Abstract

Introduction:

Integrated care aims to improve access, quality and continuity of services for ageing populations and people experiencing chronic conditions. However, the health and social care workforce is ill equipped to address complex patient care needs due to working and training in silos. This paper describes the extent and nature of the evidence on workforce development in integrated care to inform future research, policy and practice.

Methods:

A scoping review was conducted to map the key concepts and available evidence related to workforce development in integrated care.

Results:

Sixty-two published studies were included. Essential skills and competencies included enhancing workforce understanding across the health and social care systems, developing a deeper relationship with and empowering patients and their carers, understanding community needs, patient-centeredness, health promotion, disease prevention, interprofessional training and teamwork and being a role model. The paper also identified training models and barriers/challenges to workforce development in integrated care.

Discussion and Conclusion:

Good-quality research on workforce development in integrated care is scarce. The literature overwhelmingly recognises that integrated care training and workforce development is required, and emerging frameworks and competencies have been developed. More knowledge is needed to implement and evaluate these frameworks, including the broader health and social care workforces within a global context. Further research needs to focus on the most effective methods for implementing these competencies.

Keywords: integrated care, health workforce, workforce development, scoping review

Introduction

Internationally, governments have committed to integrated health systems to improve access, quality and continuity of services for our increasingly ageing population and people experiencing chronic disease [1,2,3]. Patients with ongoing health problems need continuous care and treatment across settings and providers [Pruitt & Epping-Jordan 2005, as cited in 1]. Growing evidence supports an integrated approach between healthcare and other sectors, emphasising a person-centred, preventative and community-based approach rather than disease-based and institution-focused care [1]. An integrated approach requires workers from several sectors to collaborate with patients, carers and each other to develop personalised treatment plans that reflect patient and family needs, preferences and community resource and service availability [4,5,6, Pruitt and Epping—Jordan 2005, as cited in 1]. Moreover, in 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed a global framework on integrated people-centred health services. The framework imposed five interdependent strategies: empowering and engaging people and communities, strengthening governance and accountability, reorienting care models, coordinating services within and across sectors and creating an enabling environment [7].

Before evaluating the research into workforce development in integrated care, some definitions are needed. The WHO defines integrated care as:

The management and delivery of health services such that people receive a continuum of health promotion, health protection and disease prevention services, as well as diagnosis, treatment, long-term care, rehabilitation, and palliative care services through the different levels and sites of care within the health system and according to their needs [7].

By ‘health and social care workforce’, we mean ‘the different kinds of clinical and non-clinical staff responsible for public and primary health interventions’ [7].

Barriers to implementing integrated services are well-described in the literature. They include a lack of clear, systematic understanding of integrated care among key stakeholders [8] and a lack of standardised, validated tools and indicators to measure integration [3]. Previous research also describes workforce challenges, including an existing, entrenched workforce culture, limited opportunities for cooperation and communication, interprofessional education, resistance to share care, high costs, staff skills and information technology systems [9,10,11].

Similar barriers exist in workforce development. For example, training curricula for healthcare workers do not promote experience and skills in community and integrated care settings [12,13]. Students learn primary care principles in many training programmes but are then placed in clinical environments where it is difficult to implement and practice those principles [14]. Limited access to experts inhibits the scaling up of existing competencies and curricula [4]. Faculty expertise, financial, organisational and logistical factors are other recognised barriers to implementing integrated curricula into healthcare workers’ training [15,10,11]. Training still emphasises the diagnosis and treatment of acute diseases, fragmented, outdated and static curricula, and education and practice that focus on component elements of an issue or disease [16].

Professionals need to manage health and care rather than disease and cure. To work in teams across professions and sectors, they need to acquire a non-traditional set of knowledge, skills and attitudes [8]. Although the literature contains many models and examples of integrated care systems in different settings and populations, there is insufficient discussion of how the health and social care workforce have prepared and trained to work within these settings [9,11]. Therefore, this article systematically reviews the literature on workforce development, including characteristics, models, key competencies, barriers, challenges and global recommendations. The review is the first component of a broader project to develop an international education-focused framework for health and social care professional education.

Methods

A scoping review was selected to map the key concepts and available evidence of how education, training and workforce development in integrated care systems have been implemented and represented in the literature. The goal is to synthesise the research into education and training by mapping or articulating current knowledge about these critical concepts derived from various study designs. A scoping review is particularly relevant in this field, as emerging evidence makes it challenging to undertake systematic reviews [17]: and scoping reviews allow for a broader range of study types to be included [18]. As a result, the method allows for knowledge strengths and gaps to be identified and set within policy and practice contexts.

The research questions, protocol, scoping review process and inclusion criteria for the search strategy were developed in consultation with a group of experts with knowledge of integrated care and working in health and social science. These experts assisted with the initial review of full articles for inclusion and a descriptive numerical summary of the evidence. The scoping review followed Levac’s [17] recommendations, Arksey and O’Malley’s [18] five-stage protocol and the Joanna Briggs Institute Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist [19]. The five stages of this scoping review consisted of the following: (1) defining the research questions and purpose, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) data charting and (5) the collation, summarising and reporting of results [18].

Stage 1: Defining the Research Questions and Purpose

A broad question, key concepts, target audience and intended outcome, were defined for the study (see Table 1). Although an integrated workforce includes many stakeholders (such as government, social support sectors, including education and housing and individuals’ families and communities), the scoping review focuses on the training of health and social care workers.

Table 1.

Scoping Review Methods.

|

| |

|---|---|

| SCOPING REVIEW STAGE | METHODS |

|

| |

| (1) Defined the research questions and purpose |

|

|

| |

| (2) Identified relevant studies |

|

|

| |

| (3) Selected studies |

|

|

| |

| (4) Charted the data |

|

|

| |

| (5) Collated, summarised and reported the results | |

|

| |

Notes: MeSH = Medical subject heading.

