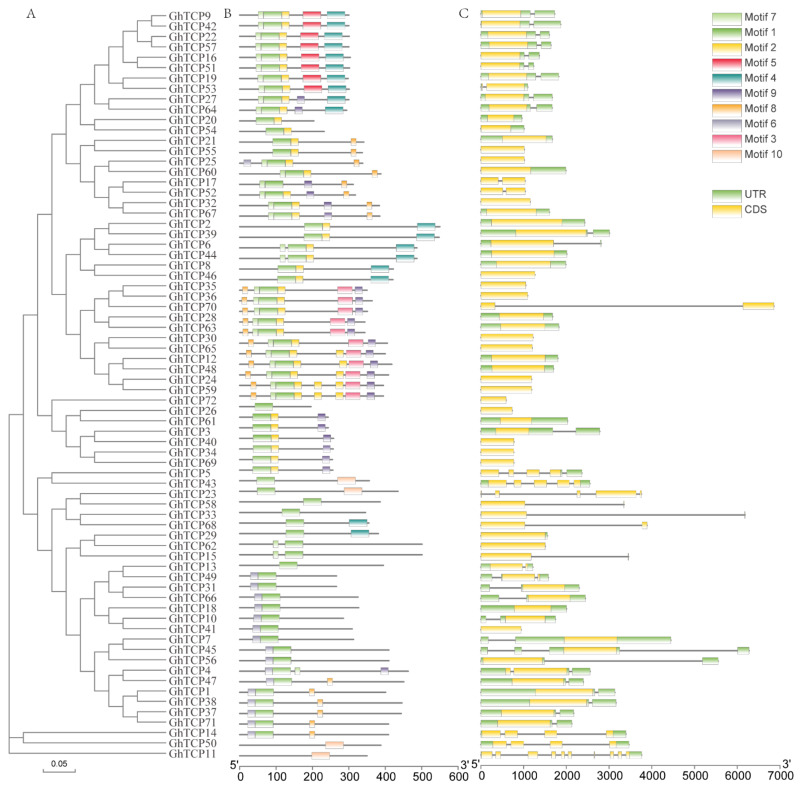

3.3. Gene Structure and Conserved Motifs

To further understand the TCP family genes, we obtained the exon/intron structure of each gene from the genome annotation file (Figure 2C). As a result, we found that 55 out of 72 GhTCP genes have no introns, while the other GhTCP genes typically only have one intron; only three GhTCP genes contain more than three introns. Introns play an important role in the evolution of different plant species, and newly evolved species may possess fewer introns than their ancestors [62]. Most GhTCP family genes contain only one intron, which indicates that the GhTCP gene family could have appeared in early evolutionary stages and subsequently expanded during later stages. Additionally, according to the evolutionary tree and gene structure, most genes in the same subfamily show extremely high similarities in exon length and number of introns (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis, exon-intron organization, and motif compositions of G. hirsutum TCP genes. (A) An evolutionary tree of all TCP transcription factors in G. hirsutum was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method, and bootstrapped tests were performed with 1000 iterations. (B) Identification of conserved protein motifs in the TCP family was performed using the MEME program. Each pattern has a distinctive color. (C) Exon-intron organization of the TCP genes of G. hirsutum (ZM24). The green boxes represent exons and black lines indicate introns.

Next, we performed a conserved motif analysis of the GhTCP proteins using MEME software to observe their diversity of motif composition (Figure 2B). We identified conserved motifs from a total of 10 GhTCP proteins: motifs 1 through 10. Of these, motif 1 is a TCP conserved domain and is found in all GhTCP proteins. Almost all the GhTCP proteins in the same branch of the evolutionary tree possess a similar motif composition, while significant differences can be seen in different branches, indicating that GhTCP members in the same branch could play similar roles and that some motifs could play important roles. However, some motifs only exist in specific branches, indicating that the genes possessing these motifs may perform special functions. In general, the motif composition of most GhTCP proteins and the consistency of the exon/intron structure of GhTCP genes within the phylogenetic subfamilies further indicates that there is a close evolutionary relationship between GhTCP genes and the reliability of systematic analysis.

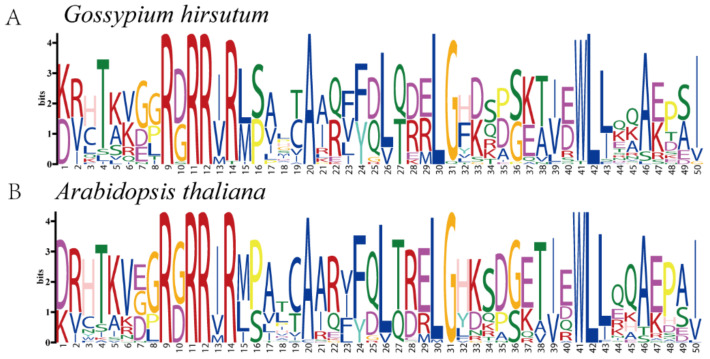

To further explore whether the TCP family of proteins was conserved during evolution, sequence markers were generated for conserved amino acid residues in G. hirsutum and Arabidopsis (Figure 3). Analysis of the conserved amino acid residues demonstrated that the sequence markers between the two species were markedly conserved throughout the sequence. For instance, the amino acid residues T (4), R (9), R (11), R (14), A (20), F (24), L (26), G (31), W (41), L (42), L (43), A (46), and I (50) were highly conserved between Arabidopsis and G. hirsutum. These results suggest that the TCP family in G. hirsutum and Arabidopsis may perform similar functions.

