Summary

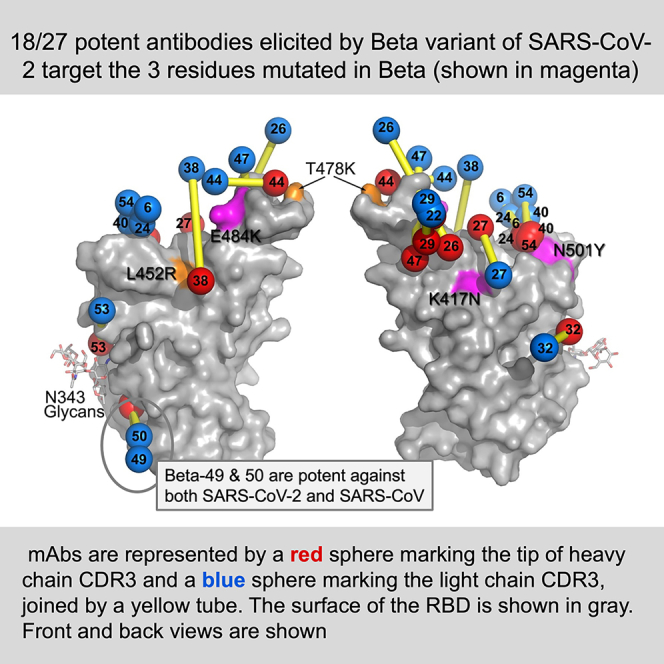

Alpha-B.1.1.7, Beta-B.1.351, Gamma-P.1, and Delta-B.1.617.2 variants of SARS-CoV-2 express multiple mutations in the spike protein (S). These may alter the antigenic structure of S, causing escape from natural or vaccine-induced immunity. Beta is particularly difficult to neutralize using serum induced by early pandemic SARS-CoV-2 strains and is most antigenically separated from Delta. To understand this, we generated 674 mAbs from Beta-infected individuals and performed a detailed structure-function analysis of the 27 most potent mAbs: one binding the spike N-terminal domain (NTD), the rest the receptor-binding domain (RBD). Two of these RBD-binding mAbs recognize a neutralizing epitope conserved between SARS-CoV-1 and -2, while 18 target mutated residues in Beta: K417N, E484K, and N501Y. There is a major response to N501Y, including a public IgVH4-39 sequence, with E484K and K417N also targeted. Recognition of these key residues underscores why serum from Beta cases poorly neutralizes early pandemic and Delta viruses.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Beta variant, immune responses, spike protein, antibody, receptor-binding domain, structure, vaccine, neutralization

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Generated 674 antibodies from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 Beta variant

-

•

18 of 27 most potent mAbs target the 3 mutations in Beta RBD

-

•

A major response to N501Y includes a public IgVH4-39 sequence

-

•

Two antibodies recognize a neutralizing epitope conserved between SARS-CoV-1 and -2

Liu et al. generated 674 antibodies from patients infected with the SARS-CoV-2 Beta variant. 18 out of 27 most potent neutralizing antibodies isolated target the 3 mutations present in the receptor-binding domain of this variant. This underscores the poor neutralization by Beta serum of early pandemic and Delta viruses.

Introduction

Genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 has identified many thousands of mutations in structural and non-structural proteins (COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) consortium, 2020). However, toward the end of 2020, viral variants were described that rapidly became the dominant strains locally and led to global spread and their designation as variants of concern (VoCs) Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta. All of these variants contain multiple mutations in S and include changes in the receptor-binding domain (RBD), N-terminal domain (NTD), and in some cases the furin cleavage site between S1 and S2. The RBD mutations found in Alpha (N501Y), Beta (K417N, E484K, and N501Y), Gamma (K417T, E484K, and N501Y), and Delta (L452R and T478K) are located in or closely adjacent to the ACE2-interacting surface where they have the potential to modulate ACE2 interaction or disrupt the binding of neutralizing mAbs. Increased affinity for ACE2 has been demonstrated for Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta (7-, 19-, 19-, and 2-fold, respectively) (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021b; Liu et al., 2021; Supasa et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021) and may play a role in increasing viral transmissibility.

A number of studies show vaccine efficacy against Beta to be reduced, and this corresponds with significantly reduced neutralization titers to Beta using serum obtained from early pandemic cases or vaccinees, when compared with neutralization of early pandemic strains (Madhi et al., 2021; Shinde et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). The RBD mutations present in Beta (K417N, E484K, and N501Y) disrupt the binding of a number of potent neutralizing mAbs including some being developed for clinical use and likely, together with changes in the NTD, explain the antigenic distance between Beta and early SARS-CoV-2 strains (Zhou et al., 2021).

To understand the antigenic landscape of Beta, we produced a substantial panel of mAbs isolated from memory B cells of convalescent Beta cases. Of 674 mAbs generated from 5 donors 27 showed potent neutralizing activity (50% focus reduction neutralization assay [FRNT50] < 100 ng/mL). Neutralization assays against a variety of viral isolates indicated most mAbs showed restricted neutralization of a set of strains. A detailed structure-function analysis comprising 22 X-ray and cryo-EM structures is presented for 16 Fabs most in complexes with RBD or S, which allows an understanding of the changes in antigenicity of the Beta S protein. The majority of potent mAbs are directed to the mutations present in the Beta RBD, principally N501Y, and E484K, underscoring the small antigenic distance between Beta and Gamma, the larger distance between early pandemic strains and Beta, and interestingly, few anti-Beta mAbs can neutralize Delta, consistent with the extreme antigenic distance between Beta and Delta (Liu et al., 2021).

Results

Generation of mAbs from Beta-infected cases

We collected plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from 18 volunteers in the UK who had previously suffered infection with Beta as evidenced by viral sequencing or were inferred to have suffered Beta as they became infected after being isolated following contact with a proven Beta-infected case. Samples were taken 4–8 weeks following Beta infection, ELISA binding assays against full-length Beta S protein and FRNT assays were performed, and 5 cases with the highest titers were selected for further study (Figure 1A). For these selected cases, as expected, FRNT50 titers were higher for Beta than Victoria (an early Wuhan related viral isolate) (Figure 1B).

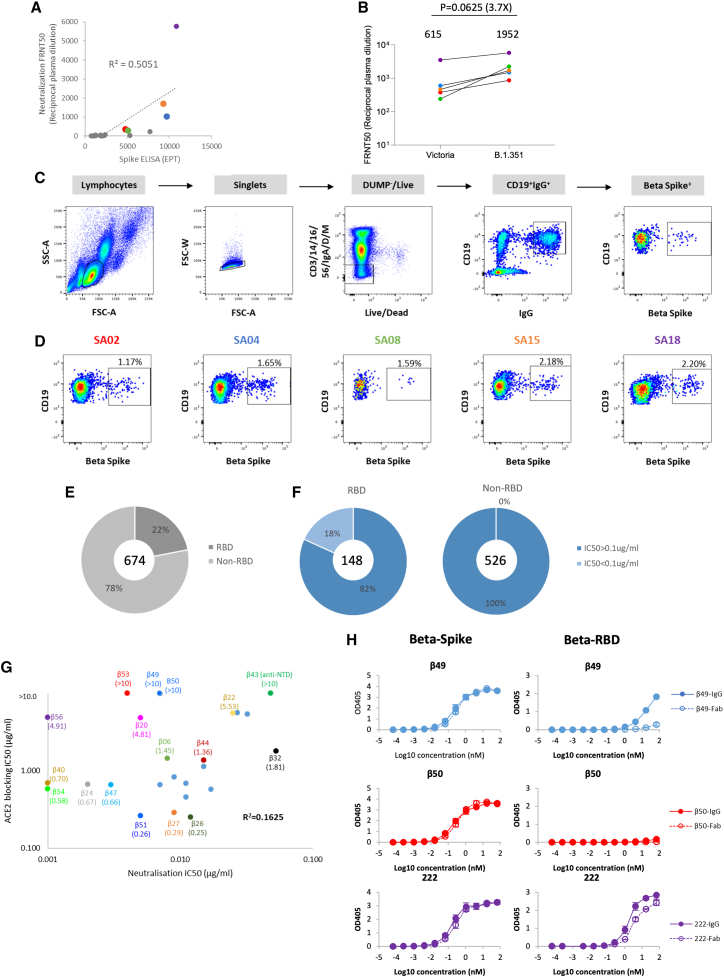

Figure 1.

Isolation and characterization of Beta SARS-CoV-2-specific mAbs

(A) Comparison of Beta SARS-CoV-2 neutralization and S binding ELISA by convalescent plasma from confirmed Beta SARS-CoV-2 infected donors. Plasma samples with FRNT50 >1:250 are highlighted and correspond to the cases shown in (D).

(B) Neutralization titers against SARS-CoV-2 strain Victoria and the Beta variant for the 5 selected plasma samples with potent neutralizing properties, analysis used the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test and two-tailed p values were calculated; geometric means are indicated above each column.

(C) Schematic of the Beta SARS-CoV-2 mAb isolation strategy.

(D) Antigen-specific single B cells were isolated using labeled recombinant S protein as bait. The frequency of S-reactive IgG+ B cells was measured by FACS.

(E) Epitope mapping of Beta SARS-CoV-2 specific mAbs against S and RBD were evaluated by ELISA.

(F) Neutralization potencies (IC50) between anti-S (non-RBD) and anti-RBD mAbs against authentic Beta SARS-CoV-2 using a FRNT50 test.

(G) Comparison of IC50 values for ACE2 binding and FRNT50 titers for the 27 potent mAbs, those selected for further structural study are highlighted.

(H) Binding of Beta-49 and -50 Fab and IgG1 to Beta S trimer or Beta RBD measured by ELISA, comparison is made with binding of mAb 222, data are shown as mean ± SEM. See also Table S1A.

To isolate memory B cells, PBMC were stained with full-length double Strep tagged Beta S, and IgG+ B cells binding Beta S were single cell sorted (Figures 1C and 1D). IgVH and IgVL sequences were isolated by RT-PCR and full-length heavy chain (HC)- and light chain (LC)-expressing plasmids were created using a Gibson assembly reaction. Assembly products were transfected into HEK-293T cells in 96-well plates, and supernatants harvested and tested in neutralization assays against Beta virus at a final concentration of 0.1–1 μg/mL. Only those mAbs achieving >90% neutralization in this initial assay were selected for further study. In total, we obtained 674 Beta-specific mAb IgGs. Of these, 22% bound RBD epitopes, 78% bound to non-RBD epitopes, and 18% of the RBD-specific mAbs achieved >90% neutralization and were selected for further study (Figures 1E and 1F). Most were able to block ACE2 binding to S, although there were exceptions: mAb Beta-43, the single NTD-binding neutralizing antibody (Figure S1A), extremely potent RBD-binding mAb Beta-53 and potent but very weakly RBD-binding mAbs Beta-49 and -50 (Figures 1G and 1H).

Cross reactivity of Beta-reactive mAbs

We performed live virus neutralization assays using the following viruses, containing the indicated changes in the RBD: Victoria (an early Wuhan related strain), Alpha (N501Y), Beta (K417N, E484K, and N501Y), Gamma (K417T, E484K, and N501Y), Delta (L452R and T478K), Alpha+E484K (E484K and N501Y), and B.1.525 (E484K) (Figures 2A–2F; Table S1A).

