Abstract

Clinical research is vital to the discovery of new cancer treatments that can enhance health and prolong life for cancer patients, but breakthroughs in cancer treatment are limited by challenges recruiting patients into cancer clinical trials (CT). Only 3–5% of cancer patients in the United States participate in a cancer CT and there are disparities in CT participation by age, race and gender. Strategies such as patient navigation, which is designed to provide patients with education and practical support, may help to overcome challenges of CT recruitment. The current study evaluated an intervention in which lay navigators were utilized to provide patient education and practical support for helping patients overcome barriers to CT participation and related clinical care. A patient barrier checklist was utilized to record patient barriers to CT participation and care, actions taken by navigators to assist patients with these barriers, and whether or not these barriers could be overcome. Forty patients received patient navigation services. The most common barriers faced by navigated patients were fear (n = 9), issues communicating with medical personnel (n = 9), insurance issues (n = 8), transportation difficulties (n = 6) and perceptions about providers and treatment (n = 4). The most common activities undertaken by navigators were making referrals and contacts on behalf of patients (e.g., support services, family, clinicians; n = 25). Navigators also made arrangement for transportation, financial, medication and equipment services for patients (n = 11) and proactively navigated patients (n = 8). Barriers that were not overcome for two or more patients included insurance issues, lack of temporary housing resources for patients in treatment and assistance with household bills. The wide array of patient barriers to CT participation and navigator assistance documented in this study supports the CT navigator role in facilitating quality care.

1. Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States (US), second only to heart disease (National Center for Health Statistics, 2017). It is estimated that in, 2017, 600,920 people in the US will die from cancer (American Cancer Society, 2017). Clinical research is vital to the discovery of new cancer treatments that can enhance health and prolong life for cancer patients. However breakthroughs in cancer treatment are limited by challenges recruiting patients into cancer clinical trials (CT). In the US, approximately 20% of cancer patients are eligible for a cancer CT, and 15–25% of eligible patients participate in a CT (National Cancer Institute (NCI). American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), 2010). Thus, only 3–5% of cancer patients in the US actually participate in a cancer CT (National Cancer Institute (NCI). American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), 2010).

Based on epidemiological studies that have examined CT participation enrollment fractions by demographic subgroups, disparities in CT participation among demographic subgroups of the population are evident. The likelihood of CT participation decreases with age. Compared to individuals between the ages of 30–64, those who are ages 65–74 are 0.43 times as likely and those who are ages 75+ are 0.15 times as likely to participate in a CT (Murthy, Krumholz, & Gross, 2004). Men are 1.2–1.8 times as likely as women to participate in cancer CTs (Du, Gadgeel, & Simon, 2006; Murthy et al., 2004). Compared to Caucasians, African Americans (AAs) and Hispanics are approximately 0.7 times as likely to participate in a CT (Murthy et al., 2004). Additionally AAs report more misperceptions and concerns about research than other groups, which may be attributable to historical research mistreatment (Corbie-Smith, Thomas, & St George, 2002; Gadegbeku et al., 2008; Gamble, 1997).

Under-representation of demographic subgroups in research poses a threat to the generalizability of CT results. For example, AAs and the elderly not only have lower rates of CT participation, but also have higher rates of cancer incidence and mortality (Howlader et al., 2011) and poorer overall health status (BRFSS, 2018). Without adequate representation among demographic subgroups in CTs, researchers cannot learn about potential sub-group differences in therapeutic response and toxicities for therapies being tested and ensure the generalizability of CT findings.

Based on averages from observational studies, between 29% and 49% of patients offered a CT option refuse to participate (Jenkins & Fallowfield, 2000; Klabunde, Springer, Butler, White, & Atkins, 1999; Lara et al., 2001). Interventions to provide patients with CT education and practical support to overcome barriers to CT participation and related clinical care are a promising strategy to improve CT participation. Patients considering a CT option face well-documented barriers to CT participation. These include misperceptions and lack of understanding of the CT option and logistical issues such as cost, transportation and complex clinical regimens (Ford et al., 2008). Despite disparities in CT participation among population subgroups, the results of another study that provided structured education for research participation suggests that when AAs and Caucasians are presented with the same research opportunities, they are equally likely to agree to participate (Durant, Legedza, Marcantonio, Freeman, & Landon, 2011). This finding raises the possibility that health disparities in research participation are amenable to intervention.

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) summarized consensus recommendations for research strategies that need to be tested for improving patient participation in CTs (Denicoff et al., 2013). Patient navigation has been recommended by the NCI and the ASCO as a strategy that may help to improve recruitment and retention of patients in CTs (Denicoff et al., 2013). In the clinical setting, patient navigation generally refers to strategies that provide personal assistance to help patients overcome specific educational, communication, and logistical barriers to treatment and follow up medical care. Since patient navigation is an individually tailored and interactive intervention, it has strong potential as a strategy to improve personalized CT decision-making and enrollment. To fill this gap in the evidence, our research team carried out a study to evaluate the effect of a lay navigation intervention that utilized lay navigators to help patients overcome the issues that pose barriers to CT participation (Bryant, Williamson, Cartmell, & Jefferson, 2011; Cartmell et al., 2016). The current study reports on the barriers that patients in the study encountered to CT participation and related clinical care, activities taken by navigators to assist over come these barriers, and the extent to which navigators were able to address these barriers.

2. Methods

The purpose of this descriptive quantitative study was to characterize how patient navigators can help cancer patients overcome barriers to cancer CT participation and clinical care. Three specific aims were evaluated to summarize: (1) barriers to CT participation and clinical care experienced among navigated patients; (2) actions taken by navigators to assist patients with these barriers; and (3) the extent to which navigators were able to help patients overcome these barriers. To assess these study aims, navigators used a structured patient barrier checklist to record patient barriers, navigator actions to assist patients, and whether or not they were able to resolve these barriers. This form was based upon the NCI Patient Navigation Research Program’s standardized patient log (Freund et al., 2008) and modified to evaluate additional CT-related barriers to care.

2.1. Background of CT navigation intervention

The CT navigation intervention and training program have been previously described in detail (Bryant et al., 2011; Cartmell et al., 2016). Briefly, an overview of the study is provided. The study, which was conducted at three NCI-affiliated cancer centers in the Southeast US, took place between 08/2010 and 10/2011. All study sites had access to the full portfolio of NCI therapeutic cancer trials. To be eligible for the study, patients had to be 18 years of age or older, planning to receive primary therapy at the cancer center and be eligible for a therapeutic CT. The study was approved by the IRBs at each cancer center.

