Abstract

Flowers have been used for centuries in decoration and traditional medicine, and as components of dishes. In this study, carotenoids and phenolics from 125 flowers were determined by liquid chromatography (RRLC and UHPLC). After comparing four different extractants, the carotenoids were extracted with acetone: methanol (2:1), which led to a recovery of 83%. The phenolic compounds were extracted with 0.1% acidified methanol. The petals of the edible flowers Renealmia alpinia and Lantana camara showed the highest values of theoretical vitamin A activity expressed as retinol activity equivalents (RAE), i.e., 19.1 and 4.1 RAE/g fresh weight, respectively. The sample with the highest total phenolic contents was Punica granatum orange (146.7 mg/g dry weight). It was concluded that in most cases, flowers with high carotenoid contents did not contain high phenolic content and vice versa. The results of this study can help to develop innovative concepts and products for the industry.

Keywords: antioxidants, edible flowers, functional foods, petals, phytochemicals, retinol activity equivalents

1. Introduction

Flowers have long held an important place in human societies. They have been used for ornamental purposes as well as in diverse dishes, mainly due to their appealing and diverse colors [1]. In addition, flowers have been used in traditional medicine [2]. More specifically, the use of flowers in the diet or as medicine dates back at least to 4000 BC, as documented in the Mesopotamic and Egyptian cultures [3]. Their traditional use in other cultures (Roman, Greek, Chinese, Indian, and European) is also well-known [4].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the study from different points of view of the health-promoting secondary metabolites present in flowers, including carotenoids and phenolics [5,6,7]. Indeed, the study of agronomic practices that can enhance the levels of these compounds in flowers or non-conventional technologies for their extraction are timely topics [8,9]. Carotenoids (carotenes and xanthophylls) are widespread and versatile compounds in nature, where they are important in processes including photosynthesis, the communication within and between species, the protection against oxidizing agents, and the modulation of membrane properties [10]. They are responsible for the red, yellow and orange colors of many flowers [11], which are important for pollination [12]. One of the main differences between carotenoids relative and other bioactive compounds is that some of them can be converted into vitamin A, which is an essential micronutrient. Apart from their key role in combating vitamin A deficiency and as natural food colors, carotenoids are important in health promotion. In fact, these compounds can help to enhance the immune system and reduce the risk of developing some diseases, including cancers (prostate, breast, cervical, ovarian, and colorectal), cardiovascular disease, bone, skin, and eye disorders. Although the possible health-promoting actions of carotenoids are commonly attributed to their antioxidant capacity, they can act through other mechanisms, such as the modulation of signaling pathways (with antioxidant, detoxifying and antiinflamatory effects), the enhancement of intercellular communication, or the protection against light [13]. Due to their versatility, carotenoids have applications not only in the food industry (colorants, ingredients, source of vitamin A), but also in cosmetics [14], feeds [15], pharmaceuticals [16], and even as textile dyes [17].

Phenolic compounds are, like carotenoids, widespread compounds in nature in general and in plants in particular. They can be categorized as extractable or non-extractable. Phenolic acids (benzoic and hydroxycynnamic acids), flavonoids (flavonols, flavones, flavanols, isoflavones, flavanones, and anthocyanidins), estilbenes, extractable proanthocyanidins, and hydrolyzed tannins belong to the first group. Non-extractable proanthocyanidins (or condensed tannins) and hydrolysable phenolics are groups of non-extractable phenolics [18]. These compounds also elicit great interest due to their health-promoting activities, which are usually attributed to antioxidant activity, although there is also evidence that they could exhibit antiviral, anticarcinogenic, antiinflamatory or antimicrobial activities, among others [19].

Depending on their fitness for human consumption, flowers are classified as edible or inedible, which depends on factors including the levels of inherent toxic compounds and/or those of fertilizers, herbicides or pesticides that can be dangerous for human health [20]. Edible flowers are normally used as flavor enhancers, relishes, vegetables, or dish decorations [21]. Common examples are roses (Rosa spp.) in Italy, dandelions (Taraxacum officinale) in Europe, and violets (Viola tricolor) in USA [22]. All in all, there is an increased market demand for edible flowers [1], increasing the need to further study the presence of compounds with nutritional interest in them. In this context, the objective of this study was to evaluate the carotenoids and phenolics of 125 flowers through liquid chromatography,

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Standards

The methanol, hexane, acetone, petroleum ether, dichloromethane, and hydrochloric acid were of analytical grade and were purchased from Labscan (Dublin, Ireland). The HPLC-grade methanol, HPLC-grade acetonitrile, HPLC–grade ethyl acetate, formic acid, sodium chloride, and potassium hydroxide were obtained from Panreac (Barcelona, Spain). The β-Carotene, all-trans-β-apo-8′-carotenal, α-carotene, phytoene, violaxanthin, lutein, β-cryptoxanthin, and lycopene were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany) and the antheraxanthin from DHI (Hørsholm, Denmark). The lutein epoxide, luteoxanthin, zeinoxanthin, 9-cis-antheraxanthin, 9-cis-violaxanthin, 13-cis-violaxanthin, and 9-cis-lutein were obtained as described elsewhere [23,24,25,26,27]. The gallic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, syringic acid, caffeic acid, m-coumaric, p-coumaric, chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, naringin, naringenin, ethyl galate, quercetin, kaempferol, crisin, vanillic acid, and myricetin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Madrid, Spain). The quercitrin was obtained from Extrasynthese (Genay, France). All the aqueous solutions were prepared with purified water in a NANOpure DlamondTM system (Barnsted Inc., Dubuque, IO, USA).

2.2. Plant Materials

The petals of one hundred twenty-five fresh flowers from 52 different families and 102 species were collected from a botanical garden (Real Jardín Botánico de Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain) and local greenhouses in Madrid and Seville (Spain). These places ensure the traceability in the growth of the floral species by providing identification. After measuring the color of the petals, the samples were freeze-dried (Cryodos-80, Telstar, Terrasa, Spain) and the humidity was calculated.

2.3. Color Analysis

The colors were measured using a CM-700d colorimeter (Minollta, Japan). Illuminant D65 and 10° observer were considered as references. The color parameters corresponding to the uniform color space CIELAB were obtained. The categorization of the samples by color (white, yellow, orange, red, pink, lilac and blue) was performed considering clusters of points in the a*b* plane. Thus, the samples were separated into three groups. Group A included white, yellow, and orange flowers, group B contained red and pink flowers, and group C included lilac and blue flowers. The color of some flowers could not be assessed instrumentally because of their small sizes.

2.4. Analysis of Carotenoids

2.4.1. Extraction and Saponification

The micro-extractions were performed under dim light and in triplicate. The best extraction mixture was selected after evaluating different extraction mixtures (hexane: acetone (v/v) (1:1), methanol: acetone: dichloromethane (v/v/v) (1:1:2), acetone: methanol (v/v) (2:1), and ethyl acetate: methanol: petroleum ether (v/v/v) (1:1:1)). For this purpose, the petals of Calendula × hybrid were used. Approximately 20 mg of homogenized freeze-dried powder was mixed with 1 mL of the appropriate solvent mixture and then vortexed, sonicated for 2 min and centrifuged at 14,000× g for 3 min. After recovering the colored fraction, the extraction was repeated with aliquots of 500 μL of the solvent mixture until color exhaustion. The organic colored fractions were combined and evaporated to dryness in a vacuum concentrator at a temperature below 30 °C. Calendula × hybrid is known to possess high amounts of esterified carotenoids, so the extracts were de-esterified by saponification [28]. For this purpose, the dry extracts were re-dissolved in 500 μL of methanolic potassium hydroxide (30%, w/v) and the mixtures were stirred for one hour in a nitrogen atmosphere at 25 °C. Next, 500 μL of dichloromethane and 800 μL of 5% aqueous NaCl (w/v) were added. The samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 14,000× g for 3 min and then the aqueous phase was removed. The carotenoid-containing phase was washed with water until neutrality of the wastewater. The colored phase was evaporated to dryness in a vacuum concentrator at a temperature below 30 °C and stored in a nitrogen atmosphere at −20 °C until the analysis.

The extraction mixture leading to the highest recovery of carotenoids was selected for the extraction of carotenoids from all the samples. All-trans-β-apo-8´-carotenal was used as an internal standard.

2.4.2. Spectrophotometric Analysis

The total carotenoid contents (TCC) of petroleum ether extracts of each flower were quantified by spectrophotometry by considering the absorbance reading at 450 nm and the molar absorptivity value of β-carotene in the solvent (εmol = 2592). The results were reported as μg/g dry weight (DW) [29].

2.4.3. Rapid Resolution Liquid Chromatography (RRLC) Analysis

The dry extracts were re-dissolved in 20 μL of ethyl acetate prior to their analysis by RRLC. The analysis was carried out using the method reported by [30] on an Agilent 1260 system equipped with a diode-array detector and a C18 Poroshell 120 column (2.7 μm, 5 cm × 4.6 mm) (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The injection volume was 5 μL, the flow rate was 1 mL/min, and the temperature of the column was set at 30 °C. A mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile, methanol, and ethyl acetate was used with a linear gradient elution [30]. The chromatograms were monitored at 285, 350, and 450 nm for the quantification of phytoene, phytofluene, and the rest of the carotenoids (lutein epoxide, luteoxanthin, antheraxanthin, violaxanthin, lutein, cis-antheraxanthin, lycopene, zeinoxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, β-carotene, and α-carotene), respectively. UV–Vis spectra were recorded from 250 to 750 nm. The individual carotenoids were identified with their corresponding standards and quantified using external calibration curves made with them whenever possible. The limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) were calculated as three and ten times, respectively; the relative standard deviation of the analytical blank values were calculated from the calibration curve, using Microcal Origin ver. 3.5 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). The LODs and LOQs ranged from 0.002 µg in phytoene to 0.070 µg in lycopene and from 0.007 µg in phytoene to 0.232 µg in lycopene, respectively. The LOD and LOQ were established on the basis of signal to noise (S/N) ratio of 3 and 10, respectively. The samples were analyzed in duplicate with double sample injection. The concentrations were expressed in μg/g DW and the TCC contents were calculated by adding up all the individual carotenoids.

2.5. Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

2.5.1. Extraction

The protocol described by [31] was adapted for the extraction of smaller amounts of samples. Briefly, 1.5 mL of 0.1% acidified methanol was added to approximately 50 mg of freeze-dried petals, and the mixture was vortexed, sonicated for 2 min, and centrifuged at 4190× g for 7 min and at 4 °C; the supernatant was collected and the residue was submitted to the same extraction process twice with only 0.5 mL of the acidified methanol. The combined supernatant was stored at −20 °C until the analysis.

2.5.2. Spectrophotometric Analysis

The extract obtained was used for the determination of the total phenolic content (TPC) using the Folin–Ciocalteu assay, as described by [31], with slight modifications. Briefly, 50 μL of extract, 0.25 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, 0.75 mL of a solution of sodium carbonate (20%), and 3.95 mL of distilled water were mixed and left to stand for 2 h for the reaction to take place. Gallic acid was employed as a calibration standard and the absorbance was read at 765 nm with a Hewlett-Packard UV-vis HP8453 spectrophotometer (Palo Alto, CA, USA). The results were expressed as mg of equivalents of gallic acid per g of dry weight (mg GAE/ g DW) and allowed to define the injection volumes for the quantification by Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC).

2.5.3. Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) Analysis

Prior to the injection, the extracts were concentrated to dryness, re-dissolved in 20 μL of 0.01% formic acid, and centrifuged at 4190× g for 7 min and at 4 °C. The UHPLC method was previously reported by [31]. An Agilent 1290 chromatograph equipped with a diode-array detector (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) set between 220 and 500 nm and an Eclipse Plus C18 column (1.8 um, 2.1 × 5 mm) were used. The column was kept at 30 °C, the injection volumes were in a range between 0.3 and 1.5 μL, the flow rate was 1 mL/min, and a linear gradient was used. Open lab ChemStation software was used for data acquisition and processing. The identification of the phenolic compounds was performed through a comparison of their retention times and UV-vis spectra, within the range 250–750 nm, with those of the available standards [31]. The chromatograms were monitored at 280 for the benzoic acids, hydroxycinnamic acids, flavones, and flavanones, and at 320 nm for the flavonols. Their quantification was carried out using external calibration curves of each of the compounds analyzed. The LODs and LOQs ranged from 0.006 µg in chlorogenic acid to 0.012 µg in p-hydroxybenzoic acid and 0.014 µg in chlorogenic acid to 0.041 µg in p-hydroxybenzoic acid, respectively. The LOD and LOQ were established on the basis of signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios of 3 and 10, respectively. The samples were analyzed in duplicate with double sample injection. The TPC was calculated by adding up all the individual phenolics.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All the experiments were performed in triplicate with double injection, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The mean separation was made via Tukey’s test. Differences were considered statistically significant for p values ≤0.01. The statistical analysis was performed using the STATGRAPHICS Centurion XVII software.

3. Results

3.1. Color Parameters and Other Characteristics

The color parameters, humidity values, and culinary uses of the flowers are presented in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 1.

