Abstract

Importance

Skin cancer, in particular squamous cell carcinoma, is the most frequent malignancy among solid organ transplant recipients with a higher incidence compared to the general population.

Objective

To determine the skin cancer incidence in organ transplant recipients in Switzerland and to assess the impact of immunosuppressants and other risk factors.

Design

Prospective cohort study of solid organ transplant recipients in Switzerland enrolled in the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study from 2008 to 2013.

Participants

2,192 solid organ transplant recipients.

Materials and Methods

Occurrence of first and subsequent squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, melanoma and other skin cancers after transplantation extracted from the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study database and validated by medical record review. Incidence rates were calculated for skin cancer overall and subgroups. The effect of risk factors on the occurrence of first skin cancer and recurrent skin cancer was calculated by the Cox proportional hazard model.

Results

In 2,192 organ transplant recipients, 136 (6.2%) developed 335 cases of skin cancer during a median follow-up of 32.4 months, with squamous cell carcinoma as the most frequent one. 79.4% of skin cancer patients were male. Risk factors for first and recurrent skin cancer were age at transplantation, male sex, skin cancer before transplantation and previous transplantation. For a first skin cancer, the number of immunosuppressive drugs was a risk factor as well.

Conclusions and Relevance

Skin cancer following solid organ transplantation in Switzerland is greatly increased with risk factors: age at transplantation, male sex, skin cancer before transplantation, previous transplantation and number of immunosuppressive drugs.

Keywords: Skin cancer, Squamous cell carcinoma, Organ transplant recipient, Organ transplantation, Basal cell carcinoma, Melanoma, Keratinocyte carcinoma

Introduction

Skin cancer represents over one third of all cancer cases in Switzerland [1]. Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer overall in Switzerland and most other countries [2, 3]. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second-most frequent keratinocyte cancer following BCC [4]. Most keratinocyte carcinoma in the general population is indolent with a low mortality rate but causes relevant morbidity [2, 4]. In the setting of immunosuppression such as in organ transplant recipients (OTR), the incidence of keratinocyte cancers, in particular SCC, increases 65- to 250-fold compared to the general population, greatly impacting morbidity and mortality [2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11].

Due to improvements in clinical management, advances in transplantation medicine and immunosuppressive medication, outcomes and survival after solid organ transplantation have improved over the last few years. This, however, leads to an increased incidence of cancers after solid organ transplantation [12, 13]. The Swiss Transplant Cohort Study (STCS) is a prospective cohort study screening all candidates for solid organ transplantation since 2008 and finally enrolling them at transplantation [14]. The enrolment rate exceeds 95% and thus reflects well the transplant recipient population in Switzerland [15]. Skin cancers are prospectively captured in the 4 categories of SCC, BCC, melanoma and other skin cancers and allow the association of these skin cancer events with a large data pool on the individuals affected [14].

The present study aims to report the incidence of skin cancer overall and by cancer type within the STCS in the years 2008–2013. We present descriptive statistics for these skin cancers and report associated risk factors based on the high granularity of data captured in the STCS.

Materials and Methods

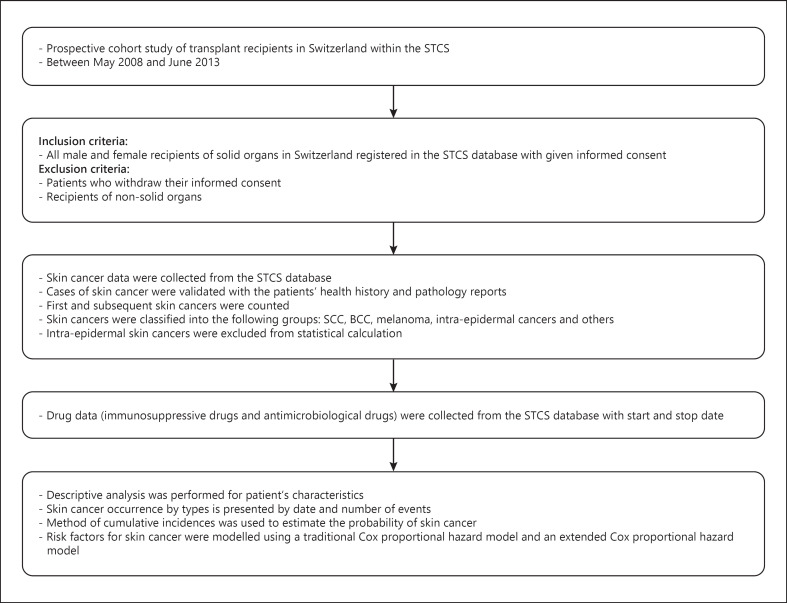

For further details, see the online supplementary material (see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000510685) (Fig. 1) [14, 16, 17, 18].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of Materials and Methods. STCS, Swiss Transplant Cohort Study; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; BCC, basal cell carcinoma.

