Abstract

The apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele is the most well-established risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), although its relationship to age at onset and clinical phenotype is unclear. We aimed to assess relationships between APOE genotype and age at onset, amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition and typical versus atypical clinical presentations in AD. Frequency of APOE ε4 carriers by age at onset was assessed in 447 AD patients, 138 atypical AD patients recruited by the Neurodegenerative Research Group at Mayo Clinic, and 309 with typical AD from ADNI. APOE ε4 frequency increased with age at onset in atypical AD but showed a bell-shaped curve in typical AD where highest frequencies were observed between 65 and 70 years. Typical AD showed higher APOE ε4 frequencies than atypical AD only between the ages of 57 and 69 years. Global Aβ standard uptake value ratios did not differ according to APOE e4 status in either group. APOE genotype varies by both age at onset and clinical phenotype in AD, highlighting the heterogeneous nature of AD.

Keywords: Apolipoprotein, atypical Alzheimer’s disease, posterior cortical atrophy, logopenic, beta-amyloid, PET

1. INTRODUCTION

The apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele is the most common and well established risk factor for typical late-onset amnestic Alzheimer’s dementia (Corder et al., 1993; Strittmatter et al., 1993a; Strittmatter et al., 1993b). The presence of one ε4 allele increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia by 2–4 fold and the presence of two ε4 alleles increases the risk by 8–10 fold (Farrer et al., 1997). The presence of the ε4 allele has also been associated with an earlier age of onset in Alzheimer’s dementia (Meyer et al., 1998). In contrast, presence of the APOE ε2 allele has been shown to reduce the risk for developing Alzheimer’s dementia and delay the age at onset (Corder et al., 1994).

Thirty-eight percent of patients with AD pathology under the age of 60 (Balasa et al., 2011), and 25% of all AD patients (Whitwell et al., 2012), do not complain of early memory loss, but instead present with other cognitive complaints and can be referred to as atypical presentations of AD. Two of the most common variants of atypical AD are logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA) (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011) which is characterized by language abnormalities and posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) (Crutch et al., 2017) which is characterized by visuospatial and perceptual abnormalities. These atypical AD variants often have a relatively young age at onset, although age at onset can vary widely. Less is known about the role of the APOE genotype in patients with atypical AD. It does appear as though APOE ε4 greatly increases the odds of PCA (OR=4.7, 95% CI 3.4–6.7; p<0.0001) (Carrasquillo et al., 2016; Carrasquillo et al., 2014), although studies have found varying results concerning the APOE ε4 allele frequency in atypical AD. Some investigators have found that the frequency of the APOE ε4 allele is lower in LPA and PCA compared to typical AD (Josephs et al., 2014; Mesulam et al., 1997; Phillips et al., 2019; Rogalski et al., 2011; Schott et al., 2006; van der Flier et al., 2006), although others have observed similar frequencies, particularly between PCA and typical Alzheimer’s dementia (Carrasquillo et al., 2014; Lehmann et al., 2013; Tang-Wai et al., 2004). Given that age is related to APOE ε4 risk in typical Alzheimer’s dementia, it is possible that discrepancies across these atypical AD studies may be related to differences in age at onset.

APOE has been associated with beta-amyloid (Aβ) mechanistic pathways (Castellano et al., 2011; Zerbinatti et al., 2004), and studies have shown that both age and APOE ε4 carriers are associated with higher Aβ PET burden and lower CSF Aβ1–42 in cognitively normal and undemented populations (Jack et al., 2015; Lim et al., 2017; Morris et al., 2010; Reiman et al., 2009; Rowe et al., 2010; Vemuri et al., 2010). However, findings relating APOE genotype to Aβ in cohorts of patients with Alzheimer’s dementia have given mixed results (Baek et al., 2020; Drzezga et al., 2009; Fleisher et al., 2013; Ge et al., 2018; Lehmann et al., 2014; Mattsson et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2013; Nitsch et al., 1995; Ossenkoppele et al., 2013; Prince et al., 2004; Rowe et al., 2010; Tapiola et al., 2000; Vemuri et al., 2010), possibly due to clinical heterogeneity across cohorts and differences in age at onset. The relationship between APOE genotype and Aβ PET in patients with atypical clinical presentations of AD, and whether this relationship differs from typical AD, is unclear.

The primary aim of this study was to assess the relationship between APOE genotype frequency and onset age in a large cohort of atypical AD patients, and determine how frequencies in atypical AD across the age spectrum compare to those observed in a cohort of typical Alzheimer’s dementia patients from the Alzheimer’s disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). A secondary aim was to assess the relationship between APOE genotype and Aβ PET in atypical AD and ADNI to determine whether APOE plays a role in determining the degree of Aβ deposition in AD when accounting for age and clinical phenotype. We hypothesize that any relationship between APOE and Aβ PET would be similar in typical and atypical AD given that it likely reflects a fundamental disease mechanism in AD.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patients

The atypical AD cohort consisted of 138 patients that fulfilled clinical diagnostic criteria for either LPA (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011) (n=81) or PCA (Crutch et al., 2017) (n=57) that had been recruited by the Neurodegenerative Research Group (NRG) from the Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, between 11/30/2010 and 10/11/2018. Patients were enrolled regardless of age. All patients underwent a detailed neurological evaluation by one of two behavioral neurologists (KAJ/JGR), detailed neuropsychological testing, a 3T volumetric MRI and provided a blood sample for APOE testing. All but one patient also underwent Aβ-PET using Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) PET. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic IRB and all patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment and early AD. From ADNI, we selected typical AD patients who had an APOE genotype and a known age at onset (n=309). These patients were identified from ADNI 1, 2, 3 and ADNI-GO. The inclusion criteria for AD patients in ADNI have been previously published (www.adni.loni.usc.edu). Briefly, patients must have had abnormal memory function on the Logical Memory II subscale from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised, a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score between 20 and 26, a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0.5 or 1.0, with a Memory Box score of 1.0, and meet NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for probable AD (McKhann et al., 1984; McKhann et al., 2011; Petersen et al., 2010). Patients enrolled in ADNI were between 55 and 90 years old. One-hundred and twenty-one patients in the ADNI cohort had undergone (18F)florbetapir PET to assess Aβ deposition. Florbetapir was included in ADNI 2, 3 and ADNI-GO.

APOE genotyping for the atypical AD cohort was performed as previously described (Crook et al., 1994). ADNI methods are provided at www.adni-info.org.

