Abstract

Blast disease incited by Magnaporthe oryzae is a major threat to sustain rice production in all rice growing nations. The pathogen is widely distributed in all rice paddies and displays rapid aerial transmissions, and seed-borne latent infection. In order to understand the genetic variability, host specificity, and molecular basis of the pathogenicity-associated traits, the whole genome of rice infecting Magnaporthe oryzae (Strain RMg_Dl) was sequenced using the Illumina and PacBio (RSII compatible) platforms. The high-throughput hybrid assembly of short and long reads resulted in a total of 375 scaffolds with a genome size of 42.43 Mb. Furthermore, comparative genome analysis revealed 99% average nucleotide identity (ANI) with other oryzae genomes and 83% against M. grisea, and 73% against M. poe genomes. The gene calling identified 10,553 genes with 10,539 protein-coding sequences. Among the detected transposable elements, the LTR/Gypsy and Type LINE showed high occurrence. The InterProScan of predicted protein sequences revealed that 97% protein family (PFAM), 98% superfamily, and 95% CDD were shared among RMg_Dl and reference 70-15 genome, respectively. Additionally, 550 CAZymes with high GH family content/distribution and cell wall degrading enzymes (CWDE) such endoglucanase, beta-glucosidase, and pectate lyase were also deciphered in RMg_Dl. The prevalence of virulence factors determination revealed that 51 different VFs were found in the genome. The biochemical pathway such as starch and sucrose metabolism, mTOR signaling, cAMP signaling, MAPK signaling pathways related genes were identified in the genome. The 49,065 SNPs, 3267 insertions and 3611 deletions were detected, and majority of these varinats were located on downstream and upstream region. Taken together, the generated information will be useful to develop a specific marker for diagnosis, pathogen surveillance and tracking, molecular taxonomy, and species delineation which ultimately leads to device improved management strategies for blast disease.

Subject terms: Comparative genomics, Genomics, Next-generation sequencing

Introduction

Since the traditional times, both cereal and cereal products act as pre-eminent and substantial carbohydrate food resources for much of the human population, especially in Asian countries1,2. Among the pre-harvest production constraints, the global cultivation of many cereals including rice and pearl millet is mostly affected by a blast disease-causing filamentous ascomycete fungus, Magnaporthe (Hebert) Barr (anamorph: Pyricularia)3. This devastating hemibiotrophic pathogen belongs to the family Magnaporthaceae and is of principal concern due to the wide distribution, rapid aerial transmissions, seed-borne latent infection, and associated yield losses2,4,5. Morphologically, it causes white, bluish, or greyish water-soaked lesions in all foliar parts such as grain, leaf, neck, collar, nodes, and even panicles4. The fungus Magnaporthe sp. propagates via the generation of asexual spores (conidia) that disseminate the blast disease on cereal hosts6,7.

Out of all reported species belonging to the genus Magnaporthe, both Magnaporthe oryzae (Anamorph: Pyricularia oryzae) and Magnaporthe grisea (Anamorph: Pyricularia grisea) have emerged as forage and grain production affecting pathogen that annually contributes to the substantial losses of grains3,4,8. In order to control the spread and minimize the associated losses with the blast, farmers depend largely on resistant host cultivars, and application of fungicides especially tricyclazole9. However, these measures seem inadequate, and inefficient in blast-endemic regions because of related cost, unstable host resistance, the emergence of new pathotypes, toxic nature of the employed agrochemicals, and chemical residues on produced grains. Hence, the global sustainability of food is becoming a more challenging factor regarding the fast growth of the global population1,4,10.

Due to the recent advancements in molecular techniques, genes expressed by pathogens (M. oryzae and M. grisea) for the efficient invasion, colonization, and ultimate destruction of various monocot hosts especially the rice have been characterized10. Given that both pathogenic species uniquely attack their host plants, in depth insights into underlying biological pathways and associated mechanisms are still limited with spatial concern to signaling pathways, virulence factors, and carbohydrate-active enzymes. Moreover, the detected genes or proteins can be utilized as potential targets for marker development to screening the pathogen and fungicides through in silico approach11,12.

There is a wide range of pieces of literature available on fungal pathogen function and their pathogenesis. However, detailed comparative insights of tropical habitat rice blast fungus genes, family and biochemical pathways are still limited/unexplored. Therefore, to characterize such differences at the genomic and biochemical level, we performed the high-throughput whole-genome sequencing of cereal crop rice blast pathogen M. oryzae RMg_Dl followed by hybrid de novo genome assembly and comparative functional annotation. The genome-level analysis potentially deciphers the insights of each genes, their associated biochemical pathways; network for host–pathogen interaction; growth, evolutionary relationship, and virulence genes. The detailed insights of M. oryzae not only about host–pathogen interaction but also in-depth knowledge of pathogenicity mechanisms can be helpful for the effective disease management strategy.

Materials and methods

Data collection and sequencing

In this study, the used data sets were collected from13 (Bioproject accession PRJNA330763, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA330763), which reported the initial draft genome assembly of rice blast disease-causing Magnaporthe oryzae RMg_Dl. The sample processing and whole-genome analyses workflow is schematically depicted in Fig. 1. In summary, the pure fungus RMg_Dl was isolated followed by genomic DNA extraction, and subsequently, the quality and quantity assessment was done using agarose gel (0.8%) and Nanodrop spectrophotometer, respectively. The pair-end library was prepared was using Illumina TruSeq Nano DNA HT chemistry, and we also prepared the single-molecule real-time (SMRT) libraries compatible for generating long reads. The quantity and quality of both libraries were checked on Agilent Bioanalyzer using high sensitivity DNAchip. The Illumina platform quality passed libraries were sequenced on the HiSeq2500 sequencer with 125 × 2 pair-end chemistry. The SMRT-bell libraries were sequenced on PacBio-RSII using P6-C4 chemistry as described here13,14.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the WGS analysis of M. oryzae RMg_Dl.

Bioinformatic genome assembly and quality assessment

Initially, the reads were visualized in FastQC (V0.9.2) software to screen the quality of reads and identify the poor-quality reads for getting optimum read trimming and filtering parameters. Following this, the WGS reads were quality filtered to remove the adapter, poor sequences, and ambiguous bases to obtain high quality reads with filtering parameters such as reads with unknown nucleotides “N” larger than 5%, low-quality sequences (reads with more than 10% quality threshold (QV) < 20 Phred score) and reads shorter than 100 bases were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.3515. The RMg_Dl genome reads were assembled with a default setting using steps (1) PacBio read correction with LORDeC16 using Illumina reads, (2) corrected reads assembly with wtdbg2 assembler17, (3) gaps were filled with Long Read Gap closer18. Following genome assembly, the benchmark universal single-copy orthologs (BUSCO) was applied for the quantitative assessment of genome completeness against fungal lineage with gene model parameters19. Further, to determine the average nucleotide identity (ANI) between publically available genomes and generation of unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) tree, the OrthoANI calculator was utilized with default settings20.

Functional genome annotation of M. oryzae RMg_Dl

The functional annotation of assembled genome RMg_Dl was performed using the GenSAS web server21 which provided an integrated structured pipeline for repeat masking, ab initio gene prediction, homology-based gene function determination, protein family, and superfamily. Initially, the repeat masking was performed using Repeat Masker v4.0.722 against the fungi library with keeping GC content set at 50–52%. Further, Repeat Modeler v1.0.11 (http://www.repeatmasker.org/) was utilized for de novo repeat family identification and modeling. The assembled genome was submitted to AUGUSTUS v3.3.123 for genes and proteins prediction against the reference model Pyricularia grisea with both strand gene settings. The prediction of rRNA and tRNA was performed using RNAmmer v1.224 and tRNAscan-SE v2.025. The determination of simple sequence repeats (SSR) was performed with SSR Finder v1.021 with parameters of 5 count repeat for di, 4 for a tri, and 3 for tetra, Penta, and hexanucleotide SSR repeats.