Results

Between May 2008 and June 2013, 2,192 patients with solid organ transplantation were included in our report. The median follow-up time was 32.4 months. Most of the patients (56.7%) were kidney transplant recipients, followed by liver, lung, heart, combined (i.e., kidney and pancreas) and other (i.e., pancreas, small bowel) transplant recipients. The median age at transplantation was 53.3 years, while 64.1% of the OTR were male. During follow-up 98% of the patients received glucocorticoids at least once, 10.3% azathioprine (AZA), 95.8% mycophenolate mofetil, 98.6% a calcineurin inhibitor and 14.9% a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor. 317 (14.5%) OTR were put on quinolones and 20 (0.9%) on voriconazole during our follow-up time. Full details are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Transplanted organ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kidney | liver | lung | heart | combined | other | all organs | |

| Patients, n (%) | 1,243 (56.7) | 443 (20.2) | 218 (9.9) | 162 (7.4) | 93 (4.3) | 33 (1.5) | 2,192 (100.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 817 (65.7) | 288 (65) | 108 (49.5) | 121 (74.7) | 54 (58.1) | 17 (51.5) | 1,405 (64.1) |

| Median age at transplantation (IQR), years | 53.4 (41.4–62.8) | 54 (43.5–61.1) | 55 (38.7–60.6) | 51.8 (38.2–59.8) | 44.4 (36.9–52.3) | 51.3 (42.7–56.9) | 53.2 (40.8–61.6) |

| Median follow-up time (IQR), months | 36 (19.6–50.6) | 28 (13.9–47) | 26.7 (13.4–40.4) | 27.4 (11.5–45.1) | 32.4 (17.9–46.8) | 42.2 (18.4–58.8) | 32.4 (17.3–49) |

| Re-/second transplantation, n (%) | 21 (1.7) | 27 (6.1) | 6 (2.8) | 1 (0.6) | 9 (9.7) | 6 (18.2) | 70 (3.2) |

| Previous transplantation, n (%) | 210 (16.9) | 21 (4.7) | 8 (3.7) | 1 (0.6) | 12 (12.9) | 23 (69.7) | 275 (12.5) |

| Previous skin cancer, n (%) | 60 (4.8) | 8 (1.8) | 9 (4.1) | 3 (1.9) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (15.2) | 86 (3.9) |

| Previous skin cancer + previous transplantation, n (%) | |||||||

| Neither | 1,007 (81) | 415 (93.7) | 204 (93.6) | 158 (97.5) | 80 (86) | 10 (30.3) | 1,874 (85.5) |

| Skin cancer, no previous transplantation | 26 (2.1) | 7 (1.6) | 6 (2.8) | 3 (1.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 43 (2) |

| Previous transplantation, no skin cancer | 176 (14.2) | 20 (4.5) | 5 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) | 12 (12.9) | 18 (54.5) | 232 (10.6) |

| Both | 34 (2.7) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (15.2) | 43 (2) |

| Death, n (%) | 78 (6.3) | 70 (15.8) | 53 (24.3) | 32 (19.8) | 8 (8.6) | 4 (12.1) | 245 (11.2) |

| Drop-out, n (%) | 8 (0.6) | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (6.1) | 16 (0.7) |

| Immunosuppressive medication, n (%) | |||||||

| Glucocorticoid | 1,242 (99.9) | 416 (93.9) | 217 (99.5) | 157 (96.9) | 93 (100.0) | 23 (69.7) | 2,148 (98) |

| AZA | 124 (10.0) | 23 (5.2) | 9 (4.1) | 50 (30.9) | 12 (12.9) | 7 (21.2) | 225 (10.3) |

| MMF/EC-MPA | 1,234 (99.3) | 382 (86.2) | 216 (99.1) | 148 (91.4) | 90 (96.8) | 29 (87.9) | 2,099 (95.8) |

| CNI | 1,235 (99.4) | 437 (98.6) | 217 (99.5) | 150 (92.6) | 92 (98.9) | 31 (93.9) | 2,162 (98.6) |

| mTOR inhibitor | 108 (8.7) | 131 (29.6) | 11 (5.0) | 55 (34.0) | 9 (9.7) | 13 (39.4) | 327 (14.9) |

| Infectious prophylaxis, n (%) | |||||||

| Quinolone | 213 (17.1) | 41 (9.3) | 50 (22.9) | 6 (3.7) | 7 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 317 (14.5) |

| Voriconazole | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.9) | 16 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (0.9) |

Transplanted organs were divided into kidney, liver, lung, heart, combined and other transplantation. Combined organ transplantations were transplantations of more than 1 organ at the same time and included 57 kidney and pancreas, 20 kidney and liver, 8 kidney and islet cells, 4 kidney and heart, 2 pancreas and small bowel transplantations, 1 liver and lung and 1 kidney, liver and islet cell transplantation. 21 double kidney transplantations were counted as kidney transplantation. Other transplanted organs included 1 small bowel, 9 pancreas and 23 islet cell transplantations. Retransplantation comprises second transplantations of the same organ during follow-up, while second transplantation stands for transplantation of a different organ during follow-up. Previous skin cancer includes patients with at least one skin cancer incident before inclusion into the STCS. Previous transplantation includes patients with previous transplants before inclusion into the STCS. Graft loss, death and drop-out comprise the whole follow-up time. n, number; IQR, interquartile range; AZA, azathioprine; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; EC-MPA, enteric-coated mycophenolate acid; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; mTOR inhibitor, mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitor.

