Abstract

The association between the gut microbiota and the development of lupus is unclear. We investigated alterations in the gut microbiota after induction of lupus in a murine model using viral peptide of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV). Three treatment arms for the animals were prepared: intraperitoneal injection of HCMVpp65 peptide, adjuvant alone, and PBS injection. Feces were collected before and after lupus induction biweekly for 16S rRNA sequencing. HCMVpp65 peptide immunization induced lupus-like effects, with higher levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies, creatinine, proteinuria, and glomerular damage, compared with mice treated with nothing or adjuvant only. The Simpson diversity value was higher in mice injected with HCMVpp65 peptide, but there was no difference in ACE or Chao1 among the three groups. Statistical analysis of metagenomic profiles showed a higher abundance of various families (Saccharimonadaceae, Marinifiaceae, and Desulfovibrionaceae) and genera (Candidatus Saccharimonas, Roseburia, Odoribacter, and Desulfovibrio) in HCMVpp65 peptide-treated mice. Significant correlations between increased abundances of related genera (Candidatus Saccharimonas, Roseburia, Odoribacter, and Desulfovibrio) and HCMVpp65 peptide immunization-induced lupus-like effects were observed. This study provides insight into the changes in the gut microbiota after lupus onset in a murine model.

Subject terms: Experimental models of disease, Microbiome, Systemic lupus erythematosus

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a prototype of systemic autoimmune diseases characterized by persistent chronic inflammation and production of autoantibodies, particularly anti-dsDNA antibodies. It also results in dysregulation of cytokines, leading to severe and irreversible tissue injury1,2. Although the etiology is uncertain, genetic, environmental, hormonal, and epigenetic factors are associated with SLE development3–5. The mammalian gut is colonized by trillions of microorganisms that shape intestinal microbial diversity, collectively known as the microbiota6. The reciprocal interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the host immune system maintains tissue homeostasis7–9. Therefore, autoimmune diseases such as SLE may be associated with changes in the gut microbiota.

A recent cross-sectional study confirmed decreases in species richness diversity and taxonomic complexity in the feces of lupus nephritis patients compared with controls10. Other human evidence also links gut microbiota changes to the presence of serum antinuclear antibodies and changes in inflammatory cytokines associated with SLE progression11,12. In animal studies, altered microbial community structure and greater bacterial diversity have been reported in SLE13,14. Increased relative abundances of Lachnospiraceae and Rikenellaceae were reported to be associated with the severity of murine lupus, suggesting that the gut microbiota significantly influences the host immune system and effectively affects the development of SLE15,16. The interplay between dietary tryptophan intake and microbial dysbiosis in lupus-susceptible mice could contribute to the exacerbation of lupus17. Pattern changes in intestinal microorganisms or the presence of specific bacterial genera in the gut are associated with immune responses related to lupus.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a virus linked to the development of SLE in humans, accelerates lupus-like disease in murine models18,19. Anti-dsDNA antibody production, proteinuria, and glomerular attack have been reported in mice that received CMVpp65 or its fragment18,20. In this study, we used HCMVpp65 peptide to immunize NZB/W F1 mice to induce lupus-like effects. We investigated the dynamics of the fecal microbiota associated with lupus-like effects in HCMVpp65422-439-immunized mice, compared with mice treated with PBS or adjuvant only.

