Abstract

The existential crisis of nihilism in schizophrenia has been reported since the early days of psychiatry. Taking first-person accounts concerning nihilistic experiences of both the self and the world as vantage point, we aim to develop a dynamic existential model of the pathological development of existential nihilism. Since the phenomenology of such a crisis is intrinsically subjective, we especially take the immediate and pre-reflective first-person perspective's (FPP) experience (instead of objectified symptoms and diagnoses) of schizophrenia into consideration. The hereby developed existential model consists of 3 conceptualized stages that are nested into each other, which defines what we mean by existential. At the same time, the model intrinsically converges with the phenomenological concept of the self-world structure notable inside our existential framework. Regarding the 3 individual stages, we suggest that the onset or first stage of nihilistic pathogenesis is reflected by phenomenological solipsism, that is, a general disruption of the FPP experience. Paradigmatically, this initial disruption contains the well-known crisis of common sense in schizophrenia. The following second stage of epistemological solipsism negatively affects all possible perspectives of experience, that is, the first-, second-, and third-person perspectives of subjectivity. Therefore, within the second stage, solipsism expands from a disruption of immediate and pre-reflective experience (first stage) to a disruption of reflective experience and principal knowledge (second stage), as mirrored in abnormal epistemological limitations of principal knowledge. Finally, the experience of the annihilation of healthy self-consciousness into the ultimate collapse of the individual's existence defines the third stage. The schizophrenic individual consequently loses her/his vital experience since the intentional structure of consciousness including any sense of reality breaks down. Such a descriptive-interpretative existential model of nihilism in schizophrenia may ultimately serve as input for future psychopathological investigations of nihilism in general, including, for instance, its manifestation in depression.

Keywords: Existential model of nihilism, Phenomenological psychopathology, Nihilism in schizophrenia, Nihilistic delusions, Schizophrenia, Nihilism

Introduction

Like death and ecstasy […], schizophrenia has often seemed a limit-case of human existence, something suggesting an almost unimaginable aberration: the annihilation of consciousness itself. ([1], p. 3)

Nihilism is one of the most extreme existential experiences in schizophrenia as it goes far beyond the notion of a meaningless life as one source of suicide. Instead, it consists of the experience that ultimately the individual's self and the world do no longer exist, which renders meaningless the existence itself, and in some individuals, even the option of suicide. In her first-person account, Kean [2] offers a narrative description of this very experience: “When I believed I did not exist, nothing else mattered to me. Even suicide meant nothing to me − I am not real, I do not exist, so it does not matter if this nonexistent self dies.”

The subjective severance of both the self's and the world's unification in schizophrenia has been addressed since the beginning of the twentieth century. Such existential experiences were already captured by German psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883–1969): he investigated this topic mainly on psychological and philosophical grounds within his book Psychologie der Weltanschauungen (Psychology of Worldviews) [3]. Existential nihilism in neuropsychiatric disorders of the schizophrenia spectrum was subsumed by Jaspers as der absolute Nihilismus in Psychosen (absolute nihilism in psychoses): within this existential state, nothing truly exists anymore: all human beings are dead; the world does not exist anymore; the individual itself is a mere quasi-existence; and nothing contains true values anymore [3]. In his earlier book General Psychopathology, Jaspers likewise stated that “[…] nihilism and skepticism can only be experienced in absolute perfection in psychoses. The nihilistic delusion of the melancholic is an ideal type: the world is no longer, the sick person is no longer.” ([4], p. 247).

Thereafter, precisely in the middle of the twentieth century, Scottish psychiatrist Ronald D. Laing (1927–1989) famously emphasized a most profound disturbance of schizophrenia that he labeled “ontological insecurity” as part of his existential-phenomenological theory [5, 6]. In Laing's view [5], the schizophrenic individual is principally affected by the loss of Heidegger's [7] notion of “In-der-Welt-sein” (being-in-the-world). The latter is the natural and most basal feeling of belonging to one's own body and of being rooted in the world, which is usually taken for granted in healthy subjects, hence providing them with “ontological security.” On the contrary, schizophrenic individuals lose ontological security as they eventually face a split between their individual's self-consciousness on the one hand and their body and the world on the other hand. Consequently, an existential disruption between the individual's self-consciousness and the natural world along with other living beings emerges [5, 6, 8, 9]. The schizophrenic individual experiences his self as detached and isolated from both body and world; in most extreme instances, this accounts for the experience of death of the self and, even more extreme, annihilation of the existence of the world as such [5, 8, 9].

Present-day phenomenological psychopathology [10] focuses on the experience of both self and world in schizophrenia [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21]. Especially, Danish psychiatrist Josef Parnas (1950-) approaches these extreme experiences of schizophrenic individuals [14, 22, 23, 24, 25]. For instance, Parnas presents the following quotations of solipsistic experiences in schizophrenic individuals: “The patient does not feel fully awake or conscious: ‘I have no consciousness'; ‘My consciousness is not as whole as it should be'; ‘I am simply unconscious'; ‘I am half-awake'; ‘I have no self-consciousness'; ‘My I-feeling is diminished'; ‘My I is disappearing for me'; ‘My feeling of consciousness is fragmented'; ‘It is a continuous universal blocking’” ([22], p. 225). Analogously, Sass [20] consistently describes schizophrenia including its heavily altered self-consciousness as an existential disorder affecting the individual's “ontological existence/dimension,” which converges with Parnas and Henriksen who present the disrupted self in schizophrenia congruently as “a basic sense of being ontologically different (different in kind) or of living in another ontological dimension.” ([14], p. 253).

Synthesizing and extending the current literature, we aim to provide a truly existential account of nihilism in specifically schizophrenia (whereas we do not consider other forms of nihilism as in depression). Without reasoning in detail, we determine the notion of existential by distinct stages: (1) the phenomenological stage that concerns the experience or consciousness of self and world, (2) the epistemological stage as featured by knowledge about self and world, and (3) an ontological stage about one's existence and reality in the world. Based on this notion of existential as including experience, knowledge, and existence, our aim to develop a 3-stage model of existential nihilism in schizophrenia that reaches beyond the so often reported solipsistic experience [12, 22, 26, 27, 28]. The phenomenological descriptions introduced above hereby acquire a supporting role in establishing our existential framework. Concerning this matter, a fundamental aspect is to emphasize that our model of nihilism in schizophrenia principally focuses on the subjectivity of the individual's annihilation. Nihilism, therefore, is neither understood as an objective nor quasi-objective feature, and its existential dimension is principally unexplainable from a scientific-empirical third-person perspective (TPP). Conversely, the experience of nihilism is intrinsically bound and interwoven into subjectivity, especially into immediate, pre-reflective experiences and feelings, in such a way that an existential framework is consequently required.

We specifically propose 3 conceptual stages regarding the pathological development to the final occurrence of comprehensive nihilism. To achieve this aim, the already well-established phenomenological concept of the “self-world structure” [12, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29] serves as starting point for our model. Our article contains a slightly distinct interpretation of the self-world structure in the section Self-Consciousness as Constituted by the Ecological Self-World Structure, followed by an overview of the 3-fold existential model of nihilism in the section Existence and Being-In-The-World − Phenomenological, Epistemological, and Ontological Stages. Finally, the sections Initial Phenomenological Solipsism toward the Self and the Environment; Phenomenological Solipsism: What Is Disrupted; Phenomenological Solipsism: Experience of Self; Phenomenological Solipsism: Experience of World; Phenomenological Solipsism: What Is Preserved; Expanding from Experience to Knowledge: Epistemological Solipsism toward the Self and the World; Epistemological Solipsism: What Is Disrupted; Epistemological Solipsism: Experience of Self; Epistemological Solipsism: Experience of World; Epistemological Solipsism: Fragmentation of Temporality; Epistemological Solipsism: What Is Preserved; and Existential-Ontological Nihilism: Annihilation of Self-Consciousness individually present the 3 distinct stages of nihilism.

Overview − Self-World Structure and a 3-Stage Existential Model of Schizophrenia Nihilism

Self-Consciousness as Constituted by the Ecological Self-World Structure

Phenomenological psychopathology offers the concept of the “self-world structure/relationship/polarity” [12, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29]. The self-world structure is the necessary predisposition of healthy self-consciousness toward the individual's experience of its self, that is, any form of the sense of self as well as toward the environment: objects, living beings, and general phenomena of the surrounding natural life-world. The self-world structure consequently reveals that the healthy self is intrinsically linked and depended not just on the person and body, accounting for embodiment [5, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36], but equally on the environment or world by default within subjectivity [21, 29, 37]. Accordingly, neither the healthy self can exist without the perceptual presence of environmental phenomena as part of the natural world, nor healthy environmental perception can exist without a sufficient level of self-consciousness. Self and world are intrinsically merged in the co-constitution of both ourselves and the world within our experience.