As shown in Table 2 in detail, a total of 136 patients developed 335 cases of skin cancer during follow-up. 79 patients developed SCC, 77 BCC, 6 melanoma and 5 other skin malignancies (dermal sarcoma, sarcoma not otherwise specified, sebaceous gland carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma, atypically lymphocytic proliferation T-cell type). The cumulative incidence reached 6.2% for any skin cancer, 3.6% for SCC and 3.5% for BCC. 79.4% of the OTR with skin malignancy were male. 186 of these 335 skin cancer cases were SCC, 137 BCC, 7 melanoma and 5 other skin malignancies. This results in an SCC-to-BCC ratio of 1.4:1. The median time to first skin cancer after transplantation was 14 months (Table 3).

Table 2.

Skin cancer cumulative incidence

| Transplanted organ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kidney | liver | lung | heart | combined | other | all organs | |

| Any skin cancer | 92 (7.4) | 15 (3.4) | 14 (6.4) | 6 (3.7) | 3 (3.2) | 6 (18.2) | 136 (6.2) |

| Male | 76 (82.6) | 11 (73.3) | 9 (64.3) | 5 (83.3) | 2 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) | 108 (79.4) |

| SCC | 52 (4.2) | 9 (2.0) | 12 (5.5) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (9.1) | 79 (3.6) |

| Male | 42 (80.8) | 8 (88.9) | 8 (66.7) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (100.0) | 2 (66.7) | 62 (78.5) |

| BCC | 56 (4.5) | 9 (2.0) | 2 (0.9) | 5 (3.0) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (9.1) | 77 (3.5) |

| Male | 49 (87.5) | 7 (77.8) | 1 (50.0) | 5 (100.0) | 1 (50.0) | 3 (100.0) | 66 (85.7) |

| Melanoma | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.3) |

| Male | 3 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (100.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.2) |

| Male | 1 (100.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (80.0) |

| Median time to first skin cancer | |||||||

| (IQR), months | 13.9 (8.4–22.7) | 14.2 (8.9–22) | 15.6 (6.5–19.5) | 15.2 (12.5–22.5) | 11.9 (7.4–17.3) | 18.2 (3.9–36.8) | 14 (8.4–22.7) |

Skin cancer cases were divided into 4 groups: squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), basal cell carcinoma (BCC), melanoma and other. Other includes dermal sarcoma, sarcoma not otherwise specified, sebaceous gland carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma and atypical lymphocytic proliferation of T-cell type. The number and percentage of all skin cancers and the different groups of skin cancer were calculated, as well as the number and percentage of male patients with skin cancer. Combined organ transplantations were transplantations of more than one organ at the same time and included 57 kidney and pancreas, 20 kidney and liver, 8 kidney and islet cells, 4 kidney and heart, 2 pancreas and small bowel transplantations, 1 liver and lung and 1 kidney, liver and islet cell transplantation. 21 double kidney transplantations were counted as kidney transplantation. Other transplanted organs included 1 small bowel, 9 pancreas and 23 islet cells transplantations. IQR, interquartile range.

Table 3.

Skin cancer events

| Transplanted organ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kidney | liver | lung | heart | combined | other | all organs | |

| Total number of skin cancer events, n (%) | 233 (69.5) | 46 (13.7) | 32 (9.6) | 7 (2.1) | 4 (1.2) | 13 (3.9) | 335 (100.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 211 (90.6) | 42 (91.3) | 27 (84.4) | 6 (85.7) | 3 (75.0) | 12 (92.3) | 301 (89.9) |

| Total number of SCC events, n (%) | 128 (68.8) | 23 (12.3) | 21 (11.3) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 10 (5.4) | 186 (100.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 116 (90.6) | 22 (95.7) | 17 (81.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100.0) | 9 (90.0) | 167 (89.8) |

| Total number of BCC events, n (%) | 101 (73.7) | 19 (l3.9) | 7 (5.1) | 5 (3.6) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2.2) | 137 (100.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 91 (90.1) | 17 (89.5) | 6 (85.7) | 5 (100.0) | 1 (50.0) | 3 (100.0) | 123 (89.8) |

| Total number of melanoma events, n (%) | 3 (42.8) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 3 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| Total number of other events, n (%) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (100.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (80.0) |

Total number of skin cancer events during follow-up by transplanted organ and different skin cancer types. n, number; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; BCC, basal cell number.

