Abstract

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) patients display suppression of a module of genes involved in cAMP-signaling pathways (BALcAMP) correlating with severity, therapy, and macrophage constituency. We sought to establish if gene expression changes were specific to macrophages and compared gene expression trends from multiple sources. Datasets included single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) from lung specimens including a fatal exacerbation of severe Asthma COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) after intense therapy and controls without lung disease, bulk RNA sequencing from cultured macrophage (THP-1) cells after acute or prolonged β-agonist exposure, SARP datasets, and data from the Immune Modulators of Severe Asthma (IMSA) cohort. THP monocytes suppressed BALcAMP network gene expression after prolonged relative to acute β-agonist exposure, corroborating SARP observations. scRNA-seq from healthy and diseased lung tissue revealed 13 cell populations enriched for macrophages. In severe ACOS, BALcAMP gene network expression scores were decreased in many cell populations, most significantly for macrophage populations (P < 3.9e-111). Natural killer (NK) cells and type II alveolar epithelial cells displayed less robust network suppression (P < 9.2e-8). Alveolar macrophages displayed the most numerous individual genes affected and the highest amplitude of modulation. Key BALcAMP genes demonstrate significantly decreased expression in severe asthmatics in the IMSA cohort. We conclude that suppression of the BALcAMP gene module identified from SARP BAL samples is validated in the IMSA patient cohort with physiological parallels observed in a monocytic cell line and in a severe ACOS patient sample with effects preferentially localizing to macrophages.

Keywords: asthma, adrenergic β2 receptor agonists, macrophages, obstructive lung diseases, single-cell analysis

INTRODUCTION

Recent work from our group analyzing bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples demonstrated suppression of genes in a network of cyclic-AMP (cAMP) signaling components (the “BALcAMP” gene network) that was strongly related to all indicators of severe asthma. Using weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), differential expression of this gene set was most prominent in samples with a higher proportion of alveolar macrophages, and the network also included many monocyte/macrophage-specific genes. Overall BALcAMP mean expression was found to decrease with increasing β-agonist use and with asthma severity (1). Further analysis of protein expression in THP-1 monocytes and human alveolar macrophages exposed to β-agonists indicates that this phenomenon was likely due to cAMP signaling suppression by intense β-agonist exposure in patients with severe asthma.

In this report, we attempt to deconvolute the cellular specificity of BALcAMP gene modulation utilizing lung parenchymal single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) data from a patient with severe ACOS and control patients without lung disease, as well as bulk RNA sequencing of an in vitro experiment on the THP-1 monocyte cell line and BAL samples from an external cohort of patients with severe asthma. By using these disparate data sources, we validate our previous findings and help discern which subpopulations of lung cells exhibit susceptibility for gene expression changes in severe obstructive lung disease and medication influence and better characterize the effect of intense β-agonist exposure on monocytic cells that share many features of lung macrophages.

METHODS

THP-1 Bulk RNA Preparation, Sequencing, and Analysis

THP-1 monocytes (ATCC, No. TIB-202) were cultured by standard methods as previously reported and treated with 100 nM isoproterenol (ISO) for 1 h or 24 h (2). RNA extraction was performed for deep sequencing (3). Raw sequencing reads were examined by quality metrics and aligned to human reference genome (Ensembl v91) and analyzed using R v4.0 and the R packages limma and voom (4, 5).

BAL Bulk RNA Sequencing Analysis

Publicly available bulk RNA sequencing gene expression data of BAL samples from the Immune Mechanisms in Severe Asthma (IMSA) cohort were examined from 19 patients with severe asthma and 7 healthy controls (GSE136587) (6). In this cohort, five times 50 mL sequential bronchial lavages were performed and pooled per patient. RNA isolation, cDNA library preparation, quality control, and alignment to human reference genome hg19 were performed as reported. For our analysis, raw counts were normalized and corrected for batch effects using R v4.0 and the R packages limma and voom (4, 5).

