Series describing the evolution of patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) secondary to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) during the first wave of the pandemic have reported mortalities ranging from 30% to 60% [1, 2]. More recent publications have demonstrated a trend towards a higher mortality in COVID-19 patients receiving support in later periods of the pandemic, even though the overall mortality of the disease seems lower [3, 4]. The reasons for this difference are not clear.

Short abstract

When indicating ECMO in patients with COVID-19, centre case volume, age, driving pressure and the duration of symptoms (not the length of MV) should be taken into account. Large drainage cannula and high PEEP levels during the first days are recommended. https://bit.ly/3DGjGkk

To the Editor:

Series describing the evolution of patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) secondary to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) during the first wave of the pandemic have reported mortalities ranging from 30% to 60% [1, 2]. More recent publications have demonstrated a trend towards a higher mortality in COVID-19 patients receiving support in later periods of the pandemic, even though the overall mortality of the disease seems lower [3, 4]. The reasons for this difference are not clear.

The ECMOVIBER study (The use of ECMO during the coVid-19 pandemic in the IBERian peninsula) is a retrospective-prospective observational cohort study which included consecutive adult patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with severe ARDS and rescued with extracorporeal respiratory support from 1 March to 1 December 2020 across 24 ECMO centres (22 in Spain and two in Portugal). In general, inclusion and exclusion criteria for ECMO were those applied in the EOLIA trial [5]. Patients were followed for 6 months after ECMO commencement. The aim of the study was to identify factors associated with hospital mortality. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees at all the participating centres. The need for informed consent was waived in view of the retrospective nature of the analysis, and because only data available in the medical records were collected. Qualitative variables were described as numbers and percentages. Quantitative variables were described as means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Confidence intervals for all analyses were set at 95%. The Kaplan–Meier method was used for survival analysis. Variables entered in the Cox proportional hazard model were defined on the basis of their univariate p-value and their clinical relevance evaluated according to the literature on ECMO and COVID-19. Clinically relevant variables were included in a multivariate Cox model. Statistical analysis was performed with the “R” statistical software (R version 4.0.3 (2020-10-10), The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

A total of 338 patients at the 24 centres received ECMO support during the study period. In 319 (94.4%) cases ECMO was started as a supportive measure for ARDS. Overall mean age was 53±10 years, 258 patients (80.9%) were male, and hypertension was the most common comorbidity (121; 37.9%). Patients were cannulated after a median of 5 (3–9) days from the initiation of mechanical ventilation (MV), 7 (4–13) days after ICU admission and 17 (12–22) days after symptom presentation. Coinfection at ECMO initiation was recorded in 95 (29.8%) cases. 96 (30.1%) patients were supported at high-volume centres (>30 ECMO cases per year) and 129 (40.4%) needed ECMO retrieval and transport.

180 (56.4%) patients were successfully decannulated. The median duration of ECMO support was 17 (9–32) days, with 84 (26.3%) runs lasting more than 30 days. 156 patients (48.9%) were discharged alive, 156 (48.9%) died in the hospital and seven patients were still hospitalised at 6-month follow-up (one of whom remained on ECMO).

