Abstract

Aging people living with HIV (PLWH), especially postmenopausal women may be at higher risk of comorbidities associated with HIV, antiretroviral therapy (ART), hypogonadism, and at-risk alcohol use. Our studies in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected male macaques demonstrated that chronic binge alcohol (CBA) reduced acute insulin response to glucose (AIRG), and at-risk alcohol use decreased HOMA-β in PLWH. The objective of this study was to examine the impact of ovariectomy (OVX) on glucose-insulin dynamics and integrity of pancreatic endocrine function in CBA/SIV-infected female macaques. Female macaques were administered CBA (12–15 g/kg/wk) or isovolumetric water (VEH) intragastrically. Three months after initiation of CBA/VEH administration, all macaques were infected with SIVmac251, and initiated on antiretroviral therapy (ART) 2.5 mo postinfection. After 1 mo of ART, macaques were randomized to OVX or sham surgeries (n = 7 or 8/group), and euthanized 8 mo post-OVX (study endpoint). Frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance tests (FSIVGTT) were performed at selected time points. Pancreatic gene expression and islet morphology were determined at study endpoint. There was a main effect of CBA to decrease AIRG at Pre-SIV and study endpoint. There were no statistically significant OVX effects on AIRG (P = 0.06). CBA and OVX decreased the expression of pancreatic markers of insulin docking and release. OVX increased endoplasmic stress markers. CBA but not OVX impaired glucose-insulin expression dynamics in SIV-infected female macaques. Both CBA and OVX altered integrity of pancreatic endocrine function. These findings suggest increased vulnerability of PLWH to overt metabolic dysfunction that may be exacerbated by alcohol use and ovarian hormone loss.

Keywords: alcohol, insulin, ovariectomy, pancreas, SIV infection

INTRODUCTION

Highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) has significantly increased the life expectancy of people living with HIV (PLWH). Currently, over 50% of PLWH in the United States are 50 yr of age or older (1). Early onset of menopause is reported in HIV-infected females (2, 3). Aging and increased survival of PLWH on ART are complicated by metabolic comorbidities leading to a higher risk for insulin resistance (IR), glucose intolerance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (4, 5). Though the mechanisms remain poorly understood, persistent inflammation and immune activation (6, 7), and ART (8–10) contribute to the development of metabolic dysregulation in HIV and can be exacerbated by diet, an increased overall prevalence of obesity (11–13), and at-risk alcohol use (14–16).

Impaired glucose-insulin dynamics is typified by pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. However, the potential contribution of β-cell dysfunction in HIV-related glucose dyshomeostasis remains much less characterized (17). Although most research has focused on alcohol-induced alterations of peripheral tissue insulin sensitivity, little is known on alcohol’s effects on β-cell function. In response to a glucose challenge, glucose that enters β-cells through glucose transporters is phosphorylated by glucokinase (GCK) and generates ATP. This inhibits ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP) resulting in membrane depolarization, increased Ca2+ influx through activated voltage-dependent Ca2+channels (VDCC), and exocytosis of insulin secretory granules and insulin release. Initial/acute insulin release is mediated by vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2), syntaxin1A, and synaptosomal-associated protein, 25 kDa (SNAP-25) (18). In parallel, increased blood glucose concentration increases insulin transcription (19) through canonical transcription factors, pancreatic and duodenal homeobox-1 (PDX-1), V-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A (MaFA), and NKX.2 (19–21). One of the earliest manifestations of T2DM is attenuation of the acute glucose-induced insulin secretion phase, and this can be associated with decreased number of β-cell docked insulin granules and decreased expression of genes involved in vesicle docking (22).

Although mechanisms for alcohol-induced exocrine pancreatic damage are well described, increasing evidence of alcohol-induced endocrine pancreas dysregulation is emerging. Clinical (23–25) and preclinical studies (26–28) demonstrate that at-risk alcohol use is an independent risk factor for development of T2DM (29, 30) and more than 30% of all alcohol-associated deaths are due to T2DM and cardiovascular disease (31). Clinical studies show that alcohol decreases circulating basal insulin secretion (32) and decreases circulating insulin and c-peptide levels in response to glucose (33). Similarly, rodents on an alcohol diet have decreased circulating insulin levels (34), and decreased pancreatic expression of GCK and GLUT2 (35). Moreover, in vitro alcohol exposure decreases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in human (36) and rodent (34, 37, 38) pancreatic islets, and increases β-cell apoptosis (29, 35, 39). These studies indicate that alcohol-mediated impaired β-cell function may negatively affect glucose homeostasis.

The hormonal changes associated with menopause alter multiple physiological processes. However, the effect of ovarian hormone loss on glucose homeostasis remains to be fully understood. Two clinical studies in postmenopausal females, the Women’s Health Initiative and the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study, reported that supplementing estrogen significantly reduced the incidence of T2DM (40, 41), and that estrogen therapy improved GSIS (42). Preclinical studies indicate that ovariectomy (OVX) increases symptoms similar to diabetes (43) and estrogen protects β-cells against glucolipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and apoptosis (44). Estrogen is mechanistically shown to enhance GSIS both in vitro and in vivo (45), and aromatase and estradiol rodent knockout models have blunted estrogen signaling and reduced insulin expression (44).

Our previously published data from chronic binge alcohol (CBA)-administered simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected ART-treated male macaques demonstrate significant metabolic dyshomeostasis. The Frequently Sampled Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (FSIVGTT) with a third-phase insulin infusion (Modified Minimal Model) showed that CBA impaired endocrine pancreatic response to a glucose load and decreased disposition index, an indicator of insulin resistance (46). CBA also increased skeletal muscle proteasomal activity, impaired anabolic pathways and insulin signaling (47–50), altered mitochondrial function (51, 52), and dysregulated gene networks that maintain muscle homeostasis (53). These whole body and tissue-specific alterations observed in CBA/SIV ART-treated macaques occurred in the absence of overt dysglycemia or dyslipidemia (46, 54). Not only did these alterations precede overt glucose intolerance, but they also occurred despite the consumption of a nutritionally balanced diet, and a lack of significant alterations in body composition. In subsequent translational studies in a cohort of PLWH from the Greater New Orleans Area [New Orleans Alcohol Use in HIV (NOAH) Study] (55), we showed that 36% of subjects enrolled met criteria for metabolic syndrome and 14.5% were diagnosed with T2DM. Among nondiabetics, 50% had a homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) > 1.9, and HOMA-β, an indicator of β-cell function, was negatively associated with at-risk alcohol use (56). Taken together, results from our preclinical and clinical studies indicate that at-risk-alcohol use dysregulates pancreatic endocrine function. Whether ovarian hormone loss exacerbates alcohol-induced pancreatic endocrine dysfunction in HIV/SIV is not known. The objective of this study was to examine the impact of OVX on glucose-insulin dynamics and integrity of pancreatic endocrine function in CBA/SIV-infected female macaques.

METHODS

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans (LSUHSC-NO), LA, which is accredited by Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and adhered to National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of animals. The animal housing rooms were maintained on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle, with a relative humidity of 30%–70% and a temperature of 64–84°F (18–29°C). All animals were fed a standard, commercially formulated nonhuman primate (NHP).

Animal Characteristics and Study Design

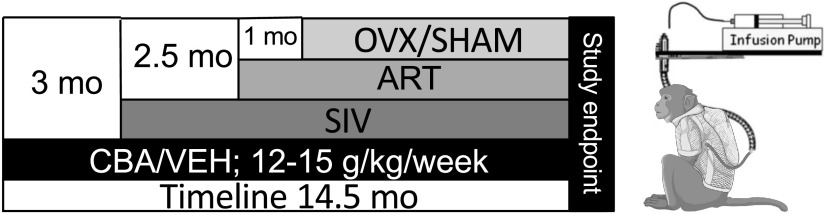

Adult (6–9 yr old) female Indian rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were randomized based on in vitro SIV infectivity kinetics to either chronic binge alcohol (CBA) or isovolumetric water (VEH) groups. Macaques were administered alcohol at a concentration of 30% (wt/vol) in water (30 min infusion; 5 days/wk; 12–15 g/kg/wk) intragastrically. Peak plasma alcohol concentrations averaged 50–60 mM (∼230 mg%) 2 h after alcohol initiation. After 3 mo of CBA/VEH administration (Pre-SIV), animals were inoculated intravaginally with SIVmac251. CBA/VEH administration continued throughout the study. At viral set-point (2.5 mo post-SIV infection), all macaques were initiated on daily subcutaneous injections of 20 mg/kg of Tenofovir [9-(2-phosphonomethoxypropyl) adenine, PMPA] and 30 mg/kg of emtricitabine (FTC), provided by Gilead Sciences Inc. (Foster City, CA). This drug combination and dose suppresses viral load and results in minimal toxicity in normal healthy macaques from infancy to adulthood and does not result in liver or renal toxicity in SIV-infected macaques (57). One-month postinitiation of ART, animals were randomized to either OVX or SHAM surgeries for a total of four treatment groups: VEH/SHAM (n = 8), VEH/OVX (n = 7), CBA/SHAM (n = 7), and CBA/OVX (n = 7). Food consumption was monitored and were provided with Boost/Ensure supplement or PRIMA-Burger (Labserv) if there was a 10% reduction in food intake. Physical examinations performed every week included monitoring body weight and measures of general health. Eight months after OVX or SHAM (study endpoint), after an overnight fast, all macaques were euthanized according to the American Veterinary Medical Association’s guidelines. Pancreatic samples were flash frozen, cryopreserved until further analysis, or fixed in Z-fix and paraffin-embedded for histological analysis. The total time for CBA/VEH administration was 14.5 mo, SIV infection was 11.5 mo, and all animals were on ART for 9 mo (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Macaque study design. Adult (6–9 yr old) female Indian rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were administered chronic binge alcohol (CBA) at a concentration of 30% (wt/vol) in water (30 min infusion; 5 days/wk; 12–15 g/kg/wk) intragastrically or isovolumetric water (VEH). After 3 months of CBA/VEH administration [Pre-simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)], all animals were inoculated intravaginally with SIVmac251. CBA/VEH administration continued throughout the study. At viral set-point (2.5 mo post-SIV infection), all macaques were initiated on antiretroviral therapy (ART). One-month postinitiation of ART, animals were randomized to either ovariectomy (OVX) or SHAM surgeries and humanely euthanized at 8 mo following OVX or SHAM (study endpoint). The total time for CBA/VEH administration was 14.5 mo, SIV infection 11.5 mo, and ART 9 mo.