All three study sites had one navigator who worked 20h per week. Patients in the clinic were screened for therapeutic trial eligibility. Potentially eligible CT candidates were invited to enroll in the CT navigation study. The initial navigation started when the CT navigator and the patient watched a 17-min educational video developed by the NCI to provide basic education about CT education. Following the video, the navigator then opened discussion with the patient about the CT, answered their questions about the CT when appropriate, or referred the question to the appropriate clinical team member. The navigator then used the patient barrier checklist (Freund et al., 2008) to screen the patient for barriers to care that might affect clinical treatment and/or CT participation and offered assistance to help mitigate these barriers to care. After this initial session, the navigator assisted the patient with barriers to CT participation and clinical care by: (1) sending reminders to help enhance compliance with the trial protocol, (2) serving as a liaison between patient and clinical team for implementation of the patient’s care plan, (3) mitigating logistical barriers to CT participation, and (4) delivering emotional support, either directly by referring them to resources. Navigators contacted patients by phone or personal contact at least once per week to reassess previously identified barriers and identify new barriers.

2.2. Conceptual framework

The Chronic Care Model (CCM) was used in this study to organize the types of roles and responsibilities of navigators that can help patients to overcome barriers to CT participation (Wagner, 1998). This widely used model describes health care system elements to facilitate delivery of high quality chronic disease care. Model elements include: (1) community resources and policies, (2) health system organization, (3) self-management support, (4) delivery system design, (5) decision support and (6) clinical information systems. The CCM has been validated for use across a wide range of chronic diseases and was adapted for use in this navigation intervention. CT navigators support the six elements contained in the CCM. In regard to “community resources and policies,” navigators mobilize community resources to meet cancer patient needs by establishing relationships with community services and referring patients for services such as housing and financial assistance. In regard to “organizational commitment to health system changes,” the navigation intervention was conceptualized by cancer center leaders to improve low accrual of patients in cancer CTs. This provides evidence of support for the intervention by cancer center leaders. In regard to “self management support,” navigators ensure that patients understand their role in maximizing the likelihood of successful treatment. In regard to “delivery system design,” the navigation intervention transforms the process of delivering care by adding a lay navigator to the care team to facilitate more culturally-tailored, patient-centered care. In regard to “decision support,” navigators provide patients with evidence-based CT education and facilitate medical information exchange between patient and care team. In regard to “clinical information systems,” navigators support the clinical information system by relaying appointment reminders contained in the clinical information system to patients. In the context of the CCM, the navigator’s facilitation of these healthcare system elements can promote productive interactions between an informed, active patient and a prepared, proactive practice team, with an end result being better patient care.

2.3. Measurement

A patient barrier checklist was used to document patients’ barriers to CT participation and related clinical care and actions taken by navigators to resolve these barriers. This checklist is based on the NCI Patient Navigation Research Program’s standardized patient log (Freund et al., 2008) and was adapted to include items specific to CTs. Examples of response options added to incorporate CT specific barriers included patient misperceptions about CTs and patient insurance not covering CT participation. The barrier log included the following variables: date and length of navigation encounters, type of encounter (e.g., home visit, phone call to patient), barriers to CT participation and related clinical care (e.g., transportation, housing, social support) and actions taken by navigators to assist patients with these barriers (e.g., referrals made, education, scheduling appointments). The barrier log enabled collection of the time it took navigators to assist with each type of barrier. These data could be aggregated to track total navigation time to assist with barriers. It was not possible to track overall navigation time because the log did not include a variable to track the time it took to view the CT educational video with the patient in the initial encounter.

Navigators systematically assessed patients in their navigation caseload for barriers that might prevent CT participation or receipt of optimal care using the structured patient barrier checklist. They documented patient barriers and their navigation action plans to resolve these barriers. In addition, a free form text field was added to the barrier checklist to enable the navigators to describe in their own words more about the barriers and their navigation activities. Barriers were initially assessed at entry to navigation and were continually reassessed throughout the CT decision-making and participation period.

2.4. Data analysis

The patient navigator transferred data from the barrier checklist into the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database for data management. The first step in data analysis was to examine the raw data for patient barriers and navigator actions. Data were examined to determine if there was overlap within any of the barrier categories and if any of the barrier categories could be combined. The two categories of “Perceptions of Treatment” and “Beliefs about Providers” were combined because both of these types of barriers required similar navigation interventions: a need to educate patients regarding beliefs that could jeopardize treatment outcomes.

The frequency of each type of barrier (e.g., transportation) and specific details about the barrier (e.g., public transportation not easily accessible) was calculated. Similarly, the frequency of each type of action taken by navigators to assist patients was calculated overall and by barrier type. Medians and ranges were calculated for: (1) barriers per patient, (2) navigation time per patient and (3) navigation time per barrier. Further assessment described the extent that navigator actions were able to resolve barriers.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 40 patients who received patient navigation services. Most navigated patients were Caucasian (75%), non-Hispanic (98%), male (73%) and married (68%). While most were insured (93%), 69% did not have a college degree and 33% reported being “not at all” or “somewhat” confident to fill out medical forms. Eighty-five percent of participants had non-small cell lung cancer, with the remainder having small cell lung cancer or esophageal cancer. The majority of cancers were late stage cancers, consistent with the expected stage at presentation for lung and esophageal cancers that did not have an evidence-based early detection modality during the study period.

Table 1.

Characteristics of navigated patients.

| Characteristic | Category | Navigated patients (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Age | Mean (SD) | 63.10 | (9.56) |

| Race | Caucasian | 30 | 75.0 |

| African American | 10 | 25.0 | |

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic | 39 | 97.5 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Gender | Male | 29 | 72.5 |

| Female | 11 | 27.5 | |

| Insurance status | Uninsured | 3 | 7.5 |

| Insured | 37 | 92.5 | |

| Cancer Center Study Site | Charleston, SC | 16 | 40.0 |

| Savannah, GA | 10 | 25.0 | |

| Spartanburg, SC | 14 | 35.0 | |

| Marital status | Not married | 13 | 32.5 |

| Married/living with partner | 27 | 67.5 | |

| Education level | Less than high school | 5 | 12.8 |

| High school graduate | 11 | 28.2 | |

| Some college/vocational training | 11 | 28.2 | |

| Confidence completing Medical forms | Not at all/somewhat | 13 | 33.3 |

| Quite a bit/extremely | 26 | 66.6 | |

| Type of cancer | Non-small cell lung | 34 | 85.0 |

| Small cell lung | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Esophageal | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Stage at diagnosis | Early stage | 0 | 0.0 |

| Late stage | 35 | 85.0 | |

| Unknown | 5 | 15.0 | |

3.2. Patient barriers and navigator actions

The barriers experienced by patients and navigator actions to assist patients with these barriers is summarized in this section.

