Abstract

We have designed species-specific oligonucleotides which permit the differential detection of two species of cestodes, Taenia saginata and Taenia solium. The oligonucleotides contain sequences established for two previously reported, noncoding DNA fragments cloned from a genomic library of T. saginata. The first, which is T. saginata specific (fragment HDP1), is a repetitive sequence with a 53-bp monomeric unit repeated 24 times in direct tandem along the 1,272-bp fragment. From this sequence the two oligonucleotides that were selected (oligonucleotides PTs4F1 and PTs4R1) specifically amplified genomic DNA (gDNA) from T. saginata but not T. solium or other related cestodes and had a sensitivity down to 10 pg of T. saginata gDNA. The second DNA fragment (fragment HDP2; 3,954 bp) hybridized to both T. saginata and T. solium DNAs and was not a repetitive sequence. Three oligonucleotides (oligonucleotides PTs7S35F1, PTs7S35F2, and PTs7S35R1) designed from the sequence of HDP2 allowed the differential amplification of gDNAs from T. saginata, T. solium, and Echinococcus granulosus in a multiplex PCR, which exhibits a sensitivity of 10 pg.

Taenia saginata and Taenia solium are the two taeniids of greatest economic and medical importance, causing bovine and porcine cysticercosis and taeniasis in humans. In addition, T. solium eggs can infect humans, often giving rise to fatal neurocysticercosis (12, 39). Infections with these cestodes are therefore a serious public health problem in areas of endemicity. In addition, an increase in the number of cases in areas of nonendemicity has been observed in recent years (36).

At present, there is no rapid, facile means of diagnosis of human taeniasis and there is an obvious need for sensitive and specific differential tests for T. solium and T. saginata detection and interruption of human cysticercosis transmission. Conventional coproscopical examination has a low specificity and sensitivity (29), whereas coproantigen detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, although sensitive, suffers from poor specificity due to cross-reactions with other taeniids and related helminths (1, 8, 23, 24). A recently developed Western blot assay measures antibody to adult Taenia and thus does not necessarily detect an active infection (43). Furthermore, this assay requires the preparation of secreted antigens from immature adult tapeworms recovered from immunosuppressed hamsters, which is impractical for routine use. The use of DNA probes, as successfully used for species-specific detection of various parasites (2, 11, 14, 35, 37, 44), including T. solium and T. saginata (5, 13, 19, 32), is time-consuming and relatively insensitive. More recently, however, PCR with oligonucleotide primers derived from such species-specific probes (15, 16, 26, 27) has provided a truly rapid and sensitive method for the identification of helminth parasites in general.

This paper describes the design of oligonucleotides, based on the sequences of two previously described diagnostic DNA tests (19), which permitted positive identification of T. saginata and T. solium. The first DNA probe, probe HDP1, is a repetitive sequence that yielded PCR probes specific for T. saginata, while the second sequence, probe HDP2, yielded a multiplex PCR probes which allowed the simultaneous identification of T. solium, T. saginata, and Echinococcus granulosus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Extraction and sources of DNA.

Genomic DNAs (gDNAs) of T. saginata, T. solium, Taenia taeniformis (Belgian isolate), T. taeniformis (Malaysian isolate), and E. granulosus were obtained by a phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation protocol (34). Bovine and human DNAs were purchased commercially (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.).

Subcloning strategy.

The HDP1 and HDP2 genomic sequences were cloned following the differential screening of a T. saginata λgt10 genomic library (19). Since one of the HDP1 EcoRI restriction enzyme digestion sites was damaged, the HDP1 fragment was isolated from the recombinant phage by EcoRI-BamHI (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.) digestion. A 5,100-bp fragment which was composed of a 1,272-bp fragment of T. saginata gDNA and a 3,800-bp fragment from the short arm of λgt10 phage was obtained. The insert was subcloned into the EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites of pBluescript KS+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and the recombinant plasmid (pBluescript KS+, λgt10 fragment, HDP1) was named pPTs4. The HDP2 sequence was isolated from the recombinant phage by EcoRI digestion (Promega Corporation), yielding a 3,954-bp fragment which was subcloned into the EcoRI site of pBluescript KS+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.).

HDP1 and HDP2 sequencing.

A designated progressive unidirectional erase strategy (Promega Corporation) was used in order to sequence the T. saginata DNA inserts. Sequencing of HDP1 and HDP2 was carried out with two automated sequencing systems: fluorescence-based labeling with the ABI PRISM system (Perkin-Elmer, Langen, Germany) and the ALF system (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). The HDP1 and HDP2 DNA sequences were compared with those available in the EMBL databank by using software packages from the Genetics Computer Group (9).

Slot blot hybridization.

Samples of either gDNA or plasmid DNA were prepared after first diluting the DNA to the required concentrations and then denaturation with 0.3 M NaOH and incubation at 80°C for 10 min, followed by neutralization with 0.25 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–0.25 M HCl–12.5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate [pH 7.0]) buffer. The samples were then transferred by vacuum onto nitrocellulose membranes with a slot blot manifold apparatus (Shleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Electrophoresis, Southern blotting, labeling, and hybridization procedures.

The genomic organizations of the HDP1 and the HDP2 DNA sequences were examined as follows. First, 3-μg aliquots of T. saginata gDNA were digested to completion with different restriction endonucleases (Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, England; Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany; Promega Corporation) by following the procedures recommended by the manufacturers. Electrophoresis of the digested DNA samples and subsequent transfer to positively charged nylon membranes (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH) were carried out by standard procedures (40). The HDP1 and HDP2 DNA probes were nonradioactively labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH) by a random oligonucleotide primer method, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Hybridizations were conducted overnight under high-stringency conditions at 68°C. After hybridization, the filters were washed at 68°C for 10 min in 2× SSC–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and then for a further 40 min in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS. The immunodetection was carried out with antidigoxigenin conjugated with alkaline phosphatase, and the immune complexes were visualized with the chemiluminescence substrate CSPD (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH) on X-ray film with an intensifying screen at room temperature for 15 min, as described in the manufacturer's instructions.

