Abstract

In platelets, oxidative stress reportedly increases platelet adhesion to vessels, thus promoting the vascular pathology of various neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Recently, it has been shown that β-amyloid (Aβ) can increase oxidative stress in platelets; however, the underlying mechanism remains elusive. In the present study, we aimed to elucidate the signaling pathway of platelet adhesion induced by Aβ1–40, the major form of circulating Aβ, through Western blotting, immunofluorescence confocal microscopy, and fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. Additionally, we examined whether rosmarinic acid (RA), a natural polyphenol antioxidant, can modulate these processes. Our results show that Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion is mediated through NADPH oxidase/ROS/PKC-δ/integrin αIIbβ3 signaling, and these signaling pathways are significantly inhibited by RA. Collectively, these results suggest that RA may have beneficial effects on platelet-associated vascular pathology in AD.

Keywords: platelet, rosmarinic acid (RA), β-amyloid (Aβ), NADPH oxidase, integrin αIIbβ3

1. Introduction

Accumulating evidence suggests a correlation between vascular pathology and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1,2]. In numerous neuropathological studies, more than one-third of AD patients are accompanied by cerebrovascular lesions [3], and patients with vascular dementia also exhibit the hallmarks of AD, such as β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [4]. Several previous reports have suggested that vascular lesions induce Aβ deposition at the site of vascular damage, and elevated levels of circulating Aβ in the blood promote vascular lesions [5]. Additionally, various vascular risk factors such as atherosclerosis and hypercholesterolemia have been shown to increase the risk of AD [6].

Platelets are key cells that play a critical role in vascular pathology via thrombogenic activity, as well as by adhering to damaged vessels [1,7,8]. Recent studies have indicated a possible role of platelets in the pathology of vascular dementia and AD, given that platelets contain amyloid precursor proteins (APP) and α-, β-, and γ-secretases, which contribute to the production of circulating Aβ [9,10]. Abnormal platelet activity has also been reported in patients with AD [1]. In animal studies, Aβ injection enhanced platelet adhesion to injured blood vessels in a mouse model of carotid artery injury [5]. In platelets, reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as H2O2 and O2−, regulate platelet functions such as platelet aggregation and adhesion [11,12]. Therefore, various antioxidants afford preventive effects on platelet activation and thrombosis [13,14,15,16]. Furthermore, several recent studies have reported that oxidative stress occurs early in the brain of patients with AD [17], and Aβ increases ROS levels in platelets, resulting in platelet aggregation [11]. Collectively, these results suggest that Aβ-induced ROS in platelets may play a role in the vascular pathology of AD [18,19].

Rosmarinic acid (RA) is one of the major compounds commonly found in species of the family Boraginaceae and the subfamily Nepetoideae (Lamiaceae), and it is known to exhibit various biological activities, including antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects [20,21]. Previous studies have reported that RA has antioxidant and antiaggregating activities in platelets [22]. Additionally, RA has shown efficacy in vascular diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, mediated via its antiplatelet activity [22,23]. However, there is little information about the effect of RA on Aβ-induced platelet activation. In the present study, we investigated the effect of RA on Aβ-induced platelet adhesion and integrin αIIbβ3, a major adhesion molecule in platelets. We also investigated the underlying mechanism of RA in terms of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and protein kinase C (PKC), which are major signaling molecules involved in integrin activation in platelets.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

RA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA), and Trolox was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO, USA). The following commercial antibodies were used: PKC-α, PKC-βI, PKC-βII, PKC-γ, PKC-δ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA). VAS2870 was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY, USA). Gö6976, rottlerin, and lucigenin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Eptifibatide was purchased from Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA). CellTrackerTM Green 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate (CMFDA), 2,7-dichlorodihydro fluorescent diacetate (H2DCFDA), and dihydroethidium (DHE) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-human CD41a (integrin αIIb) antibody and APC anti-human CD61 (integrin β3) antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA). All other chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and were of analytical or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade.

2.2. Washed Platelet Preparation

Freshly collected platelet-rich plasma (PRP) samples from healthy volunteers were procured from the Korean Red Cross Center, a blood donation facility for research purposes. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ajou University (Project No. 202002-HM-EX-001). PRP was centrifuged at 1000× g for 10 min at 22 °C without breaking platelet pellets. The supernatant obtained was termed platelet-poor plasma. The obtained platelet pellet was washed twice with Tyrode’s buffer (pH 7.4).

2.3. Aβ1–40 Preparation

Briefly, Aβ protein fragment 1–40 (Aβ1–40; Abcam, San Francisco, CA, USA) peptides were dissolved in ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH; 4% final volume, Sigma-Aldrich) and then mixed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to obtain a 1 mg/mL solution. Aliquots were immediately stored at −80 °C and centrifuged for 15 min at 17,000× g prior to use to remove pre-aggregated materials.

2.4. Platelet Adhesion to Fibronectin

To observe platelet adhesion, stimulated platelets were stained with 10 μM CMFDA for 30 min at 37 °C. After washing with PBS, stained platelets (5 × 106 cells/mL) were added to a glass-bottom dish coated with fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After incubation for 1 h, nonadherent platelets were removed by washing with PBS. Platelets were captured in five fields per dish using a confocal microscope (Nikon, Japan). Adherent cells were calculated by expressing the areas of adherent platelets as a percentage of the total area. This experiment was repeated a total of three or five times.