This notion of an intrinsically unified self-world structure as ecological co-constitution of self-consciousness is widely shared by phenomenology in general [36, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42] and phenomenological psychopathology in particular [16, 24, 37, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47]. Even when we experience our self, that is, self-consciousness, the world is always already there in the background of our experience, in essentially a pre-reflective form. Moran accordingly elucidates that “Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, and Merleau-Ponty all characterize human intentional existence as transcendence towards the world, presenting subjectivity as essentially running beyond itself, world-disclosing, and sense-giving.” ([48], p. 597). In the same respect, Merleau-Ponty ([36], p. 430) states that “subject and object are two abstract moments of a unique structure which is presence” and that “[…] there is no ‘inner man,’ man is in and toward the world, and it is in the world that he knows himself.” ([49], p. xii). Contemporary philosopher Dan Zahavi correspondingly declares that “when looking at a concrete life experience we will consequently come across a co-givenness of self and world” ([47], p. 300) and that “it is this intentional life that is at one and the same time self-involving and world-disclosing. This involvement already occurs pre-reflectively and must be considered as essential and constitutive feature of experience.” ([47], p. 300). Zahavi presents a passage where Heidegger elucidates the phenomenological intrinsic unification of the self and world: “Self and world belong together in the single entity, the Dasein, Self and world are not two beings, like subject and object, or like I and thou, but self and world are the basic determination of the Dasein itself in the unity of the structure of being-in-the-world.” ([42], p. 29–30). Concluding the above, intentionality can be considered in the light that consciousness is a structural-relational phenomenon between conscious acts and their respective intentional objects [42, 50]. This is supplementary mirrored in a broader framework of relational conjunction between the self and the world.

It shall be recognized that the hereby considered phenomenological notion of the self refers to the “experiential, core, basic, or minimal self” [21, 29, 40, 41, 47, 51, 52] that is not a higher reflected and declarative-narrative level or even specific substance of the self, for example, the self as an ontological entity or distinct “object” within phenomenal experience, but instead a most fundamental aspect of conscious experience, which is always pre-reflectively present in healthy subjects, termed as “mineness or ipseity” [14, 21, 40, 53, 54] or as “what-it-is-like-for-me-ness” [55] within the first-person perspective's (FPP) “stream of consciousness” as James [56] labeled it.1 Such experiential, core, or minimal self with the self as fundamental aspect of conscious experience on the existential-phenomenological level is well compatible with the “basis model of self-specificity (BMSS)” [57] that conceives the self as a basic biological and ultimately ontological feature of the brain's relationship to the world, namely world-brain relation [57, 58]. This further underlines the intrinsically ecological nature of both the existence of self and our experience of that very same existence of self.

Existence and Being-in-the-World − Phenomenological, Epistemological, and Ontological Stages

The possible variation of the self-world structure to unilateral extremes, namely toward either the self or the world, becomes remarkably obvious within the experience of schizophrenic individuals. In this regard, 3 very insightful first-person accounts about the nihilistic crisis in schizophrenia are provided by Kean [2, 59] (now Humpston [60]). Since we understand nihilism as the intrinsically existential experience of “nothingness” rather than an objective feature, its investigation necessarily requires the inclusion of and reliance on FPP accounts. This is in conformance with Laing, who stated that “[…] schizophrenics have more to teach psychiatrists about the inner world than psychiatrists their patients.” ([6], p. 91). Given our primarily existential framework, we deem it necessary to flesh the existential experiences of the person themselves, and this is paradigmatically reflected in our case report. That is even more so given the lack of phenomenological accounts of specifically nihilism in the current literature.

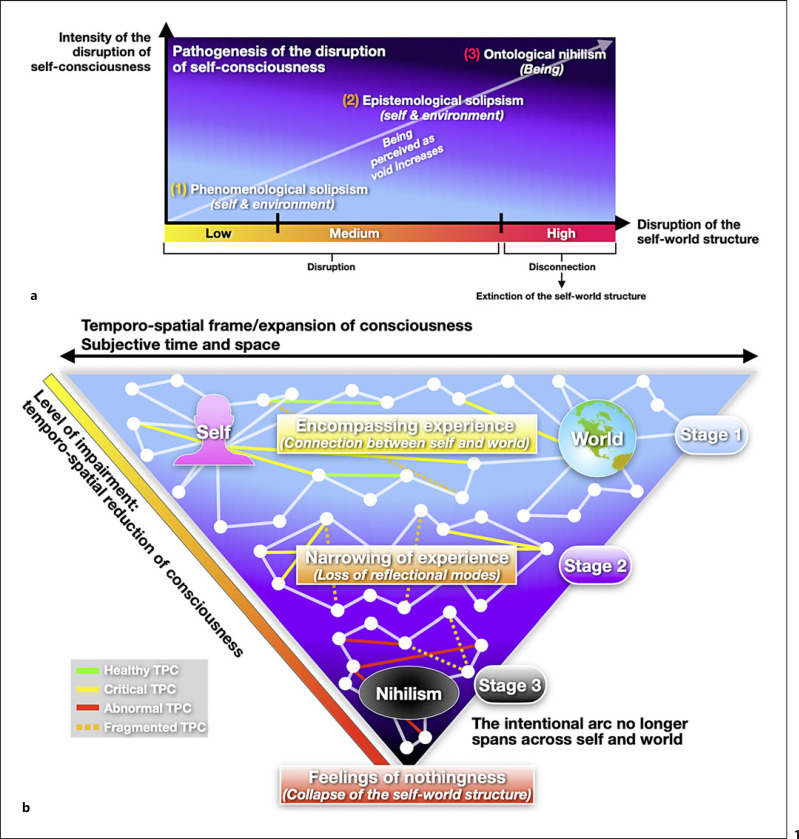

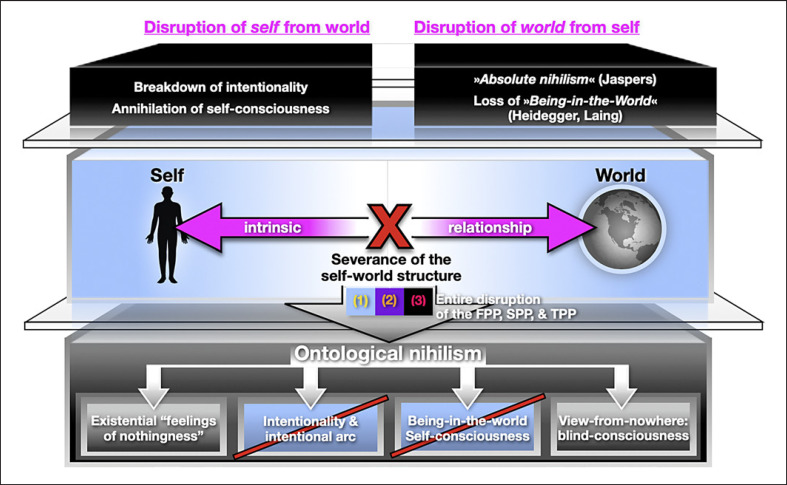

In combination with the corresponding phenomenological concept of self-world structure, we now elaborate that first-person accounts allow the deduction of a 3-stage existential model containing a quantitative transition from the phenomenological over the epistemological to the ontological stages of our existential framework. Initiating phenomenological solipsism toward the self and further expanding toward the environment are not all-or-nothing phenomena. Instead, we conceive nihilism in schizophrenia to be located on a continuum with smooth transitions between the 3 stages of our model of existence, that is, phenomenological, epistemological, and ontological. This 3-stage model (shown in Fig. 1) contains the subsequent stages that follow the trajectory from experience over knowledge to Being: (1) phenomenological solipsism toward the self and the environment; (2) epistemological solipsism toward the self and the environment; and (3) finally, existential-ontological nihilism regarding Being. The intrinsically subjective nature of existential nihilism reaches beyond traditional frameworks and phenomenological concepts in general and phenomenological psychopathology in particular. Consequently, it is indispensable to nest yet differentiate the first phenomenological and second epistemological stages from the final existential-ontological stage. While the first 2 stages already anticipate the third stage, it is the latter that will ultimately represent the attempt to indicate a fully developed existential nihilism.

Fig. 1.

a A quantitative transition is suggested to apply for the pathological development of self-consciousness toward the final occurrence of nihilism in schizophrenic individuals. This transition initiates with phenomenological gaps toward the self and the environment. Later, phenomenological solipsism expands toward the self and the environment including all its objects and living beings into the deeper epistemological stage. This transition ultimately reaches the more extreme characteristic of ontological nihilism concerning the annihilation of the self and the world, that is, Being, and hence the most fundamental stage of existence. b Subjective time and space: the temporo-spatial frame or extension of consciousness increasingly shrinks from stage 1, over stage 2, to stage 3 as the pathological development proceeds. On a most fundamental level of Being, conscious experience consists of TPCs between the self and the world. While healthy TPCs exist aside critical and fragmented ones in stage 1, the balance continuously shifts to abnormal TPCs as in stage 3. In stage 3, nihilism is associated with the severance of the self-world structure, since the intentional arc, reflected by the white TPCs including their interconnected lines, no longer properly spans across both the self and the world. TPCs, temporo-spatial connections.