In order to identify unique sequences of HDP2 that do not occur in the T. solium genome, 5-μg samples of T. saginata and T. solium gDNAs were digested to completion with the ClaI restriction endonuclease (Amersham Life Science), as recommended by the manufacturer. Southern blotting, probe labeling, and hybridization were carried out as described above. The probes used were three nonoverlapping fragments derived from the HDP2 sequence and were designated 5PHDP2, IPHDP2, and 3PHDP2.

Design of HDP1 and HDP2 primers.

DNA sequence analysis was carried out with the Primer Select Lasergene program (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.). The HDP1 sequence was used to design two oligonucleotide primers, primers PTs4F1 (5′-GCAGTGTGCTGAAGATGAATA-3′) and PTs4R1 (5′-GAATTTGGCTCTCACTGAATG-3′). An internal primer, primer PTs4I1 (5′-ATACTACCAAATCGCAT-3′), was also prepared. The HDP2 sequence was used to design three oligonucleotide primers, primers PTs7S5F1 (5′-CAGTGGCATAGCAGAGGAGGAA-3′), PTs7S35F2 (5′-CTTCTCAATTCTAGTCGCTGTGGT-3′), and PTs7S35R1 (5′-GGACGAAGAATGGAGTTGAAGGT-3′). The primers were synthesized by Gibco BRL.

DNA amplification.

PCR with HDP1-based primers was performed in a total volume of 25 μl containing PCR buffer (PCR buffer I; Perkin-Elmer), 0.4% glycerol, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) at a concentration of 200 mM, 0.25 μM PTs4F1, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). PCR conditions were 94°C for 5 min (initial denaturation), followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 10 min (final extension). PTs4R1 (0.5 μM) was added to the reaction mixture at the 25th cycle. Multiplex PCR with HDP2-based primers was performed in a total volume of 25 μl with PCR buffer (PCR buffer I; Perkin-Elmer) and final concentrations of 0.4% glycerol, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Pharmacia) at a concentration of 200 mM, 0.5 μM primer PTs7S35F1, 0.5 μM primer PTs7S35F2, 1 mM primer PTs7S35R1, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). Conditions for the multiplex PCR with HDP2-based primers were 94°C for 5 min (initial denaturation), followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 56.5°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 10 min (final extension). Amplifications were carried out in a GeneAmp TM PCR System 2400 Thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer). The amplification products were separated on 2% agarose gels and were visualized under UV light by ethidium bromide staining.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The HDP1 sequence was assigned accession no. AJ133764 and the HDP2 sequence was assigned accession no. AJ133740 (EBI, EMBL GenBank, and DDJB database).

RESULTS

HDP1 and HDP2 sequencing.

For sequencing, the HDP2 DNA fragment was directly subcloned from λgt10 phage into the pBluescript SK+ plasmid, and then 25 nested deleted clones were selected and sequenced. A different strategy was necessary for HDP1, as one of the two EcoRI digestion sites had been lost from the recombinant phage (see Materials and Methods), and so five nested deleted clones were selected and sequenced to determine the full sequence of HDP2. The full sequences of HDP1 and HDP2 are shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, respectively.

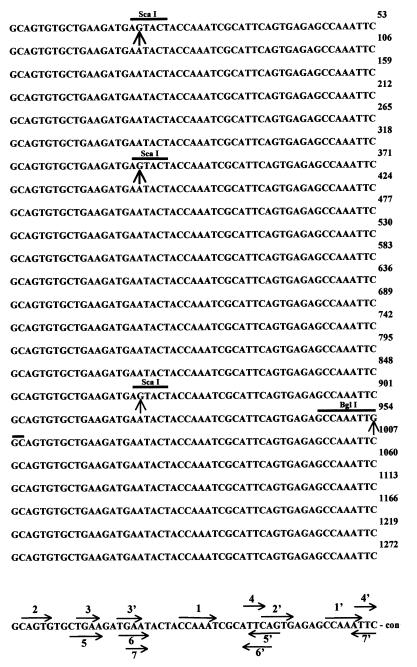

FIG. 1.

Repetitive T. saginata HDP1 sequence (1,272 bp). Each monomeric unit is represented by a line. Twenty-four repeats are included. Substitution point mutations are indicated by an arrow below each mutation. The restriction enzyme recognition sites are indicated by the lines. Direct and inverted internal repeats are indicated by arrows above and below the consensus sequence (con), respectively.

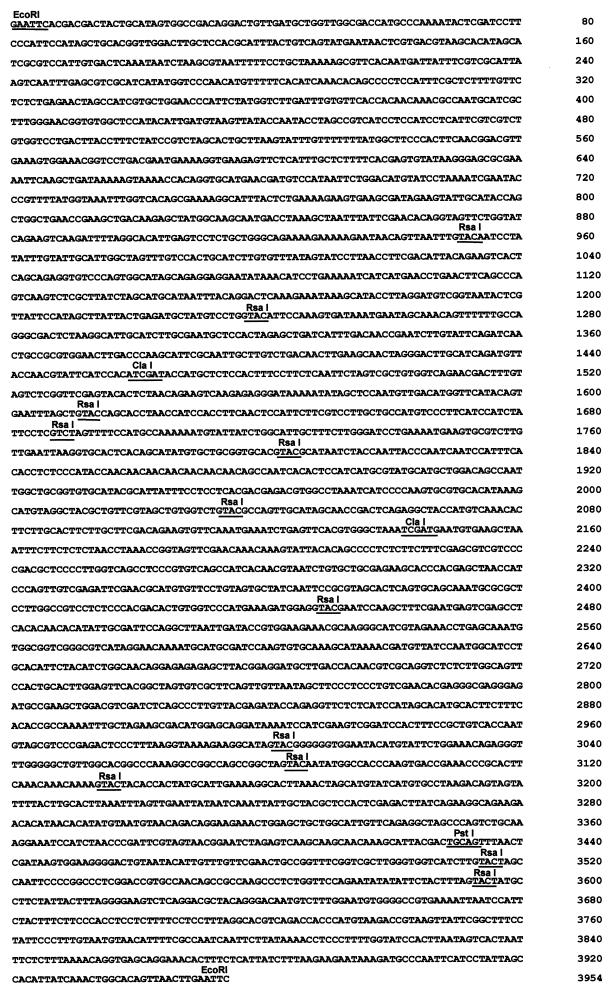

FIG. 2.

