Abstract

Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic. In addition to unfavorable perinatal outcomes, there has been an increase in obstetric interventions. With this study, we aimed to clarify the reasons, using Robson’s classification model, and risk factors for cesarean section (C-section) in SARS-CoV-2-infected mothers and their perinatal results. This was a prospective observational study that was carried out in 79 hospitals (Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group) with a cohort of 1704 SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive pregnant women that were registered consecutively between 26 February and 5 November 2020. The data from 1248 pregnant women who delivered vaginally (vaginal + operative vaginal) was compared with those from 456 (26.8%) who underwent a C-section. C-section patients were older with higher rates of comorbidities, in vitro fertilization and multiple pregnancies (p < 0.05) compared with women who delivered vaginally. Moreover, C-section risk was associated with the presence of pneumonia (p < 0.001) and 41.1% of C-sections in patients with pneumonia were preterm (Robson’s 10th category). However, delivery care was similar between asymptomatic and mild–moderate symptomatic patients (p = 0.228) and their predisposing factors to C-section were the presence of uterine scarring (due to a previous C-section) and the induction of labor or programmed C-section for unspecified obstetric reasons. On the other hand, higher rates of hemorrhagic events, hypertensive disorders and thrombotic events were observed in the C-section group (p < 0.001 for all three outcomes), as well as for ICU admission. These findings suggest that this type of delivery was associated with the mother’s clinical conditions that required a rapid and early termination of pregnancy.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, pregnancy, delivery, C-section, Robson’s ten group, perinatal outcomes, pneumonia

1. Introduction

In March 2020, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) to have caused a pandemic [1,2]. SARS-CoV-2 infects mainly through respiratory droplets, binds to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor and enters lung epithelial cells causing severe pathogenesis. Most people with a fully functional immune system who are exposed to SARS-CoV-2 undergo asymptomatic infection, while 5–10% are symptomatic and 1–2% are critically affected. These severely affected patients display a cytokine storm due to a dysfunctional immune response, which brutally destroys the affected organs and can lead to death [3]. Older people or people with comorbidities are high-risk population groups; however, pregnant women should also be included in this category, as the immunological and physiological changes of pregnancy make them more vulnerable to respiratory infections [4].

It is now known that SARS-CoV-2 infection presents a similar clinical picture in pregnant women to non-pregnant women, and only a small percentage of the former develop pneumonia due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (0–14%) and severe maternal and neonatal complications [5]. Hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, previous cardiopulmonary diseases and older maternal age are among the risk factors that have been described to be associated with complicated COVID-19 disease in this population [2].

Regarding the mode of delivery, a high rate of cesarean sections (C-sections) was observed in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the early phases of the pandemic [6,7,8,9]. A C-section is a mode of delivery through an open abdominal incision (laparotomy) and an incision in the uterus (hysterotomy), before the removal of the fetus begins; it requires anesthesia and follow-up car [10]. This high rate of C-sections early in the pandemic seemed to be associated with severe COVID-19 pathology and a lack of knowledge of this disease.

Most international obstetrics and gynecology guidelines state that vaginal delivery in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients is safe [11] and, when a C-section is performed, it should be based on obstetric indications. However, although the frequency of C-sections has decreased throughout the pandemic, the rates in SARS-CoV-2 infected mothers remain high (above 25%), and significantly higher than those registered in non-infected mothers [12,13].

Furthermore, the indiscriminate use of C-sections in delivery care is a global public health problem and it is not associated with a reduction in maternal or neonatal mortality [14]. In order to characterize the reasons underlying the high use of C-sections in different settings in a standardized manner, Robson’s international classification has been widely implemented [15,16]. This system determines the clinical data that are needed to classify C-sections in different groups, which allows for further comparison and identification of C-sections’ rate trends. It is a 10-group classification model that is based on four obstetric parameters: previous obstetric history (previous deliveries and C-sections), onset of labor (spontaneous, induced or elective C-section), gestational category (multiple pregnancy or singleton pregnancy, with cephalic, breech or transverse presentation) and gestational age (in labor).

Because of the existing doubt about a possible association of C-section with a subsequent worsening of the mother’s condition in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, as described early in the pandemic [17], the present study was proposed. This study included pregnant women that were infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the three high-incidence waves of the pandemic in Spain (26 February 2020 to 30 April 2021), where the objective was to define the characteristics of the mothers who needed a C-section and to investigate the reasons using Robson’s classification model, risk factors for C-section in infected mothers and their perinatal results.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Here we present a multicenter prospective study, where consecutive cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a pregnancy cohort that were registered by 79 Spanish hospitals (members of the Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group, listed in Supplementary Table S1) were analyzed. The study procedures were approved by the Drug Research and Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Puerta de Hierro University Hospital (Madrid, Spain) on 23 March 2020 (protocol registration number, 55/20); afterward, each collaborating center obtained local protocol approval. The study protocol is available at ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier: NCT04558996. Informed consent was obtained from every mother that was willing to participate in the study.

In order to record the information needed, a specific database was designed for the study and used by the lead researcher of each participating center. The data were entered after the delivery of each patient. STROBE guidelines for cohort studies were followed for the duration of the study (Supplementary Table S2) [18].

2.2. Study Participants

The recruitment took place between 26 February and 5 November 2020. Every pregnant woman that attended the participating hospitals and was diagnosed as positive for SARS-CoV-2 was included in the cohort. SARS-CoV-2 infection was diagnosed using positive double-sampling polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from nasopharyngeal swabs; this test was applied in suspicious cases that arrived at hospital due to compatible COVID-19 symptoms and to every woman at admission in the delivery ward (universal screening, which started on 1 April 2020), regardless of whether they had COVID-19 in the past. These patients were subsequently classified according to their gestational age at the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection (1st, 2nd or 3rd trimester of gestation), as well as their COVID-19 symptomatology upon diagnosis, i.e., asymptomatic or symptomatic, with the latter stratified into mild–moderate symptoms (cough, anosmia, fatigue/discomfort, fever, dyspnea, etc.) and pneumonia.