3.2.1. Patient barriers to care

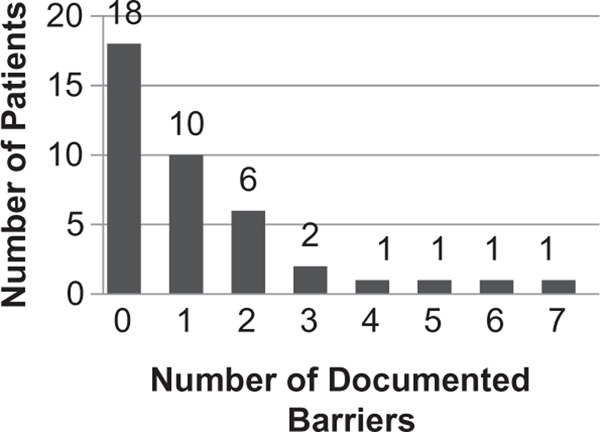

Fig. 1 provides a summary of the number of barriers documented per patient. Among the 40 patients who participated in the navigation intervention, 18 patients had no documented barriers (45%), 10 patients had 1 barrier (25%), 6 patients had 2 barriers (15%), 2 patients had 3 barriers (5%) and 4 patients had 4–7 barriers (10%). The median number of barriers documented per patient was 1 and ranged from 0 to 7 barriers per patient. The bulk of barriers were clustered in a small subset of navigated patients. Eighty percent of barriers occurred in 30% of navigated patients and 56% of barriers occurred in 15% of patients.

Fig. 1.

Number of barriers per navigated patient.

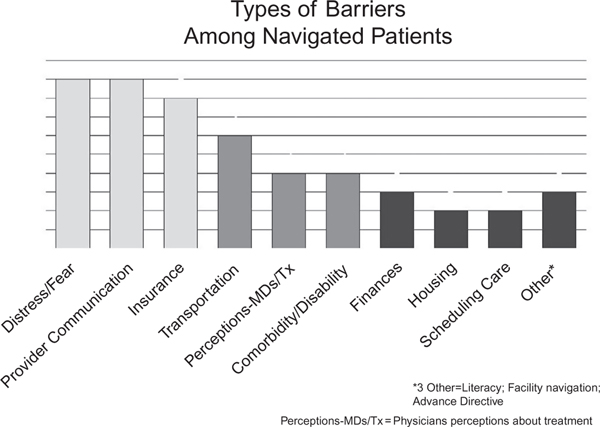

Fig. 2 provides an overview of the type and frequency of these barriers. Fifty barriers were documented among the 22 navigated patients with barriers across the three study sites. The most commonly reported barriers faced by navigated patients were fear (n = 9) and issues regarding communication with medical personnel (n = 9), followed by insurance issues (n = 8), transportation difficulties (n = 6), perceptions about providers and treatment (n = 4), disability (n = 4), finances (n = 3), housing (n = 2), scheduling care (n = 2) and other barriers. Each of these types of barriers and the actions taken by patients to resolve the barriers are described in further detail.

Fig. 2.

Types of barriers experienced by navigated patients.

3.2.2. Navigator activities

Seventy three actions were carried out by navigators to assist the 22 navigated patients who reported barriers to care. These actions are summarized in Table 2. The most common type of activity carried out by navigators was making referrals and contacting patients and other individuals on their behalf with whom they needed to make contact (e.g., support services, family, clinicians; n = 25). Navigators also commonly made arrangement for transportation, financial, medication and equipment services for patients (n = 11), and spent time proactively navigating patients (n = 8).

Table 2.

Navigator actions to assist patients with barriers (n = 73 total actions).

| Referrals/direct contact (n = 25) | Call patient (n = 2) |

| Make referral for social services (n = 2) | |

| Make referral for health care services (n = 1) | |

| Directly contact social service agencies (n = 3) | |

| Directly contact family (n = 9) | |

| Directly contact other support system (n = 4) | |

| Directly contact other healthcare providers (n = 4) | |

| Arrangements (n = 11) | Arrange for transportation (n = 3) |

| Arrange for financial assistance (n = 5) | |

| Arrange for medication assistance (n = 2) | |

| Arrange for equipment and supplies (n = 1) | |

| Proactive navigation (i.e., not related to a barrier) (n = 8) | Appointment/info verification/info gathering (n = 7) |

| Educating staff of patient’s special needs (n = 1) | |

| Records/recordkeeping (n = 8) | Helping patient complete paperwork (n = 5) |

| Request records/imaging-organize health info (n = 2) | |

| Provide documents to healthcare providers (n = 1) | |

| Education (n = 6) | Educate verbally (n = 3) |

| Distribute print and/or audio-visual materials (n = 3) | |

| Support (n = 6) | Provide emotional support, active listening (n = 6) |

| Accompaniment (n = 4) | Accompany to healthcare services (n = 2) |

| Accompany to other services (n = 2) | |

| Scheduling appointments (n = 3) | Schedule/reschedule appointment (n = 1) |

| Call to remind patient of appointment (n = 2) | |

| Other (n = 2) | Other (n = 2) |

For the 50 barriers documented by the navigators, the number of contacts and amount of navigation time required per barrier are characterized. The median number of contacts per barrier was 1 and ranged between 1 and 11 contacts. The median reported navigation time per barrier was 20min and ranged between 17 and 240min. Navigation time per barrier was less than 30min for 48% of barriers, between 30 and 59min for 20% of barriers and between 1 and 4h for 32% of barriers.

3.2.3. How navigators assisted patients with each type of barrier

Table 3 summarizes the types of barriers experienced by navigated patients and the actions performed by the navigators to assist these patients. The number of barriers does not necessarily equal the number of navigator actions because navigators may have performed no action or many actions per barrier.

Table 3.