2.2. Aβ PET analysis

The atypical AD patients were all scanned on a PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare) while operating in 3D mode. Patients were injected with PiB of approximately 628 MBq (range, 385–723 MBq) and after a 40-to-60-minute uptake period a 20-minute PiB scan was obtained. Emission data was reconstructed into a 256x256 matrix with a 30-cm FOV. All patients also underwent a 3T volumetric head MRI within two days of the PiB-PET scan, which included a 3D magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo sequence (MPRAGE). All MPRAGE scans underwent corrections for intensity inhomogeneity and gradient unwarping before analysis. The Aβ-PET scans were registered to the corresponding MPRAGE scan using a 6 degrees-of-freedom registration in SPM12. The Mayo Clinic Adult Lifespan Template (MCALT) (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mcalt/) was then transformed into the native space of each MPRAGE using ANTs software. Median Aβ uptake was calculated for the following regions-of-interest (ROIs) defined using MCALT: inferior parietal, superior parietal, supramarginal gyrus, angular gyrus, cingulate [anterior, mid, posterior and retrosplenial], precuneus, superior frontal, middle frontal, orbitofrontal, inferior frontal [operculum+triangularis], medial frontal, fusiform, lateral temporal [inferior, middle and superior temporal gyri + Heschl], and temporal pole. Uptake was calculated from the grey and white matter in each region and divided by uptake in the cerebellar crus grey matter to calculate standard uptake value ratios (SUVRs). A global Aβ SUVR was calculated as the weighted average from the ROIs and a cut-point of 1.48 was used to determine positivity (Jack et al., 2017).

The ADNI patients were injected with 370 MBg (10 mCi) of florbetapir with a 20 minute acquisition performed 50–70 minutes post injection. Images were collected as a series of 4 × 5 min frames, and attenuation corrected with either CT or PET transmission. The global Aβ SUVR that is calculated by the ADNI group was utilized in this study (Jagust et al., 2015). Briefly, florbetapir analyses used coregistered MRI images obtained concurrently with PET which are segmented and parcellated using FreeSurfer 5.3.0 (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). A composite cortical target reference ROI was created using a weighted average of the frontal, lateral temporal, lateral parietal, and anterior/posterior cingulate regions, and the whole cerebellum was used as a reference region to generate a global Aβ SUVR. The ADNI cut-point of 1.11 was utilized to determine positivity (Landau et al., 2013).

2.3. Statistical analysis

We used logistic regression to estimate the proportion of APOE ε4 carriers by onset age and clinical group. Rather than assume a linear relationship on the logit scale, we modelled onset age using a restricted cubic spline with knots at 60, 70, and 80 years and allowed the age effect to vary by clinical group (Harrell, 2001). We tested for group-wise differences across age at onset using a likelihood ratio test comparing nested models. The reduced model had only a non-linear age effect in the model (3 degrees of freedom [d.f.]). The full model had the non-linear age effect, group, and the interaction between age and group (6 d.f.). Using the inverse logit transformation, p = exp(xTβ) / (1 + exp(xTβ)), we report estimates and 95% confidence intervals on the probability scale. We also performed hypothesis testing for the difference in APOE ε4 frequency between atypical AD and typical AD at onset ages 50–80 using linear contrasts from the logistic model. The results of these hypothesis tests, along with point and interval estimates of the difference in ε4 frequency, are summarized graphically. The relationship between confidence intervals and p-values enables us to interpret significance from the graph since a 95% CI that does not include zero indicates the difference is significant at p<0.05. Further details and age-specific estimates are provided in the Supplementary Materials. These logistic regression models were performed using all atypical and typical AD patients (N=138 and N=309) to increase statistical power, and then repeated in the sub-sample that had a positive Aβ PET (N=133 and N=108). We used linear regression to estimate mean Aβ burden by age at PET and APOE ε4 status within each clinical group. These analyses were limited to patients who were Aβ PET positive to ensure that we were assessing relationships in patients with underlying AD (only four atypical AD and 13 typical AD patients were Aβ-negative and removed from this analysis). Separate regression models were fit for atypical AD and typical AD. The full model included age, APOE genotype, and the interaction. We used the main effects model to compare age-adjusted difference between APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers by diagnosis group as follows. The log-transformed dependent variable allows us to interpret the difference between APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers in terms of percentage difference in SUVR. This interpretation is approximate and applies to small difference as reported here. Since these two estimated differences were on a comparable percentage scale and from two independent samples, we used the regression estimates and their standard errors to perform a z test comparing the two estimates (Clogg et al., 1995).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic comparisons

The demographic features of the cohorts are shown in Table 1. Compared to typical AD, the atypical AD cohort had a higher frequency of women, a decade younger age at onset, and less impaired performance on the CDR sum of boxes and MMSE. The frequency of APOE ε4 carriers was lower in atypical AD (52%) compared to typical AD (66%), particularly for ε4ε4 homozygotes (9% vs 20%).

Table 1:

Patient characteristics

| All patients (n=447) |

Patients with positive Aβ PET scans (n=241) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atypical AD (n=138) | Typical AD (n=309) | P-value | Atypical AD (n=133) | Typical AD (n=108) | P-value | |

| Female, n (%) | 82 (59%) | 135 (44%) | 0.003 | 79 (59%) | 49 (45%) | 0.038 |

| APOE carrier, n (%) | 72 (52%) | 205 (66%) | 0.006 | 70 (53%) | 80 (74%) | 0.001 |

| ε2/ε2 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| ε2/ε3 | 7 (5%) | 7 (2%) | 7 (5%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| ε2/ε4 | 6 (4%) | 7 (2%) | 5 (4%) | 2 (2%) | ||

| ε3/ε3 | 59 (43%) | 97 (31%) | 56 (42%) | 28 (26%) | ||

| ε3/ε4 | 53 (38%) | 135 (44%) | 52 (39%) | 52 (48%) | ||

| ε4/ε4 | 13 (9%) | 63 (20%) | 13 (10%) | 26 (24%) | ||

| Age at onset, yr | 62 (42, 80) | 72 (52, 88) | <0.001 | 61 (42, 80) | 72 (52, 88) | <0.001 |

| Age at PET, yr | 65 (48, 85) | 75 (56, 96) | <0.001 | 65 (48, 85) | 74 (56, 96) | <0.001 |

| MMSE | 24 (6, 30) | 23 (16, 29) | 0.043 | 24 (7, 30) | 23 (16, 26) | 0.06 |

| CDR sum of boxes | 3.0 (0.0, 18.0) | 4.5 (1.5, 10.0) | <0.001 | 3.0 (0.0, 18.0) | 4.5 (1.5, 10.0) | <0.001 |

| Aβ SUVRs | ||||||

| PiB | 2.38 (1.29, 3.53) | 2.40 (1.50, 3.53) | ||||

| Florbetapir | 1.44 (0.84, 1.80) | 1.45 (1.11, 1.80) | ||||

Data shown are n (%) or median (range). APOE = apolipoprotein E; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating scale; SUVR = standard uptake value ratio; PiB = Pittsburgh Compound B.

