Abstract

Simple Summary

Bedbugs (Cimex spp.) are a nuisance pest of significant public health importance that is on the rise globally, especially in crowded cities such as Hong Kong. Bedbug infestations disproportionately affect underprivileged communities living in crowded and dilapidated housing. This study uses an online survey to investigate the health impacts of bedbug infestations among bedbug victims. This study found that most bedbug victims experienced ≥five bites in the past month, usually on the arms and legs. The most common reaction to bites were itchiness, redness, and swelling of the skin, and difficulties sleeping or restlessness. Bites usually occurred during sleep, impacting the bedbug victim’s mental and emotional health, and sleeping quality most severely. The adverse health outcomes of bedbug infestations were associated with the lower self-rated health and average hours of sleep per day of bedbug victims. This study brings attention to the neglected issue of bedbug infestations by providing evidence on the scope of its health impacts, informing public health interventions including public education and extermination programmes, and supportive laws and policies for adequate housing and hygiene. The successful control of bedbugs in an international city such as Hong Kong can inform the control of the global bedbug resurgence.

Abstract

Bedbugs (Cimex spp.) are a nuisance public-health pest that is on the rise globally, particularly in crowded cities such as Hong Kong. To investigate the health impacts of bedbug infestations among bedbug victims, online surveys were distributed in Hong Kong between June 2019 to July 2020. Data on sociodemographics, self-rated health, average hours of sleep per day, and details of bedbug infestation were collected. Bivariate and multivariable analysis were performed using logistic regression. The survey identified 422 bedbug victims; among them, 223 (52.9%) experienced ≥five bites in the past month; most bites occurred on the arms (n = 202, 47.8%) and legs (n = 215, 51%), and the most common reaction to bites were itchiness (n = 322, 76.3%), redness, and swelling of the skin (n = 246, 58.1%), and difficulties sleeping or restlessness (n = 125, 29.6%). Bites usually occurred during sleep (n = 230, 54.5%). For impact on daily life in the past month, most bedbug victims reported moderate to severe impact on mental and emotional health (n = 223, 52.8%) and sleeping quality (n = 239, 56.6%). Lower self-rated health (aOR < 1) was independently associated with impact on physical appearance (p = 0.008), spending money on medication or doctor consultation (p = 0.04), number of bites in the past month (p = 0.023), and irregular time of bites (p = 0.003). Lower average hours of sleep per day (aOR < 1) was independently associated with impact on mental and emotional health (p = 0.016). This study brings attention to the neglected issue of bedbug infestation by considering bedbugs as an infectious agent instead of a vector and providing empirical evidence describing its health impacts.

Keywords: bed bugs, Cimex spp., Hong Kong, sleep disturbance, health impact, public health, causal agent, infectious agent, vector

1. Introduction

Bedbugs (Cimex spp.) are hematophagous ectoparasites that pose a significant threat to public health [1]. The burden from bedbug infestations is expected to worsen due to the global bedbug resurgence which has been attributed to several factors including human population growth, increase in international travel and trade, and urbanisation [2,3,4].

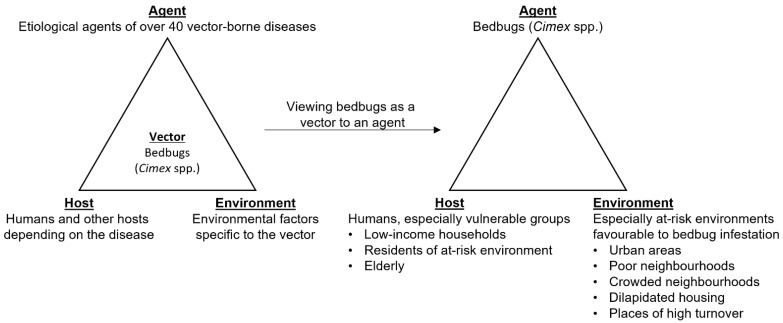

Although bedbugs have the potential to transmit etiological agents of over 40 vector-borne diseases, no reported outbreaks have been attributed to them [4,5,6,7]. However, the impact of bedbug infestation cannot only be measured by its potential for transmitting vector-borne diseases but as an agent itself (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Shifting the view from bedbugs as a vector to an agent.

Previous studies have linked bedbug infestations to adverse health outcomes, including cimicosis—itchy sores that result from bedbug bites—and insomnia, and the economic burden of their extermination which may include hiring exterminators, purchasing insecticides, or replacing infested furniture [1,8,9,10]. A previous cross-sectional study found that the health impact and financial burden of bedbugs is prevalent among its victims where over 70% had experienced health, psychological, social life, and financial impact [11].

Several mental health conditions were associated with bedbug infestations which included general psychological symptoms such as distress or anxiety, and diagnosable psychiatric disorders including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), phobia, and depression [12,13,14]. The financial burden of bedbug infestations can contribute to the development or worsening of these mental health conditions [12].

The health impact of bedbug infestations disproportionately affects low-income households due to environmental and socioeconomic vulnerabilities, such as living in crowded housing, having low income, or low education level [10,15,16,17,18].

Pest-control companies in Hong Kong have reported increased cases of bedbug infestations in recent years [19]. Existing volunteer bedbug extermination services in Hong Kong are limited by human and material resources [20]. The crowded and dilapidated features of many housing buildings in Hong Kong facilitate the spread of bedbug infestations [21]. Bedbug victims, particularly those living in subdivided units, may sleep in 24 h restaurants to escape bedbug bites, contributing to the ‘Mc-Refugee’ phenomena [22,23]. Nevertheless, bedbug infestations have been a neglected issue in Hong Kong [19,23].

There are a lack of data on the patterns of bedbug bites (e.g., location, time, physical reaction) and the health impact they have on bedbug victims in Hong Kong. To bring attention to the neglected bedbug issue and inform public health laws, policies, and initiatives on alleviating bedbug infestation, this study aims to describe the patterns of bedbug bites and their effect on self-rated health and average hours of sleep per day.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Sampling

This study was part of a larger project entitled ‘Providing low-income residents with safe, effective, affordable and sustainable solutions in tackling bed bug problems’ conducted by the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) Anti-Bedbug Research Action Group. Details of the data collection and sampling methods were reported previously [21]. In brief, this was a cross-sectional study conducted from June 2019 to July 2020 in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. Online self-reported questionnaires in Chinese were distributed via an electronic link on social media platforms. The back translated English version of the questionnaire used is provided as a Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table S1). The questionnaire collected data on the participants’ sociodemographic, self-rated health, average hours of sleep per day, and history of bedbug infestation including its severity, impact on daily life, and details of bedbug bites. Participants were eligible to participate if they lived in Hong Kong and were aged 18 or above. Participants were recruited by volunteer sampling. After accessing the link to the online survey, participants were shown a consent form which explained the details of the study. Participants provided their informed consent to participate in digital form. A total of 696 participants completed the survey.

2.2. Measures

All data were collected as categorical variables. All participants were asked to rate their health status on a 10-point Likert scale with a higher score representing better health, report their average hours of sleep per day in the past month, and how often participants saw bedbugs in their place of residence in the past year with responses ranging from ‘never’ to ‘very often’ on a five-point Likert scale. If participants had seen bedbugs in their place of residence in the past year (i.e., not ‘never’), data would be collected on the severity of the bedbug infestation in the past year, severity of impact on daily life in the past month with regards to some aspects of health including physical health, and mental and emotional health, frequency of bedbug bites, location of bites, reaction to bites, and when the bites occurred. For sociodemographic data, participants’ sex, age, education level, and monthly household income in HKD were collected.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS 26. To improve the representativeness of the sample, cases were weighted by age and sex using end-of-2019 census data [24].

