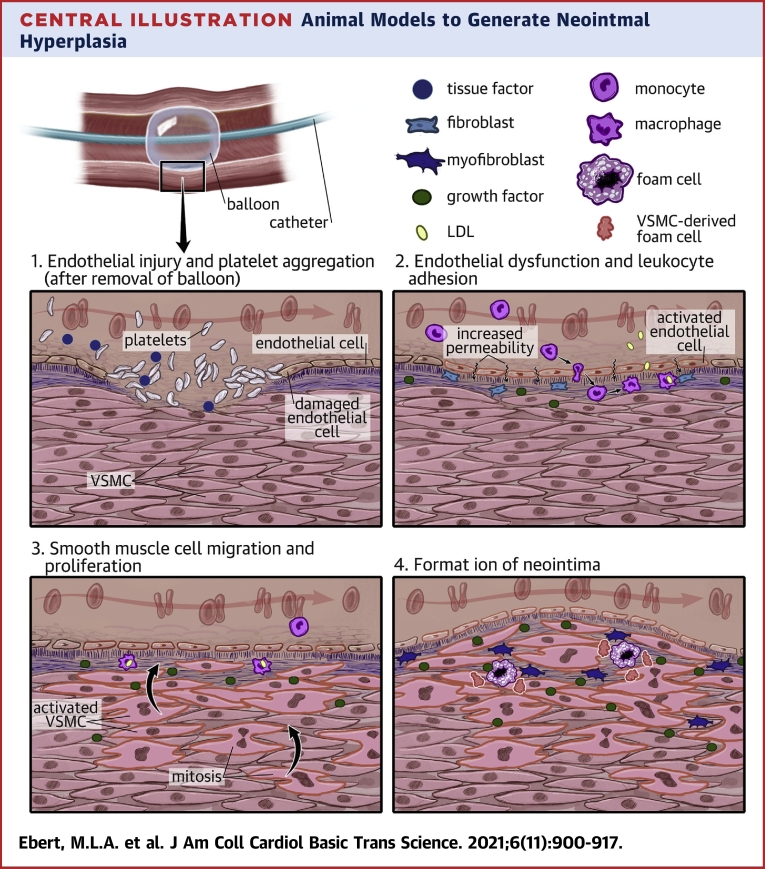

Central Illustration

Key Words: angioplasty, animal model, neointimal hyperplasia, restenosis

Abbreviations and Acronyms: Apo, apolipoprotein; CETP, cholesteryl ester transferase protein; ECM, extracellular matrix; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LDLr, LDL receptor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TGF, transforming growth factor; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell

Highlights

-

•

Neointimal hyperplasia is the major factor contributing to restenosis after angioplasty procedures.

-

•

Multiple animal models exist to study basic and translational aspects of restenosis formation.

-

•

Animal models differ substantially, and species-specific differences have major impact on the pathophysiology of the model.

-

•

Genetic, dietary, and mechanical interventions determine the translational potential of the animal model used and have to be considered when choosing the model.

Summary

The process of restenosis is based on the interplay of various mechanical and biological processes triggered by angioplasty-induced vascular trauma. Early arterial recoil, negative vascular remodeling, and neointimal formation therefore limit the long-term patency of interventional recanalization procedures. The most serious of these processes is neointimal hyperplasia, which can be traced back to 4 main mechanisms: endothelial damage and activation; monocyte accumulation in the subintimal space; fibroblast migration; and the transformation of vascular smooth muscle cells. A wide variety of animal models exists to investigate the underlying pathophysiology. Although mouse models, with their ease of genetic manipulation, enable cell- and molecular-focused fundamental research, and rats provide the opportunity to use stent and balloon models with high throughput, both rodents lack a lipid metabolism comparable to humans. Rabbits instead build a bridge to close the gap between basic and clinical research due to their human-like lipid metabolism, as well as their size being accessible for clinical angioplasty procedures. Every different combination of animal, dietary, and injury model has various advantages and disadvantages, and the decision for a proper model requires awareness of species-specific biological properties reaching from vessel morphology to distinct cellular and molecular features.

Cardiovascular diseases are currently the leading cause of death and will continue to be so in the near future (1).

The most frequent pathomechanism of cardiovascular disease is atherosclerosis, which is considered a chronic and progressive inflammatory disease of multifactorial causes, with long-term loss of patency, which primarily affects the coronary vessels, carotids, and peripheral vasculature. Percutaneous transluminal intervention, which enjoys a high success rate accompanied by low periprocedural complications, has been established for the symptomatic treatment of lumen-narrowing atherosclerosis. Despite good technical success, a relapse rate of up to 20% within the first 12 months remains, differing among vascular territories (2). Although there are various therapeutic approaches, such as delivering antineoplastic agents to the vessel wall during angioplasty via drug-eluting balloons and/or stents, lasting success is limited by the process of neointimal hyperplasia, which is the leading cause of midterm loss of patency. The formation of the neointima shows several parallels to the formation of de novo atherosclerosis. Vascular trauma triggers an inflammatory reaction with increased recruitment of immune cells, especially monocytes and macrophages, which quickly accumulate and differentiate into foamy macrophages. Oxidative stress and an increased release of cytokines and chemokines lead to proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) from the media into the intima. There, various growth factors further stimulate the formation of a neointima (3).

Restenosis can occur after stent or balloon angioplasty, as well as after other revascularization procedures associated with vascular injury. Although at reduced frequencies, restenosis has been observed following the use of drug-eluting technologies. Differences are primarily observed in frequency and timing of restenosis development (2). To understand the underlying pathomechanisms and to develop new treatment approaches, animal models have become an increasingly important tool. Basic pathophysiology and novel therapy approaches can be studied in this way. Models of neointimal hyperplasia are based essentially on 3 different approaches: 1) surgical interventions (eg, carotid artery ligation, guide-wire injury); 2) metabolic triggers (eg, cholesterol-rich feeding, provoked diabetes); and 3) specially bred or genetically modified organisms (eg, Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic [WHHL] rabbits, knock-out strains). In addition, there are many different species to choose from— rodents, rabbits, dogs, pigs, ruminants, primates, and even birds can be used to fathom the mechanisms of restenosis and neointimal hyperplasia.

Because major interspecies differences exist with regard to the pathophysiology of restenosis but also to the effects of therapeutic interventions, knowledge about atherosclerosis and neointima formation in different animal models is required. This review highlights neointimal hyperplasia as the essential pathomechanism of restenosis, with a focus on species-specific characteristics of various animal models and the resulting implications for translational research.

Pathophysiology of Restenosis

The development of restenosis is based on a complex interaction of various mechanical and biological factors triggered by the revascularization procedure of diseased vasculature and the accompanying vascular trauma (Central Illustration). The mechanism by which postangioplasty restenosis develops apparently depends on whether the intervention was performed by a stent or a balloon-only angioplasty. In case of a stent-less procedure, early arterial recoil and negative vascular remodeling are important factors. In contrast, restenosis after stent insertion (in-stent restenosis) is primarily mediated by neointimal formation and neoatherosclerosis (4,5).

Central Illustration.

Animal Models to Generate Neointmal Hyperplasia

Angioplasty and other vascularization procure cause a trauma to the vessel wall leading to neointimal hyperplasia via 4 major mechanisms: (1) Endothelial injury and platelet aggregation; (2) Endothelial dysfunction and leukocyte adhesion; (3) smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation; (4) Formation of the neointima. LDL = low-density lipoprotein; VSMC = vascular smooth muscle cell.

Early arterial or elastic recoil is an effect created by the natural elasticity of the vascular wall caused by elastin fibers and connected VSMCs. The expanded vessel contracts after removing the balloon, which leads to a renewed lumen loss of up to 50% (6). The implantation of a stent cannot always completely counteract this pressure (7).

Vascular remodeling is a physiological response for adapting the vessels to changing hemodynamic conditions. As soon as an overshooting regrowth of vascular tissue occurs at the site of previous vascular trauma, this actual healing process turns into a negative. Consequently, the term neointimal hyperplasia refers to a pathological excess of negative vascular remodeling caused by an overgrowth of VSMCs and associated extracellular matrix production after intervention (8,9). During angioplasty, the endothelium is mechanically stressed and can be partially denudated or even ruptured. This denudation can also reach deeply into the underlying medial layer and cause direct damage to the VSMCs (10).