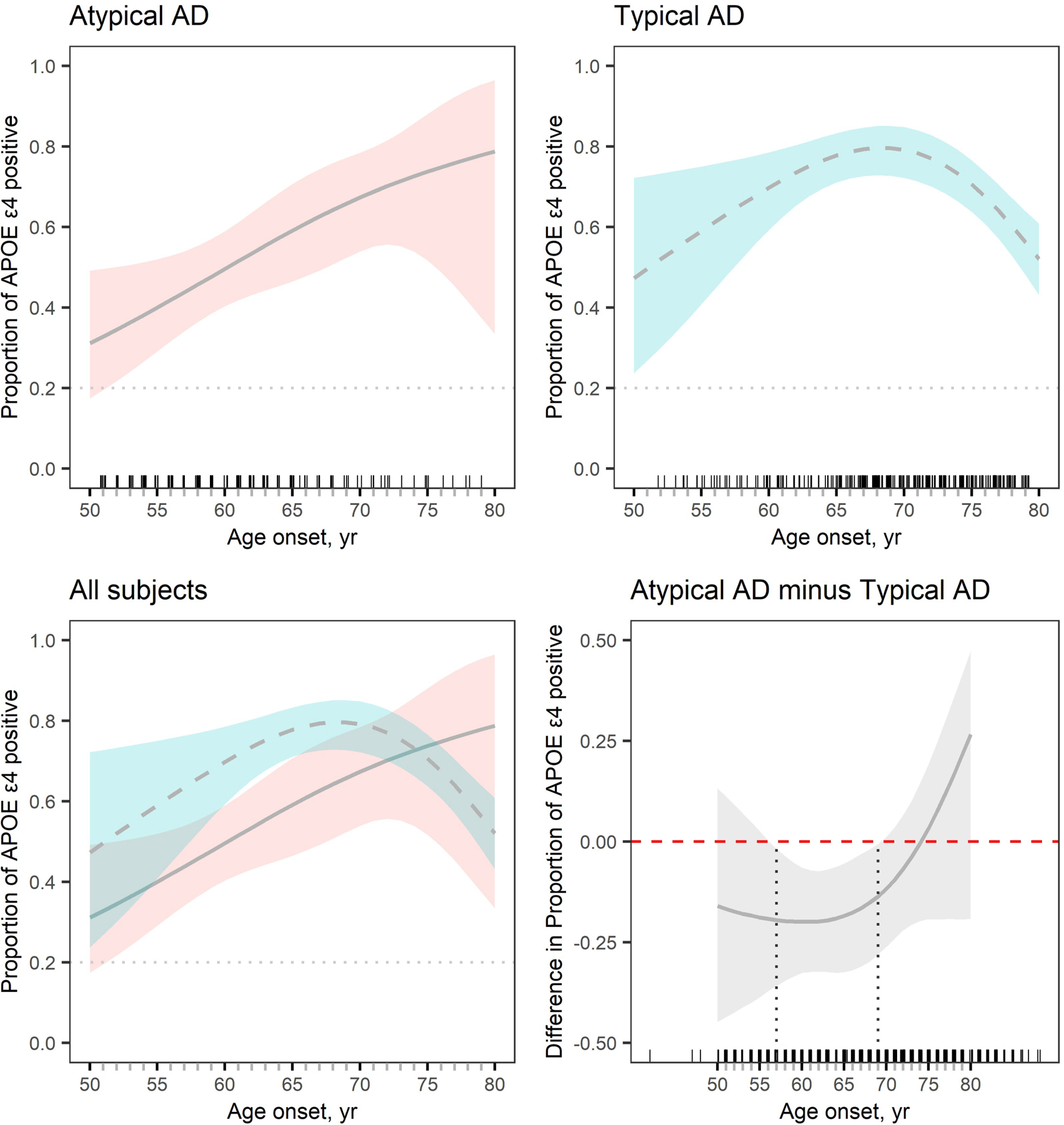

3.2. APOE ε4 frequency by age at onset

Based on a likelihood ratio test, APOE ε4 frequency differed significantly by age between atypical and typical AD (p=0.023). Specifically, the frequency of APOE ε4 carriers steadily increased with age at onset in atypical AD but showed a bell-shaped curve in typical AD where highest frequencies were observed between the onset ages of 65 and 70 years (Figure 1, Supplementary Material). Typical AD showed significantly higher frequencies of APOE ε4 carriers compared to atypical AD between the onset ages of 57 and 69 years. No significant differences in APOE ε4 frequency were observed between the cohorts in patients younger than 57 or in patients older than 69 years (Figure 1, Supplementary Material). These age at onset relationships remained the same when the analysis was limited to only patients with positive Aβ-PET.

Figure 1. Plots of APOE ε4 carrier frequency by age at onset in atypical AD and typical AD.

The estimated proportion of APOE ε4 carriers is plotted with 95% percentile confidence intervals. Plots are shown for atypical AD (top left) and typical AD (top right) and then these plots are overlaid in the bottom left panel. The bottom right plot shows the difference in proportion of APOE ε4 carriers between atypical AD and typical AD by age at onset. Proportions differ significantly between groups at an alpha level of 0.05 when the 95% confidence interval does not cross the 0 line, i.e. between the ages of 57 and 69 years. Small tick marks above the x-axis reflect individual patient points to demonstrate the density of data across the age at onset spectrum. The grey dotted line in the top plots and bottom left plot represents the APOE ε4 frequency (20%) in a control population. This frequency was calculated from 241 ADNI participants that were cognitively unimpaired at their last visit and all visits prior to that visit, had an available APOE genotype, and had a normal amyloid-PET scan.