Patient barriers and navigator actions.

| Barrier type | Specific barriers | Navigator actions |

|---|---|---|

| Fear (n = 9) | Fear of dying (n = 4) | Directly contact family (n = 1) and other support systems (n = 1) |

| Needs someone to talk to (n = 3) | Provide emotional support and active listening (n = 5) | |

| Fear of family not being able to cope (n = 1) | Educate patient verbally (n = 1) and educate staff of patient’s special needs (n = 1) | |

| Fear of treatment (n = 1) | Accompany to healthcare services (n = 1) | |

| Communication with medical personnel (n = 9) | Doesn’t understand what asked to do (n = 3) regarding when is next appointment, form of medication to take and nutrition needs to remain CT eligible | Directly contact family (n = 1) and providers (n = 3) |

| Medical forms too complicated (n = 2) | Appointment verification (n = 1) | |

| Difficulty answering provider questions and incorrectly reporting meds (n = 2) | Obtain lab sample from patient (n = 1) | |

| Needs to speak with provider to ask what meds to take for side effects and to schedule appointment (n = 2) | Request records/imaging (n = 1) | |

| Insurance (n = 8) | Can’t afford high co-pay/deductible (n = 1) | Direct contact with patient (n = 1), family (n = 1) and support system (n = 1) |

| Doesn’t understand what insurance covers (n = 1) | Accompany to other services (n = 1); Arrange for financial (n = 1) and medication assistance (n = 2) | |

| No health insurance (n = 1) | Appointment info/verification (n = 1) | |

| Overwhelmed by insurance paperwork for Medicaid, short term disability, and a cancer policy (n = 5) | Helping patient complete paperwork (n = 2); Request records/imaging (n = 1) | |

| Provide documents to healthcare providers (n = 1) | ||

| Transportation (n = 6) | Can’t afford bus/train fare, gas (n = 4) | Direct contact with family (n = 1), other support system (n = 1) and social service (n = 1) |

| Arrange Medicaid transportation for patients (n = 4) and making referrals to social service agencies (hospital social worker, Department of Social Services [DSS], church) (n = 4) | ||

| Helping patient complete paperwork (n = 2) | ||

| Public transport not readily available (n = 2) | Schedule/reschedule appointment (n = 1) | |

| Appointment/info verification, or info seeking/ gathering (n = 1) | ||

| Call to remind patient of appointment (n = 2) | ||

| Perceptions about provider and treatment (n = 4) | Felt doctor giving up on them in CT (n = 2) | Direct contact with family (n = 3), other support system (n = 1) and other healthcare providers (n = 1) |

| Believes treatment medications will make side effects worse (n = 1) | Provide emotional support, active listening (n = 1) | |

| Doesn’t think CT treatment will help (n = 1) | ||

| Medical co-morbidities and disability (n = 4) | Physical weakness (n = 3) | Directly contact family (n = 2) and other healthcare providers (n = 1) |

| Arrange for equipment and supplies (n = 1) | ||

| Accompany to healthcare services (n = 1) | ||

| Co-morbidities-obesity (n = 1) | Make referral for weight management to get weight under control for treatment (n = 1) | |

| Finances (n = 3) | Can not afford household bills (n = 2) | Directly contact social service (n = 1) and other support system resources such as American Cancer Society (ACS), Wal-Mart, and utility companies (n = 1) |

| Arrange for financial assistance (n = 1) | ||

| Can’t afford over the counter supplements needed during treatment (n = 1) | Arrange for financial assistance (n = 1) via product coupons and website to help with cost of ancillary medical products | |

| Housing (n = 2) | Need temporary housing for treatment (n = 2) | Educate verbally about temporary housing options (n = 1) |

| Distribute print/audio-visual materials (hotel list) (n = 1) | ||

| Appointment/info verification, or info seeking/ gathering for housing (n = 1) | ||

| Problem scheduling care (n = 2) | Appointment date/time not convenient (n = 2) | Appointment/info verification, or info seeking/ gathering (n = 2) |

| Other (n = 2) | Navigation of healthcare facility (n = 1) | Accompany to other services (n = 1) |

| Advance directive (n = 1) | Referral to provider (n = 1) | |

| Literacy (n = 1) | Unfamiliar/do not understand medical terms (n = 1) | Helping patient complete medical paperwork (n = 1) |

3.2.3.1. Fear

The nine fear-related barriers included fear of dying (n = 4), needing someone to talk to (n = 3), fear that family could not cope with cancer (n = 1) and fear of treatment (n = 1). To assist with these fears, navigators most frequently provided emotional support and active listening (n = 5). They also contacted families to check on them (n = 1) and contacted the hospital chaplain to provide additional support for the patient (n = 1). For a patient concerned about what would happen to a relative if they died, a navigator educated the patient about available resources (n = 1) and educated staff about the patient’s individual needs (n = 1).

Quotations from the navigators illustrate how navigators assisted patients with issues of fear. One navigator described helping a patient who was afraid of dying and concerned that the medication would not help: “I called the chaplain in to talk with the patient…and also asked the patient to discuss this concern with the doctor when he came in.” Another navigator described providing support for a frightened family member: “The patient came in with his wife…he was in a wheel chair and very frail. When I entered the room, I found that his wife was shaken. I sat with the patient and his wife. I simply tried to comfort her, giving her a hug, and letting her know that all members of the team care about them and are here to assist them. I know at times caregivers can feel like they are alone and have no one to turn to.” For another patient who feared treatment, a navigator described: “I sat in the treatment room with her for two hours talking to her and calming her down because her husband had to leave.”

3.2.3.2. Communication with providers

The nine barriers related to communication with medical providers included patients not understanding what the clinical team had asked them to do (n = 3), complicated medical forms (n = 2) and other communication barriers (n = 4). For patients who did not understand what clinicians had asked them to do, patients needed to know when clinic visits were scheduled (n = 1), what form of a prescribed medication to take (n = 1) and how to follow provider instructions for modifying diet to meet CT eligibility requirements (n = 1). A single patient encountered two barriers when medical forms were too complicated. In trying to get disability paperwork completed, assistance was needed to obtain disability forms and to get the provider to complete the forms. The other communication barriers occurred when patients had difficulty communicating medical history and current medications to providers (n = 2) and when patients needed help setting up return visits for routine appointments and for re-drawing lab work for CT eligibility (n = 2).

Quotations from the navigators illustrate how navigators facilitated patient-provider communication. Navigators frequently described how they clarified medication questions for patients. One navigator said: “In talking to the patient, I found out that the patient’s wife was not giving him all the prescribed medications and that she had not provided a complete list of all the medications, including those from the patient’s primary care provider.” The navigator then arranged for the patient and provider to meet to clarify the medication regimen. Other navigators described helping with medication communication by: “speaking with the provider about medical questions the patient had related to side effects and medications that could be taken” and “making a journal for the patient to track their medications.” Another navigator described how she facilitated communication with providers about complex medical paperwork. She obtained disability paperwork, sent it to the provider to complete and “went to check on the disability letter for the patient so that they did not have to make a special trip to the hospital for it.” Another navigator described helping a patient understand and comply with lab work needed to establish CT eligibility: “The patient was given a urine container for her specimen and a doctor’s order. The patient will have to return with the 24h urine sample for creatinine clearance. The patient’s appointment was rescheduled so she could bring back the urine.” The navigator ensured that the patient understood when to return to clinic with the specimen.