The formation of the neointima is mediated by both cellular and humoral factors. Generally, the question whether in-stent restenosis in humans is comparable to experimental models remains contentious. Numerous cell types show the potential to transform into a VSMC phenotype, and at least in some animal models, each shows the capability to partially contribute to the neointima. Thus, neointimal formation is a process that is heterogeneous between species because each animal model features distinct cellular mechanisms rather than a common cellular pathway. Furthermore, this complexity has contributed to divergent results among certain animal models and prevents any single model from revealing the complete pathogenesis of neointimal hyperplasia (11). Regarding the major cellular players, 4 cell types and associated processes deserve attention: the endothelial cells of the intima; the monocytes and/or macrophages of the blood pool infiltrating the vascular wall; the fibroblasts of the adventitia; and the smooth muscle cells of the media (12).

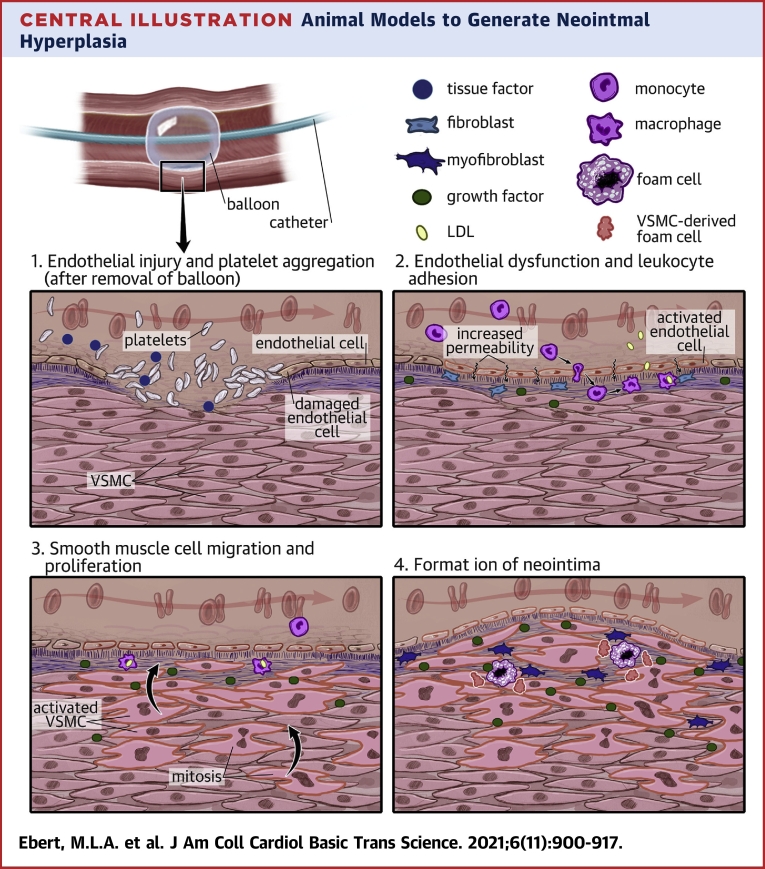

An overview of the process of neointimal hyperplasia is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Process of Neointimal Hyperplasia as the Mainstay of Restenosis

The most important aspects of neointimal hyperplasia, consisting of endothelial injury and dysfunction, increased leukocyte accumulation in the subintimal space, smooth muscle cell proliferation, and migration to the neointima with subsequent recurrent lumen narrowing of a atherosclerotic lesion. ECM= extracellular matrix.

Endothelial injury and activation

The damage to the vessel wall triggers the physiological coagulation cascade by the release of tissue factor, which leads to platelet activation and the formation of a local thrombus layer (13,14). The rupture of the endothelium and subendothelial space is accompanied by a severe endothelial dysfunction, including increased endothelial permeability and activation (15). Endothelin-1 interacts with the ETA-receptors of smooth muscle cells, encouraging them to contract immediately, thereby counteracting the endothelial ETB-receptor, which normally induces vessel relaxation by stimulating the endothelium to release nitric oxide (16). Nitric oxide and prostaglandin I2 in a normal physiological state exert vasodilative, antiproliferative, and antiadhesive effects on the endothelium. These become impaired if the physiological balance is affected by pathologic stressors (eg, diabetes and hypercholesterolemia) (3,8). Elastase, released by neutrophils, decreases the elasticity of blood cells and inactivates inhibiting factors of matrix metalloproteinases, pushing the breakdown of extracellular matrix proteins (17,18). The glycoprotein Tenascin-C promotes the proliferation of smooth muscle cells by interacting with many different growth factors and adhesion molecules, such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), as well as fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and fibronectin (18,19).

Monocyte accumulation

Various adhesion factors like selectins and vascular cell adhesion molecules are expressed by the activated endothelium, which causes leukocytes, especially monocytes, to roll and stick to the endothelium where a complex cluster of integrins and cadherins leads to a transmigration into the subintimal space (20). These monocytes differentiate into macrophages that exert an inflammatory response that releases cytokines, (eg, tumor necrosis factor-α or interleukin-1β), which intensifies the weakening of the endothelial barrier by chemotaxis of lymphocytes and additional mononuclear phagocytes (21). It could be shown that deficiency of the endogenous inhibitor interleukin-1 receptor antagonist promotes intimal hyperplasia following arterial injury (22). This further increases endothelial permeability, leading to an altered influx of low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), similar to de novo atherosclerosis, forcing the transmigrated macrophages to mature into foam cells (23). The perishing foam cells accumulate, forming a necrotic center encapsulated by a VSMC-made fibrous cap of collagen, proteoglycans, and elastin, which accelerates restenosis (24).

Fibroblast migration

The proliferation of fibroblasts is primarily stimulated by FGF and fibronectin. Because of the presence of transforming growth factor (TGF), fibroblasts differentiate into myofibroblasts that migrate into the media, causing a volume increase and promoting the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins (25). The activation of fibroblasts also increases the secretion of various growth factors, including PDGF and FGF (26). FGFs are composed of a 22-member family of proteins that mediate their biological activity by binding to 4 distinct cell surface receptor tyrosine kinases, which are referred to as FGF receptors (FGFR1-FGFR4). This leads to assembly of a ternary complex involving FGF receptor adaptor protein fibroblast growth factor receptor substrate 2 (FRS2), Grb2, and Sos, which results in activation of the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade (27). The subsequent fibroblastic migration and proliferation in combination with growth and redox factors also fosters the stimulation of VSMCs to react in a similar way (26).

VSMC transformation

PDGF-BB and the matrix glycoprotein osteopontin perform pivotal tasks during VSMC migration from the media into the intima (28,29). Their phenotype subsequently changes from the predominantly contractile to an abnormal, proliferative type (30). The TGF family, in particular TGF-β1, plays a significant role in this process by stimulating VSMC transformation via the PI3K/AKT/ID2/mTOR pathway (31). In this context, PI3K is downstream of TGF-β1 and strictly controls the levels of other proteins and genes, whereas ID2 is an essential transcriptional regulatory factor. The significant changes in this process include morphological changes in the cells, such as from spindle elongated to hypertrophic morphology, and they exhibit “hill and valley” growth. In addition, changes occur in the levels of protein and mRNA markers of the respective types, that is, an increase in protein and/or mRNA expressions of the synthetic marker protein osteopontin and a decrease in the protein and/or mRNA expressions of the contractile marker proteins α-smooth muscle actin and smooth muscle 22α (SM22α). Furthermore, VSMCs show enhanced proliferation and migration (25). Subsequently, the altered VSMCs act in a different way than when they are under physiologic conditions, because they are capable of synthesizing and secreting the extracellular matrix to a greater extent and can also convert into foam-cell−like cells (28,32).

An influence of the microbiome on the development of atherosclerosis and restenosis has also been suggested in recent studies. A comparison of aseptic and conventionally raised mice showed that the latter had more advanced neointimal formation, which was probably related to changes in the kinetics of acute inflammation and wound healing (33). Intestinal dysbiosis also appeared to contribute to the development of atherosclerosis by modulating inflammatory events caused by differences in the production of microbial metabolites (34,35).

The development of neoatherosclerosis is primarily based on postinterventional endothelial dysfunction (36). Because of insufficient endothelial regeneration, the circulating lipids increasingly accumulate in the subintimal space, accelerating the formation of new atherosclerotic plaques within the emerging neointima. This process is also shown by the early deposition of foam cells and necrotic tissue, as well as the emergence of a thin-capped fibroatheroma (37).