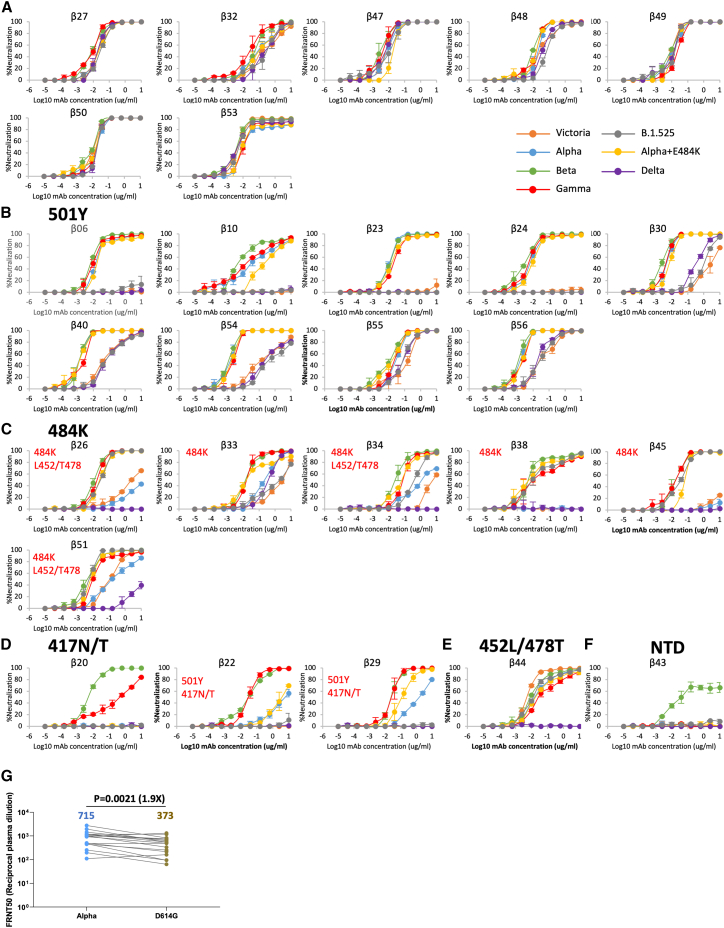

Figure 2.

Cross reactivity of Beta-specific mAbs

(A–F) Neutralization assays performed against Victoria, Alpha (N501Y), Beta (K417N, E484K, and N501Y), Gamma (K417T, E484K, and N501Y), Delta (L452R and T478K), Alpha+E484K (E484K and N501Y), and B.1.525 (E484K) live viral isolates with 27 potent Beta-specific mAbs. Titration curves are shown and mAbs grouped depending on the patterns of cross reactivity between the viral variants, potential binding determinants are indicated for the mAbs that show differential neutralization between isolates. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (A) Fully cross-reactive mAbs, (B) N501Y-dependent mAbs, (C) E484K-dependent mAbs, (D) K417N/T-dependent mAbs, (E) L452R/T478K-dependent mAbs, and (F) a single NTD-binding mAb. FRNT50 values are reported in Table S1.

(G) FRNT50 titers of 17 Alpha convalescent sera against Alpha and B.1 (D614G), analysis used the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank sum test, and two-tailed p values were calculated; geometric means are indicated above each column. See also Figure S1.

Many mAbs showed extremely potent neutralization of Beta, with FRNT50 down to 1 ng/mL (Table S1A). Cross reactivity between the different viral variants was mixed, some mAbs such as Beta-27, -32, -47, -48, -49, -50, and -53 showed full cross reactivity with <10-fold difference between FRNT50s (Figure 2A). A large group of mAbs (Beta-6, -10, -23, -24, -30, -40, -54, -55, -56) showed good neutralization of Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Alpha+ viruses, with either reduced or completely absent neutralization of Victoria, B.1.525 (E484K), and Delta viruses (Figure 2B). Alpha, Beta, and Gamma have a single mutation in common, N501Y, and we propose that the presence of the N501Y mutation creates an epitope for RBD recognition in Beta infection.

The E484K mutation disrupts the binding of many potent mAbs generated from cases infected with early pandemic viruses, and we expected Lys-484 to be recognized by Beta-neutralizing mAbs (Zhou et al., 2021). Six mAbs show evidence of Lys-484 interaction (Beta-26, -33, -34, -38, -45, and -51), with reduced activity to Alpha, but regaining activity on Alpha+484K (Figure 2C). Three mAbs, Beta-20, -22, and -29 showed maximum activity toward Beta and Gamma, suggesting that they recognize an epitope related to the K417N/T changes in Beta and Gamma, respectively. mAbs Beta-22 and -29 showed some neutralization of Alpha and Alpha+484K suggesting that they recognize an epitope comprised of Asn/Thr 417 + Tyr-501 (Figure 2D). Four mAbs (Beta-26, -34, -44, and -51) showed selective loss of neutralization to Delta (FRNT50 > 10μg/mL). We propose Beta-44 is sensitive to L452R/T478K mutations while Beta-26, -34, and -51 recognize an epitope composed of Glu-484 + Leu-452/Thr-478 (Figures 2C and 2E). Finally, the single potent NTD-binding mAb Beta-43 was completely specific for Beta (Figures 2F and S1A).

We have previously looked at the neutralization of a panel of VoCs using serum collected from cases infected with Alpha (Supasa et al., 2021) and found that following Alpha infection, the response formed is quite cross-reactive between variant viruses. Paradoxically, we found that Alpha serum neutralized Victoria as efficiently as Alpha, which would not be expected if the response to Tyr501 in Alpha infection was similar to that seen in Beta infection. However, Alpha also contains the mutation D614G, which is not found in Victoria/Wuhan, we therefore went back and tested neutralization of a version of the early pandemic virus (B.1) containing the additional D614G mutation, using 17 Alpha sera. The neutralization titer of B.1 by Alpha serum was reduced 1.8-fold compared with the neutralization titer of Alpha using Alpha serum (p = 0.0208) (Figure 2G), consistent with some Tyr501 responses in Alpha serum.

Antibody gene usage

IgVH and IgVL gene usages for the 27 potent RBD-binding, Beta-reactive mAbs are shown in Figure 3A with the individual mAb and patients from whom they were isolated shown in Table S1B. The 7 fully cross-reactive mAbs came from diverse IgVH families, apart from Beta-49 and -50, which were IgVH1-69. Beta-27 is from the IgVH3-53 gene family, which generates a public response to RBD, highly represented in repertoires isolated from individuals infected with early pandemic strains (5/20 potent mAbs FRNT50 < 100 ng/mL in our previous studies [Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a]), but was only represented once in this set. Likewise, Beta-47 belongs to a public gene family, IgVH1-58, found in a number of potent mAbs isolated from early pandemic infections (4/20 in our previous studies).

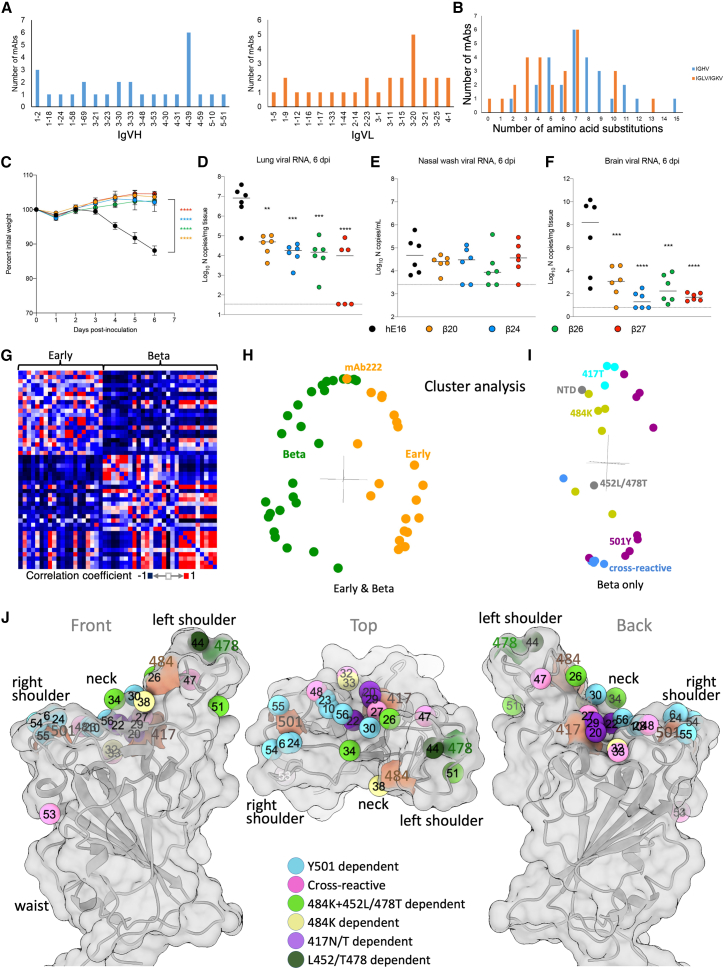

Figure 3.

Gene usage, therapeutic use in K18-hACE2 mice, and computational analysis of responses

(A) IgVH and IgVL gene usage for the 27 potent mAbs.

(B) Amino acid substitutions in IgVH and IgVL for the 27 potent mAbs.

(C–F) 8-week-old female K18-hACE2 transgenic mice were administered 103 FFU of SARS-CoV-2 Beta strain by intranasal inoculation. One day later, mice received a single 10 mg/kg dose of the indicated mAb treatment by intraperitoneal injection. Tissues were collected at 6 dpi. (C) Weight change following infection with SARS-CoV-2 (mean ± SEM; n = 6 mice per group, two experiments; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test of area under the curve: ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). Viral RNA levels in the lung (D), nasal wash (E), and brain (F) (line indicates median; n = 6 mice per group, two experiments; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test with comparison to control mAb: ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p = 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Dotted line indicates the limit of detection of the assay.

(G) Cross-correlation matrix showing agreement of neutralization titers for mAbs against seven variants of SARS-CoV-2. Every antibody is associated with a vector containing the residual neutralization titer after subtracting the mean for each variant and normalizing to a standard deviation of 1.

(H–J) Each point (I and J) in the matrix is colored according to the dot product between vectors for antibody (I and J). (H) Major modes of variation after singular value decomposition of the matrix in (G). (I) Major modes of variation after singular value decomposition of a matrix similar to (G) but calculated for Beta mAbs and colored according to their designation as a fully cross-reactive, 501Y-specific, 484K-specific, or 417T-specific antibody. (J) Mapping of the Beta mAbs based on BLI competition measurements (STAR Methods; Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a). The mean positions of the mAbs are shown as spheres. Numbers match the antibody definitions in Tables S1A and S1B (βs omitted for clarity), colored by one aspect of the serological properties e.g., Y501-dependent indicates potent neutralization is only observed for those viruses with Tyr-501. Anatomical terms relate to the torso analogy (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a). The RBD is shown as a semi-transparent surface with cartoon embedded. The outer two are related by 180° rotation about the vertical axis, and the central view is related to the “front” view by a 90° rotation about the horizonal axis. See also Figure S2 and Table S1B.

Tyr-501-reactive mAbs were the most represented, with 11/27 examples. In 9 of these, Tyr-501 was dominant, and in a further 2 (Beta-22 and -29), Tyr-501 played a role in addition to Asn-417. 6/11 of the Tyr-501-reactive mAbs used IgVH 4-39 (Beta-6, -10, -23, -40, -54, and -55), making IgVH4-39 a public antibody response following Beta infection, partly explaining the repositioning of the response toward Tyr501 relative to early pandemic strains (Yuan et al., 2020a). In our antibody panel generated from early pandemic cases 0/20 potent mAbs were IgVH4-39 compared with 6/27 in the Beta set (p = 0.0241, two-proportion Z test). The six Lys-484-reactive mAbs came from diverse IgVH backgrounds, whereas 2/3 of the Asn/Thr-417 + Tyr-501-reactive mAbs were VH3-30.