The InterProScan (version5.48-83.0)26 of predicted protein sequences were performed to determine the occurrence of various protein families, conserved domains, superfamily, and gene ontology (GO) identifiers in the genome. Following, Bast2GO v5.2.527 was used for the mapping and annotations of GO identifiers to GO terms. The comparative carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes)28 were determined against the dbCAN2 database29 by using the HMMER model with a setting of e-value 0.00001. The virulence factors (VFs) were identified against a database for virulence factors (DFVF) rice blast database30 using DIAMOND (v0.9.26)31 protein aligner with parameters of max-target sequence alignment 1, ≥ 100 amino acid length, 90% identity, 60% query coverage, 60% subject coverage and e-value 0.00001. For prediction of potential effectors in the studied genomes, initially the signal peptide features were determined in the protein sequences and sequences were then submitted to EffectorP3.0 for prediction of effectors with default setting32. Further, OrthoVenn2 comparison was performed to decipher the common and unique effector in this genome as compared to other genomes33. In order to determine metabolic pathways, the predicted protein sequences were submitted to the KAAS webserver34 using search program GHOSTX against the reference pathway model Pyricularia grisea 70-1535. The presence of different promoters were identified using promoter2.036 with default settings, which detected 7021 promoters. For the comparative study, the used genome were GCA_000002495 (M. oryzae 70-15), GCA_002368485.1 (M. oryzae GUY11) and GCA_002924685.1 (M. oryzae WBKY11).

Analysis of variants and phyologenetic tree

For SNP determination, the high quality reads were mapped against M. oryzae 70-15 reference genome using burrows-wheeler alignment (BWA) maximal exact match (MEM) module37. The mapped reads were subjected for the removal of PCR duplicate reads using Mark duplicates of Picard tool (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Finally, variant calling was done using SAMtools38 package bcftools mpileup script with settings of phred quality score (Q) ≥ 25, minimum variant depth (DP) ≥ 25 and mapping quality ≥ 30. The identified SNPs were annotated to genomic region and various effects type using snpEff 5.039. For determination of genomes similarity, the comparative whole genome alignment based phylogenetic tree was generated using progressiveMauve aligner which consider gene rearrangement, gain and loss mechanism40. For alignment we used RMg_Dl and other 13 public genomes accession were GCA_002924685.1 (WBKY11), GCA_002021675.1 (Mo-nwi-55), GCA_000969745.1 (MG01), GCA_000832285.1 (B157), GCA_002218355.1 (H08-1c), GCA_001936435.1 (MG10), GCA_003991345.1 (10,100), GCA_000734215.1 (4603.4), GCA_000292605.1 (P131), GCA_002368485.1 (GUY11), GCA_000002495.2 (70-15), GCA_000475075.1 (HN19311), GCA_000805855.1 (98-06). The revised assembled genome was deposited in the NCBI database with GenBank assembly accession number GCA_001853415.3.

Results

Genome assembly, genes identification, and assessment

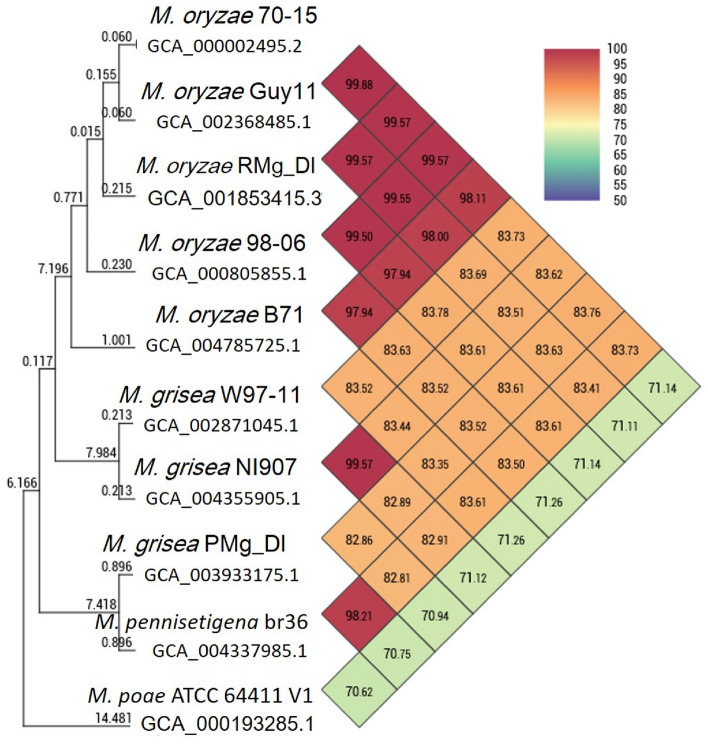

Using two of the prominent high-throughput whole-genome sequencing coupled with the hybrid assembly of short and long reads resulted in a total of 375 scaffolds with a genome size of 42.42 Mb (M. oryzae RMg_Dl). This genome-wide gene identification showed a total of 10,555 genes with 10,539 protein sequence features (Table 1). Additionally, comparative genome analysis revealed 99% average nucleotide identity (ANI) with other M. oryzae genomes and 83% against M. grisea, and 73% against M. poe genomes (Fig. 2). The quantitative genome assembly finish assessment showed that complete and single-copy BUSCO was 741 (97.76%) in M. oryzae (RMg_Dl) strain out of total 758 BUSCO genes. Although, we found thirteen missing BUSCO in M. oryzae RMg_Dl (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

Comparative statistics of the assembled whole genome of M. oryzae RMg_Dl.

| Features | M. oryzae RMg_Dl |

|---|---|

| Illumina HiSeq-2500 reads (base) | 65,731,812 pair-end (16.3 Gb) |

| PacBio-RSII reads (base) | 192,820 single end (1.5 Gb) |

| Genome SIZE | 42,437,481 |

| Number of scaffolds | 375 |

| Scaffold N50 | 524,210 |

| No of genes | 10,553 |

| Proteins | 10,539 |

| rRNA | 73 |

| tRNA | 259 |

| SSR | 18,830 |

| Virulence factors | 51 |

| CAZymes | 542 |

| Effectors | 603 |

Figure 2.

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) among various fungal Magnaporthe/Pyricularia genus

Determination of transposable elements and SSRs

Determination of SSRs in RMg_Dl genomes showed that 11 different transposon families with a total of 10,250 copy numbers in the genome. The repeat types namely Type:EVERYTHING_TE occurred in the majority, whereas repeats such as DNA/TcMar-Fot1, LTR/Gypsy, LINE/Tad1, and Type:LINE is also more in copy number (Table 2). Further, SSR analysis showed that about 18,830 were present in RMg_Dl genome. Furthermore, in the case of di-nucleotides, (TA)n was the most frequent, followed by (AG)n and (AT)n. Similarly, among tri-nucleotide repeats, the (CAG)n repeats were most frequent, followed by (GCT)n repeats. In the case of frequency for tetra-nucleotide repeats, (TACC)n was most frequent, followed by (TAGG)n (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2.