Single-Cell Tissue Preparation, RNA Library Preparation, Sequencing, and Analysis

Single-cell RNA-seq was performed on lung tissue specimens obtained from three patients: two control organ donors without acute or chronic lung disease and one patient with severe ACOS who died 3 days after suffering respiratory arrest and anoxic brain injury. In hospital, the patient was treated with high-dose IV corticosteroids, continuous β-agonist therapy, and antibiotics. Lungs from the control patients were deemed unfit for transplant due to size or blood-type constraints. Tissue was donated for research under the University of Pittsburgh’s Committee for Oversight of Research and Clinical Training Involving Decedents (CORID) protocol 451.

Tissue specimens were processed using methods previously reported (7–9). Raw sequencing reads were examined by quality metrics and mapped to human reference genome GRCh38 using the Cell Ranger pipeline (10X Genomics). Counts were analyzed using the R package Seurat v3.1 with the sctransform workflow (10–13).

Functional enrichment with Gene Ontology biological processes was performed using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources functional annotation version 6.8 (14, 15). All differentially expressed genes with adjusted P-value less than 0.05 and absolute value average log fold change greater than 0.5 were included for functional enrichment analysis.

Supplemental Data have been uploaded to web resources as follows: files containing the THP bulk RNA sequencing are posted to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14782338.v1 and single-cell RNA SEQ data are posted to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14782377.v1. IMSA RNA Seq data have been previously published (6) and are available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE136587.

RESULTS

THP-1 Monocytes Exposed to Prolonged β-Agonism Mimic Gene Expression Changes in Severe Asthmatics

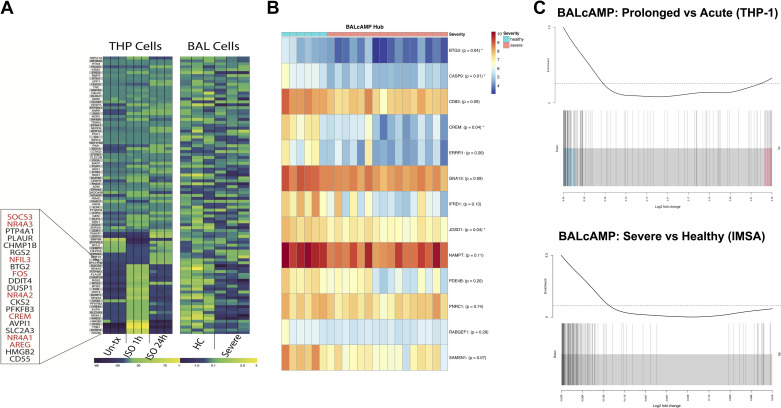

Transcriptomic analysis of THP-1 monocytes acutely exposed to the β-agonist isoproterenol demonstrated increased expression of the BALcAMP network genes. Upon prolonged exposure to isoproterenol for 24 h, these transcriptional changes were subsequently suppressed to near pretreatment levels (Fig. 1A, left). These transcriptomic changes mirror those observed in patients with severe asthma in the Severe Asthma Research Project (compared with healthy controls) (Fig. 1A, right). These changes align with our previously reported in vitro results in which acute isoproterenol exposure increased cAMP and activated the cAMP signal cascade and downstream protein expression (1). Cells displayed subsequent cAMP signaling suppression after prolonged exposure via cellular desensitization and induction of the β2-agonist receptor negative regulator b-Arrestin. The most significantly differentially expressed genes from THP cells tightly overlap with those described in the SARP BAL study, many of which were defined as BALcAMP hub genes (CREM, AREG, FOS, and NR4A members).

Figure 1.

Decreased expression of a previously identified cAMP signaling gene set is validated in a cell model under medication effect and external cohort. A: acute exposure of THP monocytes to the β-agonist isoproterenol demonstrates increased expression of the BALcAMP gene network enriched in cAMP signaling genes that is subsequently downregulated upon prolonged exposure for 24 h. These mimic transcriptional differences previously identified among healthy controls and severe asthmatics from the Severe Asthma Research Project. B: key hub genes of the BALcAMP network are significantly downregulated in severe asthmatics compared with healthy controls in an external cohort (average expression compared via Student’s t test, P-values are Bonferonni corrected). C: barcode plot demonstrating expressional downregulation of the BALcAMP network in both THP-1 monocytes under prolonged β-agonist exposure compared with acute and severe asthmatics in an external cohort (compared with healthy controls). Red text indicates SARP BAL genes most significantly changed with β-agonist use. BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; HC, healthy control; IMSA, Immune Modulators of Severe Asthma; ISO 1 h, treated with 1 h isoproterenol; ISO 24 h, treated with 24 h isoproterenol; Severe, severe asthmatic; Un-tx, untreated.