3.2.3.3. Insurance

The eight insurance-related barriers included being overwhelmed by insurance paperwork (n = 5), being unable to afford a medication co-pay (n = 1), not understanding what insurance would cover (n = 1) and not having insurance (n = 1). Three of the five barriers related to insurance paperwork occurred for one patient. These barriers included needing help getting medical records for disability insurance, needing physician prescription for a medication and needing help with paperwork required by insurance to cover medication. The other two insurance paperwork-related barriers occurred in one patient who needed help with paperwork to activate a cancer insurance policy and another patient whose provider had not completed their disability insurance paperwork correctly.

For patients with insurance barriers, navigators most commonly helped arrange financial (n = 1) and medication assistance (n = 2). Navigators also completed insurance paperwork (n = 2), obtained records and imaging needed by insurance companies (n = 1) and provided insurance documents to healthcare providers. Other navigator actions to assist with insurance barriers included making contact with patients (n = 1), their families (n = 1) and support systems (n = 1), accompanying patients to other service providers (n = 1) and verifying patient appointments (n = 1).

Quotations from the navigators further illustrate how navigators assisted patients with insurance barriers. One navigator described: “I helped the patient fill out papers for a cancer policy they just had taken out. I faxed papers in for her and gave her a copy of the confirmation that it went through. Another navigator said: “I helped a family member get medical records together so she could go apply for his Medicaid and disability check.” Other navigators helped patients with insurance paperwork by referring them to a social worker or financial counselor. One navigator described how she helped a patient to sort out what their insurance would cover: “I called CVS and asked why Medicaid was not paying for the medicine and she reported that it was showing inactive. I called Medicaid the next morning and she explained that he did not have regular Medicaid but it pays his Medicare premium. I explained the situation to the doctor and his nurse, and the nurse said she would work on getting him assistance.”

3.2.3.4. Transportation

The six transportation-related barriers included being unable to afford bus/train fare or gas (n = 4) and public transportation not being easily accessible (n = 2). Four of the six barriers were for one patient who needed help with multiple trips to the clinic for treatment appointments. The other two barriers occurred in two patients who also needed help with transportation to the clinic for treatment appointments.

For patients with transportation barriers, navigators assisted with transportation by (1) arranging Medicaid transportation for Medicaid patients (n = 4) and (2) referring patients without Medicaid to resources for assistance with gas and volunteers to provide transportation to appointments (n = 4). For patients without Medicaid, navigators made referrals to hospital social workers, the department of social services and churches for transportation assistance and helped to complete financial paperwork for these services (n = 2). Navigators spent time scheduling (n = 1), verifying (n = 1) and sending reminders about transportation appointments (n = 2). Navigators also spent time contacting patients’ family (n = 1), other support system resources (n = 1) and social service providers (n = 1) regarding transportation.

Quotations from navigators further illustrate how navigators helped patients with transportation barriers. Navigators described: “I made reservations with Logisticare for the patient to be picked up at home and transported to the facility” and “I made arrangements for the patient to be transported by Logisticare for their Gamma Knife procedure.” Navigators also described how they helped patients not eligible for Medicaid transportation: “I referred the patient to the social worker to help with the resources needed to get to the clinic for treatment on trial” and “I called the social worker and told him this gentleman needed help getting transportation to and from the clinic for treatment.”

3.2.3.5. Patient perceptions about providers and treatment

The four barriers related to patient perceptions about providers and treatment including feeling the provider was giving up on their treatment (n = 2), a family member hesitant to administer medication due to unwanted side effects (n = 1) and a belief that treatment would not help (n = 1). To assist with these barriers, navigators contacted family (n = 3), healthcare providers (n = 1) and other support systems (n = 1) to help talk through patient concerns. Navigators also provided emotional support and active listening (n = 1).

One navigator described how she assisted a patient and his wife who felt their doctor had given up on them when he took the patient off of the CT due to toxicities experienced during treatment. The patient expressed he had hoped he was going to get a ‘better chance’ at getting to complete the treatment regimen he was taking in the CT. I assured the patient and his wife that this decision was done because of his health, and that they should bring up their disappointment with their doctor. The couple brought up their feelings with the doctor, and were told that when the patient was able to do housework, he would be treated again, until then, he was not healthy enough to do the treatments.” Another navigator described: “I talked with the patient about why they felt they might want another doctor. The patient’s wife just wanted to make sure that she was getting the best care for her husband and that the doctor was not just giving up on him. I reassured the patient and his family that the doctor was a good doctor and that he treats all of his patients with care no matter what stage of cancer they might have.”

One navigator described how she helped to ensure that a patient was taking medications correctly: “After a series of phone calls, I found out that the patient was not getting his medications as directed. The patient’s wife stated that she read the side effects on the package, one of which was nausea and vomiting. This is one of the symptoms the patient was experiencing. In an effort to keep the patient from experiencing the side effects, she stopped giving him the medication. When the patient and his wife shared this with me, I informed the doctor and he conducted a teaching session to inform the couple how to take each medication and what each one did. The doctor asked me to retype the list of medications and print in large letters for the patient’s wife to use as a guide. He also asked me to check up on the patient to ensure they were taking the medication appropriately. The patient expressed their understanding afterwards.” Another navigator described how she assisted a patient who was afraid that participation in a CT might worsen her health. The navigator described: “I called in the nurse and had her to speak with the patient and his family again about the clinical trial and she provided them with some more education about the trial.”

3.2.3.6. Medical co-morbidities and disability

Four barriers related to medical co-morbidities occurred in patients whose poor physical health was making it difficult to come for treatment (n = 4). To assist with issues related to poor physical health, navigators spent time contacting family members (n = 2) and healthcare providers (n = 1). Navigators also arranged for a wheelchair (n = 1), accompanied patients to a healthcare appointment (n = 1) and made a referral to a nutritionist (n = 1).

