Abstract

Two new species, Burkholderia multivorans and Burkholderia vietnamiensis, and three genomovars (genomovars I, III, and IV) currently constitute the Burkholderia cepacia complex. A panel of 30 well-characterized strains representative of each genomovar and new species was assembled to assist with identification, epidemiological analysis, and virulence studies on this important group of opportunistic pathogens.

The gram-negative bacterium Burkholderia cepacia is a problematic pathogen in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) (18) or chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) (28) and in other vulnerable individuals (31). At least five genomovars constitute isolates which were previously classified as B. cepacia, and these strains have been collectively designated the B. cepacia complex (30). Bacteriological identification, epidemiological tracking, and virulence studies will all benefit from the use of a defined set of strains representative of each genomovar.

Assembly of a strain panel.

A B. cepacia complex strain panel consisting of 30 strains representative of all five currently defined genomovars was assembled (Table 1). Strains were cultured as described previously (4, 11, 30) and deposited in the Belgium Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms/Laboratorium Microbiologie Ghent (BCCM/LMG) (http://www.belspo.be/bccm/) bacterial collection at the University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium.

TABLE 1.

The B. cepacia complex strain panel

| Strain name | Accession no. from BCCM/LMG Culture Collection | Source and locationa | Strain typeb | Presence of:

|

Transformation ratec | Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCESM | cblA | ||||||