Analysis of the BALcAMP hub genes in 7 healthy control patients and 19 severe asthmatics of the IMSA cohort demonstrates decreased expression of all genes in severe asthmatics compared with healthy controls (Fig. 1B). Interrogation of the top overall differentially expressed genes between the two groups identifies the majority (28 of 50) as genes in the BALcAMP gene set, with 11 reaching statistically significant levels of differential expression (Bonferroni corrected P < 0.05 for DBR1, CASP9, PLAUR, SYT4, MAFB, ZNF410, SESN2, JOSD1, BTG3, MALT1, and most notably CREM—which is known to inhibit the cAMP pathway and suppresses T2 inflammation) (16).

Evaluating the gene module as a whole, both severe asthmatics from the IMSA cohort and THP cells treated with prolonged isoproterenol demonstrated enrichment for downregulation of an abundance of the BALcAMP genes (Fig. 1C).

Macrophage Populations in Severe ACOS Demonstrate Suppression of Genes Related to cAMP Signaling

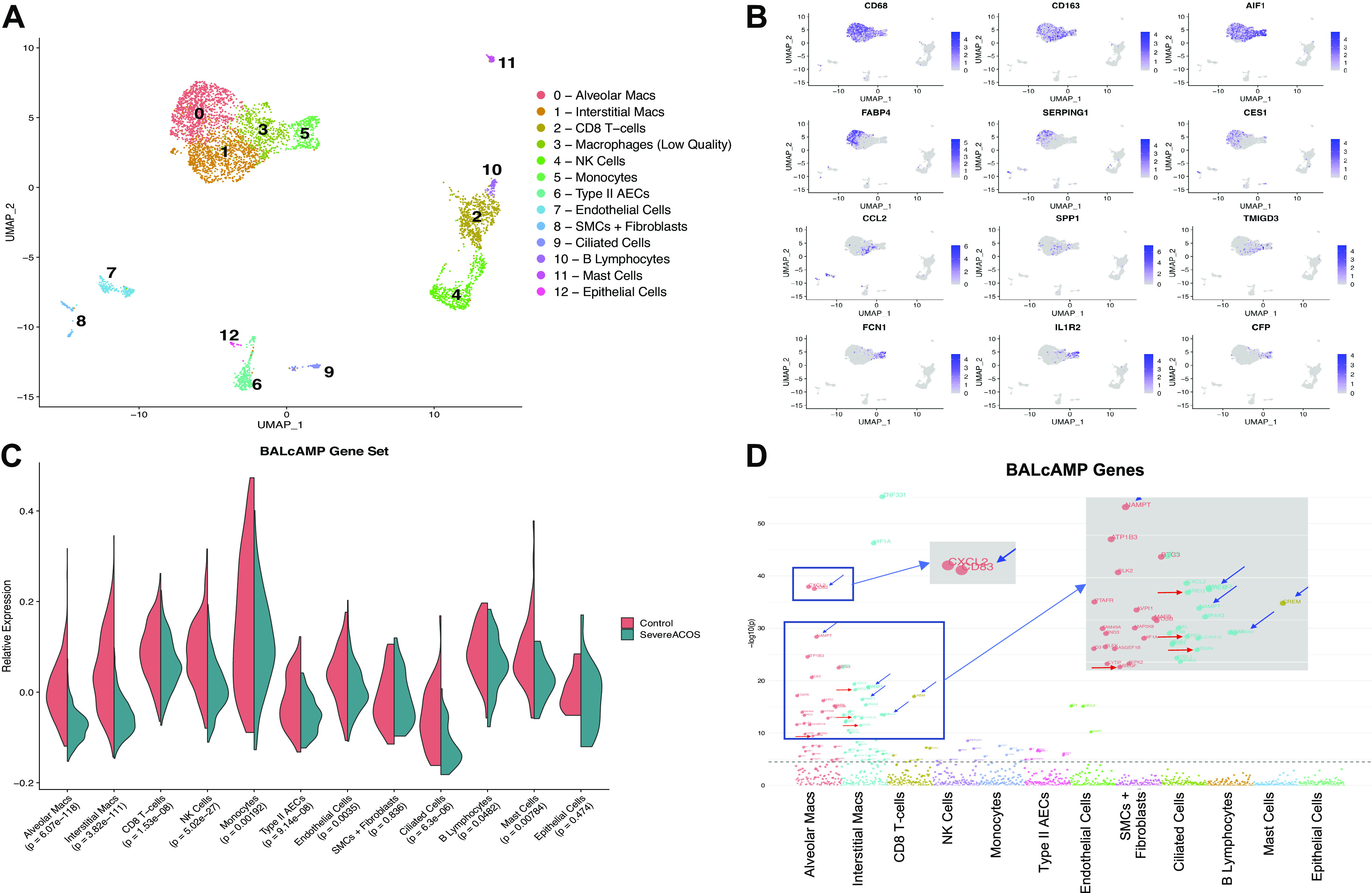

Analysis of the healthy and ACOS lung tissue single-cell transcriptome revealed 13 distinct cell populations (Fig. 2A). Cell populations were assigned based on known markers with FABP4 and IL1R2 being enriched in alveolar macrophages and monocytes, respectively (Fig. 2B) (17). All lung samples were well represented in each cluster. Alveolar macrophage, interstitial macrophage, and monocyte clusters were highly abundant in clusters 0, 1, and 5, respectively, with enrichment in the ACOS sample for these populations.

Figure 2.

Prolonged β-agonist exposure is associated with decreased expression of genes involved in cAMP signaling. A: uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot visualizing the 13 subpopulations of cells identified by canonical correlation analysis and clustering, with multiple different macrophage and monocyte populations. B: feature plots of macrophage and monocyte marker genes used for subpopulation identification. C: macrophage populations in the patient with severe ACOS demonstrate significantly decreased mean relative expression of the BALcAMP network (Bonferroni significance threshold 0.05/12 = 0.0041). D: Manhattan plot of P values for control vs. diseased expression of individual BALcAMP genes within each cluster. Mean relative group and individual expression of genes in each cell population for control vs. severe ACOS compared with unpaired t test; dashed-line denotes Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold. Blue arrows denote BALcAMP hub genes. Red arrows denote genes encoding for growth factors. ACOS, Asthma COPD Overlap Syndrome; NK, natural killer.

Whole network expression of individual cell populations revealed that average expression of the entire BALcAMP gene set was downregulated in the severe ACOS lung in concordance with SARP, IMSA, and THP-1 gene expression data (Fig. 2C). The highest significance of gene expression suppression was observed in the macrophage populations (P < 6.1e-118 and P < 3.9e-111 for the alveolar and interstitial macrophages, respectively). Less significant suppression of the BALcAMP module was noted for the natural killer (NK) cell population and type II alveolar epithelial cells.

When we interrogated individual genes in the network for statistically significant differences in expression between the healthy and severe ACOS lung across the defined cell populations, we observed that the alveolar and interstitial macrophage populations exhibited the highest number of individual genes affected along with the highest amplitude of modulation (Fig. 2D). Among the most significantly altered genes, several (CREM, CD83, BTG3, NAMPT, RASGEF1) were BALcAMP hub genes. Several genes coded for growth factors (AREG, HBEGF, EREG, VEGF) and few related to immune function (CXCL2, REL). However, it is unclear if the findings in this patient have any relationship to disease pathogenesis or are a result of intense medication effect.