Results

HCMVpp65422-439 immunization induces lupus-like activity in NZB/W F1 mice

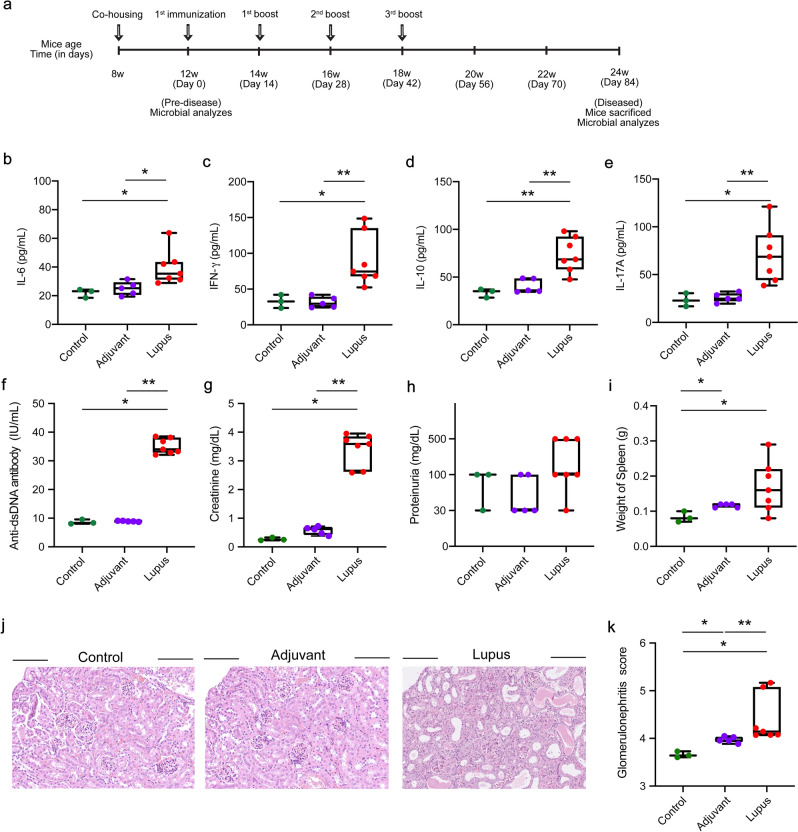

HCMVpp65422-439 immunization induces anti-dsDNA autoantibodies and initiates glomerulonephritis in non-autoimmune prone mice21. To investigate alterations in fecal microbiota-associated viral peptide-induced lupus-like activities, we conducted HCMVpp65422-439 immunization of NZB/W F1 mice at 12 weeks of age and evaluated the lupus-like effects (Fig. 1a). The experiment timeline is shown in Fig. 1a. The serum levels of IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-17A were higher in HCMVpp65422-439-immunized mice at 12 weeks post-immunization (24 weeks of age, lupus group) compared with NZB/W F1 mice treated with PBS (control group) or adjuvant only (adjuvant group, Fig. 1b–e). Anti-dsDNA antibody, serum creatinine, and proteinuria levels were elevated in the lupus group at 12 weeks post-immunization (24 weeks of age, Fig. 1f–h). Moreover, the lupus group had larger spleens, more severe renal damage, and a higher glomerulonephritis score compared with the other two groups (Fig. 1i–k). These findings suggest that HCMVpp65422-439 immunization induced lupus-like effects.

Figure 1.

Induction of lupus-like effects in NZB/W F1 mice. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with HCMVpp65422-439 peptide, adjuvant, or PBS only. (a) Schematic of the experiment. Serum (b) IL-6, (c) IFN-γ, (d) IL-10, and (e) IL-17A levels in the lupus (n = 7), adjuvant (n = 5), and control (n = 3) groups at 12 weeks post immunization (24 weeks of age). The levels of (f) anti-dsDNA antibody (g) serum creatinine, and (h) proteinuria in blood and urine from the control, adjuvant, and lupus groups at 12 weeks post-immunization. (i) Representative photograph and diagram of spleen size. Data are means ± SEM. (j) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of glomeruli from the control, adjuvant, and lupus groups. (k) Glomerulonephritis score of renal lesions. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01. Full images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Microbial composition in NZB/W F1 mice

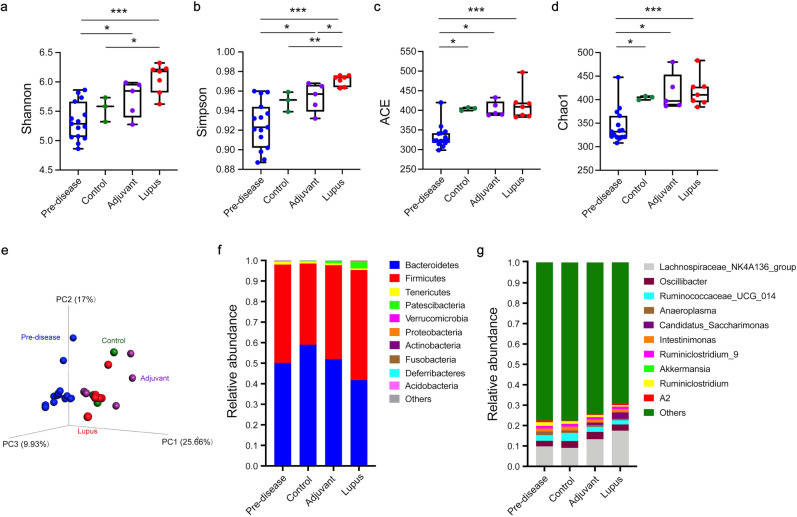

To investigate the microbial community in NZB/W F1 mice, we analyzed fecal samples collected before immunization (predisease, 12 weeks of age) and at disease time points (lupus, adjuvant, and control groups, 24 weeks of age) by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The alpha and beta diversities were measured to evaluate alterations in microbial composition. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, the lupus group had significantly higher Shannon’s (P = 0.033) and Simpson’s (P = 0.008) diversity index values (extent of microbial diversity), but there was no difference in the ACE or Chao1 index values (extent of microbial richness), compared with the control group. A higher Simpson’s index value was found in the lupus group than in the adjuvant group. Microbial diversity and richness did not differ significantly between the adjuvant and control groups (Fig. 2a–d). For beta diversity analysis, the pattern variations in the microbial community structure among the lupus, adjuvant, and control groups are listed in Table 1. The three-dimensional principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot showed distinctions in community composition among the four groups (Fig. 2e). PC1, PC2, and PC3 showed 9.93%, 17%, and 25.66% of the total variance in microbial species, respectively (Fig. e). PCoA of the Bray–Curtis distance matrix revealed differences in microbial community composition among the lupus, adjuvant, and control groups (Supplementary Fig. 2). Figure 2f, g shows the relative abundances of the top 10 bacterial phyla and genera. At the phylum level, Bacteroidetes (59.0%) was the most abundant in the control group, followed by Firmicutes (39.5%), Tenericutes (1.0%), and Patescibacteria (0.3%) (Fig. 2f). The lupus group, compared with the adjuvant group, had increased abundances of Firmicutes (53.5% vs. 45.7%), Patescibacteria (3.1% vs. 1.7%), and Proteobacteria (0.6% vs. 0.007%) and decreased abundances of Bacteroidetes (41.8% vs. 52%) and Tenericutes (0.7% vs. 0.9%). At the genus level, the genera (top 10) in the relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group (f_ Lachnospiraceae), Oscillibacter (f_Oscillospiraceae), Ruminococcaceae UCG 014 (f_ Ruminococcaceae), Intestinimonas, Candidatus Saccharimonas (f_ Saccharimonadaceae), Ruminiclostridium, Ruminiclostridium 9 (f_ Ruminococcaceae), and Anaeroplasma (f_Anaeroplasmataceae) were observed in the four groups (Fig. 2g). The total percentages of the top 10 genera were 22.6%, 22.4%, 25.5%, and 31.0% in the predisease, control, adjuvant, and lupus groups, respectively.