Body Composition and Blood Chemistry

Body weights were recorded using an Avery Weigh-Tronix scale with a WI-125 electronic weight indicator. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans were performed to assess total body lean and fat mass using a Prodigy Total Body Fan-Beam densitometer (GE Medical Systems, Madison, WI) with a Small Animal package of the enCORE software. Blood was collected at the relevant time points and sent to the Tulane National Primate Research Center Pathology laboratory for determining complete blood counts (CBC), and blood chemistry.

Frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test (FSIVGTT) was performed as previously published (46) at baseline, Pre-SIV, and study endpoint. Briefly, macaques were preanesthetized with ketamine-xylazine and maintained under isoflurane anesthesia with oxygen supplementation throughout the experiment. Venous catheters were placed in the saphenous veins for blood sampling and cephalic veins for administration of glucose and insulin. A bolus of glucose (0.5 g/kg) was administered at time point 0 min and insulin (0.015 U/kg) 20 min later. Blood was frequently drawn between −10 and 180 min. Blood glucose levels were determined using a glucometer, serum insulin levels using ELISAs (Human Insulin ELISA, ALPCO, Salem, NH), and c-peptide using Human c-peptide ELISA (ALPCO). Minimal model software (58) was used to determine the acute insulin response to glucose (AIRG), disposition index (DI = AIRG × Si), glucose effectiveness (Sg), and insulin sensitivity index (Si). Si was adjusted for lean mass (Si/lean mass%).

The following additional formulas were also used: 1) insulinogenic index = (insulin at 18 min − insulin at 0 min)/(glucose at 18 min − glucose at 0 min); 2) C-peptide index = [C-peptide area under the curve (AUC)/glucose AUC] × 100; 3) HOMA-IR = fasting insulin (µU/mL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/405, (59, 60); and 4) HOMA-β = 360 × fasting insulin (µU/mL)/(fasting glucose (mg/dL) − 63) (61).

RNA Isolation and Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from pancreatic tissue using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of RNA using the Quantitect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Custom primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA; Table 1). Final reactions contained cDNA (50 ng), primers (500 nM), SyBr green (1:2, Quantitect SyBr Green PCR kit, Qiagen) in 20 µL. Polymerase chain reactions (qPCRs) were carried out in duplicate using a CFX96 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with ribosomal protein S13 (rpS13) as the endogenous control (54, 62) . Results are presented as fold change expression of target genes versus the control group (VEH/SIV/SHAM).

Table 1.

List of Macaca mulatta primers used

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase 3 | GTTCATCCAGTCGCTTTGT | TTCTGTTGCCACCTTTCG |

| Caspase 8 | CATCTATGGCACTGATGGAC | CCCTGACAAGCCTGAATAAA |

| Caspase 9 | CCGTTCCAGGAAGATTTGAG | AACCCGGGAAAGTAGAGTAG |

| Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) | CCACTCCAGATCATTCCTTTAG | AGGGATCATGGCAACATAAG |

| X-Box binding protein 1 (XBP1) | ATGGATTCTGGCCCTATTG | GGGAAGGGCATTTGAAGAA |

| C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) | TTTCTCCTTCGGGACACT | TTCCAGGAGGTGAGACATAG |

| Insulin | GCTGGACTACTGCAACTA | GCTGGTTCAAGGGCTTTATTC |

| Glucose transporter (GLUT2) | GAACTGCCCACAATTGCATAC | GGGACCAGAGCATAGTGATTAG |

| GLUCAGON | AAGGCGAGATTTCCCAGAAG | GTCCCTGGTGGCAAGATTAT |

| Glucokinase (GCK) | AGATGCCATCAAACGGAGAG | GCACTGATGGTCTTCGTAGTA |

| Calcium voltage-gated channel subunit α1 C (VDCC) | GATAGGAGGCAGAGAAGAGT | GTGTTGGGAAAGACAGAGAG |

| Potassium inwardly rectifying channel subfamily J member 11 (KIR6.2) | CCCAAGTTCAGCATCTCTC | GGCTACATACCATACCACAC |

| Syntaxin 1 (STX1) | GGAGATTCGAGGCTTCATTG | TCCTCCTTCGTCTTCTCATC |

| Vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2) | CCTTCACCTCCTCTCTCTT | GGAGAGGAGAGGGACTATTG |

| Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP 2 (EPAC2) | GTTATGGAAACGGGCTATAA | CTGAAGGGACCTTGGTAATG |

| Homeobox protein (NKX2.1) | CTGCTGGACTTGTGCTTCT | TCGGAGAACGATGAAGAGGA |

| MAF BZIP Transcription Factor A (MAFA) | GCGGAGAACGGTGATTT | AAGGTGGGAACGGAGAA |

| Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1) | GATACAGGATTGGCGTTGT | GAAGAGTCGGCTTCTCTAAAC |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1A (PGC1A) | GAGCGCCGTGTGATTTAT | CATCATCCCGCAGATTTACT |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1B (PGC1B) | CTCATTCGGTGCTGTGTATT | TCTGGGTTACTCCTCAGTTT |

| Ribosomal protein S 13 (RPS13) | CCCACTTGGTTGAAGTTGA | CAGGATCACACCGATTTGT |

Immunofluorescence

Paraffin sections were sliced at 5 µm, deparaffinized, and rehydrated in graded alcohols. Slides were placed in boiling sodium citrate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0) for 4 min for antigen detection. Tissue was permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X 100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Samples were blocked for 1 h in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS 0.1% Tween (PBST)-5% BSA in a humidified chamber and incubated with insulin antibody (1:1,000; No. NBP2-34260, Novus, Dallas, TX) in 10% NGS-PBST-BSA overnight at 4°C. They were then incubated in secondary antibody (AlexaFluor 568 goat anti-mouse, 1:1,000; No. A-11004 Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were washed before incubating with rabbit anti-glucagon (1:1,000; No. 2760S, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) overnight at 4°C, incubated in secondary antibody (AlexaFluor 488 goat anti-rabbit, 1:1,000; No. A-11034, Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature, and mounted with Vectashield Hardset mounting media with DAPI (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Cell Signaling Technology uses different validation steps for antibodies (https://www.cellsignal.com/about-us/our-approach-process/antibody-validation-immunohistochemistry). In addition, when antibodies were optimized in the laboratory, tissue sections with secondary antibody but no primary antibody, or primary antibody with no secondary antibody were included to ensure specificity of positive staining. Using a Nikon TE2000U microscope, 25 images of islets per animal were taken at ×40 magnification. Images were analyzed using FIJI (ImageJ) software to calculate the integrated density (area × mean gray value). Corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) was calculated by subtracting the product of the selected cell area and mean background fluorescence intensity from integrated density. Mean CTCF values from each animal were used to calculate mean CTCF values for each corresponding treatment group. Islets were imaged at ×20 and the size of 30 islets measured. Islet number was calculated from four images at ×20 of random areas of the pancreas. Average islet size was multiplied by islet number to calculate the average islet area per pancreatic area (63).

DNA Fragment End Labeling Using Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase Enzyme Staining

Staining was performed using the Fragment End Labeling (FragEL) DNA Fragmentation Detection Kit, Colorimetric—terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) Enzyme (QIA33; Millipore Sigma) according to manufacturer’s instructions with slight modifications. Paraffin sections were sliced at 5 µm, deparaffinized, and rehydrated in graded alcohols. Tissue sections were permeabilized in 20 µg/mL proteinase K for 20 min and endogenous peroxidases inactivated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min. After the samples were incubated in equilibration buffer for 20 min, samples were incubated in 60 µL of TdT labeling reaction mixture at 37°C for 20 min. The reaction was stopped by incubating in 100 µL stop solution for 20 min and rinsed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS). The samples were blocked with 100 µL blocking buffer for 10 min and then 100 µL of diluted 1× conjugate for 30 min and detected using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) Substrate Kit Peroxidase (HRP), (SK-4100 Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA). For positive controls, samples were incubated with 1 µg/µL DNase I in 1× TBS/1 mM MgSO4 for 20 min. For negative controls, TdT enzyme was substituted with water. Number of positive cells in 25 islets were counted for each animal to calculate average positive cells for each corresponding treatment group.