2.5. Measurement of Filopodia Length and Spread Area in Platelet

For the measurement of the filopodial length and spread area of platelets, a glass-bottom dish was coated with fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After washing with PBS, treated platelets (5 × 106 cells/mL) were added to a glass-bottom dish. After incubation for 1 h, the image of live cells was acquired through differential interference contrast (DIC) imaging using a confocal microscope at 400–1000× magnification (Nikon, Japan). Filopodia, membrane protrusions supported by bundles, were randomly selected per each platelet. The filopodia length and spread area (excluding filopodia) were measured from 20 randomly selected fields with ImageJ software. This experiment was repeated a total four times.

2.6. Surface Expression of Integrins αIIb and β3

In brief, the washed human platelets (2 × 108 cells) were activated with 10 µM Aβ1–40 for 1 h at room temperature and then washed twice with Tyrode’s buffer and HEPES buffer. Next, the cells were immediately fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde on ice for 10 min. The cells were then washed twice in 1 × PBS, followed by the addition of 5 µL of FITC anti-human CD41a (integrin αIIb) or 5 µL of APC anti-human CD61 (integrin β3) to each sample and incubation for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Finally, the cells were washed with 1 × PBS, resuspended in FACS sheath fluid, and analyzed using an FACSAria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). This experiment was repeated a total of seven times.

2.7. Measurement of Free-Radical-Scavenging Activity by DPPH Assay

The free-radical-scavenging activity of RA was determined in vitro using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) assay as previously described. The protocol to assess DPPH radical scavenging activity was adapted from Brand-Williams et al. (1995), with minor changes [24]. Briefly, 100 μL aliquots of methanolic solutions containing different RA concentrations (0.1–30 μM) were added to 100 μL of a 250 μM methanolic DPPH solution. After 30 min, the absorbance was measured at 517 nm, and the percentage inhibition activity was calculated. The percentage (%) of DPPH free radical scavenging was calculated using the formula (A0 − A1)/A0 × 100, where A0 is the absorbance of the control, and A1 is the absorbance of the extract/standard. This experiment was repeated a total of three times.

2.8. ABTS Assay for Free-Radical-Scavenging Activity

The preformed radical monocation of 2,2’-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was generated as previously described [25]. The ABTS salt was weighed (19.3 mg) and dissolved in distilled water (5 mL). Then, 88 μL of K2S2O8 solution (0.0378 g/mL) was added to the ABTS solution, and the mixture was left at room temperature for 12 h in the dark. To perform measurements, the ABTS solution was diluted with ethanol to an absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.05 at 734 nm. Subsequently, 270 μL of the free-radical solution was combined with 20 μL of RA. The absorbance was measured at 734 nm after incubation at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. Antioxidant activity, expressed as a percentage of inhibition, was calculated using a previously established equation. Additionally, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was determined. This experiment was repeated a total of three times.

2.9. ROS Measurement

Briefly, washed human platelets (1 × 107 cells), pretreated with RA, Trolox, or VAS 2870 for 30 min were incubated with either Aβ1–40 for 15 min, followed by incubation with 10 µM H2DCFDA or 10 µM DHE for 30 min. Fluorescence was immediately measured using an FACSAria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm. Gated cells (n = 10,000) were analyzed for each sample. This experiment was repeated a total of six times.

2.10. Measurement of NADPH Oxidase Activity

The activity of NADPH oxidase was determined in membrane fractions (50 μg of protein) incubated with 1 mM EGTA and 5 μM lucigenin in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The assay was initiated by adding 50 μM NADPH to the incubation mixture. Samples were immediately counted using a tabletop luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems FB Luminometer; Zylux Corp., Oak Ridge, Tennessee), with sampling performed every 6 s over a 5 min period; the fluorescence values were recorded for over 2 min of stable readings and averaged for each sample. This experiment was repeated a total of seven times.

2.11. Preparation of the PKC Membrane Fraction

Platelets were lysed using different lysis buffers, and lysates were extracted using different procedures. Briefly, the cells were incubated in lysis buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM NaF, 0.2 mM Na3VO4, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 0.01 mM leupeptin, and 0.01 mg/mL aprotinin) for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged at 200,000× g in a Beckman Optima TL Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) at 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatants (cytosolic fractions, CFs) were removed, and the remaining pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer B (lysis buffer A containing 1% Triton X-100) and incubated on ice for 1 h. The suspension was then centrifuged as described above, and the supernatant (membrane fraction, MF) was obtained. This experiment was repeated a total of three times.

2.12. Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting was performed by modifying a previously described procedure [26]. Briefly, platelets were lysed in buffer A and B and centrifuged at 20,000× g for 30 min, and the supernatant was collected to obtain the cell membrane lysate. Then, proteins were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and reacted with anti-PKC-α antibody (1:500, Santa Cruz), anti-PKC-βI (1:500, Santa Cruz), anti-PKC-βII (1:500, Santa Cruz), anti-PKC-γ (1:500, Santa Cruz), anti-PKC-δ (1:500, Santa Cruz), or anti-actin (1:3000, Cell Signaling) overnight. All samples were analyzed using a LAS 4000 mini (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan). This experiment was repeated a total of three times.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Two-tailed t-tests were performed to examine differences in continuous variables, overall and at each time point, investigated in different comparison groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. RA Reduces Aβ1–40-Induced Platelet Adhesion via Integrin αIIbβ3 Blockade