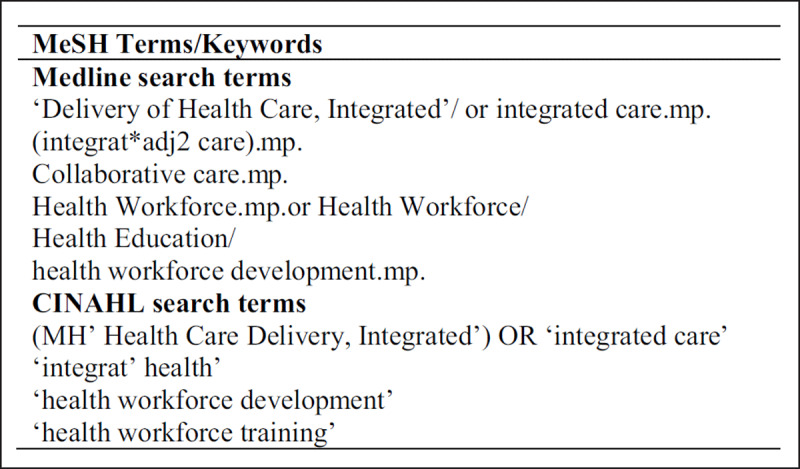

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

All search strategies and databases (see Table 1) were developed with the lead researcher and context experts from the scoping study team, as Levac et al. [17] recommended. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in April 2020, followed by the complete search strategy with all identified search terms in May 2020. The words, truncations and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms used and combined for the PubMed search are shown in Figure 1. The final set of databases was selected for their multi-disciplinary content and inclusion of health and social services. The review only includes studies published after 2013 when the definition of integrated care used by the WHO and adopted for the present study was introduced.

Figure 1.

Literature Review Keywords and MeSH Terms.

Notes: MeSH = Medical subject heading.

Stage 3: Study Selection

The search strategy (see Table 1) was refined through ongoing discussions with the research team. From here, empirical and non-empirical articles were included in the final selection of studies and these were analysed to define the extent, range and nature of the material available.

Stage 4: Charting the Data

Table 1 shows the data that was extracted from the selected studies. These fields were chosen to outline the scoping review process.

Stage 5: Collation, Summary and Reporting Results

Key results included a list of themes and competencies for workforce training on integrated care and a list of identified training models (see Table 1). Thematic analysis was used to identify the themes and findings of the study. These were articulated into tables to make it easier for the reader to interpret [17].

Results

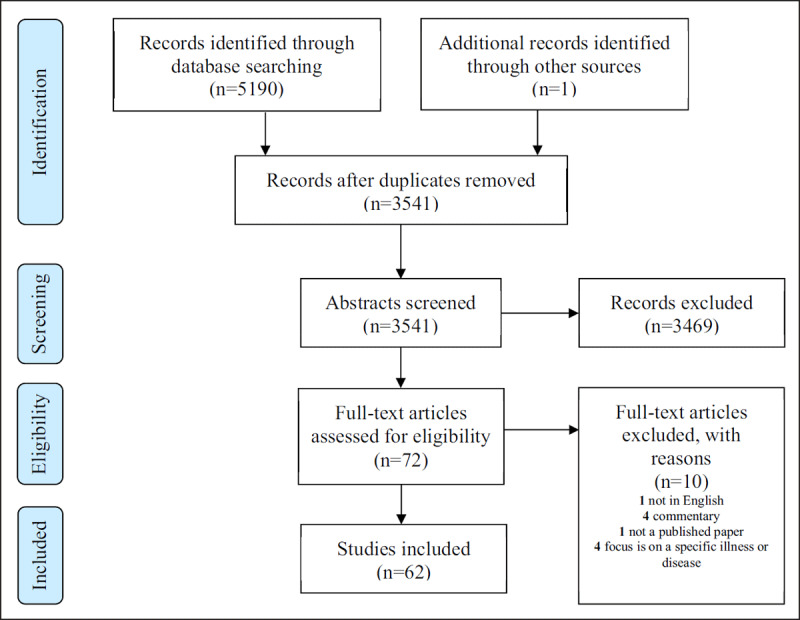

The peer-reviewed literature on integrated care and workforce development is sparse, despite international recommendations for preparing the health and social care workforce to work within this model [1,2,3,7]. A total of 5,190 records were first identified in the database search, after which 3,541 records remained following duplicate removal (see Figure 2). The final full-text screening yielded 62 records (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Database Search Results.

Descriptive Characteristics

Most selected studies were empirical and demonstrated systematic collection and analysis of evidence. In contrast, the non-empirical studies included personal reflections, observations, an editorial, a book chapter and systematic reviews (see Table 2). Most studies originated from the United States and Europe (see Table 2). Sixteen of the studies related to training clinicians, such as social workers and psychologists, targeting individuals with mental health or substance abuse conditions.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Selected Studies (n = 62).

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| CHARACTERISTIC | TOTAL N (%) | RELEVANT STUDIES |

|

| ||

| Type of study | ||

|

| ||

| Empirical | 33 (53) | |

|

| ||

| Non-empirical | 29 (47) | |

|

| ||

| Region | ||

|

| ||

| United States | 29 (47) | |

|

| ||

| Europe | 16 (25) | |

|

| ||

| United Kingdom | 7 (11) | |

|

| ||

| Canada | 5 (8) | |

|

| ||

| International | 3 (5) | |

|

| ||

| Africa | 1 (2) | |

|

| ||

Target Workforce

The literature represented workforce groups that generally focused on one or two disciplines. Most common were behavioural health clinicians specialising in mental health conditions, including psychologists, social workers and medical practitioners. Other groups were leaders [20,21], managers [21], primary care professionals [22], expert clinicians [23,24,25,26,27], healthcare students [5], medical graduates [23,28], physicians [29], social service providers in the community [26], health and social care workers or behavioural health providers [29,30,31,32] and educators and academics [23,20]. For example, one study described an integrated care training programme for social workers alongside community social service providers [26].