Statistical Analyses

Data were checked for outliers using Grubbs’ test and for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Differences in metabolic measures at Pre-SIV were determined using independent samples t test. Metabolic measures and gene expression were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at study endpoint. When appropriate, the post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test. Differences in glucose, insulin, and c-peptide levels overtime during the first 18 and 180 min of FSIVGTT were determined using two-way repeated measures ANOVA. Differences in body composition were determined using three-way repeated measures ANOVA with Sidak post hoc. All analyses were performed using Prism Graph Pad Version 7 (La Jolla, CA) and the α level of significance was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Body Composition and Blood Chemistry

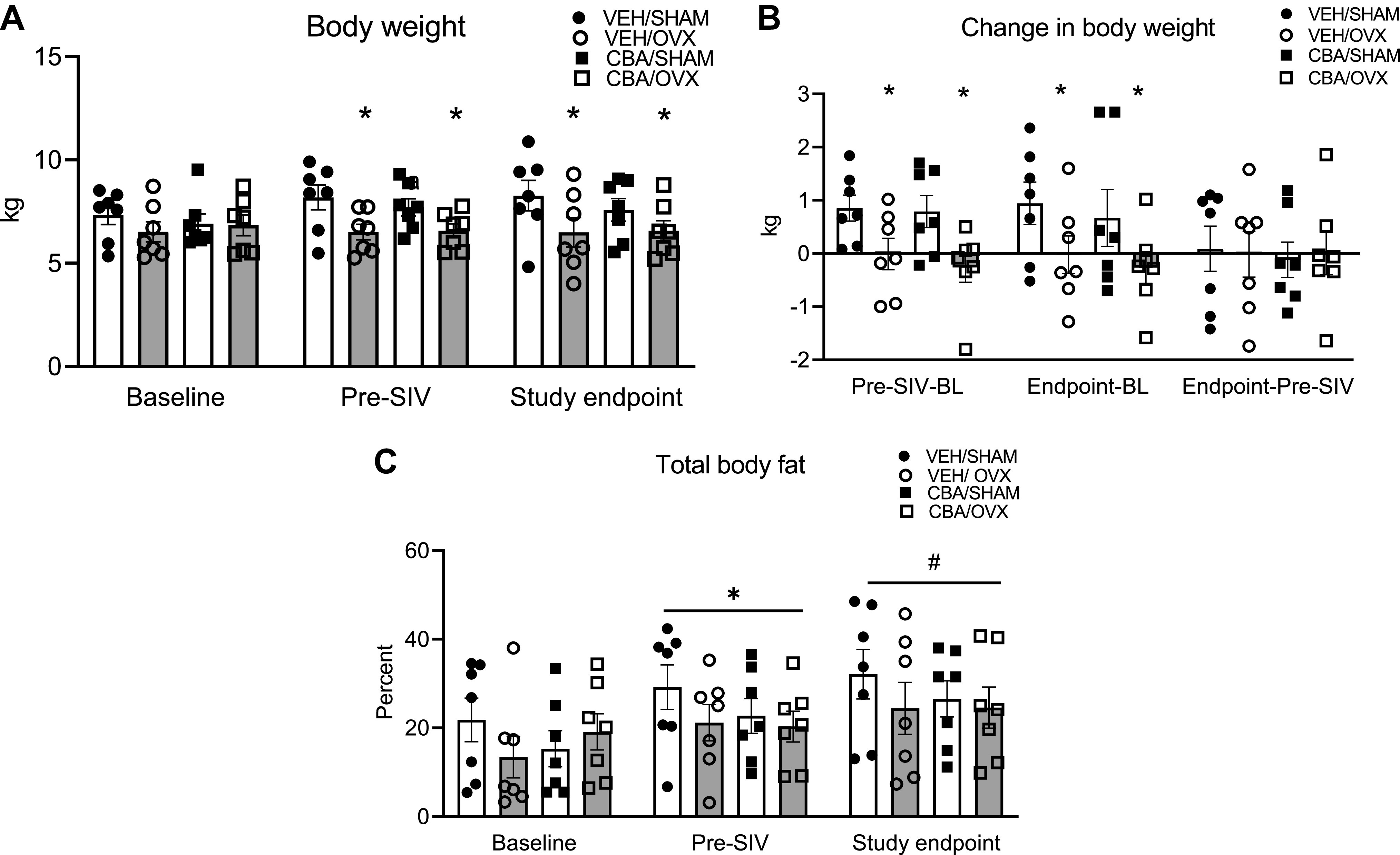

Macaques were separated into the assigned treatment groups at baseline, Pre-SIV, and study endpoint. There were no differences in body weight at baseline, but there was a main effect of OVX to decrease body weight at Pre-SIV and study endpoint (Fig. 2A). Thus, although it appears that OVX decreased body weight at study endpoint, this does not appear to be due to biological effects of OVX. Moreover, there were no significant differences in body weight gain between Pre-SIV and Study endpoint (Fig. 2B). There was a main effect of time to increase total body fat percentage, with no significant differences between treatment groups (Fig. 2C). There were no differences between treatment groups for measures of serum triglycerides, cholesterol, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) at study endpoint. All the blood chemistry values were in the normal range of rhesus macaques (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Body composition of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected female rhesus macaques. A: body weights at baseline, after 3 mo of chronic binge alcohol (CBA) and isovolumic water (VEH) administration (Pre-SIV), and 11 mo after SIV-infection (study endpoint). Macaques in the ovariectomy (OVX) groups had decreased body weight at Pre-SIV and study endpoint. B: change in body weight at Pre-SIV and study endpoint. Macaques in the OVX groups had decreased body weight gain at Pre-SIV, and study endpoint compared with baseline. There was no difference in weight gain between Pre-SIV and study endpoint. C: total body fat percent at baseline, pre-SIV, and study endpoint. There was a main effect of timepoint to increase body fat. Data analyzed using three-way repeated measures ANOVA. VEH/SIV/SHAM (n = 8), VEH/SIV/OVX (n = 7), CBA/SIV/SHAM (n = 7), and CBA/SIV/OVX (n = 7) animals. *,#P < 0.05.

Table 2.

Blood chemistries in SIV-infected female rhesus macaques

| Study Endpoint |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Measures | VEH/SHAM | VEH/OVX | CBA/SHAM | CBA/OVX |

| Triglycerides | 118.9 ± 38.4 | 102.3 ± 29.1 | 61.86 ± 11.2 | 55.71 ± 13.9 |

| Cholesterol | 104 ± 7.1 | 136.9 ± 11.1 | 123.6 ± 9.2 | 119.4 ± 7.5 |

| AST | 24.8 ± 3.3 | 26 ± 3.5 | 21 ± 2 | 32.4 ± 6.5 |

| ALT | 21.9 ± 2.6 | 28.3 ± 5.3 | 28 ± 5.1 | 29.4 ± 3.8 |

| LDH | 436.1 ± 97.2 | 351.3 ± 56.5 | 471 ± 116.5 | 350.9 ± 39.3 |

Triglycerides (mg/dL), cholesterol (mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (AST, U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT, U/L), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, U/L) levels. Data shown as means ± SE isovolumetric water (VEH)/ simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)/SHAM (n = 8), VEH/SIV/ovariectomy (OVX, n = 7), chronic binge alcohol (CBA)/SIV/SHAM (n = 7), and CBA/SIV/OVX (n = 7) groups at 11 mo after SIV-infection (study endpoint) and analyzed using two-way ANOVA.