2.3. Recorded Information

The demographic characteristics, comorbidities and obstetric history of the study participants were extracted from their clinical history; afterward, the classification used by the CDC (Centers for Disease Control Prevention) was followed for age and race categorization [4]. We recorded the following perinatal events: the type of onset of labor and delivery, gestational age at delivery, preterm delivery (below 37 weeks), ICU admission and need for invasive mechanical ventilation, obstetrical complications (pre-eclampsia, hemorrhagic and thrombotic events) and maternal mortality. In addition, C-sections were characterized using Robson’s classification system [15,16]. On the other hand, neonatal data involved the five-minute Apgar score, umbilical artery pH, birth weight, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and neonatal mortality. The definition of the recorded clinical and obstetric conditions followed international criteria [14,19,20]. Patients were followed until six weeks postpartum; the last delivery registered in our database took place on 30 April 2021. Neonatal events were recorded until 14 days postpartum.

These infected patients were then divided into two groups based on the type of delivery: C-section vs. vaginal + operative vaginal delivery.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Numerical variables were tested for a normal distribution with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were used for describing numerical variables; frequencies and percentages were used for categorical ones. The comparison between groups of interest was carried out using Mann–Whitney’s U test for numerical variables and Pearson’s chi-squared or Fisher´s exact test for categorical variables. Statistical tests were two-sided and were performed with SPSS V.20 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA); a p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In addition, multivariable logistic regression modeling was conducted in order to derive the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of “C-section risks factors” found in the previous univariable analysis. The regression analysis was carried out using the Ime4 package in R, version 3.4 (RCoreTeam, 2017) [21].

3. Results

3.1. Results for the Entire SARS-CoV-2-Infected Cohort

3.1.1. General Data

During the study period, a total of 1704 pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection were diagnosed, either because of suspicious symptoms or during admission to the delivery room.

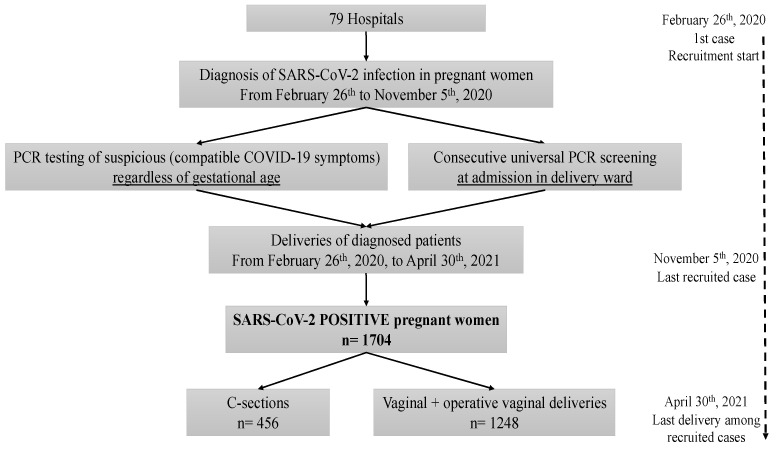

Of the 1704 SARS-CoV-2 positive women, 26.8% (456/1704) underwent a C-section and 73.2% (1248/1704) delivered vaginally, either via vaginal (1071, 62.9%) or operative vaginal (177, 10.4%) deliveries (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study data.

3.1.2. Baseline Characteristics, Maternal Comorbidities and Pregnancy Characteristics

The maternal age of the women who underwent a C-section was statistically higher than the group of women who delivered vaginally (p < 0.001); of the former, up to 44.3% were older than 35 years (Table 1).

A higher proportion of nulliparous and smokers was observed in the C-section group (Table 1).

A higher proportion of pregnant women with comorbidities (obesity, thrombophilia, chronic kidney disease and diabetes mellitus) was observed among those who underwent a C-section (Table 1).

There were significantly more IVF and multiple pregnancies observed in the C-section group (Table 1), in addition to more cases of intrauterine growth restrictions and gestational hypertension (p = 0.002 and p < 0.001, respectively).

A total of 8.2% of women in the C-section group were classified as high risk for pre-eclampsia (by screening at 11–14 weeks of gestation) compared to 5.3% of women who delivered vaginally (p = 0.038, Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, comorbidities and current obstetric history of the study participants (n = 1704).

| Infected Cohort | Vaginal + Operative Vaginal | C-Section | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 1704 | 1248 (73.2) | 456 (26.8) | ||

| Maternal Characteristics | |||||

| Maternal age (years; median/IQR) | 32 (28–36) | 32 (27–36) | 34 (29–37) | <0.001 * | |

| Age Range | 18–24 years | 241/1689 (14.3) 825/1689 (48.8) 623/1689 (36.9) |

188 (15.2) 627 (50.6) 423 (34.2) |

53 (11.8) 198 (43.9) 200 (44.3) |

0.001 * |

| 25–34 years | |||||

| 35–49 years | |||||

| Ethnicity | White European | 947/1699 (55.7) 514/1699 (30.3) 44/1699 (2.6) 50/1699 (2.9) 144/1699 (8.5) |

