Abstract

Shared understanding is generated between individuals before speech through a language of body movement and non-verbal vocalisation, expression of feeling and interest made in gestures of movement and voice. Human understanding is co-created in these embodied projects, displayed in serially organised expressions with shared timing of reciprocal actions between partners. These develop in narrative events that build over cycles of reciprocal expressive action in a four-part structure shared by all the time-based arts: “introduction,” “development,” “climax,” and “conclusion.” Pre-linguistic narrative establishes the foundation of later, linguistic intelligence. Yet, participating in social interactions that give rise to narrative development is a central problem of autism spectrum disorder. In this paper, we examine the rapid growth of narrative meaning-making between a non-verbal young woman with severe autism and her new therapist. Episodes of embodied, shared understanding were enabled through a basic therapeutic mode of reciprocal, creative mirroring of expressive gesture. These developed through reciprocal cycles and as the relationship progressed, complete co-created narratives were formed resulting in shared joy and the mutual interest and trust of companionship. These small, embodied stories enabled moments of co-regulated arousal that the young woman had previous difficulty with. These data provide evidence for an intact capacity for non-verbal narrative meaning-making in autism.

Keywords: Narrative, Embodied intersubjectivity, Social connection, Intimacy, Autism

Introduction

Narratives are at the heart of meaning-making between individuals [1, 2]. They are typically considered dependent on language and an abstract, rational intelligence [3]. However, infant research demonstrates a precocious ability from birth to engage in pre-linguistic narrative meaning-making through expressive gesture of the body and voice [4, 5, 6, 7]. The enactive, participatory co-creation of units of meaning establishes a foundation for learning the patterns and embodied practices of a culture, from the proto-habitus of family life right through to the complex rituals and requirements of classroom learning [8, 9, 10, 11, 12].

Participating in social interactions is regarded as one of the central problems of autism. This is emphasised within the diagnostic criteria for autism and is reflected in the psychological research literature [13, 14, 15]. This emphasis on social impairment has led to a view that people with autism cannot engage easily with others, that they dislike social interaction, and that it is exceptionally difficult for them to create the kind of shared meaning that lies at the heart of communicative exchanges. These difficulties lead to a popular assumption that autistic individuals cannot communicate and develop within social interaction.

In contrast, this paper presents evidence that social interaction can be easy to create and enjoyable with a person with severe autism, given that one approach them in the right manner. It will explore the ability and motivation of a young autistic woman to engage with a new practitioner using a technique of interaction that adapted to her primary and basic sensorimotor level of expression using her rhythms and means of embodied expression in ways comparable to the rhythms of parent-directed speech. By doing so, the young autistic woman generated social engagement, play and companionship at the level of primary intersubjectivity. Based on this study, we suggest that autism does not prevent intersubjective engagement and exchange, but rather occludes it. This contention holds implications for contemporary theories of autism and about the empirical paradigms that the research and therapeutic fields employ, for these ultimately draw out, or obscure, behavioural capacities available.

Under typical circumstances people with autism can have difficulty engaging in communicative exchanges. These interpersonal difficulties have been explained as a deficit in understanding the personal perspective of the other, either from a cognitive disruption weakening one's capacity for “theory of mind” [13] or “central coherence” [14] or from an affectual disruption preventing emotional connectivity to others [15]. An alternative set of accounts, which are receiving growing interest, hold that a primary disruption exists in the sensorimotor systems of people with autism, obstructing efficient intentional movement and affective engagement [16] with evidence for disruption to an embodied “interactional system” [17] and possible disruption to the “mirror neuron system” [18, 19]. Sensory hyper- and/or hypo-sensitivities may exacerbate the condition [20, 21, 22]. These accounts argue that difficulties in perceiving and responding to the communicative behaviours of another underlie the social impairment, and are therefore possible primary deficits in autism that later give rise to more advanced developmental delays, such as those characterised as “theory of mind deficits” [16, 23].

Underlying all of these theoretical explanations, even if not explicitly acknowledged, is a concern with primary intersubjectivity. Primary intersubjectivity was first identified through detailed microanalysis of pre-verbal mother-infant interaction [24, 25]. It stresses the point that effective social interactions for learning and development require intersubjectivity. That is, communication requires two individuals, that is, two subjects, to produce interactions that are joint, entwined and mutually meaningful. Such intersubjective meaning is brought about through a process of mutual focus, turn-taking and responsiveness to the emotions and intentions of the other, as discerned in their facial expressions, eye gaze and body movements [26, 27]. It is in responding to and building upon the feelings and intentions of one's partner that joint meaning is created [28]. If a person were unable to perceive the actions of their partner as organised and meaningful, this would naturally render it impossible for them to communicate with that partner in any contingent and reciprocally meaningful manner, and social-dependent development can become thwarted [29].

Humans are capable of primary intersubjectivity from birth, reflected, for example, in the patterns of expressions between infant and parent [6, 7, 8] that create narrative structures resembling story-making [2, 4, 30]. These very early pre-verbal narrative patterns of meaning-making evident between infant and mother form the basis of verbal narratives that employ the same patterning of arousal and interest as in later linguistic childhood [9]. Their narrative forms remain a universal invariant, giving structure to the interactions and the ability to contextualise specific gestures and their affects within a unit of meaning with a discreet beginning, development, climax and resolution [31]. These narrative forms of intersubjective engagement are based on the capacity to perceive and respond with sensitivity to changes in the other's emotional attentiveness, thereby yielding periods of engagement with turn-taking and temporal synchronicity [24, 25, 26, 27, 30, 31, 32].

These exchanges are organised into rhythms and phases, with characteristic contours of energy. Periods of engagement are punctuated with periods of disengagement. The predictability of this structure has led theorists to classify infant-adult interactions as “proto-narratives” [33], but their invariance of form and structure across development, from pre-verbal to verbal narrative, suggest these are not simply precursors to narrative, but are in fact fully fledged acts of meaning-making; the term “narrative” holds true [4, 8]. Such evidence underlies Bruner's [1] view that “narrative structure is even inherent in the praxis of social interaction before it achieves linguistic expression” (pp. 77).

Autistic people can struggle with this intersubjective, co-creation of meaning. Evidence indicates that they do not share the same temporal, co-created patterns of arousal and excitement that non-autistic children and adults do and that the mismatch between autistic and non-autistic patterns of action may disrupt communication and development [34, 35]. However, we reasoned that if it could be shown that autistic individuals are capable of building mutual narratives organised in standard structures, with an engaged partner, then that would address queries central to contemporary theoretical debates about autism. Are autistic people able to engage in spontaneous exchanges and, if so, under what circumstances? Why has the literature so repeatedly demonstrated deficits in this regard?

What do interpersonal narrative structures look like? Bruner [1] has typified them as composed of a 4-part structure, unfolding over time and moving through its sequence of phases as (i) initiation, (ii) build, (iii), climax and (iv) conclusion. Over the course of an extended communicative exchange between two people, this narrative structure may arise a number of times. Narratives occurring later in the interaction are likely to pick up themes from earlier narratives, thus weaving an overarching narrative that enriches the relationship between the two partners.

This narrative structure requires two key features, which carry implications for theories of autism [16]. First, the two individuals must attend to and be cognisant of each other's expressive acts. These expressions always occur through intentional actions of the body, that is, through facial gestures, bodily movements and vocalisations. They constitute a primary level of expressive action [36]. Thus, it is imperative that the sensorimotor systems of the two partners be sufficiently attuned to one another, for it is only through attuning one's sensorimotor system to the partner that it is possible to perceive their expressive acts and to respond to them in a reciprocal exchange. Second, the exchange needs to have a rhythmic temporal pattern. Successful interactions depend upon a shared tempo, with particular expressive acts usually occurring on the “beat” [7]. It is the sharing of rhythm that is important for the co-creation of meaning [1, 8].

