Abstract

In the present prospective study, five blood tests for detection of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) for detection of early (immediate-early antigen) and late (pp67) mRNA, PCR for detection of HCMV DNA (DNA PCR), culture, and pp65 antigenemia assay, and culture and DNA PCR of urine and throat swab specimens were compared for their abilities to predict the development of disease caused by HCMV (HCMV disease). Of 101 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients with ≤100 CD4+ lymphocytes per mm3, 25 patients developed HCMV disease. The pp65 antigenemia assay (sensitivity, 50%; specificity, 89%) and DNA PCR of blood (sensitivity, 69%; specificity, 75%) were most accurate in predicting the development of HCMV disease within the next 12 months. Both blood culture and late pp67 mRNA NASBA had high specificities (91 and 90%, respectively) but low sensitivities (25 and 13%, respectively). The sensitivities of urine culture, DNA PCR, throat swab specimen culture, DNA PCR, and NASBA of blood for detection of the immediate-early antigen were 73, 87, 53, 67, and 63%, respectively, and the specificities were 58, 46, 76, 60, and 72%, respectively. The positive predictive values of all tests however, were low and did not exceed 50%. In conclusion, virological screening by these qualitative assays for detection of HCMV is of limited value for prediction of the development of HCMV disease in HIV-infected patients.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a common opportunistic pathogen in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and is responsible for serious morbidity, especially retinitis, in 25 to 30% of patients with low CD4 lymphocyte counts (11, 13, 22, 26). Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of disease caused by HCMV (HCMV disease) has declined (17). However, as sustained success of HAART fails for a significant proportion of patients, one might expect patients to continue to be at risk for HCMV disease. The identification of those patients is important, since prophylactic or preemptive therapy with oral ganciclovir or valaciclovir reduces the risk of development of HCMV disease (16, 28). Because of the toxicity and high costs of such treatment for all patients with low CD4 lymphocyte counts, it is important to identify additional risk factors for HCMV disease. HCMV viremia can be detected by PCR for detection of HCMV DNA (DNA PCR) (6, 9, 18, 27, 29), pp65 antigenemia assay (12, 21, 23), and conventional culture or by the more rapid shell vial method. Both DNA PCR and the pp65 antigenemia assay are considered sensitive tests with high predictive values for HCMV disease, especially when large numbers of DNA copies (6, 27, 29) or pp65 antigen-bearing leukocytes (12, 23) are present, while blood cultures for HCMV appear to be of less value (9, 20, 21, 27). Strategies for prophylaxis or preemptive therapy for HCMV disease on the basis of results of quantitative PCR for detection of HCMV DNA have recently been proposed but require further investigation to confirm their benefit in terms of efficacy, convenience, and cost (4, 6, 7, 27, 29).

Although qualitative PCR of blood specimen DNA is a sensitive technique, it does not necessarily correlate with active HCMV infection, since latently present viral DNA or incomplete viral genomes may be amplified (25, 30). The detection of HCMV late mRNA in peripheral blood leukocytes may improve the ability to identify patients at risk for the development of HCMV disease as it directly reflects viral transcriptional activity (1). In a study with bone marrow recipients, detection of HCMV late mRNA by reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR (RT-PCR) was more predictive of the onset of HCMV disease-related symptoms than PCR for detection of HCMV DNA (15). Furthermore, in a study with 102 HIV-infected individuals, detection of late mRNA by RT-PCR was more specific, although it was less sensitive, than DNA PCR for the diagnosis of acute HCMV disease (14). Recently, a method for the detection of mRNA by nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) was developed. In contrast to RT-PCR, NASBA allows direct isothermal amplification of specific sequences of single-stranded RNA (8). Screening for late pp67 mRNA by NASBA proved to be a sensitive technique for the detection of HCMV infection in renal transplant patients and highly predictive of the development of HCMV disease (3).

In the prospective study described here, the prognostic value of monitoring of HCMV mRNA for the immediate-early antigen (IEA) and mRNA for the late pp67 antigen by NASBA for the development of HCMV disease was investigated. The results were compared with those of culture and DNA PCR of blood, urine, and throat swab specimens and a pp65-antigenemia assay with blood from 101 HIV-infected patients considered to be at risk for the development of HCMV disease on the basis of CD4 lymphocyte counts of ≤100/mm3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Between March 1993 and November 1996, HIV-infected patients from the AIDS Clinic of the Slotervaart Hospital in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, with CD4 lymphocyte counts of ≤100/mm3 were asked to participate in this study. All participating patients gave written informed consent. Patients with a history of prior HCMV disease were included, provided that they had not received medication for HCMV disease within 3 months prior to study entry. All participants underwent a complete physical examination, were seen by an ophthalmologist with experience in HIV disease, and had a chest X-ray taken to rule out active HCMV disease at study entry. All patients already had or were offered prophylactic treatment for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and treatment for HIV infection. The treating physicians, including the ophthalmologists, were not informed of the test results for any patient during follow-up.

Diagnosis of HCMV disease.