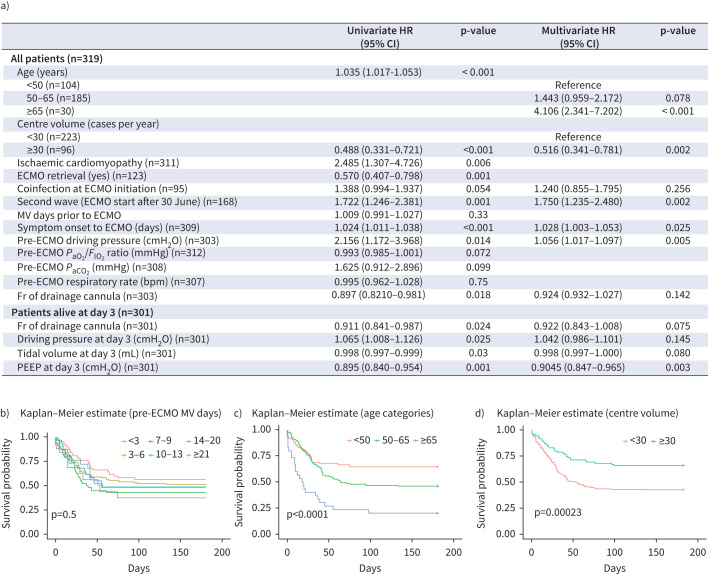

Associations of variables with hospital mortality are detailed in figure 1a. Age, ischaemic cardiomyopathy, centre case volume, ECMO retrieval, days from symptoms to cannulation, driving pressure prior to ECMO and drainage cannula size were associated with hospital mortality. In contrast, pre-ECMO MV days were not associated with survival (figure 1b). In the multivariate analysis including the wave in which ECMO support was received, the hazard ratio for hospital mortality was four times higher in patients over 65 years, and the survival rate of patients supported at centres with a volume of 30 cases or above was significantly higher (figure 1c and d). Longer time from symptom onset and higher driving pressure before cannulation were associated with a higher risk of hospital mortality, while higher levels of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) at day 3 of ECMO support were associated with a lower risk of hospital mortality. Larger drainage cannula diameter was also associated with a reduced risk of death on ECMO (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.80–0.96; p=0.005) but not when it was included in the multivariate model for hospital mortality.

FIGURE 1.

a) Cox model including relevant factors and its association with hospital mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients with extracorporeal respiratory support. Kaplan–Meier survival estimates according to b) pre-ECMO mechanical ventilation days, c) age categories and d) centre case volume. HR: hazard ratio; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; MV: mechanical ventilation; PaO2: arterial oxygen tension; PaCO2: arterial carbon dioxide tension; FIO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; bpm: breaths per min; Fr: french; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure.

In this large multicentre series of COVID-19 patients receiving ECMO support, we detected several factors associated with hospital mortality. The study of these factors might help in the identification of COVID-19 cases who might benefit the most from ECMO and provide valuable information for improving the management of these patients.

Regarding the criteria for indicating the technique, a period of MV longer than 7–10 days prior to ECMO commencement has traditionally been considered as a contraindication. Recently, Díaz et al. [6] indicated that length of MV had no impact on survival; however, the study included only 11 patients with prolonged duration of MV prior to ECMO. Our analysis, which includes 72 patients with more than 10 days of pre-ECMO MV, confirmed the absence of this association; in fact, we found an association between longer time between symptom onset and ECMO initiation with a higher risk for hospital mortality. This time frame includes the period of non-invasive oxygen therapy prior to intubation, in which the lung could be further damaged leading to a potential decrease in lung resilience. Over the course of the pandemic the time of invasive MV initiation changed, with a general tendency for an early start during the first wave and delayed intubation in later periods. In these later phases there was also a dispersion of ECMO cases [4]. In this regard, and in agreement with previous results [7], we found that patients supported at centres with a high case volume had a lower mortality. The recommendation to concentrate cases at high-volume centres should include the capability to retrieve the sickest patients admitted to hospitals that do not have access to this technique [8, 9]. Not surprisingly, in our series, patients who were retrieved had lower hospital mortality, a finding that reinforces the idea that attention should be centralised. The age cut-off point for ruling out ECMO support has also been a matter of debate [10]. In our series, in agreement with previous reports [11], survival rates were significantly lower in patients aged over 65 years, and so it seems reasonable to establish age over 65 years as a relative contraindication for COVID-19 ECMO support.

Adequate management of the extracorporeal support, together with the pathological condition itself, also have a direct impact on outcome. Lung parenchyma of COVID-19 patients needing ECMO is severely affected, with notably high lung elastance and very low residual function [12, 13]. High ECMO flows are needed in this situation in order to ensure adequate oxygen delivery and allow ultraprotective MV. For this reason, the diameter of the drainage cannula has to be large enough to achieve these high ECMO flows. Our analysis found information suggesting that a larger diameter of the drainage cannula was a protective factor. However, this association should be confirmed in further investigations. MV management of patients on ECMO has also been considered [14]. Our multivariate analysis indicated a relationship between higher PEEP levels on the third day of ECMO support and a lower risk of hospital mortality. This result is in agreement with those of previous reports, including patients with ARDS [15], but no information has been published to date about PEEP titration in COVID-19 ECMO patients.