Mean color parameter values, humidity, and culinary uses (according to Coyago, et al., (2017) [32] and The-Plant-List, (2019) [33]) of white, yellow, and orange flowers.

| Samples | Family | Species | Common Name | Culinary Uses | Humidity (%) | L* | a* | b* | C*ab | hab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White flowers | ||||||||||

| 1 | Araceae | Spathiphyllum montanum Grayum | Peace flower | Non edible | 89.767 ± 0.225 | 57.200 ± 6.263 | −9.210 ± 0.676 | 24.800 ± 1.495 | 26.456 ± 0.709 | 110.333 ± 0.697 |

| 2 | Agavaceae | Chlorophytum comosum (Thunb.) Jacques | Bad mother | Infusion | 99.130 ± 0.701 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 3 | Amaryllidaceae | Agapanthus africanus (L.) Hoffmanns | African lily | Infusion | 76.112 ± 0.306 | 73.517 ± 0.804 | −1.213 ± 0.211 | 4.557 ± 0.872 | 4.727 ± 0.798 | 105.413 ± 3.107 |

| 4 | Apiaceae | Coriandrum sativum L. | Coriander | Salad, garrison | 95.853 ± 0.027 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 5 | Apocynaceae | Nerium oleander L. | Flower laurel | Non edible | 79.493 ± 0.666 | 77.800 ± 3.581 | −2.627 ± 0.316 | 7.637 ± 0.301 | 8.092 ± 0.268 | 109.291 ± 3.447 |

| 6 | Apocynaceae | Trachelospermum jasminoides (Lind.) Len. | Starry jasmine | Infusion | 95.800 ± 0.325 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 7 | Boraginaceae | Heliotropium arborescens L. | Vanilla | Infusion | 86.012 ± 0.152 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 8 | Brassicaceae | Matthiola incana (L.) R. Br. | White violet | Infusion | 99.718 ± 0.525 | 87.123 ± 0.023 | −1.740 ± 0.017 | 21.623 ± 0.323 | 21.693 ± 0.124 | 94.558 ± 0.023 |

| 9 | Campanulaceae | Campanula shetleri Heckard | Green bell | na | 93.548 ± 0.011 | 67.010 ± 0.001 | 0.730 ± 0.001 | 14.050 ± 0.001 | 14.050 ± 0.001 | 87.070 ± 0.000 |

| 10 | Caryophyllaceae | Dianthus chinensis L. | Diantus | Salad, tea | 94.444 ± 0.922 | 80.793 ± 1.819 | −3.137 ± 0.110 | 11.687 ± 2.201 | 12.106 ± 0.156 | 105.231± 2.077 |

| 11 | Caryophyllaceae | Gypsophila paniculata L. | Veil | Infusion | 88.312 ± 1.542 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 12 | Convolvulaceae | Convolvulus pseudoscammonia C. Koch L. | Meadow bell | Infusion | 89.878 ± 0.808 | 83.093 ± 4.473 | −1.800 ± 0.171 | 5.767 ± 1.140 | 6.043 ± 0.120 | 107.501 ± 1.604 |

| 13 | Iridaceae | Gladiolus communis L. | Gladiolus | Salad, garrison | 79.592 ± 0.349 | 67.010 ± 0.001 | 0.730 ± 0.001 | 14.051 ± 0.008 | 14.069 ± 0.002 | 87.070 ± 0.001 |

| 14 | Lamiaceae | Mentha suaveolens Ehrh. | Mentha suaveolens | Infusion | 79.771 ± 0.902 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 15 | Magnoliaceae | Magnolia grandiflora L. | Magnolia | Tea | 82.151 ± 0.272 | 83.093 ± 4.473 | −1.800 ± 0.171 | 5.767 ± 0.140 | 6.043 ± 0.410 | 107.501 ± 0.764 |

| 16 | Oleaceae | Jasminum sambac (L.) Aiton | Jasmine of Arabia | Salad, tea | 84.826 ± 0.104 | 83.987 ± 2.450 | −2.927 ± 0.401 | 16.497 ± 0.901 | 16.757 ± 0.918 | 100.059 ± 0.129 |

| 17 | Orchidaceae | Phalaenopsis aphrodite Rchb. f. | Orchid | na | 98.172 ± 0.063 | 70.063 ± 1.670 | 10.030 ± 2.044 | −7.103 ± 1.079 | 12.297 ± 2.201 | 325.161 ± 1.368 |

| 18 | Plumbaginaceae | Plumbago auriculata Lam. | Celestine | Infusion | 26.895 ± 0.872 | 54.340 ± 1.806 | 1.530 ± 0.041 | −16.017 ± 0.154 | 16.208 ± 0.157 | 275.041 ± 0.289 |

| 19 | Rosaceae | Fragaria × Duchesne ex Rozier | Strawberry | na | 94.215 ± 0.579 | 67.010 ± 0.001 | 0.730 ± 0.020 | 14.050 ± 0.001 | 14.069 ± 0.031 | 87.070 ± 0.011 |

| 20 | Rosaceae | Rosa hybrid Vill. | Rose | Salad, desserts | 79.739 ± 0.888 | 86.353 ± 0.915 | 0.030 ± 0.041 | 14.207 ± 0.059 | 14.207 ± 0.024 | 89.924 ± 0.005 |

| 21 | Solanaceae | Capsicum annuum L. | Pepper | na | 98.960 ± 0.921 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 22 | Solanaceae | Solanum laxum Sprengel | False jasmine | na | 85.197 ± 1.508 | 50.783 ± 2.100 | 11.903 ± 1.050 | 8.620 ± 0.219 | 14.798 ± 1.203 | 35.636 ± 0.832 |

| 23 | Verbenaceae | Aloysia citriodora Palau | Cedrón | Tea | 98.118 ± 0.847 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 24 | Verbenaceae | Lantana camara L. | Lantana | Tea | 86.986 ± 0.183 | 64.770 ± 0.143 | 2.703 ± 0.246 | 17.780 ± 1.362 | 17.991 ± 1.326 | 81.447 ± 1.244 |

| Yellow flowers | ||||||||||

| 25 | Araceae | Aglaonema commutatum Schott | Aglaonema | Non edible | 91.958 ± 0.900 | 66.330 ± 1.411 | −0.627 ± 0.055 | 28.877 ± 1.864 | 28.884 ± 0.186 | 91.205 ± 0.180 |

| 26 | Asteraceae | Anthemis tinctoria L. | Golden Daisy | Colorant | 78.726 ± 0.172 | 60.770 ± 2.463 | 21.140 ± 0.654 | 87.357 ± 2.326 | 89.878 ± 0.740 | 76.436 ± 0.139 |

| 27 | Asteraceae | Dahlia coccinea Cav. | Dahlia | Salad | 87.788 ± 0.184 | 61.363 ± 0.719 | 2.133 ± 0.201 | 66.667 ± 0.540 | 66.713 ± 0.281 | 88.181 ± 0.133 |

| 28 | Asteraceae | Dahlia pinnata Cav. | Dahlia | Salad | 74.519 ± 0.001 | 67.290 ± 0.646 | 16.523 ± 0.018 | 75.780 ± 0.546 | 77.561 ± 0.572 | 77.739 ± 0.060 |

| 29 | Brassicaceae | Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC. | Rucula | Salad | 87.218 ± 0.528 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 30 | Cannabaceae | Cannabis sativa L. | Cannabis | Non edible | 76.200± 0.914 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 31 | Celastraceae | Euonymus japonicus Thunb. | Burning bush | Colorant | 92.000 ± 1.028 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 32 | Fabaceae | Sophora japonica L. | Acacia Japan | Infusion | 73.629 ± 0.384 | 79.180 ± 1.871 | −6.573 ± 0.116 | 22.023 ± 0.733 | 22.984 ± 0.107 | 106.592 ± 0.582 |

| 33 | Fabaceae | Senna papillosa H.S. Irwin & Barneby | Senna | Non edible | 73.823 ± 0.326 | 58.420 ± 4.265 | 11.060 ± 2.265 | 38.370 ± 4.099 | 40.000 ± 5.911 | 74.380 ± 4.294 |

| 34 | Juglandaceae | Pterocarya stenoptera C. DC. | Chinese fresno | Non edible | 84.572 ± 0.611 | 73.000 ± 1.279 | −5.970 ± 0.214 | 32.910 ± 1.255 | 33.455 ± 1.245 | 100.342 ± 0.283 |

| 35 | Lamiaceae | Ocimum basilicum L. | Basil | Salad, tea | 94.680 ± 1.525 | 80.893 ± 3.409 | −7.227 ± 0.657 | 32.187 ± 1.419 | 32.990 ± 0.712 | 102.602 ± 0.691 |

| 36 | Malvaceae | Gossypium arboreum L. | Cotton | Non edible | 81.410 ± 0.114 | 80.873 ± 3.412 | −7.243 ± 0.713 | 32.201 ± 1.403 | 33.120 ± 0.725 | 102.612 ± 0.743 |

| 37 | Plantaginaceae | Plantago major L. | Plantain | Infusion | 85.714 ± 0.200 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 38 | Polygonaceae | Fallopia aubertii (L.Henry) Holub | Gabriela falloppio | na | 92.411 ± 0.332 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 39 | Portulacaceae | Portulaca oleracea L. | Purslane | Salad | 98.092 ± 0.661 | 71.643 ± 0.965 | 4.887 ± 0.240 | 29.533 ± 0.397 | 29.906 ± 0.401 | 80.624 ± 0.311 |

| 40 | Rubiaceae | Gardenia jasminoides J. Ellis | Gardenia | Colorant | 82.213 ± 0.283 | 84.253 ± 3.833 | 3.453 ± 0.116 | 46.923 ± 0.470 | 47.050 ± 0.161 | 85.833 ± 0.179 |

| 41 | Solanaceae | Solanum lycopersicum L. | Tomato | na | 87.255 ± 0.261 | 77.200 ± 1.001 | −4.500 ± 0.121 | 22.034 ± 0.704 | 23.036 ± 0.111 | 106.603 ± 0.612 |

| 42 | Verbenaceae | Lantana camara L. | Lantana | Tea | 88.122 ± 0.706 | 50.570 ± 0.875 | 18.403 ± 0.431 | 48.440 ± 0.128 | 51.823 ± 0.135 | 69.101 ± 1.018 |

| Orange flowers | ||||||||||

| 43 | Acanthaceae | Justicia aurea Schltdl. | na | 94.207 ± 0.184 | 68.817 ± 1.399 | 4.123 ± 0.456 | 88.640 ± 3.326 | 88.736 ± 3.433 | 87.386 ± 0.191 | |

| 44 | Bignoniaceae | Tecoma capensis (Thunb.) Lindl. | Cape honeysuckle | Infusion | 72.225 ± 0.506 | 53.233 ± 2.266 | 40.633 ± 2.053 | 34.833 ± 2.048 | 53.572 ± 0.299 | 40.635 ± 3.084 |

| 45 | Gesneriaceae | Drymonia affinis (Mansf.) Wiehler | Drymonia | na | 73.209 ± 0.172 | 49.510 ± 1.247 | 24.983 ± 0.582 | 32.520 ± 0.963 | 41.010 ± 1.063 | 52.490 ± 0.519 |

| 46 | Gesneriaceae | Drymonia brochidodroma Wiehler | Drymonia | na | 91.041 ± 0.703 | 46.622 ± 1.207 | 25.043 ± 0.604 | 32.511 ± 1.000 | 41.002 ± 1.333 | 52.512 ± 1.302 |

| 47 | Lythraceae | Punica granatum L. | Pomegranate | Infusion | 69.105 ± 0.437 | 43.093 ± 2.765 | 47.340 ± 0.356 | 36.738 ± 0.217 | 59.743 ± 0.133 | 38.153 ± 0.375 |

| 48 | Zigniberaceae | Renealmia alpinia (Rottb.) Maas | Honeyy bract | Spice | 89.126 ± 1.333 | 52.111 ± 0.224 | 42.175 ± 0.126 | 35.101 ± 0.243 | 54.872 ± 0.302 | 39.825 ± 2.126 |

na, not available.

Table 2.

Mean color parameter values, humidity, and culinary uses (according to Coyago et al., (2017) [32] and The-Plant-List, (2019) [33]) of red and pink flowers.

| Samples | Family | Species | Common Name | Culinary Use | Humidity (%) | L* | a* | b* | C*ab | hab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red flowers | ||||||||||

| 49 | Acanthaceae | Aphelandra squarrosa Nees | Zebra plant | na | 73.202 ± 3.184 | 30.847 ± 1.259 | 49.437 ± 0.942 | 32.257 ± 0.541 | 59.030 ± 1.028 | 33.142 ± 0.339 |

| 50 | Amaranthaceae | Celosia argentea L. | Cockscomb | na | 71.704 ± 0.126 | 36.837 ± 2.878 | 23.600 ± 2.946 | −2.833 ± 0.342 | 23.817 ± 2.999 | 352.621 ± 0.629 |

| 51 | Apocynaceae | Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don | Vinca rosea | Non-edible | 96.519 ± 0.015 | 46.001 ± 0.012 | 49.863 ± 0.285 | −7.123 ± 0.081 | 50.370 ± 0.270 | 351.865 ± 0.137 |

| 52 | Apocynaceae | Nerium oleander L. | Flower laurel | Non-edible | 89.739 ± 3.621 | 67.077 ± 1.693 | 19.380 ± 1.427 | 3.250 ± 0.658 | 19.810 ± 1.583 | 10.429 ± 1.409 |

| 53 | Araceae | Anthuriumandraeanum Linden ex | Anus | Non-edible | 94.096 ± 1.525 | 50.630 ± 0.404 | 32.917 ± 1.165 | 11.283 ± 1.585 | 34.814 ± 1.226 | 18.895 ± 2.255 |

| 54 | Balsaminaceae | Impatiens balsamina L. | Joy of home | Salad, desserts | 91.049 ± 0.211 | 41.543 ± 2.466 | 47.893 ± 4.686 | 23.887 ± 3.367 | 53.528 ± 4.758 | 26.449 ± 1.238 |

| 55 | Balsaminaceae | Impatiens walleriana Hook. F. | My dear | Salad, desserts | 85.202 ± 0.984 | 50.287 ± 2.228 | 57.220 ± 2.573 | 19.490 ± 2.556 | 60.463 ± 2.626 | 18.770 ± 1.556 |

| 56 | Begoniaceae | Begonia cavaleriei H. Lév. | Begonia | na | 76.748 ± 0.253 | 54.793 ± 4.344 | 19.460 ± 2.899 | 12.267 ± 0.498 | 23.311 ± 2.381 | 33.935 ± 3.613 |

| 57 | Begoniaceae | Begonia cucullata Willd. | Sugar flower | Salad, desserts | 59.290 ± 0.127 | 37.443 ± 0.873 | 36.870 ± 2.315 | 15.157 ± 2.171 | 39.931 ± 2.942 | 21.995 ± 1.802 |

| 58 | Begoniaceae | Begonia × tuberhybrida Voss | Begonia | Salad, desserts | 99.736 ± 0.834 | 32.067 ± 1.391 | 53.383 ± 2.036 | 33.483 ± 1.014 | 63.018 ± 2.134 | 32.121 ± 0.720 |