Patients were considered to have HCMV retinitis if retinal damage typically caused by HCMV was seen upon examination of the retina through a dilated pupil (19). Gastrointestinal disease, including esophagitis, colitis, and cholangitis, was confirmed by endoscopy and histological examination of biopsy specimens with detection of one or more inclusion bodies and/or by immunohistochemical detection of HCMV antigens. Radiculomyelitis was diagnosed on the basis of typical findings upon medical history and physical examination together with detection of HCMV by DNA PCR of cerebrospinal fluid and recovery after treatment for HCMV infection. In addition, other findings that could possibly explain the illness were excluded. HCMV-related adrenalitis was diagnosed whenever the medical history and physical examination were suggestive of adrenal insufficiency, as confirmed by typical laboratory abnormalities and recovery after treatment for HCMV infection.

Collection of samples.

At the start of the study and at each follow-up visit, scheduled every 2 to 3 months, whole blood (10 ml of heparinized blood and 10 ml of EDTA-anticoagulated blood), freshly donated urine, and a throat swab specimen (which was placed in viral culture medium) were collected and were immediately processed for culture, pp65 antigenemia assay, and qualitative DNA PCR.

One milliliter of the whole-blood specimen was added to 9 ml of lysis buffer (4.7 M guanidinium thiocyanate, 46 mM Tris [pH 6.4], 20 mM EDTA, 1.2% [wt/vol] Triton X-100) and was stored at −70°C until assayed for IEA mRNA and late pp67 mRNA by NASBA.

HCMV cultures.

For the detection of infectious HCMV, two conventional cell culture protocols were performed as described below. In brief, the buffy coat of heparinized whole blood was obtained by centrifugation (at 120 × g for 10 min). The leukocytes were then separated by adding 9 ml of 0.85% (wt/vol) NH4Cl (pH 7.4; prepared in house) to the buffy coat and were incubated for 5 min at 4°C to rupture the remaining erythrocytes. After centrifugation (at 400 × g for 5 min) and three washings of the cell pellet with 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the whole leukocyte suspension was resuspended in 3 ml of Earl's HEPES with 10% fetal bovine serum (EH-10%; Life Technology, Paisley, United Kingdom). For the detection of infectious HCMV, human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblasts (provided by the Department of Virology of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) that had been grown for 5 to 10 days in glass tubes and plastic 24-well plates (Costar, Badhoevedorp, The Netherlands) were used. Aliquots of 0.2 ml of the 3-ml leukocyte suspension were inoculated into two tubes and wells (two by two) of the 24-well plate. Inoculated HEL fibroblasts were maintained in EH-2% at 37°C and were observed weekly for a period of 6 weeks for the appearance of cytopathic effects typical of those of replicating HCMV.

In a separate rapid shell vial culture, in duplicate, HCMV-specific antigens were detected 24 to 48 h and 5 to 7 days after inoculation by indirect immunofluorescence staining. Cultures were fixed with methanol-acetone solution (1:1 [vol/vol]) for 20 min at −20°C. Monoclonal antibody E13 (dilution, 1:1,000; Biosoft, Paris, France), which is directed against the HCMV IEA, was added for 60 min at 37°C. Subsequent incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody (dilution, 1:1,000; Biosoft) for 60 min at 37°C yielded fluorescence of the nuclei of infected cells. Cultures were read with a Zeiss fluorescent inverted microscope at ×100 magnification. For the detection of infectious HCMV in urine and throat swab specimens, essentially the same methods described above were used. In brief, urine samples were mixed with EH-10% (1:1 [vol/vol]), whereas throat swab specimens were mixed with a virus transport medium and were subsequently added to HEL fibroblasts as described above.

The blood culture result was considered positive if HCMV was detectable by one or both culture procedures and was negative if HCMV was not detectable by both procedures.

PCR for HCMV DNA detection.

DNA was extracted from patient materials by guanidinium thiocyanate lysis, binding to silica particles, and washing and elution with 100 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer as described by Boom et al. (5). For the blood PCR for HCMV DNA detection, DNA was extracted from 100 μl of whole blood. The PCR was performed with 10 μl of the extracted DNA with primers that are specific for the fourth exon of the immediate-early gene of HCMV (primer 1, 5′-GAGCCTTTCGAGGAGATGAA-3′; primer 2, 5′-GAAGGCTGAGTTCTTGGTAA-3′). After amplification, the PCR products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel and were subsequently transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, Rainham, United Kingdom). The blots were hybridized with a digoxigenin-labelled internal 40-bp probe (5′-CTAACTATGCAGAGCATGTATGAGAACTACATTGTACCTG-3′). Hybrids were visualized with a digoxigenin nucleic acid detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim). With our primers, which were located in the immediate-early gene, the analytic sensitivity of the PCR for HCMV DNA detection was measured to be 20 to 50 DNA molecules.

pp65 antigenemia assay.

