Abstract

An investigational live influenza virus vaccine, FluMist, contains three cold-adapted H1N1, H3N2, and B influenza viruses. The vaccine viruses are 6/2 reassortants, in which the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) genes are derived from the circulating wild-type viruses and the remaining six genes are derived from the cold-adapted master donor strains. The six genes from the cold-adapted master donor strains ensure the attenuation, and the HA and NA genes from the wild-type viruses confer the ability to induce protective immunity against contemporary influenza strains. The genotypic stability of this vaccine was studied by employing clinical samples collected during an efficacy trial. Viruses present in the nasal and throat swab specimens and in supernatants after culturing the specimens were detected and subtyped by multiplex reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR. Complete genotypes of these detected viruses were determined by a combination of RT-PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism, multiplex RT-PCR and fluorescent single-strand conformation polymorphism, and nucleic acid sequencing analysis. The FluMist vaccine appeared to be genotypically stable after replication in the human host. All viruses detected during the 2-week postvaccination period were shed vaccine viruses and had maintained the 6/2 genotype.

Influenza viruses have been shown to be quite mutable and adaptable (17, 18). High mutation rates that result in sequence changes in the two major surface antigens, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), are responsible for the frequent influenza epidemics in the human population (11). An investigational live influenza virus vaccine (FluMist) which contains three live, cold-adapted H1N1, H3N2, and B influenza viruses is being developed for influenza prevention (1). These vaccine viruses are 6/2 reassortants, in which the HA and NA genes are derived from the circulating wild-type viruses and the remaining six genes (PB2, PB1, PA, NP, M, and NS) are derived from the cold-adapted master donor strains, A/Ann Arbor/6/60 (CA-A) and B/Ann Arbor/1/66 (CA-B). The cold-adapted master donor strains were derived by H. F. Maassab at the University of Michigan by passaging wild-type viruses in primary chick kidney cells through progressively lower temperatures, resulting in viruses that replicated efficiently at 25°C (9, 10). The cold-adapted master donor strains exhibit several attenuation characteristics in cell culture and in a ferret animal model (9, 10). A global surveillance system governed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization was established to monitor the drift of the antigenic structures of emerging influenza viruses. The accrued information provides public health authorities with the basis of selecting the HA and NA genes from the appropriate wild-type viruses for incorporation into the influenza virus vaccine (3, 4). Therefore, the six genes from the cold-adapted master donor strains ensure the attenuation and the HA and NA genes from the wild-type viruses confer the protective immunity against contemporary influenza strains. Since genetic stability supports and maintains the attenuation and immunogenicity, it is important to monitor the conservation of the 6/2 genotype of FluMist after vaccination.

During the 1996 to 1997 influenza season, the efficacy of FluMist was studied in a multicenter, double-blind, and placebo-controlled clinical trial enrolling 1,602 children from 15 to 71 months of age. A 93% overall vaccine efficacy against culture-confirmed influenza was observed (1). Some nasal and throat swab specimens were collected during the 2-week postvaccination period. This report describes the detection, genotyping, and sequence analysis of the culture-positive samples from these specimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical samples.

As listed in Table 1, samples from 17 study participants were analyzed in this report. These samples represent all available nasal and throat swab specimens collected within a 2-week period after vaccination, for which the local clinical laboratory reported the isolation of influenza virus. The samples were obtained primarily from 1 of the 10 investigative sites based on clinical symptoms. No wild-type influenza viruses were circulating in the community at this time. The swab specimens were inoculated into rhesus monkey kidney (RhMK) cells at the clinical trial site for viral isolation. Both the culture supernatants and the remaining swab specimens were sent to Aviron for further laboratory analysis. For participant 6336, two samples corresponding to two different collection dates were provided.

TABLE 1.

A summary of virus identification, phenotyping, and genotyping results

| Participant | Days from vaccination | Virus identification

|

Phenotypea | Genotypeb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical site | ACTL | Multiplex RT-PCR

|

|||||

| Culture | Swab | ||||||

| 6372 | 5 | B | B | B | B | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6343 | 8 | B | B | B | B | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6148 | 5 | A | H3 | H3N2 | H3N2 | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 5958 | 7 | B | B | B | B | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6350 | 7 | A, B | H3, B | H3N2, B | H3N2, B | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA]c |

| 6142 | 2 | A | H3 | H3N2 | H3N2 | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6126 | 3 | B | B | B | B | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6358 | 7 | B | B | B | B | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6336A | 3 | A | H3 | H3N2 | NDe | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6336B | 9 | B | B | B | B | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6584 | 6 | B | B | B | B | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6604 | 3 | A, B | H3, B | H3N2, B | H3N2, B | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA]c |

| 6116 | 3 | A | H3 | H3N2, B | H3N2, B | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA]c |

| 6131 | 6 | A | H3 | H3N2 | ND | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6149 | 5 | B | B | B | ND | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 5490 | 11 | B | B | B | ND | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6329 | 6 | B | B | B | ND | ca, ts | 6/2[HA,NA] |

| 6599d | 7 | B | B | ND | ND | ca, ts | ND |

A ca phenotype is defined as the ability of virus to replicate at 25°C to titers comparable to those at 33°C. A ts phenotype is defined as at least 2-log reduction in titer at 39°C (type A) or 37°C (type B) when compared to that at 33°C.