The detected transposable elements in M. oryzae RMg_Dl genome.

| Family | M. oryzae RMg_Dl |

|---|---|

| DNA | 41 |

| DNA/TcMar-Fot1 | 829 |

| Type:DNA | 870 |

| LINE/Tad1 | 257 |

| Type: LINE | 257 |

| LTR/Copia | 344 |

| LTR/Gypsy | 1072 |

| Type:LTR | 1416 |

| Type:EVERYTHING_TE | 2543 |

| Type:Simple_repeat | 34 |

| Type:Unknown | 2587 |

| Total | 10,250 |

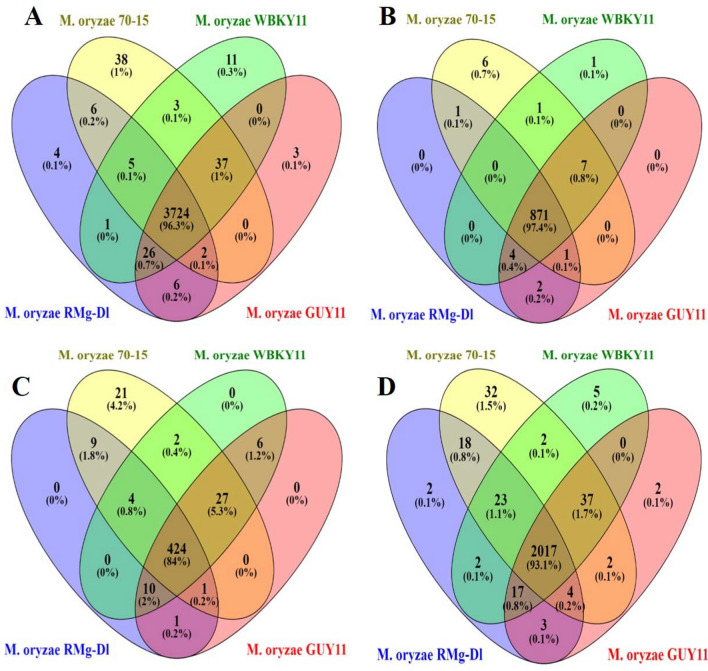

Analysis of protein family and conserved domain in sequenced genomes

The InterProScan analysis was performed for identifying protein family (PFAM) and superfamily, which showed the total occurrence of 3774 protein families, 879 superfamilies in the RMg_Dl genome. The comparison among RMg_Dl with genomes for shared and unique PFAM, protein information resource superfamily (PIRSF), superfamily, and conserved domains in sequenced genome showed that 3724 (96.3%) PFAMs, 871 (97.4%) superfamily, 424 (84%) PIRSF and 2017 (93.1%) CDD were shared in studied genomes (Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables S3, S4 and S5). The PFAM detailed exploration showed that family/domain such as WD domain, major facilitator superfamily, cytochrome P450, fungal specific transcription factor domain, protein kinase domain, and ABC transporter was highly prevalent (Supplementary Table S3). Similarly, superfamily identification showed that P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase, NAD(P)-binding domain, MFS transporter, Alpha/Beta hydrolase fold, FAD/NAD(P)-binding domain, and glycoside hydrolase superfamily were prevalent in the genome (Supplementary Table S4). Further, proteins were subjected for the transmembrane, signal peptide and cytoplasmic orientation classification using Phobius tool showed that transmembrane, non-cytoplasmic domain, and cytoplasmic domain associated proteins were highly present in the genome (Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 3.

The predicted proteins InterProScan analysis of M. oryzae RMg_Dl, M. oryzae 70-15, M. oryzae WBKY11 and M. oryzae GUY11 genomes. The figure A, B, C and D shows the analyses against PFAM, superfamily, PIRSF and CDD databases, respectively.

Assembled genome functional annotation using gene ontology

The functional annotations of genes predicted were performed based on gene ontology using InterProScan and Blast2GO mapping and annotation. It provides functional signature vocabulary and hierarchical network relationships for the gene products in three classes: biological process, molecular function, and cellular component. Gene ontology (GO) mapping and annotation of sequences resulted in enrichment at level 2 category of the biological process revealed that mapped sequences ranged between 2746 and 7, molecular function ranged from 2787 to 7. The sequences assigned for cellular components ranged from 1696 to 528 (Fig. 4). Among the biological process, the majority of genes were linked with metabolic processes, cellular processes, localization, biological regulation, signaling, negative and positive regulation of biological processes (Fig. 4A). The molecular function associated GO terms were highly prevalent for catalytic function, binding, transporter activity, molecular function regulator, and structural molecule activity (Fig. 4B). Similarly, a cellular component associated terms were cellular anatomical activity, intracellular and protein-containing complex were prevalent (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Functional annotation of predicted genes/proteins of M. oryzae RMg_Dl in GO term: biological process (A) and GO term: Molecular Function (B), and cellular component (C).

Orthologous genes analysis

The orthologous features analysis for predicted proteins showed that 9216 orthologous genes were shared among RMg_Dl with 70-15, WBKY11 and GUY11 genomes, whereas 21 genes were found uniquely in RMg_Dl genome (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Identification of pathogenicity genes, virulence factors (VFs) and effectors

Further, the predicted proteins were analyzed against the pathogen-host interaction (PHI) database that revealed a total of 833 PHI genes were found in the RMg_Dl genome. Among that, the majority of PHI genes were associated with reduced virulence and pathogenicity loss (Fig. 5). Also, there were a total of 51 different VFs identified, and its annotation showed that four copies of these VFs identified as gypsy retrotransposon, and function like pathogenicity, toxin activity, etc. (Supplementary Table S7). Further, these VFs consist of protein families namely Sel1 repeat, Heat-labile enterotoxin alpha chain, and WD domain, G-beta repeat, and superfamily namely ADP-ribosylation, S-adenosylmethionine synthetase, etc. (Supplementary Table S8).

Figure 5.

The assigned protein sequences to different PHI categories.

The effectors were predicted through phobius mapping which showed 1986 signal peptide sequences, and then EffectorP3.0 was utilized for possible potential effector determination. This showed that a total of 603 effector genes, in which 330 were cytoplasmic and 273 were apoplastic effectors (Supplementary Table S9). Thus, on an average, 5.72% of the total proteome content involved in effectors related functions. Upon the comparative study of these effectors with other genomes using orthologous approach, the total of 443 common effectors protein were documented, whereas 15 effectors were only shared among RMg_Dl and 70-15 genomes (Supplementary Fig. S2). Further, 10 effectors genes were identified as AVR proteins, which classified to AVR-Pii in majority (4 copy), followed by Avr-Pik (2 copy) and Avr-Pita, AVR-Pita2, Avr-Pi54, AVR-Pita1 with single copy. These effectors CAZymes annotation showed that a total of 31 families were found with its total 64 copies in this genome. Among that family, AA9 was found with high occurrence, followed by CE5, CE1, AA16, and GH11 etc., in identified effectors (Supplementary Table S10). Additionally, PFAM annotation showed that a total of 142 different PFAMs were identified, which accounted for 237 copies. Among that glycosyl hydrolase family-61 was the most abundant followed by fungal cellulose binding domain, and chitin recognition protein etc. (Supplementary Table S11).

Identification of CAZymes

The CAZymes identification showed the presence of different 542 CAZyme families. These CAZymes extended analyses showed that the most abundant family was glycoside hydrolase (GH) (257 GH family). Next to GH, the auxiliary activities (AA) was the second-highest family (118 AA). The third highest abundant family was glycosyltransferase (GT) (94 GTs). Interestingly, the pectin lyase (PL) family showed the least abundance in the CAZyme family composition (Table 3). Further, the downstream analysis revealed that the AA7 and AA9 family was the most abundant, followed by GH3 and CE5 (Supplementary Table S12). Additionally, the other highly abundant families such as CE4, GH47, GH2, AA11, CE3, GH131, GH31 were found to be equally present in studied genomes. Overall, a comparison of all CAZymes studied in genomes revealed that 167 (95.4%) families were shared between RMg_Dl, 70-15, WBKY11 and GUY11 genomes. Although, none of the CAZymes were found to be uniquely present in RMg_Dl whereas AA1, GH109, GT61, and PL42 families were uniquely detected in the 70-15 genome (Fig. 6).

