Results from the recently published meta-analysis by Vai et al. [1]. indicate that psychiatric disorders may be associated with an increased risk of death after SARS-CoV-2 infection (pooled unadjusted OR = 2.00, 95%CI = 1.58–2.54; 23 studies including 43,938 participants with any psychiatric disorder and 1,425,793 control participants). These findings suggest that psychiatric disorders per se may be risk factors of death in COVID-19. However, a critical limitation for interpreting these findings is that only 9 of 23 studies included in that meta-analysis adjusted for a limited number of comorbid medical conditions. Because comorbid medical illnesses are more prevalent in people with psychiatric disorders than in the general population [2] and are associated with increased risk of COVID-19-related mortality [3, 4], this suggests that the association between psychiatric disorders and increased mortality in patients with COVID-19 may be confounded by medical comorbidities.

To examine the potential influence of comorbid medical conditions in the relationship between psychiatric disorders and risk of COVID-19-related mortality, we examined the association between an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis of psychiatric disorder (F01-F99) and mortality in a large multicenter retrospective observational study of patients hospitalized in Greater Paris University hospitals for laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between January 24th, 2020, and May 1st, 2021.

Study design and ethical approval are detailed elsewhere [5–7]. A study flowchart is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. Multivariable logistic regression models adjusting successively for age, sex, hospital, period of hospitalization, current hospitalization status, and number of ICD-10 medical conditions were used. We also performed sensitivity analyses. First, we reproduced the analyses while adjusting for the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI) instead of the number of ICD-10 medical conditions. This index is a method of categorizing comorbidities of patients based on ICD-10 diagnosis codes in which each comorbidity category is dichotomous, i.e. either present or not present. It was initially designed to predict hospital resource use and in-hospital mortality [8]. Second, to assess the potential effect of unmeasured confounding, we computed E-values [9]. The E-value quantifies the minimum strength of association that an unmeasured confounder must have with both the predictor and the outcome, while simultaneously considering the measured covariates, to negate the observed association [9]. The lowest possible E-value is 1 (i.e., no unmeasured confounding is needed to explain away the observed association).

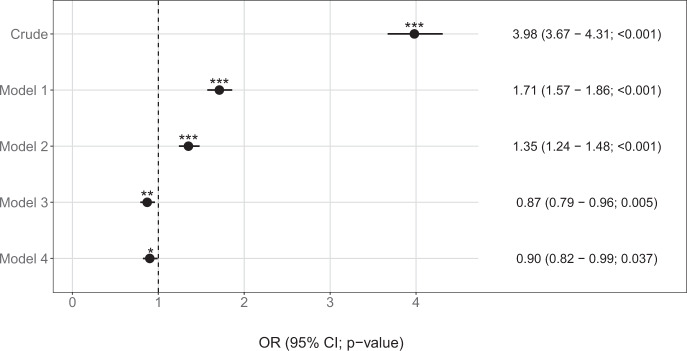

Of 49,089 adult patients hospitalized for COVID-19, 3768 (7.7%) had an ICD-10 diagnosis of psychiatric disorder. Distributions of age, sex, hospital, period of hospitalization, current hospitalization status, and medical comorbidities according to a psychiatric disorder diagnosis, and their associations with mortality are detailed in Supplementary Tables 1–3 and Supplementary Fig. 2. During a median follow-up period of 45 days (SD = 122.1), death occurred in 1001 of 3768 (26.6%) patients with a psychiatric disorder diagnosis versus 3,780 of 45,321 (8.3%) in patients without this diagnosis (OR = 3.98; 95%CI = 3.67–4.31; p < 0.001). Similar to the results of Vai et al [1], this association remained significant but was substantially reduced when adjusting for age and sex (AOR = 1.71; 95%CI = 1.57–1.86; p < 0.001; degrees of freedom (df) = 7). Additional adjustment for hospital, period of hospitalization, and current hospitalization did not alter the significance of the association (AOR = 1.35; 95%CI = 1.24–1.48; p < 0.001; df = 10). However, when further adjusting for the number of medical conditions, this association was significant and reversed (AOR = 0.87; 95%CI = 0.79–0.96; p = 0.005; df = 12) (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 4).

Fig. 1. Association between an ICD-10 diagnosis of psychiatric disorder and mortality among 49,089 adult patients hospitalized for laboratory-confirmed COVID-19.