| B. cepacia genomovar I | |||||||

| ATCC 25416T | LMG 1222T | Onion, USA | 01 | − | − | 102 | 9, 22, 38 |

| ATCC 17759 | LMG 2161 | Soil, Trinidad | 15 | − | − | 102 | 29 |

| CEP509 | LMG 18821 | CF, Australia | 18 | − | − | 104 | This study |

| LMG 17997 | LMG 17997 | UTI, Sweden | 19 | − | − | 102 | This study |

| B. multivorans | |||||||

| C5393 | LMG 18822 | CF, Canada | 03d | − | − | Negligible | 19 |

| LMG 13010T | LMG 13010T | CF, Belgium | 09 | − | − | 105 | 24, 30 |

| C1576 | LMG 16660 | CF-e, UK | 10 | − | − | 104 | 30, 33 |

| CF-A1-1 | LMG 18825 | CF-e, UK | 11 | − | − | Negligible | 23 |

| JTC | LMG 18824 | CGD, USA | 12 | − | − | 105 | 28 |

| C1962 | LMG 16665 | Clinic, UK | 24 | − | − | 106 | 12 |

| ATCC 17616 | LMG 17588 | Soil, USA | 14 | − | − | 103 | 3, 6, 29, 30 |

| 249-2 | LMG 18823 | Laboratory, USA | 14 | − | − | 103 | 6 |

| B. cepacia genomovar III | |||||||

| J2315 | LMG 16656 | CF-e, UK | 02d | + | + | Negligiblee | 10, 13 |

| BC7 | LMG 18826 | CF-e, Canada | 02d | + | + | Negligiblee | 26 |

| K56-2 | LMG 18863 | CF-e, Canada | 02d | + | + | 104 | 5, 16 |

| C5424 | LMG 18827 | CF-e, Canada | 02d | + | + | 103e | 19, 20 |

| C6433 | LMG 18828 | CF-e, Canada | 04d | + | − | 103e | 19, 20 |

| C1394 | LMG 16659 | CF-e, UK | 13d | + | − | 103e | 19, 27 |

| PC184 | LMG 18829 | CF-e, USA | 17d | + | − | 105e | 17 |

| CEP511 | LMG 18830 | CF-e, Australia | 05 | + | − | 106 | 19 |

| J415 | LMG 16654 | CF, UK | 23 | − | − | 105 | 8 |

| ATCC 17765 | LMG 18832 | UTI, UK | 06 | + | − | 105 | 29 |

| B. cepacia genomovar IV | |||||||

| LMG 14294 | LMG 14294 | CF, Belgium | 16d | − | − | 102e | 24 |

| C7322 | LMG 18870 | CF, Canada | 16d | − | − | 103 | 19 |

| LMG 14086 | LMG 14086 | Respirator, UK | 16d | − | − | 103 | 4 |

| LMG 18888 | LMG 18888 | Clinical, Belgium | 07 | − | − | 103 | 31 |

| B. vietnamiensis | |||||||

| PC259 | LMG 18835 | CF, USA | 08d | − | − | 103 | 2, 15 |

| LMG 16232 | LMG 16232 | CF, Sweden | 20 | − | − | Negligible | 30 |

| FC441 | LMG 18836 | CGD, Canada | 21 | − | − | 104 | This study |

| LMG 10929T | LMG 10929T | Rice, Vietnam | 22 | − | − | 106 | 7, 30 |

CF, infection of a CF patient; CF-e, strain that has spread epidemically among patients with CF; CGD, infection of a CGD patient; UK, United Kingdom; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Strain types observed by RAPD and PFGE fingerprinting correlated for isolates examined in the panel; hence, each strain was given a single numerical strain type.

Transformation rate per microgram of DNA electroporated into competent cells is the average number of Tpr colonies obtained from two independent experiments rounded up to the nearest log 10. Strains producing fewer than 100 Tpr colonies per electroporation were considered as having a negligible transformation rate.

Strain type assigned for this study correlates to the numerical RAPD type assigned previously to this fingerprint pattern (19).

Strains requiring selection on LB agar containing 400-μg/ml trimethoprim sulfate to overcome background due to intrinsic resistance; pUCP29T transformants from all other strains were selected on Luria-Bertani agar containing 100-μg/ml trimethoprim sulfate.

Genomovar analysis and strain typing.

Genomovar testing was performed by whole-cell protein profile analysis as described previously (30). In addition, amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis (4) and sequence analysis of the recA gene (21) were used to confirm the classifications obtained by conventional analysis (30). Genetic typing of each strain was performed by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis (19) and by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (25) as described previously. The presence of the cable pilus subunit gene (cblA) (26) and B. cepacia epidemic strain marker (BCESM) were determined as described previously (20).

Genetic manipulation.

Susceptibility to trimethoprim and transformation by electroporation with the broad-host-range vector pUC29T (32) were carried out as described elsewhere (1).

B. cepacia genomovar I.

Four strains representative of this genomovar were included in the panel (Table 1). Strain ATCC 25416T, isolated from onions, has been genetically mapped (25) and well characterized phytopathologically (9). Strain ATCC 17759, also an environmental isolate, has been studied for its autoinducer production and potential for interspecies signalling (22). Strain CEP509 was recovered from a patient with CF in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia (Table 1); isolates with RAPD fingerprints identical to those of strain CEP509 were recovered from three other CF patients attending this treatment center. Strain LMG 17997 was isolated in 1976 from human urine and persisted in the urinary tract of this patient for 10 years with no clinical symptoms of infection (Table 1).

B. multivorans (formerly B. cepacia genomovar II).

Eight Burkholderia multivorans strains were included in the panel (Table 1). Strain C5393 was recovered from a CF patient in Vancouver, Canada, and was not associated with patient-to-patient spread (19). Strain LMG 13010, the type strain of B. multivorans, was recovered from a Belgian CF patient and was also not associated with epidemic spread (24). Strain C1576 was recovered from a CF patient in Glasgow, Scotland, and was the index strain in an outbreak among 17 pediatric CF patients attending a treatment center in which five children died after colonization (33). Strain CF-A1-1 is a representative of an outbreak among four adult CF patients in Cardiff, Wales (23). Strain JTC was recovered from a patient with CGD and has been demonstrated to be resistant to nonoxidative killing by human neutrophils (28). Strain C1962 caused multiple brain abscesses in an immunocompetent individual (12). Strain ATCC 17616 is a soil isolate from the United States (29) and has been well characterized with regard to its metabolism, genetics, and genome structure (3, 6, 29). B. multivorans 249-2 was derived in the laboratory from ATCC 17616; it has suffered a genomic deletion resulting in a number of phenotypic alterations, including susceptibility to gentamicin (6), which is not a characteristic trait for strains of the B. cepacia complex (11).