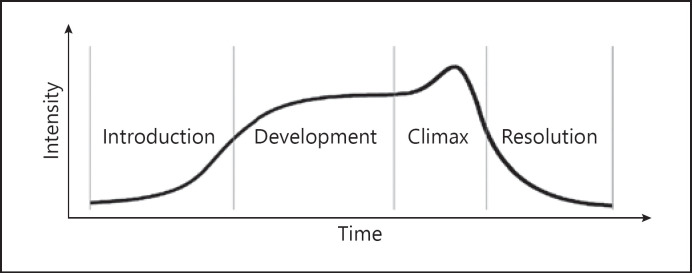

The basic form of narrative is a skewed curve (Fig. 1) [2], where (i) the initiation of the narrative opens the intensity of energy between the two partners; (ii) reciprocated expressive acts, enacted in rhythmic exchange, build the emotional, psychological and often physical intensity of the interaction over the beats of bars and with the quality and timing of each expressive act crafting its feel, character and tone until; (iii) the two participants climax to a point of maximal tension before and (iv) their energy dissipates and the narrative recedes to its conclusion, falling back to a more relaxed level. As the plot in the narrative thickens over its course, so too does its intensity, achieved through a richer set of invested actions and reciprocated re-actions, an increase in the modalities utilised and often greater force and dimensionality of movement. By the end of the conclusion, the narrative has died, but the experience of its creation will remain with each of the partners and between them they will hold its special memory − a memory of a unique, shared experience, the co-creation of which imbues the memory with “meaning.” The conclusion is typically followed by a pause, or period of disengagement, which allows the two partners to renew their mutual focus, ready to begin building a new narrative cycle.

Fig. 1.

Intensity contour of a narrative over 4 phases: (i) “interest” in the narrative begins at a low-intensity in the introduction, which “invites” participation in purposefulness; (ii) the coordination of the actions and interests intensifies over the development, as the “plan” or “project” develops; (iii) a peak of excitation with achievement of mutual intention and interest is reached at the climax, after which (iv) the intensity reduces as the participants share a resolution, and the close engagement separates. Reproduced with permission from Trevarthen and Delafield-Butt (2013).

In this paper, we adopt the theoretical framework of narrative to explore the interaction of a young woman with autism during her first meeting with a new practitioner. This is unusual in studies of autism, despite the view of seminal developmental theorist that narrative is central to understanding human communication. Similarly, Read and Miller [38], social psychologists, consider narrative to be “universally basic to conversation and meaning making” (pp. 143). We chose a case study approach because it allowed us to examine communicative interaction in microanalytic detail. During the exchange analysed here, the practitioner employed a technique known as Intensive Interaction, the core principle of which is that the practitioner attune their bodily movements and rhythms to those of their autistic partner [39]. Previous practice-oriented evaluations have shown that Intensive Interaction nurtures social interest and emotional engagement, while also reducing distress and challenging behaviour [40, 41]. We were curious to know whether or not this technique was effective enough to yield the kind of interpersonal, meaningful narratives thought to be difficult for people with autism. We were especially interested in whether narratives built by the pair would take the same form traced for other non-verbal cohorts, especially mother − infant dyads, or a different form.

We hypothesised that there remains within autism a basic human capacity for intersubjective meaning making, expressed through the co-creation of narratives, and that this basic capacity is elicited when a partner behaves in an emotionally and behaviourally attuned manner. We thus reasoned that if a standard narrative pattern was present within the interactions between a severely autistic person and a new partner, this would attest strongly to a capacity for intersubjectivity present and active in both. The aim of this study was to determine whether or not this capacity for intersubjectivity through narrative co-creation could be identified in the interactions of the dyad of an autistic person and her partner, and if so, we were curious what we might see within those episodes that could improve our understanding of the aetiology and function of autism. If a severely autistic person can be shown to co-create joyous, joint narratives with a stranger, in a period well under one hour, then a new basis can develop for understanding autism and, indeed, human connection more widely. We will suggest that that new basis is likely to lie within a sensorimotor, rather than cognitive account.

Materials and Methods

Design

The study adopted a case study design, in which a therapeutic session between a young female adult with autism and a practitioner specialising in the technique of Intensive Interaction was examined microanalytically. This session constituted the first occasion on which the two had met and also the first occasion on which this form of intervention had been attempted with this young woman. Ethical permission for the use of the video footage was granted by the institution in which she resided and by the School of Psychology Ethics Committee, University of Dundee.

Participating Dyad

The young client, Kirsten (not her real name), was 18 years old and had attended a daily educational resource centre for a number of years. Filming took place at the resource centre. Kirsten's diagnostic classification indicated severe autism. She was entirely non-verbal and consistently psychologically and emotionally distant. She frequently exhibited stereotypies (e.g., head shaking, slapping and rocking) and extremely aggressive behaviour, including biting, scratching and kicking staff, on a daily basis. Previous intervention approaches had failed to reduce the extremity of her challenging behaviour − termed ‘distressed behaviour’ within an Intensive Interaction framework. The practitioner was very established in the use of Intensive Interaction, experienced particularly in its use with individuals with severe autism. She had been invited to work with Kirsten because staff had become fearful of her increasing aggression (i.e., distress) and had found no means of reducing it.

Intervention Technique

Intensive Interaction involves interacting with a person by using their own sounds and movements [39, 42]. The practitioner partner intently observes what his/her client partner is doing and then “joins in,” using the same movements, vocalisations and rhythms in a creative, non-rigid manner. The aim is to respond to the client's interests, concerns and behaviours, such that the client comes to recognise the practitioner's actions as a response [43]. The technique offers a means of building a direct, contingent and embodied relationship between the two partners within the domain of primary intersubjectivity.

Microanalysis and Coding

The video footage was digitally transferred to a computer movie file (H.264 Codec, QuickTime, Apple Inc.,) to allow analysis in normal, fast, slow and frame-by-frame playback modes. This flexibility allowed for precise (±1 s) temporal mapping of vocalisations and expressive acts.

Engagement Periods

First, periods of engagement between the therapist and her client were identified and their beginning and ending times recorded. Engagement periods were operationally defined as periods of engagement between the therapist and patient during which time expressive action was either (a) attempted by one or the other person (e.g., knocking on the door or rubbing hands on the wall), or (b) expressed by one person and responded to by the partner, indicating it had been treated as if it were communicative even if it was unlikely that the partner had intended it in this fashion (e.g., moving legs across the bed surface), or (c) an act was delivered and received as communicative (e.g., a sharp foot-slap on the mattress). The start time of an engagement period was coded by the video frame time (rounded down to the second) in which the occurrence of the act began, and the end time was coded as the video frame time (rounded down to the second) when attention to the partner had been withdrawn (e.g., by turning the head away). The periods of time between engagement periods were classed as “interim periods.” A narrative description of the events occurring during all engagement and interim periods was compiled (Table 1). Coding for engagement periods was performed by the first author and verified by the authorship team.

Table 1.

Description of the interaction in each engagement and interim period

| Engagement | Time codes: onset and end | Total duration | Description of activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00–1.03 | 3 s | The practitioner (P) is standing outside the room where the client (K) is lying on waterbed face-down with her feet to the door and her head partially under a pillow; 3 carers are sitting quietly in corners of room; P tentatively invites interaction from K by rapping 3 times lightly on the door; P remains outside its threshold, as one would do when knocking to come into a house |

|

| |||

| Interim | 1.03–1.12 | 9 s | P waits in silence for a response from K; some words are exchanged between P and the carers |

|

| |||

| 2 | 1.12–1.15 | 3 s | P repeats the rapping with 6 knocks on the door |

|

| |||

| Interim | 1.15–1.20 | 5 s | P waits in silence for a response from K |

|

| |||

| 3 | 1.20–1.35 | 15 s | K makes sweeping movements with her legs on the waterbed, extending them laterally and then retracting back again, in a roughly rhythmic manner; P mirrors this action by rubbing her hand against the wall, using the same rhythm and shape as K's actions; this produces the same acoustic effect as K's movements; P steps over the threshold (at 1;33), to stand by the wall at the foot of the waterbed |

|

| |||

| Interim | 1.35–1.43 | 8 s | Stillness and silence by both P and K |

|

| |||

| 4 | 1.43–2.04 | 21 s | K moves first with a leg sweep; P imitates with her hand rub on the wall; there appears to be some dialogue between their actions, with elements of turn-taking and imitation; further, K raises her head slightly from the mattress, as if attending more alertly to P; the engagement ends with P giving 6 strong rubs as if to continue the engagement more strongly |

|

| |||

| Interim | 2.04–2.08 | 7 s | Stillness and silence from both P and K |

|

| |||

| 5 | 2.08–2.17 | 9 s | K's head remains lifted from the bed, which takes a determined use of physical energy; unexpectedly, K raises her right foot and slaps it down on the bed, yielding a very audible “slapping” sound; responds by slapping the wall, coordinating her slaps with K's, producing some very minor rhythmic turn-taking; P intensifies the interaction by using 2 slaps as a reply to each of K's single slaps; K produces a single slap, then a double, then a triple foot slap; P came in on top of this final triple with yet more slaps, this time in the rhythm of a sextuplet; that proved to be an end to the engagement, because K did not respond further |