Crude: unadjusted model; Model 1: adjusted for sex and age [df = 7; all GVIF(1/(2*df) < 1.3]; Model 2: adjusted for sex, age, hospital, period of hospitalization, and current hospitalization status [df = 10; all GVIF(1/(2*df) < 1.2]; Model 3: adjusted for sex, age, hospital, period of hospitalization, current hospitalization status, and number of medical conditions [df = 12; all GVIF(1/(2*df) < 1.3]; Model 4: adjusted for sex, age, hospital, period of hospitalization, current hospitalization status, and the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index [df = 15; all GVIF(1/(2*df) < 1.5]. *Two-sided p value is significant (p < 0.05). ***Two-sided p value is significant (p < 0.001). OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom, GVIF generalized variance inflation factor.

The main results were not substantially modified when adjusting for the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index instead of the number of medical conditions, nor when considering the composite outcome of intubation or death instead of mortality (Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). In the main fully-adjusted model, the E-value was 1.59, with a lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (95%CI) closest to the null point of 1.25, indicating that substantial unmeasured confounding would be required to “explain away” the negative association found between any psychiatric disorder and the outcome. Similarly, in the fully-adjusted model including the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, the E-value was 1.46, with a lower limit of the 95%CI of 1.11.

Our study has several limitations. First, an inherent bias in observational studies is unmeasured confounding. To try to minimize the effects of confounding, we performed the analyses while adjusting for several known confounders and did an e-value analysis. However, data on several potential confounders, including baseline severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection, treatments that patients received, and certain sociodemographic characteristics, such as socioeconomic status, were not available for most patients included in these analyses. Second, there is a potential underreporting of psychiatric disorders and medical comorbidities in our sample in a context of overwhelmed hospital units during the peak incidences. Third, diagnoses of psychiatric disorders were based on ICD-10 diagnosis codes and not ascertained by psychiatrists. Finally, despite the multicenter design, our results may not be generalizable to outpatients and other countries.

Despite these limitations, our results suggest that among patients hospitalized for COVID-19, those with psychiatric disorders have increased risk of death, which could be explained by their greater number of medical conditions. In addition, by suggesting a possible negative association after adjusting for age, sex, comorbid medical disorders, hospital, period of hospitalization, and current hospitalization, our findings might help reconciliate findings from Vai et al. [1]. and recent in-vitro [10], observational [5, 6], and clinical ones [11, 12], including the preliminary findings from the TOGETHER trial [13], suggesting that certain antidepressants, such as fluvoxamine and fluoxetine, could be beneficial against COVID-19 [14]. Biological mechanisms that may contribute to this potential effect include functional inhibition of the acid sphingomyelinase/ceramide system [14, 15], agonist effect for Sigma-1 receptors [16], reduction in platelet aggregation, decreased mast cell degranulation, and interference with endolysosomal viral trafficking [16].

Our findings support that individuals suffering from both psychiatric disorders and comorbid medical conditions should be vaccinated against COVID-19 and benefit from prevention and treatment of medical risk factors of severe COVID-19 as a priority. Future studies taking into account main medical risk factors of severe COVID-19, i.e. age and all medical comorbidities, will be important to determine whether the risk of COVID-19-related mortality is similar or different across psychiatric diagnoses and psychotropic medications prescribed.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the EDS APHP Covid consortium integrating the APHP Health Data Warehouse team as well as all the APHP staff and volunteers who contributed to the implementation of the EDS-Covid database and operating solutions for this database. Collaborators of the EDS APHP Covid consortium: Pierre-Yves ANCEL, Alain BAUCHET, Nathanaël BEEKER, Vincent BENOIT, Mélodie BERNAUX, Ali BELLAMINE, Romain BEY, Aurélie BOURMAUD, Stéphane BREANT, Anita BURGUN, Fabrice CARRAT, Charlotte CAUCHETEUX, Julien CHAMP, Sylvie CORMONT, Christel DANIEL, Julien DUBIEL, Catherine DUCLOAS, Loic ESTEVE, Marie FRANK, Nicolas GARCELON, Alexandre GRAMFORT, Nicolas GRIFFON, Olivier GRISEL, Martin GUILBAUD, Claire HASSEN-KHODJA, François HEMERY, Martin HILKA, Anne Sophie JANNOT, Jerome LAMBERT, Richard LAYESE, Judith LEBLANC, Léo LEBOUTER, Guillaume LEMAITRE, Damien LEPROVOST, Ivan LERNER, Kankoe LEVI SALLAH, Aurélien MAIRE, Marie-France MAMZER, Patricia MARTEL, Arthur MENSCH, Thomas MOREAU, Antoine NEURAZ, Nina ORLOVA, Nicolas PARIS, Bastien RANCE, Hélène RAVERA, Antoine ROZES, Elisa SALAMANCA, Arnaud SANDRIN, Patricia SERRE, Xavier TANNIER, Jean-Marc TRELUYER, Damien VAN GYSEL, Gaël VAROQUAUX, Jill Jen VIE, Maxime WACK, Perceval WAJSBURT, Demian WASSERMANN, Eric ZAPLETAL.