| 59 | Caryophyllaceae | Dianthus caryophyllus L. | Carmination | Fruit salad | 95.775 ± 0.106 | 39.863 ± 4.495 | 50.847 ± 3.674 | 21.403 ± 3.633 | 55.206 ± 3.751 | 22.762 ± 2.616 |

| 60 | Ericaceae | Rhododendron simsii Planch. | Azalea | Non-edible | 41.527 ± 2.572 | 41.543 ± 2.466 | 47.893 ± 3.468 | 23.887 ± 3.367 | 53.528 ± 1.265 | 26.449 ± 1.238 |

| 61 | Escalloniaceae | Escallonia rubra Pers. | Escalloniacea | na | 82.780 ± 0.427 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 62 | Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia milii Des Moul. | Crown of christ | Non-edible | 98.893 ± 0.165 | 40.683 ± 2.678 | 32.693 ± 2.356 | 13.493 ± 1.152 | 35.384 ± 1.765 | 22.483 ± 2.048 |

| 63 | Fabaceae | Brownea macrophylla Linden | Panama flame tree | na | 87.209 ± 0.217 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 64 | Geraniaceae | Pelargonium peltatum (L.) L´Hér. | Gitanilla | na | 96.390 ± 0.028 | 14.157 ± 0.337 | 17.037 ± 0.491 | 1.823 ± 0.161 | 17.135 ± 0.472 | 6.124 ± 0.694 |

| 65 | Geraniaceae | Pelargonium x hortorum H. Bailey | Geranium | Salad, desserts | 86.548 ± 0.281 | 30.353 ± 2.168 | 46.593 ± 2.431 | 27.520 ± 2.095 | 54.119 ± 2.408 | 30.563 ± 0.945 |

| 66 | Lamiaceae | Salvia splendens Sellow ex Schult. | Red sage | Garrison | 72.018 ± 0.164 | 38.813 ± 2.189 | 24.673 ± 1.401 | 21.833 ± 0.132 | 33.424 ± 1.121 | 42.183 ± 1.443 |

| 67 | Malvaceae | Malvaviscus arboreus Cav. | Marshmallow | Infusion | 86.152 ± 0.909 | 40.990 ± 1.676 | 47.580 ± 2.984 | 25.150 ± 3.289 | 53.833 ± 3.015 | 27.789 ± 1.699 |

| 68 | Onagraceae | Fuchsia magellanica Lam. | Fuchsia | Tea | 81.264 ± 0.009 | 44.210 ± 2.187 | 34.773 ± 0.917 | 3.037 ± 0.703 | 34.980 ± 1.053 | 5.963 ± 0.856 |

| 69 | Rosaceae | Rosa hybrid Vill. | Rose | Salad, desserts | 78.682 ± 0.325 | 28.440 ± 1.591 | 46.303 ± 0.280 | 17.863 ± 1.013 | 49.635 ± 0.356 | 21.100 ± 1.027 |

| 70 | Papaveraceae | Papaver rhoeas L. | Wheat poppy | Garrison | 72.111 ± 0.263 | 40.683 ± 2.678 | 32.693 ± 3.566 | 13.493 ± 1.520 | 35.384 ± 3.653 | 22.483 ± 2.048 |

| 71 | Rubiaceae | Warszewiczia coccinea Klotzsch | Chaconia | Tea | 83.000 ± 1.381 | 34.253 ± 1.363 | 46.237 ± 2.908 | 12.033 ± 0.526 | 47.777 ± 2.944 | 14.607 ± 0.316 |

| 72 | Scrophulariaceae | Antirrhinum majus L. | Dragon mouth | Salad | 94.967 ± 0.288 | 24.040 ± 1.152 | 18.920 ± 0.593 | 15.050 ± 1.283 | 24.201 ± 0.367 | 38.489 ± 3.222 |

| 73 | Scrophulariaceae | Russelia equisetiformis Schltdl. & | Ruselia | Infusion | 89.257 ± 0.129 | 41.543 ± 2.466 | 47.893 ± 4.686 | 23.887 ± 3.367 | 53.528 ± 4.765 | 26.449 ± 1.238 |

| 74 | Solanaceae | Petunia hybrida Vilm. | Petunia | Salad, desserts | 90.986 ± 5.425 | 34.253 ± 1.363 | 46.237 ± 2.908 | 12.033 ± 0.526 | 47.777 ± 2.944 | 14.607 ± 0.316 |

| 75 | Verbenaceae | Lantana camara L. | Lantana | Tea | 83.774 ± 2.182 | 33.210 ± 0.439 | 38.610 ± 2.384 | 30.187 ± 0.335 | 49.124 ± 0.282 | 38.024 ± 0.478 |

| 76 | Verbenaceae | Verbena × hybrid Groenland | Verbena | Salad, garrison | 85.436 ± 0.023 | 26.913 ± 0.674 | 36.787 ± 3.852 | 14.537 ± 0.872 | 39.560 ± 3.868 | 21.641 ± 1.176 |

| Pink flowers | ||||||||||

| 77 | Amaranthaceae | Celosia argentea L. | Cockscomb | na | 72.421 ± 0.184 | 19.443 ± 2.286 | 34.023 ± 1.479 | 4.120 ± 1.085 | 34.286 ± 1.538 | 6.948 ± 2.004 |

| 78 | Apocynaceae | Nerium oleander L. | Flower laurel | Non-edible | 82.058 ± 0.327 | 58.847 ± 3.279 | 29.247 ± 4.101 | −2.743 ± 0.145 | 29.387 ± 4.139 | 354.364 ± 0.711 |

| 79 | Begoniaceae | Begonia argentea Linden | Begonia | na | 91.547 ± 1.522 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 80 | Bromeliaceae | Guzmania hybrid | Guzmania | na | 89.651 ± 0.001 | 46.660 ± 0.233 | 15.770 ± 0.885 | 9.340 ± 0.524 | 18.343 ± 0.488 | 30.703 ± 2.838 |

| 81 | Caryophyllaceae | Dianthus caryophyllus L. | Carmination | Fruit salad | 84.678 ± 0.325 | 43.320 ± 1.501 | 34.690 ± 0.436 | 3.987 ± 0.127 | 34.918 ± 0.447 | 6.558 ± 0.126 |

| 82 | Caryophyllaceae | Saponaria officinalis L. | Soap flower | Non-edible | 81.110 ± 0.202 | 68.560 ± 0.291 | 3.883 ± 0.946 | −3.333 ± 0.818 | 5.133 ± 0.760 | 318.436 ± 5.235 |

| 83 | Ericaceae | Rhododendron simsii Planch. | Azalea indica | Non-edible | 74.579 ± 0.299 | 82.190 ± 1.669 | 5.943 ± 0.421 | 8.860 ± 0.739 | 10.686 ± 0.396 | 56.081 ± 4.033 |

| 84 | Fabaceae | Trifolium cernuum Brot. | Four leaf clover | Salad, tea | 81.411 ± 0.303 | 50.783 ± 1.421 | 11.903 ± 0.850 | 8.620 ± 1.397 | 14.798 ± 0.203 | 35.636 ± 5.324 |

| 85 | Gentianaceae | Eustoma grandiflorum G. Don | Eustoma | na | 92.072 ± 0.099 | 66.407 ± 4.493 | 4.067 ± 0.668 | 5.233 ± 0.486 | 6.630 ± 0.792 | 52.333 ± 2.000 |

| 86 | Geraniaceae | Pelargonium domesticum Bailey | Real geranium | Salad, desserts | 85.698 ± 0.785 | 15.783 ± 1.532 | 16.793 ± 1.561 | 1.757 ± 0.875 | 17.147 ± 1.675 | 12.053 ± 1.4800 |

| 87 | Geraniaceae | Pelargonium × hortorum Bailey | Geranium | Salad, desserts | 75.523 ± 0.185 | 52.563 ± 0.198 | 29.107 ± 0.233 | 2.177 ± 0.437 | 29.200 ± 0.234 | 4.016 ± 0.172 |

| 88 | Hydrangeaceae | Hydrangea petiolaris S. & Zucc. | Hydrangea | Infusion | 74.361 ± 0.725 | 58.440 ± 1.439 | 24.807 ± 1.436 | −3.767 ± 0.372 | 25.092 ± 1.463 | 351.369 ± 0.558 |

| 89 | Lythraceae | Cuphea hyssopifolia Kunth | False breccia | Infusion | 95.948 ± 0.811 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 90 | Lythraceae | Lagerstroemia indica L. | Jupiter tree | Tea | 87.561 ± 0.347 | 47.777 ± 0.128 | 27.050 ± 0.622 | −4.687 ± 0.063 | 27.456 ± 0.622 | 350.173 ± 0.302 |

| 91 | Malvaceae | Gossypium arboreum L. | Cotton | Non-edible | 82.733 ± 5.421 | 51.887 ± 5.484 | 10.090 ± 0.617 | 9.913 ± 0.588 | 14.162 ± 0.078 | 44.522 ± 3.431 |

| 92 | Nyctaginaceae | Mirabilis jalapa L. | Night Dondiego | Colorant | 85.593 ± 0.206 | 53.100 ± 1.815 | 15.547 ± 0.213 | 7.133 ± 0.445 | 17.175 ± 0.143 | 24.759 ± 1.630 |

| 93 | Orchidaceae | Phalaenopsis aphrodite Rchb. F. | Orchid | na | 92.271 ± 0.358 | 50.783 ± 2.100 | 11.903 ± 0.805 | 8.620 ± 1.321 | 14.798 ± 0.120 | 35.636 ± 3.024 |

| 94 | Portulacaceae | Portulaca oleracea L. | Purslane | Salad | 85.529 ± 3.674 | 35.780 ± 0.344 | 18.983 ± 0.144 | 27.170 ± 0.265 | 33.145 ± 0.136 | 55.085 ± 0.466 |

| 95 | Rosaceae | Rosa hybrid | Rose | Salad, desserts | 89.769 ± 0.105 | 47.763 ± 3.951 | 55.923 ± 5.390 | 19.007 ± 0.679 | 59.088 ± 5.045 | 18.886 ± 1.936 |

| 96 | Verbenaceae | Verbena × hybrid G. & Rümpler | Verbena | Salad, garrison | 84.040 ± 0.037 | 41.467 ± 3.153 | 19.337 ± 0.140 | 2.330 ± 0.437 | 19.486 ± 0.153 | 6.793 ± 1.117 |

na, not available.

Table 3.

Mean color parameter values, humidity, and culinary uses (according to Coyago et al., (2017) [32] and The-Plant-List, (2019) [33]) of lilac and blue flowers.

| Samples | Family | Species | Common name | Culinary use | Humidity (%) | L* | a* | b* | C*ab | hab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lilac flowers | ||||||||||

| 97 | Amaryllidaceae | Allium schoenoprasum L. | Chives | Salad, garrison | 74.820 ± 0.222 | 20.333 ± 3.502 | 2.915 ± 0.126 | −0.147 ± 0.001 | 2.983 ± 0.119 | 359.606 ± 0.012 |

| 98 | Apocynaceae | Catharanthus roseus L. | Vinca rosea | Non-edible | 87.648 ± 1.291 | 54.233 ± 2.573 | 30.217 ± 2.145 | −18.707 ± 1.692 | 35.553 ± 2.139 | 328.223 ± 1.971 |

| 99 | Asteraceae | Centaurea seridis L. | Spiny broom | na | 93.516 ± 0.883 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 100 | Asteraceae | Cichorium intybus L. | Chicory of Brussels | Salad, tea | 98.378 ± 0.283 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 101 | Asteraceae | Osteospermun fruticosum Norl. | Cape margarita | Tea | 82.523 ± 0.317 | 47.673 ± 2.091 | 29.153 ± 0.459 | −15.303 ± 0.110 | 32.927 ± 0.379 | 332.286 ± 0.488 |

| 102 | Brassicaceae | Alyssum montanum L. | Garlic herb | Infusion | 81.159 ± 0.395 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 103 | Campanulaceae | Campanula carpatica Jacq. | Little bell | na | 85.496 ± 0.152 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 104 | Geraniaceae | Pelargonium domesticum Bailey | Real geranium | Salad, desserts | 92.894 ± 0.800 | 58.660 ± 4.038 | 25.157 ± 1.518 | −12.213 ± 0.319 | 31.101 ± 1.325 | 335.566 ± 1.634 |

| 105 | Geraniaceae | Pelargonium × hortorum Bailey | Common geranium | Salad, desserts | 83.186 ± 0.001 | 38.290 ± 2.736 | 53.403 ± 1.538 | −11.497 ± 0.678 | 54.633 ± 1.355 | 167.827 ± 1.051 |

| 106 | Lamiaceae | Mentha ×piperita L. | Peppermint | Salad, garrison | 94.503 ± 0.063 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 107 | Lamiaceae | Ocimum basilicum L. | Basil | Salad, tea | 89.677 ± 1.222 | 41.423 ± 1.120 | 6.436 ± 0.311 | −4.879 ± 0.921 | 8.124 ± 0.343 | 322.701 ± 4.206 |

| 108 | Malvaceae | Hibiscus syriacus L. | Rose of Syria | Salad, tea | 70.778 ± 0.747 | 53.743 ± 0.282 | 18.460 ± 1.136 | −12.697 ± 0.616 | 22.407 ± 1.202 | 325.356 ± 0.302 |

| 109 | Nyctaginaceae | Bougainvillea spectabilis Willd. | Bougainvillea | Infusion | 86.967 ± 1.558 | 50.753 ± 0.741 | 6.963 ± 1.002 | 1.790 ± 0.310 | 7.309 ± 0.911 | 16.291 ± 3.413 |

| 110 | Plumbaginaceae | Limonium sinuatum (L.) Miller | Always alive | Additive | 91.656 ± 0.184 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 111 | Polygonaceae | Fallopia aubertii (L. Henry) Holub | Gabriela falloppio | na | 99.350 ± 1.200 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 112 | Solanaceae | Petunia hybrida Vilm. | Petunia | Salad, desserts | 86.068 ± 0.315 | 69.300 ± 0.566 | 9.533 ± 1.230 | −4.087 ± 1.287 | 10.390 ± 0.346 | 337.496 ± 1.963 |