The genotype is denoted as X/Y[genes], with X and Y indicating the number of gene segments from cold-adapted and wild-type parental viruses, respectively, followed by the name of the gene segment from the wild type.

Both A and B viruses were determined to have the genotype 6/2[HA,NA].

The presence of an influenza B virus with both ca and ts phenotypes was determined earlier by ACTL. An attempt to reculture this virus from a swab specimen for genotyping was unsuccessful.

ND, not done.

Viruses.

Each vaccine virus was a 6/2 reassortant derived from the two parental viruses, a cold-adapted master donor strain and a circulating wild-type virus. Parental viruses for the vaccine used in this clinical trial were CA-A and CA-B, the two cold-adapted master donor strains, and A/Texas/36/91 (H1N1) (A/TX), A/Wuhan/359/95 (H3N2) (A/WH), and B/Ann Arbor/1/94 (B/AA), the three wild-type viruses. Virus stocks were prepared in specific-pathogen-free eggs (SPAFAS, Inc., Preston, Conn.) as previously described (6).

Viral RNA genome isolation.

A 200-μl aliquot of each culture supernatant and viral stock was extracted to isolate the virus genomic RNA. RNA was isolated by incubating the samples with proteinase K (0.7 μg/μl) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (0.5%) at 56°C for 10 min, followed by a phenol-chloroform extraction. The extracted RNA was resuspended in 100 μl of H2O. The swab specimens were of limited volume, ranging from 10 to 220 μl; RNA was resuspended in 20 μl of H2O after extraction.

Oligonucleotide synthesis.

Oligonucleotides were synthesized with an ABI 392 oligonucleotide synthesizer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Three fluorescent dyes (6-FAM [blue], HEX [green], and NED [yellow]) were used to label oligonucleotides at the 5′ terminus. The fluorescent dye-labeled oligonucleotides were either synthesized at Aviron or purchased from PE Applied Biosystems.

Multiplex RT-PCR detection.

It is important to implement rigorous contamination control in clinical diagnostic applications using PCR. We have outfitted a PCR laboratory comprised of three segregated parts: a reagent room, a template preparation room, and an amplification and analysis room. In addition to this physical segregation, standard operation procedures are established and the PCR process is conducted in a directional and irreversible flow from the reagent room to the template preparation room and then to the amplification room. Both positive and negative controls were included along with the samples for every reaction. Six pairs of PCR primers were designed to achieve specific amplification of the HA and NA genes of the H1N1, H3N2, and B influenza viruses. The primers were designed in such a way that all six PCR products from all three viruses could be generated in a single reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR. A 10-μl aliquot of extracted RNA was used in an RT-PCR that was conducted with the same procedure as for each primer pair, following that of the Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp RNA PCR Kit with AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (PE Applied Biosystems). PCR conditions were 12 min at 95°C, 5 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The multiple products resulting from a single reaction mixture were easily distinguished because they were different lengths and they were labeled with different fluorescent dyes. Gel electrophoresis was run on an ABI 377 automated sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems). Table 2 lists the primer sequences and their positions in the virus genomes.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in multiplex RT-PCR detection, multiplex RT-PCR and F-SSCP genotyping, and sequencing

| Type | Gene | Dye | Sense primera | Positionb | Antisense primera | Positionb | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | H1 | NED | TAGCAGAAGATTCACCCCAG | 720 | Fc-TGACTGGGTGTACATTCTGG | 997 | 278 |

| H2 | 6-FAM | CGGTTGCCAAAGGATCGTAC | 558 | F-AGGGTCCAAGAGAATTCCAT | 780 | 223 | |

| H3 | 6-FAM | ATAATGAGGTCAGATGCACC | 876 | F-ATGCCTGAAACCGTACCAAC | 1142 | 267 | |

| N1 | NED | F-AGGGACAATTGGCACGGTTC | 909 | GTCCTTCCTATCCAAACACC | 1117 | 209 | |

| N2 | 6-FAM | F-TGAGTTGGGTGTTCCATTTC | 502 | ACGCATTCCGACTCCTGG | 711 | 210 | |

| NP | TGCCTGCCTGTGTGTATGG | 872 | TGGTCCTTATGGCCCAGTA | 1216 | 345 | ||

| B | HA | HEX | GAAGATGAGCATCTCTTGGC | 1450 | F-GCAAGAAACATTGTCTCTGGAGACC | 1776 | 327 |

| NA | HEX | F-GCTACCTTCAACTATACAAACG | 19 | AACGAGGGTATGTCCACTCC | 269 | 251 | |

| M | 6-FAM | F-ATGTCGCTGTTTGGAGACAC | 25 | GCTAGAATCAGGCCTTTCTT | 320 | 296 |

Sense is defined as the sequence complementary to the RNA genome sequence.