|

| |||

| Interim | 2.17–2.22 | 5 s | Stillness and silence from both P and K |

|

| |||

| 6 | 2.22–2.23 | 1 s | P slaps on the wall, inviting engagement |

|

| |||

| Interim | 2.23–2.50 | 27 s | Stillness and silence from both P and K |

|

| |||

| 7 | 2.50–3.33 | 43 s | A new engagement emerges slowly, beginning with K's sweeping movement of her legs across the bed, in a rough rhythm; P once again mirrors this, with her hand against the wall, overlapping and sometimes initiating in synchrony with K's leg movements; then, K produces 3 foot-slaps; P imitates and then doubles the number of slaps; K produces a single slap; P concludes with a single slap; all of these acts are taken in turns, before each returns to sweeping motions, on the bed and wall respectively; these movements (and especially their acoustic effect) occur in an overlapping manner; they never become rhythmically coordinated, though, and after some seconds, seem to die away |

|

| |||

| Interim | 3.33–3.38 | 5 s | Stillness and silence from both P and K; P glances around the room |

|

| |||

| 8 | 3.38–3.51 | 13 s | P now moves closer to K, leaning over the end of the mattress and delivering slaps onto the surface of the mattress; momentously, K actively lifts her head from the bed, listening more closely to the sounds emanating from the foot of her bed; however, she does not turn her head to look in the direction of the sounds (or, thus, to look at P); P gives several slaps on the mattress; K lifts her head yet higher to hear the sounds; K replies with 3 foot slaps, delivered by alternating her feet; P replies in turn with a fast series of hand slaps; K listens for further slaps, but does not actively reply |

|

| |||

| Interim | 3.51–3.59 | 8 s | Stillness and silence from both P and K |

|

| |||

| 9 | 3.59–5.46 | 107 s | K abruptly returns her head to the bed, which is still lodged under the pillow. She resumes her leg sweeps; P once again mirrors these sweeps, echoing their rhythm and quality; the sweeping motions offered by P garner a foot-slap from K; P responds with a comparable hand-slap, K responds with a foot-slap, and P responds accordingly; crucially, P heightens the intensity by using a double hand-slap, rather than an imitative single slap K then does something novel; she replies with short, sharp contractions of her legs, which push her feet down into the waterbed mattress; this has the force and sharpness of a foot-slap, but is achieved without raising the leg, so requires a different, more forceful kind of physical energy from her body; P picks up on this novel expression, bringing it playfully into the exchange, by pushing her hand downward into the mattress, P continues pushing at the mattress, producing the same kind of thrusts and ripples that K had previously created; K repeats her leg contractions, producing a corresponding reply from P, who once again increases the intensity of the interaction by pushing down fast and hard, with both hands, into the mattress, putting the weight of her whole body behind the movement to give it added force; this generates strong ripples that flow down the entire length of the mattress and the length of K's body. Immediately, K returns to sweeping movements of her feet, although this time carried out with more force, thus maintaining the ripples of the mattress; P mirrors this movement, and the ripples, with her hands, overlapping with K's movements; K then delivers a sharp foot-slap (at 4.48), to which P responds with a triple hand-slap; a rhythmic, turn-taking exchange of single and double slaps then ensues; there is an oscillating rise and fall in intensity as the movements shift from periods of rubbing to periods of slapping; K is initiating all of the intense slapping episodes; P is amplifying them by increasing the number of slaps into a rapid sequence of expression; P&K build up the intensity of the interaction, until K does something new again: she slides her body down toward the end of the bed, toward the place and person from which the acoustic and vestibular stimulation emanates; indeed, while K is sliding her body, and simultaneously making a foot slap, K reaches out and slaps P's hand as it comes down to make a hand slap; Bodily contact has been made. This contact results in 2 consequences; first, K quickly scoots up the bed, returning herself to her original position; second, P appears to feel invited to come to sit, in a settled posture, at the foot of the bed for more intimate, direct play; More slapping play ensues; as it does so, K chooses to turn around fully, to orient visually to P; P smiles broadly at this interest; the 2 look at each other directly, in a sustained fashion, and continue to play, with P smiling broadly; to the viewer, the psychological contact has intensified significantly; K brings her foot actively and purposefully onto P's hand; for the first time, they both vocalise, in unison, in joyful laughter; heir play continues on this elevated level, now with regular touching and regular vocal exclamations, supplied particularly by P, to emphasise the moment of contact; moments of teasing enter the game, with P moving her hand sideways and K succeeding in coming into tactile contact with it nonetheless; their modes of communication have expanded |

|

| |||

| 10 | 5.46–5.59 | 13 s | The playful slapping exchange between the pair continues, but it is now calmer and less intense; the pace of the slaps is slower, the force lazier; the relation between them feels companionable; K is smiling very broadly, as is P |

|

| |||

| 11 | 5.59–6.27 | 28 s | K is lying on her stomach, facing away from P; she delivers a more emphatic foot-slap than has been the case for some seconds, her right foot slapping P's right hand; P's left hand then comes over to slap K's right foot; K's left foot then slaps, stacking on top of P's right hand; P's left hand comes over to slap and stack on top of K's left foot; this cycle is repeated until they come to a climax, both exclaiming their contentment with highly vocal laughter (at 6.17); the intensity of the game declines slightly for a few moments; then P and K renew the slapping-stacking game, picking up the pace briefly and continuing to take turns; P places her slaps on the soles of K's feet; K places her foot-slaps on the bed; they pass through 3 cycles of exchange until K breaks off and withdraws |

|

| |||

| Interim | 6.27–6.34 | 7 s | K disengages from the exchange moves the whole of her body rolling onto her side, she reorient to P as she does so, with the pillow still held over her head |

|

| |||

| 12 | 6.34–6.54 | 20 s | K stretches our her left leg toward P and makes a foot slap; P responds with some slaps to the bed; the pair return to games of slapping and touching, in a rough rhythmic fashion; the rhythm has changed and intensified, in that the turns are more languorously spaced, and moments of touching between K's foot and P's hand extended, between slaps; vocal exclamations of excitement accompany the slaps; K uses both feet, very intentionally, to place slaps on P's hands; the excitement that has been mounting is stopped, suddenly, when K disengages by failing to take another turn, instead lying back and looking up at the ceiling |

|

| |||

| Interim | 6.54–7.00 | 6 s | K momentarily lies in this new position, rocking slightly from side to side |

|

| |||

| 13 | 7.00–7.01 | 1 s | P slaps and holds both of K's feet, but K does not engage |

|

| |||

| Interim | 7.01–7.08 | 7 s | K brings the pillow over her head and retracts her feet toward her trunk and away from P |

|

| |||

| 14 | 7.08–7.48 | 40 s | P makes a wailing sound; K brings her foot forward and slaps it down; P slaps her hand on it; P and K then renew the turn-taking slapping game; K is now lying on her back, monitoring P's movements through the mirror, and with one arm hanging on to the pillow, positioned behind her head; the intensity and intimacy of the slapping game increases, with slaps that linger in the touch they provide; vocal exclamations remain; the game gives way to a combination of slapping and pushing, picking up earlier themes in the play; each teases the other, with P running a series of slapping movements towards K's feet; K retracts her feet, keeping them out of P's reach; all of these qualities intensify the emotional energy and intimacy of the interaction; this intensity then dissipates, resulting in a sense of shared, calm quiescence |

|

| |||

| Interim | 7.48–8.02 | 14 s | K lies still for a few seconds; then, unexpectedly, K makes an effortful body movement, pushing herself up and rolling to the side with the pillow covering her head; it looks as though she is going to withdraw and P makes an “Oach” sound of disapproval; K then determinedly pushes her torso upward, until she is sitting on her knees and is reoriented directly facing P; K is situated at the far end of the mattress |

|

| |||

| 15 | 8.02–8.37 | 35 s | K moves her body rhythmically, leaning backwards and forwards, pushing herself with both hands, on and off her haunches; she does this with laughter and high, bouncy energy; her hands push down on the mattress, while P's slap down on the mattress; they are taking turns and both are laughing; this movement has led their hands to reach a place where they each touch; there is a brief moment of release and then a renewed touch; then, with both hands stretched out, K slaps P's hands and extends fully forward, into the centre of P's chest; P opens her arms in what feels a totally natural and spontaneous response, embracing K with a long, contented “Ahhh”; K exhales vocally and relaxes; both rest their heads nuzzled into each other's shoulders, in an extended, intimate, calm embrace; here follows a period of gentle laughter and intimate sighs K disengages slightly, putting a small space between herself and P, as if to renew the hand-slapping game; but she then breaks off abruptly and returns to a psychologically disengaged state, looking away from P and shaking her head from side to side; P marks these had movements with rhythmically matched vocalisations |