The 27 Beta-reactive mAbs showed relatively low levels of somatic mutations with median 7 changes in IgVH and IgVL (Figure 3B), which is consistent with the low level of hypermutation seen when analyzing mAbs following infection with early pandemic strains (median IgVH = 5 and IgVL = 3) (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a; Rogers et al., 2020).

In summary, potent mAbs derived from Beta-infected cases differ considerably in their cross reactivity between variant viruses compared with mAbs isolated from early convalescent cases. The Tyr-501 and Lys-484 epitopes dominate the response leading to failure of a number of mAbs to neutralize Victoria and Delta, which underscores the antigenic distance between these viruses and Beta (Liu et al., 2021). Neutralization of Delta is further impaired by a subset of mAbs that are sensitive to the RBD mutations in Delta, explaining why Beta and Delta (and Gamma/Delta) occupy the most distant positions on an antigenic map (Liu et al., 2021).

Potent mAbs protect against Beta infection in mice

To test the activity of mAbs elicited against Beta in vivo, we utilized a human ACE2 transgenic mouse model (McCray et al., 2007; Winkler et al., 2020). Four representative mAbs from different epitope classes were selected: Beta-20, which recognizes the K417N/T mutation and can potently neutralize Beta and to a lesser extent Gamma, Beta-24, which is specific to the N501Y mutation present in Alpha, Beta, and Gamma, Beta-26, which recognizes the E484K mutation found in Beta and Gamma, and Beta-27, the IgVH3-53 fully cross-reactive mAb, which neutralizes all variants similarly.

Mice were inoculated with 103 FFU of Beta and at 24 h post-inoculation, were administered a single 10 mg/kg dose of mAb via intraperitoneal injection. All four Beta-elicited mAbs, but not an isotype control mAb (hE16), prevented weight loss over the 6 days following inoculation and reduced viral loads in the lung and brain but not in nasal washes (Figures 3C–3F). These results demonstrate that each of the mAbs we tested can efficiently reduce the severity of infection and prevent systemic disease but do not prevent viral infection in the upper respiratory tract.

Quantitative dissection of similarities and differences in mAb responses

The 27 potent RBD-binding Beta mAbs appeared markedly different compared with the 20 potent mAbs we generated following infection with early pandemic strains. To quantify this, we devised a neutralization-correlation method, comparing the neutralization results for mAbs against seven virus strains between all possible pairs of the 47 potent mAbs. The metric for the comparison was the correlation coefficient between the neutralization results for the two mAbs (see STAR Methods). Displaying this as a heat matrix (Figure 3G) reveals clear differences between the Beta and early pandemic mAbs. Cluster analysis effectively separated the two sets (Figure 3H), demonstrating that the pattern of strain neutralization is similar within but different between the two sets. This segregation is highly significant (p < 0.00001 for the Mann-Whitney U test) confirming distinct patterns of strain neutralization specific to the eliciting virus. Further cluster dissection of the Beta mAbs (Figure 3I) segregates them according to their specificities to the individual RBD mutations described in Figures 2A–2F.

Mapping of mAbs binding using BLI

We have previously built a high-resolution 3D map, consistent with X-ray structure determination, of early pandemic mAbs binding to the RBD using biolayer interferometry (BLI) (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a). We therefore acquired a matrix of pairwise BLI measurements on 23 of the 26 most potent RBD-binding Beta mAbs and some pre-pandemic mAbs of known binding position. Combining the BLI data with precise structural information provided reliable mapping information on their positioning on the RBD (prediction for 7 mAbs Beta-6, -22, -24, -27, -44, -53, and -54 were in error by on average 2 Å). The mAbs do not segregate into epitopes, rather cluster analysis (STAR Methods) shows that they nearly all fall in an arc (Figure S2), spanning the neck and shoulders of the RBD (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a) (Figure 3J).

There is an excellent correlation with the critical residue assignments made above (Figure 3J). For example, Beta-44, sensitive to L452R/T478K mutations, is perched adjacent to residue 478, while mAbs, Beta-20, -22, and -29 suggested to recognize an epitope related to residue 417 are tightly clustered atop this residue. Interestingly, mAbs Beta-49 and -50 showed very low affinity to Beta RBD, although they bound tightly to full-length S (Figure 1H) and hence could not be mapped.

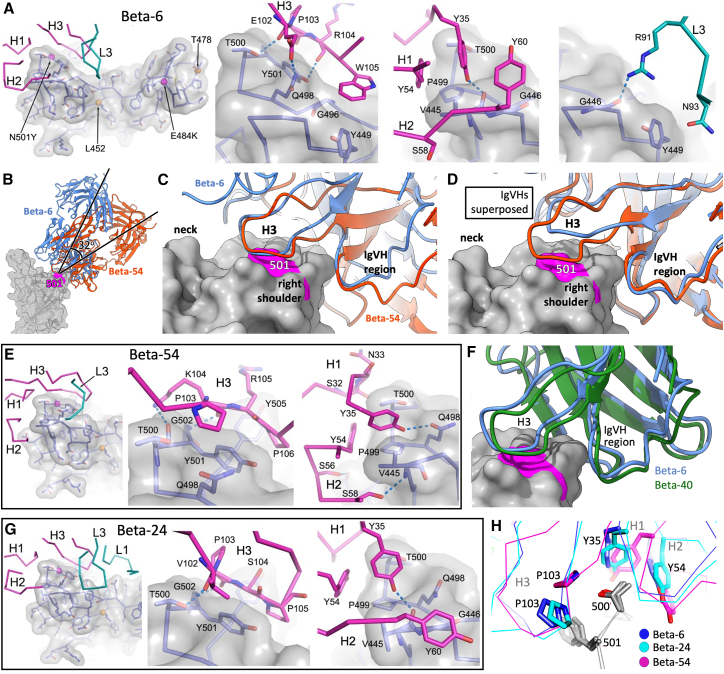

Structures of anti-Beta Fab/RBD complexes

Structural analyses were performed for representative potent anti-Beta mAbs, selected for their serological properties. Crystal structures were determined for complexes of RBD with 15 different Beta Fabs: 6, 22, 24, 27, 29, 38, 40, 44, 47, 49, 50, 53, and 54, the Beta-43/NTD complex (Figure 4A), and also for Fab Beta-32 alone (Figure 4B), at resolutions between 1.7 and 4.0 Å (STAR Methods; Table S2). In addition, cryo-EM structures were obtained for eight Beta S complexes, with Fabs of Beta-6, -26, -32, -43, -44, -49, -50, and -53, plus Beta S complexed with Fab of cross-reactive mAb-222 identified earlier (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021b) (Figures 4C and S4; STAR Methods).

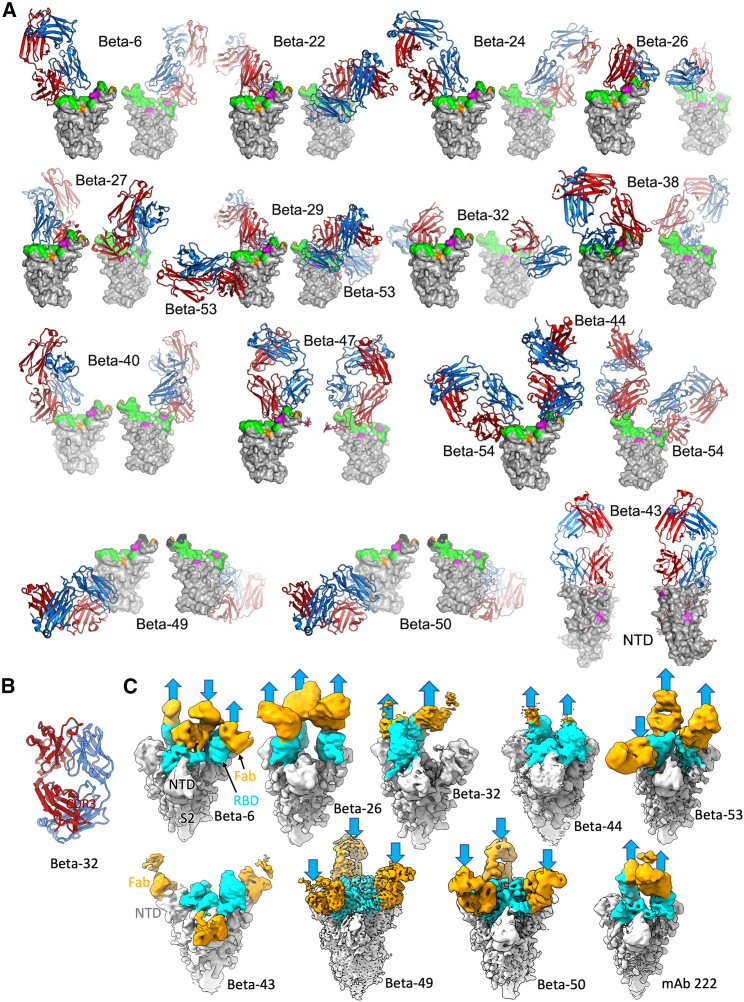

Figure 4.

Overall structures of Beta RBD/Beta S complexes with Beta mAb Fabs reported in this paper

(A) Front and back views of Beta RBD/Beta Fab complexes. Fabs drawn as ribbons with HC red and LC blue, and RBDs as gray surfaces with ACE2 footprint in green, mutation sites of the Beta variant in magenta and Delta variant in orange. All structures were crystallographic except Beta-26 and -32, which were derived by cryo-EM.

(B) Crystal structure of Beta-32 Fab with HC red and LC blue.

(C) Cryo-EM maps of Beta S complexes with Beta-6, -26, -32, -44, -53, -43, -49, and -50 and early pandemic mAb-222 Fabs. The bound Fabs are orange, RBD domains cyan, and the rest of S gray. Arrows indicate the RBD orientations. See also Figure S3 and Tables S2 and S4.

Structural definition of IgVH4-39 public mAbs against the Tyr-501 RBD

We determined structures for Beta-6 and Beta-54 of the widely used IgVH4-39 gene family. Both interact strongly with Tyr-501. Beta-6 perches atop the right shoulder of the RBD (Figure 5A), with principal contacts contributed by the HC (520 Å2), while the LC makes very few contacts (124 Å2), limited to LC CDR3 (L3) (Figure 5A). The interaction area is relatively small, with interactions heavily focused around residue Tyr-501 (Figure 5A) with the three HC CDRs (H1-3) wrapping around the right shoulder. In particular, the hydroxyl group of Tyr-501 makes a hydrogen bond to the H3 main chain (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Structural details of IgVH4-30 and IgVH4-39 Beta Fab complexes

(A) Beta-6, Beta-RBD interactions. Left panel shows interacting CDRs (HC magenta, LC cyan) with the Beta-RBD (semi-transparent gray surface, side chains as blue sticks, mutation sites of Beta [magenta] and Delta [orange] variants shown as spheres). Interactions of H3, H2, H1, and L3 loops are shown in the adjacent panels.

(B) Comparison of binding orientations for Beta-6 (blue) and Beta-54 (red).

(C) Closeup of (B) showing engagement of CDR-H3s with Tyr-501 (magenta).

(D) Same as (C) but IgVHs are overlapped instead of RBDs.

(E) Interactions of Beta-54 with Beta RBD.