Nonrepetitive T. saginata HDP2 sequence (3,954 bp). The restriction enzyme recognition sites are indicated by the lines.

HDP1 and HDP2 sequence analysis.

The 1,272-bp nucleotide sequence of HDP1 was highly repetitive, with 24 sequences, each of 53 bp, in tandem array. An unambiguous consensus sequence was derived from the 24 monomeric motifs (Fig. 1). All of the motifs were remarkably similar, with a maximum difference of only four bases. Strikingly, the same adenine-to-guanine transition occurred at nucleotide 19 in three of the motifs located in the 4th, 7th, and 17th positions within the sequence. The fourth mutation, which appeared in the 18th motif, was a cytidine-to-guanine transversion. These mutations yielded three new ScaI recognition sites and one BglI recognition site within the mutated motifs. Thus, there was only a 0.3% sequence divergence from the established consensus sequence.

The HDP1 fragment had an A+T content of 55%. It showed internal repeats as one direct repeat (1/1′) of 6 bp and one of 5 bp (2/2′), two of 4 bp (3/3′, 4/4′), and three of inverted repeats, one of 5 bp (5/5′) and one of 4 bp (6/6′ and 7/7′). The 3,954-bp HDP2 nucleotide sequence was nonrepetitive, with an A+T content of 45% and no significant internal repeats. Stop codons occurred frequently in both sequences, and therefore, no open reading frames of significant length were identified. Finally, no significant homologies were found with sequences reported in either the GenBank or the EMBL data bank.

Genomic organization of HDP1 and HDP2 probes in T. saginata genome.

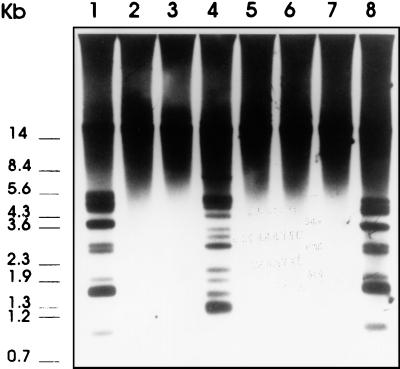

In order to study the genomic organization of the HDP1 and the HDP2 sequences, taeniid gDNA was digested to completion with several restriction enzymes, transferred to membranes, and hybridized with both HDP1 and HDP2 under high-stringency conditions. With the HDP1 probe, different patterns were obtained depending on the restriction enzyme used (Fig. 3). Thus, ScaI, EcoRI, and RsaI digestions yielded a regular ladder pattern with hybridization fragments of different sizes. In contrast, digestion of gDNA with restriction enzymes specific for sequences not located within the HDP1 sequence (PstI, HindIII, SalI, XhoI, and BamHI) yielded a single band that was larger than 23 kb and that hybridized with the HDP1 probe. Taking into account the hybridization patterns, the HDP1 restriction map, and the sequence information, we calculated that the 53-bp monomers are arranged in direct tandem arrays along 23 kb or more in the T. saginata genome.

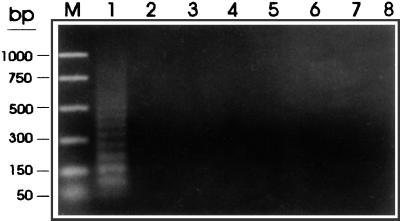

FIG. 3.

Southern blot of T. saginata gDNA (3 μg) cleaved with various restriction enzymes (ScaI [lane 1], PstI [lane 2], HindIII [lane 3], EcoRI [lane 4], SalI [lane 5], XhoI [lane 6], BamHI [lane 7], and RsaI [lane 8]) and probed with the digoxigenin-labeled T. saginata HDP1 probe.

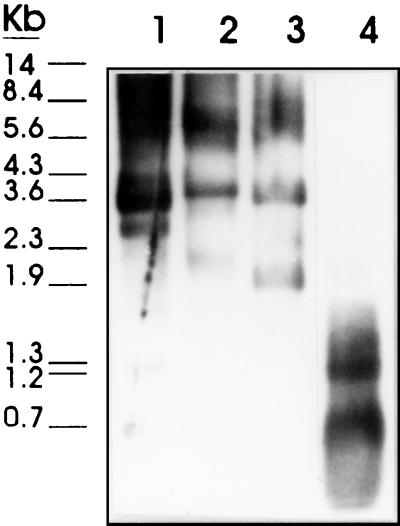

When similar experiments were done by Southern blotting with the HDP2 probe, digestion of T. saginata gDNA with ClaI, PstI, EcoRI, and RsaI enzymes yielded different restriction patterns, depending on the enzyme used, and an irregular ladder distribution. These data suggested that the HDP2 fragment did not contain repeated sequences within the T. saginata genome (Fig. 4). It is important to note that complete digestion of T. saginata gDNA with all the enzymes mentioned above was confirmed by analyzing the digested samples by agarose gel electrophoresis (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Southern blot of T. saginata gDNA (3 μg) cleaved with various restriction enzymes (ClaI [lane 1], PstI [lane 2], EcoRI [lane 3], and RsaI [lane 4]) and probed with the digoxigenin-labeled HDP2 probe.