The detailed sequence and interplay of altered endothelial permeability, monocyte influx, VSMC proliferation, and migration, as well as increased synthesis of the extracellular matrix, are still under investigation.

Mouse Models of Neointimal Hyperplasia

Over the past decades, the mouse has become the most widely used scientific model animal. Because of its high reproduction rate, easy handling, and care, as well as its small size, it is an ideal research subject that enables the investigation of complex issues within a reasonable frame of investment. In addition, the immune system of mice is relatively comparable to that of humans, especially regarding the inflammatory response in vascular diseases. However, in contrast to humans, most mouse models do not have lumen-narrowing stenosis and plaque rupture, which is characteristic for human atherosclerosis. There are some crucial differences regarding the microscopic anatomy of the cardiovascular system of mice—the arterial intima is composed of an endothelial layer overlying the internal elastic lamina without additional connective tissue or VSMCs compared with that of humans. In addition, the vasa vasorum are missing and the tunica media is thinner. Furthermore, the morphology of atherosclerotic plaques is also distinct because a thick fibrous cap is missing (38). The absence of the vasa vasorum has been found to account for the lack of neoangiogenesis into the base of the lesions and thus to the attenuation of atherosclerosis progression. These neovessels are derived from the vasa vasorum, which consequently in humans constitute a gateway for immune cells and contribute to the chronic inflammation and development of the necrotic core (39). Therefore, there are different approaches to “humanize” the immunoinflammatory system of mice to enable more translatable models. Nonetheless, the most important advantage about the mouse as a scientific model is its ease of genetic manipulation.

Because of the different lipid metabolism and lipoproteome, which provides a high resistance against cardiovascular diseases, the use of inbred or genetically modified mice is inevitable in order to study atherosclerosis and neointimal hyperplasia. Although humans carry most of their plasma cholesterol in LDLs, mice do so in high-density lipoprotein (HDL). The reason is the murine lack of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), which passes cholesteryl esters from HDL to ApoB-containing lipoproteins such as LDL and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) in humans (40). Other important differences exist in the structure of their apolipoproteins, their homogeneous HDL, and the lack of a VLDL receptor on their macrophages. Murine liver activity also opposes atherosclerosis development: mice have high hepatic LDL-receptor activity; a high level of hepatic lipase in circulation; a high excretion of bile acid; and only low hepatic synthesis of cholesterol (41,42). This is also considered responsible for the impossibility of provoking translatable atherosclerosis in wild-type-mice only in a dietary way.

Strains and modifications

For the aforementioned reasons, different inbred strains and genetically modified mouse models exist. The most frequently used modifications are the ApoE and LDL receptor (LDLr) knockout mice. Most used strains are C57BL/6, C3H/HeJ, FVB/NJ, 129/SvJ, and BALB/C.

ApoE is a glycoprotein mainly synthesized in the liver that plays a pivotal role in the catabolism of chylomicrons and VLDLs. It mediates the cellular uptake of these substances in the liver and small intestine by acting as a ligand for the ApoE-receptor or LDLr. ApoE deficient (ApoE−/−) mice show higher plasma levels of total cholesterol and develop atherosclerosis on a normal diet, which can be significantly enhanced by feeding a western-type, high-fat diet. The lack of ApoE markedly affects the course of inflammation, which affects the translational potential. Still, a combined model of ApoE−/− mice with an artery ligation approach, as explained in the following, leads to neointimal formation, which, in certain aspects, is comparable to that of humans (43).

The LDLr, found on the membranes of almost all animal cells, mediates the endocytosis of LDLs. LDLr−/− mice, which lack this receptor, only show significantly increased levels of plasma cholesterol on a western-type diet. They develop a human-like lipid profile, whereas inflammatory responses remain unaffected (44).

Carotid artery ligation model

In this blood flow cessation model, the ligation of the common carotid artery near the distal bifurcation causes disruption of blood flow, which leads to VSMC-rich neointima formation with extensive vascular remodeling and a reduction of the vessel diameter within 2-4 weeks (45). Decreasing cellularity and increasing extracellular matrix accumulation of the evolving neointimal lesion can continuously be observed within a few weeks. The contralateral carotid artery can be used as a negative control and undergoes compensative remodeling with an extension in diameter, whereas changes in gene expression can be detected on each side 3-4 weeks after ligation (46).

Other approaches of this model apply an incomplete blood flow disruption by ligating either the external or internal or both carotid arteries, while leaving the common carotid artery untouched. This allows decreased but consistent blood flow, which is believed to reduce thrombus formation and endothelial denudation that otherwise occurs directly at the site where the ligature constricts the vessel (47,48).

The advantages of these models lie in the good surgical feasibility as well as their high reproducibility. In addition, mechanical trauma and inflammatory response are limited, whereas the endothelium remains largely intact. Thus, this setup is not ideal to study neointimal behavior in a clinically translatable way but allows investigation of the physiological backgrounds on a molecular level (46).

Cuff injury model

A less severe mechanical manipulation was established to resemble the clinical situation. The model of cuff-induced neointimal formation was invented for mice to study the role of specific endothelial mediators. In this model, a small polyethylene cuff traumatizes the vascular wall by a perivascular constriction that still injures the vessel, but in a less severe way and without endothelial denudation, while at the same time causing only stenosis of the perfused lumen without complete obstruction (49). The emerging neointima primarily consists of VSMCs, which seem to be mainly induced by the release of the PDGF family and the presence of extracellular matrix substances (50).

Other approaches were established by placing a cuff containing a conical inner lumen, which create a differing vessel diameter that induced specific shear stress, oscillation, and variations in velocity of the blood stream, which led to atherosclerosis formation in hyperlipidemic mice (51).

As an advantage, this technique is associated with reduced bleeding and thrombosis rates with lower mortality and is relatively easy to reproduce. It is also relatively economical in time and cost. The endothelium remains largely intact and its involvement in atherosclerosis and neointimal formation can be investigated on a molecular level (52).

Wire injury model

Originally carried out on the carotid artery, this endovascular dilatation and endothelial denudation model is now mainly used on the femoral and iliac arteries. The mice should be aged between 10 and 16 weeks to find a balance between technical difficulty (too small arteries) and reproducibility (increased variability in neointimal formation) (53). The artery must be exposed first, followed by an incision between 2 ligatures (the proximal to be tightened immediately to avoid blood loss, the distal to be ligated after the endothelial denudation) where the wire is inserted. The diameter of the wire can be up to 3 times the diameter of the vessel and is not moved for 1 min to ensure overstretching. The wire is then either rotated or moved back and forth, so that the endothelium is almost completely removed, and the cells of the medial layer are also partially damaged. The vessel is subsequently ligated. This procedure is more complicated if the vessel is not disconnected and blood flow is restored, for which the incision must be closed, and the muscular branch must be tied off. This affects the translational potential because an impaired blood flow also limits the transmigration of cells from the circulation into the vessel wall (54,55).

Platelet adhesion and VSMC damage can be detected directly afterward, and the start of neointima formation can be observed within 1 week. After constantly evolving, a concentric and homogenous neointimal lesion primarily consisting of VSMCs forms at 3-4 weeks and stagnates at approximately 8 weeks (54).

This model is ideal to mimic the trauma caused by balloon angioplasty while a constant blood flow can be maintained (if the vessel is not ligated). It offers a well-established option to study postangioplasty restenosis, such as the reaction of the VSMCs to the denudation, with a low degree of inflammation and thrombosis.

The problem regarding this method is primarily the technical feasibility. To produce valid results, the intervention should be performed by the same operator in all animals of a single trial to avoid major variations (54).

Vein graft model

This research tool was developed to investigate the pathophysiological response that occurs during neointimal hyperplasia and restenosis in bypass grafts. The jugular vein or 1 of the vena cava of a donor animal is transplanted into the trial animal and anastomosed with the carotid or femoral artery—end to end (with or without an inversion of the anastomosed vessel or use of a cuff), end to side, or with a venous patch for a larger vascular defect (56).

In this case, the formation of a neointima is not necessarily negative. Because of the new requirements for the graft, the thinner vein wall has to strengthen to withstand the altered pressure and flow. However, if this remodeling process exceeds a certain degree, accompanied by the development of atherosclerotic lesions, flow-limiting restenosis is observed.