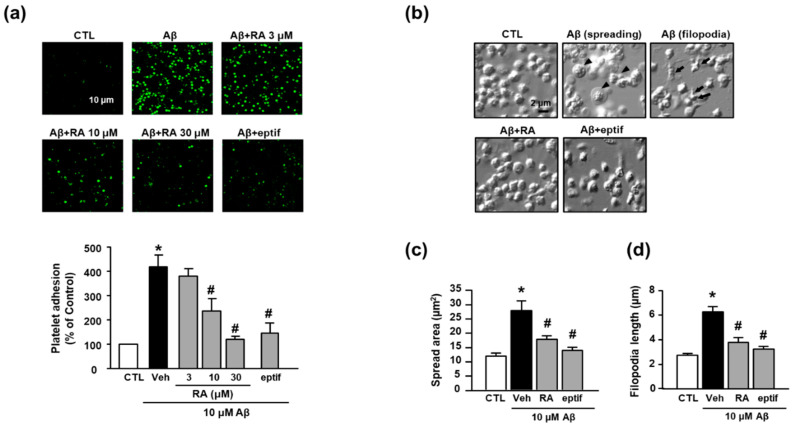

In the present study, we observed that Aβ1–40 increased platelet adhesion to fibronectin (418.65% ± 47.39%), and RA suppressed this increase in a concentration-dependent manner (236.57% ± 50.83% (10 μM) and 120.34% ± 12.62% (30 μM)) (Figure 1a). To determine whether adhesion to fibronectin is mediated by integrin αIIbβ3, we examined the effect of eptifibatide, a specific integrin αIIbβ3 inhibitor, on Aβ1–40-mediated platelet adhesion. Accordingly, eptifibatide significantly suppressed the Aβ1–40-mediated increase in platelets adhesion (147.21% ± 41.77%). Furthermore, Aβ1–40 promoted platelet spreading and filopodia to alter the platelet shape (Figure 1b). Aβ1–40 increased platelet spreading (Figure 1c) and filopodia length (Figure 1d) (27.74 ± 10.23 μm2 and 6.30 ± 1.05 μm, respectively); these changes were inhibited by RA (17.78 ± 3.35 μm2 and 3.78 ± 1.03 μm, respectively) and eptifibatide (13.82 ± 2.95 μm2 and 3.23 ± 0.55 μm, respectively).

Figure 1.

RA reduces Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion possibly through blockade of integrin αIIbβ3. (a) Representative fluorescence image (upper) and quantitative analysis (bottom) of platelet adhesion to fibronectin. Platelet adhesion (green) was quantified following stimulation with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 1 h, with or without RA (3, 10, and 30 μM) and 50 μM eptifibatide (eptif, an integrin αIIbβ3 inhibitor) pretreatment for 30 min on fibronectin-coated coverslips. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of five experiments. Scale bars represent 10 μm. (b) DIC images representative of platelet adhesion to fibronectin. Arrowheads and arrows indicate spreading and filopodia formation of platelets, respectively. Platelets were stimulated with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 1 h, with or without 30 μM RA and 50 μM eptif pretreatment for 30 min. Scale bars represent 2 μm. (c) Quantitative analysis of the surface area of platelet spread; (d) quantitative analysis of filopodia length of platelets. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM in five or more random fields in three separate experiments. * p < 0.05 compared with CTL, # p < 0.05 compared with Veh. RA, rosmarinic acid; SEM, standard error of the mean; DIC, differential interference contrast; Veh, vehicle; CTL, control.

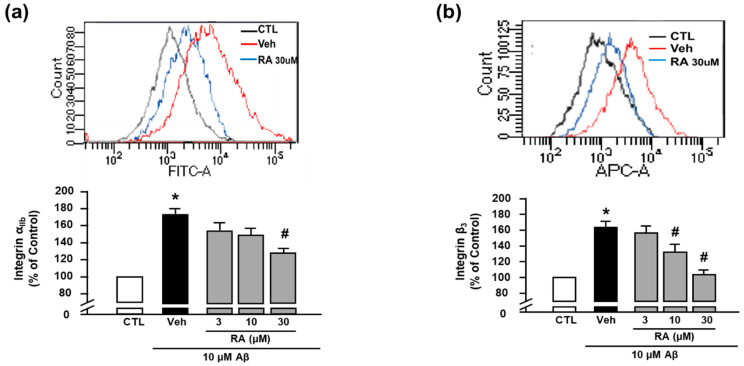

We next evaluated the activity of integrin αIIb and integrin β3 using FITC anti-human CD41a antibody and APC anti-human CD61 antibody, respectively, through flow cytometry [8]. We observed that Aβ1–40 increased the activity of integrin αIIb (176.73% ± 17.60%), and RA (30 μM) suppressed this increase (124.11% ± 12.86%) (Figure 2a). Additionally, Aβ1–40 increased the activity of integrin β3 (163.86% ± 7.08%), which was suppressed by RA (132.37% ± 9.66% at 10 μM and 104.05% ± 5.78% at 30 μM) (Figure 2b). These findings suggest that RA reduces Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion by blocking integrin αIIbβ3. Since these results show only the activity of each integrin αIIb and β3, further study is needed to clarify whether the clasping/unclasping mechanism is involved in the effects of RA on integrin αIIbβ3.

Figure 2.