Self-rated health and average hours of sleep per day were the dependent variables. Self-rated health was dichotomised into low (≤5) and high (>5) since those who rated ≤5 accounted for about 25% of the weighted sample. Average hours of sleep per day were dichotomised into low (<7 h) and high (≥7 h) since a previous study found that nearly 50% of the Hong Kong population had <7 h of sleep per day [25].

Variables related to bedbug infestation and sociodemographics were the independent variables. Bivariate logistic regression using a chi-square test for categorical variables was used to identify the variables for bedbug infestation associated with dichotomised self-rated health and average hours of sleep per day. Variables related to bedbug infestation were considered for inclusion in multivariable logistic regression if p-values were less than or equal to 0.05 in the bivariate analysis; sociodemographic variables were included regardless of their statistical significance.

Multivariable logistic regression was performed to investigate the effect of variables for bedbug infestation on self-rated health and average hours of sleep per day. The unadjusted model was fitted using backward conditional method where covariates related to bedbug infestation were removed stepwise starting from the covariate with the largest p-value until all covariates had p < 0.05; this model was adjusted by entering the sociodemographic variables (sex, age, education level, monthly household income) regardless of their significance.

The pseudo-R2 values for the multivariable regression models were calculated using Nagelkerke’s approach [26]. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was performed on the models, where the goodness-of-fit assumption was not violated if p > 0.05. Multicollinearity diagnostics were also performed on the models, where multicollinearity was considered to be present if the covariates had an absolute value of Pearson correlation coefficient |r| ≥ 0.7 or variance inflation factors (VIF) ≥ 10 [27].

Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± SD or frequencies and percentages. For bivariate logistic regression, effect estimates were presented as odds ratio (OR). For multivariable logistic regression, unadjusted and adjusted OR were presented instead (uOR and aOR). All ORs were presented with their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical significance was considered when the two-sided p-value was < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patterns of Bedbug Bites

The questionnaire received 696 responses; 663 (95.3%) participants remained after listwise deletion of participants with missing age or sex data. Table 1 shows the weighted responses from the survey, where 422 (63.7%) of the participants had had bedbug infestation in the past year. Among them, 227 (53.7%) had been severely to extremely severely troubled by bedbugs in the past year. For impact on daily life in the past month, over 50% reported moderate to severe impact on mental and emotional health (n = 223, 52.8%) and sleeping quality (n = 239, 56.6%).

Table 1.

Survey responses.

| Variable (n) | Weighted Freq. (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Self-rated health (663) | 6.66 ± 1.85 |

| Average hours of sleep per day (663) | |

| <5 | 132 (19.9%) |

| 5–6 | 270 (40.8%) |

| 7–9 | 225 (33.9%) |

| >9 | 36 (5.5%) |

| Bedbug infestation (663) | |

| Never | 241 (36.3%) |

| Rarely | 137 (20.6%) |

| Sometimes | 92 (13.9%) |

| Often | 93 (14.1%) |

| Very often | 100 (15.1%) |

| Severity of being troubled by bedbugs in the past year (422) | |

| Not severe at all | 19 (4.5%) |

| Mildly severe | 55 (13.1%) |

| Moderately severe | 121 (28.7%) |

| Severe | 124 (29.4%) |

| Extremely severe | 103 (24.3%) |

| Impact on daily life in the past month | |

| Physical health (422) | |

| No impact | 143 (33.8%) |

| Slight | 114 (27.0%) |

| Moderate | 109 (25.8%) |

| Severe | 57 (13.5%) |

| Mental and emotional health (422) | |

| No impact | 117 (27.6%) |

| Slight | 83 (19.6%) |

| Moderate | 114 (27.0%) |

| Severe | 109 (25.8%) |

| Sleeping quality (422) | |

| No impact | 111 (26.2%) |

| Slight | 73 (17.2%) |

| Moderate | 110 (26.1%) |

| Severe | 128 (30.4%) |

| Physical appearance (422) | |

| No impact | 167 (39.5%) |

| Slight | 106 (25.0%) |

| Moderate | 99 (23.4%) |

| Severe | 51 (12.1%) |

| Work and academic performance (422) | |

| No impact | 196 (46.5%) |

| Slight | 107 (25.4%) |

| Moderate | 78 (18.5%) |

| Severe | 40 (9.6%) |

| Social activities (422) | |

| No impact | 206 (48.7%) |

| Slight | 111 (26.4%) |

| Moderate | 74 (17.5%) |

| Severe | 31 (7.4%) |

| Avoidance to go home (422) | |

| No impact | 180 (42.5%) |

| Slight | 88 (20.9%) |

| Moderate | 81 (19.3%) |

| Severe | 73 (17.3%) |

| Spending money on medication or doctor consultation (422) | |

| No impact | 169 (40.0%) |

| Slight | 95 (22.5%) |

| Moderate | 100 (23.6%) |

| Severe | 59 (14.0%) |

| No. bites in past month (422) | |

| 0 | 96 (22.7%) |

| 1–4 | 103 (24.4%) |

| 5–10 | 85 (20.2%) |

| >10 | 138 (32.7%) |

| Location of bites (422) | |

| Legs | 215 (51.0%) |

| Arms | 202 (47.8%) |

| Whole body | 132 (31.3%) |

| Head and neck | 82 (19.5%) |

| Chest and back | 67 (16.0%) |

| Belly | 49 (11.5%) |

| Physical reaction to bites (422) | |

| Itchiness | 322 (76.3%) |

| Redness and swelling of the skin | 246 (58.1%) |

| Difficulties sleeping or restlessness | 125 (29.6%) |

| Pain at the site of bite | 82 (19.4%) |

| Bleeding at the site of bite | 36 (8.5%) |

| Headache | 15 (3.5%) |

| Difficulties breathing | 3 (0.8%) |

| Fever | 1 (0.3%) |

| Blisters | 1 (0.3%) |

| Time of bites (422) | |

| During sleep | 230 (54.5%) |

| Irregularly | 160 (37.9%) |

| Night (before sleeping) | 103 (24.4%) |

| Watching TV or otherwise being still | 76 (18.1%) |

| Daytime | 42 (9.9%) |

| Holding clothes or umbrellas | 13 (3.0%) |

| Sex (663) | |

| Female | 360 (54.4%) |

| Male | 303 (45.6%) |

| Age (663) | |

| 0–24 | 138 (20.8%) |

| 25–44 | 196 (29.6%) |

| 45–64 | 210 (31.7%) |

| ≥65 | 119 (18.0%) |

| Education level (663) | |

| Primary education or below | 68 (10.3%) |

| Secondary education | 218 (32.8%) |

| Tertiary education | 377 (56.9%) |

| Monthly household income (663) | |

| <HKD 10,000 | 99 (14.9%) |

| HKD 10,000–30,000 | 254 (38.3%) |

| HKD 30,001–50,000 | 156 (23.5%) |

| HKD 50,001–80,000 | 99 (15.0%) |

| >HKD 80,000 | 55 (8.4%) |

Among participants who had had bedbug infestation, 223 (52.9%) experienced ≥five bites in the past month. Around 50% of all bites occurred on the arms (n = 202, 47.8%) and legs (n = 215, 51%), and the most common reactions to bites were itchiness (n = 322, 76.3%), redness and swelling of the skin (n = 246, 58.1%), and difficulties sleeping or restlessness (n = 125, 29.6%). Over 50% of the bites occurred during sleep (n = 230, 54.5%).