B. cepacia genomovar III.

Ten genomovar III strains were included in the panel (Table 1). Four strains from the major transmissible lineage known as ET12 (14), the cblA+ strain (26), or RAPD type 2 (19, 20) were included. Strain J2315 was the index strain from which patient-to-patient spread of this lineage was first reported in Edinburgh, Scotland (10). This strain also produces a hemolysin capable of inducing apoptosis and degranulation in human neutrophils (13). Strain BC7 was recovered from a CF patient in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and has been studied extensively with regard to binding to mucins or respiratory epithelial cells and cable pilus virulence factor (26). Strain K56-2 was also recovered from a CF patient in Toronto and has proven to be highly amenable to genetic manipulation, enabling characterization of siderophore production (5) and genes involved in quorum sensing (16). Strain C5424 was recovered from a CF patient in Vancouver (19) and was the isolate from which the BCESM DNA was cloned and characterized (20). Strain C6433 is a representative of B. cepacia RAPD type 4 strains which have spread among CF patients in Vancouver (19). Strain C1394 was responsible for an outbreak among CF patients attending a treatment center in Manchester, England (19, 27). Strain PC184 was recovered from a pediatric CF patient attending a treatment center in Cleveland, Ohio, and was examined in one of the earliest reports of transmission of B. cepacia among patients with CF (17). Genomovar III strain CEP511 was recovered from a CF patient in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and is also representative of an epidemic strain which had spread among several patients (19). Strain J415 was not associated with patient-to-patient spread (8) and does not contain either the BCESM or cblA gene (Table 1). This strain was the first reported case of B. cepacia syndrome in a CF patient in the United Kingdom; however, it did not transfer to the potentially susceptible CF sibling of the child involved (8). Strain ATCC 17765 was isolated in 1964 from a urinary tract infection of a child in Bristol, England (29).

B. cepacia genomovar IV.

Four genomovar IV isolates were included in the panel (Table 1). Strain LMG 14294 was isolated from sputum of a Belgian CF patient (24). A second patient from the same center carried an indistinguishable isolate; the clinical condition of both patients was stable (24). Genomovar IV strain C7322 was recovered from an adult CF patient attending a clinic in Vancouver; no other patients at this center were colonized with the same strain type (19). Strain LMG 14086 was isolated from a respirator in a hospital in the United Kingdom (4). Strain LMG 18888 is a non-CF isolate involved in an outbreak in a cardiology ward in Belgium (31).

B. vietnamiensis (formerly B. cepacia genomovar V).

Four Burkholderia vietnamiensis strains, three of which were recovered from patients with CF, were included within the panel (Table 1). B. vietnamiensis PC259 was recovered from a CF patient attending a treatment center in Seattle, Washington (15), and subcultures from the same patient have been shown to invade respiratory epithelial cells in culture (2). Strain LMG 16232 was recovered from a CF patient in Sweden. Strain FC441 was recovered from a 9-year-old boy with X-linked recessive CGD who was treated in Vancouver and survived septicemia with multiple-organ involvement (Table 1). Finally, B. vietnamiensis LMG 10929 is the type strain for this species (7) and was recovered from rice rhizosphere in Vietnam.

Genetic heterogeneity.