Skills and Competencies

Essential skills and competencies were identified and are summarised in Table 3. These include enhancing workforce understanding across the health and social care systems, developing a deeper relationship with patients and their families, patient-centeredness, health promotion, disease prevention and interprofessional education and teamwork.

Table 3.

Competencies, Themes and References.

|

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| THEMES | SKILLS AND COMPETENCIES | REFERENCES | |

|

| |||

| 1 | Deeper understanding of our health and social care systems | Enhance workforce understanding of and exposure to alignment of activities across both the health and social care systems | [16,33,11] |

|

| |||

| 2 | Deeper understanding of our health and social care systems | Enable workforce attitudes to proactively pursue depth to understand system complexity and how to access services | [15,33,34,11] |

|

| |||

| 3 | Deeper understanding of our patients | Skills to construct a comprehensive understanding of individual patients’ complex needs and how these can be met within their surrounding health and social care systems | [34,3,11,13,36] |

|

| |||

| 4 | Deeper understanding of our communities | An understanding of how social and cultural factors affect health | [4] |

|

| |||

| 5 | Deeper understanding of our communities | Consideration for concerns specific to vulnerable populations and their needs | [34] |

|

| |||

| 6 | Deeper understanding of our patients | Skills to actively pursue depth and continuously asking ‘why’ (rather than just ‘what’ or ‘how’) to construct a deep understanding of individual patients (their perceptions, beliefs and psychosocial context) and the system within which they interact | [34,35,11] |

|

| |||

| 7 | Deeper understanding of our patients | A holistic understanding of individuals’ health and wellbeing, capabilities, self-management abilities, needs, preferences and the environment in which they find themselves, including recognition that an individual’s situation is dynamic, not static and requires regular monitoring | [31,34,35,36] |

|

| |||

| 8 | Deeper understanding of our patients | Skills to establish a longitudinal alliance with the patient and functional relationships with colleagues | [27,28,31,35,11,36] |

|

| |||

| 9 | Enhanced understanding of systems and available resources | Extensive integrated knowledge of biopsychosocial aspects of disease, systems of care and social determinants of care | |

|

| |||

| 10 | Enhanced understanding of systems and available resources | Understanding how to apply knowledge of the major determinants of health given resources available, relevant health policies and system design within a community | |

|

| |||

| 11 | Caregiver involvement | Involvement of and communication with caregivers. An active approach to caregiver wellness, including understanding risk factors, recognising signs of caregiver distress, assessing caregiver needs and referring caregivers to care | [16,34,35,37] |

|

| |||

| 12 | Caregiver involvement | Direct provision of psychosocial care to caregivers across a spectrum of needs inclusive of bereavement | [4,34] |

|

| |||

| 13 | Enhanced understanding of systems and available resources | Familiarity with local and national resources to support social needs and can connect patients and caregivers to such resources, including community-based partners | [4] |

|

| |||

| 14 | Enhanced understanding of systems and available resources | Collaborate with community-based partners to improve patient care. Skill development to collaborate with other health providers outside specialist settings | [4,16,33,34,44,11] |

|

| |||

| 15 | Illness prevention | Health promotion and disease prevention, including knowledge of and referral to preventative facilities and local programmes and support for lifestyle interventions | [15,37,39,40,11] |

|

| |||

| 16 | Enhanced understanding of systems and available resources | Embrace individuals, communities and services as partners in care | [5,33] |

|

| |||

| 17 | A person-focused approach that considers the patient’s presenting problem and other medical issues | [5,13,36] | |

|

| |||

| 18 | Focuses on the needs of individuals, families and communities to improve their quality of care, health outcomes and wellbeing | ||

|

| |||

| 19 | Empowering patients | Support patients in their involvement in their care by empowering them with knowledge and skills per their capabilities | [5,11,13] |

|

| |||

| 20 | Patient-centred and relationship-centred care | [15,5,35] | |

|

| |||

| 21 | Interprofessional teamwork | Work effectively as a member of an interprofessional team | [15,5,33,11,41,36] |

|

| |||

| 22 | Collaborate with individuals and families to develop a personalised care plan to promote health and wellbeing that incorporates integrative approaches, including lifestyle counselling and mind–body strategies | [15] | |

|

| |||

| 23 | Empowering patients and communities | Facilitate behaviour change in individuals, families and communities to achieve ways of living that promote health, resilience, wellbeing and disease prevention | [15] |

|

| |||

| 24 | Obtain an integrative health history that includes mind–body–spirit, nutrition and use of both conventional and integrative therapies | [15] | |

|

| |||

| 24 | Role models | Practice self-care | [15] |

|

| |||

| 25 | Demonstrate basic knowledge of the major health professions, both integrative and conventional | [15] | |

|

| |||

| 26 | Demonstrate skills to incorporate integrative healthcare into community settings and the healthcare system at large Value continuous learning, become mentors, teachers and peer learners |