3.2. Self-Rated Health and Bedbug Infestation

Table 2 shows the results of the bivariate analysis. Increased bedbug infestation and severity of being troubled by bedbugs in the past year were associated with lower self-rated health (p < 0.001). Greater impact on daily life in the past month for all reported aspects including physical health, mental and emotional health, sleeping quality, physical appearance, work and academic performance, social activities, avoidance to go home, and spending money on medication or doctor consultation were associated with lower self-rated health (p < 0.001). An increased number of bedbug bites in the past month was associated with lower self-rated health (p < 0.001). Bites to the legs, arms, whole body, and head and neck were associated with lower self-rated health (p < 0.01). Bite reactions that were associated with lower self-rated health were itchiness, redness and swelling of the skin, difficulties sleeping or restlessness, pain at the site of bite, and bleeding at the site of bite (p < 0.001). The times of bites that were associated with lower self-rated health were during sleep, irregularly, and watching TV or otherwise being still (p < 0.001). Younger age, higher education level, and higher monthly household income were associated with higher self-rated health (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of survey responses by self-rated health and average hours of sleep per day.

| Variables | Self-Rated Health (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value * | Average Hours of Sleep per Day (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low ≤ 5 | High > 5 | Low < 7 | High ≥ 7 | |||||

| Bedbug infestation | ||||||||

| Never (ref.) | 34 (14.1) | 207 (85.9) | <0.001 | 115 (47.7) | 126 (52.3) | <0.001 | ||

| Rarely | 19 (13.9) | 118 (86.1) | 1.01 (0.55–1.85) | 0.975 | 78 (56.9) | 59 (43.1) | 0.69 (0.45–1.05) | 0.086 |

| Sometimes | 17 (18.3) | 76 (81.7) | 0.73 (0.39–1.40) | 0.345 | 57 (61.3) | 36 (38.7) | 0.57 (0.35–0.94) | 0.026 |

| Often | 34 (36.6) | 59 (63.4) | 0.29 (0.16–0.50) | <0.001 | 75 (80.6) | 18 (19.4) | 0.23 (0.13–0.40) | <0.001 |

| Very often | 55 (55.0) | 45 (45.0) | 0.13 (0.08–0.23) | <0.001 | 77 (77.0) | 23 (23.0) | 0.27 (0.16–0.46) | <0.001 |

| Severity of being troubled by bedbugs in the past year | ||||||||

| Not severe at all (ref.) | 3 (15.0) | 17 (85.0) | <0.001 | 8 (42.1) | 11 (57.9) | 0.003 | ||

| Mildly severe | 4 (7.3) | 51 (92.7) | 1.78 (0.35–9.19) | 0.490 | 38 (69.1) | 17 (30.9) | 0.36 (0.12–1.04) | 0.058 |

| Moderately severe | 19 (15.7) | 102 (84.3) | 0.82 (0.20–3.33) | 0.776 | 70 (57.9) | 51 (42.1) | 0.56 (0.21–1.49) | 0.245 |

| Severe | 43 (34.7) | 81 (65.3) | 0.29 (0.07–1.13) | 0.075 | 91 (73.4) | 33 (26.6) | 0.28 (0.11–0.76) | 0.012 |

| Extremely severe | 55 (53.4) | 48 (46.6) | 0.13 (0.03–0.53) | 0.004 | 80 (77.7) | 23 (22.3) | 0.22 (0.08–0.61) | 0.003 |

| Impact on daily life in the past month | ||||||||

| Physical health | ||||||||

| No impact (ref.) | 18 (12.6) | 125 (87.4) | <0.001 | 83 (58.5) | 59 (41.5) | <0.001 | ||

| Slight | 26 (22.8) | 88 (77.2) | 0.49 (0.26–0.96) | 0.037 | 72 (63.2) | 42 (36.8) | 0.82 (0.50–1.36) | 0.449 |

| Moderate | 46 (42.2) | 63 (57.8) | 0.20 (0.10–0.36) | <0.001 | 84 (77.1) | 25 (22.9) | 0.41 (0.24–0.72) | 0.002 |

| Severe | 34 (59.6) | 23 (40.4) | 0.09 (0.05–0.20) | <0.001 | 47 (82.5) | 10 (17.5) | 0.28 (0.13–0.61) | 0.001 |

| Mental and emotional health | ||||||||

| No impact (ref.) | 13 (11.2) | 103 (88.8) | <0.001 | 62 (53.4) | 54 (46.6) | <0.001 | ||

| Slight | 18 (21.7) | 65 (78.3) | 0.48 (0.22–1.04) | 0.062 | 49 (59.0) | 34 (41.0) | 0.81 (0.46–1.43) | 0.461 |

| Moderate | 40 (35.1) | 74 (64.9) | 0.24 (0.12–0.47) | <0.001 | 82 (71.9) | 32 (28.1) | 0.44 (0.26–0.77) | 0.004 |

| Severe | 53 (48.6) | 56 (51.4) | 0.13 (0.07–0.27) | <0.001 | 94 (86.2) | 15 (13.8) | 0.18 (0.10–0.35) | <0.001 |

| Sleeping quality | ||||||||

| No impact (ref.) | 16 (14.5) | 94 (85.5) | <0.001 | 67 (60.4) | 44 (39.6) | <0.001 | ||

| Slight | 10 (13.7) | 63 (86.3) | 1.10 (0.47–2.58) | 0.823 | 38 (52.1) | 35 (47.9) | 1.42 (0.78–2.58) | 0.251 |

| Moderate | 38 (34.5) | 72 (65.5) | 0.33 (0.17–0.63) | <0.001 | 76 (68.5) | 35 (31.5) | 0.7 (0.40–1.21) | 0.200 |

| Severe | 59 (46.1) | 69 (53.9) | 0.20 (0.11–0.38) | <0.001 | 107 (82.9) | 22 (17.1) | 0.31 (0.17–0.56) | <0.001 |

| Physical appearance | ||||||||

| No impact (ref.) | 21 (12.6) | 146 (87.4) | <0.001 | 96 (57.5) | 71 (42.5) | <0.001 | ||

| Slight | 32 (30.2) | 74 (69.8) | 0.33 (0.18–0.62) | <0.001 | 69 (65.7) | 36 (34.3) | 0.71 (0.43–1.18) | 0.184 |

| Moderate | 40 (40.4) | 59 (59.6) | 0.21 (0.12–0.39) | <0.001 | 75 (75.8) | 24 (24.2) | 0.44 (0.25–0.76) | 0.003 |

| Severe | 32 (62.7) | 19 (37.3) | 0.09 (0.04–0.18) | <0.001 | 47 (92.2) | 4 (7.8) | 0.11 (0.04–0.32) | <0.001 |

| Work and academic performance | ||||||||

| No impact (ref.) | 40 (20.4) | 156 (79.6) | <0.001 | 119 (60.4) | 78 (39.6) | 0.004 | ||

| Slight | 31 (28.7) | 77 (71.3) | 0.65 (0.38–1.12) | 0.118 | 76 (70.4) | 32 (29.6) | 0.64 (0.39–1.06) | 0.082 |

| Moderate | 30 (38.5) | 48 (61.5) | 0.41 (0.23–0.72) | 0.002 | 55 (70.5) | 23 (29.5) | 0.63 (0.36–1.1) | 0.105 |