Frequently Sampled Glucose Tolerance Tests and MinMod Analysis

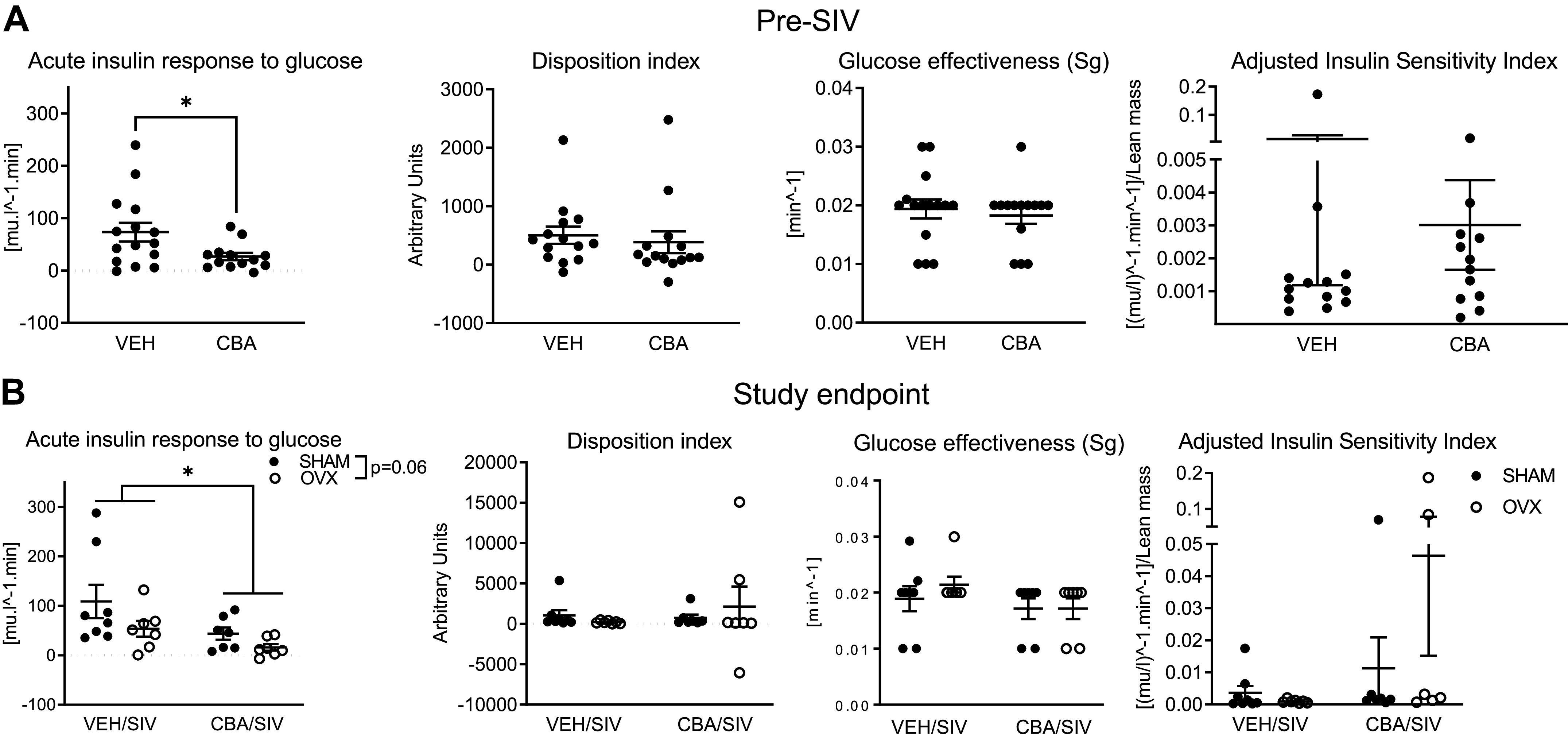

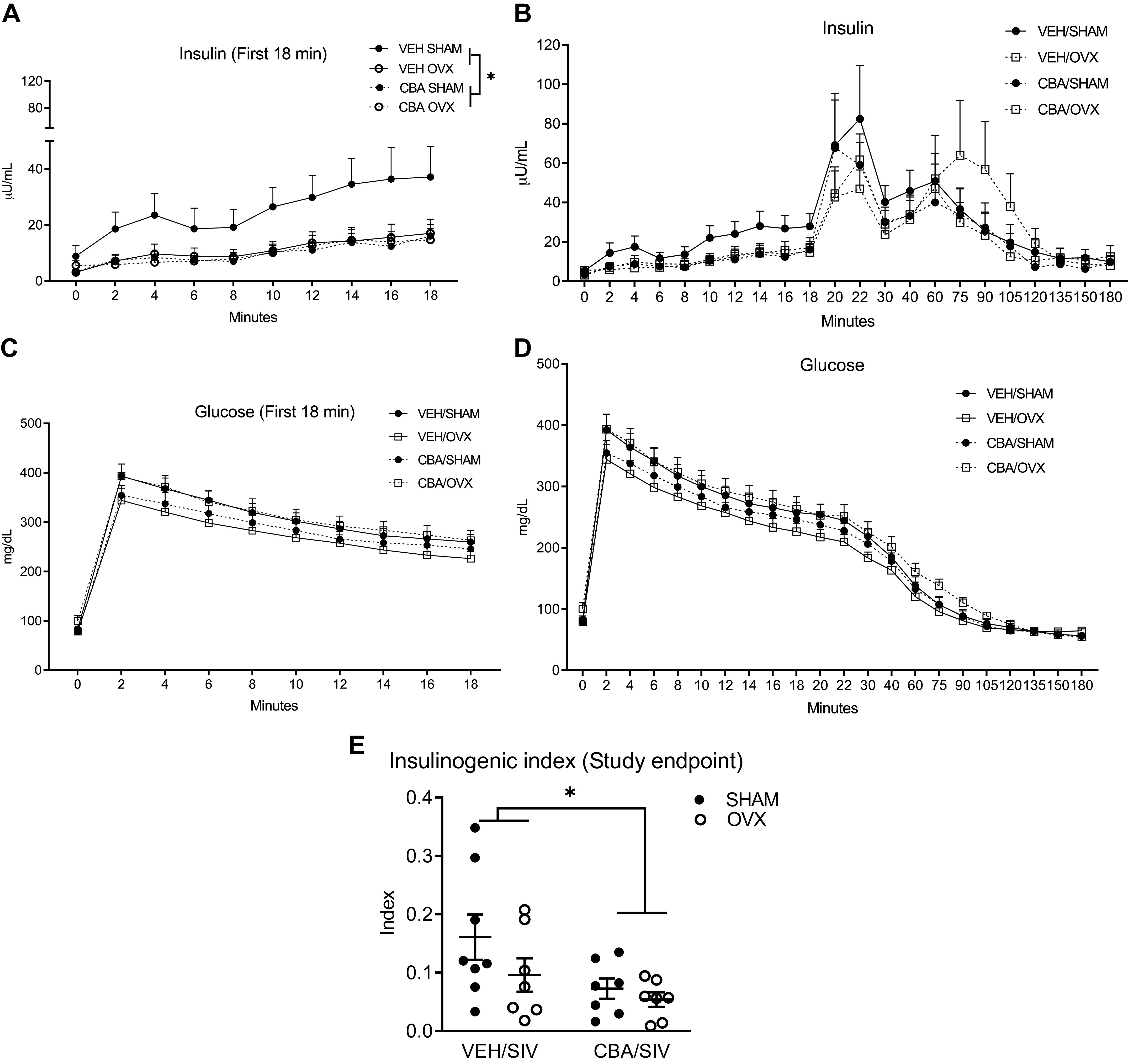

The means ± SE of baseline average values were 71.7 ± 4.3 (mU·min)/mL for AIRG, 867.1 ± 437.8 arbitrary units for DI, 0.2 ± 0.001 for Sg, and 0.004 ± 0.002 for adjusted Si, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between macaques randomized to CBA/VEH or SHAM/OVX groups. At Pre-SIV, AIRG was significantly decreased in the CBA compared with the VEH group (P = 0.02, Fig. 3A). At study endpoint, there was a main effect of CBA to decrease AIRG (P = 0.04, Fig. 3B) and a nonsignificant trend for OVX to decrease AIRG (P = 0.06). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in DI, Sg, or Si at any of the time points (Fig. 3, A and B). There was a main effect of CBA to decrease insulin levels during the first 18 min after glucose administration (Fig. 4A) and the insulinogenic index (Fig. 4E) at study endpoint. The glucose, insulin, and c-peptide AUC or c-peptide index were not significantly different between treatment groups at study endpoint (Table 3).

Figure 3.

MinMod analysis of metabolic measures from frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance tests in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected female rhesus macaques. A: acute insulin response to glucose (AIRG; 73.3 ± 17.79 and 26.6 ± 6.9), Disposition index (502.7 ± 147.9 and 385.6 ± 186.1), glucose effectiveness (Sg, 0.02 ± 0.001 and 0.02 ± 0.001), and adjusted insulin sensitivity index (Si adjusted for lean mass, 0.01 ± 0.01 and 0.003 ± 0.001) after 3 mo of chronic binge alcohol (CBA, n = 15) and isovolumic water (VEH, n = 14) administration (Pre-SIV). CBA decreased AIRG compared with VEH. B: AIRG (109.1 ± 33.8, 53.7 ± 16, 43.7 ± 2.4 and 15.98 ± 6.8), Disposition index (1,062 ± 623.8, 217.4 ± 68.9, 739.7 ± 402.7, 2,142 ± 2,498), Sg (0.018 ± 0.002, 0.02 ± 0.001, 0.017 ± 0.002 and 0.016 ± 0.002), and adjusted insulin sensitivity index (0.003 ± 0.002, 0.01 ± 0.009 0.0009 ± 0.0002 and 0.04 ± 0.03) in VEH/SIV/SHAM (n = 8), VEH/SIV/ovariectomy (OVX, n = 7), CBA/SIV/SHAM (n = 7), and CBA/SIV/OVX (n = 7) groups, 11 mo after SIV-infection (study endpoint). There was a main effect of CBA to decrease AIRG. Data shown as means ± SE and analyzed using t tests at Pre-SIV, and two-way ANOVA at study endpoint. *P < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Insulin (μU/mL), glucose levels (mg/dL), and insulinogenic index during frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance tests (FSIVGTT) in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected female rhesus macaques. A: insulin (μU/mL) tracing of the first 18 min of FSIVGTT. There was a main effect of chronic binge alcohol (CBA) to decrease insulin. B: insulin (μU/mL) tracing of the 180 min of FSIVGTT. C: glucose (mg/dL) tracing of the first 18 min of FSIVGTT. D: glucose (mg/dL) tracing of the 180 min of FSIVGTT. E: there was a main effect of CBA to decrease insulinogenic index. Data at study endpoint (11 mo after SIV-infection) are shown in isovolumic water (VEH)/SIV/SHAM (n = 8), VEH/SIV/ovariectomy (OVX, n = 7), CBA/SIV/SHAM (n = 7), and CBA/SIV/OVX (n = 7) groups. Data analyzed using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA test for A–D and two-way ANOVA for E. *P < 0.05.

Table 3.