Figure 3.

Sequence logos for conserved amino acid residues in (A) G. hirsutum and (B) Arabidopsis.

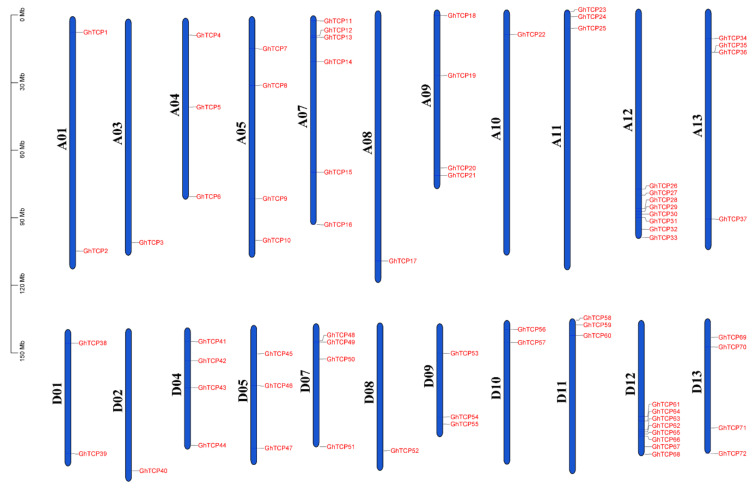

3.4. Chromosomal Distribution and Gene Collinearity Analysis

The genomic annotation file of G. hirsutum (ZM24) was used to determine the chromosomal location of the GhTCP genes and the distribution on the chromosomes of these genes was visualized (Figure 4). All the GhTCP genes were located at 22 of 26 chromosomes. The number of GhTCP genes on each chromosome was not uniformly distributed, ranging from 0 to 8. For instance, chromosome A12/D12 contained the most GhTCP genes, with a total of eight GhTCP genes. However, there no GhTCP gene was found on the A02, D03, A06, or D06 chromosomes.

Figure 4.

Chromosomal distribution of TCP genes of G. hirsutum. The scale is in megabases (Mb). Chromosome numbers are indicated at the left of each chromosome.

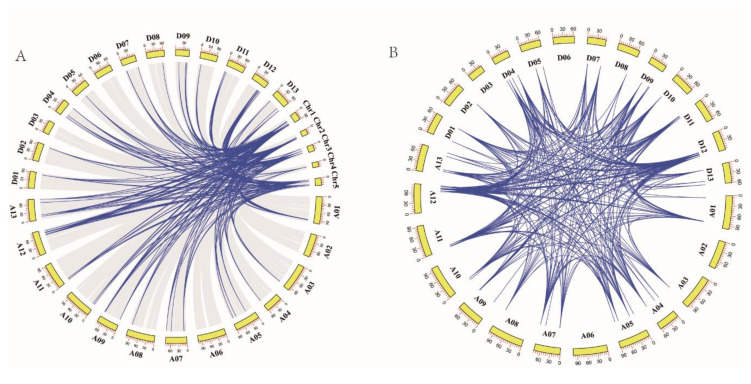

Phylogenetic analysis revealed the existence of a large number of homologous and heterologous gene pairs produced by gene replication. Collinearity analysis between the GhTCP genes and the AtTCP genes demonstrated that there were 323 pairs of orthologous/paralogous TCP genes between G. hirsutum and Arabidopsis and that there were 167 gene pairs between the A subgenome of G. hirsutum and Arabidopsis. Similarly, there were 156 gene pairs between the D subgenome of G. hirsutum and Arabidopsis. Notably, there was fragment duplication between each AtTCP gene and 2–4 GhTCP genes, indicating that fragment duplication events played an important role in TCP gene family expansion during the evolution of G. hirsutum (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Synteny of TCP genes. (A) Synteny analysis of TCP genes between G. hirsutum and Arabidopsis. Colored lines indicate the syntenic regions between G. hirsutum and Arabidopsis chromosomes. (B) Chromosomal distribution and synteny analysis of cotton TCP genes. The chromosomal positions of cotton TCP genes were identified. Colored lines connecting two chromosomal regions indicate the syntenic regions of the cotton genome.

The collinear analysis indicated that there were 537 pairs of homologous TCP genes in G. hirsutum. Specifically, there were 121 gene pairs within the A subgenome of G. hirsutum, 155 gene pairs between the A subgenome and D subgenome of G. hirsutum, 150 gene pairs between the D subgenome and A subgenome of G. hirsutum, and 111 gene pairs in the D genome of G. hirsutum. This indicated that gene replication and fragment duplication were the primary cause of gene family expansion in G. hirsutum (Figure 5B).