(F) Comparison of binding modes of Beta-40 IgVH (green) and Beta-6 (Blue).

(G) Interactions of Beta-24 with Beta RBD.

(H) Common features of the engagement used by Beta-6 (blue), -24 (cyan), and -54 (magenta). Y35 of CDR-H1 and Y54 of CDR-H2 are conserved among the IgVH4-30 and IgVH4-39 Beta mAbs reported here. See also Tables S2 and S3.

Beta-54 has a significantly different angle of attack on the RBD compared with Beta-6 (Figure 5B), with the Fab pivoting by 32° around residue 501 on the RBD. This change in binding pose appears to derive from the difference in length of the H3 (15 residues in Beta-6, 18 in Beta-54). Altering the pose allows the different length H3 loops to make similar contacts (Figure 5C), while the H1 and H2 contact regions pivot round. Superposition of the IgVH portions (Figure 5D) shows that, with the exception of H3, the HC variable domains are very similar, although details of the interaction with the RBD differ (Figures 5A and 5E). Residues Tyr-35 (H1) and Tyr-54 (H2) are central in allowing the pivoting and characteristic of the IgVH4-39 gene family (they are also found in some other IgVH families and insufficient to convey this binding mode alone, Figure 5E; Table S3). Overall, the HC interaction area is similar for both mAbs (461 and 54 Å2 for the HC and LC, respectively, of Beta-54).

Beta-6 and -54 are examples of the two classes of IgVH4-39 Beta mAbs, with the shorter loop Beta-6-like mAbs forming the major class (Table S3). We suggest that the two distinct classes of H3 are accommodated by some degeneracy in the H1 and H2 interactions although related interactions in the IgVH4-39 portions are maintained (considering all interacting residues of both antigen and antibody, 22 are common between the two mAbs, out of 28 in Beta-6 and 34 in Beta-54).

As a test of the proposal that for IgVH4-39 mAbs H3 length modulates binding pose, a further low-resolution X-ray structure was determined for Beta-40 Fab bound to Beta RBD. Beta-40 has the canonical 15 residue H3 found in four of the IgVH4-39 mAbs, including Beta-6. As predicted, the angle of attack of Beta-40 is essentially identical to Beta-6 and H1H2 positioning is very similar (Figure 5F). The model is further supported by the structure of the Beta RBD/Beta-24 complex. Beta-24 belongs to the closely related IgVH4-30 gene family with H1 and H2 regions very similar to IgVH4-39 (Table S3) and a canonical H3 length of 15 residues. Beta-24 has a mode of engagement essentially identical to Beta-6 (Figures 5G and 5H), despite having a markedly different sequence within the 15-residue H3 (Table S3). While the interactions in part recapitulate those of Beta-6 there are also differences, the LC interaction area is more than doubled for Beta-24 (to 284 Å2), while the HC contacts are slightly reduced (458 Å2). Nevertheless, some common HC interactions define the similar mode of association (Figure 5H). Thus, the hydroxyl group of Tyr-35 forms a hydrogen bond with the RBD carbonyl oxygen of Val-445 and the carbonyl of residue Val-102 interacts with the RBD hydroxyl of Thr-500. However, the interactions with Tyr-501 differ, with a hydrogen bond formed in Beta-6, compared with hydrophobic stacking interactions in Beta-24. Interestingly, the LC interactions are not homologous—in both mAbs a hydrogen bond is formed to the carbonyl of Gly-446; however, in Beta-6 this is contributed by the guanidinium group of Arg-91 (Figure 5A), while in Beta-24 the hydrogen donor is the hydroxyl group of Tyr-91.

To investigate IgVH4-39 antibody binding in the context of the complete S trimer, the Beta S/Beta-6 Fab complex structure was determined by cryo-EM, which showed attachment in a standard way with 2 RBDs in the up configuration; however, all three RBDs bear bound Fabs (Figure 4C). In summary, the recurrent use of IgVH4-39 appears to signal a frequent public binding mode targeting residue Tyr-501, despite the mAbs harboring a wide range of different IgVL gene families (Table S1A).

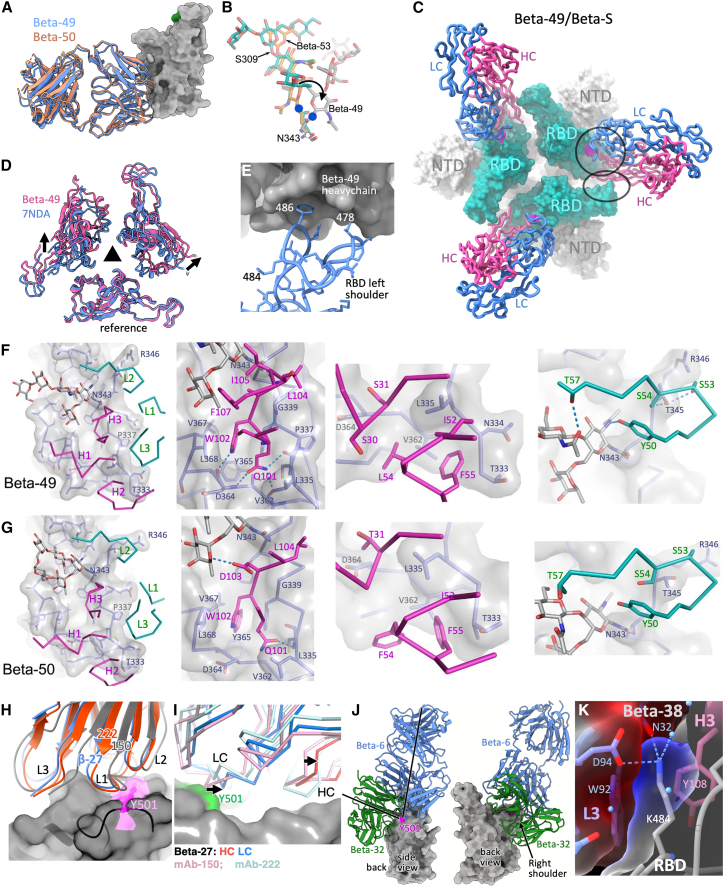

IgVH1-69 mAbs target a neutralizing epitope conserved between SARS-CoV-1 and -2

Beta-49 and -50 potently neutralized all strains of SARS-CoV-2 tested (Figure S1D), bound tightly to the full S trimer but only very weakly to the RBD and did not block binding of ACE2 (Figures 1G and 1H). Both belong to the IgVH1-69 gene family, and we determined crystal structures of Fab/RBD complexes and cryo-EM Fab/S complexes for both (STAR Methods; Tables S2 and S4; Figures 4A and 4C). The relatively high resolution (2.8 Å) of the Beta-49 Fab/S structure (Figure 4C) suggested that the complex is rather rigid. Both mAbs attach in the same configuration, despite the presence of 19 amino acid differences in the variable domain of the heavy chain (VH) alone (Figure 6A; Table S3). Their epitope lies at the “waist” region of the RBD (Torso analogy Figures 3J and S4A) harboring the N- and C-terminal junctions of RBD with the rest of S1 and includes the N- and C-terminal residues of the RBD construct (Figure S4B). The N-linked glycan attached to residue 343 of the RBD also forms part of the epitope, the sugar becoming displaced from its usual position, twisting the sidechain of N343 into an unfavorable conformation (Figure 6B). Despite the sequence variation between the two mAbs the RBD interactions are very similar and involve conserved residues. A large portion of the HC interacting area is formed by the H3 loop (375 out of 632 Å2 for Beta-49). The Fab-bound S trimer shows all three RBDs in a down configuration (Figure 4C), with the HC making interactions with two RBDs (Figure 6C), causing the RBD to be translated/rotated toward the periphery of the trimer (Figure 6D). This “down and out” orientation has not, to the best of our knowledge, been seen before. The tight packing against the second RBD forms a secondary or quaternary epitope of some 210 Å2 (Figures 6C, 6E, and S4B). This secondary 1Fab:2RBD interaction, together with the fact that the primary epitope involves residues to the very ends of the soluble RBD construct likely explains the low affinity of Beta-49 and -50 to soluble monomeric RBD (Figure S4B). The residues comprising the primary (but not the secondary) epitope (Figures 6F and 6G) are conserved between SARS-CoV-1 and -2 (Figure S4B), and we were able to show (Figure S1B) that both mAbs bind SARS-CoV-1 and -2 S to a similar degree. Finally, Beta-49 and -50 potently neutralize a SARS-CoV-1 pseudovirus (Figure S1C).

Figure 6.

Engagement of other Beta IgVH Fabs with the Beta RBD

(A) Almost identical binding of Beta-49 (blue) and Beta-50 (salmon) to the RBD.

(B) Overlay of N343 RBD glycan from the (green) (Pinto et al., 2020), Beta-53 (yellow) and Beta-49 (gray) complexes, the side chain rotated into an unfavorable conformation in the latter.

(C) Top view of the Beta-49 Fab/Beta S complex. S is shown as a surface (RBD cyan, position of glycan attachment to residue 343 magenta) while Beta-49 HC (dark pink) and LC (blue) are shown as cartoons. The HC contacts two RBDs, forming a primary (circle) and secondary (ellipse) epitope.

(D) Top view of the RBDs in all RBD down S (PDB 7NDA) and in the Beta-49 bound state. The 3-fold axis of S is shown. One RBD is superposed (reference), arrows show the movement in the other RBDs induced on binding Beta-49.

(E) Close up of the secondary epitope with some RBD residues marked.

(F) Close up of Beta-49/Beta S interaction. The RBD is shown as sticks and a surface (glycan at N343 as sticks only), and Fab as sticks colored by chain.

(G) Similar to (F) but for Beta-50.

(H and I) Comparison of the binding of Beta-27 with mAbs 150 and 222. (H) Residue 501 is highlighted on the RBD surface. (I) Side view of the right shoulder and neck of the RBD. Arrows show shifts due to repositioning the HC CDR3.

(J) Comparison of the attachment of Beta-6 and -32 to the RBD with axes (left panel) showing difference in pose.

(K) K484 is enclosed by the Beta-38 HC and LC CDR3s. See also Figure S4 and Tables S2 and S4.

Limited use of cross-reactive members of the IgVH3-53/3-66 gene family

In contrast to the extensive use of public IgVH gene families to target Tyr-501, the well-known IgVH3-53/3-66 public antibody class (frequently elicited by the early pandemic virus) is represented by only Beta-27 in the set of most potent Beta neutralizers. This is explained by our previous observation that these mAbs are for the most part sensitive to mutation to Tyr at residue 501 of the RBD, while rare changes in the LC CDR1 can confer resilience. For example, in mAb-222 isolated from individuals infected with early pandemic strains, a proline is inserted at residue 30, which can pack against the Tyr-501 without the clashes engendered by most L1 sequences (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021b) allowing it to effectively neutralize all variants. The cryo-EM structure of Fab-222/Beta S shows that the majority of trimeric S particles were in the “2 RBD-up” configuration, with both upward RBDs engaging with 222-Fab in the mode expected from the earlier RBD/Fab complex structure (Figures 4C and 6H; Dejnirattisai et al., 2021b). This is in-line with the RBD “up” engagement pattern seen for other IgVH3-53/S complexes (Barnes et al., 2020; Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a).