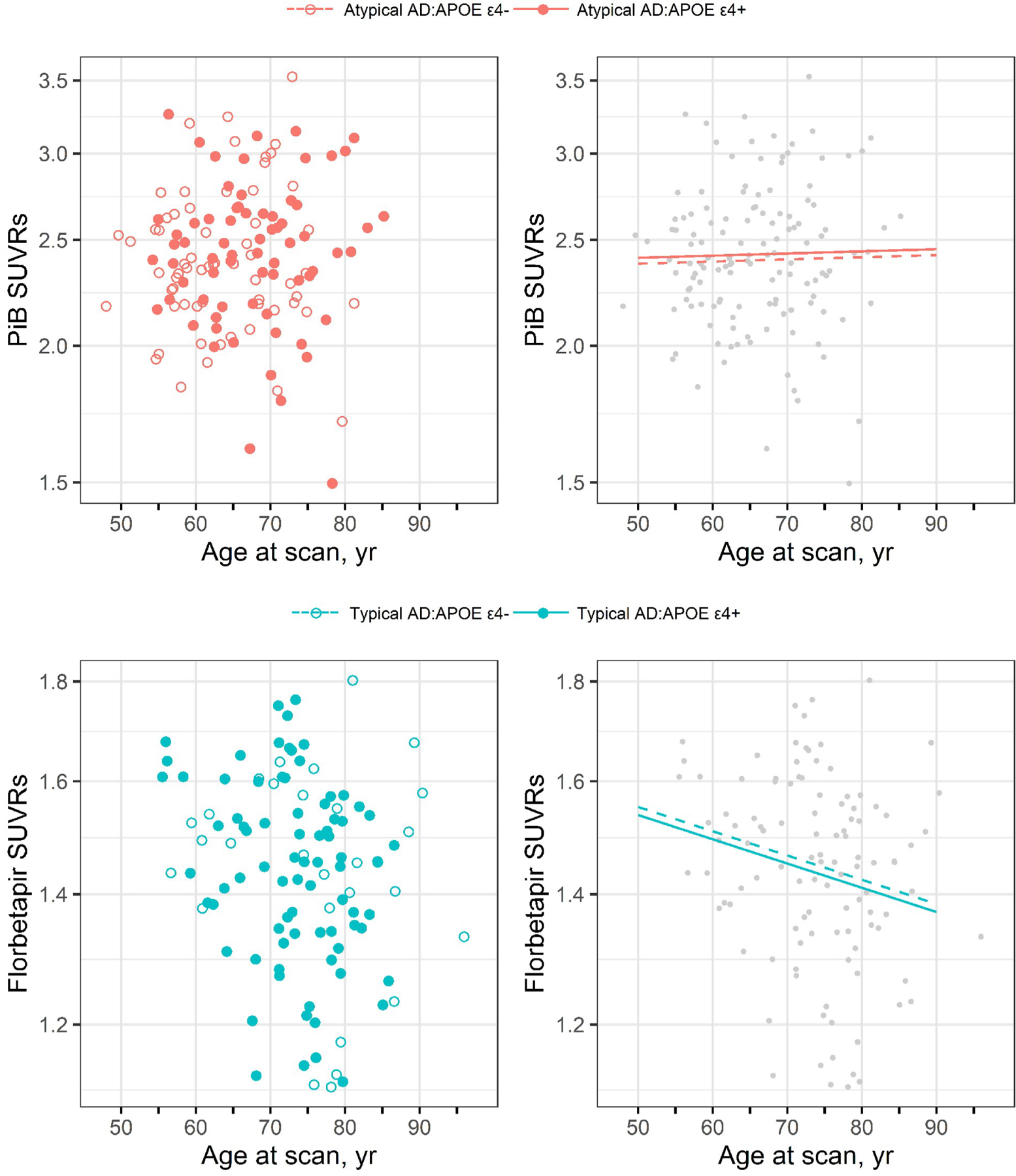

3.3. Aβ burden by age and APOE ε4

Figure 2 shows plots illustrating the relationship between Aβ PET SUVR and age at scan for atypical AD and typical AD, split by APOE ε4 status. In atypical AD, Aβ SUVR stays relatively flat with increasing age with no differences observed according to APOE ε4 status. In typical AD, Aβ SUVR declines with increasing age with again no difference in burden observed according to APOE ε4 status. Age was significantly associated with Aβ SUVR in typical AD in the regression analyses (Table 2). There was no difference in the effect of APOE ε4 on Aβ SUVR between the atypical and typical AD models (p=0.55).

Figure 2. Plots of Aβ SUVR versus age for atypical AD and typical AD by APOE ε4 status.

The top row shows the results for atypical AD using Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) PET while the bottom row shows the results for typical AD using florbetapir PET. The scatter-plots on the left show log-transformed Aβ SUVR versus age at scan separately by APOE ε4 status. The plots on the right show the estimated mean in the APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers based on a model without an interaction between age at scan and APOE.

Table 2.

Regression analysis predicting log-transformed Aβ SUVRs

| PiB SUVRs in atypical AD |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-way interaction |

No interaction |

|||||

| Est (95% CIs) | Standard Error | P | Est (95% CIs) | Standard Error | P | |

| Intercepts | 0.875 (0.825, 0.926) | 0.0256 | <0.001 | 0.875 (0.831, 0.920) | 0.0223 | <0.001 |

| Age at scan | 0.000 (−0.005, 0.006) | 0.0026 | 0.87 | 0.000 (−0.003, 0.004) | 0.0018 | 0.80 |

| APOE ε4 carrier | 0.012 (−0.051, 0.075) | 0.0319 | 0.70 | 0.012 (−0.042, 0.067) | 0.0274 | 0.65 |

| Age x APOE ε4 | 0.000 (−0.007, 0.007) | 0.0035 | >0.99 | |||

| Florbetapir SUVRs in typical AD |

||||||

| 2-way interaction |

No interaction |

|||||

| Est (95% CIs) | Standard Error | P | Est (95% CIs) | Standard Error | P | |

|

| ||||||

| Intercepts | 0.375 (0.326, 0.423) | 0.0245 | <0.001 | 0.382 (0.338, 0.427) | 0.0225 | <0.001 |

| Age at scan | −0.002 (−0.006, 0.003) | 0.0021 | 0.45 | −0.003 (−0.006, −0.000) | 0.0013 | 0.034 |

| APOE ε4 carrier | 0.001 (−0.055, 0.056) | 0.0280 | 0.98 | −0.010 (−0.058, 0.040) | 0.0247 | 0.70 |