|

| |||

| Interim | 8.37–9.10 | 33 s | K then stands up abruptly and walks purposefully away from the mattress, sighing and grunting repeatedly, vocally; she walks to the far side of the room, away from P, making it clear she wishes to put distance between P and herself P follows K at a distance, making herself available should K wish to begin interaction on this new side of the room; K does not do this, however; instead, she returns to the waterbed and lies down again, facing the place where P was last sitting and where they had just shared an intensely intimate moment |

|

| |||

| 16 | 9.10–10.52 | 102 s | K calls P over to the mattress by slapping it twice, sharply; as P nears, K slaps again, and P is now able to join in, slapping the mattress, in turn, as she sits down on the floor, facing K; without skipping a beat, they are back into a hand-stacking game; they come to the conclusion of the exchange very quickly; lets out a long sigh of relief as the game concludes; they pause, sitting closely together again once more; a shift occurs in the pace (at 9.41); it is less intensive and focused; the 2 remain physically close together, oscillating between close face-to-face contact with intimate whispers, touching with fingers and hands, and grunting vocalisations interspersed with episodes of more defined engagements, with hand slaps and hand stacks |

|

| |||

| Interim | 10.52–10.58 | 6 s | K disengages, arches back gently, and glances around the room slowly; P waits still and silent |

|

| |||

| 17 | 10.58–11.50 | 52 s | K returns to lying facing P as before, P sits at the end of the bed on the floor with her legs outstretched; K extends her hand across the end of the bed and makes a slapping motion towards P in the air; P playfully slaps her hand (as with the stacking game); K makes some scratching movement and P tells her off; K laughs and turns away slightly, P laughs and the observers laugh; play continues; P adds slaps and vocalisations that match the timing of K's hand movements; there a few shrugs of shoulders alternated between them and grunting vocalisations from K and echoed by P, which maintain the feeling that had been achieved during delivery of the slaps; laughter and teasing is frequent |

|

| |||

| Interim | 11.50–11.54 | 5 s | K backs up and sits on her feet, pausing briefly; P watches with her arms crossed |

|

| |||

| 18 | 11.54–13.58 | 124 s | P and K simultaneously make movements; P slaps her hands on the mattress and K lunges forward, slapping both hands on the mattress so she is now on all fours; P echoes with slaps as does K; this could be a moment repeating the embrace (in Engagement 15), but P remains seated and K flops to the bed, resuming their previous intimate position facing each other with more gentle slaps and vocalisations The engagement recedes in intensity; K looks around the room, but maintains gentle, rhythmic slaps in tune with P's; there is some gentle stroking of the hands and K rocks her body gently on the waterbed; the play becomes lazy, but continuous; they look at each other through the mirror; P imitates some basic nose scratching by K; the engagement continues to reduce in energy |

|

| |||

| Interim | 13.58–14.03 | 5 s | K moves to the end of the bed and lies on her back, looking up at the ceiling; P remains still and begins talking to the observers |

|

| |||

| 19 | 14.03–14.40 | 37 s | K returns to P and makes a lunging movement; P calms her down and rubs her head; K returns to lying facing P and the 2 resume quiet, relaxed games of gentles slaps; K becomes distracted by the zipper of the bed and P begins to talk to the observers about what has occurred in the session; their interaction concludes |

All of the engagements were then coded by four variables: narratives phases, complexity, proximity and emotional valence. Next, ten randomly chosen engagements from the nineteen identified were coded by another researcher. This researcher was naïve to these data and this project, but familiar with infants and children. She was instructed to code the variables as per the definitions below, then left alone to code them. Inter-rater reliability was calculated for each of the variables. Cohen's κ value was >0.89 for each variable (mean 0.94). The variables were coded as follows.

Narrative Phases

For each engagement period, we identified the occurrence or absence of the four phases of narrative units, operationally defined as follows. Initiation: initial act that could have been or was treated as communicative. Build: receiving a response from a partner's initiation, often in a reciprocal form, but not necessarily. Climax: an energetic apex, following a period of building intensity. Conclusion: decrease of energy and intensity, following a climax, in which the ensuing calm is shared by the two partners. It is inherent within the structure of narrative units that classifying a later phase as ‘present’, within any particular engagement period, means that earlier phases must already have been identified. Without this continuity, a coherent narrative story would not exist.

Complexity

We monitored the complexity of interactions by noting the expressive acts and modalities through which communicative exchanges were delivered. For each engagement period, we recorded when any of the following behaviours featured in the exchange: slap, rub, push (on bed), turn of head or body (to orient to partner), vocalisation, touch partner and full embrace. The total number of different expressive acts was calculated for each engagement period.

Proximity

We tracked changes in the proximity of the pair, using a scale of closeness. A position of face-to-face gaze was treated as baseline (0). Steps representing less proximity were as follows: outside the room (−5), just inside the room (−4), standing near the bed (−3), sitting at the foot of the bed (−2), reaching to touch Kirsten's foot on the bed (−1). The only step that represented proximity greater than baseline was embracing (+1). For each engagement period, we recorded the highest level of proximity exhibited.

Emotional Valence

We tracked changes in the emotion displayed by each member of the dyad. Neutral was treated as baseline, represented by a “score” of 0. Positive categories were represented as smile (+1) and laughter (+2). Negative categories included frown (−1) and distress (−2). For each engagement period, we recorded the highest level of emotional valence exhibited by each member.

Results

Engagement Periods

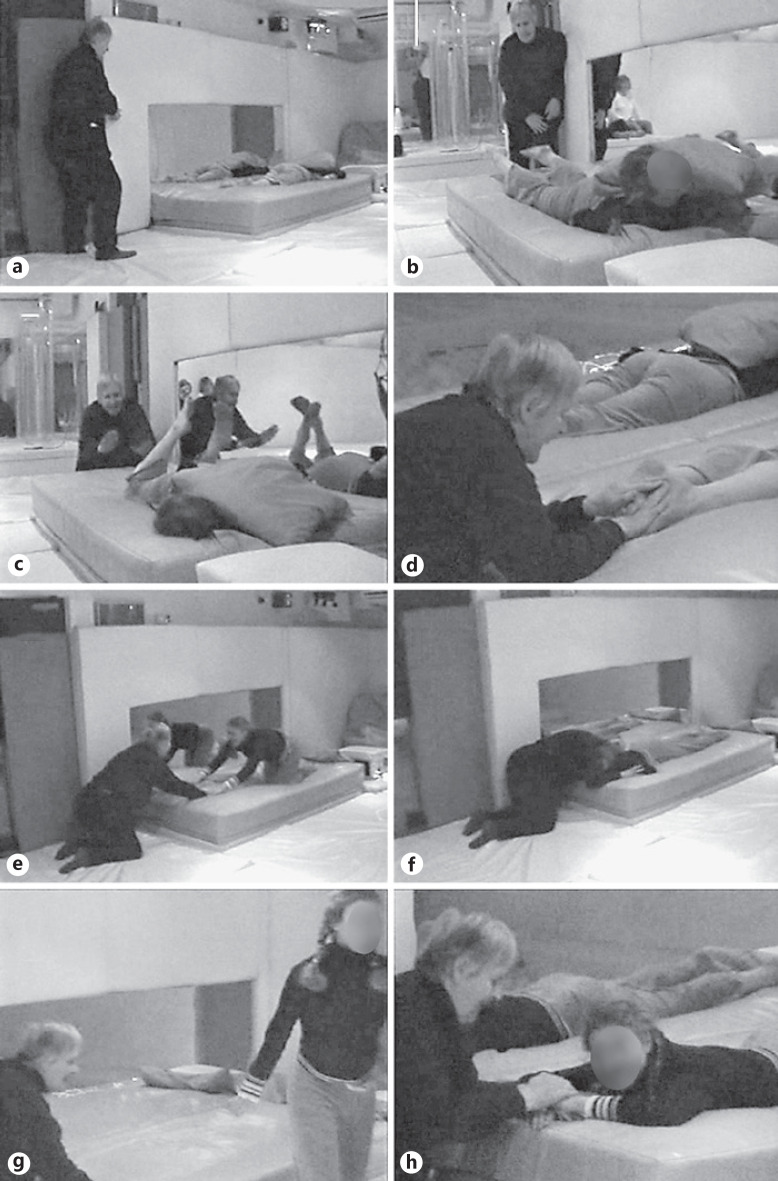

A total of nineteen engagement periods were identified during the 15 min of the intervention session, ranging in length from 1 to 124 s. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the exchanges that took place during each engagement period and their associated interim periods. Figure 2 provides an illustration of these exchanges, using a storyboard of still images extracted from the video.