Figure 2.

Microbial community structure. (a) Shannon, (b) Simpson, (c) ACE, and (d) Chao1 alpha diversity indices analyzed by the Kruskal–Wallis test. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA and Student’s t-test. The beta diversity of (e) principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was evaluated by unweighted UniFrac and Bray–Curtis distances. Relative distributions of the top 10 (f) phyla and (f) genera. Data are means ± SEM. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Statistical differences in microbial community structure between two groups.

| Groups | MRPP | Adonis | Anosim | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-Δ | P | R2 | P | R | P | |

| Adjuvant vs. control | 0.36 | 1.8E−2 | 0.21 | 6.3E−2 | 0.11 | 3.0E−1 |

| Adjuvant vs. lupus | 0.45 | 2.0E−3 | 0.30 | 9.0E−4 | 0.66 | 3.0E−3 |

| Control vs. lupus | 0.45 | 1.3E−2 | 0.35 | 1.4E-2 | 0.58 | 1.9E−2 |

Three different tests were performed using MRPP, Adonis, and Anosim and were based on the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index. E-Δ, expected-delta.

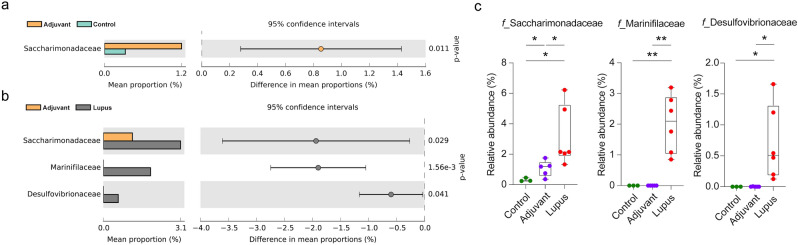

Altered microbial families and genera associated with HCMVpp65422-439 immunization

The families and genera with significant changes in relative abundance are shown in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. At the family level, the abundance of Saccharimonadaceae was increased in the adjuvant group compared with control group (Fig. 3a). The lupus group had higher relative abundances of the families Saccharimonadaceae (3.1%), Marinifiaceae (2.0%), and Desulfovibrionaceae (0.7%) compared with the adjuvant and control groups (Fig. 3b, c). The average Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio was increased in the lupus group (1.72 ± 0.49) compared with the control (0.72 ± 0.22) and adjuvant (0.89 ± 0.23) groups (Supplementary Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Relative abundance of fecal microbiota families. The abundances of family groups in the (a) adjuvant vs. control and (b) adjuvant vs. lupus groups analyzed by Welch’s t-test using STAMP software. (c) Families with higher abundances in the lupus compared with the adjuvant and control groups. * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01.

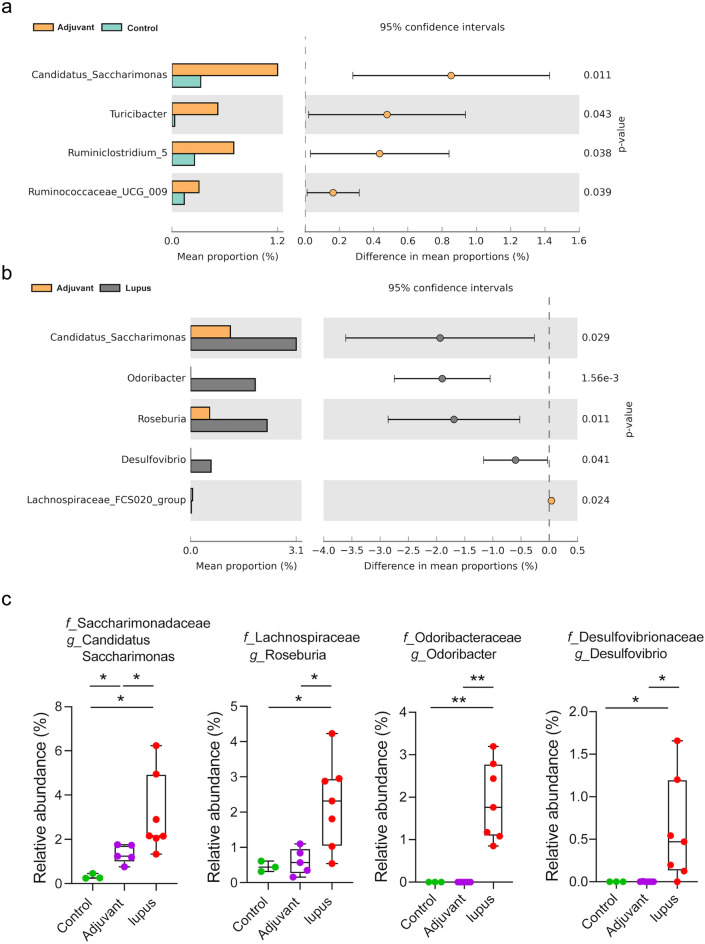

Figure 4.