Position number represents the primer's 5′ end nucleotide position in the genomes of cold-adapted master donor strains (5, 7), except for H1, H3, and N1. The sequence of A/Shenzhen/227/95 (T.-A. Cha and J. Zhao, unpublished data) was used to denote the positions of H1 and N1 primers. The published sequence of A/Memphis/1/71 (accession no. J02132) was used to denote the positions of H3 primers.

F, a fluorescent dye-labeled primer.

RT-PCR and RFLP genotyping.

As described previously (13), a 10-μl aliquot of extracted RNA was used in an RT-PCR to generate product from each individual gene for subsequent restriction digestion, followed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. The RT-PCR was conducted by following the Qiagen Taq PCR handbook (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, Calif.). PCR conditions were 1 min at 94°C, 2 min at 55°C, and 3 min at 72°C, which was repeated for 30 cycles. A 1% agarose gel electrophoresis was used to analyze the digested and nondigested products. The HA gene of influenza A was typed by the generation of RT-PCR products with subtype-specific primers. Table 3 lists the primers used in the RFLP analysis.

TABLE 3.

Primers used in RT-PCR and RFLP genotyping

| Type | Gene | Sense primera | Positionb | Antisense primera | Positionb | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | PB2 | GAAGTACACATCAGGGAGAC | 123 | GCCTAAGGATGTCTACCATCC | 925 | 803 |

| PB1 | ATGAGAAGAAAGCAAAGTTGGCAAATGTTG | 851 | GTTGCTGGACCAAGATCATTGTTTATCAT | 1652 | 802 | |

| PA | CTCAAATGTCCAAAGAAG | 764 | CCATGCTCACAAAGTTTACC | 1594 | 831 | |

| H1 | CTACTGGTCCTGTTATGTGC | 13 | TAGAACACATCCAGAAGCTG | 1669 | 1,657 | |

| H2 | CTCATTCTCCTGTTCACAGC | 59 | GCAGATCCTGCACTGCAGAG | 1726 | 1,668 | |

| H3 | GACTATCATTGCTTTGAGC | 35 | TGTTGCACCTAATGTTGCC | 1718 | 1,684 | |

| NP | GAGAATGGTGCTCTCTGC | 237 | CGATCGGGTTCGTTGCC | 1471 | 1,235 | |

| N1 | (GCGCGCGAATT)CAACACTAATGTTGTTGCTGGAAAGc | 230 | CCGAAAACCCCACTGCAGATG | 988 | 770 | |

| N2 | GGCTCTGTCTCTCTCACC | 50 | CAGGCCATGAGCCTGTTCC | 1397 | 1,348 | |

| M | CTTCTAACCGAGGTCGAAACG | 32 | TTACTCCAGCTCTATGCTGAC | 1007 | 976 | |

| NS | GACAAAGACATAATGGATCC | 15 | GCTGAAACGAGAAAGTTCTTATCTC | 856 | 842 | |

| B | PB2 | CTGTTAAGGGACAATGAAGC | 57 | TTTATTTCTCCTCTCACTCCTTG | 1285 | 1,229 |

| PB1 | CATAGATGTACCCATACAG | 48 | AAATCCCGGAACCAAATTGG | 1028 | 981 | |

| PA | AGGCCAAAAACACAATGGCAGA | 76 | GTGGCCCACTTGGCATAATT | 1126 | 1,051 | |

| HA | GTACTACTCATGGTAGTAACATCC | 49 | GCAAGAAACATTGTCTCTGGAGACC | 1776 | 1,728 | |

| NP | GAGTTGGACTTGACCCTTCAT | 708 | GGTCATCATAATCCTCTGCTGT | 1730 | 1,023 | |

| NA | GCTACCTTCAACTATACAAACG | 19 | CAATTAAGTCCAGTAAGGAC | 1493 | 1,475 | |

| M | ATGTCGCTGTTTGGAGACAC | 25 | CTGACATTGATTACAATTTGC | 1157 | 1,133 | |

| NS | GTTTAGTCACTGGCAAACGG | 19 | CACAAGCACTGCCTGCTGTAC | 1067 | 1,049 |

Sense is defined as the sequence complementary to the RNA genome sequence.

Position number represents the primer's 5′ end nucleotide position in the genomes of cold-adapted master donor strains (5, 7), except for H1, H3, and N1. Published sequences of A/NWS/33 (accession no. U08903) and A/Chile/1/83 (accession no. X15281) were used to denote the positions of H1 and N1 primers, respectively. The published sequence of A/Memphis/1/71 (accession no. J02132) was used to denote the positions of H3 primers.

Enclosed in parentheses is a noninfluenza sequence.

Multiplex RT-PCR and F-SSCP genotyping.