Fig. 2.

Storyboard of still photographs extracted from video recording of the intervention session. a Engagements 1–7. The client has chosen to lie on the waterbed face down, with her feet to the practitioner. She makes rubbing motions with her legs at first, then rubs and slaps in response to the practitioner (standing), who approaches from a distance and invites interaction through slapping or rubbing the wall. b Engagement 7. Rapport develops between the pair. The client partially orients to the practitioner, who has taken up a position at the foot of the bed. c Engagements 9–14. The interactions of the dyad develop, becoming more intimate, with increased modalities and breadth of expression and with full orientations by the client to the practitioner, including (d) developing hand-on-foot play. e Engagement 15. Their interaction climaxes as the client orients her entire body to the practitioner, oscillates it back and forth and lunges (f) into a final embrace. After this climactic unification, (g) the client takes a break from togetherness. h Engagements 16–19. After a moment, she returns to the bed for more intimate and quiet face-to-face interaction. Note: the facial features of the client have been masked to maintain her anonymity.

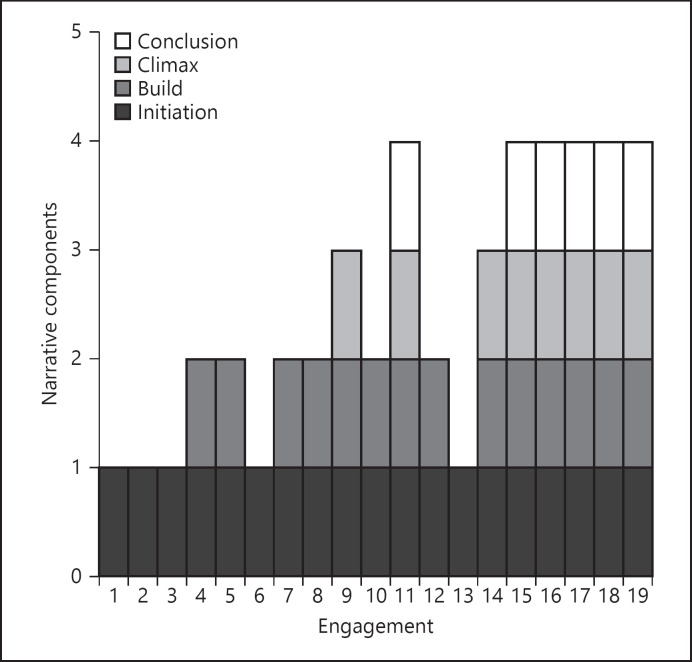

Narrative Structures

It was predicted that if the interactions reflected actual intersubjectivity, they should also demonstrate the four-part narrative structure that has been shown in other human communicative interaction, including adult-infant interaction. We were especially interested in whether all the components of the narrative emerged (i.e., initiation, build, climax and conclusion), and if not, how these episodes of engagement differed from standard structures.

We found that narrative units became more complete as the intervention session progressed (Fig. 3). In the early engagements, only initiations were observed. It was not until Engagement 4 that any reciprocity in expressive acts emerged. Once established, it became possible to turn-take, nurture intensity, and develop a “plot line” around which expressions could build. However, there was an absence of any climax until Engagement 9, which meant that the intensity of these “plot lines” had nowhere to go and that the client withdrew from these early interactions. In observation, this termination left us with a sense of unsettled, emotional distance.

Fig. 3.

The narrative components featured in each engagement.

In Engagement 9, the pair experienced a climax where the intensity that they had been building reached an apex. Interestingly, this was also the most complex of all the engagement periods, involving an extensive amount of negotiation. It is during this engagement within its cycles of reciprocity that more creative expressive acts, such as pushing down on the waterbed, emerged and the modalities involved in the communication expanded (see details below). It is significant that this engagement offered the first occasion on which joy was expressed, through smiles and laughter (as described in Table 1). This would be expected for the climax of an intersubjective exchange. Notably, however, no conclusion was permitted. The client withdrew before a period of quiescence was allowed.

It is only two engagements later, during Engagement 11, that a conclusion to the narrative units finally emerged, thus constituting the first time that the pair had been able to share an entire narrative cycle. Once they did this, their emotional valence was maintained in positive affect for the rest of the session. We reason that completion of the narrative unit with its intimate climax and conclusion enabled each participant “appropriate” the shared, co-created episode of meaning.

Overall, the pattern of narrative components shows the predicted four-part narrative structure did emerge. Crucially, it took time for those to develop; they were not present from the outset. Once the pair had established turn-taking communication through an initiation and build, they did not lose this intersubjective capacity. The engagements that were being constructed became more coherent and more structured along narrative lines. We argue they become more psychologically meaningful in this way. The client's apparent increasing joy in the engagement is evidence to this effect and appears a consequence of a developing coherence in her social engagement and is indicative of an internal experience of a sense of “meaning”.

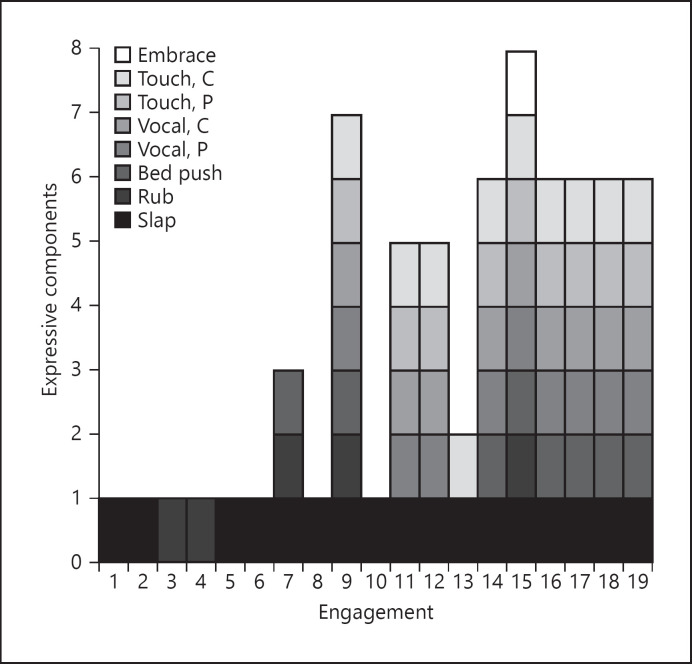

Complexity

The presence of modalities and means of expression increased over the course of the session (Fig. 4). The session begins simply with engagements consisting only of slapping or rubbing expressions. As the session progressed, a wider range of expressive acts was used in each engagement, moving from only the slap or rub (Engagements 1–6) to pushing the bed and combining these in different ways (Engagements 7, 9). Then, the composition changed markedly, first in Engagement 9, with energetic bed pushes, and then in Engagement 11 where vocalisation and touching became prominent, interestingly at the point where the full narrative unit also became apparent (Fig. 3). Vocalisation and touching remained prominent and regular in every engagement thereon out. When the total length of relevant engagement periods is calculated (from Table 1) and compared, it becomes clear that 66% of the session was spent in complex exchanges with slapping, vocalisation and touch.

Fig. 4.

Type of expressive components featured in each engagement measured as dyadic (slap, rub, and bed push) or individual (vocal, and touch) contributions. “vocal, P” and “vocal, C” denote practitioner and client vocalisations, respectively. “touch, P” and “touch, C” denote the practitioner touching the client and the client touching the practitioner, respectively.