Relative abundance of genera in the fecal microbiota. The abundance of genera in the (a) adjuvant vs. control and (b) adjuvant vs. lupus groups analyzed by Welch’s t-test using STAMP software. (c) Genera with significantly higher relative abundances in the lupus compared with the adjuvant and control groups. * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01.

At the genus level, the abundances of Candidatus Saccharimonas, Turicibacter, Ruminiclostridium 5, and Ruminococcaceae UCG-009 were increased in the adjuvant group compared with the control group (Fig. 4a). The abundances of Candidatus Saccharimonas (f_Saccharimonadaceae), Odoribacter (f_ Odoribacteraceae), Roseburia (f_Lachnospiraceae), and Desulfovibrio (f_Desulfovibrionaceae) were higher in the lupus group than control group (Fig. 4b). Notably, Candidatus Saccharimonas (3.1%), Roseburia (2.3%), Odoribacter (1.9%), and Desulfovibrio (0.7%) had higher abundances in the lupus group compared with the other two groups (Fig. 4c). The abundances of the families Akkermansiaceae and Lactobacillaceae were decreased in the three groups at 12 weeks post-immunization, but the difference in Lactobacillaceae abundance was not significant (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (> 3) showed differential abundances between the lupus vs. adjuvant and lupus vs. control group comparisons (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Functional prediction of microbial communities associated with lupus-like effects in HCMVpp65422-439 immunization

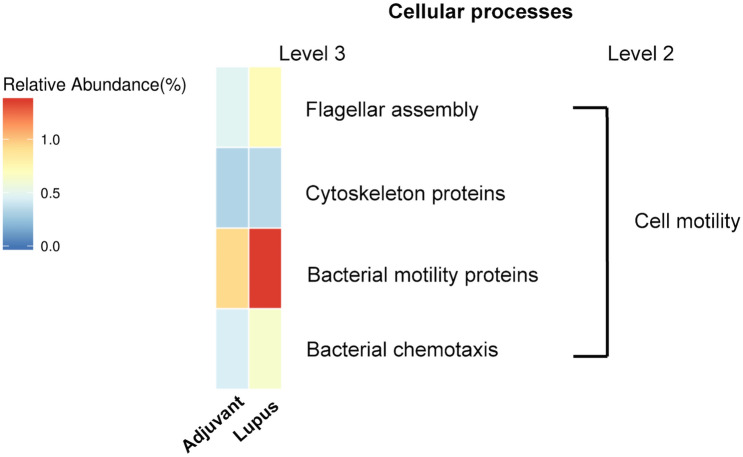

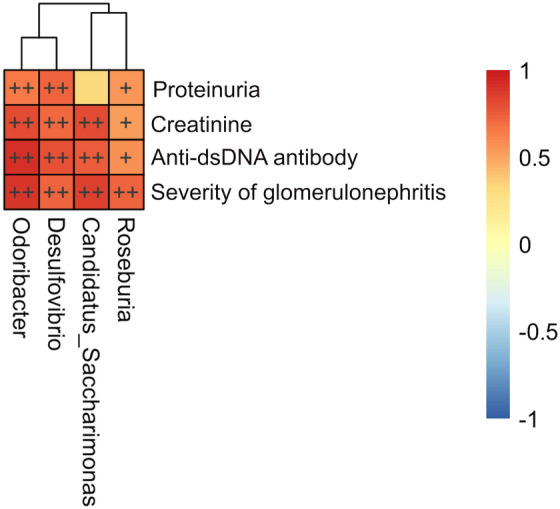

We predicted the functional potential of microbial communities by phylogenetic reconstruction of unobserved states (PICRUSt)22. Several pathways related to cell motility were differentially expressed between the adjuvant and lupus groups (Fig. 5). Also, genetic markers with significant discriminative power in cellular processes, including lysosomes, flagellar assembly, cytoskeleton proteins, bacterial motility proteins, and bacterial chemotaxis, were detected. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to infer the associations between the fecal microbial genera and lupus-like effects. Statistically significant positive correlations between microbial genera and lupus-like effects were identified (Fig. 6). All four lupus-like effects were correlated positively with Odoribacter, Desulfovibrio, and Roseburia. Candidatus Saccharimonas showed significant positive correlations with the creatinine level, anti-dsDNA IgG titer, and glomerulonephritis severity (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Metagenomic taxonomic profiling of microbial communities in the adjuvant and lupus groups by phylogenetic reconstruction of unobserved states (PICRUSt).

Figure 6.

Spearman’s rank correlation between relative genera abundance and lupus-like effects in the lupus group. Heat map based on the correlation coefficient values. + P < 0.05 and + + P < 0.01.

Discussion

Alterations in the microbiota composition are related to the development of SLE23. We found that fecal microbial alterations are associated with lupus-like effects in NZB/W F1 mice. HCMVpp65422-439 immunization accelerated lupus progression and exacerbated glomerulonephritis. The lupus group had a significantly altered microbiota composition and bacterial community compared with the adjuvant and control groups. This suggests that the abundances of significantly altered microbial families (Saccharimonadaceae, Marinifilaceae, and Desulfovibrionaceae) and genera (Candidatus Saccharimonas, Roseburia, Odoribacter, and Desulfovibrio) in the lupus group may be associated with HCMVpp65 peptide-induced lupus-like effects in NZB/W F1 mice.