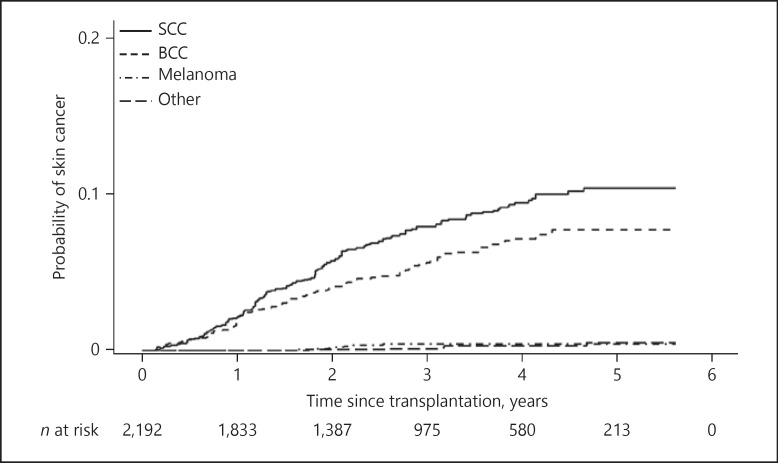

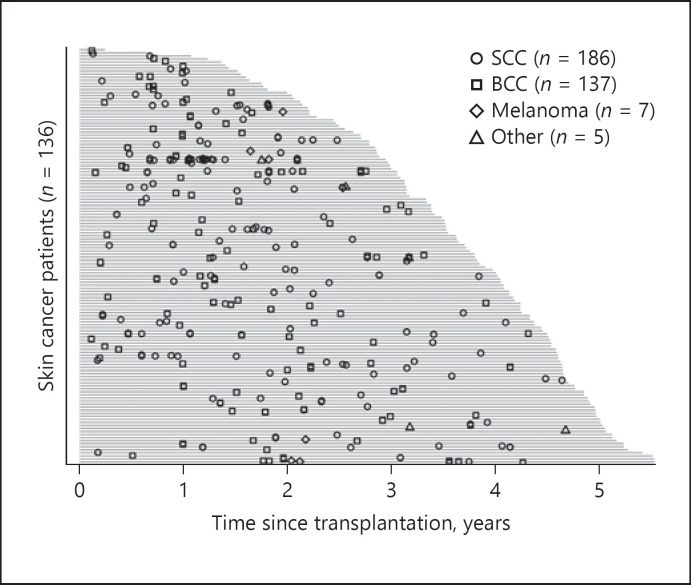

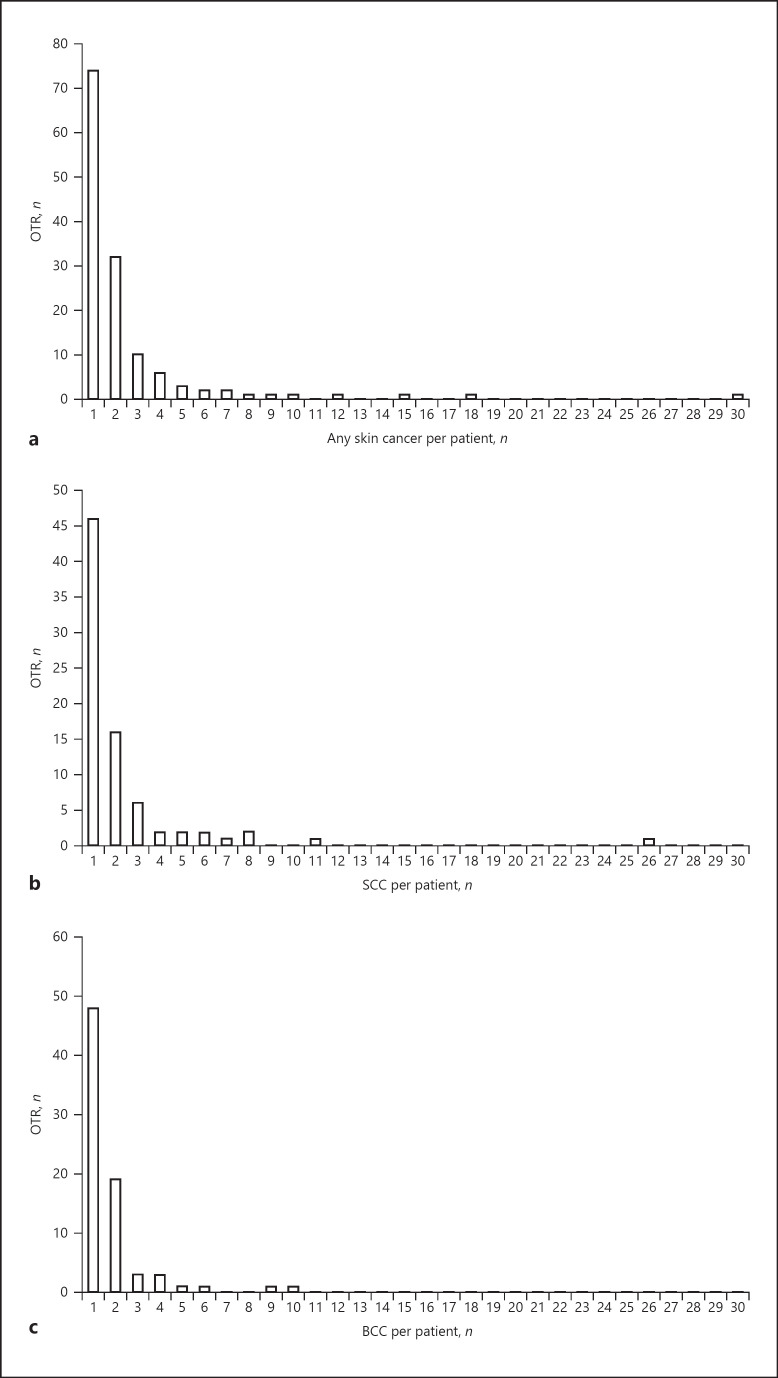

Figure 2 shows the probability of incident skin cancer during follow-up. With time after transplantation, the probability of SCC and BCC increases while the number of patients at risk decreases over time. Figure 3 shows the distribution of skin cancer after transplantation itemized for each skin cancer type. Each OTR with skin cancer is represented by a horizontal line. In Figure 4a–c skin cancer cases per patient, classified into any skin cancer, SCC and BCC, are illustrated. The majority of patients suffered 1 or 2 skin cancer cases, but there is a noticeable minority with a large number of tumours, especially SCC.