The fluorescent single-strand conformation polymorphism (F-SSCP) gel electrophoresis was performed as previously described (2), except for the following modifications: (i) an ABI 377 automated sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems) with an external refrigerated water circulator (Neslab Instruments, Inc., Portsmouth, N.H.) was used, (ii) the gel was run at a 20°C setting for 6 h, and (iii) the GENESCAN-500 ROX (PE Applied Biosystems) was used as an internal standard. The GENESCAN-500 ROX was a red-labeled DNA marker and was added to each sample. The marker bands in each sample could be used to normalize the lane-to-lane variation (2). Data were collected and analyzed by GENESCAN software (PE Applied Biosystems).

Nucleic acid sequencing and analysis.

A 10-μl aliquot of extracted RNA was used in a multiplex RT-PCR to generate multiple gene products for sequencing. The RT-PCR products were sequenced with an ABI PRISM dRhodamine Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit and run on either an ABI 373 stretch or ABI 377 automated sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems). Sequence analysis was performed with MacDNASIS (Hitachi Software, San Bruno, Calif.).

RESULTS

Multiplex RT-PCR detection.

The nasal and throat swab specimens were cultured to isolate viruses, and the presence of influenza A or B virus was reported by the local clinical laboratory. The culture supernatants and the remaining swab specimens were sent to Aviron. Further subtyping of influenza A viruses using HA type specific antiserum and phenotypic analysis of cold adaptation (ca) and temperature sensitivity (ts) were performed on the cultured viruses by the Aviron clinical testing laboratory (ACTL). These results are summarized in Table 1 (S. Pennathur, personal communication). For participant 6599, the original culture supernatant was consumed for the subtyping and phenotyping analysis. An attempt was made at ACTL to reculture the virus with the remaining swab specimen, but no influenza virus was recovered. The amount of viable influenza virus contained in the swab specimen was presumed to be inadequate for culturing due to the long storage and freezing-thawing procedures.

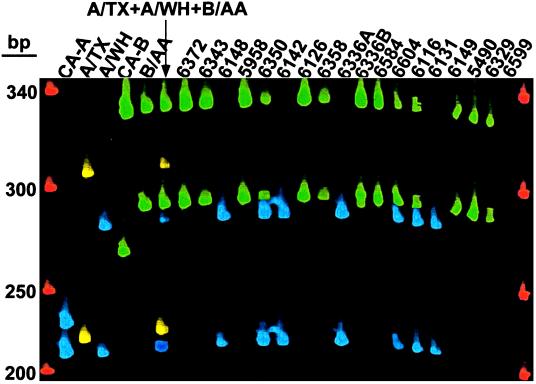

A total of 18 culture supernatants, including the negative supernatant of a repeat culture for participant 6599, and 12 available corresponding swab specimens were subjected to multiplex RT-PCR detection. Figure 1 shows the result of analyzing the culture supernatants. No virus was detected in the sample of participant 6599. In all other samples, either an H3N2 or a B influenza virus or a mixture of the two was detected. With this method, both the HA and NA subtypes of influenza A were determined. An influenza B virus, in addition to the influenza A virus reported earlier by the local clinical laboratory, was detected in the sample of participant 6116. No H1N1 was detected in any of these samples.

FIG. 1.

Gel file of fragment analysis of multiplex RT-PCR products of HA and NA genes. Blue bands denote H3 and N2, yellow bands denote H1 and N1, and green bands denote HA and NA of influenza B. H2 was labeled with blue dye. In each pair of bands with the same color, the slower moving band was HA and the faster moving band was NA. The size markers are shown in red. The product sizes are listed in Table 2.

The 12 available corresponding swab specimens yielded the same results as those in Fig. 1. Although the quantity of the virus present in the swab specimens was not determined, this result was significant because it demonstrated the sensitivity of the method for the detection and subtyping of influenza viruses directly in the original swab specimens without amplification in cell culture. The detection of an additional influenza B virus in both the swab specimen and culture supernatant samples of participant 6116 suggests the enhanced sensitivity of detecting the nucleic acid genome directly versus detecting viral antigens after culture. The failure to detect H1N1 in both culture supernatants and swab specimens by either culture or direct genome detection indicated that H3N2 and B viruses were more likely to be shed in this group of participants during the interval of 2 to 11 days after vaccination (Table 1).