| Age x APOE ε4 | −0.002 (−0.008, 0.003) | 0.0027 | 0.43 | |||

APOE = apolipoprotein E; SUVR = standard uptake value ratio

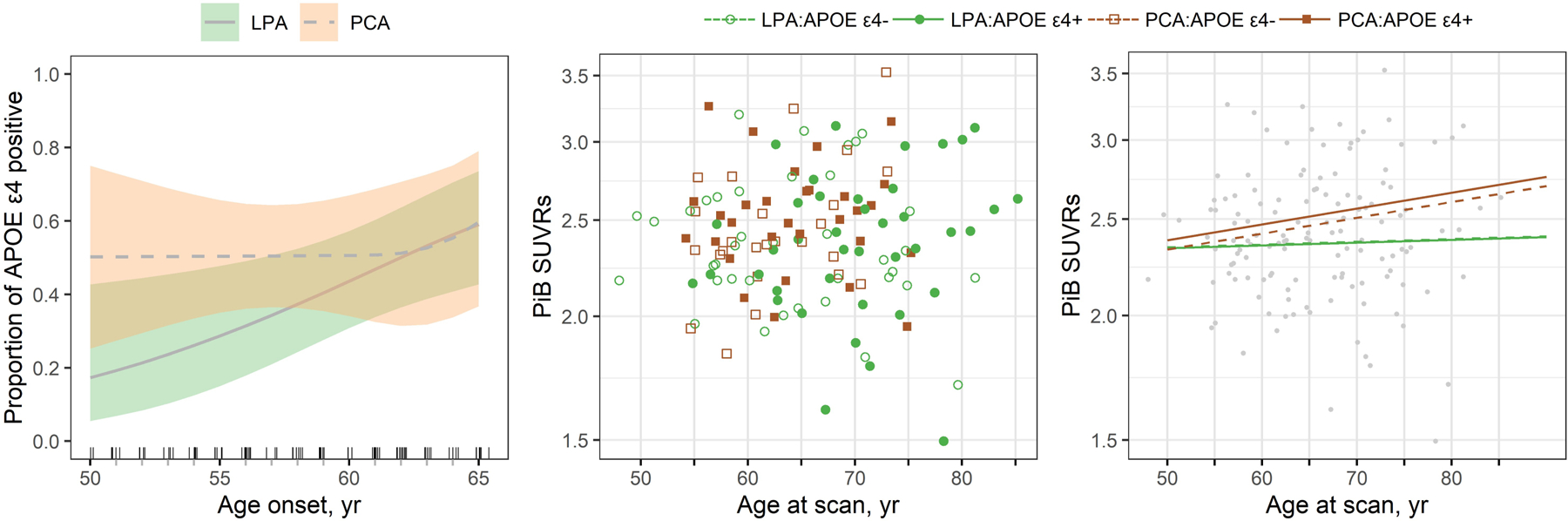

3.4. Influence of atypical AD clinical phenotype

LPA and PCA did not differ in APOE ε4 frequency and Aβ SUVR, although the PCA patients were about five years younger at onset and at PET (Table 3). We did not find any evidence that the relationship between age at onset and APOE ε4 frequency differed in atypical AD when including clinical phenotype (p=0.26) (Figure 3). Furthermore, we found no evidence for differences between PCA and LPA in the relationship between Aβ SUVR and age at scan, with neither group showing an effect of APOE ε4 status on these relationships (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Atypical AD patient characteristics

| LPA (n=81) | PCA (n=57) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 45 (56%) | 37 (65%) | 0.30 |

| APOE ε4 carrier, n (%) | 41 (51%) | 31 (54%) | 0.73 |

| ε2/ε2 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| ε2/ε3 | 4 (5%) | 3 (5%) | |

| ε2/ε4 | 3 (4%) | 3 (5%) | |

| ε3/ε3 | 36 (44%) | 23 (40%) | |

| ε3/ε4 | 31 (38%) | 22 (39%) | |

| ε4/ε4 | 7 (9%) | 6 (11%) | |

| Age at onset, yr | 64 (42, 80) | 59 (48, 74) | <0.001 |

| Age at PET, yr | 68 (48, 85) | 63 (54, 75) | 0.007 |

| MMSE | 24 (6, 30) | 24 (7, 30) | 0.18 |

| CDR sum of boxes | 3.0 (0.0, 13.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 18.0) | 0.35 |

| Aβ SUVRs | 2.34 (1.29, 3.20) | 2.42 (1.42, 3.53) | 0.15 |

Data shown are n (%) or median (range). APOE = apolipoprotein E; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating scale; SUVR = standard uptake value ratio

Figure 3. Plots showing the relationships between APOE ε4 status, age at onset and Aβ SUVR in LPA and PCA.

The first panel shows the estimated proportion of APOE ε4 carriers by age at onset for LPA and PCA with shaded regions indicating 95% CIs. The second panel shows a scatter plot of log-transformed Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) Aβ SUVR versus age at scan with colors and symbols differentiating phenotype and APOE ε4 status. The third panel shows the estimated mean Aβ SUVR for the four subgroups.

4. DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that frequency of the APOE ε4 genotype differs across atypical and typical clinical presentations of AD, although APOE ε4 frequency was highly dependent on age of onset with significant differences concentrated in patients between the ages of 57 and 69 years old. There was no evidence that APOE ε4 status was associated with higher Aβ PET uptake in either group.

Our findings using the ADNI cohort showed that the frequency of APOE ε4 carriers in typical AD increases with increasing age of onset up until approximately 70 years but then declines with increasing age at onset after that. Previous studies have found a similar bell-shaped relationship between age at onset and APOE ε4 frequency in typical Alzheimer’s dementia, with APOE ε4 carriers most common in patients with an onset in the 60–69 age decade and less common after age 70 years in one study (Davidson et al., 2007) and most common in the 60–79 onset age range in another study (Bickeboller et al., 1997). The effects of the APOE ε4 allele on AD risk has also been shown to reduce after age 70 years in one study (Farrer et al., 1997), and after age 75 in another (Liu and Caselli, 2018). It has also been shown that the effects of APOE genotype on progression from normal cognition to MCI or AD peak between age 70 and 75 years (Bonham et al., 2016). This bell-shaped relationship suggests an increase in the frequency of Alzheimer’s dementia not associated with the APOE ε4 allele in older patients. Interestingly, we did not observe the same bell-shaped curve in atypical AD; instead, the frequency of APOE ε4 carriers continued to increase with increasing age at onset, suggesting that APOE risk may increase with increasing onset age in atypical AD. There was perhaps a slight flattening of the slope over age 70 but frequencies continued to rise until age 80 years. However, data on atypical AD patients with age at onset over 70 years was relatively sparse so some caution is needed in interpreting trends in these older ages. We only observed a significant difference in APOE ε4 genotype between clinical groups, with a higher APOE ε4 frequency in typical AD, in patients with an age at onset between 57 and 69 years. There was a tendency for atypical AD to have a lower frequency in patients with onset age under age 57 and a higher frequency in patients with an onset age over 75, although no significant differences were observed; possibly due to a lack of power at the age extremes. Data in the typical AD group was sparse at these low onset ages. Nevertheless, differences in age at onset likely contributed to discrepancies across previous studies in reported APOE ε4 frequencies in atypical AD cohorts, and in studies that compared typical and atypical AD.

Previous studies have associated the APOE ε4 genotype with greater medial temporal and less cortical atrophy and tau deposition on PET in AD (La Joie et al., 2021; Mattsson et al., 2018; Therriault et al., 2020), which fits with findings of lower APOE ε4 frequencies in atypical AD patients who show more cortical atrophy and tau uptake and a relative sparing of the medial temporal lobe compared to typical AD. However, our findings suggest that the relationship between APOE and clinical phenotype may be more complicated than this and depend highly on age at onset. Age at onset also strongly influences the neuroimaging outcomes in AD. Typical AD patients in the 60–70 age range show the expected imaging characteristics of AD, including hippocampal atrophy and tau deposition measured on PET, while those older than 70 years show hippocampal atrophy but less tau deposition on PET suggesting contributions from other pathologies, such as TDP-43, to medial temporal atrophy in older patients (Josephs et al., 2020). It is possible that other pathologies may contribute somewhat to the lower APOE ε4 frequency in the older patients, i.e. that older-onset Alzheimer’s dementia is less driven by APOE ε4 and more driven by the presence of other age-associated pathologies that target the medial temporal lobe, and may help explain the differences observed between typical and atypical AD. This fits with the fact that amyloid PET burden decreases with age in typical AD. The story is, however, likely more complicated than this given that the risk of age-associated pathologies such as TDP-43 and Lewy bodies have both been shown to be related to APOE (Dickson et al., 2018; Wennberg et al., 2018). While TDP-43 is uncommon in atypical AD (Sahoo et al., 2018), Lewy bodies are a relatively common co-pathology (Buciuc et al., 2020). Younger age at onset is associated with greater cortical atrophy and tau uptake in both atypical and typical AD (Josephs et al., 2020; Whitwell et al., 2019), which concurs with the lower APOE ε4 frequencies in young onset age in both groups. Future studies will be needed to determine the contributions of other pathologies and to determine the relationship between APOE ε4 genotype, neuroimaging signatures and age at onset across clinical phenotypes in AD.