Fig. 2.

Probability of incident skin cancer. Probability of incident skin cancer is displayed for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), basal cell carcinoma (BCC), melanoma and other cancers over time and over number of patients at risk. “Other” includes dermal sarcoma, sarcoma not otherwise specified, sebaceous gland carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma and atypical lymphocytic proliferation of T-cell type.

Fig. 3.

Skin cancer events per patient after transplantation. Cases of skin cancer are displayed for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by open circles, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) by open squares, melanoma by open rhomboids and other cancers by open triangles over time. Grey bars represent the follow-up for each patient affected by skin cancer. “Other” includes dermal sarcoma, sarcoma not otherwise specified, sebaceous gland carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma and atypical lymphocytic proliferation of T-cell type.

Fig. 4.

a Number of skin cancers per patient. OTR, organ transplant recipients. The y axis shows the number of patients in relation to the number of skin cancers on the x axis. b Number of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) per patient. The y axis shows the number of patients in relation to the number of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the x axis. c Number of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) per patient. The y axis shows the number of patients in relation to the number of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) on the x axis.

Multivariate analysis showed age at transplantation, male sex, skin cancer before inclusion into the STCS, previous transplantation and number of immunosuppressive drugs as risk factors for the development of a first skin cancer overall (Table 4). For recurrent skin cancer, risk factors were age at transplantation, male sex, skin cancer before transplantation and also previous transplantation during the first 2 years after transplantation (Table 5). The number of immunosuppressive drugs was not significant for the development of recurrent skin cancer overall, neither in recurrent SCC nor BCC (Tables 6, 7).

Table 4.

Risk factors for first skin cancer overall

| Risk factor | Reference | HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplantation | − | 1.059 (1.04–1.079) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | female sex | 2.105 (1.36–3.259) | 0.001 |

| Previous skin cancer | no previous skin cancer | 5.3 (3.446–8.152) | <0.001 |

| Previous transplantation | no previous transplantation | 2.211 (1.505–3.248) | <0.001 |

| Number of immunosuppressive drugs | − | 1.332 (1.022–1.736) | 0.034 |

The risk factors for first skin cancer were calculated using multivariate analysis. −, lack of reference; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; see also Figure 3, legend text.

Table 5.

Risk factors for recurrent skin cancer

| Risk factor | Reference | HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplantation (<2 years of transplant) | − | 1.036 (1.008–1.064) | 0.01 |

| Age at transplantation (>2 years of transplant) | − | 1.061 (1.029–1.094) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | female sex | 3.535 (2.234–5.595) | <0.001 |

| Previous skin cancer (<2 years of transplant) | no previous skin cancer | 9.413 (5.589–15.854) | <0.001 |

| Previous skin cancer (>2 years of transplant) | no previous skin cancer | 3.993 (1.565–10.189) | 0.004 |

| Previous transplantation (<2 years of transplant) | no previous transplantation | 2.576 (1.657–4.003) | <0.001 |

| Previous transplantation (>2 years of transplant) | no previous transplantation | 1.634 (0.732–3.648) | 0.231 |

| Number of immunosuppressive drugs | − | 1.160 (0.782–1.72) | 0.46 |

The risk factors for recurrent skin cancer were calculated using multivariate analysis. −, lack of reference; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 6.

Risk factors for recurrent SCC

| Risk factor | Reference | HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplantation (<2 years of transplant) | − | 1.019 (0.985–1.054) | 0.272 |

| Age at transplantation (>2 years of transplant) | − | 1.070 (1.035–1.106) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | female sex | 3.395 (1.912–6.028) | <0.001 |

| Previous skin cancer (<2 years of transplant) | no previous skin cancer | 14.523 (7.034–29.985) | <0.001 |

| Previous skin cancer (>2 years of transplant) | no previous skin cancer | 3.466 (1.521–7.899) | 0.003 |

| Previous transplantation (<2 years of transplant) | no previous transplantation | 3.747 (2.08–6.751) | <0.001 |

| Previous transplantation (>2 years of transplant) | no previous transplantation | 2.027 (0.962–4.271) | 0.063 |

| Number of immunosuppressive drugs | − | 1.174 (0.684–2.012) | 0.561 |

The risk factors for recurrent squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) were calculated using multivariate analysis. −, lack of reference; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 7.

Risk factors for recurrent BCC

| Risk factor | Reference | HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplantation (<2 years of transplant) | − | 1.060 (1.028–1.093) | <0.001 |

| Age at transplantation (>2 years of transplant) | − | 1.059 (1.014–1.106) | 0.01 |

| Male sex | female sex | 3.605 (1.831–7.098) | <0.001 |

| Previous skin cancer (<2 years of transplant) | no previous skin cancer | 5.315 (3.22–8.776) | <0.001 |

| Previous skin cancer (>2 years of transplant) | no previous skin cancer | 5.009 (1.356–18.506) | 0.016 |

| Previous transplantation (<2 years of transplant) | no previous transplantation | 1.437 (0.895–2.308) | 0.133 |

| Previous transplantation (>2 years of transplant) | no previous transplantation | 1.399 (0.42–4.66) | 0.584 |