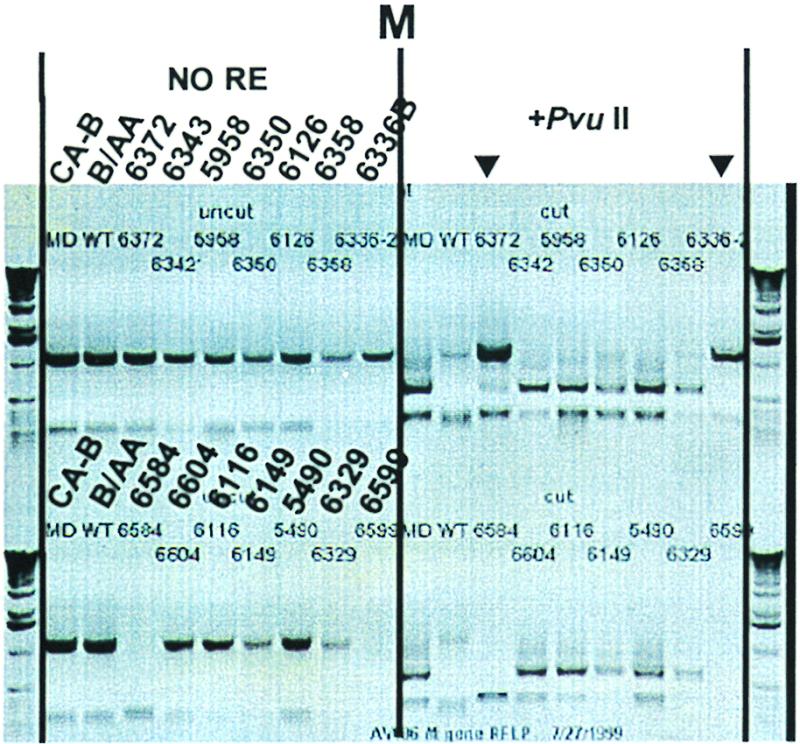

RT-PCR and RFLP genotyping.

As shown in Fig. 1, there were seven H3N2 and 13 B isolates, and one sample (participant 6599) contained no detectable virus. RT-PCR and RFLP genotyping was performed separately on the influenza A and influenza B viruses. The participant 6599 sample was included in the influenza B group because it was previously reported to contain influenza B virus by the local clinical laboratory.

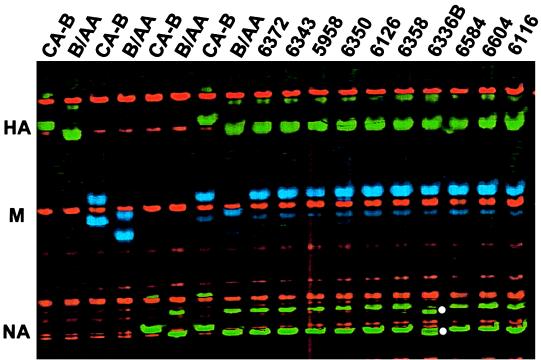

Except for the HA gene of influenza A, all samples were genotyped by RFLP analysis. The HA genes in samples of the influenza A group were genotyped by the generation of HA fragments with primers specific for either H2 (for CA-A) or H3 (for A/WH) subtypes. Several RFLP genotyping uncertainties were later resolved by additional F-SSCP genotyping and sequence analysis (see below). No RT-PCR products were detected for some of the genes, and the yields of some PCR products were determined to be low by ethidium bromide staining. Figure 2 shows the gel electrophoresis of a representative RFLP analysis, in which the M genes of the influenza B sample group were analyzed. The sample of participant 6584 illustrates a failure to produce a specific PCR product. The final genotyping results are summarized in Table 1.

FIG. 2.

A 1% agarose gel showing the RFLP analysis of the M gene of influenza B virus. A nondigested set of products was loaded on the left (NO RE), and the digested corresponding products were loaded on the right (PvuII). Solid triangles highlight the digested patterns of samples 6372 and 6336B.

Based upon the RFLP genotyping, the M gene in sample 6336B appeared to be derived from B/AA and sample 6372 appeared to contain M genes derived from both parental strains, CA-B and B/AA (Fig. 2). Upon further sequence analysis (see below), the M genes of both samples were shown to be derived from CA-B.

Multiplex RT-PCR and F-SSCP genotyping.

The 10 influenza B virus-containing swab specimens identified by the multiplex RT-PCR detection (Table 1) were multiplexed with HA, M, and NA genes and subjected to F-SSCP genotyping as shown in Fig. 3. The results demonstrated that all of the M genes were derived from CA-B and all of the HA genes were derived from B/AA. All of the NA genes, except for one of the samples from participant 6336 (Fig. 3, sample 6336B), were shown to be derived from B/AA. The mobility exhibited in an F-SSCP genotyping is sequence dependent, and a single nucleotide variation can result in a definite mobility shift (2, 12). By sequence analysis (see below), the NA gene in sample 6336B was derived from B/AA, but it contained one point mutation. Unlike RFLP genotyping, F-SSCP genotyping demonstrated that the M genes in samples 6372 and 6336B were derived from CA-B. Further sequence analysis confirmed this conclusion (see below).

FIG. 3.

Gel file of F-SSCP analysis of multiplex RT-PCR products of HA, M, and NA genes of influenza B virus. The RT-PCR products generated in separate reactions for individual genes of the two parental viruses are shown in the first six lanes. The slower moving green bands denote the HA gene, the blue bands denote the M gene, and the faster moving green bands denote the NA gene. Since only one strand was labeled, double bands associated with each gene most likely represented two conformations exhibited by a single molecule. White dots highlight the NA gene of sample 6336B, which exhibited different mobility from those of both CA-B and B/AA.