| Severe | 23 (56.1) | 18 (43.9) | 0.20 (0.10–0.41) | <0.001 | 37 (90.2) | 4 (9.8) | 0.15 (0.05–0.46) | <0.001 |

| Social activities | ||||||||

| No impact (ref.) | 34 (16.5) | 172 (83.5) | <0.001 | 123 (59.7) | 83 (40.3) | 0.002 | ||

| Slight | 35 (31.3) | 77 (68.8) | 0.43 (0.25–0.75) | 0.003 | 79 (71.2) | 32 (28.8) | 0.6 (0.37–0.99) | 0.047 |

| Moderate | 34 (45.9) | 40 (54.1) | 0.23 (0.13–0.42) | <0.001 | 56 (75.7) | 18 (24.3) | 0.49 (0.27–0.89) | 0.019 |

| Severe | 22 (71.0) | 9 (29.0) | 0.08 (0.03–0.19) | <0.001 | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | 0.12 (0.03–0.47) | 0.002 |

| Avoidance to go home | ||||||||

| No impact (ref.) | 25 (14.0) | 154 (86.0) | <0.001 | 101 (56.4) | 78 (43.6) | <0.001 | ||

| Slight | 22 (24.7) | 67 (75.3) | 0.51 (0.27–0.96) | 0.038 | 64 (72.7) | 24 (27.3) | 0.49 (0.28–0.85) | 0.011 |

| Moderate | 36 (44.4) | 45 (55.6) | 0.20 (0.11–0.38) | <0.001 | 62 (76.5) | 19 (23.5) | 0.4 (0.22–0.72) | 0.002 |

| Severe | 41 (56.2) | 32 (43.8) | 0.13 (0.07–0.24) | <0.001 | 59 (80.8) | 14 (19.2) | 0.3 (0.16–0.58) | <0.001 |

| Spending money medication or doctor consultation | ||||||||

| No impact (ref.) | 30 (17.8) | 139 (82.2) | <0.001 | 100 (59.2) | 69 (40.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Slight | 23 (24.2) | 72 (75.8) | 0.67 (0.36–1.24) | 0.205 | 61 (64.2) | 34 (35.8) | 0.81 (0.48–1.37) | 0.432 |

| Moderate | 33 (33.0) | 67 (67.0) | 0.44 (0.25–0.78) | 0.005 | 71 (71.7) | 28 (28.3) | 0.58 (0.34–0.99) | 0.047 |

| Severe | 38 (64.4) | 21 (35.6) | 0.11 (0.06–0.22) | <0.001 | 55 (93.2) | 4 (6.8) | 0.12 (0.04–0.33) | <0.001 |

| No. bites in past month | ||||||||

| 0 (ref.) | 11 (11.5) | 85 (88.5) | <0.001 | 61 (63.5) | 35 (36.5) | 0.015 | ||

| 1–4 | 22 (21.4) | 81 (78.6) | 0.48 (0.22–1.06) | 0.069 | 61 (58.7) | 43 (41.3) | 1.23 (0.70–2.19) | 0.471 |

| 5–10 | 18 (21.2) | 67 (78.8) | 0.49 (0.22–1.11) | 0.089 | 58 (68.2) | 27 (31.8) | 0.81 (0.44–1.51) | 0.515 |

| >10 | 74 (53.6) | 64 (46.4) | 0.11 (0.05–0.23) | <0.001 | 107 (77.5) | 31 (22.5) | 0.51 (0.29–0.91) | 0.022 |

| Location of bites (no = ref.) | ||||||||

| Legs | 81 (37.7) | 134 (62.3) | 0.44 (0.28–0.67) | <0.001 | 151 (70.2) | 64 (29.8) | 0.8 (0.53–1.21) | 0.291 |

| Arms | 74 (36.6) | 128 (63.4) | 0.50 (0.33–0.77) | 0.002 | 144 (71.3) | 58 (28.7) | 0.74 (0.49–1.12) | 0.157 |

| Whole body | 54 (40.6) | 79 (59.4) | 0.47 (0.31–0.74) | <0.001 | 102 (77.3) | 30 (22.7) | 0.53 (0.33–0.84) | 0.008 |

| Head and neck | 38 (45.8) | 45 (54.2) | 0.40 (0.24–0.66) | <0.001 | 53 (63.9) | 30 (36.1) | 1.25 (0.76–2.07) | 0.383 |

| Chest and back | 21 (31.3) | 46 (68.7) | 0.89 (0.51–1.57) | 0.689 | 43 (64.2) | 24 (35.8) | 1.2 (0.70–2.08) | 0.507 |

| Belly | 11 (22.4) | 38 (77.6) | 1.48 (0.73–3.00) | 0.277 | 28 (57.1) | 21 (42.9) | 1.72 (0.94–3.16) | 0.080 |

| Physical reaction to bites (no = ref.) | ||||||||

| Itchiness | 109 (33.9) | 213 (66.1) | 0.36 (0.200.65) | <0.001 | 228 (70.8) | 94 (29.2) | 0.59 (0.37–0.95) | 0.028 |

| Redness and swelling of the skin | 90 (36.6) | 156 (63.4) | 0.42 (0.26–0.66) | <0.001 | 170 (69.4) | 75 (30.6) | 0.86 (0.57–1.30) | 0.465 |

| Difficulties sleeping or restlessness | 58 (46.4) | 67 (53.6) | 0.33 (0.21–0.52) | <0.001 | 106 (84.1) | 20 (15.9) | 0.29 (0.17–0.49) | <0.001 |

| Pain at the site of bite | 39 (48.1) | 42 (51.9) | 0.36 (0.22–0.59) | <0.001 | 60 (73.2) | 22 (26.8) | 0.74 (0.43–1.27) | 0.277 |

| Bleeding at the site of bite | 22 (61.1) | 14 (38.9) | 0.22 (0.11–0.45) | <0.001 | 27 (77.1) | 8 (22.9) | 0.62 (0.28–1.38) | 0.243 |

| Headache | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.998 | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.998 |

| Difficulties breathing | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0.24 (0.02–2.32) | 0.216 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1.22 (0.12–11.96) | 0.866 |

| Fever | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0.28 (0.01–9.77) | 0.484 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–0) | 1 |

| Blisters | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 676,690,186.31 (0–0) | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–0) | 1 |

| Time of bites (no = ref.) | ||||||||

| During sleep | 84 (36.4) | 147 (63.6) | 0.47 (0.31–0.73) | <0.001 | 167 (72.6) | 63 (27.4) | 0.64 (0.42–0.96) | 0.031 |

| Irregularly | 64 (39.8) | 97 (60.2) | 0.46 (0.30–0.70) | <0.001 | 110 (68.8) | 50 (31.3) | 0.94 (0.62–1.43) | 0.773 |

| Night (before sleeping) | 33 (32.0) | 70 (68.0) | 0.85 (0.52–1.37) | 0.500 | 63 (60.6) | 41 (39.4) | 1.53 (0.97–2.43) | 0.070 |

| Watching TV or otherwise being still | 36 (46.8) | 41 (53.2) | 0.39 (0.24–0.65) | <0.001 | 58 (76.3) | 18 (23.7) | 0.62 (0.35–1.10) | 0.103 |

| Daytime | 14 (33.3) | 28 (66.7) | 0.77 (0.39–1.51) | 0.451 | 29 (69.0) | 13 (31.0) | 0.95 (0.47–1.88) | 0.873 |