Aberrations in Gene Expression for Interferon Signaling Components and Epithelial Growth Factors Are Observed in Severe ACOS and THP-1 Monocytes with Prolonged β-Agonist Exposure

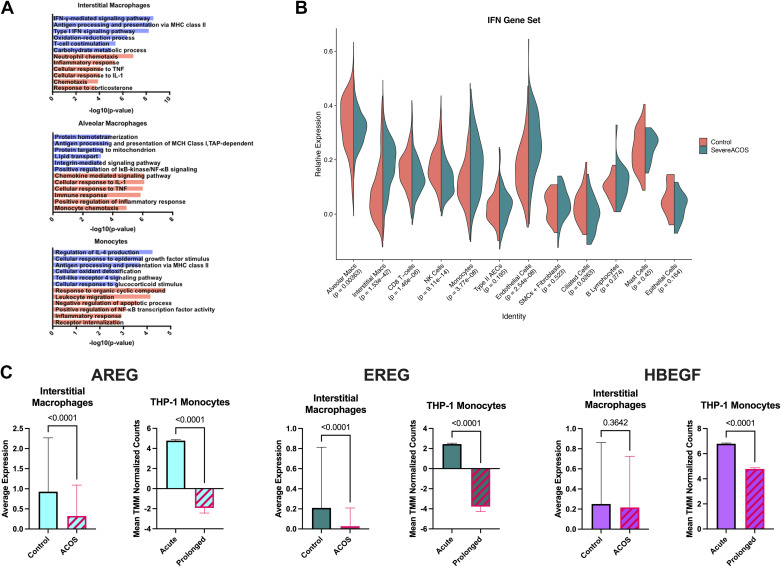

To explore the activity of each subgroup in severe ACOS compared with healthy controls, we examined genes differentially expressed in ACOS versus controls within each macrophage subgroup using functional enrichment with GO Biological Processes. In the ACOS interstitial macrophages, processes suggestive of viral infection including IFN-γ-mediated signaling, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II antigen processing, and Type-I IFN signaling were upregulated, whereas immune processes including neutrophil chemotaxis, inflammatory response, and cellular response to TNF were downregulated (Fig. 3A). Further evaluation of IFN signaling was performed by gene network analysis for IFN signaling genes. Concordant with the pathway analysis findings, interstitial macrophages in the ACOS lung displayed significant upregulation of IFN genes, with significant downregulation observed within the NK cell cluster (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Aberrations in gene expression for interferon signaling components and epithelial growth factors are observed in severe ACOS and THP-1 monocytes with prolonged β-agonist exposure. A: pathway analysis reveals functional enrichment of IFN-mediated signaling, MHC class II antigen processing, and Type-I IFN signaling in interstitial macrophages of the severe ACOS lung. B: gene expression analysis aligns with the pathways analysis findings demonstrating significantly increased gene expression of IFN signaling elements in interstitial macrophages while also demonstrating significantly decreased expression among NK cells. C: decreased average expression of epidermal growth factor-related genes AREG, EREG, and HBEGF was observed within the interstitial macrophage population, with changes in AREG and EREG expression reaching a high level of statistical significance. Consistent with these findings, upregulation of AREG, EREG, and HBEGF gene expression that is observed in THP-1 monocytes upon acute β-agonism is subsequently reversed upon prolonged exposure (mean expression levels compared via unpaired t test). ACOS, Asthma COPD Overlap Syndrome; MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

Decreased expression of genes involved in epithelial growth signaling correlates with severity of disease in brushing samples of epithelial cells from patients with severe asthma (18). Average expression of the epidermal growth factors AREG and EREG were found to be significantly decreased within the interstitial macrophage population of the ACOS lung relative to controls (P < 0.001 for both) (Fig. 3C). HBEGF expression was also downregulated but not at levels reaching statistical significance. These findings were consistent with gene expression patterns observed in our THP-1 monocytes under prolonged β-agonism and previously shown in our SARP cohort (1, 18). Although we attempted to compare downstream epidermal growth signaling genes in the epithelial compartment of our scRNAseq, there were not sufficient numbers of cells to make statistically meaningful comparisons.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the cellular specificity of the BALcAMP gene network, notable for its enrichment in cAMP signaling pathway genes, through transcriptomic analysis of human lung parenchyma, BAL, and a monocyte cell line. Taken together with our previous findings from SARP data, we find concordance in the differential BALcAMP gene modulation observed in the healthy versus severe obstructive lung disease state and a THP-1 monocyte cell model (1). Our findings also recapitulate the effects of medication influence from β-agonist exposure.