| 113 | Solanaceae | Solanum rantonnetti Carrière | Blue flower solano | Infusion | 83.018 ± 0.126 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 114 | Verbenaceae | Verbena × hybrid G. & Rümpler | Verbena | Salad, garrison | 84.238 ± 1.282 | 41.367 ± 1.086 | 6.397 ± 0.303 | −4.913 ± 0.949 | 8.081 ± 0.379 | 322.707 ± 4.156 |

| 115 | Verbenaceae | Vitex agnus-castus L. | Chilli pepper | Infusion | 82.257 ± 0.666 | 33.417 ± 1.246 | 9.887 ± 1.320 | −14.997 ± 2.539 | 17.967 ± 2.844 | 303.628 ± 1.419 |

| Blue flowers | ||||||||||

| 116 | Amaryllidaceae | Agapanthus africanus Hoffmanns | African lily | Infusion | 82.523 ± 5.401 | 57.173 ± 2.173 | 4.543 ± 0.162 | −15.723 ± 1.030 | 16.367 ± 0.233 | 286.099 ± 0.508 |

| 117 | Convolvulaceae | Convolvulus althaeoides L. | Bell of the virgin | Non-edible | 89.100 ± 0.172 | 61.887 ± 1.980 | 12.333 ± 1.512 | −3.312 ± 0.001 | 12.709 ± 1.520 | 345.099 ± 1.657 |

| 118 | Gesneriaceae | Saintpaulia ionantha Wendland | African violet | Salad | 89.577 ± 0.065 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 119 | Goodeniaceae | Scaevola aemula R. Bronw | Flower fan | Infusion | 93.812 ± 0.273 | 36.913 ± 1.770 | 8.497 ± 0.619 | 0.539 ± 0.016 | 8.431 ± 0.623 | 3.380 ± 0.521 |

| 120 | Lamiaceae | Agastachefoeniculum Kuntze | Anise hyssop | Salad, desserts | 79.731 ± 0.288 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 121 | Lamiaceae | Lavandula angustifolia Mill. | Lavender | Infusion | 88.511 ± 0.173 | 37.582 ± 1.607 | 8.8977 ± 0.639 | −12.101 ± 0.812 | 15.026 ± 0.922 | 306.212 ± 0.144 |

| 122 | Lamiaceae | Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Rosemary | Garrison, desserts | 89.483 ± 0.211 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 123 | Passiofloraceae | Passiflora × belotti | Flower of the passion | Tea | 97.826 ± 0.742 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 124 | Polygonaceae | Polygala vulgaris L. | Common sparrow | Infusion | 88.391 ± 0.364 | 49.780 ± 1.113 | 17.963 ± 1.319 | −10.847 ± 2.043 | 21.006 ± 1.320 | 329.058 ± 3.214 |

| 125 | Solanaceae | Petunia × hybrida Vilm. | Petunia | Salad, desserts | 83.425 ± 0.779 | 23.210 ± 1.458 | 23.027 ± 1.216 | −25.717 ± 1.197 | 34.519 ± 1.703 | 311.811 ± 0.177 |

na, not available.

3.2. Carotenoids

Selection of the Extraction Solvents

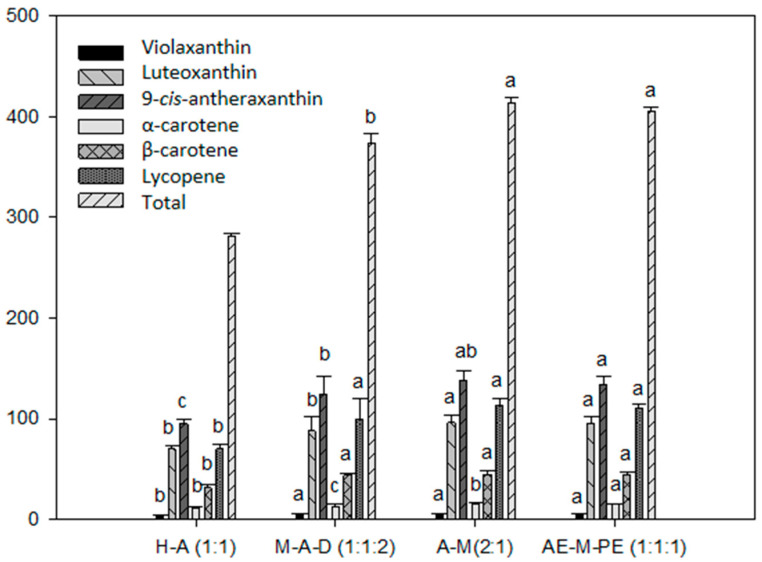

Four different extraction solvents were tested for the extraction of carotenoids in Calendula × hybrid (Figure 1). Acetone: methanol (v/v) (2:1) and ethyl acetate: methanol: petroleum ether (v/v/v) (1:1:1) showed the highest carotenoid extraction yields and there was no statistically significant difference between the two mixtures. The recovery of carotenoids obtained with this mixture, using all-trans-β-apo-8′-carotenal as internal standard, was 83%.

Figure 1.

Carotenoid content recoveries (mg/100 g DW) after extraction of Calendula × hybrid using four different extraction solvents. H-A (1:1), hexane: acetone (v/v) (1:1); M-A-D (1:1:2), methanol: acetone: dichloromethane (v/v/v) (1:1:2); A-M (2:1), acetone: methanol (v/v) (2:1); AE-M-PE (1:1:1), ethyl acetate: methanol: petroleum ether (v/v/v) (1:1:1). Different letters among bars of the same carotenoid indicate significant differences by ANOVA test (p < 0.01).

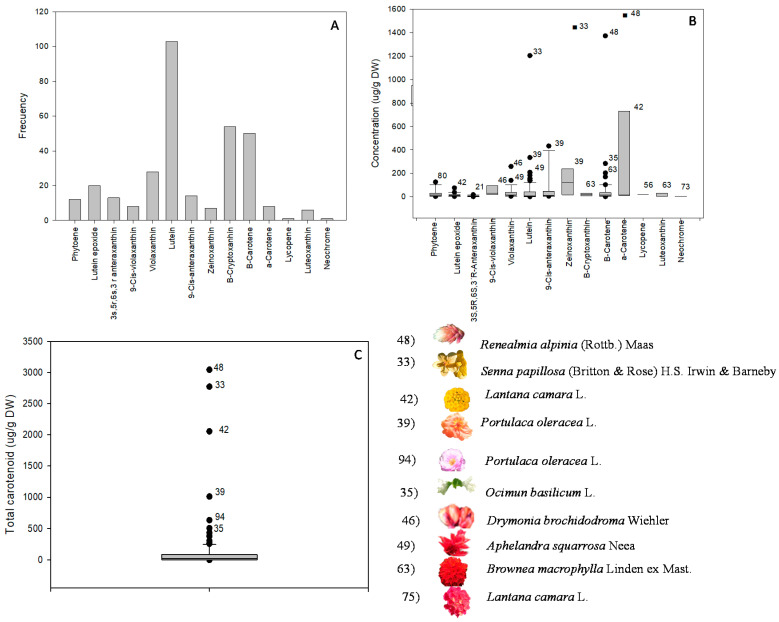

In addition, quantitative data on individuals and TCC, assessed by liquid chromatography, are presented in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. An example of the resulting chromatogram is presented in Figure 2, and the frequency, mean contents, and standard deviations of carotenoids and major sources are presented in Figure 3, sections A, B, and C.

Table 4.

Carotenoid contents (μg/g dry weight) of white, yellow, and orange flowers and retinol activity equivalents.

| Species | Phytoene | Lutein Epoxide | Luteoxanthin | Antheraxanthin | 9-Cis-Violaxanthin | Violaxanthin | Lutein | 9-Cis-Anteraxanthin | Zeinoxanthin | β-Carotene | α-Carotene | TOTAL | Retinol Activity Equivalents FW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White flowers | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | S. montanum | 47.724 ± 0.633 | 96.839 ± 1.304 | 32.235 ± 2.525 | 82.001 ± 0.789 | 258.863 ± 0.843 | 0.629 ± 0.123 | |||||||

| 2 | C. comosum | 14.816 ± 0.003 | 79.101 ± 2.045 | 93.917 ± 1.700 | 0.059 ± 0.018 | |||||||||

| 3 | A. africanus | 3.648 ± 0.460 | 4.478 ± 0.373 | 8.125 ± 0.069 | ||||||||||

| 4 | C. sativum | 141.747 ± 0.501 | 22.734 ± 2.594 | 103.121 ±1.176 | 267.601 ± 1.238 | 0.352 ± 0.023 | ||||||||

| 5 | N. oleander | 2.748 ± 0.3122 | 2.748 ± 0.3122 | |||||||||||

| 6 | T.jasminoides | 3.581 ± 0.527 | 3.581 ± 0.527 | |||||||||||

| 7 | H. arborescens | 26.995 ± 2.084 | 3.745 ± 0.251 | 30.740 ± 0.195 | 0.044 ± 0.015 | |||||||||

| 8 | M. incana | 2.523 ± 0.411 | 2.523 ± 0.411 | |||||||||||

| 9 | C. shetleri | 11.357 ± 0.434 | 11.675 ± 0.446 | 23.033 ± 0.068 | ||||||||||

| 10 | D. chinensis | nd | ||||||||||||

| 11 | G. paniculata | 6.649 ± 0.855 | 9.124 ± 0.930 | 18.801 ± 0.232 | 33.854 ± 0.3168 | 0.980 ± 0.029 | ||||||||

| 12 | C. scammonia | 5.989 ± 0.770 | 5.929 ± 0.235 | 11.918 ± 0.077 | ||||||||||

| 13 | G. communis | 3.146 ± 0.107 | 3.146 ± 0.107 | |||||||||||

| 14 | M. suaveolens | 38.523 ± 2.621 | 6.901 ± 0.415 | 21.677 ± 1.936 | 71.278 ± 0.439 | 11.611 ± 0.001 | 149.990 ± 0.687 | 0.195 ± 0.001 | ||||||

| 15 | M. grandiflora | 20.359 ± 1.259 | 20.359 ± 1.259 | |||||||||||

| 16 | J. sambac | 4.877 ± 0.136 | 4.877 ± 0.136 | |||||||||||

| 17 | P. aphrodite | 1.901 ± 0.411 | 6.822 ± 0.330 | 8.273 ± 0.125 | 0.063 ± 0.023 | |||||||||

| 18 | P. auriculata | nd | ||||||||||||

| 19 | F. × ananassa | nd | ||||||||||||

| 20 | Rosa hybrid | 16.801 ± 0.001 | 6.418 ± 0.546 | 9.970 ± 0.702 | 33.249 ± 0.153 | |||||||||

| 21 | C. annuum | 20.435 ± 0.642 | 18.313 ± 0.576 | 16.199 ±0.509 | 76.460 ± 0.468 | 8.272 ± 0.161 | 139.680 ± 0.618 | 0.141 ± 0.066 | ||||||

| 22 | S. laxum | 10.427 ± 0.360 | 3.734 ± 0.101 | 4.730 ± 0.163 | 6.682 ± 0.944 | 25.572 ± 0.845 | 0.028 ± 0.015 | |||||||

| 23 | A. citriodora | 1.741 ± 0.264 | 1.741 ± 0.264 | |||||||||||

| 24 | L. camara* | 44.352 ± 1.586 | 6.914 ± 0.238 | 13.515 ± 0.321 | 64.782 ± 0.420 | 0.148 ± 0.011 | ||||||||

| *13-Cis-violaxanthin (43.503 ± 0.722); 9-Cis-lutein (140.712 ± 0.586); Zeaxanthin (147.8 ± 2.502); β-Cryptoxanthin (361.422 ± 7.638); α-Cis-anteraxanthin (232.215 ± 12.126). | ||||||||||||||

| Yellow flowers | ||||||||||||||

| 25 | A. commutatu | 10.424 ± 0.162 | 13.040 ± 0.203 | 43.188 ± 0.462 | 12.028 ± 0.245 | 78.680 ± 0.402 | 0.085 ± 0.024 | |||||||

| 26 | A. tinctoria | 9.338 ± 0.574 | 10.240 ± 0.630 | 19.578 ± 0.093 | ||||||||||

| 27 | D. coccinea | nd | ||||||||||||

| 28 | D. pinnata | 19.521 ± 0.613 | 20.492 ± 0.644 | 40.013 ± 0.097 | 0.208 ± 0.044 | |||||||||

| 29 | D. tenuifolia | 17.464 ± 0.549 | 33.122 ± 3.642 | 41.066 ± 1.291 | 13.755 ± 0.432 | 105.408 ± 0.455 | 0.021 ± 0.021 | |||||||

| 30 | C. sativa | 16.949 ± 0.585 | 2.878 ± 0.099 | 19.826 ± 0.057 | 0.057 ± 0.035 | |||||||||

| 31 | E. japonicus | 31.441 ± 0.946 | 31.441 ± 0.946 | |||||||||||

| 32 | S. japonica | 38.878 ± 1.341 | 100.347 ± 3.461 | 139.225 ± 0.369 | 2.208 ± 0.010 | |||||||||

| 33 | S. papillosa | 86.001 ± 0.021 | 1204.010 ± 0.062 | 1311.876 ± 0.052 | 170.316 ± 0.001 | 2772.202 ± 0.056 | 3.477 ± 0.027 | |||||||

| 34 | P. stenoptera | 3.623 ± 0.803 | 1.130 ± 0.226 | 3.991 ± 0.593 | 23.966 ± 1.709 | 32.709 ± 0.278 | ||||||||

| 35 | O. basilicum | 7.293 ± 0.106 | 7.992 ± 0.124 | 205.176 ± 1.318 | 284.137 ± 1.924 | 504.597 ± 2.895 | 1.255 ± 0.030 | |||||||

| 36 | G. arboreum | 5.150 ± 0.362 | 5.150 ± 0.362 | |||||||||||

| 37 | P. major | 31.395 ± 0.489 | 136.768 ± 3.277 | 168.162 ± 0.314 | ||||||||||