3.5. Expression Profiles of TCP Genes in G. hirsutum

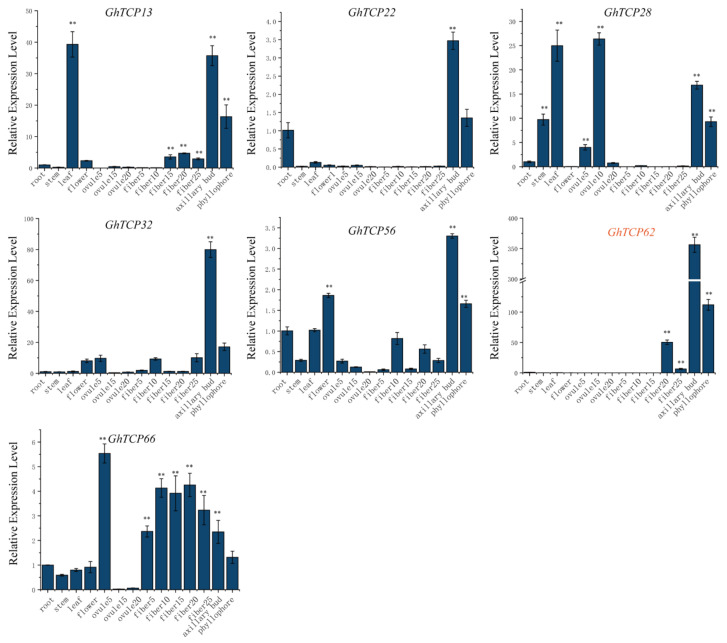

The TYPE2 subfamily AtTCP genes plays an important role in the formation of lateral branches, which determines bud structure [61]. Lateral branches development plays a crucial role in controlling plants, which is related to plant yield and growth. Therefore, we further analyzed TYPE2 GhTCP genes.

The expression pattern of a gene can be used to predict its function. Therefore, we analyzed the tissue-specific expression profile of TYPE2 subfamily GhTCP genes in the root, stem, leaf, flower, ovule, fiber, and other tissues. Our results demonstrated that most GhTCP genes, except for GhTCP66, were highly expressed in the axillary buds and phyllophore. GhTCP62 had the highest and most specific expression in the axillary buds and phyllophores. The GhTCP62 gene belongs to the TB1 subfamily, which regulates the branches of various plant species. This indicates that GhTCP62 could regulate branching in G. hirsutum (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Analysis of tissue-specific gene expression patterns in cotton including root, stem, leaf, flower, fibers and ovules in different stage, axillary bud, and phyllophore. The y-axis represents the expression level of GhTCP genes relative to the reference gene GhUBQ7. The error line represents the standard deviation of three repetitions. The asterisks indicated significant differences compared to root (** p < 0.01 by t-test).

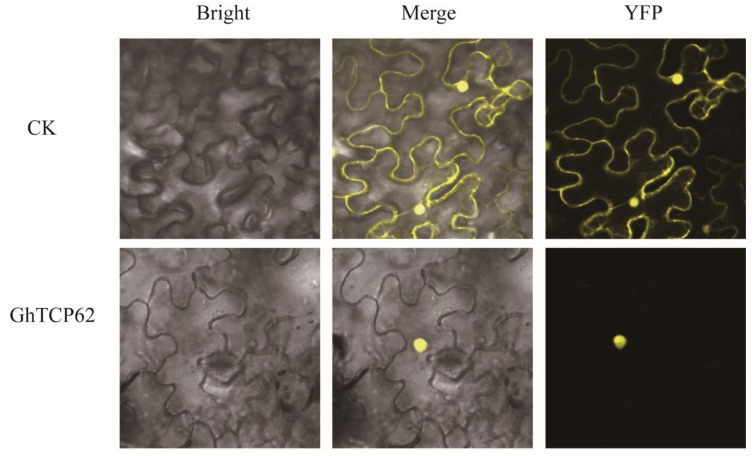

Studies have demonstrated that the localization of the putative nuclear localization signal (KRGK) in the N-terminus of the protein suggests that protein localization occurs in the nucleus [63,64]. We tested the transient expression of GhTCP62 by injecting GhTCP62-YFP into tobacco leaves and found that the GhTCP62 protein was localized in the nucleus (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Subcellular localization of GhTCP62.