There was no evidence that APOE ε4 status influenced the degree of Aβ deposition in either cohort across the age spectrum. Some previous studies have similarly found no relationship between APOE ε4 status and burden of Aβ PET or CSF Aβ1–42 in Alzheimer’s dementia cohorts (Fleisher et al., 2013; Nitsch et al., 1995; Rowe et al., 2010). Other studies have identified relationships, although the direction of the relationship in PET studies has varied with some studies finding greater Aβ PET burden in APOE ε4 positive patients (Drzezga et al., 2009; Murphy et al., 2013; Vemuri et al., 2010) and others finding greater burden in APOE ε4 negative patients (Baek et al., 2020; Lehmann et al., 2014; Ossenkoppele et al., 2013). The explanation for these discrepancies in the literature is unclear. Cohorts in previous studies may have been heterogeneous in terms of AD clinical phenotype and vary in age and disease severity, although our data does not suggest different relationships in these clinical phenotypes. Some of the previous studies included Aβ-negative individuals which could have influenced the findings and helped drive the associations (Fleisher et al., 2013). In contrast to the heterogeneous results in Alzheimer’s dementia populations, studies concur that APOE ε4 genotype is associated with Aβ in undemented populations (Jack et al., 2015; Lim et al., 2017; Morris et al., 2010; Reiman et al., 2009; Rowe et al., 2010). It is possible that APOE has an effect early in the disease, increasing the risk of developing AD and hence Aβ deposition, but does not determine the burden of Aβ in later stages of the disease. Alternatively, Aβ-PET burden may have already plateaued in these advanced disease stages (Jack et al., 2013).

We found that the relationships of APOE ε4 were similar in the two different clinical phenotypes of atypical AD. We did not find evidence for any differences in the relationship between APOE ε4 frequency and age at onset between LPA and PCA, although PCA seemed to have a flat slope while the frequency in LPA appeared to trend up. We also did not find any evidence that Aβ SUVR differed between PCA and LPA at any age. The only clear difference observed between the groups was that the LPA patients were about five years older at onset and PET than the PCA patients. In fact, none of our PCA patients were older than 75 years at the time of PET. Hence, the LPA patients would have contributed more to our understanding of APOE genotype and Aβ SUVR in atypical AD at the older onset ages. Both groups were, however, much younger at onset than the typical AD group, as one would expect.

This study utilized a large cohort of both atypical and typical AD patients allowing us to model the relationships between APOE genotype, age at onset and phenotype. The atypical AD cohort was also well characterized clinically and all patients had undergone standardized neurological batteries by one of two behavioral neurologists. Limitations of the study include the fact that the ADNI cohort did not have the same clinical variables available for comparison to the atypical AD cohort as the data comes from multiple different sites. The distributions of age at onset of the two cohorts also differed which limited power to compare the cohorts at very young and very old onset ages. Given that both cohorts had a clinical diagnosis of dementia we lacked enough APOE ε2 carriers to assess potential differences in frequency of this protective allele.

5. CONCLUSION

The findings highlight the importance of age at onset and clinical phenotype in understanding the effects of APOE genotype in AD, and contribute to knowledge concerning the heterogeneity present in AD. A better understanding of this heterogeneity will be important to help better target patients for inclusion in clinical treatment trials, and to allow improved interpretation of neuroimaging, clinical and genetic findings across the age spectrum in AD.

Supplementary Material

6. FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01-AG50603 and R01-DC010367], and the Alzheimer’s Association [NIRG-12-242215]. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. The funder had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in writing the report, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

Publisher's Disclaimer: VERIFICATION

Publisher's Disclaimer: This work has not been published previously, is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, that its publication is approved by all authors and tacitly or explicitly by the responsible authorities where the work was carried out. If accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, including electronically without the written consent of the copyright-holder.

Declarations of interest

none.