The pp65 antigen was detected immunocytochemically, essentially as described by Van der Bij et al. (31), with a few modifications. In brief, the leukocytes were isolated from 10 ml of EDTA-anticoagulated blood by centrifugation as described above within 8 h of collection. The total cell pellet was fixed (10 min at room temperature) in 2% paraformaldehyde (818 715.0100; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). After centrifugation (at 400 × g for 5 min) and three washings of the cell pellet with PBS–1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Boseral 20 T, Organon Teknika, Boxtel, The Netherlands), the whole leukocyte suspension was resuspended in PBS–1% BSA to give a final cell density comparable to that of a McFarland no. 3 standard (2 × 106 leukocytes/ml). A volume of 0.1 ml of the cell suspension was used for each of four cytospin slides. The cytospin slides were stored directly at −70°C until staining. Before staining, the slides (two per patient; one as a control and one for testing) were fixed in cold acetone for 15 min directly from the −70°C freezer. Subsequently, the slides were incubated for 30 min with anti-pp65 monoclonal mouse antibody (C10/C11; dilution, 1:25; Biotest, Dreieich, Germany), and the control samples were incubated with PBS. For immunoenzymatic staining of those cell components to which the mouse anti-pp65 monoclonal antibody specifically binds, the alkaline phosphatase–anti-alkaline phosphatase method was used according to the protocol of the manufacturer (ClonabCMV; Biotest).

The quantification of pp65 antigen-bearing cells was achieved under a light microscope by counting the number of positively stained leukocytes and the total number of leukocytes per slide by using an eyepiece with a counting grid. The results were given as the total number of positive leukocytes/total number of leukocytes × 105, which is equal to the number of positive leukocytes/105 leukocytes.

NASBA for IEA mRNA and pp67 mRNA.

For the analysis by NASBA, 1 ml of the lysed whole-blood suspension, which equals 100 μl of the whole-blood input sample at 100:1, was used. Processing of blood specimens for isolation of HCMV IEA and late (pp67) mRNA and monitoring of the expression of these mRNAs by NASBA (Organon Teknika) were done as recently described by Blok et al. (2, 3). The primers CMV IEA-1.5 (T7 primer [sequence, 5′-aattctaatacgactcactatagggagaCTTAATACAAGCCATCCACA-3′; the T7 promoter sequence is depicted in small capital letter]) and CMV 2.3 (primer 2; sequence, 5′-TAGATAAGGTTCATGAGCCT-3′) were designed to amplify part of the mRNA encoding IEA. For the amplification of part of the mRNA encoding pp67, primers CMVpp67-1.2 and CMVpp67-2.4, which have been described before (3), were used. The NASBA reactions were carried out as described by Blok et al. (3). After the NASBA reaction, the amplification products were analyzed by an enzyme-linked gel assay, as described by Van der Vliet et al. (32), with the use of a specific horseradish peroxidase 5′-labelled oligonucleotide probe (CMV IEA HRP1; sequence, 5′-HRP-GAGGATAAGCGGGAGATGTGGATGGC-3′) for NASBA of IEA mRNA. Electrochemiluminescence-based detection was used for the NASBA of pp67 mRNA (3). The analytical sensitivities of the NASBAs for IEA mRNA and pp67 mRNA detection were about 10 to 100 RNA molecules.

Statistical analysis.

For each test the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were determined, by using standard formulas, by comparing the test results for patients who developed HCMV disease with those for patients who did not. Relative risks and likelihood ratios (sensitivity/1 − specificity) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Initially, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, relative risk, and likelihood ratio for the development of HCMV disease within 12 months were determined for each test on the basis of the first available test result for all patients. As the pp65 antigenemia assay provides a quantitative result, the cutoff value for a positive pp65 antigenemia test result was determined by constructing a receiver-operating characteristic curve. By using such an analysis, the cutoff value with the highest combination of sensitivity and specificity can be distinguished. The value of repeat testing for the identification of patients who develop HCMV disease was determined by dividing the patients into those who had never had a positive test result and those with a positive test result on at least one occasion during follow-up. Relative risk, likelihood ratio, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were again determined for each test.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population.

A total of 116 patients entered the study. Of these patients, 15 were excluded from further analysis; 1 had received maintenance treatment for HCMV-related meningoencephalitis within 3 months prior to study entry and 14 were diagnosed with HCMV disease at the time of inclusion.

The demographic characteristics of the remaining 101 patients are shown in Table 1. Ten patients (9.9%) were HCMV immunoglobulin G antibody negative. None of these patients had received HCMV treatment at any time prior to study entry, and no patient had a history of previous HCMV disease. Two patients were on HAART at the time of study entry, and another two started HAART at the time of study entry. The other 97 patients used one or a combination of nucleoside analogue RT inhibitors or no antiretroviral therapy at all.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 101 |

| Sex (no. of patients) | |

| Male | 93 |

| Female | 8 |

| Median age (yr [IQR]) | 38 (32–42) |

| Median CD4 lymphocyte count (no. of cells/mm3 [IQR]) | 40 (20–70) |

| HIV transmission category (no. of patients) | |

| Homosexual sexual activity | 71 |

| Intravenous drug abuse | 15 |

| Heterosexual sexual activity | 9 |

| Blood transfusion | 3 |

| Unknown | 3 |

| Previous AIDS-indicating conditions (no. of patients)a | 79 |

| Candidiasis of the esophagus | 21 |

| Cryptococcosis | 3 |

| Cryptosporidiosis | 3 |

| HIV-associated dementia | 2 |

| HIV-associated wasting | 1 |

| Kaposi's sarcoma | 23 |

| Lymphoma, B-cell, non-Hodgkin's | 3 |

| Mycobacterium avium-M. kansasii infection | 8 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis pulmonary | 2 |

| P. carinii pneumonia | 33 |

| Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | 1 |

| Cerebral toxoplasmosis | 6 |

More than one diagnosis was possible per patient.