This model basically resembles mechanical characteristics and complications of human vein grafts. Genetically based questions can be investigated specifically. For example, immunogenic responses can be avoided by using transplants within the same syngeneic strains, genetically modified grafts can be used in wild-type mice to define the effects of specific genetic changes, and particular cell types can be tracked and studied (57, 58, 59, 60).

In contrast, the potential for transferability to humans is at least questionable because clinical interventions cannot be reproduced equally in mice for anatomical reasons. In addition, validity fluctuates because technical application and reproducibility is limited. Plus, the reaction of transplanted veins differs because of the large difference in heart rate and blood flow between mice and humans (61).

Other mouse models

The photochemical injury model works with a chemical reactant (eg, rose bengal red) that responds to the vessel wall through the interference with light. This leads to severe endothelial damage, followed by thrombus formation, VSMC migration, increased extracellular matrix synthesis, and vascular wall thickening. This model enables endothelial denudation without mechanical influences and is easy to reproduce (62,63).

Models of in-stent restenosis have recently been developed using microvascular stents and balloons to injure the aorta in mice to study the situation and underlying mechanisms within more different phenotypes of metabolic backgrounds or diseases. However, the clinical relevance of this model is limited because the tiny stents have to be specially produced, which has been associated with major changes in their mechanical properties (64,65).

The electric injury model is carried out using an electric coagulator, which destroys nearly all cells across the vascular wall. This approach, although rather fierce, can be used to research the genetic and molecular mechanisms of neointimal formation and VSMC migration under severe thrombotic, inflammatory, and remodeling conditions (66).

Models of different chemical injury, air drying, or allotransplantation have also been developed, but are not widely used because of their specific approaches and lack of physiological and translational relevance (67).

In models of arteriovenous fistula, an anastomosis is created between the aorta and vena cava or between the carotid artery and jugular vein to resemble human arteriovenous fistula. This model is well established (also in different species and different target vessels) to study restenosis and neointimal formation, especially in terms of venous remodeling. It is distinguished by rapid lesion development and can be performed as required with or without a renal disease background (68,69).

Rat Models of Neointimal Hyperplasia

The first unintentional inbred strains of the rat can be dated back to the 19th century. Their genome has been fully deciphered, and their genetic manipulability has been increased but is still not on the same level as in mice. Rats offer a good compromise because they are large enough for balloon or stent models and simultaneously allow for high-throughput research by having a high reproductive rate. They also require little effort because of their use of small space and expense.

Rats show similar metabolic features as mice. Hence, the rat has naturally low cholesterol levels and lacks CETP; cholesterol is transported by HDLs instead of LDLs. Therefore, rats are highly resistant to atherosclerosis development in a dietary way and need long periods to develop moderate atherosclerosis (70).

Strains and modifications

Sprague-Dawley and Wistar rats are frequently used strains for atherosclerosis and neointimal hyperplasia research. Rats that mimic certain aspects of cardiovascular pathophysiology, such as the spontaneously hypertensive rat (71) or the obese rat versus the lean Zucker rat [diabetes type 2 (72)], can be used to study the specific influence of key cardiovascular risk factors on neointimal hyperplasia. These models, combined with angioplasty procedures (eg, stenting), allow for a more translational investigation of cellular and molecular processes of restenosis compared with mere dietary or mechanical injury models (73). ApoE- and LDLr-deficient rats have been established recently and offer a good opportunity for high-throughput restenosis research in a combined injury + diet model (65). ApoE−/− and LDL−/− rats develop atherosclerosis on a natural diet within 1 year (74).

Balloon injury model

Because of their greater size compared with mice, restenosis development after balloon angioplasty can be simulated in rat aortas. To gain access to the vascular system, the carotid artery is most frequently used. To avoid bleeding, a cuff or ligature is placed. A balloon is then inserted (using a 2-F Fogarty catheter) and expanded at the selected position to cause hyperextension. Complete denudation of the vascular wall can be caused by forward and/or backward movement of the inflated balloon (75,76).

Initial VSMC-rich neointimal formation can be detected within a few days after endothelial denudation and can be observed reliably within 2 weeks, reaching its plateau at 21 days. It is possible to mimic the previously mentioned scenarios in high quantities of model animals at relatively low costs and outlay. This model is well established, relatively easy to use, and provides high reproducibility (77,78).

In-stent restenosis model

This experimental setup was established in the rat to evaluate standard human-sized stents in a model with higher throughput. In combination with high-atherogenic phenotypes such as ApoE deficiency, this model can reliably serve to study clinically relevant in-stent restenosis.

The procedure is comparable to the balloon injury model but upgraded by placing a stent in the injured vessel. The standard artery for this is the aorta, which can be reached through the carotid, transabdominal, or transiliac vessels. Using the iliac artery as an access point for aortic stenting provides higher survival rates because of reduced thrombosis rates (79). After 28 days, distinct in-stent neointimal formation primarily composed of VSMCs and extracellular matrix can be observed. The use of ApoE−/− rats can intensify restenosis development by more than 30%-40% (65).

Other rat models

Other models of atherosclerosis and restenosis have also been established and have been commonly used similarly to mice considering the aforementioned advantages. For example, the formation of neointimal lesions can be reproducibly provoked in western diet wild-type and in ApoE-deficient rats in models of carotid artery ligation or cuff placement (80, 81, 82).

Other Rodents

Hamsters and guinea pigs are also occasionally used for research on neointimal hyperplasia. The lipid metabolism of these other rodents is different from mice and rats and closely resembles human metabolism (83).

Rabbit Models of Neointimal Hyperplasia

Despite the high genetic match between humans and mice or rats, murine metabolism differs significantly from humans, limiting the translational potential. In contrast, rabbits offer a high translational capability for research on new drugs and diagnostic methods, as well as build a bridge between basic research in rodents and more translational research in larger animals.

Laboratory rabbits are large compared with their wild ancestors, whereas they take up much more space than a mouse or rat. Effort and costs are increased accordingly, whereas high throughput is not possible as with rodents. In addition, rabbits are social animals that depend on a certain degree of interaction with their comrades and claim higher demands of husbandry and enrichment.

The great advantage of rabbits is their lipid metabolism, which is similar to that of humans, providing a better opportunity to examine the consequences of revascularization under atherosclerotic preconditions. Like humans and unlike murinae, rabbits have high CETP activity, which is why they transport most cholesterol via LDL and VLDL (84). The rabbit ApoB is similar to the human isoform, as are the receptors for LDL and VLDL in the liver and on the surface of macrophages. The excretion of bile acid, which is synthesized from cholesterol, is significantly lower in rabbits and humans compared with that of rats and mice (42).

Because of these similarities, even wild-type rabbits are susceptible to a cholesterol-rich diet. An increase of only 2% in dietary cholesterol leads to a significant elevation of plasma cholesterol levels, and therefore, to the development of atherosclerotic lesions within weeks to a few months. However, because of the extremely high plasma cholesterol levels (1,500 to 3,000 mg/dL) and the associated development of atherosclerotic lesions that are rich with foamy macrophages, it is recommended to feed levels of only 0.3%-0.5% cholesterol to resemble human plaque formation (85, 86, 87). It is also important that a lack of other lipids within a high cholesterol diet leads to an increasing severity of atherosclerotic lesions. This is based on the mobilization of stored fats, which are more saturated than dietary ones, and thereby promote atherosclerosis development and bias results (88).

Important differences from humans exist in the amount of hepatic lipase synthesis and ApoA-II, which the rabbit is missing completely (89, 90). In addition, atherosclerotic lesions in rabbits are primarily characterized by foam cell-rich lesions (91).

For reproducibility, only male rabbits of similar age should be used because females are likely to have less stable cholesterol levels, which substantially affects plaque growth rate and composition.

Strains and modifications

Over time, 3 major breeding lines of rabbits have prevailed for cardiovascular research: New Zealand White, Japanese White, and Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic. While New Zealand White and Japanese white require a high cholesterol diet to develop atherosclerotic diseases, Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits already do so on a normal diet because of an inherited defect in the LDLr similar to human familial hypercholesterolemia. This is the major disadvantage of rabbits: all of these are outbred strains, which naturally leads to a high degree of interindividual variation. Although inbred strains exist, they are still problematic and not widely used. In addition, the use of transgenic rabbits is well established but still not common because of the increased costs and difficulty of genetic manipulability compared with that of rodents. Knock-out/-in animals are also possible. For example, ApoE-deficient knock-out rabbits, which show a higher susceptibility to hyperlipidemia, were recently created (92).