[15,36] [33,11] |

|

|

| |||

| 27 | Patient centredness | Patient centredness; understanding and facilitating patients’ pathways through the care system | [15,5,36] |

|

| |||

| 28 | Collaborating with other providers; strong communication and collaboration skills and the ability to develop strong working relationships with team members are imperative | [24,5,42,43,44] | |

|

| |||

| 29 | Health promotion and disease prevention | Community-based health education, health promotion and disease prevention | [15,40,45] |

|

| |||

| 30 | Health promotion and disease prevention | Knowledge of how to teach patients self-care strategies to stay healthy and how to incorporate the patient’s strengths and resources within their care plan | [15,37] |

|

| |||

| 31 | Understanding individuals’ roles in the integrated healthcare team and the ability to articulate this role to other team members | [24,5,36] | |

|

| |||

Models to Support Education and Training

The studies describe several models for education and training, varying by target audience and methods (see Table 4). For example, one study developed a framework for action in the WHO European region, developing competency clusters and a competency consolidation cycle [36]. Another study reported developing a 40-hour online module with course content appropriate for a range of primary care practitioners. The focus was on incorporating these competencies into existing curricula [15]. A further study suggested infusing integrated care content into existing curricula, building foundational knowledge, and developing elective courses to enhance and develop integrated care expertise [24]. The literature also described a 26-item validated tool to measure three areas of integrated care expertise among health and social care professionals: (1) generalism, representing the patient, (2) coaching to empower patients to self-manage their care and (3) population health orientation and prevention [46].

Table 4.

Models of Training.

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| MODEL | RELEVANT STUDIES | |

|

| ||

| 1 | Scale up existing competencies among all practitioners to deliver more integrated care | [15,30,13,36] |

|

| ||

| 2 | Incorporate integrated care concepts organically, so that they are fundamental to delivering care | |

|

| ||

| 3 | Create a working environment that values wellness and creates a climate of respect and work-life balance | [14,36] |

|

| ||

| 4 | Engage faculty teaching staff who convey joy in their work and provide trainees with education around work-life balance, self-reflection and self-improvement | [14] |

|

| ||

| 5 | Embed structures to support collaboration and interprofessional learning among colleagues and professions across services, strengthening multisector relationships; multi-organisation training | [33,47,48,11,36] |

|

| ||

| 6 | Incorporate simulation-based scenarios using actors from the local community with lived experiences | [49] |

|

| ||

| 7 | Incorporate education and support for caregivers, including prevention of health problems and improving quality of life. For example, implement a weekly meeting for caregivers to discuss topics related to the experiences of the patients’ healthcare and their self-care needs | [37] |

|

| ||

| 8 | Allow more time for networking, interprofessional education and opportunities for individual service presentations and diverse attendance, including the social care and voluntary sectors | [47,50,36] |

|

| ||

| 9 | Case studies, exercises and simulations are encouraged to allow students to interact with the content in as realistic a venue as possible | [42] |

|

| ||

| 10 | Focus on soft skills, such as communication, teamwork and relationship building | [5,34,13,41] |

|

| ||

| 11 | Focus on skills to build durable relationships with patients, other professionals and caregivers | [5,34] |

|

| ||

| 12 | Focus on self-management promotion and skills, including the use of motivational interviewing techniques | [34] |

|

| ||

| 13 | Skills to navigate the health and social care systems and work on individualised care plans and assessments | [30,34,47,13] |

|

| ||

| 14 | Ongoing mentorship | [38,51] |

|

| ||

| 15 | Workplace training, including interprofessional education, strategies for new staff, such as providing an integrated care manual and shadowing opportunities for the new staff member to be placed with different professionals across sectors and services | [51,36] |

|

| ||

| 16 | Workplace training, including team meetings, mutual education about workflow or processes or a review of a problematic shared case | [51,52,41,36] |

|

| ||

| 17 | Short courses, such as motivational interviewing | |

|

| ||

| 18 | Understanding of primary care providers, including how to interface and refer clients | [14] |

|

| ||

| 19 | Interprofessional skill development and education for faculty and a willingness and ability for faculty to evaluate and update curriculum in line with changes within the healthcare environment | [16,53,13,36] |

|

| ||

| 20 | Blended learning approaches that use discussions among participants, role play, problem-based learning and case application | [15] |

|

| ||

| 21 | Provide opportunities for students and healthcare workers to develop interpersonal and interprofessional strategies to consult, coordinate and collaborate routinely in practice | [5,28,41] |

|

| ||

| 22 | Create opportunities and a focus on building relationships and care pathways with organisations in the community | [44,11] |

|

| ||

| 23 | Include opportunities for critical thinking and reflective practice and the use of case presentations and role-plays | [16] |

|

| ||

| 24 | Create opportunities for all disciplines to train, think, create and seek solutions as a unit | [16,28,36] |

|

| ||

| 25 | Create an environment where there is a willingness to think differently about how services are delivered to meet the changing needs and expectations of people using health and social care services | [54] |

|

| ||

| 26 | Opportunities for broader and more meaningful engagement across health and social care | [54,57] |

|

| ||

| 27 | Incorporate and encourage innovative training and development that spans across health and social care | [54,36] |

|

| ||

| 28 | Design clinical practice environments to support and enable continuous learning that benefits not just learners, but also patients, communities and providers | [9] |

|

| ||

| 29 | Provide opportunities for participants to gain placement experience engaging in team-based assessments and intervention strategies | [24] |

|

| ||

In addition to competency training, an emerging health professional education model was suggested to guide integrated workforce development and expansion [23]. Another study used a Delphi method to explore what skills were needed for doctors in training to practice integrated behavioural health, resulting in a list of 21 competencies [29]. A behavioural science approach was used to implement a behaviour change wheel to upskill health and social care staff to focus on preventative, community-based integrated care [40].

The literature highlighted the importance of knowledge transfer and leadership [47,21,11,36] and suitable learning environments [14]. Students need to be placed within primary healthcare environments to learn the principles of integrated care and develop meaningful, long-term connections with patients. Conversely, implementing and these principles in clinical environments is challenging [14].

Barriers and Challenges

Table 5 summarises barriers and challenges identified in the studies to workforce development in integrated care. These barriers include a lack of understanding of integrated care instead of focusing on siloed health and social care systems and training in acute healthcare systems.