Table 3.

The comparative CAZymes family profile in M. oryzae RMg_Dl, P. oryzae 70-15, M. oryzae WBKY11, and M. oryzae GUY11 genomes.

| Family | M. oryzae RMg_Dl | P. oryzae 70-15 | M. oryzae WBKY11 | M. oryzae GUY11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 118 | 130 | 121 | 115 |

| CBM | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| CE | 53 | 53 | 54 | 53 |

| GH | 257 | 256 | 263 | 260 |

| GT | 94 | 100 | 98 | 94 |

| PL | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 542 | 560 | 557 | 543 |

Figure 6.

Identification and comparison of unique and shared CAZymes in M. oryzae RMg_Dl, M. oryzae 70-15, M. oryzae WBKY11 and M. oryzae GUY11 genomes.

Identification of metabolic pathways

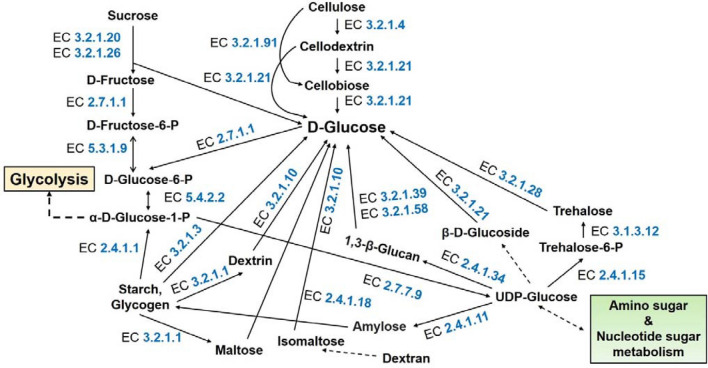

The KEGG metabolic pathway analysis of the sequenced genome showed that the majority of genes were linked with metabolism and cellular process biochemical metabolic pathway categories. The detected pathways namely metabolism (KO:09100), in particular, carbohydrate metabolism (KO:09101) associated genes were 282 in the genome, and these genes were found to be distributed in fifteen different biochemical pathways (Table 4). Additionally, various genes are linked with pathways such as glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, starch, and sucrose metabolism, butanoate metabolism, propanoate metabolism, and inositol phosphate metabolism, fructose, and mannose and metabolism, pentose phosphate pathway were detected in the genome (Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. S2). Among them, plant polysaccharide namely cellulose degradation key pathway, starch, and sucrose metabolism route-main enzyme endoglucanase (EC 3.2.1.4), cellulose 1,4-beta-cellobiosidase (EC 3.2.1.91), and beta-glucosidase (EC 3.2.2.21) were found in the genome. Similarly, pentose and glucuronate interconversions pathways involve the pectin degradation enzyme endo-polygalacturonase (EC 3.2.1.15) and pectinesterase (EC 3.1.1.11) and pectate lyases (polygalacturonate lyase) (EC 4.2.2.2) were also found in this genome (Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. S3). Analysis of the biochemical pathways associated with energy metabolism (KO:09102) resulted in distinguishing total of 134 genes distributed in six (6) different pathways. Among the pathways, the majority of the genes were associated with oxidative phosphorylation followed by sulfur and nitrogen metabolism (Supplementary Table S13).

Table 4.

Carbohydrate metabolism KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway for M. oryzae RMg_Dl.

| Carbohydrate metabolism pathways | M. oryzae RMg_Dl (Gene count) |

|---|---|

| KO:00010 Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis | 26 |

| KO:00020 Citrate cycle | 21 |

| KO:00030 Pentose phosphate pathway | 17 |

| KO:00040 Pentose and glucuronate inter conversions | 19 |

| KO:00051 Fructose and mannose metabolism | 20 |

| KO:00052 Galactose metabolism | 15 |

| KO:00053 Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | 5 |

| KO:00500 Starch and sucrose metabolism | 26 |

| KO:00520 Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 27 |

| KO:00620 Pyruvate metabolism | 29 |

| KO:00630 Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 23 |

| KO:00650 Butanoate metabolism | 12 |

| KO:00640 Propanoate metabolism | 18 |

| KO:00660 C5-Branched dibasic acid metabolism | 3 |

| KO:00562 Inositol phosphate metabolism | 21 |

| Total | 282 |

Figure 7.

Starch and sucrose metabolism pathways depicting various enzymes involved including plant cell wall degrading enzymes. In here, the Sysname of enzymes related to the biosynthetic machinery are depicted in blue-colored EC numbers: The key to all of the EC numbers are as follows: EC 3.2.1.4, 4-β-D-glucan 4-glucanohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.21, β-D-glucoside glucohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.91, 4-β-D-glucan cellobiohydrolase (non-reducing end); EC 3.2.1.20, α-D-glucoside glucohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.26, β-D-fructofuranoside fructohydrolase; EC 2.7.1.1, ATP:D-hexose 6-phosphotransferase; EC 5.3.1.9, D-glucose-6-phosphate aldose-ketose-isomerase; EC 2.4.1.15, UDP-α-D-glucose:D-glucose-6-phosphate 1-α-D-glucosyltransferase; EC 3.1.3.12, α, α-trehalose-6-phosphate phosphohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.28, α, α-trehalose glucohydrolase; EC 2.4.1.11, UDP-α-D-glucose: glycogen 4-α-D-glucosyltransferase; EC 2.4.1.18, (1->4)-α-D-glucan:(1->4)-α-D-glucan 6-α-D-[(1->4)-α-D-glucano]-transferase; EC 2.4.1.1, (1->4)-α-D-glucan:phosphate α-D-glucosyltransferase; EC 3.2.1.1, 4-α-D-glucan glucanohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.3, 4-α-D-glucan glucohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.10, Oligosaccharide 6-α-glucohydrolase; EC 5.4.2.2, α-D-glucose 1,6-phosphomutase; EC 2.4.1.34, UDP-glucose:(1->3)-β-D-glucan 3-β-D-glucosyltransferase; EC 3.2.1.39, 3-β-D-glucan glucanohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.58, 3-β-D-glucan glucohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.21, β-D-glucoside glucohydrolase and EC 2.7.7.9, UTP: α-D-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase.

Figure 8.

Pentose and glucuronate interconversion depicts the route enzymes of plant cell wall degrading enzymes.

The identification of environmental information processing (KO:09130) pathways revealed that 404 genes were in-particularly associated with signal transduction (KO:09132) pathways. The identified genes were involved in a total of thirty-two biological (biochemical) pathways (Table 5). These signaling pathways extended exploration showed that MAPK signaling pathway (Supplementary Fig. S4) associated genes were highest, followed by mTOR signaling pathway (KO:04150), PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (KO:04151), and AMPK signaling pathway (KO:04152). The other detected pathways were the two-component system, RAS signaling pathway, and calcium (Ca2+) signaling pathway, etc.

Table 5.