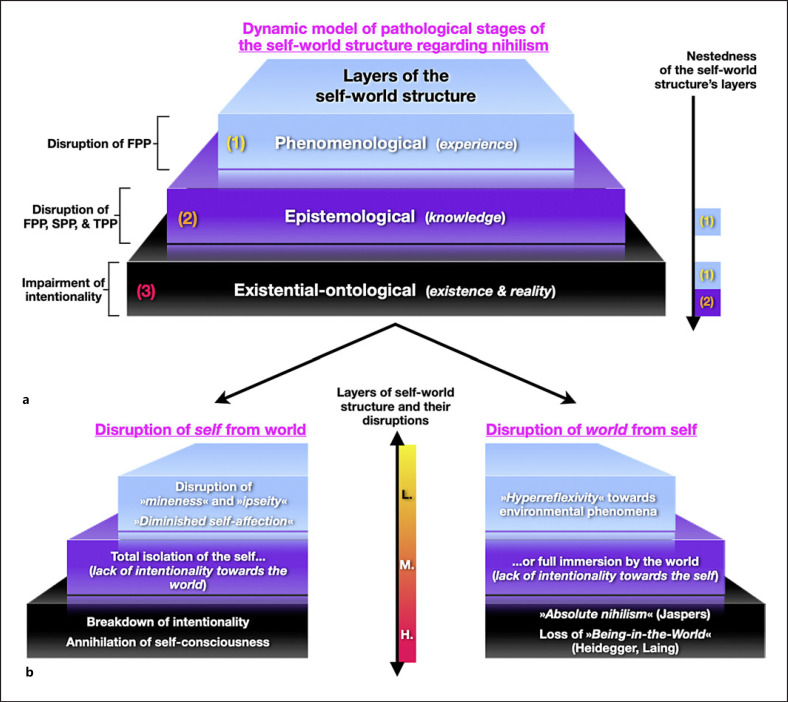

It requires specification that a schizophrenic individual does not simply jump from one stage to the next, which would reflect a categorical-qualitative transition; instead, a fluid, continuous, and graded pathological development exists, which only on the conceptual-descriptive and interpretative level of our existential framework is definable by these 3 stages. Such a conceptual model necessarily comes with certain simplifications of the affected individuals' phenomenological and existential reality. Bridging the gap between phenomenological concepts and first-person accounts of existential nihilism, this attempt tentatively advances the self-world structure by suggesting 3 nested stages: each previous stage is contained within the underlying next stage. The top surface is reflected by the phenomenological stage that is nested within the underlying epistemological and ontological stages. The phenomenological and the epistemological stages are both nested within the most fundamental existential-ontological stage. Such nestedness allows deepening the 3 stages of nihilistic development in schizophrenia by additionally incorporating their dynamic pathological development.

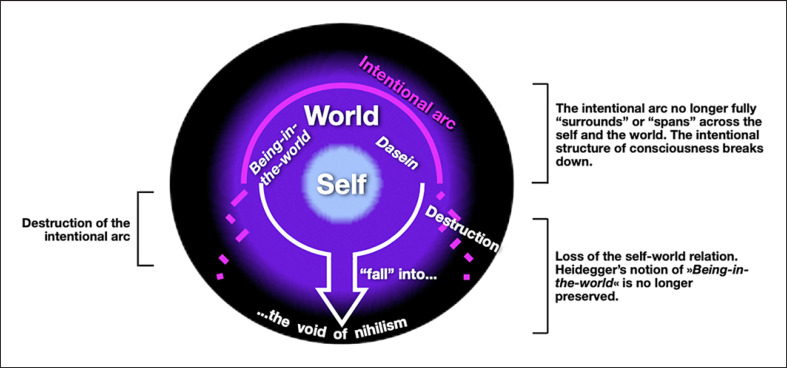

Disruptions of the Self-World Structure in Schizophrenia: From Phenomenological Solipsism of Self and World to Existential-Ontological Nihilism of Being

First and foremost, it is important to note that the pathogenesis in schizophrenia negatively affects both sides of the self-world structure: this is reflected by the phenomenal experience of the self (the mineness, ipseity, or for-me-ness of experience) and of the world (object-directed intentionality) on all its distinct 3 stages and respective stages (shown in Fig. 2). In consideration of the self's and world's sides of disruption, it has to be noted that since self and worldly experiences are intrinsically united, they are 2 sides of the same underlying disruption.

Fig. 2.

a The self-world structure is tentatively advanced by suggesting 3 distinct stages that elucidate and deepen the dynamic pathological development to the final occurrence of nihilism in schizophrenia. The upper part displays an overview of the general nestedness of the 3 distinct stages. Within the pathogenesis of nihilism in schizophrenia, initially, experience is negatively affected. Second, in addition to experience, the more far-reaching epistemological layer of principal knowledge is likewise negatively affected, and finally, self-consciousness faces its approximate annihilation, as reflected by the most fundamental existential-ontological stage. b Although both self and world are tightly interwoven within phenomenology, that is, they cannot be dissociated in healthy subjects, a conceptual-explanatory separation displays their individual disruptions in all 3 stages.

Generally, the first stage exhibits a disruption of the FPP, which is pre-reflective self-consciousness, while the second-person-perspective (SPP) and TPP of intersubjectivity and reflection are yet preserved. Within the second epistemological stage, the SPP and TPP are additionally impaired to the FPP. The impairment of the SPP and TPP concerns reflective self-consciousness, that is, the level of what can be experienced and known in principle about both the self and world. Reflective or non-immediate perspectives of experience are then relatively, that is, up to a certain degree, epistemologically excluded. Paradigmatically, the affected individual cannot consistently and outright contemplate upon her/his state of mind anymore but is exclusively bound to immediate pre-reflective experience. Holistic reflection about either the self or the world, therefore, is no longer possible. All 3 possible perspectives are intrinsically interwoven in subjectivity and intersubjectivity.

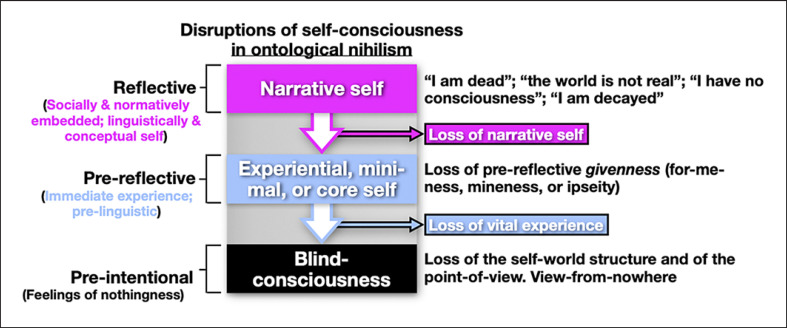

Finally, the intentional structure of self-consciousness is fundamentally impaired within what we conceive as the annihilation of self-consciousness in the third existential-ontological stage. Within this final stage, the individual experiences and especially feels annihilation of existence and reality concerning both the self and the world. Doubting existence and reality in this final stage is not mediated within a TPP's reflection; instead, such annihilation sets the existential background in an immediate, pre-reflective, and pre-intentional fashion. In other words, the individual feels comprehensive annihilation of both the self and its relation to the world that is prelinguistic and therefore existential.

Beyond Experience and the Phenomenological Method − Need for an Existential Approach

Impairments of self-consciousness that lead to nihilism, including the reduction of the intentional arc and its associated minimization of the temporo-spatial expansion of consciousness (see section Ontological Nihilism: Temporo-Spatial Reduction of the Intentional Arc), require a framework that includes phenomenology, yet goes beyond ideal-typical phenomenological concepts and limitations. This is due to the fact that phenomenology conceives the intentional structure of consciousness as always and principally given for one's experience [1, 21, 29, 40, 41, 47, 51, 52]. Accordingly, within the boundaries of the phenomenological framework, one cannot go beyond the notion of the “minimal self” for healthy subjects to provide a more comprehensive understanding of our proposal that the schizophrenic individual loses his self. This understanding stands in opposition to simplified characterizations of such experiences as mere psychotic delusions by objectified classificatory systems in modern psychiatry.

It was Laing, already in the year 1967, who criticized this viewpoint, which still represents present-day daily routine in psychiatry, where simplified diagnoses are conceived to be literally true entities. The schizophrenic individual faces a situation where the therapist may lack genuine interest in his subjective life-world. Criteria and labels are then applied that further inhibit deepening access into the patient's inner world to provide an interpersonal understanding of his existential dimension and experience of life. Such constellations between the therapist and the patient were described and criticized by Laing: “A feature of the interplay between psychiatrist and patient is that the patient's part is taken out of context, as is done in the clinical description, it might seem very odd. The psychiatrist's part, however, is taken as the very touchstone for our common-sense view of normality. The psychiatrist, as ipso facto sane, shows that the patient is out of contact with him. The fact that he is out of contact with the patient shows that there is something wrong with the patient, but not with the psychiatrist. But if one ceases to identity with the clinical posture, and looks at the psychiatrist-patient couple without such presuppositions, then it is difficult to sustain this naive view of the situation.” ([6], p. 89–90).