Glucose area under the curve, insulin AUC, c-peptide AUC, and c-peptide index during frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance tests in SIV-infected female rhesus macaques

| Study Endpoint |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Measures | VEH/SIV/SHAM | VEH/SIV/OVX | CBA/SIV/SHAM | CBA/SIV/OVX |

| Glucose AUC | 4,434 ± 282.7 | 3,877 ± 223.6 | 4,117 ± 180.5 | 4,544 ± 303.1 |

| Insulin AUC | 856.4 ± 285.6 | 429.1 ± 98.2 | 430.4 ± 102.8 | 494.6 ± 151.4 |

| C-peptide AUC | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 5.4 ± 1.9 |

| C-peptide index | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 0.1 ± 0.03 |

There were no significant differences between isovolumic water (VEH)/SIV/SHAM (n = 8), VEH/SIV/ovariectomy (OVX, n = 7), chronic binge alcohol (CBA)/SIV/SHAM (n = 7), and CBA/SIV/OVX (n = 7) treatment groups 11 mo after SIV infection (study endpoint). Data analyzed using two-way ANOVA. AUC, area under the curve; SIV, simian immunodeficiency virus.

Fasting plasma glucose, insulin, and HOMA-IR were not significantly different between the treatment groups at Pre-SIV or study endpoint (Supplemental Fig. S1, A–F; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14754588). There was a main effect of OVX to decrease HOMA-β at study endpoint (Supplemental Fig. S1H).

mRNA Expression of Pancreatic Genes

Expression of genes implicated in insulin synthesis (GLUT2, GCK, EPAC, KIR6.2, VDCC, MAFA, PDX1, NKX2.1), insulin docking and release [Syntaxin1 (STX1), VAMP2], insulin and glucagon, mitochondrial homeostasis (PGC-1A, PGC-1B, TFAM), endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (XBP1, ATF4, CHOP), and apoptosis (Caspase-3, -8, -9) were determined.

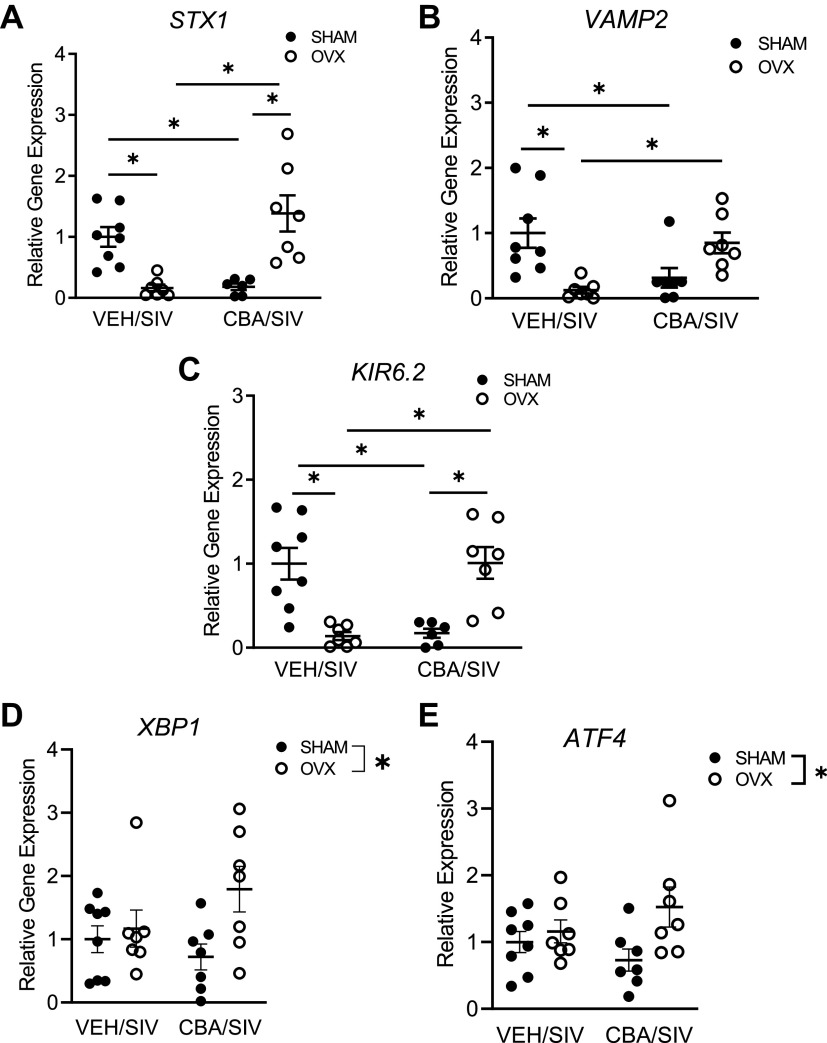

Two-way ANOVA showed an interaction between CBA and OVX to change the expression of KIR6.2, STX1, and VAMP2. Post hoc analysis demonstrated that STX1 and KIR6.2 were significantly decreased in VEH/SIV/OVX and CBA/SIV/SHAM compared with VEH/SIV/SHAM and CBA/SIV/OVX groups (Fig. 5, A and C). The expression of VAMP2 was significantly decreased in VEH/SIV/OVX and CBA/SIV/SHAM compared with VEH/SIV/SHAM group, and the expression in CBA/SIV/OVX was not different from the other three treatment groups (Fig. 5B). There was a main effect of OVX to increase XBP1 and ATF4 expression (Fig. 5, D and E). There were no statistically significant differences in the expression of any of the other genes determined (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Pancreatic gene expression in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected female rhesus macaques. A: Syntaxin1 (STX1) was decreased in isovolumic water (VEH)/SIV/ ovariectomy (OVX) and chronic binge alcohol (CBA)/SIV/SHAM compared with VEH/SIV/SHAM and CBA/SIV/OVX groups. B: vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2) was decreased in VEH/SIV/OVX and CBA/SIV/SHAM compared with VEH/SIV/SHAM group. VAMP2 was not different in CBA/SIV/OVX compared with the other three groups. C: KIR6.2, major isoform of ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KATP), was decreased in VEH/SIV/OVX and CBA/SIV/SHAM compared with VEH/SIV/SHAM and CBA/SIV/OVX groups. There was a main effect of OVX to increase X-Box binding protein 1 (XBP1) (D) and Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) (E). Data shown as means ± SE VEH/SIV/SHAM (n = 8), VEH/SIV/ovariectomy (OVX, n = 7), CBA/SIV/SHAM (n = 7), and CBA/SIV/OVX (n = 7) groups at 11 mo after SIV-infection (study endpoint) and analyzed using two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05.