Signal transduction KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway for M. oryzae RMg_Dl.

| Signal transduction pathways | M. oryzae RMg_Dl (gene count) |

|---|---|

| KO:02020 Two-component system | 19 |

| KO:04014 Ras signaling pathway | 15 |

| KO:04015 Rap1 signaling pathway | 6 |

| KO:04010 MAPK signaling pathway | 15 |

| KO:04013 MAPK signaling pathway-fly | 13 |

| KO:04016 MAPK signaling pathway-plant | 3 |

| KO:04011 MAPK signaling pathway-yeast | 56 |

| KO:04012 ErbB signaling pathway | 5 |

| KO:04310 Wnt signaling pathway | 13 |

| KO:04330 Notch signaling pathway | 4 |

| KO:04340 Hedgehog signaling pathway | 5 |

| KO:04341 Hedgehog signaling pathway-fly | 7 |

| KO:04350 TGF-beta signaling pathway | 6 |

| KO:04390 Hippo signaling pathway | 9 |

| KO:04391 Hippo signaling pathway-fly | 7 |

| KO:04392 Hippo signaling pathway-multiple species | 6 |

| KO:04370 VEGF signaling pathway | 7 |

| KO:04371 Apelin signaling pathway | 12 |

| KO:04630 Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 4 |

| KO:04064 NF-kappa B signaling pathway | 4 |

| KO:04668 TNF signaling pathway | 2 |

| KO:04066 HIF-1 signaling pathway | 15 |

| KO:04068 FoxO signaling pathway | 13 |

| KO:04020 Calcium signaling pathway | 9 |

| KO:04070 Phosphatidylinositol signaling system | 17 |

| KO:04072 Phospholipase D signaling pathway | 12 |

| KO:04071 Sphingolipid signaling pathway | 19 |

| KO:04024 cAMP signaling pathway | 9 |

| KO:04022 cGMP-PKG signaling pathway | 8 |

| KO:04151 PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 24 |

| KO:04152 AMPK signaling pathway | 23 |

| KO:04150 mTOR signaling pathway | 37 |

| Total | 404 |

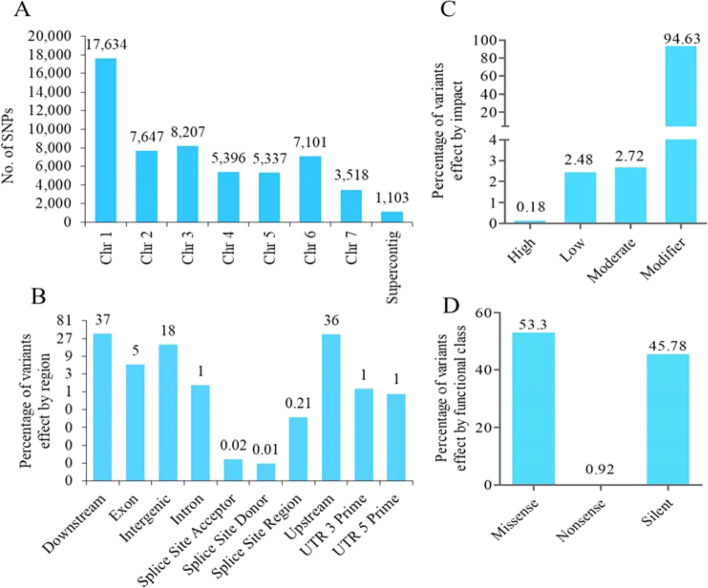

Identification of variants

The SNPs and InDels calling showed that a total of 55,943 variants with their distribution as 49,065 SNPs, 3267 insertions and 3611 deletions in this genome. The SNPs chromosome wise classification showed that the highest SNPs were found on chromosome 1 and followed to chromosome 3 (Fig. 9A). The genome wide distribution of SNP density determination showed the occurrence of ~14 SNPs per 10 Kb in M. oryzae RMg_Dl genome. The identified SNPs transition and transversions were 39,326 and 9738, with their transition–transversion (Ts/TV) ratio was 4.04. The annotation of variants classified effects to region-wise, impact and functional class (Fig. 9). The majority of identified variants effect by region-wise were downstream (37%), followed to upstream (36%) and intergenic (18%) (Fig. 9B). The effect by impact showed that majority of variants depicted modifier (94.63%) followed to moderate (2.72%) and least for high (0.18%) impact (Fig. 9C). Moreover, effect by functional class, the missense type variants were 53.3% and silent were 45.78% (Fig. 9D). The conservative in-frame insertions and deletion were 0.05% and 0.04%, respectively. Similarly disruptive in-frame insertion and deletion were 0.03% and 0.03% respectively (Supplementary Table S14). Since the M. oryzae is a kind of rice blast disease causing pathogenic fungi, therefore we extensively performed the occurrence of variants in virulence factors and predicted potential effectors. Among the detected VFs, the total of 1340 variants were identified, in which 115 SNPs were identified as missense type in 7 different VFs. Also, majority of identified missense SNPs of VFs were found on chromosome 1, followed by chromosome 6, and VF namely MGG_09263 was found with highest SNPs (82) (Supplementary Table S15). Similarly, for effectors, the total of 6743 variants were identified, among that 5768 were SNPs and 975 were indels. Effectors missense type SNPs determination showed that a total of 71 missense type SNPs, with highest occurrence on chromosome 1 followed by chromosome 4 and 2. The effector MGG_17020 identified with highest missense SNPs, which was located on chromosome 4 (Supplementary Table S16). The occurrence of variants in AVR effectors were 75 in which 63 were SNPs and 12 were InDels. Among this, most of the variants were located in upstream region. The single missense SNP was was found in Avr-Pii, and located on Chromosome2: 842166G > A (c.188C > T, p. Ala63Val). The effectors conservative and disruptive inframe InDels annotation showed that total of 29 InDels, in which conservative inframe deletion and insertions were 10 and 6, whereas disruptive inframe deletion and insertion were 6, and 7 respectively (Supplementary Table S17).

Figure 9.

Identified variants and effect annotation of M. oryzae RMg_Dl genome. A = variants distribution by chromosome, B = effect by different region, C = effect by impact and D = effect by functional class.

Discussion

The advent of high throughput sequencing technologies with short and long-read sequencing chemistry coupled with hybrid assembly have extensively facilitated in depth understanding of biochemical pathways, virulence factors, and conserved domains in the fungal genomes. In this study, we performed the WGS of rice blast disease-causing fungal species namely Magnaporthe oryzae RMg_Dl. The blast fungus is one of the wide spread pathogen reported to cause epidemics in different geographical locations and all major rice varieties6,41,42. Therefore, the comparative whole genome alignment based phylogenetic tree was generated to decipher the evolutionary relationship of RMg_Dl with other 13 Magnaporthe genomes publically released from India, Japan, China, Thailand (Asia), USA and Guyana (Fig. S6). This analysis depicted the close relationship of Indian genomes with each other (Cluster 1), whereas moderately related to isolates representing Japan, Thailand, and shared distant relationship with Guyana (GUY11), USA (70-15) and China (HN19311, 98-06) genomes (Cluster 3). This indicated the M. oryzae pathotypes representing same or proximal geographic locations (Asian continent) showed high genetic similarity (India, China, Thailand and Japan), except WBKY11 (USA) genome. In our previous study, we reported that diverse pathotypes of Magnaporthe were genetically homogenous indicating the trans-boundary movement across the continents43. Such a pathogenic variation could be possibly associated with dynamic mechanism such as genetic mutations, recombination, geographical location and host resistance.

In the sequenced genome, we identified various genes involved in host–pathogen interaction such as virulence and pathogenicity mediators. Such occurrence of pathogenicity-related genes plays an essential role in initiating infection in the host42–44. These genes mutation is believed to confer resistance against fungicides45. Additionally, these genes have been documented for conferring fungicides resistance at the field level46. In this study, we identified 51 different VFs containing 59 PFAM and 35 superfamilies, with four VFs identified as gypsy retrotransposon. The VFs were reported for functions like pathogenicity, toxin activity, etc. The NR database blast classified VFs namely natural trehalases acts as trehalose breakdown (component of plant cell wall) and regulated by signaling pathway and activation by phosphorylation and stimulated by Ca2+ and Mn2+47. Similarly another VFs encode ‘ras-like protein ced-10’ involved in nutrient availability sensing and linked with cell growth and morphogenesis48. The gypsy retrotransposon reported for DNA segment transposition, re-arrangement, genome evolution and widely distributed in ascomycota fungi and more details described here49.