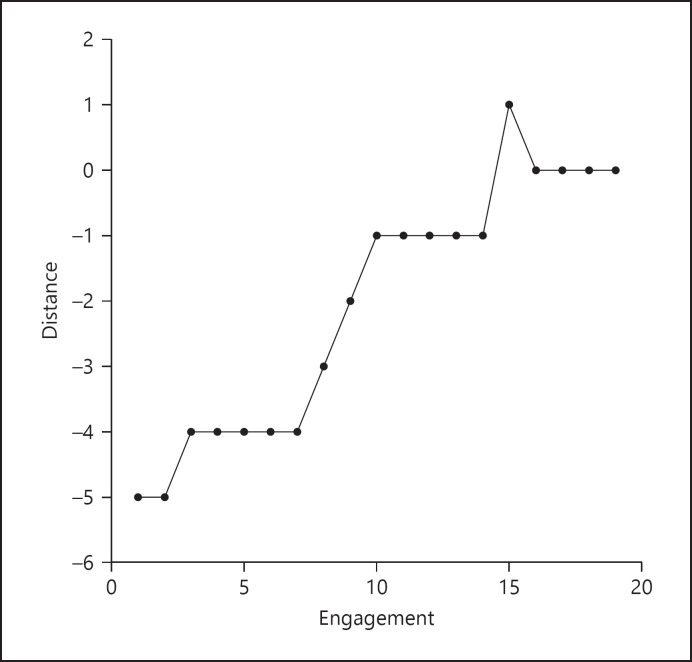

Proximity

The proximity of the partners increased over the course of the session (Fig. 5). They began from a distance and came into physical contact in Engagement 10, when the practitioner touched Kirsten's foot from the end of the mattress. The subsequent engagement is the period during which the narrative phase of “climax” emerged for the first time. The session itself came to a climax at Engagement 15 when the 2 partners embraced and laughed together, after which proximity settled to an intimate face-to-face position for the remainder of the session.

Fig. 5.

The proximity of the practitioner to the client, scored as (−5) outside the room, (−4) entering the room, (−3) standing near the bed, (−2) sitting at the foot of the bed, (−1) reaching to touch, (0) sitting face-to-face and (+1) embracing.

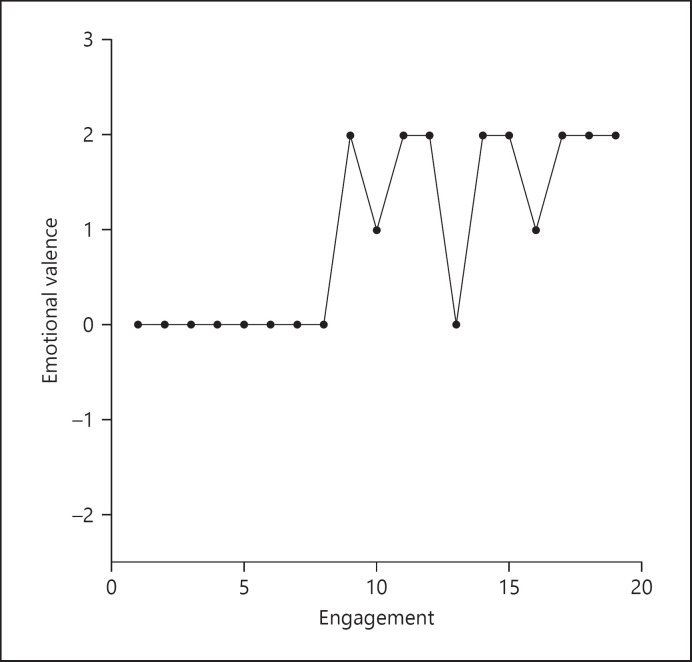

Emotional Valence

The session progressed from a neutral valence to positive affect (Fig. 6). The pair begin emotionally neutral, neither displaying hostility nor happiness. They remain this way over the course of the first 8 engagements. In Engagement 9, this changed markedly and both client and practitioner break into laughter and smiles after a long and complex negotiation of play with expanding modalities (Table 1). The laughter marked the climax of a narrative (see above). Once this positive affect was established, it was maintained throughout the course of the session, moving between low and high levels. (Only Engagement 13 was devoid of positive affect, because it was merely an unanswered initiation lasting one second.)

Fig. 6.

The emotional valence of the dyad in each engagement from high-negative (−2) through neutral (0) to high-positive (+2) affect.

Discussion

These data show the intervention was successful in promoting emotional engagement, rapport and intersubjective communication. Within a single session, trust and companionship had been established between the practitioner and young woman, whereas previously anxiety had been the dominant affect and violence the dominant social behaviour. Primary intersubjectivity was evident through the changes in the measured variables and especially though the co-production of standard narrative structures. These data speak to a need to reconsider contemporary accounts of autism.

Narrative and Primary Intersubjectivity

The development of multiple modalities of expression, proximal intimacy, positive emotional valence and the increasing narrative structuring of the pair's engagements altogether make clear that primary intersubjectivity was operative. The therapist and patient engaged with one another, formed rapport, and established positive relations that climaxed into a full embrace and concluded with intimate, gentle face-to-face play. They engaged with each other with teasing and provocation initiated at different times by one or the other. Their expressions of voice and body were made in rhythmic turn-taking in multiple modalities that altogether formed predicted narrative patterns [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 44].

The success of the intervention to bring out intersubjective relations may be due to the practitioner's means of attuning to the client through imitation, as well as her respectful approach. Imitation has been shown to be an effective means of engaging both autistic and non-autistic children and infants [45, 46, 47, 48] and is thought to assist what has been termed “mind-reading” [49]. By attuning to the level of sensorimotor function available to a partner, imitation creates a channel through which communication may take place. Thus, an intersubjective connection is afforded. The fact that communicative engagement, such as we have shown here, is so seldom reported in the experimental or intervention literature can be explained by the fact that it is rare for experimenters or practitioners to purposefully attune their movements with those of their autistic partners. Indeed, it can feel awkward as it requires breaking social norms.

The opening engagements (1–3) made by the practitioner were simple invitations to engage based on the spontaneous body movements of the autistic woman. She quickly engaged with these and began to turn-take with her practitioner's expressions (Engagements 4–5, 7–8), building in other means and modes of expression as she did. The ease and rapidity of her engagement is notable, given her history of aggressive, distressed behaviour. From the beginning, these bouts of playful turn-taking began to take on narrative form, building in plot until, in Engagement 9, the pair came to a climactic peak and vocalised in laughter together. Simultaneous multimodal expression is characteristic of narrative climaxes, giving a peak moment of excitation and energy. As the engagements progressed, so too did their intimacy and trust, reflected in the proximity of one to the other and in the client's visual orienting to the practitioner, as well as their obvious expressed joy through smiles and laughter. The peak moment for the pair culminated in a full embrace, initiated wholly by the client (Engagement 15). The intensity of this intersubjective coming together returned her to her stereotypies and afterward she broke off contact for a short time. Remarkably, she returned to the bed and beckoned her partner to follow and to re-engage (Engagement 16). Her practitioner did so, and they resumed interactions, now sitting face-to-face. During these interactions, full narratives with moments of peak climax followed by quiet conclusions were readily apparent (Engagements 16–19). It is remarkable how quickly their intimacy developed.

However, if we compare the interactions made by this practitioner-client pair with parent-infant interactions in the first year of life, we see that the form of expression and width of expressive possibility appear narrower than we would expect an infant's to be at about four months of age. The degree of intermodal fluency appears restricted. Still, even within this narrow channel, it was possible to develop a characteristic temporal narrative course, effective enough for co-creating and sharing joy. This narrow intersubjective course is dependent on the practitioner tuning in and giving reciprocal, contingent feedback. Nonetheless, performed well, the same experiences of joy, intimacy and sharing that are available to an infant appear to be available to this autistic individual. Primary intersubjectivity remained intact.

Sensorimotor Simplicity

The sensorimotor simplicity of the expressions − a slap, rub, push − used in the dyad reduced complex anticipatory requirements. There was no complex composition of individual movements within a particular expression of the kind required for language [2]. They were primary sensorimotor actions [36] with nuances of affect conveyed by single actions with “forms of vitality” [33, 50, 51]. Their expressions were made with two simple movements of the arm, a lift up and a slap down. Further, the reciprocal turn-taking pattern of sharing meant that it was enough merely to anticipate the next expressive action of one's partner and to have poised a reciprocal re-action. Turn-taking in the dyad and practitioner's responsive posture ensured a cyclical event. This points to a deficit to do with an inability to understand and build complex sensorimotor actions, and consequently to use these for communication and social understanding [4, 36, 52].

These observations agree with experimental findings that autistic children may not anticipate the secondary consequences of preliminary actions [53, 54]. In these studies, non-autistic individuals were found to immediately anticipate the final goal at the start of an action sequence, but autistic individuals were less able to predict the final goal at the start and demonstrated anticipation only during the final motor act in the sequence. Autistic individuals did not appear to “action chain” into the prospective future, but remained in a single action world where intersubjective sympathies remained tied to anticipations of the intent of immediate actions. Extrapolation, or “action chaining,” to future possibilities beyond the single action may be compromised for individuals with autism. They may be “locked in” to single-action events and not able to see beyond them, and thus unable to socialize, or “mentalise,” beyond them. The efficacy of the therapeutic intervention shown here is arguably a matter of tuning-in to the familiar and understood sensorimotor simplicity of the client and to use these expressive acts for intersubjective sharing and companionship.