RA reduces Aβ1–40-induced activation of integrin αIIbβ3. (a) Integrin αIIb levels measured through flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry histogram (upper) and quantitative analysis (bottom) of FITC–integrin αIIb-expressed platelets. (b) Integrin β3 levels measured through flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry histogram (upper) and quantitative analysis (bottom) of APC–integrin β3-expressed platelets. Platelets were stimulated with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 1 h with or without RA (3, 10, and 30 μM) pretreatment for 30 min. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of seven experiments. * p < 0.05 compared with CTL, # p < 0.05 compared with Veh. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. APC, allophycocyanin.

3.2. Antioxidant Activity of RA

We examined the in vitro antioxidant activity of RA using the DPPH and ABTS assays. As shown in Figure 3a,b, RA exhibited DPPH and ABTS radical-scavenging activities in a concentration-dependent manner. As shown in Figure 3c,d, Aβ1–40 increased ROS (H2O2 or O2−) production (351.50% ± 43.38% or 176.81% ± 24.37%, respectively), and this increase was inhibited by 30 μM RA (275.14% ± 29.61% or 142.56% ± 19.71%, respectively) and 100 μM Trolox (240.03% ± 40.99% or 118.70% ± 20.84%, respectively).

Figure 3.

Antioxidant activity of RA in vitro and in platelets. (a) DPPH radical-scavenging activity of RA in vitro. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three individual experiments. (b) ABTS radical-scavenging activity of RA in vitro. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three individual experiments. (c) Aβ1–40-induced H2O2 production in platelets quantified by measuring DCF-DA fluorescence intensity. (c, insert) Time course of Aβ1–40-stimulated H2O2 generation. Platelets were treated with 10 µM Aβ1–40 for indicated time periods (0–120 min) in the presence of DCF-DA. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of six experiments. (d) Aβ1–40-induced O2− production in platelets quantified by measuring DHE fluorescence intensity. (d, insert) Time course of Aβ1–40-stimulated O2− generation. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of six experiments. * p < 0.05 compared with CTL, # p < 0.05 compared with Veh. DPPH, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; DHE, dihydroethidium; ABTS, 2,2’-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid; DCF-DA, 2’-7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

3.3. Effects of Trolox on Aβ1–40-Induced Platelet Adhesion and Integrin αIIbβ3 Activation

Next, we used Trolox to examine whether Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion was associated with oxidative stress. We observed that 100 μM Trolox almost completely inhibited the Aβ1–40-induced increase in platelet adhesion (119.98% ± 30.71%) (Figure 4a). Additionally, Aβ1–40-induced integrin αIIb and integrin β3 activation (176.73% ± 17.60% and 163.86% ± 7.08%, respectively) was suppressed following treatment with Trolox (117.89% ± 2.53% and 94.83% ± 6.32%, respectively) (Figure 4b,c).

Figure 4.

Effects of Trolox on Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion and integrin αIIbβ3 activation. (a) Representative fluorescence image (upper) and quantitative analysis (bottom) of platelet adhesion to fibronectin. Adhesion of platelets (green) was quantified following stimulation with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 1 h, with or without 100 μM Trolox pretreatment for 30 min on fibronectin-coated coverslips. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of five experiments. Scale bars represent 10 μm. (b) Integrin αIIb levels measured using flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry histogram (upper) and quantitative analysis (bottom) of FITC–integrin αIIb-expressed platelets. (c) Integrin β3 levels measured using flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry histogram (upper) and quantitative analysis (bottom) of APC–integrin β3-expressed platelets. Platelets were stimulated with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 1 h, with or without 100 μM Trolox pretreatment for 30 min. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of seven experiments. * p < 0.05 compared with CTL, # p < 0.05 compared with Veh.

3.4. RA Decreases Aβ1–40-Induced Platelet Activation Possibly through Inhibition of NADPH Oxidase

We measured the NADPH oxidase activity to determine the source of Aβ1–40-induced ROS generation. Our results revealed that Aβ1–40 increased NADPH oxidase activity (173.48% ± 11.52%) in platelets; this effect was suppressed by treatment with RA (3, 10, and 30 μM), 10 μM VAS2870 (NADPH oxidase inhibitor), and 100 μM Trolox (114.16% ± 6.83% (30 μM RA), 108.76% ± 16.09% (VAS2870), and 108.59% ± 13.01% (100 μM Trolox)) (Figure 5a). Additionally, ROS production, including H2O2 or O2−, was reduced following the suppression of NADPH oxidase activity (250.41% ± 40.88% or 142.57% ± 19.72%, respectively, Figure 5b,c). This finding suggests that the Aβ1–40-mediated increase in ROS levels was induced via the activation of NADPH oxidase. As shown in Figure 5d,e, the Aβ1–40-mediated increase in integrin αIIb and integrin β3 activity (176.7%3 ± 17.60% and 163.86% ± 7.08%, respectively) was significantly inhibited by NADPH oxidase inhibition (117.65% ± 6.89% and 117.61% ± 14.44%, respectively). Additionally, the NADPH oxidase inhibitor completely suppressed Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion (128.23% ± 15.46%) (Figure 5f). These findings suggested that integrin αIIbβ3 activity plays an important role in mediating platelet adhesion via NADPH oxidase, and RA could regulate this process.

Figure 5.