| 38 | F. aubertii | 3.725 ± 0.394 | 3.725 ± 0.394 | |||||||||||

| 39 | P. oleracea | 334.85 ± 8.972 | 433.409 ± 0.182 | 239.780 ± 3.720 | 4.357 ± 0.685 | 1012.431 ± 7.860 | 0.051 ± 0.041 | |||||||

| 40 | G. jasminoides | 6.895 ± 0.150 | 6.895 ± 0.150 | |||||||||||

| 41 | S. lycopersicum | 31.885 ± 0.609 | 20.207 ± 1.752 | 35.960 ± 1.748 | 88.052 ± 0.738 | |||||||||

| 42 | L. camaraa | 12.744 ± 0.648 | 75.829 ± 2.937 | 92.465 ± 0.823 | 43.500 ± 0.307 | 63.792 ± 3.421 | 54.906 ± 2.379 | 50.828 ± 0.461 | 731.514 ± 7.631 | 2056.065 ± 7.148 | 4.796 ± 1.027 | |||

| Orange flowers | ||||||||||||||

| 43 | J. aurea | 47.880 ± 0.071 | 47.880 ± 0.071 | |||||||||||

| 44 | T. capensis | 6.595 ± 0.751 | 1.844 ± 0.260 | 6.320 ± 0.406 | 6.621 ± 0.426 | 37.646 ± 0.241 | 0.188 ± 0.015 | |||||||

| 45 | D. affinis | 22.283 ± 0.003 | 30.403 ± 0.013 | 43.261 ± 0.001 | 16.277 ± 0.034 | 112.225 ± 0.026 | 0.364 ± 0.007 | |||||||

| 46 | D. brochidodroma | 97.582 ± 0.011 | 258.828 ± 0.078 | 76.733 ± 0.022 | 433.144 ± 0.080 | |||||||||

| 47 | P. granatum | 24.981 ± 0.309 | 8.891 ± 0.279 | 33.872 ± 0.260 | 0.229 ± 0.075 | |||||||||

| 48 | R. alpinia | 220.643 ± 0.06 | 1372.181 ± 0.001 | 1451.916 ± 0.003 | 3044.739 ± 2.120 | 19.058 ± 0.019 | ||||||||

nd, not detectable.

Table 5.

Carotenoid contents (μg/g dry weight) of red and pink flowers and retinol activity equivalents.

| Species | Reaction | Phytoene | Lutein Epoxide | Antheraxanthin | 9-Cis-Violaxanthin | Violaxanthin | Lutein | 9-Cis-Anteraxanthin | Zeinoxanthin | β-Cryptoxanthin | β-Carotene | α-Carotene | Total | Others Carotenoids | Retinol Activity Equivalents FW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red flowers | ||||||||||||||||

| 49 | A. squarrosa | S | 140.001 ± 0.001 | 208.963 ± 0.012 | 32.298 ± 0.001 | 381.262 ± 0.003 | ||||||||||

| 50 | C. argentea | S | 2.518 ± 0.556 | 8.205 ± 0.637 | 8.452 ± 0.893 | 2.900 ± 0.286 | 22.074 ± 0.151 | 0.068 ± 0.084 | ||||||||

| 51 | C. roseus | 3.691 ± 0.721 | 3.691 ± 0.721 | |||||||||||||

| 52 | N.oleander | 3.431 ± 0.439 | 3.431 ± 0.439 | |||||||||||||

| 53 | A. andraeanum | 11.101 ± 0.109 | 3.041 ± 0.490 | 14.142 ± 0.122 | 0.015 ± 0.070 | |||||||||||

| 54 | I. balsamina | 2.890 ± 0.209 | 2.890 ± 0.209 | |||||||||||||

| 55 | I. walleriana | 2.908 ± 0.196 | 2.908 ± 0.196 | |||||||||||||

| 56 | B. cavaleriei | S | 3.689 ± 0.119 | 21.277 ± 0.092 | Lycopene (17.588 ± 0.567) |

0.072 ± 0.042 | ||||||||||

| 57 | B. andraeanum | S | 3.950 ± 0.114 | 3.950 ± 0.114 | ||||||||||||

| 58 | B. × tuberhybrida | S | 8.719 ± 0.910 | 8.719 ± 0.910 | ||||||||||||

| 59 | D. caryophyllus | 15.862 ± 0.408 | 15.862 ± 0.408 | |||||||||||||

| 60 | R. simsii | S | 79.036 ± 0.063 | 79.036 ± 0.063 | ||||||||||||

| 61 | E. rubra | 5.163 ± 0.224 | 5.163 ± 0.224 | |||||||||||||

| 62 | E. milii | 7.357 ± 0.103 | 7.357 ± 0.103 | |||||||||||||

| 63 | B. macrophylla | S | 17.165 ± 0.023 | 33.391 ± 0.072 | 203.433 ± 0.001 | 377.425 ± 0.009 | Luteoxanthin (98.725 ± 0.001); 9-Cis-β-cryptoxanthin (24.704 ± 0.011) |

2.385 ± 0.001 | ||||||||

| 64 | P. peltatum | 3.280 ± 0.108 | 3.280 ± 0.108 | |||||||||||||

| 65 | P. × hortorum | 3.521 ± 0.491 | 3.521 ± 0.491 | |||||||||||||

| 66 | S. splendens | S | 5.548 ± 0.234 | 5.548 ± 0.234 | ||||||||||||

| 67 | M. arboreus | S | 140.300 ± 0.004 | 7.074 ± 0.295 | 147.374 ± 0.023 | |||||||||||

| 68 | F. magellanica | 5.269 ± 0.537 | 6.497 ± 0.001 | 11.766 ± 0.045 | ||||||||||||

| 69 | Rosa hybrid | 6.800 ± 0.303 | 6.800 ± 0.303 | 0.122 ± 0.016 | ||||||||||||

| 70 | P. rhoeas | S | 66.753 ± 0.823 | 66.753 ± 0.823 | ||||||||||||

| 71 | W. coccinea | S | 97.236 ± 0.001 | 97.236 ± 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| 72 | A. majus | nd | ||||||||||||||

| 73 | R. equisetiformis | S | 9.144 ± 0.732 | 140.300 ± 0.001 | 4.252 ± 0.340 | 4.085 ± 0.106 | 161.976 ± 0.164 | Neochrome (4.252 ± 0.340) |

0.055 ± 0.001 | |||||||

| 74 | Petunia × hybrid | 6.019 ± 0.111 | 6.019 ± 0.111 | |||||||||||||

| 75 | L. camara | 33.946 ± 1.469 | 25.415 ± 2.768 | 46.326 ± 1.267 | 36.794 ± 0.959 | 25.694 ± 0.315 | 55.198 ± 1.267 | 1.542 ± 0.460 | 5.587 ± 0.287 | 304.721 ± 0.183 | 0.021 ± 0.000 | |||||

| 76 | Verbena × hybrid | 30.303 ± 0.525 | 11.906 ± 1.700 | 58.361 ± 0.004 | 9.303 ± 0.002 | 26.972 ± 0.011 | 106.289 ± 0.017 | 15-Cis-violaxanthin (11.711 ± 1.600); 9-Cis-lutein (32.001 ±1.229) |

0.328 ± 0.001 | |||||||

| Pink flowers | ||||||||||||||||

| 77 | C. argentea | 15.714 ± 0.421 | 100.672± 2.836 | 116.324± 0.303 | ||||||||||||

| 78 | N. oleander | 0.972 ± 0.003 | 0.972 ± 0.003 | |||||||||||||

| 79 | B. argentea | S | 182.793± 0.734 | 43.165 ± 0.181 | 15.310 ± 0.194 | 241.268± 0.594 | 0.803 ± 0.003 | |||||||||

| 80 | Guzmania hybrid | 126.450 ± 0.852 | 2.912 ± 0.129 | 7.763 ± 0.107 | 13.867 ± 0.782 | 150.992± 0.859 | 0.119 ± 0.006 | |||||||||

| 81 | D. caryophyllus | 1.662 ± 0.004 | 1.662 ± 0.004 | |||||||||||||

| 82 | S. officinalis | 9.544 ± 0.984 | 9.544 ± 0.984 | |||||||||||||

| 83 | R.simsii | 0.718 ± 0.074 | 0.718 ± 0.074 | |||||||||||||

| 84 | T. cernuum | 2.776 ± 0.304 | 2.041 ± 0.022 | 4.817 ± 0.041 | ||||||||||||

| 85 | E. grandiflorum | 0.966 ± 0.039 | 0.966 ± 0.039 | |||||||||||||

| 86 | P. domesticum | 2.078 ± 0.120 | 2.078 ± 0.120 | |||||||||||||

| 87 | P. × hortorum | nd | ||||||||||||||

| 88 | H. petiolaris | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 7.3 ± 0.0 | |||||||||||||

| 89 | C. hyssopifolia | 19.298 ± 1.331 | 60.944 ± 1.834 | 11.306 ± 0.780 | 61.105 ± 0.421 | 157.029 ± 0.638 | Luteoxanthin (4.375 ± 0.132) |

0.209 ± 0.004 | ||||||||

| 90 | L. indica | 4.385 ± 0.308 | 8.476 ± 0.595 | 12.861 ± 0.069 | 0.088 ± 0.000 | |||||||||||

| 91 | G. arboreum | 0.700 ± 0.001 | 0.700 ± 0.001 | |||||||||||||

| 92 | M. jalapa | S | 4.147 ± 0.328 | 4.147 ± 0.328 | ||||||||||||

| 93 | P. aphrodite | 6.858 ± 0.510 | 8.376 ± 0.802 | 8.742 ± 0.837 | 20.361 ± 1.252 | 44.338 ± 0.284 | 0.131 ± 0.002 | |||||||||

| 94 | P. oleracea | 156.999 ± 3.163 | 355.241 ± 3.700 | 120.763 ± 5.221 | 632.974 ± 6.136 | |||||||||||

| 95 | Rosa hybrid | 6.718 ± 0.846 | 9.657 ± 0.102 | 14.962 ± 0.188 | 5.379 ± 0.678 | 27.610 ± 0.205 | 64.238 ± 0.531 | 0.235 ± 0.002 | ||||||||

| 96 | Verbena × hybrid | 10.142 ± 1.038 | 2.544 ± 0.048 | 12.685 ± 0.127 | 0.034 ± 0.001 | |||||||||||

S, saponified; nd, not detectable.

Table 6.

Carotenoid contents (μg/g dry weight) of lilac and blue flowers and retinol activity equivalents.

| Species | Reaction | Phytoene | Lutein Epoxide | Luteoxanthin | Antheraxanthin | 9-Cis-Violaxanthin | Violaxanthin | Lutein | 9-Cis-Anteraxanthin | Zeinoxanthin | β-Cryptoxanthin | β-Carotene | α-Carotene | Total | Retinol Activity Equivalents FW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lilac flowers | ||||||||||||||||

| 97 | A. schoenoprasum | 14.146 ± 1.277 | 10.807 ± 0.976 | 36.072± 3.256 | 9.041 ± 0.081 | 70.066 ± 0.421 | 0.190 ± 0.001 | |||||||||

| 98 | C. roseus | S | nd | |||||||||||||

| 99 | C. seridis | nd | ||||||||||||||

| 100 | C. intybus | 2.096 ± 0.105 | 2.096 ± 0.105 | |||||||||||||

| 101 | O. fruticosum | 3.892 ± 0.815 | 3.892 ± 0.815 | |||||||||||||

| 102 | A. montanum | S | 10.610 ± 0.974 | 45.785± 0.420 | 24.954 ± 0.222 | 81.349 ± 0.575 | 0.100 ± 0.001 | |||||||||

| 103 | C. carpatica | 6.957 ± 0.012 | 8.320 ± 0.001 | 20.323 ± 0.007 | 35.600 ± 0.064 | 0.020 ± 0.000 | ||||||||||

| 104 | Pelargonium × domesticum | 0.739 ± 0.071 | 0.739 ± 0.071 | |||||||||||||

| 105 | Pelargonium × hortorum | S | nd | |||||||||||||

| 106 | Mentha × piperita | S | 23.427 ± 0.415 | 5.907 ± 0.113 | 9.493 ± 0.182 | 70.580± 0.664 | 38.600 ± 0.141 | 148.008 ± 0.943 | 0.177 ± 0.002 | |||||||

| 107 | O. basilicum | 16.781 ± 1.022 | 5.105 ± 1.026 | 7.611 ± 0.100 | 37.663 ± 2.341 | 22.492 ± 0.864 | 88.873 ± 0.611 | 0.294 ± 0.007 | ||||||||

| 108 | H. syriacus | S | 3.869 ± 0.481 | 3.869 ± 0.481 | ||||||||||||

| 109 | B. spectabili | S | 12.183 ± 1.010 | 33.282 ± 0.820 | 45.465 ± 0.141 | |||||||||||

| 110 | L. sinuatum | 3.231 ± 0.152 | 3.231 ± 0.0152 | 0.240 ± 0.004 | ||||||||||||

| 111 | F. aubertii | 5.407 ± 0.107 | 5.407 ± 0.107 | |||||||||||||

| 112 | Petunia × hybrida | 9.113 ± 0.126 | 9.113 ± 0.126 | |||||||||||||

| 113 | S. rantonnetti | 8.307 ± 0.775 | 7.797 ± 0.538 | 7.299 ± 0.503 | 34.080 ± 2.350 | 21.228 ± 1.464 | 78.711 ± 0.433 | 0.301 ± 0.001 | ||||||||

| 114 | Verbena × hybrid | 25.007 ± 1.137 | 48.224 ± 2.200 | 6.914 ± 0.426 | 22.666 ± 1.051 | 102.689 ± 0.424 | 0.297 ± 0.005 | |||||||||

| 115 | V. agnus- castus | 4.909 ± 0.103 | 2.582 ± 0.153 | 7.491 ± 0.092 | 0.038 ± 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Blue flowers | ||||||||||||||||

| 116 | A. africanus | 3.648 ± 0.460 | 4.478 ± 0.373 | 8.125 ± 0.069 | ||||||||||||

| 117 | C. althaeoides | nd | ||||||||||||||

| 118 | S. ionantha | 1.911 ± 0.145 | 1.911 ± 0.145 | |||||||||||||

| 119 | S. aemula | 18.220 ± 1.227 | 3.139 ± 0.152 | 4.112 ± 0.277 | 16.117 ± 1.085 | 41.588 ± 0.228 | ||||||||||

| 120 | A. foeniculum | 47.885 ± 3.833 | 35.877 ± 2.872 | 83.763 ± 0.516 | 0.607 ± 0.003 | |||||||||||

| 121 | L. angustifolia | S | 17.478 ± 0.822 | 19.190 ± 0.893 | 4.540 ± 0.373 | 19.347 ± 0.224 | 59.506 ± 1.492 | 12.258 ± 0.841 | 132.320± 0.513 | 0.722 ± 0.001 | ||||||

| 122 | R. officinalis | S | 14.888 ± 1.021 | 14.888± 1.021 | ||||||||||||

| 123 | Passiflora × belotti | 4.818 ± 0.454 | 7.122 ± 0.580 | 21.554 ± 2.032 | 15.638 ± 0.216 | 49.133± 0.436 | 0.196 ± 0.003 | |||||||||

| 124 | P. vulgaris | 1.736 ± 0.412 | 1.736 ± 0.412 | |||||||||||||

| 125 | Petunia × hybrida | 23.061± 1.631 | 16.645 ± 0.021 | 39.707± 0.136 | 0.230 ± 0.000 | |||||||||||

S, saponified; nd, not detectable.