Development of HCMV disease.

The median follow-up time for the patients was 15.2 months (interquartile range [IQR], 10.1 to 23.8 months). Of the 101 patients, 25 developed HCMV disease during follow-up: retinitis (n = 17), colitis (n = 4), esophagitis (n = 1), cholangitis (n = 1), adrenalitis (n = 1), and radiculomyelitis (n = 1). The median time to the development of HCMV disease was 10.6 months (IQR, 8.8 to 16.0 months). The patients who were HCMV immunoglobulin G antibody negative and the four patients on HAART remained free of HCMV disease during follow-up. Seventy-two patients died after a median follow-up of 12.9 months (IQR, 9.5 to 19.3 months), and four patients were lost to follow-up. Eighteen of these 72 patients had developed HCMV disease and died a median of 4.1 months (IQR, 2.6 to 8.0 months) after the diagnosis of HCMV disease. Since most patients died at home and postmortem examinations were not routinely performed, some patients may have had clinically unrecognized HCMV disease. However, in only one of the five patients who did undergo a postmortem examination and who had not developed HCMV disease during his life, a duodenal ulcer was found, and this was possibly caused by HCMV. This patient also suffered from visceral Kaposi's sarcoma and a non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, the combination of which was thought to have been the cause of death.

PPVs, NPVs, and relative risk for the development of HCMV disease over the next 12 months by testing a single sample.

Calculations of the predictive value of each assay for the development of HCMV disease over the next 12 months were based on results of a sample taken at the start of the study. Of the 25 patients who developed HCMV disease, 16 developed HCMV disease within 1 year after study entry. As the pp65 antigenemia assay result was quantified as numbers of positive leukocytes per 105 leukocytes counted, a cutoff level of 6 positive leukocytes/105 leukocytes was determined by using a receiver-operating characteristic curve; a result above the cutoff was given a positive score. The test results for patients who did and who did not develop HCMV disease over the next 12 months are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Test results for a single sample taken at start of study from 101 patients

| Test and result | No. of patients who developed HCMV disease within 1 yr (n = 16) (sensitivity [%]) | No. of patients who did not develop HCMV disease within 1 yr (n = 85) (specificity [%]) | Likelihood ratioa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NASBA for IEA mRNA detection | |||

| Positive | 10 (63) | 24 | 2.2 (1.3–3.7) |

| Negative | 6 | 61 (72) | |

| DNA PCR with blood | |||

| Positive | 11 (69) | 21 | 2.8 (1.7–4.6) |

| Negative | 5 | 64 (75) | |

| pp65 antigenemia | |||

| Positive | 8 (50) | 9b | 4.6 (2.1–10.9) |

| Negative | 8 | 73 (89) | |

| NASBA for pp67 mRNA detection | |||

| Positive | 4 (25) | 8c | 2.6 (0.9–7.7) |

| Negative | 12 | 76 (90) | |

| Blood culture | |||

| Positive | 2d (13) | 8 | 1.4 (0.3–6.0) |

| Negative | 13 | 77 (91) | |

| Urine culture | |||

| Positive | 11d (73) | 35c | 1.8 (1.2–2.6) |

| Negative | 4 | 49 (58) | |

| DNA PCR with urine | |||

| Positive | 13d (87) | 45c | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) |

| Negative | 2 | 39 (46) | |

| Throat swab specimen culture | |||

| Positive | 8d (53) | 20 | 2.2 (1.2–4.1) |

| Negative | 7 | 64c (76) | |

| DNA PCR with throat swab specimen | |||

| Positive | 10d (67) | 34 | 1.6 (1.1–2.6) |

| Negative | 5 | 50c (60) |

The likelihood ratio was determined as a combined measure of sensitivity and specificity: likelihood ratio = sensitivity/1 − specificity.

For three patients who did not develop HCMV disease, no result of the pp65 antigenemia assay was available.

For one patient who did not develop HCMV disease, no test result was available.

For one patient who developed HCMV disease, no test result was available.