Significant increases in the abundances of the families Clostridiaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Desulfovibrionaceae, and Rikenellaceae and a decrease in that of Akkermansia muciniphila have been described24. Moreover, the same group reported increased abundances of Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Rikenellaceae and a decreased abundance of Lactobacillaceae in MRL/lpr mice at the disease stage16. The higher relative abundance of the Rikenellaceae family in SNF1 lupus mice is associated with more severe lupus symptoms15. Increased Lactobacillales in the gut of MRL/lpr mice was linked to improved renal function and an increased survival rate25. The Lactobacillaceae and Akkermansiaceae families reportedly exert an anti-inflammatory effect by increasing the IL-10 level and decreasing that of IL-6 and play a crucial role in microbiota remodeling26–28. In this study, the families Saccharimonadaceae, Marinifilaceae, and Desulfovibrionaceae were more abundant in the lupus group than the adjuvant group. The abundances of Akkermansiaceae and Lactobacillaceae were decreased in the three groups at 12 weeks post-immunization. Of note, increased abundances of Saccharimonadaceae and Marinifilaceae are positively correlated with the levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-629. An association between an increased relative abundance of the Desulfovibrionaceae family and Th17 expression was found in patients with multiple sclerosis30. A significant change in phylogenetic diversity and bacterial community structure were found in the lupus group, which may be related to an increased risk of inflammatory diseases.

At the genus level, we observed increased abundances of the genera Candidatus Saccharimonas, Roseburia, Odoribacter, and Desulfovibrio in the lupus group. These microbial genera are linked to host immune regulation and autoimmune diseases. The increased abundances of Candidatus Saccharimonas, and Roseburia in colitis are reportedly associated with reduced IL-17 and TNF-α expression31–33. Moreover, Roseburia may promote regulatory T-cell differentiation and reduce the expression of IL-17 in inflammatory bowel disease33. In contrast, the abundances of the genera Odoribacter and Desulfovibrio are increased in several autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and inflammatory bowel disease34–36, likely due to an increased level of IL-17 and number of CD4+ Th17 cells. Accordingly, we examined the serum levels of IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-17A at 12 weeks post-immunization (24 weeks of age, disease stage). The IL-6 and IL-17A levels were significantly higher in the lupus group compared with the adjuvant and control groups. This result suggests a correlation between elevated concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines and changes in the gut microbial composition of lupus mice.

Odoribacter encompasses several intestinal butyrate-producing species37. Butyrate produced by microbial fermentation provides energy for epithelial cells, maintains the integrity of the intestinal barrier, and promotes the differentiation of regulatory T cells. Several species of the genus Odoribacter are reportedly decreased in abundance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and in lupus animal models24,38. In addition, the abundance of Desulfovibrio was decreased in the gut of MRL/lpr mice, and that of Blautia was increased39. A recent study involved both an animal model and patients with anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS); in the human component, cross-reactive T/B lymphocytes and antibodies against the homogenous region expressed by the gut commensal Roseburia intestinalis40. In the animal component, immunization of normal mice with R. intestinalis and fecal microbiota transplantation in a murine model of spontaneous APS (NZW × BXSB) F1 induced an inflammatory reaction and cross-reactivity to beta-2-glycoprotein I. R. intestinalis is a trigger of APS. The discrepant results are likely due to differences in study design, enrolment criteria, and animal species and care.

The F/B ratio showed an increasing trend in NZB/W F1 mice at the disease stage (12 weeks post immunization). Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are the predominant phyla in the human gut and have critical roles in modulating inflammation and immune status41,42. Bacteroidetes mediate intestinal mucosal barrier function and reduce inflammation43,44. Firmicutes can increase production of lipopolysaccharide, which enters the bloodstream and triggers chronic inflammation45,46. An elevated F/B ratio in abundant fecal microbiota is suggested to promote a proinflammatory environment and characteristics of multiple sclerosis30,47. The gut microbiota F/B ratio is not significantly different between SLE patients and non-SLE controls24. By contrast, SLE patients in remission had significantly lower F/B ratios than healthy individuals48. The correlation between the gut microbiota F/B ratio and disease is unclear.

This study has several limitations. Long term co-housing of mice may result in hybrid microbiota animals or cage effects. Taking advantage of coprophagy, co-housing gnotobiotic animals shortly before immunization can reduce bias in gut microbiota analysis49. We were unable to eliminate the cage effect, despite co-housing of mice before lupus induction. Moreover, the small population and disease severity may have caused bias. However, our results are consistent with prior reports of the microbiota composition in murine lupus models, and we observed significantly higher species and microbial community diversity. Therefore, specific bacterial community compositions may be linked to the development of autoimmune diseases.

NZBW F1 mice that received HCMVpp65 peptide developed a high anti-dsDNA antibody level, serum creatinine level, and proteinuria, which were accompanied by changes in bacterial populations at 24 weeks of age. Luo reported that the bacterial genera Clostridium, Dehalobacterium, Lactobacillus, Oscillospira, Dorea (f_Lachnospiraceae), Bilophila (f_Desulfovibrionaceae), and AF12 (f_Rikenellaceae) were present from the pre-disease stage (10–18 weeks of age) to the disease stage (23–33 weeks of age)24. The abundances of the families Lachnospiraceae and Desulfovibrionaceae were increased. Therefore, immunization of NZBW F1 mice with HCMVpp65 peptide not only accelerated lupus disease but also influenced the microbiota composition. Our results do not provide insight into the causality of the relationship between lupus acceleration and microbial changes, and so further studies are needed.