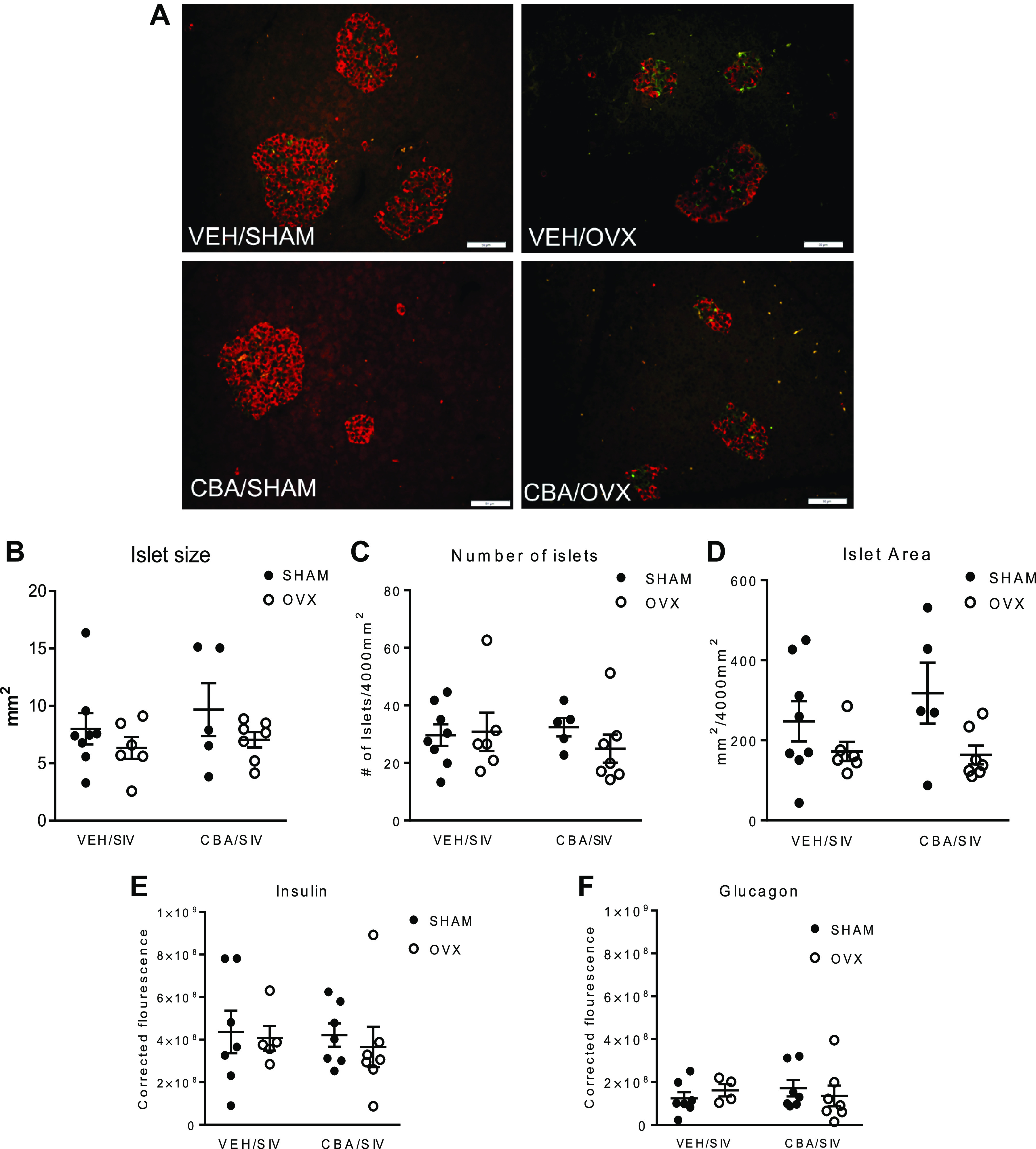

Pancreatic Islet Morphology

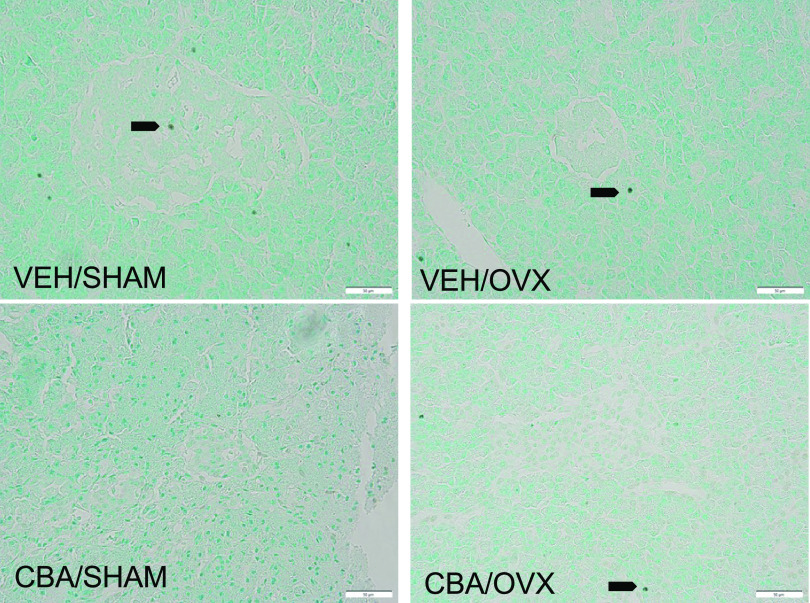

Representative images of insulin and glucagon immunostaining in the pancreas are shown in Fig. 6A. There were no significant differences in the islet size, number, or area (Fig. 6, B–D). The corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) of insulin was significantly higher than glucagon; however, there were no differences in the insulin and glucagon expression between treatment groups (Fig. 6, E and F). Representative images of FragEL immunostaining in the pancreas are shown in Fig. 7A. There were very few apoptotic cells and no significant differences between treatment groups.

Figure 6.

Pancreatic morphology in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected female rhesus macaques. A: representative images of insulin and glucagon immunostaining of isovolumic water (VEH)/SHAM, VEH/ovariectomy (OVX), chronic binge alcohol (CBA)/SHAM, CBA/OVX groups. Insulin (red) and glucagon (green) staining. B: pancreatic islet size. C: islet number. D: islet area. E: corrected total cell fluorescence of insulin. F: corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) of glucagon. Data shown as means ± SE VEH/SIV/SHAM (n = 8), VEH/SIV/ovariectomy (OVX, n = 7), CBA/SIV/SHAM (n = 7), and CBA/SIV/OVX (n = 7) groups at 11 mo after SIV-infection (study endpoint) and analyzed using two-way ANOVA. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 7.

DNA Fragment End Labeling (FragEL) using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) enzyme staining of pancreas in SIV-infected female rhesus macaques. Representative images of FragEL staining of isovolumic water (VEH)/SHAM, VEH/ovariectomy (OVX), chronic binge alcohol (CBA)/SHAM, CBA/OVX groups. There were very few apoptotic cells with no significant differences between treatment groups. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. Scale bar = 50 µm.

DISCUSSION

We examined the effects of chronic binge alcohol (CBA) and ovariectomy (OVX) on glucose-insulin dynamics and the integrity of pancreatic endocrine function in SIV-infected female rhesus macaques. Results indicate that CBA decreased the acute insulin response to glucose (AIRG). This was associated with a CBA-mediated decrease in insulin levels during the first 18 min after intravenous glucose administration, and insulinogenic index. In addition, CBA and OVX independently, but not synergistically, decreased pancreatic expression of markers of insulin release.

Although the risk for alcohol-induced exocrine pancreatic damage is recognized (64, 65), at-risk alcohol use is also a known independent risk factor for insulin resistance and T2DM (56). Our results agree with our previous report in male macaques (46) showing that CBA decreased AIRG. Neither CBA nor OVX altered the basal expression of insulin or glucagon in the fasted state. Rodent studies have also shown that chronic alcohol administration reduces insulin in response to a glucose challenge without any changes in basal expression of insulin and glucagon (66). CBA did not alter islet size or numbers, indicating that there was no overt β cell damage. Because there was no evidence of hyperglycemia or hyperinsulinemia, our findings suggest that alcohol-induced endocrine pancreas damage precedes whole body glucose intolerance. This pathophysiological framework is consistent with “pancreatogenic diabetes” (67), since CBA or OVX did not significantly affect insulin resistance, as indicated by HOMA-IR, insulin sensitivity, and disposition index.

The ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel mediated-mechanism is a major pathway influencing the first phase of insulin secretion. KIR6.2 and SUR1 are the major subunits of the KATP channel (68), and our results demonstrate that CBA and OVX decreased KIR6.2 expression. Ongoing studies will determine whether the decreased KATP channel expression decreases Ca influx and ultimately GSIS (69). Similarly, CBA and OVX decreased the expression of insulin docking molecules, Syntaxin 1 and VAMP2. Downregulation of these genes is demonstrated in T2DM organ donors, and studies with islets derived from T2DM subjects indicate that decreased acute insulin release is one of the earliest manifestations (22).

Multiple mechanisms are proposed for alcohol-mediated pancreatic changes, especially of the acinar cells—including autodigestion, oxidant stress, and generation of alcohol metabolites (65). The unfolded protein response (UPR) and subsequent ER stress is a major cause of alcoholic pancreatic injury (65). Pancreatogenic diabetes generally presents secondary to pancreatitis or exocrine pancreatic dysfunction. However, our results do not indicate CBA-mediated increased ER stress or inflammation (data not shown) indicating that these mechanisms are not a major cause for the observed endocrine pancreatic dysfunction. However, OVX increased the expression of XBP1, a protein that, when spliced, acts as a transcription factor necessary for proper protein folding (70), indicating a potential increase in ER stress following ovarian hormone loss. ATF4, a cAMP-response element-binding protein that migrates to the nucleus when a cell is undergoing chronic ER stress, was also increased due to OVX. There were no significant effects of OVX to increase C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), a proapoptotic transcription factor (71). This corresponds to our observed results that there were no significant effects of OVX or CBA on Caspase-3, -8, and -9, markers in the apoptotic pathway, nor changes in islet size and numbers.

The role that ovarian hormones play in maintaining endocrine pancreatic function remains somewhat elusive, partly due to multiple confounding factors such as adiposity and age of menopause onset (42). Studies show that estrogen aids in maintaining insulin secretion, preventing IR, and reducing diabetes incidence (42, 44, 69). The loss of ovarian hormones is significant in the context of HIV since female PLWH develop menopause earlier in life (72) and a meta-analysis reported that early-onset menopause is associated with a higher risk of T2DM (73). In our study, there was a modest (nonsignificant) decrease in AIRG due to OVX (P = 0.06). Furthermore, OVX decreased markers of insulin secretion, and increased markers of ER stress providing evidence for OVX to impair glucose-insulin dynamics in SIV infection.

There were no significant differences in total fat or body weight due to CBA or OVX, and results do not implicate body composition to be associated with the observed metabolic alterations. This is similar to our observed results in PLWH with at-risk alcohol use where body composition was not associated with dysglycemia and concords to clinical studies that suggest weaker associations between anthropometric measures and dysglycemia than other variables such as age and/or sex (74).

There are some limitations to our study. We have used intravenous glucose tolerance tests, potentially masking any contribution of incretins to the insulin response. We believe, this allows us to conclude that the observed CBA and OVX-mediated impaired glucose-insulin dynamics are due to direct effects on the pancreas. Ovarian hormone loss was achieved by surgical menopause, which does not truly mimic loss of hormones that characterize natural aging and menopause. The studies were performed under controlled experimental conditions with macaques given a healthy control diet, monitored for food consumption, and body weight changes. Future studies will include diet manipulations to more closely model dietary intake reported in PLWH to determine how alcohol or ovarian hormone loss exacerbate metabolic dysregulation. Additional in vitro studies in isolated pancreatic islets are needed to complement the study findings and to mechanistically provide evidence for the role of decreased insulin release mechanisms and their contribution to decreases in the AIRG.

Perspectives and Significance

Our data indicate that CBA contributes to impaired glucose-insulin dynamics through inadequate insulin secretion to a glucose challenge most likely mediated by impaired markers of insulin docking and release in female SIV-infected macaques. These results share similarities with those obtained from studies with male SIV-infected macaques (46) and recently in PLWH (56). Considering the findings from these studies, reducing/limiting alcohol use should be a strong recommendation for PLWH. Whether hormone replacement, physical activity, and dietary manipulations can improve metabolic dysregulation among PLWH, and people with at-risk alcohol use remains to be determined. Moreover, these data support proactive implementation of oral glucose tolerance tests to assess insulin secretory response and effectiveness among PLWH, particularly those at high risk for developing T2DM.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Fig. S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14754588.