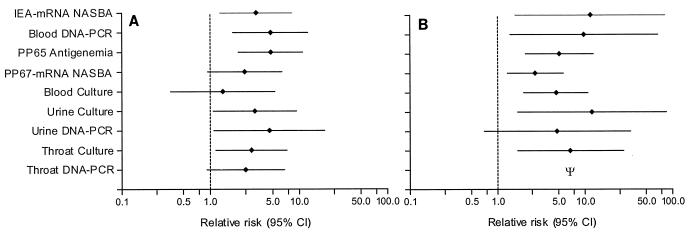

DNA PCR and culture of urine had the highest sensitivities (87 and 73%, respectively), but the specificities of these tests were low. Blood culture and NASBA for pp67 mRNA were not very sensitive but had higher specificities (91 and 90%, respectively). The sensitivities of the NASBA for IEA mRNA detection (63%), DNA PCR with blood (69%), and DNA PCR with throat swab specimens (67%) were comparable, but the specificity of the DNA PCR with throat swab specimens was lower than the specificity of the NASBA for IEA mRNA detection and DNA PCR with blood. The combined value of sensitivity and specificity favored the pp65 antigenemia assay, with a likelihood ratio of 4.6 (95% CI, 2.1 to 10.9). The PPV for the development of HCMV disease over the next 12 months was low for all assays and did not exceed 50%. The PPV was highest for the pp65 antigenemia assay (47%) and the DNA PCR with blood (35%). The NPV, on the other hand, was fairly high for all tests, ranging from 86% (blood culture) to 95% (DNA PCR with urine). Thus, patients with no detectable HCMV by any test were unlikely to develop HCMV disease in the near future. The NPV of the pp65 antigenemia assay was slightly lower than the NPV of the DNA PCR with blood (90 versus 93%). The combined value of PPV and NPV (relative risk) favored the pp65 antigenemia assay and qualitative DNA PCR with blood (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

(A) Relative risk for the development of HCMV disease within the next 12 months after a single positive test result for a sample taken at the start of the study. (B) Relative risk for the development of HCMV disease after at least one positive test result for samples taken during follow-up. Ψ, infinite relative risk as NPV was 100%.

Repeat testing for prediction of HCMV disease.

The median number of follow-up samples per patient-year of follow-up was 6.4 (IQR, 4.9 to 8.0) among patients who developed HCMV disease and 5.9 (IQR, 4.8 to 7.0) among patients who did not develop HCMV disease (P = 0.34 by the Wilcoxon two-sample test).

For many patients who initially had negative test results at the start of the study, HCMV became detectable on at least one occasion during follow-up, regardless of the development of HCMV disease (Table 3). Although an increase in the sensitivity of each test for the detection of HCMV disease was observed by repeat testing, the specificity of each test decreased. The pp65 antigenemia assay and blood culture had the highest likelihood ratios (2.5 and 2.7, respectively), mainly because these tests were more specific, while they were less sensitive than DNA PCR with blood, NASBA for IEA mRNA detection, and both culture and DNA PCR with urine and throat swab specimens at detecting HCMV disease. During follow-up, a positive result of each test except the DNA PCR with urine was significantly associated with the development of HCMV disease (Fig. 1B), with culture of urine having the highest relative risk for the development of HCMV disease (12.0; 95% CI, 1.7 to 85.3). However, upon repeat testing the PPV of a positive test result during follow-up for the subsequent development of HCMV disease was still less than 50% for all tests.

TABLE 3.

Test results for 101 patients during follow-up

| Test and resulta | No. of patients who developed HCMV disease (n = 25) (sensitivity [%]) | No. of patients who did not develop HCMV disease (n = 76) (specificity [%]) | Likelihood ratiob (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NASBA for IEA mRNA detection | |||

| Positive | 24 (96) | 44 | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) |

| Negative | 1 | 32 (42) | |

| DNA PCR with blood | |||

| Positive | 24 (96) | 48 | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) |

| Negative | 1 | 28 (37) | |

| pp65 antigenemia | |||

| Positive | 20 (80) | 23c | 2.5 (1.7–3.8) |

| Negative | 5 | 50 (68) | |

| NASBA for pp67 mRNA detection | |||

| Positive | 17 (68) | 27d | 1.9 (1.3–2.8) |

| Negative | 8 | 48 (64) | |

| Blood culture | |||

| Positive | 18e (75) | 21 | 2.7 (1.8–4.2) |

| Negative | 6 | 55 (72) | |

| Urine culture | |||

| Positive | 23e (96) | 42d | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) |

| Negative | 1 | 33 (44) | |

| DNA PCR with urine | |||

| Positive | 23e (96) | 59d | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) |

| Negative | 1 | 16 (21) | |

| Throat swab specimen culture | |||

| Positive | 22e (92) | 39 | 1.8 (1.4–2.3) |

| Negative | 2 | 36d (48) | |

| DNA PCR with throat swab specimen | |||

| Positive | 24e (100) | 58 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| Negative | 0 | 17d (23) |

For each test, patients who had at least one positive test result during follow-up are considered positive and patients who had persistently negative test results are considered negative.

The likelihood ratio was determined as a combined measure of sensitivity and specificity: likelihood ratio = sensitivity/1 − specificity.

For three patients who did not develop HCMV disease, no result of the pp65 antigenemia assay was available.

For one patient who did not develop HCMV disease, no test result was available.

For one patient who developed HCMV disease, no test result was available.

Test results during follow-up for patients who developed HCMV disease.