| Number of immunosuppressive drugs | − | 1.148 (0.726–1.813) | 0.555 |

The risk factors for recurrent basal cell carcinoma (BCC) were calculated using multivariate analysis. −, lack of reference; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our study reports the skin cancer incidence after transplantation of solid organs within the STCS. Our demographic results are comparable with previous studies. The median age in our study was slightly higher than in other studies, where age ranged between 41 and 53 years at transplantation [19, 20, 21, 22]. As in our study, most OTR included in studies from the USA, Australia, Sweden, Norway and Denmark were male [8, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. The majority of our patients received a kidney transplant, followed by liver transplantation. Compared with our data, most studies showed a higher proportion of kidney transplant recipients around 76% [19, 20, 21]. Only one study from the USA showed a lower proportion of kidney transplant recipients of 48% [22]. Median follow-up and number of our enrolled patients were less than in similar studies, which included 5,279–10,649 patients with a median follow-up from 4 to 8 years [19, 20, 21, 22]. With an enrolment rate of 95% of transplant recipients in Switzerland, our study population largely resembles the ones reported in other countries and is highly representative of the transplant population in Switzerland [15].

Garrett et al. [22] showed an incidence rate of 8% for posttransplantation skin cancer in the USA. Australian kidney transplant recipients showed skin cancer incidences of 7, 25 and 79% after 1, 5 and 20 years of follow-up, respectively [8]. In Sweden the cumulative incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) after transplantation reached 6.7% after 10 years and 20.4% after 20 years of follow-up [25]. In an Italian registry-based study of kidney and heart transplant recipients, the cumulative incidence reached 5.8 and 10.8% 5 and 10 years after transplantation, respectively [26]. A Swiss long-term study of lung transplant recipients from 1992 till 2010 showed a cumulative incidence of SCC of 16.7 and 59.9% for 5 and 15 years after transplantation, respectively [27]. Except for NMSC in Sweden and Italy, our cohort reports lower incidence rates. This might be due to the shorter follow-up in our study, as skin cancer incidence in OTR seems to increase with duration of immunosuppression [8, 9, 28, 29, 30]. Our data show an increasing probability of incident skin cancer with time after transplantation, in particular for SCC (Fig. 2).

Compared to our tumour data, several publications − including only heart and/or renal transplant recipients − showed a much higher SCC-to-BCC ratio ranging between 2 and 7:1 [6, 7, 28, 31, 32, 33, 34]. Studies including all solid transplant recipients from Israel and Denmark reported an SCC-to-BCC ratio of 1.9:1 [6] and 1:1, respectively [20], more in line with our data. Also studies from countries in southern Europe described lower SCC-to-BCC ratios of 1.1:1 in kidney transplant recipients in Portugal [35], 1.1:1 in Italian heart and 2.6:1 in Italian kidney transplant recipients [26]. For the general population in Switzerland, only the Canton of Vaud reports numbers which show the SCC-to-BCC ratio at 1:2.5 in the period between 1976 and 1992 [3]. The ratio of SCC to BCC in our present study might result from a rather short follow-up where the impact of previous sun damage before transplantation is still relatively predominant, while we expect an increase in the SCC-to-BCC ratio with a longer follow-up. Since AZA is known to increase especially the risk for SCC [36], another explanation for the lower SCC-to-BCC ratio in our study might be the low percentage of patients in our cohort receiving AZA compared to other similar cohorts, where the majority of the patient had AZA as component of their maintenance immunosuppressive therapy [7, 31, 32, 33].

Previous data showed that risk factors for NMSC after transplantation are age at transplantation, male sex, history of pretransplantation skin cancer, type of transplanted organ, high sun exposure and fair skin type [8, 9, 10, 19, 22, 26, 27, 28, 33, 37, 38]. Our study finds correspondingly age at transplantation, male sex, previous skin cancer and additionally previous transplantation as risk factors for first and recurrent skin cancer. The duration of immunosuppression correlates with the increased skin cancer risk after transplantation, while the type of immunosuppressive drug seems an important risk factor [7, 8, 10, 31, 33, 39]. Dantal et al. [40] demonstrated in 1998 that more kidney transplant recipients developed a malignant disorder on a normal-dose cyclosporine regimen compared to patients on a low-dose cyclosporine regimen. There were also more patients with multiple skin lesions in the normal-dose cyclosporine group [40]. A change in immunosuppressive regimen from calcineurin inhibitor to mTOR inhibitor induced fewer NMSC [41, 42]. AZA increases UVA photosensitivity and subsequent photodamage, potentially leading to a higher skin cancer occurrence [43, 44]. Like many other studies we could not find an association for individual drugs with skin cancer. We did, however, find that the number of any immunosuppressive drugs is associated with the risk for a first skin cancer after transplantation, but not for recurrent skin cancer after transplantation. Our limited follow-up is the most likely limiting factor in associating skin cancer risk with individual immunosuppressants, followed by the limitation of our cohort data to the dose prescribed, not the trough levels achieved in serum. Selection bias for prescribing an mTOR inhibitor in high-risk individuals might also contribute. We hope that with a longer follow-up time, our cohort study will yield data on the impact of individual immunosuppressants.

OTR with previous skin cancer showed a higher hazard ratio for skin cancer in the first 2 years after transplantation compared to the period beyond 2 years. We believe that these findings show the decreasing impact of pre-existent conditions in the course after transplantation. Previous skin cancer as a static risk factor tends to lose impact over time. Immunosuppression as dynamically increasing risk factor, however, gains impact over time, both in time after transplantation and by accumulated immunosuppressant use.