RA inhibits Aβ-induced platelet activation possibly through inhibition of NADPH oxidase. (a) Effect of RA on NADPH oxidase activity in platelets. Platelets were pretreated with RA (3, 10, and 30 μM), 10 μM VAS2870, or 100 μM Trolox for 30 min, followed by 15 min incubation with or without Aβ1–40. (insert) Time course of NADPH oxidase activity following platelet stimulation by Aβ1–40. Platelets were treated with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for the indicated time periods (0–60 min). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of six experiments. (b) Aβ1–40-induced H2O2 production in platelets. (c) Aβ1–40-induced O2− production in platelets. O2− and O2− production were measured by DCF-DA and DHE fluorescence intensity, respectively. Platelets were stimulated with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 15 min with or without 10 μM VAS2870 pretreatment for 30 min. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three experiments. (d) Quantitative analysis of FITC–integrin αIIb-expressed platelets. (e) Quantitative analysis of APC–integrin β3-expressed platelets. Platelets were stimulated with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 1 h with or without 10 μM VAS2870 pretreatment for 30 min. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of seven experiments. (f) Representative fluorescence image (upper) and quantitative analysis (bottom) of platelet adhesion to fibronectin. Adhesion of platelets (green) was quantified following stimulation with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 1 h with or without 10 μM VAS2870 pretreatment for 30 min on fibronectin-coated coverslips. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three experiments. * p < 0.05 compared with CTL, # p < 0.05 compared with Veh.

3.5. RA Decreases Aβ1–40-Induced Platelet Activation Possibly through Inhibition of PKC-δ

The PKC family is an essential signaling mediator for platelet activation and aggregation [27]. Accordingly, we examined the potential role of the PKC family in RA-mediated suppression of platelet adhesion induced by Aβ1–40. Among the various PKC families, Aβ1–40 only increased the expression of PKC-δ (194.11% ± 27.24%); the increased PKC-δ activity was inhibited by 30 μM RA, 10 μM VAS2870, and 100 μM Trolox pretreatment (84.44% ± 23.62%, 62.02% ± 18.16%, and 69.78% ± 14.65%, respectively) (Figure 6a,b). Additionally, the Aβ1–40-mediated increases in integrin αIIb and integrin β3 levels (176.73% ± 17.60% and 194.41% ± 26.33%) were significantly decreased by the PKC-δ inhibitor, 1 μM rottlerin (116.79% ± 6.14% and 159.41% ± 21.42%, respectively), but not by the classical PKC inhibitor, 1 μM Gö6976 (167.41% ± 22.57% and 234.93% ± 31.61%, respectively) (Figure 6c,d). Similarly, the Aβ1–40-induced increase in platelet adhesion (191.94% ± 15.42%) was blocked only by rottlerin (108.55% ± 12.25%) (Figure 6e). These results indicate that inhibitory effect of RA on Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion may be mediated through inhibition of not only NADPH oxidase but also PKC-δ.

Figure 6.

RA inhibits Aβ-induced platelet activation possibly through inhibition of PKC-δ. (a) Western blot analysis of PKC isotype (-α, -βI, -βII, -γ, and -δ) levels in Aβ1–40-stimulated platelets. (b) Quantitative analysis of PKC-δ level in Aβ1–40-stimulated platelets using Western blot analysis. Platelets were treated with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 1 h with or without 30 μM RA, 10 μM VAS2870, or 100 μM Trolox pretreatment for 30 min. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three experiments. (c) Representative flow cytometry histogram (insert) and quantitative analysis of FITC–integrin αIIb-expressed platelets. (d) Representative flow cytometry histogram (insert) and quantitative analysis of APC–integrin β3-expressed platelets. Platelets were stimulated with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 1 h with or without 1 μM classical PKC inhibitor (Gö6976) or 1 μM PKC-δ inhibitor (rottlerin) pretreatment for 30 min. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of seven experiments. (e) Representative fluorescence image (upper) and quantitative analysis (bottom) of platelet adhesion to fibronectin. Adhesion of platelets (green) was quantified following stimulation with 10 μM Aβ1–40 for 1 h with or without 1 μM Gö6976 or 1 μM rottlerin pretreatment for 30 min on fibronectin-coated coverslips. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three experiments. * p < 0.05 compared with CTL, # p < 0.05 compared with Veh. PKC, protein kinase C.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we for the first time demonstrated the involvement of NADPH oxidase/ROS/PKC-δ/integrin αIIbβ3 signaling in the mechanism of Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion. We further revealed that Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion is ameliorated by RA through inhibition of these signaling pathways.

The heterogeneous cleavage pattern of APP by β- and γ-secretase results in the production of Aβ peptides of varying lengths [28]. Reportedly, Aβ1–40 is the primary blood form of Aβ, contributing to vascular amyloid deposition in AD; Aβ1–42 is the predominant form in neural plaques [29]. Aβ1–40 accounts for more than 90% of Aβ produced from APP in the body and is the predominant type released from activated human platelets. Although Aβ1–42 has been found to mediate platelet aggregation, the efficacy of Aβ1–42 on vascular events is suggested to be far less than that mediated by Aβ1–40 [30,31]. Despite numerous investigations examining the correlation between AD and vascular lesions, studies on Aβ1–40 are relatively scarce when compared with those on Aβ1–42. Previously, we reported that the altered miRNA profile in platelets from patients with Alzheimer’s pathology was similar to that of Aβ1–40-exposed platelets in vitro [32], suggesting that Aβ1–40-stimulated platelets could play an important role during the process of Alzheimer’s pathology. Consistent with our previous report, the present study revealed that Aβ1–40 increased integrin αIIbβ3 levels in human platelets, and that platelet adhesion to fibronectin was almost completely suppressed by a specific integrin αIIbβ3 inhibitor. Additionally, RA suppressed platelet adhesion and integrin αIIbβ3 activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1 and Figure 2), indicating that the effect of RA on Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion may be mediated via integrin αIIbβ3.