689/1245 (55.3) 374/1245 (30.0) 34/1245 (2.7) 39/1245 (3.1) 109/1245 (8.8) |

258/454 (56.8) 140/454 (30.8) 10/454 (2.2) 11/454 (2.4) 35/454 (7.7) |

0.816 |

| Latino Americans | |||||

| Black non-Hispanic | |||||

| Asian non-Hispanic | |||||

| Arab | |||||

| Nulliparous | 616/1688 (36.5) | 431/1233 (35.0) | 185/455 (40.7) | 0.031 * | |

| Smoking a | 160 (9.7) | 105 (8.7) | 55 (12.7) | 0.016 * | |

| Maternal Comorbidities | |||||

| Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | 317 (18.6) | 203 (16.3) | 114 (25.0) | <0.001 * | |

| Thrombophilia | 28 (1.6) | 15 (1.2) | 13 (2.9) | 0.018 * | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.9) | 0.047 * | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 36 (2.1) | 20 (1.6) | 16 (3.5) | 0.015 * | |

| Current Obstetric History | |||||

| Multiple pregnancy | 31 (1.8) | 12 (1.0) | 19 (4.2) | <0.001 * | |

| In vitro fertilization | 82 (4.8) | 37 (3.0) | 45 (9.9) | <0.001 * | |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 61 (3.6) | 34 (2.7) | 27 (5.9) | 0.002 * | |

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension b | 42 (2.5) | 20 (1.6) | 22 (4.8) | <0.001 * | |

| High-risk pre-eclampsia screening | 90/1484 (6.1) | 58/1095 (5.3) | 32/389 (8.2) | 0.038 * | |

Data shown as n (% of total), except otherwise indicated. * Statistically significant differences. BMI: body mass index; HBP: high blood pressure. a Current smokers + ex-smokers. b Hypertension + pre-eclampsia.

3.1.3. Gestational Age at the Moment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Diagnosis

Of the 1704 SARS-CoV-2-positive women in our cohort, 92 (5.4%) were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection in the first trimester of gestation, 292 (17.1%) in the second trimester and 1320 (77.5%) in the third trimester.

The rates of C-sections among patients who were diagnosed in the first, second and third trimester of gestation were 16.35% (15/92), 24.7% (72/292) and 28.0% (369/1320), respectively, with the risk of a cesarean section being significantly higher when the infection took place late in pregnancy (p = 0.034).

3.1.4. Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes

Gestational age at delivery was significantly lower among women who underwent a C-section (p < 0.001, Table 2), with higher rates of preterm delivery (<37 weeks of gestational age) in this group (23.5% vs. 6.3% of patients who delivered vaginally, p < 0.001).

A higher incidence of obstetric and medical complications (hemorrhagic events, hypertensive disorders and thrombotic events) was observed among patients who underwent a C-section (Table 2), as well as of ICU admissions and requirement of invasive mechanical ventilation (Table 2).

There were two cases of maternal death among the patients of the C-section group, both of which were associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation, and none in the vaginal delivery group (p = 0.071).

Higher rates of newborns with low Apgar scores, low umbilical artery pH and NICU admissions were observed in the C-section group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Maternal and neonatal outcomes of the study participants (n = 1704).

| Infected Cohort | Vaginal + Operative Vaginal | C-Section | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 1704 | 1248 (73.2) | 456 (26.8) | |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks + days; median/IQR) | 39 + 7 (38 + 2 to 40 + 3) |

39 + 4 (38 + 4 to 40 + 1) |

39 + 0 (37 + 0 to 40 + 1) |

<0.001 * |

| Hemorrhagic events Abruptio placentae Postpartum hemorrhage |

93 (5.5) 18 (1.1) 79 (4.6) |

48 (3.8) 1 (0.1) 47 (3.8) |

45 (9.9) 17 (3.7) 32 (7.0) |

<0.001 * <0.001 * 0.005 * |

| Hypertensive disorders Antepartum/postpartum hypertension Pre-eclampsia/eclampsia Moderate pre-eclampsia Severe pre-eclampsia/HELLP/eclampsia |

104/1661 (6.3) 87 (5.1) 56/87 (64.4) 31/87 (35.6) |

50/1222 (4.1) 42 (3.4) 30/42 (71.4) 12/42 (28.6) |

54/439 (12.3) 45 (9.9) 26/45 (57.8) 19/45 (42.2) |

<0.001 * <0.001 * 0.184 |

| Thrombotic events Deep venous thrombosis Pulmonary embolism Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

18 (1.1) 3 (0.2) 10 (0.6) 6 (0.4) |

6 (0.5) 1 (0.1) 3 (0.2) 2 (0.2) |

12 (2.6) 2 (0.4) 7 (1.5) 4 (0.9) |

<0.001 * 0.176 0.005 * 0.047 * |

| Admitted in ICU | 52 (3.1) | 7 (0.6) | 45 (9.9) | <0.001 * |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 31 (1.8) | 3 (0.2) | 28 (6.1) | <0.001 * |

| Maternal Mortality | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0.071 |

| Neonatal Score | ||||

| Apgar 5 score < 7 Umbilical artery pH < 7.10 Birth weight (grams; median/IQR) |

17/1661 (1.0) 44/1359 (3.2) 3260 (2900–3570) |

3/1218 (0.2) 25/989 (2.5) 3290 (2940–3560) |

14/443 (3.2) 19/370 (5.1) 3170 (2628–3595) |

<0.001 * 0.016 * <0.001 * |

| Admitted in NICU | 163/1684 (9.7) | 70/1234 (5.7) | 93/450 (20.7) | <0.001 * |

| Neonatal mortality | 6 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.9) | 0.047 * |

Data shown as n (% of total), except otherwise indicated. * Statistically significant differences.

3.2. Results for the Third Trimester Infections

3.2.1. COVID-19 Symptomatology and Delivery Characteristics

More than a third of the patients had labor induced regardless of COVID-19 symptomatology (Table 3) and only 38.4% of patients who developed pneumonia had a spontaneous onset.

The type of delivery varied according to COVID-19 symptomatology: the proportions of C-sections among the asymptomatic patients, the ones who had COVID-19 mild–moderate symptoms and the ones who developed pneumonia were 23.5, 28.1 and 40.8%, respectively (p < 0.001, Table 3).