Sequence analysis.

Various degrees of sequence heterogeneity exist among influenza strains. Directly comparing the nucleic acid sequences between vaccine and parent viruses can provide the absolute identity of the genotype. To efficiently generate DNA templates for sequencing, multiplex RT-PCR was designed to generate short DNA fragments (∼300 bp) of multiple genes in a single reaction. The RNA extracted from the culture supernatants was used in the multiplex RT-PCR for sequencing. Using the nonlabeled set of primers listed in Table 2, the NP, HA, and NA genes of six influenza A isolates and the M, HA, and NA genes of 11 influenza B isolates were amplified. The corresponding gene fragments of the parental viruses were also similarity amplified for sequencing. Samples from participant 6148 of the influenza A group and participants 6126 and 6584 of the influenza B group were not sequenced because the culture supernatants of these samples were consumed during the earlier experiments. No swab specimens remained for sequencing.

The PCR products were sequenced directly without cloning. PCR primers were used as the sequencing primers. All of the sequences generated from each gene were aligned. The results showed that all of the NP genes and M genes were derived from CA-A and CA-B, respectively, and all of the HA genes and NA genes of group A and B samples were derived from A/WH and B/AA, respectively (data not shown). All sequences generated were identical to the parental viruses, except for the NA gene of participant 6336B. When the sequences of CA-B and B/AA were compared, there were 14 nucleotide differences in the sequenced 209-nucleotide region of the NA gene. The NA gene of participant 6336B contained one point mutation when compared to its B/AA parent (data not shown).

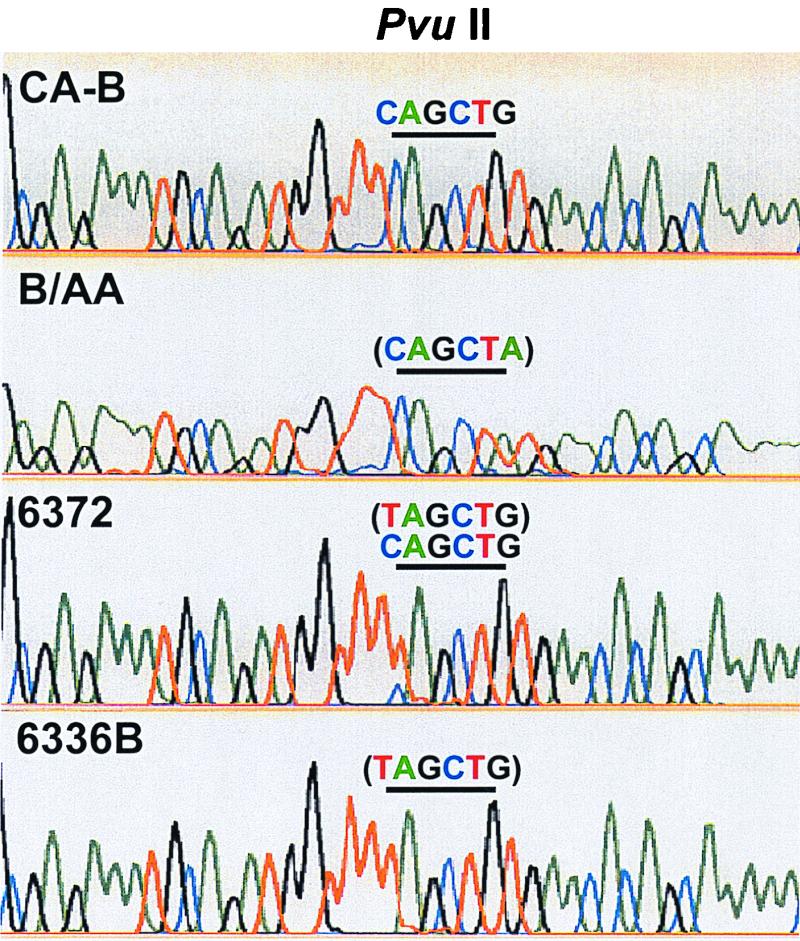

There were 14 nucleotide differences in the sequenced 378-nucleotide region of the M gene between CA-B and B/AA. It did not contain the PvuII restriction site. In order to explain the apparent wild-type M genotype based on the RFLP analysis (not digested by PvuII), which was identified in viruses from participants 6372 and 6336B (Fig. 2), additional sequencing was performed to determine the sequence of the M gene segment, including the PvuII restriction site. Figure 4 shows the section of electropherogram covering the PvuII restriction site. This result was consistent with the F-SSCP and sequence analyses of another region of the M gene (see above) showing that the M genes in viruses from participants 6372 and 6336B were derived from CA-B; however, they contained a point mutation at the PvuII restriction site, resulting in an incorrect identification when analyzed by RFLP. The apparent mixture of vaccine and wild-type M gene RFLP patterns observed in the sample of participant 6372 was actually a mixture of vaccine virus with and without the point mutation, as shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

An alignment of four electropherograms showing the PvuII restriction site. Green, blue, black, and red colors denote A, C, G, and T nucleotides, respectively. The underline marks the position of the restriction site. The sequence enclosed in the parentheses contained nucleotide changes from the PvuII recognition sequence.