Numerous studies have reported that oxidative stress contributes to Aβ generation and NFT formation, suggesting a close association between amyloid plaques and ROS in the pathogenesis of AD [19,33,34]. Elevated ROS production reportedly increases the activity of β- and γ-secretases, which leads to increased APP cleavage and Aβ generation. Furthermore, in patients with AD, lipid peroxidation markers, such as 4-hydroxynonenal and malondialdehyde, were found to be elevated in the peripheral tissues, possibly because of insufficient enzymatic/nonenzymatic antioxidants [35,36]. The present study revealed that Aβ1–40 significantly increased platelet ROS levels, and the levels of O2− or H2O2 began to increase rapidly at 5 min, peaking at 15 min after Aβ1–40 exposure (Figure 3). RA significantly reduced elevated ROS levels in a concentration-dependent manner. Our results further revealed that Trolox, a powerful antioxidant, significantly inhibited both the Aβ1–40-induced increase in platelet adhesion and the integrin αIIbβ3 activation. These results suggest that Aβ1–40-induced ROS may activate platelet adhesion, consistent with the findings of a recent study indicating a potential role for platelets in the pathogenesis of AD [2,11,37]. Our results further indicate that the inhibitory effect of RA on Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion may occur through its antioxidant activity.

Enzyme pathways known to induce ROS generation include NADPH oxidase, myeloperoxidase, xanthine oxidase, or uncoupled nitric oxide synthase. In particular, NADPH oxidase, an enzyme complex composed of several subunits and a small GTPase Rac, has been reported to play a role in some neurodegenerative diseases, including dementia, via ROS-induced neuronal death [38,39]. Additionally, NADPH oxidase is suggested to be a major source of Aβ-induced ROS in hippocampal cells [38,40]. Furthermore, growing evidence suggests that the enzymatic activity of NADPH oxidases plays a significant role in promoting platelet function [11,16]. Among the seven NADPH oxidase isotypes, only NADPH oxidases 1/2 are expressed in human platelets and are closely related to platelet activity. However, the molecular mechanism underlying Aβ1–40-induced platelet activation remains poorly understood [14,41]. According to our findings, Aβ1–40 increased NADPH oxidase activity, and the NADPH oxidase inhibitor VAS2870 inhibited Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion and integrin αIIbβ3 activity. These results indicate that NADPH oxidase plays an important role in Aβ1–40-induced platelet activity, especially in terms of integrin αIIbβ3 activity (Figure 5). Although Aβ1–40-induced NADPH oxidase isotype-specific activity was not detected in this study, it is speculated that Aβ1–40 activated NADPH oxidases 1/2, as they are the primary forms present in platelets. In the present study, the Aβ1–40-induced increase in H2O2 and O2− levels was blocked by inhibiting NADPH oxidase activity and vice versa. Alternatively, Trolox decreased NADPH oxidase activity, probably owing to the rapid scavenging of generated O2− following Trolox pretreatment, as the NADPH oxidase activity was measured by detecting O2− using lucigenin.

Various cascades regulate integrin αIIbβ3 levels in platelets, among which PKC is a well-known factor [42]. However, the crosstalk between Aβ1–40 and PKC isotypes in platelets has not been previously elucidated. In the present study, we, for the first time, reported that, among several isotypes of PKC (-α, -βI, -βII, and -γ), the level of PKC-δ was remarkably increased by Aβ1–40. Additionally, Aβ1–40-induced PKC-δ activation was suppressed by RA, Trolox, or VAS2870 (Figure 6). Furthermore, we observed that rottlerin, a PKC-δ specific inhibitor, significantly inhibited the Aβ1–40-induced increase in integrin αIIbβ3 activity and platelet adhesion; however, Gö6976, a nonspecific inhibitor of PKC-α, -β, and-γ, did not demonstrate this effect. These results suggest that Aβ1–40-induced integrin αIIbβ3 activity could be regulated by PKC-δ, which produces a representative G-protein-coupled receptor signaling cascade. PKC is divided into isotypes depending on whether calcium ions mediate their regulation. PKC-α, -β, and -γ are regulated by calcium ions, whereas PKC-δ acts independently of calcium ions. Thus, it is suggested that Aβ1–40-induced integrin αIIbβ3 activity may be regulated independently of calcium ions.