Table 5.

Barriers/Challenges.

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| BARRIER/CHALLENGE | RELEVANT STUDIES | |

|

| ||

| 1 | Siloed competency domains and traditionally siloed health systems | [18,50,43] |

|

| ||

| 2 | Current curricula do not promote the acquisition of experience and skills in the community and integrated care settings | [7] |

|

| ||

| 3 | Fragmented, outdated and static curricula | |

|

| ||

| 4 | Systems that allow only limited and narrow functional relationships with colleagues | [50] |

|

| ||

| 5 | Professional training programmes do not adequately prepare clinicians to work in a collaborative and integrative setting | |

|

| ||

| 6 | A small number of professionals may receive training within a short course or generalist training programme, but this represents a limited number of professions who are field-ready after their studies | |

|

| ||

| 7 | The general nature of integrated care and learning about other services may not align with the expectations of specialty training | [7,50] |

|

| ||

| 8 | A lack of consultant-led integrated services, restricting consultant supervision and workforce development in such services | [7] |

|

| ||

| 9 | In many training programmes, students learn the principles of primary care but are then placed in clinical environments where it is challenging to implement and practice those principles | [8] |

|

| ||

| 10 | Current curricula for higher medical trainees do not promote the acquisition of experience and skills working across services and within integrated care settings | [7] |

|

| ||

| 11 | Emphasis on using standardised clinical pathways and specialists who do not fully understand and are unable to facilitate patients’ pathways through the care system | [29,41,51] |

|

| ||

| 12 | Time, budget, organisational and logistic constraints and a lack of access to experts to provide training | [9,10] |

|

| ||

| 13 | Training still relies on models that emphasise diagnosis and treatment of acute diseases | |

|

| ||

| 14 | Hospital specialists seem unaware of general practice conditions, focusing on disease treatment without considering the daily life of the patient and the existence of comorbidities | [52] |

|

| ||

| 15 | A lack of a shared system to facilitate transfer of information across settings and time constraints are major barriers to effective care transitions | [52] |

|

| ||

| 16 | Observing patients at different disease stages indirectly affected goal setting | [52] |

|

| ||

| 17 | The rigid separation of disciplines at the educational level results in a process that can lead to discontent, animosity, fragmented learning, fragmented practice and, subsequently, fragmented care | [24] |

|

| ||

| 18 | Although health and social care staff may value joint working to improve quality of care, interprofessional collaboration did not occur routinely due to organisational limitations | [26] |

|

| ||

| 19 | Employees and organisations had limited understanding of integrated care practices | [48] |

|

| ||

Recommendations

Practice recommendations identified from this scoping review are broadly categorised into the following: (1) student selection, (2) faculty selection, (3) curriculum design, (4) workplace, (5) community participation and (6) health system (see Supplemental Table 1).

Good health and social care depend on the workforce overcoming barriers identified in this scoping review and accepting that the biomedical model alone cannot satisfy modern health care [61]. Moreover, health and social services need to be integrated and work effectively together, focusing on preventing rather than curing [62]. Further, the scoping review shows that implementing an integrated information system accessible to all health professionals is central to integrating care in workforce development [60,11,13,36]. The review also found consensus that respect and trust are essential to successful collaboration and that time is required to build and sustain these qualities [60,21,13].

Workforce planning and interprofessional education and practice is essential when implementing a system in integrated care and must be designed around patients and populations, not professions [9,21,11], representing a shift away from silo-based analyses of workforce needs. Instead, different professional groups have flexible, dynamic and overlapping practice areas [6]. Thus, workforce planning should include traditional health professions like nurses and physicians and workers employed in health and social care [9,11,41]. Similarly, Aiello and Mellor [48] recommend collective action that connects local innovation and best practice within consistent national frameworks to meet the aspirations of multi-professional health and care workforce across local systems. Such action requires a joined-up, transformational approach at strategic and operational levels from workforce planners and commissioners to enable integrated health care at scale [48,36].

Discussion

The literature embraces workforce alignment of activities across health and social systems and settings [8,26] and expands expertise in integrated care education to develop leaders and role models [20,21,23,64,11,36]. Studies also report implementing joint assessments and interprofessional training to overcome interprofessional barriers to a lack of communication and understanding of job roles [30,21,11,36]. Overcoming these barriers will enable participants from both health and social care settings to understand their roles and identify the needs of complex service users [30]. However, the literature does not provide detailed descriptions of how to implement this training. In addition to competency training, one study recommended an emerging health professional education model to guide integrated workforce development and expansion [23]. This model promotes adaptive expertise as a conceptual framework for training healthcare providers to deeply understand patient and system complexity while upholding a patient-centred approach [23]. Adaptive expertise uses more experienced healthcare providers’ extensive knowledge to solve known (routine) and new, complex problems [6]. Implementing an interprofessional education framework [23] will support health and social care providers proactively thinking beyond professional tasks and standardised pathways. Building deeper relationships with patients and more functional relationships with colleagues and other service providers will result in an integrated knowledge of biopsychosocial aspects of disease and systems and social determinants of care [33,11].

The selected studies suggested that training programmes need to incorporate caregiver training, education and support [20], although detailed descriptions of how to implement this training were not provided. Moreover, few studies mentioned patient, carer or community participants actively collaborating to design and deliver the education programmes, which is one of the key principles of integrated care [1].

Only small-scale studies limited to specific health professionals such as physicians, psychologists and social workers were found in this scoping review. Those found were based predominantly in the United States or Europe. Thus, the literature provides no examples from resource-poor countries, international studies or consensus from a range of experts across countries and professions. The selected studies favoured siloed approaches with no studies mentioning other professions such as nursing, allied health and social care. Traditional siloed models no longer provide an appropriate response to patient need. Therefore, we need to find ways to use, prepare and train the more comprehensive health and care workforce to manage an ever-increasing and diverse patient population.