Beta-27 uses an alternative mechanism to achieve potency against all variants. The Beta-27 H3 loop is lengthened to 11 residues from the usual 9, displacing the L1 to produce enough space to allow the large tyrosine side chain at 501 found in the Alpha, Beta, and Gamma variants to be stabilized by main chain peptide interactions at residues 29 and 30, analogous to mAb-222 (Figures 6H and 6I), conferring cross reactivity against all variants. As with canonical IgVH3-53 mAbs, Beta-27 makes extensive interactions with the RBD mainly in the neck region between the shoulders (Figure 4A, 718 Å2 with the HC and 262 Å2 with the LC) (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a; Guo et al., 2021). H1-3 all contact the RBD surface in the area between, but not touching, residues 417 and 484. It appears from the relative rarity of IgVH3-53 mAbs in the anti-Beta responses, that the mAbs selected are private rather than public.

Other gene families can attach strongly at the right shoulder around residue 501 while being cross-reactive

Beta-32 is highly potent against all variants reported here. We determined the high-resolution crystal structure of the Fab and the cryo-EM structure of the Fab in complex with Beta S (Figures 4A–4C and 6J). Fab binds to two RBDs in the up configuration. Although there is some ambiguity in the mode of association, it is clear that there are strong interactions centered on residue 501. The Beta-32-binding mode is radically different to that observed for the gene families IgVH4-39 and IgVH3-53 discussed earlier. Thus, the 501 interactions are via the HC instead of the LC as seen for the IgVH3-53 mAbs, and the angle of attack of Beta-32 compared with Beta-6 is slewed ∼90° toward the back of the RBD (Figure 6J). Thus, Beta-32 has found a cross-reactive mode of engagement with the right shoulder of the RBD.

Exquisite specificity for Lys-484 can be achieved by a combination of a salt bridge and a hydrophobic cage

Beta-38 is classified by serology and BLI competition mapping as requiring Lys-484 (Figures 2C, 3I, and 3J; Table S1B). The Beta-38/Beta RBD complex structure confirms this (Figure 4A), with the antibody attacking the neck/left shoulder region from the front, achieving specificity by burying Lys-484 between the H3 and L3 loops (Figure 6K). The hydrophobic stem of the lysine side chain is contained within a hydrophobic cage composed of Phe-490 (RBD), Tyr-108 (HC), and Trp-92 (LC). At the end of the cage Asp-94 (LC) makes a salt bridge with the amino group of the lysine side chain of residue 484 (Figure 6K) and a hydrogen bond to Asn-32. There are two Fab-RBD complexes in the crystallographic asymmetric unit and the different crystal packing forces introduce a 13° difference in the angle of attack, indicating flexibility in the attachment of this highly focused antibody.

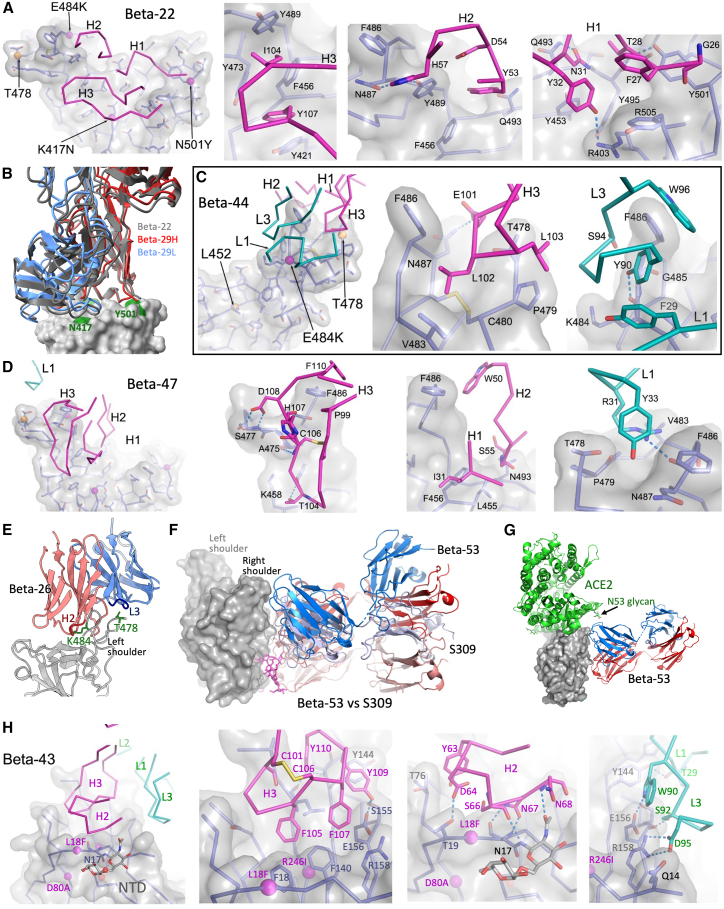

Indirect effect of mutations at RBD residue 417

Beta-22 uses IgVH3-30 and is classified serologically as targeting residue 417 (Figure 2D; Table S1B). The 417 focus is reinforced by the BLI mapping, which places the antibody almost exactly atop this residue (Figure 3J), and the crystal structure of the complex confirms this (Figures 4A and 7A). However, the binding is quite extensive, almost entirely restricted to the HC, with H1-3 contributing a total of 597 Å2 interface area (in contrast the LC contributes only 110 Å2). H1-3 are deployed so that H1 is close to residue Tyr-501, H3 wraps across Asn-417 and H2 reaches up toward residue Lys-484 (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Details of interactions of Beta-22, -29, -47, -26, -53, and -43

(A) Interactions of Beta-22 (as Figure 6A). N417 specificity is achieved indirectly.

(B) Identical binding modes of Beta-22 (gray) and Beta-29 (HC red, LC blue) IgVH3-30 mAbs.

(C) Beta-44/Beta RDB interactions.

(D) Beta-47/Beta RDB interactions.

(E) Beta-26 binds the left shoulder contacting K484 and T478 of the RBD.

(F) Beta-53 (HC red, LC blue) binds the same epitope as S309 (HC salmon, LC pale blue; PDB: 7BEP).

(G) Binding of Beta-53 relative to ACE2 receptor.

(H) Beta-43 binding to the NTD (gray surface). See also Figure S5.

The serological data shows good correlation with this (Figure 2D), H2 fails to reach Lys-484 hence this mutation has little impact on binding, whereas the N501Y mutation has a positive impact on binding but K417N/T is also required for effective neutralization. Although Asn-417 does not make direct contacts with H3 the extra size of the lysine and the concentration of positive electrostatic charge presumably combine to have a significant effect on antibody affinity. Beta-22 is glycosylated at residue Asn-35 within L1 and the sugar, as observed before, lies in the vicinity of the left shoulder (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a). There are two IgVH3-30 mAbs, isolated from different donors (Table S1B), in the set of potent Beta RBD binders, the second being Beta-29. Serology and BLI mapping suggest that Beta-29 is similar to Beta-22, and the crystal structure of the Beta-29/Beta RBD complex confirmed essentially identical binding modes (Figure 7B). Interestingly, these two mAbs also share IgVL4-1. Although we have no structural information for the third potent mAb sharing these serological properties, Beta-20, the BLI competition mapping places this mAb in an identical position and the HC gene family IgVH3-33 is closely related to IgVH3-30 (Table S3), so it is possible that the mode of engagement may be similar (although the NTD binder Beta-43 is also IgVH3-30). In summary, specificity for Asn-417 seems to be achieved indirectly, with the residue nestled at the heart of the antibody-binding site between L2 and H3. Although there are no specific high-affinity interactions, placing the residue central to the paratope renders it sensitive to the change in electrostatic charge at 417 characteristic of the Alpha, Beta, and Gamma variants, but agnostic to the residue being an asparagine or threonine. It may be that Beta-20, which is sensitive to Thr-417, makes direct contact with Asn-417.

Targeting the left shoulder can introduce sensitivity to Delta through residue 478

Beta-44 does not neutralize the Delta variant. This mAb is perched on the left shoulder making relatively small contacts via both HC and LC (408 and 123 Å2, respectively), with the HC positioned above residue 478 (Figure 4A). L1 and L3 are close to residue 484 of the RBD, making a hydrogen bond from the hydroxyl group of Tyr-90 of the L3 loop to the carbonyl oxygen of Lys-484, while H1, H2, and H3 surround residue Thr-478 (Figure 7C). Since there are no contacts close to Leu-452 of the RBD, sensitivity to Delta arises through contacts with residue 478, perhaps due to loss of hydrophobic interactions between the side chain CG1 and H3 residue Tyr-90 when residue 478 is mutated to Lys (Figure 7C). Cryo-EM analysis of the Beta-44-Fab/Beta S complex shows two RBDs in the up configuration with Fab attached (Figure 4C).

Cross reactivity can be obtained by binding the left shoulder-neck region but avoiding variant mutations

Beta-47 is cross-reactive against all variants and interacts strongly with the back of the left shoulder-neck interface (contact areas are 582 and 234 Å2 for the HC and LC, respectively) (Figures 4A and 7D). H3 makes the largest contact, in part to the back of the loop bearing 484, whereas LC contacts are to the far edge of the left shoulder, in the vicinity of, but not contacting, residue 478 (Figure 7D). Beta-47 is also glycosylated, at residue Asn-102 of H3, as for Beta-22 the sugar lies in the vicinity of the left shoulder but makes little specific contact with the RBD. Beta-47 is very similar to mAb 253 previously identified (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a), sharing the same variable genes, glycosylation, and a disulphide in the H3.

Targeting the left shoulder can produce sensitivity to changes at residues 484 and 478

MAb Beta-26 requires the Beta E484K mutation for potent neutralization but is also exquisitely sensitive to the L452R/T478K mutations found in Delta. To investigate this, we determined the cryo-EM Beta S/Beta-26 Fab structure. Unusually, S was found in a 3 RBD-up configuration with Fab attached to all three RBDs (Figure 4C). Since the experimental structure was insufficiently resolved to build the Fab structure directly, we constructed a model with Alphafold-2 (Jumper et al., 2021), and adjusted it to fit the density (STAR Methods). The major contacts are through the H1–3, with H2 making a close interaction with residue 484 (Figure 7E). In addition, there are strong interactions between L3 and 478 (Figure 7E). These interactions explain the observed serological results (Figure 2C; Table S1A).

A potently neutralizing cross-reactive epitope that does not block ACE2 binding

BLI competition analysis placed the potent cross-reacting antibody Beta-53 (Table S1A) on the upper right flank of the RBD (Figure 3J), and ELISA data showed that binding was independent of ACE2 binding (Figure 1G). The Beta-53/Beta S complex structure shows attachment to all three RBDs (2 up and one down) (Figure 4C), and higher resolution analysis of the Beta-53/Beta RBD complex confirms that the antibody attaches at an epitope overlapping that of antibody S309 identified earlier (Figure 7F; Pinto et al., 2020). There is also some overlap with the Beta-49 and -50 “waist”-binding mAbs described above (Figure S4A). Like S309, Beta-53 makes a substantial interaction with the N-linked glycan at residue N343 (Figures 6B, 6F, 6G, and 7F). Compared with S309, Beta-53 sits some 10 Å further up the RBD, toward the ACE2-binding site so that Beta-53 contacts the glycans via H1 and H3 instead of H3 and L2 in S309. It is even further from the Beta-49/Beta-50 “waist” epitope. The Fab approaches the ACE2 site and is likely to brush against the N53 ACE2 glycan (Figure 7G); however, ELISA competition data confirm that there is no significant competition with ACE2 (Figure 1G). Both the HC and LC make substantial contacts (466 and 270 Å2, respectively).