REFERENCES

- Baek MS, Cho H, Lee HS, Lee JH, Ryu YH, Lyoo CH, 2020. Effect of APOE epsilon4 genotype on amyloid-beta and tau accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 12(1), 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasa M, Gelpi E, Antonell A, Rey MJ, Sanchez-Valle R, Molinuevo JL, Llado A, Neurological Tissue Bank/University of Barcelona/Hospital Clinic, N.T.B.U.B.H.C.C.G., 2011. Clinical features and APOE genotype of pathologically proven early-onset Alzheimer disease. Neurology 76(20), 1720–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickeboller H, Campion D, Brice A, Amouyel P, Hannequin D, Didierjean O, Penet C, Martin C, Perez-Tur J, Michon A, Dubois B, Ledoze F, Thomas-Anterion C, Pasquier F, Puel M, Demonet JF, Moreaud O, Babron MC, Meulien D, Guez D, Chartier-Harlin MC, Frebourg T, Agid Y, Martinez M, Clerget-Darpoux F, 1997. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: genotype-specific risks by age and sex. Am J Hum Genet 60(2), 439–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham LW, Geier EG, Fan CC, Leong JK, Besser L, Kukull WA, Kornak J, Andreassen OA, Schellenberg GD, Rosen HJ, Dillon WP, Hess CP, Miller BL, Dale AM, Desikan RS, Yokoyama JS, 2016. Age-dependent effects of APOE epsilon4 in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 3(9), 668–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buciuc M, Whitwell JL, Kasanuki K, Graff-Radford J, Machulda MM, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Lowe VJ, Graff-Radford NR, Rush BK, Franczak MB, Flanagan ME, Baker MC, Rademakers R, Ross OA, Ghetti BF, Parisi JE, Raghunathan A, Reichard RR, Bigio EH, Dickson DW, Josephs KA, 2020. Lewy Body Disease is a Contributor to Logopenic Progressive Aphasia Phenotype. Ann Neurol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo MM, Barber I, Lincoln SJ, Murray ME, Camsari GB, Khan QUA, Nguyen T, Ma L, Bisceglio GD, Crook JE, Younkin SG, Dickson DW, Boeve BF, Graff-Radford NR, Morgan K, Ertekin-Taner N, 2016. Evaluating pathogenic dementia variants in posterior cortical atrophy. Neurobiol Aging 37, 38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo MM, Khan Q, Murray ME, Krishnan S, Aakre J, Pankratz VS, Nguyen T, Ma L, Bisceglio G, Petersen RC, Younkin SG, Dickson DW, Boeve BF, Graff-Radford NR, Ertekin-Taner N, 2014. Late-onset Alzheimer disease genetic variants in posterior cortical atrophy and posterior AD. Neurology 82(16), 1455–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano JM, Kim J, Stewart FR, Jiang H, DeMattos RB, Patterson BW, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Mawuenyega KG, Cruchaga C, Goate AM, Bales KR, Paul SM, Bateman RJ, Holtzman DM, 2011. Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-beta peptide clearance. Sci Transl Med 3(89), 89ra57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clogg CC, Petkova E, Haritou A, 1995. Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. American journal of sociology 100(5), 1261–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Corder EH, Saunders AM, Risch NJ, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC Jr., Rimmler JB, Locke PA, Conneally PM, Schmader KE, et al. , 1994. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E type 2 allele for late onset Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet 7(2), 180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, 1993. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 261(5123), 921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook R, Hardy J, Duff K, 1994. Single-day apolipoprotein E genotyping. J Neurosci Methods 53(2), 125–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutch SJ, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, Murray M, Snowden JS, van der Flier WM, Dickerson BC, Vandenberghe R, Ahmed S, Bak TH, Boeve BF, Butler C, Cappa SF, Ceccaldi M, de Souza LC, Dubois B, Felician O, Galasko D, Graff-Radford J, Graff-Radford NR, Hof PR, Krolak-Salmon P, Lehmann M, Magnin E, Mendez MF, Nestor PJ, Onyike CU, Pelak VS, Pijnenburg Y, Primativo S, Rossor MN, Ryan NS, Scheltens P, Shakespeare TJ, Suarez Gonzalez A, Tang-Wai DF, Yong KXX, Carrillo M, Fox NC, Alzheimer’s Association, I.A.A.s.D., Associated Syndromes Professional Interest, A., 2017. Consensus classification of posterior cortical atrophy. Alzheimers Dement 13(8), 870–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson Y, Gibbons L, Pritchard A, Hardicre J, Wren J, Stopford C, Julien C, Thompson J, Payton A, Pickering-Brown SM, Pendleton N, Horan MA, Burns A, Purandare N, Lendon CL, Neary D, Snowden JS, Mann DM, 2007. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele frequency and age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 23(1), 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Heckman MG, Murray ME, Soto AI, Walton RL, Diehl NN, van Gerpen JA, Uitti RJ, Wszolek ZK, Ertekin-Taner N, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Graff-Radford NR, Boeve BF, Bu G, Ferman TJ, Ross OA, 2018. APOE epsilon4 is associated with severity of Lewy body pathology independent of Alzheimer pathology. Neurology 91(12), e1182–e1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drzezga A, Grimmer T, Henriksen G, Muhlau M, Perneczky R, Miederer I, Praus C, Sorg C, Wohlschlager A, Riemenschneider M, Wester HJ, Foerstl H, Schwaiger M, Kurz A, 2009. Effect of APOE genotype on amyloid plaque load and gray matter volume in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 72(17), 1487–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, Myers RH, Pericak-Vance MA, Risch N, van Duijn CM, 1997. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA 278(16), 1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisher AS, Chen K, Liu X, Ayutyanont N, Roontiva A, Thiyyagura P, Protas H, Joshi AD, Sabbagh M, Sadowsky CH, Sperling RA, Clark CM, Mintun MA, Pontecorvo MJ, Coleman RE, Doraiswamy PM, Johnson KA, Carpenter AP, Skovronsky DM, Reiman EM, 2013. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 and age effects on florbetapir positron emission tomography in healthy aging and Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging 34(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge T, Sabuncu MR, Smoller JW, Sperling RA, Mormino EC, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging, I., 2018. Dissociable influences of APOE epsilon4 and polygenic risk of AD dementia on amyloid and cognition. Neurology 90(18), e1605–e1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, Ogar JM, Rohrer JD, Black S, Boeve BF, Manes F, Dronkers NF, Vandenberghe R, Rascovsky K, Patterson K, Miller BL, Knopman DS, Hodges JR, Mesulam MM, Grossman M, 2011. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76(11), 1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE, 2001. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr., Wiste HJ, Lesnick TG, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Vemuri P, Pankratz VS, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Mielke MM, Lowe VJ, Boeve BF, Petersen RC, 2013. Brain beta-amyloid load approaches a plateau. Neurology 80(10), 890–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr., Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Vemuri P, Mielke MM, Lowe V, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Machulda MM, Gregg BE, Pankratz VS, Rocca WA, Petersen RC, 2015. Age, Sex, and APOE epsilon4 Effects on Memory, Brain Structure, and beta-Amyloid Across the Adult Life Span. JAMA Neurol 72(5), 511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr., Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Jones DT, Kantarci K, Machulda MM, Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Vemuri P, Reyes DA, Petersen RC, 2017. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 13(3), 205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagust WJ, Landau SM, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Chen K, Mathis CA, Price JC, Foster NL, Wang AY, 2015. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 2 PET Core: 2015. Alzheimers Dement 11(7), 757–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr., Whitwell JL, 2014. APOE epsilon4 influences beta-amyloid deposition in primary progressive aphasia and speech apraxia. Alzheimers Dement 10(6), 630–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Tosakulwong N, Graff-Radford J, Weigand SD, Buciuc M, Machulda MM, Jones DT, Schwarz CG, Senjem ML, Ertekin-Taner N, Kantarci K, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Jack CR Jr., Petersen RC, Lowe VJ, Whitwell JL, 2020. MRI and flortaucipir relationships in Alzheimer’s phenotypes are heterogeneous. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 7(5), 707–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Joie R, Visani AV, Lesman-Segev OH, Baker SL, Edwards L, Iaccarino L, Soleimani-Meigooni DN, Mellinger T, Janabi M, Miller ZA, Perry DC, Pham J, Strom A, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Jagust WJ, Rabinovici GD, 2021. Association of APOE4 and clinical variability in Alzheimer disease with the pattern of tau- and amyloid-PET. Neurology 96 (5): e650–e661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau SM, Lu M, Joshi AD, Pontecorvo M, Mintun MA, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Jagust WJ, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging, I., 2013. Comparing positron emission tomography imaging and cerebrospinal fluid measurements of beta-amyloid. Ann Neurol 74(6), 826–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann M, Ghosh PM, Madison C, Karydas A, Coppola G, O’Neil JP, Huang Y, Miller BL, Jagust WJ, Rabinovici GD, 2014. Greater medial temporal hypometabolism and lower cortical amyloid burden in ApoE4-positive AD patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 85(3), 266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann M, Ghosh PM, Madison C, Laforce R, Corbetta-Rastelli C, Weiner MW, Greicius MD, Seeley WW, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Jagust WJ, Rabinovici GD, 2013. Diverging patterns of amyloid deposition and hypometabolism in clinical variants of probable Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 136, 844–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YY, Mormino EC, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging, I., 2017. APOE genotype and early beta-amyloid accumulation in older adults without dementia. Neurology 89(10), 1028–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Caselli RJ, 2018. Age stratification corrects bias in estimated hazard of APOE genotype for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 4, 602–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson N, Ossenkoppele R, Smith R, Strandberg O, Ohlsson T, Jogi J, Palmqvist S, Stomrud E, Hansson O, 2018. Greater tau load and reduced cortical thickness in APOE epsilon4-negative Alzheimer’s disease: a cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther 10(1), 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM, 1984. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34(7), 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr., Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH, 2011. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7(3), 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Johnson N, Grujic Z, Weintraub S, 1997. Apolipoprotein E genotypes in primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 49(1), 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MR, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Steffens DC, Wyse BW, Breitner JC, 1998. APOE genotype predicts when--not whether--one is predisposed to develop Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet 19(4), 321–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Goate AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA, 2010. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol 67(1), 122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KR, Landau SM, Choudhury KR, Hostage CA, Shpanskaya KS, Sair HI, Petrella JR, Wong TZ, Doraiswamy PM, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging, I., 2013. Mapping the effects of ApoE4, age and cognitive status on 18F-florbetapir PET measured regional cortical patterns of beta-amyloid density and growth. Neuroimage 78, 474–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch RM, Rebeck GW, Deng M, Richardson UI, Tennis M, Schenk DB, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Lieberburg I, Wurtman RJ, Hyman BT, et al. , 1995. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid beta-protein in Alzheimer’s disease: inverse correlation with severity of dementia and effect of apolipoprotein E genotype. Ann Neurol 37(4), 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossenkoppele R, van der Flier WM, Zwan MD, Adriaanse SF, Boellaard R, Windhorst AD, Barkhof F, Lammertsma AA, Scheltens P, van Berckel BN, 2013. Differential effect of APOE genotype on amyloid load and glucose metabolism in AD dementia. Neurology 80(4), 359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, Jack CR Jr., Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW, 2010. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology 74(3), 201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JS, Da Re F, Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Vaishnavi SN, Xie SX, Lee EB, Cook PA, Gee JC, Shaw LM, 2019. Longitudinal progression of grey matter atrophy in non-amnestic Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 142(6), 1701–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince JA, Zetterberg H, Andreasen N, Marcusson J, Blennow K, 2004. APOE epsilon4 allele is associated with reduced cerebrospinal fluid levels of Abeta42. Neurology 62(11), 2116–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman EM, Chen K, Liu X, Bandy D, Yu M, Lee W, Ayutyanont N, Keppler J, Reeder SA, Langbaum JB, Alexander GE, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Aizenstein HJ, DeKosky ST, Caselli RJ, 2009. Fibrillar amyloid-beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(16), 6820–6825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalski EJ, Rademaker A, Harrison TM, Helenowski I, Johnson N, Bigio E, Mishra M, Weintraub S, Mesulam MM, 2011. ApoE E4 is a Susceptibility Factor in Amnestic But Not Aphasic Dementias. Alz Dis Assoc Dis 25(2), 159–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CC, Ellis KA, Rimajova M, Bourgeat P, Pike KE, Jones G, Fripp J, Tochon-Danguy H, Morandeau L, O’Keefe G, Price R, Raniga P, Robins P, Acosta O, Lenzo N, Szoeke C, Salvado O, Head R, Martins R, Masters CL, Ames D, Villemagne VL, 2010. Amyloid imaging results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. Neurobiol Aging 31(8), 1275–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo A, Bejanin A, Murray ME, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Serie AM, Senjem ML, Machulda MM, Parisi JE, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Dickson DW, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, 2018. TDP-43 and Alzheimer’s Disease Pathologic Subtype in Non-Amnestic Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 64(4), 1227–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott JM, Ridha BH, Crutch SJ, Healy DG, Uphill JB, Warrington EK, Rossor MN, Fox NC, 2006. Apolipoprotein e genotype modifies the phenotype of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 63(1), 155–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Schmechel D, Pericak-Vance M, Enghild J, Salvesen GS, Roses AD, 1993a. Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90(5), 1977–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter WJ, Weisgraber KH, Huang DY, Dong LM, Salvesen GS, Pericak-Vance M, Schmechel D, Saunders AM, Goldgaber D, Roses AD, 1993b. Binding of human apolipoprotein E to synthetic amyloid beta peptide: isoform-specific effects and implications for late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90(17), 8098–8102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang-Wai DF, Graff-Radford NR, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Crook R, Caselli RJ, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, 2004. Clinical, genetic, and neuropathologic characteristics of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology 63(7), 1168–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapiola T, Pirttila T, Mehta PD, Alafuzofff I, Lehtovirta M, Soininen H, 2000. Relationship between apoE genotype and CSF beta-amyloid (1–42) and tau in patients with probable and definite Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 21(5), 735–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therriault J, Benedet AL, Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, Chamoun M, Savard M, Thomas E, Kang MS, Lussier F, Tissot C, Parsons M, Qureshi MNI, Vitali P, Massarweh G, Soucy JP, Rej S, Saha-Chaudhuri P, Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P, 2020. Association of Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 With Medial Temporal Tau Independent of Amyloid-beta. JAMA Neurol 77(4), 470–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier WM, Schoonenboom SN, Pijnenburg YA, Fox NC, Scheltens P, 2006. The effect of APOE genotype on clinical phenotype in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 67(3), 526–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Aisen PS, Weiner M, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging, I., 2010. Effect of apolipoprotein E on biomarkers of amyloid load and neuronal pathology in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 67(3), 308–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg AM, Tosakulwong N, Lesnick TG, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, Liesinger AM, Petrucelli L, Boeve BF, Parisi JE, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Dickson DW, Josephs KA, 2018. Association of Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 With Transactive Response DNA-Binding Protein 43. JAMA Neurol 75(11), 1347–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Dickson DW, Murray ME, Weigand SD, Tosakulwong N, Senjem ML, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Parisi JE, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr., Josephs KA, 2012. Neuroimaging correlates of pathologically defined subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease: a case-control study. Lancet neurology 11(10), 868–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Martin P, Graff-Radford J, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Schwarz CG, Weigand SD, Spychalla AJ, Drubach DA, Jack CR Jr., Lowe VJ, Josephs KA, 2019. The role of age on tau PET uptake and gray matter atrophy in atypical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 15(5), 675–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbinatti CV, Wozniak DF, Cirrito J, Cam JA, Osaka H, Bales KR, Zhuo M, Paul SM, Holtzman DM, Bu G, 2004. Increased soluble amyloid-beta peptide and memory deficits in amyloid model mice overexpressing the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101(4), 1075–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.