Taking advantage of single-cell sequencing, we can provide further granularity to our findings to show that the derangements in BALcAMP gene expression are primarily and significantly localized to macrophages, being shared across the alveolar and interstitial subpopulations. In addition, this study also demonstrates suppressed BALcAMP gene expression in the NK cell subpopulation of the diseased lung. These findings are notable given that macrophages and NK cells are key components of the innate response responsible for pathogen clearance, cytokine signaling, tissue scavenging, and cross-activation (19, 20). These findings validate our previous study’s analysis and suggest that these cells of the innate immune repertoire are susceptible to physiological modulation by intense β-agonist therapy.

Gene expression changes in interferon signaling in macrophages and NK cells in the severe ACOS sample are also hypothesis generating in light of the BALcAMP network changes noted in these compartments. Although speculative, the discordant transcriptomic findings for interferon signaling elements in interstitial macrophages compared with NK cells leads us to consider a potential role for impaired immune cross talk in this patient population, potentially modulated by medication effect. Although the role of NK cells in asthma continues to be elucidated, the above findings represent a potential novel role to explore in future mechanistic studies (21).

Previous work has raised concerns about the prolonged safety of β-agonist therapy in pulmonary disease, most prominently in asthma but also in the acute respiratory distress syndrome (22–25). Prior in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated impairments in immune cell function and host defense to infection after exposure to β-agonists (26–29). Impairments in alveolar macrophage functioning have been observed in patients with asthma; however, the mechanisms linking asthma with immune cell function are poorly understood (30, 31). The transcriptomic changes in the BALcAMP gene network that we describe suggest a relatively cell-selective mechanism of medication effect that may impact immune cell performance for patients with obstructive lung disease.

Epidermal growth factors have been found to reduce inflammation, preserve epithelial barrier function, and protect from acute lung injury (32, 33). Previous findings have shown decreased expression of a gene module associated with epithelial growth and repair in severe asthma (18). Our scRNASeq analysis was able to recapitulate some of these findings, showing decreased expression of the epidermal growth factors AREG and EREG in the interstitial macrophage compartment. Interestingly, our THP-1 monocyte model demonstrated upregulated expression of these two genes with acute β-agonism that was subsequently reversed upon more prolonged exposure, suggesting that medication effect may play a role in decreased epithelial protection and repair in severe asthmatics.

This report has significant limitations. Although the transcriptome data from the severe ACOS fatality tissue sample identified cell populations with good fidelity that was shared by those of the healthy control donors, this sample size is extremely limited, making conclusions somewhat speculative. We are encouraged that our understanding of the pharmacological impact on gene expression is relevant as these observations: 1) reached a high level of significance due to the large number of cells evaluated, 2) align with our analyses on BAL gene expression in the IMSA and SARP cohorts, 3) are restricted to certain cell types with the strongest signals seen in macrophages, and 4) are recapitulated partially through in vitro experiments with the monocyte/macrophage THP cell line. It would be desirable to confirm our findings in additional specimens across a spectrum of disease severities, although impractical. The case of our patient with severe ACOS represents an unfortunate outcome from which we hope to be provided an opportunity for better understanding of airway disease and the effect of pharmacotherapy in patients with obstructive lung disease. Another limitation is technical: 10X Genomics V1 chemistry reagents were used as samples in this study, and V1 versus the current V2 chemistry do not align well together with chemistry-specific, nonbiologically relevant differences. Unfortunately, this precluded our inclusion of more samples for comparison, as our center has transitioned to the updated V2 chemistry.

In conclusion, we have shown that expression of the BALcAMP gene network is suppressed in severe asthma/ACOS and under the effect of prolonged β-agonist exposure. We demonstrate that these findings are most robust in macrophages within the alveolar and interstitial compartments. Our results align with previously identified changes to gene expression due to prolonged β-agonist exposure and further extend them by suggesting that derangements in cAMP signaling within these cells may have a mechanistic effect on their immune effector function.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Bulk RNA Sequencing data: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14782338.v1.