Among the patients who underwent a C-section (a total of 369), 38 (10.3%) were admitted to the ICU, whereas only 0.6% of patients who delivered vaginally (6/951) needed intensive care (p < 0.001).

Regarding Robson’s classification of C-sections, there was a higher proportion of patients belonging to the 4th (multiparous without previous C-section, singleton pregnancy with cephalic presentation, ≥37 weeks’ gestation) and the 10th (singleton pregnancy with cephalic presentation, <37 weeks’ gestation, including those who had one or more previous C-section) categories among those who developed pneumonia (Table 3).

Of the patients who developed pneumonia, underwent a C-section and belonged to Robson’s fourth category, 77.8% had an induced labor and 22.2% had a programmed C-section.

Only 17.9% (17/95) of patients with pneumonia and who underwent a C-section had a spontaneous onset of labor.

The highest proportion of asymptomatic patients who underwent a C-section belonged to Robson’s second category (24.7%: nulliparous women, singleton pregnancy with cephalic presentation, ≥37 weeks’ gestation, induced labor or programmed C-section) and mild–moderate symptomatic patients to the fifth category (22.5%: multiparous women with previous C-section, singleton pregnancy with cephalic presentation, ≥37 weeks’ gestation, spontaneous onset of labor).

Nearly one-third of patients who developed pneumonia and underwent a C-section were admitted to the ICU (30/95, 31.6%); from these, 66.7% (20/30) underwent a C-section before ICU admission and 33.3% (10/30) afterward (Table 3).

Table 3.

Description of the onset of labor, mode of delivery and the reasons for C-section categorized by the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients infected in the 3rd trimester of gestation (n = 1320).

| Asymptomatic | Mild–Moderate Symptoms | Pneumonia | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 689 (52.2) | 398 (30.2) | 233 (17.7) | |

| Onset of labor: Programmed C-section Spontaneous Induced |

46 (6.7) 392 (56.9) 251 (36.4) |

46 (11.6) 199 (50.0) 153 (38.4) |

54/232 (23.3) 89/232 (38.4) 89/232 (38.4) |

<0.001 * |

| Type of delivery: Vaginal Operative vaginal C-section |

450 (65.3) 77 (11.2) 162 (23.5) |

242 (60.8) 44 (11.1) 112 (28.1) a |

119 (51.1) 19 (8.2) 95 (40.8) |

<0.001 *,b |

| Robson classification of C-sections: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

15/162 (9.3) 40/162 (24.7) 14/162 (8.6) 21/162 (13.0) 30/162 (18.5) 12/162 (7.4) 12/162 (7.4) 4/162 (2.5) 1/162 (0.6) 13/162 (8.0) |

8/111 (7.2) 20/111 (18.0) 10/111 (9.0) 12/111 (10.8) 25/111 (22.5) 9/111 (8.1) 6/111 (5.4) 5/111 (4.5) 0/111 (0.0) 16/111 (14.4) |

2/95 (2.1) 10/95 (10.5) 5/95 (5.3) 18/95 (18.9) 10/95 (10.5) 5/95 (5.3) 2/95 (2.1) 4/95 (4.2) 0/95 (0.0) 39/95 (41.1) |

<0.001 * |

| C-section before or after ICU admission: Before ICU admission After ICU admission |

2/162 (1.2) 2/2 (100) 0/2 (0.0) |

6/112 (5.4) 4/6 (66.7) 2/6 (33.3) |

30/95 (31.6) 20/30 (66.7) 10/30 (33.3) |

0.614 |

Data shown as n (% of total). * Statistically significant differences. a One patient had missing data on the obstetric parameters that were needed for the Robson’s classification. b Difference due to pneumonias relative to the other two groups of patients; there was no statistically significant difference between asymptomatic patients and patients with mild–moderate symptoms (p = 0.228).

3.2.2. Description of C-Sections by Gestational Age at Delivery

Nearly 25% (89/369) of all C-sections (registered in mothers that were infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the third trimester of gestation) took place before the 37th week of gestation; of these, up to 76.4% (68/89) belonged to Robson’s 10th category (singletons pregnancies < 37 weeks with cephalic presentation, with or without previous C-sections).

The C-section rate decreased as gestational age at delivery increased (and vice versa) (Table 4, p < 0.001).

The main reason for C-section in very early preterms (<33 weeks of gestation) was COVID-19 worsening or complication and, as gestational age advanced, these were due to obstetric conditions (Table 4, p < 0.001).

Up to 25% (70/279) of C-sections at term were due to induction failure or programmed C-section in nulliparous women (Robson’s second category) and nearly 20% (51/279) were due to the same reasons but in multiparous women (Robson’s fourth category).

Table 4.

Description of C-sections by gestational age range at delivery in mothers that were infected in the 3rd trimester of gestation (n = 1320).

| Gestational Age Range at Delivery | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 to <33 Weeks | 33 to <37 Weeks | 37 to <41 Weeks | ≥41 Weeks | ||

| Number | n = 39 | n = 112 | n = 986 | n = 183 | |

| Type of delivery: Vaginal + operative vaginal C-section |

12 (30.8) 27 (69.2) |

50 (44.6) 62 (55.4) |

746 (75.7) 240 (24.3) a |

143 (78.1) 40 (21.9) |

<0.001 * |

| Reasons for C-section: COVID-19 complication COVID-19 complication + pre-eclampsia COVID-19 complication + other obstetrical causes Pre-eclampsia without COVID-19 complication Other obstetrical causes without COVID-19 complication |

11/27 (40.7) 4/27 (14.8) 2/27 (7.4) 4/27 (14.8) 6/27 (22.2) |

19/62 (30.6) 4/62 (6.5) 7/62 (11.3) 5/62 (8.1) 27/62 (43.5) |

25/240 (10.4) 3/240 (1.2) 17/240 (7.1) 15/240 (6.2) 180/240 (75.0) |

5/40 (12.5) 0/40 (0.0) 0/40 (0.0) 1/40 (2.5) 34/40 (85.0) |

<0.001 * |

| Robson classification of C-sections: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