Injury models

Although rabbits on a high-fat diet will sooner or later develop spontaneous atherosclerosis by themselves, an inductive intervention is frequently performed to accelerate restenosis and the formation of neointimal lesions.

The surgical execution of the vascular damage differs hardly from that in rats and mice, but the point of interest is more on the methods of angioplasty that are similar to the procedures performed in humans. This makes the balloon and stent injury models particularly interesting in rabbits, because the focus is on translatability, and thus, the simulation of realistic clinical scenarios for testing new therapeutic and diagnostic approaches. An elegant way to enter a rabbit’s cardiovascular system is to gain access either through the central auricular artery or the lateral auricular vein by using Seldinger’s technique in combination with a microcatheter (93,94).

In a model of balloon injury combined with an atherogenic diet, atherosclerotic plaque development can be observed beginning at 7-10 days, whereas after 6-10 weeks, lumen-narrowing stenotic lesions are present. The substantial composition closely resembles those of humans, and neointima formation can be detected on histologic and molecular levels (95). In models of stent injury combined with a high cholesterol diet, in-stent restenosis with neointimal formation develops within 1 month (96,97).

Examination of restenosis within endarterectomy can also be performed in rabbits. In a model of rabbit carotid endarterectomy, neointimal formation occurred after 7 days, and inflammatory cytokines were directly correlated to vascular restenosis (98).

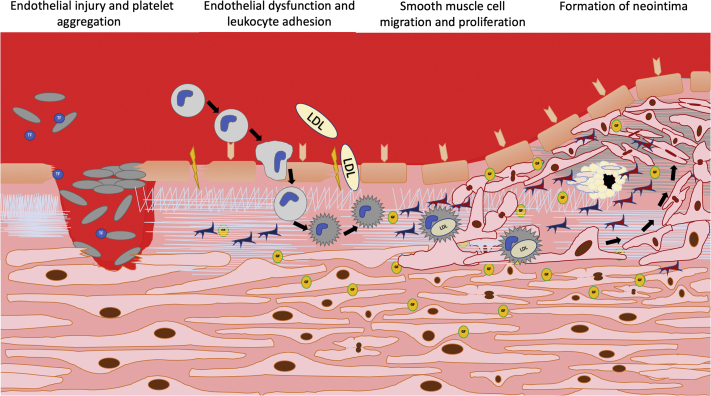

An example of the transcarotid endothelial denudation model of the iliac artery is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Exemplary Induction of Restenosis in a Rabbit Model

Neointimal hyperplasia can be induced by a combined dietary and mechanical injury approach. Therefore, the carotid artery is (A) surgically exposed, (B) ligated, punctured and subsequently a 5-F sheath is inserted. Catheterization of the iliac artery is subsequently performed, and endothelial denudation can be either performed using a (C) Fogarty catheter (arrow) or a (D) stent retriever (dotted arrow).

Large Animal Models of Neointimal Hyperplasia

Because of the technically simpler feasibility and the fairly good clinical translatability, many large animal models have been established. This includes, besides small ruminants, mainly pigs, dogs, and nonhuman primates. The translational potential of these models is particularly important. However, the use of such animals is also associated with significantly increased effort, costs, and (ethical) hurdles in the approval process, whereas high throughput and genetic manipulation are hardly possible.

Dogs

Dogs were used early in models because of their size, availability, relatively low cost, and ease of handling and care. They are naturally comparatively resistant to the development of atherosclerosis and neointimal hyperplasia, which leads to the dog being a rather unsuitable model in terms of translatability. Dietary induction of atherosclerosis is nearly impossible unless hypothyroidism is made simultaneously present (99). The main reasons for that are the canine lack of CETP and their coagulation system, which provides high fibrinolytic activity (100). Furthermore, dogs undergo thickening of the media and generally only develop a thin neointimal layer without substantial lumen narrowing, whereas the primarily affected vessels are predominantly smaller arteries (101,102).

Neointimal formation was observed in different injury models [eg, coronary artery (102), vein graft (103), carotid artery (104)] within time frames of 2 weeks, but its intensity remained moderate and was hardly affected by the level of vascular damage.

Pigs

Pigs have proven to be efficient in preclinical research. They have a comparable body size and/or weight (depending on the breed), a similar natural diet, and thus, have a metabolism and lipid profile comparable to humans. Also, the cardiovascular system of pigs is anatomically and physiologically similar to that of humans (105). Even on a normal diet, pigs can develop atherosclerotic plaques comparable to those of humans within 4 to 8 years (106). In addition, they are not only morphologically similar but are also similar in terms of lesion distribution along the arterial tree (107,108).

Important differences are the absence of lipoprotein(a) and the varying CETP activity in the pig (109,110). Hence, high cholesterol levels and the addition of cholic acid to the diet are necessary to induce accelerated atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases. Furthermore, without additional treatment, atherosclerosis in swine usually stops at the stage of foam cell agglomeration (111). These lesions primarily consist of smooth muscle cells with minimal macrophage involvement and VSMC proliferation, peaking at 7 days and declining at 28 days (112). Also, pigs show a remarkably higher thrombogenicity than humans (113). Using special breeding lines, diseases or an injury model, rapid lesion development, and neointimal formation can be provoked reliably. Pigs have become a dependable tool to mimic and investigate atherosclerosis development under pathologic preconditions like diabetes or familial hypercholesterolemia (114, 115).

With the Rapacz or inherited hyperlow-density lipoprotein and hypercholesterolemia pig, a porcine strain was selectively bred for naturally mutated ApoB and LDL genes, which led to high levels of LDL even on a normal diet, with the pig developing human-like atherosclerotic lesions within 2-4 years (115). This allowed researchers to follow the kinetics of a type of atherosclerosis, which in many aspects resembles that of humans, over a slower and more realistic course.

In addition, the possibility of genetic manipulation in minipigs is steadily improving. For example, there have already been LDL−/− minipigs developed and used for hypercholesteremia and atherosclerosis research. These minipigs develop human-like atherosclerosis on a high-fat/high-cholesterol diet in a shorter time (116). Swine offer good translational potential in both balloon and stent models, as well as vein graft and others (117). They enable the use of standardized equipment from human catheterization and develop postinterventional restenosis without further manipulation and even under natural feeding.

Nonhuman primates

As the closest relatives of humans, monkeys are a logical choice of an animal model. Anatomy and metabolism are similar to that of humans.

However, the greatest problem comes with this close relationship: The use of monkeys, especially humanoid primates, as experimental animals is ethically questionable and highly controversial. As a result, the hurdles to approve experiments on these animals are extremely difficult in most countries. Furthermore, there are high demands on effort and budget. The need for special facilities, equipment, personnel, space, enrichment, and financial expenditure are important factors.

Nevertheless, due to this relationship, monkeys also offer a high translation potential. The course of cardiovascular diseases as well as lesion development and topography are generally similar to humans (118). Especially within the realms of long-term studies, apes (superfamily hominoidea) are particularly suitable because of their longevity (119). For example, rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) reliably develop complex human-like atherosclerotic lesions on a cholesterol-rich atherogenic diet within a few years (120,121). For research with accelerated atherosclerosis, balloon injury models have been used primarily in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) on an atherogenic diet. M. fascicularis is much more sensitive to a high-fat diet, with a faster development of foam cell−rich plaques compared with other primates (119).