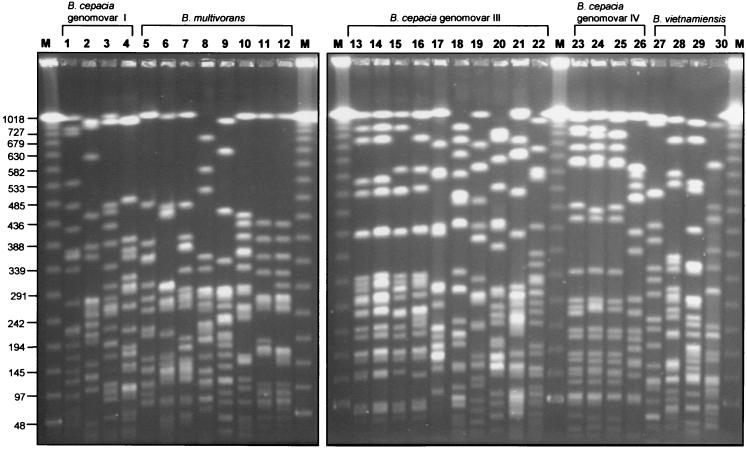

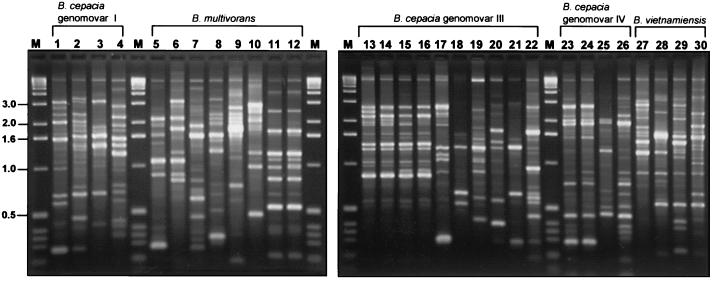

Analysis by RAPD and PFGE fingerprinting demonstrated that the strains selected for the panel were, for the most part, genetically heterogenous, representing 24 different B. cepacia complex strain types (Table 1). Strain types detected by PFGE (Fig. 1) and RAPD (Fig. 2) correlated exactly, and each method was able to type strains from all five genomovars. Three groups of strains were clonal (Table 1): B. multivorans strain ATCC 17616 and its laboratory derivative 249-2, the four ET12 strains (J2315, BC7, K56-2, and C5424), and three genomovar IV strains (LMG 14294, C7322, and LMG 14086). The remaining 21 strains within the panel each possessed a unique genetic fingerprint, and each was designated with an individual strain type (Table 1 and Fig. 1 and 2).

FIG. 1.

SpeI-generated macrorestriction fragments of the B. cepacia complex strain panel separated by PFGE. Digestion and separation of macrorestricted DNA were performed as described in the text, and restriction fragments were visualized after staining with ethidium bromide. Molecular size standards were run in the lanes labelled M, and the sizes of relevant marker bands (in kilobases) are shown on the left. Strains analyzed (see Table 1) in each lane are as follows: 1, ATCC 25416T; 2, ATCC 17759; 3, CEP509; 4, LMG 17997; 5, C5393; 6, LMG 13010T; 7, C1576; 8, CP-A1-1; 9, JTC; 10, C1962; 11, ATCC 17616; 12, 249-2; 13, J2315; 14, BC7; 15, K56-2; 16, C5424; 17, C6433; 18, C1394; 19, PC184; 20, CEP511; 21, J415; 22, ATCC 17765; 23, LMG 14294; 24, C7322; 25, LMG 14086; 26, LMG 18888; 27, PC259; 28, LMG 16232; 29, FC441; 30, LMG 10929T.

FIG. 2.

RAPD fingerprints generated by PCR primer 270 from DNA extracted from strains of the B. cepacia complex panel. RAPD analysis of each B. cepacia strain from the panel was performed exactly as described previously (19). Molecular size standards were run in the lanes labelled M, and the sizes of relevant marker bands (in kilobases) are indicated to the left. Strains analyzed (Table 1) in each lane are as follows: 1, ATCC 25416T; 2, ATCC 17759; 3, CEP509; 4, LMG 17997; 5, C5393; 6, LMG 13010T; 7, C1576; 8, CP-A1-1; 9, JTC; 10, C1962; 11, ATCC 17616; 12, 249-2; 13, J2315; 14, BC7; 15, K56-2; 16, C5424; 17, C6433; 18, C1394; 19, PC184; 20, CEP511; 21, J415; 22, ATCC 17765; 23, LMG 14294; 24, C7322; 25, LMG 18888; 26, LMG 14086; 27, PC259; 28, LMG 16232; 29, FC441; 30, LMG 10929T.

Strains suitable for genetic manipulation.