Quotations from navigators further illustrate how navigators assisted patients with medical co-morbidities and disability. One navigator described: “The doctor wants to take the patient off of protocol because he is losing weight rapidly and has become very weak. I read the patient’s office notes and went and discussed the patient’s weight with the nurse. I told her that I would refer the patient to the nutritionist when I saw the patient. I went to see the patient and suggested him seeing the nutritionist and the sister agreed. I went to the nutritionist’s office and asked if she could see the patient while he was in infusion. Another navigator described: “The patient’s wife expressed the desire to get a handicapped parking placard. I provided the patient’s wife with the application they needed and informed the nurse they would need a prescription when they returned for their appointment.” Another navigator said: “I sat with the patient and his wife, and she expressed that because of her husband’s weakness, she is afraid to leave him at home alone, and as a result has been neglecting her doctor’s appointments and other errands. I suggested hospice respite care, and she said that she would really like that because she would prefer to have medical staff available to her husband in her absence. I talked to the doctor and nurse to make sure this process was started in a timely fashion.”

3.2.3.7. Finances

Three finance-related barriers included being unable to afford household bills (n = 2) and an over-the-counter skin care treatment product recommended by their provider (n = 1). To assist patients with financial barriers, navigators contacted social service (n = 1) and other support system resources such as the American Cancer Society (ACS), Wal-Mart, and utility companies (n = 1) for assistance. They also arranged for financial assistance when resources were available (n = 2).

Quotations from navigators illustrate how navigators assisted patients with financial barriers. One navigator described her attempts to locate a source of funding for a patient’s prepaid cell phone service: “I contacted the American Cancer Society, local television stations, Wal-Mart, and the company that provided the service. I was unable to get any of these places to offer a donation. I was able to secure a private donation from an employee without soliciting. She heard the issue and decided to help out.” Another navigator described her attempt to obtain financial assistance for help with household bills: “I called the social worker so that he could come and speak with her. The social worker called and talked with her.” Another navigator described helping a patient pay for a treatment supplement: “The patient expressed the expense related to Aveeno products which were recommended by their provider. I provided the patient with coupons for Aveeno products and a website to help with the cost of ancillary medical products.”

3.2.3.8. Housing

Two housing-related barriers occurred in patients who needed help with temporary local housing during cancer treatment. Navigators attempted to assist patients with housing barriers by gathering information about available housing resources (n = 1), educating patients about the availability of housing resources (n = 1) and providing a list of hotels that provide discounted rates for patients in treatment (n = 1). One navigator described: “The patient requested information about staying in Hope Lodge on those days that they would be here for treatment. After some investigation, I informed the patient that because they would only need to be here once a week, the Hope Lodge would not be available to them.” Another navigator described: “The patient and family wanted to make lodging accommodations because they would be in town for three days straight, and there was a waiting list at the Hope Lodge. I provided them with a list of hotels in the area that provide discounted rates.” Barrier resolution was defined in this study as completing actions to assist patients with a barrier, regardless of whether the barrier was overcome. These barriers related to housing highlight that sometimes barriers were resolved by navigators in sub-optimal ways from the patient perspective.

3.2.3.9. System of scheduling care

Two system-related barriers occurred in patients who were given inconvenient appointment times. To assist patients with these barriers, navigators sought information from appointment schedulers to try to change the appointment times (n = 2). One navigator described: “The patient needed all appointments to be rescheduled for the afternoon because it is hard for him to get up in the morning so I got that taken care of.” Another navigator said: “The patient’s wife wanted to change appointment dates because they are scheduled to come in on 2 days back to back. Because they live 5h away, this will be a long drive. However, the appointment could not be changed because of the nature of the first visit and cannot be done while the patient receives chemotherapy.”

3.2.3.10. Other barriers

Other barriers included a literacy issue in which patients did not understand medical terminology (n = 1), had difficulty navigating the healthcare facility (n = 1) and needed help with an advance directive (n = 1). A navigator described helping a patient with literacy issue by assisting him to complete paperwork: “I read the surveys out for him and he answered the questions. He completed the 9th grade but does not understand all the medical stuff that the doctors are saying.” Another navigator described helping a patient navigate the hospital by accompanying them to where they needed to go: “The patient and husband were very hungry, but did not feel they could navigate efficiently to the cafeteria and back. I accompanied them to the cafeteria, and afterwards to their car.” A navigator assisted a patient with an advance directive by “referring the patient to the chaplain to help the family fill out the advance directive.”

3.2.3.11. Barriers not identified

No barriers were recorded for the following barrier types listed on the barrier checklist: citizenship concerns, need for language/interpreter, childcare Issues, family/community issues, out of town/country, social/practical support and work schedule conflict.

3.3. Resolution of barriers

For each of the 50 barriers encountered by patients, navigators were asked if they were able to resolve these barriers. Out of the 50 patient barriers, navigators documented that 44 of these barriers were resolved (88%), 4 were not resolved (8%) and did not provide information about barrier resolution for 2 barriers (4%). Three of the four unresolved barriers related to insurance. For a patient who did not know what insurance would cover, the navigator found out that Medicaid would not cover medication, but this ascertainment did not result in the patient obtaining medication coverage. Navigators documented that barriers were not resolved for a patient who needed help with medication copays and a patient whose doctor had filled out short term disability paperwork incorrectly. The fourth documented unresolved barrier was related to a patient’s fear of dying. While the navigator provided emotional support, she did not consider that this support was sufficient to overcome the patient’s fear of dying.

The two barriers for which there was no documentation of whether the barrier was resolved related to communication with medical personnel. One of these barriers was for a patient who needed help bringing in a urine test to retest lab value needed for CT eligibility. The other barrier was for a patient who was having difficulty answering the physician’s questions about their medical history and medications. No additional information is available for these two patients.

While navigators documented that housing barriers were resolved, their notes suggested a lack of availability of robust housing assistance for patients during cancer treatment. For both patients who needed financial assistance with short term housing, neither received housing assistance due to not being in town long enough to be eligible for housing assistance or due to the housing resource being completely booked. Hotel discounts were available for patients which may provide some assistance to patients who need housing during cancer treatment.

3.4. Patient barriers and navigator actions to address barriers

Findings from this study related to patient barriers to CT participation and the actions of navigators to help patients overcome these barriers are discussed below. First, the barriers experienced by patients are discussed, followed by evidence for the navigator’s role in helping patients to overcome these barriers. Next, the study findings related to the intensity of navigation services are discussed. Finally, recommendations are made for coordinating the navigator role in the cancer clinic setting based upon our study findings.