In conclusion, when indicating ECMO support for ARDS in COVID-19 patients, centre case volume, age, driving pressure and the duration of symptoms should be taken into account. Length of MV prior to ECMO per se should not be included in this decision. In the management of these patients, PEEP levels should be kept high during the first days.

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgements

Statistical analysis was carried out in the Statistics and Bioinformatics Unit (UEB) Vall d'Hebron Hospital Research Institute (VHIR).

Footnotes

The following practitioners provided care for the study patients. Hospital Universitario Vall d'Hebron: Ricard Ferrer, Francesc Xavier Nuvials, Juan Carlos Ruiz-Rodríguez, Oriol Roca, Marina García, Manel Santafé, Cándido Díaz, Sandra García, Rosa María Gracia, Anna Sánchez, Raquel Albertos, Marcos Pérez, Adolf Ruiz, Elisabeth Papiol, César Laborda, Judith Sacanell, Mónica Diez, Carolina Maldonado, Luis Chiscano, Manuel Sosa, Claudia Vizcaíno, Alexandra Cortina, Alejandro Cortés, Noemí Varga, Sofía Contreras, Xavier Peris, Álvaro García, Berta Caralt, Abraham Mera, Andrés Pacheco, Clara Palmada, Arsenio De la Vega, Francisco José Ramos, Pilar Girón, Elisabet Gallart, Carme Durà, Antonio López, Laura Planas, Nuria Pey, Beatriz Lozano, Samuel Carmona, Montse Aran, Montse Rodríguez (Dept of Intensive Care); Rafael Rodríguez-Lecoq, Carles Sureda, Miguel Ángel Castro, Remedios Ríos, María Sol Siliato, Neisser Palmer, Paula Resta (Dept of Cardiac Surgery). São João Universitary Hospital Center: Anne Moura (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitari Bellvitge: María Dolores Belda, Pau Serra, Alejandro García, Gloria Muñoz, Eva Santafosta, Marta Huguet, Paola Sastre, Ricard Soley, María Pons, Neus López, David Berbel, Victor Daniel Gumucio, Xose Luis Pérez, Joan Sabater (Dept of Intensive Care); Javier Tejero, Arnau Blasco, Karina Osorio, Marcos Potocnik, Fabrizio Sbraga (Dept of Cardiac Surgery). Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central: Maria João Lopes (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca: Domingo Martínez (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitario Rio Hortega: Rubén Herrán, Ana Prieto, David Pérez, Cristina Díaz (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitario La Paz: Jorge Rodríguez, Carola Gutiérrez, Claudia Díaz, Kapil Nanwani, Andoni García, Manuel Sánchez, José Manuel Añón, María José Asensio, Juan Carlos Figueira, Manuel Quintana, Belén Estébanez, Abelardo García de Lorenzo, Alexander Agrifoglio, Lucia Cachafeiro (Dept of Intensive Care); Emilio Maseda, Javier Sagra, Itziar Insausti, Alejandro Suárez de la Rica, Ana Montero (Dept of Anesthesiology). Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol: Esther Mor, Marc Fabra, Màrius Sánchez, Mireia Anglada, Patricia Boronat, Ana Cabaña, Fernando Chávez (Dept of Intensive Care); Christian Muñoz (Dept of Cardiac Surgery). Hospital Universitario Cruces: Mónica Domezain, Katherine García, Jose Luis Moreno Gómez (Dept of Intensive Care); Jose Ignacio Aramendi, Andrés Mauricio Cortes, Miguel Angel Rodriguez, Daniel Arturo Rivas (Dept of Cardiac Surgery). Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro: Marina Pérez-Redondo, Alfonso Ortega, Daniela Ballesteros, Nuria Martínez-Sanz, Inmaculada Fernández-Simón (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal: Raúl de Pablo, Juan Higuera (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón: Alexis Jaspe, Jamil Cedeño, Sara Casanova, Miguel Ángel Gómez, María Dolores Gil (Dept of Intensive Care); Iago Sousa (Dept of Cardiology). Hospital Universitari Clínic: Anna Muro, Daniel Pereda, Eduard Quintana, Jorge Alcocer, Manuel Castellá (Dept of Cardiovascular Surgery); Adrián Téllez, Sara Fernández (Dept of Intensive Care); Javier Fernández, Néstor David Toapanta (Liver Unit); Teresa López, Rut Andrea (Cardiology Dept); Cristina Ibáñez, Juan M Perdomo, Ricard Navarro-Ripoll, M José Arguis, M José Carretero, Manuel López-Baamonde, Elena del Río, Carlos Ferrando (Dept of Anesthesiology and Critical Care); Juan Ramon Badia (Respiratory Institute, August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute). Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet: José Ángel de Ayala, Luis Manuel Claraco (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias: Laura Amado, Raquel Rodríguez (CIBERES, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid). Hospital Clínico San Carlos: Montse Rodríguez, Sara Domingo, Antonio Núñez, Fernando Martínez (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe: Francisca Pérez, Isabel Madrid, Luís de Hevia, Mónica Gordón, Mónica Talavera (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitari Son Espases: Marta Ocón, María Riera (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro: Ignacio Chico (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Macarena: Fransciso González González, Elena Gordillo Escobar, José Garnacho Montero (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Clínico Universitario Valladolid: Nicolás Hidalgo (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó: Xema Núñez (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Universitario Reína Sofía, Córdoba: Javier Muñoz (Dept of Intensive Care). Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela: María Eiras (Dept of Anesthesiology).