Limitations of our study are the limited number of skin cancer cases and the limited follow-up time of 36 months compared to similar studies. There is no matched control population because NMSC is not captured in the national cancer registry in Switzerland. Skin type and sun exposure, as well as serum levels of immunosuppressive drugs, were not captured in the STCS, precluding analysis of these factors for risk association.

Conclusion

In summary, our study is highly representative of the Swiss transplant recipient population. Skin cancer increases following transplantation with an important impact on morbidity and is associated with risk factors in our national cohort. Further follow-up will allow more granular dissection, for example, of individual immunosuppressants and their impact on skin cancer formation, potentially allowing immunosuppressive treatment regimes tailored to individual skin cancer risks in our transplant recipients.

Key Message

The incidence of skin cancer after organ transplantation is increased. We found some important risk factors.

Statement of Ethics

All patients included in our report agreed to inclusion into the STCS for further use of their medical and personal data. This research project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zurich, Switzerland (KEK-ZH-Nr. 2014-0276).

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This observational study was not financially supported by external funding sources. This study has been conducted in the framework of the STCS, supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Swiss University Hospitals (G15) and transplant centres.

Author Contributions

N.A.S. was involved in concept, design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the article. G.F.L.H. contributed to concept, design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the article. S.S. performed data analysis and statistics. A.W.A., A.C., M.D., O.G., M.H., R.E.H., E.L., M.M. and M.N. contributed to data collection, interpretation and writing of the article.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgement

We thank all patients, doctors and nurses associated with the STCS.

Trial Registration: the study is registered on Clinicaltrials.gov under the registration No. NCT02361229.