A summary of the most important features of each major species is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of Most Common Species Used for Animal Models of Restenosis

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mouse (Mus musculus dom.) | Rat (Rattus norvegicus dom.) | Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus dom.) | Pig (Sus scrofa dom.) | Dog (Canis lupus familiaris) | Non-human Primates | |

| Estimated median time since last common ancestor with human (million years) | ∼89 | ∼89 | ∼89 | ∼94 | ∼94 | ∼30 (Macaque) ∼6 (Chimpanzee) |

| Knockout/-in availability | +++ | ++ | + | ± (minipig) | − | ± (Cynomolgus, Rhesus) |

| Target vessels and average diameter in adult animal (mm) | Carotid artery: 0.6 Aorta: 0.8 Iliac artery: 0.3 Femoral artery: 0.2 |

Carotid artery: 1.0 Aorta: 2.0 Iliac artery: 1.0 Femoral artery: 0.5 |

Carotid artery: 2.0 Aorta: 2.8 Iliac artery: 2.2 Femoral artery: 1.3 |

Carotid artery: 5.5 Aorta: 16.5 Iliac artery: 6.0 Femoral artery: 4.0 (minipig) |

Carotid artery: 5.0 Aorta: 8.0 Iliac artery: 4.0 Femoral artery: 2.0 (mid-sized race/mongrel) |

Carotid artery: 4.5 Aorta: 6.6 Iliac artery: 4.5 Femoral artery: 1.5 (Cynomolgus) |

| Advantages | Uncomplicated Husbandry; High-throughput possible; High genetic manipulability; Many different strains available; Immuno-inflammatory system similar to humans; Pathologic preconditions available |

Uncomplicated Husbandry; High-throughput possible; Large enough for stent and balloon interventions; Pathologic preconditions available |

Lipid metabolism similar to human; Plaque formation with luminal stenosis similar to human; Large enough for human instruments and similar types of intervention |

Large enough for human instruments and interventions; Metabolism similar to human immunoinflammatory and cardiovascular system similar to human lesion morphology and distribution similar to humans; Pathologic preconditions available |

Large enough for human instruments and interventions; Easy handling |

Relationship to human metabolism similar to human Immunoinflammatory and cardiovascular system close to humans; Large enough for human instruments and interventions |

| Disadvantages | Different lipid metabolism to human; Lumen-narrowing stenoses or high-risk plaques hardly possible to develop; Too small for human-like interventions |

Different lipid metabolism to human; Different plaque formation compared to humans |

Elevated demands on space and care; Only moderate throughput possible; Lesions primarily consist of foam cells |

High demands on space and care; Only low-throughput possible; Atherosclerosis usually stops in stage of foam cell agglomeration |

High demands on space and care; Only low-throughput possible; Different metabolism and different immunoinflammatory response compared to humans; No lumen-narrowing plaques |

Very high demands on husbandry; Only very low throughput possible; High ethical hurdles |

Humanized Models for Restenosis

An increasingly important method for studying restenosis and neointimal hyperplasia is the use of humanized animal models. This is possible in various ways. On one hand, research can be performed through the previously discussed genetic modification. Here, for instance, the immune system of a model organism is adapted to that of humans. An example of this is the BRGSF-HIS mouse, in which all important immune cells have been replaced by their human equivalents through genetic manipulation (122).

On the other hand, various models using human vessel grafts have been successfully established in recent years. For example, a human mammary artery was denuded or stented ex vivo and then transplanted to the site of the abdominal aorta of a Rowett nude rat (123). Proliferating cells of the neointima were found after approximately 7 days (124), whereas a substantial narrowing of the lumen was reached after approximately 28 days (125).

With this method, the reaction of real human vessels and cells to trauma can be examined in vivo, although the impact of immunosuppressive medication must be considered.

Sex Differences Regarding Atherosclerotic Diseases

Female sexual hormones offer distinct atheroprotective properties, which are retained in most mammal species. Estrogens influence the lipid profile, the fibrinogen levels, and the nitric oxide levels, and thus, the reactivity of the vessel walls (126). The latest studies suggest that sex differences, especially female sexual hormones, primarily matter as long as the subject is young and/or healthy. In a study of LDLr−/− mice, females developed more severe hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis compared with males (127). In ETB-receptor deficient, balloon-injured rats, neointimal formation rose to the same high levels in males and in females, which was also not affected by hormones (128). Furthermore, a meta-analysis of pooled data of >200 catheter-injured Yucatan minipigs revealed no mentionable sex differences in thrombosis, neointimal formation, or luminal occlusion, but found significant differences in histomorphological indicators of resolution of fibrin deposition after drug delivery and the degree of inflammation (129).

Sex as a biological impact factor in animal models must be included in research considerations; however, differences are distinct, and no clear conclusions can be currently drawn.

Species-Specific Biological Differences Regarding Plaque Formation

For a proper understanding and the selection of a particular animal model for a specific research question, it is important to be aware of the biological differences associated with neointimal hyperplasia across various species. Although there is not only distinct variance in physiological and biological characteristics of different species, even different subspecies and breeding lines can have profound variation in the process of neointimal formation. A general problem, which particularly affects the realm of translational research, is the fact that those exact differences have been insufficiently investigated. This also applies to the interspecific biological differences of the key players involved in the development of atherosclerosis and neointimal hyperplasia. Acquainted species-specific features concerning neointimal formation are summarized in the following.

Vessel wall structure

First, there are significant structural variations along the vascular tree of a single individual, which must be considered when investigating neointimal hyperplasia. Different vascular territories have distinct hemodynamics and have differently composed arterial walls. An example of this is the change within the arteries from the elastic type close to the heart to the muscular type distant from the heart. It is also known that the arteries of various animals are different in their wall structure. However, this applies less to the composition of basic structures than much more to layer thickness and transition zones.

In addition, some species-specific features should be carefully considered. The internal elastic lamina (in coronary arteries) is only slightly expressed and strongly fenestrated in humans, whereas it is pronounced and continuous in small animals and has only minor weaknesses and/or fenestrations in larger animals (130). This understanding is essential, especially when working with a mechanical injury model, where the internal elastic lamina is damaged by angioplasty. Another structural difference is the content of elastin in the media, which is comparable in humans, baboons, pigs, and dogs, whereas it is hardly present in smaller species (130).

Endothelial cells

Endothelial cells of different species display clear phenotypic differences. This concerns morphological issues, like the prominence of the basal lamina, as well as cell metabolism and signaling mechanisms (131). Furthermore, there can be significant microstructural differences both on the cell membrane and content—cells of different species differ in receptors, MHC antigens, or other proteins and enzymes (132).

VSMCs

Little is known about species-specific differences in VSMC biology. While murine and porcine VSMCs start proliferating and migrating right after mechanical endothelial denudation, which proceeds for 2-3 weeks, VSMCs in humans and rabbits only start migrate after 5-7 days and continue to proceed for another 3-4 weeks (133, 134, 135, 136, 137). Hence, the mitotic rates also differ from porcine (highest) rates to murine to rabbit rates and at last human (lowest) rates (138).

Monocytes and macrophages

It is known that there are different subsets of monocytes in different species, which can be distinguished by a distinct surface marker expression and which exert divergent function in atherosclerosis and neointimal hyperplasia. The human CD14+CD16++ monocyte resembles the murine Ly-C6low and the porcine CD14low-CD163high populations, whereas the human CD14+CD16- monocyte is more similar to the murine Ly-C6high and the porcine CD14highCD163low subset. Studies showed that monocyte subsets are diverse between different breeds of swine, and that at least in mice and humans, an additional intermediate type of monocytes has been described (139). Many similarities have been discovered among these species-specific monocytes, but the differences have still not been adequately explored, which also applies to the macrophages arising from these monocytes (139). The murine Ly-C6high rises significantly in hypercholesterolemia, as studies in ApoE−/− mice suggest (140). Macrophages of the Mox type with proatherogenic properties have been found only in mice (141). Although it is known that human intermediate monocytes rise in atherosclerosis and restenosis, the actual functions of the different subsets are unknown in humans (142, 143, 144).

Neutrophils

Although humans have 40%-70% neutrophilic granulocytes in their blood, the latest studies suggest that their contribution to atherosclerosis is clearly less than it is in mice, which only have 10%-25% neutrophils (145). Although there are only low numbers within murine atherosclerotic plaques, neutrophils can secrete high amounts of the extracellular matrix-degrading elastase (146). This fact still has to be explored in larger animals and humans. Furthermore, healthy ruminants, pigs, rabbits, and rodents have a physiologically lymphocytic blood count, whereas it is granulocytic in primates and carnivores (feline and canine superfamilies). Unlike most other mammals, rabbits, hamsters, and guinea pigs do not have neutrophils at all. Instead, they have heterophilic (also called pseudoeosinophilic) granulocytes like birds (and many other nonmammals), which generally function the same way as neutrophils but contain acidophilic granules in their cytoplasm (147).