We investigated the association between lupus-like effects and changes in the fecal microbiota in NZB/W F1 mice. The lupus group exhibited higher microbial diversity and increased abundances of several families (Desulfovibrionaceae, Saccharimonadaceae, and Marinifilaceae) and genera (Candidatus Saccharimonas, Roseburia, Odoribacter, and Desulfovibrio). The fecal microbiota composition of viral peptide-induced NZB/W F1 lupus mice differed markedly from the controls.

Methods

Synthetic peptides

The purity of synthetic HCMVpp65422-439 peptides (GGGAMAGASTSAGRKRKS) was > 99%, as per the manufacturer’s guarantee (GenScript Biotech Corp, Piscataway, NJ). The HCMVpp65 peptide was prepared and stored according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

NZB/W F1 mice and induction of lupus-like effects

The animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chang Gung Medical Foundation (#2016062804 and #2018121402). NZB/W F1 female mice (3–5 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory Co., Ltd. and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal center at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. After 30 days of adaptive feeding and co-housing, the NZB/W F1 mice were separated into the control group (n = 3), adjuvant group (injected with adjuvant only, n = 5), and lupus group (induced by HCMVpp65422-439, n = 7). The mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free room under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle with stable humidity. The immunization schedule was as described previously20. Immunization was performed from 12 to 14 weeks of age. On day 1, the NZB/W F1 mice received intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg HCMVpp65422-439 emulsified with complete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog Number F5881). Boosting was performed using HCMVpp65422-439 in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog Number: F5506) or PBS on days 14, 28, and 42. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the ARRIVE guidelines.

Serum, urine, and stool collection

Stool, urine, and blood were harvested from mice once every 2 weeks. For blood collection, mice were bled from the retro-orbital vein sinus, and plasma was collected by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C and stored at − 80 °C. Fresh stool and urine samples were collected from mice and preserved in micro-tubes, which were immediately transferred to liquid nitrogen.

Measurement of cytokines

Serum levels of IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-17A were measured using ELISA kits (Abnova, Taipei City, Taiwan; KA4983, KA4813, KA3070, and KA3074) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Evaluation of lupus-like effects in NZB/W F1 mice

Lupus-like activity was evaluated by serum indices and kidney pathological analysis using ELISA and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining50. Briefly, the serum level of creatinine was measured using the ELISA Test Kit (MyBioSource, MBS751125 and MBS763433, San Diego, CA). The serum anti-dsDNA autoantibody titer was evaluated using the anti-dsDNA ELISA Kit (Inova Diagnostics, catalog number: 708510, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The proteinuria level was examined using a proteinuria strip (Medi-Test Combi 10 VET strip, MACHEREY–NAGEL, Allentown, PA). Glomerular abnormalities were evaluated as described previously21. Briefly. the number of abnormalities in 100 glomeruli within a 5-μm-thick H&E-stained paraffin section of the kidney was recorded. Glomerular abnormalities were scored as follows: normal glomeruli (score 1), pure mesangial alterations (score 2), focal segmental glomerulonephritis (score 3), diffuse glomerulonephritis (score 4), diffuse membranous glomerulonephritis (score 5), and advanced sclerosing glomerulonephritis (score 6), based on the 1982 classification of the World Health Organization51.

H&E staining

H&E staining was conducted according to the Cold Spring Harbor protocols with slight modifications50. Frozen kidney sections were immersed in 100% ethanol for 30 s and rinsed 10 times in double-distilled H2O. Slides were transferred to hematoxylin for 5 min and washed five times in 0.1% HCl. After washing in tap water for 5 s, the slides were washed five times in 0.1% NH4OH and five times in tap water. The slides were stained with eosin for 3 min and immersed in 100% ethanol with 0.1% acetic acid, 100% ethanol I, 100% ethanol II, acetone I, acetone II, xylene I, and xylene II five times each. After dehydration, the slides were mounted, covered with a cover glass, and visualized by microscopy (Olympus IX73/DP72, cellSens Standard software).

Microbial DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing

Microbial DNA was extracted from fecal pellets using the DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of DNA extracts were determined by agarose gel electrophoresis (0.8% w/v agarose) and the NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by 16S rRNA sequencing.

Data analysis and bioinformatics

Data analysis was performed using a modified protocol of Chi-Cheng Huang52. Amplicon sequencing was performed using 300-bp paired-end raw reads and assembled using FLASH v. 1.2.753. De-multiplexing was conducted based on barcode identification. For quality control, Q < 20 reads were discarded from the pipeline of QIIME (v. 1.9.1)54. If three consecutive bases had Q < 20, the read was classified as truncated. The read was preserved in the data set if it contained > 75% of the original length using split_libraries_fastq.py script in QIIME55. Using UCHIME algorithms, sequences were checked for chimeras to acquire the effective tags and were filtered from the data set using the UPARSE function in the peptide of USEARCH (v. 7)56–59. The operational taxonomic unit (OTU) abundance was normalized to the variation and rarefied to the minimum sequence depth using the QIIME script (single_rarefaction.py). Subsequently, analysis of alpha and beta diversities was performed using the normalized data. Alpha diversity indicated the species complexity within individual samples based on seven different criteria outputs from the QIIME pipeline, including observed OTUs and the Shannon, Simpson, Chao1, and ACE indices60. Observed OTUs reflect the number of different species identified in the microbial community. The Chao1 and ACE indices used to evaluate community richness and the relative abundance and evenness accounting for diversity were assessed using the Shannon and Simpson indices. Beta diversity analysis was conducted to evaluate the differences in species complexity across samples. PCoA was performed using the distance matrix to acquire principal coordinates for visualization of sophisticated and multi-dimensional data61. The PCoA of the Bray–Curtis distance was analyzed according to OTU level for microbiota beta diversity.

For statistical analysis, the significance of all microbial species within groups at various levels of taxonomy was detected by differential abundance analysis using a zero-inflated Gaussian log-normal model executed in the “fitFeatureModel” function of the Bioconductor metagenomeSeq package62. Welch’s t-test was performed using Statistical Analysis of Metagenomic Profiles (STAMP) software (v. 2.1.3)63. Anosim and MRPP analyses were used to determine whether the community structures significantly differed among and within groups. Significant biomarkers were evaluated by LDA of effect size using the non-parametric factorial Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test and LDA to assess differences in taxon abundance between two groups. For functional analysis, functional abundances from 16S rRNA sequencing data were analyzed to predict functional genes using PICRUSt (v. 1.1.1)22. Two-tailed and unpaired Fisher’s tests and paired Student’s t-test with graphs depicting the mean ± three standard errors of the mean (SEM) were used for comparisons between two groups. All statistical tests were conducted with a two-sided 5% level of significance (* P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001) using SAS statistical software (v. 9.4, SAS Institute).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Wan-Ting Su and Wei-Ling Chang for their technical support.

Author contributions

A.H.H., L.C.W., W.Y.T., and C.F.K. designed the project. A.H.H., L.C.W., Y.F.C., Y.J.H., and Y.C.T. performed the experiments, acquired the data, and interpreted the results. A.H.H., Y.J.H., and Y.C.T. prepared the figures. A.H.H., K.H.Y., C.F.K., and S.F.L. participated in the interpretation of the results and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript, approved the final version to be published, and accepted responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was supported by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG3G0851, CMRPG3H1393, and CMRPG3F1703) and the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (108-2314-B-182A-064). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories (Sequence Read Archive data, accession: PRJNA693398).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yen-Fu Chen and Ao-Ho Hsieh.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Chang-Fu Kuo and Kuang-Hui Yu.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-02422-9.

References

- 1.Arbuckle MR, et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:1526–1533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wahren-Herlenius M, Dorner T. Immunopathogenic mechanisms of systemic autoimmune disease. Lancet. 2013;382:819–831. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60954-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tektonidou MG, Wang Z, Dasgupta A, Ward MM. Burden of serious infections in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus: a national population-based study, 1996–2011. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:1078–1085. doi: 10.1002/acr.22575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun C, et al. High-density genotyping of immune-related loci identifies new SLE risk variants in individuals with Asian ancestry. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:323–330. doi: 10.1038/ng.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scharer CD, et al. Epigenetic programming underpins B cell dysfunction in human SLE. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:1071–1082. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0419-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ley RE, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell. 2006;124:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stecher B, Hardt WD. Mechanisms controlling pathogen colonization of the gut. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011;14:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He B, et al. Intestinal bacteria trigger T cell-independent immunoglobulin A(2) class switching by inducing epithelial-cell secretion of the cytokine APRIL. Immunity. 2007;26:812–826. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuwahara T, et al. Genomic analysis of Bacteroides fragilis reveals extensive DNA inversions regulating cell surface adaptation. PNAS. 2004;101:14919–14924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404172101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azzouz D, et al. Lupus nephritis is linked to disease-activity associated expansions and immunity to a gut commensal. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019;78:947–956. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaudreau MC, Johnson BM, Gudi R, Al-Gadban MM, Vasu C. Gender bias in lupus: does immune response initiated in the gut mucosa have a role? Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2015;180:393–407. doi: 10.1111/cei.12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez P, et al. Th17 responses and natural IgM antibodies are related to gut microbiota composition in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24072. doi: 10.1038/srep24072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mu Q, et al. Antibiotics ameliorate lupus-like symptoms in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13675. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14223-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman GJ. The microbiome in SLE pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2019;15:72–74. doi: 10.1038/s41584-018-0152-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson BM, Gaudreau MC, Al-Gadban MM, Gudi R, Vasu C. Impact of dietary deviation on disease progression and gut microbiome composition in lupus-prone SNF1 mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2015;181:323–337. doi: 10.1111/cei.12609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Liao X, Sparks JB, Luo XM. Dynamics of gut microbiota in autoimmune lupus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:7551–7560. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02676-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi SC, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis and altered tryptophan catabolism contribute to autoimmunity in lupus-susceptible mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang M, Pan MR, Chen DY, Lan JL. Human cytomegalovirus pp65 lower matrix protein: a humoral immunogen for systemic lupus erythematosus patients and autoantibody accelerator for NZB/W F1 mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2006;143:167–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02974.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sebastiani GD, Iuliano A, Canofari C, Bracci M. Cytomegalovirus infection in systemic lupus erythematosus: report of four cases challenging the management of the disease, and literature review. Lupus. 2019;28:432–437. doi: 10.1177/0961203319825570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh AH, et al. B cell epitope of human cytomegalovirus phosphoprotein 65 (HCMV pp65) induced anti-dsDNA antibody in BALB/c mice. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017;19:65. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1268-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh AH, et al. Human cytomegalovirus pp65 peptide-induced autoantibodies cross-reacts with TAF9 protein and induces lupus-like autoimmunity in BALB/c mice. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:9662. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66804-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langille MG, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collison J. Gut microbiota linked to kidney disease in SLE. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2019;15:188. doi: 10.1038/s41584-019-0196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo XM, et al. Gut microbiota in human systemic lupus erythematosus and a mouse model of lupus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018 doi: 10.1128/AEM.02288-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mu Q, et al. Control of lupus nephritis by changes of gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2017;5:73. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0300-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klaenhammer TR, Kleerebezem M, Kopp MV, Rescigno M. The impact of probiotics and prebiotics on the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:728–734. doi: 10.1038/nri3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanninen A, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila induces gut microbiota remodelling and controls islet autoimmunity in NOD mice. Gut. 2018;67:1445–1453. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhai R, et al. Strain-specific anti-inflammatory properties of two Akkermansia muciniphila strains on chronic colitis in mice. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2019;9:239. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhai Z, et al. Cecropin A alleviates inflammation through modulating the gut microbiota of C57BL/6 mice with DSS-induced IBD. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1595. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tremlett H, et al. Gut microbiota in early pediatric multiple sclerosis: a case-control study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2016;23:1308–1321. doi: 10.1111/ene.13026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren W, et al. Interferon tau affects mouse intestinal microbiota and expression of IL-17. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:2839232. doi: 10.1155/2016/2839232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He X, et al. Cultivation of a human-associated TM7 phylotype reveals a reduced genome and epibiotic parasitic lifestyle. PNAS. 2015;112:244–249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419038112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu C, et al. Roseburia intestinalis inhibits interleukin17 excretion and promotes regulatory T cells differentiation in colitis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018;17:7567–7574. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, et al. Role of the gut microbiome in modulating arthritis progression in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:30594. doi: 10.1038/srep30594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stebbings S, et al. Comparison of the faecal microflora of patients with ankylosing spondylitis and controls using molecular methods of analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:1395–1401. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.12.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fox JG, et al. Intracellular Campylobacter-like organism from ferrets and hamsters with proliferative bowel disease is a Desulfovibrio sp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1994;32:1229–1237. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1229-1237.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anand S, Kaur H, Mande SS. Comparative in silico analysis of butyrate production pathways in gut commensals and pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1945. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun Y, et al. Characteristics of gut microbiota in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Shanghai, China. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2019;9:369. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen BD, et al. An autoimmunogenic and proinflammatory profile defined by the gut microbiota of patients with untreated systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:232–243. doi: 10.1002/art.41511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruff WE, et al. Pathogenic autoreactive T and B cells cross-react with mimotopes expressed by a common human gut commensal to trigger autoimmunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:100–113. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turnbaugh PJ, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong ML, et al. Inflammasome signaling affects anxiety- and depressive-like behavior and gut microbiome composition. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:797–805. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delday M, Mulder I, Logan ET, Grant G. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron ameliorates colon inflammation in preclinical models of Crohn's disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019;25:85–96. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fan H, et al. Bacteroides fragilis strain ZY-312 defense against Cronobacter sakazakii-induced necrotizing enterocolitis in vitro and in a neonatal rat model. mSystems. 2019 doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00305-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cani PD, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mehta NN, et al. Experimental endotoxemia induces adipose inflammation and insulin resistance in humans. Diabetes. 2010;59:172–181. doi: 10.2337/db09-0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tremlett H, et al. Associations between the gut microbiota and host immune markers in pediatric multiple sclerosis and controls. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:182. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0703-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hevia A, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. MBio. 2014;5:e01548-01514. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01548-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caruso R, Ono M, Bunker ME, Nunez G, Inohara N. Dynamic and asymmetric changes of the microbial communities after cohousing in laboratory mice. Cell Rep. 2019;27:3401–3412. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fischer AH, Jacobson KA, Rose J, Zeller R. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. CSH Protoc. 2008 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weening JJ, et al. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. Kidney Int. 2004;65:521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang CC, et al. Gut butyrate-producing organisms correlate to placenta specific 8 protein: Importance to colorectal cancer progression. J. Adv. Res. 2020;22:7–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2019.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Magoc T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bokulich NA, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:57–59. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haas BJ, et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011;21:494–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.112730.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lozupone CA, Knight R. Species divergence and the measurement of microbial diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008;32:557–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang XT, et al. Illumina sequencing of 16S rRNA tag revealed spatial variations of bacterial communities in a mangrove wetland. Microb. Ecol. 2013;66:96–104. doi: 10.1007/s00248-013-0238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paulson JN, Stine OC, Bravo HC, Pop M. Differential abundance analysis for microbial marker-gene surveys. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1200–1202. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parks DH, Tyson GW, Hugenholtz P, Beiko RG. STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3123–3124. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories (Sequence Read Archive data, accession: PRJNA693398).