Copy number of the 53-bp monomers in T. saginata genome.

The copy number of the 53-bp monomer in the T. saginata genome was determined by slot blot analysis (Fig. 5) by titrating DNA purified from T. saginata metacestodes and from the HDP1-containing pBluescript KS+ plasmid pPTs4 (the HDP1 sequence accounts for 15.9% of the recombinant plasmid) and using the digoxigenin-labeled HDP1 sequence as the probe. The slots containing 100 ng of T. saginata gDNA and 2.85 ng of pPTs4 DNA showed identical hybridization intensities, whereas the pBluescript KS+ nonrecombinant vector did not hybridize (data not shown). These results indicated that the HDP1 sequence represented approximately 0.4% of the T. saginata DNA. Assuming that the size of the T. saginata genome is similar to that of the closely related organism E. granulosus (genome size, 1.5 × 108-bp) (32), we calculated 11,321 repeats of the 53-bp monomer per haploid genome of the parasite.

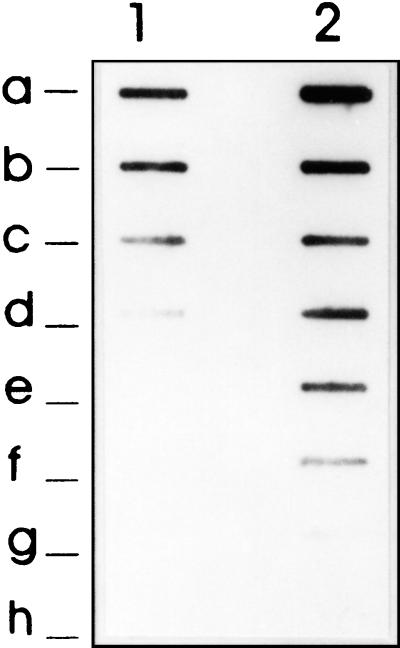

FIG. 5.

Sensitivity of the T. saginata HDP1 probe. Dilutions of T. saginata gDNA (200 ng [slot 1a], 100 ng [slot 1b], 50 ng [slot 1c], 25 ng [slot 1d], 12.5 ng [slot 1e], 6.25 ng [slot 1f], 3 ng [slot 1g], 1.5 ng [slot 1h]) and pPTs4 recombinant plasmid DNA (50 ng [slot 2a], 10 ng [slot 2b], 5 ng [slot 2c], 2.5 ng [slot 2d], 1.25 ng [slot 2e], 0.6 ng [slot 2f], 0.3 ng [slot 2g], 0.15 ng [slot 2h]) were probed in a slot blot system with the digoxigenin-labeled T. saginata HDP1 probe.

Design of PCR primers derived from HDP1 and HDP2 sequences.

The two oligonucleotide primers (primers PTs4F1 and PTs4R1) designed from the HDP1 sequence (Fig. 6A) were manually selected because the repetitive nature of the DNA sequence precluded use of the Primer Select Lasergene program. The three oligonucleotide primers prepared from the HDP2 sequence (primers PTs7S35F1, PTs7S35F2, and PTs7S35R1) were designed after demonstrating that digestion of HDP2 with SphI and ClaI restriction endonucleases yielded three nonoverlapping fragments (fragments 5PHDP2, IPHDP2, and 3PHDP2) (Fig. 6B). When these were tested by Southern blotting with T. saginata and T. solium gDNAs digested with ClaI, hybridization of T. solium DNA occurred with the fragment IPHDP2 and 3PHDP2 sequences but not with the fragment 5PHDP2 sequence (Fig. 7). As this suggested that the 5PHDP2 sequence was not included in the T. solium genome, we used the Primer Select Lasergene program to synthesize three primers (primers PTs7S35F1, PTs7S35F2, and PTs7S35R1). Primer PTs7S35F1 was based on the 5PHDP2 sequence, and primers PTs7S35F2 and PTs7S35R1 were designed from the IPHDP2 sequence (Fig. 6B).

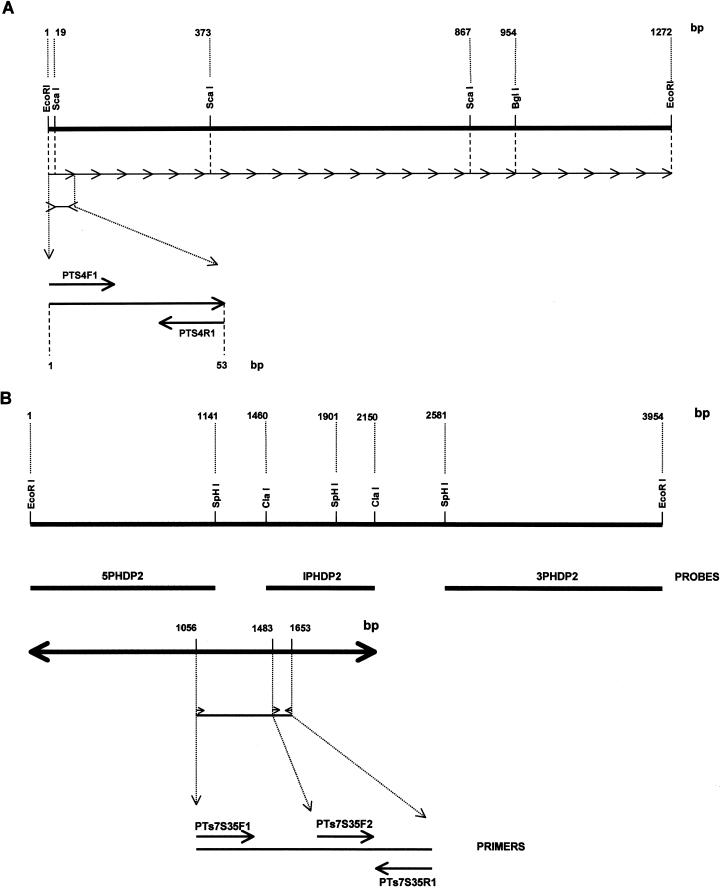

FIG. 6.