| Holding clothes or umbrellas | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | 0.73 (0.23–2.32) | 0.589 | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.16 (0.36–3.73) | 0.803 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female (ref.) | 96 (26.6) | 265 (73.4) | 226 (62.6) | 135 (37.4) | ||||

| Male | 62 (20.5) | 241 (79.5) | 1.41 (0.98–2.03) | 0.066 | 176 (58.3) | 126 (41.7) | 1.19 (0.87–1.63) | 0.266 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 0–24 | 21 (15.3) | 116 (84.7) | 4.06 (2.25–7.31) | <0.001 | 66 (47.8) | 72 (52.2) | 3.76 (2.18–6.48) | <0.001 |

| 25–44 | 43 (22.1) | 152 (77.9) | 2.60 (1.58–4.27) | <0.001 | 114 (58.2) | 82 (41.8) | 2.47 (1.48–4.13) | <0.001 |

| 45–64 | 43 (20.4) | 168 (79.6) | 2.92 (1.78–4.80) | <0.001 | 130 (61.9) | 80 (38.1) | 2.11 (1.27–3.52) | 0.004 |

| ≥65 (ref.) | 51 (42.9) | 68 (57.1) | <0.001 | 92 (77.3) | 27 (22.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Education level | ||||||||

| Primary education or below | 44 (64.7) | 24 (35.3) | 0.12 (0.07–0.21) | <0.001 | 63 (92.6) | 5 (7.4) | 0.1 (0.04–0.25) | <0.001 |

| Secondary education | 47 (21.7) | 170 (78.3) | 0.77 (0.51–1.17) | 0.219 | 136 (62.4) | 82 (37.6) | 0.71 (0.51–1) | 0.050 |

| Tertiary education (ref.) | 67 (17.7) | 311 (82.3) | <0.001 | 204 (54.0) | 174 (46.0) | <0.001 | ||

| Monthly household income | ||||||||

| <HKD 10,000 | 47 (48.0) | 51 (52.0) | 0.05 (0.01–0.19) | <0.001 | 76 (77.6) | 22 (22.4) | 0.28 (0.14–0.57) | <0.001 |

| HKD 10,000–30,000 | 72 (28.2) | 183 (71.8) | 0.12 (0.03–0.44) | 0.001 | 164 (64.6) | 90 (35.4) | 0.53 (0.30–0.95) | 0.034 |

| HKD 30,001–50,000 | 28 (18.1) | 127 (81.9) | 0.21 (0.05–0.79) | 0.022 | 81 (51.9) | 75 (48.1) | 0.89 (0.48–1.64) | 0.700 |

| HKD 50,001–80,000 | 8 (8.1) | 91 (91.9) | 0.49 (0.11–2.14) | 0.345 | 54 (54.5) | 45 (45.5) | 0.81 (0.42–1.57) | 0.540 |

| >HKD 80,000 (ref.) | 2 (3.6) | 53 (96.4) | <0.001 | 27 (49.1) | 28 (50.9) | <0.001 | ||

* p-values in bold indicate statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

In the final adjusted model with dichotomised self-rated health as the dependent variable (Table 3), physical appearance (p = 0.008), spending money on medication or doctor consultation (p = 0.04), number of bites in the past month (p = 0.023), and irregular time of bites (aOR = 0.42, 95% CI 0.24–0.74, p = 0.003) were independently associated with self-rated health. For physical appearance, increased severity of impact on daily life predicts lower self-rated health (aOR < 1, p < 0.05). Bedbug infestation became non-significant after adjustment, and in the unadjusted model, having often (uOR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.19–0.89, p = 0.025) or very often (uOR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.15–0.76, p = 0.009) bedbug infestation were more likely to have lower self-rated health compared with rarely having infestation.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression for dichotomised self-rated health regressed against fitted variables.

| Self-Rated Health (High = 1) | uOR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted p-Value * |

aOR (95% CI) |

Adjusted p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedbug infestation (Rarely = ref.) | 0.018 | 0.158 | ||

| Sometimes | 0.94 (0.42–2.07) | 0.875 | 1.14 (0.49–2.68) | 0.759 |

| Often | 0.41 (0.19–0.89) | 0.025 | 0.59 (0.25–1.41) | 0.236 |

| Very often | 0.33 (0.15–0.76) | 0.009 | 0.46 (0.19–1.10) | 0.081 |

| Physical appearance (No impact = ref.) | 0.009 | 0.008 | ||

| Slight | 0.38 (0.17–0.87) | 0.023 | 0.33 (0.14–0.81) | 0.015 |

| Moderate | 0.25 (0.11–0.61) | 0.002 | 0.21 (0.08–0.54) | 0.001 |

| Severe | 0.20 (0.07–0.56) | 0.002 | 0.18 (0.06–0.55) | 0.003 |

| Spending money medication or doctor consultation (No impact = ref.) | 0.033 | 0.040 | ||

| Slight | 1.53 (0.69–3.40) | 0.293 | 2.27 (0.93–5.50) | 0.070 |

| Moderate | 2.18 (0.94–5.06) | 0.069 | 2.42 (0.96–6.13) | 0.062 |

| Severe | 0.70 (0.27–1.80) | 0.456 | 0.89 (0.31–2.54) | 0.824 |

| No. bites in past month (0 = ref.) | <0.001 | 0.023 | ||

| 1–4 | 1.10 (0.43–2.80) | 0.850 | 0.87 (0.32–2.35) | 0.783 |

| 5–10 | 2.26 (0.78–6.54) | 0.131 | 2.09 (0.67–6.52) | 0.203 |

| >10 | 0.52 (0.20–1.34) | 0.174 | 0.62 (0.22–1.72) | 0.360 |

| Time of bites | ||||

| Irregularly | 0.39 (0.23–0.66) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.24–0.74) | 0.003 |

| Male (Female = ref.) | 1.20 (0.69–2.10) | 0.513 | ||

| Age (≥65 = ref.) | 0.073 | |||

| 0–24 | 2.07 (0.66–6.54) | 0.214 | ||

| 25–44 | 0.65 (0.24–1.72) | 0.381 | ||

| 45–64 | 0.80 (0.29–2.20) | 0.665 | ||

| Education level (Tertiary education = ref.) | 0.011 | |||

| Primary education or below | 0.30 (0.10–0.94) | 0.038 | ||

| Secondary education | 1.52 (0.83–2.78) | 0.175 | ||

| Monthly household income (>HKD80,000 = ref.) | 0.213 | |||

| <HKD 10,000 | 0.22 (0.03–1.46) | 0.116 | ||

| HKD 10,000–30,000 | 0.28 (0.05–1.65) | 0.159 | ||

| HKD 30,001–50,000 | 0.25 (0.04–1.52) | 0.131 | ||

| HKD 50,001–80,000 | 0.77 (0.11–5.61) | 0.795 | ||

| Constant | 12.50 | <0.001 | 33.09 | <0.001 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.334 | 0.410 | ||

| Omnibus tests of model coefficients | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||

| % correctly predicted | 79.1% | 79.0% | ||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow test | 0.360 | 0.318 |

* p-values in bold indicate statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

The final adjusted model with dichotomised self-rated health as the dependent variable had a pseudo R-squared of 0.41. The omnibus test of model coefficients was significant (p < 0.001); it was better at predicting self-rated health than the null model and was able to correctly predict 79% of self-rated health. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was not significant (p = 0.318); thus, the goodness-of-fit assumption was not violated. The results of multicollinearity diagnostics are provided as a Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table S2). There was no evidence of multicollinearity.