3.4.1. Patient barriers identified

The three most common barriers observed in the current study were: (1) fear about cancer, (2) difficulty communicating with providers and (3) insurance issues. Results from our study were compared with those from two navigation studies conducted among breast and colorectal cancer patients (Carroll, Winters, Purnell, Devine, & Fiscella, 2011; Hendren et al., 2011). Unlike our study, fear was not documented as a major barrier in either of these studies. Consistent with our study results, one of these two comparison studies documented provider communication difficulties as one of the top three barriers to care (Carroll et al., 2011; Hendren et al., 2011) and both of these studies documented insurance issues as one of the top three barriers (Carroll et al., 2011; Hendren et al., 2011). Lack of transportation ranked as the third leading barrier in one of these studies (Carroll et al., 2011) and as the fourth leading barrier in our study. Unlike our study, social support was documented as being one of the top three barriers to care in both of these comparison studies (Carroll et al., 2011; Hendren et al., 2011).

As patient navigation expands into cancer treatment, CTs and post-treatment, it is important to understand the navigator role. Because we tested navigation in a CT setting with late stage cancer patients, we wanted to identify patient barriers in this population. We observed several unique cancer barrier burdens to this population that are not commonly reported in the navigation literature. First, patients commonly suffered from fear/emotional distress and physical symptoms related to late stage disease. Second, patients commonly encountered barriers transitioning from work-related to disability-related income/insurance. Third, patients needed help to coordinate additional tests required for CT eligibility.

The finding of high emotional distress and physical symptoms provides insight into navigation needs for late stage cancer patients. For example, fear was the most frequently reported barrier, some patients were upset their doctor had given up on their CT participation and some patients had difficulty balancing medication compliance with distressing medication side effects. Distress was not cited as a major barrier in two navigation studies of breast and colorectal cancer patients with earlier stage, more curable cancers (Carroll et al., 2011; Hendren et al., 2010). Our study finding that patients need help with symptom distress is supported by the call for formal symptom distress services in cancer care, as described in the landmark Institute of Medicine Report “From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition” (Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life, 2005).

The finding that patients needed intensive support to transition from employer-based insurance to other types of insurance such as short and long term work disability, Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) coverage, Medicaid and Medicare highlights patient difficulties resulting from a fragmented healthcare system. Patients, most of whom started cancer treatment with employer-based insurance, often had to rapidly search for alternative sources of insurance when faced with a disabling cancer diagnosis. The tasks of helping patients fill out paperwork, get medical documentation to support disability insurance/income and appeal denials were some of the more complex and time-consuming services provided by navigators.

4. Discussion

The wide array of patient barriers to CT participation and navigator assistance documented in this study supports the CT navigator role in facilitating quality care as described in the CCM. Navigators’ work was roughly evenly distributed across three types of tasks. First navigators provided case management to enhance treatment compliance. Specifically, navigators facilitating patient adherence to medication regimens, scheduled care visits and additional tests required to establish CT eligibility. As described in the CCM, provision of case management to support treatment compliance is essential for ensuring quality of patient care. Second navigators facilitated emotional support for patients via active listening and referral for emotional support. As described in the CCM, identifying and addressing patients’ emotional needs that could impede cancer treatment is essential to prepare patients for their self-management role in treatment. Third navigators mobilized community and cancer center resources to help patients overcome logistical barriers to care as recommended in the CCM. In this role, navigators linked patients with resources, particularly related to financial assistance, disability determination and insurance coverage.

Ultimately, we wanted to ascertain if navigators were able to assist patients to overcome barriers to CT enrollment and completion. Navigators reported being able to resolve 88% of identified barriers. However, resolution of barriers was defined by the navigation team as having completed the work process for that barrier, not necessarily that the patient’s barrier was overcome. Examples are provided to illustrate this concept. A navigator documented that a housing barrier was resolved by providing a patient with a list of discounted hotels. Another navigator documented that an insurance barrier was resolved by confirming that the patient’s insurance would not cover treatment. Based on how “resolution of barrier” was defined, the navigators accurately recorded the barrier resolution outcome. In future navigation interventions, it will be important to track both whether the patient’s barrier was resolved and to what extent the navigator was able to garner resources and support to assist the patient.

We were ultimately able to assess whether patient barriers were overcome by relying on text data entered by navigators describing their work to assist each patient. Barriers that were not overcome for two or more patients included: (1) insurance issues, (2) lack of temporary housing resources for patients in treatment and (3) assistance with household bills. These data provide valuable program planning data for assessment of unmet patient resource needs.

To inform the staffing needs for future CT navigation interventions, we examined the intensity of navigation services. The number of barriers per patient and time required to navigate each patient varied dramatically. About half of patients had no specific barriers to care, with 10% having 4–7 barriers. The overall median time required to navigate each patient’s barriers was 80min and ranged from 10min to 350min per patient. Unfortunately, the barrier log did not include a variable to enter the time required for the initial patient visit to: (1) view the NCI educational video with the patient, (2) assess and address their questions about CTs and (3) conduct an initial barrier assessment with the patient. Most likely though, this visit would take between 20 and 50min, depending on the amount of interaction between patient and navigator. This extra time would need to be taken into account to estimate overall navigation time.

The finding of varied service intensity among navigated patients supports the idea of offering multiple service levels for CT navigation. Some navigation studies conducted in patients during cancer screening and treatment have implemented “light,” “moderate,” and “intensive” navigation (Ell, Vourlekis, Lee, & Xie, 2007; Ell et al., 2009). This tiered-approach allows program managers to systematically vary the intensity of the navigation program protocol (e.g., contact intervals, duration of navigation consults, type of navigator (lay, social worker, nurse)) according to patient needs. This potential navigation program refinement would support one of the recommendations in the CCM to organize program systems to facilitate efficient and effective care. By building navigation service levels into the IT system, patients with complex service needs could be triaged for more intensive navigation services (Wagner, 1998).

With respect to the intensity of navigation services compared with other CT navigation interventions, in one CT navigation study navigators assisted a rural, medically underserved American Indian population to facilitate cancer treatment and CT participation. A median initial visit time of 40min and follow up visit time of 15min per visit was reported, with a median of 12 visits per patient (Guadagnolo et al., 2011). Compared to our average barrier navigation time of 90min plus an extra 20–50min per patient for viewing and discussing the CT navigation video, these comparison data suggest that the navigation services provided in the study by Guadagnolo et al. were more intensive than in the present study.