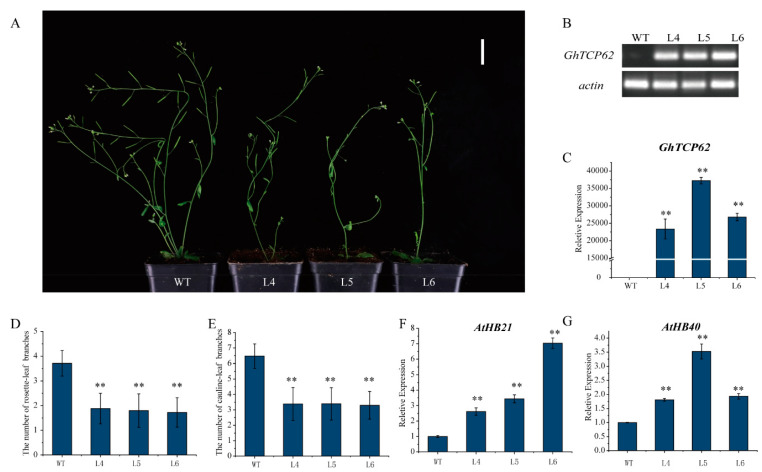

3.6. Overexpression of GhTCP62 in A. thaliana Inhibits Shoot Branching

To verify the function of GhTCP62, Arabidopsis-overexpression (OE) lines were generated using the GhTCP62 gene. Three homozygous lines (L4, L5, L6) were selected for observation and statistical analysis to further analyze the levels of gene expression and shoot branching. These OE lines had fewer rosette-leaf branches and cauline-leaf branches (Figure 8A). Semi-quantitative PCR and RT-qPCR analysis confirmed high GhTCP62 gene expression in overexpression lines compared to WT (Figure 8B,C). The GhTCP62 gene overexpression lines featured fewer cauline-leaf branches and rosette-leaf branches in 35-day-old seedlings compared to the WT (Figure 8A,D,E). The GhTCP62 gene overexpression lines had only one small or dormant rosette-leaf bud compared to the WT, where rosette-leaf buds developed rosette-branches. The GhTCP62 gene overexpression lines featured one or two rosette-leaf branches, while three or four rosette branches were observed in the WT line (Figure 8A,D). Fewer cauline-leaf branches (3) were observed in the OE lines, while six were observed in the WT line in 35-day-old plants (Figure 8A,E). In addition, we also selected the functional deletion mutant brc1-2 to conduct the mutant’s complement experiment, and the results showed that GhTCP62 could complement the phenotype of brc1-2 (Figure S1). These results indicate that GhTCP62 negatively regulates the number and growth vigor of shoot branching.

Figure 8.

Overexpression of GhTCP62 in Arabidopsis reduced the number of branches. (A) Branching phenotypes of 35-day-old WT plants and three overexpressed 35S-GhTCP62 lines. (B) Semi-quantitative PCR and (C) the expression level of GhTCP62 in GhTCP62 overexpressed cell lines was analyzed by qRT-PCR. (D) Quantitative analysis of rosette-leaf branches in 35-day-old WT and GhTCP62 OE lines. (E) Quantitative analysis of cauline-leaf branches in 80-day-old WT and GhTCP62 OE lines. (F) The expression level of AtHB21 in GhTCP62-OE line was analyzed by qRT-PCR. (G) The expression level of AtHB21 in the GhTCP62-OE line was analyzed by qRT-PCR. The error line represents the standard deviation of three repetitions. The asterisks indicated significant differences compared to WT (** p < 0.01 by t-test).

BRC1, a homologous gene of BRC2, directly regulates the bud dormancy genes HB21, HB40, and HB53 in Arabidopsis [65]. In this study, GhBRC1 and GhBRC2 are the homologous genes of Arabidopsis BRC1 and BRC2, respectively. The GhHB21 and GhHB40 found in G. hirsutum indicated that the expression levels of GhHB21 and GhHB40 were positively regulated by GhTCP32 (GhBRC1) [64]. GhTCP62 (GhBRC2) and GhTCP32 (GhBRC2) share high homology, leading us to speculate that GhTCP62 could also regulate bud activity and branching via the GhHB genes. The real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR analysis confirmed high expression levels of HB21 and HB40 genes in the GhTCP62 OE lines (Figure 8F,G). These results indicate that GhTCP62 could regulate bud activity and branching through the GhHB21 and GhHB40 genes in G. hirsutum, which increases ABA levels and inhibits bud activity [66].

4. Discussion

4.1. TCP Gene Plays an Important Role in Plants

TCP transcription factors are a class of plant-specific transcription factors, which play an important and varied role in plant growth and development [57,58], including branching [61,67], regulating leaf development [68], seed germination [69], and regulating the circadian clock [70]. According to the sequence homology of the TCP domain, TCP proteins are divided into two classes: class I and class II [71]. According to sequence differences within the TCP domain, class I can be further subdivided into two clades, CIN and CYC/TB1 [72].

Different types of TCP transcription factors have different functions [57]. Based on mutational studies of multiple members of this subfamily, class II TCP members show inhibited plant growth and cell proliferation [73]. The main function of TB1 genes is regulating axillary bud development and branching [58,67]. Studies have demonstrated that AtTCP12 (BRC2) influences shoot branching [67], and that AtTCP18 (BRC1) controls stem branching and interacts with FLOWERING LOCUS T to repress the floral transition of the axillary meristems [61]. The CIN subclade TCP genes interfere with several different cellular pathways that control leaf development [58]. For instance, in Arabidopsis, four TCP genes (AtTCP3, AtTCP4, AtTCP10, and AtTCP24) involved in the regulation of leaf development were downregulated in the iamt1-D line, resulting in crinkled leaf phenotypes [74]. The Arabidopsis triple mutants (Attcp2, 4, 10-mutants) display epinastic cotyledons and slightly enlarged leaves [75]. Class I (PCF) TCP factors primarily induce cell division and promote plant growth [20]. AtTCP14 activates embryonic growth potential during seed germination, and the AtTCP14 mutant shows delayed germination, indicating a role in the GA regulation of embryo growth during seed germination [69]. Additionally, leaf developmental traits in the mutants of AtTCP8, AtTCP15, AtTCP21, AtTCP22, and AtTCP23 were altered. Transgenic plants expressing AtTCP7SRDX and AtTCP23SRDX indicate their role in cell proliferation [76].