(A) Locations of the PTs4F1 and PTs4R1 oligonucleotide primers within the 1,272-bp T. saginata HDP1 repetitive DNA sequence. The 24 repetitive units are indicated by continuous arrows. The restriction enzyme sites are indicated by lines, and the PTs4F1 and PTs4R1 oligonucleotide primers are indicated by arrows. (B) Locations of probes 5PHDP2, 1PHDP2, and 3PHDP2 within the 3,954-bp sequence of the T. saginata and T. solium HDP2 genomic clone. The restriction enzyme sites are indicated by the lines, and the probes (5PHDP2, 1PHDP2, and 3PHDP2) used in Southern blots assays are indicated by wider lines below the HDP2 DNA sequence. The locations of the PTs7S35F1, PTs7S35F2, and PTs7S35R1 oligonucleotide primers are indicated by arrows.

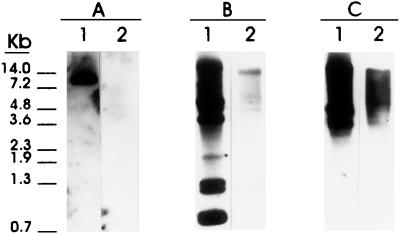

FIG. 7.

Demonstration of a unique T. saginata sequence (fragment 5HDP2) and shared T. saginata and T. solium sequences (fragment IPHDP2 and 3PHDP2) within the T. saginata genomic sequence HDP2. Southern blotting was done with T. saginata (lanes 1) and T. solium (lanes 2) gDNAs (5 μg) cleaved with the ClaI restriction enzyme. The digested gDNAs were probed with three nonoverlapping fragments derived from the HDP2 sequence fragments: 5PHDP2 (A), IPHDP2 (B), and 3PHDP2 (C). The probes were labeled with digoxigenin.

Design of a T. saginata species-specific PCR with HDP1-based primers.

Use of conventional PCR protocols with the primers described above yielded nonspecific results, probably due to the repetitive nature of the sequences and the high degree of complementarity between the forward and reverse primers (see HDP1 and HDP2 sequence analysis). After testing a number of different protocols, we empirically observed that the addition of primer PTs4R1 at 24 cycles after the initial addition of primer PTs4F1 greatly improved the specificity of the PCR, yielding a characteristic ladder pattern of 10 to 11 bands, with an approximately 50-bp size difference between them. The specificity of the amplifications was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization with the internal primer PTs4I1 (5′-ATACTACCAAATCGCAT-3′) (data not shown). We suggest that the highly repetitive nature of the HDP1 sequence is responsible for the observed sensitivity, despite the expected reduction in amplification due to the late addition of one of the primers.

The potential diagnostic properties of this modified PCR protocol were evaluated with purified gDNAs from T. saginata, T. solium, and other related cestodes. With amounts of T. saginata and T. solium DNA in the 10- to 40-ng range, the ladder amplification was observed only with T. saginata DNA (Fig. 8). Similarly, with 10 ng of DNA, amplification was positive for T. saginata but negative for T. solium, T. taeniformis, E. granulossus, human, and bovine DNAs (Fig. 9).

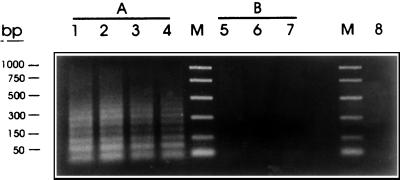

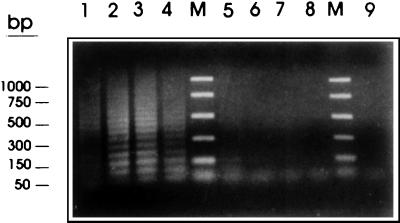

FIG. 8.

Specificity of the PCR assay with HDP1-based primers and restricted T. saginata DNA. Samples of genomic DNA from T. saginata (A) in quantities of 40 ng (lane 1), 30 ng (lane 2), 20 ng (lane 3), and 10 ng (lane 4) and from T. solium (B) in quantities of 40 ng (lane 5), 30 ng (lane 6), and 20 ng (lane 7) were amplified with the PTs4F1 and PTs4R1 primers. A negative non-DNA containing-control was also included (lane 8). The reactions were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. The amplification products were fractionated on a 2% agarose gel and were stained with ethidium bromide. Promega PCR molecular markers were used (lanes M).

FIG. 9.

Specificity of the PCR assay with HDP1-based primers and restricted T. saginata DNA. Samples of genomic DNA (10 ng) from T. saginata (lane 1), T. solium (lane 2), T. taeniformis B (lane 3), T. taeniformis M (lane 4), E. granulosus (lane 5), a calf (lane 6), and a human (lane 7) were amplified with the PTs4F1 and PTs4R1 primers as described in Materials and Methods. A negative control without DNA was also included (lane 8). The amplification products were fractionated on a 2% agarose gel and were stained with ethidium bromide. Promega PCR molecular markers were used (lane M).

Finally, the sensitivity of the PCR with HDP1-based primers was determined with decreasing quantities of T. saginata gDNA as templates (Fig. 10). The PCR could detect 10 pg of T. saginata DNA and yielded the characteristic ladder pattern, but a partial amplification could be observed even with as little as 1 pg of T. saginata DNA.

FIG. 10.