DISCUSSION

The FluMist vaccine appeared to be genotypically stable after replication in the human host. As summarized in Table 1, all viruses that had the complete genotyping analysis maintained the 6/2 genotype. They also maintained the ca and ts phenotypes (Table 1), suggesting that they were shed vaccine viruses. All available culture-positive samples, as determined by the local clinical laboratory, that were obtained during the 2-week postvaccination period were studied in this report. As seen in Table 1, no circulating wild-type virus was detected, no H1N1 vaccine virus was detected, and no distinct shedding pattern or duration was observed for the H3N2 and B vaccine viruses. A single nucleotide mutation did occur in each of the M and NA genes of the influenza B virus from participant 6336. The M gene of the virus from participant 6372 contained vaccine virus with and without a point mutation. This approach to postvaccination monitoring provides a comprehensive strategy for direct virus detection, subtyping, analysis of virus shedding patterns, genotyping, and assessment of sequence variations.

It was not surprising that we did not detect wild-type viruses or reassortants between vaccine and wild-type viruses because no wild-type viruses were yet circulating in the community during the period that clinical specimens were collected. In another study, we did detect and genotype wild-type viruses from specimens collected when wild-type influenza virus was circulating in the community (data not shown). In this report, over 11,800 nucleotides representing small regions of the NP, HA, and NA genes of six influenza A isolates and the M, HA, and NA genes of 11 influenza B isolates were deduced. Three nucleotide changes were found. One nucleotide change in the NA gene that did not alter the codon was found in isolate 6336B. One nucleotide change that would direct a Ser-to-Leu codon change in the M gene was also found in isolate 6336B. The M gene of isolate 6327 contained a mixture with and without the same mutation observed in isolate 6336B. We are currently planning full genome sequencing on large numbers of viruses isolated in a prospective study of shedding and transmission. Previously, single gene studies (14) provided evidence that PB2, PB1, PA, and M genes were required for the attenuation of the cold-adapted donor strain of influenza A virus. However, information about the specific nucleotide changes attributable to attenuation was limited (7) and confounded by extragenic suppression and gene constellation effects (15, 16). Therefore, comprehensive full-genome sequencing is necessary initially.

From the technical point of view, several issues should be noted when analyzing clinical samples. RhMK cells were used to culture the virus from the nasal and throat swab specimens, and the culture supernatants were subsequently analyzed. The RhMK cell culture step might reflect the replication potential of the vaccine viruses in the swab specimens. Although no H1N1 shedding was detected in culture supernatants or swab specimens in this study, more extensive analysis is required to determine the shedding pattern, duration, and quantity of the vaccine viruses. RNA virus populations are composed of quasispecies, and the landscape of quasispecies is fluid to environmental changes (8). Additional viral replication in cell culture might cause new mutations or reflect a different landscape of the quasispecies. In this study, sequencing was performed with the culture supernatants. The mutation observed in the NA gene of the participant 6336B sample appeared to be present in the swab specimen as well, as evidenced by the mobility shift observed in the F-SSCP genotyping (Fig. 3). It is not known whether the mutation observed in the M gene of the participant 6336B sample occurred after replication in cell culture. Nevertheless, sequences of quasispecies were observed in the participant 6372 sample, as evidenced by observing mixed M gene sequences, with and without the point mutation (Fig. 4). A direct analysis of the swab specimen without the cell culture step should offer a much better assessment of the sequence variations of the vaccine viruses after replication in the human host.

Two important keys for a successful RT-PCR and RFLP genotyping are primer design and restriction enzyme selection. A good primer design ensures that the amplification of gene fragments is specific and efficient. The selection of more than one restriction enzyme for the analysis of each gene allows the demonstration of more than one distinct restriction pattern for the gene by RFLP genotyping. Using RFLP, any nucleotide mutation that occurs at the restriction site alters the genotype identification. Nucleotide mutations that occur outside the restriction site cannot be assessed. As shown in Fig. 2, RFLP data suggested a possible mixture of wild-type and vaccine viruses or a reversion of the M gene of the vaccine virus to the wild type in two samples. In fact, sequence analysis proved that both of these viruses were vaccine strains.