The Beta-53/Beta S complex structure determined after incubation at 20°C for 30 min may cast light on the mechanism of neutralization. Despite the incubation temperature being below physiological, a substantial fraction of S was no longer trimeric, suggesting S destruction as a potential neutralization mechanism, as proposed for other non-ACE2-competing mAbs (STAR Methods) (Huo et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2020b; Zhou et al., 2020).

A Beta-specific NTD-binding antibody

Beta-43 is the only potent non-RBD mAb described here and is highly specific to Beta S (Figure S1A). X-ray and EM analyses confirm direct interaction with the NTD, at the so-called “supersite” (Figures 4A, 4C, 7H, and S5; (Cerutti et al., 2021; McCallum et al., 2021). Of the point mutations in the NTD (L18F, D80A, D215G, and R246I) only L18F is part of the epitope. Although the epitope is slightly removed from the site of the Beta characteristic three-residue (242–244) NTD deletion, comparison of the Beta and early pandemic NTD structures reveals a knock-on change that significantly shifts part of the Beta-43 epitope, conferring Beta specificity (Figure S5). In addition to this variant-specific conformational change, there are numerous other differences between the Beta-NTD and other reported NTD structures (Figure S5), highlighting the intrinsic flexibility of this highly mutable domain.

Discussion

Following Beta infection, there is a marked shift in the profile of the antibody response compared with infection with early pandemic strains (Figures 3H and 3I), with many potent mAbs picking out the three RBD amino acid changes found in Beta; K417N (3/27 mAbs), E484K (6/27 mAbs), and especially N501Y (11/27 mAbs) (Greaney et al., 2021). This specificity underpins the antigenic difference between Beta, the other VoCs, and early pandemic strains/vaccines. Of the 27 mAbs, titers were reduced compared with Beta by 1 log, 2 logs, or knocked out (KO), respectively for Victoria (18, 15, 10), Alpha (10, 6, 5), Gamma (2, 1, 1), and Delta (18, 16, 14). These profound reductions in the neutralization potential of Beta-specific mAbs underscore the antigenic distance between Beta and early pandemic strains (10/27 mAbs KO), which is even more extreme with Delta (14/27 mAbs KO). Delta differs from Beta by 5 amino acids in the RBD (K417, L452, T478, E484, N501), while Beta and Gamma are antigenically close (1/27 mAbs KO), finally Alpha, which contains the single N501Y mutation, occupies an intermediate position (5/27 mAbs KO). These data are consistent with neutralization data using Beta and Gamma serum, which have much reduced neutralization capacity for Delta with many completely failing to neutralize Delta (Liu et al., 2021).

Part of the reason for the shift of the mAb response to Beta compared with early pandemic strains is the response to Tyr501 (11/27 mAbs). A significant portion of this is driven by the activation of a public antibody response to N501Y through IgVH4-39 (6/11 N501Y specific mAbs), and the highly similar IgVH4-30 (1/11). As expected for a public response, these mAbs engage the same epitope in a closely related way, with different lengths of H3 being accommodated by a pivoting of the antibody around residue 501, shifting the positions of the H1 and H2 loops, which appear to “rachet” between two stable sets of interactions (Figures 5B–5D; Table S1B).

Despite many mAbs derived from Beta cases showing specificity to a subset of VoCs, 6/27 mAbs showed potent neutralization of all VoCs tested (<100 ng/mL). Two of these belong to public responses that have been repeatedly isolated (mAb 27 IgVH3-53 and mAb 45 IgVH1-58). The continued, but much reduced, usage of the IgVH3-53 gene family is due to a shift in L1 abrogating a blocking interaction with Tyr-501 bearing RBDs (Figure 6H) and joins the use of a rare mutation in L1 documented previously (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021b) as a resilience mechanism against this mutation.

Another pair of potent cross-reactive mAbs (Beta-49 and -50) belong to the IgVH1-69 gene family and bind the “waist” of the RBD, to a previously undetected epitope conserved in SARS-CoV-1 (Figure S4). It is possible that the mechanism of neutralization may be to lock the RBDs in an unusual “down and out” conformation.

The potently neutralizing NTD-binding antibody, Beta-43, binds the NTD in the so-called supersite region (Cerutti et al., 2021). This antibody is specific for the Beta variant, and the Fab/NTD complex structure shows how this specificity is achieved, the three-residue deletion in Beta (Δ242–244) causes a conformation change that impacts on the supersite and will likely cause more generalized escape from supersite binders than the individual amino acid changes also found in Beta NTD (D80A, D215G, and R246F).

One potent neutralizer, Beta-53, remains a puzzle. It does not compete with ACE2, binds an epitope overlapping that of S309 (Pinto et al., 2020), and similar to S309 it interacts with the N-linked glycan at residue N343 of the RBD. The mechanism of neutralization is unclear; however, there is a suggestion from the cryo-EM of the complex of Beta-53 Fab with the trimeric S protein, that at room temperature the Fab may destabilize the prefusion state of S.

In summary, we have presented an in-depth structure-function analysis of potent mAbs from Beta-infected volunteers. Looking at potent neutralizing mAbs, the anti-Beta response is substantially repositioned toward the three mutated residues found in the Beta RBD. Differential targeting of these residues creates the large antigenic distance between Beta and early pandemic strains, which are used in current vaccines. The majority of Beta-specific mAbs fail to neutralize Delta, which is consistent with the large falls in the ability of Beta (and Gamma) infected sera to neutralize Delta (Liu et al., 2021) and reflects the fact that there are 5 amino acid differences between the RBDs of Beta and Delta. Several companies are now developing Beta booster vaccines, and it will be interesting to determine how effective they are at eliciting responses to the key mutated residues in Beta in individuals vaccinated with Wuhan related strains. Finally, it seems likely that further VoCs will occur in the future by de novo mutation or through recombination, whether we see the emergence of widespread escape from vaccines mandating a change in strategy toward polyvalent vaccination, as seen with influenza, or a search for broadly neutralizing monovalent vaccines remains to be determined.

Limitations of the study

The neutralization assays described are performed in vitro and therefore do not capture the contribution of complement or ADCC, which may augment responses in vivo. They also do not take account of T cell responses, which are not disrupted to the same degree as the antibody response by the relatively small number of mutations occurring in S compared with its overall length (1,273 amino acids), T cells may play a role in protection from severe disease (Fischer et al., 2021).

It will be interesting to survey mAb responses following Delta infection and see whether the large reductions or failure of Beta and Gamma serum to neutralize Delta is replicated when Delta serum is used to neutralize Beta and Gamma.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Fab | This paper | N/A |

| IgG | This paper | N/A |

| Human anti-NP (mAb 206) | Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a | N/A |

| Human anti-NTD (mAb407) | Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a | N/A |

| Human anti-RBD (mAb222) | Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a | N/A |

| S309 | LifeArc | N/A |

| StrepMAB-Classic | IBA Lifesciences | Cat# 2-1507-001 |

| StrepMAB Classic DY549 | IBA Lifesciences | Cat#2-1566-050 |

| Anti-Human CD3-FITC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555332 |

| Anti-Human CD14-FITC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555397 |

| Anti-Human CD56-FITC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562794 |

| Anti-Human CD16-FITC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555406 |

| Anti-Human IgM-FITC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555782 |

| Anti-Human CD19-BUV395 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 563549 |

| Anti-Human IgG-BV786 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564230 |

| Anti-IgM-APC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 551062 |

| Anti-Human IgA-FITC | Dako | Cat# F0188 |

| Anti-Human IgD-FITC | Dako | Cat# F0189 |

| Anti-Human IgG (Fab-specific)-ALP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A8542 |

| Anti-Human IgG (Fc-specific)-ALP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A9544 |

| Anti-Human IgG (Fc specific)-Peroxidase | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A0170 |

| Anti-human IgG Fc specific-FITC | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# F9512 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 (Australia/VIC01/2020) | Caly et al., 2020 | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 strain Alpha | Public Health England | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 strain Beta | Public Health England | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 strain Gamma | Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 strain Alpha+E484K | This paper | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 strain Delta | Wendy Barclay and Thushan De Silva | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2/B.1.525 | Wendy Barclay and Thushan De Silva | N/A |

| DH5α bacteria | Invitrogen | Cat# 18263012 |

| Biological samples | ||

| PBMCs from SARS-CoV-2 patients | John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford UK | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Phosphate buffered saline tablets | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat. No. P4417 |

| Sensor Chip Protein A | Cytiva | Cat#29127555 |

| Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium, high glucose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D5796 |

| Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium, low glucose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D6046 |

| UltraDOMA PF Protein-free Medium | Lonza | Cat#12-727F |

| FreeStyle™ 293 Expression Medium | Gibco | Cat# 12338018 |

| L-Glutamine–Penicillin–Streptomycin solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# G1146 |

| GlutaMAX™ Supplement | Gibco | Cat#35050061 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Gibco | Cat# 12676029 |

| TrypLE™ Express Enzyme | Gibco | Cat#12604013 |

| Trypsin-EDTA | Gibco | Cat#2259288 |

| Opti-MEM | Gibco | Cat# 11058021 |

| Polyethylenimine, branched | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 408727 |

| His-tagged SARS-CoV-2 RBD K417N, E484K, N501Y | Zhou et al., 2021 | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 Beta variant Spike | This paper | N/A |

| SARS-CoV Spike | Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a | N/A |

| His-tagged human ACE2 | Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a | N/A |

| His-tagged SARS-CoV-2 NTD | This paper | N/A |

| His-tagged SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant NTD | This paper | N/A |

| His-tagged SARS-CoV-2 beta variant NTD | This paper | N/A |

| His-tagged SARS-CoV-2 gamma variant NTD | This paper | N/A |

| His-tagged SARS-CoV-2 delta variant NTD | This paper | N/A |

| Streptavidin-APC | Biolegend | Cat# 405207 |

| RNase inhibitor | Promega | Cat# N2611 |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C4888 |

| Strep-Tactin®XT | IBA Lifesciences | Cat# 2-1206-025 |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#8787 |

| Protein G Plus/Protein A Agarose | Millipore | Cat#IP10 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Bright-Glo Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat# E2620 |

| HIV Type 1 p24 Antigen ELISA 2.0 | ZeptoMetrix | Cat# 0801002 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-6 and COVOX-45 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7PRY |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-22 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7PRZ |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-24 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7PS0 |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-27 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7PS1 |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-29 and Beta-53 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7PS2 |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-38 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7PS4 |

| Crystal structure of Beta-32 Fab | This paper | PDB: 7PS3 |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-40 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7PS7 |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-47 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7PS5 |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-44 and Beta-54 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7PS6 |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-49 and FI3A Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7Q0G |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-50 and Beta-54 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7Q0H |

| Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Beta-RBD/Beta-43 Fab complex | This paper | PDB: 7Q0I |

| CryoEM structure of COVOX-222 Fab in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Beta Spike glycoprotein trimer | This paper | EMD-13869, PDB: 7Q9G |

| CryoEM structure of Beta-49 Fab in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Beta Spike glycoprotein trimer | This paper | EMD-13857, PDB: 7Q9E |

| CryoEM structure of Beta-50 Fab in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Beta Spike glycoprotein trimer | This paper | EMD-13868, PDB: 7Q9F |

| CryoEM structure of Beta-43 Fab in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Beta Spike glycoprotein trimer | This paper | EMD-13870, PDB: 7Q9I |

| CryoEM structure of Beta-32 Fab in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Beta Spike glycoprotein trimer | This paper | EMD-13872, PDB: 7Q9K |

| CryoEM structure of Beta-26 Fab in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Beta Spike glycoprotein trimer | This paper | EMD-13871, PDB: 7Q9J |