Among the total effectors, majority of effectors were cytoplasmic which acts initially upon infection enriches in biotrophic interfacial complex (BIC) prior getting transfered into plant cells, and continues its secretion after invasive hyphae development and invade adjacent plant cells50. Whereas, apoplastic effectors upon secretion, disseminated in the extracellular space of the fungal cell wall and extra-invasive-hyphal membrane (EIHM). These secreted effector are a small secreted proteins that alter host cell organization and function like manipulate plant immunity and physiology to promote infection through suppressing or activating effector-triggered immunity (ETI)51. The AVR-Pii and AVR-Pik were reported for genomic instability52. AVR-Pii, Avr-Pita effector reported for damaging the host innate immunity53. Functional annotation of effectors using PFAM revealed that total of 237 families, but there are decreased annotation compared to total effectors, because possibly most of the effectors were classified as putative uncharacterized/hypothetical proteins. Therefore, utilizing the resources such as protein domains, families and superfamily driven classification could provide more insights of possible functional features of proteins and thus predicted effectors also26. Using this approach, the documented effectors classification showed that higher occurrence of glycosyl hydrolase family 61, fungal cellulose binding domain and cutinase were observed. In particular, cutinase family associated with diverse functions such as cell surface recognition, germinal differentiation, appressorial growth, host infiltration and then virulence maturation. Moreover, role of this protein documented for cyclic AMP/protein kinase A and diacylglycerol protein kinase C signalling upon activation which eventually triggers appressorium development and infection progress by this fungus54.

Moreover, we identified a total of 49,065 SNPs, 3267 insertions and 3611 deletions in this genome with ~14 SNPs per 10 Kb. The majority of variants were found on chromosome 1 and similar result was reported for other M. oryzae strains55. Further, virulence associated SNPs were located on chromosome 1, 2, 3, 4 and 756. In this study, we found various SNPs on these chromosomes. The variants annotation effects classified into region wise effect showed that majority of variants were located in the gene regulatory elements namely downstream and upstream regions. The occurrence of variants in these regions potentially invovlve in gene expression regulation resulted in upregulation or downregulation. Interestinglly, we observed various missense SNPs which causes the amino acid change in protein structure resulting to altered protein property and functionality. This could be also associated with prompting infection, severity and susceptibility with increased incidence of fungal disease57. We documented various SNPs among genomic regions of upstream, downstream, and untranslated region (UTR) region, which influence the gene expression and regulation at the post-transcriptional level and protein synthesis58. The 5′UTR mutation influence the binding of proteins and results to stimulation or suppression of translational regulation. Meanwhile 3′UTR mutation reported to influence the binding sites of miRNA and polyA which affect the translational deregulation59. In this study, 54 effectors genes were documented with missense and InDels genetic variations, which accounted nearly 0.09% (54/603) of total effectors genes. Though, there were a single missense SNPs was found on Avr-Pii effector. Also we found various SNPs in AVR-Pita1 and AVR-Pita2, and previously reported for high variability and its diversification60.

The study of genomes for families, conserved domains through InterProScan resulted in the identification of nearly 96% PFAM, 84% PIRSF, and 93% CDD were shared in the studied genomes. Further, in the present study, the majority of PFAMs namely WD domain, G-beta repeat, major facilitator superfamily, and cytochrome P450 family, P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase, NAD(P)-binding domain, and alpha/beta hydrolase fold superfamily were expanded the genome. These detected families and conserved domains were documented for various mechanisms viz. MAPK for growth61, virulence, and pathogenicity62, ABC transporter for virulence63 that overall mediate multiple significant roles in pathogen-host interaction64.

Repeats are also unique features of fungal genomes, and these identified SSRs could be utilized for fungal diversity study and disease management, species/strain differentiation, and detection65. The rich genomic bases of GC and AT are applied for the assessment of fungal defense against transposon expansion which works through repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) and genome evolution. Such processes play a differentiating choice and facilitation of host-microbe interaction66. In this study, we documented more than 18,000 SSRs which can be applied for the study of fungal population diversity and potential application towards making an efficient management strategy for disease prevention. Such methods are efficiently applied for controlling the citrus leaf and fruit disease caused by fungi67.

The study on fungal genomes about the content of CAZymes showed that this organism contains distinct types of CAZyme families, which facilitates fungus to efficiently degrades host complex polysaccharides. The CAZymes also play an essential role in pathogen-host interactions (PHI) as pathogenic fungus invades host on plant cell wall via the action of cell wall degrading enzymes12. We detected the high occurrence of GH families, and studies reported that the GH family plays a potential role in the breakdown of complex polysaccharides coupled with additional CAZymes like CBM and PL, which increase the breakdown efficacy and pave the path for other breakdown processes in the environment69. Moreover, the genomic study of various pathogenic fungal species showed vast heterogeneity in CAZymes content because of their host specificity and nutritional requirement, which also facilitated the digestion of complex plant polysaccharides for nutritive addition and later simplify the infection process12,70. The pathogenic fungus is reported to contain a distinct number of CAZymes, whereas less than saprophytic and necrophytic fungi12. The high content of various GH family also reported in fungus invading the monocot than dicot plant because monocot enriched with polysaccharides12,70.

The biochemical pathway determination detected the presence of various metabolic pathways associated with variable enzymes in the genome. Among that plant polysaccharide namely cellulose degradation key pathway, starch and sucrose metabolism route-main enzyme endoglucanase (EC 3.2.1.4), cellulose 1,4-beta-cellobiosidase (EC 3.2.1.91), and beta-glucosidase (EC 3.2.2.21) were found in the genome. The endoglucanase (EC 3.2.1.4) initially degrades cellulose to cellodextrin and then to cellobiose. Cellulose 1,4-beta-cellobiosidase (EC 3.2.1.91) degrades i) cellulose to cellobiose, ii) cellodextrin to cellobiose. Then, beta-glucosidase (EC 3.2.2.21) generates glucose via two ways- i) cellobiose to glucose, and ii) cellodextrin to glucose (Fig. 7). Further cell wall degrading enzyme endo-polygalacturonase (EC 3.2.1.15) of PL29 CAZymes, and pectate lyases (EC 4.2.2.2) of PL1 CAZymes and endo-1,4-beta-xylanase (EC:3.2.1.8) were detected which further mediate a typical role in infection and utilizes it for own growth and reproduction71,72. These enzymes are recognized for cell wall degradation enzyme (CWDE) which facilitates the infection and plant cell damage70,71. The enzymatically released glucose and other compounds were utilized by fungi for their growth, reproduction, and proliferation in the host71.

Functional pathway two-component system also plays an essential role in rice blast disease incidence along with the combined mechanism of MAP kinase and cAMP signaling mediated formation of infection component on rice host62,73. Reports also demonstrated that cAMP signaling was associated with fungal growth and infection development73–75. Such kinase signaling mechanisms include the phosphorylation mediated signaling process, chemotaxis, virulence process, and secondary metabolite production in fungi76. Additionally, the mechanism of histidine kinase-mediated environmental responses, pathogenicity, hyphal development, and then sporulation have also been documented8,77,78. The MAPK pathway descriptive study revealed that various enzymes of M. oryzae RMg_D1 were mapped to signaling mechanisms such MAPKKK, MAPKK, and MAPK (Supplementary Fig. S4). Additionally, the protein domains are linked to each other for creating multi-domain protein structures to gain a wide range of functional property79,80. This can be exemplified through flexible architectures of signaling pathways like mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades81,82. This pathway is associated with controlling for various biological processes such as metabolism, cellular morphology, cell cycle progress, and gene expression in the influence of any extracellular signals or stimuli83 and cellular signaling and pathogenesis-related structure development64,84. In particular, among pathogenic fungi, metabolic pathways, ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are primarily involved in defense activity against secondary metabolites or toxins secreted by the host85.