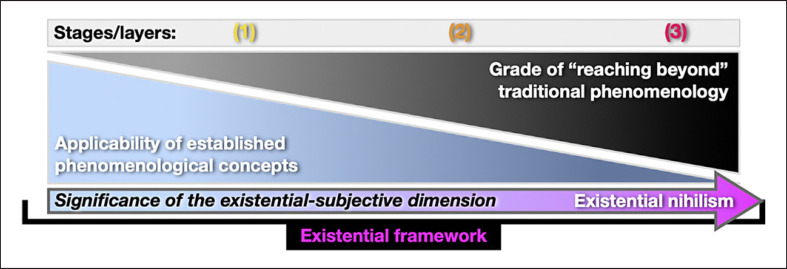

We argue that precisely this step, partially going beyond conceptual limitations to take the schizophrenic individual's experience seriously, is required to better account for the extreme experiences and feelings that converge into existential nihilism. The aforementioned clarifies why eminently the third and ultimate stage is fundamental in the sense that it tries to capture the existential dimension of nihilism, that is, the severance of the self-world structure, for example, by highlighting the role of pre-intentional “existential feelings” [16, 17, 18] (Fig. 3). Table 1 provides further understanding of our main concepts and terms that we use throughout the article.

Fig. 3.

The relationship between established phenomenological concepts, for example, by phenomenological psychopathology, and their applicability to the annihilation of self-consciousness in the final existential-ontological stage is roughly inverse. Phenomenology and phenomenological psychopathology especially offer descriptive and interpretative power regarding stages 1 and 2. The final third stage, however, requires both to include yet to go beyond the contemporary conceptual horizon of phenomenology to account for existential nihilism.

Table 1.

Overview of main concepts

| Level of intentionality | Unification of the self-world structure | Stages | Perspectives | Concepts | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intentional | Intrinsic relationship/unification | 1 | FPP, SPP, and TPP | Self-consciousness (pre-reflective and reflective) | Experience of oneself in relation to the world |

| 2 | |||||

| Pre-intentional | Severance of the relationship (fundamental impairment of the self-world structure) | 3 | Loss of a coherent point of view (“view from nowhere”) | Blind-consciousness Existential “feelings of nothingness” | Pre-intentional feelings of one's and the world's annihilation Fundamental impairment of both the intentional arc and being-in-the-world |

Existential framework: experience, knowledge, and existence. FPP, first-person-perspective; SPP, second-person-perspective; TPP, third-person-perspective.

Three-Stage Existential Model of Nihilism

Initial Phenomenological Solipsism toward the Self and the Environment

Phenomenological Solipsism: What Is Disrupted

The first and uppermost phenomenological stage initiates with the disruption of immediate and pre-reflective experience. Impaired is consequently the FPP concerning both the self and the world. As introduced in the sections Overview − Self-World Structure and a 3-Stage Existential Model of Schizophrenia Nihilism and Self-Consciousness as Constituted by the Ecological Self-World Structure, self-consciousness is ecologically co-constituted by the intrinsically unified self-world structure. Any disruption of the self's side also entails a disturbance of the world's side and vice versa, that is, the subjective experience and general perception of the natural environment and one's position within. The disruption of the FPP entails corrosive effects on specific phenomenological features. In that matter, we suggest that precisely the “mineness” or “ipseity” of experience suffers.

Phenomenological psychopathology traditionally subsumes such disruptions under the core disturbance of the self-disorder in schizophrenia [37, 61, 62, 63]. Self-disorders already evolve in childhood or early adolescence [64] and within the general prodromal phase of schizophrenia [65, 66]. The high temporal stability of anomalous experience in schizophrenia is reported by both first-person accounts and phenomenological psychopathology [2, 59, 67, 68]. In her narratives, Kean [59] offers insight into altered self and world-related experiences:

Despite the “usual” voices, alien thoughts and paranoia, what scared me the most was a sense that I had lost myself, a constant feeling that my self no longer belonged to me. ([59], p. 1034).

The clinical symptoms come and go, but this nothingness of the self is permanently there. Not a single drug or therapy has ever helped with such nothingness. By nothingness, I mean a sense of emptiness, a painful void of existence that only I can feel. My thoughts, my emotions, and my actions, none of them belong to me anymore. This omnipotent and omnipresent emptiness has taken control of everything. I am an automaton, but nothing is working inside me. Schizophrenia has silenced my real self, and even the observing self is biased by the process of subjective observation. ([59], p. 1034)

Emphasis is on the circumstance that self-consciousness, conceived as the relation between the self and the world, is not immediately lost. While self-consciousness preserves, it nonetheless faces initial and multiple manifestations of disintegration plus fragmentation that are captured by analyses of phenomenological psychopathology [14, 22, 23, 29] as well as by reports of first-person accounts [2, 59, 60]. Based on the previous findings above and in the Introduction, we infer that the disruption of self-consciousness seems to initially correspond to a comparatively higher top surface of the self-world structure. We define this top surface as the phenomenological stage of experience (shown in Fig. 2). It is remarkably the final stage that provides the self's existence and reality as such, forasmuch as self-consciousness is not annihilated but “solely” disturbed on this first stage (shown in Fig. 1) of pathogenesis.

Phenomenological Solipsism: Experience of Self

On the self's side of the self-world structure, the formerly named disruptions of the “mineness, for-me-ness, or ipseity” of pre-reflective self-consciousness occur. There is alterity of the “experiential” or “minimal” self as reflected by a “diminished self-affection” [14, 20, 21, 40, 53, 54, 69]. The individual's healthy ipseity deviates to alterity, manifested in the phenomenon that the FPP's immediate conscious experience is no longer intrinsically blended with the experiential self. The mineness of one's experience is consequently disrupted. It is precisely this mineness of experience that is taken for granted in healthy subjects [14, 21, 40, 53, 54].

The result is that a cardinal gap between the individual's experience and the latter's intrinsically melting connection to any sense-of-self opens up [28]. Sass [1, 69, 70, 71] additionally describes this arising phenomenological gap via the concept of “diminished self-affection”: the experiential self and its relation to its normally own mental states are no longer experienced “on-line” from a centralized and immediate point of view. Instead, one's mental states now appear to be more distant; they emerge as significantly reflected rather than immediately experienced. Hence, mental states appear somewhat dissociated within a mediated TPP's contemplation or reflection instead of being directly inherent within the FPP's pre-reflective experience. Sass compresses diminished self-affection as follows: “[…] a profound weakening of the sense of existing as a subject of awareness, as a presence for oneself and before the world” ([69], p. 244).

Phenomenological Solipsism: Experience of World

On the world's side regarding the experience of environmental phenomena including their connection to the self, that is, objects, other living beings, and social interactions within the life-world, phenomenological solipsism entails a hyper-reflective stance toward the natural world and the relation of one's self with the former, often termed as “hyperreflexivity” [1, 69, 70, 71, 72]. In a most general explanation, hyperreflexivity refers to heightened forms of self-consciousness, so that the self abnormally relates itself to external environmental phenomena. Hyperreflexivity is often linked with the reduction of self-evidence concerning ordinary, implicit, and daily-life phenomena that are normally taken for granted in healthy subjects. Conversely, ordinary phenomena now seem increasingly suspicious to the schizophrenic individual, resulting in a hyper-reflective stance. This hyper-reflective attitude can paradigmatically be observed in the tendency to overanalyze everyday social interactions and behaviors of others because people cannot be understood reasonably anymore [73]. Such alterity of and alienation from worldly experiences was famously labeled as the crisis or collapse of common sense by German psychiatrist Blankenburg [74], further described in his book Der Verlust der natürlichen Selbstverständlichkeit (The loss of natural self-understandability) [75]. Overgaard and Henriksen [76], as well as Stanghellini [77], interpret the collapse of common sense as a disturbance of pre-reflective or intuitive attunement with others and the world. Besides, considerable reflection and suspiciousness about natural and ordinary environmental phenomena do not resolve this experiential gap toward the world. It is rather the case that alienation from the world negatively increases [78]. Sass [69, 71, 72] and Sass et al. [79] frequently term the experiential gap toward and alienation from the world as decreased “grip” or “hold” on the world. In this respect, Sass [71, 72] assumes that hyperreflexivity and the associated crisis of the common sense are an inherent factor of altered self-consciousness, the “[…] vital, experiencing self, which normally serves as a constituting and orienting background for experience of the world” ([71], p. 599), is no more existent.