3.3. Average Hours of Sleep per Day and Bedbug Infestation

In the bivariate analysis (Table 2), increased bedbug infestation and severity of being troubled by bedbugs in the past year were associated with lower average hours of sleep per day (p < 0.01). Greater impact on daily life in the past month for all reported aspects were associated with lower average hours of sleep per day (p < 0.01). Increased number of bedbug bites in the past month was associated with lower average hours of sleep per day (p = 0.015). Only bites to the whole body were associated with lower average hours of sleep per day (p = 0.008). Bite reactions that were associated with lower average hours of sleep per day were itchiness, and difficulties sleeping or restlessness (p < 0.05). Only bites during sleep (p = 0.031) were associated with lower average hours of sleep per day. Younger age, higher education level, and higher monthly household income were associated with higher average hours of sleep per day (p < 0.001).

In the final adjusted model with dichotomised average hours of sleep per day as the dependent variable (Table 4), mental and emotional health (p = 0.016) was independently associated with average hours of sleep per day. Having severe (aOR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.15–0.71, p = 0.004) mental and emotional health impact on daily life was more likely to have lower average hours of sleep per day compared with having no impact. Difficulties sleeping or restlessness as a physical reaction to bites became non-significant after adjustment, and in the unadjusted model, those with difficulties sleeping or restlessness (uOR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.26–0.89, p = 0.02) were more likely to have lower average hours of sleep per day.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression for dichotomised average hours of sleep per day regressed against fitted variables.

| Average Hours of Sleep per Day (High = 1) | uOR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted p-Value * |

aOR (95% CI) |

Adjusted p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental and emotional health (No impact = ref.) | 0.003 | 0.016 | ||

| Slight | 0.87 (0.49–1.54) | 0.635 | 1 (0.54–1.84) | 0.993 |

| Moderate | 0.58 (0.32–1.04) | 0.068 | 0.60 (0.32–1.11) | 0.104 |

| Severe | 0.27 (0.13–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.33 (0.15–0.71) | 0.004 |

| Physical reaction to bites | ||||

| Difficulties sleeping or restlessness | 0.49 (0.26–0.89) | 0.020 | 0.64 (0.34–1.23) | 0.179 |

| Male (Female = ref.) | 1.04 (0.66–1.64) | 0.860 | ||

| Age (≥65 = ref.) | 0.005 | |||

| 0–24 | 5.17 (1.76–15.26) | 0.003 | ||

| 25–44 | 2.50 (0.90–6.92) | 0.079 | ||

| 45–64 | 1.94 (0.70–5.38) | 0.201 | ||

| Education level (Tertiary education = ref.) | 0.333 | |||

| Primary education or below | 0.41 (0.12–1.41) | 0.157 | ||

| Secondary education | 1.04 (0.62–1.74) | 0.890 | ||

| Monthly household income (>HKD80,000 = ref.) | 0.242 | |||

| <HKD 10,000 | 0.55 (0.18–1.70) | 0.298 | ||

| HKD 10,000–30,000 | 0.34 (0.13–0.89) | 0.029 | ||

| HKD 30,001–50,000 | 0.47 (0.18–1.26) | 0.133 | ||

| HKD 50,001–80,000 | 0.50 (0.18–1.37) | 0.178 | ||

| Constant | 0.88 | 0.491 | 0.78 | 0.692 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.125 | 0.216 | ||

| Omnibus tests of model coefficients | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||

| % correctly predicted | 67.9% | 69.9% | ||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow test | 0.623 | 0.087 |

* p-values in bold indicate statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

The final adjusted model with dichotomised average hours of sleep per day as the dependent variable had a pseudo R-squared of 0.216. The omnibus test of model coefficients was significant (p < 0.001), viz, the model was better at predicting average hours of sleep per day than the null model and was able to correctly predict 69.9% of average hours of sleep per day. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was not significant (p = 0.087); thus, the goodness-of-fit assumption was not violated. There was no evidence of multicollinearity (Supplementary Table S2).

4. Discussion

This is the first empirical study to investigate the patterns of bedbug bites and their health impact among bedbug victims in Hong Kong, considering bedbugs as a causal agent instead of a potential vector in transmitting diseases. This study found that most (32.7%) participants reported having >10 bites per month; increased number of bites in the past month was independently associated with lower self-rated health. Having many bedbug bites may be explained by a higher level of bedbug infestation and the biting behaviour described as ‘breakfast, lunch, and dinner’ where bedbugs bite multiple sites in a linear pattern during one instance of feeding [28]. Having more bedbug bites can make the related health impact more severe, hence lower self-rated health [9,13,14,29,30,31,32]. Irregular time of bite was also independently associated with lower self-rated health and was the second most common time of bite (37.9%); hence, having bites throughout the day may be more problematic than having bites at specified times of the day such as at night or during sleep.

This study found that bedbug bites most commonly occurred on the arms (47.8%) and legs (51%) which agrees with previous studies [9,33]. With regards to the cutaneous reactions to bedbug bites, the most common were itchiness (76.3%) and redness and swelling of the skin (58.1%), which is similar to a previous cross-sectional study that found inflammation and redness of the skin to occur in 100% of participants who experienced bedbug bites [33]. The difference between the proportion of reported cutaneous reactions between the studies may be explained by the difference in the participants’ sensitivity to bedbug bites [34], or underreporting due to the common difficulty of differentiating between bedbug bites and other arthropod bites or skin conditions [8,30,31,32].

With regards to uncommon or rare reactions to bedbug bites, this study identified one participant who reported blisters which may represent uncommon bullous reactions that are estimated to occur in 6% of bedbug bites [35]. This study also identified some participants who developed systemic reactions to bedbug bites including fever (0.3%), difficulties breathing (0.8%), and headache (3.5%). The rare occurrence of systemic reactions is consistent with the findings of previous bedbug cases and studies [9,29,36,37,38,39]. Aside from bedbug bites, systemic reactions such as headache or nausea may also result from overexposure to pesticides used for treating bedbug infestations [40].

Notwithstanding the apparent inability of bedbugs to transmit vector-borne diseases [4,5,6,7], this study found bedbug infestations to negatively affect various aspects of health, including physical and psychosocial health, which agrees with previous studies [8,9,11,12,13,14,29,30,31,32]. Particularly, physical appearance and spending money on medication or doctor consultation were independently associated with lower self-rated health. Impact on physical appearance from cutaneous reactions to bedbug bites may represent a significant and readily observable adverse effect to health [41]. Spending money on medication or doctor consultation may represent a financial burden to bedbug victims [1,10].

This study found that having bedbug infestations may reduce the quantity and quality of sleep, and the sleep disturbances from bedbug infestation are well reported in previous literature [9,12,29,30,31,32]. This study also found that having severe mental and emotional health impact on daily life from bedbug infestation was independently associated with lower average hours of sleep. Previous studies found several mental health conditions to be associated with bedbug infestations, including those that directly relate to duration of sleep, such as insomnia, or have a more complex relationship with sleep such as depression or PTSD [12,13,14].

4.1. Recommendations

Given Hong Kong’s status as an international city involved in global travel and trade, the successful control of bedbugs in Hong Kong may inform the control of the global bedbug resurgence. The same can be said for other international hubs. If bedbug infestation results in adverse health effects in an affluent city such as Hong Kong, we may expect developing countries to experience worse health outcomes from bedbug infestations despite the lack of entomological literature on bedbugs in those countries [4].