Thrombocytes

Thrombocytes show profound differences between various species, starting with size and shape toward different biophysical behavior. The size of platelets does not correlate with species size. With a volume of approximately 3.2-5.4 fL, mice, rats, and guinea pigs have the smallest thrombocytes. Dogs and pigs have intermediate-sized platelets, with approximately 7.6-8.3 fL, whereas cats have the largest, at approximately 15.1 fL (148). In contrast, human thrombocytes vary from 7-12 fL in mean platelet volume. In different species, platelets react differently to various aggregation factors. In this regard, interspecific variability exists in adhesive properties (149), in activation and intensity of aggregation response, as well as in reversibility and secretion behavior (150,151). Furthermore, platelets in various species differ in some of their structural components. The open canalicular system, which serves for spreading and granule fusion, is not present in every species. Studies suggest that open-canalicular-system-deficient species have delayed thrombocyte responses (152).

Aggregation behavior plays a huge role in pushing neointimal formation and restenosis due to the intense secretion of chemokines and growth factors such as PDGF. The thrombotic and fibrinolytic responses similarly differ through species. Although rabbits and swine develop significant thrombus formation, rats and dogs hardly do so (113,153). Within the primate family, the hemostatic systems are similar to each other, with low levels of clotting as well as intermediate lytic activity (154).

Conclusions

Although animal models provide detailed knowledge about restenosis, large variability in the neointimal hyperplasia response impairs clinical translatability. The sequence and weighting of the different factors, such as mechanical stressors, endothelial permeability, monocyte influx, VSMC proliferation, and migration, as well as synthesis of extracellular matrix, need to be further investigated. For this purpose, it is necessary to be aware of the specific characteristics and distinct differences among the corresponding animal models.

To provide valid and reproducible results and to avoid fallacy and translational failure, it is necessary to know the biological differences among species to tailor the experimental setup properly.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

Dr Wildgruber was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG (WI 3686/7-1).