The literature is primarily composed of journal articles presenting opinions along with literature reviews. The selected studies were descriptive but general about the nature of workforce development in integrated care. Descriptions of education and training were predominately aimed at highly qualified and academically trained professionals, especially doctors and social workers. A limited number of studies specifically discussed workforce competencies and education and training models but primarily addressed management and leadership. Education and training need to considerably move up the ladder of priorities if we want to achieve sustainable integrated care in the next generation.

Although a range of competency tools and education frameworks have been developed [36], no studies discuss the implementation and evaluation of these frameworks or measure competency over time. Implementing a regulatory framework for learning environments and organisations will enable workforce changes and integrated care models [20]. The engagement of professional bodies and associations in developing competency frameworks would also help [36]. New leadership, management and professional roles, new working environments and cross-professional and cross-sectoral collaboration are required to execute these changes [20,21,64,36].

What Would the Perfect Integrated Care Workforce Look Like?

It helps to have a clear understanding of the characteristics of an ideal collaborative practitioner. The results from this scoping review suggest that in the perfect workplace, health and social care providers have the capacity and knowledge to create personalised solutions for people who present with complex issues and follow standardised health pathways and protocols [4,5,6]. These providers understand national and local systems of care [4,33] but are also willing to challenge and negotiate how health care is provided. They work well within and can collaborate with an interprofessional and intersectoral team [4,15,16,21,33,34,38,64,11,41]. They know and understand their community’s needs and have the time and knowledge to teach and role model to patients, families, carers and communities the self-care strategies they require to stay healthy, rather than wait for a disease to develop [15,16,34,37,39,40]. An ideal healthcare provider involves their patients in all aspects of care and can actively incorporate their strengths and resources into their care plan [15,21,27,5,31,64,11]. Focusing on health promotion and disease prevention, [15,40,45] the ideal healthcare provider manages the patients’ health and care rather than disease and cure and empowers patients and their families to stay well. These health and social care providers also value continuous learning and are mentors, teachers and peer-learners.

Conclusions

This scoping review has highlighted significant gaps in the research to describe and evaluate workforce training and integrated care development. The knowledge gaps cannot be solved effectively by collecting data across the United States and European countries and focusing on similar disciplines. A global plan is needed to understand the leadership requirements, implementation processes, evaluation outcomes and policy levers to create an integrated, people-centred workforce within diverse healthcare systems and sectors. There is an urgent need to develop new academic programmes, competencies and training models, knowledge transfer, and leadership to build a people-centred health workforce and a more integrated healthcare and social care sector approach. Investments are needed in research and implementation studies to foster a greater understanding of the actual content of care required within these new systems. Practice recommendations identified from this scoping review include: (1) student selection, (2) faculty selection, (3) curriculum design, (4) workplace, (5) community participation and (6) health system.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

Supplemental Table 1 Recommendations for Workforce Development in Integrated Care.

Reviewers

Cara English, DBH, CEO, Cummings Graduate Institute for Behavioral Health Studies, USA.

Monica Sørensen, The Norwegian Directorate of Health and OsloMet University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Norway.

Funding Information

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this scoping review.