For 20 of the 25 patients who developed HCMV disease, samples were drawn at the time of diagnosis of HCMV disease. Not all patients who tested positive at least once during follow-up were also positive at the time of diagnosis of HCMV disease. NASBA for detection of IEA mRNA was positive for 16 of 20 patients (80%). DNA PCR with blood was positive for 15 of 20 patients (75%). The pp65 antigenemia assay was positive for 10 of 18 patients (55.6%), while for 2 patients no test results were available due to the availability of an insufficient number of leukocytes after sample preparation. Blood culture was positive for 10 of 19 patients (52.6%); for 1 patient no test result was available. The NASBA assay for detection of pp67 mRNA was positive for 11 of 20 patients (55%). The urine culture was positive for 16 of 18 patients (88.9%), and the DNA PCR with urine was positive for 15 of 18 patients (83.3%), while no urine samples were taken from 2 patients. The throat swab culture was positive for 15 of 19 patients (78.9%), and the DNA PCR with throat swab specimens was positive for 17 of 19 patients (89.5%). No throat swab was taken from one patient.

The time between the first positive test result and the development of HCMV disease differed considerably between the assays. At a median of 4.5 months (IQR, 3.2 to 8.5 months), 3.1 months (IQR, 1.9 to 6.6 months), and 4.7 months (IQR, 2.1 to 9.2 months) before the development of HCMV disease, the NASBA for pp67 mRNA detection, blood culture, and pp65 antigenemia assay, respectively, became positive. The other assays became positive much earlier before diagnosis of HCMV disease: NASBA for IEA mRNA detection, 9.2 months (IQR, 4.1 to 11.3 months); DNA PCR with blood, 9.4 months (IQR, 4.6 to 12.8 months); urine culture, 9.2 months (IQR, 3.6 to 18.4 months); DNA PCR with urine, 9.7 months (IQR, 6.7 to 18.4 months); culture of throat swab specimen, 8.8 months (IQR, 4.4 to 13.2 months); and DNA PCR with throat swab specimen, 9.1 months (IQR, 5.5 to 15.0 months).

However, after testing positive before the development of HCMV disease, a considerable number of patients again had negative test results during further follow-up. For the NASBA for IEA mRNA detection this was observed for 10 of 20 patients (50%), for DNA PCR with blood this was observed for 11 of 20 patients (52.4%), for the pp65 antigenemia assay this was observed for 8 of 18 patients (44.4%), for the NASBA for detection of pp67 mRNA this was observed for 9 of 20 patients (45%), for blood culture this was observed for 8 of 20 patients (40%), for urine culture this was observed for 7 of 18 patients (38.9%), for DNA PCR with urine this was observed for 12 of 18 patients (66.7%), for culture of throat swab this was observed for 8 of 19 patients (42.1%), and for DNA PCR with throat swab specimens this was observed for 6 of 19 patients (31.6%).

DISCUSSION

In the prospective study described here five different blood tests, including detection of early and late mRNAs by NASBA and two tests with urine and throat swab specimens for the detection of HCMV, were compared to establish the most accurate test for the identification of HIV-infected patients who will go on to develop HCMV disease. So far, other studies that have evaluated a limited number of available tests for the detection of HCMV have shown that, in particular, the pp65 antigenemia assay and DNA PCR with blood or plasma may identify patients who will develop HCMV disease, while culture of blood and urine appeared to be of less value (9, 18, 21, 24, 27, 29).

For patient management, assays accurate in predicting the development of HCMV disease may contribute to the decision to start prophylactic or preemptive treatment against HCMV in individual patients. We therefore assessed the value of a single test result as well as the results of repeat tests for the identification of patients who will develop HCMV disease. On the basis of a single test result, the pp65 antigenemia assay and DNA PCR with blood were highly associated with the development of HCMV disease within 1 year, whereas the results of a single test by conventional blood culture, a NASBA assay for pp67 mRNA detection, and DNA PCR with throat swab specimens were not. The DNA PCR with blood was more sensitive than the pp65 antigenemia assay, but the pp65 antigenemia assay was more specific and had a higher PPV for the development of HCMV disease. By using the likelihood ratio, the probability of a positive test result while getting the disease can be related to the probability of a positive test result while not getting HCMV disease. The pp65 antigenemia assay had a higher likelihood ratio than the DNA PCR with blood. When multivariate logistic regression analysis was used, including data for all tests with a positive or negative result, the only remaining test with a significant relative risk for the development of HCMV disease was the pp65 antigenemia assay (data not shown).

It has been reported that quantification of the HCMV load may improve the ability to identify patients who will develop HCMV disease (4, 12, 24, 27, 29). The pp65 antigenemia assay, in contrast to the other tests used in this study, allows an indirect quantification of HCMV load by counting the number of antigen-bearing cells. A threshold level of six antigen-positive cells was used to assign a positive result. This may explain why the antigenemia assay was more predictive of the development of HCMV disease than the DNA PCR. Still, however, it should be stressed that the predictive value of the pp65 antigenemia assay was low, since less than 50% of the patients with a positive test result went on to develop HCMV disease.

The detection of late pp67 mRNA by NASBA in a single sample was not associated with the development of HCMV disease in the near future. Although this test was highly specific, it had a low sensitivity and a low PPV for the development of HCMV disease. This is in contrast to the findings for a group of renal transplant patients, for whom the detection of late mRNA by NASBA was highly predictive and specific for the onset of HCMV disease (3). Gozlan et al. (14), who earlier described an indirect method for the detection of HCMV late mRNA by RT-PCR, found it to be a highly specific and only a slightly less sensitive marker than the pp65 antigenemia assay and DNA PCR with blood for the diagnosis of HCMV disease in HIV-infected patients. However, no data on its value in predicting HCMV disease are available.