Intact Primary Intersubjectivity

Assumptions that primary intersubjectivity itself may be disrupted in autism are not supported by this analysis. Recently, Jaswal and Akhtar [55] presented a compelling argument that motivation to engage socially in meaningful ways is preserved in autism, but its means of intersubjective connection are thwarted. In many contexts, including experimental settings within psychology, primary intersubjectivity and the wish to engage socially, may appear to be disrupted artificially by the experimental context. We have shown here that when a partner attunes her behaviour to fit with the rhythms and perceptuomotor patterns of her autistic partner, primary intersubjectivity is able to flourish.

Our data support the hypothesis that disrupted communication in autism is related to a more fundamental motor disruption [16, 56, 57]. Efficient embodied communication appears disturbed, with a resulting capacity to be misunderstood [58]. Motor disruption is evident in disturbance to the subsecond kinematics of action [59] that can affect their forms of vitality in expressive communication [60, 61]. Communication difficulties may be exacerbated by sensory sensitivity issues [20, 21]. Disruption to expressive motor timing may originate from brainstem processes responsible for the subsecond timing of expressive action seen to be disrupted in children with autism [62, 63, 64]. Altogether, efficient expressive “resonance,” or primary intersubjectivity, with a neurotypical other in reciprocal shared sensorimotor interaction can be thwarted. Everyday interaction can become difficult. Neural dissonance, rather than resonance, between the two mirror neuron systems may result [18, 52, 65]. This basic social mis-attunement, due to such a temporal misalignment of the forms of expressive motor action, may thwart learning and the development of a sensorimotor intelligence shared between individuals [10, 66].

In the therapeutic context analysed here, motor imitation made with a reciprocal affective response to the other appears to “fill the gap” between solitary motor actions and shared codes that inform about what one is doing within a sequence, or narrative parcel. Observable action can be held in memory, time-bound, literal, concrete and within reach of low-functioning individuals with autism and can deliver expressions of pleasure [46, 67]. A growing body of work demonstrates the success of imitation to make contact with children and adolescents with autism and severe communicative impairments who are socially isolated [39, 41, 42, 43, 48, 68, 69]. Psychological contact mediated by imitation has been shown to reduce stereotypies, anxiety and challenging behaviours, thus affording new possibilities for action, interaction and learning. Reciprocity in this rhythmic exchange of expressive body movement is the basis of dance movement therapy known to improve social well-being in autism [70], with the potential to become elaborated in the musicality of shared meaning-making [71, 72].

This paper examined a single case of intervention by an experienced practitioner in a technique of interaction based on imitating of the affective quality made in movement with similarly toned movements in an attempt to engage and to elicit social connection. This technique and the practitioner in question is in demand in the UK and was awarded the Times-Sternberg prize for her work with autistic patients. The recognition of success of her achievement has been noted in practice, but is not as well covered the academic literature. Carers of these patients report a decrease in anxiety, stereotypies and challenging behaviours after intervention. The technique operates at the level of body movement and is entirely non-verbal, returning communication to an ontogenetic primary − a foundation of social meaning-making evident from the first days of infancy onward [4, 66].

Conclusion

This case study has shown that autism does not entirely rupture an individual's capacity for primary intersubjectivity. This young woman, regarded by carers as aggressive and psychologically distant, was able to co-create meaningful communicative exchanges in partnership with another human being whom she had just met. Such an outcome raises important theoretical questions, for it conflicts with the prediction made by the predominant cognitive accounts, which hold that a theory of mind deficit prevents autistic people from sharing mental and emotional states. The data here show that a communicative partner who used an attuned and responsive style of interaction developed intense and vibrant primary intersubjective exchanges. Further, we emphasise the fact that in our data narrative structures, a cornerstone of human meaning-making, were generated within the dyad's interactions and followed a normal, characteristic pattern. These data show primary intersubjective capacities readily emerge in the right social environment, with feeling expressed in reciprocal movement of body and voice attuned to the individual.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical permission for the use of the video footage was granted by the School of Psychology Ethics Committee, University of Dundee, in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Sources

The analysis presented here was part funded by a Danish Research Council (FKK) grant no. 09-065858 to Delafield-Butt.

Author Contributions

J.T.D.-B., M.S.Z., S.H., and M.S.V.: conceived the study. P.C.: produced the video data and carried out the interaction analysed here. J.T.D.-B., S.H., and M.S.V.: developed the narrative analysis. J.T.D.-B.: carried out the narrative analysis. S.H. and M.S.V.: carried out the descriptive analysis. J.T.D.-B.: wrote the paper with all co-authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our colleagues and students for feedback on this paper and especially Colwyn Trevarthen for discussions and insight into the narrative nature of non-verbal communication.