| CryoEM structure of Beta-53 Fab in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Beta Spike glycoprotein trimer | This paper | EMD-13873, PDB: 7Q9M |

| CryoEM structure of Beta-06 Fab in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Beta Spike glycoprotein trimer | This paper | EMD-13875, PDB: 7Q9P |

| CryoEM map of Beta-44 Fab in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Beta Spike glycoprotein trimer | This paper | EMD-13874 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines and animals | ||

| HEK293S GnTI- cells | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3022 |

| HEK293 cells | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3216 |

| Expi293F™ Cells | Gibco | Cat# A14527 |

| HEK293T/17 cells | ATCC | Cat#CRL-11268 |

| HEK293T/17 cells-hACE2 | Liu et al., 2021 | N/A |

| Hamster: ExpiCHO cells | Thermo Fisher | Cat# A29133 |

| Vero cells | ATCC | Cat# CCL 81 |

| VeroE6/TMPRSS2 | NIBSC | Cat#100978 |

| Heterozygous K18-hACE C57BL/6J mice, 7-8 week-old | Jackson Laboratory | 2B6.Cg-Tg(K18-ACE2)2Prlmn/J) |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Vector: pHLsec | Aricescu et al., 2006 | N/A |

| Vector: pOPING-ET | Nettleship et al., 2008 | N/A |

| Vector: p8.91 | di Genova et al., 2020 | Nigel Temperton |

| Vector: pCSFLW | di Genova et al., 2020 | Nigel Temperton |

| Vector: pcDNA-SARS-CoV spike | Nigel Temperton | N/A |

| Vector: pcDNA-SARS-CoV-2 spike of Beta strain | This paper | N/A |

| human ACE2 cDNA | Sourcebiosciences | ID: 5297380 |

| Vector: human IgG1 heavy chain | German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany (H. Wardemann | N/A |

| Vector: human lambda light chain | German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany (H. Wardemann | N/A |

| Vector: human kappa light chain | German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany (H. Wardemann | N/A |

| Vector: Human Fab | University of Oxford, NDM (G. Screaton) | N/A |

| TM149 BirA pDisplay | University of Oxford, NDM (C. Siebold) | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Xia2-dials | Winter et al., 2018 | https://xia2.github.io/parameters.html |

| PHENIX | Liebschner et al., 2019 | https://www.phenix-online.org/ |

| COOT | Emsley and Cowtan, 2004 | https://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| Data Acquisition Software 11.1.0.11 | Fortebio | https://www.fortebio.com/products/octet-systems-software |

| Data Analysis Software HT 11.1.0.25 | Fortebio | https://www.fortebio.com/products/octet-systems-software |

| CryoSPARC v2.15.1-live | Structura Biotechnology Inc. | https://cryosparc.com/ |

| SerialEM (version 3.8.0 beta) | https://bio3d.colorado.edu/SerialEM/; Mastronarde, 2005 | N/A |

| EPU | Thermo Fisher | https://www.thermofisher.com/uk/en/home/electron-microscopy/products/software-em-3d-vis/epu-software.html |

| Prism 8.0 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Biacore T200 Evaluation Software 3.1 | Cytiva | www.cytivalifesciences.com |

| IBM SPSS Software 26 | IBM | https://www.ibm.com |

| Flowjo 10.7.1 | BD | https://www.flowjo.com |

| SnapGene software 5.3.2 | Insightful Science | www.snapgene.com |

| Other | ||

| X-ray data were collected at beamline I03, Diamond Light Source, under proposal lb27009 for COVID-19 rapid access | This paper | https://www.diamond.ac.uk/covid-19/for-scientists/rapid-access.html |

| Cryo-EM data were collected at eBIC, Diamond, under Proposal BI26983-2 for COVID-19 rapid access | This paper | https://www.diamond.ac.uk/covid-19/for-scientists/rapid-access.html |

| Cryo-EM data were collected at OPIC, Division of Structural Biology, University of Oxford | This paper | https://www.opic.ox.ac.uk/ |

| HiLoad® 16/600 Superdex® 200 pg | Cytiva | Cat. No. 28-9893-35 |

| Amine Reactive Second-Generation (AR2G) Biosensors | Fortebio | Cat# 18-5092 |

| Octet RED96e | Fortebio | https://www.fortebio.com/products/label-free-bli-detection/8-channel-octet-systems |

| QuixStand | GE Healthcare | Cat# 56-4107-78 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Resources, reagents and further information requirement should be forwarded to and will be responded by the Lead Contact, David I Stuart (dave@strubi.ox.ac.uk).

Materials availability

Reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Experimental model and subject details

Viral stocks

SARS-CoV-2/human/AUS/VIC01/2020 (Caly et al., 2020) and SARS-CoV-2/Beta, provided by Public Health England, were both grown in Vero (ATCC CCL-81) cells. Cells were infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus using an MOI of 0.0001. Virus containing supernatant was harvested at 80% CPE and spun at 2000 rpm at 4 °C before storage at -80 °C. Viral titres were determined by a focus-forming assay on Vero cells. Both Victoria passage 5 and Beta passage 4 stocks were sequenced to verify that they contained the expected S sequence and no changes to the furin cleavage sites. The Beta virus used in these studies contained the following mutations: D80A, D215G, L242-244 deleted, K417N, E484K, N501Y, D614G, A701V.

Bacterial strains and cell culture

Vero (ATCC CCL-81) cells were cultured at 37 °C in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (DMEM) high glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Gibco, 35050061) and 100 U/ml of penicillin–streptomycin. Human mAbs were expressed in HEK293T cells cultured in UltraDOMA PF Protein-free Medium (Cat# 12-727F, LONZA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. E.coli DH5α bacteria were used for transformation of plasmid pNEO-RBD K417N, E484K, N501Y. A single colony was picked and cultured in LB broth with 50 μg mL-1 Kanamycin at 37 °C at 200 rpm in a shaker overnight. HEK293T (ATCC CRL-11268) cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% 100X Mem Neaa (Gibco) and 1% 100X L-Glutamine (Gibco) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. To express RBD, RBD K417N, E484K, N501Y and ACE2, HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose (Sigma) supplemented with 2% FBS, 1% 100X Mem Neaa and 1% 100X L-Glutamine at 37 °C for transfection.

Sera from Beta Infected Cases

Beta samples from UK infected cases were collected under the “Innate and adaptive immunity against SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare worker family and household members” protocol affiliated to the Gastro-intestinal illness in Oxford: COVID sub study discussed above and approved by the University of Oxford Central University Research Ethics Committee. All individuals had sequence confirmed Beta infection or PCR-confirmed symptomatic disease occurring whilst in isolation and in direct contact with Beta sequence-confirmed cases. Additional Beta infected serum (sequence confirmed) was obtained from South Africa. The potent antibodies analysed here derived from 4 male patients with ages in the range 40-64. At the time of swab collection patients signed an informed consent to consent for the collection of data and serial blood samples. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand (reference number 200313) and conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Mouse experiments

Animal studies were carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Washington University School of Medicine (assurance number A3381–01). Virus inoculations were performed under anaesthesia that was induced and maintained with ketamine hydrochloride and xylazine, and all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

Heterozygous K18-hACE C57BL/6J mice (strain: 2B6.Cg-Tg(K18-ACE2)2Prlmn/J). Animals were housed in groups and fed standard chow diets. Mice of different ages and both sexes were administered 103 FFU of SARS-CoV-2 via intranasal administration.

For the mouse experiments Vero-hACE2-TMPRSS2 (a gift of A. Creanga and B. Graham, NIH) and Vero-TMPRSS2 cells were cultured at 37°C in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 mM HEPES pH 7.3, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1× non-essential amino acids, and 100 U/ml of penicillin–streptomycin. Additionally, Vero-TMPRSS2 and Vero-hACE2-TMPRSS2 cells were cultured in the presence of 5 μg/mL of blasticidin or puromycin, respectively. The Beta SARS-CoV-2 strain was obtained from a nasopharyngeal isolate (a gift of M. Suthar, Emory). Infectious stocks were propagated by inoculating Vero-TMPRSS2 cells. Supernatant was collected, aliquoted, and stored at -80oC. All work with infectious SARS-CoV-2 was performed in Institutional Biosafety Committee-approved BSL3 and A-BSL3 facilities at Washington University School of Medicine using positive pressure air respirators and protective equipment. Viral sequence was confirmed by deep-sequencing after RNA extraction to confirm the presence of the anticipated substitutions.

Method details

Beta S Protein

To construct the expression plasmids for the S protein of Beta, a construction of trimeric S of the Wuhan strain was used as the template (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a) and nine pairs of primers of S (L18F forward primer 5’-GAGCAGCCAGTGCGTGAATTTCACCACCAGAACCCAGCTG-3’, L18F reverse primer 5’-CAGCTGGGTTCTGGTGGTGAAATTCACGCACTGGCTGCTC -3’; D80A forward primer 5’-GCACCAAGAGATTCGCCAATCCTGTGCTGCC-3’ and D80A reverse primer 5’-GGCAGCACAGGATTGGCGAATCTCTTGGTGC-3’; D215G forward primer 5’-ATTAATCTGGTGAGAGGCCTGCCTCAGGGCTTC-3’, D215G reverse primer 5’-GAAGCCCTGAGGCAGGCCTCTCACCAGATTAAT-3’; 242-244 deletion and R246I forward primer 5’-CCAGATTCCAGACCCTGCACATATCATATCTTACACCAG-3’, 242-244 deletion and R246I reverse primer 5’-CTGGTGTAAGATATGATATGTGCAGGGTCTGGAATCTGG-3′; K417N forward primer 5’-CAGGGCAGACCGGCAATATCGCCGACTACAATTAC-3’, K417N reverse primer 5’-GTAATTGTAGTCGGCGATATTGCCGGTCTGCCCTG -3’; E484K forward primer 5’-CACCGTGTAATGGCGTGAAGGGCTTCAATTGCTAC-3’, E484K reverse primer 5’-GTAGCAATTGAAGCCCTTCACGCCATTACACGGTG-3’; N501Y forward primer 5’-GCTTCCAGCCTACCTATGGCGTGGGCTAC-3’, N501Y reverse primer 5’-GTAGCCCACGCCATAGGTAGGCTGGAAGC-3’; D614G forward primer 5’-GCCGTGCTGTACCAGGGCGTGAATTGCACCGAG-3’, D614G reverse primer 5’-CTCGGTGCAATTCACGCCCTGGTACAGCACGGC-3’; A701V forward primer 5’-CACCATGAGCCTGGGCGTCGAGAATAGCGTGGCC-3’, A701V reverse primer 5’-GGCCACGCTATTCTCGACGCCCAGGCTCATGGTG-3’) and two primers of pHLsec vector (pHLsec forward primer 5’-CCTCAATTTGAGAAATAATGACTCGAGACTAGTATCGCG-3’, pHLsec reverse primer 5’-CGCGATACTAGTCTCGAGTCATTATTTCTCAAATTGAGG-3’) were used to do PCR. Amplified PCR fragments were joint together by Gibson reaction (Gibson, 2011). The new construct was fully sequenced.

Cloning of ACE2 and RBD K417N, E484K, N501Y

ACE2 and RBD K417N, E484K, N501Y were constructed as previously described (Zhou et al., 2021). Briefly, ACE2 was constructed by amplifying amino acids 19-615 of the human ACE2 from an image clone (Sourcebiosciences, clone ID: 5297380) using the forward primer 5’- GCGTAGCTGAAACCGGCTCCACCATTGAGGAACAGGCC-3’ and the reverse primer 5’-GTGATGGTGATGTTTGTCTGCATATGGACTCCAGTC-3’ and inserted into the vector pOPINTTGneo incorporating a C-terminal 6×His tag.