Sensitivity of PCR amplification with HDP1-based primers. Samples of genomic DNA of T. saginata, with input quantities of 10 ng (lane 1), 1 ng (lane 2), 100 pg (lane 3), 10 pg (lane 4), 1 pg (lane 5), 100 fg (lane 6), 10 fg (lane 7), and 1 fg (lane 8) were amplified with the PTs4F1 and PTs4R1 primers for the PCR with HDP1-based primers. A negative control without DNA was also included (lane 9). The reactions were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. The amplification products were fractionated on a 2% agarose gel and were stained with ethidium bromide. Promega PCR molecular markers were used (lanes M).

Design of a T. saginata- and T. solium-specific multiplex PCR with HDP2-based primers.

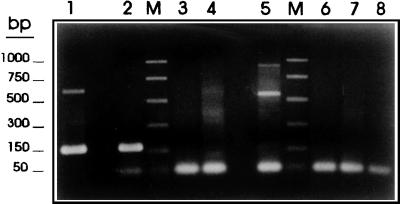

The HDP2-based primers PTs7S35F1, PTs7S35F2, and PTs7S35R1 were used to establish a T. saginata- and T. solium-specific multiplex PCR. The clearest results were obtained at an annealing temperature of 56.5°C (data not shown). With 1 ng of gDNA from T. saginata, T. solium, T. taeniformis, E. granulossus, a human, and a calf, T. saginata, T. solium, and E. granulossus gDNAs yielded positive but species-specific patterns for each of the three parasites (Fig. 11): two bands (of 600 and 170 bp) with T. saginata, one band (of 170 bp) with T. solium, and two bands (of 900 and 550) with E. granulosus. These data demonstrated the T. saginata species specificity of the PTs7S35F1-PTs7S35R1 primer combination on the 600-bp target sequence, as well as the T. saginata and T. solium specificity of the PTs7S35F2-PTs7S35R1 primer combination on the 150-bp target sequence. Finally, the sensitivity of the multiplex PCR with HDP2-based primers was shown to be 10 pg of DNA when T. saginata, T. solium, and E. granulossus gDNAs were used as templates (data not shown).

FIG. 11.

Differential detection of T. saginata, T. solium, and E. granulossus by multiplex PCR. Samples of genomic DNA (1 ng) from T. saginata (lane 1), T. solium (lane 2), T. taeniformis B (lane 3), T. taeniformis M (lane 4), E. granulosus (lane 5), a calf (lane 6), and a human (lane 7) were amplified by the multiplex PCR based on the PTs7S35F1, PTs7S35F2, and PTs7S35R1 primers derived from the T. saginata genomic sequence HDP2. A negative control without DNA was also included (lane 8). The reactions were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. The amplification products were fractionated on a 2% agarose gel and were stained with ethidium bromide. Promega PCR molecular markers were used (lanes M).

DISCUSSION

This paper describes the design and development of two PCR tests for the specific and sensitive detection of T. solium, T. saginata, and E. granulosus. One PCR specific for T. saginata detection uses primers based on the sequence of the published HDP1 T. saginata DNA fragment (19). The other is a multiplex PCR with primers derived from the sequence of another T. saginata DNA sequence, HDP2 (19), and which specifically amplified T. saginata, T. solium, and E. granulosus DNAs. The genomic characteristics of each probe, their performance in the PCR tests, and their potential applications are discussed.

The DNA sequences of HDP1 and HDP2 consisted of two entirely distinct sequences of 1,272 and 3,954 bp, respectively. Stop codons were present at the beginning of each potential reading frame (data not shown), and thus, there were no significant open reading frames that coded for proteins. No similarities were found between the HDP1 and HDP2 sequences and any other sequence included in the EMBL and GenBank databases. The HDP1 fragment was composed of 53-bp monomers tandemly repeated 24 times, with a 55% A+T content and with direct and inverse internal repeats in each monomer. An evaluation of the genomic organization by Southern blot analysis, restriction enzyme mapping, and sequencing indicated that the 53-bp monomers were arranged in an estimated 11,321 clustered tandem repeats along 23 kb or more of the T. saginata genome. The 53-bp monomer sequence was remarkably conserved in comparison to other repetitive sequences from parasite DNA that have been described (18, 42), with only 0.3% divergence among the 24 sequenced units and with only four base changes from the 53-bp consensus sequence. However, the degree of variation appeared to be increased at particular sites along the HDP1 sequence. For example, the 19th base of the monomer unit appeared to be a hot-spot site, and this mutation yielded a new ScaI recognition site, which in turn resulted in alteration of the consensus sequence, perhaps explaining the Southern blot pattern obtained by ScaI digestion of T. saginata DNA and HDP1 probe hybridization (Fig. 3). These observations suggested that the HDP1 sequence was satellite DNA, and indeed, the 53-bp HDP1 monomer sequence showed a high degree of similarity to satellite DNAs (22). Satellite DNA is defined as the DNA component which renatures rapidly in a eukaryotic genome, which consists of short sequences (5 to 200 bp) repeated many times in tandem in large clusters, and which is located in the heterochromatic regions of the chromosomes at both centromeric and telomeric regions (6, 20, 22). Their abundance can vary from less than 1% to more than 66% of the genome (38). Interestingly, three of the HDP1 monomeric units had the same point mutation in the same nucleotide and at the same position, suggesting that these mutations were not random variations. Possibly some mechanism analogous to similar previously described mechanisms acting on the satellite DNA was responsible (7, 18, 28, 41, 42). Although the HDP1 genomic representation of 0.4% of T. saginata was very low for satellite DNA, a similarly low percentage had also been found in Caenorhabditis elegans satellite DNA (21). In summary, therefore, we may conclude that the HDP1 sequence is satellite DNA that has repeats organized in tandem arrays, that is characterized by a small unit size and high copy number (22), and that perhaps has a structural function, as has already been suggested (4, 18, 22, 30, 33, 42). This is not the first time that highly repetitive DNAs, such as satellite DNAs, which undergo rapid evolutionary changes, have been used as species-specific probes (17, 18, 38). Indeed, the specificity of the T. saginata 1,272-bp HDP1 target sequence is exquisite, as Harrison et al. described before (19), indicating that satellite DNA is, in general, species specific (38). However, there are few published data on these repetitive elements in cestodes (5, 25, 31, 33).