Single-cell RNA SEQ data: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14782377.v1.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R03HL144888 and R01HL148604 (to N.M.W).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.M. and N.M.W. conceived and designed research; K.M., J.C.S., K.C., M.M.R., and R.L. performed experiments; K.M., E.V., R.N., and B.M. analyzed data; E.V., M.M.R., S.E.W., R.L., and N.M.W. interpreted results of experiments; K.M. and E.V. prepared figures; K.M., E.V., and N.M.W. drafted manuscript; K.M. , B.M., and N.M.W. edited and revised manuscript; J.C.S., K.C., S.E.W., R.L., B.M., and N.M.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Tracy Tabib, Christina Morse, and Humberto Trejo Bittar for sample handling and pathological analysis of donor specimens and organ donors everywhere who save lives and promote scientific endeavor through their generosity.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weathington N, O’Brien ME, Radder J, Whisenant TC, Bleecker ER, Busse WW, Erzurum SC, Gaston B, Hastie AT, Jarjour NN, Meyers DA, Milosevic J, Moore WC, Tedrow JR, Trudeau JB, Wong HP, Wu W, Kaminski N, Wenzel SE, Modena BD. BAL cell gene expression in severe asthma reveals mechanisms of severe disease and influences of medications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200: 837–856, 2019. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201811-2221OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weathington NM, Kanth SM, Gong Q, Londino J, Hoji A, Rojas M, Trudeau J, Wenzel S, Mallampalli RK. IL-4 Induces IL17Rb gene transcription in monocytic cells with coordinate autocrine IL-25 signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 57: 346–354, 2017. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0316OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray M, Horne W, McAleer JP, Ricks DM, Kreindler JL, Fitzsimons MS, Chan PP, Trevejo-Nunez G, Chen K, Fajt M, Chen W, Ray A, Wenzel S, Kolls JK. RNA-seq in pulmonary medicine: how much is enough? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 192: 389–391, 2015. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0475LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43: e47, 2015. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. Voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol 15: R29, 2014. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camiolo MJ, Zhou X, Oriss TB, Yan Q, Gorry M, Horne W, Trudeau JB, Scholl K, Chen W, Kolls JK, Ray P, Weisel FJ, Weisel NM, Aghaeepour N, Nadeau K, Wenzel SE, Ray A. High-dimensional profiling clusters asthma severity by lymphoid and non-lymphoid status. Cell Rep 35: 108974, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng GXY, Terry JM, Belgrader P, Ryvkin P, Bent ZW, Wilson R, Ziraldo SB, Wheeler TD, McDermott GP, Zhu J, Gregory MT, Shuga J, Montesclaros L, Underwood JG, Masquelier DA, Nishimura SY, Schnall-Levin M, Wyatt PW, Hindson CM, Bharadwaj R, Wong A, Ness KD, Beppu LW, Deeg HJ, McFarland C, Loeb KR, Valente WJ, Ericson NG, Stevens EA, Radich JP, Mikkelsen TS, Hindson BJ, Bielas JH. Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat Commun 8: 14049, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valenzi E, Bulik M, Tabib T, Morse C, Sembrat J, Trejo Bittar H, Rojas M, Lafyatis R. Single-cell analysis reveals fibroblast heterogeneity and myofibroblasts in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Ann Rheum Dis 78: 1379–1387, 2019. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Islam S, Zeisel A, Joost S, La Manno G, Zajac P, Kasper M, Lönnerberg P, Linnarsson S. Quantitative single-cell RNA-seq with unique molecular identifiers. Nat Methods 11: 163–166, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck WM, Hao Y, Stoeckius M, Smibert P, Satija R. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 177: 1888–1902.e21, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hafemeister C, Satija R. Normalization and variance stabilization of single-cell RNA-seq data using regularized negative binomial regression. Genome Biol 20: 296, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1874-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J, Shekhar K, Goldman M, Tirosh I, Bialas AR, Kamitaki N, Martersteck EM, Trombetta JJ, Weitz DA, Sanes JR, Shalek AK, Regev A, McCarroll SA. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell 161: 1202–1214, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satija R, Farrell JA, Gennert D, Schier AF, Regev A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol 33: 495–502, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4: 44–57, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 1–13, 2009. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardin M, Cho MH, McDonald ML, Wan E, Lomas DA, Coxson HO, MacNee W, Vestbo J, Yates JC, Agusti A, Calverley PMA, Celli B, Crim C, Rennard S, Wouters E, Bakke P, Bhatt SP, Kim V, Ramsdell J, Regan EA, Make BJ, Hokanson JE, Crapo JD, Beaty TH, Hersh CP; ECLIPSE and COPDGene Investigators, COPDGene Investigators—clinical centers. A genome-wide analysis of the response to inhaled β2-agonists in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacogenomics J 16: 326–335, 2016. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2015.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morse C, Tabib T, Sembrat J, Buschur KL, Bittar HT, Valenzi E, Jiang Y, Kass DJ, Gibson K, Chen W, Mora A, Benos PV, Rojas M, Lafyatis R. Proliferating SPP1/MERTK-expressing macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 54: 1802441, 2019. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02441-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Modena BD, Bleecker ER, Busse WW, Erzurum SC, Gaston BM, Jarjour NN, Meyers DA, Milosevic J, Tedrow JR, Wu W, Kaminski N, Wenzel SE. Gene expression correlated with severe asthma characteristics reveals heterogeneous mechanisms of severe disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195: 1449–1463, 2017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201607-1407OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor PR, Martinez-Pomares L, Stacey M, Lin HH, Brown GD, Gordon S. Macrophage receptors and immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol 23: 901–944, 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T, Ugolini S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol 9: 503–510, 2008. doi: 10.1038/ni1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karimi K, Forsythe P. Natural killer cells in asthma. Front Immunol 4: 159, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, Yancey SW, Dorinsky PM; SMART Study Group. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest 129: 15–26, 2006. [Erratum in Chest 129: 1393, 2006]. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spitzer WO, Suissa S, Ernst P, Horwitz RI, Habbick B, Cockcroft D, Boivin JF, McNutt M, Buist AS, Rebuck AS. The use of β-agonists and the risk of death and near death from asthma. N Engl J Med 326: 501–506, 1992. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202203260801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigo GJ, Castro-Rodríguez JA. Safety of long-acting β agonists for the treatment of asthma: clearing the air. Thorax 67: 342–349, 2012. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.155648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao Smith F, Perkins GD, Gates S, Young D, McAuley DF, Tunnicliffe W, Khan Z, Lamb SE; BALTI-2 study investigators. BALTI-2 study investigators. Effect of intravenous β-2 agonist treatment on clinical outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome (BALTI-2): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 379: 229–235, 2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61623-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maris NA, de Vos AF, Dessing MC, Spek CA, Lutter R, Jansen HM, van der Zee JS, Bresser P, van der Poll T. Antiinflammatory effects of salmeterol after inhalation of lipopolysaccharide by healthy volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172: 878–884, 2005. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-451OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maris NA, van der Sluijs KF, Florquin S, de Vos AF, Pater JM, Jansen HM, van der Poll T. Salmeterol, a beta2-receptor agonist, attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286: L1122–L1128, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00125.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hjemdahl P, Zetterlund A, Larsson K. Beta 2-agonist treatment reduces beta 2-sensitivity in alveolar macrophages despite corticosteroid treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 153: 576–581, 1996. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maris NA, Florquin S, van’t Veer C, de Vos AF, Buurman W, Jansen HM, van der Poll T. Inhalation of beta 2 agonists impairs the clearance of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae from the murine respiratory tract. Respir Res 7: 57, 2006. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitzpatrick AM, Holguin F, Teague WG, Brown LAS. Alveolar macrophage phagocytosis is impaired in children with poorly controlled asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 121: P1372–P1378.e3, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang Z, Zhang Q, Thomas CM, Chana KK, Gibeon D, Barnes PJ, Chung KF, Bhavsar PK, Donnelly LE. Impaired macrophage phagocytosis of bacteria in severe asthma. Respir Res 15: 72, 2014. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutmer J, Watkins D, Chen C-L, Velten M, Besner G. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor attenuates acute lung injury and multiorgan dysfunction after scald burn. J Surg Res 185: 329–337, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgel PR, Nadel JA. Roles of epidermal growth factor receptor activation in epithelial cell repair and mucin production in airway epithelium. Thorax 59: 992–996, 2004. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.018879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]