4.2. Gene Replication Events Are the Main Reason for the Expansion of the TCP Gene Family

In this study, we identified 38 GrTCPs in G. raimondii, 36 GaTCPs in G. australe, 72 GbTCPs in G. barbadense, and 72 GhTCPs in G. hirsutum (ZM24), and analyzed their basic information. In previous studies, other researchers identified 73 TCP genes in G. hirsutum (TM-1), which differs from the 72 genes we identified. This result indicates that the TCP family differs among different cotton species. The TCP family gene that we identified in G. hirsutum (ZM24) was twice the size ofthat of G. arboreum, which suggests that G. arboreum is diploid and G. hirsutum (ZM24) is tetraploid. We then analyzed the conserved domain in G. hirsutum, and found that Motif1 was present in almost all family members. Different motifs were often present among family members on different branches of the evolutionary tree. These results demonstrate that Motif1 could be a conserved motif of the TCP family, while other motifs could exist on specific branches of the evolutionary tree, since different TCP genes perform specific functions.

After analyzing the gene structure, we found that most TCP genes only contain one exon, indicating that the TCP gene family could have emerged and expanded in later stages of evolution. Collinearity analysis of the TCP gene family indicated that gene replication events played an important role in the extension of the TCP gene family in cotton. In general, the TCP gene family could have emerged later in its evolutionary history and expanded its family through gene replication.

4.3. GhTCP62 Regulate Shoot Branching in Cotton

Several studies have been conducted to better understand the mechanism of plant branching. These found that many TCPs (TEOSINTE BRANCHED1 (TB1) from maize, Arabidopsis BRC1 and BRC2, and rice, PROLIFERATING CELL FACTOR, were involved in plant branching [64,77]. The ectopic overexpression of OsTB1 significantly reduced lateral branching [78]. Similarly, the overexpression of BRC1 led slowed the growth of the meristem, slowed bud transformation, and reduced the number of branches [79]. BRC1-2 deletion mutants accelerated the development of the meristem, induced rapid bud transformation, and increased the number of branches [67].

BRC2 plays a unique role in the development of axillary buds and shoot branching patterns [61,67]. Pcbrc2-1 knockout lines significantly increased the number of branches compared with the WT [80]. Similarly, BRC2 RNAi and T-DNA insertion lines slightly enhanced bud growth [67]. In this study, RT-qPCR results demonstrated that GhTCP62 was specifically expressed at the base of the stems in upland cotton, indicating that GhTCP62 affected cotton branching. GhTCP62 is located in the nucleus and features typical transcription factor characteristics, and its overexpression in Arabidopsis decreased the number of rosette-leaf branches and cauline-leaf branches. This suggests that GhTCP62 could regulate cotton branches.

4.4. GhTCP62 Regulates Bud Activity and Branching Via HB21 and HB40 Genes

Based on the known upstream gene regulatory network of BRC1 and the downstream target genes of BRC1, some studies have reported the central role of BRC1 in shoot branching [67,81]. BRC1 directly regulates the bud dormancy genes HB21, HB40, and HB53 in Arabidopsis [65]. The BRC1 and HB genes increase ABA levels and inhibit bud activity [66]. Phylogenetic analysis identified the presence of GhHB21 and GhHB40 in cotton, and GhBRC1 positively regulated the expression of these genes [64]. In this study, the expression levels of HB21 and HB40 genes were higher in GhTCP62 overexpression lines than in WT plants. GhTCP32 and GhTCP62 are homologous genes of BRC1 and BRC2, leading us to speculate that GhTCP62 could also regulate branches via the HB gene. This was confirmed by real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR analysis. Along with these results, GhTCP62 could regulate bud activity and branching through the HB21 and HB40 genes, which increase ABA levels and inhibit bud activity [66].

5. Conclusions

TCP transcription factors play important roles in plant growth and development. In this study, 218 TCP genes were identified in four cotton species and were divided into seven subfamilies. We observed similar exon-intron structures and protein motif distribution patterns for GhTCP genes. The GhTCP genes were unevenly distributed on 24 chromosomes, with fragment replication events. GhTCP62 was highly expressed in the cotton axillary buds. Furthermore, the overexpression of GhTCP62 decreased the number of rosette-leaf branches and cauline-leaf branches in Arabidopsis. Moreover, the increased expression of HB21 and HB40 genes in Arabidopsis overexpressing GhTCP62 suggests that GhTCP62 may regulate branching by positively regulating HB21 and HB40.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biology10111104/s1. Figure S1: GhTCP62 complementary brc1-2 phenotype in Arabidopsis. Table S1: Characteristics of AtTCP family genes and the encoded proteins. Table S2: Characteristics of GhTCP family genes and the encoded proteins. Table S3: Primers used in this study.