Phenomenological Solipsism: What Is Preserved

Abnormally altered experiences of both the self and the world conform to an initial disruption of the self-world structure. We subsume this commencing pathology under the umbrella concept of “phenomenological solipsism,” affecting the immediate and pre-reflective FPP's phenomenal experience. In contrast, the level of principal knowledge concerning the self and the world, represented by the underlying epistemological stage, is yet preserved. The prime feature of intentionality is still directed toward both the self and the world, which makes knowledge acquisition regarding both sides of the self-world structure possible. This initiating low to low-medium disruption of the FPP and of the self-world structure then converges into what is conceptualized as phenomenological solipsism toward one's self and the world (1) shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Expanding from Experience to Knowledge: Epistemological Solipsism toward the Self and the World

Epistemological Solipsism: What Is Disrupted

In the second stage of pathogenesis, the epistemological layer of principal knowledge undergoes impairments. In addition to the FPP of immediate and pre-reflective self-consciousness, the SPP and TPP of reflective self-consciousness are now affected. Choosing a rather reflective or mediated TPP necessarily requires to go beyond the temporo-spatial frame of the immediate and pre-reflective FPP. Paradigmatically, one can think of the example of time whereby an axis connects the past over the present to the future. To reflect about either the past or the future, it is required to “stretch” one's mind beyond the present moment. In other words, remembering the past and anticipating the future rely on the ability to go beyond the immediate and pre-reflective experience of the present moment − the “now.” Going beyond pre-reflective experience of the present moment (the FPP) equals to a transition from the FPP over the SPP and finally to the TPP. In the TPP, one reflects upon his self and the relation of one's self to the world; consequently, there is a certain detachment from immediate and pre-reflective experience (FPP) to reflection that is situated in the TPP. The TPP is, therefore, not understood in the sense of an “objective” perspective, for example, one that empirical sciences claim to take, but a TPP inside the borders of one's experience that is nested within subjectivity. Such possible epistemological constraints of knowledge about oneself and one's relation to the world are likewise linkable to Zahavi's (2005) notion that self-knowledge is a natural aspect of human beings in addition to the FPP of the minimal self: “What contributions do such narratives make to the constitution of the self? It has been suggested that they make up the essential form and central constitutive of self-understanding and self-knowledge. In order to know who you are, in order to gain a robust self-understanding, it is not enough to simply be aware of oneself from the FPP. It is not sufficient to think of oneself as an I; a narrative is required” ([40], p. 118). A disruption of one's ability for reflection about both the self and the world is consequently equal to abnormal epistemological limitations: in this second stage, the schizophrenic individual is primarily bound to immediate experience that does not allow for comprehensive reflections upon her or his state of mind anymore. Similarly, a deeply depressed individual can be unable to properly reflect about her/his dysfunctional beliefs. Real possibilities the individual may still encounters are no longer perceived as such; for example, the individual underestimates her or his possibilities due to the depressive state of the mind, for example, reflection upon her/his dysfunctional attributional style is no longer possible.

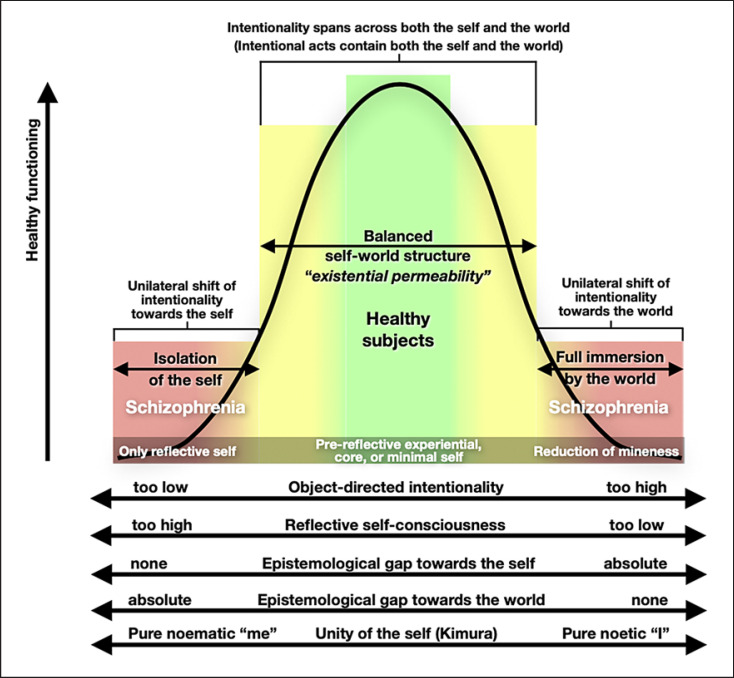

While the experience of ipseity was replaced by alterity within the first stage, the schizophrenic individual now faces 2 possible unilateral disruptions regarding the intentional structure of consciousness. The unilateral directionality of intentionality spans either (1) too heavily toward the extreme end of the self at the expense of object-directed intentionality toward the world (reflecting isolation of the self from the world), or vice versa, that is, (2) too heavily to the extreme end of the world at the expense of the self (reflecting a massive immersion by the world and a significant reduction of the experiential self). This variation of the self-world structure and its unilateral imbalances in schizophrenia are mirrored in what Kean [59] terms “existential permeability” in her narrative first-person accounts:

My view is that the key to understanding such self-disturbances lies within how one relates to the external world and how one attributes this relationship to interpreting oneself. For example, if a person relates too much to the outside world, to such an extent that he ignores his own internal self, this may result in him feeling being engulfed by others. On the other hand, if one finds little or no connection to the world, he may think that his self is going to implode and destroy him from the inside. Basically, I call this relationship existential permeability. ([59], p. 1034–1035)

In his famous book Madness and Modernism, Sass [1] describes how self-consciousness requires a balanced relation within (or distance to) the world that comparatively reflects what Kean [2, 59] labeled existential permeability. Sass states that “One must, among other things, maintain a certain optimal distance in one's experiential stance − neither coming so close to sensory or material particulars as to lose oneself in their sheer actuality, infinite minutiae, or endless mutability, nor moving so far away from particular objects or sensations as to lose touch with their conventional or practical significance.” ([1], p. 118). In schizophrenia, however, individuals deviate from a centered or balanced position within this continuum [1].

Consequently, the initial disturbance concerning the experiential self within the FPP now expands to abnormal constraints of principal knowledge (epistemology) of either the self or environmental phenomena regarding reflective consciousness of the SPP and TPP. Once intentionality approximately shifts to one of the extreme ends of the self-world structure's mutual continuum, the opposite side naturally becomes almost inaccessible. As already introduced in the sections Overview − Self-World Structure and a 3-Stage Existential Model of Schizophrenia Nihilism and Self-Consciousness as Constituted by the Ecological Self-World Structure, healthy self-consciousness, defined as a relational phenomenon, requires an ecologically constituted balance of the self-world structure, so that intentionality spans across self and world. Consequently, in the possible 2 extreme unidirectional variations of intentionality, either self or world is virtually and temporarily excluded from the individual's experience. In the account of the above and numerous phenomenological analyses, presented subsequently, it is possible to deduce the following self-world structure's quantitative continuum regarding the intentional structure of self-consciousness and its epistemological limitations in the advanced pathogenesis of schizophrenia (shown in Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The self-world structure consists of a reciprocal balance between both ends of its mutual continuum (as reflected by self and world). Alternating unilateral imbalances of the self-world structure either excessively toward the self or the world can manifest in schizophrenia. Either the world, that is, natural environmental phenomena, or the self, that is, any sense of self, consequently becomes epistemologically excluded within phenomenal experience. Under these circumstances, both the self and the world partially cannot be experienced anymore at the same time and consequently lack their respective intentional focus. The intrinsic union of self-consciousness and the self-world structure is then bygone.

Epistemological Solipsism: Experience of Self

On the self's side of the self-world structure, intentionality unilaterally shifts to the other 1-sided extreme of approximately only reflective self-consciousness. This shift leaves almost no room for healthy environmental phenomena and a corresponding sufficient amount of object-directed intentionality. Epistemological limitations of self-consciousness are potentially exemplified in the differentiation of the immediate subjective “I” as noetic and the “me” as objective noematic self by Japanese psychiatrist Bin Kimura (1931-): while the subjective “I” (noetic self) refers to the prelinguistic immediate experience of life and the world (FPP), the noematic self appears within mediated reflection (SPP and TPP). Once the ongoing immediate experience of the “I” is taken into explicit awareness, it already becomes the objective noematic self − the “me” [45]. Healthy subjects always exhibit a balanced structure between the “I” as noetic self and the “me” as noematic self, which, on the contrary, is imbalanced in schizophrenic individuals [37, 45, 80]. If the subjective pre-reflective I of one's self and worldly experiences is disordered, the reflectional objective me concerning one's phenomenology likewise gets affected on the grounds of the intrinsically structural relationship between noetic I and noematic self. Ultimately, the union of self-consciousness, which is always about the self and the world, is separated [44]. Self and world consequently cannot be perceived simultaneously any longer. This separation reflects altered epistemological limitations: the exclusion of either the self or the world and the impairment of healthy unified self-consciousness.