verified

References

- 1.Bulliard JL, Panizzon RG, Levi F. [Epidemiology of epithelial skin cancers]. Rev Med Suisse. 2009;5((200)):882. 4-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lomas A, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath-Hextall F. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2012 May;166((5)):1069–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levi F, Franceschi S, Te VC, Randimbison L, La Vecchia C. Trends of skin cancer in the Canton of Vaud, 1976-92. Br J Cancer. 1995 Oct;72((4)):1047–53. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart B, Wild C. World Cancer Report. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003 Apr;348((17)):1681–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buell JF, Hanaway MJ, Thomas M, Alloway RR, Woodle ES. Skin cancer following transplantation: the Israel Penn International Transplant Tumor Registry experience. Transplant Proc. 2005 Mar;37((2)):962–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ong CS, Keogh AM, Kossard S, Macdonald PS, Spratt PM. Skin cancer in Australian heart transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999 Jan;40((1)):27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouwes Bavinck JN, Hardie DR, Green A, Cutmore S, MacNaught A, O'Sullivan B, et al. The risk of skin cancer in renal transplant recipients in Queensland, Australia. A follow-up study. Transplantation. 1996 Mar;61((5)):715–21. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199603150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen P, Hansen S, Møller B, Leivestad T, Pfeffer P, Geiran O, et al. Skin cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-term immunosuppressive therapy regimens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999 Feb;40((2 Pt 1)):177–86. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindelöf B, Sigurgeirsson B, Gäbel H, Stern RS. Incidence of skin cancer in 5356 patients following organ transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2000 Sep;143((3)):513–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartevelt MM, Bavinck JN, Kootte AM, Vermeer BJ, Vandenbroucke JP. Incidence of skin cancer after renal transplantation in The Netherlands. Transplantation. 1990 Mar;49((3)):506–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199003000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall EC, Pfeiffer RM, Segev DL, Engels EA. Cumulative incidence of cancer after solid organ transplantation. Cancer. 2013 Jun;119((12)):2300–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vajdic CM, van Leeuwen MT. Cancer incidence and risk factors after solid organ transplantation. Int J Cancer. 2009 Oct;125((8)):1747–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koller MT, van Delden C, Müller NJ, Baumann P, Lovis C, Marti HP, et al. Design and methodology of the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study (STCS): a comprehensive prospective nationwide long-term follow-up cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013 Apr;28((4)):347–55. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9754-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger C, Bochud PY, Boggian K, Cusini A, Egli A, Garzoni C, et al. Transplant Infectious Diseases Working Group, Swiss Transplant Cohort Study The swiss transplant cohort study: lessons from the first 6 years. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2015 Jun;17((6)):486. doi: 10.1007/s11908-015-0486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Study ST. Swiss Transplant Cohort Study. Basel: University Hospital Basel; 2015. Available from http://www.stcs.ch. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81((3)):515–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amorim LD, Cai J. Modelling recurrent events: a tutorial for analysis in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2015 Feb;44((1)):324–33. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krynitz B, Edgren G, Lindelöf B, Baecklund E, Brattström C, Wilczek H, et al. Risk of skin cancer and other malignancies in kidney, liver, heart and lung transplant recipients 1970 to 2008—a Swedish population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2013 Mar;132((6)):1429–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen AO, Svaerke C, Farkas D, Pedersen L, Kragballe K, Sørensen HT. Skin cancer risk among solid organ recipients: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010 Sep;90((5)):474–9. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizvi SM, Aagnes B, Holdaas H, Gude E, Boberg KM, Bjørtuft Ø, et al. Long-term Change in the Risk of Skin Cancer After Organ Transplantation: A Population-Based Nationwide Cohort Study. JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Dec;153((12)):1270–7. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrett GL, Lowenstein SE, Singer JP, He SY, Arron ST. Trends of skin cancer mortality after transplantation in the United States: 1987 to 2013. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Jul;75((1)):106–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iannacone MR, Sinnya S, Pandeya N, Isbel N, Campbell S, Fawcett J, et al. STAR Study Prevalence of Skin Cancer and Related Skin Tumors in High-Risk Kidney and Liver Transplant Recipients in Queensland, Australia. J Invest Dermatol. 2016 Jul;136((7)):1382–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.02.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Rosa N, Paddon VL, Liu Z, Glanville AR, Parsi K. Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer Frequency and Risk Factors in Australian Heart and Lung Transplant Recipients. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jun;155((6)):716–9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adami J, Gäbel H, Lindelöf B, Ekström K, Rydh B, Glimelius B, et al. Cancer risk following organ transplantation: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Br J Cancer. 2003 Oct;89((7)):1221–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naldi L, Fortina AB, Lovati S, Barba A, Gotti E, Tessari G, et al. Risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer in Italian organ transplant recipients. A registry-based study. Transplantation. 2000 Nov;70((10)):1479–84. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200011270-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerber SR, Seifert B, Inci I, Serra AL, Kohler M, Benden C, et al. Exposure to moxifloxacin and cytomegalovirus replication is associated with skin squamous cell carcinoma development in lung transplant recipients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Dec;29((12)):2451–7. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keller B, Braathen LR, Marti HP, Hunger RE. Skin cancers in renal transplant recipients: a description of the renal transplant cohort in Bern. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010 Jul;140:w13036. doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.13036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carroll RP, Ramsay HM, Fryer AA, Hawley CM, Nicol DL, Harden PN. Incidence and prediction of nonmelanoma skin cancer post-renal transplantation: a prospective study in Queensland, Australia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003 Mar;41((3)):676–83. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Reilly Zwald F, Brown M. Skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients: advances in therapy and management: part I. Epidemiology of skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Aug;65((2)):253–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fortina AB, Piaserico S, Caforio AL, Abeni D, Alaibac M, Angelini A, et al. Immunosuppressive level and other risk factors for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in heart transplant recipients. Arch Dermatol. 2004 Sep;140((9)):1079–85. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.9.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moloney FJ, Comber H, O'Lorcain P, O'Kelly P, Conlon PJ, Murphy GM. A population-based study of skin cancer incidence and prevalence in renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2006 Mar;154((3)):498–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramsay HM, Fryer AA, Reece S, Smith AG, Harden PN. Clinical risk factors associated with nonmelanoma skin cancer in renal transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000 Jul;36((1)):167–76. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.8290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramsay HM, Fryer AA, Hawley CM, Smith AG, Harden PN. Non-melanoma skin cancer risk in the Queensland renal transplant population. Br J Dermatol. 2002 Nov;147((5)):950–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinho A, Gouveia M, Cardoso JC, Xavier MM, Vieira R, Alves R. Non-melanoma skin cancer in Portuguese kidney transplant recipients - incidence and risk factors. An Bras Dermatol. 2016 Jul-Aug;91((4)):455–62. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiyad Z, Olsen CM, Burke MT, Isbel NM, Green AC. Azathioprine and Risk of Skin Cancer in Organ Transplant Recipients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Transplant. 2016 Dec;16((12)):3490–503. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tessari G, Naldi L, Boschiero L, Nacchia F, Fior F, Forni A, et al. Incidence and clinical predictors of a subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients with a first nonmelanoma skin cancer: a multicenter cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010 Mar;146((3)):294–9. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molina BD, Leiro MG, Pulpón LA, Mirabet S, Yañez JF, Bonet LA, et al. Incidence and risk factors for nonmelanoma skin cancer after heart transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2010 Oct;42((8)):3001–5. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tessari G, Girolomoni G. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients: update on epidemiology, risk factors, and management. Dermatol Surg. 2012 Oct;38((10)):1622–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dantal J, Hourmant M, Cantarovich D, Giral M, Blancho G, Dreno B, et al. Effect of long-term immunosuppression in kidney-graft recipients on cancer incidence: randomised comparison of two cyclosporin regimens. Lancet. 1998 Feb;351((9103)):623–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08496-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell SB, Walker R, Tai SS, Jiang Q, Russ GR. Randomized controlled trial of sirolimus for renal transplant recipients at high risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Am J Transplant. 2012 May;12((5)):1146–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guba M, Graeb C, Jauch KW, Geissler EK. Pro- and anti-cancer effects of immunosuppressive agents used in organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2004 Jun;77((12)):1777–82. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000120181.89206.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Donovan P, Perrett CM, Zhang X, Montaner B, Xu YZ, Harwood CA, et al. Azathioprine and UVA light generate mutagenic oxidative DNA damage. Science. 2005 Sep;309((5742)):1871–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1114233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hofbauer GF, Attard NR, Harwood CA, McGregor JM, Dziunycz P, Iotzova-Weiss G, et al. Reversal of UVA skin photosensitivity and DNA damage in kidney transplant recipients by replacing azathioprine. Am J Transplant. 2012 Jan;12((1)):218–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data