0/27 (0.0) 0/27 (0.0) 0/27 (0.0) 0/27 (0.0) 0/27 (0.0) 0/27 (0.0) 1/27 (3.7) 4/27 (14.8) 0/27 (0.0) 22/27 (81.5) |

0/62 (0.0) 0/62 (0.0) 0/62 (0.0) 0/62 (0.0) 0/62 (0.0) 7/62 (11.3) 4/62 (6.5) 5/62 (8.1) 0/62 (0.0) 46/62 (74.2) |

20/239 (8.4) 48/239 (20.1) 26/239 (10.9) 42/239 (17.6) 64/239 (26.8) 19/239 (7.9) 15/239 (6.3) 4/239 (1.7) 1/239 (0.4) 0/239 (0.0) |

5/40 (12.5) 22/40 (55.0) 3/40 (7.5) 9/40 (22.5) 1/40 (2.5) 0/40 (0.0) 0/40 (0.0) 0/40 (0.0) 0/40 (0.0) 0/40 (0.0) |

<0.001 * |

Data shown as n (% of total). * Statistically significant differences. a One patient had missing data on the obstetric parameters that were needed for the Robson’s classification.

3.3. Multivariable Analysis of Risk Factors for Undergoing a C-Section

The multivariable logistic regression modeling results (Table 5) corroborated that the following conditions significantly increased the risk of C-section in SARS-CoV-2-infected mothers: being an IVF pregnancy, being diagnosed with a SARS-CoV-2 infection in the third trimester of gestation, prematurity in mothers with COVID-19 pneumonia (although both conditions, by themselves, were risk factors for a C-section) and developing pre-eclampsia.

Table 5.

Multivariable analysis of the C-section risk.

| Multivariable Model | Variables Associated with C-Section | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-section = COVID-19 symptoms + preterm delivery + interaction (COVID-19 symptoms and preterm delivery) + gestational age at diagnosis + pre-eclampsia + IVF | COVID-19 mild–moderate symptoms | 0.523 a | |

| COVID-19 pneumonia | 0.013 a | 1.55 (1.09–2.18) | |

| Preterm delivery | 0.003 | 2.44 (1.34–4.37) | |

| Interaction (COVID-19 mild–moderate symptoms and preterm delivery) | 0.456 | ||

| Interaction (COVID-19 pneumonia and preterm delivery) | 0.013 | 2.99 (1.27–7.25) | |

| Diagnosis in 2nd trimester | 0.141 b | ||

| Diagnosis in 3rd trimester | 0.029 b | 1.94 (1.10–3.64) | |

| Pre-eclampsia | <0.001 | 2.51 (1.55–4.04) | |

| IVF | <0.001 | 3.38 (2.10–5.44) |

COVID-19 symptoms: 3 categories—asymptomatic, mild-moderate symptoms and pneumonia. Gestational age at diagnosis: 3 categories—1st trimester, 2nd trimester and 3rd trimester. Pre-eclampsia: moderate + severe. IVF: own oocyte + donor oocyte. a Compared to basal category—asymptomatic. b Compared to basal category—1st trimester.

4. Discussion

Our study provides information on the characteristics of SARS-CoV-2-infected mothers according to the type of delivery, the causes and risk factors for C-section and their perinatal results. The main strength of the study was the large cohort of SARS-CoV-2-positive deliveries (1704), the participation of different hospitals (79 centers, public and private) across Spain and the long duration of the study (deliveries that took place from 26 February 2020 to 30 April 2021). In addition, the reasons for C-sections were standardly characterized with Robson’s classification system, taking into consideration the possible differences in clinical practice of the several participating hospitals.

The global incidence of C-sections in our SARS-CoV-2 infected cohort was 26.8%, lower than the one reported by previous studies [7,8]. This difference may be related to the PCR universal screening that was established in the participating hospitals, regardless of the mother’s symptomatology. Moreover, the long period of data collection may have resulted in a better understanding of the disease and, consequently, a decrease in the rate of C-sections. To this day, vertical transmission has not been demonstrated and vaginal delivery was shown to be safe in this COVID-19 scenario [11].

Mothers in the C-section group were older, which could be associated with comorbidities and infertility and, therefore, with a greater need for IVF, as shown by our results. COVID-19 has shown a more aggressive course in patients with previous comorbidities due to its systemic manifestations, such as hypertension, renal disease, thrombocytopenia and liver damage [12,22]. Therefore, the more severe the COVID-19 is, the more likely it is that the pregnancy will end via C-section, especially in women with pneumonia. Furthermore, and prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, IVF and multiple pregnancies had already been described as risk factors for C-section and obstetric morbidity [23,24,25].

In addition, there was a higher proportion of mothers with obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking and multiple gestations in the C-section group. Patients with these characteristics present more obstetric complications [22], which are associated with placental abnormalities and coagulation disorders. These situations could be aggravated by the SARS-CoV-2 infection [26].

Regarding the association that was observed between the moment of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and the type of delivery, the risk of C-section was significantly higher when the infection took place late in pregnancy. This fact could be related to maternal and/or obstetrician’s preferences regarding the uncertainty resulting from a PCR positive result (especially at the beginning of the pandemic) and, of course, with the presence of COVID-19 pneumonia in the third trimester of pregnancy. Furthermore, mothers that were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection during their first trimester delivered with past infection and late in the pandemic and, by then, hospitals already had experience in managing delivery in a COVID-19 scenario.