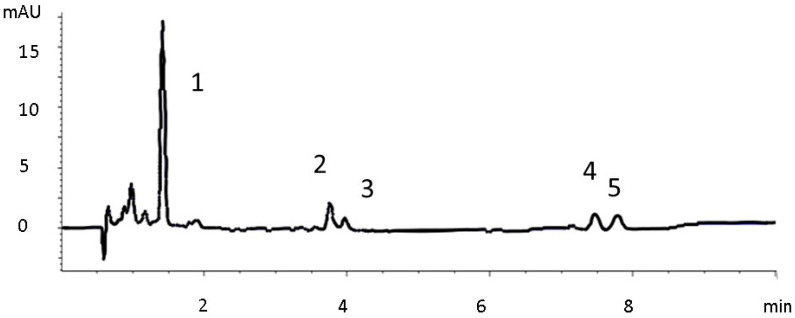

Figure 2.

Chromatogram of Lavandula angustifolia at 450 nm (C18 column). 1. Lutein; 2. Zeinoxanthin; 3. β-Cryptoxanthin; 4. α-Carotene; 5. β-Carotene.

Figure 3.

Frequency, mean contents, and standard deviations of carotenoids and major sources. Frequency (A), mean contents of individual carotenoids (B), total carotenoid content (C), and list of species with high concentrations of carotenoids. Number within the figures represent the sample under study.

3.3. Phenolic Compounds

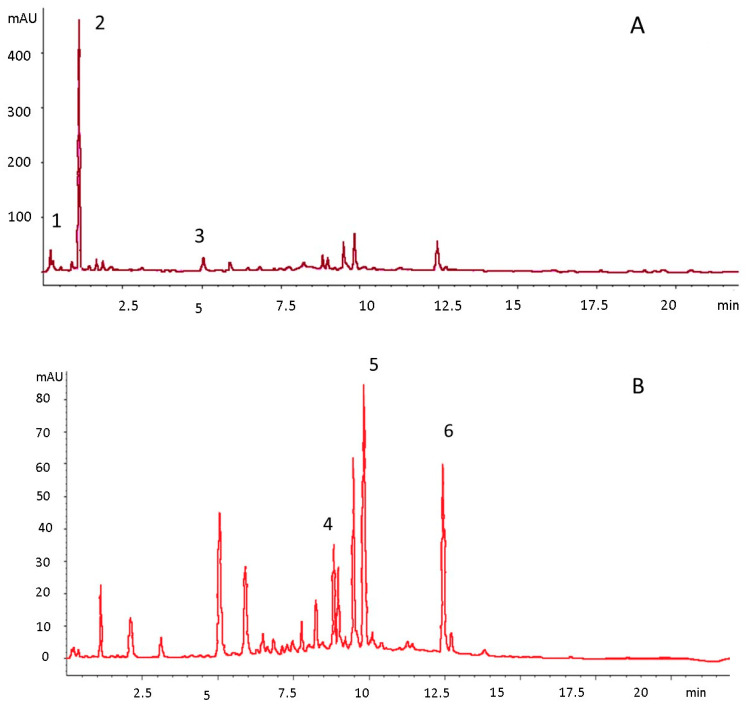

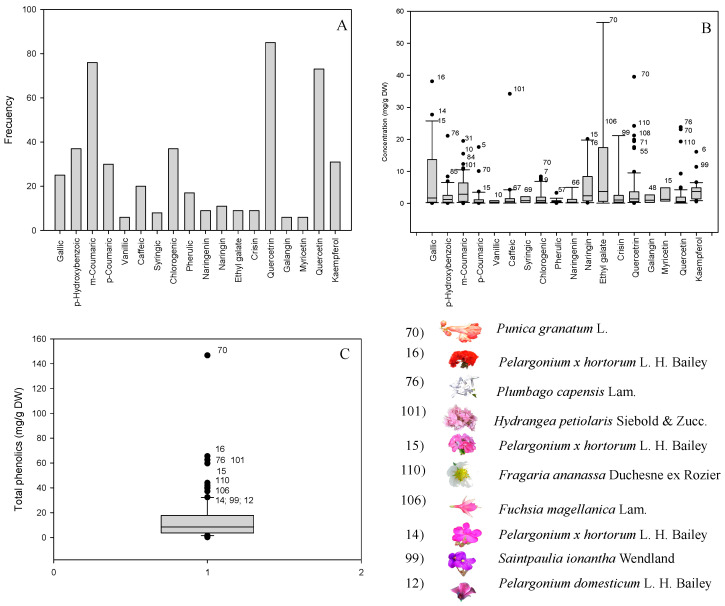

The quantitative data on individuals and TPC assessed by chromatographic analysis are presented in Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9. In addition, an example of the resulting chromatogram is presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5 sections A, B, and C show the frequency, mean contents, and standard deviations of the phenolics and major sources.

Table 7.

Phenolic compound contents (mg/g dry weight) of white, yellow, and orange flowers.

| Species | Gallic | p-Hydroxybe. | m-Coumaric | p-Coumaric | Vanillic | Caffeic | Syringic | Chlorogenic | Ferulic | Naringin | Crisin | Quercitrin | Myricetin | Quercetin | Kaempferol | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White flowers | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | S. montanum | nd | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | C. comosum | 7.868 ± 0.718 | 2.802 ± 0.053 | 4.061 ± 0.092 | 0.475 ± 0.039 | 4.249 ± 0.038 | 21.110 ± 1.393 | ||||||||||

| 3 | A. africanus | 8.648 ± 0.934 | 2.032 ± 0.081 | 1.444 ± 0.249 | 0.890 ± 0.022 | 13.013 ± 1.287 | |||||||||||

| 4 | C. sativum | 0.242 ± 0.023 | 0.560 ± 0.008 | 1.185 ± 0.042 | 0.372 ± 0.020 | 0.089 ± 0.001 | 2.448 ± 0.094 | ||||||||||

| 5 | N. oleander | 0.103 ± 0.003 | 2.999 ± 0.031 | 3.091 ± 0.052 | 0.443 ± 0.020 | 0.215 ± 0.014 | 3.428 ± 0.372 | 3.339 ± 0.029 | 13.618 ± 0.521 | ||||||||

| 6 | T. jasminoides | 1.719 ± 0.014 | 0.398 ± 0.085 | 0.990 ± 0.001 | 0.323 ± 0.0036 | 0.802 ± 0.154 | 4.132 ± 0.028 | ||||||||||

| 7 | H. arborescens | 0.476 ± 0.013 | 0.456 ± 0.001 | 0.227 ± 0.020 | 1.158 ± 0.163 | ||||||||||||

| 8 | M. incana | 5.710 ± 1.153 | 5.710 ± 1.153 | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | C. shetleri | 2.329 ± 0.079 | 0.218 ± 0.020 | 1.338 ± 0.107 | 0.248 ± 0.004 | 4.133 ± 0.092 | |||||||||||

| 10 | D. chinensis | 5.655 ± 0.601 | 3.870 ± 0.253 | 9.525 ± 0.016 | |||||||||||||

| 11 | G. paniculata | 4.277 ± 0.467 | 17.930 ± 2.552 | 22.208 ± 0.132 | |||||||||||||

| 12 | C.s scammonia | 0.844 ± 0.053 | 1.611 ± 0.274 | 0.146 ± 0.004 | 1.472 ± 0.242 | 0.438 ± 0.090 | 4.884 ± 0.053 | 9.598 ± 0.073 | |||||||||

| 13 | G. communis | 0.688 ± 0.085 | 0.123 ± 0.009 | 0.577 ± 0.010 | 0.587 ± 0.009 | 2.390 ± 0.129 | |||||||||||

| 14 | M. suaveolens | 0.601 ± 0.035 | 1.337 ± 0.028 | 1.247 ± 0.013 | 3.863 ± 0.704 | ||||||||||||

| 15 | M. grandiflora | 0.168 ± 0.001 | 0.575 ± 0.035 | 0.744 ± 0.036 | |||||||||||||

| 16 | J. sambac | 5.913 ± 0.217 | 0.290 ± 0.003 | 0.146 ± 0.005 | 2.211 ± 0.040 | 0.261 ± 0.016 | 9.219 ± 0.028 | ||||||||||

| 17 | P. aphrodite | 1.063 ± 0.054 | 0.201 ± 0.010 | 6.565 ± 0.214 | 7.954 ± 0.886 | ||||||||||||

| 18 | P. auriculata | 19.895 ± 2.118 | 17.592 ± 0.561 | 22.356 ± 0.618 | 59.843 ± 0.252 | ||||||||||||

| 19 | F. × ananassa | 0.472 ± 0.011 | 24.183 ± 0.625 | 16.983 ± 0.321 | 41.628 ± 0.127 | ||||||||||||

| 20 | Rosa hybrid | 4.033 ± 0.199 | 1.302 ± 0.029 | 1.499 ± 0.351 | 12.501 ± 1.098 | ||||||||||||

| 21 | C. annuum | 0.358 ± 0.068 | 0.737 ± 0.106 | 1.372 ± 0.069 | 1.162 ± 0.044 | 0.545 ± 0.007 | 4.978 ± 0.057 | 0.547 ± 0.010 | 9.699 ± 0.0877 | ||||||||

| 22 | S. laxum | 0.213 ± 0.076 | 0.301 ± 0.001 | 0.099 ± 0.001 | 0.953 ± 0.052 | 1.266 ± 0.132 | |||||||||||

| 23 | A. citriodora | 1.944 ± 0.036 | 2.869 ± 0.028 | 3.748 ± 0.068 | 4.401 ± 0048 | 15.643 ± 0.001 | |||||||||||

| 24 | L. camara | 7.556 ± 0.026 | 3.402 ± 0.020 | 2.170 ± 0.115 | 5.922 ± 0.173 | 19.051 ± 0.033 | |||||||||||

| Yellow flowers | |||||||||||||||||

| 25 | A. commutatum | 0.084 ± 0.022 | 0.220 ± 0.009 | 0.121 ± 0.034 | 0.162 ± 0.032 | 0.588 ± 0.097 | |||||||||||

| 26 | A. tinctoria | 2.345 ± 0.013 | 6.767 ± 0.228 | 0.495 ± 0.041 | 1.309 ± 0.013 | 0.152 ± 0.004 | 11.066 ± 0.615 | ||||||||||

| 27 | D. coccinea | 6.902 ± 0.027 | 4.738 ± 0.227 | 1.325 ± 0.303 | 0.721 ± 0.078 | 3.570 ± 0.2488 | 15.733 ± 0.0774 | ||||||||||

| 28 | D. pinnata | 0.340 ± 0.022 | 1.402 ± 0.081 | 1.325 ± 0.130 | 0.721 ± 0.078 | 0.597 ± 0.037 | 0.824 ± 0.139 | 4.475 ± 0.542 | 9.685 ± 0.012 | ||||||||

| 29 | D. tenuifolia | 2.186 ± 0.006 | 3.075 ± 0.438 | 2.439 ± 0.388 | 7.701 ± 0.083 | ||||||||||||

| 30 | C. sativa | 0.239 ± 0.014 | 1.719 ± 0.130 | 0.233 ± 0.010 | 2.192 ± 0.155 | ||||||||||||

| 31 | E. japonicus | 0.245 ± 0.090 | 0.190 ± 0.001 | 0.225 ± 0.031 | 0.649 ± 0.010 | 0.251 ± 0.006 | 1.858 ± 0.0218 | ||||||||||

| 32 | S. japonica | 0.813 ± 0.039 | 0.179 ± 0.007 | 0.409 ± 0.018 | 0.427 ± 0.006 | 3.395 ± 0.146 | 0.972 ± 0.035 | 2.669 ± 0.347 | 9.167 ± 0.742 | ||||||||

| 33 | S. papillosa | nd | |||||||||||||||

| 34 | P. stenoptera | 12.605 ± 1.193 | 1.220 ± 0.019 | 1.529 ± 0.134 | 0.505 ± 0.068 | 0.131 ± 0.027 | 18.078 ± 0.119 | ||||||||||

| 35 | O. basilicum | 0.207 ± 0.013 | 0.328 ± 0.032 | 0.640 ± 0.0050 | |||||||||||||

| 36 | G. arboreum | 0.4360 ± 0.025 | 0.308 ± 0.002 | 5.621 ± 0.766 | 1.507 ± 0.029 | 7.872 ± 0.011 | |||||||||||

| 37 | P. major | 0.751 ± 0.051 | 0.856 ± 0.058 | 21.226 ± 1.503 | 22.833 ± 0.161 | ||||||||||||

| 38 | F. aubertii | 0.806 ± 0.028 | 0.091 ± 0.006 | 0.191 ± 0.024 | 0.399 ± 0.018 | 0.136 ± 0.018 | 1.725 ± 0.089 | ||||||||||

| 39 | P. oleracea | 1.302 ± 0.101 | 2.425 ± 0.001 | 0.125 ± 0.007 | 0.457 ± 0.049 | 4.276 ± 0.053 | |||||||||||

| 40 | G. jasminoides | 0.600 ± 0.026 | 0.316 ± 0.001 | 0.407 ± 0.023 | 0.311 ± 0.004 | 1.956 ± 0.025 | |||||||||||

| 41 | S. lycopersicum | 1.849 ± 0.297 | 0.435 ± 0.009 | 0.620 ± 0.072 | 0.691 ± 0.059 | 3.395 ± 0.436 | |||||||||||

| 42 | L. camara | 1.034 ± 0.107 | 2.665 ± 0.043 | 1.175 ± 0.122 | 2.412 ± 0.003 | 2.126 ± 0.040 | 1.634 ± 0.011 | 10.862 ± 0.072 | |||||||||

| Orange flowers | |||||||||||||||||

| 43 | J. aurea | nd | |||||||||||||||

| 44 | T. capensis | 0.350 ± 0.070 | 0.773 ± 0.117 | 0.208 ± 0.005 | 1.331 ± 0.019 | ||||||||||||

| 45 | D.a affinis | nd | |||||||||||||||

| 46 | D. brochidodroma | nd | |||||||||||||||

| 47 | P. granatum | 9.103 ± 0.533 | 10.080 ± 0.358 | 8.421 ± 0.159 | 56.464 ± 2.298 | 22.133 ± 1.821 | 146.937 ± 0.669 | ||||||||||

| 48 | R. alpinia | nd | |||||||||||||||

nd, not detectable.