Competing Interests

VS is a joint editor-in-chief for the International Journal of Integrated Care. All other authors have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Amelung VE, Stein V, Goodwin N, Balicer R, Nolte E, Suter E. Handbook of integrated care. Switzerland: Springer; 2017. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-56103-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell G, Burridge L, Zhang J, Donald M, Scott I, Dart J, et al. Systematic review of integrated models of health care delivered at the primary–secondary interface: How effective is it and what determines effectiveness? Aust J Prim Health. 2015; 21: 391–408. DOI: 10.1071/PY14172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, Bruijnzeels MA. Understanding integrated care: A comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integr Care. 2013; 13(1). DOI: 10.5334/ijic.886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shalev D, Docherty M, Spaeth-Rublee B, Khauli N, Cheung S, Levenson J, et al. Bridging the behavioral health gap in serious illness care: Challenges and strategies for workforce development. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020; 28(4): 448–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsson JE, Berkel LA, Chong BW. Integrated health care and counseling psychology: An introduction to the major contribution. Couns Psychol. 2019; 47(7): 999–1011. DOI: 10.1177/0011000019896795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sockalingam S, Mulsant BH, Mylopoulos M. Beyond integrated care competencies: The imperative for adaptive expertise. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016; 43(2016): 30–1. DOI: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe & Health Services Delivery Programme, Division of Health Systems and Public Health. ROADMAP. Strengthening people-centred health systems in the WHO European region: A framework for action towards coordinated/integrated health services delivery (CIHSD) [Internet]; 2013. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/231692/e96929-replacementCIHSD-Roadmap-171014b.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein KV. Developing a competent workforce for integrated health and social care: What does it take? Int J Integr Care. 2016; 16(4): 9. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.2533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraher E, Brandt B. Toward a system where workforce planning and professional practice and education are designed around patients and populations not professions. J Interprof Care. 2019; 33(4): 389–97. DOI: 10.1080/13561820.2018.1564252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busetto L, Luijkx K, Calciolari S, González-Ortiz LG, Vrijhoef HJM. The development, description and appraisal of an emergent multimethod research design to study workforce changes in integrated care interventions. Int J Integr Care. 2017: 17(1). DOI: 10.5334/ijic.2510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busetto L, Calciolari S, González Ortiz LG, Luijkx K, Vrijhoef B. Integrated care and the health workforce. In: Amelung V, Stein V, Goodwin N, Balicer R, Nolte E, Suter E (eds.), Handbook integrated care. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. 2017; 209–20. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-56103-5_13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell C, Lawrence E, Lim S. Preparing the future medical workforce for community and integrated medical care. Future Hosp J. 2015; 2(Suppl 2): s24. DOI: 10.7861/futurehosp.2-2-s24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen DJ, Balasubramanian BA, Davis M, Hall J, Gunn R, Stange KC, et al. (2015). Understanding care integration from the ground up: Five organising constructs that shape integrated practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015; 28(Suppl 1): S7–20. DOI: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassel C, Wilkes M. Location, location, location: Where we teach primary care makes all the difference. J Gen Intern Med. 2017; 32(4): 411–5. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-016-3966-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks AJ, Koithan MS, Lopez AM, Klatt M, Lee JK, Goldblatt E, et al. Incorporating integrative healthcare into interprofessional education: What do primary care training programs need? J Interprof Educ Pract. 2019; 14: 6–12. DOI: 10.1016/j.xjep.2018.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuipers P, Ehrlich C, Brownie S. Responding to health care complexity: Suggestions for integrated and interprofessional workplace learning. J Interprof Care. 2014; 28(3): 246–8. DOI: 10.3109/13561820.2013.821601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2015; 5(9): 69. DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005; 8(1): 19–32. DOI: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 169(7): 467–73. DOI: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nieuwboer MS, van der Sande R, van der Marck MA, Older Rikkert MG, Perry M. Clinical leadership and integrated primary care: A systematic literature review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2019; 25(1): 7–18. DOI: 10.1080/13814788.2018.1515907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller R, Stein KV. The odyssey of integration: Is management its Achilles’ heel? Int J Integr Care. 2020; 20(1): 7. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.5440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks AJ, Chen M-K, Goldblatt E, Klatt M, Kliger B, Koithan MS, et al. Introducing integrative primary health care to an interprofessional audience: Feasibility and impact of an asynchronous online course. Explore. 2020; 16(6): 392–400. DOI: 10.1016/j.explore.2019.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sockalingam S, Chaudhary ZK, Barnett R, Lazor J, Mylopoulos M. Developing a framework of integrated competencies for adaptive expertise in integrated physical and mental health care. Teach Learn Med. 2020; 32(2): 159–67. DOI: 10.1080/10401334.2019.1654387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Held ML, Black DR, Chaffin KM, Mallory KC, Diehl AM, Cummings S. Training the future workforce: Social workers in integrated health care settings. J Soc Work Educ. 2019; 55(1): 50–63. DOI: 10.1080/10437797.2018.1526728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada AM, Wenzel SL, DeBonis JA, Fenwick KM, Holguin M. Experiences of collaborative behavioral healthcare professionals: Implications for social work education and training. J Soc Work Educ. 2019; 55(3): 519–36. DOI: 10.1080/10437797.2019.1593900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin M, Kilgore RC. Integrated care workforce development: University–community collaboration. Soc Work Educ. 2019; 39(4): 534–51. DOI: 10.1080/02615479.2019.1661987 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reno R, Beaujolais B, Davis TS. Facilitating mechanisms for integrating care to promote health equity across the life course: Reflections from social work trainees. Soc Work Health Care. 2019; 58(1): 60–74. DOI: 10.1080/00981389.2018.1531105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manusov EG, Marlowe DP, Teasley DJ. Learning to walk before we run: What can medical education learn from the human body about integrated care. Int J Integr Care. 2013; 13: e018. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin M, Allison L, Banks E, Bauman D, Harsh J, Cahill A, et al. Essential skills for family medicine residents practicing integrated behavioral health a Delphi Study. Fam Med. 2019; 51(3): 227–33. DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.743181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser MW. Elephant in the room: Inter-professional barriers to integration between health and social care staff. J Integr Care. 2019; 27(1): 64–72. DOI: 10.1108/JICA-07-2018-0046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nummela O, Juujärvi S, Sinervo T. Competence needs of integrated care in the transition of health care and social services in Finland. Int J Care Coord. 2019; 22(1): 36–45. DOI: 10.1177/2053434519828302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis TS, Reno R, Guada J, Swenson S, Peck A, Saunders-Adams S, et al. Social Worker Integrated Care Competencies Scale (SWICCS): Assessing social worker clinical competencies for health care settings. Soc Work Health Care. 2019; 58(1): 75–92. DOI: 10.1080/00981389.2018.1547346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dale J, Russell R, Harkness F, Wilkie V, Aiello M. Extended training to prepare GPs for future workforce needs. Br J Gen Pract. 2017; 67(662): E659–67. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp17X691853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leijten FRM, Struckman V, van Ginnekan E, Czypionka T, Kraus M, Reiss M, et al. The SELFIE framework for integrated care for multi-morbidity: Development and description. Health Policy. 