The HDP2 probe with an A+T content of 45% was not a repetitive sequence. This fact and Southern blot analysis (Fig. 4) suggested that HDP2 could be intergenic spacer DNA (22). Its dual specificity for DNAs of both T. saginata and T. solium has considerable practical potential, similar to the previous employment of interspersed DNA fragments with large unit sizes and low to moderate copy numbers (10).

Taking into account the complete sequences and other characteristics of the two DNA probes (HDP1 specificity for T. saginata and HDP2 reactivity with both T. saginata and T. solium), primer sets were designed for the differential detection of these two parasites by PCR. Thus, a T. saginata species-specific PCR with primers based on the sequence of the HDP1 probe (19) and a multiplex PCR with primers based on the sequence of the HDP2 probe, which specifically amplified T. saginata, T. solium, and E. granulossus DNA sequences, were developed.

The oligonucleotides designed from HDP1 provided a species-specific PCR amplification of T. saginata gDNA with a characteristic ladder of 10 or 11 bands and with a difference between the bands of about 50 bp. This pattern suggested that the oligonucleotide primers hybridize to all the complementary sequences along the tandemly arranged repetitions in the HDP1 sequence. The PCR detected down to 10 pg of T. saginata gDNA, and this high degree of sensitivity could be attributed to the repetitive nature of the HDP1 sequence, as well as to the amplification power of the PCR. By calculating that one Taenia sp. egg contains approximately 8 pg of gDNA (32), the PCR should be able to detect the gDNA from one T. saginata egg. Thus, the PCR with HDP1-based primers offers the possibility of a sensitive, rapid, and specific method for the reliable identification of T. saginata in the absence of a signal from T. solium and other taeniids.

In order to achieve, in addition, a positive identification of T. solium by PCR, a multiplex PCR was established by taking advantage of both sequence specificity and the peculiar specificity of the HDP2 probe. The test was based on T. saginata genomic clone HDP2 and, moreover, distinguished T. saginata, T. solium, and E. granulosus through different amplification patterns, while it was negative for other taeniids. Specifically, these data demonstrated the T. saginata species specificity of the PTs7S35F1-PTs7S35R1 primer set and the T. saginata and T. solium specificity of the PTs7S35F2-PTs7S35R1 primer set. The exact nature of the specific products amplified from T. saginata, T. solium, and E. granulosus by primers PTs7S35F1, PTs7S35F2, and PTs7S35R1 remains to be determined and may shed some light on the evolution of these organisms. The sensitivity of the multiplex PCR was excellent, detecting as little as 10 pg of the taeniid gDNAs.

Both the PCR with HDP1-based primers and the multiplex PCR with HDP2-based primers are now ready for application to the differential detection of both T. saginata and T. solium in humans and are clearly more efficient, specific, and sensitive than previously reported Southern hybridization techniques (5, 13, 19).