Table 8.

Phenolic compound contents (mg/g dry weight) of red and pink flowers.

| Species | Gallic | p-Hydroxybe. | m-Coumaric | p-Coumaric | Vanillic | Caffeic | Syringic | Chlorogenic | Ferulic | Naringin | Crisin | Quercitrin | Myricetin | Quercetin | Kaempferol | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red flowers | |||||||||||||||||

| 49 | A. squarrosa | nd | |||||||||||||||

| 50 | C. argentea | 0.654 ± 0.026 | 1.660 ± 0.007 | 0.665 ± 0.007 | 0.079 ± 0.004 | 0.098 ± 0.013 | 0.179 ± 0.002 | 3.558 ± 0.286 | 0.251 ± 0.008 | 0.572 ± 0.018 | 7.715 ± 0.044 | ||||||

| 51 | C.s roseus | 1.190 ± 0.560 | 16.458 ± 1.017 | 0.691 ± 0.069 | 0.953 ± 0.004 | 0.791 ± 0.056 | 6.029 ± 0.254 | 26.476 ± 2.014 | |||||||||

| 52 | N. oleander | 4.114 ± 0.118 | 6.622 ± 0.307 | 0.764 ± 0.057 | 1.347 ± 0.013 | 4.388 ± 0.041 | 4546 ± 0.385 | 21.781 ± 1.893 | |||||||||

| 53 | A. andraeanum | 0.361 ±0.051 | 6.192 ± 0.177 | 7.664 ± 0.258 | |||||||||||||

| 54 | I. balsamina | 1.503 ± 0.285 | 0.133 ± 0.028 | 1.394 ± 0.190 | 3.244 ±0.052 | ||||||||||||

| 55 | I. walleriana | 3.120 ± 0.145 | 1.195 ± 0.145 | 3.611 ± 0.004 | 8.428 ± 0.384 | ||||||||||||

| 56 | B. cavaleriei | 1.311 ± 0.060 | 0.265 ± 0.013 | 0.641 ± 0.030 | 1.417 ± 0.071 | 4.330 ± 0.213 | |||||||||||

| 57 | B. andraeanum | 0.360 ± 0.046 | 0.273 ± 0.019 | 0.414 ± 0.048 | 0.207 ± 0.001 | 1.984 ± 0.013 | 2.217 ± 0.099 | 4.191 ± 0.049 | 9.646 ± 0.274 | ||||||||

| 58 | Begonia × tuberhybrida | 1.650 ± 0.242 | 3.306 ± 0.069 | 0.642 ± 0.039 | 2.730 ± 0.205 | 8.693 ± 0.874 | |||||||||||

| 59 | D. caryophyllus | 13.167 ± 0.241 | 1.512 ± 0.095 | 0.331 ± 0.031 | 0.396 ± 0.071 | 15.405 ± 2.662 | |||||||||||

| 60 | R. simsii | 0.279 ± 0.057 | 0.138 ± 0.013 | 0.361 ± 0.003 | 0.131 ± 0.003 | 1.142 ± 0.010 | |||||||||||

| 61 | E. rubra | 0.042 ± 0.002 | 0.238 ± 0.068 | 0.326 ± 0.050 | 0.600 ± 0.122 | ||||||||||||

| 62 | E. milii | 4.882 ± 0.502 | 0.347 ± 0.018 | 0.724 ± 0.035 | 0.167 ± 0.018 | 7.414 ± 0.062 | |||||||||||

| 63 | B. macrophylla | nd | |||||||||||||||

| 64 | P. peltatum | 14.741 ± 0.122 | 2.216 ± 0.011 | 1.103 ± 0.102 | 0.248 ± 0.001 | 0.440 ± 0.012 | 8.415 ± 0.012 | 32.452 ± 0449 | |||||||||

| 65 | Pelargonium × hortorum | 7.142 ± 2.789 | 2.011 ± 0.003 | 1.406 ± 0.147 | 1.371 ± 0.185 | 18.655 ± 0.296 | 3.081 ± 0.032 | 68.975 ± 4.079 | |||||||||

| 66 | S. splendens | 1.182 ± 0.014 | 0.683 ± 0.008 | 4.311 ± 0.053 | 0.213 ± 0.003 | 0.801 ± 0.100 | 7.245 ± 0.078 | ||||||||||

| 67 | M. arboreus | 3.440 ± 0.450 | 3.429 ± 0.334 | 0.510 ± 0.071 | 6.166 ± 0.412 | 14.824 ± 1.379 | |||||||||||

| 68 | F. magellanica | 4.327 ± 0.154 | 11.080 ± 0.105 | 1.555 ± 0.022 | 23.538 ± 0.242 | 42.488 ± 1.335 | |||||||||||

| 69 | Rosa hybrid | 3.194 ± 0.642 | 4.989 ± 0.065 | 0.793 ± 0.015 | 0.970 ± 0.075 | 1.065 ± 0.248 | 6.339 ± 0.029 | 19.201 ± 1.513 | |||||||||

| 70 | P. rhoeas | nd | |||||||||||||||

| 71 | W. coccinea | nd | |||||||||||||||

| 72 | A. majus | 0.911 ± 0.002 | 2.443 ± 0.312 | 0.146 ± 0.019 | 4.354 ± 0.197 | 8.962 ± 0.106 | |||||||||||

| 73 | R. equisetiformis | 2.577 ± 0.193 | 0.137 ± 0.032 | 4.795 ± 0.061 | |||||||||||||

| 74 | Petunia × hybrid | 11.005 ± 0.795 | 2.724 ± 0.123 | 13.729 ± 0.191 | |||||||||||||

| 75 | L. camara | 9.204 ± 0.120 | 0.911 ± 0.003 | 1.001 ± 0.021 | 0.603 ± 0.003 | 5.833 ± 0.804 | 2.306 ± 0.011 | 2.642 ± 0.333 | 22.478 ± 0.301 | ||||||||

| 76 | Verbena × hybrid | 2.493 ± 0.176 | 1.373 ± 0.001 | 0.949 ± 0.139 | 1.187 ± 0.081 | 9.888 ± 0.148 | 4.310 ± 0.214 | 21.283 ± 0.834 | |||||||||

| Pink flowers | |||||||||||||||||

| 77 | C. argentea | 1.635 ± 0.068 | 6.172 ± 0.254 | 0.239 ± 0.022 | 0.218 ± 0.001 | 0.634 ± 0.013 | 4.615 ± 0.074 | 13.765 ± 0.437 | |||||||||

| 78 | N. oleander | 5.514 ± 0.513 | 0.384 ± 0.086 | 7.902 ± 0.090 | 1.123 ± 0.101 | 0.464 ± 0.069 | 0.290 ± 0.045 | 15.677 ± 0.904 | |||||||||

| 79 | B. argentea | 0.214 ± 0.021 | 0.274 ± 0.029 | 0.488 ± 0.051 | |||||||||||||

| 80 | G. hybrid | 0.491 ± 0.065 | 0.473 ± 0.003 | 0.118 ± 0.019 | 1.229 ± 0.097 | ||||||||||||

| 81 | D. caryophyllus | 8.479 ± 0.385 | 0.714 ± 0.032 | 1.527 ± 0.069 | 0.087 ± 0.004 | 10.807 ± 0.049 | |||||||||||

| 82 | S. officinalis | 1.733 ± 0.160 | 8.728 ± 0.943 | 10.461 ± 1.103 | |||||||||||||

| 83 | R. simsii | 0.279 ± 0.057 | 0.138 ± 0.013 | 0.361 ± 0.003 | 0.131 ± 0.003 | 1.142 ± 0.102 | |||||||||||

| 84 | T. cernuum | 0.279 ± 0.005 | 0.166 ± 0.004 | 1.354 ± 0.079 | 0.605 ± 0.031 | 2.674 ± 0.187 | |||||||||||

| 85 | E. grandiflorum | 0.257 ± 0.008 | 0.338 ± 0.086 | 1.713 ± 0.141 | 3.105 ± 0.271 | ||||||||||||

| 86 | P. domesticum | 15.733 ± 0.120 | 6.495 ± 0.152 | 0.310 ± 0.011 | 1.345 ± 0.086 | 3.485 ± 0.484 | 32.678 ± 2.198 | ||||||||||

| 87 | Pelargonium × hortorum | 22.520 ± 1.728 | 3.162 ± 0.070 | 3.704 ± 0.073 | 19.506 ± 1.375 | 6.291 ± 2.100 | 55.183 ± 5.346 | ||||||||||

| 88 | H. petiolaris | 10.889 ± 0.114 | 34.229 ± 2.096 | 6.566 ± 0.175 | 3.183 ± 0.162 | 4.350 ± 0.224 | 2.154 ± 0.115 | 61.371 ± 4.260 | |||||||||

| 89 | C. hyssopifolia | 11.312 ± 0.867 | 11.312 ± 0.867 | ||||||||||||||

| 90 | L. indica | 0.424 ± 0.006 | 2.667 ± 0.395 | 3.091 ± 0.484 | |||||||||||||

| 91 | G. arboreum | 0.367 ± 0.010 | 2.762 ± 0.326 | 0.545 ± 0.036 | 0.862 ± 0.073 | 0.741 ± 0.034 | 5.276 ± 0.479 | ||||||||||

| 92 | M. jalapa | 4.530 ± 0.048 | 2.230 ± 0.022 | 0.729 ± 0.044 | 0.369 ± 0.012 | 0.332 ± 0.013 | 0.373 ± 0.009 | 0.922 ± 0.123 | 9.485 ± 0.271 | ||||||||

| 93 | P. aphrodite | 10.146 ± 0.349 | 1.614 ± 0.049 | 17.202 ± 0.282 | 3.136 ± 0.020 | 39.969 ± 1.073 | |||||||||||

| 94 | P. oleracea | 0.402 ± 0.111 | 4.008 ± 0.160 | 0.125 ± 0.007 | 0.347 ± 0.050 | 4.389 ± 0.021 | |||||||||||

| 95 | Rosa hybrid | 5.799 ± 0.424 | 0.333 ± 0.014 | 0.351 ± 0.050 | 7.770 ± 0.033 | ||||||||||||

| 96 | Verbena ×hybrid | 18.240 ± 1.965 | 1.470 ± 0.169 | 6.890 ± 0.668 | 0.198 ± 0.014 | 26.797 ± 2.816 | |||||||||||

nd, not detectable.

Table 9.