2018; 122(1): 12–22. DOI: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menichetti J, Pitacco G, Graffigna G. Exploring the early-stage implementation of a patient engagement support intervention in an integrated-care context—a qualitative study of a participatory process. J Clin Nurs. 2019; 28(5–6): 997–1009. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.14706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langins M, Borgermans L. Strengthening a competent health workforce for the provision of coordinated/integrated health services. Int J Integr Care. 2016; 16(6): 1–2. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.2779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.da Silva Siqueira RM, Rolan Loureiro MD, Pereira Frota O, Ferreira Júnior MA. Health education practice in the view of information caregivers in integrated continuing care. J Nurs. 2017; 11(8): 3079–86. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sunderji N, Ion A, Huynh D, Benassi, Ghavam-Rassoul A, Carvalhal A. Advancing integrated care through psychiatric workforce development: A systematic review of educational interventions to train psychiatrists in integrated care. Can J Psychiatry. 2018; 63(8): 513–25. DOI: 10.1177/0706743718772520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Black DR. Preparing the workforce for integrated healthcare: A systematic review. Soc Work Health Care. 2017; 56(10): 914–42. DOI: 10.1080/00981389.2017.1371098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bull ER, Hart JK, Swift J, Baxter K, McLauchlan N, Joseph S, et al. An organisational participatory research study of the feasibility of the behaviour change wheel to support clinical teams implementing new models of care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019; 19(1): 97. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-019-3885-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen DJ, Davis M, Balasubramanian BA, Gunn R, Hall J, DeGruy 3rd FV, et al. Integrating behavioral health and primary care: Consulting, coordinating and collaborating among professionals. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015; 28(Suppl 1): S21–31. DOI: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larimer SG, Sullivan WP, Wahler B, McCabe H. No more silos: Animating integrated health and behavioral health care practices in the classroom. J Teach Soc Work. 2018; 38(4): 363–78. DOI: 10.1080/08841233.2018.1503216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stanhope V, Heyman J, Amarante J, Doherty M. Integrated behavioral health care. In: Heyman J, Congress E (eds.), Health and social work: Practice, policy, and research. New York: Springer; 105–24. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoge MA, Morris JA, Laraia M, Pomerantz A, Farley T. Core competencies for integrated behavioral health and primary care. Washington, DC: SAMHSA–HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leyns CC, de Maeseneer J, Willems S. Using concept mapping to identify policy options and interventions towards people-centred health care services: A multi stakeholders’ perspective. Int J Equity Health. 2018; 17(1): 177. DOI: 10.1186/s12939-018-0895-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Aa MJ, van den Broeke J, Stronks K, Busschers WB, Plochg T. Measuring renewed expertise for integrated care among health- and social-care professionals: Development and preliminary validation of the ICE-Q questionnaire. J Interprof Care. 2016; 30(1): 56–64. DOI: 10.3109/13561820.2015.1057271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuhlmann E, Batenburg R, Wismar M, Dussault G, Maier CB, Glinos IA, et al. A call for action to establish a research agenda for building a future health workforce in Europe. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018; 16(1): 52. DOI: 10.1186/s12961-018-0333-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aiello M, Mellor JD. Integrating health and care in the 21st century workforce. J Integr Care. 2019; 27(2): 100–10. DOI: 10.1108/JICA-09-2018-0061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Craig SL, McInroy LB, Bogo M, Thompson M. Enhancing competence in health social work education through simulation-based learning: Strategies from a case study of a family session. J Soc Work Educ. 2017; 53: S47–58. DOI: 10.1080/10437797.2017.1288597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alexander EC, de Silva D, Clarke R, Peachey M, Manikam L. A before and after study of integrated training sessions for children’s health and care services. Health Soc Care Community. 2018; 26(6): 801–9. DOI: 10.1111/hsc.12588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenberg T, Mullin D. Building the plane in the air … horizontal ellipsis but also before and after it takes flight: Considerations for training and workforce preparedness in integrated behavioural health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2018; 30(6): 199–209. DOI: 10.1080/09540261.2019.1566117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ricketts TC, Fraher EP. Reconfiguring health workforce policy so that education, training, and actual delivery of care are closely connected. Health Aff. 2013; 32(11): 1874–80. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boland DH, Juntunen CL, Kim HY, Adams EM, Navarro RL. Integrated behavioral health curriculum in counseling psychology training programs. Couns Psychol. 2019; 47(7): 1012–36. DOI: 10.1177/0011000019895293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCririck V, Hughes R. Local education and training boards: Key messages for promoting integrated care. J Integr Care. 2013; 21(3): 157–63. DOI: 10.1108/JICA-11-2012-0050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi RJ, Betancourt RM, DeMarco MP, Bream KDW. Medical student exposure to integrated behavioral health. Acad Psychiatry. 2019; 43(2): 191–5. DOI: 10.1007/s40596-018-0936-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plochg T, Ilinca S, Noordegraaf M. Beyond integrated care. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2017; 22(3): 195–7. DOI: 10.1177/1355819617697998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacobson SL. Preparing our graduates: Pittsburgh’s approach to training in integrated care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017; 56(10): S106. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mattison D, Weaver A, Zebrack B, Fischer D, Dubin L. Educating social workers for practice in integrated health care: A model implemented in a graduate social work program. J Soc Work Educ. 2017; 53(Suppl 1): S72–86. DOI: 10.1080/10437797.2017.1288594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McDermott C, Shank K, Shervinskie C, Gonzalo JD. Developing a professional identity as a change agent early in medical school: The students’ voice. J Gen Intern Med. 2019; 34(5): 750–3. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-019-04873-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lyngsø AM, Godtfredsen NS, Frølich A. Interorganisational integration: Healthcare professionals’ perspectives on barriers and facilitators within the Danish healthcare system. Int J Integr Care 16. 2016; 16(1): 4. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.2449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barbazza E, Langins M, Kluge H, Tello J. Health workforce governance: Processes, tools and actors towards a competent workforce for integrated health services delivery. Health Policy. 2015; 119(12): 1645–54. DOI: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hurst K, Patterson DK. Health and social care workforce planning and development—an overview. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014; 27(7): 562–72. DOI: 10.1108/IJHCQA-05-2014-0062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Orchard C, Bainbridge L. Competent for collaborative practice: What does a collaborative practitioner look like and how does the practice context influence interprofessional education? J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2016; 11(6): 526–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2016.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller R, Stein KV. Building competencies for integrated care: Defining the landscape. Int J Integr Care. 2017; 17(6): 6. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.3946 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chesluk B, Tollen L, Lewis J. Physicians’ voices: What skills and supports are needed for effective practice in an integrated delivery system? a case study of kaiser permanente. Inquiry. 2017; 54: 1–10. DOI: 10.1177/0046958017711760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1 Recommendations for Workforce Development in Integrated Care.