Epistemological Solipsism: Experience of World

In the perspective of the world's side of the self-world structure, the self is conversely “drown” in the environment since intentionality unilaterally directs toward the world. Any significant sense of self can no longer be perceived as such “on-line.” The experiential self and the mineness or for-me-ness of experience not only becomes temporarily inaccessible within the pre-reflective FPP, but likewise in the SPP of intersubjectivity and TPP concerning reflection. Two further quotations by Humpston [60] harmonize with our suggested unilateral shift of intentionality toward the world:

I thought I was dissolving into the world; my core self was perforated and unstable, accepting all the information permeating from the external world without filtering anything out. Where did my self end and where did the external world start? ([60], p. 241)

[…] when there was heightened salience from my surroundings, I would be absorbed by the external world, but my self tended to dissociate simultaneously. ([60], p. 241)

It is inferred that with a further intensification of the schizophrenic crisis, the environment temporarily and drastically vanishes. Meaningful and vivid recognition of real environmental phenomena fades. Sophisticated behavioral interactions with environmental phenomena can no longer be consciously related neither to the individual in general nor to any sense of self [54, 62] including sense of agency [81] in particular. In this respect, Henriksen et al. delineate experiences “[…] of not being fully present in the world (e.g., manifested in feelings of being ephemeral, not fully existing, lacking a core,” decreased emotional resonance and responsivity, and in a pervasively felt distance to the world) or quasi-solipsistic experiences.” ([28], p. 6). The reciprocal influence between both sides of the self-world structure crystalizes: imbalances of intentionality occur as a result of the fact that the disruption of self-consciousness entails following impairments of environmental perception since self-presence and presence in the world are 2 interwoven sides of the same underlying fundament, as reflected by the unified self-world structure [12, 21, 29]. This self-alienation from the world is also referred to as disruption of the self's merging “presence” within common human life along with the experience of distancing environmental phenomena in the world [62, 82]. In short, a phenomenological fluid attunement to the world is bygone [70]. Accordingly, the following excerpt of such experience by Kean [2] validates the formerly indicated:

My self − or someone else's self − was already out there, controlling my every move without my conscious awareness. I was trapped in the nothingness between the internal and the external, hiding behind the veil of my own perceptions, which I didn't perceive to be my own. ([2], p. 5)

As Parnas and Sass [27] declare, the self-world structure or subject-object articulation becomes blurred. Unilateral imbalances are additionally and often portrayed by phenomenological psychopathology [12, 22, 23, 24, 83], for example, as unstable or permeable boundaries between the self and others/world, so that “the patient may feel somehow transparent, without any barriers, ‘radically exposed’ or ‘as if’ fusing with others or the surroundings.” [84, 85]. Parnas et al. [54] label this the permeability of the self-world boundary, which comes very close to Kean's [2, 59] notion of existential permeability and the former quotation above:

The patient experiences himself and his interlocutor as if being mixed up or interpenetrated, in the sense that he loses his sense of whose thoughts, feelings, or expressions originate in whom. He may describe it as a feeling of being invaded, intruded upon in a nonspecific but unpleasant or anxiety-provoking way. ([54], p. 254)

Epistemological Solipsism: Fragmentation of Temporality

Additionally, affecting both self and world experiences simultaneously, altered epistemological limitations can be intrinsically linked and traceable to the often reported impairments of subjective time within the phenomenal experience of schizophrenic individuals [82, 86]. Frozen phenomenal time within schizophrenia was firstly rigorously described by French psychiatrist Eugène Minkowski (1885–1972) [87], where self-consciousness lacks its alignment to the presence in general as well as to environmental situations and phenomena in particular [86]. Up to present-day research, both phenomenological psychopathology and philosophy extensively report abnormal time experiences in schizophrenia [6, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97]. A loss of fluid temporal continuity within self-consciousness, the “inner time-consciousness” [8], is frequently reported [1, 98, 99]. “Temporal continuity” is replaced by “temporal fragmentation” of conscious time perception [88, 89], which means that a flowing and smooth transition from one perception to the other is bygone. The temporal background where all phenomenal experiences are virtually linked is impaired. Therefore, self-consciousness and connections to the environment, allowing for real interactions, that is, intentional behaviors and receptive feedback as primary dimensions of consciousness [32, 33], commence vanishing. Stanghellini et al. [100] consider the inability of perceptual immersion in the world and arising solipsism toward the former to be the main consequence of the perceptual loss of “inner time-consciousness” in schizophrenia. In conclusion, epistemological solipsism toward the self and natural environmental phenomena furthermore includes epistemological gaps toward the most basal configurations of Being. More precisely, the configuration of space and time within the inner time-consciousness of schizophrenic individuals. Pathological malfunction of inner space and time is linkable to the schizophrenic individuals formerly described experience of existing in another dimension or ontology [14, 20, 101], since the one's existence is fundamentally constituted by certain configurations of space and time.

Epistemological Solipsism: What Is Preserved

In the second stage of epistemological solipsism, all possible perspectives one can take, that is, the FPP, SPP, and TPP are ultimately impaired. Abnormal constraints of perspectives consequently include both the immediate, pre-reflective experience and principal knowledge concerning both the self and the world. What is preserved is the experience of existence itself, the feeling that one is still an existent within Being. Even though the self together with the environment is increasingly perceived to be temporally inaccessible, and a maladaptation of inner space and time to the world's space and time configuration arises, perception of existence and reality is yet maintained. There is thus a medium to medium-high disruption of self-consciousness in the epistemological stage of the self-world structure: experience is either no longer able to intentionally expand beyond the borders of the person into the environment, reflecting isolation of the self (including epistemological solipsism toward the world), nor phenomenal experience can healthily capture the natural environment, that is, by simultaneously keeping a significant sense of self via self-referential perception at the same time alive. Since existence and Being are still present in experience, the ontological stage is still preserved even in epistemological solipsism. In conclusion, this development corresponds to epistemological solipsism toward the self and the environment (2) (shown in Fig. 1, 2).

Existential-Ontological Nihilism: Annihilation of Self-Consciousness

Ontological Nihilism: Existential Outline

Nothing, as experience, arises as absence of someone or something. No friends, no relationships, no pleasure, no meaning in life, no ideas, no mirth, no money. As applied to parts of the body − no breast, no penis, no good or bad contents − emptiness. ([6], p. 32)

When reaching the ultimate stage of nihilism in schizophrenia, what possibilities exist to investigate into the FPPs intrinsically subjective nature of this unconceivable condition; notably when one tries to grasp nihilism from a healthy perspective? Is the presumption of any possibility regarding a descriptive-interpretative approach, one that does not originate from the affected individual himself, toward this existential crisis not already impossible right from its onset? We believe that one cannot appropriately describe, interpret, or even understand the “what-it-is-like,” that is, the phenomenal quality of nihilism in schizophrenia. The aim of trying to approximate the existential situation the schizophrenic individual finds her/himself in might represent the only viable option. This approximation contains the characterization of abnormally altered relations between the self and the world. Instead of directly targeting the phenomenal quality of experience and feelings (the relata or elements), which are only accessible to the affected individual, one can investigate the misbalance (as in relations and structure) and severance of the self-world structure. The severance of the latter can then be described in reference to experience.

We suggest and elaborate on the experience of nihilism by dividing the third stage into 5 subparts: (1) existential feelings of nihilism (see section Ontological Nihilism: Existential Feelings); (2) the impairment of the intentional arc (see section Ontological Nihilism: Temporo-Spatial Reduction of the Intentional Arc); (3) the annihilation of self-consciousness (see section Ontological Nihilism: The Annihilation of Self-Consciousness); (4) Christian Scharfetter's ideas on nihilism in schizophrenia (see section Ontological Nihilism: Scharfetter's Ideas on Nihilism in Schizophrenia); and (5) last, the remains of experience − the notion of “blind-consciousness” (see section Ontological Nihilism: The Remains of Experience − The Notion of “Blind-Consciousness”). The transition into the third stage is conceptualized based on the pathological increase of the former 2 stages, that is, phenomenological and epistemological solipsism. Comprehensive epistemological solipsism devours any luminous accessibility toward both one's self and the environment, so that a converging into ontological nihilism manifests. This development touches Being as the deepest stage of one's existence (shown in Fig. 1, 2). Conceptually, in the stage of ontological nihilism, the self-world structure's most fundamental ontological stage, including the nested phenomenological and epistemological layers, collapses. The comprehensive impairment of all possible perspectives concerning self-consciousness, that is, of the FPP, SPP, and TPP, entails the disruption of a coherent point of view. Metaphorically speaking, a healthy point of view transforms into a “view from nowhere.” Heidegger's [7] notion of being-in-the-world of our “Dasein” (being-there/here) within the pre-given, self-evident, and natural life-world that human beings share, interact, and practically operate in does no longer apply. An interactive, dynamic, and as Minkowski famously termed “vital contact with reality” [87], which pre-reflectively guarantees the individual's belonging to the intersubjective life-world as an immediate “lived reality” (instead of autistic and aloof reflection on the former), is transformed into an existential void of nihilism, a diminishing of the lived and intersubjective accessible reality − the “sense of reality.” We display the ultimate collapse of the self-world structure's unification in Figure 5.

Fig. 5.