Phenolic compound contents (mg/g dry weight) of lilac and blue flowers.

| Species | Gallic | p-Hydroxybe. | m-Coumaric | p-Coumaric | Vanillic | Caffeic | Syringic | Chlorogenic | Ferulic | Naringin | Crisin | Quercitrin | Myricetin | Quercetin | Kaempferol | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lilac flowers | |||||||||||||||||

| 97 | A. schoenoprasum | 2.156 ± 0.0244 | 2.736 ± 0.274 | 0.190 ± 0.007 | 0.031 ± 0.006 | 0.894 ± 0.003 | 1.284 ± 0.010 | 1.978 ± 0.125 | 9.269 ± 0.670 | ||||||||

| 98 | C. roseus | 1.680 ± 0.094 | 7.023 ± 0.685 | 2.263 ± 0.169 | 1.021 ± 0.058 | 2.525 ± 0.150 | 14.559 ± 1.223 | 29.137 ± 3.556 | |||||||||

| 99 | C. seridis | 0.987 ± 0.138 | 0.544 ± 0.030 | 0.532 ± 0.024 | 1.087 ± 0.001 | 7.465 ± 0.174 | 0.288 ± 0.019 | 2.044 ± 0.136 | 3.055 ± 0.612 | 16.001 ± 2.364 | |||||||

| 100 | C. intybus | 1.433 ± 0.123 | 3.938 ± 0.175 | 0.388 ± 0.069 | 0.512 ± 0.004 | 0.911 ± 0.061 | 0.446 ± 0.014 | 0.415 ± 0.053 | 9.891 ± 0.848 | ||||||||

| 101 | O. fruticosum | 0.898 ± 0.182 | 0.658 ± 0.071 | 0.561 ± 0.094 | 0.729 ± 0.133 | 3.051 ± 0.501 | |||||||||||

| 102 | A. montanum | 0.105 ± 0.024 | 0.871 ± 0.098 | 0.191 ± 0.023 | 1.677 ± 0.253 | ||||||||||||

| 103 | C. carpatica | 4.031 ± 0.349 | 0.621 ± 0.008 | 4.785 ± 0.501 | |||||||||||||

| 104 | P. domesticum | 17.440 ± 1.088 | 10.666 ± 0.513 | 2.397 ± 0.088 | 2.434 ± 0.121 | 0.711 ± 0.059 | 1.045 ± 0.116 | 1.297 ± 0.015 | 37.965 ± 0.125 | ||||||||

| 105 | P. × hortorum | 27.709 ± 0.061 | 6.280 ± 0.437 | 1.537 ± 0.219 | 1.672 ± 0.002 | 2.599 ± 0.125 | 39.797 ± 0.096 | ||||||||||

| 106 | M. × piperita | 0.062 ± 0.003 | 0.083 ± 0.004 | 0.210 ± 0.013 | 0.133 ± 0.007 | 0.488 ± 0.027 | |||||||||||

| 107 | O. basilicum | 0.197 ± 0.008 | 0.197 ± 0.008 | ||||||||||||||

| 108 | H. syriacus | 10.489 ± 0.107 | 19.139 ± 1.870 | 0.318 ± 0.036 | 29.946 ± 2.013 | ||||||||||||

| 109 | B. spectabili | 3.844 ± 0.218 | 0.352 ± 0.015 | 7.161 ± 0.409 | 4.422 ± 0.269 | 15.779 ± 1.334 | |||||||||||

| 110 | L. sinuatum | 0.393 ± 0.077 | 0.350 ± 0.008 | 0.120 ± 0.030 | 0.972 ± 0.073 | 2.036 ± 0.171 | |||||||||||

| 111 | F. aubertii | 0.749 ± 0.011 | 0.160 ± 0.010 | 0.377 ± 0.022 | 0.711 ± 0.092 | 0.388 ± 0.130 | 2.659 ± 0.276 | ||||||||||

| 112 | Petunia × hybrida | 0.197 ± 0.010 | 0.683 ± 0.082 | 0.187 ± 0.020 | 0.846 ± 0.052 | 0.647 ± 0.020 | 1.322 ± 0.102 | 0.909 ± 0.035 | 4.791 ± 0.320 | ||||||||

| 113 | S. rantonnetti | 1.213 ± 0.083 | 0.612 ± 0.017 | 0.685 ± 0.072 | 0.391 ± 0.002 | 0.278 ± 0.002 | 3.180 ± 0.177 | ||||||||||

| 114 | Verbena × hybrid | 6.323 ± 0.143 | 0.504 ± 0.029 | 1.467 ± 0.056 | 0.925 ± 0.022 | 1.282 ± 0.158 | 3.519 ± 0.355 | 8.950 ± 0.526 | 24.044 ± 2.346 | ||||||||

| 115 | V.agnus- castus | 5.337 ± 0.337 | 15.534 ± 0.790 | 0.564 ± 0.010 | 5.344 ± 0.168 | 1.580 ± 0.035 | 0.363 ± 0.030 | 28.994 ± 2.552 | |||||||||

| Blue flowers | |||||||||||||||||

| 116 | A. africanus | 6.751 ± 0.339 | 1.452 ± 0.069 | 1.032 ± 0.089 | 3.663 ± 0.171 | 13.687 ± 0.736 | |||||||||||

| 117 | C. althaeoides | 0.029 ± 0.004 | 3.938 ± 0.309 | 0986 ± 0.127 | 2.995 ± 0.387 | 1.568 ± 0.203 | 9.516 ± 1.231 | ||||||||||

| 118 | S. ionantha | 1.519 ± 0.037 | 19.628 ± 2.488 | 2.940 ± 0.062 | 1.641 ± 0.200 | 10.830 ± 0.428 | 37.201 ± 3.850 | ||||||||||

| 119 | S. aemula | 2.659 ± 0.128 | 0.534 ± 0.010 | 0.529 ± 0.078 | 0.851 ± 0.064 | 1.322 ± 0.048 | 0.837 ± 0.171 | 7.257 ± 0.525 | |||||||||

| 120 | A. foeniculum | 3.469 ± 0.258 | 0.648 ± 0.013 | 6.628 ± 0.470 | |||||||||||||

| 121 | L. angustifolia | 1.614 ± 0.235 | 1.666 ± 0.231 | 1.207 ± 0.067 | 0.413 ± 0.029 | 5.634 ± 0.834 | |||||||||||

| 122 | R. officinalis | 1.634 ± 0.050 | 4.981 ± 0.490 | 1.035 ± 0.020 | 7.651 ± 0.560 | ||||||||||||

| 123 | P. × belotti | 6.005 ± 0.614 | 0.359 ± 0.024 | 6.364 ± 1.475 | |||||||||||||

| 124 | P. vulgaris | 4.490 ± 0.097 | 4.490 ± 0.097 | ||||||||||||||

| 125 | Petunia × hybrida | 2.300 ± 0.251 | 0.578 ± 0.013 | 0.554 ± 0.050 | 2.966 ± 0.005 | 0.948 ± 0.041 | 7.850 ± 0.048 | ||||||||||

Figure 4.

Chromatogram of lilac Catharanthus roseus phenolics at 280 nm (A) and 320 nm (B). 1. p-Hydroxybenzoic acid, 2. m-Coumaric acid, 3. Chlorogenic acid, 4. Quercitrin, 5. Quercetin, 6. Kaempferol.

Figure 5.

Frequency, mean contents and standard deviations of phenolics and major sources. Frequency (A), mean contents of individual phenolics (B), total phenolics content (C), and list of species with high concentrations of phenolics. Number within the figures represent the sample under study.

4. Discussion

4.1. Color Parameters and Other Characteristics

The great majority of the flowers were edible (n = 111, i.e., 89%); 70% of the families studied (52 families) included edible flowers. For example, the families Asteraceae and Lamiaceae contained six and seven edible species, respectively [20]. Concerning their uses, the most frequent were in salads (31.3% of the total use of the flowers) and infusions (28.9%), followed by teas (15.7%), desserts (13.3%) and others, including as garnishes and colorants (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). The different culinary uses of flowers depend to some extent on their size, shape, and color, as suggested by other authors [4]. These characteristics varied considerably among the samples surveyed in the present study. Different shapes were found, such as tubular (e.g., Russelia equisetiformis Schltdl. Et Cham.), bilabial (e.g., Rosmarinus officinalis L.), flared (e.g., Punica granatum L.), and flowers that form part of a cluster (e.g., Plantago major L., Salvia splendens Sellow ex Schylt., Vitex agnus-castus L., Allium schoenoprasum L., and Lantana camara L.). On the other hand, the flowers showed a great variety of colors (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3), such as white (e.g., Portulaca oleracea L.), yellow (e.g., Anthemis tinctoria L.), orange (e.g., Punica granatum L.), pink (e.g., Diantuhus caryophyllus L.), red (e.g., Pelargonium × hortorum), lilac (e.g., Petunia hybrid), and blue (e.g., Lavandula angustifolia Mill.). The color parameters ranged between 14.2 and 87.1, −9.2 and 57.2, −25.7 and 88.6, 2.9 and 89.9, and 3.4 and 359.6 for L* (lightness), a* (ranging from green to red), b* (ranging from blue to yellow), C*ab (chroma, the quantitative expression of color), and hab (hue angle, the qualitative expression of color), respectively. The variety of colors found in the petals of flowers under study can be explained by the different contents of carotenoids and phenolics, which are usually the main contributors to the color of these structures [34,35].

The humidity of the petals ranged between 54.5 and 99.7%, a wider interval compared to that recently reported by other authors (70 and 95%) [4].

4.2. Carotenoids

4.2.1. Selection of the Extraction Solvents

Regarding the quantification of carotenoids in flowers, there are several studies that use different extraction solvents; however, the mixtures acetone: methanol (2:1) and ethyl acetate: methanol: petroleum ether (1:1:1) in this study presented the highest extraction percentage. Acetone: methanol (2:1) was selected as the extraction solvent for the studied flowers due to its slightly higher yield and its simplicity of preparation.

4.2.2. Carotenoid Levels

At this point it is important to notice that saponification, which simplifies the identification of carotenoids, has the disadvantage that it leads to carotenoid losses [30], so the information provided must be interpreted with this in mind. This fact has been observed in the TCC levels of red and lilac flowers of Catharanthus roseus (3.7 µg/g DW and not detectable, respectively) and Pelargonium × hortorum (3.5 µg/g DW and not detectable, respectively). Although the TCC levels measured in non-saponified extracts by spectrophotometry showed values of 185, 132, and 100 µg/g DW, respectively, no individual carotenoids were detected by RRLC after the saponification of the extracts (data not shown).

On the other hand, flowers of the same family but different species presented different profiles in most cases. At this point it is important to notice that the profiles of the secondary metabolites of plants in general and carotenoids and phenolics in particular are dependent on different factors, including genotype as one of the most important, along with ambient/seasonal (light quality and quantity, temperature), and agronomic factors (irrigation, fertilization, etc.), among others [36,37,38].

Lutein (31.7%), β-cryptoxanthin (16.6%), and β-carotene (15.4%) were the most frequent carotenoids (Figure 3, section A). These three carotenoids are, along with zeaxanthin, α-carotene, lycopene, phytoene, and phytofluene, the major carotenoids in human tissues and fluids, all of which are thought to promote health [13]. All of them, except phytofluene, were identified in the set of samples, as well as others not reported in humans, such as lutein epoxide, antheraxanthin, violaxanthin, zeinoxanthin, luteoxanthin, and neochrome (Figure 3, section A).

Figure 3, section B, presents the mean contents and standard deviations of the individual carotenoids. The levels of the colorless carotenoid phytoene ranged between 2.8 (Trifolium cernuum) and 126.4 µg/g DW (Guzmania hybrid). The concentrations of lutein ranged from 0.7 to 1204.0 µg/g DW. The best source by far was Senna papillosa yellow (1204.0 µg/g DW), followed by Portulaca oleracea yellow (334.9 µg/g DW) and Aphelandra squarrosa red (209.0 µg/g DW), in descending order. The levels of lutein epoxide ranged from 2.9 to 75.8 µg/g DW. The highest amounts were found in Lantana camara yellow (75.8 µg/g DW), Mentha suaveolens white (38.5 µg/g DW), Solanum lycopersicum yellow (31.9 µg/g DW), and Mentha × piperita lilac (23.4 µg/g DW). The concentrations of luteoxanthin fell in an interval of 1.1–98.7 µg/g DW, and the main sources were Brownea macrophylla red (98.7 µg/g DW), Mentha suaveolens white (6.9 µg/g DW), and Mentha × piperita lilac (5.9 µg/g DW). On the other hand, the concentrations of antheraxanthin ranged from 1.8 to 18.3 µg/g DW. Capsicum annuum white (18.3 µg/g DW), Campanula shetleri white (11.4 µg/g DW), and Rosa hybrid pink (9.6 µg/g DW) were the flowers with the highest contents. The 9-Cis-antheraxanthin concentration values fluctuated between 5.4 and 433.4 µg/g DW. The highest levels were detected in Portulaca oleracea yellow (433.4 µg/g DW) and pink (355.2 µg/g DW) petals. The concentrations of violaxanthin ranged from 4.0 to 258.8 µg/g DW. Drymonia brochidodroma orange (258.8 µg/g DW), Aphelandra squarrosa red (140 µg/g DW), and Senna papillosa yellow (86.0 µg/g DW) were the best sources. The concentrations of the carotenoid identified as zeinoxanthin varied between 4.5 and 1311.9 µg/g DW. The best sources were Senna papillosa yellow (1311.9 µg/g DW) and, to a much lesser extent, Portulaca oleracea yellow (239.8 µg/g DW). The levels of the provitamin A carotenoid β-cryptoxanthin ranged from 4.2 to 33.4 µg/g DW; the highest amounts were found in Brownea macrophylla red (33.4 µg/g DW) and Lavandula angustifolia blue (19.3 µg/g DW). The amounts of the provitamin A carotenoid α-carotene were in the interval of 12.3–1451.9 µg/g DW. Renealmia alpinia orange (1451.9 µg/g DW) and, to a lesser extent, Lantana camara yellow (731.5 µg/g DW) and Spathiphyllum montanum white (82.0 µg/g DW) stood out as the main sources.

Britton and Khachik proposed a criterion through which to classify food sources according to their carotenoid content expressed in mg/100 g fresh weight. According to this criterion, the contents of a specific carotenoid can be classified as low (0–0.1 mg/100 g), moderate (0.1–0.5 mg/100 g), high (0.5–2 mg/100 g), or very high (>2 mg/100 g).

Using this criterion to categorize carotenoid sources, the petals with high (0.5–2 mg/100 g) or very high (>2 mg/100 g) carotenoid levels are Renealmia alpinia (15.0 mg/100 g FW), Senna papillosa (4.5 mg/100 g FW), Sophora japonica, Brownea macrophylla (2.6 mg/100 g FW) (β-carotene), Tecoma capensis (0.5 mg/100 g FW) (β-cryptoxanthin), Senna papillosa (31.8 mg/100 g FW), Aphelandra squarrosa (5.6 mg/100 g FW), Portulaca oleracea (4.7 mg/100 g FW) (lutein), Lantana camara (1.7 mg/100 g FW)(zeaxanthin), and Lantana camara (0.6 mg/100 g FW) (phytoene).

On the other hand, the maximum daily intakes of carotenoids reported in recent reviews were 4.1 (lutein + zeaxanthin), 1.4 (β-cryptoxanthin), 2.4 (α-carotene), 8.8 (β-carotene), 9.4 (lycopene), 2.0 (phytoene), and 0.7 mg (phytofluene) [13]. These intakes could be obtained with 87.2 g FW of Portulaca oleracea (lutein + zeaxanthin), 280 g FW of Tecoma capensis (β-cryptoxanthin), 15.2 g FW of Renealmia alpinia (α-carotene), 58.7 g FW of Renealmia alpinia (β-carotene), and 153.8 g FW of Guzmania hibrid (phytoene). These data indicate that the consumption of just a few grams of petals of some flowers (for instance, Portulaca oleracea or Renealmia alpinia) can be useful to increase considerably the intakes of health-promoting carotenoids.