DNA PCR with urine, culture of urine, DNA PCR with throat swab specimens, and culture of throat swab specimens were all highly sensitive tests for the identification of patients who will go on to develop HCMV disease, but their specificities were low. This suggests that many HIV-infected patients with low CD4 lymphocyte counts may at times shed HCMV in urine or the throat without subsequently developing HCMV disease. Repeat testing during follow-up increased the sensitivity of each test for the identification of patients who will develop HCMV disease. However, an increasing number of patients who did not develop HCMV disease also had positive test results during follow-up. Overall, each test (except DNA PCR with urine), when positive at least once during follow-up, was significantly associated with the development of HCMV disease, but again, the PPVs of these tests did not exceed 50%. The observation that for each test approximately 50% of the patients who developed HCMV disease had negative test results after a positive test result further attenuates the relevance of repeat testing.

For most patients, HCMV was already detectable by the different assays months before HCMV disease developed. In addition, some patients had negative test results at the time of diagnosis of HCMV disease after they had been positive on an earlier occasion. This confirms the findings of Shinkai et al. (27), who demonstrated that peak HCMV DNA levels occurred months before the development of HCMV disease in some patients, while at the time of diagnosis of HCMV disease few or no DNA copies were found. Therefore, one may speculate that viral seeding of an organ takes place months before HCMV disease develops. Ultimately, local host defense mechanisms determine to what extent clinical symptoms develop. Two observations may support this concept. First, it was shown that in 91% of patients with HCMV retinitis, DNA PCR with ocular fluid was positive, while only 44% of these patients had positive results by DNA PCR with blood (10). Second, patients with HCMV retinitis may develop a transient intraocular inflammation after the institution of combination antiretroviral therapy, possibly reflecting an improved immune response against HCMV (33). Therefore, the finding of HCMV in other clinical specimens like blood, urine, and throat swabs may not accurately reflect disease progression in an organ where the virus ultimately resides.

HCMV disease is most likely to develop in patients with less than 50 CD4 lymphocytes/mm3. This study also included patients with 50 to 100 CD4 lymphocytes/mm3. However, a subanalysis that included the test results for only 66 patients with 50 CD4 lymphocytes/mm3 or less essentially revealed identical sensitivities, specificities, and relative risks for the development of HCMV disease for each assay.