verified

References

- 1.Bruner JS. Acts of Meaning. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trevarthen C, Delafield-Butt JT. Biology of Shared Meaning and Language Development: Regulating the Life of Narratives. In: Legerstee M, Haley D, Bornstein M, editors. The Infant Mind: Origins of the Social Brain. New York: Guildford Press; 2013. pp. pp. 167–99. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutto DD. Narrative and Understanding Persons. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement. 2007;60:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delafield-Butt JT, Trevarthen C. The ontogenesis of narrative: from moving to meaning. Front Psychol. 2015 Sep;6:1157. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malloch S, Trevarthen C, editors. Communicative Musicality: Exploring the basis of human companionship. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trevarthen C. Musicae Scientiae. Special Issue Rhythms, Musical Narrative, and the Origins of Human Communication; 1999. Musicality and the Intrinsic Motive Pulse: Evidence from human psychobiology and infant communication. pp. pp. 157–213. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malloch S. Musicae Scientiae. Special Issue Rhythms, Musical Narrative, and the Origins of Human Communication; 1999. Mothers and infants and communicative musicality. pp. pp. 29–57. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gratier M, Trevarthen C. Musical Narratives and Motives for Culture in Mother-Infant Vocal Interaction. J Conscious Stud. 2008;15:122–58. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delafield-Butt J, Adie J. The Embodied Narrative Nature of Learning: nurture in school. Mind Brain Educ. 2016;10((2)):14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trevarthen C, Delafield-Butt JT, The Infant's Creative Vitality . In: Projects of Self-Discovery and Shared Meaning: How They Anticipate School, and Make It Fruitful, in International Handbook of Young Children's Thinking and Understanding. Robson S, Quinn SF, editors. Abingdon, Oxfordshire & New York: Routledge; 2015. pp. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Negayama K, Delafield-Butt JT, Momose K, Ishijima K, Kawahara N, Lux EJ, et al. Embodied intersubjective engagement in mother-infant tactile communication: a cross-cultural study of Japanese and Scottish mother-infant behaviors during infant pick-up. Front Psychol. 2015 Feb;6:66. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank B, Trevarthen C. Intuitive meaning: Supporting impulses for interpersonal life in the sociosphere of human knowledge, practice, and language. In: Foolen A, et al., editors. Moving Ourselves, Moving Others: Motion and emotion in intersubjectivity, consciousness, and language. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins; 2012. pp. pp. 261–303. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baron-Cohen S. Mindblindness: An essay on autism and theory of mind. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frith U, Happé F. Autism: beyond “theory of mind”. Cognition. 1994 Apr-Jun;50((1-3)):115–32. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hobson RP. Autism and the development of mind. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trevarthen C, Delafield-Butt JT. Autism as a developmental disorder in intentional movement and affective engagement. Front Integr Nuerosci. 2013 Jul;7:49. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher S. Understanding Interpersonal Problems in Autism: Interaction Theory as An Alternative to Theory of Mind. Philos Psychiatry Psychol. 2004;11((3)):199–217. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oberman LM, Ramachandran VS. The simulating social mind: the role of simulation in the social and communicative deficits of autism spectrum disorders. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:310–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams JH, Whiten A, Singh T. A systematic review of action imitation in autistic spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004 Jun;34((3)):285–99. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000029551.56735.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogdashina O. Sensory Perceptual Issues in Autism and Aspergers Syndrome: Different Sensory Experiences, Different Perceptual Worlds. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers SJ, Ozonoff S. Annotation: what do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005 Dec;46((12)):1255–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson AE, Simmons DR. The relationship between sensory sensitivity and autistic traits in the general population. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013 Apr;43((4)):775–84. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook J. From movement kinematics to social cognition: the case of autism. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016 May;371((1693)):371. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stern DN. A micro-analysis of mother-infant interaction: behaviors regulating social contact between a mother and her three-and-a-half-month-old twins. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1971;10((3)):507–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61752-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trevarthen C. Descriptive Analysis of Infant Communication Behavior., in Studies in Mother-Infant Interaction. In: Schaffer H.R., editor. The Loch Lomond Symposium. London: Academic Press; 1977. pp. p. 227–270. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stern, D.N., The Interpersonal World of the Infant. New York: Basic Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trevarthen C. The concept and foundations of intersubjectivity. In: Braten S, editor. Intersubjective Communication and Emotion in Early Ontogeny. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. pp. 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tronick EZ. Why is connection with other so critical? The formation of dyadic states of consciousness and the expansion of individuals' states of consciousness: Coherence governed selections and the co-creation of meaning out of messy meaning making. In: Nadel J, Muir D, editors. Emotional Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. pp. 293–316. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trevarthen C, Aitken KJ, Vandekerckhove M, Delafield-Butt J, Nagy E. Developmental Psychopathology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2006. Collaborative Regulations of Vitality in Early Childhood: Stress in Intimate Relationships and Postnatal Psychopathology; pp. pp. 65–126. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trevarthen C, Delafield-Butt JT, Schögler B. Psychobiology of Musical Gesture: Innate Rhythm, Harmony and Melody in Movements of Narration. In: Gritten A, King E, editors. Music and Gesture II. Aldershot: Ashgate; 2011. pp. pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delafield-Butt J. The Emotional and Embodied Nature of Human Understanding: Sharing narratives of meaning. In: Trevarthen C, Delafield-Butt J, Dunlop AW, editors. The Child's Curriculum: Working with the natural voices of young children. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meltzoff AN, Moore MK. Imitation of facial and manual gestures by human neonates. Science. 1977 Oct;198((4312)):75–8. doi: 10.1126/science.198.4312.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stern DN. Vitality Contours: The temporal contour of feelings as a basic unit for constructing the infant's social experience. In: Rochat P, editor. Early Social Cognition: Understanding others in the first months of life. London: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1999. pp. pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 34.St Claire C, Danon-Boileau L, Trevarthen C. Signs of autism in infancy: Sensitivity for rhythms of expression in communication. In: Acquarone S, editor. Signs of Autism in Infants: Recognition and Early Intervention. London: Karnac Books; 2007. pp. pp. 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trevarthen C, Daniel S. Disorganized rhythm and synchrony: early signs of autism and Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 2005 Nov;27(Suppl 1):S25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delafield-Butt JT, Gangopadhyay N. Sensorimotor intentionality: the origins of intentionality in prospective agent action. Dev Rev. 2013;33((4)):399–425. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruner JS. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Read SJ, Miller LC. Stories are fundamental to meaning and memory: For social creatures, could it be otherwise? In: Wyer RS, Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story., editor. Advances in social cognition. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1995. pp. pp. 139–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caldwell P. Finding You, Finding Me: Using Intensive Interaction to get in touch with people whose severe learning disabilities are combined with autistic spectrum disorder. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nind M. Intensive Interaction and autism: A useful approach? Br J Spec Educ. 1999;26((2)):96–102. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeedyk MS, Caldwell P, Davies C. How rapidly does Intensive Interaction promote social engagement for adults with profound learning disabilities? Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2009;24((2)):119–37. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caldwell P. Crossing the Minefield: Establishing safe passageway through the sensory chaos of autistic spectrum disorder. Brighton: Pavilion Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caldwell P, Bradley E, Gurney J, Heath J, Lightowler H, Richardson K, et al. Responsive Communication: Combining attention to sensory issues with using body language (intensive interaction) to interact with autistic adults and children. London: Pavilion; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malloch S, Trevarthen C. Musicality: Communicating the vitality and interests of life. In: Malloch S, Trevarthen C, editors. Communicative Musicality: Exploring the basis of human companionship. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Field T, Field T, Sanders C, Nadel J. Children with autism display more social behaviors after repeated imitation sessions. Autism. 2001 Sep;5((3)):317–23. doi: 10.1177/1362361301005003008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nadel J. Infancy and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. How Imitation Boosts Development; p. p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stephens CE. Spontaneous imitation by children with autism during a repetitive musical play routine. Autism. 2008 Nov;12((6)):645–71. doi: 10.1177/1362361308097117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeedyk M, Heimann M. Imitation and socio-emotional processes: implications for communicative development and interventions. Infant Child Dev. 2006;15((3)):219–21. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heimann M. Imitation and mind-reading: two connected or disconnected abilities? Int J Psychol. 2004;39:351–351. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stern DN. Forms of Vitality. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Køppe S, Harder S, Væver M. Vitality Affects. Int Forum Psychoanal. 2008;•••:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gallese V. Intentional attunement: a neurophysiological perspective on social cognition and its disruption in autism. Brain Res. 2006 Mar;1079((1)):15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boria S, Fabbri-Destro M, Cattaneo L, Sparaci L, Sinigaglia C, Santelli E, et al. Intention understanding in autism. PLoS One. 2009;4((5)):e5596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cattaneo L, Fabbri-Destro M, Boria S, Pieraccini C, Monti A, Cossu G, et al. Impairment of actions chains in autism and its possible role in intention understanding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007 Nov;104((45)):17825–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706273104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jaswal VK, Akhtar N. Being versus appearing socially uninterested: challenging assumptions about social motivation in autism. Behav Brain Sci. 2019;42:e82. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X18001826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delafield-Butt JT, Trevarthen C. Theories of the development of human communication. In: Cobley P, Schultz P, editors. Theories and Models of Communication. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton; 2013. pp. pp. 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fournier KA, Hass CJ, Naik SK, Lodha N, Cauraugh JH. Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: a synthesis and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010 Oct;40((10)):1227–40. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0981-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Delafield-Butt J, Trevarthen C, Rowe P, Gillberg C. Being misunderstood in autism: the role of motor disruption in expressive communication, implications for satisfying social relations. Behav Brain Sci. 2019;42:e86. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cook JL, Blakemore SJ, Press C. Atypical basic movement kinematics in autism spectrum conditions. Brain. 2013 Sep;136((Pt 9)):2816–24. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gallese V, Rochat MJ. Forms of Vitality: Their Neural Bases, Their Role in Social Cognition, and the Case of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Psychoanal Inq. 2018;38((2)):154–64. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Di Cesare G, De Stefani E, Gentilucci M, De Marco D. Vitality Forms Expressed by Others Modulate Our Own Motor Response: A Kinematic Study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017 Nov;11:565. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bosco P, Giuliano A, Delafield-Butt J, Muratori F, Calderoni S, Retico A. Brainstem enlargement in preschool children with autism: results from an intermethod agreement study of segmentation algorithms. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019 Jan;40((1)):7–19. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Delafield-Butt J, Trevarthen C. On the Brainstem Origin of Autism: Disruption to Movements of the Primary Self. In: Torres E, Whyatt C, editors. Autism: The Movement Sensing Perspective. Taylor & Francis CRC Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anzulewicz A, Sobota K, Delafield-Butt JT. Toward the Autism Motor Signature: gesture patterns during smart tablet gameplay identify children with autism. Sci Rep. 2016 Aug;6((1)):31107. doi: 10.1038/srep31107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams JH, Whiten A, Suddendorf T, Perrett DI. Imitation, mirror neurons and autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001 Jun;25((4)):287–95. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trevarthen C, Delafield-Butt JT. Development of Consciousness. In: Hopkins B, Geangu E, Linkenauger S, editors. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Child Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017. pp. pp. 821–35. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nadel J. Does imitation matter to children with autism? In: Roger S, Williams J, editors. Imitation and the development of the social mind: Lessons from typical development and autism. New York: Guilford Publications; 2006. pp. pp. 118–37. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nadel J. Perception-action coupling and imitation in autism spectrum disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015 Apr;57(Suppl 2):55–8. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zeedyk S. Promoting social interaction for individuals with communication impairments. null. Vol. null. 2008. null.

- 70.Koch SC, Mehl L, Sobanski E, Sieber M, Fuchs T. Fixing the mirrors: a feasibility study of the effects of dance movement therapy on young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2015 Apr;19((3)):338–50. doi: 10.1177/1362361314522353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Daniel S. Loops and Jazz Gaps: Engaging the Feedforward Qualities of Communicative Musicality in Play Therapy with Children with Autism. Arts Psychother. 2019;65:101595. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nielsen JB, Holck U. Synchronicity in improvisational music therapy − Developing an intersubjective field with a child with autism spectrum disorder. Nord J Music Ther. 2019;•••:1–20. [Google Scholar]