When it came to perinatal outcomes, the association that was observed between C-section and preterm delivery, as well as with ICU admission (and the need for invasive mechanical ventilation), could be explained by the urgency to terminate the pregnancy due to a worsening of the mother’s condition. If we compare the type of delivery according to COVID-19 symptomatology of the mother, a significant proportion of C-sections occurred in the pneumonia group, which seems to be justified by the respiratory failure of these patients, whereas asymptomatic patients had similar C-section rates to those with mild–moderate COVID-19 symptoms. Moreover, we must always bear in mind that maternal oxygen consumption increases 20% during pregnancy owing to increased metabolic demands and this, combined with reduced functional residual capacity, results in rapid desaturation during respiratory compromise [27], and it is at this moment when intervention is needed. In two-thirds of our patients with pneumonia who underwent a C-section, pregnancy was terminated before ICU admission, and in one-third following. Contrary to what our group reported in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic with a small series of patients [17], it does not seem that C-section was the determining cause of ICU admission but rather that obstetricians decided on this type of delivery just before the patient with pneumonia was admitted to the ICU. Therefore, this type of delivery might be a consequence of the mother’s worsening condition and not a risk factor. It is important to note that many COVID-19 patients in the ICU require decubitus prone positions to improve pulmonary perfusion, where this is especially complicated in pregnant patients.

Previous studies already described the association between SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and iatrogenic prematurity [12,13,17]; this, although inevitable given the maternal deterioration, results in increased neonatal morbidity.

Additionally, patients in the C-section group had more obstetric and medical complications (abruptio placentae, hypertensive disorders and thrombotic events), including two maternal deaths that were associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation. It was established that women with a SARS-CoV-2 infection have a significantly higher risk of developing pre-eclampsia [28]; this results in more C-sections in preterm pregnancies due to the difficulty in inducing these deliveries, which is in line with the findings mentioned above.

Still, a C-section may result in postpartum hemorrhage and postpartum thrombotic events [29,30], as shown in Table 2; therefore, an individual risk–benefit assessment should be made before a C-section is performed.

Regarding the Robson’s classification results, the reasons for the higher rate of C-sections among patients with pneumonia were preterm births (10th category) and at term onset of labor via induction or programmed C-section (4th category). In preterm births, the mother’s worsening condition would explain the urgency to terminate the pregnancy. On the other hand, nearly 45% of C-sections at term, regardless of the parity and the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection, were due to induction failure or programmed C-section. The rate of C-sections in the group of asymptomatic, nulliparous and at term pregnant women (second category) reflected an increase of inductions and programmed C-sections that cannot be explained by the associated morbidities described above. Moreover, the contribution of multiparous women with a previous C-section (fifth category) and COVID-19 mild–moderate symptomatology to this C-section rate was likely related to an aversion to attempting vaginal deliveries. It is necessary to remember that the first Chinese series reported unusually high rates of C-sections and was surely influenced by the initial obstetric strategies during the first wave of the pandemic [31].

Among the limitations of the study is the overrepresentation of symptomatic infections in our cohort because not all participating hospitals had a universal antenatal screening program for SARS-CoV-2 and only identified symptomatic cases via passive surveillance, or implemented this screening program later. On the other hand, the equipment used for the PCR technique differed between hospitals, but all were based on similar extraction and amplification principles. In addition, no serological test was performed on most of our patients to confirm their disease and immune response, either because the tests were not available at the time of recruitment or because of logistical constraints due to the health sector crisis. Lastly, obstetricians’ experience and guidelines followed regarding the delivery care of SARS-CoV-2-infected mothers (and especially regarding C-section use under these circumstances) may vary between centers; however, in the statistical analyses, it was not possible to control for hospitals; the Robson classification of C-sections was applied instead.

In conclusion, C-section risk in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients is associated with the presence of pneumonia, especially in preterm pregnancies, and with clinical conditions that require a rapid and early termination of pregnancy. In pregnancies at term, delivery care is similar between asymptomatic patients and those with mild–moderate COVID-19 symptoms such that the presence of uterine scarring (due to a previous C-section) and induction or programmed C-sections for unspecified obstetric reasons contributed to the C-section rate. Therefore, clinical practice guidelines to improve the quality of pregnancy care in times of COVID-19 are needed, as well as a standardization of the indications for C-sections.