The third stage of ontological nihilism corresponds to the severance of the self-world structure. Consequently, all possible perspectives of self-consciousness, that is, the FPP, SPP, and TPP, are altogether impaired. Any possible healthy point of view is therefore impaired; hence, the schizophrenic individual experiences himself as dead or decayed. Simultaneously, experience concerning the world contains its doom or that the world has vanished. FPP, first-person-perspective; SPP, second-person-perspective; TPP, third-person-perspective.

Ontological Nihilism: Existential Feelings

What is changed in nihilism is the whole background of one's existence, referring to a shift in Ratcliffe's [16] notion of “existential feelings.” How can we shortly introduce and link existential feelings with nihilism? First, existential feelings undermine the frequently observed artificial dissociation between the concepts of self/body-world; internal/mind-external/world; subject-object; and cognitive-affective.2 Instead, existential feelings are the “background orientations through which experience as a whole is structured.” ([16], p. 38). Second, existential feelings are bodily feelings concerning the relatedness to the world containing the sense of reality regarding one's being-in-the-world. According to Ratcliffe [16], background feelings, that is, existential feelings, are bodily feelings and at the same time feelings of worldly phenomena, since it is the body that feels (rather than the body being a mere “object” of perception). Ratcliffe's understanding of existential feelings perfectly mirrors the notion of the intrinsically unified self-world structure, as he writes that “a feeling is a relation between body and world, rather than a perception of one in isolation” and that “bodily and worldly aspects of feeling do not respect a clear subject-object distinction.” ([16], p. 106).

Drawing on Heidegger's [7] “moods,” Ratcliffe's [16] existential feelings are not about specific phenomena in the world: neither moods nor existential feelings are intentional states; instead, moods or existential feelings are phenomenologically conceived most fundamentally, based on the fact that they constitute our being-in-the-world. Healthy moods and existential feelings are a necessary prerequisite concerning the intentional structure of self-consciousness. According to Ratcliffe [16], one cannot lose existential feelings, but what can happen is an “existential change.” We propose that such an elementary shift of the relatedness or belonging to the world is present in nihilism, which accordingly entails a complete shift of all “higher” or “foreground” emotions regarding the self and object-directed intentional states toward the world. Based on the collapse of the self-world structure's ontological core layer, existential feelings of no longer belonging to the world (to the “Being of beings” by using Heidegger's [7] terminology) arise. Such densely diminished sense of reality transforms one's existence into a void. “Feelings of nothingness” concerning both the self and the world will emerge.

We further define “feelings of nothingness” as the immediate, pre-reflective, and prelinguistic experience of nihilism. The existential situation of nihilism is immediate and pre-reflective because the schizophrenic individual cannot reflect upon it due to the temporo-spatial minimization of the intentional arc (see section Ontological Nihilism: Temporo-Spatial Reduction of the Intentional Arc), which is mirrored in the formerly elaborated phenomenological as well as epistemological constraints. It is prelinguistic not only because the connection to the social life-world and common sense is disrupted, but likewise based on the basis that existential feelings themselves cannot be articulated or expressed in a way comprehensible for a healthy person that fully lacks the intrinsically subjective nature and experience of existential nihilism. Therefore, existential nihilism can neither be substantially articulated to the therapist nor substantially conceptualized into objective features.

When we conceive existential nihilism in the perspective of existential feelings, especially in Ratcliffe's [16] understanding of the latter, then experiences and feelings of nihilism in schizophrenia cease to be connected to intentional states of consciousness, since the existential status of nihilism is itself grounded and present within a more fundamental pre-intentional realm of experience (see section Ontological Nihilism: The Remains of Experience–the Notion of “Blind-Consciousness”). Due to its pre-intentional character, feelings of nihilism can undermine the level of intentionality. These experiences and feelings that fall into the schizophrenic individual's realm, and which are noncompatible with well-established conceptual frameworks of phenomenology and psychiatry, were accordingly addressed by Laing as being a journey into the inner world and that “we are so out of touch with this realm that many people can now argue seriously that it does not exist.” ([6], p. 105).

Ontological Nihilism: Temporo-Spatial Reduction of the Intentional Arc

Traditionally, phenomenology cannot reach out beyond the intentional structure of consciousness due to the fact that phenomenologically conceived intentionality is the necessary predisposition for being conscious about something [1, 21, 29, 40, 41, 47, 51, 52]. However, as we declared in the Introduction, we suppose that nihilism in the neuropsychiatric condition of schizophrenia exhibits a deep impairment of the intentional arc of consciousness. By first taking Merleau-Ponty's [49] concepts of the “intentional arc” and second his notion of the “horizontal structure of experience” into account, we will further elaborate on the temporo-spatial minimization of intentionality.

The intentional arc connects conscious acts of the self with respective objects of the world toward which one guides intentionality. Moran ([48], p. 595) concisely defines the intentional arc as follows: “This ‘intentional arc' is an overarching framework that connects the self to the world and unifies its life, holding everything together in a coherent, meaningful way.” We propose that within the state of existential nihilism, the intentional arc can no longer fully span across both the self and the world, that is, the intention or goal of conscious acts can no longer reach out to its respective intentional objects. Such fundamental impairment of the intentional arc is equivalent to a comprehensive reduction of the subjective temporo-spatial range of consciousness, that is, the decline in subjective time and space. Vivid and meaningful experience, ranging from the most basic practical purposes up to the highest theoretical abstractions, enters the realm of an existential void if nothing can genuinely be perceived and known in principle beyond comprehensive doubt anymore. Under these circumstances, meaningful perception of phenomena as well as goal-directed behavior, for example, regarding practical purposes, are no longer possible. Providing an example regarding the loss of meaning, the schizophrenic individual may “experience” the therapist and their dialogue, but the significance or the “grasp” of the situation in conjunction with intentional behavior toward their interaction may be inaccessible. Experience loses its goals, values, and ultimately the connection to the world. Profound impairments of intentionality and practical possibilities, therefore, mirror the severance of one's being-in-the-world, our “Dasein” within (shown in Fig. 6), since “the experience of being there is not a matter of being plonked into a spatial location but of being practically situated in an interconnected web of purposes, an appreciation of which is inseparable from practical activity.” ([16], p. 46).

Fig. 6.

The intentional arc can no longer fully span across both the self and the world. This entails the breakdown of the intentional structure of consciousness, so that the unification of the self and the world dissolves. Conceived from another perspective, the intentional arc cannot “hold” or “carry” self-consciousness across a significant extent of space and time anymore; ultimately, the individual “falls” out of Heidegger's [7] notion of being-in-the-world into the existential void of nihilism, where one's “Dasein” (being-there/here) is no longer provided.

The horizontal structure of experience refers to possibilities that already inherently exist within immediate and pre-reflective experience. Such possibilities range from the most practical ones, for example, that a chair's practical usability is the possibility to sit on it, to the rather abstract opportunities, for example, the possibilities that life offers regarding one's career choices or personal beliefs. While an expanded horizontal structure concerning the functionality of objects and the significance of experience is offered and taken for granted in healthy subjects, conversely, the schizophrenic individual's horizon in the condition of nihilism is diminished. Paradigmatically, the affected individual is physically in the same room as the therapist, but the schizophrenic individual is not within the common sense, social, or life-world of practical possibilities. He or she does not share any healthy horizontal structure of experience. We tentatively go so far as to suggest that practical possibilities of ordinary life do not merely diminish but that most meaning is epistemologically excluded and hence annihilated. Such exclusion from the world additionally decreases the sense of reality and one's felt belonging to the world.

In the perspective of the intentional arc and the horizontal structure of experience, nihilism can consequently be defined in form of a reduction of graspable as well as self-affecting meaning, a radical diminishing of the lived and intersubjective accessible reality − the “sense of reality.” Such sense of reality comprises the experience of one's vital and meaningful presence within Being in general and belonging to the social life-world in particular. Conversely, the sense of reality concerning one's self and worldly experiences is taken for granted by healthy subjects, since it is guaranteed by a comprehensive temporo-spatial frame, so that intentionality intrinsically connects and merges the person and the world. In nihilism, conversely, this temporo-spatial connection between the self and the world is profoundly diminished (shown in Fig. 1b).