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Henry BM, Lippi G. Poor survival with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): pooled analysis of early reports. J Crit Care 2020; 58: 27–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbaro RP, MacLaren G, Boonstra PS, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in COVID-19: an international cohort study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Lancet 2020; 396: 1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32008-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broman LM, Eksborg S, Coco VL, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for COVID-19 during first and second waves. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: e80–e81. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00262-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riera J, Roncon-Albuquerque R, Fuset MP, et al. Increased mortality in patients with COVID-19 receiving extracorporeal respiratory support during the second wave of the pandemic. Intensive Care Med 2021; 47: 1490–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1965–1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Díaz RA, Graf J, Zambrano JM, et al. ECMO for COVID-19-associated severe ARDS in Chile: a nationwide incidence and cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 204: 34–43. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202011-4166OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebreton G, Schmidt M, Ponnaiah M, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation network organisation and clinical outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greater Paris, France: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 851–862. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00096-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riera J, Argudo E, Martínez M, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation retrieval in coronavirus disease 2019: a case-series of 19 patients supported at a high-volume extracorporeal membrane oxygenation center. Crit Care Expl 2020; 2: e0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramanathan K, Antognini D, Combes A, et al. Planning and provision of ECMO services for severe ARDS during the COVID-19 pandemic and other outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 518–526. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30121-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karagiannidis C, Brodie D, Strassmann S, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: evolving epidemiology and mortality. Intensive Care Med 2016; 42: 889–896. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4273-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt M, Zogheib E, Rozé H, et al. The PRESERVE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 1704–1713. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3037-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marini J, Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress. JAMA 2020; 323: 2329–2330. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merdji H, Mayeur S, Schenck M, et al. Histopathological features in fatal COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Med Intensiva 2021; 45: 261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2021.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neto A, Schmidt M, Azevedo L, et al. Associations between ventilator settings during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory hypoxemia and outcome in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a pooled individual patient data analysis: mechanical ventilation during ECMO. Intensive Care Med 2016; 42: 1672–1684. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4507-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt M, Stewart C, Bailey M, et al. Mechanical ventilation management during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective international multicenter study. Crit Care Med 2015; 43: 654–664. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-02463-2021.Shareable (433.5KB, pdf)