In summary, the results indicate that, if any of the tests are useful, the pp65 antigenemia assay and DNA PCR with blood are the most useful tests for the identification of those patients who will develop HCMV disease over time. However, when considering the result of a single test by DNA PCR with blood or the pp65 antigenemia assay, only 60 to 70% of patients with HCMV disease will be accurately identified and less than half of the patients who test positive will actually develop HCMV disease in the near future. Furthermore, many patients with a negative test result will still develop HCMV disease. These results indicate that screening for HCMV in HIV-infected patients by any of the reported qualitative assays is of limited value for the management of HCMV disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Hanneke Paap and Lillian van Belle, AIDS nurses of the Slotervaart Hospital, Amsterdam, for their efforts in patient recruitment and provision of clinical samples and data and Joeri Vrooland and Francis Neuteboom for providing ophthalmologic data. We also thank Anneke Stouten and Loes Buisman of the Department of Microbiology of the Slotervaart Hospital for the provision of virological and serological data. We gratefully thank Organon Teknika for technical support and provision of NASBA assays for detection of early and late HCMV mRNA. This work was performed at the Slotervaart Hospital, and at the National AIDS Therapy Evaluation Center, Department of Internal Medicine, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bitsch A, Kirchner H, Dupke R, Bein G. Cytomegalovirus transcripts in peripheral blood leukocytes of actively infected transplant patients detected by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:740–743. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blok M J, Christiaans M H, Goossens V J, van Hooff J P, Top B, Middeldorp J M, Bruggeman C A. Evaluation of a new method for early detection of active cytomegalovirus infections. A study in kidney transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 1998;11(Suppl. 1):S107–S109. doi: 10.1007/s001470050439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blok M J, Goossens V J, Vanherle S J V, Top B, Tacken N, Middeldorp J M, Christiaans M H, van Hooff J P, Bruggeman C A. Diagnostic value of monitoring human cytomegalovirus late pp67 mRNA expression in renal allograft recipients by nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1341–1346. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1341-1346.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boivin G, Handfield J, Toma E, Murray G, Lalonde R, Bergeron M G. Comparative evaluation of the cytomegalovirus DNA load in polymorphonuclear leukocytes and plasma of human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:355–360. doi: 10.1086/514190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boom R, Sol C J, Salimans M M M, Jansen C L, Wertheim-van Dillen P M, van der Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen E F, Sabin C A, Wilson P, et al. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) viraemia detected by polymerase chain reaction identifies a group of HIV-positive patients at high risk of CMV disease. AIDS. 1997;11:889–893. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowen E F, Wilson P, Cope A, et al. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in AIDS patients: influence of cytomegaloviral load on response to ganciclovir, time to recurrence and survival. AIDS. 1996;10:1515–1520. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compton J. Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. Nature. 1991;350:91–92. doi: 10.1038/350091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodt K K, Jacobsen P H, Hofmann B, et al. Development of cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease may be predicted in HIV-infected patients by CMV polymerase chain reaction and the antigenemia test. AIDS. 1997;11:F21–F28. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199703110-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doorenbal P, Seerp Baarsma G, Quint W G V, Kijlstra A, Rothbarth P H, Niesters H G M. Diagnostic assays in cytomegalovirus retinitis: detection of herpesvirus by simultaneous application of the polymerase chain reaction and local antibody analysis on ocular fluid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:235–240. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drew W L. Cytomegalovirus infection in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:608–615. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.2.608-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francisci D, Tosti A, Baldelli F, Stagni G, Pauluzzi S. The pp65 antigenemia test as a predictor of cytomegalovirus-induced end-organ disease in patients with AIDS. AIDS. 1997;11:1341–1345. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallant J E, Moore R D, Richman D D, Keruly J, Chaisson R E The Zidovudine Epidemiology Study Group. Incidence and natural history of cytomegalovirus disease in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease treated with zidovudine. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1223–1227. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gozlan J, Salord J M, Chouaïd C, Duvivier C, Picard O, Meyohas M C, Petit J C. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) late-mRNA detection in peripheral blood of AIDS patients: diagnostic value for HCMV disease compared with those of viral culture and HCMV DNA detection. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1943–1945. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1943-1945.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gozlan J, Laporte J P, Lesage S, Labopin M, Najman A, Gorin N C, Petit J C. Monitoring of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in bone marrow recipients by reverse transcription-PCR and comparison with PCR and blood and urine cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2085–2088. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2085-2088.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffiths P D, Feinberg J E, Fry J, et al. The effect of valaciclovir on cytomegalovirus viremia and viruria detected by polymerase chain reaction in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:57–64. doi: 10.1086/513806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammer S M, Squires K E, Hughes M D, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen K K, Ricksten A, Hofmann B, Norrild B, Olofsson S, Mathiesen L. Detection of cytomegalovirus DNA in serum correlates with clinical cytomegalovirus retinitis in AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1271–1274. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.5.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ljungman P, Plotkin S A. Workshop on CMV disease: definition, clinical severity scores and new syndromes. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;99:87–89. [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacGregor R R, Pakola S J, Graziani A L, et al. Evidence of active cytomegalovirus infection in clinically stable HIV-infected individuals with CD4+ lymphocyte counts below 100/μl of blood: features and relation to risk of subsequent CMV retinitis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10:324–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazzulli T, Rubin R H, Ferraro M J, D'Aquila R T, Doveikis S A, Smith B R, The T H, Hirsch M S. Cytomegalovirus antigenemia: clinical correlations in transplant recipients and in persons with AIDS. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2824–2827. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2824-2827.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pertel P, Hirschtick R, Phair J, Chmiel J, Poggensee L, Murphy R. Risk of developing cytomegalovirus retinitis in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1992;5:1069–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Podzamcer D, Ferrer E, Garcia A, et al. PP65 antigenemia as a marker of future CMV disease and mortality in HIV-infected patients. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29:223–227. doi: 10.3109/00365549709019032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasmussen L, Morris S, Zipeto D, et al. Quantitation of human cytomegalovirus DNA from peripheral blood cells of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients could predict cytomegalovirus retinitis. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:177–182. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roseff S D, Rockis M, Keiser J F, et al. Optimization for detection of cytomegalovirus by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in clinical samples. J Virol Methods. 1993;42:137–146. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90027-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saillour F, Bernard N, Dequae-Merchadou L, et al. Predictive factors of occurrence of cytomegalovirus disease and impact on survival in the Aquitaine cohort in France, 1985 to 1994. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;17:171–178. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199802010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinkai M, Bozette S A, Powderly W, Frame P, Spector S A. Utility of urine and leukocyte cultures and plasma DNA polymerase chain reaction for identification of AIDS patients at risk for developing human cytomegalovirus disease. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:302–308. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spector S A, McKinley G F, Lalezari J P, et al. Oral ganciclovir for the prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in persons with AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1491–1497. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606063342302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spector S A, Wong R, Hsia K, Pilcher M, Stempien M J. Plasma cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA load predicts CMV disease and survival in AIDS patients. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:497–502. doi: 10.1172/JCI1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The T, van der Ploeg M, van den Berg A P, Vlieger A M, van der Giessen M, van Son W J. Direct detection of cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood leukocytes—a review of the antigenemia assay and polymerase chain reaction. Transplantation. 1992;54:193–198. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van der Bij W, Torensma R, van Son W J, et al. Rapid immunodiagnosis of active cytomegalovirus infection by monoclonal antibody staining of blood leukocytes. J Med Virol. 1988;25:179–188. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890250208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van der Vliet G M E, Schukkink R A F, van Gemen B, Schepers P, Klatser P R. Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) for the identification of mycobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2423–2429. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-10-2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zegans M E, Walton R C, Holland G N, O'Donnell J J, Jacobson M A, Margolis T P. Transient vitreous inflammatory reactions associated with combination antiretroviral therapy in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:292–300. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]