Author contributions

Study protocol: NH, MS-R, FL. Formal analysis: NH, MS-R, JJ-HM, PdlM. Writing—original draft: NH, MS-R. Writing—review & editing: JJ-HM, PdlM, EG, JK, AC, KAB, CC, FL.

Data availability

Data from the AP-HP Health Data Warehouse can be obtained upon request at https://eds.aphp.fr//.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Patients′ consent

This observational study using routinely collected data received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the AP-HP clinical data warehouse (decision CSE-20-20_COVID19, IRB00011591, April 8th, 2020). AP-HP clinical Data Warehouse initiatives ensure patient information and consent regarding the different approved studies through a transparency portal in accordance with European Regulation on data protection and authorization n°1980120 from National Commission for Information Technology and Civil Liberties (CNIL).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41380-021-01393-7.

References

- 1.Vai B, Mazza MG, Delli Colli C, Foiselle M, Allen B, Benedetti F, et al. Mental disorders and risk of COVID-19-related mortality, hospitalisation, and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021:S2215036621002327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Alegria M, Jackson JS, Kessler RC, Takeuchi D Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES), 2001-2003 [United States]: Version 7. 2007.

- 3.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:576–8. doi: 10.7326/M20-5661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoertel N, Sánchez-Rico M, Vernet R, Beeker N, Jannot A-S, Neuraz A, et al. Association between antidepressant use and reduced risk of intubation or death in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: results from an observational study. Mol Psychiatry. 2021. 10.1038/s41380-021-01021-4. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33536545. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hoertel N, Sánchez‐Rico M, Gulbins E, Kornhuber J, Carpinteiro A, Lenze EJ, et al. Association Between FIASMAs and Reduced Risk of Intubation or Death in Individuals Hospitalized for Severe COVID-19: An Observational Multicenter Study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021: 10.1002/cpt.2317. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34050932; PMCID: PMC8239599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Hoertel N, Sánchez‐Rico M, Vernet R, Beeker N, Neuraz A, Alvarado JM, et al. Dexamethasone use and mortality in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a multicenter retrospective observational study. Br J Clin Pharm. 2021;87:3766–75. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. PMID: 9431328. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Haneuse S, VanderWeele TJ, Arterburn D. Using the E-value to assess the potential effect of unmeasured confounding in observational studies. JAMA. 2019;321:602. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carpinteiro A, Edwards MJ, Hoffmann M, Kochs G, Gripp B, Weigang S, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase prevents uptake of SARS-CoV-2 by epithelial cells. Cell Rep Med. 2020;1:100142. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100142. Epub 2020 Oct 29. PMID: 33163980; PMCID: PMC7598530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Lenze EJ, Mattar C, Zorumski CF, Stevens A, Schweiger J, Nicol GE, et al. Fluvoxamine vs placebo and clinical deterioration in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:2292–2300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seftel D, Boulware DR. Prospective cohort of fluvoxamine for early treatment of coronavirus disease 19. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab050. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reis G, Dos Santos Moreira-Silva EA, Silva DCM, Thabane L, Milagres AC, Ferreira TS, et al. Effect of early treatment with fluvoxamine on risk of emergency care and hospitalisation among patients with COVID-19: the TOGETHER randomised, platform clinical trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2021:S2214-109X(21)00448-4. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00448-4. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34717820; PMCID: PMC8550952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Hoertel N, Sánchez-Rico M, Cougoule C, Gulbins E, Kornhuber J, Carpinteiro A, et al. Repurposing antidepressants inhibiting the sphingomyelinase acid/ceramide system against COVID-19: current evidence and potential mechanisms. Mol Psychiatry. 2021:1–2. 10.1038/s41380-021-01254-3. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34385600; PMCID: PMC8359627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Kornhuber J, Hoertel N, Gulbins E The acid sphingomyelinase/ceramide system in COVID-19. Mol Psychiatry. 2021:1–8. 10.1038/s41380-021-01309-5. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34608263; PMCID: PMC8488928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Sukhatme VP, Reiersen AM, Vayttaden SJ, Sukhatme VV. Fluvoxamine: a review of its mechanism of action and its role in COVID-19. Front Pharm. 2021;12:652688. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.652688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data from the AP-HP Health Data Warehouse can be obtained upon request at https://eds.aphp.fr//.