In this sequenced genome, we observed various transport families such as the ABC transporter, phosphate transporter family, major facilitator superfamily (MFS) involved in the transport of a broad range of minerals and nutrients. The role of ABC and MFS transporters documented for the protection against natural toxic substance exists in the atmosphere or synthetic toxic compounds such as fungicides and antimycotic agents41,86. Pitkin, et al.87 reported that ABC transporters also offer defense against antimicrobial agents. Additionally, crucial role in host pathogenicity while providing protection against host defense mechanisms or releasing host-specific toxins. These transporters play as a resistance barrier against various fungicides, though prolonged uses of fungicidal agents resulted in the occurrence of resistance in ABC and MFS transporter including chemically unrelated agents and causes the decreased accumulation of these agents41,86. We also detected superfamily namely cytochrome P450 (CYP) monooxygenase superfamily which is reported to be involved in a wide range of functions such as multidimensional metabolic activity and support to survival in a distinct ecological environment88 with a contribution in infection occurrence. The fungal CYP associated with distinct kind of secondary metabolites production for its own protection and compete against attacking organism such as bacteria, plants, animals and also against other fungi89,90. These compounds act as wide range of beneficial role like antibiotic, immune suppressor and mycotoxic actions91,92.

Conclusion

In the present study, the whole genome sequencing of filamentous rice blast disease-causing fungus M. oryzae RMg_Dl was performed. The functional annotation revealed the presence of distinct enzymes linked with various metabolic pathways. The study also documented various carbohydrate metabolism-associated pathways that included starch and sucrose metabolism, pentose and glucuronate interconversion, and signaling associated namely MAPK, cAMP pathways. We also observed various CAZymes with high content of the GH family, pathogen-host interaction-related genes, effectors and virulence factors. This information serves as a genomic architecture for the optimization of genus Magnaporthe mediated blast disease management and assessment of population diversity. Moreover, detected genes or proteins can be utilized as potential targets for marker development to screen the blast pathogenic organisms.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

All authors are thankful to the Indian Council of Agricultural Research-Consortium Research Project On Genomics [CRP (Genomic)/VIII/2021-22/II] for funding the WGS of Magnaporthe and National Agricultural Higher Education Project (NAHEP)-CAAST on ‘Genomics-Assisted Crop Improvement and Management’ (NAHEP/CAAST/2018-19/07) for assisting the bioinformatic analysis. We are thankful to the Director, ICAR-IARI, New Delhi for providing all infrastructure facilities. Furthermore, the authors would also like to acknowledge the anonymous peer reviewers who gave constructive comments throughout the entire review process.

Author contributions

A.K. and V.C. conceived the grant. A.K. and B.R. designed the study. BR performed bioinformatic analysis and drafted manuscript, and N.S. isolated fungus and other wet-lab experiment. A.K., S.M., N.S., V.C. and P.G. edited the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-01980-2.

References

- 1.Ronald P. Plant genetics, sustainable agriculture and global food security. Genetics. 2011;188:11–20. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.128553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma TR, et al. Rice blast management through host-plant resistance: retrospect and prospects. Agric. Res. 2012;1:37–52. doi: 10.1007/s40003-011-0003-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta S, Singh B, Dhakate P, Rahman M, Islam MA. Rice, marker-assisted breeding, and disease resistance. In: Wani SH, editor. Disease Resistance in Crop Plants: Molecular, Genetic and Genomic Perspectives. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. pp. 83–111. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean R, et al. The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012;13:414–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miah G, et al. Blast resistance in rice: a review of conventional breeding to molecular approaches. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013;40:2369–2388. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard RJ, Valent B. Breaking and entering: host penetration by the fungal rice blast pathogen Magnaporthe grisea. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1996;50:491–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talbot NJ. On the trail of a cereal killer: exploring the biology of Magnaporthe grisea. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;57:177–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemecek JC, Wuthrich M, Klein BS. Global control of dimorphism and virulence in fungi. Science. 2006;312:583–588. doi: 10.1126/science.1124105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.TeBeest, D., Guerber, C. & Ditmore, M. Rice blast. In: The Plant Health Instructor. 10.1094/PHI-I-2007-0313-07 (2007).

- 10.Valent B. Rice blast as a model system for plant pathology. Phytopathology. 1990;80:33–36. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-80-33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acero FJ, et al. Development of proteomics-based fungicides: new strategies for environmentally friendly control of fungal plant diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011;12:795–816. doi: 10.3390/ijms12010795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iquebal MA, et al. Draft whole genome sequence of groundnut stem rot fungus Athelia rolfsii revealing genetic architect of its pathogenicity and virulence. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5299. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05478-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar, A. et al. Genome sequence of a unique Magnaporthe oryzae RMg_Dl isolate from India that causes blast disease in diverse cereal crops, obtained using Pacbio Single-Molecule and Illumina Hiseq2500 sequencing. Genome Announc.10.1128/genomeA.01570-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Prakash, G. et al. First draft genome sequence of a Pearl Millet blast pathogen, Magnaporthe grisea strain PMg_Dl, obtained using PacBio Single-Molecule Real-Time and Illumina NextSeq 500 Sequencing. Microbiol. Resour. Announc.10.1128/MRA.01499-18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salmela L, Rivals E. LoRDEC: accurate and efficient long read error correction. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3506–3514. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruan J, Li H. Fast and accurate long-read assembly with wtdbg2. Nat. Methods. 2020;17:155–158. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0669-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu, G. C. et al. LR_Gapcloser: a tiling path-based gap closer that uses long reads to complete genome assembly. Gigascience10.1093/gigascience/giy157 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Simao FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee I, Ouk Kim Y, Park SC, Chun J. OrthoANI: An improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016;66:1100–1103. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humann JL, Lee T, Ficklin S, Main D. Structural and functional annotation of eukaryotic genomes with GenSAS. Methods Mol. Biol. 1962;29–51:2019. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform.Chapter 4, Unit 4 10, 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Stanke M, Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W465–467. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lagesen K, et al. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan PP, Lowe TM. tRNAscan-SE: searching for tRNA genes in genomic sequences. Methods Mol. Biol. 1962;1–14:2019. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones P, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conesa A, Gotz S. Blast2GO: a comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int. J. Plant Genomics. 2008;2008:619832. doi: 10.1155/2008/619832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cantarel BL, et al. The carbohydrate-active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D233–238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang L, et al. dbCAN-seq: a database of carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZyme) sequence and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D516–D521. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu T, Yao B, Zhang C. DFVF: database of fungal virulence factors. Database (Oxford) 2012;2012:bas32. doi: 10.1093/database/bas032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sperschneider, J. & Dodds, P. N. EffectorP 3.0: prediction of apoplastic and cytoplasmic effectors in fungi and oomycetes. bioRxiv.10.1101/2021.07.28.454080 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Xu L, et al. OrthoVenn2: a web server for whole-genome comparison and annotation of orthologous clusters across multiple species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W52–W58. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W182–185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knudsen S. Promoter2.0: for the recognition of PolII promoter sequences. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:356–361. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.5.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cingolani P, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly. 2012;6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. ProgressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLOS ONE. 2010;5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stergiopoulos I, Zwiers L-H, De Waard MA. Secretion of natural and synthetic toxic compounds from filamentous fungi by membrane transporters of the atp-binding cassette and major facilitator superfamily. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2002;108:719–734. doi: 10.1023/A:1020604716500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H, Zheng X, Zhang Z. The Magnaporthe grisea species complex and plant pathogenesis. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016;17:796–804. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheoran N, Ganesan P, Mughal NM, Yadav IS, Kumar A. Genome assisted molecular typing and pathotyping of rice blast pathogen, Magnaporthe oryzae, reveals a genetically homogenous population with high virulence diversity. Fungal Biol. 2021;125:733–747. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta L, Vermani M, Kaur Ahluwalia S, Vijayaraghavan P. Molecular virulence determinants of Magnaporthe oryzae: disease pathogenesis and recent interventions for disease management in rice plant. Mycology. 2021;12:174–187. doi: 10.1080/21501203.2020.1868594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cools HJ, Hammond-Kosack KE. Exploitation of genomics in fungicide research: current status and future perspectives. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013;14:197–210. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brent, K. J. & Hollomon, D. W. Fungicide resistance: the assessment of risk. Fungicide Resistance Action Committee 2007, FRAC Monograph No.2 second, (revised) edition (2007).

- 47.Jorge JA, Polizeli MDLTM, Thevelein JM, Terenzi HF. Trehalases and trehalose hydrolysis in fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1997;154:165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harispe L, Portela C, Scazzocchio C, Peñalva MA, Gorfinkiel L. Ras GTPase-activating protein regulation of actin cytoskeleton and hyphal polarity in Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:141–153. doi: 10.1128/EC.00346-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muszewska A, Hoffman-Sommer M, Grynberg M. LTR retrotransposons in fungi. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e29425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang S, Xu JR. Effectors and effector delivery in Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003826. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hogenhout SA, Van der Hoorn RA, Terauchi R, Kamoun S. Emerging concepts in effector biology of plant-associated organisms. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22:115–122. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-22-2-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Białas A, et al. Lessons in effector and nlr biology of plant-microbe systems. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2018;31:34–45. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-08-17-0196-fi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Han J, et al. The fungal effector Avr-pita suppresses innate immunity by increasing COX activity in rice mitochondria. Rice (N Y) 2021;14:12. doi: 10.1186/s12284-021-00453-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skamnioti P, Gurr SJ. Magnaporthe grisea cutinase2 mediates appressorium differentiation and host penetration and is required for full virulence. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2674–2689. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.051219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cao J, et al. Genome re-sequencing analysis uncovers pathogenecity-related genes undergoing positive selection in Magnaporthe oryzae. Sci. China Life Sci. 2017;60:880–890. doi: 10.1007/s11427-017-9076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Korinsak S, et al. Genome-wide association mapping of virulence gene in rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae using a genotyping by sequencing approach. Genomics. 2019;111:661–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naik, B., Ahmed, S. M. Q., Laha, S. & Das, S. P. Genetic susceptibility to fungal infections and links to human ancestry. Front. Genet.10.3389/fgene.2021.709315 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Blake WJ, et al. Phenotypic consequences of promoter-mediated transcriptional noise. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:853–865. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chatterjee S, Pal JK. Role of 5'- and 3'-untranslated regions of mRNAs in human diseases. Biol. Cell. 2009;101:251–262. doi: 10.1042/bc20080104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chuma I, et al. Multiple translocation of the AVR-Pita effector gene among chromosomes of the rice blast Fungus Magnaporthe oryzae and related species. PLOS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002147. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao X, Mehrabi R, Xu JR. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways and fungal pathogenesis. Eukaryot. Cell. 2007;6:1701–1714. doi: 10.1128/EC.00216-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leng Y, Zhong S. The role of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling components in the fungal development, stress response and virulence of the fungal cereal pathogen Bipolaris sorokiniana. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0128291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roohparvar R, Huser A, Zwiers LH, De Waard MA. Control of Mycosphaerella graminicola on wheat seedlings by medical drugs known to modulate the activity of ATP-binding cassette transporters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:5011–5019. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00285-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hamel LP, Nicole MC, Duplessis S, Ellis BE. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plant-interacting fungi: distinct messages from conserved messengers. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1327–1351. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Canfora L, et al. Development of a method for detection and quantification of B. brongniartii and B. bassiana in soil. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22933. doi: 10.1038/srep22933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Testa AC, Oliver RP, Hane JK. OcculterCut: a comprehensive survey of AT-rich regions in fungal genomes. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016;8:2044–2064. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moges AD, et al. Development of microsatellite markers and analysis of genetic diversity and population structure of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides from Ethiopia. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0151257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hervé C, et al. Carbohydrate-binding modules promote the enzymatic deconstruction of intact plant cell walls by targeting and proximity effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:15293–15298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005732107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lombard V, Golaconda Ramulu H, Drula E, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42:D490–D495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao Z, Liu H, Wang C, Xu JR. Correction: comparative analysis of fungal genomes reveals different plant cell wall degrading capacity in fungi. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kubicek CP, Starr TL, Glass NL. Plant cell wall-degrading enzymes and their secretion in plant-pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014;52:427–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-045831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee DK, et al. Metabolic response induced by parasitic plant-fungus interactions hinder amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism in the host. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37434. doi: 10.1038/srep37434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee YH, Dean RA. cAMP regulates infection structure formation in the plant pathogenic fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell. 1993;5:693–700. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.6.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu JR, Hamer JE. MAP kinase and cAMP signaling regulate infection structure formation and pathogenic growth in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2696–2706. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adachi K, Hamer JE. Divergent cAMP signaling pathways regulate growth and pathogenesis in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1361–1374. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.8.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wolanin PM, Thomason PA, Stock JB. Histidine protein kinases: key signal transducers outside the animal kingdom. Genome Biol. 2002;3:REVIEWS3013. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-10-reviews3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hohmann S. Osmotic stress signaling and osmoadaptation in yeasts. Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002;66:300–372. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.66.2.300-372.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jacob S, Foster AJ, Yemelin A, Thines E. Histidine kinases mediate differentiation, stress response, and pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Microbiol. Open. 2014;3:668–687. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bornberg-Bauer E, Alba MM. Dynamics and adaptive benefits of modular protein evolution. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lees JG, Dawson NL, Sillitoe I, Orengo CA. Functional innovation from changes in protein domains and their combinations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016;38:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pawson T, Scott JD. Signaling through scaffold, anchoring, and adaptor proteins. Science. 1997;278:2075–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rubin GM. The draft sequences. Comparing species. Nature. 2001;409:820–821. doi: 10.1038/35057277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen RE, Thorner J. Function and regulation in MAPK signaling pathways: lessons learned from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1773:1311–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dixon KP, Xu JR, Smirnoff N, Talbot NJ. Independent signaling pathways regulate cellular turgor during hyperosmotic stress and appressorium-mediated plant infection by Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell. 1999;11:2045–2058. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.10.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Morschhauser J. Regulation of multidrug resistance in pathogenic fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2010;47:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.de Waard MA. Significance of ABC transporters in fungicide sensitivity and resistance. Pestic. Sci. 1997;51:271–275. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9063(199711)51:3<271::AID-PS642>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pitkin JW, Panaccione DG, Walton JD. A putative cyclic peptide efflux pump encoded by the TOXA gene of the plant-pathogenic fungus Cochliobolus carbonum. Microbiology. 1996;142:1557–1565. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-6-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moktali V, et al. Systematic and searchable classification of cytochrome P450 proteins encoded by fungal and oomycete genomes. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:525. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Casadevall A. Determinants of virulence in the pathogenic fungi. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007;21:130–132. doi: 10.1016/j.fbr.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kelly SL, Kelly DE. Microbial cytochromes P450: biodiversity and biotechnology. Where do cytochromes P450 come from, what do they do and what can they do for us? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2013;368:20120476. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hoffmeister D, Keller NP. Natural products of filamentous fungi: enzymes, genes, and their regulation. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:393–416. doi: 10.1039/b603084j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shin J, Kim JE, Lee YW, Son H. Fungal cytochrome P450s and the P450 complement (CYPome) of Fusarium graminearum. Toxins (Basel) 2018;10:112. doi: 10.3390/toxins10030112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.