Bedbugs are a neglected issue in Hong Kong, and are considered an insignificant pest compared with others that are known vectors for infectious diseases such as mosquitoes [19,23]. Policy evaluation of bedbugs as a threat to public health needs to move beyond considering their ability to transmit vector-borne diseases to bedbugs as an agent (Figure 1), with adverse health effects to bedbug victims that go beyond physical but all aspects of health including mental, social, and financial as demonstrated in this and several other studies [8,9,11,12,13,14,29,30,31,32]. The standard of considering the importance of hematophagous ectoparasites based on their ability to transmit vector-borne diseases, as has been applied to mosquitoes, should not be applied to bedbugs. If scientific and public discourse shifts from considering bedbugs as an incompetent vector to a competent infectious agent in their own right, it may raise public concern to a level that it deserves and motivate efforts and policies against bedbugs.

Public health efforts, laws, and policies to eradicate or alleviate bedbug infestation should address its risk factors, which include crowded housing and poverty [15,21,42,43,44]. Immediate public health interventions such as extermination programs or public education on the affordable self-management strategies for bedbug infestation should be directed to at-risk groups including elderly, lower education level, lower-income households, and those living in at-risk areas such as crowded or dilapidated housing [16,18,45,46,47]. Long-term solutions include addressing housing issues; this may be considered as a ‘best buy’ for addressing bedbug infestations as it can reverberate improvements to other aspects of health and wellbeing including mental health, access to education, employment, etc.; in the context of Hong Kong, this would revolve around alleviating the vulnerabilities of living in subdivided units and providing adequate living space through improved public housing and related policies [21,48,49].

4.2. Limitations

The data from this study depend on self-reports by participants, making it difficult to measure bedbug infestation and the effects of their bites. The reductionist survey design made it difficult to comprehensively assess the health condition and sleep quality of the participant. No medical records were available to confirm any health outcomes of bedbug infestation. Furthermore, the survey did not use a standard instrument to assess the subjective sleep quality such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) or Mini Sleep Questionnaire (MSQ) [50].

There may be a proclivity among bedbug victims to volunteer as participants due to the voluntary online questionnaire being relevant to them, thus the proportion of participants who had had bedbug infestation may be arbitrarily higher.

The responses provided by the participants may be subject to their interpretation. For example, ‘headache’ may be used as a colloquialism by the participants to describe the frustration from troubles brought upon by bedbug infestation rather than the health condition. Although a picture of a bedbug was provided on the survey to minimise erroneous recognition of bedbugs or reporting on the health impact for other arthropod bites, previous study found that older people (>60-year-olds) were more likely to erroneously identify bedbugs from a picture [44], and arthropod bites—from bedbugs or otherwise—may be attributed to the wrong arthropod or other skin conditions [8,30,31,32]. Furthermore, systemic reactions such as headache may be misattributed to bedbug bites instead of from overexposure to pesticides used for treating bedbug infestations [40].

The cross-sectional study design was unable to establish the temporal relationship between the occurrence of bedbug infestation and its health impacts to the participants’ perceived health status and average hours of sleep per day. Low self-rated health or average hours of sleep per day may have existed before the bedbug infestation.

Although the analysis was weighted by age and sex, the use of volunteer sampling and online data collection may lower the representativeness of the sample. The sample may have reduced representativeness for vulnerable or disadvantaged groups who may have limited internet access and be disproportionately affected by bedbug infestation and their health impacts [10,15,16,17,18].

Although the manifestation of bedbug infestation and details of their bites are unlikely to be different across various sociocultural contexts, one should be mindful of the setting in which this study was conducted when generalising the results of this study to other settings. For example, Hong Kong has a subtropical climate, it is a high-income–high-disparity city and is one of most densely populated cities in the world with household crowding, a risk factor of bedbug infestation [15,21,42], to be a major issue.

5. Conclusions

Bedbug infestations are a pest of significant health detriment to their victims. This study brings attention to bedbug infestations and their health impacts in Hong Kong by providing empirical evidence describing the patterns of bedbug bites, including the location of bites, when they occurred, and the physical reaction to bites, and how they were associated with lower self-rated health and average hours of sleep per day among the bedbug victims. Bedbug bites impact several dimensions of health including physical, mental, social, and financial. There is a need to consider the threat of bedbugs as agents resulting in adverse health outcomes, beyond their (in)ability to transmit vector-borne diseases. To eradicate bedbugs or alleviate their health burden, public health interventions should be implemented. These may include public education and eradication programs prioritising vulnerable groups such as the elderly or those living in crowded housing, and supportive laws and policies addressing the risk factors to bedbug infestation such as alleviating crowded housing and poverty. The successful control of bedbugs in Hong Kong, an international hub, can inform the control of the global bedbug resurgence.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the participants who welcomed the researchers into their homes to make observations of bedbug infestation and collect bedbug samples, and the efforts of a group of student volunteers for their contributions in sampling and data collection.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects12111027/s1, Supplementary Table S1: English survey, Supplementary Table S2: Multicollinearity diagnostics results, Supplementary Table S3: Data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.W.; methodology, D.D., R.Y.-N.C. and S.Y.S.W.; formal analysis, E.H.C.F.; investigation, E.H.C.F.; resources, S.W.C., H.-M.L. and S.M.C.; data curation, E.H.C.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.H.C.F.; writing—review and editing, E.H.C.F., H.W., S.W.C., H.-M.L., R.Y.-N.C., S.Y.S.W., S.M.C., D.D.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All participants gave their informed consent to participate in the study. The study has been approved by the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (SBREC), of CUHK [Reference No. SBRE-19-778] and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available as a Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table S3).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.USEPA Joint Statement on Bed Bug Control in the United States from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) [(accessed on 16 March 2021)]; Available online: http://purl.fdlp.gov/GPO/gpo21927.

- 2.Davies T.G., Field L.M., Williamson M.S. The re-emergence of the bed bug as a nuisance pest: Implications of resistance to the pyrethroid insecticides. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2012;26:241–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2011.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C., Wen X. Bed Bug Infestations and Control Practices in China: Implications for Fighting the Global Bed Bug Resurgence. Insects. 2011;2:83–95. doi: 10.3390/insects2020083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zorrilla-Vaca A., Silva-Medina M.M., Escandón-Vargas K. Bedbugs, Cimex spp.: Their current world resurgence and healthcare impact. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2015;5:342–352. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(14)60795-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai O., Ho D., Glick S., Jagdeo J. Bed bugs and possible transmission of human pathogens: A systematic review. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2016;308:531–538. doi: 10.1007/s00403-016-1661-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton G.J. Bedbugs in relation to transmission of human diseases. Review of the literature. Public Health Rep. 1963;78:513–524. doi: 10.2307/4591852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delaunay P., Blanc V., Del Giudice P., Levy-Bencheton A., Chosidow O., Marty P., Brouqui P. Bedbugs and infectious diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:200–210. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahlenbeck S., Utikal J., Doggett S.L. On the rise worldwide: Bed bugs and cimicosis. Br. J. Med. Pract. 2016;9:a921. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goddard J., deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358–1366. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harlan H.J., Faulde M.K., Baumann G.J. Bedbugs. In: Bonnefoy X., Kampen H., Sweeney K., editors. Public Health Significance of Urban Pests. World Health Organization; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2007. pp. 131–153. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mekonnen D., Zenebe Y., Derbie A., Adem Y., Hailu D., Mulu W., Bereded F., Mekonnen Z., Yizengaw E., Tulu B., et al. Health impacts of bedbug infestation: A case of five towns in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2017;31:251–258. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashcroft R., Seko Y., Chan L.F., Dere J., Kim J., McKenzie K. The mental health impact of bed bug infestations: A scoping review. Int. J. Public Health. 2015;60:827–837. doi: 10.1007/s00038-015-0713-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goddard J., de Shazo R. Psychological effects of bed bug attacks (Cimex lectularius L.) Am. J. Med. 2012;125:101–103. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Susser S.R., Perron S., Fournier M., Jacques L., Denis G., Tessier F., Roberge P. Mental health effects from urban bed bug infestation (Cimex lectularius L.): A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000838. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutherland C., Greenlee A.J., Schneider D. Socioeconomic drivers of urban pest prevalence. People Nat. 2020;2:776–783. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper R.A., Wang C., Singh N. Evaluation of a model community-wide bed bug management program in affordable housing. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016;72:45–56. doi: 10.1002/ps.3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eddy C., Jones S.C. Bed bugs, public health, and social justice: Part 1, A call to action. J. Environ. Health. 2011;73:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang C., Eiden A., Singh N., Zha C., Wang D., Cooper R. Dynamics of bed bug infestations in three low-income housing communities with various bed bug management programs. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018;74:1302–1310. doi: 10.1002/ps.4830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung R. Is Hong Kong on the Verge of a Major Bed Bug Epidemic? We Talk to the Experts and Get Some Tips. South China Morning Post. Jun 14, 2017.