Author Contributions

G.W., N.Z. and Z.L. conceived and designed the study. J.Y. and Z.L. performed the acquisition of experimental materials, the agronomic survey, and the data analysis. L.L., S.L., G.C., Z.D. conducted part of the primary mapping and the agronomic survey. L.L., G.Q. and Z.L. wrote and improved the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology Open Fund (No. CB2020A02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Barbier F.F., Dun E.A., Beveridge C.A. Apical dominance. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:R864–R865. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kebrom T.H., Chandler P.M., Swain S.M., King R.W., Richards R.A., Spielmeyer W. Inhibition of tiller bud outgrowth in the tin mutant of wheat is associated with precocious internode development. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:308–318. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.197954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng J., Richards D.E., Hartley N.M., Murphy G.P., Devos K.M., Flintham J.E., Beales J., Fish L.J., Worland A.J., Pelica F. ‘Green revolution’genes encode mutant gibberellin response modulators. Nature. 1999;400:256–261. doi: 10.1038/22307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agudamu, Yoshihira T., Shiraiwa T. Branch development responses to planting density and yield stability in soybean cultivars. Plant Prod. Sci. 2016;19:331–339. doi: 10.1080/1343943X.2016.1157443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green-Tracewicz E., Page E.R., Swanton C.J. Shade avoidance in soybean reduces branching and increases plant-to-plant variability in biomass and yield per plant. Weed Sci. 2011;59:43–49. doi: 10.1614/WS-D-10-00081.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jinge T., Chenglong W., Jinliang X., Lishuan W., Guanghui X., Weihao W., Dan L., Wenchao Q., Xu H., Qiuyue C. Teosinte ligule allele narrows plant architecture and enhances high-density maize yields. Science. 2019;365:658–664. doi: 10.1126/science.aax5482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McSteen P., Hake S. barren inflorescence2 regulates axillary meristem development in the maize inflorescence. Development. 2001;128:2881–2891. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.15.2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang B., Smith S.M., Li J. Genetic regulation of shoot architecture. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018;69:437–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knauer S., Javelle M., Li L., Li X., Ma X., Wimalanathan K., Kumari S., Johnston R., Leiboff S., Meeley R. A high-resolution gene expression atlas links dedicated meristem genes to key architectural traits. Genome Res. 2019;29:1962–1973. doi: 10.1101/gr.250878.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo W., Chen L., Herrera-Estrella L., Cao D., Tran L.-S.P. Altering Plant Architecture to Improve Performance and Resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 2020;25:1154–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L., Yang H., Fang Y., Guo W., Chen H., Zhang X., Dai W., Chen S., Hao Q., Yuan S. Overexpression of GmMYB14 improves high-density yield and drought tolerance of soybean through regulating plant architecture mediated by the brassinosteroid pathway. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021;19:702–716. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Q. Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought- and low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1391–1406. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.8.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh D., Debnath P., Roohi, Sane A., Sane V.A. Expression of the tomato WRKY gene, SlWRKY23, alters root sensitivity to ethylene, auxin and JA and affects aerial architecture in transgenic Arabidopsis. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 2020;26:1187. doi: 10.1007/s12298-020-00820-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo D., Zhang J., Wang X., Han X., Wei B., Wang J., Li B., Yu H., Huang Q., Gu H. The WRKY transcription factor WRKY71/EXB1 controls shoot branching by transcriptionally regulating RAX genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015;27:3112–3127. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrara S., Dornelas M.C. TCP genes and the orchestration of plant architecture. Trop. Plant Biol. 2021;14:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12042-020-09274-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lan J., Qin G. The regulation of CIN-like TCP transcription factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:4498. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doebley J., Stec A. teosinte branched1 and the origin of maize: Evidence for epistasis and the evolution of dominance. Genetics. 1995;141:333–346. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.1.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong Z., Wei L., Unger-Wallace E., Yang J., Chuck G. Ideal crop plant architecture is mediated by tassels replace upper ears1, a BTB/POZ ankyrin repeat gene directly targeted by TEOSINTE BRANCHED1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E8656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714960114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakagawa A., Kitazawa M.S., Fujimoto K. A design principle for floral organ number and arrangement in flowers with bilateral symmetry. Development. 2020;147:dev182907. doi: 10.1242/dev.182907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosugi S., Ohashi Y. PCF1 and PCF2 specifically bind to cis elements in the rice proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1607–1619. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selahattin D. TCP Transcription Factors at the Interface between Environmental Challenges and the Plant’s Growth Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1930. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolas M., Cubas P. TCP factors: New kids on the signaling block. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2016;33:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu M.M., Wang M.M., Yang J., Wen J., Du H. Evolutionary and Comparative Expression Analyses of TCP Transcription Factor Gene Family in Land Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3591. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crawford B.C., Nath U., Carpenter R., Coen E.S. CINCINNATA Controls Both Cell Differentiation and Growth in Petal Lobes and Leaves of Antirrhinum. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:244–253. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.036368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danisman S., Dijk A., Bimbo A., Wal F., Immink R. Analysis of functional redundancies within the Arabidopsis TCP transcription factor family. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:5673–5685. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao X., Hong M., Jian W., Zhang D. Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis and Expression Pattern of TCP Gene Families in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2007;49:885–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li F., He X., Zhang Y., Yi Y. Identification and Bioinformatics Analysis of TCP Transcription Factor Family in Tomato. Mol. Plant Breed. 2018;19:847. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding S., Cai Z., Du H., Wang H. Genome-wide analysis of TCP family genes in Zea mays L. identified a role for ZmTCP42 in drought tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2762. doi: 10.3390/ijms20112762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Z.J., Wang W.L., Zhuang J. TCP family genes control leaf development and its responses to hormonal stimuli in tea plant [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze] Plant Growth Regul. 2017;83:43–53. doi: 10.1007/s10725-017-0282-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao G., Kan J., Jiang C., Ahmar S., Zhang J., Yang P. Genome-wide diversity analysis of TCP transcription factors revealed cases of selection from wild to cultivated barley. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2020;21:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s10142-020-00759-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huo Y., Xiong W., Su K., Li Y., Sun Z. Genome-Wide Analysis of the TCP Gene Family in Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) Int. J. Genom. 2019;2019:8514928. doi: 10.1155/2019/8514928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao J., Zhai Z., Li Y., Geng S., Song G., Guan J., Jia M., Wang F., Sun G., Feng N. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of the TCP family genes in spike and grain development of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1282. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarvepalli K., Nath U. Hyper-activation of the TCP4 transcription factor in Arabidopsis thaliana accelerates multiple aspects of plant maturation. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011;67:595–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li D., Zhang H., Mou M., Chen Y., Yu D. Arabidopsis Class II TCP Transcription Factors Integrate with the FT–FD Module to Control Flowering. Plant Physiol. 2019;181:97–111. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang G., Huang J.-Q., Chen X.-Y., Zhu Y.-X. Recent advances and future perspectives in cotton research. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021;72:437–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-080720-113241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng K., Ni Z., Qu Y., Cai Y., Yang Z., Sun G., Chen Q. Genome-wide identification and expression analyses of TCP transcription factor genes in Gossypium barbadense. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:14526. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32626-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin Z., Li Y., Zhu W., Fu X., Han X., Wang J., Lin H., Ye W. Identification, characterization, and expression patterns of tcp genes and microrna319 in cotton. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:3655. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hao J., Tu L., Hu H., Tan J., Deng F., Tang W., Nie Y., Zhang X. GbTCP, a cotton TCP transcription factor, confers fibre elongation and root hair development by a complex regulating system. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:6267–6281. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhan J., Chu Y., Wang Y., Diao Y., Zhao Y., Liu L., Wei X., Meng Y., Li F., Ge X. The miR164-GhCUC2-GhBRC1 module regulates plant architecture through abscisic acid in cotton. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021;19:1839–1851. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang M.-Y., Zhao P.-M., Cheng H.-Q., Han L.-B., Wu X.-M., Gao P., Wang H.-Y., Yang C.-L., Zhong N.-Q., Zuo J.-R. The cotton transcription factor TCP14 functions in auxin-mediated epidermal cell differentiation and elongation. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:1669–1680. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.215673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edgar R C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bailey T.L., Williams N., Misleh C., Li W.W. MEME: Discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W369–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen C., Chen H., Zhang Y., Thomas H.R., Frank M.H., He Y., Xia R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant. 2020;13:1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krzywinski M., Schein J., Birol I., Connors J., Gascoyne R., Horsman D., Jones S.J., Marra M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiong F., Zhuo F., Reiter R.J., Wang L., Wei Z., Deng K., Song Y., Qanmber G., Feng L., Yang Z. Hypocotyl elongation inhibition of melatonin is involved in repressing brassinosteroid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:1082. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Z., Qanmber G., Lu L., Qin W., Liu J., Li J., Ma S., Yang Z., Yang Z. Genome-wide analysis of BES1 genes in Gossypium revealed their evolutionary conserved roles in brassinosteroid signaling. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018;61:1566–1582. doi: 10.1007/s11427-018-9412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li J., Yu D., Qanmber G., Lu L., Wang L., Zheng L., Liu Z., Wu H., Liu X., Chen Q. GhKLCR1, a kinesin light chain-related gene, induces drought-stress sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Sci. China Life Sci. 2019;62:63–75. doi: 10.1007/s11427-018-9307-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang R., Liu L., Kong Z., Li S., Lu L., Chen G., Zhang J., Qanmber G., Liu Z. Identification of GhLOG gene family revealed that GhLOG3 is involved in regulating salinity tolerance in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021;166:328–340. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qanmber G., Liu J., Yu D., Liu Z., Lu L., Mo H., Ma S., Wang Z., Yang Z. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the PERK gene family in Gossypium hirsutum reveals gene duplication and functional divergence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1750. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.QANMBER G., Daoqian Y., Jie L., Lingling W., Shuya M., Lili L., Zuoren Y., Fuguang L. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of Gossypium RING-H2 finger E3 ligase genes revealed their roles in fiber development, and phytohormone and abiotic stress responses. J. Cotton Res. 2018;1:1. doi: 10.1186/s42397-018-0004-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qanmber G., Ali F., Lu L., Mo H., Ma S., Wang Z., Yang Z. Identification of histone H3 (HH3) genes in Gossypium hirsutum revealed diverse expression during ovule development and stress responses. Genes. 2019;10:355. doi: 10.3390/genes10050355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu D., Qanmber G., Lu L., Wang L., Li J., Yang Z., Liu Z., Li Y., Chen Q., Mendu V. Genome-wide analysis of cotton GH3 subfamily II reveals functional divergence in fiber development, hormone response and plant architecture. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:350. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1545-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ali F., Qanmber G., Wei Z., Yu D., Li Y., Gan L., Li F., Wang Z. Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of geranyl geranyl diphosphate synthase genes of cotton (Gossypium spp.) in plant development and abiotic stresses. BMC Genom. 2020;21:561. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-06970-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clough S.J., Bent A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cubas P., Lauter N., Doebley J., Coen E. The TCP domain: A motif found in proteins regulating plant growth and development. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 1999;18:215–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li S. The Arabidopsis thaliana TCP transcription factors: A broadening horizon beyond development. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015;10:e1044192. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2015.1044192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koyama T., Furutani M., Tasaka M., Ohme-Takagi M. TCP transcription factors control the morphology of shoot lateral organs via negative regulation of the expression of boundary-specific genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:473–484. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Efroni I., Blum E., Goldshmidt A., Eshed Y. A protracted and dynamic maturation schedule underlies Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2293–2306. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Niwa M., Daimon Y., Kurotani K., Higo A., Pruneda-Paz J.L., Breton G., Mitsuda N., Kay S.A., Ohme-Takagi M., Endo M., et al. BRANCHED1 interacts with FLOWERING LOCUS T to repress the floral transition of the axillary meristems in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:1228–1242. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.109090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roy S.W., Gilbert W.J.N.R.G. The evolution of spliceosomal introns: Patterns, puzzles and progress. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrg1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dingwall C., Robbins J., Dilworth S.M., Roberts B., Richardson W.D. The nucleoplasmin nuclear location sequence is larger and more complex than that of SV-40 large T antigen. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:841–849. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.3.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diao Y., Zhan J., Zhao Y., Liu L., Liu P., Wei X., Ding Y., Sajjad M., Hu W., Wang P., et al. GhTIE1 Regulates Branching Through Modulating the Transcriptional Activity of TCPs in Cotton and Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:1348. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang Y., Nicolas M., Zhang J., Yu H., Guo D., Yuan R., Zhang T., Yang J., Cubas P., Qin G. The TIE1 transcriptional repressor controls shoot branching by directly repressing BRANCHED1 in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yao C., Finlayson S.A. Abscisic Acid Is a General Negative Regulator of Arabidopsis Axillary Bud Growth. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:611–626. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aguilar-Martínez J.A., Poza-Carrión C., Cubas P. Arabidopsis BRANCHED1 acts as an integrator of branching signals within axillary buds. Plant Cell. 2007;19:458–472. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rubio-Somoza I., Zhou C.M., Confraria A., Martinho C., von Born P., Baena-Gonzalez E., Wang J.W., Weigel D. Temporal control of leaf complexity by miRNA-regulated licensing of protein complexes. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:2714–2719. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tatematsu K., Nakabayashi K., Kamiya Y., Nambara E. Transcription factor AtTCP14 regulates embryonic growth potential during seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008;53:42–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pruneda-Paz J.L., Breton G., Para A., Kay S.A. A functional genomics approach reveals CHE as a component of the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Science. 2009;323:1481–1485. doi: 10.1126/science.1167206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Navaud O., Dabos P., Carnus E., Tremousaygue D., Hervé C. TCP transcription factors predate the emergence of land plants. J. Mol. Evol. 2007;65:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s00239-006-0174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martín-Trillo M., Cubas P. TCP genes: A family snapshot ten years later. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lewis J.M., Mackintosh C.A., Shin S., Gilding E., Kravchenko S., Baldridge G., Zeyen R., Muehlbauer G.J. Overexpression of the maize Teosinte Branched1 gene in wheat suppresses tiller development. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:1217–1225. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qin G., Gu H., Zhao Y., Ma Z., Shi G., Yang Y., Pichersky E., Chen H., Liu M., Chen Z., et al. An indole-3-acetic acid carboxyl methyltransferase regulates Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2693–2704. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schommer C., Palatnik J.F., Aggarwal P., Chételat A., Cubas P., Farmer E.E., Nath U., Weigel D. Control of jasmonate biosynthesis and senescence by miR319 targets. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aguilar-Martínez J.A., Sinha N. Analysis of the role of Arabidopsis class I TCP genes AtTCP7, AtTCP8, AtTCP22, and AtTCP23 in leaf development. Front. Plant Sci. 2013;4:406. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Finlayson S.A., Krishnareddy S.R., Kebrom T.H., Casal J.J. Phytochrome regulation of branching in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:1914–1927. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.148833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Takeda T., Suwa Y., Suzuki M., Kitano H., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Ashikari M., Matsuoka M., Ueguchi C. The OsTB1 gene negatively regulates lateral branching in rice. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003;33:513–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Finlayson S.A. Arabidopsis Teosinte Branched1-like 1 regulates axillary bud outgrowth and is homologous to monocot Teosinte Branched1. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:667–677. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Muhr M., Paulat M., Awwanah M., Brinkkötter M., Teichmann T. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of Populus BRANCHED1 and BRANCHED2 orthologs reveals a major function in bud outgrowth control. Tree Physiol. 2018;38:1588–1597. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpy088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Teichmann T., Muhr M. Shaping plant architecture. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:233. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials.