Abstract

At home self- and partner-testing may reduce HIV and syphilis transmission by detecting undiagnosed infections. Forty-eight cisgender men and transgender women who men who have sex with men were given ten INSTI Multiplex kits and downloaded the SMARTtest app to facilitate self- and partner testing over the next three months. Thirty-seven (77%) participants self-tested using the INSTI (Mean=3.7 times, SD=3.9); 26 (54%) tested partners (Mean=1.6 times, SD=2.2). Participants liked the test for its ease of use, quick results, and dual HIV/syphilis testing but its blood-based nature hindered use with partners. Participants with reactive syphilis results always attributed them to a past infection and these results presented a challenge to testing with partners and the ability to accurately assess risk of infection. Most participants stated they would use the INSTI for self-testing (100%) and for partner-testing (89%). Acceptability of the SMARTtest app was high for functionality (M=4.16 of max 5, SD=0.85) and helpfulness (M=6.12 of max 7, SD=1.09). Participants often used the app as needed, eschewing its use if they felt comfortable conducting the test and interpreting its results. Seventy-eight percent would recommend the app to a friend. Availability of the INSTI Multiplex as a self-test with the accompanying SMARTtest app might increase frequency of HIV and syphilis testing, allowing for earlier detection of infection and reduced transmission.

RESUMEN

El uso de pruebas rápidas caseras con parejas y como auto-pruebas puede reducir la transmisión del VIH y la sifilis al detectar infecciones no diagnosticadas. Cuarenta y ocho hombres cisgénero y mujeres transgénero que tienen sexo con hombres recibieron diez kits del INSTI Multiplex y descargaron la aplicación SMARTtest para facilitar su uso con parejas y para auto-pruebas durante los próximos tres meses. Treinta y siete (77%) participantes se auto-testearon utilizando el INSTI (Media = 3.7 veces, DE = 3.9); 26 (54%) testearon a sus parejas (media = 1.6 veces, DE = 2.2). A los participantes les gustó la prueba por su facilidad de uso, rapidez de los resultados y por ser una prueba dual de VIH/sífilis, pero al ser una prueba basada en sangre dificultó su uso con parejas. Los participantes con resultados de sífilis reactivos siempre atribuyeron éstos a una infección pasada y sus resultados presentaron un desafío para el uso de pruebas con parejas. La mayoría de los participantes afirmaron que utilizarían el INSTI como auto-pruebas (100%) y para testear a sus parejas (89%). La aceptabilidad de la aplicación SMARTtest fue alta para la funcionalidad (M = 4.16 de un máximo de 5, SD = 0.85) y utilidad (M = 6.13 de un máximo de 7, SD = 1.09). Los participantes solían utilizar la aplicación según fuera necesario, evitando su uso si se sentían cómodos realizando la prueba e interpretando sus resultados. El 78% recomendaría la aplicación a un amigo. La disponibilidad del INSTI Multiplex como auto-prueba con la aplicación SMARTtest podría aumentar la frecuencia de las pruebas de VIH y sífilis, lo que permite una detección más temprana de la infección y reduce la transmisión.

INTRODUCTION

The acceptability of using rapid HIV tests for self- and partner testing is now well established in the literature and is consistent among at risk groups such as men who have sex with men (MSM)[1,2], transgender women (TGW)[3,4], female sex workers [4,-6], and partnered women in sub-Saharan Africa [6,7]. Studies consistently show that self-testing increases frequency of testing among groups at high risk of infection [8,9], while secondary distribution to sexual partners reaches individuals who were not aware of their HIV infection [1,2,6,7]. To date, however, partner-testing studies have used an oral fluid HIV test. Combined HIV/syphilis rapid tests allow for simultaneous testing, an important advantage over single HIV tests given the high prevalence of syphilis [10] and CDC recommendations that individuals at high risk of infection be tested for syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea every three to six months [11]. One challenge to dual tests is that they are blood-based and require a fingerprick to obtain a blood sample to perform the test. Although there is high acceptability of both oral and blood based rapid tests, there is a preference for oral tests [12], notwithstanding beliefs that blood based tests are more accurate [13,14]. This preference for oral based tests disappears for dual tests that provide results for additional sexually transmitted infections (STI) [15]. In this context, understanding how groups at high risk of HIV and syphilis infection might use a dual test is essential to assess its potential for self- and partner-testing.

Facilitating the uptake of such dual test also requires addressing the concerns expressed by potential users about home testing. These include concerns about the accuracy of the test, correct use, correct reading of results, and support in case of reactive results [16-19]. Dedicated smartphone apps are being increasingly considered to address these concerns and facilitate HIV self-testing at home, with a number of apps currently in development or early stages of testing [20-23]. In this burgeoning field, understanding how potential users interact with the apps in a real-world context to facilitate self-testing at home will be key to achieving adoption of the app and self-testing.

This paper presents findings from the SMARTtest Study, in which cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men (MSM and TGW, respectively) were provided with INSTI Multiplex HIV-1/HIV-2/ Syphilis Antibody Tests and an accompanying smartphone app to support self- and partner testing. The INSTI Multiplex is a dual HIV/syphilis rapid test that requires a drop of blood and delivers test results in one minute. It is not currently FDA approved in the U.S. as a self-test or in clinics, although it is available for clinic use in Canada and Europe. An HIV only version of the test is FDA approved for clinic use and a self-test is approved for use in Canada and Europe. The SMARTtest app [24] was designed through rapid user-centered design with the input of MSM and TGW and is available in Android and IOS versions. It provides video and step-by-step pictorial instructions, a scanning feature that translates results of the INSTI Multiplex (i.e., dots) into words (e.g., HIV: Positive; Syphilis: Negative), lets users save or send results to others, and provides location-based resources for follow-up care and information on HIV and syphilis. In this paper, we describe participants’ use of the INSTI Multiplex for self- and partner- testing, including general acceptability, challenges to use, and handling reactive results. We then report on how participants used the SMARTtest app to support use of the INSTI Multiplex.

METHODS

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, which also approved the use of the INSTI Multiplex based on it being considered a minimal risk device. A label stating “For Investigational Purposes Only” was affixed to each INSTI kit provided to participants.

Recruitment

Recruitment was conducted in New York City between February 2019 and December 2019. Participants were recruited via geospatial sexual networking applications, online forums (Craigslist, etc.), and in-person (LGBT Center, etc.) for a study to see whether people would screen their sexual partners using a smartphone-based HIV/syphilis test. To assess use of the INSTI Multiplex among individuals experienced with HIV self- and partner testing, up to 20 participants were also to be recruited from the iSUM Study1 a prior rapid HIV self- and partner testing study that used a rapid oral fluid test. Inclusion criteria included being MSM or TGW, 18 years of age or older, HIV-uninfected, non-monogamous, reporting at least three occasions of condomless anal intercourse over the past three months, and rarely or never using condoms during anal intercourse. Potential participants who did not own a smartphone were excluded. Sixty-nine participants came to our research offices to complete an initial screening visit. Individuals who tested HIV negative, confirmed criteria on sexual risk behavior, and stated they felt able to deal with any possible violent situations arising from proposing INSTI use or testing a partner were invited to enroll. A total of 50 participants were enrolled in the study. Two participants were lost to follow-up resulting in an analytical sample of 48 participants.

Procedures

Participants responded to a brief pre-screening telephone survey; those who qualified were invited to an in-person screening visit. During the screening visit, participants underwent informed consent and a questionnaire using a computer assisted self-interview (CASI). Then they self-tested using the INSTI Multiplex while guided by the SMARTtest app. Those who were eligible based on the questionnaire and test results were invited to return for an enrollment visit within one week. At the enrollment visit, participants completed a second informed consent for the three-month study, were given ten INSTI Multiplex test kits to take home including all necessary materials for test use (e.g., band-aids, alcohol swabs, etc.), and had the SMARTtest app installed on their phones for personal use. The app and the INSTI kits both included images to instruct participant on how to read the test results in case the app scanning component failed. After three months, participants returned to complete a follow-up CASI, were re-tested for HIV and syphilis, and underwent a qualitative in-depth interview (IDI). Participants were compensated $50 for the baseline visit and $70 for the three-month follow up visit.

Assessments

Participant completed a comprehensive CASI assessment which included sections on demographics, sexual behavior, HIV and STI knowledge, HIV and STI testing history, likelihood of using the INSTI Multiplex to self- and partner test, and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use. For the follow-up assessment we added questionnaires on the use of the INSTI Multiplex, helpfulness of SMARTtest app components (12 items, rated on a 7-point scale from 1=Not helpful at all to 7=Extremely helpful) and an adapted version of the Mobile Application Rating Scale [25] (MARS) that had participants rate 24 different aspects of the SMARTtest app functionality on a 5-point scale ranging from 1=Completely Disagree to 5=Completely Agree).

During the IDIs, participants detailed their experiences using the INSTI Multiplex to test themselves and their sexual partners, their use of the SMARTtest app, and to provide feedback on the content and features of the app.

Data Analysis

For this paper, descriptive statistics were calculated for demographics from the baseline CASI and use of the INSTI Multiplex, likelihood of using the INSTI Multiplex in the future, helpfulness of SMARTtest app components, and the adapted MARS from the three-month follow-up CASI. IDIs were audio-recorded, transcribed, and reviewed for accuracy. Development of the codebook began with the general topic areas of the IDI guide and was further refined through repeated reading of transcripts by a team of three researchers. Codes were defined with inclusion and exclusion criteria including examples. Then, two staff members independently coded the interviews; 20% of the interviews were double-coded and discrepancies between coders were discussed until consensus was reached. For this paper, coding reports on “Overall Experience using the INSTI,” “Experiences using a blood-based test,” “Dealing with reactive results,” “Overall experiences using the SMARTtest app,” and “Challenges in using the app,” were extracted. Thematic analysis was conducted to identify salient themes in the coding reports. Themes were then summarized and relevant quotes extracted to demonstrate the themes identified. Quoted text has been edited for clarity and readability without compromising the integrity of the content.

RESULTS

Demographics

Forty-eight participants completed the three-month follow up assessment. As shown in Table 1, participants were diverse in age (M = 41.69; SD = 10.91, range=22-61), 85% were people of color, a majority reported at least some college education, and almost all identified as gay or bisexual. Eleven (23.9%) identified as a transgender woman. Approximately one-third took part in our prior self- and partner-testing study. Overall, 21 (44%) had used the OraQuick to self-test while 14 (29%) had used it to test a partner. Thirteen (27%) reported ever using PrEP, 7 (15%) during study participation. As seen in Table 2, over 40% of participants reported a prior history of syphilis, chlamydia, or gonorrhea infection.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n = 48)

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.69 (10.9) |

| Annual income (US dollars) | $34,681.1 ($44,487.7) |

| N (%) | |

| Education | |

| Less than High School Grad | 3 (6%) |

| GED/High School Grad | 14 (29%) |

| Some College | 14 (29%) |

| College Degree | 12 (27%) |

| Graduate Degree | 5 (8%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 17 (36%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black/African-American | 28 (58%) |

| White | 9 (19%) |

| Other/More than one | 11 (23%) |

| Gender Identity | |

| Man | 37 (77%) |

| Woman/Transgender | 11 (23%) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Gay/Homosexual | 34 (71%) |

| Bisexual | 11 (23%) |

| Straight/Heterosexual | 3 (6%) |

| Employment/Student Status | |

| Employed | 25 (52%) |

| Student | 3 (6.3%) |

| HIV Testing History | |

| Frequency of HIV testing | |

| Less than once a year | 4 (8%) |

| Once a year | 11 (23%) |

| Twice a year | 9 (19%) |

| Three times a year | 10 (21%) |

| Four or more times a year | 14 (29%) |

| # of times tested in past 2 years (Median, range) | 5 (0-20) |

| History of self- and partner-testing with OraQuick | |

| Participated in previous self- and partner-testing study | 17 (35%) |

| Ever used OraQuick for self-testing | 21 (44%) |

| Number of times used OraQuick for self-testing (Median, range) | 4 (1-50) |

| Ever used OraQuick for partner-testing | 14 (29%) |

| Number of times used OraQuick for partner testing (Median, range) | 3.5 (1-50) |

| PrEP Use | |

| Ever used PrEP | 13 (27%) |

| Taking PrEP during study | 7 (15%) |

Table 2.

History of Syphilis, Chlamydia, and Gonorrhea Testing. (N=48)

| Syphilis | Chlamydia | Gonorrhea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever tested | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| No | 22 (46%) | 21 (44%) | 20 (42%) |

| Recently tested (in the past year) | 15 (31%) | 17 (35%) | 15 (31%) |

| Last tested >1 year ago | 11 (23%) | 10 (21%) | 13 (27%) |

| Ever tested positive | |||

| No | 15 (58%) | 14 (52%) | 14 (50%) |

| Yes, in the past year | 1 (4%) | 4 (15%) | 4 (14%) |

| Yes, but not in the past year | 10 (39%) | 9 (33%) | 10 (36%) |

Use of the INSTI Multiplex

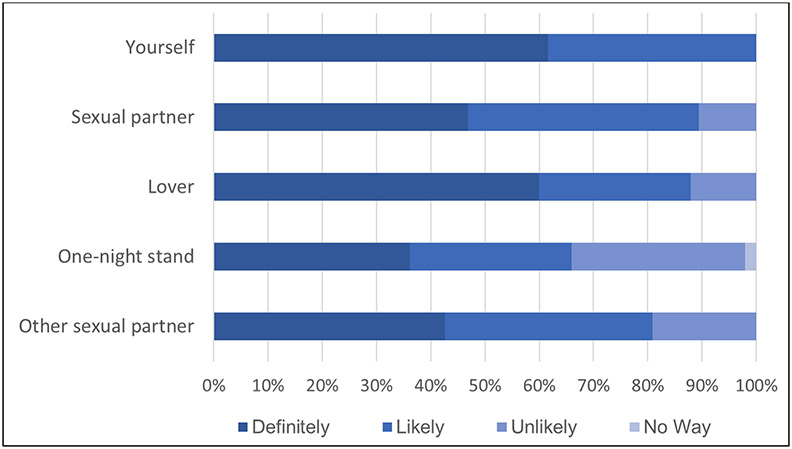

Thirty-seven (77%) participants used the INSTI to self-test and most did so multiple times (M=3.7 times; SD=3.9) during the three-month study period. Few participants reported difficulty performing the test (10%) or interpreting results (8%). All participants stated they would use the INSTI for self-testing (Figure 1; note one participant did not answer the question).

Fig 1.

Likelihood of self- and partner testing using the INSTI Multiplex if cost were not an issue.

INSTI for self-testing

Overall, participants had a favorable experience with the INSTI Multiplex. Participants who had not previously used a home test found it provided more convenience, and privacy than a clinic environment. A few expressed preferring the INSTI because of how quickly it delivered results compared to testing in-clinic, which they reported allowed them to test more frequently than usual. Many liked its ease of use and the dual HIV/syphilis test, which heightened their risk perception for syphilis.

I think it would be very convenient to have. I definitely would use it more often. You don’t have to go out to a clinic or to a doctor or the hassle of having to wait somewhere or whatever. (MSM, 27 years old, Black)

I feel like, one, the privacy definitely plays into it. You’re not in a waiting room where you’re seeing other people find out their results. People are seeing you find out your results. It’s not hard to put two and two together if somebody comes out the room crying, versus if somebody comes out the room happy. So the privacy aspect plays a part in it. (TGW, 27 years old, Black)

I found it to be very easy. It’s much more user-friendly than the oral test, honestly. I guess because it is the blood, it’s quick. It was less steps. So, I didn’t find it [a blood-based test] to be a deterrent in anything. It was boom, boom, done. (MSM, 53 years old, Black)

I like the fact that it tests for both. I’ve had an STI before, but I’ve never had syphilis. And so, if I had it before, I know there’s potential for this test to pick that up, but like any test I would just get a second opinion or do further testing. To me it’s a win-win because it allows two tests instead of one. I liked that cause it’s convenient. (MSM, 37 years old, Black)

A great majority of participants did not have a problem with a blood-based test, but a few did express their dislike for a fingerprick test and the lancet provided, with most reported difficulties centering around obtaining a blood sample or stopping the bleeding after blood collection. Only one participant disliked the test, finding the testing procedures long and cumbersome to manage.

No I was really -- like, I don’t like needles, so when I had to stick myself, I had to get it together. That little pinch, I had to, like, get it together. Then I did it. You know, I put it in one, and then, you know, I mixed it and I did it. (MSM, 55 years old, Black)

So overall it went pretty well. The only thing I would change about it is that sometimes it felt a bit drawn out. There’s all these vials, and then you have to do this and then you have to -- well, it’s not that long but it’s just -- I’m comparing it to the OraQuick where you just do the swab and it’s like in and out. And I guess it’s because it’s also testing for syphilis --if there were some way to condense the process that would make it better. It can just feel a bit tedious, almost clinical in a way because it’s the gloves and there’s just everything. (MSM, 22 years old, Black)

INSTI for partner testing

Twenty-six participants (54%) used the INSTI Multiplex to test a partner (M=1.6 times; SD=2.2). Thirty-three participants asked 162 partners to test, and 64 (40%) agreed and completed the test. Participants reported a high likelihood of using the INSTI Multiplex for partner-testing (89). However, this varied by partner type (see Figure 1). Participants had both failures and successes in testing different partner types. For example, some participants approached ongoing partners to test because they expected it to be easier, but many of those partners responded defensively because they thought the participant already trusted them to be HIV/STI free. For others, the familiarity of an ongoing sexual relation did facilitate testing a partner. Similar findings were also evident when participants approached new partners for testing. The great majority of participants performed the test on their partners, rather than letting the partners test themselves. Lastly, among the seven individuals who were using PrEP during the study, very few reported using the test with sexual partners.

It was fine. I mean, once I got used to the idea and got my partners used to the idea. I mean, I can’t say it was difficult, because the people I used it with were people I’m very familiar with, so they understood the situation, and that I was participating in a study, so I didn’t have any problem. (MSM, 54 years old, White)

So I was like “Hey, by the way, I’m in this cool research study. Would you mind -- can I prick your finger and just like for my own ease, because you did nut inside of me, to confirm that you’re HIV and syphilis negative?”, and he was like “Yeah, sure”. He actually didn’t flinch about it at all. So I pricked his finger. The app did not read the results in my room the first couple of times because it was so dark, so took it into the bathroom and turned the light on. It ended up coming out negative. He was like “Oh, that’s cool…screenshot and send it to me”, so I did that. (MSM, 31 years old, White)

I asked him can I have some of his blood. (laughter) And we both laughed, because he was like oh, you’re a vampire, so he let me take his blood and I put it into the little hole where the blood goes. Again, I put the solutions in afterward, which lets you know right away whether the person has anything. I’m not [surprised] that he was negative, but I was amazed how fast the test worked. (MSM, 31 years old, Black)

And then I let them do it on their own and then helped them if I needed to do anything -- for the most part it was easy for them to do. They prick themselves and everything. I think the only part I had to probably help them with was helping them squeeze their finger to get droplets of the blood. But it’s pretty simple. (MSM, 27 years old, Black)

Participants did report that partners frequently refused to test. Some refusals were related to testing in general, but refusals to test due to the blood-based nature of the test were also frequent, with some partners refusing to test after they realized the test involved a fingerprick.

Well, my partners didn’t really want to use the test, mainly I felt like they were like offended when I asked them to use them. They also didn’t really like the aspect of puncturing themselves with the needle, so unfortunately, I didn’t get to use the test. You know, I wish I could have, but nobody wanted to use that. (MSM, 34 years old, Hispanic/Latino)

Oh it went pretty well. I had done the previous study where we did the mouth swab, and that went very easily. But getting people to allow me to prick them was the main issue. At first they were like -- oh, yeah, that sounds great. And then I would break out the test kit and I’d be like so I’m going to have to prick your finger a little bit. And they were like oh, I’m going to bleed? And they were like no, I’m not doing that at all. And like I would try -- I’d be like, it’s just a little bit, and it’s just a little drop and, it’s only going to hurt for a few seconds. But they just wouldn’t go for it at all. (MSM, 37 years old, White)

Dealing with reactive results.

No study participants received reactive HIV results during their study participation. Based on CASI responses, 15 individuals that participants tested received reactive HIV results. This includes individuals who were known to be HIV positive that some participants tested to “test” the accuracy of the INSTI and a small group of young HIV-positive MSM that a TGW participant tested because she wanted them to experience the testing process and to also be tested for syphilis. One participant tested two partners who received unexpected reactive HIV test results.

He was really nervous, he was kind of like scared, because he was a DL [down low]. I got down and I actually spoke to him after we found out the results, to let him know, you know, you’re not the only one this can happen to. You know, you can go ahead and get help, you don’t let it control you, you control it. This is basically what I told him, and I did wind up sleeping with him, but I just was very cautious, I did wear protection with him, yes. (MSM, 46 years old, Black)

But he just like, really broke down and stuff, and I think that was his worst fear, this is what I got from him. From the outcome of his bursting out and, you know, talking to me, and I sat down and I told him, I said I’m not a counselor, but I can talk to you, I am a little educated about it. I told him, I said you don’t have to die from this, you can live with this for years, 30 years and better. As long as you’re taking your meds, go see a doctor, make sure that you’re taking care of yourself. (MSM, 46 years old, Black)

Eight study participants received reactive syphilis results at enrollment, all of which they considered to be prior syphilis infections (and would still show as a reactive result on the INSTI Multiplex). There was great variation in how participants dealt with partner-testing given this situation: Two reported that they explained their reactive result to their partners as a prior infection; two tested partners but it was unclear whether their own reactive syphilis results were discussed; one participant showed partners only the HIV results he had saved on his phone from prior tests, hiding the syphilis result; one participant was quite distressed about how potential partners would react to these results and only tested a friend without mutually self-testing; and the remaining two participants did not use any tests during the study.

So he takes the test, everything clears for him, I take the test, everything clears for me except the syphilis, so I explain to him what syphilis is, blah, blah, blah. I said do you have a condom? You can wear a condom. He’s like I don’t wear condoms, I don’t want to wear condoms, I like it natural -- you know, things like that. And he’s like a rough guy, you know. And so I say to him, well, we can have sex. He penetrated me. It was great sex. We had sex about two or three times additionally after the first…I did not want to have anal sex with him because I…became more conscious of my situation and their situation. If they’re negative for syphilis and HIV, and I’m positive for syphilis, then I’m contracting syphilis to them. And so that was an issue for me, which is why I was more inclined to do oral sex than I was to do penetrative anal sex. (MSM, 37 years old, Black)

So when I figured out the situation, I thought oh, this is going to be difficult, because when I get tested for syphilis, I always come back reactive. So when I figured out all these tests are going to just tell me I’m reactive, that’s going to create a major hurdle for using these tests with strangers. It would be a kind of hard conversation to have, like oh, you want to take this test and it involves like you exposing your blood to me, me explaining that I will test positive for syphilis but it’s a false positive, and then it’s like -- it’s kind of like a ridiculous thing to suggest. (MSM, 42 years old, Hispanic/Latino)

One of the participants who openly discussed his syphilis reactive results with partners was also the only participant to learn he had been infected with syphilis during the study (a TGW participant was also infected with syphilis, but learned of that result during her follow-up visit). He was notified by a sex partner of a recent syphilis infection and that partner recommended that the participant be tested. The participant was unsure whether he was infected by a partner he did not test or a partner whose reactive syphilis result was attributed to an earlier infection.

I think there was also folks who came back positive for syphilis -- they were like “Oh my God I have syphilis”. And I was like no, it could have been a previous infection, blah blah blah. I ended up actually contracting syphilis during the study, and that was a shitty thing because, you know, the shot is big and it hurts and that was like damn. All these test kits and the pricking of the fingers and I still ended up with it. [I called my recent partners to tell them….] and they’re like but you tested me for that, right, and I came back negative. Or I told you I previously had an infection and I was like hey, could have been you, you previously had one, it showed me you previously had one but I don’t know if that also was a current infection, right. Like that’s not showing me that. So I think more information about if somebody shows up as a previous positive for syphilis, really being clear -- a gentle reminder, right. And that could be something that could be added to the app is if this person previously tested positive for syphilis or previously had been treated, please be mindful that they could also be infected again, right. (MSM, 46 years old, White)

Although a few participants had partners receive reactive syphilis test results, almost all considered them to have been a past infection. One TGW participant who engages in sex work did have two sexual partners receive reactive syphilis results. On both occasions, the partners thanked her for the test, which alerted them that they needed treatment.

But he came up positive. He went to the clinic. When he came up positive for syphilis, he went to the clinic, and he called me right away and said, “They said I got gonorrhea.” I said, “Oh.” He said, “Can you come get checked?” I said, “OK, I’ll go get checked.” And I went and got checked, immediately, and I came out negative. I was like, “Thank you, god.” So… And, he knew the person who gave it to him. And, he told me “Babe, please go get your ass up and get checked.” So, when I got checked, I reached back to him and said, “It’s all good, I’m negative.” He’s like, “Thank god, because I didn’t want you to, like, turn on me either.” He was with me last night and we brung up the conversation last night, and he was like, “Yeah, I’m actually happy that this, everything happened the way it did, because I wouldn’t know and I would have kept -- I probably would have hurt you. And I didn’t want to hurt you.” He’s sweet, we talked about it last night. I felt good. I felt like I saved a bunch of people’s life, especially strangers. It was fun, it was exciting, and it felt really, really good. (TGW, 32 years old, Black)

Use of the SMARTtest app

As shown in Table 3, the SMARTtest app was rated highly for functionality (M=4.16 of max 5; SD=0.85) and, in Table 4, for helpfulness of its components (M=6.13 of max 7; SD=1.1). Participants gave the highest ratings for helpfulness to the step-by-step and video instructions. Seventy-eight percent would recommend the app to a friend. Most stated the app increased their comfort with testing partners for HIV/STIs, indicated it was helpful for finding follow-up confirmatory testing or HIV/STI health care services, and that the app increased knowledge of HIV and syphilis testing. Of the scanned results, the app recorded: 18 HIV/Syphilis negative results, 7 Syphilis positive results, and 12 Invalid results. Numerous participants reported they did not scan their own nor their partner’s test results with the app.

Table 3.

Functionality of the SMARTtest app among MSM and TGW participants

| Item | Mean* |

|---|---|

| 1. The SmartTest app was fun and entertaining to use. | 3.58 |

| 2. The SMARTtest app presented information about HIV/Syphilis testing in an interesting way. | 3.91 |

| 3. The SMARTtest app allowed me to customize the settings and preferences to my liking (e.g., turn on notifications, adjust sounds, etc.). | 3.60 |

| 4. The SMARTtest app contained helpful prompts to keep me engaged in the HIV/Syphilis testing process (e.g., reminders, sharing options, notifications, etc.). | 3.74 |

| 5. The content and information on the SMARTtest app were relevant for me as a Gay/Bisexual man or Transgender woman. | 3.68 |

| 6. The features of the SMARTtest app (e.g., scanning, saving, sharing test results, etc.) functioned accurately. | 4.11 |

| 7. It was easy to learn how to use the SMARTtest app. | 4.18 |

| 8. The menu labels, icons and buttons were clear and easy to understand. | 4.31 |

| 9. Moving between screens and different components (e.g., testing instructions, HIV/Syphilis resources, etc.) of the SMARTtest app was user-friendly. | 4.20 |

| 10. The menu icons, labels and buttons on each screen were appropriately sized and adequately arranged. | 4.30 |

| 11. The images and content of the SMARTtest app were clearly presented. | 4.32 |

| 12. The SMARTtest app was visually appealing. | 4.05 |

| 13. The SMARTtest app content was helpful in answering concerns about HIV/Syphilis testing. | 4.31 |

| 14. The information on the SMARTtest app was comprehensive. | 4.40 |

| 15. The visuals (e.g., images, videos, etc.) presented on the SMARTtest app were useful in performing the INSTI test. | 4.23 |

| 16. I trusted the information (e.g., HIV/STI facts, referrals, etc.) presented on the SMARTtest app. | 4.48 |

| 17. The SMARTtest app increased my awareness of the importance of testing for HIV and Syphilis. | 4.42 |

| 18. The SMARTtest app increased my knowledge and understanding of HIV and Syphilis testing. | 4.23 |

| 19. The SMARTtest app helped me feel more comfortable with the idea of testing my partners for HIV and syphilis. | 4.22 |

| 20. The SMARTtest app increased my motivation to bring up HIV/STI testing with my partners. | 4.25 |

| 21. The SMARTtest app was helpful in finding follow-up confirmatory testing or HIV/STI health care services. | 4.24 |

| 22. Using the SMARTtest app increased my comfort with testing my partners for HIV/STIs. | 4.18 |

| 23. I would recommend this app to other Gay/Bisexual men or Transgender women who might benefit from it. | 4.42 |

These means exclude participants who selected “Not applicable” or “Refuse to Answer.” The N with non-missing data ranged from 35-45. Statements were rated on a 5-point scale from 1=Completely Disagree to 5=Completely Agree

Table 4.

Helpfulness of SMARTtest components.

| SMARTtest components | Mean* |

|---|---|

| 1. Step-by-step Instructions | 6.41 |

| 2. Voiceover step-by-step instructions | 6.08 |

| 3. Video Instructions | 6.46 |

| 4. Displaying results using text (e.g., positive, negative, invalid) | 6.39 |

| 5. Deleting test results | 6.18 |

| 6. Saving test results | 6.13 |

| 7. Sharing test results | 6.11 |

| 8. User login | 5.74 |

| 9. Option to utilize a guest account | 5.85 |

| 10. HIV/Syphilis Information (e.g., resource links) | 6.31 |

| 11. Locating clinics using zip codes | 5.74 |

| 12. Emergency hotline | 6.03 |

These means exclude participants who selected “Not applicable” or “Refuse to answer.” The N with non-missing data ranged from 31-41. Components were rated on a 7-point scale from 1=Not helpful at all to 7=Extremely helpful

Overall Impression of SMARTtest app

The great majority of participants viewed the app as “cool”, easy to use, self-explanatory, and/or simple to navigate. Some participants mentioned that the video instructions were especially helpful in learning/remembering how to use the test. Fewer participants also mentioned liking the inclusion of a list of sexual health clinics, the hotline number, and information about HIV/syphilis and the test (window periods, etc.). A few participants also expressed liking specific app functionality such as receiving results in words (“positive” or “negative”) and the ability to share results with others.

Doing the test on [the app] was not a problem. It was easy. It was actually helpful to the conversation with the individuals… [The scanning process] was cool, it was fun, easy. And the app also was a big help. Because they saw it’s on the phone, this is real, this is legit, you know. (TGW, 32 years old, Black)

And then I like the ability of -- well for my own results -- to be able to show them to someone when they ask. Because people actually ask to see your results. There would be times when I would go get tested in a facility and I wouldn’t necessarily walk out with a piece of paper or anything like that. And it’s like well I’m sorry, I don’t have papers. And then it’s just like well okay then, you won’t [hook up]. (MSM, 37 years old, White)

Yeah, list of clinics and providers. That was easy and like the resources -- I was learning new things like about other stuff. I learned that everywhere is somewhere to get tested, (laughter), for one. And like the resources is like the window period, the info about the HIV and syphilis, the nearby clinics. Being able to call a hotline was very helpful. The result interpretation key, if somebody didn’t understand and I didn’t feel like explaining all I had to do was be like, oh, well, this is what happens. This is what it means. (TGW, 30 years old, Hispanic/Latina)

Nonetheless, many participants did not use the app for testing, feeling confident in their ability to conduct and read the test results correctly after self-testing with the INSTI Multiplex during the baseline visit. Yet, most participants also viewed the app as very beneficial in case it was needed.

And I didn’t always use the app, knowing what I knew about the dot placement. So I didn’t always scan them into the app. (MSM, 31 years old, White)

I mean, I didn’t use it, but the app is helpful. It’s helpful for people that are confused about the situation. If they’re confused, then they should by all means go use the app, but the app, even if you’re not sure, you can take the picture and then the app will give you the results itself. So, the app is definitely beneficial. (MSM, 58 years old, Black)

Challenges in using the SMARTtest app

The most frequently cited problem was trouble accessing/logging into app due to technical/ phone difficulties (e.g., switching phones, trouble with the Google play store, poor Wi-Fi, app wouldn’t open on their phone) or due to forgetting their password. Some participants also mentioned that they had trouble with the scanning feature, whether due to bad lighting, issues with their phone’s camera, or unspecified reasons; this resulted in invalid results, which was not ideal for participants.

Oh, God. I had a hard time signing on for a while. (MSM, 51 years old, Hispanic/Latino)

So the last time I used it, the app updated itself on my phone, and it changed --it’s a whole new password, and I couldn’t access it. Because I had a different password than I normally use. (MSM, 39 years old, Black)

But I did have one issue with the reading, and I think it was the phone. And so that’s when I started to try to do it on my iPhone because it has a better camera. That was the only issue. Other than that, I had no problems. (MSM, 37 years old, Black)

One transgender participant who engages in sex work was frustrated about not being able to save partner results and notes, which she could have used to avoid partners who received reactive results. Another was frustrated by having to view the instructions in order to reach the scanning feature, since they felt comfortable performing the test without the need for instructional guidance and having to proceed through the test instruction to reach the scanning component prolonged the testing process.

Frustrating -- you know when you open up the app and it says, “Who are you testing, you or your partner?”, and then it says “You cannot save partner.” That is so useless. If you’re going to test partner, you want that to be saved. So I always have to press test me. I saved them but I couldn’t put a note to them, man. I wanted to put a note, put the time, the date, what street it was on. You know what I’m saying? So I could be careful if God forbid a dick come out positive -- that shit was recorded. (TGW, 40 years old, Hispanic/Latino)

The experience using the app, it was annoying. I kept having to go through all of that stuff to take the picture [scan results]. Stuff that I had already known. Yeah, that should only come up once or if anybody needs it. Because especially when you’re moving fast. You’re trying to get this guy out of here and you’ve got to keep on doing this. It was time consuming. (TGW, 30 years old, Black)

Lastly, in terms of privacy, a few participants reported they felt a bit uneasy using the app with partners as they were concerned partners would think they were capturing test results and linking it to them. Two of these participants reported such experiences with partners. Similarly, a few felt uncomfortable having their own test results in the app, out of concern about breaches to their privacy. Only one participant fully disapproved of the app, finding that the information in the app could be accessed through other means and he did not want another app taking up space on his phone.

I didn’t use the app. I didn’t want to make anyone too uncomfortable, because they already said that they wanted to keep it confidential. (MSM, 46 years old, Black)

It’s like why am I going to upload my business to who knows where. No one trusts pharmaceutical companies, even though, you know, I could explain to them that it’s a study and not for profit, blah blah blah. And there’s another thing is that my phone -- I keep on getting a new phone and it keeps having new memory, but you know, every day there’s 15 apps that want to be updated -- I’m always running out of space. And the idea of like having another gratuitous app on my phone is also a hard-sell I feel like… and the whole stuff about HIV -- I’ve been like fed that information since grade school, so it’s just like yeah I don’t need this on my phone (MSM, 42 years old, Hispanic/Latino)

DISCUSSION

Findings from this study show high acceptability and likelihood of use of the INSTI Multiplex for self- and for partner-testing among participants. In general, participants found the test to be easy to use and liked its quick results as well as the combined HIV/syphilis test. They also expressed high acceptability of the SMARTtest app, with participants finding it a useful support during testing, particularly the dual video and step-by-step instructions, the scanning feature to translate test results into words, and the ability to save results to show to others. Nevertheless, actual use of the products did not match the acceptability expressed by participants. Use of the INSTI Multiplex was hampered by its reliance on a blood sample, resulting in many partners refusing to test. Even some participants reported a dislike for the fingerprick aspect of the test, although these were few. Less frequent partner-testing contributed to infrequent use of the SMARTtest app, as did the ease of use of the INSTI Multiplex itself. Participant’s knowledge of how to read test results often led them to eschew the app, as the app required the participant to view the instructions before being allowed to scan results, thereby slowing the testing process. Furthermore, even though the app was designed to maximize partner privacy by not allowing their results to be saved on participants’ phones and not capturing any information about them, just the presence of a smartphone during the testing process raised concerns about privacy for some individuals. Nonetheless, almost all participants found the app beneficial in case one forgot how to administer the test or needed to facilitate linkage-to-care in case of positive results.

The acceptability of the INSTI Multiplex for self-testing is clear, given the high frequency of self-testing during the study (even after testing at the baseline visit) and high reported likelihood of using the INSTI Multiplex for self-testing in the future. Testing appeared driven mostly by concerns about HIV infection, even though a few participants spoke of concerns about syphilis infection. Thus, a combined HIV/syphilis test such as the INSTI Multiplex may increase rates of testing for syphilis, especially among those not receiving regular testing through their enrollment in PrEP. However, reactive syphilis results were more complicated to understand. Among individuals without a history of syphilis infection, the reactive results provided a clear prompt to seek care. However, those with a prior infection interpreted tests results as a remnant of that previously treated infection, potentially overlooking a recent syphilis infection that needed to be treated. This is an important limitation. To maximize the potential of STI self-testing to reduce incidence of infection, future tests will need to help users accurately distinguish between a current and a past infection.

As in prior studies, participants and partners who received reactive results dealt with the news in an appropriate manner. Partners who received reactive results received support from participants. In the first study of self- and partner testing, Carballo Dieguez et al [26] reported that no sexual contact occurred after any partners tested HIV positive. More recently, however, Balan et al [27] reported that it was not uncommon for study participants to engage in sex with partners who tested positive, especially if the partner had been aware of the infection, was under treatment, and had an undetectable viral load, suggesting that norms about sex with HIV positive individuals might be changing among MSM. This study had similar findings in this regard. Although only a few partners tested HIV positive, participants engaged in sex with them afterwards and used protection. This study broadens such findings to syphilis infection. However, contrary to prior HIV self-testing studies, in which those who were HIV positive were exited from the study, in this study, participants with reactive syphilis results (interpreted, whether accurately or not, to be from prior infections) had to negotiate testing with partners. This was challenging to many participants, as the reactive result would most likely need to be addressed if there was mutual testing with a partner—which is typical in order to entice a partner to test. We found that few participants openly discussed testing with potential partners. In the absence of a test results that would indicate an active versus past infection, this may hinder mutual STI testing with partners. Nonetheless, a few participants openly discussed the meaning of their reactive syphilis result with partners, including one participant who worried he might still be infectious. Interestingly, this did not dissuade some of his partners from engaging in high-risk sexual activities, even eschewing the use of condoms for sex. This is consistent with reports that there is low information and concern about STI infection among MSM [28].

Findings on the use of the SMARTtest app offer important lessons on the need to develop apps that are flexible to the needs of users. Due to human subjects research concerns, we designed the app to ensure that participants would have to review the instructions for use every time they used the test. To offer flexibility we did add an option to skip the video component, but users would have to swipe through the step-by-step instructions. This slowed the testing process, impinging on one of the INSTI Multiplex’s strengths—it’s almost instantaneous results-- and led to participants not using the app. Test use without the app was also likely facilitated through their experience self-testing during the baseline study visit. A first-time user of the INSTI Multiplex or someone who was not using the test as frequently as our participants might engage differently with the app. Providing the option of going straight to the scanning feature after testing may increase the use of the app among users. Maximizing flexibility in the app so that users can tailor it to their specific needs will be essential to the adoption of the app for self-testing.

Findings from this study need to be considered within limitations. First, this study focused on self- and partner-testing, and as such, the experiences of individuals who would use the INSTI Multiplex and the SMARTtest app solely for self-testing would probably differ from the experiences of the current study’s participants. Second, the study specifically recruited MSM and TGW who regularly engaged in high-risk sexual behavior and their experiences may not generalize to the broader MSM and TGW community or to other populations at risk for HIV and STIs. Third, actual use of app and test kits among individuals in the absence of free INSTI kits would likely vary from these findings. Lastly, the data was gathered through self-report, which is subject to distortions due to social desirability.

Funding:

This research was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health: R01-HD088156 (PI: I. Balán) and P30-MH43520 (PI: R. Remien). Additionally, Dr. Kutner’s work was supported by K23MH124569 (PI: B. Kutner, PhD, MPH) and T32MH019139 (PI: T. Sandfort, PhD). Dr. Rael is supported by K01MH115785 (PI: C. Rael). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical Approval: The study presented received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: All participants in the study underwent an informed consent procedure prior to participating.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carballo-Diéguez A, Giguere R, Balán IC, Brown W, Dolezal C, Leu CS, Rios JL, Sheinfil AZ, Frasca T, Rael CT, Lentz C. Use of rapid HIV self-test to screen potential sexual partners: results of the ISUM study. AIDS Behav. 2019;18:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carballo-Diéguez A, Frasca T, Balan I, Ibitoye M, Dolezal C. Use of a rapid HIV home test prevents HIV exposure in a high risk sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1753–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rael CT, Giguere R, Lopez-Rios J, Lentz C, Balán IC, Sheinfil A, Dolezal C, Brown W, Frasca T, Torres CC, Crespo R. Transgender women’s experiences using a home HIV-testing kit for partner-testing. AIDS Behav. 2020;19:1–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giguere R, Lopez-Rios J, Frasca T, Lentz C, Balán IC, Dolezal C, Rael CT, Brown W, Sheinfil AZ, Torres CC, Crespo R. Use of HIV self-testing kits to screen clients among transgender female sex workers in New York and Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(2):506–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maman S, Murray KR, Napierala Mavedzenge S, Oluoch L, Sijenje F, Agot K, Thirumurthy H. A qualitative study of secondary distribution of HIV self-test kits by female sex workers in Kenya. PloS One. 2017;12(3):e0174629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thirumurthy H, Masters SH, Mavedzenge SN, Maman S, Omanga E, Agot K. Promoting male partner HIV testing and safer sexual decision making through secondary distribution of self-tests by HIV-negative female sex workers and women receiving antenatal and post-partum care in Kenya: a cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2016;1;3(6):e266–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masters SH, Agot K, Obonyo B, Napierala Mavedzenge S, Maman S, Thirumurthy H. Promoting partner testing and couples testing through secondary distribution of HIV self-tests: a randomized clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2016;8;13(11):e1002166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson CC, Kennedy C, Fonner V, Siegfried N, Figueroa C, Dalal S, Sands A, Baggaley R. Examining the effects of HIV self-testing compared to standard HIV testing services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witzel TC, Eshun-Wilson I, Jamil MS, Tilouche N, Figueroa C, Johnson CC, Reid D, Baggaley R, Siegfried N, Burns FM, Rodger AJ. Comparing the effects of HIV self-testing to standard HIV testing for key populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control. Syphilis & MSM (CDC Fact Sheet). Available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/syphilismsm-2019.pdf. Accessed on February 2, 2021.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control. Sexually transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines 2015. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/screening-recommendations.htm. Accessed on February 2, 2021.

- 12.Gaydos CA, Hsieh Y-H, Harvey L, et al. Will patients “opt in” to perform their own rapid HIV test in the emergency department? Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S74–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibitoye I, Frasca T, Giguere R, et al. Home testing past, present and future: lessons learned and implications for HIV home tests. AIDS Behav. 2013;18(5):933–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bilardi JE, Walker S, Read T, et al. Gay and bisexual men’s views on rapid self-testing for HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2093–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balán I, Frasca T, Ibitoye M, Dolezal C, Carballo-Diéguez A. Fingerprick versus oral swab: acceptability of blood-based testing increases if other STIs can be detected. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(2):501–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pai NP, Sharma J, Shivkumar S, Pillay S, Vadnais C, Joseph L, …Peeling RW (2013). Supervised and unsupervised self-testing for HIV in high-and low-risk populations: a systematic review. PLoS Med; 10(4), e1001414. PMCID: PMC3614510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krause J, Subklew-Sehume F, Kenyon C, & Colebunders R Acceptability of HIV self-testing: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13(1):735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bilardi JE, Walker S, Read T, Prestage G, Chen MY, Guy R, Bradshaw C, & Fairley CK (2013). Gay and bisexual men’s views on rapid self-testing for HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013:17(6):2093–2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figueroa C, Johnson C, Verster A, & Baggaley R (2015). Attitudes and Acceptability on HIV Self-testing Among Key Populations: A Literature Review. AIDS Behav. 2015; 19(11):1949–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pai NP, Smallwood M, Desjardins L, Goyette A, Birkas KG, Vassal AF, Joseph L, Thomas R. An unsupervised smart app–optimized HIV self-testing program in Montreal, Canada: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(11):e10258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gous N, Fischer AE, Rhagnath N, Phatsoane M, Majam M, Lalla-Edward ST. Evaluation of a mobile application to support HIV self-testing in Johannesburg, South Africa. S Afr J HIV Med. 2020;21(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssen R, Engel N, Esmail A, Oelofse S, Krumeich A, Dheda K, Pai NP. Alone but supported: A qualitative study of an HIV self-testing app in an observational cohort study in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(2):467–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wray TB, Chan PA, Simpanen E, Operario D. A pilot, randomized controlled trial of HIV self-testing and real-time post-test counseling/referral on screening and preventative care among men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and ST. 2018;1;32(9):360–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balán IC, Lopez-Rios J, Nayak S, Lentz C, Arumugam S, Kutner B, Dolezal C, Macar OU, Pabari T, Ying AW, Okrah M. SMARTtest: a smartphone app to facilitate HIV and syphilis self-and partner-testing, interpretation of results, and linkage to care. AIDS Behavior. 2020;24(5):1560–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, Wilson H. Development and validation of the user version of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (uMARS). J Med Internet Res. 2016;4(2):e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carballo-Diéguez A, Frasca T, Balan I, Ibitoye M, Dolezal C. Use of a rapid HIV home test prevents HIV exposure in a high risk sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1753–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balán IC, Lopez-Rios J, Giguere R, Lentz C, Dolezal C, Torres CC, Brown W, Crespo R, Sheinfil A, Rael CT, Febo I. Then we looked at his results: Men who have sex with men from New York City and Puerto Rico report their sexual partner’s reactions to receiving reactive HIV self-test results. AIDS Behav. 2020;20:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balán IC, Lopez-Rios J, Dolezal C, Rael CT, Lentz C. Low STI Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Concern about Infection among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women at High Risk of Infection. Sex Health. 2019;16(6):580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]