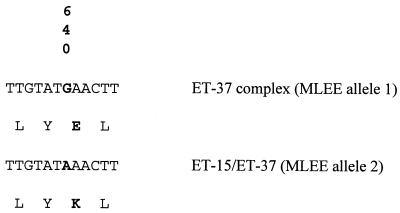

The species Neisseria meningitidis comprises a large variety of genetically different clones, which are defined either by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) (2) or by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (5) of housekeeping genes. One cluster of related clones causing predominantly epidemic serogroup C disease, i.e., the electrophoretic type 37 (ET-37) complex, has been defined by MLEE. A particular clone of the ET-37 complex, ET-15, arose several years ago in Canada (1, 6) and has spread worldwide since then (4). ET-15 meningococci tend to be more virulent than other members of the ET-37 complex, and attack and fatality rates, as well as the proportion of sequelae, have been reported to exceed the rates observed for other members of the ET-37 complex (3, 4, 6). Therefore, attempts to distinguish ET-15 from other clones of the ET-37 complex have been made to guide public health actions undertaken in case of outbreaks of ET-15 disease. Until now, ET-15 meningococi could be solely identified by MLEE, because this new clone differed by a rarely occurring FumC allele (FumC2) from most other ET-37 complex strains, which express a FumC1 allele (1). However, the use of MLEE is restricted to a few specialized laboratories worldwide. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) using the enzyme SpeI revealed restriction patterns which are specific to ET-15 (J. Jelfs, R. Munro, F. Ashton, N. Rawlinson, and D. A. Caugant, Abstr. 11th Int. pathog. Neisseria Conf., p. 5, 1998), but PFGE is far too time-consuming to be a viable alternative to MLEE. Sequencing of the fumC gene has been added to the original MLST scheme for meningococci in order to distinguish ET-15, but no sequence information specific to ET-15 meningococci was found in the part of the gene sequenced by MLST (fumC gene position 776 to 1,230) (http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk/). We therefore compared the sequences upstream of position 776 of the fumC gene of ET-15 meningococci with those of other members of the ET-37 complex. For this purpose, the fumC gene was amplified using the primers fumC-A1 and fumC-A2 (1). The PCR product was sequenced using the primer fumC-P3 (5′-CGTAAAAGCCCTGCGCGAC-3′). At position 640 we observed a point mutation in the fumC gene of ET-15 meningococci, which showed an A instead of a G in other ET-37 complex strains. This nonsynonymous change results in the expression of a basic lysine instead of an acidic glutamate (Fig. 1). We suggest that this mutation is responsible for the different MLEE migration pattern of the ET-15 FumC. The point mutation was consistantly found in 13 ET-15 strains from various geographical origins, but not in seven ET-37 complex strains other than ET-15 (Table 1). Thus, the point mutation at posiiton 640 of the fumC gene is a clone-specific characteristic which permits the distintion of ET-15 from other ET-37 complex strains. We therefore suggest that sequencing of the fumC gene should include position 640 in order to identify this especially virulent variant.

FIG. 1.

Nonsynonymous change at position 640 in the fumC gene of ET-15 strains.

TABLE 1.

ET-37 complex strains used in this study

| Strain | Country | Yr | Clone of ET-37 complex | Position 640 of fumC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 92001 | Canada | 1992 | ET-15 | A |

| 93487 | Canada | 1994 | ET-15 | A |

| 94N266 | Australia | 1994 | ET-15 | A |

| 311671 | England | 1995 | ET-15 | A |

| 313223 | England | 1995 | ET-15 | A |

| 31648 | Finland | 1994 | ET-15 | A |

| 76365 | Finland | 1995 | ET-15 | A |

| G144/93 | Iceland | 1993 | ET-15 | A |

| II050775 | Iceland | 1993 | ET-15 | A |

| M837 | Israel | 1992 | ET-15 | A |

| M877 | Israel | 1993 | ET-15 | A |

| 11/94 | Norway | 1994 | ET-15 | A |

| 81/94 | Norway | 1994 | ET-15 | A |

| H1713 | England | 1987 | Othera | G |

| 76424 | Finland | 1995 | Other | G |

| M710 | Israel | 1991 | Other | G |

| 53/94 | Norway | 1994 | Other | G |

| 500 | Italy | 1984 | Other | G |

| 24580 | South Africa | 1996 | Other | G |

| 4575 | Australia | 1989 | Other | G |

Other than ET-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashton F E, Ryan J A, Borczyk A, Caugant D A, Mancino L, Huang D. Emergence of a virulent clone of Neisseria meningitidis serotype 2a that is associated with meningococcal gorup C disease in Canada. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2489–2493. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2489-2493.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caugant D A, Bovre K, Gaustad P, Bryn K, Holten E, Hoiby E A, Froholm L O. Multilocus genotypes determined by enzyme electrophoresis of Neisseria meningitidis isolated from patients with systemic disease and from healthy carriers. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:641–652. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-3-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson L, De Wals P. Complications and sequelae of meningococcal disease in Quebec, Canada, 1990–1994. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1159–1164. doi: 10.1086/520303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krizova P, Musilek M. Changing epidemiology of meningococcal invasive disease in the Czech republic cause by new clone Neisseria meningitidis C:2a: P1.2(P1.5), ET-15/37. Cent Eur J Public Health. 1995;3:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maiden M C, Bygraves J A, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell J E, Urwin R, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zurth K, Caugant D A, Feavers I M, Achtman M, Spratt B G. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whalen C M, Hockin J C, Ryan A, Ashton F. The changing epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease in Canada, 1985 through 1992. Emergence of a virulent clone of Neisseria meningitidis. JAMA. 1995;273:390–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]