Overall, the underlying mechanisms for the inhibitory effect of RA on Aβ1–40-induced platelet adhesion may involve inhibition of NADPH oxidase/ROS/PKC-δ/integrin αIIbβ3 signaling. Although reports have previously indicated a relationship between NADPH oxidase and integrin αIIbβ3 activity in platelets [7,41], this However, the present study is the first to reveal a link between NADPH oxidase/PKC-δ and Aβ1–40-induced integrin αIIbβ3 in the process of platelet adhesion. Our study further showed that RA inhibits all these signaling pathways, consequently inhibiting platelet adhesion. These results indicate that integrin αIIbβ3 and NADPH oxidase can be potential therapeutic targets for platelet-associated vascular pathology in AD. Unsurprisingly, however, the most serious side-effects commonly observed with integrin αIIbβ3 antagonists include bleeding and thrombocytopenia. Therefore, more specific integrin inhibitors involved in the pathological mechanism are needed. In addition, NADPH oxidase may exhibit different roles in other cells, thus highlighting the need for platelet-specific NADPH oxidase inhibitors. As for RA, it has been reported to attenuate the pathological function of integrin αIIbβ3, and possess antithrombotic effect against Aβ [21,43,44]. Therefore, RA could be developed as a therapeutic agent for platelet-associated vascular pathol-ogy in AD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-S.J.; methodology, B.K.L. and H.J.J.; software, B.K.L. and H.J.J.; validation, B.K.L. and H.J.J.; formal analysis, H.J.J.; investigation, Y.-S.J.; resources, Y.-S.J.; data curation, B.K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.L. and H.J.J.; writing—review and editing, B.K.L. and Y.-S.J.; visualization, B.K.L. and H.J.J.; supervision, Y.-S.J.; project administration, Y.-S.J.; funding acquisition, Y.-S.J. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI18C0920), and by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (2020R1I1A1A01071848).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ajou University (Project No. 202002-HM-EX-001).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All of the data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Laske C., Sopova K., Stellos K. Platelet activation in Alzheimer’s disease: From pathophysiology to clinical value. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2012;10:626–630. doi: 10.2174/157016112801784657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song J., Lee W.T., Park K.A., Lee J.E. Association between risk factors for vascular dementia and adiponectin. BioMed Res. Int. 2014;2014:261672. doi: 10.1155/2014/261672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raz L., Knoefel J., Bhaskar K. The neuropathology and cerebrovascular mechanisms of dementia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:172–186. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kljajevic V. Overestimating the effects of healthy aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:164. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donner L., Fälker K., Gremer L., Klinker S., Pagani G., Ljungberg L.U., Lothmann K., Rizzi F., Schaller M., Gohlke H., et al. Platelets contribute to amyloid-β aggregation in cerebral vessels through integrin αIIbβ3-induced outside-in signaling and clusterin release. Sci. Signal. 2016;9:ra52. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaf6240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luchsinger J.A., Reitz C., Honig L.S., Tang M.X., Shea S., Mayeux R. Aggregation of vascular risk factors and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65:545–551. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172914.08967.dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Z., Liang Y., Delaney M.K., Zhang Y., Kim K., Li J., Bai Y., Cho J., Ushio-Fukai M., Cheng N., et al. Shear and integrin outside-in signaling activate NADPH-oxidase 2 to promote platelet activation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021;41:1638–1653. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker R.C., Sexton T., Smyth S.S. Translational implications of platelets as vascular first responders. Circ. Res. 2018;122:506–522. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canobbio I., Abubaker A.A., Visconte C., Torti M., Pula G. Role of amyloid peptides in vascular dysfunction and platelet dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015;9:65. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q.X., Berndt M.C., Bush A.I., Rumble B., Mackenzie I., Friedhuber A., Beyreuther K., Masters C.L. Membrane-associated forms of the beta A4 amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer’s disease in human platelet and brain: Surface expression on the activated human platelet. Blood. 1994;84:133–142. doi: 10.1182/blood.V84.1.133.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visconte C., Canino J., Vismara M., Guidetti G.F., Raimondi S., Pula G., Torti M., Canobbio I. Fibrillar amyloid peptides promote platelet aggregation through the coordinated action of ITAM- and ROS-dependent pathways. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:3029–3042. doi: 10.1111/jth.15055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y., Davidson B.P., Yue Q., Belcik T., Xie A., Inaba Y., McCarty O.J., Tormoen G.W., Zhao Y., Ruggeri Z.M., et al. Molecular imaging of inflammation and platelet adhesion in advanced atherosclerosis effects of antioxidant therapy with NADPH oxidase inhibition. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2013;6:74–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.975193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiao J., Arthur J.F., Gardiner E.E., Andrews R.K., Zeng L., Xu K. Regulation of platelet activation and thrombus formation by reactive oxygen species. Redox Biol. 2018;14:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vara D., Cifuentes-Pagano E., Pagano P.J., Pula G. A novel combinatorial technique for simultaneous quantification of oxygen radicals and aggregation reveals unexpected redox patterns in the activation of platelets by different physiopathological stimuli. Haematologica. 2019;104:1879–1891. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.208819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delaney M.K., Kim K., Estevez B., Xu Z., Stojanovic-Terpo A., Shen B., Ushio-Fukai M., Cho J., Du X. Differential roles of the NADPH-oxidase 1 and 2 in platelet activation and thrombosis. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016;36:846–854. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Violi F., Pignatelli P. Platelet NOX, a novel target for anti-thrombotic treatment. Thromb. Haemost. 2014;111:817–823. doi: 10.1160/TH13-10-0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X., Wang W., Li L., Perry G., Lee H.G., Zhu X. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1842:1240–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teixeira J.P., de Castro A.A., Soares F.V., da Cunha E.F.F., Ramalho T.C. Future therapeutic perspectives into the Alzheimer’s disease targeting the oxidative stress hypothesis. Molecules. 