5. Conclusions

After studying the influence of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the type of delivery, we concluded that COVID-19 pneumonia, especially in preterm pregnancies and/or associated with comorbidities, increased the risk of C-section. In contrast, in infected pregnancies at term, the predisposing factors for C-section were the presence of uterine scarring (due to a previous C-section) and induction or programmed C-section for unspecified obstetric reasons.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sara Cruz Melguizo for proofreading the manuscript. Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group (S.O.E.G.): María Belén Garrido Luque (Hospital Axarquia), Camino Fernández Fernández (Complejo Asistencial de León), Ana Villalba Yarza (Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca), Esther María Canedo Carballeira (Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña), María Begoña Dueñas Carazo (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela), Rosario Redondo Aguilar (Complejo Hospitalario Jaén), María Victoria Rodríguez Gallego (Complejo Hospitalario San Millán—San Pedro de la Rioja), Esther Álvarez Silvares (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense), María Isabel Pardo Pumar (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra), Macarena Alférez Álvarez-Mallo (HM Hospitales), Víctor Muñoz Carmona (Hospital Alto Guadalquivir, Andújar), Noelia Pérez Pérez (Hospital Clínico San Carlos), Cristina Álvarez Colomo (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid), Onofre Alomar Mateu (Hospital Comarcal d’Inca), Claudio Marañon Di Leo (Hospital Costa del Sol), María del Carmen Parada Millán (Hospital da Barbanza), Adrián Martín García (Hospital de Burgos), José Navarrina Martínez (Hospital de Donostia), Anna Mundó Fornell (Hospital Universitario Santa Creu i Sant Pau), Elena Pascual Salvador (Hospital de Minas de Riotinto), Tania Manrique Gómez (Hospital de Montilla y Quirón Salud Córdoba), Marta Ruth Meca Casbas (Hospital de Poniente), Noemí Freixas Grimalt (Hospital Universitari Son Llàtzer), Adriana Aquise and María del Mar Gil (Hospital de Torrejón), Eduardo Cazorla Amorós (Hospital de Torrevieja), Alberto Armijo Sánchez (Hospital de Valme), María Isabel Conca Rodero (Hospital de Vinalopó), Ana Belén Oreja Cuesta (Hospital del Tajo), Cristina Ruiz Aguilar (Hospital Doctor Peset, Valencia), Susana Fernández García (Hospital General de L’Hospitalet), Mercedes Ramírez Gómez (Hospital General La Mancha Centro), Esther Vanessa Aguilar Galán (Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real), Rocío López Pérez (Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía de Cartagena), Carmen Baena Luque (Hospital Infanta Margarita de Cabra), Luz María Jiménez Losa (Hospital Infanta Sofía), Susana Soldevilla Pérez (Hospital Jerez de la Frontera), María Reyes Granell Escobar (Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez), Manuel Domínguez González (Hospital La Línea), Flora Navarro Blaya (Hospital Universitario Rafael Méndez), Juan Carlos Wizner de Alva (Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara), Rosa Pedró Carulla (Hospital Sant Joan de Reus), Encarnación Carmona Sánchez (Hospital Santa Ana, Motril), Judit Canet Rodríguez (Hospital Santa Caterina de Salt), Montse Macià (Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova), Laia Pratcorona (Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol), Irene Gastaca Abásolo (Hospital Universitario Araba), Begoña Martínez Borde (Hospital Universitario de Bilbao), Óscar Vaquerizo Ruiz (Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes), José Ruiz Aragón (Hospital Universitario de Ceuta), Raquel González Seoane (Hospital Universitario de Ferrol), María Teulón González (Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada), Lourdes Martín González (Hospital Joan XXIII de Tarragona), Cristina Lesmes Heredia (Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí de Sabadell), María Joaquina Gimeno Gimeno (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía), Rut Bernardo (Hospital Universitario Río Hortega), Otilia González Vanegas (Hospital Universitario San Cecilio, Instituto de Investigación Biosanitaria, Granada), Ana María Fernández Alonso (Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas), Lucía Díaz Meca (Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia), Alberto Puerta Prieto (Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Instituto de Investigación Biosanitaria, Granada), Carmen María Orizales Lago (Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa, Leganés), Mónica Catalina Coello (Hospital Virgen Concha de Zamora), María José Núñez Valera (Hospital Virgen de la Luz), Lucas Cerrillos González (Hospital Virgen del Rocío), José Adanez García (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias), Elena Ferriols-Pérez (Hospital del Mar), Marta Roqueta (Hospital Universitario Josep Trueta), Sara Cruz Melguizo (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro), Marta García Sánchez (Hospital Universitario Quirónsalud de Málaga), Emilio Couceiro Naveira (Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro de Vigo), Mar Muñoz Chapuli (Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón), Elena Pintado Paredes (Hospital Universitario de Getafe), Inmaculada Mejía Jiménez (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre) and Alejandra Abascal Saiz (Hospital La Paz).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/v13112330/s1, Table S1: List of hospital members of the Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group that were included in this study (n = 79), Table S2: STROBE Statement—Checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ó.M.-P.; methodology, M.L.d.l.C.C. and Ó.M.-P.; software, M.L.d.l.C.C.; validation, E.M.A., J.R.B.M., M.L.d.l.C.C., M.B.E.P., M.d.P.G.M., J.A.S.B., L.F.A., P.P.R., A.Á.B., J.P.M.C. and Ó.M.-P.; formal analysis, M.L.d.l.C.C.; investigation, E.M.A., J.R.B.M., M.L.d.l.C.C., M.B.E.P., M.d.P.G.M., J.A.S.B., L.F.A., P.P.R., A.Á.B., J.P.M.C., Ó.M.-P. and Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group; resources, Ó.M.-P.; data curation, M.L.d.l.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.A., M.L.d.l.C.C. and Ó.M.-P.; writing—review and editing, E.M.A., J.R.B.M., M.L.d.l.C.C., M.B.E.P., M.d.P.G.M., J.A.S.B., L.F.A., P.P.R., A.Á.B., J.P.M.C. and Ó.M.-P.; visualization, E.M.A., J.R.B.M., M.L.d.l.C.C., M.B.E.P., M.d.P.G.M., J.A.S.B., L.F.A., P.P.R., A.Á.B., J.P.M.C., Ó.M.-P. and Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group; supervision, Ó.M.-P.; project administration, Ó.M.-P.; funding acquisition, Ó.M.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by public funds that were obtained in competitive calls: Grant COV20/00021 (EUR 43,000 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III—Spanish Ministry of Health) and co-financed with Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Puerta de Hierro University Hospital (PE 55/20; 23 March 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects that were involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the multicenter nature of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Events as They Happen. [(accessed on 25 May 2021)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen.