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.World Health Organization The top 10 causes of death. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 2.Otsuka F., Bryne R.A., Yahagi K., et al. Neoatherosclerosis: overview of histopathologic findings and implications for intravascular imaging assessment. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(32):2147–2159. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahanchi S.S., Tsihlis N.D., Kibbe M.R. The role of nitric oxide in the pathophysiology of intimal hyperplasia. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(6):A64–A73. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray W.A., Granada J.F. Drug-coated balloons for the prevention of vascular restenosis. Circulation. 2010;121(24):2672–2680. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.936922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Beusekom H.M., Whelan D.M., Hofma S.H., et al. Long-term endothelial dysfunction is more pronounced after stenting than after balloon angioplasty in porcine coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(4):1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rozenman Y., Gilon D., Welber D., Sapoznikov D., Gotsman M.S. Clinical and angiographic predictors of immediate recoil after successful coronary angioplasty and relation to late restenosis. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72(14):1020–1025. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90856-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bermejo J., Botas J., Garcia E., et al. Mechanisms of residual lumen stenosis after high-pressure stent implantation: a quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 1998;98(2):112–118. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melo L.G., Gnecchi M., Ward C.A., Dzau V.J., et al. In: Cardiovascular Medicine. Willerson J.T., Cohn J.N., Wellens H.J.J., Holmes D.R. Jr., editors. Springer; 2007. Vascular remodeling in health and disease; pp. 1541–1565. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonatti J., Oberhuber A., Schachner T., et al. Neointimal hyperplasia in coronary vein grafts: pathophysiology and prevention of a significant clinical problem. Heart Surg Forum. 2004;7(1):72–87. doi: 10.1532/hsf.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoji M., Koba S., Kobayashi Y. Roles of bone-marrow-derived cells and inflammatory cytokines in neointimal hyperplasia after vascular injury. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:945127. doi: 10.1155/2014/945127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien E.R., Ma X., Simard T., Pourdjabbar A., Hibbert B. Pathogenesis of neointima formation following vascular injury. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;11(1):30–39. doi: 10.2174/187152911795945169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen N.X., Kiattisunthorn K., O’Neill K.D., et al. Decreased microRNA is involved in the vascular remodeling abnormalities in chronic kidney disease (CKD) PloS One. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Menn R., Bara L., Samama M. Ultrastructure of a model of thrombogenesis induced by mechanical injury. J Submicrosc Cytol. 1981;13(4):537–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gitel S.N., Wessler S. Dose-dependent antithrombotic effect of warfarin in rabbits. Blood. 1983;61(3):435–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blann A.D. Assessment of endothelial dysfunction: focus on atherothrombotic disease. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2003;33(5-6):256–261. doi: 10.1159/000083811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davenport A.P., Hyndman K.A., Dhaurn N., et al. Endothelin. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(2):357–418. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X., Khalil R.A. Matrix metalloproteinases, vascular remodeling, and vascular disease. Adv Pharmacol. 2018;81:241–330. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H.R., Gallant C., Leavis P.C., Gunst S.J., Morgan K.G. Cytoskeletal remodeling in differentiated vascular smooth muscle is actin isoform dependent and stimulus dependent. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295(3):C768–C778. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00174.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giblin S.P., Midwood K.S. Tenascin-C: form versus function. Cell Adhes Migr. 2015;9(1-2):48–82. doi: 10.4161/19336918.2014.987587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerhardt T., Ley K. Monocyte trafficking across the vessel wall. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;107(3):321–330. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou X., Hansson G. Detection of B cells and proinflammatory cytokines in atherosclerotic plaques of hypercholesterolaemic apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Scand J Immunol. 1999;50(1):25–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isoda K., Shiigai M., Ishigami N., et al. Deficiency of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist promotes neointimal formation after injury. Circulation. 2003;108(5):516–518. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085567.18648.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaabane C., Otsuka F., Virmani R., Bochaton-Piallat M.-L., et al. Biological responses in stented arteries. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99(2):353–363. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y., Luo N.-S., Ying R., et al. Macrophage-derived foam cells impair endothelial barrier function by inducing endothelial-mesenchymal transition via CCL-4. Int J Mol Med. 2017;40(2):558–568. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sales V.L., Engelmayr G.C., Jr., Mettler B.A., et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 modulates extracellular matrix production, proliferation, and apoptosis of endothelial progenitor cells in tissue-engineering scaffolds. Circulation. 2006;114(1 Suppl):I193–I199. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li D.-J., Fu H., Tong J., et al. Cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway inhibits neointimal hyperplasia by suppressing inflammation and oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2018;15:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen P.-Y., Qin L., Li G., Tellides G., Simons M. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling regulates transforming growth factor beta (TGF β)-dependent smooth muscle cell phenotype modulation. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep33407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez D., Owens G.K. Smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95(2):156–164. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerthoffer W.T. Mechanisms of vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circ Res. 2007;100(5):607–621. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258492.96097.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durham A.L., Speer M.Y., Scatena M., Giachelli C.M., Shanahan C.M. Role of smooth muscle cells in vascular calcification: implications in atherosclerosis and arterial stiffness. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114(4):590–600. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu S.-B., Zhu J., Xi E.-P., Wang R.-P., Zhang Y. TGF-β1 induces human aortic vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype switch through PI3K/AKT/ID2 signaling. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7(12):2764. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett M.R., Sinha S., Owens G.K. Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118(4):692–702. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wun K., Theriault B.R., Pierre J.F., et al. Microbiota control acute arterial inflammation and neointimal hyperplasia development after arterial injury. PloS One. 2018;13(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma J., Li H. The role of gut microbiota in atherosclerosis and hypertension. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1082. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen E.B., Shapiro K.E., Wun K., et al. Microbial colonization of germ-free mice restores neointimal hyperplasia development after arterial injury. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;(5) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Komiyama H., Takano M., Hata N., et al. Neoatherosclerosis: coronary stents seal atherosclerotic lesions but result in making a new problem of atherosclerosis. World J Cardiol. 2015;7(11):776. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i11.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kufner S., Byrne R.A., Joner M., Kastrati A., et al. In-stent-neoatherosklerose nach perkutaner koronarintervention. CardioVasc. 2014;14(2):46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenfeld M.E., Averill M.M., Bennett B.J., Schwartz S.M., et al. Progression and disruption of advanced atherosclerotic plaques in murine models. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9(3):210–216. doi: 10.2174/138945008783755575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moulton K.S., Vakili K., Zurakowski D., et al. Inhibition of plaque neovascularization reduces macrophage accumulation and progression of advanced atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(8):4736–4741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730843100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gordon S.M., Li H., Zhu X., Shah A.S., Lu L.J., Davidson W.S. A comparison of the mouse and human lipoproteome: suitability of the mouse model for studies of human lipoproteins. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(6):2686–2695. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Endo A. Regulation of cholesterol synthesis, as focused on the regulation of HMG-CoA reductase (author's transl). Seikagaku. J Japan Biochem Soc. 1980;52(10):1033–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamoto A. Three obstacles which confronted the development of compactin. Atherosclerosis. 2004;5(3):21. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sasaki T., Kuzuya M., Nakamura K., et al. A simple method of plaque rupture induction in apolipoprotein E–deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vascular Biol. 2006;26(6):1304–1309. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000219687.71607.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hobbs H.H., Russsell D.W., Brown M.S., Goldstein J.L., et al. The LDL receptor locus in familial hypercholesterolemia: mutational analysis of a membrane protein. Ann Rev Genet. 1990;24(1):133–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar A., Lindner V. Remodeling with neointima formation in the mouse carotid artery after cessation of blood flow. Arterioscler Thromb Vascular Biol. 1997;17(10):2238–2244. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson S.M., Liaw L., Lindner V. In: Mouse Models of Vascular Diseases. Sata M., editor. Springer; 2016. Ligation of the mouse common carotid artery; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Korshunov V.A., Berk B.C. Flow-induced vascular remodeling in the mouse: a model for carotid intima-media thickening. Arterioscler Thromb Vascular Biol. 2003;23(12):2185–2191. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000103120.06092.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nam D., Ni C.-W., Rezvan A., et al. A model of disturbed flow-induced atherosclerosis in mouse carotid artery by partial ligation and a simple method of RNA isolation from carotid endothelium. J Vis Exp. 2010;40 doi: 10.3791/1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moroi M., Zhang L., Yasuda T., et al. Interaction of genetic deficiency of endothelial nitric oxide, gender, and pregnancy in vascular response to injury in mice. J Clin Investig. 1998;101(6):1225–1232. doi: 10.1172/JCI1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwaiberger A.V., Heiss E.H., Cabaravdic M., et al. Indirubin-3′-monoxime blocks vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by inhibition of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling and reduces neointima formation in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vascular Biol. 2010;30(12):2475–2481. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.212654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuhlmann M.T., Cuhlmann S., Hoppe I., et al. Implantation of a carotid cuff for triggering shear-stress induced atherosclerosis in mice. J Vis Exp. 2012;59 doi: 10.3791/3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kubota T., Kubota N. In: Mouse Models of Vascular Diseases. Sata M., editor. Springer; 2016. Cuff-induced neointimal formation in mouse models; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takayama T., Shi X., Wang B., et al. A murine model of arterial restenosis: technical aspects of femoral wire injury. J Vis Exp. 2015;97 doi: 10.3791/52561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sata M., Tanaka K., Fukuda D. In: Mouse Models of Vascular Diseases. Sata M., editor. Springer; 2016. Wire-mediated endovascular injury that induces rapid onset of medial cell apoptosis followed by reproducible neointimal hyperplasia; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lindner V., Fingerle J.Y., Reidy M.A. Mouse model of arterial injury. Circ Res. 1993;73(5):792–796. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.5.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zou Y., Dietrich H., Hu Y., Metzler B., Wick G., Xu Q. Mouse model of venous bypass graft arteriosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(4):1301–1310. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65675-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cooley B.C. Murine model of neointimal formation and stenosis in vein grafts. Arterioscler Thromb Vascular Biol. 2004;24(7):1180–1185. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000129330.19057.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cooley B.C., Nevado J., Mellas J., et al. TGF-β signaling mediates endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) during vein graft remodeling. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(227):227ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu Y., Mayr M., Metzler B., et al. Both donor and recipient origins of smooth muscle cells in vein graft atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res. 2002;91(7):e13–e20. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000037090.34760.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maroney S.A., Cooley B.C., Ferrel J.P., et al. Murine hematopoietic cell tissue factor pathway inhibitor limits thrombus growth. Arterioscler Thromb Vascular Biol. 2011;31(4):821–826. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.220293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cooley B.C. In: Mouse Models of Vascular Diseases. Sata M., editor. Springer; 2016. Murine models of vein grafting; pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsumoto Y., Umemura K. In: Mouse Models of Vascular Diseases. Sata M., editor. Springer; 2016. Photochemically induced endothelial injury; pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shimazawa M., Watanabe S., Kondo K., et al. Neutrophil accumulation promotes intimal hyperplasia after photochemically induced arterial injury in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;520(1-3):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodriguez-Menocal L., Wei Y., Pham S.M., et al. A novel mouse model of in-stent restenosis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209(2):359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.09.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cornelissen A., Simsekyilmaz S., Liehn E., et al. Apolipoprotein E deficient rats generated via zinc-finger nucleases exhibit pronounced in-stent restenosis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54541-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carmeliet P., Moons L., Stassen J.M., et al. Vascular wound healing and neointima formation induced by perivascular electric injury in mice. Am J Pathol. 1997;150(2):761. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu Q. Mouse models of arteriosclerosis: from arterial injuries to vascular grafts. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63270-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cai C., Zhao C., Kilari S., et al. Experimental murine arteriovenous fistula model to study restenosis after transluminal angioplasty. Lab Animal. 2020;49(11):320–334. doi: 10.1038/s41684-020-00659-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Isaji T., Dardik A. Experimental Models of Cardiovascular Diseases. Springer; 2018. The mouse aortocaval fistula model with intraluminal drug delivery; pp. 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Russell J.C., Proctor S.D. Small animal models of cardiovascular disease: tools for the study of the roles of metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2006;15(6):318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nestor Kalinoski A.L., Ramdoth R.S., Langenderfer K.M., et al. Neointimal hyperplasia and vasoreactivity are controlled by genetic elements on rat chromosome 3. Hypertension. 2010;55(2):555–561. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.142505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Enayati A., Johnston T.P., Sahebkar A. Anti-atherosclerotic effects of spice-derived phytochemicals. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28(6):1197–1223. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666200505084620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Seidman J.D., Tavassoli F.A. Mesonephric hyperplasia of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic study of 51 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1995;14(4):293–299. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199510000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao Y., Yang Y., Xing R., et al. Hyperlipidemia induces typical atherosclerosis development in Ldlr and Apoe deficient rats. Atherosclerosis. 2018;271:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park S.-H., Marso S.P., Zhou Z., et al. Neointimal hyperplasia after arterial injury is increased in a rat model of non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2001;104(7):815–819. doi: 10.1161/hc3301.092789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maffia P., Ianaro A., Sorrentino R., et al. Beneficial effects of NO-releasing derivative of flurbiprofen (HCT-1026) in rat model of vascular injury and restenosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vascular Biol. 2002;22(2):263–267. doi: 10.1161/hq0202.104064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamasaki M., Kawai J., Nakaoka T., et al. Adrenomedullin overexpression to inhibit cuff-induced arterial intimal formation. Hypertension. 2003;41(2):302–307. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000050645.11117.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Indolfi C., Esposito G., Di Lorenzo E., et al. Smooth muscle cell proliferation is proportional to the degree of balloon injury in a rat model of angioplasty. Circulation. 1995;92(5):1230–1235. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oyamada S., Ma X., Wu T., et al. Trans-iliac rat aorta stenting: a novel high throughput preclinical stent model for restenosis and thrombosis. J Surg Res. 2011;166(1):e91–e95. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.11.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jahnke T., Karbe U., Schafer F.K.W., et al. Characterization of a new double-injury restenosis model in the rat aorta. J Endovasc Ther. 2005;12(3):318–331. doi: 10.1583/04-1466MR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pahk K., Noh H., Joung C., et al. A novel CD147 inhibitor, SP-8356, reduces neointimal hyperplasia and arterial stiffness in a rat model of partial carotid artery ligation. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-2024-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wei S., Zhang Y., Su L., et al. Apolipoprotein E-deficient rats develop atherosclerotic plaques in partially ligated carotid arteries. Atherosclerosis. 2015;243(2):589–592. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao Y., Qu H., Wang Y., et al. Small rodent models of atherosclerosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;129:110426. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tall A.R. Plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein. J Lipid Res. 1993;34(8):1255–1274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bocan T.M., Mueller S.B., Mazur M.J., et al. The relationship between the degree of dietary-induced hypercholesterolemia in the rabbit and atherosclerotic lesion formation. Atherosclerosis. 1993;102(1):9–22. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(93)90080-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]