Each genomovar possessed a strain which was readily transformable with plasmid DNA encoding a trimethoprim resistance marker, indicating that they may be useful as genetic tools (Table 1). Strain K56-2 (genomovar III) appears to be a particularly useful strain for genetic analysis. It is representative of the major epidemic CF clone (10, 14, 19) and has already proven highly amenable to molecular characterization by a number of different strategies, including transposon mutagenesis, site-directed mutagenesis by allelic exchange, and genetic complementation (16).

In terms of diversity, the panel is representative of the large variety of clinical infections, environments, and geographic locations from which B. cepacia complex strains may be recovered; however, the prevalence of each genomovar in both clinical and natural settings remains to be determined by systematic study.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (E.M. and D.P.S.) and UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust (P.V. and J.R.W.G., grant RS15; E.M. grant PJ 472). P.V. is indebted to the Fund for Scientific Research—Flanders (Belgium) for a postdoctoral research fellowship. T.C. acknowledges the bursary for advanced study from the Vlaams Instituut voor Bevordering van Wetenschappelijk-technologisch onderzoek in de Industrie (Belgium).

We are grateful to Jocelyn Bischof, Deborah Henry, and Gary Probe for excellent technical assistance and to the International B. cepacia Working Group (IBCWG) for suggestions on the choice of strains. We are indebted to the following investigators for contributing strains for inclusion within the strain panel: Jane Burns, Enevold Falsen, Tom Lessie, John LiPuma, Henry Ryley, Uma Sajjan, and Pam Sokol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burns J L, Hedin L A. Genetic transformation of Pseudomonas cepacia using electroporation. J Microbiol Methods. 1991;13:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns J L, Jonas M, Chi E Y, Clark D K, Berger A, Griffith A. Invasion of respiratory epithelial cells by Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4054–4059. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4054-4059.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng H-P, Lessie T G. Multiple replicons constituting the genome of Pseudomonas cepacia 17616. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4034–4042. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.4034-4042.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coenye T, Schouls L M, Govan J R W, Kersters K, Vandamme P. Identification of Burkholderia species and genomovars from cystic fibrosis patients by AFLP fingerprinting. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:1657–1666. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-4-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darling P, Chan M, Cox A D, Sokol P A. Siderophore production by cystic fibrosis isolates of Burkholderia cepacia. Infect Immun. 1998;66:874–877. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.874-877.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaffney T D, Lessey T G. Insertion-sequence-dependent rearrangements of Pseudomonas cepacia plasmid pTGL1. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:224–230. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.224-230.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillis M, Van T V, Bardin R, Goor M, Hebbar P, Willems A, Segers P, Kersters K, Heulin T, Fernandez M P. Polyphasic taxonomy in the genus Burkholderia leading to an emended description of the genus and proposition of Burkholderia vietnamiensis sp. nov. for N2-fixing isolates from rice in Vietnam. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:274–289. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass S, Govan J R W. Pseudomonas cepacia—fatal pulmonary infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis. J Infect. 1986;13:157–158. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(86)92953-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez C F, Pettit E A, Valadez V A, Provin E M. Mobilization, cloning and sequence determination of a plasmid encoded polygalacturonase from a phytopathogenic Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:840–851. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.7.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Govan J R W, Brown P H, Maddison J, Doherty C J, Nelson J W, Dodd M, Greening A P, Webb A K. Evidence for transmission of Pseudomonas cepacia by social contact in cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 1993;342:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91881-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry D A, Campbell M E, LiPuma J J, Speert D P. Identification of Burkholderia cepacia from patients with cystic fibrosis and use of a new selective medium. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:614–619. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.614-619.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hobson R, Gould I, Govan J. Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia as a cause of brain abscesses secondary to chronic suppurative otitis media. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:908–911. doi: 10.1007/BF01691499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchison M L, Poxton I R, Govan J R W. Burkholderia cepacia produces a hemolysin that is capable of inducing apoptosis and degranulation of mammalian phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2033–2039. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2033-2039.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson W M, Tyler S D, Rozee K R. Linkage analysis of geographic and clinical clusters in Pseudomonas cepacia infections by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and ribotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:924–930. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.924-930.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen G Y, Stull T L, Burns J L. Marked phenotypic variability in Pseudomonas cepacia isolated from a patient with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:788–792. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.788-792.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewenza S, Conway B, Greenberg E P, Sokol P A. Quorum sensing in Burkholderia cepacia: identification of the LuxRI homologs CepRI. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:748–756. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.748-756.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LiPuma J J, Mortensen J E, Dasen S E, Edlind T D, Schidlow D V, Burns J L, Stull T L. Ribotype analysis of Pseudomonas cepacia from cystic fibrosis treatment centres. J Pediatr. 1988;113:859–862. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LiPuma J J. Burkholderia cepacia—management issues and new insights. Clin Chest Med. 1998;19:473–486. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahenthiralingam E, Campbell M E, Henry D A, Speert D P. Epidemiology of Burkholderia cepacia infection in patients with cystic fibrosis: analysis by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2914–2920. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2914-2920.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahenthiralingam E, Simpson D A, Speert D P. Identification and characterization of a novel DNA marker associated with epidemic strains of Burkholderia cepacia recovered from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:808–816. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.808-816.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahenthiralingam E, Bischof J, Byrne S K, Vandamme P. Molecular speciation of Burkholderia cepacia complex strains recovered from patients with cystic fibrosis. Ped Pulmonol. 1998;17(Suppl.):307. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenney D, Brown K E, Allison D G. Influence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoproducts on virulence factor production in Burkholderia cepacia: evidence of interspecies communication. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6989–6992. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6989-6992.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Millar-Jones L, Ryley H C, Paull A, Goodchild M C. Transmission and prevalence of Burkholderia cepacia in Welsh cystic fibrosis patients. Respir Med. 1998;92:178–183. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Revets H, Vandamme P, Van Zeebroeck A, De Boeck K, Struelens M J, Verhaegen J, Ursi J P, Verschraegen G, Franckx H, Malfroot A, Dab I, Lauwers S. Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia and cystic fibrosis: the epidemiology in Belgium. Acta Clin Belg. 1996;51:222–230. doi: 10.1080/22953337.1996.11718514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodley P D, Römmling U, Tümmler B. A physical genome map of the Burkholderia cepacia type strain. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:57–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17010057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sajjan U S, Sun L, Goldstein R, Forstner J F. Cable (Cbl) type II pili of cystic fibrosis-associated Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia: nucleotide sequence of the cblA major subunit pilin gene and novel morphology of the assembled appendage fibers. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1030–1038. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.1030-1038.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson I N, Finlay J, Winstanley D J, Dewhurst N, Nelson J W, Butler S L, Govan J R W. Multi-resistant isolates possessing characteristics of both Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia and Burkholderia gladioli from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:353–361. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Speert D P, Bond M, Woodman R C, Curnutte J T. Infection with Pseudomonas cepacia in chronic granulomatous disease: role of nonoxidative killing by neutrophils in host defence. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1524–1531. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.6.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanier R Y, Palleroni N J, Doudoroff M. The aerobic pseudomonads: a taxonomic study. J Gen Microbiol. 1966;43:159–271. doi: 10.1099/00221287-43-2-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandamme P, Holmes B, Vancanneyt M, Coenye T, Hoste B, Coopman R, Revets H, Lauwers S, Gillis M, Kersters K, Govan J R W. Occurrence of multiple genomovars of Burkholderia cepacia in cystic fibrosis patients and proposal of Burkholderia multivorans sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1188–1200. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Laer F, Raes D, Vandamme P, Lammens C, Sion J P, Vrints C, Snoeck J, Goossens H. An outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia with septicemia on a cardiology ward. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998;19:112–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West S E, Schweizer H P, Dall C, Sample A K, Runyen-Janecky L J. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1994;148:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whiteford M L, Wilkinson J D, McColl J H, Conlon F M, Michie J R, Evans T J, Paton J Y. Outcome of Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia colonization in children with cystic fibrosis following a hospital outbreak. Thorax. 1995;50:1194–1198. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.11.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]