Ontological Nihilism: The Annihilation of Self-Consciousness

The beginning of stage 3 introduced the severance of the self-world structure, resulting in nihilism. In the section Ontological Nihilism: Existential Feelings, we subsequently described how existential feelings of nothingness that are immediate and pre-reflective can additionally account for an existential change into nihilism. Furthermore, the section Ontological Nihilism: Temporo-Spatial Reduction of the Intentional Arc elaborated on the impairment of the intentional arc. The combination of these pieces might ultimately allow for the deduction that what is phenomenologically conceived to be self-consciousness does no longer exist in existential nihilistic states in schizophrenia. The fundamental impairment of self-consciousness can even be supported by phenomenological psychopathology, precisely by relying on the fact that the possibility of self-consciousness is based on the intact self-world structure [21, 29]. The existence of the self-world structure is a necessary predisposition of self-consciousness, forasmuch as the living being contains no separate existence prior to or beyond the world to which it would then connect in a second step. Instead, the living being including healthy self-consciousness is this very relational constituted structure to and with the world [24, 32, 33, 36, 54, 58]. Healthy self-consciousness requires the immersion of being-in-the-world [54]. Accordingly, Kimura states that “[..] the ‘Subject’ can be effective only as long as the organism continues to live, it certainly belongs to this organism, but it by no means resides inside of it. Its place of being is between the organism and the environment, therefore in a certain sense outside the organism” ([37], p. 334). Consistently to the notion of self-consciousness as a relational phenomenon between the organism and the world, Jaspers [103] already declared that the human psyche, that is, self-consciousness, is not an “object” (i.e., an entity), but the integration of both the inner and the outer world. Kean [2] elucidates the severance of the self's relation to the world in the following quotation:

In my delusion, I cannot die because my true self has already died; in the universal reality, I cannot die because I do not reside in the objective reality. A delusion is the deception from the so-called “reality” to which we entrust our perception. In other words, reality lied to me − which made it no longer objective. I did not only lose my own self, I also lost my reality. There was nothing for me to believe except my nonexistence, over which I had no control. I knew there had been something, which turned into nothing. It was like combining matter with antimatter − you create a state of total annihilation but also a state of unity and stasis. ([2], p. 6)

Kean states that she did not only lose her self but also her reality. Based on the interwoven relation between the self and the world, one cannot lose one side without a significant impact on the other side. The felt minimization of one's relatedness to the world was accurately captured and described by Jaspers [3] as der absolute Nihilismus in Psychosen (the absolute nihilism in psychoses):

The patient can have no feeling, as he says, and in doing so he has the most immoderate affects of despair. He is not the former person. He is only a point. Within feelings and delusions, this experience is specified to the richest: the body is rotten, hollow, the food tumbles through an empty space when it is swallowed. The sun has gone out etc. In this state there is only the intensity of the affect, the despair as such. ([3], p. 265)

Interestingly, Jaspers [3] distinguished a state of reflective nihilism from a more extreme pre-reflective form of nihilism. Reflective nihilism is present in highly skeptical individuals within the prodromal phase of schizophrenia; here, the schizophrenic individual may be able to somewhat reflect upon his existential state. The pre-reflective form of nihilism, however, only arises in full-blown schizophrenia. In this latter state, we conceive existential nihilism, that today falls under the label of “psychosis” in institutionalized psychiatry.

The pre-reflective form of nihilism is immediately and “lived through” instead of reflectively contemplated. Wherever the skeptical schizophrenic individual within the prodromal phase possibly holds a solipsistic experience or worldview, as frequent psychopathological findings report [1, 22, 24, 84, 101, 103], he still experiences a partial grounding or “hold” of his Dasein so that being-in-the-world is not lost. Jaspers [3] metaphorically describes that such an individual within the prodromal phase has a skeptical and individualistic (reflective) mind; nonetheless, his mind is not yet throughout and necessarily “skeptical” as it is in the case in the state of pre-reflective “absolute nihilism” within psychosis. It is necessary to identify that pre-reflective and absolute nihilism is not identical to metaphysical, linguistically medicated speculation and reflection concerning Being. Instead, existential nihilism is the severance of the self's unification with the world. Metaphorically, existential nihilism in schizophrenia is a flood wave that affects experience and feelings on their pre-reflective and prelinguistic scale in the sense that it washes being-in-the-world away. Concerning such psychotic experiences, Jaspers conformably stated that “at the beginning of schizophrenic psychoses, skepticism is sometimes not only thought calmly but experienced desperately.” ([4], p. 247). Existential nihilism consequently reaches far beyond the famous concept of Jaspers' Grenzsituation (border situation), since the collapse of the self-world structure and the impairment of self-consciousness prevent the individual from choosing a coherent and meaningful point of view, as offered by healthy FPP, SPP, or TPP.

Ontological Nihilism: Scharfetter's Ideas on Nihilism in Schizophrenia

More recently, the idea of the self's possible annihilation was similarly shared by Swiss psychiatrist Christian Scharfetter (1936–2012) [46, 104, 105, 106]. Building on experiential modes of self-awareness by Jaspers [103], which Scharfetter called “ego-consciousness,” he developed 5 basic dimensions of self-consciousness based on the individual's experiences. Scharfetter [46, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108] conceptualized these 5 dimensions as vitality, activity, consistency/coherence, demarcation, and identity. It is the dimension of “vitality” that is the relevant for nihilism in schizophrenia. Vitality is the sense of being alive, which is abnormally heightened in mania eventually leading to megalomania, while on the contrary, it is reduced or even lost in schizophrenia [46, 104]. Vitality reflects a quantitative continuum, where on its extreme ends, specific neuropsychiatric disorders are located. The core disturbance of schizophrenia is accordingly considered to be the ego/self-fragmentation and dissolution by Scharfetter [46, 105, 106]. In its extreme manifestations, the ego/self-fragmentation amounts to a loss of vitality, resulting in the final annihilation of the ego/self and the loss of the phenomenal world [46]. The annihilation of one's perceived existence seems to be a paradoxical configuration we did not yet touch upon. Strangely, the schizophrenic individual's experience and report of this very doom still exist. According to Scharfetter [46], the FPP is only left in the form of an “a-personal” and overwhelming suffering: “for the person with schizophrenia, the ‘cogito ergo sum’ of Descartes is not convincing and the fact that he is in dialogue with this therapist is not an argument against his non-being.” ([109], p. 71).

We can take this ambiguity and the paradox into perspective under the light of Heidegger's conceptualization of “Being” versus “beings.” Following Heidegger's [7] concepts and terminology, the schizophrenic individual's ontology (Sein [Being]), which is most fundamental the “Being of beings,” can be separated from his intended ontic meaning or status regarding the empirical reality and natural world (Seiende [beings]). As for addressing the latter, that is, our shared and social life-world, the schizophrenic individual may lack equivalent conceptualizations and linguistic powers, by which he could articulate the elementary existential change into ontological nihilism (instead of “ontic nihilism”). Concerning the fact that, paradigmatically, such an individual continues to follow a daily routine after having just declared that he is dead and that the world does not exist, Sass [1] elucidates that “[…] like a philosopher of solipsism who continues to move his pencil as if it were an objective thing and to address his colleagues as if ‘other minds’ really did exist, such a patient may well carry on a semblance of normal life in spite of his own belief in the supposed nonexistence of reality.” ([1], p. 245).

The schizophrenic individual's overwhelming suffering in nihilism, as described by Scharfetter [46], as well as the change in his most fundamental existential feeling, can consequently not refer to the sole ontic empirical reality. Instead, such forms of pathology may arise from the constitutional and disrupted ontological layer of existence. In another perspective, this reflects a shift of the individual's existential orientation, precisely his existential feelings when using Ratcliffe's [16] conceptualizations. Existential feelings serve as the background of one's lived existence, and existential feelings of nihilism destroy any vivid and vital form of self-consciousness. Even though vivid and vital experience is absent in “feelings of nothingness,” it is precisely this nihilistic experience that is perceived. Ratcliffe specifies this phenomenon: “Experience of absence is not the absence of something from experience − the ‘nothing’ as Heidegger recognizes, is ‘there’.” ([16], p. 72). Consequently, not the absence of any experience is present, but an overarching existential “feeling of nothingness” remains. The drastically diminished sense of reality, the severance of one's belonging to the world, is felt as such. Ratcliffe [16] declares that philosophical language might be too restricted to provide satisfactory explanations of such felt nothingness. However, explanations, whereas they often appear as vague and metaphorical, can be found in the everyday language of people who are affected by such existential feelings. When considering the above, it might be more comprehensible how intensive experiences and feelings of authentic “nothingness” can converge into the expressions of being dead or that the world is doomed. The understanding of the schizophrenic individual's existential situation in nihilism and his expressions as not being literal statements of his ontic empirical reality, but instead of his existential background of experience, is likewise shared by Ratcliffe: “What the patient is expressing is a radically altered existential orientation, rather than a propositional content” ([16], p. 167) and that “what is lost is the sense of existence that ordinarily operates as a background to all experience.” ([16], p. 169).

Ontological Nihilism: The Remains of Experience − The Notion of “Blind-Consciousness”

What remains in the experience and state of nihilism? When converging the above, the experience transforms into a pre-intentional mode that we term “blind-consciousness” due to the lack of intentionality. Subjectivity can no longer provide its transcendental function regarding the sense of reality in general plus any sense of self and the relatedness toward the world in particular. We can only conceive such a pre-intentional state as metaphysical horror − where both the self and the world are no longer accessible in any healthy fashion. Within this state of existence bereft of any possibilities, the schizophrenic individual does not reflectively infer that he is dead and that the world no longer exists; instead, “feelings of nothingness,” or the impairment of the horizontal structure of consciousness regarding one's practical possibilities within the world, is inherently interwoven into this pre-intentional state. One cannot reflect upon it but only immediately go through it.