We have previously reported the utility of a multiplex RT-PCR and F-SSCP genotyping method for analyzing influenza virus reassortants (2). The result in Fig. 3 demonstrates that this method is also applicable to clinical specimens. The multiplex RT-PCR and F-SSCP genotyping offers a different perspective. F-SSCP genotyping is based on the principle that, under nondenaturing conditions, single-stranded DNA assumes unique conformations that are sequence dependent (2, 12). With this method, a single nucleotide mutation that occurs within the PCR fragment causes the fragment to exhibit a different mobility (2). As seen in Fig. 3, the mobility of the NA gene fragment of sample 6336B was different from that of both CA-B and B/AA. Sequence analysis revealed that it was B/AA but contained one point mutation. Genotyping by multiplex RT-PCR and F-SSCP is efficient and cost-effective, with improvements made since our earlier report (2). In our experiences, the newer ABI 377 sequencer increases throughput. With the attachment of an external cooler, gel electrophoresis run time has been reduced from 26 to 6 h, and the single-stranded conformation is better maintained at the lower temperature during runs.

The sample sizes of clinical specimens are often small, and they often contain small amounts of virus. Throughout this study, the multiplexing scheme was designed for direct detection, genotyping, and sequencing. In this way, the information that can be obtained from the irreplaceable clinical specimens is maximized.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Aviron sponsored this study as part of the Collaborative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., and a licensing agreement with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

We thank Robert Belshe, Hunein Maassab, Peter Palese, Bernard Roizman, and John Treanor for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belshe R B, Mendelman P M, Treanor J, King J, Gruber W C, Piedra P, Bernstein D I, Hayden F G, Kotloff K, Zangwill K, Iacuzio D, Wolff M. The efficacy of live attenuated, cold-adapted, trivalent, intranasal influenzavirus vaccine in children. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1405–1412. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805143382002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cha T-A, Zhao J, Lane E, Murray M A, Stec D S. Determination of the genome composition of influenza virus reassortants using multiplex reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction followed by fluorescent single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis. Anal Biochem. 1997;252:24–32. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clements M L. Influenza vaccines. In: Ellis R W, editor. Vaccines: new approaches to immunological problems. Boston, Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992. pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clements M L, Stephens I. New and improved vaccines against influenza. In: Levine M M, Woodrow G C, Kaper J B, Cobon G S, editors. New generation vaccines. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1997. pp. 545–570. [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeBorde D C, Donabedian A M, Herlocher M L, Naeve C W, Maassab H F. Sequence comparison of wild-type and cold-adapted B/Ann Arbor/1/66 influenza virus genes. Virology. 1988;163:429–443. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowdle W R, Schild G C. Laboratory propagation of human influenza viruses, experimental host range, and isolation from clinical material. In: Kilbourne E D, editor. The influenza viruses and influenza. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press; 1975. pp. 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herlocher M L, Clavo A C, Maassab H F. Sequence comparisons of A/AA/6/60 influenza viruses: mutations which may contribute to attenuation. Virus Res. 1996;42:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(96)01292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland J J, De La Torre J C, Steinhauer D A. RNA virus populations as quasispecies. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;176:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77011-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maassab H F, DeBorde D C. Development and characterization of cold-adapted viruses for use as live virus vaccines. Vaccine. 1985;3:355–369. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(85)90124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maassab H F, DeBorde D C, Donabedian A M, Smitka C W. Development of cold-adapted “master” strains for type-B influenza virus vaccines. In: Lerner R A, Chanock R M, Brown F, editors. Vaccines 85. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1985. pp. 327–332. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy B R, Webster R G. Orthomyxoviruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1397–1445. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orita M, Suzuki Y, Sekiya T, Hayashi K. A rapid and sensitive detection of point mutations and genetic polymorphisms using polymerase chain reaction. Genomics. 1989;5:874–879. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(89)90129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakamoto S, Kino Y, Oka T, Herlocher M L, Maassab H F. Gene analysis of reassortant influenza virus by RT-PCR followed by restriction enzyme digestion. J Virol Methods. 1996;56:161–171. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)01909-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snyder M H, Betts R F, DeBorde D, Tierney E L, Clements M L, Herrington D, Sears S D, Dolin R, Maassab H F, Murphy B R. Four viral genes independently contribute to attenuation of live influenza A/Ann Arbor/6/60 (H2N2) cold-adapted reassortant virus vaccines. J Virol. 1988;62:488–495. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.2.488-495.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subbarao E K, Perkins M, Treanor J J, Murphy B R. The attenuation phenotype conferred by the M gene of the influenza A/Ann Arbor/6/60 cold-adapted virus (H2N2) on the A/Korea/82 (H3N2) reassortant virus results from a gene constellation effect. Virus Res. 1992;25:37–50. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(92)90098-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treanor J J, Perkins M, Battaglia R, Murphy B R. Evaluation of the genetic stability of the temperature-sensitive PB2 gene mutation of the influenza A/Ann Arbor/6/60 cold-adapted vaccine virus. J Virol. 1994;68:7684–7688. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7684-7688.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster R G, Bean W J, Gorman O T, Chambers T M, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:152–179. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.152-179.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster R G, Wright S M, Castrucci M R, Bean W J, Kawaoka Y. Influenza—a model of an emerging virus disease. Intervirology. 1993;35:16–25. doi: 10.1159/000150292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]