- 20.Cheung R. Volunteers Tackle Hong Kong Bedbug Horrors Pros Won’t Touch, and Don’t Charge a Cent to Clients Poor, Old, or Ill—And Desperate. South China Morning Post. Jul 24, 2018.

- 21.Fung E.H.C., Wong H., Chiu S.W., Hui J.H.L., Lam H.M., Chung R.Y.-n., Wong S.Y.-S., Chan S.M. Risk factors associated with bedbug (Cimex spp.) infestations among Hong Kong households: A cross-sectional study. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10901-021-09894-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NowTv Now Report: Bedbug Disaster. [(accessed on 16 July 2021)]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fgABkTkIbho.

- 23.Ting V. Bedbug Infestations Widespread in Hong Kong, Study Finds, with One Expert Warning of ‘Public Health Issue’. South China Morning Post. Sep 24, 2019.

- 24.Census and Statistics Department HKSAR Table 1A: Population by Sex and Age Group. [(accessed on 28 July 2021)]; Available online: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/web_table.html?id=1A.

- 25.Wong W.S., Fielding R. Prevalence of insomnia among Chinese Adults in Hong Kong: A Population-Based Study. J. Sleep Res. 2011;20:117–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagelkerke N.J.D. A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika. 1991;78:691–692. doi: 10.1093/biomet/78.3.691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dormann C.F., Elith J., Bacher S., Buchmann C., Carl G., Carre G., Marquez J.R.G., Gruber B., Lafourcade B., Leitao P.J., et al. Collinearity: A review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography. 2013;36:27–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2012.07348.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peres G., Yugar L.B.T., Haddad Junior V. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner sign: A hallmark of flea and bedbug bites. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2018;93:759–760. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doggett S.L., Dwyer D.E., Penas P.F., Russell R.C. Bed bugs: Clinical relevance and control options. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012;25:164–192. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05015-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doggett S.L., Russell R. Bed bugs What the GP needs to know. Aust. Fam. Physician. 2009;38:880–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parola P., Izri A. Bedbugs. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2230–2237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas I., Kihiczak G.G., Schwartz R.A. Bedbug bites: A review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2004;43:430–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dehghani R., Hashemi A., Takhtfiroozeh S.M., Chimehi E., Chimehi E. Bed bug (Cimex lectularis) outbreak: A cross-sectional study in Polour, Iran. Iran. J. Dermatol. 2016;19:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinhardt K., Kempke D., Naylor R.A., Siva-Jothy M.T. Sensitivity to bites by the bedbug, Cimex lectularius. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2009;23:163–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.deShazo R.D., Feldlaufer M.F., Mihm M.C., Jr., Goddard J. Bullous reactions to bedbug bites reflect cutaneous vasculitis. Am. J. Med. 2012;125:688–694. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phan C., Brunet-Possenti F., Marinho E., Petit A. Systemic Reactions Caused by Bed Bug Bites. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63:284–285. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liebold K., Schliemann-Willers S., Wollina U. Disseminated bullous eruption with systemic reaction caused by Cimex lectularius. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2003;17:461–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ukleja-Sokolowska N., Sokolowski L., Gawronska-Ukleja E., Bartuzi Z. Application of native prick test in diagnosis of bed bug allergy. Postepy Derm. Alergol. 2013;30:62–64. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2013.33382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minocha R., Wang C., Dang K., Webb C.E., Fernández-Peñas P., Doggett S.L. Systemic and erythrodermic reactions following repeated exposure to bites from the Common bed bug Cimex lectularius (Hemiptera: Cimicidae) Austral Entomol. 2017;56:345–347. doi: 10.1111/aen.12250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forrester M.B., Prosperie S. Reporting of bedbug treatment exposures to Texas poison centres. Public Health. 2013;127:961–963. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang L. A Victoria‘s Secret Model Is Suing a Hotel after She Was Allegedly ‘Massacred’ by Bed Bugs in One of Its Rooms. [(accessed on 8 August 2021)]. Available online: https://www.insider.com/victorias-secret-model-sues-hotel-alleged-bed-bug-bites-2018-7.

- 42.Gounder P., Ralph N., Maroko A., Thorpe L. Bedbug complaints among public housing residents-New York City, 2010–2011. J. Urban Health. 2014;91:1076–1086. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9859-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ralph N., Jones H.E., Thorpe L.E. Self-Reported Bed Bug Infestation Among New York City Residents: Prevalence and Risk Factors. J. Environ. Health. 2013;76:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheele J.M., Crandall C.J., Chang B.F., Arko B.L., Dunn C.T., Negrete A. Risk Factors for Bed Bugs Among Urban Emergency Department Patients. J. Community Health. 2019;44:1061–1068. doi: 10.1007/s10900-019-00681-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alizadeh I., Jahanifard E., Sharififard M., Azemi M.E. Effects of Resident Education and Self-Implementation of Integrated Pest Management Strategy for Eliminating Bed Bug Infestation in Ahvaz City, Southwestern Iran. J. Arthropod. Borne Dis. 2020;14:68–77. doi: 10.18502/jad.v14i1.2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bennett G.W., Gondhalekar A.D., Wang C., Buczkowski G., Gibb T.J. Using research and education to implement practical bed bug control programs in multifamily housing. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016;72:8–14. doi: 10.1002/ps.4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang C., Saltzmann K., Bennett G., Gibb T. Comparison of Three Bed Bug Management Strategies in a Low-Income Apartment Building. Insects. 2012;3:402. doi: 10.3390/insects3020402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chan S.M., Wong H., Chung R.Y., Au-Yeung T.C. Association of living density with anxiety and stress: A cross-sectional population study in Hong Kong. Health Soc. Care Community. 2021;29:1019–1029. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong H., Chan S.M. The impacts of housing factors on deprivation in a world city: The case of Hong Kong. Soc. Pol. Admin. 2019;53:872–888. doi: 10.1111/spol.12535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fabbri M., Beracci A., Martoni M., Meneo D., Tonetti L., Natale V. Measuring Subjective Sleep Quality: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:1082. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available as a Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table S3).