GRANTS

The research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants P60AA009803 (to P. E. Molina), R25GM121189 (D. Torres).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.S., A.M.A., and P.E.M. conceived and designed research; L.S., D.T., A.S., C.V.S., H.M., L.C., and J.P.D. performed experiments; L.S., D.T., A.S., D.E.L., C.V.S., H.M., and L.C. analyzed data; L.S., D.T., A.S., D.E.L., and P.E.M. interpreted results of experiments; L.S. and D.T. prepared figures; L.S. and D.T. drafted manuscript; L.S., D.T., A.S., D.E.L., C.V.S., H.M., L.C., J.P.D., A.M.A., and P.E.M. edited and revised manuscript; L.S., D.T., A.S., D.E.L., C.V.S., H.M., L.C., J.P.D., A.M.A., and P.E.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

From Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans, we are grateful for the technical and veterinary support of Amy Weinberg. We also are grateful for the technical expertise of Bryant Autin, Jasmine Hall, Jane Schexnayder, and Rhonda Martinez. The editorial assistance of Rebecca Gonzales is appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV among people aged 50 and older. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html [2019 Nov 3].

- 2.de Pommerol M, Hessamfar M, Lawson-Ayayi S, Neau D, Geffard S, Farbos S, Uwamaliya B, Vandenhende MA, Pellegrin JL, Blancpain S, Dabis F, Morlat P; Groupe d'Epidémiologie Clinique du SIDA en Aquitaine GECSA). Menopause and HIV infection: age at onset and associated factors, ANRS CO3 Aquitaine cohort. Int J STD AIDS 22: 67–72, 2011. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fantry LE, Zhan M, Taylor GH, Sill AM, Flaws JA. Age of menopause and menopausal symptoms in HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 19: 703–711, 2005. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willig AL, Overton ET. Metabolic complications and glucose metabolism in HIV infection: a review of the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 13: 289–296, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s11904-016-0330-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willig AL, Overton ET. Metabolic consequences of HIV: pathogenic insights. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 11: 35–44, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastard JP, Fellahi S, Couffignal C, Raffi F, Gras G, Hardel L, Sobel A, Leport C, Fardet L, Capeau J; ANRS CO8 APROCO-COPILOTE Cohort Study Group. Increased systemic immune activation and inflammatory profile of long-term HIV-infected ART-controlled patients is related to personal factors, but not to markers of HIV infection severity. J Antimicrob Chemother 70: 1816–1824, 2015. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couturier J, Agarwal N, Nehete PN, Baze WB, Barry MA, Jagannadha Sastry K, Balasubramanyam A, Lewis DE. Infectious SIV resides in adipose tissue and induces metabolic defects in chronically infected rhesus macaques. Retrovirology 13: 30, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s12977-016-0260-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhagwat P, Ofotokun I, McComsey GA, Brown TT, Moser C, Sugar CA, Currier JS. Changes in abdominal fat following antiretroviral therapy initiation in HIV-infected individuals correlate with waist circumference and self-reported changes. Antivir Ther 22: 577–586, 2017. doi: 10.3851/IMP3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown TT, Tassiopoulos K, Bosch RJ, Shikuma C, McComsey GA. Association between systemic inflammation and incident diabetes in HIV-infected patients after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Diabetes Care 33: 2244–2249, 2010. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Wit S, Sabin CA, Weber R, Worm SW, Reiss P, Cazanave C, El-Sadr W, Monforte Ad, Fontas E, Law MG, Friis-Møller N, Phillips A; Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Incidence and risk factors for new-onset diabetes in HIV-infected patients: the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Diabetes Care 31: 1224–1229, 2008. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakal DR, Coelho LE, Luz PM, Clark JL, De Boni RB, Cardoso SW, Veloso VG, Lake JE, Grinsztejn B. Obesity following ART initiation is common and influenced by both traditional and HIV-/ART-specific risk factors. J Antimicrob Chemother 73: 2177–2185, 2018. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koethe JR, Hulgan T, Niswender K. Adipose tissue and immune function: a review of evidence relevant to HIV infection. J Infect Dis 208: 1194–1201, 2013. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lake JE. The fat of the matter: obesity and visceral adiposity in treated HIV infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 14: 211–219, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11904-017-0368-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, London AS, Caetano R, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Morton SC, Orlando M, Shapiro M. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. J Stud Alcohol 63: 179–186, 2002. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazo M, Gange SJ, Wilson TE, Anastos K, Ostrow DG, Witt MD, Jacobson LP. Patterns and predictors of changes in adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: longitudinal study of men and women. Clin Infect Dis 45: 1377–1385, 2007. doi: 10.1086/522762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molina PE, Amedee AM, Winsauer P, Nelson S, Bagby G, Simon L. Behavioral, metabolic, and immune consequences of chronic alcohol or cannabinoids on HIV/AIDs: studies in the non-human primate SIV model. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 10: 217–232, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s11481-015-9599-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sims EK, Park G, Mather KJ, Mirmira RG, Liu Z, Gupta SK. Immune reconstitution in ART treated, but not untreated HIV infection, is associated with abnormal beta cell function. PLoS One 13: e0197080, 2018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rorsman P, Ashcroft FM. Pancreatic β-cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: of mice and men. Physiol Rev 98: 117–214, 2018. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrali SS, Sampley ML, Vanderford NL, Ozcan S. Glucose regulation of insulin gene expression in pancreatic beta-cells. Biochem J 415: 1–10, 2008. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneto H, Miyatsuka T, Fujitani Y, Noguchi H, Song KH, Yoon KH, Matsuoka TA. Role of PDX-1 and MafA as a potential therapeutic target for diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 77, Suppl 1: S127–S137, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu JS, Hebrok M. All mixed up: defining roles for β-cell subtypes in mature islets. Genes Dev 31: 228–240, 2017. doi: 10.1101/gad.294389.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Omar-Hmeadi M, Idevall-Hagren O. Insulin granule biogenesis and exocytosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 78: 1957–1970, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03688-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen BN, Hagen C, Faber OK, Lindholm J, Boisen P, Worning H. Glucose tolerance and B cell function in chronic alcoholism: its relation to hepatic histology and exocrine pancreatic function. Metabolism 32: 1029–1032, 1983. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(83)90072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatonen KA, Virtamo J, Eriksson JG, Perala MM, Sinkko HK, Leiviska J, Valsta LM. Modifying effects of alcohol on the postprandial glucose and insulin responses in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 96: 44–49, 2012. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.031682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pezzarossa A, Cervigni C, Ghinelli F, Molina E, Gnudi A. Glucose tolerance in chronic alcoholics after alcohol withdrawal: effect of accompanying diet. Metabolism 35: 984–988, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JY, Hwang JY, Lee DY, Song EH, Park KJ, Kim GH, Jeong EA, Lee YJ, Go MJ, Kim DJ, Lee SS, Kim BJ, Song J, Roh GS, Gao B, Kim WH. Chronic ethanol consumption inhibits glucokinase transcriptional activity by Atf3 and triggers metabolic syndrome in vivo. J Biol Chem 289: 27065–27079, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.585653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SJ, Ju A, Lim SG, Kim DJ. Chronic alcohol consumption, type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), and growth hormone (GH) in ethanol-treated diabetic rats. Life Sci 93: 778–782, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson NG, Suhaidi FA, Law WX, Liang NC. Chronic moderate alcohol drinking alters insulin release without affecting cognitive and emotion-like behaviors in rats. Alcohol 70: 11–22, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hodge AM, Dowse GK, Collins VR, Zimmet PZ. Abnormal glucose tolerance and alcohol consumption in three populations at high risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Epidemiol 137: 178–189, 1993. [Erratum in Am J Epidemiol 138: 279, 1993]. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei M, Gibbons LW, Mitchell TL, Kampert JB, Blair SN. Alcohol intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in men. Diabetes Care 23: 18–22, 2000. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kranzler HR, Soyka M. Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorder: a review. JAMA 320: 815–824, 2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonnet F, Disse E, Laville M, Mari A, Hojlund K, Anderwald CH, Piatti P, Balkau B; RISC Study Group. Moderate alcohol consumption is associated with improved insulin sensitivity, reduced basal insulin secretion rate and lower fasting glucagon concentration in healthy women. Diabetologia 55: 3228–3237, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2701-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patto RJ, Russo EK, Borges DR, Neves MM. The enteroinsular axis and endocrine pancreatic function in chronic alcohol consumers: evidence for early beta-cell hypofunction. Mt Sinai J Med 60: 317–320, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasineni K, Thomes PG, Kubik JL, Harris EN, Kharbanda KK, Casey CA. Chronic alcohol exposure alters circulating insulin and ghrelin levels: role of ghrelin in hepatic steatosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 316: G453–G461, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00334.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JY, Song EH, Lee HJ, Oh YK, Park YS, Park JW, Kim BJ, Kim DJ, Lee I, Song J, Kim WH. Chronic ethanol consumption-induced pancreatic {beta}-cell dysfunction and apoptosis through glucokinase nitration and its down-regulation. J Biol Chem 285: 37251–37262, 2010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.142315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikolic D, Micic D, Dimitrijevic-Sreckovic V, Kerkez M, Nikolic B. Effect of alcohol on insulin secretion and viability of human pancreatic islets. Srp Arh Celok Lek 145: 159–164, 2017. doi: 10.2298/SARH160204023N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen KH, Lee JH, Nyomba BL. Ethanol causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and impairment of insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells. Alcohol 46: 89–99, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang S, Luo Y, Feng A, Li T, Yang X, Nofech-Mozes R, Yu M, Wang C, Li Z, Yi F, Liu C, Lu WY. Ethanol induced impairment of glucose metabolism involves alterations of GABAergic signaling in pancreatic β-cells. Toxicology 326: 44–52, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dembele K, Nguyen KH, Hernandez TA, Nyomba BL. Effects of ethanol on pancreatic beta-cell death: interaction with glucose and fatty acids. Cell Biol Toxicol 25: 141–152, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s10565-008-9067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanaya AM, Herrington D, Vittinghoff E, Lin F, Grady D, Bittner V, Cauley JA, Barrett-Connor E; Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Glycemic effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy: the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 138: 1–9, 2003. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Margolis KL, Bonds DE, Rodabough RJ, Tinker L, Phillips LS, Allen C, Bassford T, Burke G, Torrens J, Howard BV; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Effect of oestrogen plus progestin on the incidence of diabetes in postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Trial. Diabetologia 47: 1175–1187, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1448-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Godsland IF. Oestrogens and insulin secretion. Diabetologia 48: 2213–2220, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1930-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riant E, Waget A, Cogo H, Arnal JF, Burcelin R, Gourdy P. Estrogens protect against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in mice. Endocrinology 150: 2109–2117, 2009. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le May C, Chu K, Hu M, Ortega CS, Simpson ER, Korach KS, Tsai MJ, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Estrogens protect pancreatic beta-cells from apoptosis and prevent insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 9232–9237, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602956103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nadal A, Rovira JM, Laribi O, Leon-Quinto T, Andreu E, Ripoll C, Soria B. Rapid insulinotropic effect of 17beta-estradiol via a plasma membrane receptor. FASEB J 12: 1341–1348, 1998. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.13.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ford SM, Simon L, Vande Stouwe C, Allerton T, Mercante DE, Byerley LO, Dufour JP, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, Molina PE. Chronic binge alcohol administration impairs glucose-insulin dynamics and decreases adiponectin in asymptomatic simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R888–R897, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00142.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dodd T, Simon L, LeCapitaine NJ, Zabaleta J, Mussell J, Berner P, Ford S, Dufour J, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, Molina PE. Chronic binge alcohol administration accentuates expression of pro-fibrotic and inflammatory genes in the skeletal muscle of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38: 2697–2706, 2014. doi: 10.1111/acer.12545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.LeCapitaine NJ, Wang ZQ, Dufour JP, Potter BJ, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, Cefalu WT, Molina PE. Disrupted anabolic and catabolic processes may contribute to alcohol-accentuated SAIDS-associated wasting. J Infect Dis 204: 1246–1255, 2011. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Molina PE, Lang CH, McNurlan M, Bagby GJ, Nelson S. Chronic alcohol accentuates simian acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated wasting. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 138–147, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Molina PE, McNurlan M, Rathmacher J, Lang CH, Zambell KL, Purcell J, Bohm RP, Zhang P, Bagby GJ, Nelson S. Chronic alcohol accentuates nutritional, metabolic, and immune alterations during asymptomatic simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30: 2065–2078, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duplanty AA, Siggins RW, Allerton T, Simon L, Molina PE. Myoblast mitochondrial respiration is decreased in chronic binge alcohol administered simian immunodeficiency virus-infected antiretroviral-treated rhesus macaques. Physiol Rep 6: e13625, 2018. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duplanty AA, Simon L, Molina PE. Chronic binge alcohol-induced dysregulation of mitochondrial-related genes in skeletal muscle of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques at end-stage disease. Alcohol Alcohol 52: 298–304, 2017. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agw107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simon L, Hollenbach AD, Zabaleta J, Molina PE. Chronic binge alcohol administration dysregulates global regulatory gene networks associated with skeletal muscle wasting in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. BMC Genomics 16: 1097, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2329-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ford SM Jr, Simon Peter L, Berner P, Cook G, Vande Stouwe C, Dufour J, Bagby G, Nelson S, Molina PE. Differential contribution of chronic binge alcohol and antiretroviral therapy to metabolic dysregulation in SIV-infected male macaques. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 315: E892–E903, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00175.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Welsh DA, Ferguson T, Theall KP, Simon L, Amedee A, Siggins RW, Nelson S, Brashear M, Mercante D, Molina PE. The New Orleans Alcohol Use in HIV Study: launching a translational investigation of the interaction of alcohol use with biological and socioenvironmental risk factors for multimorbidity in people living with HIV. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 43: 704–709, 2019. doi: 10.1111/acer.13980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon L, Ferguson TF, Vande Stouwe C, Brashear MM, Primeaux SD, Theall KP, Welsh DA, Molina PE. Prevalence of insulin resistance in adults living with HIV: implications of alcohol use. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 36: 742–752, 2020. doi: 10.1089/AID.2020.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Molina PE, Amedee AM, Veazey R, Dufour J, Volaufova J, Bagby GJ, Nelson S. Chronic binge alcohol consumption does not diminish effectiveness of continuous antiretroviral suppression of viral load in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38: 2335–2344, 2014. doi: 10.1111/acer.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pacini G, Bergman RN. MINMOD: a computer program to calculate insulin sensitivity and pancreatic responsivity from the frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 23: 113–122, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0169-2607(86)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isokuortti E, Zhou Y, Peltonen M, Bugianesi E, Clement K, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Lacorte JM, Gastaldelli A, Schuppan D, Schattenberg JM, Hakkarainen A, Lundbom N, Jousilahti P, Mannisto S, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Saltevo J, Anstee QM, Yki-Jarvinen H. Use of HOMA-IR to diagnose non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based and inter-laboratory study. Diabetologia 60: 1873–1882, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jing J, Pan Y, Zhao X, Zheng H, Jia Q, Mi D, Chen W, Li H, Liu L, Wang C, He Y, Wang D, Wang Y, Wang Y; Investigators for ACROSS China. Insulin resistance and prognosis of nondiabetic patients with ischemic stroke: the ACROSS-China study (abnormal glucose regulation in patients with acute stroke across China). Stroke 48: 887–893, 2017. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 27: 1487–1495, 2004. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simon L, Ford SM Jr, Song K, Berner P, Vande Stouwe C, Nelson S, Bagby GJ, Molina PE. Decreased myoblast differentiation in chronic binge alcohol-administered simian immunodeficiency virus-infected male macaques: role of decreased miR-206. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 313: R240–R250, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00146.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schrader H, Menge BA, Schneider S, Belyaev O, Tannapfel A, Uhl W, Schmidt WE, Meier JJ. Reduced pancreatic volume and beta-cell area in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 136: 513–522, 2009. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ammann RW, Muellhaupt B. Progression of alcoholic acute to chronic pancreatitis. Gut 35: 552–556, 1994. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.4.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rasineni K, Srinivasan MP, Balamurugan AN, Kaphalia BS, Wang S, Ding WX, Pandol SJ, Lugea A, Simon L, Molina PE, Gao P, Casey CA, Osna NA, Kharbanda KK. Recent advances in understanding the complexity of alcohol-induced pancreatic dysfunction and pancreatitis development. Biomolecules 10: 669, 2020. doi: 10.3390/biom10050669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee SS, Hong OK, Ju A, Kim MJ, Kim BJ, Kim SR, Kim WH, Cho NH, Kang MI, Kang SK, Kim DJ, Yoo SJ. Chronic alcohol consumption results in greater damage to the pancreas than to the liver in the rats. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 19: 309–318, 2015. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2015.19.4.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Andersen DK, Korc M, Petersen GM, Eibl G, Li D, Rickels MR, Chari ST, Abbruzzese JL. Diabetes, pancreatogenic diabetes, and pancreatic cancer. Diabetes 66: 1103–1110, 2017. doi: 10.2337/db16-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wollheim CB, Janjic D, Siegel EG, Kikuchi M, Sharp GW. Importance of cellular calcium stores in glucose-stimulated insulin release. Ups J Med Sci 86: 149–164, 1981. doi: 10.3109/03009738109179223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kang L, Chen CH, Wu MH, Chang JK, Chang FM, Cheng JT. 17β-estradiol protects against glucosamine-induced pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. Menopause 21: 1239–1248, 2014. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sriburi R, Jackowski S, Mori K, Brewer JW. XBP1: a link between the unfolded protein response, lipid biosynthesis, and biogenesis of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 167: 35–41, 2004. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hu H, Tian M, Ding C, Yu S. The C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) transcription factor functions in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and microbial infection. Front Immunol 9: 3083, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Imai K, Sutton MY, Mdodo R, Del Rio C. HIV and menopause: a systematic review of the effects of HIV infection on age at menopause and the effects of menopause on response to antiretroviral therapy. Obstet Gynecol Int 2013: 340309, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/340309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Anagnostis P, Christou K, Artzouchaltzi AM, Gkekas NK, Kosmidou N, Siolos P, Paschou SA, Potoupnis M, Kenanidis E, Tsiridis E, Lambrinoudaki I, Stevenson JC, Goulis DG. Early menopause and premature ovarian insufficiency are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol 180: 41–50, 2019. doi: 10.1530/EJE-18-0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dave JA, Lambert EV, Badri M, West S, Maartens G, Levitt NS. Effect of nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy on dysglycemia and insulin sensitivity in South African HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 57: 284–289, 2011. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318221863f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]