- 2.Ellington S., Strid P., Tong V.T., Woodworth K., Galang R.R., Zambrano L.D., Nahabedian J., Anderson K., Gilboa S.M. Characteristics of Women of Reproductive Age with Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status—United States, January 22–June 7, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69:769–775. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6925a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gheblawi M., Wang K., Viveiros A., Nguyen Q., Zhong J.C., Turner A.J., Raizada M.K., Grant M.B., Oudit G.Y. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 Receptor and Regulator of the Renin-Angiotensin System: Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Discovery of ACE2. Circ. Res. 2020;126:1456–1474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight M., Bunch K., Vousden N., Morris E., Simpson N., Gale C., O’Brien P., Quigley M., Brocklehurst P., Kurinczuk J.J., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK: National population based cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m2107. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong L., Tian J., He S., Zhu C., Wang J., Liu C., Yang J. Possible Vertical Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 From an Infected Mother to Her Newborn. JAMA. 2020;323:1846–1848. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee D.H., Lee J., Kim E., Woo K., Park H.Y., An J. Emergency cesarean section performed in a patient with confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus-2—A case report- Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2020;73:347–351. doi: 10.4097/kja.20116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hantoushzadeh S., Shamshirsaz A.A., Aleyasin A., Seferovic M.D., Aski S.K., Arian S.E., Pooransari P., Ghotbizadeh F., Aalipour S., Soleimani Z., et al. Maternal death due to COVID-19. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;223:109.e1–109.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrazzi E., Frigerio L., Savasi V., Vergani P., Prefumo F., Barresi S., Bianchi S., Ciriello E., Facchinetti F., Gervasi M.T., et al. Vaginal delivery in SARS-CoV-2-infected pregnant women in Northern Italy: A retrospective analysis. BJOG. 2020;127:1116–1121. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parazzini F., Bortolus R., Mauri P.A., Favilli A., Gerli S., Ferrazzi E. Delivery in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2: A fast review. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020;150:41–46. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Protocols Medicina Maternofetal Hospital Clìnic-Hospital Sant Joan de Dèu-Universitat de Barcelona. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)]. Available online: https://medicinafetalbarcelona.org/protocolos/es/obstetricia/cesarea.html.

- 11.Rottenstreich A., Tsur A., Braverman N., Kabiri D., Porat S., Benenson S., Oster Y., Kam H.A., Walfisch A., Bart Y., et al. Vaginal delivery in SARS-CoV-2-infected pregnant women in Israel: A multicenter prospective analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020;303:1401–1405. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05854-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrasco I., Muñoz-Chapuli M., Vigil-Vázquez S., Aguilera-Alonso D., Hernández C., Sánchez-Sánchez C., Oliver C., Riaza M., Pareja M., Sanz O., et al. SARS-COV-2 infection in pregnant women and newborns in a Spanish cohort (GESNEO-COVID) during the first wave. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:326. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03784-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melguizo S.C., Conty M.D.L.C., Payán P.C., Abascal-Saiz A., Recarte P.P., Rodríguez L.G., Marín C.C., Varea A.M., Cuesta A.O., Rodríguez P., et al. Pregnancy Outcomes and SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group Study. Viruses. 2021;13:853. doi: 10.3390/v13050853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegler Y., Weiner Z., Solt I. Prelabor Rupture of Membranes: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 217. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;135:e80–e97. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO OMS|La Clasificación de Robson: Manual de Aplicación. 2018. [(accessed on 21 April 2021)]. Available online: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/robson-classification/es/

- 16.O’Leary B.D., Kane D.T., Aretz N.K., Geary M.P., Malone F.D., Hehir M.P. Use of the Robson Ten Group Classification System to categorise operative vaginal delivery. Aust. New Zealand J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;60:858–864. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez-Perez O., Vouga M., Cruz Melguizo S., Forcen Acebal L., Panchaud A., Muñoz-Chápuli M., Baud D. Association between Mode of Delivery among Pregnant Women with COVID-19 and Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes in Spain. JAMA. 2020;324:296–299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gotzschef P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. ARTÍCULO ESPECIAL Declaración de la Iniciativa STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology): Directrices Para la Comunicación de Estudios Observacionales (The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology [STROBE] statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies) [(accessed on 21 April 2021)]. Available online: http://www.epidem.com/

- 19.Brown M.A., Magee L.A., Kenny L.C., Karumanchi S.A., McCarthy F., Saito S., Hall D.R., Warren C.E., Adoyi G., Ishaku S. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Hypertension. 2018;72:24–43. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomson A.J. Care of Women Presenting with Suspected Preterm Prelabour Rupture of Membranes from 24+0 Weeks of Gestation: Green-top Guideline No. 73. BJOG. 2019;126:e152–e166. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015;67:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allotey J., Stallings E., Bonet M., Yap M., Chatterjee S., Kew T., Debenham L., Llavall A.C., Dixit A., Zhou D., et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: Living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaigham M., Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: A systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020;99:823–829. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woo I., Hindoyan R., Landay M., Ho J., Ingles S.A., McGinnis L.K., Paulson R.J., Chung K. Perinatal outcomes after natural conception versus in vitro fertilization (IVF) in gestational surrogates: A model to evaluate IVF treatment versus maternal effects. Fertil. Steril. 2017;108:993–998. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santana D.S., Surita F.G., Cecatti J.G. Multiple Pregnancy: Epidemiology and Association with Maternal and Perinatal Morbidity. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2018;40:554–562. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1668117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han H., Yang L., Liu R., Liu F., Wu K.L., Li J., Liu X.H., Zhu C.L. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2020;58:1116–1120. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wise R.A., Polito A.J., Krishnan V. Respiratory physiologic changes in pregnancy. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 2006;26:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conde-Agudelo A., Romero R. SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deneux-Tharaux C., Carmona E., Bouvier-Colle M.H., Bréart G. Postpartum maternal mortality and cesarean delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;108:541–548. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000233154.62729.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esteves-Pereira A.P., Deneux-Tharaux C., Nakamura-Pereira M., Saucedo M., Bouvier-Colle M.H., do Carmo Leal M. Caesarean delivery and postpartum maternal mortality: A population-based case control study in Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0153396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu N., Li W., Kang Q., Xiong Z., Wang S., Lin X., Liu Y., Xiao J., Liu H., Deng D., et al. Clinical Features and obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnancy patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. A restrospective, single-centre, desctriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:559–564. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30176-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the multicenter nature of the study.