2019;24:4410. doi: 10.3390/molecules24234410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manoharan S., Guillemin G.J., Abiramasundari R.S., Essa M.M., Akbar M., Akbar M.D. The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, parkinson’s disease, and huntington’s disease: A mini review. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016;2016:8590578. doi: 10.1155/2016/8590578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen M., Simmonds M.S.J. Rosmarinic acid. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:121–125. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hase T., Shishido S., Yamamoto S., Yamashita R., Nukima H., Taira S., Toyoda T., Abe K., Hamaguchi T., Ono K., et al. Rosmarinic acid suppresses Alzheimer’s disease development by reducing amyloid beta aggregation by increasing monoamine secretion. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:8711. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y., Tang J., Zhu H., Jiang X., Liu J., Xu W., Ma H., Feng Q., Wu J., Zhao M., et al. Aqueous extract of rabdosia rubescens leaves: Forming nanoparticles, targeting P-selectin, and inhibiting thrombosis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015;10:6905–6918. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S91316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapado L., Linares-Palomino P.J., Salido S., Altarejos J., Rosado J.A., Salido G.M. Synthesis and evaluation of the platelet antiaggregant properties of phenolic antioxidants structurally related to rosmarinic acid. Bioorg. Chem. 2010;38:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brand-Williams W., Cuvelier M.E., Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995;28:25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Re R., Pellegrini N., Proteggente A., Pannala A., Yang M., Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;26:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung S.Y., Choi S.H., Yoo S.Y., Baek S.H., Kwon S.M. Modulation of human cardiac progenitors via hypoxia-ERK circuit improves their functional bioactivities. Biomol. Ther. 2013;21:196–203. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2013.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yacoub D., Théorêt J.F., Villeneuve L., Abou-Saleh H., Mourad W., Allen B.G., Merhi Y. Essential role of protein kinase C delta in platelet signaling, alpha IIb beta 3 activation, and thromboxane A2 release. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:30024–30035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catricala S., Torti M., Ricevuti G. Alzheimer disease and platelets: How’s that relevant. Immun. Ageing. 2012;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hampel H., Shen Y., Walsh D.M., Aisen P., Shaw L.M., Zetterberg H., Trojanowski J.Q., Blennow K. Biological markers of amyloid beta-related mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2010;223:334–346. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herzig M.C., Winkler D.T., Burgermeister P., Pfeifer M., Kohler E., Schmidt S.D., Danner S., Abramowski D., Sturchler-Pierrat C., Burki K., et al. Abeta is targeted to the vasculature in a mouse model of hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:954–960. doi: 10.1038/nn1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies T.A., Long H.J., Eisenhauer P.B., Hastey R., Cribbs D.H., Fine R.E., Simons E.R. Beta amyloid fragments derived from activated platelets deposit in cerebrovascular endothelium: Usage of a novel blood brain barrier endothelial cell model system. Amyloid. 2000;7:153–165. doi: 10.3109/13506120009146830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee B.K., Kim M.H., Lee S.Y., Son S.J., Hong C.H., Jung Y.S. Downregulated platelet miR-1233-5p in patients with Alzheimer’s pathologic change with mild cognitive impairment is associated with abeta-induced platelet activation via P-selectin. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:1642. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai Z., Zhao B., Ratka A. Oxidative stress and beta-amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromol. Med. 2011;13:223–250. doi: 10.1007/s12017-011-8155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheignon C., Tomas M., Bonnefont-Rousselot D., Faller P., Hureau C., Collin F. Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Biol. 2018;14:450–464. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baldeiras I., Santana I., Proença M.T., Garrucho M.H., Pascoal R., Rodrigues A., Duro D., Oliveira C.R. Peripheral oxidative damage in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2008;15:117–128. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2008-15110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greilberger J., Koidl C., Greilberger M., Lamprecht M., Schroecksnadel K., Leblhuber F., Fuchs D., Oettl K. Malondialdehyde, carbonyl proteins and albumin-disulphide as useful oxidative markers in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic. Res. 2008;42:633–638. doi: 10.1080/10715760802255764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abubaker A.A., Vara D., Eggleston I., Canobbio I., Pula G. A novel flow cytometry assay using dihydroethidium as redox-sensitive probe reveals NADPH oxidase-dependent generation of superoxide anion in human platelets exposed to amyloid peptide β. Platelets. 2019;30:181–189. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2017.1392497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: Where are we now? J. Neurochem. 2006;97:1634–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kishida K.T., Klann E. Sources and targets of reactive oxygen species in synaptic plasticity and memory. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007;9:233–244. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Narayan P., Holmstrom K.M., Kim D.H., Whitcomb D.J., Wilson M.R., St George-Hyslop P., Wood N.W., Dobson C.M., Cho K., Abramov A.Y., et al. Rare individual amyloid-beta oligomers act on astrocytes to initiate neuronal damage. Biochemistry. 2014;53:2442–2453. doi: 10.1021/bi401606f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abubaker A.A., Vara D., Visconte C., Eggleston I., Torti M., Canobbio I., Pula G. Amyloid peptide beta1-42 induces integrin alphaIIbbeta3 activation, platelet adhesion, and thrombus formation in a NADPH oxidase-dependent manner. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019;2019:1050476. doi: 10.1155/2019/1050476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaudhary P.K., Kim S., Jee Y., Lee S.H., Kim S. Characterization of integrin alphaIIbbeta3-mediated outside-in signaling by protein kinase cdelta in platelets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:6563. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ono K., Hasegawa K., Naiki H., Yamada M. Curcumin has potent anti-amyloidogenic effects for Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibrils in vitro. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004;75:742–750. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Habtemariam S. Molecular pharmacology of rosmarinic and salvianolic acids: Potential seeds for Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:458. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All of the data is contained within the article.