The most immediate priority is to distinguish T. saginata and T. solium infections in the clinical situation in order to rapidly identify human carriers of T. solium. Use of the PCR assays for the positive identification of the parasites in dubious cysts, lesions, or cyst residues in domestic animals at the slaughterhouse would aid in the appropriate treatment of the carcasses and in the control of these parasites in domestic livestock. In the future, the assays described in this paper could have a major impact on epidemiological studies through the identification of tapeworm eggs in the environment, i.e., in water supplies or on contaminated pasture, in addition to identifying human tapeworm carriers. Importantly, in recent preliminary experiments we have been able to efficiently extract DNA from taeniid eggs. Finally, the sequences and primers used in these studies might also be used to determine the possible occurrence of strains or geographical isolates of these parasites, perhaps via restriction enzyme polymorphism analyses of the amplified products as has been reported by McManus and colleagues (3, 32).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. M. Rubio for technical help in the design of the PCR with HDP1-based primers and L. Benítez and E. Rodríguez for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from UE-INCO (grant DCIC 18CT950002), FISS (grant 97/0141), and MEC/British Council (grant HB96-43).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allan J C, Avila G, Garcia Noval J, Flisser A, Graig P S. Immunodiagonosis of taeniasis by coproantigen detection. Parasitology. 1990;101:473–477. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000060686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker R H, Jr, Suebsaeng L, Rooney W, Alecrim G C, Dourado H V, Wirth D F. Specific DNA probe for the diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Science. 1986;231:1434–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.3513309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowles J, McManus D P. Genetic characterization of the Asian Taenia, a newly described taeniid cestode of humans. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:33–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callaghan M J, Beh K J. A tandemly repetitive DNA sequence is present at diverse locations in the genome of Ostertagia circumcincta. Gene. 1996;174:273–279. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman A, Vallejo V, Mossie K G, Ortiz D, Agabian N, Flisser A. Isolation and characterization of species-specific DNA probes from Taenia solium and Taenia saginata and their use in an egg detection assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1283–1288. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1283-1288.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly B, Ingram L J, Smith D F. Trichinella spiralis: cloning and characterization of two repetitive DNA sequences. Exp Parasitol. 1995;80:488–498. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis C A, Wyatt G R. Distribution and sequence of an abundant satellite DNA in the beetle Tenebrio molitor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5579–5586. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.14.5579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deplazes P, Eckert J, Pawlowski Z, Machowska L, Gottstein B. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnostic detection of Taenia saginata coproantigens in humans. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:391–396. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90302-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devereux J R, Haeberli P L, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programmes for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dissanayake S, Piessens W F. Cloning and characterization of a Wuchereria bancrofti specific DNA sequence. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;39:147–150. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90017-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erttmann K D, Unnasch T R, Greene B M, Albiez E J, Boateng J, Denke A M, Ferraroni J J, Karam M, Schulz-Key H, Williams P N. A DNA sequence specific for forest form Onchocerca volvulus. Nature (London) 1987;327:415–417. doi: 10.1038/327415a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flisser A. Neurocysticercosis in Mexico. Parasitol Today. 1988;4:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(88)90187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flisser A, Reid A, Garcia Zepeda E, McManus D P. Specific detection of Taenia saginata eggs by DNA hybridization. Lancet. 1988;ii:1429–1430. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90626-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez A, Prediger E, Huecas M E, Nogueira N, Lizardi P M. Minichrosomal repetitive DNA in Trypanosoma cruzi. Its use in a high-sensitivity parasite detection assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3356–3360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottstein B, Mowatt R. Sequencing and characterization of an Echinococcus multilocularis DNA probe and its use in the polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;44:183–194. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90004-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottstein B, Deplaze P, Tanner I, Skaggs J S. Diagnostic identification of Taenia saginata with the polymerase chain reaction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:248–249. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90042-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grenier E, Laumond C, Abad P. Characterization of a species-specific satellite DNA from the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;69:93–100. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00197-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grenier E, Laumond C, Abad P. Molecular characterization of two species-specific tandemly repeated DNAs from entomopathogenic nematodes Steinernema and Heterorhabditis (Nematoda: Rahabditida) Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;83:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02747-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison L J S, Delgado J, Parkhouse R M E. Differential diagnosis of Taenia saginata and Taenia solium with DNA probes. Parasitology. 1990;100:459–461. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000078768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jelinek W R. Repetitive sequences in eukaryotic DNA and their expression. Ann Rev Biochem. 1982;51:813–844. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.51.070182.004121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.La Volpe A, Ciaramella M, Bazzicalupo P. Structure, evolution and properties of a novel repetitive DNA family in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:8213–8231. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.17.8213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewin B. Genes VI. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machnicka B, Dziemian E, Zwierz C. Factors conditioning detection of Taenia saginata antigens in faeces. Appl Parasitol. 1996;37:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Machnicka B, Dziemian E, Zwierz C. Detection of Taenia saginata antigens in faeces by ELISA. Appl Parasitol. 1996;37:106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marin M, Garat B, Petterson U, Ehrlich R. Isolation and characterization of a middle repetitive DNA element from Echinococcus granulosus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;59:335–338. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90233-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McManus D P, Garcia-Zepeda E, Reid A, Rishi A K, Flisser A. Human cysticercosis and taeniasis: molecular approaches for specific diagnosis and parasite identification. Acta Leiden. 1989;57:81–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meredith S E O, Landon G, Gbakima A A, Zimmerman P A, Unnasch T R. Onchocerca volvulus: application of the polymerase chain reaction to identification and strain differentiation of the parasite. Exp Parasitol. 1991;73:335–344. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(91)90105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piotte C, Catagnone-Sereno P, Bongiovanni M, Dalmasso A, Abad P. Cloning and characterization of two satellite DNAs in the low-C-value genome of the nematode Meloidogyne spp. Gene. 1994;138:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Proctor B M. Identification of tapeworms. South Afr Med J. 1972;46:234–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radic M Z, Lundgreen K, Hamkalo B. Curvature of mouse satellite DNA and condensation of heterochromatin. Cell. 1987;50:1101–1108. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rishi A K, McManus D P. Genomic cloning of human Echinococcus granulosus DNA: isolation of recombinant plasmids and their use as genetic markers in strain characterization. Parasitology. 1987;94:369–383. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000054020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rishi A K, McManus D P. Molecular cloning of Taenia solium genomic DNA and characterization of taeniid cestodes by DNA analysis. Parasitology. 1988;97:161–176. doi: 10.1017/s003118200006683x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenzvit M C, Canova S G, Kamenetzky L, Ledesma B A, Guarnera E A. Echinococcus granulosus: cloning and characterization of a tandemly repeated DNA element. Exp Parasitol. 1997;87:65–68. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samuelson J, Acuna-Soto R, Reed S, Biagi F, Wirth D. DNA hybridization probe for clinical diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:671–676. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.671-676.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schantz P M. Taenia solium cysticercosis/taeniasis is a potentially eradicable disease: developing a strategy for action and obstacles to overcome. In: García H H, Martínez M, editors. Teniasis/cisticercosis por T. solium. Lima, Peru: I.C.N.; 1996. pp. 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah J S, Karam M, Piessens W F, Wirth D. Characterization of an Onchocerca-specific DNA clone from Onchocerca volvulus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;37:376–384. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.37.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skinner D M. Satellite DNAs. BioScience. 1977;27:790–796. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soulsby E J L. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. 7th ed. London: Baillihere and Tyndall; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tares S, Cornuet J M, Abad P. Characterization of an unusually conserved Alu I highly reiterated DNA sequence family from the honeybee, Apis mellifera. Genetics. 1993;134:1195–1204. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.4.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tarès S, Lemontey J M, de Guiran G, Abad P. Cloning and characterization of a highly conserved satellite DNA sequence specific for the phytoparasitic nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Gene. 1993;129:269–273. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90278-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkins P A, Allan J C, Verastegui M, Acosta M, Eason A G, Garcia H H, Gonzalez A E, Gilman R H, Tsang V C W. Development of a serologic assay to detect Taenia solium taeniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:199–204. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wirth D F, Pratt D M. Rapid identification of Leishmania species by especific hybridization of kinetoplast DNA in cutaneous lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6999–7003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.22.6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]