To construct RBD K417N, E484K, N501Y, the RBD N501Y construct was used as the template and K417N primers (Forward 5’-CAGGGCAGACCGGCAATATCGCCGACTACAATTAC-3’, Reverse 5’-GTAATTGTAGTCGGCGATATTGCCGGTCTGCCCTG-3’), E484K primers (Forward 5’- CACCGTGTAATGGCGTGAAGGGCTTCAATTGCTAC-3’, Reverse 5’- GTAGCAATTGAAGCCCTTCACGCCATTACACGGTG-3’) and primers of pNEO vector (Forward 5’- CAGCTCCTGGGCAACGTGCT-3’ and Reverse 5’-CGTAAAAGGAGCAACATAG-3’) were used to amplify DNA fragments. Three PCR fragments were used as templates and amplified again using pNEO vector primers. The final PCR fragment was digested by restriction enzymes AgeI and KpnI and ligated into digested pNEO vector. This construct was confirmed by sequencing.

Cloning of NTD of VoCs

To construct NTD of all VoCs, the gene encoding amino acids 13-305 of the NTD of SARS-CoV-2 S was amplified from soluble S plasmid of each variant by using the forward primer 5′- GGTTGCGTAGCTGAAACCGGTACCATGTTCGTGTTCCTGGTGCTGC -3′ and the reverse primer 5′-TTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGTTTTTCATGCCATTCAATCTTTTGTGCCTCAAAAATATCATTCAAGCTCTTCAGGGTGCACTTGGTCTC -3′ that has a C-terminal BirA-6xHis tag sequence. First PCR products were used as the template to amplify NTD gene, BirA-6xHis tag and overlapping sequence for Gibson assembly by using forward primer 5’- GATGGGTTGCGTAGCTGAAACCGGTAGTCAGTGTGTTAATCTTACAACCAGAACTCAATTAC-3’ for Wuhan and alpha, forward primer 5’- GATGGGTTGCGTAGCTGAAACCGGTAGCCAGTGCGTGAATTTCACC-3’ for gamma, forward primer 5’- GATGGGTTGCGTAGCTGAAACCGGTAGTCAGTGTGTTAATCTTAGGACCAGAACCCAG-3’ fo delta and reverse primer 5’- GATGGGTTGCGTAGCTGAAACCGGTAGCCAGTGCGTGAATTTCACC-3’ for all variants. The second PCR products were cloned into the pHLsec expression vector using the AgeI and XhoI restriction sites. All vectors were sequenced to confirm clones were correct by Sanger sequencing.

Protein Production

Protein expression and purification were conducted as described previously (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a; Zhou et al., 2020). Briefly, plasmids encoding proteins were transiently expressed in HEK293T (ATCC CRL-11268) cells. The conditioned medium was dialysed and purified with a 5 mL HisTrap nickel column (GE Healthcare) and further polished using a Superdex 75 HiLoad 16/60 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare).

Isolation of Beta S-Specific Single B Cells by FACS

Beta S-specific single B cell sorting was performed as previously described (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a). Briefly, PBMC were stained with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua dye (Invitrogen) followed by recombinant trimeric S-twin-Strep of Beta. Cells were then incubated with CD3-FITC, CD14-FITC, CD16-FITC, CD56-FITC, IgM-FITC, IgA-FITC, IgD-FITC, IgG-BV786 and CD19-BUV395, along with Strep-MAB-DY549 to stain the twin strep tag of the S protein. IgG+ memory B cells were gated as CD19+, IgG+, CD3-, CD14-, CD56-, CD16-, IgM-, IgA- and IgD-, and S+ was further selected and single cells were sorted into 96-well PCR plates with 10 μl of catching buffer (Tris, Nuclease free-H2O and RNase inhibitor). Plates were briefly centrifuged at 2000ⅹg for 1 min and left on dry ice before being stored at -80 °C.

Cloning and Expression of Beta S-Specific Human mAbs

Beta S-specific human mAbs were cloned and expressed as described previously (Dejnirattisai et al., 2021a). Briefly, genes for Ig VH, Ig Vκ and Ig Vλ were recovered from positive wells by RT-PCR. Genes encoding Ig VH, Ig Vκ and Ig Vλ were then amplified using Nested-PCR by a cocktail of primers specific to human IgG. PCR products of HC and LCs were ligated into the expression vectors of human IgG1 or immunoglobulin κ-chain or λ-chain by Gibson assembly (Gibson, 2011). For mAb expression, plasmids encoding HCs and LCs were co-transfected by PEI-transfection into a HEK293T cell line, and supernatants containing mAbs were collected and filtered 4-5 days after transfection, and the supernatants were further characterized or purified.

Construction of Fab Expression Plasmids

Heavy chain expressing the specific mAbs were used as templates to amplify the heavy chain vector including the variable region and CH1 by Fab primers (Forward 5’- CAAGAGAGTTGAGCCCAAATCTTGTCTGGTGCCACGCGGAAGTAGTGCCTGGTCCCAC-3’, Reverse 5’- GTGGGACCAGGCACTACTTCCGCGTGGCACCAGACAAGATTTGGGCTCAACTCTCTTG-3’). The fragment with thrombin cleavage site and twin-strep tag overlapping with the Fab fragment were also amplified (Forward 5’-CATCCACAGTTCGAGAAATAGGTGCGACGGCCGGCAAG-3’, Reverse 5’- CTTGCCGGCCGTCGCACCTATTTCTCGAACTGTGGATG-3’). Fab fragment and tag fragment were joined by Gibson assembly (Gibson, 2011) and full plasmids were sequenced.

IgG mAbs and Fab Purification

To purify full length IgG mAbs, supernatants of mAb expression were collected and filtered by a vacuum filter system and loaded on protein A/G beads over night at 4 °C. Beads were washed with PBS three times and 0.1 M glycine pH2.7 was used to elute IgG. The eluate was neutralized with Tris-HCl pH8 buffer to make the final pH=7. The IgG concentration was determined by spectro-photometry and buffered exchanged into PBS.

To express and purify Fab, Fab heavy chain and light chain expression plasmids were co-transfected into HEK293T cells by PEI in Free-style 293 medium. After culturing for 5 days at 37°C with 5% CO2, culture supernatant was harvested and filtered using a 0.22 mm polyethersulfone filter. Fab were purified using the Strep-Tactin XT purification system.

Preparation of Fabs from IgGs

Fab fragments were digested from purified IgGs with papain using a Pierce Fab Preparation Kit (Thermo Fisher), following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Determination of mAb Binding to Recombinant S, RBD or NTD by ELISA

For spike, MAXISORP immunoplates (442404; NUNC) were coated with 2.5 μg/ml of StrepMAB-Classic (2-1597-001; iba) diluted by carbonate-bicarbonate buffer at 4°C overnight. Plates were blocked with 2% BSA dissolved by PBS for 1hr, and then 50 μl of 5 μg/ml of dual Strep-tagged S was added to each well and incubated for 1 hr at room temperate. 50 μl of mAb-expression supernatant or a series of dilutions of mAb was added, followed by ALP-conjugated anti-human IgG (A9544; Sigma) at 1:10,000 dilution. Plates were developed by adding PNPP substrate. After 40 min, the absorbance was measured at 405 nm.

To determine the binding to recombinant RBD or NTD, MAXISORP immunoplates were coated with 5 μg/ml of purified recombinant RBD-K417N, E484K, N501Y or NTD at 4 °C overnight. Plates were blocked with 2 % BSA dissolved by PBS for 1 h. After the addition of 50μl of mAb-expression supernatants or a series of dilutions of mAb, the rest of the procedure is the same as the S binding assay.

Focus Reduction Neutralization (FRNT)

The Focus reduction neutralization test was performed as previously described (Liu et al., 2021). Briefly, serially diluted Ab was mixed with SARS-CoV-2 strains Victoria, Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Alpha+E484K, Delta, or B.1.525 and incubated for 1 hr at 37 °C. The mixtures were transferred to 96-well, cell culture microplates containing confluent Vero cell monolayers in duplicate and incubated for 2 hr, followed by the addition of 1.5 % semi-solid carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) overlay medium. A focus forming assay was then performed by staining Vero cells with human anti-NP mAb (mAb206) as primary antibody and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (A0170; Sigma) as secondary antibody. Finally, TrueBlue Peroxidase Substrate was added to each well to visualise the foci (infected cells). Virus-infected cell foci were counted on the classic AID EliSpot reader using AID ELISpot software.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses are reported in the results and figure legends. Neutralization was measured by FRNT. The percentage of focus reduction was calculated and IC50 (FRNT50) was determined using the probit program from the SPSS package. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was used for the analysis and two-tailed P values were calculated on geometric mean values. BLI data were analysed using Data Analysis HT 11.1 (Fortebio) with a 1:1 fitting model.

ACE2 Binding Inhibition Assay by ELISA

MAXISORP immunoplates were coated with 5 μg/ml of purified ACE2-His protein overnight at 4 °C and then blocked by 2% BSA in PBS. Meanwhile, mAbs were serially diluted and mixed with 2.5 μg/ml of recombinant Beta trimeric S-twin-Strep. Antibody-S protein mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. After incubation, the mixtures were transferred into the ACE2-coated plates and incubated for 1 hr at 37 °C. After wash, StrepMAB-Classic (2-1507-001, iba) was diluted at 0.2 μg/ml by 2% BSA and used as primary antibody followed by Goat anti-mouse IgG-AP (#A16093, Invitrogen) at 1:2000 dilution. The reaction was developed by adding PNPP substrate and stopped with NaOH. The absorbance was measured at 405nm. The ACE2/S binding inhibition was calculated by comparing to the antibody-free control well. IC50 was determined using the Probit program from the SPSS package.

Measurement of Viral Burden

Tissues were weighed and homogenized with zirconia beads in a MagNA Lyser instrument (Roche Life Science) in 1,000 μL of DMEM media supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated FBS. Tissue homogenates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 5 min and stored at −80°C. RNA was extracted using the MagMax mirVana Total RNA isolation kit (Thermo Scientific) on a Kingfisher Flex extraction robot (Thermo Scientific). RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified using the TaqMan RNA-to-CT 1-Step Kit (ThermoFisher). Reverse transcription was carried out at 48°C for 15 min followed by 2 min at 95°C. Amplification was accomplished over 50 cycles as follows: 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Copies of SARS-CoV-2 N gene RNA in samples were determined using a previously published assay (Case et al., 2020; Hassan et al., 2020). Briefly, a TaqMan assay was designed to target a highly conserved region of the N gene (Forward primer: ATGCTGCAATCGTGCTACAA; Reverse primer: GACTGCCGCCTCTGCTC; Probe: /56-FAM/TCAAGGAAC/ZEN/AACATTGCCAA/3IABkFQ/). This region was included in an RNA standard to allow for copy number determination down to 10 copies per reaction. The reaction mixture contained final concentrations of primers and probe of 500 and 100 nM, respectively.

Statistical significance was assigned when P values were <0.05 using Prism Version 8 (GraphPad). Tests, number of animals, median values, and statistical comparison groups are indicated in each of the Figure legends. Analysis of weight change was determined by ANOVA https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/anova/default2.aspx. Changes in viral burden were compared to control antibody-treated animals and analysed by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons tests.

Antibody Correlation Analysis