There are several possible explanations for why our service intensity was lower than in this comparison study. First, navigated patients in our study may have experienced fewer barriers to care and required less navigation time. This is possible because our navigation program served all patients and not just those identified as poor or medically underserved. Second, our navigators may not have adequately reassessed ongoing barriers and identified new barriers routinely. Navigators were trained and regularly reminded to contact patients at least weekly, but there was no process to monitor that navigators made contact with patients each week. Third, navigators may not have recorded all their activities in the navigation program database. To record navigation encounters and time spent with patients, navigators had to go into each patient record to enter these details each time they performed an activity. Fourth, receipt of intensive ongoing treatment in a multidisciplinary team setting may automatically address issues that in other settings would generate navigator action. The low documented number of barriers and navigation time per patient in our study highlights the need to rigorously: (1) document the intensity of CT navigation services using the barrier checklist and (2) monitor the fidelity in which barriers and navigator actions are recorded in future CT navigation research.

Based on the broad range of patient barriers observed in this pilot study, careful coordination of work activities between the CT navigator and their clinical partners such as clinic nurses, social workers and financial counselors can help to ensure coordination of patient care and avoid duplication of efforts. In fact, one of the recommendations of the CCM is to design tasks and distribute work among team members to ensure efficient delivery of patient care. We identified a number of patient needs that could be addressed by the navigator or by referral to a team member such as a social worker, financial counselor or nurse. For example, a navigator could address a patient’s fear of cancer by active listening or referral to a social worker. Similarly, a navigator could assist with disability paperwork or refer the patient to a financial counselor. Decisions about whether navigators should directly assist patients or refer patients to other service providers may vary by factors such as type of barrier, navigator skills and attributes, patient preferences and available resources. Nonetheless, the potential for overlap between the role of navigators and other clinical team members suggests that careful integration of the navigator role and responsibilities within the clinical team is critical.

In summary, approximately 50% of navigated patients had one or more specific barriers to care. Most barriers were concentrated in a relatively small proportion of patients. This distribution of patient barriers demonstrates that there were “heavy users” and “non-users” of navigation. CT navigators assisted patients with a wide range of barriers related to communication with the clinical team, practical barriers to care and distress.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded by the National Cancer Institute through grant #P30-CA13831302.

References

- American Cancer Society. (2017). Cancer facts & figures 2017. Atlanta, GA, accessed 12/23/19 at https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancerfacts-figures-2017.html. [Google Scholar]

- BRFSS, & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey data. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant DC, Williamson D, Cartmell K, & Jefferson M. (2011). A lay patient navigation training curriculum targeting disparities in cancer clinical trials. Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association, 22(2), 68–75. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23061182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JK, Winters PC, Purnell JQ, Devine K, & Fiscella K. (2011). Do navigators’ estimates of navigation intensity predict navigation time for cancer care? Journal of Cancer Education, 26(4), 761–766. 10.1007/s13187-011-0234-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartmell KB, Bonilha HS, Matson T, Bryant DC, Zapka JG, Bentz TA, et al. (2016). Patient participation in cancer clinical trials: A pilot test of lay navigation. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 3, 86–93. 10.1016/j.conctc.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life. (2005). In Hewitt M, Greenfield S, & Stovall E. (Eds.), From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition, (p. 2). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, & St George DM (2002). Distrust, race, and research. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162(21), 2458–2463. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12437405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denicoff AM, McCaskill-Stevens W, Grubbs SS, Bruinooge SS, Comis RL, Devine P, et al. (2013). The National Cancer Institute-American Society of clinical oncology cancer trial accrual symposium: Summary and recommendations. Journal of Oncology Practice, 9(6), 267–276. 10.1200/JOP.2013.001119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Gadgeel SM, & Simon MS (2006). Predictors of enrollment in lung cancer clinical trials. Cancer, 106(2), 420–425. 10.1002/cncr.21638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant RW, Legedza AT, Marcantonio ER, Freeman MB, & Landon BE (2011). Willingness to participate in clinical trials among African Americans and whites previously exposed to clinical research. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 18(1), 8–19. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21526582. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, & Xie B. (2007). Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: A randomized clinical trial. Preventive Medicine, 44(1), 26–33. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Vourlekis B, Xie B, Nedjat-Haiem FR, Lee PJ, Muderspach L, et al. (2009). Cancer treatment adherence among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer: A randomized controlled trial of patient navigation. Cancer, 115(19), 4606–4615. 10.1002/cncr.24500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, Gibbons MC, et al. (2008). Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer, 112(2), 228–242. 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, Dudley DJ, Fiscella K, Paskett E, et al. (2008). National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: Methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer, 113(12), 3391–3399. 10.1002/cncr.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadegbeku CA, Stillman PK, Huffman MD, Jackson JS, Kusek JW, & Jamerson KA (2008). Factors associated with enrollment of African Americans into a clinical trial: Results from the African American study of kidney disease and hypertension. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 29(6), 837–842. 10.1016/j.cct.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble VN (1997). Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American Journal of Public Health, 87(11), 1773–1778. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9366634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadagnolo BA, Boylan A, Sargent M, Koop D, Brunette D, Kanekar S, et al. (2011). Patient navigation for American Indians undergoing cancer treatment: Utilization and impact on care delivery in a regional healthcare center. Cancer, 117(12), 2754–2761. 10.1002/cncr.25823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendren S, Chin N, Fisher S, Winters P, Griggs J, Mohile S, et al. (2011). Patients’ barriers to receipt of cancer care, and factors associated with needing more assistance from a patient navigator. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103(8), 701–710. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22046847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendren S, Griggs JJ, Epstein RM, Humiston S, Rousseau S, Jean-Pierre P, et al. (2010). Study protocol: A randomized controlled trial of patient navigation-activation to reduce cancer health disparities. BMC Cancer, 10, 551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, et al. (2011). SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2009 (vintage 2009 populations). Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins V, & Fallowfield L. (2000). Reasons for accepting or declining to participate in randomized clinical trials for cancer therapy. British Journal of Cancer, 82(11), 1783–1788. 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klabunde CN, Springer BC, Butler B, White MS, & Atkins J. (1999). Factors influencing enrollment in clinical trials for cancer treatment. Southern Medical Journal, 92(12), 1189–1193. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10624912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara PN Jr., Higdon R, Lim N, Kwan K, Tanaka M, Lau DH, et al. (2001). Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: Identifying potential barriers to enrollment. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 19(6), 1728–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, & Gross CP (2004). Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA, 291(22), 2720–2726. 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (NCI), & American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). (2010). Cancer trials accrual symposium: Science and solutions.. . [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2017). Health, United States, 2016: With chartbook on long-term trends in health. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH (1998). Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice, 1(1), 2–4. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10345255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]